User login

Buspirone: A forgotten friend

In general, when a medication goes off patent, marketing for it significantly slows down or comes to a halt. Studies have shown that physicians’ prescribing habits are influenced by pharmaceutical representatives and companies.1 This phenomenon may have an unforeseen adverse effect: once an effective and inexpensive medication “goes generic,” its use may fall out of favor. Additionally, physicians may have concerns about prescribing generic medications, such as perceiving them as less effective and conferring more adverse effects compared with brand-name formulations.2 One such generic medication is buspirone, which originally was branded as BuSpar.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnoses, and at times are the most challenging to treat.3 Anecdotally, we often see benzodiazepines prescribed as first-line monotherapy for acute and chronic anxiety, but because these agents can cause physical dependence and a withdrawal reaction, alternative anxiolytic medications should be strongly considered. Despite its age, buspirone still plays a role in the treatment of anxiety, and its off-label use can also be useful in certain populations and scenarios. In this article, we delve into buspirone’s mechanism of action, discuss its advantages and challenges, and what you need to know when prescribing it.

How buspirone works

Buspirone was originally described as an anxiolytic agent that was pharmacologically unrelated to traditional anxiety-reducing medications (ie, benzodiazepines and barbiturates).4

The antidepressants vortioxetine and vilazodone exhibit dual-action at both serotonin reuptake transporters and 5HT1A receptors; thus, they work like an SSRI and buspirone combined.6 Although some patients may find it more convenient to take a dual-action pill over 2 separate ones, some insurance companies do not cover these newer agents. Additionally, prescribing buspirone separately allows for more precise dosing, which may lower the risk of adverse effects.

Buspirone is a major substrate for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and a minor for CYP2D6, so caution must be advised if considering buspirone for a patient receiving any CYP3A4 inducers and/or inhibitors,7 including grapefruit juice.8

Dose adjustments are not necessary for age and sex, which allows for highly consistent dosing.4 However, as with prescribing medications in any geriatric population, lower starting doses and slower titration of buspirone may be necessary to avoid potential adverse effects due to the alterations of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic processes that occur as patients age.9

Advantages of buspirone

Works well as an add-on to other medications. While buspirone in adequate doses may be helpful as monotherapy in GAD, it can also be helpful in other, more complex psychiatric scenarios. Sumiyoshi et al10 observed improvement in scores on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test when buspirone was added to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), which suggests buspirone may help improve attention in patients with schizophrenia. It has been postulated that buspirone may also be helpful for cognitive dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.11 Buspirone has been used to treat comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorder, resulting in reduced anxiety, longer latency to relapse, and fewer drinking days during a 12-week treatment program.12 Buspirone has been more effective than placebo for treating post-stroke anxiety.13

Continue to: Patients who receive...

Patients who receive an SSRI, such as citalopram, but are not able to achieve a substantial improvement in their depressive and/or anxious symptoms may benefit from the addition of buspirone to their treatment regimen.14,15

A favorable adverse-effect profile. There are no absolute contraindications to buspirone except a history of hypersensitivity.4 Buspirone generally is well tolerated and carries a low risk of adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are dizziness and nausea.6 Buspirone is not sedating.

Potentially safe for patients who are pregnant. Unlike many other first-line agents for anxiety, such as SSRIs, buspirone has an FDA Category B classification, meaning animal studies have shown no adverse events during pregnancy.4 The FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule applies only to medications that entered the market on or after June 30, 2001; unfortunately, buspirone is excluded from this updated categorization.16 As with any medication being considered for pregnant or lactating women, the prescriber and patient must weigh the benefits vs the risks to determine if buspirone is appropriate for any individual patient.

No adverse events have been reported from abrupt discontinuation of buspirone.17

Inexpensive. Buspirone is generic and extremely inexpensive. According to GoodRx.com, a 30-day supply of 5-mg tablets for twice-daily dosing can cost $4.18 A maximum daily dose (prescribed as 2 pills, 15 mg twice daily) may cost approximately $18/month.18 Thus, buspirone is a good option for uninsured or underinsured patients, for whom this would be more affordable than other anxiolytic medications.

Continue to: May offset certain adverse effects

May offset certain adverse effects. Sexual dysfunction is a common adverse effect of SSRIs. One strategy to offset this phenomenon is to add bupropion. However, in a randomized controlled trial, Landén et al19 found that sexual adverse effects induced by SSRIs were greatly mitigated by adding buspirone, even within the first week of treatment. This improvement was more marked in women than in men, which is helpful because sexual dysfunction in women is generally resistant to other interventions.20 Unlike

Unlikely to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Because of its central D2 antagonism, buspirone has a low potential (<1%) to produce EPS. Buspirone has even been shown to reverse

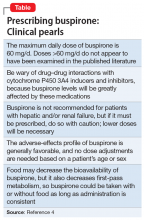

The Table4 highlights key points to bear in mind when prescribing buspirone.

Challenges with buspirone

Response is not immediate. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone does not have an immediate onset of action.22 With buspirone monotherapy, response may be seen in approximately 2 to 4 weeks.23 Therefore, patients transitioning from a quick-onset benzodiazepine to buspirone may not report a good response. However, as noted above, when using buspirone to treat SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, response may emerge within 1 week.19 Buspirone also lacks the euphoric and sedative qualities of benzodiazepines that patients may prefer.

