User login

Hysterectomy in patients with history of prior cesarean delivery: A reverse dissection technique for vesicouterine adhesions

Minimally invasive surgical techniques, which have revolutionized modern-day surgery, are the current standard of care for benign hysterectomies.1-4 Many surgeons use a video-laparoscopic approach, with or without robotic assistance, to perform a hysterectomy. The development of a bladder flap or vesicovaginal surgical space is a critical step for mobilizing the bladder. When properly performed, it allows for appropriate closure of the vaginal cuff while mitigating the risk of urinary bladder damage.

In patients with no prior pelvic surgeries, this vesicovaginal anatomic space is typically developed with ease. However, in patients who have had prior cesarean deliveries (CDs), the presence of vesicouterine adhesions could make this step significantly more challenging. As a result, the risk of bladder injury is higher.5-8

With the current tide of cesarean birth rates approaching 33% on a national scale, the presence of vesicouterine adhesions is commonly encountered.9 These adhesions can distort the anatomy and thereby create more difficult dissections and increase operative time, conversion to laparotomy, and inadvertent cystotomy. Such a challenge also presents an increased risk of injuring adjacent structures.

In this article, we describe an effective method of dissection that is especially useful in the setting of prior CDs. This method involves developing a "new" surgical space lateral and caudal to the vesicocervical space.

Steps in operative planning

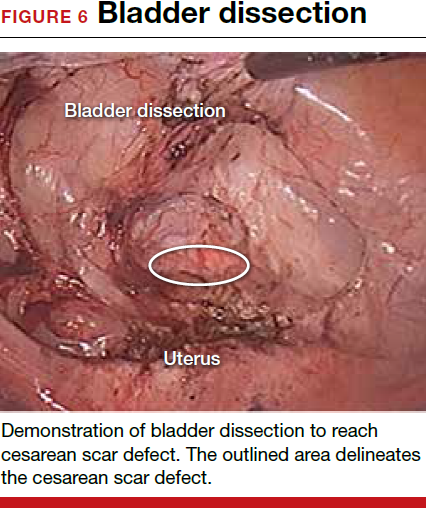

Preoperative evaluation. A thorough preoperative evaluation should be performed for patients planning to undergo a laparoscopic hysterectomy. This includes obtaining details of their medical and surgical history. Access to prior surgical records may help to facilitate planning of the surgical approach. Previous pelvic surgery, such as CD, anterior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect repair, endometriosis treatment, or exploratory laparotomy, may predispose these patients to develop adhesions in the anterior cul-de-sac. Our method of reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be particularly efficacious in these settings.

Surgical preparation and laparoscopic port placement. In the operative suite, the patient is placed under general anesthesia and positioned in the dorsal lithotomy position.10 Sterile prep and drapes are used in the standard fashion. A urinary catheter is inserted to maintain a decompressed bladder. A uterine manipulator is inserted with good placement ensured.

Per our practice, we introduce laparoscopic ports in 4 locations. The first incision is made in the umbilicus for the introduction of a 10-mm laparoscope. Three subsequent 5-mm incisions are made in the left and right lower lateral quadrants and medially at the level of the suprapubic region.10 Upon laparoscopic entry, we perform a comprehensive survey of the abdominopelvic cavity. Adequate mobility of the uterus is confirmed.11 Any posterior uterine adhesions or endometriosis are treated appropriately.12

First step in the surgical technique: Lateral dissection

We proceed by first desiccating and cutting the round ligament laterally near the inguinal canal. This technique is carried forward in a caudal direction as the areolar tissue near the obliterated umbilical artery is expanded by the pneumoperitoneum. With a vessel sealing-cutting device, we address the attachments to the adnexa. If the ovaries are to be retained, the utero-ovarian ligament is dessicated and cut. If an oophorectomy is indicated, the infundibulopelvic ligament is dessicated and cut.

Continue to: Using the tip of the vessel sealing...

Using the tip of the vessel sealing-cutting device, the space between the anterior and posterior leaves of the broad ligament is developed and opened. A grasping forceps is then used to elevate the anterior leaf of the broad ligament and maintain medial traction. A space parallel and lateral to the cervix and bladder is then created with blunt dissection.

The inferior and medial direction of this dissection is paramount to avoid injury to nearby structures in the pelvic sidewall. Gradually, this will lead to the identification of the vesciovaginal ligament and then the vesicocervical ligament. The development of these spaces allows for the lateral and inferior displacement of the ureter. These maneuvers can mitigate ureter injury by pushing it away from the planes of dissection during the hysterectomy.

Continued traction is maintained by keeping the medial aspect of the anterior leaf of the broad ligament intact. However, the posterior leaf is dissected next, which further lateralizes the ureter. Now, with the uterine vessels fully exposed, they are thoroughly dessicated and ligated. The same procedure is then performed on the contralateral side.11 (See the box below for links to videos that demonstrate the techniques described here.)

Creating the “new” space

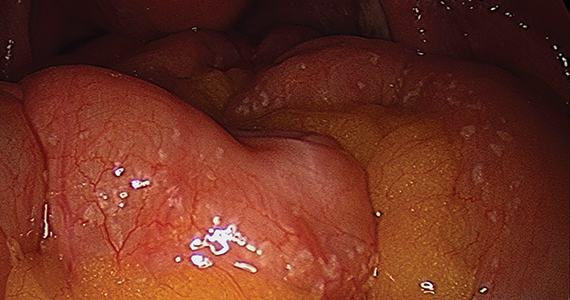

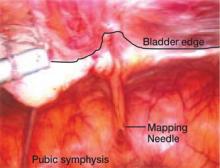

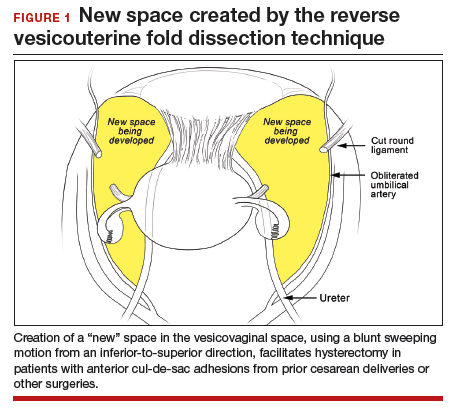

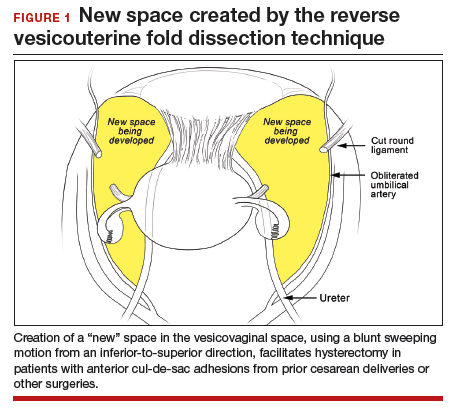

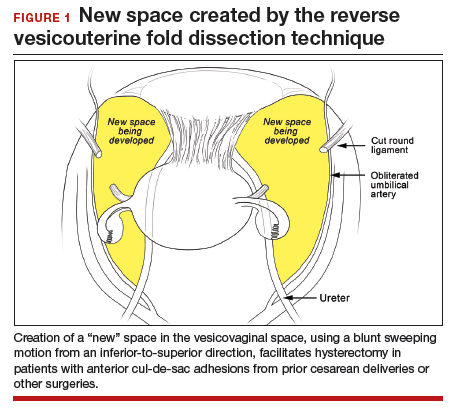

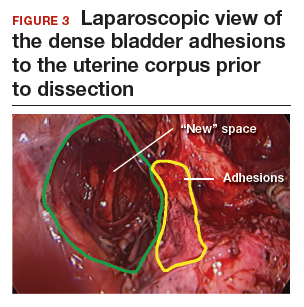

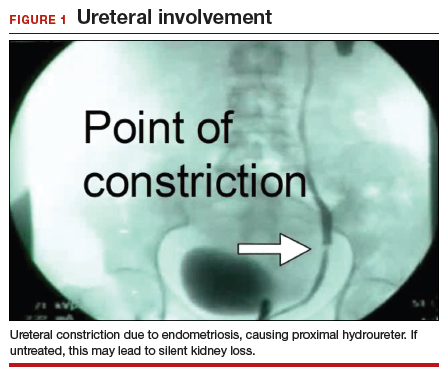

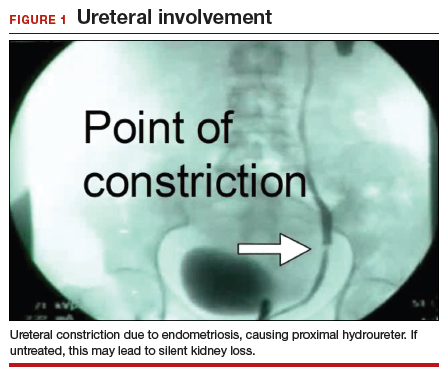

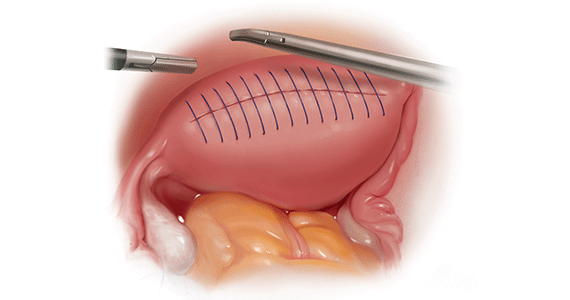

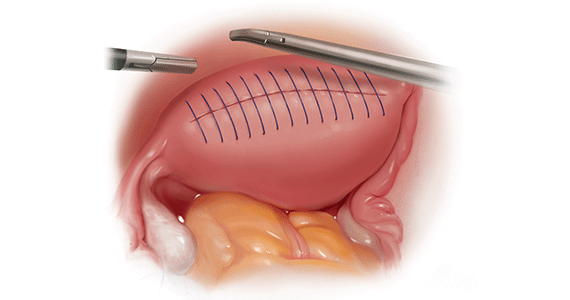

In the “new” space that was partially developed during the lateral dissection, blunt dissection is continued, using a sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, to extend this avascular space. This is performed bilaterally until both sides are connected from the inferior aspect of the vesicouterine adhesions, if present. This thorough dissection creates what we refer to as a “new” space11 (FIGURE 1).

Medially, the new space is bordered by the vesicocervical-vaginal ligament, also known as the bladder pillar. Its distal landmark is the bladder. The remaining intact anterior leaf of the broad ligament lies adjacent to the space anteriorly. The inner aspect of the obliterated umbilical artery neighbors it laterally. Lastly, the vesicovaginal plane’s posterior margin is the parametrium, which is the region where the ureter courses into the bladder. The paravesical space lies lateral to the obliterated umbilical ligament.

