User login

New Alzheimer’s disease guidelines: Implications for clinicians

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

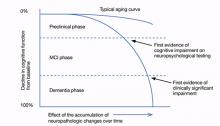

In 2011, a workgroup of experts from the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute on Aging published new criteria and guidelines for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the first new AD guidelines since 1984.1-4 These criteria reflect data that suggest AD is not synonymous with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) but is a disease that slowly develops over many years as a result of accumulated neuropathologic changes, with dementia representing only the final phase of the disease (Figure).1-4

Figure: Cognitive decline in AD over time

AD: Alzheimer’s disease; MCI: mild cognitive impairment

Source: Adapted from reference 2

This article highlights the similarities and differences of the 1984 and 2011 AD diagnosis guidelines. We also discuss the new guidelines’ limitations and clinical implications.

The 1984 AD criteria

Both the 1984 AD criteria5 and DSM-IV-TR criteria6 rely on the concept that AD is a clinical diagnosis made after a patient develops dementia. That is, diagnosis rests on the physician’s clinical judgment about the etiology of the patient’s symptoms, taking into account reports from the patient, family, and friends, as well as results of neurocognitive testing and mental status evaluation. The 1984 criteria were developed with the expectation that if a patient who met clinical criteria for AD were to undergo an autopsy, he or she likely would have evidence of AD pathology as the underlying etiology. These criteria were developed before researchers discovered that in AD, pathologic changes occur over many years and clinical dementia is the end product of accumulated pathology. The 1984 criteria did not address important phases that precede clinical dementia—such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). See the Table for a summary of the 1984 AD criteria.

Table

The 1984 NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for clinical diagnosis of AD

|

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease; NINCDS-ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association Source: McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939-944 |

The 2011 AD criteria

The new AD criteria differ from the 1984 criteria in 2 major ways:

- expansion of AD into 3 phases, only 1 of which is characterized by dementia

- incorporation of biomarkers to provide information regarding pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease state (Table 1).1-5

The 3 phases. The 2011 criteria expand the definition of AD to include an asymptomatic, preclinical phase; a symptomatic, pre-dementia phase; and a dementia phase. In the initial phase, neuronal toxins such as beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and elevated tau first become detectable. Patients in this phase are asymptomatic or have subtle symptoms. This phase should be viewed as part of a continuum and includes patients who may, for instance, develop Aβ plaques but do not progress to further neurodegeneration.2 The diagnostic criteria of this phase are intended for research purposes only.1,2

Patients in the symptomatic, pre-dementia phase—also known as the MCI phase—exhibit mild decline in memory, attention, and thinking. Although this decline is more than what is expected for the patient’s age and education, it does not compromise everyday activity and functioning.

A patient who develops cognitive or behavioral problems that interfere with his or her ability to function at work or in everyday activities has entered the dementia phase. Similar to the 1984 guidelines, the 2011 criteria classify patients into probable and possible AD dementia. All patients who would have satisfied criteria for probable AD under the 1984 guidelines will satisfy criteria for probable AD dementia under the 2011 criteria.4 The same is not true for possible AD dementia. The 2011 criteria include 2 other major categories for patients with AD dementia: probable and possible AD dementia with evidence of the AD pathophysiological process. These categories are intended for research purposes only, whereas the criteria for the MCI and dementia phases are intended to guide diagnosis in the clinical setting.

By incorporating phases of AD that precede dementia into the disease spectrum, the new guidelines are designed to move clinicians toward earlier diagnosis and treatment.1-3 Similar to how early, pre-symptomatic detection and treatment of conditions such as diabetes and cancer can reduce mortality, improving diagnosis of AD in its early phases may allow clinicians to better test potential therapies and eventually use them to treat at-risk individuals.2,3 Most pharmacotherapies for AD are FDA-approved only for patients diagnosed with clinical dementia. Furthermore, current pharmacotherapies do not alter the course of AD; they have a modest effect in slowing cognitive and functional decline.7,8 If patients in the earlier phases of AD could be recruited for research studies, we may be able to develop new treatments to stop or reverse AD pathology and its clinical manifestations.

Biomarkers. The new criteria incorporate biomarkers to provide information about pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease process. These criteria define biomarkers as physiologic, biochemical, or anatomic parameters that can be measured in vivo and reflect specific features of disease-related pathophysiologic processes.1 Presently, there are no cutoff values to demarcate “normal” levels from “abnormal,” and biomarkers are proposed primarily as research tools because they have not been studied adequately in community settings and laboratory techniques to measure biomarkers have not been standardized.1-4,9

The 5 biomarkers incorporated into the new criteria are divided into 2 categories: biomarkers of Aβ accumulation and those of neuronal degeneration or injury (Table 2).1-4 In the initial, preclinical phase, biomarkers are used to detect changes in the brain—such as amyloid accumulation and nerve cell degeneration—that may already be in process in an individual whose clinical symptoms are subtle or not yet evident.1,2 In this phase, progressive evidence of biomarkers, such as both Aβ accumulation and neuronal injury rather than Aβ accumulation alone, may increase the probability that a patient will decline quickly into the MCI phase.2 Biomarkers of neuronal degeneration or injury especially correlate with the likelihood that the disease will progress to clinical dementia.1 Subtle cognitive symptoms in the preclinical phase also might predict rapid decline into MCI.2

In the MCI and dementia phases, biomarkers are used to determine the level of certainty that AD is responsible for the patient’s symptoms.1,3,4 For example, a patient could meet criteria for a non-AD dementia such as dementia with Lewy bodies, but also meet pathologic criteria for AD on autopsy.3 The diagnostic category of possible AD dementia with evidence of the AD pathophysiologic process is intended for this type of scenario.4 For the MCI phase, the criteria propose levels of certainty that a patient’s MCI syndrome is caused by AD, ranging from MCI due to AD-high likelihood to MCI-unlikely due to AD.3

