User login

UPDATE ON MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY

- Applying single-incision laparoscopic surgery to gyn practice: What’s involved

Russell P. Atkin, MD; Michael L. Nimaroff, MD; Vrunda Bhavsar, MD (April 2011) - 10 practical, evidence-based suggestions to improve your minimally invasive surgical skills now

Catherine A. Matthews, MD (April 2011)

The uterine leiomyoma is the most common tumor of the female genital tract. Seventy percent of white women and 80% of black women develop one or more of these tumors by the time they reach 50 years, and the myomas are clinically apparent in 25% of patients.1,2 When a fibroid is submucosal, it is often associated with menorrhagia, abnormal uterine bleeding, and infertility.2-4

In this article, I describe three aspects of managing leiomyomata:

- ways of classifying the tumor to better predict the blood loss, operative time and morbidity associated with removal

- the indications for hysteroscopic myomectomy and polypectomy

- new tools for the removal of polyps and myomas.

Preoperative assessment of submucosal myomas is essential

Lasmar RB, Barrozo PR, Dias R, Oliveira MA. Submucous myomas: a new presurgical classification to evaluate the viability of hysteroscopic surgical treatment—preliminary report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(4):308–311.

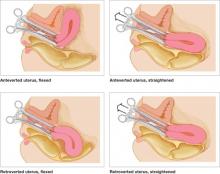

Wamsteker and colleagues were the first to propose a system for classifying myoma position within the uterine cavity as a means of estimating the degree of difficulty of resectoscopic removal.5 The European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) later adopted this system, which is now known by its acronym. According to the ESGE system, myomas that lie entirely within the uterine cavity (Type 0) are easier to remove, require less operative time, and involve less fluid deficit and blood loss than myomas that invade the myometrium to varying degrees (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 ESGE classification

Submucosal myomas are classified as Type 0, Type I, or Type II, according to the degree of myometrial penetration.When more than 50% of a tumor penetrates the myometrium (Type II), the risk of excessive intraoperative fluid absorption is elevated, along with the risk of bleeding and the likelihood of electrolyte abnormalities with the use of non-electrolyte fluid media. Type II tumors also increase operative time and the likelihood that additional procedures will be needed because of incomplete resection—even in the hands of expert hysteroscopic surgeons.5

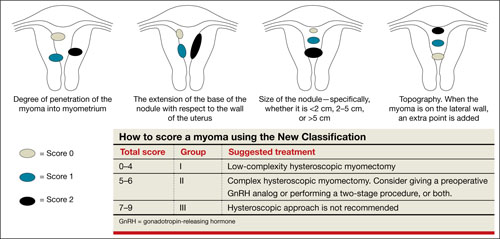

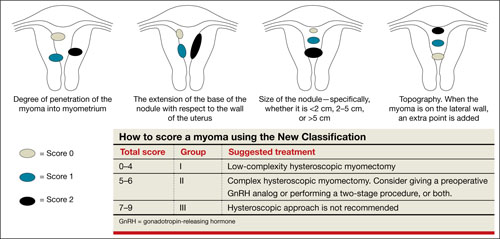

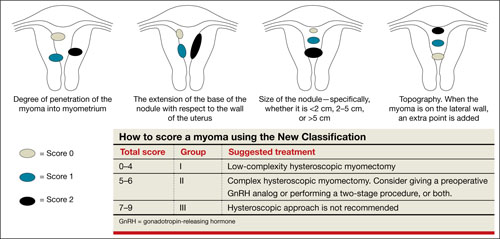

FIGURE 2 New classification

New classification system increases accuracy

Lasmar and colleagues devised a new system for preoperative assessment of submucosal myomas, hoping to estimate more precisely the likelihood of successful removal via resectoscopy. They call their system the New Classification (NC). Besides taking into account the degree of penetration into the myometrium, they consider the percentage of uterine wall encompassed by the myoma and the location of the myoma within the uterus (i.e., fundus, body, or lower segment) (FIGURE 2). The total score is used to categorize the tumor into Group I, II, or III to estimate the likelihood of successful removal.

In devising the system, Lasmar and colleagues used the NC and ESGE systems to analyze 55 myomectomy cases involving 57 myomas. They found that the NC more accurately predicts differences between Groups I and II in regard to completed procedures, fluid deficit, and operative time.

Preoperative hysteroscopic evaluation of submucosal myomas is essential and reliable using the New Classification system.

Hysteroscopic removal of myomas and polyps

yields multiple benefits

Shokeir T, El-Shafei M, Yousef H, Allam AF, Sadek E. Submucous myomas and their implications in the pregnancy rates of patients with otherwise unexplained primary infertility undergoing hysteroscopic myomectomy: a randomized matched control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):724–729.

Rackow BW, Jorgensen E, Taylor HS. Endometrial polyps affect uterine receptivity [published online ahead of print January 24, 2011]. Fertil Steril. doi 10.1016/j. fertnstert.2010.12.034.

Afifi K, Anand S. Nallapeta S, Gelbaya TA. Management of endometrial polyps in subfertile women: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;151(2):117–121.

Studies evaluating the association between infertility and submucosal fibroids have been controversial because the exact mechanism has not been identified. However, new evidence suggests a molecular causal relationship, and Pritts and colleagues demonstrated improved fertility after submucosal myomectomy.3,6

More recently, Shokeir and coworkers conducted a prospective, randomized, age-matched, controlled trial to explore the effects of hysteroscopic myomectomy on otherwise unexplained primary infertility. They enrolled 215 women who had infertility longer than 12 months and who had their fibroids assessed by means of ultrasonography and classified according to the ESGE system.

Women who underwent myomectomy were twice as likely as women in the control group to become pregnant (relative risk = 2.1; 95% confidence interval = 1.5–2.9). Women who had Type 0 and Type I myomas removed had significantly higher pregnancy rates than women in the control group (P < .001). No statistically significant difference in the pregnancy rate between groups was found for Type II myomas.

Polyps may also affect fertility

Rackow and coworkers demonstrated that endometrial polyps affect uterine receptivity on the molecular level, suggesting a relationship between endometrial polyps and infertility. And after a systematic review of endometrial polyps in women who had subfertility, Afifi and colleagues concluded that polypectomy can improve fertility, especially when assisted reproductive technologies are planned.

Myomas, polyps also contribute to bleeding abnormalities

Submucosal myomas have been associated with bleeding abnormalities, such as heavy menstrual bleeding and menopausal bleeding. Although the precise mechanism is unknown by which these bleeding abnormalities arise in the presence of submucosal fibroids, abnormalities within the endometrium or myometrium may play a role at the genetic and molecular level.7,8 There is clear evidence supporting hysteroscopic removal of submucosal fibroids to improve bleeding abnormalities.9,10

Hysteroscopic removal of eSge type 0 and type i submucosal myomas improves the pregnancy rate for patients who have otherwise unexplained primary infertility. Removal of endometrial polyps is also recommended to improve fertility.

Besides improving fertility, hysteroscopic removal of submucosal myomas and endometrial polyps improves menorrhagia and irregular and abnormal uterine bleeding.

Hysteroscopic morcellators offer advantages over traditional resectoscopy, making hysteroscopic myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas safer and more feasible for gynecologic surgeons. They allow resection using saline, operate without electrical energy, and utilize vacuum suction to remove tissue fragments from the uterine cavity.

Hysteroscopic morcellators ease the task of myomectomy

Hysteroscopic removal of submucosal myomas and polyps is an effective treatment for women who experience bleeding abnormalities or infertility, but the potential for complications deters many gynecologists from performing resectoscopic myomectomy.

Use of a monopolar loop electrode (VIDEO 1) requires an electrolyte-free distention medium, such as 1.5% glycine or 3% sorbitol, and intravasation of these fluids must be limited to minimize the risk of complications such as hyponatremia, cardiovascular compromise, cerebral edema, and, even, death.12 Although the use of normal saline with bipolar resectoscopic instrumentation (VIDEO 2) and automated fluid-management systems reduces the risk of fluid overload, it does not eliminate it entirely, and fluid balance must be carefully scrutinized.13

Intrauterine electrosurgery can burn pelvic organs if an activated electrode perforates the uterine wall and makes contact with bowel or other organs. Burns to the cervix, vagina, and vulva have also been reported when monopolar resectoscopic insulation fails or monopolar electrical current is inadvertently diverted.12

In addition, unless one uses tissue-vaporizing electrodes (VIDEO 3) or is equipped

with newer instrumentation that allows tissue to be removed through the operative sheath of the resectoscope, the myoma must be extracted in pieces, often with repeated removal and reinsertion of the resectoscope and grasping instruments, increasing the risk of cervical injury or uterine perforation with each placement.