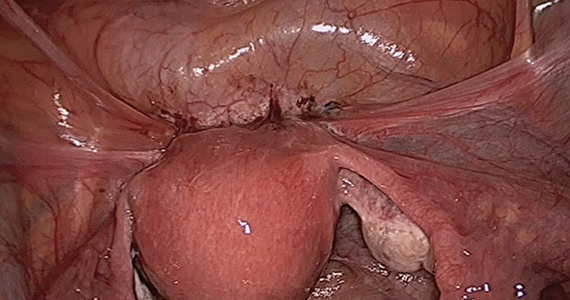

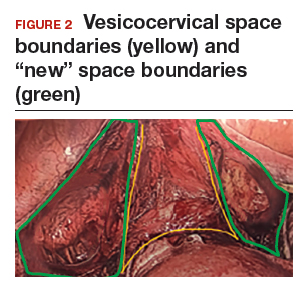

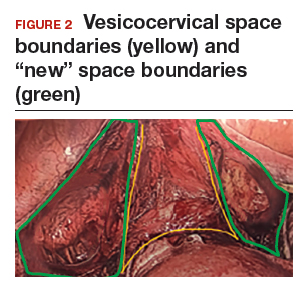

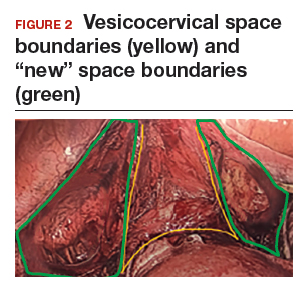

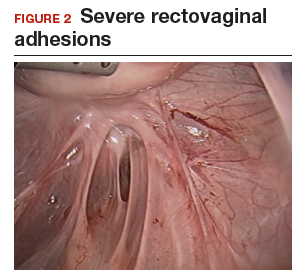

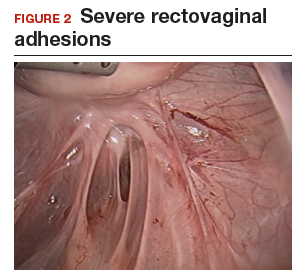

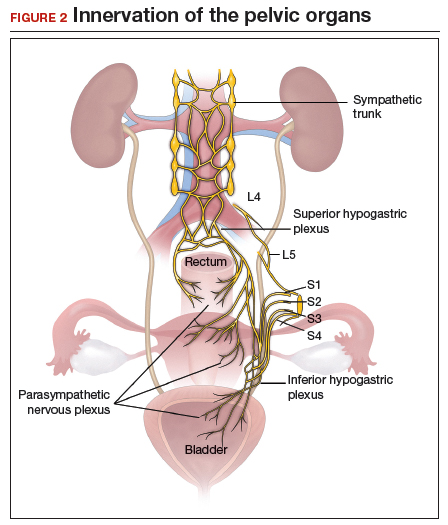

Visualization of this new space is made possible in the laparoscopic setting. The pneumoperitoneum allows for better demarcation of the space. Additionally, laparoscopic views of the anatomic spaces differ from those of the laparotomy view because of the magnification and the insufflation of carbon dioxide gas in the spaces.13,14 In our experience, approaching the surgery from the “new” space could significantly decrease the risk of genitourinary injuries in patients with anterior cul-de-sac adhesions (FIGURE 2).

Using the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique

Among patients with prior CDs, adhesions often are at the level of or superior to the prior CD scar. By creating the new space, safe dissection from a previously untouched area can be accomplished and injury to the urinary bladder can be avoided.

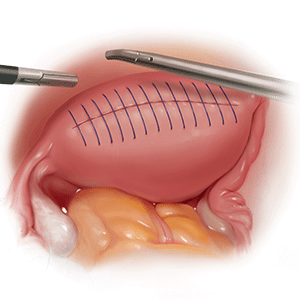

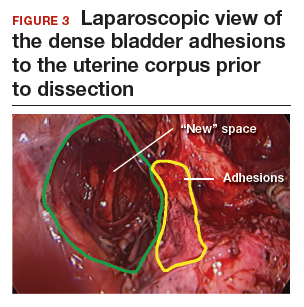

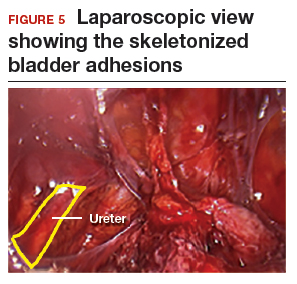

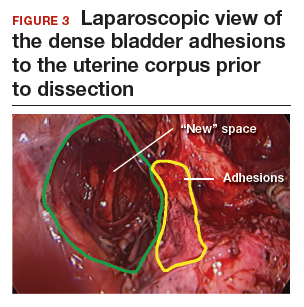

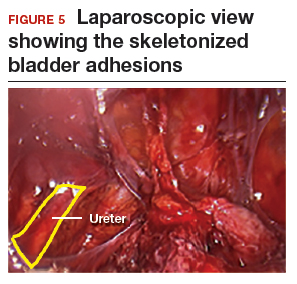

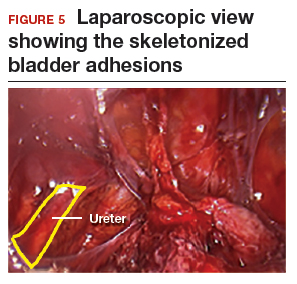

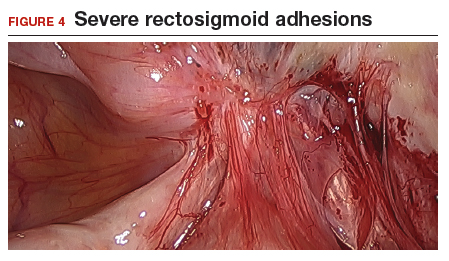

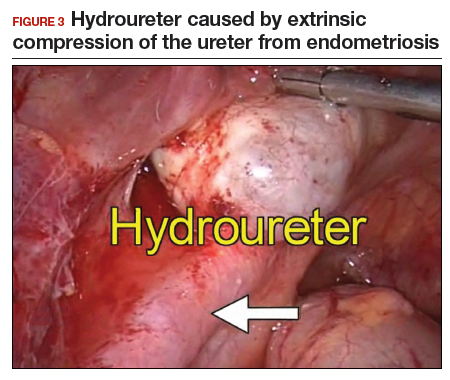

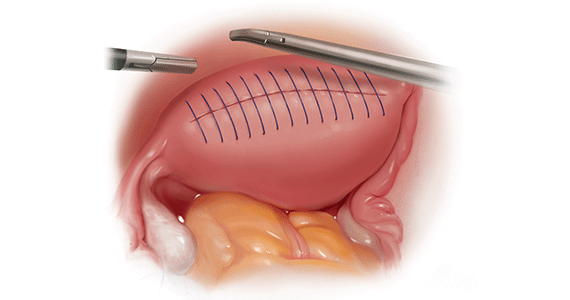

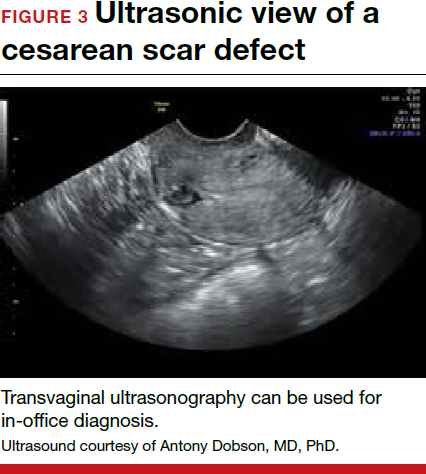

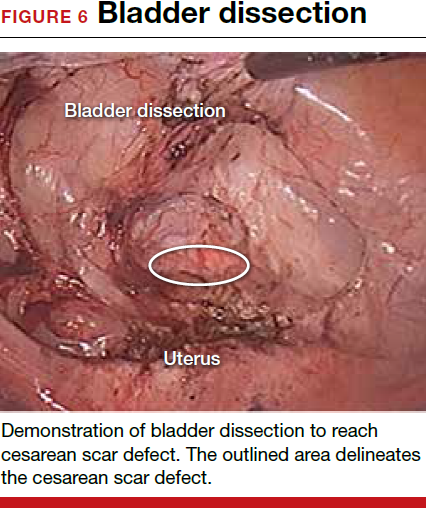

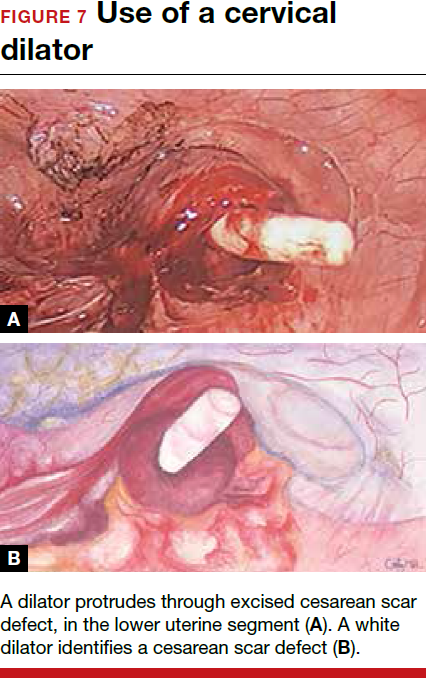

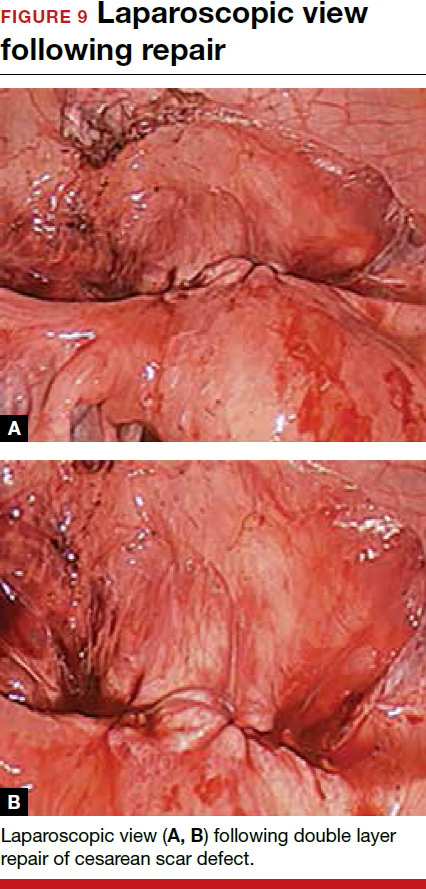

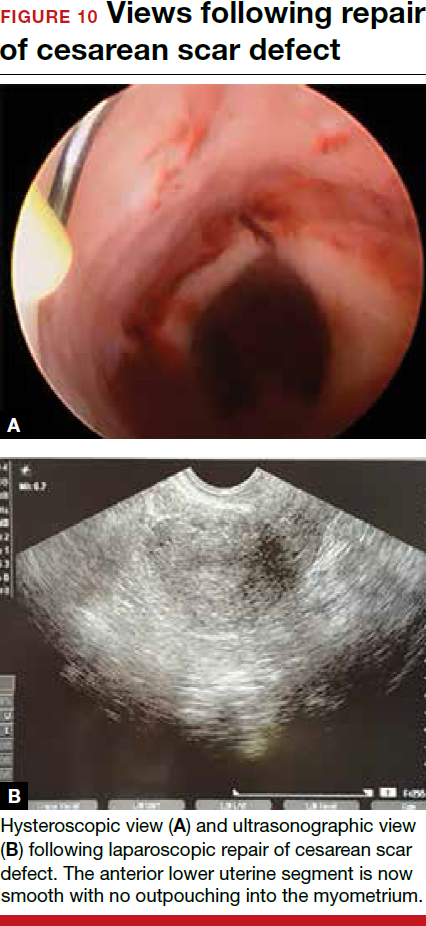

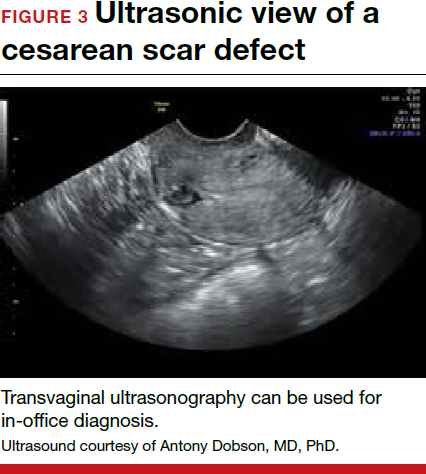

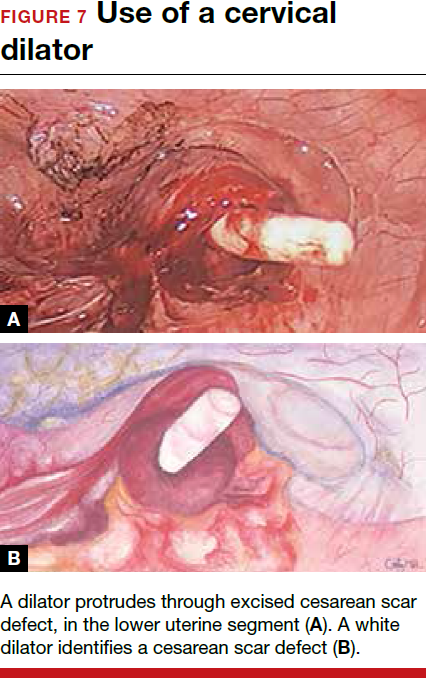

The reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be performed from this space. Using the previously described blunt sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, the vesicovaginal and vesicocervical space is further developed from an unscarred plane. This will separate the lowest portion of the bladder from the vagina, cervix, and uterus in a safe manner. Similar to the technique performed during a vaginal hysterectomy, this reverse motion of developing the bladder flap avoids erroneous and blind dissection through the vesicouterine adhesions (FIGURES 3–5).