Research has demonstrated that a patient’s clinical picture doesn’t necessarily reflect the extent of the underlying pathology. For example, a patient could have extensive AD pathology, such as diffuse amyloid plaques, without any obvious clinical symptoms.3 Conversely, although both Aβ deposition and elevated tau are hallmarks of AD, variations in these proteins can be seen in neuropsychiatric disorders other than AD.10 That said, it appears that worsening of clinical symptoms often parallels worsening of neurodegenerative biomarkers.1

Under the 2011 guidelines, biomarkers would not be used to diagnose or exclude AD or MCI, but instead would help improve diagnostic accuracy in individuals with cognitive decline.1,3,4 In other words, AD remains a clinical diagnosis, but these biomarkers could raise or lower the positive predictive value of a clinician’s judgment about the etiology of a patient’s symptoms.

See the Box for a description of the potential risks and benefits of using the new diagnostic criteria.

Table 1

Comparing the 1984 and 2011 AD criteria

| 1984 criteria | 2011 criteria |

|---|---|

| AD is a clinical diagnosis | AD remains a clinical diagnosis but biomarkers serve to improve the accuracy of diagnosis of the disease |

| There is only 1 phase of AD—dementia. | AD is expanded into 3 phases: an asymptomatic, preclinical phase; a symptomatic, pre-dementia phase; and a dementia phase |

| A patient who meets the clinical criteria for AD would be expected to have AD pathology as the underlying etiology were he/she to undergo a brain autopsy | Presently, biomarkers are proposed as research tools only and are not intended to be applied in the clinical setting. However, eventually clinicians will be able to diagnose AD in all 3 phases, as biomarker testing becomes standardized and reliable enough to be accurately applied in clinical settings |

| Little consideration is given to specific neuropathologic changes underlying the disease process | Biomarkers provide information regarding the pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease state |

| Little consideration is given to the idea that pathologic changes occur over many years | Inherent in dividing AD into 3 phases is the concept that AD develops slowly over many years and has a long prodromal phase that is clinically silent |

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease Source: References 1-5 | |

Table 2

5 biomarkers incorporated into the 2011 AD criteria

| Category | Biomarkers |

|---|---|

| Biomarkers of Aβ accumulation | Abnormal tracer retention on amyloid PET imaging |

| Low CSF Aβ42 | |

| Biomarkers of neuronal degeneration or injury | Elevated CSF tau (total and phosphorylated tau) |

| Decreased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on PET | |

| Atrophy on structural magnetic resonance imaging | |

| Aβ: beta-amyloid; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; PET: positron emission tomography Source: References 1-4 | |

The earlier an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis is made, the less certain it is AD.a Biomarkers typically found in individuals with AD also can be found in patients with dementia not caused by AD, such as vascular dementia, as well as in individuals who may never develop dementia.b Additionally, there is no certainty that a patient in an early phase of AD will develop clinical dementia. Falsely diagnosing a patient with AD may lead the individual and their family to feel helpless, hopeless, depressed, anxious, or ashamed and to spend money and other resources preparing for a prognosis that may never come to fruition. Clinicians may feel compelled to assess for biomarkers using expensive, invasive tests that are not yet standardized in an attempt to support the AD diagnosis.

Early diagnosis of AD has many benefits that should not be overlooked, however. It provides patients and their families an opportunity to become familiar with the disease course, which may help some patients cope with the diagnosis. Patients diagnosed in the early stages would be able to make important decisions regarding health care, social, and financial planning before they develop pathology that limits their executive planning abilities or become functionally impaired.

Diagnosing an illness when there are no disease-modifying therapies available is not futile. Some patients with newly diagnosed AD in the pre-dementia phases may want to participate in clinical research trials to help develop therapies for AD. Some data suggest that AD treatment appears to provide the greatest benefit when initiated early in the disease course and maintained over a long duration.c Eventually, we may be able to tailor specific AD treatments in different phases of the disease. For instance, we may discover treatments for patients who show evidence of beta-amyloid plaques but not neuronal injury, or vice versa. Patients also may benefit from education on nonpharmacologic treatments, including reducing vascular risk factors to help improve brain aging,d reducing stress, and learning cognitive strategies such as using mnemonics to aid memory.

In many clinical settings, patients are being clinically diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Research indicates that patients with MCI are at near-term risk of developing dementia, particularly dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.d,e Presently, no definite transition points demarcate MCI from dementia; this progression is based upon clinical judgment.

In the last decade, researchers have begun to describe a syndrome of subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), which may be a phase that precedes the MCI phase of AD.f Patients with SCI report cognitive deficits (eg, forgetfulness and word-finding difficulties) but have no objective evidence of cognitive impairment on neuropsychological tests. Cognitive problems associated with SCI do not cause functional decline.g SCI may reflect the minimal cognitive complaints mentioned in the research criteria for the preclinical phase of AD. Eventually, biomarkers may be able to help clinicians more accurately predict which patients with SCI are most likely to progress to the MCI or dementia phase of AD.

References

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279.

- Galasko D. Biomarkers in non-Alzheimer dementias. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2004;3(6):375-381.

- Geldmacher DS. Treatment guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease: redefining perceptions in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(2):113-121.

- Chertkow H, Massoud F, Nasreddine Z, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 3. Mild cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment without dementia. CMAJ. 2008;178(10):1273-1285.

- Rosenberg PB, Lyketsos C. Mild cognitive impairment: searching for the prodrome of Alzheimer’s disease. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(2):72-78.

- Reisberg B, Shulman MB, Torossian C, et al. Outcome over seven years of healthy adults with and without subjective cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(1):11-24.