Not for patients with hepatic and renal impairment. Because plasma levels of buspirone are elevated in patients with hepatic and renal impairment, this medication is not ideal for use in these populations.4

Continue to: Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs

Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs. Buspirone should not be prescribed to patients with depression who are receiving treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) because the combination may precipitate a hypertensive reaction.4 A minimum washout period of 14 days from the MAOI is necessary before initiating buspirone.9

Idiosyncratic adverse effects. As with all pharmaceuticals, buspirone may produce idiosyncratic adverse effects. Faber and Sansone24 reported a case of a woman who experienced hair loss 3 months into treatment with buspirone. After cessation, her alopecia resolved.

Questionable efficacy for some anxiety subtypes. Buspirone has been studied as a treatment of other common psychiatric conditions, such as social phobia and anxiety in the setting of smoking cessation. However, it has not proven to be effective over placebo in treating these anxiety subtypes.25,26

Short half-life. Because of its relatively short half-life (2 to 3 hours), buspirone requires dosing 2 to 3 times a day, which could increase the risk of noncompliance.4 However, some patients might prefer multiple dosing throughout the day due to perceived better coverage of their anxiety symptoms.

Limited incentive for future research. Because buspirone is available only as a generic formulation, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies and other interested parties to study what may be valuable uses for buspirone. For example, there is no data available on comparative augmentation of buspirone and SGAs with antidepressants for depression and/or anxiety. There is also little data available about buspirone prescribing trends or why buspirone may be underutilized in clinical practice today.

Continue to: Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal...

Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal data on the prescribing practices of buspirone is limited because the original branded medication, BuSpar, is no longer on the market. However, this medication offers multiple advantages over other agents used to treat anxiety, and it should not be forgotten when formulating a treatment regimen for patients with anxiety and/or depression.

Bottom Line

Buspirone is a safe, low-cost, effective treatment option for patients with anxiety and may be helpful as an augmenting agent for depression. Because of its efficacy and high degree of tolerability, it should be prioritized higher in our treatment algorithms and be a part of our routine pharmacologic armamentarium.

Related Resources

- Howland RH. Buspirone: Back to the future. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015;53(11):21-24.

- Strawn JR, Mills JA, Cornwall GJ, et al. Buspirone in children and adolescents with anxiety: a review and Bayesian analysis of abandoned randomized controlled trials. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):2-9.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Buspirone • BuSpar

Citalopram • Celexa

Haloperidol • Haldol

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

1. Fickweiler F, Fickweiler W, Urbach E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians’ attitudes and prescribing habits: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016408. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016408.

2. Haque M. Generic medicine and prescribing: a quick assessment. Adv Hum Biol. 2017;7(3):101-108.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Anxiety disorders. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Anxiety-Disorders. Published December 2017. Accessed November 26, 2019.

4. Buspar [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2000.

5. Hjorth S, Carlsson A. Buspirone: effects on central monoaminergic transmission-possible relevance to animal experimental and clinical findings. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982:83;299-303.

6. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications, 4th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

7. Buspirone tablets [package insert]. East Brunswick, NJ: Strides Pharma Inc; 2017.

8. Lilja JJ, Kivistö KT, Backman, JT, et al. Grapefruit juice substantially increases plasma concentrations of buspirone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:655-660.

9. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: prescriber’s guide, 6th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

10. Sumiyoshi T, Park S, Jayathilake K. Effect of buspirone, a serotonin1A partial agonist, on cognitive function in schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2007;95(1-3):158-168.

11. Schechter LE, Dawson LA, Harder JA. The potential utility of 5-HT1A receptor antagonists in the treatment of cognitive dysfunction associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(2):139-145.

12. Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Del Boca FK. Buspirone treatment of anxious alcoholics: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(9):720-731.

13. Burton CA, Holmes J, Murray J, et al. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:1-25.

14. Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, et al. Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001; 62(6):448-452.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd edition. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed November 2019.

16. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/labeling/pregnancy-and-lactation-labeling-drugs-final-rule. Published September 11, 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

17. Goa KL, Ward A. Buspirone. A preliminary review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy as an anxiolytic. Drugs. 1986;32(2):114-129.

18. GoodRx. Buspar prices, coupons, & savings tips in U.S. area code 08054. https://www.goodrx.com/buspar. Accessed June 6, 2019.

19. Landén M, Eriksson E, Agren H, et al. Effect of buspirone on sexual dysfunction in depressed patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(3):268-271.

20. Hensley PL, Nurnberg HG. SSRI sexual dysfunction: a female perspective. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(suppl 1):143-153.

21. Haleem DJ, Samad N, Haleem MA. Reversal of haloperidol-induced extrapyramidal symptoms by buspirone: a time-related study. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18(2):147-153.

22. Kaplan SS, Saddock BJ, Grebb JA. Synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

23. National Alliance on Mental Health. Buspirone (BuSpar). https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Treatment/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Buspirone-(BuSpar). Published January 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

24. Faber J, Sansone RA. Buspirone: a possible cause of alopecia. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(1):13.

25. Van Vliet IM, Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, et al. Clinical effects of buspirone in social phobia, a double-blind placebo controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):164-168.

26. Schneider NG, Olmstead RE, Steinberg C, et al. Efficacy of buspirone in smoking cessation: a placebo‐controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60(5):568-575.