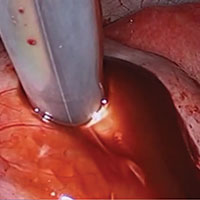

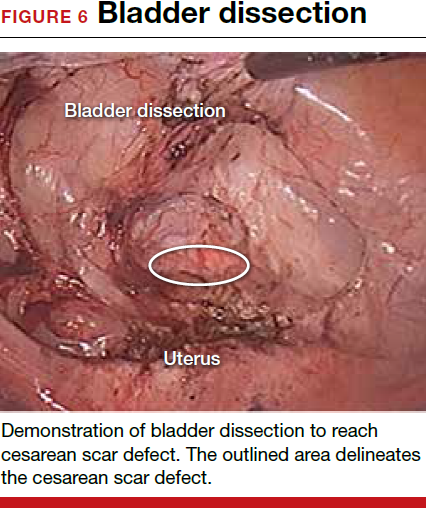

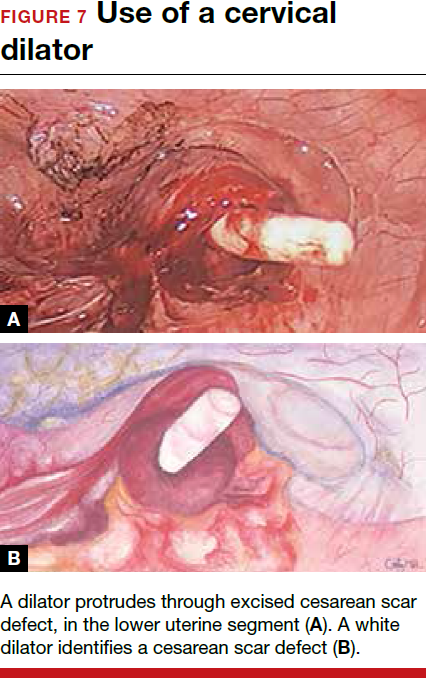

Once the bladder adhesions are well delineated and separated from the uterus by the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique, it is safe to proceed with complete bladder mobilization. Sharp dissection can be used to dissect the remaining scarred bladder at its most superior attachments. Avoid the use of thermal energy to prevent heat injury to the bladder. Carefully dissect the bladder adhesions from the cervicouterine junction. Additional inferior bladder mobilization should be performed up to 3 cm past the leading edge of the cervicovaginal junction to ensure sufficient vaginal tissue for cuff closure. Note that the bladder pillars occasionally may be trapped inside a CD scar. This surgical technique could make it easier to release the pillars from inside the adhesions and penetrating into the scar.15

Continue to: Completing the surgery...

Completing the surgery

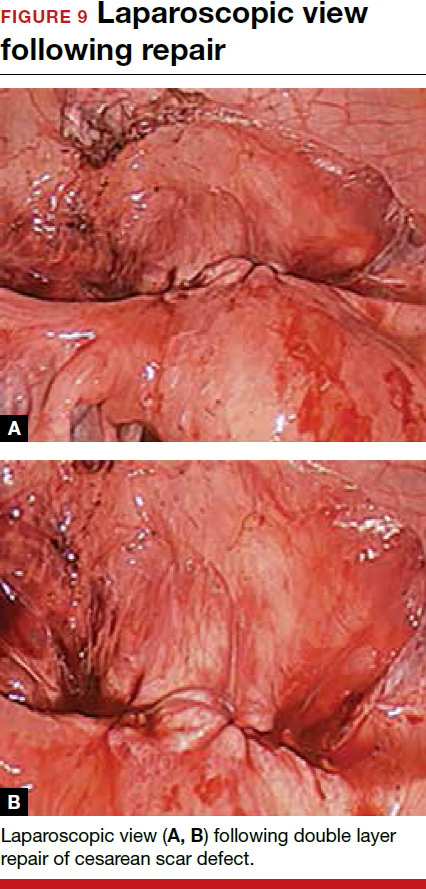

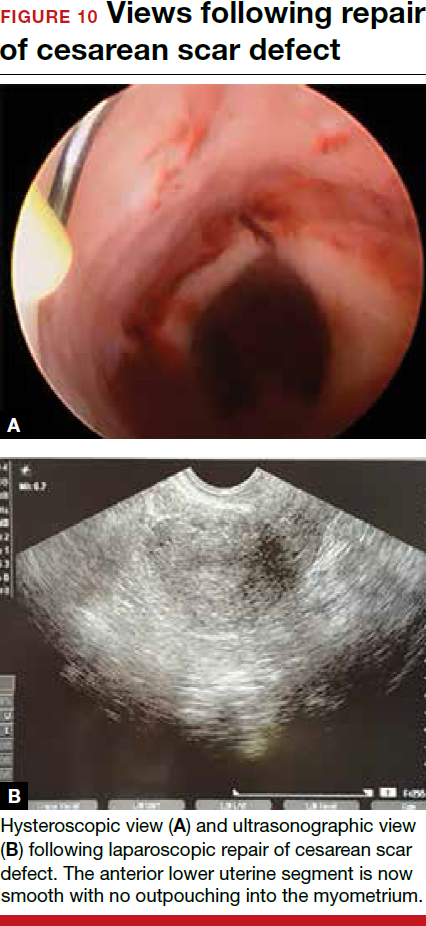

Once the bladder is freely mobilized and all adhesions have been dissected, the cervix is circumferentially amputated using monopolar cautery. The vaginal cuff can then be closed from either a laparoscopic or vaginal approach using polyglactin 910 (0-Vicryl) or barbed (V-Loc) suture in a running or interrupted fashion. Our practice uses a 1.5-cm margin depth with each suture. At the end of the surgery, routine cystoscopy is performed to verify distal ureteral patency.16 Postoperatively, we manage these patients using a fast-track, or enhanced recovery, model.17

From the Center for Special Minimally Invasive and Robotic Surgery

https://youtu.be/wgGssnd1JAo

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Case 1: TLH with development of the "new space": The technique with prior C-section

- Case 2: A straightforward case: Dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia

- Case 3: History of multiple C-sections with adhesions and fibroids

https://youtu.be/6vHamfPZhdY

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy after prior cesarean delivery

An effective technique in challenging situations

Genitourinary injury is a common complication of hysterectomy.18 The proximity of the bladder and ureters to the field of dissection during a hysterectomy can be especially challenging when the anatomy is distorted by adhesion formation from prior surgeries. One study demonstrated a 1.3% incidence of urinary tract injuries during laparoscopic hysterectomy.6 This included 0.54% ureteral injuries, 0.71% urinary bladder injuries, and 0.06% combined bladder and ureteral injuries.6 Particularly among patients with a prior CD, the risk of bladder injury can be significantly heightened.18

The reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique that we described offers multiple benefits. By starting the procedure from an untouched and avascular plane, dissection into the plane of the prior adhesions can be circumvented; thus, bleeding is limited and injury to the bladder and ureters is avoided or minimized. By using blunt and sharp dissection, thermal injury and delayed necrosis can be mitigated. Finally, with bladder mobilization well below the colpotomy site, more adequate vaginal tissue is free to be incorporated into the vaginal cuff closure, thereby limiting the risk of cuff dehiscence.16

While we have found this technique effective for patients with prior cesarean deliveries, it also may be applied to any patient who has a scarred anterior cul-de-sac. This could include patients with prior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect, or endometriosis. Despite the technique being a safeguard against bladder injury, surgeons must still use care in developing the spaces to avoid ureteral injury, especially in a setting of distorted anatomy.

- Page B. Nezhat & the advent of advanced operative video-laparoscopy. In: Nezhat C. Nezhat's History of Endoscopy. Tuttlingen, Germany: Endo Press; 2011:159-179. https://laparoscopy.blogs.com/endoscopyhistory/chapter_22. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Podratz KC. Degrees of freedom: advances in gynecological and obstetric surgery. In: American College of Surgeons. Remembering Milestones and Achievements in Surgery: Inspiring Quality for a Hundred Years, 1913-2012. Tampa, FL: Faircount Media Group; 2013:113-119. http://endometriosisspecialists.com/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/Degrees-of-Freedom-Advances-in-Gynecological-and-Obstetrical-Surgery.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2019.

- Kelley WE Jr. The evolution of laparoscopy and the revolution in surgery in the decade of the 1990s. JSLS. 2008;12:351-357.

- Tokunaga T. Video surgery expands its scope. Stanford Med. 1993/1994;11(2)12-16.

- Rooney CM, Crawford AT, Vassallo BJ, et al. Is previous cesarean section a risk for incidental cystotomy at the time of hysterectomy? A case-controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2041-2044.

- Tan-Kim J, Menefee SA, Reinsch CS, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy and urinary tract injury: experience in a health maintenance organization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1278-1286.

- Sinha R, Sundaram M, Lakhotia S, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy in women with previous cesarean sections. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:513-517.

- O'Hanlan KA. Cystosufflation to prevent bladder injury. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:195-197.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64:1-65.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy with DVD, 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Nezhat C, Grace LA, Razavi GM, et al. Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for laparoscopic hysterectomy after prior cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:629-633.

- Nezhat C, Xie J, Aldape D, et al. Use of laparoscopic modified nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for the treatment of extensive endometriosis. Cureus. 2014;6:e159.

- Yabuki Y, Sasaki H, Hatakeyama N, et al. Discrepancies between classic anatomy and modern gynecologic surgery on pelvic connective tissue structure: harmonization of those concepts by collaborative cadaver dissection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:7-15.

- Uhlenhuth E. Problems in the Anatomy of the Pelvis: An Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Co; 1953.

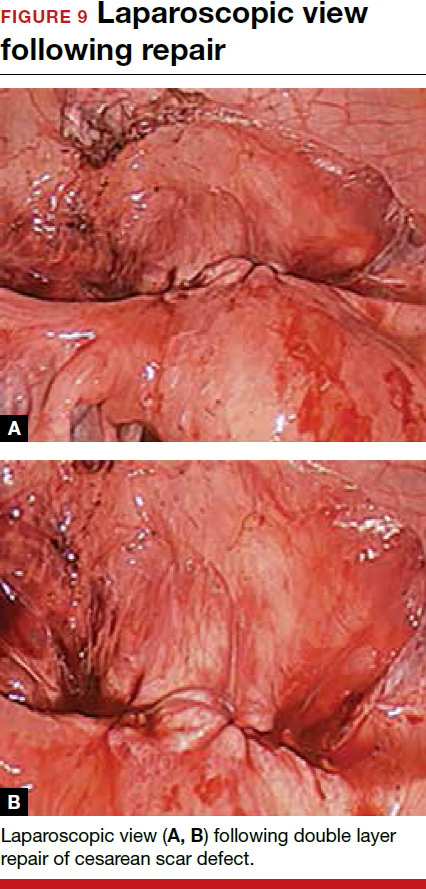

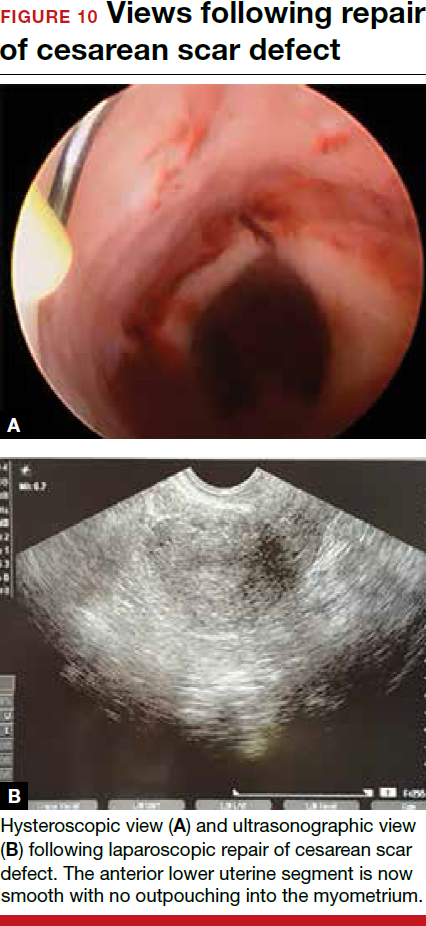

- Nezhat C, Grace, L, Soliemannjad, et al. Cesarean scar defect: what is it and how should it be treated? OBG Manag. 2016;28(4):32,34,36,38-39,53.