- Desai AK, Schwarz L. Subjective cognitive impairment: when to be concerned about ‘senior moments.’ Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):31-44.

Clinical applications

Although pharmacologic therapies for the early phases of AD are not yet available, research supports implementing nonpharmacologic modalities in older adults with MCI as well as those without any cognitive impairment (Table 3).8,11 Growing evidence suggests physicians should encourage patients to lead an active and socially integrated lifestyle that includes leisure activities, cognitive stimulation, meditation, a balanced diet, and daily exercise.8 Practitioners should treat vascular risk factors in geriatric patients with and without cognitive impairment to optimize healthy brain aging and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke.11 By raising awareness of available treatments for early phases of AD, we may be able to reduce the anxiety and sense of helplessness or hopelessness that may accompany an AD diagnosis.

Depression and AD. Having depression nearly doubles one’s risk of developing AD later in life, and depression may exacerbate AD.12 Although the precise mechanism linking depression to AD is unclear, depression seems to exert a toxic effect on the hippocampus.13 Treating depression may prevent or mitigate the rate of memory impairment and overall AD severity and improve a patient’s quality of life, overall health, and ability to function.

Almost one-third of family caregivers become depressed while helping a family member with DAT.14 Directing caregivers to peer support groups and providing them with tips on how to take care of themselves physically, emotionally, and psychologically can be extremely beneficial. Data suggest that improving the psychological and emotional well-being of caretakers may delay nursing home placement of patients with DAT.15 Delaying nursing home placement can substantially improve quality of life and reduce the financial strain on patients and caregivers.

Patients and families often turn to clinicians for advice on what problems they or their loved ones may encounter if they suffer from cognitive impairment. One benefit of the new guidelines is that they can help us become educated about the early phases of AD as well as the long and often difficult course of the disease. In turn, we can better educate our patients and their families about the disease.

As early screening of AD improves, patients in the early phases will have an opportunity to take part in clinical trials for potential pharmacologic treatments of the disease. Our role as clinicians will be to guide patients and their families to such trials and give them the opportunity to help change our understanding of and approach to treating AD. It is important to keep in mind that the new guidelines should not be considered final, but rather as a work in progress that periodically will be revised as AD research progresses.3

Table 3

Promoting healthy brain aging

| Healthy diet (eg, Mediterranean diet) |

| Adequate sleep |

| Daily exercise |

| Smoking cessation |

| Active, socially integrated lifestyle |

| Leisure activities |

| Cognitive stimulation |

| Optimize treatment of depression and other mental illnesses |

| Meditation and other mindfulness strategies (eg, yoga) |

| Spiritual activities |

| Controlling vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity) |

| Source: References 8,11 |

Related Resources

- Alzheimer’s Association. www.alz.org.

- National Institute on Aging. Alzheimer’s disease education and referral center. www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers.

Disclosures

Drs. Kimchi and Desai report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Grossberg is a consultant to Baxter, Forest Laboratories, Merck, Otsuka, and Novartis.

1. Jack CR Jr, Albert MS, Knopman DS, et al. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):257-262.

2. Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280-292.

3. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279.

4. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263-269.

5. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939-944.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

7. Ihl R, Frölich L, Winblad B, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12(1):2-32.

8. Chertkow H, Massoud F, Nasreddine Z, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 3. Mild cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment without dementia. CMAJ. 2008;178(10):1273-1285.

9. McKhann GM. Changing concepts of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2458-2459.

10. Galasko D. Biomarkers in non-Alzheimer’s dementias. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2004;3(6):375-381.

11. Desai AK, Grossberg GT, Chibnall JT. Healthy brain aging: a road map. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(1):1-16.

12. Wilson RS, Hoganson GM, Rajan KB, et al. Temporal course of depressive symptoms during the development of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2010;75(1):21-26.

13. Bremner JD, Narayan M, Anderson ER, et al. Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(1):115-118.

14. Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2090-2097.

15. Mittelman MS, Haley WE, Clay OJ, et al. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1592-1599.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

In 2011, a workgroup of experts from the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute on Aging published new criteria and guidelines for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the first new AD guidelines since 1984.1-4 These criteria reflect data that suggest AD is not synonymous with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) but is a disease that slowly develops over many years as a result of accumulated neuropathologic changes, with dementia representing only the final phase of the disease (Figure).1-4

Figure: Cognitive decline in AD over time

AD: Alzheimer’s disease; MCI: mild cognitive impairment

Source: Adapted from reference 2

This article highlights the similarities and differences of the 1984 and 2011 AD diagnosis guidelines. We also discuss the new guidelines’ limitations and clinical implications.

The 1984 AD criteria

Both the 1984 AD criteria5 and DSM-IV-TR criteria6 rely on the concept that AD is a clinical diagnosis made after a patient develops dementia. That is, diagnosis rests on the physician’s clinical judgment about the etiology of the patient’s symptoms, taking into account reports from the patient, family, and friends, as well as results of neurocognitive testing and mental status evaluation. The 1984 criteria were developed with the expectation that if a patient who met clinical criteria for AD were to undergo an autopsy, he or she likely would have evidence of AD pathology as the underlying etiology. These criteria were developed before researchers discovered that in AD, pathologic changes occur over many years and clinical dementia is the end product of accumulated pathology. The 1984 criteria did not address important phases that precede clinical dementia—such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). See the Table for a summary of the 1984 AD criteria.

