User login

Update on pelvic surgery

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Over the past 10 years, the midurethral sling has replaced the Burch urethropexy as the most common surgical procedure for correcting stress urinary incontinence (SUI). In this “Update” on midurethral slings, we highlight three recently published studies that compare popular surgical approaches to SUI:

- the original tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) technique (FIGURE [“A”])

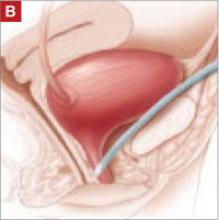

- the suprapubic urethral support sling (SPARC) (FIGURE [“B”])

- the transobturator tape (TOT) technique (FIGURE [“C”])

- the traditional pubovaginal sling (PVS), placed at the bladder neck (FIGURE [“D”]).

FIGURE [“A”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) technique

FIGURE [“B”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Suprapubic urethral support sling (SPARC)

FIGURE [“C”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Transobturator tape (TOT) technique

FIGURE [“D”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Pubovaginal sling (PVS)

We’ve had a decade-plus of experience with the sling

The midurethral sling, first introduced as the tension-free vaginal tape, or TVT (Gynecare), was quick to be adopted because:

- it offers a minimally invasive approach

- it is highly efficacious

- serious adverse events are rare.

TVT utilizes a 5-mm trocar that is passed from the vagina through the retropubic space, exiting via small suprapubic incisions. A strip of permanent polypropylene mesh attached to these trocars is placed under the midportion of the urethra (FIGURE [“A”]).

We now have 11 years of follow-up data to support the use of the TVT midurethral sling for SUI.1

As TVT gained popularity, surgical equipment manufacturers developed various “kits,” so to speak, for placing a midurethral sling. Many have included innovations that have theoretical advantages over traditional TVT. Some place smaller, 3-mm trocars in a similar “bottom-up” fashion, as the TVT sling does; others utilize smaller trocars that are placed “top down” through the retropubic space into the vagina.

A later generation of slings uses the transobturator approach, to avoid blind passage of trocars through the retropubic space. These slings can be placed “in to out” or “out to in,” and rest in a slightly different orientation under the midurethra.

In an effort to make the procedure even more minimally invasive, some manufacturers now offer slings that are placed through one vaginal incision, thereby avoiding additional suprapubic or groin incisions. Other kits have made alterations to the polypropylene mesh by heat-sealing the material or applying a coating.

Such modifications haven’t always been improvements—some sling kits carried a higher incidence of mesh-related complications, and certain ones were removed from the market. And, although the number of commercially available midurethral sling kits has exploded, we’ve seen scant data published that compare the traditional TVT method with alternative approaches. Those alternatives may be considered midurethral slings, but we haven’t known whether minor variations in technique, or in the instrumentation, translate to improvements in long-term efficacy.

More readjustments for retention are needed after SPARC (vs. TVT)

Lord HE, Taylor JD, Finn JC, et al. A randomized controlled equivalence trial of short-term complications and efficacy of tension-free vaginal tape and suprapubic urethral support sling for treating stress incontinence. BJU Int. 2006;98:367–376.

This randomized, controlled trial compared TVT with SPARC to treat SUI. The study was designed as an equivalence trial: the investigators sought to determine if the “newer” intervention of the two (SPARC) is therapeutically equivalent to the existing intervention (TVT)—not whether one is superior. They therefore looked to see if patients who underwent TVT and those who underwent SPARC had the same rate (within a 5% margin) of bladder injury and other secondary outcomes.

Subjects were eligible to participate if they had SUI on the basis of urodynamic or clinical parameters. They were unaware of their assigned treatment, underwent TVT or SPARC, and were reevaluated 6 weeks postoperatively. Intraoperative, postoperative, and 6-week follow-up data were recorded by the study surgeon.

Three hundred and one patients were enrolled; 147 underwent TVT and 154 underwent SPARC. The groups were similar in regard to all baseline characteristics.

No significant difference was noted between the groups in the primary outcome, which was the rate of bladder perforation (TVT, 0.7%; SPARC, 1.9% [p=.62]). This effect remained after controlling for age, parity, prior urinary incontinence surgery, other concomitant surgery, and the surgeon’s level of experience. There were no intergroup differences in perioperative blood loss, urgency, or objective cure of SUI (defined as negative cough stress test) 6 weeks after surgery.

Subjects who underwent SPARC were more likely to experience urinary retention that required surgical readjustment of the sling (SPARC, 10 of 154; TVT, none [p=.002]). Although the objective cure rate was similar across groups, the subjective cure rate was significantly different (TVT, 87.1%; SPARC, 76.5% [p=.03]).

Regression analysis revealed that subjects who had prior surgery for urinary incontinence and those whose surgery was performed by a comparatively less experienced physician were more likely to report persistence of SUI symptoms.

This study reflects general clinical practice, in that it was conducted across a heterogeneous sample of subjects who had both primary and recurrent stress incontinence. Although the rate of bladder perforation was equivalent across groups, more patients who underwent SPARC required loosening of the sling postoperatively to relieve urinary retention.

These data suggest that the SPARC sling may be more difficult to adjust correctly even though it is designed with a tensioning suture. The difficulty may be a consequence of 1) smaller-caliber trocar tunnels or 2) the “top-down” approach less accurately locating the sling at the midportion of the urethra.

This study would have been more rigorous and the results, stronger, if postoperative assessment was made by a blinded examiner. An exceptional positive aspect of study design was that the investigators considered the surgeon’s level of experience—a variable that can certainly affect outcome.

Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:611–621.

This randomized, controlled trial compared the efficacy of TVT with the transobturator tape (TOT) technique. Like Lord and colleagues’ study just discussed, it was conducted as an equivalence trial—to determine whether TOT is equivalent to TVT.

The primary outcome was abnormal bladder function 12 months after surgery, defined as the presence of any of the following:

- incontinence symptoms

- positive cough stress test

- retreatment for SUI

- treatment for postoperative urinary retention.

Women who had urodynamic stress incontinence were recruited from three academic centers; excluded were women who had detrusor overactivity, postvoid residual volume >100 mL, prior sling surgery, or contraindications to a midurethral sling.

For the retropubic approach, TVT was used. For the transobturator approach, the Monarc Subfascial Hammock (American Medical Systems) was used. Here, the tape is placed in an “outside-in” fashion.

Subjects completed a baseline bladder diary and a series of validated questionnaires. Postoperatively, subjects were followed for 2 years. Follow-up data included validated questionnaires, bladder diary, pelvic organ prolapse quantification, cough stress test, and postvoid residual volume determination. It was not possible to blind subjects or surgeons, but all postoperative assessments and exams were performed by a blinded nurse.

The investigators sought to determine if TVT and TOT yielded an equivalent (within a 15% margin) rate of abnormal bladder function.

Eventually, 170 patients underwent randomization and surgery (88, TVT; 82, TOT). Baseline demographic, clinical, and incontinence severity data were similar across groups.

Bladder perforation was more common with TVT than with TOT (7% and 0, respectively [p=.02]). Abnormal bladder function was noted in 46.6% of TVT subjects and in 42.7% of TOT subjects, with a noninferiority test demonstrating equivalence (p=.006). One year after surgery, 79% of patients in the TVT group and 82% of patients in the TOT group reported that bladder symptoms were “much better” or “very much better” (p=.88). No significant difference was noted between groups in any of the questionnaire responses after surgery.

This study has many strengths, including rigorous assessments, use of a blinded nurse-examiner to collect postoperative data, and a battery of validated questionnaires used throughout the study. In addition, the primary outcome measure, abnormal bladder function, is defined by stringent criteria that combine subjective and objective components, efficacy, and adverse events.

It will be interesting to see if the efficacy of TOT is maintained over time. The authors of the article point out that several transobturator sling kits are available, utilizing various trocar shapes, different approaches (i.e., “in to out”), and different types of mesh; this may mean variable rates of complications and different degrees of efficacy from one kit to the next.