- Nezhat C, Kennedy Burns M, Wood M, et al. Vaginal cuff dehiscence and evisceration: a review. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:972-985.

- Nezhat C, Main J, Paka C, et al. Advanced gynecologic laparoscopy in a fast-track ambulatory surgery center. JSLS. 2014;18:pii:e2014.00291.

- Nezhat C, Falik R, McKinney S, et al. Pathophysiology and management of urinary tract endometriosis. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:359-372.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques, which have revolutionized modern-day surgery, are the current standard of care for benign hysterectomies.1-4 Many surgeons use a video-laparoscopic approach, with or without robotic assistance, to perform a hysterectomy. The development of a bladder flap or vesicovaginal surgical space is a critical step for mobilizing the bladder. When properly performed, it allows for appropriate closure of the vaginal cuff while mitigating the risk of urinary bladder damage.

In patients with no prior pelvic surgeries, this vesicovaginal anatomic space is typically developed with ease. However, in patients who have had prior cesarean deliveries (CDs), the presence of vesicouterine adhesions could make this step significantly more challenging. As a result, the risk of bladder injury is higher.5-8

With the current tide of cesarean birth rates approaching 33% on a national scale, the presence of vesicouterine adhesions is commonly encountered.9 These adhesions can distort the anatomy and thereby create more difficult dissections and increase operative time, conversion to laparotomy, and inadvertent cystotomy. Such a challenge also presents an increased risk of injuring adjacent structures.

In this article, we describe an effective method of dissection that is especially useful in the setting of prior CDs. This method involves developing a "new" surgical space lateral and caudal to the vesicocervical space.

Steps in operative planning

Preoperative evaluation. A thorough preoperative evaluation should be performed for patients planning to undergo a laparoscopic hysterectomy. This includes obtaining details of their medical and surgical history. Access to prior surgical records may help to facilitate planning of the surgical approach. Previous pelvic surgery, such as CD, anterior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect repair, endometriosis treatment, or exploratory laparotomy, may predispose these patients to develop adhesions in the anterior cul-de-sac. Our method of reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be particularly efficacious in these settings.

Surgical preparation and laparoscopic port placement. In the operative suite, the patient is placed under general anesthesia and positioned in the dorsal lithotomy position.10 Sterile prep and drapes are used in the standard fashion. A urinary catheter is inserted to maintain a decompressed bladder. A uterine manipulator is inserted with good placement ensured.

Per our practice, we introduce laparoscopic ports in 4 locations. The first incision is made in the umbilicus for the introduction of a 10-mm laparoscope. Three subsequent 5-mm incisions are made in the left and right lower lateral quadrants and medially at the level of the suprapubic region.10 Upon laparoscopic entry, we perform a comprehensive survey of the abdominopelvic cavity. Adequate mobility of the uterus is confirmed.11 Any posterior uterine adhesions or endometriosis are treated appropriately.12

First step in the surgical technique: Lateral dissection

We proceed by first desiccating and cutting the round ligament laterally near the inguinal canal. This technique is carried forward in a caudal direction as the areolar tissue near the obliterated umbilical artery is expanded by the pneumoperitoneum. With a vessel sealing-cutting device, we address the attachments to the adnexa. If the ovaries are to be retained, the utero-ovarian ligament is dessicated and cut. If an oophorectomy is indicated, the infundibulopelvic ligament is dessicated and cut.

Continue to: Using the tip of the vessel sealing...

Using the tip of the vessel sealing-cutting device, the space between the anterior and posterior leaves of the broad ligament is developed and opened. A grasping forceps is then used to elevate the anterior leaf of the broad ligament and maintain medial traction. A space parallel and lateral to the cervix and bladder is then created with blunt dissection.

The inferior and medial direction of this dissection is paramount to avoid injury to nearby structures in the pelvic sidewall. Gradually, this will lead to the identification of the vesciovaginal ligament and then the vesicocervical ligament. The development of these spaces allows for the lateral and inferior displacement of the ureter. These maneuvers can mitigate ureter injury by pushing it away from the planes of dissection during the hysterectomy.

Continued traction is maintained by keeping the medial aspect of the anterior leaf of the broad ligament intact. However, the posterior leaf is dissected next, which further lateralizes the ureter. Now, with the uterine vessels fully exposed, they are thoroughly dessicated and ligated. The same procedure is then performed on the contralateral side.11 (See the box below for links to videos that demonstrate the techniques described here.)

Creating the “new” space

In the “new” space that was partially developed during the lateral dissection, blunt dissection is continued, using a sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, to extend this avascular space. This is performed bilaterally until both sides are connected from the inferior aspect of the vesicouterine adhesions, if present. This thorough dissection creates what we refer to as a “new” space11 (FIGURE 1).

Medially, the new space is bordered by the vesicocervical-vaginal ligament, also known as the bladder pillar. Its distal landmark is the bladder. The remaining intact anterior leaf of the broad ligament lies adjacent to the space anteriorly. The inner aspect of the obliterated umbilical artery neighbors it laterally. Lastly, the vesicovaginal plane’s posterior margin is the parametrium, which is the region where the ureter courses into the bladder. The paravesical space lies lateral to the obliterated umbilical ligament.

Visualization of this new space is made possible in the laparoscopic setting. The pneumoperitoneum allows for better demarcation of the space. Additionally, laparoscopic views of the anatomic spaces differ from those of the laparotomy view because of the magnification and the insufflation of carbon dioxide gas in the spaces.13,14 In our experience, approaching the surgery from the “new” space could significantly decrease the risk of genitourinary injuries in patients with anterior cul-de-sac adhesions (FIGURE 2).

Using the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique

Among patients with prior CDs, adhesions often are at the level of or superior to the prior CD scar. By creating the new space, safe dissection from a previously untouched area can be accomplished and injury to the urinary bladder can be avoided.

The reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be performed from this space. Using the previously described blunt sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, the vesicovaginal and vesicocervical space is further developed from an unscarred plane. This will separate the lowest portion of the bladder from the vagina, cervix, and uterus in a safe manner. Similar to the technique performed during a vaginal hysterectomy, this reverse motion of developing the bladder flap avoids erroneous and blind dissection through the vesicouterine adhesions (FIGURES 3–5).

Once the bladder adhesions are well delineated and separated from the uterus by the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique, it is safe to proceed with complete bladder mobilization. Sharp dissection can be used to dissect the remaining scarred bladder at its most superior attachments. Avoid the use of thermal energy to prevent heat injury to the bladder. Carefully dissect the bladder adhesions from the cervicouterine junction. Additional inferior bladder mobilization should be performed up to 3 cm past the leading edge of the cervicovaginal junction to ensure sufficient vaginal tissue for cuff closure. Note that the bladder pillars occasionally may be trapped inside a CD scar. This surgical technique could make it easier to release the pillars from inside the adhesions and penetrating into the scar.15

Continue to: Completing the surgery...

Completing the surgery

Once the bladder is freely mobilized and all adhesions have been dissected, the cervix is circumferentially amputated using monopolar cautery. The vaginal cuff can then be closed from either a laparoscopic or vaginal approach using polyglactin 910 (0-Vicryl) or barbed (V-Loc) suture in a running or interrupted fashion. Our practice uses a 1.5-cm margin depth with each suture. At the end of the surgery, routine cystoscopy is performed to verify distal ureteral patency.16 Postoperatively, we manage these patients using a fast-track, or enhanced recovery, model.17

From the Center for Special Minimally Invasive and Robotic Surgery

https://youtu.be/wgGssnd1JAo

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Case 1: TLH with development of the "new space": The technique with prior C-section

- Case 2: A straightforward case: Dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia

- Case 3: History of multiple C-sections with adhesions and fibroids

https://youtu.be/6vHamfPZhdY

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy after prior cesarean delivery

An effective technique in challenging situations

Genitourinary injury is a common complication of hysterectomy.18 The proximity of the bladder and ureters to the field of dissection during a hysterectomy can be especially challenging when the anatomy is distorted by adhesion formation from prior surgeries. One study demonstrated a 1.3% incidence of urinary tract injuries during laparoscopic hysterectomy.6 This included 0.54% ureteral injuries, 0.71% urinary bladder injuries, and 0.06% combined bladder and ureteral injuries.6 Particularly among patients with a prior CD, the risk of bladder injury can be significantly heightened.18

The reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique that we described offers multiple benefits. By starting the procedure from an untouched and avascular plane, dissection into the plane of the prior adhesions can be circumvented; thus, bleeding is limited and injury to the bladder and ureters is avoided or minimized. By using blunt and sharp dissection, thermal injury and delayed necrosis can be mitigated. Finally, with bladder mobilization well below the colpotomy site, more adequate vaginal tissue is free to be incorporated into the vaginal cuff closure, thereby limiting the risk of cuff dehiscence.16

While we have found this technique effective for patients with prior cesarean deliveries, it also may be applied to any patient who has a scarred anterior cul-de-sac. This could include patients with prior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect, or endometriosis. Despite the technique being a safeguard against bladder injury, surgeons must still use care in developing the spaces to avoid ureteral injury, especially in a setting of distorted anatomy.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques, which have revolutionized modern-day surgery, are the current standard of care for benign hysterectomies.1-4 Many surgeons use a video-laparoscopic approach, with or without robotic assistance, to perform a hysterectomy. The development of a bladder flap or vesicovaginal surgical space is a critical step for mobilizing the bladder. When properly performed, it allows for appropriate closure of the vaginal cuff while mitigating the risk of urinary bladder damage.

In patients with no prior pelvic surgeries, this vesicovaginal anatomic space is typically developed with ease. However, in patients who have had prior cesarean deliveries (CDs), the presence of vesicouterine adhesions could make this step significantly more challenging. As a result, the risk of bladder injury is higher.5-8

With the current tide of cesarean birth rates approaching 33% on a national scale, the presence of vesicouterine adhesions is commonly encountered.9 These adhesions can distort the anatomy and thereby create more difficult dissections and increase operative time, conversion to laparotomy, and inadvertent cystotomy. Such a challenge also presents an increased risk of injuring adjacent structures.

In this article, we describe an effective method of dissection that is especially useful in the setting of prior CDs. This method involves developing a "new" surgical space lateral and caudal to the vesicocervical space.

Steps in operative planning

Preoperative evaluation. A thorough preoperative evaluation should be performed for patients planning to undergo a laparoscopic hysterectomy. This includes obtaining details of their medical and surgical history. Access to prior surgical records may help to facilitate planning of the surgical approach. Previous pelvic surgery, such as CD, anterior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect repair, endometriosis treatment, or exploratory laparotomy, may predispose these patients to develop adhesions in the anterior cul-de-sac. Our method of reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be particularly efficacious in these settings.

Surgical preparation and laparoscopic port placement. In the operative suite, the patient is placed under general anesthesia and positioned in the dorsal lithotomy position.10 Sterile prep and drapes are used in the standard fashion. A urinary catheter is inserted to maintain a decompressed bladder. A uterine manipulator is inserted with good placement ensured.

Per our practice, we introduce laparoscopic ports in 4 locations. The first incision is made in the umbilicus for the introduction of a 10-mm laparoscope. Three subsequent 5-mm incisions are made in the left and right lower lateral quadrants and medially at the level of the suprapubic region.10 Upon laparoscopic entry, we perform a comprehensive survey of the abdominopelvic cavity. Adequate mobility of the uterus is confirmed.11 Any posterior uterine adhesions or endometriosis are treated appropriately.12

First step in the surgical technique: Lateral dissection

We proceed by first desiccating and cutting the round ligament laterally near the inguinal canal. This technique is carried forward in a caudal direction as the areolar tissue near the obliterated umbilical artery is expanded by the pneumoperitoneum. With a vessel sealing-cutting device, we address the attachments to the adnexa. If the ovaries are to be retained, the utero-ovarian ligament is dessicated and cut. If an oophorectomy is indicated, the infundibulopelvic ligament is dessicated and cut.