Table

The 1984 NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for clinical diagnosis of AD

|

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease; NINCDS-ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association Source: McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939-944 |

The 2011 AD criteria

The new AD criteria differ from the 1984 criteria in 2 major ways:

- expansion of AD into 3 phases, only 1 of which is characterized by dementia

- incorporation of biomarkers to provide information regarding pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease state (Table 1).1-5

The 3 phases. The 2011 criteria expand the definition of AD to include an asymptomatic, preclinical phase; a symptomatic, pre-dementia phase; and a dementia phase. In the initial phase, neuronal toxins such as beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and elevated tau first become detectable. Patients in this phase are asymptomatic or have subtle symptoms. This phase should be viewed as part of a continuum and includes patients who may, for instance, develop Aβ plaques but do not progress to further neurodegeneration.2 The diagnostic criteria of this phase are intended for research purposes only.1,2

Patients in the symptomatic, pre-dementia phase—also known as the MCI phase—exhibit mild decline in memory, attention, and thinking. Although this decline is more than what is expected for the patient’s age and education, it does not compromise everyday activity and functioning.

A patient who develops cognitive or behavioral problems that interfere with his or her ability to function at work or in everyday activities has entered the dementia phase. Similar to the 1984 guidelines, the 2011 criteria classify patients into probable and possible AD dementia. All patients who would have satisfied criteria for probable AD under the 1984 guidelines will satisfy criteria for probable AD dementia under the 2011 criteria.4 The same is not true for possible AD dementia. The 2011 criteria include 2 other major categories for patients with AD dementia: probable and possible AD dementia with evidence of the AD pathophysiological process. These categories are intended for research purposes only, whereas the criteria for the MCI and dementia phases are intended to guide diagnosis in the clinical setting.

By incorporating phases of AD that precede dementia into the disease spectrum, the new guidelines are designed to move clinicians toward earlier diagnosis and treatment.1-3 Similar to how early, pre-symptomatic detection and treatment of conditions such as diabetes and cancer can reduce mortality, improving diagnosis of AD in its early phases may allow clinicians to better test potential therapies and eventually use them to treat at-risk individuals.2,3 Most pharmacotherapies for AD are FDA-approved only for patients diagnosed with clinical dementia. Furthermore, current pharmacotherapies do not alter the course of AD; they have a modest effect in slowing cognitive and functional decline.7,8 If patients in the earlier phases of AD could be recruited for research studies, we may be able to develop new treatments to stop or reverse AD pathology and its clinical manifestations.

Biomarkers. The new criteria incorporate biomarkers to provide information about pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease process. These criteria define biomarkers as physiologic, biochemical, or anatomic parameters that can be measured in vivo and reflect specific features of disease-related pathophysiologic processes.1 Presently, there are no cutoff values to demarcate “normal” levels from “abnormal,” and biomarkers are proposed primarily as research tools because they have not been studied adequately in community settings and laboratory techniques to measure biomarkers have not been standardized.1-4,9

The 5 biomarkers incorporated into the new criteria are divided into 2 categories: biomarkers of Aβ accumulation and those of neuronal degeneration or injury (Table 2).1-4 In the initial, preclinical phase, biomarkers are used to detect changes in the brain—such as amyloid accumulation and nerve cell degeneration—that may already be in process in an individual whose clinical symptoms are subtle or not yet evident.1,2 In this phase, progressive evidence of biomarkers, such as both Aβ accumulation and neuronal injury rather than Aβ accumulation alone, may increase the probability that a patient will decline quickly into the MCI phase.2 Biomarkers of neuronal degeneration or injury especially correlate with the likelihood that the disease will progress to clinical dementia.1 Subtle cognitive symptoms in the preclinical phase also might predict rapid decline into MCI.2

In the MCI and dementia phases, biomarkers are used to determine the level of certainty that AD is responsible for the patient’s symptoms.1,3,4 For example, a patient could meet criteria for a non-AD dementia such as dementia with Lewy bodies, but also meet pathologic criteria for AD on autopsy.3 The diagnostic category of possible AD dementia with evidence of the AD pathophysiologic process is intended for this type of scenario.4 For the MCI phase, the criteria propose levels of certainty that a patient’s MCI syndrome is caused by AD, ranging from MCI due to AD-high likelihood to MCI-unlikely due to AD.3

Research has demonstrated that a patient’s clinical picture doesn’t necessarily reflect the extent of the underlying pathology. For example, a patient could have extensive AD pathology, such as diffuse amyloid plaques, without any obvious clinical symptoms.3 Conversely, although both Aβ deposition and elevated tau are hallmarks of AD, variations in these proteins can be seen in neuropsychiatric disorders other than AD.10 That said, it appears that worsening of clinical symptoms often parallels worsening of neurodegenerative biomarkers.1

Under the 2011 guidelines, biomarkers would not be used to diagnose or exclude AD or MCI, but instead would help improve diagnostic accuracy in individuals with cognitive decline.1,3,4 In other words, AD remains a clinical diagnosis, but these biomarkers could raise or lower the positive predictive value of a clinician’s judgment about the etiology of a patient’s symptoms.

See the Box for a description of the potential risks and benefits of using the new diagnostic criteria.

Table 1

Comparing the 1984 and 2011 AD criteria

| 1984 criteria | 2011 criteria |

|---|---|

| AD is a clinical diagnosis | AD remains a clinical diagnosis but biomarkers serve to improve the accuracy of diagnosis of the disease |

| There is only 1 phase of AD—dementia. | AD is expanded into 3 phases: an asymptomatic, preclinical phase; a symptomatic, pre-dementia phase; and a dementia phase |

| A patient who meets the clinical criteria for AD would be expected to have AD pathology as the underlying etiology were he/she to undergo a brain autopsy | Presently, biomarkers are proposed as research tools only and are not intended to be applied in the clinical setting. However, eventually clinicians will be able to diagnose AD in all 3 phases, as biomarker testing becomes standardized and reliable enough to be accurately applied in clinical settings |

| Little consideration is given to specific neuropathologic changes underlying the disease process | Biomarkers provide information regarding the pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease state |

| Little consideration is given to the idea that pathologic changes occur over many years | Inherent in dividing AD into 3 phases is the concept that AD develops slowly over many years and has a long prodromal phase that is clinically silent |