In general, when a medication goes off patent, marketing for it significantly slows down or comes to a halt. Studies have shown that physicians’ prescribing habits are influenced by pharmaceutical representatives and companies.1 This phenomenon may have an unforeseen adverse effect: once an effective and inexpensive medication “goes generic,” its use may fall out of favor. Additionally, physicians may have concerns about prescribing generic medications, such as perceiving them as less effective and conferring more adverse effects compared with brand-name formulations.2 One such generic medication is buspirone, which originally was branded as BuSpar.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnoses, and at times are the most challenging to treat.3 Anecdotally, we often see benzodiazepines prescribed as first-line monotherapy for acute and chronic anxiety, but because these agents can cause physical dependence and a withdrawal reaction, alternative anxiolytic medications should be strongly considered. Despite its age, buspirone still plays a role in the treatment of anxiety, and its off-label use can also be useful in certain populations and scenarios. In this article, we delve into buspirone’s mechanism of action, discuss its advantages and challenges, and what you need to know when prescribing it.

How buspirone works

Buspirone was originally described as an anxiolytic agent that was pharmacologically unrelated to traditional anxiety-reducing medications (ie, benzodiazepines and barbiturates).4

The antidepressants vortioxetine and vilazodone exhibit dual-action at both serotonin reuptake transporters and 5HT1A receptors; thus, they work like an SSRI and buspirone combined.6 Although some patients may find it more convenient to take a dual-action pill over 2 separate ones, some insurance companies do not cover these newer agents. Additionally, prescribing buspirone separately allows for more precise dosing, which may lower the risk of adverse effects.

Buspirone is a major substrate for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and a minor for CYP2D6, so caution must be advised if considering buspirone for a patient receiving any CYP3A4 inducers and/or inhibitors,7 including grapefruit juice.8

Dose adjustments are not necessary for age and sex, which allows for highly consistent dosing.4 However, as with prescribing medications in any geriatric population, lower starting doses and slower titration of buspirone may be necessary to avoid potential adverse effects due to the alterations of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic processes that occur as patients age.9

Advantages of buspirone

Works well as an add-on to other medications. While buspirone in adequate doses may be helpful as monotherapy in GAD, it can also be helpful in other, more complex psychiatric scenarios. Sumiyoshi et al10 observed improvement in scores on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test when buspirone was added to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), which suggests buspirone may help improve attention in patients with schizophrenia. It has been postulated that buspirone may also be helpful for cognitive dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.11 Buspirone has been used to treat comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorder, resulting in reduced anxiety, longer latency to relapse, and fewer drinking days during a 12-week treatment program.12 Buspirone has been more effective than placebo for treating post-stroke anxiety.13

Continue to: Patients who receive...

Patients who receive an SSRI, such as citalopram, but are not able to achieve a substantial improvement in their depressive and/or anxious symptoms may benefit from the addition of buspirone to their treatment regimen.14,15

A favorable adverse-effect profile. There are no absolute contraindications to buspirone except a history of hypersensitivity.4 Buspirone generally is well tolerated and carries a low risk of adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are dizziness and nausea.6 Buspirone is not sedating.

Potentially safe for patients who are pregnant. Unlike many other first-line agents for anxiety, such as SSRIs, buspirone has an FDA Category B classification, meaning animal studies have shown no adverse events during pregnancy.4 The FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule applies only to medications that entered the market on or after June 30, 2001; unfortunately, buspirone is excluded from this updated categorization.16 As with any medication being considered for pregnant or lactating women, the prescriber and patient must weigh the benefits vs the risks to determine if buspirone is appropriate for any individual patient.

No adverse events have been reported from abrupt discontinuation of buspirone.17

Inexpensive. Buspirone is generic and extremely inexpensive. According to GoodRx.com, a 30-day supply of 5-mg tablets for twice-daily dosing can cost $4.18 A maximum daily dose (prescribed as 2 pills, 15 mg twice daily) may cost approximately $18/month.18 Thus, buspirone is a good option for uninsured or underinsured patients, for whom this would be more affordable than other anxiolytic medications.

Continue to: May offset certain adverse effects

May offset certain adverse effects. Sexual dysfunction is a common adverse effect of SSRIs. One strategy to offset this phenomenon is to add bupropion. However, in a randomized controlled trial, Landén et al19 found that sexual adverse effects induced by SSRIs were greatly mitigated by adding buspirone, even within the first week of treatment. This improvement was more marked in women than in men, which is helpful because sexual dysfunction in women is generally resistant to other interventions.20 Unlike

Unlikely to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Because of its central D2 antagonism, buspirone has a low potential (<1%) to produce EPS. Buspirone has even been shown to reverse

The Table4 highlights key points to bear in mind when prescribing buspirone.

Challenges with buspirone

Response is not immediate. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone does not have an immediate onset of action.22 With buspirone monotherapy, response may be seen in approximately 2 to 4 weeks.23 Therefore, patients transitioning from a quick-onset benzodiazepine to buspirone may not report a good response. However, as noted above, when using buspirone to treat SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, response may emerge within 1 week.19 Buspirone also lacks the euphoric and sedative qualities of benzodiazepines that patients may prefer.

Not for patients with hepatic and renal impairment. Because plasma levels of buspirone are elevated in patients with hepatic and renal impairment, this medication is not ideal for use in these populations.4

Continue to: Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs

Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs. Buspirone should not be prescribed to patients with depression who are receiving treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) because the combination may precipitate a hypertensive reaction.4 A minimum washout period of 14 days from the MAOI is necessary before initiating buspirone.9

Idiosyncratic adverse effects. As with all pharmaceuticals, buspirone may produce idiosyncratic adverse effects. Faber and Sansone24 reported a case of a woman who experienced hair loss 3 months into treatment with buspirone. After cessation, her alopecia resolved.