Continue to: Using the tip of the vessel sealing...

Using the tip of the vessel sealing-cutting device, the space between the anterior and posterior leaves of the broad ligament is developed and opened. A grasping forceps is then used to elevate the anterior leaf of the broad ligament and maintain medial traction. A space parallel and lateral to the cervix and bladder is then created with blunt dissection.

The inferior and medial direction of this dissection is paramount to avoid injury to nearby structures in the pelvic sidewall. Gradually, this will lead to the identification of the vesciovaginal ligament and then the vesicocervical ligament. The development of these spaces allows for the lateral and inferior displacement of the ureter. These maneuvers can mitigate ureter injury by pushing it away from the planes of dissection during the hysterectomy.

Continued traction is maintained by keeping the medial aspect of the anterior leaf of the broad ligament intact. However, the posterior leaf is dissected next, which further lateralizes the ureter. Now, with the uterine vessels fully exposed, they are thoroughly dessicated and ligated. The same procedure is then performed on the contralateral side.11 (See the box below for links to videos that demonstrate the techniques described here.)

Creating the “new” space

In the “new” space that was partially developed during the lateral dissection, blunt dissection is continued, using a sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, to extend this avascular space. This is performed bilaterally until both sides are connected from the inferior aspect of the vesicouterine adhesions, if present. This thorough dissection creates what we refer to as a “new” space11 (FIGURE 1).

Medially, the new space is bordered by the vesicocervical-vaginal ligament, also known as the bladder pillar. Its distal landmark is the bladder. The remaining intact anterior leaf of the broad ligament lies adjacent to the space anteriorly. The inner aspect of the obliterated umbilical artery neighbors it laterally. Lastly, the vesicovaginal plane’s posterior margin is the parametrium, which is the region where the ureter courses into the bladder. The paravesical space lies lateral to the obliterated umbilical ligament.

Visualization of this new space is made possible in the laparoscopic setting. The pneumoperitoneum allows for better demarcation of the space. Additionally, laparoscopic views of the anatomic spaces differ from those of the laparotomy view because of the magnification and the insufflation of carbon dioxide gas in the spaces.13,14 In our experience, approaching the surgery from the “new” space could significantly decrease the risk of genitourinary injuries in patients with anterior cul-de-sac adhesions (FIGURE 2).

Using the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique

Among patients with prior CDs, adhesions often are at the level of or superior to the prior CD scar. By creating the new space, safe dissection from a previously untouched area can be accomplished and injury to the urinary bladder can be avoided.

The reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be performed from this space. Using the previously described blunt sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, the vesicovaginal and vesicocervical space is further developed from an unscarred plane. This will separate the lowest portion of the bladder from the vagina, cervix, and uterus in a safe manner. Similar to the technique performed during a vaginal hysterectomy, this reverse motion of developing the bladder flap avoids erroneous and blind dissection through the vesicouterine adhesions (FIGURES 3–5).

Once the bladder adhesions are well delineated and separated from the uterus by the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique, it is safe to proceed with complete bladder mobilization. Sharp dissection can be used to dissect the remaining scarred bladder at its most superior attachments. Avoid the use of thermal energy to prevent heat injury to the bladder. Carefully dissect the bladder adhesions from the cervicouterine junction. Additional inferior bladder mobilization should be performed up to 3 cm past the leading edge of the cervicovaginal junction to ensure sufficient vaginal tissue for cuff closure. Note that the bladder pillars occasionally may be trapped inside a CD scar. This surgical technique could make it easier to release the pillars from inside the adhesions and penetrating into the scar.15

Continue to: Completing the surgery...

Completing the surgery

Once the bladder is freely mobilized and all adhesions have been dissected, the cervix is circumferentially amputated using monopolar cautery. The vaginal cuff can then be closed from either a laparoscopic or vaginal approach using polyglactin 910 (0-Vicryl) or barbed (V-Loc) suture in a running or interrupted fashion. Our practice uses a 1.5-cm margin depth with each suture. At the end of the surgery, routine cystoscopy is performed to verify distal ureteral patency.16 Postoperatively, we manage these patients using a fast-track, or enhanced recovery, model.17

From the Center for Special Minimally Invasive and Robotic Surgery

https://youtu.be/wgGssnd1JAo

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Case 1: TLH with development of the "new space": The technique with prior C-section

- Case 2: A straightforward case: Dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia

- Case 3: History of multiple C-sections with adhesions and fibroids

https://youtu.be/6vHamfPZhdY

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy after prior cesarean delivery

An effective technique in challenging situations

Genitourinary injury is a common complication of hysterectomy.18 The proximity of the bladder and ureters to the field of dissection during a hysterectomy can be especially challenging when the anatomy is distorted by adhesion formation from prior surgeries. One study demonstrated a 1.3% incidence of urinary tract injuries during laparoscopic hysterectomy.6 This included 0.54% ureteral injuries, 0.71% urinary bladder injuries, and 0.06% combined bladder and ureteral injuries.6 Particularly among patients with a prior CD, the risk of bladder injury can be significantly heightened.18

The reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique that we described offers multiple benefits. By starting the procedure from an untouched and avascular plane, dissection into the plane of the prior adhesions can be circumvented; thus, bleeding is limited and injury to the bladder and ureters is avoided or minimized. By using blunt and sharp dissection, thermal injury and delayed necrosis can be mitigated. Finally, with bladder mobilization well below the colpotomy site, more adequate vaginal tissue is free to be incorporated into the vaginal cuff closure, thereby limiting the risk of cuff dehiscence.16

While we have found this technique effective for patients with prior cesarean deliveries, it also may be applied to any patient who has a scarred anterior cul-de-sac. This could include patients with prior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect, or endometriosis. Despite the technique being a safeguard against bladder injury, surgeons must still use care in developing the spaces to avoid ureteral injury, especially in a setting of distorted anatomy.

- Page B. Nezhat & the advent of advanced operative video-laparoscopy. In: Nezhat C. Nezhat's History of Endoscopy. Tuttlingen, Germany: Endo Press; 2011:159-179. https://laparoscopy.blogs.com/endoscopyhistory/chapter_22. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Podratz KC. Degrees of freedom: advances in gynecological and obstetric surgery. In: American College of Surgeons. Remembering Milestones and Achievements in Surgery: Inspiring Quality for a Hundred Years, 1913-2012. Tampa, FL: Faircount Media Group; 2013:113-119. http://endometriosisspecialists.com/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/Degrees-of-Freedom-Advances-in-Gynecological-and-Obstetrical-Surgery.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2019.

- Kelley WE Jr. The evolution of laparoscopy and the revolution in surgery in the decade of the 1990s. JSLS. 2008;12:351-357.

- Tokunaga T. Video surgery expands its scope. Stanford Med. 1993/1994;11(2)12-16.

- Rooney CM, Crawford AT, Vassallo BJ, et al. Is previous cesarean section a risk for incidental cystotomy at the time of hysterectomy? A case-controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2041-2044.

- Tan-Kim J, Menefee SA, Reinsch CS, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy and urinary tract injury: experience in a health maintenance organization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1278-1286.

- Sinha R, Sundaram M, Lakhotia S, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy in women with previous cesarean sections. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:513-517.

- O'Hanlan KA. Cystosufflation to prevent bladder injury. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:195-197.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64:1-65.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy with DVD, 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Nezhat C, Grace LA, Razavi GM, et al. Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for laparoscopic hysterectomy after prior cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:629-633.

- Nezhat C, Xie J, Aldape D, et al. Use of laparoscopic modified nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for the treatment of extensive endometriosis. Cureus. 2014;6:e159.

- Yabuki Y, Sasaki H, Hatakeyama N, et al. Discrepancies between classic anatomy and modern gynecologic surgery on pelvic connective tissue structure: harmonization of those concepts by collaborative cadaver dissection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:7-15.

- Uhlenhuth E. Problems in the Anatomy of the Pelvis: An Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Co; 1953.

- Nezhat C, Grace, L, Soliemannjad, et al. Cesarean scar defect: what is it and how should it be treated? OBG Manag. 2016;28(4):32,34,36,38-39,53.

- Nezhat C, Kennedy Burns M, Wood M, et al. Vaginal cuff dehiscence and evisceration: a review. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:972-985.

- Nezhat C, Main J, Paka C, et al. Advanced gynecologic laparoscopy in a fast-track ambulatory surgery center. JSLS. 2014;18:pii:e2014.00291.

- Nezhat C, Falik R, McKinney S, et al. Pathophysiology and management of urinary tract endometriosis. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:359-372.

- Page B. Nezhat & the advent of advanced operative video-laparoscopy. In: Nezhat C. Nezhat's History of Endoscopy. Tuttlingen, Germany: Endo Press; 2011:159-179. https://laparoscopy.blogs.com/endoscopyhistory/chapter_22. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Podratz KC. Degrees of freedom: advances in gynecological and obstetric surgery. In: American College of Surgeons. Remembering Milestones and Achievements in Surgery: Inspiring Quality for a Hundred Years, 1913-2012. Tampa, FL: Faircount Media Group; 2013:113-119. http://endometriosisspecialists.com/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/Degrees-of-Freedom-Advances-in-Gynecological-and-Obstetrical-Surgery.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2019.

- Kelley WE Jr. The evolution of laparoscopy and the revolution in surgery in the decade of the 1990s. JSLS. 2008;12:351-357.

- Tokunaga T. Video surgery expands its scope. Stanford Med. 1993/1994;11(2)12-16.

- Rooney CM, Crawford AT, Vassallo BJ, et al. Is previous cesarean section a risk for incidental cystotomy at the time of hysterectomy? A case-controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2041-2044.

- Tan-Kim J, Menefee SA, Reinsch CS, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy and urinary tract injury: experience in a health maintenance organization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1278-1286.

- Sinha R, Sundaram M, Lakhotia S, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy in women with previous cesarean sections. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:513-517.

- O'Hanlan KA. Cystosufflation to prevent bladder injury. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:195-197.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64:1-65.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy with DVD, 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Nezhat C, Grace LA, Razavi GM, et al. Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for laparoscopic hysterectomy after prior cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:629-633.

- Nezhat C, Xie J, Aldape D, et al. Use of laparoscopic modified nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for the treatment of extensive endometriosis. Cureus. 2014;6:e159.

- Yabuki Y, Sasaki H, Hatakeyama N, et al. Discrepancies between classic anatomy and modern gynecologic surgery on pelvic connective tissue structure: harmonization of those concepts by collaborative cadaver dissection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:7-15.

- Uhlenhuth E. Problems in the Anatomy of the Pelvis: An Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Co; 1953.

- Nezhat C, Grace, L, Soliemannjad, et al. Cesarean scar defect: what is it and how should it be treated? OBG Manag. 2016;28(4):32,34,36,38-39,53.

- Nezhat C, Kennedy Burns M, Wood M, et al. Vaginal cuff dehiscence and evisceration: a review. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:972-985.

- Nezhat C, Main J, Paka C, et al. Advanced gynecologic laparoscopy in a fast-track ambulatory surgery center. JSLS. 2014;18:pii:e2014.00291.

- Nezhat C, Falik R, McKinney S, et al. Pathophysiology and management of urinary tract endometriosis. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:359-372.