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease Source: References 1-5 | |

Table 2

5 biomarkers incorporated into the 2011 AD criteria

| Category | Biomarkers |

|---|---|

| Biomarkers of Aβ accumulation | Abnormal tracer retention on amyloid PET imaging |

| Low CSF Aβ42 | |

| Biomarkers of neuronal degeneration or injury | Elevated CSF tau (total and phosphorylated tau) |

| Decreased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on PET | |

| Atrophy on structural magnetic resonance imaging | |

| Aβ: beta-amyloid; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; PET: positron emission tomography Source: References 1-4 | |

The earlier an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis is made, the less certain it is AD.a Biomarkers typically found in individuals with AD also can be found in patients with dementia not caused by AD, such as vascular dementia, as well as in individuals who may never develop dementia.b Additionally, there is no certainty that a patient in an early phase of AD will develop clinical dementia. Falsely diagnosing a patient with AD may lead the individual and their family to feel helpless, hopeless, depressed, anxious, or ashamed and to spend money and other resources preparing for a prognosis that may never come to fruition. Clinicians may feel compelled to assess for biomarkers using expensive, invasive tests that are not yet standardized in an attempt to support the AD diagnosis.

Early diagnosis of AD has many benefits that should not be overlooked, however. It provides patients and their families an opportunity to become familiar with the disease course, which may help some patients cope with the diagnosis. Patients diagnosed in the early stages would be able to make important decisions regarding health care, social, and financial planning before they develop pathology that limits their executive planning abilities or become functionally impaired.

Diagnosing an illness when there are no disease-modifying therapies available is not futile. Some patients with newly diagnosed AD in the pre-dementia phases may want to participate in clinical research trials to help develop therapies for AD. Some data suggest that AD treatment appears to provide the greatest benefit when initiated early in the disease course and maintained over a long duration.c Eventually, we may be able to tailor specific AD treatments in different phases of the disease. For instance, we may discover treatments for patients who show evidence of beta-amyloid plaques but not neuronal injury, or vice versa. Patients also may benefit from education on nonpharmacologic treatments, including reducing vascular risk factors to help improve brain aging,d reducing stress, and learning cognitive strategies such as using mnemonics to aid memory.

In many clinical settings, patients are being clinically diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Research indicates that patients with MCI are at near-term risk of developing dementia, particularly dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.d,e Presently, no definite transition points demarcate MCI from dementia; this progression is based upon clinical judgment.

In the last decade, researchers have begun to describe a syndrome of subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), which may be a phase that precedes the MCI phase of AD.f Patients with SCI report cognitive deficits (eg, forgetfulness and word-finding difficulties) but have no objective evidence of cognitive impairment on neuropsychological tests. Cognitive problems associated with SCI do not cause functional decline.g SCI may reflect the minimal cognitive complaints mentioned in the research criteria for the preclinical phase of AD. Eventually, biomarkers may be able to help clinicians more accurately predict which patients with SCI are most likely to progress to the MCI or dementia phase of AD.

References

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279.

- Galasko D. Biomarkers in non-Alzheimer dementias. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2004;3(6):375-381.

- Geldmacher DS. Treatment guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease: redefining perceptions in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(2):113-121.

- Chertkow H, Massoud F, Nasreddine Z, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 3. Mild cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment without dementia. CMAJ. 2008;178(10):1273-1285.

- Rosenberg PB, Lyketsos C. Mild cognitive impairment: searching for the prodrome of Alzheimer’s disease. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(2):72-78.

- Reisberg B, Shulman MB, Torossian C, et al. Outcome over seven years of healthy adults with and without subjective cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(1):11-24.

- Desai AK, Schwarz L. Subjective cognitive impairment: when to be concerned about ‘senior moments.’ Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):31-44.

Clinical applications

Although pharmacologic therapies for the early phases of AD are not yet available, research supports implementing nonpharmacologic modalities in older adults with MCI as well as those without any cognitive impairment (Table 3).8,11 Growing evidence suggests physicians should encourage patients to lead an active and socially integrated lifestyle that includes leisure activities, cognitive stimulation, meditation, a balanced diet, and daily exercise.8 Practitioners should treat vascular risk factors in geriatric patients with and without cognitive impairment to optimize healthy brain aging and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke.11 By raising awareness of available treatments for early phases of AD, we may be able to reduce the anxiety and sense of helplessness or hopelessness that may accompany an AD diagnosis.

Depression and AD. Having depression nearly doubles one’s risk of developing AD later in life, and depression may exacerbate AD.12 Although the precise mechanism linking depression to AD is unclear, depression seems to exert a toxic effect on the hippocampus.13 Treating depression may prevent or mitigate the rate of memory impairment and overall AD severity and improve a patient’s quality of life, overall health, and ability to function.

Almost one-third of family caregivers become depressed while helping a family member with DAT.14 Directing caregivers to peer support groups and providing them with tips on how to take care of themselves physically, emotionally, and psychologically can be extremely beneficial. Data suggest that improving the psychological and emotional well-being of caretakers may delay nursing home placement of patients with DAT.15 Delaying nursing home placement can substantially improve quality of life and reduce the financial strain on patients and caregivers.

Patients and families often turn to clinicians for advice on what problems they or their loved ones may encounter if they suffer from cognitive impairment. One benefit of the new guidelines is that they can help us become educated about the early phases of AD as well as the long and often difficult course of the disease. In turn, we can better educate our patients and their families about the disease.