Questionable efficacy for some anxiety subtypes. Buspirone has been studied as a treatment of other common psychiatric conditions, such as social phobia and anxiety in the setting of smoking cessation. However, it has not proven to be effective over placebo in treating these anxiety subtypes.25,26

Short half-life. Because of its relatively short half-life (2 to 3 hours), buspirone requires dosing 2 to 3 times a day, which could increase the risk of noncompliance.4 However, some patients might prefer multiple dosing throughout the day due to perceived better coverage of their anxiety symptoms.

Limited incentive for future research. Because buspirone is available only as a generic formulation, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies and other interested parties to study what may be valuable uses for buspirone. For example, there is no data available on comparative augmentation of buspirone and SGAs with antidepressants for depression and/or anxiety. There is also little data available about buspirone prescribing trends or why buspirone may be underutilized in clinical practice today.

Continue to: Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal...

Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal data on the prescribing practices of buspirone is limited because the original branded medication, BuSpar, is no longer on the market. However, this medication offers multiple advantages over other agents used to treat anxiety, and it should not be forgotten when formulating a treatment regimen for patients with anxiety and/or depression.

Bottom Line

Buspirone is a safe, low-cost, effective treatment option for patients with anxiety and may be helpful as an augmenting agent for depression. Because of its efficacy and high degree of tolerability, it should be prioritized higher in our treatment algorithms and be a part of our routine pharmacologic armamentarium.

Related Resources

- Howland RH. Buspirone: Back to the future. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015;53(11):21-24.

- Strawn JR, Mills JA, Cornwall GJ, et al. Buspirone in children and adolescents with anxiety: a review and Bayesian analysis of abandoned randomized controlled trials. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):2-9.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Buspirone • BuSpar

Citalopram • Celexa

Haloperidol • Haldol

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

In general, when a medication goes off patent, marketing for it significantly slows down or comes to a halt. Studies have shown that physicians’ prescribing habits are influenced by pharmaceutical representatives and companies.1 This phenomenon may have an unforeseen adverse effect: once an effective and inexpensive medication “goes generic,” its use may fall out of favor. Additionally, physicians may have concerns about prescribing generic medications, such as perceiving them as less effective and conferring more adverse effects compared with brand-name formulations.2 One such generic medication is buspirone, which originally was branded as BuSpar.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnoses, and at times are the most challenging to treat.3 Anecdotally, we often see benzodiazepines prescribed as first-line monotherapy for acute and chronic anxiety, but because these agents can cause physical dependence and a withdrawal reaction, alternative anxiolytic medications should be strongly considered. Despite its age, buspirone still plays a role in the treatment of anxiety, and its off-label use can also be useful in certain populations and scenarios. In this article, we delve into buspirone’s mechanism of action, discuss its advantages and challenges, and what you need to know when prescribing it.

How buspirone works

Buspirone was originally described as an anxiolytic agent that was pharmacologically unrelated to traditional anxiety-reducing medications (ie, benzodiazepines and barbiturates).4

The antidepressants vortioxetine and vilazodone exhibit dual-action at both serotonin reuptake transporters and 5HT1A receptors; thus, they work like an SSRI and buspirone combined.6 Although some patients may find it more convenient to take a dual-action pill over 2 separate ones, some insurance companies do not cover these newer agents. Additionally, prescribing buspirone separately allows for more precise dosing, which may lower the risk of adverse effects.

Buspirone is a major substrate for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and a minor for CYP2D6, so caution must be advised if considering buspirone for a patient receiving any CYP3A4 inducers and/or inhibitors,7 including grapefruit juice.8

Dose adjustments are not necessary for age and sex, which allows for highly consistent dosing.4 However, as with prescribing medications in any geriatric population, lower starting doses and slower titration of buspirone may be necessary to avoid potential adverse effects due to the alterations of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic processes that occur as patients age.9

Advantages of buspirone

Works well as an add-on to other medications. While buspirone in adequate doses may be helpful as monotherapy in GAD, it can also be helpful in other, more complex psychiatric scenarios. Sumiyoshi et al10 observed improvement in scores on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test when buspirone was added to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), which suggests buspirone may help improve attention in patients with schizophrenia. It has been postulated that buspirone may also be helpful for cognitive dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.11 Buspirone has been used to treat comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorder, resulting in reduced anxiety, longer latency to relapse, and fewer drinking days during a 12-week treatment program.12 Buspirone has been more effective than placebo for treating post-stroke anxiety.13

Continue to: Patients who receive...

Patients who receive an SSRI, such as citalopram, but are not able to achieve a substantial improvement in their depressive and/or anxious symptoms may benefit from the addition of buspirone to their treatment regimen.14,15

A favorable adverse-effect profile. There are no absolute contraindications to buspirone except a history of hypersensitivity.4 Buspirone generally is well tolerated and carries a low risk of adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are dizziness and nausea.6 Buspirone is not sedating.

Potentially safe for patients who are pregnant. Unlike many other first-line agents for anxiety, such as SSRIs, buspirone has an FDA Category B classification, meaning animal studies have shown no adverse events during pregnancy.4 The FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule applies only to medications that entered the market on or after June 30, 2001; unfortunately, buspirone is excluded from this updated categorization.16 As with any medication being considered for pregnant or lactating women, the prescriber and patient must weigh the benefits vs the risks to determine if buspirone is appropriate for any individual patient.