Another variable that deters hysteroscopic myomectomy is the lack of training at the residency level. The typical ObGyn resident graduating between 2002 and 2007 had performed a median of only 40 to 51 operative hysteroscopic procedures by the time of graduation.14 This statistic suggests that few residency programs provide adequate training for more demanding hysteroscopic surgeries.

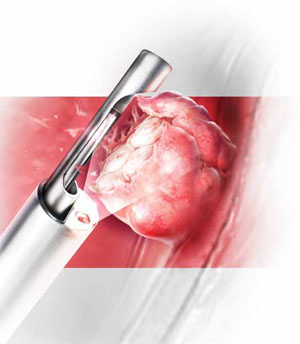

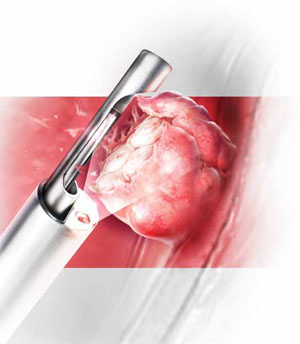

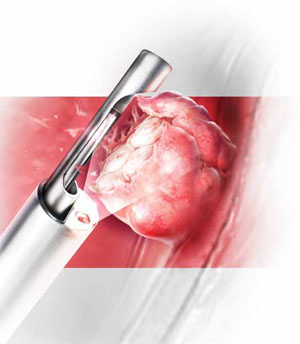

Mechanical morcellators facilitate tissue removal

Hysteroscopic morcellators offer advantages over traditional resectoscopy, making hysteroscopic myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas safer and more feasible for gynecologic surgeons. These morcellators allow resection of a myoma using saline, minimizing the hazards of fluid overload. Because they are mechanical devices that do not require electrical energy, the potential for thermal injury is eliminated.

Mechanical morcellators utilize vacuum suction to remove tissue fragments from the uterine cavity, maintaining a tissue-free operative environment and eliminating the need for repeated manual removal. This feature also reduces the risks of perforation, creation of a false passageway, and gas embolus that have been linked to instrument reinsertion and manual removal of tissue fragments.12

Furthermore, mechanical morcellators are easy to use, reducing operative time and fluid deficit.

Removing Type II myomas with a hysteroscopic morcellator may pose a challenge, however, because of significant myometrial penetration. In addition, bleeding is more likely during removal of a Type II myoma than during removal of other types of tumors, necessitating the use of electric current to address it appropriately. Surgeons who are experienced using the morcellator can overcome these challenges by avoiding the myometrial interface and allowing uterine expulsive contractions to push the myoma into the cavity, making it unnecessary to penetrate the myometrium with the instrument. Thorough preoperative evaluation of Type II myomas is recommended, keeping in mind that removal may be safer and more effective using electrosurgical loop resection.

Option 1: TRUCLEAR morcellator

The TRUCLEAR Hysteroscopic Morcellator (Smith & Nephew) was FDA-approved in 2005 as the first intrauterine mechanical morcellator (VIDEO 4). It requires a dedicated fluid pump and has different instrumentation for myomas and polyps. For myomas, the instrument consists of a rotating tube that reciprocates within an outer 4-mm tube. Both tubes have windows at the end with cutting edges. A vacuum connected to the inner tube provides controlled suction that pulls the tissue into the window on the outer tube and cuts it as the inner tube rotates (VIDEO 5).

For polyps, both inner and outer tubes have oscillating serrated edges on each window (VIDEO 6).

Both instruments are used through a 9-mm offset rod-lens continuous-flow hysteroscope.

In a retrospective analysis, the TRUCLEAR morcellator reduced operative time by about two thirds for polyps and one half for Type 0 and Type I myomas, compared with monopolar loop resection.15 A later study of inexperienced ObGyn residents demonstrated shorter operative times and lower total fluid deficits for the TRUCLEAR morcellator, compared with resectoscopic procedures overall, during polypectomy and myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas.16

Smith & Nephew recently introduced a smaller set of instruments, including a 2.9-mm blade for removal of polyps through a 5.6-mm continuous-flow hysteroscope. However, the new instruments have not yet been approved by the FDA and are unavailable within the United States.

Option 2: MyoSure

The MyoSure Tissue Removal System (Hologic) was FDA-approved in 2009. The hand piece is a rotating and reciprocating 2-mm blade within a 3-mm outer tube. The cutter is connected to a vacuum source that aspirates resected tissue through a side-facing cutting window in the outer tube. The system utilizes standard hysteroscopy set-up for fluid inflow and suction. The instrument is placed through an offset lens continuous-flow hysteroscope with an outer diameter of

6.25 mm. The smaller diameter reduces the amount of cervical dilation required, as well as the risk of uterine perforation.

The smaller size of the instrument renders it ideal for an office setting. Miller and colleagues demonstrated its safety and efficacy for office removal of polyps and myomas (VIDEO 7; VIDEO 8).17

Inadequate reimbursement?

Although both morcellators simplify hysteroscopic myomectomy and polypectomy, insurance reimbursement does not yet differentiate between places of service—unlike other in-office procedures that take into account the cost of the procedural device (see “Reimbursement is limited for hysteroscopic myomectomy in an office setting”). Until the relative value unit (RVU) is modified to reflect this cost, office use of the hysteroscopic morcellator for myomectomy and polypectomy will be financially restrictive to the gynecologist in private practice. Nevertheless, both instruments are easy to use and offer improved safety, increasing access to uterine-preserving surgery.

Thanks to Dr. Andrew I. Brill and Dr. William H. Parker for their thoughtful review of this article.

Since the inception of the resource-based relative value scale, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have provided for different levels of payment to physicians, depending on the place of service and the extent of work involved. The relative value units (RVUs) established for each clinical service are based on three components:

- physician work

- practice expense

- malpractice expense.

The practice expense includes supplies, equipment, clinical and administrative staff, and renting and leasing of space.

When a physician provides a service in a hospital setting or outpatient clinic or surgery unit, the practice expense is lower because the hospital or outpatient facility shoulders those costs. In an office setting, however, the physician practice incurs the full expense of providing the service. In most cases, therefore, the practice is reimbursed at a higher total RVU for office procedures.

The “place of service” code required on your claim form lets the payer know whether the service was rendered in your office (code 11) or a facility such as a hospital or outpatient surgery center (codes 21–24). Physicians who work out of a hospital-owned facility—i.e., physicians who are employed by a hospital—would bill for a facility place of service rather than an office.

The difference in RVUs can be significant. For example, hysteroscopic sterilization (CPT code 58565) has two different RVUs, depending on whether the service is performed in a facility or office (TABLE). However, although hysteroscopic myomectomy can now be safely performed in the office setting for small, less invasive myomas, CMS has not yet assigned a place of service differential for this procedure (CPT code 58561). In other words, CMS has determined that hysteroscopic myomectomy—by definition or practice—is rarely or never performed outside a hospital or outpatient facility.

Medicare reimbursement for hysteroscopic procedures

| Procedure | CPT code | Relative value units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facility | Office | ||

| Sterilization | 58565 | 12.90 | 56.66 |

| Endometrial ablation | 58563 | 10.23 | 52.05 |

| Cryoablation | 58356 | 10.34 | 58.92 |

| Myomectomy | 58561 | 16.33 | NA |

| Polypectomy (with dilation and curettage, biopsy) | 58558 | 7.95 | 10.60 |

| To determine reimbursement, multiply the RVU by the Medicare conversion factor, which is $33.9764 | |||

When contracting with a private payer, be sure to ask how the payer reimburses for hysteroscopic myomectomy in an office setting. Payers that do not include a place of service differential may be amenable to negotiation if you can demonstrate that extra compensation can actually save them money and maintain high-quality patient care.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Day Baird D, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188(1):100-107.

2. Lasmar RB, Barrozo PR, Dias R, Oliveira MA. Submucous myomas: A new presurgical classification to evaluate the viability of hysteroscopic surgical treatment—Preliminary report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;12(4):308-311.

3. Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1215-1223.

4. Shokeir T, El-Shafei M, Yousef H, Allam AF, Sadek E. Submucous myomas and their implications in the pregnancy rates of patients with otherwise unexplained primary infertility undergoing hysteroscopic myomectomy: a randomized matched control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):724-729.

5. Wamsteker K, Emanuel MH, de Kruif JH. Transcervical hysteroscopic resection of submucous fibroids for abnormal uterine bleeding: results regarding the degree of intramural extension. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82(5):736-740.