As early screening of AD improves, patients in the early phases will have an opportunity to take part in clinical trials for potential pharmacologic treatments of the disease. Our role as clinicians will be to guide patients and their families to such trials and give them the opportunity to help change our understanding of and approach to treating AD. It is important to keep in mind that the new guidelines should not be considered final, but rather as a work in progress that periodically will be revised as AD research progresses.3

Table 3

Promoting healthy brain aging

| Healthy diet (eg, Mediterranean diet) |

| Adequate sleep |

| Daily exercise |

| Smoking cessation |

| Active, socially integrated lifestyle |

| Leisure activities |

| Cognitive stimulation |

| Optimize treatment of depression and other mental illnesses |

| Meditation and other mindfulness strategies (eg, yoga) |

| Spiritual activities |

| Controlling vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity) |

| Source: References 8,11 |

Related Resources

- Alzheimer’s Association. www.alz.org.

- National Institute on Aging. Alzheimer’s disease education and referral center. www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers.

Disclosures

Drs. Kimchi and Desai report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Grossberg is a consultant to Baxter, Forest Laboratories, Merck, Otsuka, and Novartis.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

In 2011, a workgroup of experts from the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute on Aging published new criteria and guidelines for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the first new AD guidelines since 1984.1-4 These criteria reflect data that suggest AD is not synonymous with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) but is a disease that slowly develops over many years as a result of accumulated neuropathologic changes, with dementia representing only the final phase of the disease (Figure).1-4

Figure: Cognitive decline in AD over time

AD: Alzheimer’s disease; MCI: mild cognitive impairment

Source: Adapted from reference 2

This article highlights the similarities and differences of the 1984 and 2011 AD diagnosis guidelines. We also discuss the new guidelines’ limitations and clinical implications.

The 1984 AD criteria

Both the 1984 AD criteria5 and DSM-IV-TR criteria6 rely on the concept that AD is a clinical diagnosis made after a patient develops dementia. That is, diagnosis rests on the physician’s clinical judgment about the etiology of the patient’s symptoms, taking into account reports from the patient, family, and friends, as well as results of neurocognitive testing and mental status evaluation. The 1984 criteria were developed with the expectation that if a patient who met clinical criteria for AD were to undergo an autopsy, he or she likely would have evidence of AD pathology as the underlying etiology. These criteria were developed before researchers discovered that in AD, pathologic changes occur over many years and clinical dementia is the end product of accumulated pathology. The 1984 criteria did not address important phases that precede clinical dementia—such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). See the Table for a summary of the 1984 AD criteria.

Table

The 1984 NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for clinical diagnosis of AD

|

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease; NINCDS-ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association Source: McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939-944 |

The 2011 AD criteria

The new AD criteria differ from the 1984 criteria in 2 major ways:

- expansion of AD into 3 phases, only 1 of which is characterized by dementia

- incorporation of biomarkers to provide information regarding pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease state (Table 1).1-5

The 3 phases. The 2011 criteria expand the definition of AD to include an asymptomatic, preclinical phase; a symptomatic, pre-dementia phase; and a dementia phase. In the initial phase, neuronal toxins such as beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and elevated tau first become detectable. Patients in this phase are asymptomatic or have subtle symptoms. This phase should be viewed as part of a continuum and includes patients who may, for instance, develop Aβ plaques but do not progress to further neurodegeneration.2 The diagnostic criteria of this phase are intended for research purposes only.1,2

Patients in the symptomatic, pre-dementia phase—also known as the MCI phase—exhibit mild decline in memory, attention, and thinking. Although this decline is more than what is expected for the patient’s age and education, it does not compromise everyday activity and functioning.

A patient who develops cognitive or behavioral problems that interfere with his or her ability to function at work or in everyday activities has entered the dementia phase. Similar to the 1984 guidelines, the 2011 criteria classify patients into probable and possible AD dementia. All patients who would have satisfied criteria for probable AD under the 1984 guidelines will satisfy criteria for probable AD dementia under the 2011 criteria.4 The same is not true for possible AD dementia. The 2011 criteria include 2 other major categories for patients with AD dementia: probable and possible AD dementia with evidence of the AD pathophysiological process. These categories are intended for research purposes only, whereas the criteria for the MCI and dementia phases are intended to guide diagnosis in the clinical setting.

By incorporating phases of AD that precede dementia into the disease spectrum, the new guidelines are designed to move clinicians toward earlier diagnosis and treatment.1-3 Similar to how early, pre-symptomatic detection and treatment of conditions such as diabetes and cancer can reduce mortality, improving diagnosis of AD in its early phases may allow clinicians to better test potential therapies and eventually use them to treat at-risk individuals.2,3 Most pharmacotherapies for AD are FDA-approved only for patients diagnosed with clinical dementia. Furthermore, current pharmacotherapies do not alter the course of AD; they have a modest effect in slowing cognitive and functional decline.7,8 If patients in the earlier phases of AD could be recruited for research studies, we may be able to develop new treatments to stop or reverse AD pathology and its clinical manifestations.

Biomarkers. The new criteria incorporate biomarkers to provide information about pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease process. These criteria define biomarkers as physiologic, biochemical, or anatomic parameters that can be measured in vivo and reflect specific features of disease-related pathophysiologic processes.1 Presently, there are no cutoff values to demarcate “normal” levels from “abnormal,” and biomarkers are proposed primarily as research tools because they have not been studied adequately in community settings and laboratory techniques to measure biomarkers have not been standardized.1-4,9

The 5 biomarkers incorporated into the new criteria are divided into 2 categories: biomarkers of Aβ accumulation and those of neuronal degeneration or injury (Table 2).1-4 In the initial, preclinical phase, biomarkers are used to detect changes in the brain—such as amyloid accumulation and nerve cell degeneration—that may already be in process in an individual whose clinical symptoms are subtle or not yet evident.1,2 In this phase, progressive evidence of biomarkers, such as both Aβ accumulation and neuronal injury rather than Aβ accumulation alone, may increase the probability that a patient will decline quickly into the MCI phase.2 Biomarkers of neuronal degeneration or injury especially correlate with the likelihood that the disease will progress to clinical dementia.1 Subtle cognitive symptoms in the preclinical phase also might predict rapid decline into MCI.2