No adverse events have been reported from abrupt discontinuation of buspirone.17

Inexpensive. Buspirone is generic and extremely inexpensive. According to GoodRx.com, a 30-day supply of 5-mg tablets for twice-daily dosing can cost $4.18 A maximum daily dose (prescribed as 2 pills, 15 mg twice daily) may cost approximately $18/month.18 Thus, buspirone is a good option for uninsured or underinsured patients, for whom this would be more affordable than other anxiolytic medications.

Continue to: May offset certain adverse effects

May offset certain adverse effects. Sexual dysfunction is a common adverse effect of SSRIs. One strategy to offset this phenomenon is to add bupropion. However, in a randomized controlled trial, Landén et al19 found that sexual adverse effects induced by SSRIs were greatly mitigated by adding buspirone, even within the first week of treatment. This improvement was more marked in women than in men, which is helpful because sexual dysfunction in women is generally resistant to other interventions.20 Unlike

Unlikely to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Because of its central D2 antagonism, buspirone has a low potential (<1%) to produce EPS. Buspirone has even been shown to reverse

The Table4 highlights key points to bear in mind when prescribing buspirone.

Challenges with buspirone

Response is not immediate. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone does not have an immediate onset of action.22 With buspirone monotherapy, response may be seen in approximately 2 to 4 weeks.23 Therefore, patients transitioning from a quick-onset benzodiazepine to buspirone may not report a good response. However, as noted above, when using buspirone to treat SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, response may emerge within 1 week.19 Buspirone also lacks the euphoric and sedative qualities of benzodiazepines that patients may prefer.

Not for patients with hepatic and renal impairment. Because plasma levels of buspirone are elevated in patients with hepatic and renal impairment, this medication is not ideal for use in these populations.4

Continue to: Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs

Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs. Buspirone should not be prescribed to patients with depression who are receiving treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) because the combination may precipitate a hypertensive reaction.4 A minimum washout period of 14 days from the MAOI is necessary before initiating buspirone.9

Idiosyncratic adverse effects. As with all pharmaceuticals, buspirone may produce idiosyncratic adverse effects. Faber and Sansone24 reported a case of a woman who experienced hair loss 3 months into treatment with buspirone. After cessation, her alopecia resolved.

Questionable efficacy for some anxiety subtypes. Buspirone has been studied as a treatment of other common psychiatric conditions, such as social phobia and anxiety in the setting of smoking cessation. However, it has not proven to be effective over placebo in treating these anxiety subtypes.25,26

Short half-life. Because of its relatively short half-life (2 to 3 hours), buspirone requires dosing 2 to 3 times a day, which could increase the risk of noncompliance.4 However, some patients might prefer multiple dosing throughout the day due to perceived better coverage of their anxiety symptoms.

Limited incentive for future research. Because buspirone is available only as a generic formulation, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies and other interested parties to study what may be valuable uses for buspirone. For example, there is no data available on comparative augmentation of buspirone and SGAs with antidepressants for depression and/or anxiety. There is also little data available about buspirone prescribing trends or why buspirone may be underutilized in clinical practice today.

Continue to: Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal...

Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal data on the prescribing practices of buspirone is limited because the original branded medication, BuSpar, is no longer on the market. However, this medication offers multiple advantages over other agents used to treat anxiety, and it should not be forgotten when formulating a treatment regimen for patients with anxiety and/or depression.

Bottom Line

Buspirone is a safe, low-cost, effective treatment option for patients with anxiety and may be helpful as an augmenting agent for depression. Because of its efficacy and high degree of tolerability, it should be prioritized higher in our treatment algorithms and be a part of our routine pharmacologic armamentarium.

Related Resources

- Howland RH. Buspirone: Back to the future. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015;53(11):21-24.

- Strawn JR, Mills JA, Cornwall GJ, et al. Buspirone in children and adolescents with anxiety: a review and Bayesian analysis of abandoned randomized controlled trials. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):2-9.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Buspirone • BuSpar

Citalopram • Celexa

Haloperidol • Haldol

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

1. Fickweiler F, Fickweiler W, Urbach E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians’ attitudes and prescribing habits: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016408. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016408.

2. Haque M. Generic medicine and prescribing: a quick assessment. Adv Hum Biol. 2017;7(3):101-108.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Anxiety disorders. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Anxiety-Disorders. Published December 2017. Accessed November 26, 2019.

4. Buspar [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2000.

5. Hjorth S, Carlsson A. Buspirone: effects on central monoaminergic transmission-possible relevance to animal experimental and clinical findings. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982:83;299-303.

6. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications, 4th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

7. Buspirone tablets [package insert]. East Brunswick, NJ: Strides Pharma Inc; 2017.

8. Lilja JJ, Kivistö KT, Backman, JT, et al. Grapefruit juice substantially increases plasma concentrations of buspirone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:655-660.

9. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: prescriber’s guide, 6th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

10. Sumiyoshi T, Park S, Jayathilake K. Effect of buspirone, a serotonin1A partial agonist, on cognitive function in schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2007;95(1-3):158-168.

11. Schechter LE, Dawson LA, Harder JA. The potential utility of 5-HT1A receptor antagonists in the treatment of cognitive dysfunction associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(2):139-145.

12. Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Del Boca FK. Buspirone treatment of anxious alcoholics: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(9):720-731.

13. Burton CA, Holmes J, Murray J, et al. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:1-25.

14. Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, et al. Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001; 62(6):448-452.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd edition. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed November 2019.

16. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/labeling/pregnancy-and-lactation-labeling-drugs-final-rule. Published September 11, 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

17. Goa KL, Ward A. Buspirone. A preliminary review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy as an anxiolytic. Drugs. 1986;32(2):114-129.

18. GoodRx. Buspar prices, coupons, & savings tips in U.S. area code 08054. https://www.goodrx.com/buspar. Accessed June 6, 2019.

19. Landén M, Eriksson E, Agren H, et al. Effect of buspirone on sexual dysfunction in depressed patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(3):268-271.

20. Hensley PL, Nurnberg HG. SSRI sexual dysfunction: a female perspective. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(suppl 1):143-153.

21. Haleem DJ, Samad N, Haleem MA. Reversal of haloperidol-induced extrapyramidal symptoms by buspirone: a time-related study. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18(2):147-153.

22. Kaplan SS, Saddock BJ, Grebb JA. Synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

23. National Alliance on Mental Health. Buspirone (BuSpar). https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Treatment/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Buspirone-(BuSpar). Published January 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

24. Faber J, Sansone RA. Buspirone: a possible cause of alopecia. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(1):13.

25. Van Vliet IM, Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, et al. Clinical effects of buspirone in social phobia, a double-blind placebo controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):164-168.

26. Schneider NG, Olmstead RE, Steinberg C, et al. Efficacy of buspirone in smoking cessation: a placebo‐controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60(5):568-575.

1. Fickweiler F, Fickweiler W, Urbach E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians’ attitudes and prescribing habits: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016408. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016408.

2. Haque M. Generic medicine and prescribing: a quick assessment. Adv Hum Biol. 2017;7(3):101-108.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Anxiety disorders. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Anxiety-Disorders. Published December 2017. Accessed November 26, 2019.

4. Buspar [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2000.

5. Hjorth S, Carlsson A. Buspirone: effects on central monoaminergic transmission-possible relevance to animal experimental and clinical findings. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982:83;299-303.

6. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications, 4th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

7. Buspirone tablets [package insert]. East Brunswick, NJ: Strides Pharma Inc; 2017.

8. Lilja JJ, Kivistö KT, Backman, JT, et al. Grapefruit juice substantially increases plasma concentrations of buspirone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:655-660.

9. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: prescriber’s guide, 6th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

10. Sumiyoshi T, Park S, Jayathilake K. Effect of buspirone, a serotonin1A partial agonist, on cognitive function in schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2007;95(1-3):158-168.

11. Schechter LE, Dawson LA, Harder JA. The potential utility of 5-HT1A receptor antagonists in the treatment of cognitive dysfunction associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(2):139-145.

12. Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Del Boca FK. Buspirone treatment of anxious alcoholics: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(9):720-731.

13. Burton CA, Holmes J, Murray J, et al. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:1-25.

14. Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, et al. Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001; 62(6):448-452.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd edition. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed November 2019.

16. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/labeling/pregnancy-and-lactation-labeling-drugs-final-rule. Published September 11, 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

17. Goa KL, Ward A. Buspirone. A preliminary review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy as an anxiolytic. Drugs. 1986;32(2):114-129.

18. GoodRx. Buspar prices, coupons, & savings tips in U.S. area code 08054. https://www.goodrx.com/buspar. Accessed June 6, 2019.

19. Landén M, Eriksson E, Agren H, et al. Effect of buspirone on sexual dysfunction in depressed patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(3):268-271.

20. Hensley PL, Nurnberg HG. SSRI sexual dysfunction: a female perspective. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(suppl 1):143-153.

21. Haleem DJ, Samad N, Haleem MA. Reversal of haloperidol-induced extrapyramidal symptoms by buspirone: a time-related study. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18(2):147-153.

22. Kaplan SS, Saddock BJ, Grebb JA. Synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

23. National Alliance on Mental Health. Buspirone (BuSpar). https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Treatment/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Buspirone-(BuSpar). Published January 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

24. Faber J, Sansone RA. Buspirone: a possible cause of alopecia. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(1):13.

25. Van Vliet IM, Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, et al. Clinical effects of buspirone in social phobia, a double-blind placebo controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):164-168.

26. Schneider NG, Olmstead RE, Steinberg C, et al. Efficacy of buspirone in smoking cessation: a placebo‐controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60(5):568-575.

Tips for telling your patients good-bye

Transferring to another psychiatrist can distress mental health patients and disrupt treatment, whether you part ways with them because of an insurance change or relocation. A smooth transfer helps maintain patients’ clinical progress and reduces the risk of losing them to follow-up. We suggest a timeline for saying good-bye (Table) and some strategies to ease the transition.

Table

Timeline for transferring your patient’s care

| Issues to discuss/explore | |

|---|---|

| 6 months before departure | Determine which issues patient would like to address before transfer Current or past medications |

| 1 month before departure | Focus on closure Avoid addressing new issues Avoid changing medications or session time, day, or frequency Go over transfer summary |

| Final session | Give 1 to 2 prescription refills Encourage patient to follow up with new doctor End session on positive note |

Starting the conversation

Inform the patient of your approximate departure date as soon as possible. Most residents, for example, should have this conversation in January, allowing approximately 6 months to address issues your departure may bring up. Don’t be surprised if your patient does not recall this conversation, however, because he or she might unconsciously repress this information. You might have to discuss your departure several times before it becomes “real” for your patient.

Identify specific issues to address before transferring the patient’s care. For example, explore whether any medications need to be changed.