6. Rackow BW, Taylor HS. Submucosal uterine leiomyomas have a global effect on molecular determinants of endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(6):2027-2034.

7. Stewart EA, Nowak RA. Leiomyoma-related bleeding: a classic hypothesis updated for the molecular era. Human Repro Update. 1996;2(4):295-306.

8. Laughlin SK, Stewart EA. Uterine leiomyomas. Individualizing the approach to a heterogeneous condition. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 pt 1):396-403.

9. Loffer FD. Improving results of hysteroscopic submucosal myomectomy for menorrhagia by concomitant endometrial ablation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(3):254-260.

10. Emanuel MH, Wamsteker K, Hart AA, Metz G, Lammes FB. Long-term results of hysteroscopic myomectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(5 pt 1):743-748.

11. Nathani F, Clark TJ. Uterine polypectomy in the management of abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(4):260-268.

12. Munro MG. Complications of hysteroscopic and uterine resectoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2010;37(3):399-425.

13. Kung RC, Vilos GA, Thomas B, Penkin P, Zaltz AP, Stabinsky SA. A new bipolar system for performing operative hysteroscopy in normal saline. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6(3):331-336.

14. Miller CE. Training in minimally iInvasive surgery—you say you want a revolution. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(2):113-120.

15. Emanuel MH, Wamsteker K. The intra uterine morcellator: a new hysteroscopic moperating technique to remove intrauterine polyps and myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(1):62-66.

16. Van Dongen H, Emanuel MH, Wolterbeek R, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Hysteroscopic morcellator for removal of intrauterine polyps and myomas: a randomized controlled pilot study among residents in training. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(4):466-471.

17. Miller CE, Glazerman L, Roy K, Lukes A. Clinical evaluation of a new hysteroscopic morcellator—retrospective case review. J Med. 2009;2(3):163-166.

- Applying single-incision laparoscopic surgery to gyn practice: What’s involved

Russell P. Atkin, MD; Michael L. Nimaroff, MD; Vrunda Bhavsar, MD (April 2011) - 10 practical, evidence-based suggestions to improve your minimally invasive surgical skills now

Catherine A. Matthews, MD (April 2011)

The uterine leiomyoma is the most common tumor of the female genital tract. Seventy percent of white women and 80% of black women develop one or more of these tumors by the time they reach 50 years, and the myomas are clinically apparent in 25% of patients.1,2 When a fibroid is submucosal, it is often associated with menorrhagia, abnormal uterine bleeding, and infertility.2-4

In this article, I describe three aspects of managing leiomyomata:

- ways of classifying the tumor to better predict the blood loss, operative time and morbidity associated with removal

- the indications for hysteroscopic myomectomy and polypectomy

- new tools for the removal of polyps and myomas.

Preoperative assessment of submucosal myomas is essential

Lasmar RB, Barrozo PR, Dias R, Oliveira MA. Submucous myomas: a new presurgical classification to evaluate the viability of hysteroscopic surgical treatment—preliminary report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(4):308–311.

Wamsteker and colleagues were the first to propose a system for classifying myoma position within the uterine cavity as a means of estimating the degree of difficulty of resectoscopic removal.5 The European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) later adopted this system, which is now known by its acronym. According to the ESGE system, myomas that lie entirely within the uterine cavity (Type 0) are easier to remove, require less operative time, and involve less fluid deficit and blood loss than myomas that invade the myometrium to varying degrees (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 ESGE classification

Submucosal myomas are classified as Type 0, Type I, or Type II, according to the degree of myometrial penetration.When more than 50% of a tumor penetrates the myometrium (Type II), the risk of excessive intraoperative fluid absorption is elevated, along with the risk of bleeding and the likelihood of electrolyte abnormalities with the use of non-electrolyte fluid media. Type II tumors also increase operative time and the likelihood that additional procedures will be needed because of incomplete resection—even in the hands of expert hysteroscopic surgeons.5

FIGURE 2 New classification

New classification system increases accuracy

Lasmar and colleagues devised a new system for preoperative assessment of submucosal myomas, hoping to estimate more precisely the likelihood of successful removal via resectoscopy. They call their system the New Classification (NC). Besides taking into account the degree of penetration into the myometrium, they consider the percentage of uterine wall encompassed by the myoma and the location of the myoma within the uterus (i.e., fundus, body, or lower segment) (FIGURE 2). The total score is used to categorize the tumor into Group I, II, or III to estimate the likelihood of successful removal.

In devising the system, Lasmar and colleagues used the NC and ESGE systems to analyze 55 myomectomy cases involving 57 myomas. They found that the NC more accurately predicts differences between Groups I and II in regard to completed procedures, fluid deficit, and operative time.

Preoperative hysteroscopic evaluation of submucosal myomas is essential and reliable using the New Classification system.

Hysteroscopic removal of myomas and polyps

yields multiple benefits

Shokeir T, El-Shafei M, Yousef H, Allam AF, Sadek E. Submucous myomas and their implications in the pregnancy rates of patients with otherwise unexplained primary infertility undergoing hysteroscopic myomectomy: a randomized matched control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):724–729.

Rackow BW, Jorgensen E, Taylor HS. Endometrial polyps affect uterine receptivity [published online ahead of print January 24, 2011]. Fertil Steril. doi 10.1016/j. fertnstert.2010.12.034.

Afifi K, Anand S. Nallapeta S, Gelbaya TA. Management of endometrial polyps in subfertile women: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;151(2):117–121.

Studies evaluating the association between infertility and submucosal fibroids have been controversial because the exact mechanism has not been identified. However, new evidence suggests a molecular causal relationship, and Pritts and colleagues demonstrated improved fertility after submucosal myomectomy.3,6

More recently, Shokeir and coworkers conducted a prospective, randomized, age-matched, controlled trial to explore the effects of hysteroscopic myomectomy on otherwise unexplained primary infertility. They enrolled 215 women who had infertility longer than 12 months and who had their fibroids assessed by means of ultrasonography and classified according to the ESGE system.

Women who underwent myomectomy were twice as likely as women in the control group to become pregnant (relative risk = 2.1; 95% confidence interval = 1.5–2.9). Women who had Type 0 and Type I myomas removed had significantly higher pregnancy rates than women in the control group (P < .001). No statistically significant difference in the pregnancy rate between groups was found for Type II myomas.

Polyps may also affect fertility

Rackow and coworkers demonstrated that endometrial polyps affect uterine receptivity on the molecular level, suggesting a relationship between endometrial polyps and infertility. And after a systematic review of endometrial polyps in women who had subfertility, Afifi and colleagues concluded that polypectomy can improve fertility, especially when assisted reproductive technologies are planned.

Myomas, polyps also contribute to bleeding abnormalities

Submucosal myomas have been associated with bleeding abnormalities, such as heavy menstrual bleeding and menopausal bleeding. Although the precise mechanism is unknown by which these bleeding abnormalities arise in the presence of submucosal fibroids, abnormalities within the endometrium or myometrium may play a role at the genetic and molecular level.7,8 There is clear evidence supporting hysteroscopic removal of submucosal fibroids to improve bleeding abnormalities.9,10

Hysteroscopic removal of eSge type 0 and type i submucosal myomas improves the pregnancy rate for patients who have otherwise unexplained primary infertility. Removal of endometrial polyps is also recommended to improve fertility.

Besides improving fertility, hysteroscopic removal of submucosal myomas and endometrial polyps improves menorrhagia and irregular and abnormal uterine bleeding.

Hysteroscopic morcellators offer advantages over traditional resectoscopy, making hysteroscopic myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas safer and more feasible for gynecologic surgeons. They allow resection using saline, operate without electrical energy, and utilize vacuum suction to remove tissue fragments from the uterine cavity.

Hysteroscopic morcellators ease the task of myomectomy

Hysteroscopic removal of submucosal myomas and polyps is an effective treatment for women who experience bleeding abnormalities or infertility, but the potential for complications deters many gynecologists from performing resectoscopic myomectomy.

Use of a monopolar loop electrode (VIDEO 1) requires an electrolyte-free distention medium, such as 1.5% glycine or 3% sorbitol, and intravasation of these fluids must be limited to minimize the risk of complications such as hyponatremia, cardiovascular compromise, cerebral edema, and, even, death.12 Although the use of normal saline with bipolar resectoscopic instrumentation (VIDEO 2) and automated fluid-management systems reduces the risk of fluid overload, it does not eliminate it entirely, and fluid balance must be carefully scrutinized.13

Intrauterine electrosurgery can burn pelvic organs if an activated electrode perforates the uterine wall and makes contact with bowel or other organs. Burns to the cervix, vagina, and vulva have also been reported when monopolar resectoscopic insulation fails or monopolar electrical current is inadvertently diverted.12

In addition, unless one uses tissue-vaporizing electrodes (VIDEO 3) or is equipped

with newer instrumentation that allows tissue to be removed through the operative sheath of the resectoscope, the myoma must be extracted in pieces, often with repeated removal and reinsertion of the resectoscope and grasping instruments, increasing the risk of cervical injury or uterine perforation with each placement.

Another variable that deters hysteroscopic myomectomy is the lack of training at the residency level. The typical ObGyn resident graduating between 2002 and 2007 had performed a median of only 40 to 51 operative hysteroscopic procedures by the time of graduation.14 This statistic suggests that few residency programs provide adequate training for more demanding hysteroscopic surgeries.

Mechanical morcellators facilitate tissue removal

Hysteroscopic morcellators offer advantages over traditional resectoscopy, making hysteroscopic myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas safer and more feasible for gynecologic surgeons. These morcellators allow resection of a myoma using saline, minimizing the hazards of fluid overload. Because they are mechanical devices that do not require electrical energy, the potential for thermal injury is eliminated.

Mechanical morcellators utilize vacuum suction to remove tissue fragments from the uterine cavity, maintaining a tissue-free operative environment and eliminating the need for repeated manual removal. This feature also reduces the risks of perforation, creation of a false passageway, and gas embolus that have been linked to instrument reinsertion and manual removal of tissue fragments.12

Furthermore, mechanical morcellators are easy to use, reducing operative time and fluid deficit.

Removing Type II myomas with a hysteroscopic morcellator may pose a challenge, however, because of significant myometrial penetration. In addition, bleeding is more likely during removal of a Type II myoma than during removal of other types of tumors, necessitating the use of electric current to address it appropriately. Surgeons who are experienced using the morcellator can overcome these challenges by avoiding the myometrial interface and allowing uterine expulsive contractions to push the myoma into the cavity, making it unnecessary to penetrate the myometrium with the instrument. Thorough preoperative evaluation of Type II myomas is recommended, keeping in mind that removal may be safer and more effective using electrosurgical loop resection.

Option 1: TRUCLEAR morcellator

The TRUCLEAR Hysteroscopic Morcellator (Smith & Nephew) was FDA-approved in 2005 as the first intrauterine mechanical morcellator (VIDEO 4). It requires a dedicated fluid pump and has different instrumentation for myomas and polyps. For myomas, the instrument consists of a rotating tube that reciprocates within an outer 4-mm tube. Both tubes have windows at the end with cutting edges. A vacuum connected to the inner tube provides controlled suction that pulls the tissue into the window on the outer tube and cuts it as the inner tube rotates (VIDEO 5).

For polyps, both inner and outer tubes have oscillating serrated edges on each window (VIDEO 6).

Both instruments are used through a 9-mm offset rod-lens continuous-flow hysteroscope.

In a retrospective analysis, the TRUCLEAR morcellator reduced operative time by about two thirds for polyps and one half for Type 0 and Type I myomas, compared with monopolar loop resection.15 A later study of inexperienced ObGyn residents demonstrated shorter operative times and lower total fluid deficits for the TRUCLEAR morcellator, compared with resectoscopic procedures overall, during polypectomy and myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas.16

Smith & Nephew recently introduced a smaller set of instruments, including a 2.9-mm blade for removal of polyps through a 5.6-mm continuous-flow hysteroscope. However, the new instruments have not yet been approved by the FDA and are unavailable within the United States.

Option 2: MyoSure

The MyoSure Tissue Removal System (Hologic) was FDA-approved in 2009. The hand piece is a rotating and reciprocating 2-mm blade within a 3-mm outer tube. The cutter is connected to a vacuum source that aspirates resected tissue through a side-facing cutting window in the outer tube. The system utilizes standard hysteroscopy set-up for fluid inflow and suction. The instrument is placed through an offset lens continuous-flow hysteroscope with an outer diameter of

6.25 mm. The smaller diameter reduces the amount of cervical dilation required, as well as the risk of uterine perforation.

The smaller size of the instrument renders it ideal for an office setting. Miller and colleagues demonstrated its safety and efficacy for office removal of polyps and myomas (VIDEO 7; VIDEO 8).17

Inadequate reimbursement?

Although both morcellators simplify hysteroscopic myomectomy and polypectomy, insurance reimbursement does not yet differentiate between places of service—unlike other in-office procedures that take into account the cost of the procedural device (see “Reimbursement is limited for hysteroscopic myomectomy in an office setting”). Until the relative value unit (RVU) is modified to reflect this cost, office use of the hysteroscopic morcellator for myomectomy and polypectomy will be financially restrictive to the gynecologist in private practice. Nevertheless, both instruments are easy to use and offer improved safety, increasing access to uterine-preserving surgery.

Thanks to Dr. Andrew I. Brill and Dr. William H. Parker for their thoughtful review of this article.

Since the inception of the resource-based relative value scale, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have provided for different levels of payment to physicians, depending on the place of service and the extent of work involved. The relative value units (RVUs) established for each clinical service are based on three components:

- physician work

- practice expense

- malpractice expense.

The practice expense includes supplies, equipment, clinical and administrative staff, and renting and leasing of space.

When a physician provides a service in a hospital setting or outpatient clinic or surgery unit, the practice expense is lower because the hospital or outpatient facility shoulders those costs. In an office setting, however, the physician practice incurs the full expense of providing the service. In most cases, therefore, the practice is reimbursed at a higher total RVU for office procedures.

The “place of service” code required on your claim form lets the payer know whether the service was rendered in your office (code 11) or a facility such as a hospital or outpatient surgery center (codes 21–24). Physicians who work out of a hospital-owned facility—i.e., physicians who are employed by a hospital—would bill for a facility place of service rather than an office.

The difference in RVUs can be significant. For example, hysteroscopic sterilization (CPT code 58565) has two different RVUs, depending on whether the service is performed in a facility or office (TABLE). However, although hysteroscopic myomectomy can now be safely performed in the office setting for small, less invasive myomas, CMS has not yet assigned a place of service differential for this procedure (CPT code 58561). In other words, CMS has determined that hysteroscopic myomectomy—by definition or practice—is rarely or never performed outside a hospital or outpatient facility.

Medicare reimbursement for hysteroscopic procedures

| Procedure | CPT code | Relative value units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facility | Office | ||

| Sterilization | 58565 | 12.90 | 56.66 |

| Endometrial ablation | 58563 | 10.23 | 52.05 |

| Cryoablation | 58356 | 10.34 | 58.92 |

| Myomectomy | 58561 | 16.33 | NA |

| Polypectomy (with dilation and curettage, biopsy) | 58558 | 7.95 | 10.60 |

| To determine reimbursement, multiply the RVU by the Medicare conversion factor, which is $33.9764 | |||

When contracting with a private payer, be sure to ask how the payer reimburses for hysteroscopic myomectomy in an office setting. Payers that do not include a place of service differential may be amenable to negotiation if you can demonstrate that extra compensation can actually save them money and maintain high-quality patient care.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Applying single-incision laparoscopic surgery to gyn practice: What’s involved

Russell P. Atkin, MD; Michael L. Nimaroff, MD; Vrunda Bhavsar, MD (April 2011) - 10 practical, evidence-based suggestions to improve your minimally invasive surgical skills now

Catherine A. Matthews, MD (April 2011)

The uterine leiomyoma is the most common tumor of the female genital tract. Seventy percent of white women and 80% of black women develop one or more of these tumors by the time they reach 50 years, and the myomas are clinically apparent in 25% of patients.1,2 When a fibroid is submucosal, it is often associated with menorrhagia, abnormal uterine bleeding, and infertility.2-4

In this article, I describe three aspects of managing leiomyomata:

- ways of classifying the tumor to better predict the blood loss, operative time and morbidity associated with removal

- the indications for hysteroscopic myomectomy and polypectomy

- new tools for the removal of polyps and myomas.

Preoperative assessment of submucosal myomas is essential

Lasmar RB, Barrozo PR, Dias R, Oliveira MA. Submucous myomas: a new presurgical classification to evaluate the viability of hysteroscopic surgical treatment—preliminary report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(4):308–311.

Wamsteker and colleagues were the first to propose a system for classifying myoma position within the uterine cavity as a means of estimating the degree of difficulty of resectoscopic removal.5 The European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) later adopted this system, which is now known by its acronym. According to the ESGE system, myomas that lie entirely within the uterine cavity (Type 0) are easier to remove, require less operative time, and involve less fluid deficit and blood loss than myomas that invade the myometrium to varying degrees (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 ESGE classification

Submucosal myomas are classified as Type 0, Type I, or Type II, according to the degree of myometrial penetration.When more than 50% of a tumor penetrates the myometrium (Type II), the risk of excessive intraoperative fluid absorption is elevated, along with the risk of bleeding and the likelihood of electrolyte abnormalities with the use of non-electrolyte fluid media. Type II tumors also increase operative time and the likelihood that additional procedures will be needed because of incomplete resection—even in the hands of expert hysteroscopic surgeons.5

FIGURE 2 New classification

New classification system increases accuracy

Lasmar and colleagues devised a new system for preoperative assessment of submucosal myomas, hoping to estimate more precisely the likelihood of successful removal via resectoscopy. They call their system the New Classification (NC). Besides taking into account the degree of penetration into the myometrium, they consider the percentage of uterine wall encompassed by the myoma and the location of the myoma within the uterus (i.e., fundus, body, or lower segment) (FIGURE 2). The total score is used to categorize the tumor into Group I, II, or III to estimate the likelihood of successful removal.

In devising the system, Lasmar and colleagues used the NC and ESGE systems to analyze 55 myomectomy cases involving 57 myomas. They found that the NC more accurately predicts differences between Groups I and II in regard to completed procedures, fluid deficit, and operative time.

Preoperative hysteroscopic evaluation of submucosal myomas is essential and reliable using the New Classification system.

Hysteroscopic removal of myomas and polyps

yields multiple benefits

Shokeir T, El-Shafei M, Yousef H, Allam AF, Sadek E. Submucous myomas and their implications in the pregnancy rates of patients with otherwise unexplained primary infertility undergoing hysteroscopic myomectomy: a randomized matched control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):724–729.

Rackow BW, Jorgensen E, Taylor HS. Endometrial polyps affect uterine receptivity [published online ahead of print January 24, 2011]. Fertil Steril. doi 10.1016/j. fertnstert.2010.12.034.

Afifi K, Anand S. Nallapeta S, Gelbaya TA. Management of endometrial polyps in subfertile women: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;151(2):117–121.

Studies evaluating the association between infertility and submucosal fibroids have been controversial because the exact mechanism has not been identified. However, new evidence suggests a molecular causal relationship, and Pritts and colleagues demonstrated improved fertility after submucosal myomectomy.3,6

More recently, Shokeir and coworkers conducted a prospective, randomized, age-matched, controlled trial to explore the effects of hysteroscopic myomectomy on otherwise unexplained primary infertility. They enrolled 215 women who had infertility longer than 12 months and who had their fibroids assessed by means of ultrasonography and classified according to the ESGE system.

Women who underwent myomectomy were twice as likely as women in the control group to become pregnant (relative risk = 2.1; 95% confidence interval = 1.5–2.9). Women who had Type 0 and Type I myomas removed had significantly higher pregnancy rates than women in the control group (P < .001). No statistically significant difference in the pregnancy rate between groups was found for Type II myomas.

Polyps may also affect fertility

Rackow and coworkers demonstrated that endometrial polyps affect uterine receptivity on the molecular level, suggesting a relationship between endometrial polyps and infertility. And after a systematic review of endometrial polyps in women who had subfertility, Afifi and colleagues concluded that polypectomy can improve fertility, especially when assisted reproductive technologies are planned.

Myomas, polyps also contribute to bleeding abnormalities

Submucosal myomas have been associated with bleeding abnormalities, such as heavy menstrual bleeding and menopausal bleeding. Although the precise mechanism is unknown by which these bleeding abnormalities arise in the presence of submucosal fibroids, abnormalities within the endometrium or myometrium may play a role at the genetic and molecular level.7,8 There is clear evidence supporting hysteroscopic removal of submucosal fibroids to improve bleeding abnormalities.9,10

Hysteroscopic removal of eSge type 0 and type i submucosal myomas improves the pregnancy rate for patients who have otherwise unexplained primary infertility. Removal of endometrial polyps is also recommended to improve fertility.

Besides improving fertility, hysteroscopic removal of submucosal myomas and endometrial polyps improves menorrhagia and irregular and abnormal uterine bleeding.

Hysteroscopic morcellators offer advantages over traditional resectoscopy, making hysteroscopic myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas safer and more feasible for gynecologic surgeons. They allow resection using saline, operate without electrical energy, and utilize vacuum suction to remove tissue fragments from the uterine cavity.

Hysteroscopic morcellators ease the task of myomectomy

Hysteroscopic removal of submucosal myomas and polyps is an effective treatment for women who experience bleeding abnormalities or infertility, but the potential for complications deters many gynecologists from performing resectoscopic myomectomy.

Use of a monopolar loop electrode (VIDEO 1) requires an electrolyte-free distention medium, such as 1.5% glycine or 3% sorbitol, and intravasation of these fluids must be limited to minimize the risk of complications such as hyponatremia, cardiovascular compromise, cerebral edema, and, even, death.12 Although the use of normal saline with bipolar resectoscopic instrumentation (VIDEO 2) and automated fluid-management systems reduces the risk of fluid overload, it does not eliminate it entirely, and fluid balance must be carefully scrutinized.13

Intrauterine electrosurgery can burn pelvic organs if an activated electrode perforates the uterine wall and makes contact with bowel or other organs. Burns to the cervix, vagina, and vulva have also been reported when monopolar resectoscopic insulation fails or monopolar electrical current is inadvertently diverted.12

In addition, unless one uses tissue-vaporizing electrodes (VIDEO 3) or is equipped

with newer instrumentation that allows tissue to be removed through the operative sheath of the resectoscope, the myoma must be extracted in pieces, often with repeated removal and reinsertion of the resectoscope and grasping instruments, increasing the risk of cervical injury or uterine perforation with each placement.

Another variable that deters hysteroscopic myomectomy is the lack of training at the residency level. The typical ObGyn resident graduating between 2002 and 2007 had performed a median of only 40 to 51 operative hysteroscopic procedures by the time of graduation.14 This statistic suggests that few residency programs provide adequate training for more demanding hysteroscopic surgeries.

Mechanical morcellators facilitate tissue removal

Hysteroscopic morcellators offer advantages over traditional resectoscopy, making hysteroscopic myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas safer and more feasible for gynecologic surgeons. These morcellators allow resection of a myoma using saline, minimizing the hazards of fluid overload. Because they are mechanical devices that do not require electrical energy, the potential for thermal injury is eliminated.

Mechanical morcellators utilize vacuum suction to remove tissue fragments from the uterine cavity, maintaining a tissue-free operative environment and eliminating the need for repeated manual removal. This feature also reduces the risks of perforation, creation of a false passageway, and gas embolus that have been linked to instrument reinsertion and manual removal of tissue fragments.12

Furthermore, mechanical morcellators are easy to use, reducing operative time and fluid deficit.

Removing Type II myomas with a hysteroscopic morcellator may pose a challenge, however, because of significant myometrial penetration. In addition, bleeding is more likely during removal of a Type II myoma than during removal of other types of tumors, necessitating the use of electric current to address it appropriately. Surgeons who are experienced using the morcellator can overcome these challenges by avoiding the myometrial interface and allowing uterine expulsive contractions to push the myoma into the cavity, making it unnecessary to penetrate the myometrium with the instrument. Thorough preoperative evaluation of Type II myomas is recommended, keeping in mind that removal may be safer and more effective using electrosurgical loop resection.

Option 1: TRUCLEAR morcellator

The TRUCLEAR Hysteroscopic Morcellator (Smith & Nephew) was FDA-approved in 2005 as the first intrauterine mechanical morcellator (VIDEO 4). It requires a dedicated fluid pump and has different instrumentation for myomas and polyps. For myomas, the instrument consists of a rotating tube that reciprocates within an outer 4-mm tube. Both tubes have windows at the end with cutting edges. A vacuum connected to the inner tube provides controlled suction that pulls the tissue into the window on the outer tube and cuts it as the inner tube rotates (VIDEO 5).

For polyps, both inner and outer tubes have oscillating serrated edges on each window (VIDEO 6).

Both instruments are used through a 9-mm offset rod-lens continuous-flow hysteroscope.

In a retrospective analysis, the TRUCLEAR morcellator reduced operative time by about two thirds for polyps and one half for Type 0 and Type I myomas, compared with monopolar loop resection.15 A later study of inexperienced ObGyn residents demonstrated shorter operative times and lower total fluid deficits for the TRUCLEAR morcellator, compared with resectoscopic procedures overall, during polypectomy and myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas.16

Smith & Nephew recently introduced a smaller set of instruments, including a 2.9-mm blade for removal of polyps through a 5.6-mm continuous-flow hysteroscope. However, the new instruments have not yet been approved by the FDA and are unavailable within the United States.

Option 2: MyoSure

The MyoSure Tissue Removal System (Hologic) was FDA-approved in 2009. The hand piece is a rotating and reciprocating 2-mm blade within a 3-mm outer tube. The cutter is connected to a vacuum source that aspirates resected tissue through a side-facing cutting window in the outer tube. The system utilizes standard hysteroscopy set-up for fluid inflow and suction. The instrument is placed through an offset lens continuous-flow hysteroscope with an outer diameter of

6.25 mm. The smaller diameter reduces the amount of cervical dilation required, as well as the risk of uterine perforation.

The smaller size of the instrument renders it ideal for an office setting. Miller and colleagues demonstrated its safety and efficacy for office removal of polyps and myomas (VIDEO 7; VIDEO 8).17

Inadequate reimbursement?

Although both morcellators simplify hysteroscopic myomectomy and polypectomy, insurance reimbursement does not yet differentiate between places of service—unlike other in-office procedures that take into account the cost of the procedural device (see “Reimbursement is limited for hysteroscopic myomectomy in an office setting”). Until the relative value unit (RVU) is modified to reflect this cost, office use of the hysteroscopic morcellator for myomectomy and polypectomy will be financially restrictive to the gynecologist in private practice. Nevertheless, both instruments are easy to use and offer improved safety, increasing access to uterine-preserving surgery.

Thanks to Dr. Andrew I. Brill and Dr. William H. Parker for their thoughtful review of this article.

Since the inception of the resource-based relative value scale, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have provided for different levels of payment to physicians, depending on the place of service and the extent of work involved. The relative value units (RVUs) established for each clinical service are based on three components:

- physician work

- practice expense

- malpractice expense.

The practice expense includes supplies, equipment, clinical and administrative staff, and renting and leasing of space.

When a physician provides a service in a hospital setting or outpatient clinic or surgery unit, the practice expense is lower because the hospital or outpatient facility shoulders those costs. In an office setting, however, the physician practice incurs the full expense of providing the service. In most cases, therefore, the practice is reimbursed at a higher total RVU for office procedures.

The “place of service” code required on your claim form lets the payer know whether the service was rendered in your office (code 11) or a facility such as a hospital or outpatient surgery center (codes 21–24). Physicians who work out of a hospital-owned facility—i.e., physicians who are employed by a hospital—would bill for a facility place of service rather than an office.

The difference in RVUs can be significant. For example, hysteroscopic sterilization (CPT code 58565) has two different RVUs, depending on whether the service is performed in a facility or office (TABLE). However, although hysteroscopic myomectomy can now be safely performed in the office setting for small, less invasive myomas, CMS has not yet assigned a place of service differential for this procedure (CPT code 58561). In other words, CMS has determined that hysteroscopic myomectomy—by definition or practice—is rarely or never performed outside a hospital or outpatient facility.

Medicare reimbursement for hysteroscopic procedures

| Procedure | CPT code | Relative value units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facility | Office | ||

| Sterilization | 58565 | 12.90 | 56.66 |

| Endometrial ablation | 58563 | 10.23 | 52.05 |

| Cryoablation | 58356 | 10.34 | 58.92 |

| Myomectomy | 58561 | 16.33 | NA |

| Polypectomy (with dilation and curettage, biopsy) | 58558 | 7.95 | 10.60 |

| To determine reimbursement, multiply the RVU by the Medicare conversion factor, which is $33.9764 | |||

When contracting with a private payer, be sure to ask how the payer reimburses for hysteroscopic myomectomy in an office setting. Payers that do not include a place of service differential may be amenable to negotiation if you can demonstrate that extra compensation can actually save them money and maintain high-quality patient care.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Day Baird D, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188(1):100-107.

2. Lasmar RB, Barrozo PR, Dias R, Oliveira MA. Submucous myomas: A new presurgical classification to evaluate the viability of hysteroscopic surgical treatment—Preliminary report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;12(4):308-311.

3. Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1215-1223.

4. Shokeir T, El-Shafei M, Yousef H, Allam AF, Sadek E. Submucous myomas and their implications in the pregnancy rates of patients with otherwise unexplained primary infertility undergoing hysteroscopic myomectomy: a randomized matched control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):724-729.

5. Wamsteker K, Emanuel MH, de Kruif JH. Transcervical hysteroscopic resection of submucous fibroids for abnormal uterine bleeding: results regarding the degree of intramural extension. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82(5):736-740.

6. Rackow BW, Taylor HS. Submucosal uterine leiomyomas have a global effect on molecular determinants of endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(6):2027-2034.

7. Stewart EA, Nowak RA. Leiomyoma-related bleeding: a classic hypothesis updated for the molecular era. Human Repro Update. 1996;2(4):295-306.

8. Laughlin SK, Stewart EA. Uterine leiomyomas. Individualizing the approach to a heterogeneous condition. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 pt 1):396-403.

9. Loffer FD. Improving results of hysteroscopic submucosal myomectomy for menorrhagia by concomitant endometrial ablation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(3):254-260.

10. Emanuel MH, Wamsteker K, Hart AA, Metz G, Lammes FB. Long-term results of hysteroscopic myomectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(5 pt 1):743-748.

11. Nathani F, Clark TJ. Uterine polypectomy in the management of abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(4):260-268.

12. Munro MG. Complications of hysteroscopic and uterine resectoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2010;37(3):399-425.

13. Kung RC, Vilos GA, Thomas B, Penkin P, Zaltz AP, Stabinsky SA. A new bipolar system for performing operative hysteroscopy in normal saline. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6(3):331-336.

14. Miller CE. Training in minimally iInvasive surgery—you say you want a revolution. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(2):113-120.

15. Emanuel MH, Wamsteker K. The intra uterine morcellator: a new hysteroscopic moperating technique to remove intrauterine polyps and myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(1):62-66.

16. Van Dongen H, Emanuel MH, Wolterbeek R, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Hysteroscopic morcellator for removal of intrauterine polyps and myomas: a randomized controlled pilot study among residents in training. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(4):466-471.

17. Miller CE, Glazerman L, Roy K, Lukes A. Clinical evaluation of a new hysteroscopic morcellator—retrospective case review. J Med. 2009;2(3):163-166.

1. Day Baird D, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188(1):100-107.

2. Lasmar RB, Barrozo PR, Dias R, Oliveira MA. Submucous myomas: A new presurgical classification to evaluate the viability of hysteroscopic surgical treatment—Preliminary report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;12(4):308-311.

3. Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1215-1223.

4. Shokeir T, El-Shafei M, Yousef H, Allam AF, Sadek E. Submucous myomas and their implications in the pregnancy rates of patients with otherwise unexplained primary infertility undergoing hysteroscopic myomectomy: a randomized matched control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):724-729.

5. Wamsteker K, Emanuel MH, de Kruif JH. Transcervical hysteroscopic resection of submucous fibroids for abnormal uterine bleeding: results regarding the degree of intramural extension. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82(5):736-740.

6. Rackow BW, Taylor HS. Submucosal uterine leiomyomas have a global effect on molecular determinants of endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(6):2027-2034.

7. Stewart EA, Nowak RA. Leiomyoma-related bleeding: a classic hypothesis updated for the molecular era. Human Repro Update. 1996;2(4):295-306.

8. Laughlin SK, Stewart EA. Uterine leiomyomas. Individualizing the approach to a heterogeneous condition. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 pt 1):396-403.

9. Loffer FD. Improving results of hysteroscopic submucosal myomectomy for menorrhagia by concomitant endometrial ablation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(3):254-260.

10. Emanuel MH, Wamsteker K, Hart AA, Metz G, Lammes FB. Long-term results of hysteroscopic myomectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(5 pt 1):743-748.

11. Nathani F, Clark TJ. Uterine polypectomy in the management of abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(4):260-268.

12. Munro MG. Complications of hysteroscopic and uterine resectoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2010;37(3):399-425.

13. Kung RC, Vilos GA, Thomas B, Penkin P, Zaltz AP, Stabinsky SA. A new bipolar system for performing operative hysteroscopy in normal saline. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6(3):331-336.

14. Miller CE. Training in minimally iInvasive surgery—you say you want a revolution. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(2):113-120.

15. Emanuel MH, Wamsteker K. The intra uterine morcellator: a new hysteroscopic moperating technique to remove intrauterine polyps and myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(1):62-66.

16. Van Dongen H, Emanuel MH, Wolterbeek R, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Hysteroscopic morcellator for removal of intrauterine polyps and myomas: a randomized controlled pilot study among residents in training. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(4):466-471.

17. Miller CE, Glazerman L, Roy K, Lukes A. Clinical evaluation of a new hysteroscopic morcellator—retrospective case review. J Med. 2009;2(3):163-166.

UPDATE: MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY

Endometrial polyps are a relatively common pathology, occurring in 24% to 41% of women who have abnormal bleeding, and in about 10% of asymptomatic women.1,2 Endometrial polyps may be associated with leiomyomas in women who have abnormal bleeding.1-3

Polyps originate as focal hyperplasia of basal endometrium and contain variable amounts of glands, stroma, and blood vessels. Glandular epithelium has higher estrogen- and progesterone-receptor expression than surrounding endometrium, whereas the stromal component of a polyp has hormone receptors similar to endometrium. This suggests that a polyp represents focal hyperplasia that is more glandular than stromal.4

In this Update, I outline the basics of diagnosis and treatment and report on several recent investigations:

- a retrospective analysis from Italy that found that endometrial polyps are associated with advancing age and that any apparent association between polyps and diabetes, hypertension, or obesity is likely age-related

- a cross-sectional study from Norway that found that some asymptomatic polyps regress spontaneously, usually when their length is 10.7 mm or less

- three studies that explore the variables associated with premalignant and malignant polyps

- an investigation of the relationship between endometrial polyps and the background endometrium that found atypical hyperplasia in endometrium remote from the polyp in a significant percentage of women.

Age is the most important variable when assessing a patient for endometrial pathology

Nappi L, Indraccolo U, Di Spiezio Sardo A, et al. Are diabetes, hypertension, and obesity independent risk factors for endometrial polyps? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(2):157–162.

In this retrospective analysis of 353 women who underwent office hysteroscopy, Nappi and co-workers set out to ascertain whether endometrial polyps are associated with diabetes, hypertension, or obesity, independent of age and menopausal status. They did find an association between age, menopause, hypertension, obesity, and the presence of endometrial polyps. However, after multivariable logistic regression, all variables except age lost statistical significance. The median age at which polyps were present was 53 years (range: 29–86 years).

Details of the trial

A total of 394 consecutive Caucasian women underwent hysteroscopy to assess abnormal uterine bleeding, infertility, cervical polyps, or abnormal sonographic patterns (e.g., postmenopausal endometrial thickness >5 mm, endometrial hyperechogenic spots). Of these women, 353 were included in the study, and demographic characteristics and data on diabetes, hypertension, and menopausal status were collected. Anthropometric parameters were also analyzed. When a polyp was detected, it was removed via office hysteroscopy, and histologic analysis was performed.

The prevalence of endometrial polyps is associated significantly with age. Other associations, such as hypertension, obesity, and diabetes, exist simply because the prevalence of these pathologies increases with age. Therefore, age is the most significant variable to consider when assessing a patient for endometrial polyps.

Small, asymptomatic uterine polyps may regress without treatment

Lieng M, Istre O, Sandvik L, Qvigstad E. Prevalence, 1-year regression rate, and clinical significance of asymptomatic endometrial polyps: cross-sectional study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(4):465–471.

The treatment of asymptomatic polyps is controversial because their clinical consequences, malignant potential, and spontaneous regression rate are unknown. In this study, Lieng and colleagues prospectively estimated the prevalence and 1-year regression rate of incidentally diagnosed endometrial polyps in women 40 to 45 years old, as well as bleeding patterns and intensity.

They found polyps in 31 (12.1%) of 257 randomly selected women. At 1 year, the regression rate was 27%.

Details of the trial

At study inception, a standard 10-point visual analog scale was used to quantify each participant’s periodic bleeding, and a physical examination was performed. Transvaginal ultrasonography (US) and saline infusion sonography (SIS) were also performed. When a polyp was detected, researchers measured its length and used Doppler US to visualize the vessel feeding the polyp. An endometrial biopsy was also obtained.

The mean length of polyps was 14 mm (standard deviation [SD], 5.2 mm; 95% confidence interval [CI], 12.1–15.9; median, 13.4 mm; range, 6.7–28.7 mm), and the feeding vessel was identified for 22 of 31 polyps (71%). (For comparison, consider the findings of Clevenger and associates, who reported mean polyp diameters of 13.9 mm and 8.5 mm (P = .064), respectively, among women who had abnormal bleeding and women who did not.1)

When researchers compared women who had polyps with those who had none, they found no significant differences in age, body mass index, blood pressure, gynecologic symptoms, menopausal status, use of hormone therapy, or use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (Mirena). Women who had endometrial polyps scored significantly higher, however, than women who did not on the visual analog scale for periodic bleeding and on the Pictorial Blood Assessment Chart—even when women who had myomas were excluded from the analysis. Although mean hemoglobin levels were similar between groups, women who had polyps had a significantly lower mean ferritin level (25 μg/L vs 41 μg/L; P = .05).

Polyps that persisted were larger from the start

Polyps regressed spontaneously in eight women, six of whom had the feeding vessel visualized at the initial consultation. Polyps that persisted after 12 months were significantly larger (mean polyp length, 15.1 mm; SD, 5.3 mm; 95% CI, 12.7–17.5) at study inception than were those that regressed (mean polyp length, 10.7 mm; SD, 3.9 mm; 95% CI, 7.5–14.0). Polyps that persisted beyond 1 year became significantly longer during follow-up, increasing from a mean length of 15.1 mm to 18.1 mm (SD, 7.9 mm; 95% CI, 0.7–5.3; P = .01).

Twenty of the 22 women who had persistent polyps underwent transcervical resection, one underwent laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy, and one refused treatment. There were no complications.

Histology revealed that the polyps were benign in 16 women (80%), polypoid in two women (10%), and myomas in two women (10%). No atypical or malignant changes were observed in the polypectomy patients or among all participants.

A small, separate series (three patients) found all polyps to be 5 mm to 8 mm in length at detection, with a regression rate of 100% over several months.5

When an endometrial polyp 10.7 mm in length or shorter is detected incidentally in an asymptomatic, premenopausal woman, it is appropriate to follow it for regression, growth, or the development of symptoms rather than remove it immediately.

What variables signal a greater risk of malignancy?

Baiocchi G, Manci N, Pazzaglia M, et al. Malignancy in endometrial polyps: a 12-year experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(5):462.e1–e4.

Gregoriou O, Konidaris S, Vrachnis N, et al. Clinical parameters linked with malignancy in endometrial polyps. Climacteric. 2009;12(5):454–458.

Wang JH, Zhao J, Lin J. Opportunities and risk factors for premalignant and malignant transformation of endometrial polyps: management strategies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(1):53–58.

These three studies explore various aspects of a fundamental challenge: how to discriminate between polyps likely to undergo malignant transformation and those that will not.

The answer: Look for menopausal status, abnormal uterine bleeding, diabetes, obesity, and hypertension. Polyps larger than 1 cm also appear more likely to become malignant.

Details of the trials

In a retrospective study involving 1,242 women who had endometrial polyps, Baiocchi and colleagues identified 95.2% of the polyps as benign, 1.3% as premalignant, and 3.5% as malignant. Four clinical variables were significantly associated with premalignant and malignant features:

- age

- menopausal status

- abnormal uterine bleeding

- hypertension.

In their series of 516 cases, Gregoriou and associates found 96.9% of polyps to be benign, 1.2% to be premalignant, and 1.9% to be malignant. Four variables were associated with premalignant and malignant features:

- age above 60 years

- menopausal status

- obesity

- diabetes.

And in a study involving 766 patients, Wang and colleagues found 96.2% of polyps to be benign, 3.26% to involve hyperplasia with atypia, and 0.52% to be malignant. Among the variables associated with premalignant and malignant polyps were:

- polyp diameter larger than 1 cm

- menopausal status

- abnormal uterine bleeding.

When endometrial polyps are identified, the following characteristics indicate an increased risk of malignancy: age above 60 years, menopausal status, abnormal uterine bleeding, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. Polyps larger than 1 cm are also more likely to be premalignant or malignant in nature. When any of these conditions is present, polypectomy and histology are recommended.

When a patient complains of abnormal uterine bleeding, evaluation often begins with transvaginal ultrasonography (US). Among the challenges of assessing the endometrium using US is the unreliability of endometrial thickness as a predictor of pathology. For example, Breitkopf and colleagues found that transvaginal US missed intracavitary lesions in one of six premenopausal women who had abnormal bleeding and an endometrial stripe thinner than 5 mm, for a sensitivity of 74%.6

In a separate study, Marello and colleagues used the combination of hysteroscopy and directed biopsy—the gold standard of diagnosis—to evaluate 212 postmenopausal women who had an endometrial thickness of 4 mm or less.7 (This parameter has been suggested as a cutoff for symptomatic postmenopausal women.8) Of these 212 women, 10% were found to have histologically confirmed intracavitary pathology (16 polyps and 4 submucous myomas).7 Among 13 symptomatic women in this study, three (23%) were found to have an endometrial polyp.7

These studies suggest that endometrial thickness alone should not be used to exclude benign endometrial pathology in symptomatic women, be they premenopausal or postmenopausal. No data back routine US to measure endometrial thickness in asymptomatic postmenopausal women.

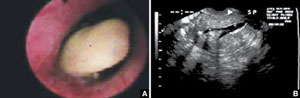

Hysteroscopy and SIS are preferred

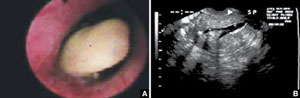

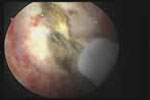

Both hysteroscopy and saline infusion sonography (SIS) have significantly better sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of intracavitary pathology than transvaginal US alone in women who have abnormal bleeding (FIGURE 1; VIDEOS 1, 2, AND 3 related to this article in the OBG Management Video Library at obgmanagement.com).1,9 Hysteroscopy and SIS detect polyps with equal accuracy.10 However, hysteroscopy allows for removal of endometrial polyps and directed biopsy at the time of diagnosis.9

FIGURE 1 Imaging of polyps: go beyond transvaginal ultrasonography for optimal visualization

A. Hysteroscopic view of an endometrial polyp. B. The view with saline-infusion sonography.

In symptomatic women, resect the polyp

Polypectomy improves abnormal bleeding, according to a systematic review by Nathani and associates.11 All studies included in the review, which involved follow-up intervals between 2 and 52 months, reported such an improvement.11

When it is performed in the office, polypectomy offers several advantages over its inpatient counterpart:

- higher cost-effectiveness

- greater convenience

- avoidance of general anesthesia.

In both settings, it can be performed using mechanical or bipolar electrosurgical instrumentation (VIDEO 4).12

Segmental resection of the polyp while it is partially attached to the uterine wall is the optimal removal technique for large polyps (FIGURE 2). A grasping forceps can then be used to remove the polyp completely (VIDEO 5). Instruments such as a basket and snare are helpful in removing the polyp effectively.13

FIGURE 2 segmental resection of a polyp

During hysteroscopic polypectomy, the polyp is resected in segments while it is still partially attached to the endometrial wall.

Is histologic analysis of a polyp sufficient risk assessment?

Rahimi S, Marani C, Renzi C, Natale ME, Giovannini P, Zeloni R. Endometrial polyps and the risk of atypical hyperplasia on biopsies of unremarkable endometrium: a study on 694 patients with benign endometrial polyps. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009;28(6):522–528.

This study involved 694 consecutive patients who had benign endometrial polyps. Investigators sought to clarify the relationship between polyps and the underlying endometrium—specifically, to determine whether a polyp is a “circumscribed pathology of the endometrium or a polypoid expression of endometrial hyperplasia.” In describing the rationale for the study, the authors observe that the association between polyps and premalignant and malignant changes remains unclear.

Participants underwent hysteroscopy for removal of the polyps, at which time two biopsies of “unremarkable” endometrium, far from the base of the polyp, were also obtained.

Overall, endometrial hyperplasia without atypia was identified on hysteroscopically unremarkable endometrium in 18% of women, and atypia was identified in 7.3%. Among postmenopausal women, hyperplasia without atypia was identified in 21.6% of cases, atypia in 12%, and adenocarcinoma in 1.2%.

Multivariable analysis revealed that postmenopausal women who had polyps heavier than 1 g were 3.6 times more likely to have atypia (95% CI, 1.3–10.3). Among premenopausal women, the likelihood of atypia increased when the polyp weighed more than 0.4 g (odds ratio [OR], 3.5; 95% CI, 1.1–10.9) or the patient was older than 40 years (OR, 3.82; 95% CI, 1.1–13.2).

Endometrial lesions are not always evident at the time of hysteroscopy. Therefore, when evaluating an endometrial lesion such as a polyp, combine hysteroscopy with histopathologic assessment of the background endometrium (by means of a pipelle or curette), especially in women who have high-risk characteristics such as menopausal status or large polyps.

They’re accessible in the OBG Management Video Library at obgmanagement.com

VIDEO 1: Saline-infusion sonographic imaging of a polyp

VIDEO 2: Hysteroscopic imaging of a polyp in a menopausal patient. A flexible 3-mm scope is used to assess an asymptomatic menopausal woman in whom an enlarged endometrial stripe was identified during earlier imaging.

VIDEO 3: Hysteroscopic imaging of a polyp and associated hyperplasia. A flexible 3-mm scope is used to evaluate a menopausal women who has uterine bleeding, revealing a 2-cm polyp.

VIDEO 4: Office polypectomy. An 8-mm, apparently benign polyp is removed from a premenopausal woman using continuous-flow operative hysteroscopy in an office setting.

VIDEO 5: Removal of a large polyp. A large (2 cm x 2.5 cm) polyp is removed in pieces, with the polyp partially attached to the endometrial wall, from a premenopausal woman who has abnormal bleeding.

More: Watch Dr. Brent Seibel perform OR-based hysteroscopic polypectomy

1. Clevenger-Hoeft M, Syrop C, Stovall D, Van Voorhis B. Sonohysterography in premenopausal women with and without abnormal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(4):516-520.

2. DeWaay DJ, Syrop CH, Nygaard IE, Davis WA, Van Voorhis BJ. Natural history of uterine polyps and leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(1):3-7.

3. Lieng M, Istre O, Sandvik L, Qvigstad E. Prevalence, 1-year regression rate, and clinical significance of asymptomatic endometrial polyps: cross-sectional study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(4):465-471.

4. Lopes RG, Baracat EC, de Albuquerque Neto LC, et al. Analysis of estrogen- and progersterone-receptor expression in endometrial polyps. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(3):300-303.

5. Haimov-Kochman R, Deri-Hasid R, Hamani Y, Voss E. The natural course of endometrial polyps: could they vanish when left untreated? Fertil Steril. 2009;92(2):828.e11-e12.

6. Breitkopf DM, Frederickson RA, Snyder RR. Detection of benign endometrial masses by endometrial stripe measurement in premenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(1):120-125.

7. Marello F, Bettocchi S, Greco P, et al. Hysteroscopic evaluation of menopausal patients with sonographically atrophic endometrium. J Am Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(2):197-200.

8. Karlsson B, Granberg S, Wikland M, Ylostalo P, Torvid K, Marsal K, Valentin L.

Transvaginal ultrasonography of the endometrium in women with postmenopausal bleeding—a Nordic multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(5):1488-1494.

9. Paschopoulos M, Lolis E, Alamanos Y, Koliopoulos G, Paraskevaidis E. Vaginoscopic hysteroscopy and transvaginal sonography in the evaluation of patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(4):506-510.

10. Jansen FW, de Kroon CD, van Dongen H, Grooters C, Louwé L, Trimbos-Kemper T. Diagnostic hysteroscopy and saline infusion sonography: prediction of intrauterine polyps and myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(4):320-324.

11. Nathani F, Clark TJ. Uterine polypectomy in the management of abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(4):260-268.

12. Garuti G, Centinaio G, Luerti M. Outpatient hysteroscopic polypectomy in postmenopausal women: a comparison between mechanical and electrosurgical resection. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(5):595-600.

13. Timmermans A, Veersema S. Ambulatory transcervical resection of polyps with the Duckbill polyp snare: a modality for treatment of endometrial polyps. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(1):37-39.

Endometrial polyps are a relatively common pathology, occurring in 24% to 41% of women who have abnormal bleeding, and in about 10% of asymptomatic women.1,2 Endometrial polyps may be associated with leiomyomas in women who have abnormal bleeding.1-3