In the MCI and dementia phases, biomarkers are used to determine the level of certainty that AD is responsible for the patient’s symptoms.1,3,4 For example, a patient could meet criteria for a non-AD dementia such as dementia with Lewy bodies, but also meet pathologic criteria for AD on autopsy.3 The diagnostic category of possible AD dementia with evidence of the AD pathophysiologic process is intended for this type of scenario.4 For the MCI phase, the criteria propose levels of certainty that a patient’s MCI syndrome is caused by AD, ranging from MCI due to AD-high likelihood to MCI-unlikely due to AD.3

Research has demonstrated that a patient’s clinical picture doesn’t necessarily reflect the extent of the underlying pathology. For example, a patient could have extensive AD pathology, such as diffuse amyloid plaques, without any obvious clinical symptoms.3 Conversely, although both Aβ deposition and elevated tau are hallmarks of AD, variations in these proteins can be seen in neuropsychiatric disorders other than AD.10 That said, it appears that worsening of clinical symptoms often parallels worsening of neurodegenerative biomarkers.1

Under the 2011 guidelines, biomarkers would not be used to diagnose or exclude AD or MCI, but instead would help improve diagnostic accuracy in individuals with cognitive decline.1,3,4 In other words, AD remains a clinical diagnosis, but these biomarkers could raise or lower the positive predictive value of a clinician’s judgment about the etiology of a patient’s symptoms.

See the Box for a description of the potential risks and benefits of using the new diagnostic criteria.

Table 1

Comparing the 1984 and 2011 AD criteria

| 1984 criteria | 2011 criteria |

|---|---|

| AD is a clinical diagnosis | AD remains a clinical diagnosis but biomarkers serve to improve the accuracy of diagnosis of the disease |

| There is only 1 phase of AD—dementia. | AD is expanded into 3 phases: an asymptomatic, preclinical phase; a symptomatic, pre-dementia phase; and a dementia phase |

| A patient who meets the clinical criteria for AD would be expected to have AD pathology as the underlying etiology were he/she to undergo a brain autopsy | Presently, biomarkers are proposed as research tools only and are not intended to be applied in the clinical setting. However, eventually clinicians will be able to diagnose AD in all 3 phases, as biomarker testing becomes standardized and reliable enough to be accurately applied in clinical settings |

| Little consideration is given to specific neuropathologic changes underlying the disease process | Biomarkers provide information regarding the pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease state |

| Little consideration is given to the idea that pathologic changes occur over many years | Inherent in dividing AD into 3 phases is the concept that AD develops slowly over many years and has a long prodromal phase that is clinically silent |

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease Source: References 1-5 | |

Table 2

5 biomarkers incorporated into the 2011 AD criteria

| Category | Biomarkers |

|---|---|

| Biomarkers of Aβ accumulation | Abnormal tracer retention on amyloid PET imaging |

| Low CSF Aβ42 | |

| Biomarkers of neuronal degeneration or injury | Elevated CSF tau (total and phosphorylated tau) |

| Decreased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on PET | |

| Atrophy on structural magnetic resonance imaging | |

| Aβ: beta-amyloid; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; PET: positron emission tomography Source: References 1-4 | |

The earlier an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis is made, the less certain it is AD.a Biomarkers typically found in individuals with AD also can be found in patients with dementia not caused by AD, such as vascular dementia, as well as in individuals who may never develop dementia.b Additionally, there is no certainty that a patient in an early phase of AD will develop clinical dementia. Falsely diagnosing a patient with AD may lead the individual and their family to feel helpless, hopeless, depressed, anxious, or ashamed and to spend money and other resources preparing for a prognosis that may never come to fruition. Clinicians may feel compelled to assess for biomarkers using expensive, invasive tests that are not yet standardized in an attempt to support the AD diagnosis.

Early diagnosis of AD has many benefits that should not be overlooked, however. It provides patients and their families an opportunity to become familiar with the disease course, which may help some patients cope with the diagnosis. Patients diagnosed in the early stages would be able to make important decisions regarding health care, social, and financial planning before they develop pathology that limits their executive planning abilities or become functionally impaired.

Diagnosing an illness when there are no disease-modifying therapies available is not futile. Some patients with newly diagnosed AD in the pre-dementia phases may want to participate in clinical research trials to help develop therapies for AD. Some data suggest that AD treatment appears to provide the greatest benefit when initiated early in the disease course and maintained over a long duration.c Eventually, we may be able to tailor specific AD treatments in different phases of the disease. For instance, we may discover treatments for patients who show evidence of beta-amyloid plaques but not neuronal injury, or vice versa. Patients also may benefit from education on nonpharmacologic treatments, including reducing vascular risk factors to help improve brain aging,d reducing stress, and learning cognitive strategies such as using mnemonics to aid memory.

In many clinical settings, patients are being clinically diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Research indicates that patients with MCI are at near-term risk of developing dementia, particularly dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.d,e Presently, no definite transition points demarcate MCI from dementia; this progression is based upon clinical judgment.

In the last decade, researchers have begun to describe a syndrome of subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), which may be a phase that precedes the MCI phase of AD.f Patients with SCI report cognitive deficits (eg, forgetfulness and word-finding difficulties) but have no objective evidence of cognitive impairment on neuropsychological tests. Cognitive problems associated with SCI do not cause functional decline.g SCI may reflect the minimal cognitive complaints mentioned in the research criteria for the preclinical phase of AD. Eventually, biomarkers may be able to help clinicians more accurately predict which patients with SCI are most likely to progress to the MCI or dementia phase of AD.

References

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279.

- Galasko D. Biomarkers in non-Alzheimer dementias. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2004;3(6):375-381.

- Geldmacher DS. Treatment guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease: redefining perceptions in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(2):113-121.

- Chertkow H, Massoud F, Nasreddine Z, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 3. Mild cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment without dementia. CMAJ. 2008;178(10):1273-1285.

- Rosenberg PB, Lyketsos C. Mild cognitive impairment: searching for the prodrome of Alzheimer’s disease. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(2):72-78.

- Reisberg B, Shulman MB, Torossian C, et al. Outcome over seven years of healthy adults with and without subjective cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(1):11-24.

- Desai AK, Schwarz L. Subjective cognitive impairment: when to be concerned about ‘senior moments.’ Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):31-44.

Clinical applications

Although pharmacologic therapies for the early phases of AD are not yet available, research supports implementing nonpharmacologic modalities in older adults with MCI as well as those without any cognitive impairment (Table 3).8,11 Growing evidence suggests physicians should encourage patients to lead an active and socially integrated lifestyle that includes leisure activities, cognitive stimulation, meditation, a balanced diet, and daily exercise.8 Practitioners should treat vascular risk factors in geriatric patients with and without cognitive impairment to optimize healthy brain aging and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke.11 By raising awareness of available treatments for early phases of AD, we may be able to reduce the anxiety and sense of helplessness or hopelessness that may accompany an AD diagnosis.

Depression and AD. Having depression nearly doubles one’s risk of developing AD later in life, and depression may exacerbate AD.12 Although the precise mechanism linking depression to AD is unclear, depression seems to exert a toxic effect on the hippocampus.13 Treating depression may prevent or mitigate the rate of memory impairment and overall AD severity and improve a patient’s quality of life, overall health, and ability to function.

Almost one-third of family caregivers become depressed while helping a family member with DAT.14 Directing caregivers to peer support groups and providing them with tips on how to take care of themselves physically, emotionally, and psychologically can be extremely beneficial. Data suggest that improving the psychological and emotional well-being of caretakers may delay nursing home placement of patients with DAT.15 Delaying nursing home placement can substantially improve quality of life and reduce the financial strain on patients and caregivers.

Patients and families often turn to clinicians for advice on what problems they or their loved ones may encounter if they suffer from cognitive impairment. One benefit of the new guidelines is that they can help us become educated about the early phases of AD as well as the long and often difficult course of the disease. In turn, we can better educate our patients and their families about the disease.

As early screening of AD improves, patients in the early phases will have an opportunity to take part in clinical trials for potential pharmacologic treatments of the disease. Our role as clinicians will be to guide patients and their families to such trials and give them the opportunity to help change our understanding of and approach to treating AD. It is important to keep in mind that the new guidelines should not be considered final, but rather as a work in progress that periodically will be revised as AD research progresses.3

Table 3

Promoting healthy brain aging

| Healthy diet (eg, Mediterranean diet) |

| Adequate sleep |

| Daily exercise |

| Smoking cessation |

| Active, socially integrated lifestyle |

| Leisure activities |

| Cognitive stimulation |

| Optimize treatment of depression and other mental illnesses |

| Meditation and other mindfulness strategies (eg, yoga) |

| Spiritual activities |

| Controlling vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity) |

| Source: References 8,11 |

Related Resources

- Alzheimer’s Association. www.alz.org.

- National Institute on Aging. Alzheimer’s disease education and referral center. www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers.

Disclosures

Drs. Kimchi and Desai report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Grossberg is a consultant to Baxter, Forest Laboratories, Merck, Otsuka, and Novartis.

1. Jack CR Jr, Albert MS, Knopman DS, et al. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):257-262.

2. Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280-292.

3. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279.

4. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263-269.

5. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939-944.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

7. Ihl R, Frölich L, Winblad B, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12(1):2-32.

8. Chertkow H, Massoud F, Nasreddine Z, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 3. Mild cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment without dementia. CMAJ. 2008;178(10):1273-1285.

9. McKhann GM. Changing concepts of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2458-2459.

10. Galasko D. Biomarkers in non-Alzheimer’s dementias. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2004;3(6):375-381.

11. Desai AK, Grossberg GT, Chibnall JT. Healthy brain aging: a road map. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(1):1-16.

12. Wilson RS, Hoganson GM, Rajan KB, et al. Temporal course of depressive symptoms during the development of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2010;75(1):21-26.

13. Bremner JD, Narayan M, Anderson ER, et al. Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(1):115-118.

14. Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2090-2097.

15. Mittelman MS, Haley WE, Clay OJ, et al. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1592-1599.

1. Jack CR Jr, Albert MS, Knopman DS, et al. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):257-262.

2. Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280-292.

3. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279.

4. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263-269.

5. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939-944.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

7. Ihl R, Frölich L, Winblad B, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12(1):2-32.

8. Chertkow H, Massoud F, Nasreddine Z, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 3. Mild cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment without dementia. CMAJ. 2008;178(10):1273-1285.

9. McKhann GM. Changing concepts of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2458-2459.

10. Galasko D. Biomarkers in non-Alzheimer’s dementias. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2004;3(6):375-381.

11. Desai AK, Grossberg GT, Chibnall JT. Healthy brain aging: a road map. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(1):1-16.

12. Wilson RS, Hoganson GM, Rajan KB, et al. Temporal course of depressive symptoms during the development of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2010;75(1):21-26.

13. Bremner JD, Narayan M, Anderson ER, et al. Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(1):115-118.

14. Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2090-2097.

15. Mittelman MS, Haley WE, Clay OJ, et al. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1592-1599.