Tell your patient you would like to write the transfer summary together, and encourage him or her to think about what information to include. If another physician transferred the patient to you, inquire about that process. Did the earlier physician do or say something that was helpful?

Initiating transfer of care

Encourage your patient to talk about feelings related to the transfer by asking how he or she thinks the process will go. Don’t assume your patient is anxious or upset about the change, however. Some patients “bond” to the clinic rather than to a particular doctor.

Be alert for unconscious communication about your impending departure. For example, your patient might talk about others who have left in the past. Consider these statements as opportunities to discuss your departure against the backdrop of other losses and changes.

Patients might unconsciously act out in response to your upcoming departure. For example, a patient who has faithfully attended appointments might “accidentally” miss a visit or discontinue 1 or more medications.

Examine your feelings about the impending transfer of care. Guard against attributing your feelings about the process to your patient. If you find that these feelings lead to difficulty helping your patient find closure, consider consulting with a colleague or mentor.

1 month before the transfer

Your patient might initiate more intense work than in the past. Your impending departure might make it seem safer to share previously undiscussed information because there is little time to explore it.

Although you may be tempted to take advantage of your patient’s impulse, carefully assess this strategy. This is the time to work toward closure, rather than delving into new areas. Keep treatment structured; avoid increasing or decreasing the frequency of visits as you approach the last session.

Also avoid changing the patient’s medication regimen, if possible. If your patient is anxious about your departure, new medication side effects might exacerbate this anxiety.

If possible, personally introduce your patient to the new physician and discuss the transfer summary. Don’t say that the new doctor is “really good.” The qualities you like about this clinician might not appeal to the patient. Encourage the patient to “interview” the new physician.

Don’t discuss what you will be doing after you leave. If the patient asks, talk about your plans in general terms. Detailed or persistent questioning might have psychological meaning and could be discussed in psychotherapy.

The last session

Write 1 or 2 prescription refills. Many patients are concerned about a possible delay in starting treatment with the new physician, and adequate refills may allay fears about obtaining medication. Having refills also may act as a temporary “transitional object” until the patient feels comfortable with the new physician.

Tell your patient that many individuals don’t follow up with a new physician, but it is important to do so. Discussing this phenomenon may increase the probability that your patient will follow up because you can talk about his or her concerns about seeing a new physician or ending treatment with you.

Don’t agree to correspond with the patient after you transfer care. Further communication might interfere with the new therapeutic relationship. The patient might communicate clinical concerns to you, not to the new physician.

Don’t initiate a hug at the end of the session. If your patient initiates a hug or a handshake, you may accept it if you are comfortable with physical contact. End the session on a positive note, and express your best wishes for the patient’s continued growth and well-being.

Still having problems?

If the transition of your patient’s care is unusually difficult, do not hesitate to ask a supervisor or colleague for assistance.

Dr. Kay is instructor in psychiatry and Dr. Mago is assistant professor of psychiatry, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA.

Transferring to another psychiatrist can distress mental health patients and disrupt treatment, whether you part ways with them because of an insurance change or relocation. A smooth transfer helps maintain patients’ clinical progress and reduces the risk of losing them to follow-up. We suggest a timeline for saying good-bye (Table) and some strategies to ease the transition.

Table

Timeline for transferring your patient’s care

| Issues to discuss/explore | |

|---|---|

| 6 months before departure | Determine which issues patient would like to address before transfer Current or past medications |

| 1 month before departure | Focus on closure Avoid addressing new issues Avoid changing medications or session time, day, or frequency Go over transfer summary |

| Final session | Give 1 to 2 prescription refills Encourage patient to follow up with new doctor End session on positive note |

Starting the conversation

Inform the patient of your approximate departure date as soon as possible. Most residents, for example, should have this conversation in January, allowing approximately 6 months to address issues your departure may bring up. Don’t be surprised if your patient does not recall this conversation, however, because he or she might unconsciously repress this information. You might have to discuss your departure several times before it becomes “real” for your patient.

Identify specific issues to address before transferring the patient’s care. For example, explore whether any medications need to be changed.

Tell your patient you would like to write the transfer summary together, and encourage him or her to think about what information to include. If another physician transferred the patient to you, inquire about that process. Did the earlier physician do or say something that was helpful?

Initiating transfer of care

Encourage your patient to talk about feelings related to the transfer by asking how he or she thinks the process will go. Don’t assume your patient is anxious or upset about the change, however. Some patients “bond” to the clinic rather than to a particular doctor.

Be alert for unconscious communication about your impending departure. For example, your patient might talk about others who have left in the past. Consider these statements as opportunities to discuss your departure against the backdrop of other losses and changes.

Patients might unconsciously act out in response to your upcoming departure. For example, a patient who has faithfully attended appointments might “accidentally” miss a visit or discontinue 1 or more medications.

Examine your feelings about the impending transfer of care. Guard against attributing your feelings about the process to your patient. If you find that these feelings lead to difficulty helping your patient find closure, consider consulting with a colleague or mentor.

1 month before the transfer

Your patient might initiate more intense work than in the past. Your impending departure might make it seem safer to share previously undiscussed information because there is little time to explore it.

Although you may be tempted to take advantage of your patient’s impulse, carefully assess this strategy. This is the time to work toward closure, rather than delving into new areas. Keep treatment structured; avoid increasing or decreasing the frequency of visits as you approach the last session.

Also avoid changing the patient’s medication regimen, if possible. If your patient is anxious about your departure, new medication side effects might exacerbate this anxiety.