Also notable in this study is that subjects had relatively high Valsalva leak-point pressures (approaching 100 cm H2O) in both groups.

Which technique is best for SUI with intrinsic sphincter deficiency?

Jeon MJ, Jung HJ, Chung SM, et al. Comparison of the treatment outcome of pubovaginal sling, tension-free vaginal tape, and transobturator tape for stress urinary incontinence with intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:76.e1–76.e4.

This retrospective cohort study was designed to evaluate techniques for treating severe SUI. Researchers were mainly interested in patients who had intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), defined as a Valsalva leak-point pressure <60 cm H2O or maximal urethral closure pressure <20 cm H2O.

The pubovaginal (bladder neck) sling (PVS) has been considered the gold standard therapeutic option for patients who have ISD. Recently, however, data have shown satisfactory outcomes using TVT in this setting.2,3 The aim of this study, therefore, was to compare PVS, TVT, and TOT for treating SUI in patients who had ISD. (Note: The researchers used Uratape [Mentor-Purgès] for the transobturator sling.)

The study included 253 subjects who had ISD and who underwent surgical intervention (87, PVS; 94, TVT; 92, TOT); women who had detrusor overactivity and voiding dysfunction were excluded. Follow-up assessments were performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months and annually thereafter. Outcomes studied included complications and rates of cure; the latter was defined as 1) the absence of subjective complaints of leakage and 2) a negative cough stress test.

Median follow-up was 36, 24, and 12 months in the PVS, TVT, and TOT groups, respectively. All groups were similar in regard to baseline clinical and demographic characteristics. Bladder perforation was rare (PVS, 1; TVT and TOT, 0). No significant difference was noted across techniques in the rate of de novo urgency, voiding dysfunction, reoperation for urinary retention, and recurrent urinary tract infection.

Two years after surgery, the cure rate for the three procedures differed significantly: PVS and TVT, 87% each; TOT, 35% (p<.0001). A Cox proportional hazards regression model revealed that the risk of treatment failure with PVS was no different than it was for TVT. However, this model demonstrated that the risk of failure was 4.6 times higher for TOT compared with PVS (p<.0001).

This study is subject to the limitations of any retrospective study. It is unique, however, in that investigators focused on a more severe sample of subjects with ISD. In addition, the authors of the study used the appropriate statistical techniques to attempt to control for potential confounders.

Although the rate of cure was higher with TVT than with TOT, the rate of voiding dysfunction (i.e., the need for catheterization longer than 1 month after surgery) and de novo urgency was higher with TVT as well. This finding suggests that TVT provides more compressive force around the urethra than TOT does; on the other hand, it is possible instead that the difference arises in the method of tensioning of various types of sling.

Last, the study surgeon conducted the postoperative evaluations and was not blinded. This may have introduced bias into the assessments.

As more long-term data become available about different approaches to placing a midurethral sling, it’s likely that we will learn that not all techniques are equal. A customized approach—one that takes into account the individual patient’s clinical parameters—may be necessary to yield long-term efficacy with a sling.

Although, as the authors of this Update discuss, there are several surgical approaches to stress urinary incontinence (tension-free vaginal tape, suprapubic urethral support sling, transobturator tape, pubovaginal sling placed at the bladder neck), coding for the procedure is limited to a single Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code when surgery is performed via a vaginal approach. CPT code 57288 ( Sling operation for stress incontinence [e.g., fascia or synthetic] ) has been assigned 21.59 relative value units in 2008 and should be reported no matter what type of sling is placed or what method is used to place it.

Failed placement

On occasion, sling material erodes or creates other problems for the patient, such that it must be removed or revised. To report correction of this adverse outcome, bill with 57287 (Removal or revision of sling for stress incontinence [e.g., fascia or synthetic]). If revision must be performed within the global period for the original procedure by the surgeon who placed the sling, append modifier -78 (Unplanned return to the operating/procedure room by the same physician following initial procedure for a related procedure during the postoperative period) to the revision code.

Minimally invasive placement

If you perform a sling procedure laparoscopically, report 51992 (Laparoscopy, surgical; sling operation for stress incontinence [e.g., fascia or synthetic]) instead. No corresponding code exists for laparoscopic revision of a sling procedure; under CPT rules, your only course is to report 51999 (Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, bladder).—MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC-OBGYN, MA

1. Nilsson CG, Palva K, Rezapour M, Falconer C. Eleven years prospective follow-up of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure for treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urygynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1043-1047.

2. Rezapour M, Falconer C, Ulmsten U. Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) in stress incontinent women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD)—a long-term follow-up. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(Suppl 2):S12-S14.

3. Meschia M, Pifarotti P, Buonaguidi A, Gattei U, Spennacchio M. Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women with low-pressure urethra. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;122:118-121.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Over the past 10 years, the midurethral sling has replaced the Burch urethropexy as the most common surgical procedure for correcting stress urinary incontinence (SUI). In this “Update” on midurethral slings, we highlight three recently published studies that compare popular surgical approaches to SUI:

- the original tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) technique (FIGURE [“A”])

- the suprapubic urethral support sling (SPARC) (FIGURE [“B”])

- the transobturator tape (TOT) technique (FIGURE [“C”])

- the traditional pubovaginal sling (PVS), placed at the bladder neck (FIGURE [“D”]).

FIGURE [“A”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) technique

FIGURE [“B”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Suprapubic urethral support sling (SPARC)

FIGURE [“C”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Transobturator tape (TOT) technique

FIGURE [“D”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Pubovaginal sling (PVS)

We’ve had a decade-plus of experience with the sling

The midurethral sling, first introduced as the tension-free vaginal tape, or TVT (Gynecare), was quick to be adopted because:

- it offers a minimally invasive approach

- it is highly efficacious

- serious adverse events are rare.

TVT utilizes a 5-mm trocar that is passed from the vagina through the retropubic space, exiting via small suprapubic incisions. A strip of permanent polypropylene mesh attached to these trocars is placed under the midportion of the urethra (FIGURE [“A”]).

We now have 11 years of follow-up data to support the use of the TVT midurethral sling for SUI.1

As TVT gained popularity, surgical equipment manufacturers developed various “kits,” so to speak, for placing a midurethral sling. Many have included innovations that have theoretical advantages over traditional TVT. Some place smaller, 3-mm trocars in a similar “bottom-up” fashion, as the TVT sling does; others utilize smaller trocars that are placed “top down” through the retropubic space into the vagina.

A later generation of slings uses the transobturator approach, to avoid blind passage of trocars through the retropubic space. These slings can be placed “in to out” or “out to in,” and rest in a slightly different orientation under the midurethra.

In an effort to make the procedure even more minimally invasive, some manufacturers now offer slings that are placed through one vaginal incision, thereby avoiding additional suprapubic or groin incisions. Other kits have made alterations to the polypropylene mesh by heat-sealing the material or applying a coating.

Such modifications haven’t always been improvements—some sling kits carried a higher incidence of mesh-related complications, and certain ones were removed from the market. And, although the number of commercially available midurethral sling kits has exploded, we’ve seen scant data published that compare the traditional TVT method with alternative approaches. Those alternatives may be considered midurethral slings, but we haven’t known whether minor variations in technique, or in the instrumentation, translate to improvements in long-term efficacy.

More readjustments for retention are needed after SPARC (vs. TVT)

Lord HE, Taylor JD, Finn JC, et al. A randomized controlled equivalence trial of short-term complications and efficacy of tension-free vaginal tape and suprapubic urethral support sling for treating stress incontinence. BJU Int. 2006;98:367–376.

This randomized, controlled trial compared TVT with SPARC to treat SUI. The study was designed as an equivalence trial: the investigators sought to determine if the “newer” intervention of the two (SPARC) is therapeutically equivalent to the existing intervention (TVT)—not whether one is superior. They therefore looked to see if patients who underwent TVT and those who underwent SPARC had the same rate (within a 5% margin) of bladder injury and other secondary outcomes.

Subjects were eligible to participate if they had SUI on the basis of urodynamic or clinical parameters. They were unaware of their assigned treatment, underwent TVT or SPARC, and were reevaluated 6 weeks postoperatively. Intraoperative, postoperative, and 6-week follow-up data were recorded by the study surgeon.

Three hundred and one patients were enrolled; 147 underwent TVT and 154 underwent SPARC. The groups were similar in regard to all baseline characteristics.

No significant difference was noted between the groups in the primary outcome, which was the rate of bladder perforation (TVT, 0.7%; SPARC, 1.9% [p=.62]). This effect remained after controlling for age, parity, prior urinary incontinence surgery, other concomitant surgery, and the surgeon’s level of experience. There were no intergroup differences in perioperative blood loss, urgency, or objective cure of SUI (defined as negative cough stress test) 6 weeks after surgery.

Subjects who underwent SPARC were more likely to experience urinary retention that required surgical readjustment of the sling (SPARC, 10 of 154; TVT, none [p=.002]). Although the objective cure rate was similar across groups, the subjective cure rate was significantly different (TVT, 87.1%; SPARC, 76.5% [p=.03]).

Regression analysis revealed that subjects who had prior surgery for urinary incontinence and those whose surgery was performed by a comparatively less experienced physician were more likely to report persistence of SUI symptoms.

This study reflects general clinical practice, in that it was conducted across a heterogeneous sample of subjects who had both primary and recurrent stress incontinence. Although the rate of bladder perforation was equivalent across groups, more patients who underwent SPARC required loosening of the sling postoperatively to relieve urinary retention.

These data suggest that the SPARC sling may be more difficult to adjust correctly even though it is designed with a tensioning suture. The difficulty may be a consequence of 1) smaller-caliber trocar tunnels or 2) the “top-down” approach less accurately locating the sling at the midportion of the urethra.

This study would have been more rigorous and the results, stronger, if postoperative assessment was made by a blinded examiner. An exceptional positive aspect of study design was that the investigators considered the surgeon’s level of experience—a variable that can certainly affect outcome.

Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:611–621.

This randomized, controlled trial compared the efficacy of TVT with the transobturator tape (TOT) technique. Like Lord and colleagues’ study just discussed, it was conducted as an equivalence trial—to determine whether TOT is equivalent to TVT.

The primary outcome was abnormal bladder function 12 months after surgery, defined as the presence of any of the following:

- incontinence symptoms

- positive cough stress test

- retreatment for SUI

- treatment for postoperative urinary retention.

Women who had urodynamic stress incontinence were recruited from three academic centers; excluded were women who had detrusor overactivity, postvoid residual volume >100 mL, prior sling surgery, or contraindications to a midurethral sling.

For the retropubic approach, TVT was used. For the transobturator approach, the Monarc Subfascial Hammock (American Medical Systems) was used. Here, the tape is placed in an “outside-in” fashion.

Subjects completed a baseline bladder diary and a series of validated questionnaires. Postoperatively, subjects were followed for 2 years. Follow-up data included validated questionnaires, bladder diary, pelvic organ prolapse quantification, cough stress test, and postvoid residual volume determination. It was not possible to blind subjects or surgeons, but all postoperative assessments and exams were performed by a blinded nurse.

The investigators sought to determine if TVT and TOT yielded an equivalent (within a 15% margin) rate of abnormal bladder function.

Eventually, 170 patients underwent randomization and surgery (88, TVT; 82, TOT). Baseline demographic, clinical, and incontinence severity data were similar across groups.

Bladder perforation was more common with TVT than with TOT (7% and 0, respectively [p=.02]). Abnormal bladder function was noted in 46.6% of TVT subjects and in 42.7% of TOT subjects, with a noninferiority test demonstrating equivalence (p=.006). One year after surgery, 79% of patients in the TVT group and 82% of patients in the TOT group reported that bladder symptoms were “much better” or “very much better” (p=.88). No significant difference was noted between groups in any of the questionnaire responses after surgery.

This study has many strengths, including rigorous assessments, use of a blinded nurse-examiner to collect postoperative data, and a battery of validated questionnaires used throughout the study. In addition, the primary outcome measure, abnormal bladder function, is defined by stringent criteria that combine subjective and objective components, efficacy, and adverse events.

It will be interesting to see if the efficacy of TOT is maintained over time. The authors of the article point out that several transobturator sling kits are available, utilizing various trocar shapes, different approaches (i.e., “in to out”), and different types of mesh; this may mean variable rates of complications and different degrees of efficacy from one kit to the next.

Also notable in this study is that subjects had relatively high Valsalva leak-point pressures (approaching 100 cm H2O) in both groups.

Which technique is best for SUI with intrinsic sphincter deficiency?

Jeon MJ, Jung HJ, Chung SM, et al. Comparison of the treatment outcome of pubovaginal sling, tension-free vaginal tape, and transobturator tape for stress urinary incontinence with intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:76.e1–76.e4.

This retrospective cohort study was designed to evaluate techniques for treating severe SUI. Researchers were mainly interested in patients who had intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), defined as a Valsalva leak-point pressure <60 cm H2O or maximal urethral closure pressure <20 cm H2O.

The pubovaginal (bladder neck) sling (PVS) has been considered the gold standard therapeutic option for patients who have ISD. Recently, however, data have shown satisfactory outcomes using TVT in this setting.2,3 The aim of this study, therefore, was to compare PVS, TVT, and TOT for treating SUI in patients who had ISD. (Note: The researchers used Uratape [Mentor-Purgès] for the transobturator sling.)

The study included 253 subjects who had ISD and who underwent surgical intervention (87, PVS; 94, TVT; 92, TOT); women who had detrusor overactivity and voiding dysfunction were excluded. Follow-up assessments were performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months and annually thereafter. Outcomes studied included complications and rates of cure; the latter was defined as 1) the absence of subjective complaints of leakage and 2) a negative cough stress test.

Median follow-up was 36, 24, and 12 months in the PVS, TVT, and TOT groups, respectively. All groups were similar in regard to baseline clinical and demographic characteristics. Bladder perforation was rare (PVS, 1; TVT and TOT, 0). No significant difference was noted across techniques in the rate of de novo urgency, voiding dysfunction, reoperation for urinary retention, and recurrent urinary tract infection.

Two years after surgery, the cure rate for the three procedures differed significantly: PVS and TVT, 87% each; TOT, 35% (p<.0001). A Cox proportional hazards regression model revealed that the risk of treatment failure with PVS was no different than it was for TVT. However, this model demonstrated that the risk of failure was 4.6 times higher for TOT compared with PVS (p<.0001).

This study is subject to the limitations of any retrospective study. It is unique, however, in that investigators focused on a more severe sample of subjects with ISD. In addition, the authors of the study used the appropriate statistical techniques to attempt to control for potential confounders.

Although the rate of cure was higher with TVT than with TOT, the rate of voiding dysfunction (i.e., the need for catheterization longer than 1 month after surgery) and de novo urgency was higher with TVT as well. This finding suggests that TVT provides more compressive force around the urethra than TOT does; on the other hand, it is possible instead that the difference arises in the method of tensioning of various types of sling.

Last, the study surgeon conducted the postoperative evaluations and was not blinded. This may have introduced bias into the assessments.

As more long-term data become available about different approaches to placing a midurethral sling, it’s likely that we will learn that not all techniques are equal. A customized approach—one that takes into account the individual patient’s clinical parameters—may be necessary to yield long-term efficacy with a sling.

Although, as the authors of this Update discuss, there are several surgical approaches to stress urinary incontinence (tension-free vaginal tape, suprapubic urethral support sling, transobturator tape, pubovaginal sling placed at the bladder neck), coding for the procedure is limited to a single Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code when surgery is performed via a vaginal approach. CPT code 57288 ( Sling operation for stress incontinence [e.g., fascia or synthetic] ) has been assigned 21.59 relative value units in 2008 and should be reported no matter what type of sling is placed or what method is used to place it.

Failed placement

On occasion, sling material erodes or creates other problems for the patient, such that it must be removed or revised. To report correction of this adverse outcome, bill with 57287 (Removal or revision of sling for stress incontinence [e.g., fascia or synthetic]). If revision must be performed within the global period for the original procedure by the surgeon who placed the sling, append modifier -78 (Unplanned return to the operating/procedure room by the same physician following initial procedure for a related procedure during the postoperative period) to the revision code.

Minimally invasive placement

If you perform a sling procedure laparoscopically, report 51992 (Laparoscopy, surgical; sling operation for stress incontinence [e.g., fascia or synthetic]) instead. No corresponding code exists for laparoscopic revision of a sling procedure; under CPT rules, your only course is to report 51999 (Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, bladder).—MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC-OBGYN, MA

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Over the past 10 years, the midurethral sling has replaced the Burch urethropexy as the most common surgical procedure for correcting stress urinary incontinence (SUI). In this “Update” on midurethral slings, we highlight three recently published studies that compare popular surgical approaches to SUI:

- the original tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) technique (FIGURE [“A”])

- the suprapubic urethral support sling (SPARC) (FIGURE [“B”])

- the transobturator tape (TOT) technique (FIGURE [“C”])

- the traditional pubovaginal sling (PVS), placed at the bladder neck (FIGURE [“D”]).

FIGURE [“A”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) technique

FIGURE [“B”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Suprapubic urethral support sling (SPARC)

FIGURE [“C”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Transobturator tape (TOT) technique

FIGURE [“D”] Four options for a midurethral sling to correct stress urinary incontinence: Pubovaginal sling (PVS)

We’ve had a decade-plus of experience with the sling

The midurethral sling, first introduced as the tension-free vaginal tape, or TVT (Gynecare), was quick to be adopted because:

- it offers a minimally invasive approach

- it is highly efficacious

- serious adverse events are rare.

TVT utilizes a 5-mm trocar that is passed from the vagina through the retropubic space, exiting via small suprapubic incisions. A strip of permanent polypropylene mesh attached to these trocars is placed under the midportion of the urethra (FIGURE [“A”]).

We now have 11 years of follow-up data to support the use of the TVT midurethral sling for SUI.1

As TVT gained popularity, surgical equipment manufacturers developed various “kits,” so to speak, for placing a midurethral sling. Many have included innovations that have theoretical advantages over traditional TVT. Some place smaller, 3-mm trocars in a similar “bottom-up” fashion, as the TVT sling does; others utilize smaller trocars that are placed “top down” through the retropubic space into the vagina.

A later generation of slings uses the transobturator approach, to avoid blind passage of trocars through the retropubic space. These slings can be placed “in to out” or “out to in,” and rest in a slightly different orientation under the midurethra.

In an effort to make the procedure even more minimally invasive, some manufacturers now offer slings that are placed through one vaginal incision, thereby avoiding additional suprapubic or groin incisions. Other kits have made alterations to the polypropylene mesh by heat-sealing the material or applying a coating.

Such modifications haven’t always been improvements—some sling kits carried a higher incidence of mesh-related complications, and certain ones were removed from the market. And, although the number of commercially available midurethral sling kits has exploded, we’ve seen scant data published that compare the traditional TVT method with alternative approaches. Those alternatives may be considered midurethral slings, but we haven’t known whether minor variations in technique, or in the instrumentation, translate to improvements in long-term efficacy.

More readjustments for retention are needed after SPARC (vs. TVT)

Lord HE, Taylor JD, Finn JC, et al. A randomized controlled equivalence trial of short-term complications and efficacy of tension-free vaginal tape and suprapubic urethral support sling for treating stress incontinence. BJU Int. 2006;98:367–376.

This randomized, controlled trial compared TVT with SPARC to treat SUI. The study was designed as an equivalence trial: the investigators sought to determine if the “newer” intervention of the two (SPARC) is therapeutically equivalent to the existing intervention (TVT)—not whether one is superior. They therefore looked to see if patients who underwent TVT and those who underwent SPARC had the same rate (within a 5% margin) of bladder injury and other secondary outcomes.

Subjects were eligible to participate if they had SUI on the basis of urodynamic or clinical parameters. They were unaware of their assigned treatment, underwent TVT or SPARC, and were reevaluated 6 weeks postoperatively. Intraoperative, postoperative, and 6-week follow-up data were recorded by the study surgeon.

Three hundred and one patients were enrolled; 147 underwent TVT and 154 underwent SPARC. The groups were similar in regard to all baseline characteristics.

No significant difference was noted between the groups in the primary outcome, which was the rate of bladder perforation (TVT, 0.7%; SPARC, 1.9% [p=.62]). This effect remained after controlling for age, parity, prior urinary incontinence surgery, other concomitant surgery, and the surgeon’s level of experience. There were no intergroup differences in perioperative blood loss, urgency, or objective cure of SUI (defined as negative cough stress test) 6 weeks after surgery.

Subjects who underwent SPARC were more likely to experience urinary retention that required surgical readjustment of the sling (SPARC, 10 of 154; TVT, none [p=.002]). Although the objective cure rate was similar across groups, the subjective cure rate was significantly different (TVT, 87.1%; SPARC, 76.5% [p=.03]).

Regression analysis revealed that subjects who had prior surgery for urinary incontinence and those whose surgery was performed by a comparatively less experienced physician were more likely to report persistence of SUI symptoms.

This study reflects general clinical practice, in that it was conducted across a heterogeneous sample of subjects who had both primary and recurrent stress incontinence. Although the rate of bladder perforation was equivalent across groups, more patients who underwent SPARC required loosening of the sling postoperatively to relieve urinary retention.

These data suggest that the SPARC sling may be more difficult to adjust correctly even though it is designed with a tensioning suture. The difficulty may be a consequence of 1) smaller-caliber trocar tunnels or 2) the “top-down” approach less accurately locating the sling at the midportion of the urethra.

This study would have been more rigorous and the results, stronger, if postoperative assessment was made by a blinded examiner. An exceptional positive aspect of study design was that the investigators considered the surgeon’s level of experience—a variable that can certainly affect outcome.

Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:611–621.

This randomized, controlled trial compared the efficacy of TVT with the transobturator tape (TOT) technique. Like Lord and colleagues’ study just discussed, it was conducted as an equivalence trial—to determine whether TOT is equivalent to TVT.

The primary outcome was abnormal bladder function 12 months after surgery, defined as the presence of any of the following:

- incontinence symptoms

- positive cough stress test

- retreatment for SUI

- treatment for postoperative urinary retention.

Women who had urodynamic stress incontinence were recruited from three academic centers; excluded were women who had detrusor overactivity, postvoid residual volume >100 mL, prior sling surgery, or contraindications to a midurethral sling.

For the retropubic approach, TVT was used. For the transobturator approach, the Monarc Subfascial Hammock (American Medical Systems) was used. Here, the tape is placed in an “outside-in” fashion.

Subjects completed a baseline bladder diary and a series of validated questionnaires. Postoperatively, subjects were followed for 2 years. Follow-up data included validated questionnaires, bladder diary, pelvic organ prolapse quantification, cough stress test, and postvoid residual volume determination. It was not possible to blind subjects or surgeons, but all postoperative assessments and exams were performed by a blinded nurse.

The investigators sought to determine if TVT and TOT yielded an equivalent (within a 15% margin) rate of abnormal bladder function.

Eventually, 170 patients underwent randomization and surgery (88, TVT; 82, TOT). Baseline demographic, clinical, and incontinence severity data were similar across groups.

Bladder perforation was more common with TVT than with TOT (7% and 0, respectively [p=.02]). Abnormal bladder function was noted in 46.6% of TVT subjects and in 42.7% of TOT subjects, with a noninferiority test demonstrating equivalence (p=.006). One year after surgery, 79% of patients in the TVT group and 82% of patients in the TOT group reported that bladder symptoms were “much better” or “very much better” (p=.88). No significant difference was noted between groups in any of the questionnaire responses after surgery.

This study has many strengths, including rigorous assessments, use of a blinded nurse-examiner to collect postoperative data, and a battery of validated questionnaires used throughout the study. In addition, the primary outcome measure, abnormal bladder function, is defined by stringent criteria that combine subjective and objective components, efficacy, and adverse events.

It will be interesting to see if the efficacy of TOT is maintained over time. The authors of the article point out that several transobturator sling kits are available, utilizing various trocar shapes, different approaches (i.e., “in to out”), and different types of mesh; this may mean variable rates of complications and different degrees of efficacy from one kit to the next.

Also notable in this study is that subjects had relatively high Valsalva leak-point pressures (approaching 100 cm H2O) in both groups.

Which technique is best for SUI with intrinsic sphincter deficiency?

Jeon MJ, Jung HJ, Chung SM, et al. Comparison of the treatment outcome of pubovaginal sling, tension-free vaginal tape, and transobturator tape for stress urinary incontinence with intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:76.e1–76.e4.

This retrospective cohort study was designed to evaluate techniques for treating severe SUI. Researchers were mainly interested in patients who had intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), defined as a Valsalva leak-point pressure <60 cm H2O or maximal urethral closure pressure <20 cm H2O.

The pubovaginal (bladder neck) sling (PVS) has been considered the gold standard therapeutic option for patients who have ISD. Recently, however, data have shown satisfactory outcomes using TVT in this setting.2,3 The aim of this study, therefore, was to compare PVS, TVT, and TOT for treating SUI in patients who had ISD. (Note: The researchers used Uratape [Mentor-Purgès] for the transobturator sling.)

The study included 253 subjects who had ISD and who underwent surgical intervention (87, PVS; 94, TVT; 92, TOT); women who had detrusor overactivity and voiding dysfunction were excluded. Follow-up assessments were performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months and annually thereafter. Outcomes studied included complications and rates of cure; the latter was defined as 1) the absence of subjective complaints of leakage and 2) a negative cough stress test.

Median follow-up was 36, 24, and 12 months in the PVS, TVT, and TOT groups, respectively. All groups were similar in regard to baseline clinical and demographic characteristics. Bladder perforation was rare (PVS, 1; TVT and TOT, 0). No significant difference was noted across techniques in the rate of de novo urgency, voiding dysfunction, reoperation for urinary retention, and recurrent urinary tract infection.

Two years after surgery, the cure rate for the three procedures differed significantly: PVS and TVT, 87% each; TOT, 35% (p<.0001). A Cox proportional hazards regression model revealed that the risk of treatment failure with PVS was no different than it was for TVT. However, this model demonstrated that the risk of failure was 4.6 times higher for TOT compared with PVS (p<.0001).

This study is subject to the limitations of any retrospective study. It is unique, however, in that investigators focused on a more severe sample of subjects with ISD. In addition, the authors of the study used the appropriate statistical techniques to attempt to control for potential confounders.

Although the rate of cure was higher with TVT than with TOT, the rate of voiding dysfunction (i.e., the need for catheterization longer than 1 month after surgery) and de novo urgency was higher with TVT as well. This finding suggests that TVT provides more compressive force around the urethra than TOT does; on the other hand, it is possible instead that the difference arises in the method of tensioning of various types of sling.

Last, the study surgeon conducted the postoperative evaluations and was not blinded. This may have introduced bias into the assessments.

As more long-term data become available about different approaches to placing a midurethral sling, it’s likely that we will learn that not all techniques are equal. A customized approach—one that takes into account the individual patient’s clinical parameters—may be necessary to yield long-term efficacy with a sling.

Although, as the authors of this Update discuss, there are several surgical approaches to stress urinary incontinence (tension-free vaginal tape, suprapubic urethral support sling, transobturator tape, pubovaginal sling placed at the bladder neck), coding for the procedure is limited to a single Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code when surgery is performed via a vaginal approach. CPT code 57288 ( Sling operation for stress incontinence [e.g., fascia or synthetic] ) has been assigned 21.59 relative value units in 2008 and should be reported no matter what type of sling is placed or what method is used to place it.

Failed placement

On occasion, sling material erodes or creates other problems for the patient, such that it must be removed or revised. To report correction of this adverse outcome, bill with 57287 (Removal or revision of sling for stress incontinence [e.g., fascia or synthetic]). If revision must be performed within the global period for the original procedure by the surgeon who placed the sling, append modifier -78 (Unplanned return to the operating/procedure room by the same physician following initial procedure for a related procedure during the postoperative period) to the revision code.

Minimally invasive placement

If you perform a sling procedure laparoscopically, report 51992 (Laparoscopy, surgical; sling operation for stress incontinence [e.g., fascia or synthetic]) instead. No corresponding code exists for laparoscopic revision of a sling procedure; under CPT rules, your only course is to report 51999 (Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, bladder).—MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC-OBGYN, MA

1. Nilsson CG, Palva K, Rezapour M, Falconer C. Eleven years prospective follow-up of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure for treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urygynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1043-1047.

2. Rezapour M, Falconer C, Ulmsten U. Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) in stress incontinent women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD)—a long-term follow-up. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(Suppl 2):S12-S14.

3. Meschia M, Pifarotti P, Buonaguidi A, Gattei U, Spennacchio M. Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women with low-pressure urethra. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;122:118-121.

1. Nilsson CG, Palva K, Rezapour M, Falconer C. Eleven years prospective follow-up of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure for treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urygynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1043-1047.

2. Rezapour M, Falconer C, Ulmsten U. Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) in stress incontinent women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD)—a long-term follow-up. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(Suppl 2):S12-S14.

3. Meschia M, Pifarotti P, Buonaguidi A, Gattei U, Spennacchio M. Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women with low-pressure urethra. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;122:118-121.

PELVIC SURGERY

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The use of transvaginal mesh—with or without trocar placement—is surrounded by controversy. A number of minimally invasive vaginal mesh kits are commercially available for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse, and new kits are entering the market rapidly. The challenge is determining whether these new techniques are as effective and safe as traditional prolapse repairs.

Although the use of permanent mesh to repair prolapse has been explored in retrospective and prospective studies, no rigorous controlled trials have compared these new procedures with abdominal sacrocolpopexy or uterosacral ligament suspension, for example. The current body of literature does suggest a high rate of recurrent prolapse after traditional anterior or posterior colporrhaphy, and the use of allograft material has not been shown to improve outcomes. Surgeons are now turning their attention to permanent polypropylene mesh as a possible alternative. In addition, repair of the vaginal apex at the time of anterior and posterior vaginal wall repair is being explored as a way to increase durability of the repair. The new trocar-delivered mesh kits address this issue by suspending the vaginal vault while providing support to the vaginal walls.

This article highlights three recent studies that focus on a new trocar-delivered, protected, low-weight polypropylene mesh (Ugytex, distributed by Bard as Pelvitex) and three trocar-delivered mesh kits (Prolift, Apogee, and Perigee).

One-year outcomes encouraging for low-weight polypropylene mesh

De Tayrac R, Devoldere G, Renaudie J, Villard P, Guilbaud O, Eglin G. Prolapse repair by vaginal route using a new protected low-weight polypropylene mesh: 1-year functional and anatomical outcome in a prospective multicentre study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:251–256.

This study evaluated functional and anatomic outcomes after placement for prolapse repair of low-weight polypropylene mesh protected by absorbable hydrophilic film. The film, a combination of atelocollagen, polyethylene glycol, and glycerol, is designed to protect pelvic organs from acute inflammation during healing. In a separate investigation of unprotected, heavyweight polypropylene mesh in prolapse repair, the anatomic success rate ranged from 75% to 100%, but the rate of mesh erosion (13%) and dyspareunia (69%) seemed unacceptably high.1

Rigorous preoperative assessment

In this trial, 230 women with symptomatic vaginal wall prolapse were recruited at 13 centers in a consecutive fashion. At enrollment, all patients were measured using the pelvic organ prolapse quantitative staging system (POP-Q). They also completed the validated Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. The presence and severity of dyspareunia were also recorded, as well as the Urinary Dysfunction Measurement Scale. All participants had prolapse equal to or exceeding stage II.

Surgeons used trocars to percutaneously place a low-weight (38 g/m2) and highly porous polypropylene monofilament mesh (Ugytex/Pelvitex) for vaginal repair and performed any concomitant procedures. Perioperative and postoperative complications were recorded. Patients were evaluated at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year. The first 143 patients with at least 10 months of follow-up were analyzed, with a mean follow-up of 13±2 months (range: 10–19). Anatomic cure was defined as no prolapse greater than or equal to stage II.

Patient satisfaction was high

The anatomic cure rate was 92.3%, with a 6.8% recurrence of anterior vaginal wall prolapse and 2.6% recurrence of posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Only one patient with recurrence was symptomatic.

Six of 143 patients (4.2%) sustained an intraoperative complication: three bladder injuries, one rectal injury, one uterine artery hemorrhage (during hysterectomy), and one vaginal sulcus perforation (during transobturator tape placement). The most significant postoperative complication related to the vaginal mesh kit was vaginal hematoma; one of the two cases required reoperation and partial removal of the mesh.

Nine patients developed mesh erosion in the first 3 months, for an erosion rate of 6.3%. Six required partial excision of the mesh. Overall, symptoms and quality of life improved significantly, with an overall satisfaction rate at follow-up of 96.5%. No significant difference was noted between pre- and postoperative rates of dyspareunia.

Further evaluation is warranted

The authors are already conducting a randomized trial to compare anterior vaginal wall repair using this low-weight polypropylene mesh with traditional anterior colporrhaphy to confirm and explore these results.

Note: Bard now offers a kit called Avaulta Plus that uses the same mesh material with a trocar delivery system, previously lacking (although investigators used trocars in this study).

Perioperative complications were uncommon with Prolift system

Altman D, Falconer C. Perioperative morbidity using transvaginal mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:303–308.

This study explored the frequency and characteristics of perioperative complications associated with the use of Prolift, a transvaginal mesh system for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse (FIGURE). Twenty-five centers participated by registering a standardized safety protocol form for 248 women who underwent surgery using the system over a 6-month period. The form included information about perioperative complications, adverse intraoperative events, and the associated hospital stay, as well as obstetric and gynecologic medical history and previous pelvic surgery.

Pelvic organ perforation (lower urinary tract or anorectal injury) and blood loss greater than 1,000 mL were recorded as major complications, and any other adverse events related to the hospital stay were documented as minor complications. Most of the cohort had already undergone prolapse repair, and prolapse had recurred in the same vaginal compartment.

One author was an educational adviser for Gynecare Sweden AB, and the other an adviser for Johnson & Johnson. Although the study was funded entirely by university-administered research funds, pretrial scientific meetings were paid for by Gynecare Sweden AB.

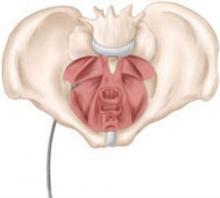

FIGURE: Mesh support of pelvic organs

Prolift mesh in final position, with extension arms passed through the sacrospinous ligaments and the obturator foramen bilaterally.

4.4% rate of serious complications

Serious complications occurred in 4.4% (11 of 248) of cases (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5–7.8). The predominant complication was visceral injury, which included bladder, urethral, and rectal perforation. One patient had blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL.

Minor complications occurred in 44 patients (18%). The most common minor complication was urinary tract infection. Adverse events included urinary retention requiring catheterization, anemia, transfusion, fever, groin and buttock pain, and vaginal hematoma, among others.

Concurrent pelvic floor surgery increased the risk for minor complications (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.1–6.9). Concurrent procedures included vaginal hysterectomy, sling procedure with tension-free vaginal tape or transobturator tension-free tape, sacrospinal fixation, repair of vaginal enterocele, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. This risk analysis identified no other predictors of outcome.

Posterior/apical repair

- Adequately infiltrate the vaginal epithelium with diluted epinephrine solution, especially toward the lateral apices, to facilitate hemostasis and dissection

- Be thorough in lateral dissection toward the ischial spine and stay in the proper surgical plane to create a thick vaginal epithelial flap

- Palpate the ischial spine, with the preoperatively packed rectum retracted medially

- During passage of the trocar, place an index finger along the vaginal dissection to palpate the trocar in the ischiorectal fossa and deep to the levator ani muscles until the tip is palpated at the level of the ischial spine

- Pass the trocar through the arcus tendineus/levator fascia at the level of the ischial spine, as shown below:

- Do not apply excess tension to the straps of the graft material

- Do not trim the vaginal epithelium

Anterior wall (obturator foramen trocar passage)

- Same key points as posterior wall technique, but in anterior repair, there are two passes through the obturator foramen

- The first trocar is inserted into the inferior obturator foramen, rotated, and guided with the surgeon’s finger inserted into and held in the vaginal dissection, as shown below:

- The superior passage exits close to the bladder neck, and the inferior passage approximates the ischial spine. Penetrate along the arcus tendineus approximately 1 cm from the ischial spine

Caution! Keep summary points in context

These key points are not intended as formal medical training, but as general information only. Continued research into these techniques is needed to assess long-term outcomes.

Short-term outcomes data only

Because this study focused on immediate complications, no long-term data on such complications as persistent pain, mesh erosion, or infection were collected.

All surgeons underwent hands-on training with the transvaginal repair system before patients were enrolled in the study. Nevertheless, the authors observe that many repair procedures were performed at the beginning of the physicians’ learning curve, with a higher number of complications than would be expected from more experienced surgeons.

The data may also have been affected by selection bias (ie, toward more complicated cases), given that most patients had already undergone prolapse repair.

Two systems yield excellent short-term results in women with recurrent prolapse

Gauruder-Burmester A, Koutouzidou P, Rohne J, Gronewold M, Tunn R. Follow-up after polypropylene mesh repair of anterior and posterior compartments in patients with recurrent prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1059–1064.

This retrospective study involved women who had already undergone one or more prolapse repairs. These patients then underwent reoperation with mesh-reinforced repair. The authors hypothesized that recurrent prolapse represents poor tissue quality, necessitating the use of mesh in subsequent repairs. Both pre- and postoperative symptoms and functional changes were analyzed, with a special focus on mesh erosion and sexual function.

Details of the study

Of 145 women who underwent repair with the Apogee (apical posterior) or Perigee (anterior wall) system during a 1-year period, 120 were included in the analysis. The other 25 patients were excluded because they did not return for follow-up, were missing urodynamic data, or had inaccurate POP-Q staging. All patients had recurrent stage III posterior or anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Forty percent of patients had an apical posterior repair, and 60% had anterior wall repair. None had both procedures performed simultaneously.

All patients had undergone hysterectomy and received vaginal estrogen before and after surgery. Urinary incontinence was treated in a two-step fashion; that is, it was not addressed until 3 months after repair of the prolapse. Routine follow-up occurred at 1 month and 1 year after surgery.

One-year cure rate was 93%

No perioperative or intraoperative complications occurred, and mean operative time was 35±4.5 minutes. Mesh erosion occurred in four patients (3%) and involved anterior mesh placement only. No mesh infections were noted.

At 1 year, 93% of women were anatomically cured of prolapse (ie, they had less than stage II prolapse). Prolapse recurred in eight women; all cases involved the anterior compartment.

No dyspareunia was associated with the repair. In fact, prolapse-associated dyspareunia resolved in all 15 women who reported this symptom before surgery. In addition, questionnaires about quality of life and satisfaction revealed significant improvement after mesh placement (P=.023).

The authors attribute the positive results to the fact that both surgeons involved in the study used the technique on 15 patients before operating on study participants, minimizing the effect of the learning curve. The authors were also careful about patient selection.

Results merit cautious optimism

The authors propose that the low erosion rate and lack of new-onset dyspareunia after surgery may be misleading because long-term results have not yet been obtained. We also speculate that precise dissection in the proper surgical plane likely minimized early erosions.

Reference

1. Milani R, Salvatore S, Soligo M, Pifarotti P, Meschia M, Cortese M. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;111:1-5.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The use of transvaginal mesh—with or without trocar placement—is surrounded by controversy. A number of minimally invasive vaginal mesh kits are commercially available for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse, and new kits are entering the market rapidly. The challenge is determining whether these new techniques are as effective and safe as traditional prolapse repairs.

Although the use of permanent mesh to repair prolapse has been explored in retrospective and prospective studies, no rigorous controlled trials have compared these new procedures with abdominal sacrocolpopexy or uterosacral ligament suspension, for example. The current body of literature does suggest a high rate of recurrent prolapse after traditional anterior or posterior colporrhaphy, and the use of allograft material has not been shown to improve outcomes. Surgeons are now turning their attention to permanent polypropylene mesh as a possible alternative. In addition, repair of the vaginal apex at the time of anterior and posterior vaginal wall repair is being explored as a way to increase durability of the repair. The new trocar-delivered mesh kits address this issue by suspending the vaginal vault while providing support to the vaginal walls.

This article highlights three recent studies that focus on a new trocar-delivered, protected, low-weight polypropylene mesh (Ugytex, distributed by Bard as Pelvitex) and three trocar-delivered mesh kits (Prolift, Apogee, and Perigee).

One-year outcomes encouraging for low-weight polypropylene mesh

De Tayrac R, Devoldere G, Renaudie J, Villard P, Guilbaud O, Eglin G. Prolapse repair by vaginal route using a new protected low-weight polypropylene mesh: 1-year functional and anatomical outcome in a prospective multicentre study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:251–256.

This study evaluated functional and anatomic outcomes after placement for prolapse repair of low-weight polypropylene mesh protected by absorbable hydrophilic film. The film, a combination of atelocollagen, polyethylene glycol, and glycerol, is designed to protect pelvic organs from acute inflammation during healing. In a separate investigation of unprotected, heavyweight polypropylene mesh in prolapse repair, the anatomic success rate ranged from 75% to 100%, but the rate of mesh erosion (13%) and dyspareunia (69%) seemed unacceptably high.1

Rigorous preoperative assessment

In this trial, 230 women with symptomatic vaginal wall prolapse were recruited at 13 centers in a consecutive fashion. At enrollment, all patients were measured using the pelvic organ prolapse quantitative staging system (POP-Q). They also completed the validated Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. The presence and severity of dyspareunia were also recorded, as well as the Urinary Dysfunction Measurement Scale. All participants had prolapse equal to or exceeding stage II.

Surgeons used trocars to percutaneously place a low-weight (38 g/m2) and highly porous polypropylene monofilament mesh (Ugytex/Pelvitex) for vaginal repair and performed any concomitant procedures. Perioperative and postoperative complications were recorded. Patients were evaluated at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year. The first 143 patients with at least 10 months of follow-up were analyzed, with a mean follow-up of 13±2 months (range: 10–19). Anatomic cure was defined as no prolapse greater than or equal to stage II.

Patient satisfaction was high

The anatomic cure rate was 92.3%, with a 6.8% recurrence of anterior vaginal wall prolapse and 2.6% recurrence of posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Only one patient with recurrence was symptomatic.

Six of 143 patients (4.2%) sustained an intraoperative complication: three bladder injuries, one rectal injury, one uterine artery hemorrhage (during hysterectomy), and one vaginal sulcus perforation (during transobturator tape placement). The most significant postoperative complication related to the vaginal mesh kit was vaginal hematoma; one of the two cases required reoperation and partial removal of the mesh.

Nine patients developed mesh erosion in the first 3 months, for an erosion rate of 6.3%. Six required partial excision of the mesh. Overall, symptoms and quality of life improved significantly, with an overall satisfaction rate at follow-up of 96.5%. No significant difference was noted between pre- and postoperative rates of dyspareunia.

Further evaluation is warranted

The authors are already conducting a randomized trial to compare anterior vaginal wall repair using this low-weight polypropylene mesh with traditional anterior colporrhaphy to confirm and explore these results.

Note: Bard now offers a kit called Avaulta Plus that uses the same mesh material with a trocar delivery system, previously lacking (although investigators used trocars in this study).

Perioperative complications were uncommon with Prolift system

Altman D, Falconer C. Perioperative morbidity using transvaginal mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:303–308.

This study explored the frequency and characteristics of perioperative complications associated with the use of Prolift, a transvaginal mesh system for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse (FIGURE). Twenty-five centers participated by registering a standardized safety protocol form for 248 women who underwent surgery using the system over a 6-month period. The form included information about perioperative complications, adverse intraoperative events, and the associated hospital stay, as well as obstetric and gynecologic medical history and previous pelvic surgery.

Pelvic organ perforation (lower urinary tract or anorectal injury) and blood loss greater than 1,000 mL were recorded as major complications, and any other adverse events related to the hospital stay were documented as minor complications. Most of the cohort had already undergone prolapse repair, and prolapse had recurred in the same vaginal compartment.

One author was an educational adviser for Gynecare Sweden AB, and the other an adviser for Johnson & Johnson. Although the study was funded entirely by university-administered research funds, pretrial scientific meetings were paid for by Gynecare Sweden AB.

FIGURE: Mesh support of pelvic organs

Prolift mesh in final position, with extension arms passed through the sacrospinous ligaments and the obturator foramen bilaterally.

4.4% rate of serious complications

Serious complications occurred in 4.4% (11 of 248) of cases (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5–7.8). The predominant complication was visceral injury, which included bladder, urethral, and rectal perforation. One patient had blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL.

Minor complications occurred in 44 patients (18%). The most common minor complication was urinary tract infection. Adverse events included urinary retention requiring catheterization, anemia, transfusion, fever, groin and buttock pain, and vaginal hematoma, among others.

Concurrent pelvic floor surgery increased the risk for minor complications (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.1–6.9). Concurrent procedures included vaginal hysterectomy, sling procedure with tension-free vaginal tape or transobturator tension-free tape, sacrospinal fixation, repair of vaginal enterocele, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. This risk analysis identified no other predictors of outcome.

Posterior/apical repair

- Adequately infiltrate the vaginal epithelium with diluted epinephrine solution, especially toward the lateral apices, to facilitate hemostasis and dissection

- Be thorough in lateral dissection toward the ischial spine and stay in the proper surgical plane to create a thick vaginal epithelial flap

- Palpate the ischial spine, with the preoperatively packed rectum retracted medially

- During passage of the trocar, place an index finger along the vaginal dissection to palpate the trocar in the ischiorectal fossa and deep to the levator ani muscles until the tip is palpated at the level of the ischial spine

- Pass the trocar through the arcus tendineus/levator fascia at the level of the ischial spine, as shown below:

- Do not apply excess tension to the straps of the graft material

- Do not trim the vaginal epithelium

Anterior wall (obturator foramen trocar passage)

- Same key points as posterior wall technique, but in anterior repair, there are two passes through the obturator foramen

- The first trocar is inserted into the inferior obturator foramen, rotated, and guided with the surgeon’s finger inserted into and held in the vaginal dissection, as shown below:

- The superior passage exits close to the bladder neck, and the inferior passage approximates the ischial spine. Penetrate along the arcus tendineus approximately 1 cm from the ischial spine

Caution! Keep summary points in context

These key points are not intended as formal medical training, but as general information only. Continued research into these techniques is needed to assess long-term outcomes.

Short-term outcomes data only

Because this study focused on immediate complications, no long-term data on such complications as persistent pain, mesh erosion, or infection were collected.

All surgeons underwent hands-on training with the transvaginal repair system before patients were enrolled in the study. Nevertheless, the authors observe that many repair procedures were performed at the beginning of the physicians’ learning curve, with a higher number of complications than would be expected from more experienced surgeons.

The data may also have been affected by selection bias (ie, toward more complicated cases), given that most patients had already undergone prolapse repair.

Two systems yield excellent short-term results in women with recurrent prolapse

Gauruder-Burmester A, Koutouzidou P, Rohne J, Gronewold M, Tunn R. Follow-up after polypropylene mesh repair of anterior and posterior compartments in patients with recurrent prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1059–1064.

This retrospective study involved women who had already undergone one or more prolapse repairs. These patients then underwent reoperation with mesh-reinforced repair. The authors hypothesized that recurrent prolapse represents poor tissue quality, necessitating the use of mesh in subsequent repairs. Both pre- and postoperative symptoms and functional changes were analyzed, with a special focus on mesh erosion and sexual function.

Details of the study

Of 145 women who underwent repair with the Apogee (apical posterior) or Perigee (anterior wall) system during a 1-year period, 120 were included in the analysis. The other 25 patients were excluded because they did not return for follow-up, were missing urodynamic data, or had inaccurate POP-Q staging. All patients had recurrent stage III posterior or anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Forty percent of patients had an apical posterior repair, and 60% had anterior wall repair. None had both procedures performed simultaneously.

All patients had undergone hysterectomy and received vaginal estrogen before and after surgery. Urinary incontinence was treated in a two-step fashion; that is, it was not addressed until 3 months after repair of the prolapse. Routine follow-up occurred at 1 month and 1 year after surgery.

One-year cure rate was 93%

No perioperative or intraoperative complications occurred, and mean operative time was 35±4.5 minutes. Mesh erosion occurred in four patients (3%) and involved anterior mesh placement only. No mesh infections were noted.

At 1 year, 93% of women were anatomically cured of prolapse (ie, they had less than stage II prolapse). Prolapse recurred in eight women; all cases involved the anterior compartment.

No dyspareunia was associated with the repair. In fact, prolapse-associated dyspareunia resolved in all 15 women who reported this symptom before surgery. In addition, questionnaires about quality of life and satisfaction revealed significant improvement after mesh placement (P=.023).

The authors attribute the positive results to the fact that both surgeons involved in the study used the technique on 15 patients before operating on study participants, minimizing the effect of the learning curve. The authors were also careful about patient selection.

Results merit cautious optimism

The authors propose that the low erosion rate and lack of new-onset dyspareunia after surgery may be misleading because long-term results have not yet been obtained. We also speculate that precise dissection in the proper surgical plane likely minimized early erosions.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The use of transvaginal mesh—with or without trocar placement—is surrounded by controversy. A number of minimally invasive vaginal mesh kits are commercially available for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse, and new kits are entering the market rapidly. The challenge is determining whether these new techniques are as effective and safe as traditional prolapse repairs.

Although the use of permanent mesh to repair prolapse has been explored in retrospective and prospective studies, no rigorous controlled trials have compared these new procedures with abdominal sacrocolpopexy or uterosacral ligament suspension, for example. The current body of literature does suggest a high rate of recurrent prolapse after traditional anterior or posterior colporrhaphy, and the use of allograft material has not been shown to improve outcomes. Surgeons are now turning their attention to permanent polypropylene mesh as a possible alternative. In addition, repair of the vaginal apex at the time of anterior and posterior vaginal wall repair is being explored as a way to increase durability of the repair. The new trocar-delivered mesh kits address this issue by suspending the vaginal vault while providing support to the vaginal walls.

This article highlights three recent studies that focus on a new trocar-delivered, protected, low-weight polypropylene mesh (Ugytex, distributed by Bard as Pelvitex) and three trocar-delivered mesh kits (Prolift, Apogee, and Perigee).

One-year outcomes encouraging for low-weight polypropylene mesh

De Tayrac R, Devoldere G, Renaudie J, Villard P, Guilbaud O, Eglin G. Prolapse repair by vaginal route using a new protected low-weight polypropylene mesh: 1-year functional and anatomical outcome in a prospective multicentre study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:251–256.

This study evaluated functional and anatomic outcomes after placement for prolapse repair of low-weight polypropylene mesh protected by absorbable hydrophilic film. The film, a combination of atelocollagen, polyethylene glycol, and glycerol, is designed to protect pelvic organs from acute inflammation during healing. In a separate investigation of unprotected, heavyweight polypropylene mesh in prolapse repair, the anatomic success rate ranged from 75% to 100%, but the rate of mesh erosion (13%) and dyspareunia (69%) seemed unacceptably high.1

Rigorous preoperative assessment

In this trial, 230 women with symptomatic vaginal wall prolapse were recruited at 13 centers in a consecutive fashion. At enrollment, all patients were measured using the pelvic organ prolapse quantitative staging system (POP-Q). They also completed the validated Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. The presence and severity of dyspareunia were also recorded, as well as the Urinary Dysfunction Measurement Scale. All participants had prolapse equal to or exceeding stage II.

Surgeons used trocars to percutaneously place a low-weight (38 g/m2) and highly porous polypropylene monofilament mesh (Ugytex/Pelvitex) for vaginal repair and performed any concomitant procedures. Perioperative and postoperative complications were recorded. Patients were evaluated at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year. The first 143 patients with at least 10 months of follow-up were analyzed, with a mean follow-up of 13±2 months (range: 10–19). Anatomic cure was defined as no prolapse greater than or equal to stage II.

Patient satisfaction was high

The anatomic cure rate was 92.3%, with a 6.8% recurrence of anterior vaginal wall prolapse and 2.6% recurrence of posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Only one patient with recurrence was symptomatic.

Six of 143 patients (4.2%) sustained an intraoperative complication: three bladder injuries, one rectal injury, one uterine artery hemorrhage (during hysterectomy), and one vaginal sulcus perforation (during transobturator tape placement). The most significant postoperative complication related to the vaginal mesh kit was vaginal hematoma; one of the two cases required reoperation and partial removal of the mesh.

Nine patients developed mesh erosion in the first 3 months, for an erosion rate of 6.3%. Six required partial excision of the mesh. Overall, symptoms and quality of life improved significantly, with an overall satisfaction rate at follow-up of 96.5%. No significant difference was noted between pre- and postoperative rates of dyspareunia.

Further evaluation is warranted

The authors are already conducting a randomized trial to compare anterior vaginal wall repair using this low-weight polypropylene mesh with traditional anterior colporrhaphy to confirm and explore these results.

Note: Bard now offers a kit called Avaulta Plus that uses the same mesh material with a trocar delivery system, previously lacking (although investigators used trocars in this study).

Perioperative complications were uncommon with Prolift system

Altman D, Falconer C. Perioperative morbidity using transvaginal mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:303–308.

This study explored the frequency and characteristics of perioperative complications associated with the use of Prolift, a transvaginal mesh system for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse (FIGURE). Twenty-five centers participated by registering a standardized safety protocol form for 248 women who underwent surgery using the system over a 6-month period. The form included information about perioperative complications, adverse intraoperative events, and the associated hospital stay, as well as obstetric and gynecologic medical history and previous pelvic surgery.