Modern surgical techniques for gastrointestinal endometriosis

About 10% of all reproductive-aged women and 35% to 50% of women with pelvic pain and infertility are affected by endometriosis.1,2 The disease typically involves the reproductive tract organs, anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and uterosacral ligaments. However, disease outside of the reproductive tract occurs frequently and has been found on all organs except the spleen.3

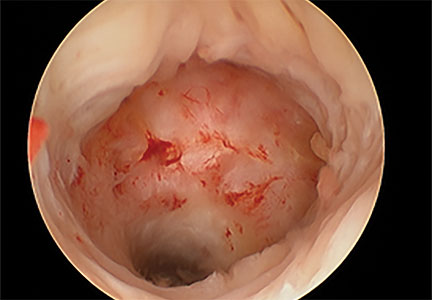

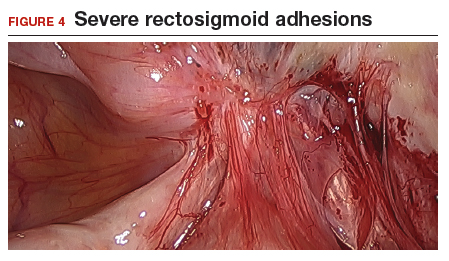

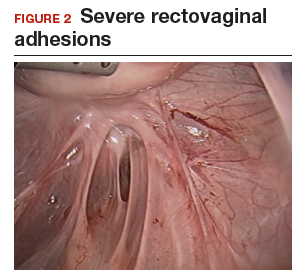

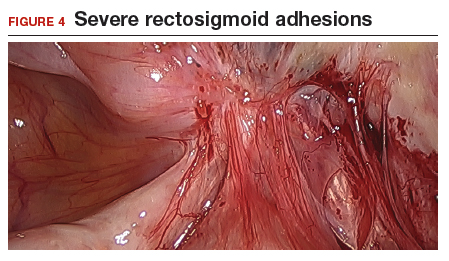

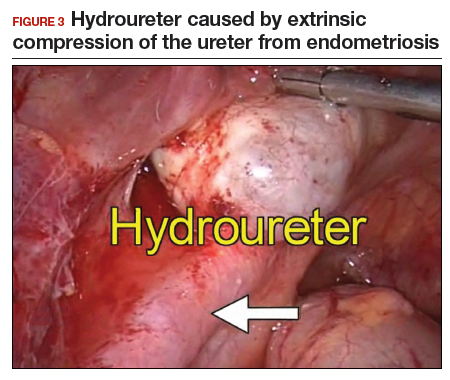

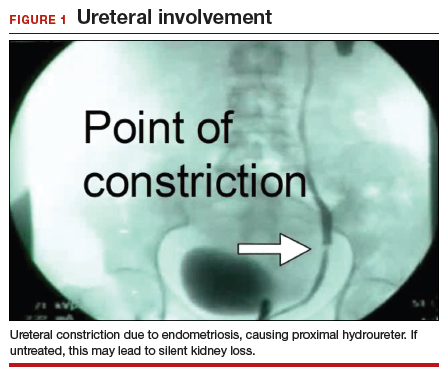

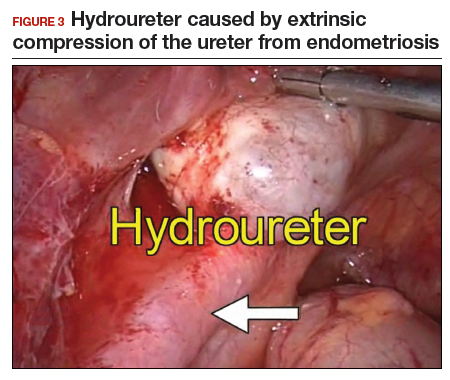

The bowel is the most common site for extragenital endometriosis, affected in an estimated 3.8% to 37% of patients with known endometriosis.4-7 Implants may be superficial, involving the bowel serosa and subserosa (FIGURE 1), or they can manifest as deeply infiltrating lesions involving the muscularis and mucosa (FIGURE 2). The rectosigmoid colon is the most common location for bowel endometriosis, followed by the rectum, ileum, appendix, and cecum4,8 (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5). Case reports also have described endometrial implants on the stomach and transverse colon.9 Although isolated bowel involvement has been recognized, most patients with bowel endometriosis have concurrent disease elsewhere.2,4

Historically, segmental resection was performed regardless of the anatomical location of the lesion.10 Even today, many surgeons continue to routinely perform segmental bowel resection as a first-line surgical approach.11 Unnecessary segmental resection, however, places patients at risk for short- and long-term postoperative morbidity, including the possibility of permanent ostomy. Modern surgical techniques, such as shaving excision and disc resection, have been performed to successfully treat bowel endometriosis with excellent long-term outcomes and fewer complications when compared with traditional segmental resection.2,12-16

In this article, we focus on the clinical indications and surgical techniques for video-laparoscopic management, but first we describe the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of bowel endometriosis.

Pathophysiology of bowel endometriosis

The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains unknown, as no single mechanism explains all clinical cases of the disease. The most popular proposed theory describes retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes.17 Once inside the peritoneal cavity, endometrial cells attach to and invade healthy peritoneum, establishing a blood supply necessary for growth and survival.

In the case of bowel endometriosis, deposition of effluxed endometrial cells may lead to an inflammatory response that increases the risk of adhesion formation, leading to potential cul-de-sac obliteration. Lesions may originate as Allen-Masters peritoneal defects, developing into deeply infiltrative rectovaginal septum lesions. The anatomical shelter theory contributes to lesions within the pelvis, with the rectosigmoid colon blocking the cephalad flow of effluxed menstrual blood from the pelvis, thus leading to a preponderance of lesions in the pelvis and along the rectosigmoid colon.2

Continue to: Clinical presentation and diagnosis...

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Women presenting with endometriosis of the bowel are typically of reproductive age and commonly report symptoms of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dyschezia. Some women also experience catamenial diarrhea, constipation, hematochezia, and bloating.2 The differential diagnosis of these symptoms is broad and includes irritable bowel disease, ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and malignancy.

Because of its nonspecific symptoms, bowel endometriosis is often misdiagnosed and the disease goes untreated for years.18 Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating reproductive-aged women with gastrointestinal symptoms and pelvic pain.

Physical examination can be helpful in making the diagnosis of endometriosis. During bimanual examination, findings such as a fixed, tender, or retroverted uterus, uterosacral ligament nodularity, or an enlarged adnexal mass representing an ovarian endometrioma may be appreciated. Rectovaginal exam can identify areas of tenderness and nodularity along the rectovaginal septum. Speculum exam may reveal a laterally displaced cervix or blue powder-burn lesions along the cervix or posterior fornix.19 Rarely, endometriosis is found on the perineum within an episiotomy scar.20

Imaging studies can be used in conjunction with physical examination findings to aid in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Images also guide preoperative planning by characterizing lesions based on their size, location, and depth of invasion. Hudelist and colleagues found transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) to have an overall sensitivity of 71% to 98% and a specificity of 92% to 100%.21 However, it was noted that the accuracy of the diagnosis was directly related to the experience of the sonographer, and lesions above the sigmoid colon were generally unable to be diagnosed. Other imaging modalities that have been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing bowel endometriosis include rectal water contrast TVUS,22,23 rectal endoscopic sonography,22 magnetic resonance imaging,22 and barium enema.24

Medical management

Medical therapy for patients with endometriosis is utilized with the goal of suppressing ovulation, lowering circulating hormone levels, and inducing endometrial atrophy. Medications commonly employed include gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists, anabolic steriods such as danazol, combined oral contraceptive pills, progestins, and aromatase inhibitors.

Continue to: To date, no optimal hormonal regimen...

To date, no optimal hormonal regimen has been established for the treatment of bowel endometriosis. Vercellini and colleagues demonstrated that progestins with and without low-dose estrogen improved symptoms of dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia.25 Ferrero and colleagues reported that 2.5 mg of norethindrone daily resulted in 53% of women with colorectal endometriosis reporting improved gastrointestinal symptoms.26 However, by 12 months of follow-up, 33% of these patients had elected to undergo surgical management.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, such as leuprolide acetate, also can be used to mitigate symptoms of bowel endometriosis or to decrease disease burden at the time of surgery, and they can be used with add-back norethindrone acetate. The use of these medications is limited by adverse effects, such as vasomotor symptoms and decreased bone mineral density when used for longer than 6 months.2

Medical therapy is commonly used for patients with mild to moderate symptoms and in those who are poor surgical candidates or decline surgical intervention. Medical therapy is especially useful when employed postoperatively to suppress the regrowth of microscopic ectopic endometrial tissue.

Patients must be counseled, however, that even with medical management, they may still require surgery in the future to control their symptoms and/or to preserve organ function.2

Surgical management

Surgical treatment for bowel endometriosis depends on the disease location, the size and depth of the lesion, the presence or absence of stricture, and the surgeon’s level of expertise.2,12,27-30

In our group, we advocate for video-laparoscopy, with or without robotic as sistance. Minimally invasive surgery offers reduced blood loss, shorter recovery time, and fewer postoperative complications compared with laparotomy.2,16,27,31-33 The conversion rate to laparotomy has been reported to be about 3% when performed by an experienced surgeon.12

Darai and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of 52 patients undergoing surgery for colorectal endometriosis via either laparoscopic or open colon resection.33 Blood loss was significantly lower in the laparoscopy group (1.6 vs 2.7 mg/L, P <.05). No difference was noted in long-term outcomes. In a retrospective study of 436 cases, Ruffo and colleagues showed that those who underwent laparoscopic colorectal resection had higher postoperative pregnancy rates compared with those who had laparotomy (57.6% vs 23.1%, P <.035).32

The goal of surgical management of bowel endometriosis is to remove as many of the endometriotic lesions as possible while minimizing short- and long-term complications. Three surgical approaches have been described: shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection.2

Some surgeons prefer traditional segmental resection of the bowel regardless of the anatomical site, citing reduced disease recurrence with this approach; however, traditional segmental resection confers increased risk of complications. Increasingly, in an effort to reduce morbidity, more surgeons are advocating for the less aggressive methods of shaving excision and disc resection.

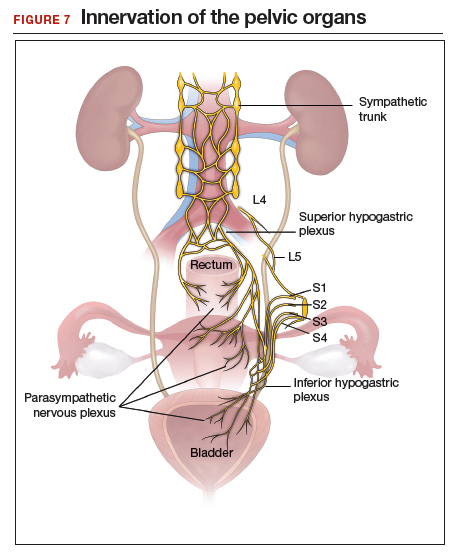

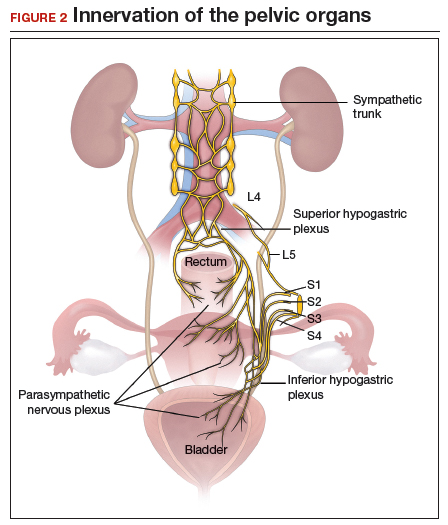

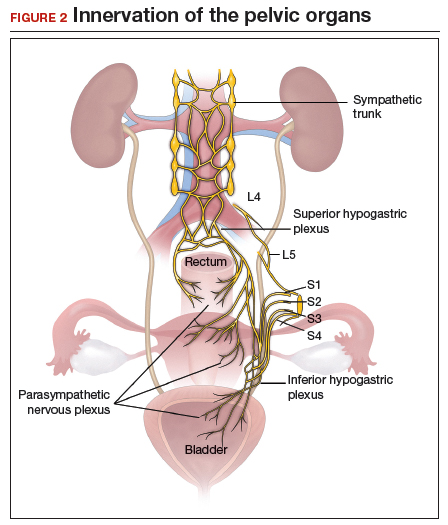

Aggressive resection at the level of the low rectum requires extensive surgical dissection of the retrorectal space, with the potential for inadvertent injury to surrounding neurovascular structures, such as the pelvic splanchnic nerves and superior and inferior hypogastric plexus.29 Injury to these structures can lead to significant complications, including bowel stenosis, fistula formation, constipation, and urinary retention. Complete resection of other areas, such as the small bowel, do not carry the same risks and may have more significant benefit to the patient than less aggressive techniques.

Our group recommends carefully balancing the risks and benefits of aggressive surgical treatment for each individual and treating the patient with the appropriate technique. Regardless of technique, surgical treatment of bowel endometriosis can lead to long-term improvements in pain and infertility.29,30,34,35

- The clinical presentation of bowel endometriosis is often nonspecific, with a broad differential diagnosis. Maintain a high index of suspicion when reproductive-aged women present for evaluation of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, bloating, dyschezia, or hematochezia.

- Symptomatic patients not desiring fertility, poor surgical candidates, and those declining surgical intervention may benefit from medical management. Patients who fail medical therapy, have severe symptoms, or experience infertility are candidates for surgical intervention.

- Surgical management involves shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection. Some surgeons advocate for aggressive segmental resection regardless of the endometriotic lesion's location. Based on our extensive experience, we prefer shaving excision for lesions below the sigmoid to avoid dissection into the retrorectal space and inadvertent injury to nerve tissue controlling bowel and bladder function.

- Following shaving excision, patients experience low complication rates29,39,40 and favorable long-term outcomes.15,40,56 For lesions above the sigmoid colon, including the small bowel, segmental resection or disc resection for smaller lesions are reasonable surgical approaches.

Continue to: Shaving excision...

Shaving excision

The most conservative approach to resection of bowel endometriosis is shaving excision; this involves removing endometriotic tissue layer-by-layer until healthy, underlying tissue is encountered.2 With bowel endometriosis, the goal of shaving excision is to remove as much of the diseased tissue as possible while leaving behind the mucosal layer and a portion of the muscularis.2,15,16,36-38 This is the most conservative of the 3 surgical techniques and is associated with the lowest complication rate.2,14,15,36,37

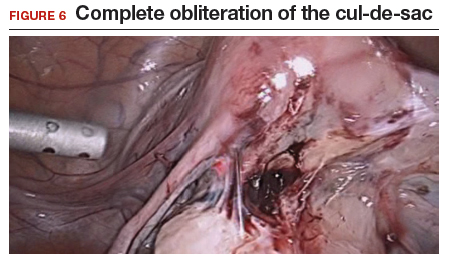

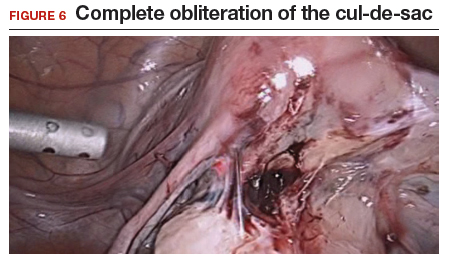

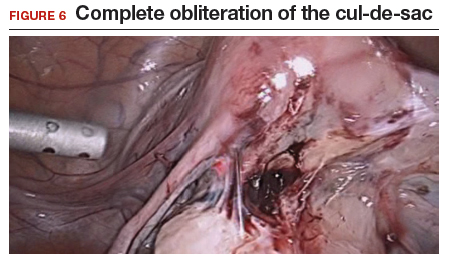

Our group reported on 185 women who underwent shaving excision for bowel endometriosis. At the time of surgery, 80 women had complete obliteration of the cul-de-sac (FIGURE 6). Of the study patients, 174 patients were available for follow-up, with 93% reporting moderate to complete pain relief.15

In a retrospective analysis of 3,298 surgeries for rectovaginal endometriosis in which shaving excision was used on all but 1% of patients, Donnez and colleagues reported a very low complication rate, with 1 case of rectal perforation, 1 case of fecal peritonitis, and 3 cases of ureteral injury.39

Roman and colleagues described the use of shaving excision for rectal endometriosis using plasma energy (n = 54) and laparoscopic scissors (n = 68).40 Only 4% of patients reported experiencing symptom recurrence, and the pregnancy rate was 65.4%, with 59% of those patients spontaneously conceiving. Two cases of rectal fistula were noted.

Disc resection

Laparoscopic disc excision has been described in the literature since the 1980s, and the technique involves the full-thickness removal of the diseased portion of the bowel, followed by closure of the remaining defect.2,12-14,28,29,31,41-45 To be appropriate for this technique, a lesion should involve only a portion of the bowel wall and, preferably, less than one-half of the bowel circumference.2,42 Disc excision results in excellent outcomes with fewer postoperative complications than segmental resection, but with more complications when compared to shaving excision.2,12,13,29,45,46

We reported on a series of 141 women with bowel endometriosis who underwent disc excision.2 At 1-month follow-up, 87% of patients experienced an improvement in their symptoms. No cases required conversion to laparotomy or were complicated by rectovaginal fistula formation, ureteral injury, bowel perforation, or pelvic abscess.2

Continue to: Segmental resection...

Segmental resection

The most aggressive surgical approach, segmental resection involves complete removal of a diseased portion of bowel, followed by side-to-side or end-to-end reanastomosis of the adjacent segments.2 For this procedure, a multidisciplinary approach is recommended, with involvement of a colorectal surgeon or gynecologic oncologist trained in performing bowel resections. Segmental resection is indicated for lesions that are larger than 3 cm, circumferential, obstructive, or multifocal.

Given the higher complication rate associated with this procedure and the good outcomes associated with less invasive techniques, we avoid segmental resection whenever possible, especially for lesions near the anal verge.2

Complications associated with surgical approach

In 2005, our group reported on a cohort of 178 women who underwent laparoscopic treatment of deeply infiltrative bowel endometriosis with shaving excision (n = 93), disc excision (n = 38), and segmental resection (n = 47).34 The major complication rate was significantly higher for those undergoing segmental resection (12.5%, P <.001); only 7.7% of those who underwent disc resection experienced a major complication; and none were observed in the group treated with shaving excision.

In 2011, De Cicco and colleagues conducted a systematic review of 1,889 patients who underwent segmental bowel resection.35 The major complication rate was 11%, with a leakage rate of 2.7%, fistula rate of 1.8%, major obstruction rate of 2.7%, and hemorrhage rate of 2.5%. Many of these complications, however, occurred in patients who had low rectal resections.

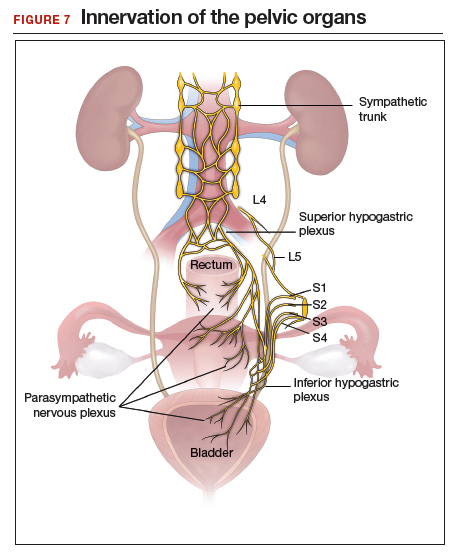

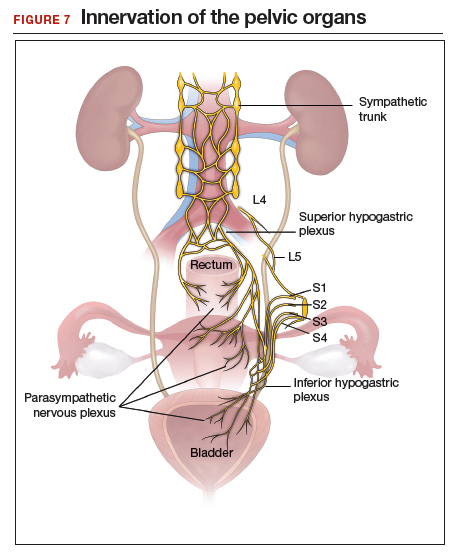

Regardless of surgical approach, the complication rate is related to the surgeon’s ability to preserve the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses and the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve bundles (FIGURE 7). Nerve-sparing techniques should be used to decrease the incidence of postoperative bowel, bladder, and sexual function complications.2

Our group’s preferences

In our practice, we emphasize that the choice of surgical technique depends on the location, size, and depth of the lesion, as well as the extent of bowel wall circumferential invasion.2

We categorize lesions by their anatomic location: those above the sigmoid colon, on the sigmoid colon, on the rectosigmoid colon, and on the rectum. For lesions above the sigmoid colon, segmental or disc resection is appropriate.2 We recommend segmental resection for multifocal lesions, lesions larger than 3 cm, or for lesions involving more than one-third of the bowel lumen.37,44,45,47 Disc resection is appropriate for lesions smaller than 3 cm even if the bowel lumen is involved.44,45,48 If endometriosis is encountered in any location along the bowel, appendectomy can be performed even without visible disease, due to a high incidence of occult disease of the appendix.49,50

When lesions involve the sigmoid colon, we prefer utilizing shaving excision when possible to limit dissection of the retrorectal space and pelvic sidewall nerves.2 Segmental resection at or below the sigmoid colon has been associated with postoperative surgical site leakage51 and long-term bowel and bladder dysfunction with risk of permanent colostomy.52,53 For lesions smaller than 3 cm or involving less than one-third of the bowel lumen, disc resection can be performed. Segmental resection is required if multifocal disease or obstruction are present, if lesions are larger than 3 cm, or if more than one-third of the bowel lumen is involved.

For lesions along the rectosigmoid colon, we prefer utilizing shaving excision when possible.2 Disc excision can be performed utilizing a transanal approach, being mindful to minimize dissection of the retroperitoneal space and pelvic sidewall nerves.48 Segmental resection is avoided even with lesions larger than 3 cm, unless prior surgery has failed. Approaches for segmental resection can utilize laparoscopy or the natural orifices of the rectum or vagina.31,51

For lesions on the rectum, we strongly advise shaving excision.2 Evidence fails to show that the benefits of segmental resection outweigh the risks when compared to conservative techniques at the rectum.30,39,54 There is evidence indicating that aggressive surgery 5 to 8 cm from the anal verge is predictive of postoperative complications.55 In our group, we use shaving excision to remove as much disease as possible without compromising the integrity of the bowel wall or surrounding neurovascular structures. We err on the side of caution, leaving some of the disease on the rectum to avoid rectal perforation, and plan for postoperative hormonal suppression in these patients.

For patients desiring fertility, successful pregnancy is often achieved using the shaving technique.41

- Giudice LC. Clinical practice. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2389-2398.

- Nezhat C, Li A, Falik R, et al. Bowel endometriosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:549-562.

- Markham SM, Carpenter SE, Rock JA. Extrapelvic endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:193-219.

- Veeraswamy A, Lewis M, Mann A, et al. Extragenital endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:449-466.

- Redwine DB. Ovarian endometriosis: a marker for more extensive pelvic and intestinal disease. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:310-315.

- Weed JC, Ray JE. Endometriosis of the bowel. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:727-730.

- Wheeler JM. Epidemiology of endometriosis-associated infertility. J Reprod Med. 1989;34:41-46.

- Redwine DB. Intestinal endometriosis. In: Redwine DB. Surgical Management of Endometriosis. New York, NY: Martin Dunitz; 2004:196.

- Hartmann D, Schilling D, Roth SU, et al. [Endometriosis of the transverse colon--a rare localization]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2002;127:2317-2320.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Endometriosis: ancient disease, ancient treatments. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(6 suppl):S1-62.

- Macafee CH, Greer HL. Intestinal endometriosis. A report of 29 cases and a survey of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1960;67:539-555.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Ambroze W, et al. Laparoscopic repair of small bowel and colon. A report of 26 cases. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:88-89.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Pennington E, et al. Laparoscopic disk excision and primary repair of the anterior rectal wall for the treatment of full-thickness bowel endometriosis. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:682-685.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F. Evaluation of safety of videolaseroscopic treatment of bowel endometriosis. Presented at: 44th Annual Meeting of the American Fertility Society; October, 1988; Atlanta, GA.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Pennington E. Laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative rectosigmoid colon and rectovaginal septum endometriosis by the technique of videolaparoscopy and the CO2 laser. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:664-667.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison CP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1986;45:778-783.

- Sourial S, Tempest N, Hapangama DK. Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Int J Reprod Med. 2014;2014:179515.

- Skoog SM, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Levy MJ, et al. Intestinal endometriosis: the great masquerader. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004;6:405-409.

- Alabiso G, Alio L, Arena S, et al. How to manage bowel endometriosis: the ETIC approach. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:517-529.

- Heller DS, Lespinasse P, Mirani N. Endometriosis of the perineum: a rare diagnosis usually associated with episiotomy. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:e48-e49.

- Hudelist G, English J, Thomas AE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for non-invasive diagnosis of bowel endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37:257-263.

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, et al. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591.

- Menada MV, Remorgida V, Abbamonte LH, et al. Transvaginal ultrasonography combined with water-contrast in the rectum in the diagnosis of rectovaginal endometriosis infiltrating the bowel. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:699-700.

- Gordon RL, Evers K, Kressel HY, et al. Double-contrast enema in pelvic endometriosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;138:549-552.

- Vercellini P, Pietropaolo G, De Giorgi O, et al. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1375-1387.

- Ferrero S, Camerini G, Ragni N, et al. Norethisterone acetate in the treatment of colorectal endometriosis: a pilot study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:94-100.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic treatment of bowel, bladder, and ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2011;15:387-392.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Laparoscopic management of bowel endometriosis: predictors of severe disease and recurrence. JSLS. 2011;15:431-438.

- Roman H, Milles M, Vassilieff M, et al. Long-term functional outcomes following colorectal resection versus shaving for rectal endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:762.e1-762.e9.

- Kent A, Shakir F, Rockall T, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for severe rectovaginal endometriosis compromising the bowel: a prospective cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:526-534.

- Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Pennington E. Laparoscopic proctectomy for infiltrating endometriosis of the rectum. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:1129-1132.

- Ruffo G, Scopelliti F, Scioscia M, et al. Laparoscopic colorectal resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis: analysis of 436 cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:63-67.

- Darai E, Dubernard G, Coutant C, et al. Randomized trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open colorectal resection for endometriosis: morbidity, symptoms, quality of life, and fertility. Ann Surg. 2010;251:1018-1023.

- Mohr C, Nezhat FR, Nezhat CH, et al. Fertility considerations in laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative bowel endometriosis. JSLS. 2005;9:16-24.

- De Cicco C, Corona R, Schonman R, et al. Bowel resection for deep endometriosis: a systematic review. BJOG. 2011;118:285-291.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat FR. Safe laser endoscopic excision or vaporization of peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1989;52:149-151.

- Donnez J, Squifflet J. Complications, pregnancy and recurrence in a prospective series of 500 patients operated on by the shaving technique for deep rectovaginal endometriotic nodules. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1949-1958.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison CP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy and videolaseroscopy. Contrib Gynecol Obstet. 1987;16:303-312.

- Donnez J, Jadoul P, Colette S, et al. Deep rectovaginal endometriotic nodules: perioperative complications from a series of 3,298 patients operated on by the shaving technique. Gynecol Surg. 2013;10:31-40.

- Roman H, Moatassim-Drissa S, Marty N, et al. Rectal shaving for deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum: a 5-year continuous retrospective series. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:1438-1445.e2.

- Mohr C, Nezhat FR, Nezhat CH, et al. Fertility considerations in laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative bowel endometriosis. JSLS. 2005;9:16-24.

- Jerby BL, Kessler H, Falcone T, et al. Laparoscopic management of colorectal endometriosis. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:1125-1128.

- Coronado C, Franklin RR, Lotze EC, et al. Surgical treatment of symptomatic colorectal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1990;53:411-416.

- Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Gagliardi ML, et al. Discoid or segmental rectosigmoid resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis: a case-control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:444-449.

- Landi S, Pontrelli G, Surico D, et al. Laparoscopic disk resection for bowel endometriosis using a circular stapler and a new endoscopic method to control postoperative bleeding from the stapler line. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:205-209.

- Slack A, Child T, Lindsey I, et al. Urological and colorectal complications following surgery for rectovaginal endometriosis. BJOG. 2007;114:1278-1282.

- Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Bruni F, et al. Nerve-sparing laparoscopic eradication of deep endometriosis with segmental rectal and parametrial resection: the Negrar method. A single-center, prospective, clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2029-2045.

- Roman H, Abo C, Huet E, et al. Deep shaving and transanal disc excision in large endometriosis of mid and lower rectum: the Rouen technique. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2626-2627.

- Gustofson RL, Kim N, Liu S, et al. Endometriosis and the appendix: a case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:298-303.

- Berker B, Lashay N, Davarpanah R, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy in patients with endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:206-209.

- Ret Dávalos ML, De Cicco C, D'Hoore A, et al. Outcome after rectum or sigmoid resection: a review for gynecologists. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:33-38.

- Alves A, Panis Y, Mathieu P, et al; Association Française de Chirurgie (AFC). Mortality and morbidity after surgery of mid and low rectal cancer. Results of a French prospective multicentric study. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:509-514.

- Camilleri-Brennan J, Steele RJ. Objective assessment of morbidity and quality of life after surgery for low rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:61-66.

- Acien P, Núñez C, Quereda F, et al. Is a bowel resection necessary for deep endometriosis with rectovaginal or colorectal involvement? Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:449-455.

- Abrão MS, Petraglia F, Falcone T, et al. Deep endometriosis infiltrating the recto-sigmoid: critical factors to consider before management. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:329-339.

- Donnez J, Nisolle M, Gillerot S, et al. Rectovaginal septum adenomyotic nodules: a series of 500 cases. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1014-1018.

About 10% of all reproductive-aged women and 35% to 50% of women with pelvic pain and infertility are affected by endometriosis.1,2 The disease typically involves the reproductive tract organs, anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and uterosacral ligaments. However, disease outside of the reproductive tract occurs frequently and has been found on all organs except the spleen.3

The bowel is the most common site for extragenital endometriosis, affected in an estimated 3.8% to 37% of patients with known endometriosis.4-7 Implants may be superficial, involving the bowel serosa and subserosa (FIGURE 1), or they can manifest as deeply infiltrating lesions involving the muscularis and mucosa (FIGURE 2). The rectosigmoid colon is the most common location for bowel endometriosis, followed by the rectum, ileum, appendix, and cecum4,8 (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5). Case reports also have described endometrial implants on the stomach and transverse colon.9 Although isolated bowel involvement has been recognized, most patients with bowel endometriosis have concurrent disease elsewhere.2,4

Historically, segmental resection was performed regardless of the anatomical location of the lesion.10 Even today, many surgeons continue to routinely perform segmental bowel resection as a first-line surgical approach.11 Unnecessary segmental resection, however, places patients at risk for short- and long-term postoperative morbidity, including the possibility of permanent ostomy. Modern surgical techniques, such as shaving excision and disc resection, have been performed to successfully treat bowel endometriosis with excellent long-term outcomes and fewer complications when compared with traditional segmental resection.2,12-16

In this article, we focus on the clinical indications and surgical techniques for video-laparoscopic management, but first we describe the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of bowel endometriosis.

Pathophysiology of bowel endometriosis

The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains unknown, as no single mechanism explains all clinical cases of the disease. The most popular proposed theory describes retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes.17 Once inside the peritoneal cavity, endometrial cells attach to and invade healthy peritoneum, establishing a blood supply necessary for growth and survival.

In the case of bowel endometriosis, deposition of effluxed endometrial cells may lead to an inflammatory response that increases the risk of adhesion formation, leading to potential cul-de-sac obliteration. Lesions may originate as Allen-Masters peritoneal defects, developing into deeply infiltrative rectovaginal septum lesions. The anatomical shelter theory contributes to lesions within the pelvis, with the rectosigmoid colon blocking the cephalad flow of effluxed menstrual blood from the pelvis, thus leading to a preponderance of lesions in the pelvis and along the rectosigmoid colon.2

Continue to: Clinical presentation and diagnosis...

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Women presenting with endometriosis of the bowel are typically of reproductive age and commonly report symptoms of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dyschezia. Some women also experience catamenial diarrhea, constipation, hematochezia, and bloating.2 The differential diagnosis of these symptoms is broad and includes irritable bowel disease, ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and malignancy.

Because of its nonspecific symptoms, bowel endometriosis is often misdiagnosed and the disease goes untreated for years.18 Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating reproductive-aged women with gastrointestinal symptoms and pelvic pain.

Physical examination can be helpful in making the diagnosis of endometriosis. During bimanual examination, findings such as a fixed, tender, or retroverted uterus, uterosacral ligament nodularity, or an enlarged adnexal mass representing an ovarian endometrioma may be appreciated. Rectovaginal exam can identify areas of tenderness and nodularity along the rectovaginal septum. Speculum exam may reveal a laterally displaced cervix or blue powder-burn lesions along the cervix or posterior fornix.19 Rarely, endometriosis is found on the perineum within an episiotomy scar.20

Imaging studies can be used in conjunction with physical examination findings to aid in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Images also guide preoperative planning by characterizing lesions based on their size, location, and depth of invasion. Hudelist and colleagues found transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) to have an overall sensitivity of 71% to 98% and a specificity of 92% to 100%.21 However, it was noted that the accuracy of the diagnosis was directly related to the experience of the sonographer, and lesions above the sigmoid colon were generally unable to be diagnosed. Other imaging modalities that have been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing bowel endometriosis include rectal water contrast TVUS,22,23 rectal endoscopic sonography,22 magnetic resonance imaging,22 and barium enema.24

Medical management

Medical therapy for patients with endometriosis is utilized with the goal of suppressing ovulation, lowering circulating hormone levels, and inducing endometrial atrophy. Medications commonly employed include gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists, anabolic steriods such as danazol, combined oral contraceptive pills, progestins, and aromatase inhibitors.

Continue to: To date, no optimal hormonal regimen...

To date, no optimal hormonal regimen has been established for the treatment of bowel endometriosis. Vercellini and colleagues demonstrated that progestins with and without low-dose estrogen improved symptoms of dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia.25 Ferrero and colleagues reported that 2.5 mg of norethindrone daily resulted in 53% of women with colorectal endometriosis reporting improved gastrointestinal symptoms.26 However, by 12 months of follow-up, 33% of these patients had elected to undergo surgical management.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, such as leuprolide acetate, also can be used to mitigate symptoms of bowel endometriosis or to decrease disease burden at the time of surgery, and they can be used with add-back norethindrone acetate. The use of these medications is limited by adverse effects, such as vasomotor symptoms and decreased bone mineral density when used for longer than 6 months.2

Medical therapy is commonly used for patients with mild to moderate symptoms and in those who are poor surgical candidates or decline surgical intervention. Medical therapy is especially useful when employed postoperatively to suppress the regrowth of microscopic ectopic endometrial tissue.

Patients must be counseled, however, that even with medical management, they may still require surgery in the future to control their symptoms and/or to preserve organ function.2

Surgical management

Surgical treatment for bowel endometriosis depends on the disease location, the size and depth of the lesion, the presence or absence of stricture, and the surgeon’s level of expertise.2,12,27-30

In our group, we advocate for video-laparoscopy, with or without robotic as sistance. Minimally invasive surgery offers reduced blood loss, shorter recovery time, and fewer postoperative complications compared with laparotomy.2,16,27,31-33 The conversion rate to laparotomy has been reported to be about 3% when performed by an experienced surgeon.12

Darai and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of 52 patients undergoing surgery for colorectal endometriosis via either laparoscopic or open colon resection.33 Blood loss was significantly lower in the laparoscopy group (1.6 vs 2.7 mg/L, P <.05). No difference was noted in long-term outcomes. In a retrospective study of 436 cases, Ruffo and colleagues showed that those who underwent laparoscopic colorectal resection had higher postoperative pregnancy rates compared with those who had laparotomy (57.6% vs 23.1%, P <.035).32

The goal of surgical management of bowel endometriosis is to remove as many of the endometriotic lesions as possible while minimizing short- and long-term complications. Three surgical approaches have been described: shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection.2

Some surgeons prefer traditional segmental resection of the bowel regardless of the anatomical site, citing reduced disease recurrence with this approach; however, traditional segmental resection confers increased risk of complications. Increasingly, in an effort to reduce morbidity, more surgeons are advocating for the less aggressive methods of shaving excision and disc resection.