If possible, personally introduce your patient to the new physician and discuss the transfer summary. Don’t say that the new doctor is “really good.” The qualities you like about this clinician might not appeal to the patient. Encourage the patient to “interview” the new physician.

Don’t discuss what you will be doing after you leave. If the patient asks, talk about your plans in general terms. Detailed or persistent questioning might have psychological meaning and could be discussed in psychotherapy.

The last session

Write 1 or 2 prescription refills. Many patients are concerned about a possible delay in starting treatment with the new physician, and adequate refills may allay fears about obtaining medication. Having refills also may act as a temporary “transitional object” until the patient feels comfortable with the new physician.

Tell your patient that many individuals don’t follow up with a new physician, but it is important to do so. Discussing this phenomenon may increase the probability that your patient will follow up because you can talk about his or her concerns about seeing a new physician or ending treatment with you.

Don’t agree to correspond with the patient after you transfer care. Further communication might interfere with the new therapeutic relationship. The patient might communicate clinical concerns to you, not to the new physician.

Don’t initiate a hug at the end of the session. If your patient initiates a hug or a handshake, you may accept it if you are comfortable with physical contact. End the session on a positive note, and express your best wishes for the patient’s continued growth and well-being.

Still having problems?

If the transition of your patient’s care is unusually difficult, do not hesitate to ask a supervisor or colleague for assistance.

Transferring to another psychiatrist can distress mental health patients and disrupt treatment, whether you part ways with them because of an insurance change or relocation. A smooth transfer helps maintain patients’ clinical progress and reduces the risk of losing them to follow-up. We suggest a timeline for saying good-bye (Table) and some strategies to ease the transition.

Table

Timeline for transferring your patient’s care

| Issues to discuss/explore | |

|---|---|

| 6 months before departure | Determine which issues patient would like to address before transfer Current or past medications |

| 1 month before departure | Focus on closure Avoid addressing new issues Avoid changing medications or session time, day, or frequency Go over transfer summary |

| Final session | Give 1 to 2 prescription refills Encourage patient to follow up with new doctor End session on positive note |

Starting the conversation

Inform the patient of your approximate departure date as soon as possible. Most residents, for example, should have this conversation in January, allowing approximately 6 months to address issues your departure may bring up. Don’t be surprised if your patient does not recall this conversation, however, because he or she might unconsciously repress this information. You might have to discuss your departure several times before it becomes “real” for your patient.

Identify specific issues to address before transferring the patient’s care. For example, explore whether any medications need to be changed.

Tell your patient you would like to write the transfer summary together, and encourage him or her to think about what information to include. If another physician transferred the patient to you, inquire about that process. Did the earlier physician do or say something that was helpful?

Initiating transfer of care

Encourage your patient to talk about feelings related to the transfer by asking how he or she thinks the process will go. Don’t assume your patient is anxious or upset about the change, however. Some patients “bond” to the clinic rather than to a particular doctor.

Be alert for unconscious communication about your impending departure. For example, your patient might talk about others who have left in the past. Consider these statements as opportunities to discuss your departure against the backdrop of other losses and changes.

Patients might unconsciously act out in response to your upcoming departure. For example, a patient who has faithfully attended appointments might “accidentally” miss a visit or discontinue 1 or more medications.

Examine your feelings about the impending transfer of care. Guard against attributing your feelings about the process to your patient. If you find that these feelings lead to difficulty helping your patient find closure, consider consulting with a colleague or mentor.

1 month before the transfer

Your patient might initiate more intense work than in the past. Your impending departure might make it seem safer to share previously undiscussed information because there is little time to explore it.

Although you may be tempted to take advantage of your patient’s impulse, carefully assess this strategy. This is the time to work toward closure, rather than delving into new areas. Keep treatment structured; avoid increasing or decreasing the frequency of visits as you approach the last session.

Also avoid changing the patient’s medication regimen, if possible. If your patient is anxious about your departure, new medication side effects might exacerbate this anxiety.

If possible, personally introduce your patient to the new physician and discuss the transfer summary. Don’t say that the new doctor is “really good.” The qualities you like about this clinician might not appeal to the patient. Encourage the patient to “interview” the new physician.

Don’t discuss what you will be doing after you leave. If the patient asks, talk about your plans in general terms. Detailed or persistent questioning might have psychological meaning and could be discussed in psychotherapy.

The last session

Write 1 or 2 prescription refills. Many patients are concerned about a possible delay in starting treatment with the new physician, and adequate refills may allay fears about obtaining medication. Having refills also may act as a temporary “transitional object” until the patient feels comfortable with the new physician.

Tell your patient that many individuals don’t follow up with a new physician, but it is important to do so. Discussing this phenomenon may increase the probability that your patient will follow up because you can talk about his or her concerns about seeing a new physician or ending treatment with you.

Don’t agree to correspond with the patient after you transfer care. Further communication might interfere with the new therapeutic relationship. The patient might communicate clinical concerns to you, not to the new physician.

Don’t initiate a hug at the end of the session. If your patient initiates a hug or a handshake, you may accept it if you are comfortable with physical contact. End the session on a positive note, and express your best wishes for the patient’s continued growth and well-being.

Still having problems?

If the transition of your patient’s care is unusually difficult, do not hesitate to ask a supervisor or colleague for assistance.

Dr. Kay is instructor in psychiatry and Dr. Mago is assistant professor of psychiatry, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Kay is instructor in psychiatry and Dr. Mago is assistant professor of psychiatry, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA.