User login

Secondary Syphilis Mimicking Molluscum Contagiosum in the Beard Area of an AIDS Patient

To the Editor:

A 46-year-old man with a history of AIDS (viral load, 28,186 copies/mL; CD4 count, 22 cells/μL) presented with a 40-lb weight loss over the last 6 months as well as dysphagia and a new-onset pruritic facial eruption of 1 week’s duration. The facial lesions quickly spread to involve the beard area and the upper neck. His medical history was notable for nicotine dependence, seborrheic dermatitis, molluscum contagiosum (MC), treated neurosyphilis and latent tuberculosis, hypertension, a liver mass suspected to be a hemangioma, and erythrocytosis. He was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus infection 19 years prior to presentation and was not compliant with the prescribed highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Skin examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescing, 2- to 12-mm, nonumbilicated, hyperkeratotic papules and nodules localized to the left and right beard areas (Figure 1A). A few discrete, 2- to 5-mm, umbilicated papules were noted in the right beard area (Figure 1B), as well as on the right side of the neck (Figure 1C), buttocks, and legs. Mild erythema with yellow-white scale was present in the alar creases. Examination of the oropharyngeal mucosa revealed multiple thick white plaques that were easily scraped off with a tongue depressor. Examination of the palms, soles, and anogenital areas was normal.

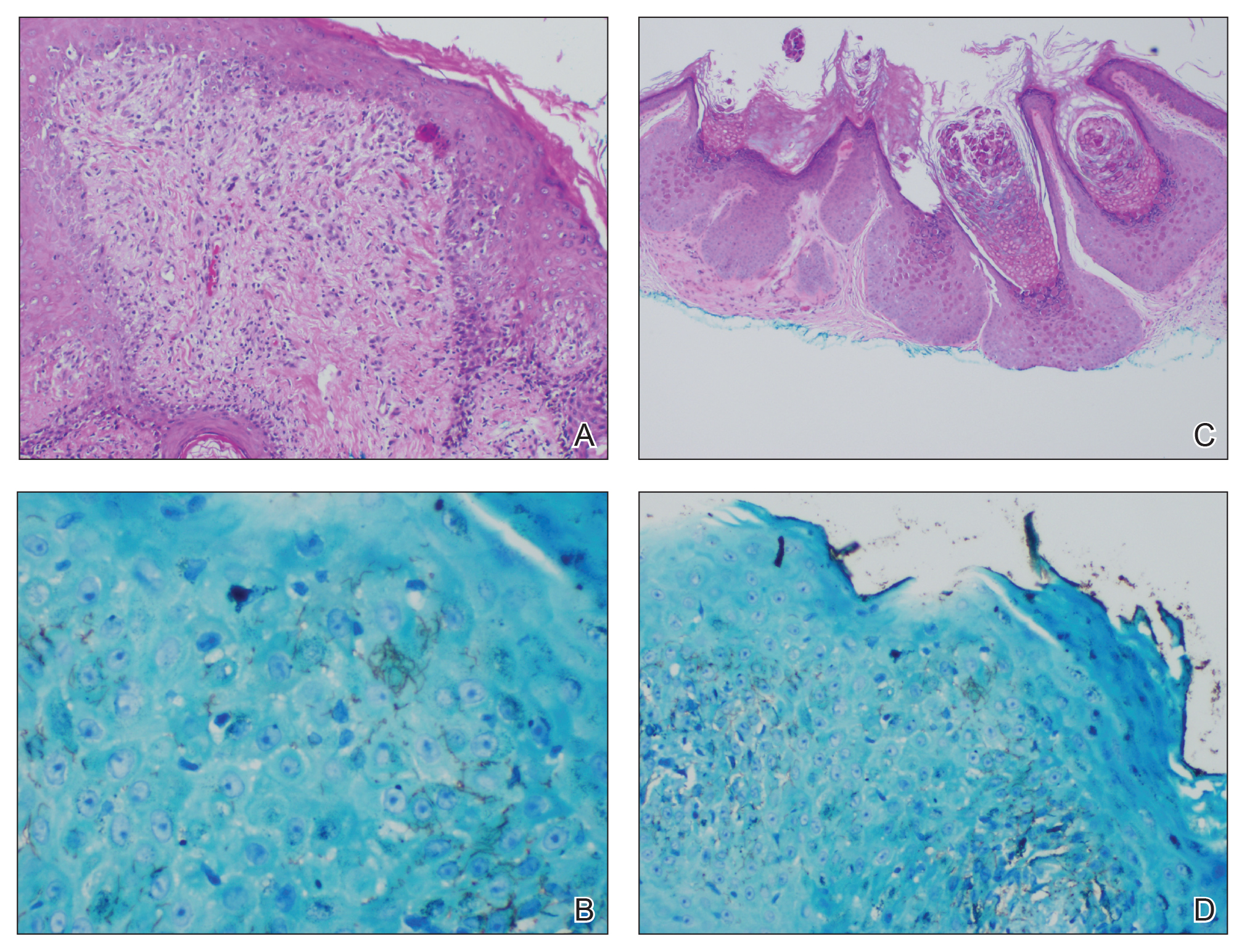

A punch biopsy of a nonumbilicated hyperkeratotic papule from the left beard area demonstrated spongiosis; neutrophilic microabscess formation; plasma cells; and a superficial and deep perivascular, predominantly lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2A). Spirochete immunohistochemical staining of tissue highlighted abundant organisms in the dermoepidermal junction and vascular endothelial cells (Figure 2B). Other tissue stains for bacteria, including acid-fast bacilli, and fungi were negative. Bacterial culture of tissue from the lesion in the left beard area grew Staphylococcus aureus. Results of acid-fast and fungal cultures of tissue were negative. Shave biopsy of the umbilicated papule on the right side of the neck demonstrated classic invagination of the epidermis into the dermis and intracytoplasmic viral inclusions consistent with MC (Figure 2C). Spirochete immunohistochemical staining of the same tissue sample was negative (Figure 2D).

Serum rapid plasma reagin was reactive with a titer of 1:128 compared to the last known reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:1 five years prior to presentation. A fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test and VDRL test of cerebrospinal fluid was nonreactive. Fungal, bacterial, and acid-fast cultures of cerebral spinal fluid and a cryptococcal antigen test were negative. Serum cryptococcal antigen and coccidioides complement fixation tests were negative. Cytomegalovirus plasma polymerase chain reaction and urine histoplasma antigen testing were negative. Computed tomography of the chest revealed a new 1.9×1.6×2.1-cm3 cavitary lesion with distal tree-in-bud opacities in the lingula of the left lung. Acid-fast blood culture was negative, and acid-fast sputum culture was positive for Mycobacterium kansasii.

The cutaneous pathology findings and serologic findings confirmed the diagnoses of cutaneous secondary syphilis (SS) in the beard area and MC on the right side of the neck. Clinical diagnoses of seborrheic dermatitis of the alar creases and esophageal candidiasis also were made. The patient was treated with intramuscular penicillin G 2.4 million U once weekly for 3 weeks. The lesions confined to the beard area rapidly resolved within 7 days after the first dose of antibiotics, which further supported the diagnosis of localized cutaneous SS. Fluconazole 100 mg once daily was prescribed for the esophageal candidiasis, and he also was started on a regimen of rifampin 600 mg once daily, isoniazid 300 mg once daily, ethambutol 1200 mg once daily, and pyrazinamide 1500 mg once daily.

Syphilis is well known as the great masquerader due to its many possible manifestations. Many patients present with typical palmar and plantar dermatoses.1 Other documented SS presentations include eruptions ranging from a few to diffusely disseminated maculopapular lesions with or without scale on the trunk and upper extremities; pustular and nodular lesions of the face; alopecia; grayish white patches on the oral mucosa; and ulcerative, psoriasiform, follicular, and lichenoid lesions.2 Cutaneous SS has not been commonly reported in a localized distribution to the beard area with a clinical appearance mimicking hyperkeratotic MC lesions.3 Secondary syphilis is not known to spread through autoinoculation, presumably from shaving (as in our case), as might occur with other cutaneous infectious processes such as MC, verruca vulgaris, S aureus, and dermatophytosis in the beard area.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic papules and nodules localized to the beard area in human immunodeficiency virus–infected males includes MC, verruca vulgaris, chronic verrucous varicella-zoster virus, crusted scabies, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, hypertrophic lichen planus, and disseminated deep fungal infections including cryptococcosis and coccidioidomycosis. In the setting of immunosuppression, the diagnosis of hyperkeratotic MC was favored in our patient given the co-location of classic umbilicated MC lesions with the hyperkeratotic papules and nodules. It is common to see MC autoinoculated in the beard area in men from shaving, as well as for MC to present in an atypical manner, particularly as hyperkeratotic lesions, in patients with AIDS.4 The predominant localized beard distribution and lack of other mucocutaneous manifestations of SS at presentation supported a clinical diagnosis of hyperkeratotic MC in our patient.

Unique presentations of SS have been documented, including nodular lesions of the face, but they typically have been accompanied by other stigmata of SS such as the classic palmoplantar or truncal maculopapular rash.3 One notable difference in our case was the localized beard distribution of the syphilitic cutaneous lesions in a man with AIDS. Our case reinforces the importance of cutaneous biopsies in immunocompromised patients. It is known that SS spreads hematogenously; however, in our case it was suspected that the new lesions may have spread locally through autoinoculation via beard hair removal, as the hyperkeratotic lesions were limited to the beard area. Koebnerization secondary to trauma induced by beard hair removal was considered in this case; however, koebnerization is known to occur in noninfectious dermatologic conditions, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and vitiligo, but not in infections such as syphilis. Our case is pivotal in raising the question of whether SS can be autoinoculated in the beard area.

- Baughn RE, Musher DM. Secondary syphilitic lesions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:205-216.

- Dourmishev LA, Dourmishev AL. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Cohen SE, Klausner JD, Engelman J, et al. Syphilis in the modern era: an update for physicians. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27:705-722.

- Filo-Rogulska M, Pindycka-Plaszcznska M, Januszewski K, et al. Disseminated atypical molluscum contagiosum as a presenting symptom of HIV infection. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:56-58.

To the Editor:

A 46-year-old man with a history of AIDS (viral load, 28,186 copies/mL; CD4 count, 22 cells/μL) presented with a 40-lb weight loss over the last 6 months as well as dysphagia and a new-onset pruritic facial eruption of 1 week’s duration. The facial lesions quickly spread to involve the beard area and the upper neck. His medical history was notable for nicotine dependence, seborrheic dermatitis, molluscum contagiosum (MC), treated neurosyphilis and latent tuberculosis, hypertension, a liver mass suspected to be a hemangioma, and erythrocytosis. He was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus infection 19 years prior to presentation and was not compliant with the prescribed highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Skin examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescing, 2- to 12-mm, nonumbilicated, hyperkeratotic papules and nodules localized to the left and right beard areas (Figure 1A). A few discrete, 2- to 5-mm, umbilicated papules were noted in the right beard area (Figure 1B), as well as on the right side of the neck (Figure 1C), buttocks, and legs. Mild erythema with yellow-white scale was present in the alar creases. Examination of the oropharyngeal mucosa revealed multiple thick white plaques that were easily scraped off with a tongue depressor. Examination of the palms, soles, and anogenital areas was normal.

A punch biopsy of a nonumbilicated hyperkeratotic papule from the left beard area demonstrated spongiosis; neutrophilic microabscess formation; plasma cells; and a superficial and deep perivascular, predominantly lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2A). Spirochete immunohistochemical staining of tissue highlighted abundant organisms in the dermoepidermal junction and vascular endothelial cells (Figure 2B). Other tissue stains for bacteria, including acid-fast bacilli, and fungi were negative. Bacterial culture of tissue from the lesion in the left beard area grew Staphylococcus aureus. Results of acid-fast and fungal cultures of tissue were negative. Shave biopsy of the umbilicated papule on the right side of the neck demonstrated classic invagination of the epidermis into the dermis and intracytoplasmic viral inclusions consistent with MC (Figure 2C). Spirochete immunohistochemical staining of the same tissue sample was negative (Figure 2D).

Serum rapid plasma reagin was reactive with a titer of 1:128 compared to the last known reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:1 five years prior to presentation. A fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test and VDRL test of cerebrospinal fluid was nonreactive. Fungal, bacterial, and acid-fast cultures of cerebral spinal fluid and a cryptococcal antigen test were negative. Serum cryptococcal antigen and coccidioides complement fixation tests were negative. Cytomegalovirus plasma polymerase chain reaction and urine histoplasma antigen testing were negative. Computed tomography of the chest revealed a new 1.9×1.6×2.1-cm3 cavitary lesion with distal tree-in-bud opacities in the lingula of the left lung. Acid-fast blood culture was negative, and acid-fast sputum culture was positive for Mycobacterium kansasii.

The cutaneous pathology findings and serologic findings confirmed the diagnoses of cutaneous secondary syphilis (SS) in the beard area and MC on the right side of the neck. Clinical diagnoses of seborrheic dermatitis of the alar creases and esophageal candidiasis also were made. The patient was treated with intramuscular penicillin G 2.4 million U once weekly for 3 weeks. The lesions confined to the beard area rapidly resolved within 7 days after the first dose of antibiotics, which further supported the diagnosis of localized cutaneous SS. Fluconazole 100 mg once daily was prescribed for the esophageal candidiasis, and he also was started on a regimen of rifampin 600 mg once daily, isoniazid 300 mg once daily, ethambutol 1200 mg once daily, and pyrazinamide 1500 mg once daily.

Syphilis is well known as the great masquerader due to its many possible manifestations. Many patients present with typical palmar and plantar dermatoses.1 Other documented SS presentations include eruptions ranging from a few to diffusely disseminated maculopapular lesions with or without scale on the trunk and upper extremities; pustular and nodular lesions of the face; alopecia; grayish white patches on the oral mucosa; and ulcerative, psoriasiform, follicular, and lichenoid lesions.2 Cutaneous SS has not been commonly reported in a localized distribution to the beard area with a clinical appearance mimicking hyperkeratotic MC lesions.3 Secondary syphilis is not known to spread through autoinoculation, presumably from shaving (as in our case), as might occur with other cutaneous infectious processes such as MC, verruca vulgaris, S aureus, and dermatophytosis in the beard area.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic papules and nodules localized to the beard area in human immunodeficiency virus–infected males includes MC, verruca vulgaris, chronic verrucous varicella-zoster virus, crusted scabies, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, hypertrophic lichen planus, and disseminated deep fungal infections including cryptococcosis and coccidioidomycosis. In the setting of immunosuppression, the diagnosis of hyperkeratotic MC was favored in our patient given the co-location of classic umbilicated MC lesions with the hyperkeratotic papules and nodules. It is common to see MC autoinoculated in the beard area in men from shaving, as well as for MC to present in an atypical manner, particularly as hyperkeratotic lesions, in patients with AIDS.4 The predominant localized beard distribution and lack of other mucocutaneous manifestations of SS at presentation supported a clinical diagnosis of hyperkeratotic MC in our patient.

Unique presentations of SS have been documented, including nodular lesions of the face, but they typically have been accompanied by other stigmata of SS such as the classic palmoplantar or truncal maculopapular rash.3 One notable difference in our case was the localized beard distribution of the syphilitic cutaneous lesions in a man with AIDS. Our case reinforces the importance of cutaneous biopsies in immunocompromised patients. It is known that SS spreads hematogenously; however, in our case it was suspected that the new lesions may have spread locally through autoinoculation via beard hair removal, as the hyperkeratotic lesions were limited to the beard area. Koebnerization secondary to trauma induced by beard hair removal was considered in this case; however, koebnerization is known to occur in noninfectious dermatologic conditions, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and vitiligo, but not in infections such as syphilis. Our case is pivotal in raising the question of whether SS can be autoinoculated in the beard area.

To the Editor:

A 46-year-old man with a history of AIDS (viral load, 28,186 copies/mL; CD4 count, 22 cells/μL) presented with a 40-lb weight loss over the last 6 months as well as dysphagia and a new-onset pruritic facial eruption of 1 week’s duration. The facial lesions quickly spread to involve the beard area and the upper neck. His medical history was notable for nicotine dependence, seborrheic dermatitis, molluscum contagiosum (MC), treated neurosyphilis and latent tuberculosis, hypertension, a liver mass suspected to be a hemangioma, and erythrocytosis. He was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus infection 19 years prior to presentation and was not compliant with the prescribed highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Skin examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescing, 2- to 12-mm, nonumbilicated, hyperkeratotic papules and nodules localized to the left and right beard areas (Figure 1A). A few discrete, 2- to 5-mm, umbilicated papules were noted in the right beard area (Figure 1B), as well as on the right side of the neck (Figure 1C), buttocks, and legs. Mild erythema with yellow-white scale was present in the alar creases. Examination of the oropharyngeal mucosa revealed multiple thick white plaques that were easily scraped off with a tongue depressor. Examination of the palms, soles, and anogenital areas was normal.

A punch biopsy of a nonumbilicated hyperkeratotic papule from the left beard area demonstrated spongiosis; neutrophilic microabscess formation; plasma cells; and a superficial and deep perivascular, predominantly lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2A). Spirochete immunohistochemical staining of tissue highlighted abundant organisms in the dermoepidermal junction and vascular endothelial cells (Figure 2B). Other tissue stains for bacteria, including acid-fast bacilli, and fungi were negative. Bacterial culture of tissue from the lesion in the left beard area grew Staphylococcus aureus. Results of acid-fast and fungal cultures of tissue were negative. Shave biopsy of the umbilicated papule on the right side of the neck demonstrated classic invagination of the epidermis into the dermis and intracytoplasmic viral inclusions consistent with MC (Figure 2C). Spirochete immunohistochemical staining of the same tissue sample was negative (Figure 2D).

Serum rapid plasma reagin was reactive with a titer of 1:128 compared to the last known reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:1 five years prior to presentation. A fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test and VDRL test of cerebrospinal fluid was nonreactive. Fungal, bacterial, and acid-fast cultures of cerebral spinal fluid and a cryptococcal antigen test were negative. Serum cryptococcal antigen and coccidioides complement fixation tests were negative. Cytomegalovirus plasma polymerase chain reaction and urine histoplasma antigen testing were negative. Computed tomography of the chest revealed a new 1.9×1.6×2.1-cm3 cavitary lesion with distal tree-in-bud opacities in the lingula of the left lung. Acid-fast blood culture was negative, and acid-fast sputum culture was positive for Mycobacterium kansasii.

The cutaneous pathology findings and serologic findings confirmed the diagnoses of cutaneous secondary syphilis (SS) in the beard area and MC on the right side of the neck. Clinical diagnoses of seborrheic dermatitis of the alar creases and esophageal candidiasis also were made. The patient was treated with intramuscular penicillin G 2.4 million U once weekly for 3 weeks. The lesions confined to the beard area rapidly resolved within 7 days after the first dose of antibiotics, which further supported the diagnosis of localized cutaneous SS. Fluconazole 100 mg once daily was prescribed for the esophageal candidiasis, and he also was started on a regimen of rifampin 600 mg once daily, isoniazid 300 mg once daily, ethambutol 1200 mg once daily, and pyrazinamide 1500 mg once daily.

Syphilis is well known as the great masquerader due to its many possible manifestations. Many patients present with typical palmar and plantar dermatoses.1 Other documented SS presentations include eruptions ranging from a few to diffusely disseminated maculopapular lesions with or without scale on the trunk and upper extremities; pustular and nodular lesions of the face; alopecia; grayish white patches on the oral mucosa; and ulcerative, psoriasiform, follicular, and lichenoid lesions.2 Cutaneous SS has not been commonly reported in a localized distribution to the beard area with a clinical appearance mimicking hyperkeratotic MC lesions.3 Secondary syphilis is not known to spread through autoinoculation, presumably from shaving (as in our case), as might occur with other cutaneous infectious processes such as MC, verruca vulgaris, S aureus, and dermatophytosis in the beard area.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic papules and nodules localized to the beard area in human immunodeficiency virus–infected males includes MC, verruca vulgaris, chronic verrucous varicella-zoster virus, crusted scabies, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, hypertrophic lichen planus, and disseminated deep fungal infections including cryptococcosis and coccidioidomycosis. In the setting of immunosuppression, the diagnosis of hyperkeratotic MC was favored in our patient given the co-location of classic umbilicated MC lesions with the hyperkeratotic papules and nodules. It is common to see MC autoinoculated in the beard area in men from shaving, as well as for MC to present in an atypical manner, particularly as hyperkeratotic lesions, in patients with AIDS.4 The predominant localized beard distribution and lack of other mucocutaneous manifestations of SS at presentation supported a clinical diagnosis of hyperkeratotic MC in our patient.

Unique presentations of SS have been documented, including nodular lesions of the face, but they typically have been accompanied by other stigmata of SS such as the classic palmoplantar or truncal maculopapular rash.3 One notable difference in our case was the localized beard distribution of the syphilitic cutaneous lesions in a man with AIDS. Our case reinforces the importance of cutaneous biopsies in immunocompromised patients. It is known that SS spreads hematogenously; however, in our case it was suspected that the new lesions may have spread locally through autoinoculation via beard hair removal, as the hyperkeratotic lesions were limited to the beard area. Koebnerization secondary to trauma induced by beard hair removal was considered in this case; however, koebnerization is known to occur in noninfectious dermatologic conditions, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and vitiligo, but not in infections such as syphilis. Our case is pivotal in raising the question of whether SS can be autoinoculated in the beard area.

- Baughn RE, Musher DM. Secondary syphilitic lesions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:205-216.

- Dourmishev LA, Dourmishev AL. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Cohen SE, Klausner JD, Engelman J, et al. Syphilis in the modern era: an update for physicians. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27:705-722.

- Filo-Rogulska M, Pindycka-Plaszcznska M, Januszewski K, et al. Disseminated atypical molluscum contagiosum as a presenting symptom of HIV infection. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:56-58.

- Baughn RE, Musher DM. Secondary syphilitic lesions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:205-216.

- Dourmishev LA, Dourmishev AL. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Cohen SE, Klausner JD, Engelman J, et al. Syphilis in the modern era: an update for physicians. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27:705-722.

- Filo-Rogulska M, Pindycka-Plaszcznska M, Januszewski K, et al. Disseminated atypical molluscum contagiosum as a presenting symptom of HIV infection. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:56-58.

Practice Points

- Recognize typical and atypical presentations of secondary syphilis (SS).

- This case reinforces the importance of cutaneous biopsies in immunocompromised patients.

- Consider the possibility of autoinoculation in SS.

Partially Blanchable Violaceous Lesions in an AIDS Patient

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Disseminated Kaposi Sarcoma

There are 5 types of Kaposi sarcoma (KS): classic KS, African cutaneous KS, African lymphadenopathic KS, AIDS-related KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS. Immunosuppression-associated KS can occur in the setting of lymphoma or in conjunction with immunosuppressive therapy related to organ transplants and long-term corticosteroid treatment.1,2 Kaposi sarcoma associated with highly active antiretroviral therapy–induced immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome also may occur.3

The possible causes of the manifestation of KS in our patient were 2-fold: (1) AIDS associated given the patient’s CD4 lymphocyte count of 7 cells/mm3, and (2) iatrogenic secondary to drug-induced immunosuppression that was temporally induced by 2 sustained periods of intravenous dexamethasone for cerebral edema in the setting of primary central nervous system lymphoma. It is unlikely that our patient experienced immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome–induced KS, as the dysphagia interfered with the ability to take antiretroviral therapy during hospitalization. In patients who have experienced KS in the setting of steroid use or organ transplantation, KS lesions spontaneously improved or completely regressed several months after immunosuppression reduction or removal.1,2,4

Clinically and morphologically, our patient also clearly demonstrated the occasionally seen striking manifestation of perilesional, ecchymotic-appearing or bruiselike halos surrounding the KS lesions (Figure).

The initial differential diagnosis included hemorrhagic diathesis but later included KS in the setting of AIDS and immunosuppressive therapy with dexamethasone, bacillary angiomatosis, and cutaneous lymphoma. A biopsy of one of the cutaneous lesions confirmed the diagnosis of KS.

Three standard treatments of primary central nervous system lymphoma currently exist: radiation therapy, intrathecal and/or intraventricular chemotherapy, and steroid therapy.5 Given the patient’s risk for opportunistic infections and immunodeficient state, the medical team was constrained in its treatment options, as all of the therapies would further weaken the patient’s immune system.

Treatment of KS can be local and/or systemic based on disease stage, progression, distribution, clinical type, and immune status.6,7 Our patient had generalized cutaneous KS covering more than 50% of the body, thus making local treatments such as radiation therapy, cryotherapy, intralesional chemotherapy with vincristine or vinblastine, excision, laser therapy, or alitretinoin gel impractical. Single- or multiple-agent systemic treatment options for disseminated cutaneous disease with or without internal organ involvement may include liposomal anthracyclines, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, vinblastine, vincristine, bleomycin, etoposide, and interferon-alfa.6,7 Potent combination antiretroviral therapy is the mainstay for treatment of AIDS-associated KS.8

- Nassar D, Schartz NEC, Bouche C, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma after long-acting steroids: time until remission and drug washout. Dermatology. 2010;220:159-163.

- Trattner A, Hodak E, David M, et al. The appearance of Kaposi sarcoma during corticosteroid therapy. Cancer. 1993;72:1779-1783.

- Bower M, Nelson M, Young AM, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5224-5228.

- Duman S, Töz H, Aşçi G, et al. Successful treatment of post-transplant Kaposi’s sarcoma by reduction of immunosuppression. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:892-896.

- National Cancer Institute. Primary CNS lymphoma treatment. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/primary-CNS-lymphoma/Patient/page4. Accessed June 10, 2014.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206.

- Lee F-C, Mitsuyasu RT. Chemotherapy of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1996;10:1051-1068.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Disseminated Kaposi Sarcoma

There are 5 types of Kaposi sarcoma (KS): classic KS, African cutaneous KS, African lymphadenopathic KS, AIDS-related KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS. Immunosuppression-associated KS can occur in the setting of lymphoma or in conjunction with immunosuppressive therapy related to organ transplants and long-term corticosteroid treatment.1,2 Kaposi sarcoma associated with highly active antiretroviral therapy–induced immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome also may occur.3

The possible causes of the manifestation of KS in our patient were 2-fold: (1) AIDS associated given the patient’s CD4 lymphocyte count of 7 cells/mm3, and (2) iatrogenic secondary to drug-induced immunosuppression that was temporally induced by 2 sustained periods of intravenous dexamethasone for cerebral edema in the setting of primary central nervous system lymphoma. It is unlikely that our patient experienced immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome–induced KS, as the dysphagia interfered with the ability to take antiretroviral therapy during hospitalization. In patients who have experienced KS in the setting of steroid use or organ transplantation, KS lesions spontaneously improved or completely regressed several months after immunosuppression reduction or removal.1,2,4

Clinically and morphologically, our patient also clearly demonstrated the occasionally seen striking manifestation of perilesional, ecchymotic-appearing or bruiselike halos surrounding the KS lesions (Figure).

The initial differential diagnosis included hemorrhagic diathesis but later included KS in the setting of AIDS and immunosuppressive therapy with dexamethasone, bacillary angiomatosis, and cutaneous lymphoma. A biopsy of one of the cutaneous lesions confirmed the diagnosis of KS.

Three standard treatments of primary central nervous system lymphoma currently exist: radiation therapy, intrathecal and/or intraventricular chemotherapy, and steroid therapy.5 Given the patient’s risk for opportunistic infections and immunodeficient state, the medical team was constrained in its treatment options, as all of the therapies would further weaken the patient’s immune system.

Treatment of KS can be local and/or systemic based on disease stage, progression, distribution, clinical type, and immune status.6,7 Our patient had generalized cutaneous KS covering more than 50% of the body, thus making local treatments such as radiation therapy, cryotherapy, intralesional chemotherapy with vincristine or vinblastine, excision, laser therapy, or alitretinoin gel impractical. Single- or multiple-agent systemic treatment options for disseminated cutaneous disease with or without internal organ involvement may include liposomal anthracyclines, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, vinblastine, vincristine, bleomycin, etoposide, and interferon-alfa.6,7 Potent combination antiretroviral therapy is the mainstay for treatment of AIDS-associated KS.8

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Disseminated Kaposi Sarcoma

There are 5 types of Kaposi sarcoma (KS): classic KS, African cutaneous KS, African lymphadenopathic KS, AIDS-related KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS. Immunosuppression-associated KS can occur in the setting of lymphoma or in conjunction with immunosuppressive therapy related to organ transplants and long-term corticosteroid treatment.1,2 Kaposi sarcoma associated with highly active antiretroviral therapy–induced immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome also may occur.3

The possible causes of the manifestation of KS in our patient were 2-fold: (1) AIDS associated given the patient’s CD4 lymphocyte count of 7 cells/mm3, and (2) iatrogenic secondary to drug-induced immunosuppression that was temporally induced by 2 sustained periods of intravenous dexamethasone for cerebral edema in the setting of primary central nervous system lymphoma. It is unlikely that our patient experienced immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome–induced KS, as the dysphagia interfered with the ability to take antiretroviral therapy during hospitalization. In patients who have experienced KS in the setting of steroid use or organ transplantation, KS lesions spontaneously improved or completely regressed several months after immunosuppression reduction or removal.1,2,4

Clinically and morphologically, our patient also clearly demonstrated the occasionally seen striking manifestation of perilesional, ecchymotic-appearing or bruiselike halos surrounding the KS lesions (Figure).

The initial differential diagnosis included hemorrhagic diathesis but later included KS in the setting of AIDS and immunosuppressive therapy with dexamethasone, bacillary angiomatosis, and cutaneous lymphoma. A biopsy of one of the cutaneous lesions confirmed the diagnosis of KS.

Three standard treatments of primary central nervous system lymphoma currently exist: radiation therapy, intrathecal and/or intraventricular chemotherapy, and steroid therapy.5 Given the patient’s risk for opportunistic infections and immunodeficient state, the medical team was constrained in its treatment options, as all of the therapies would further weaken the patient’s immune system.

Treatment of KS can be local and/or systemic based on disease stage, progression, distribution, clinical type, and immune status.6,7 Our patient had generalized cutaneous KS covering more than 50% of the body, thus making local treatments such as radiation therapy, cryotherapy, intralesional chemotherapy with vincristine or vinblastine, excision, laser therapy, or alitretinoin gel impractical. Single- or multiple-agent systemic treatment options for disseminated cutaneous disease with or without internal organ involvement may include liposomal anthracyclines, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, vinblastine, vincristine, bleomycin, etoposide, and interferon-alfa.6,7 Potent combination antiretroviral therapy is the mainstay for treatment of AIDS-associated KS.8

- Nassar D, Schartz NEC, Bouche C, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma after long-acting steroids: time until remission and drug washout. Dermatology. 2010;220:159-163.

- Trattner A, Hodak E, David M, et al. The appearance of Kaposi sarcoma during corticosteroid therapy. Cancer. 1993;72:1779-1783.

- Bower M, Nelson M, Young AM, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5224-5228.

- Duman S, Töz H, Aşçi G, et al. Successful treatment of post-transplant Kaposi’s sarcoma by reduction of immunosuppression. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:892-896.

- National Cancer Institute. Primary CNS lymphoma treatment. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/primary-CNS-lymphoma/Patient/page4. Accessed June 10, 2014.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206.

- Lee F-C, Mitsuyasu RT. Chemotherapy of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1996;10:1051-1068.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

- Nassar D, Schartz NEC, Bouche C, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma after long-acting steroids: time until remission and drug washout. Dermatology. 2010;220:159-163.

- Trattner A, Hodak E, David M, et al. The appearance of Kaposi sarcoma during corticosteroid therapy. Cancer. 1993;72:1779-1783.

- Bower M, Nelson M, Young AM, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5224-5228.

- Duman S, Töz H, Aşçi G, et al. Successful treatment of post-transplant Kaposi’s sarcoma by reduction of immunosuppression. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:892-896.

- National Cancer Institute. Primary CNS lymphoma treatment. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/primary-CNS-lymphoma/Patient/page4. Accessed June 10, 2014.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206.

- Lee F-C, Mitsuyasu RT. Chemotherapy of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1996;10:1051-1068.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

A 37-year-old AIDS patient (CD4 lymphocyte count, 7 cells/mm3 [reference range, 500–1000 cells/mm3]; viral load, >200,000 copies/mL) with a medical history of primary central nervous system lymphoma and recent Salmonella bacteremia was admitted with a 1-week history of dysphagia, generalized weakness, and a 15-lb weight loss over a 2-month period. Medications included prophylaxis with weekly azithromycin and daily atovoquone. The patient had a history of noncompliance with antiretroviral therapy, which included atazanavir sulfate, lamivudine, and zidovudine. One month prior to presentation the patient received a course of intravenous dexamethasone for cerebral edema secondary to mass effect from primary central nervous system lymphoma. On examination the patient was afebrile, cachectic, and in no acute distress. Initially, faint petechial lesions were noted on the torso and upper abdomen. Over the course of 10 days, after reintroduction of intravenous dexamethasone, the patient rapidly and diffusely developed partially blanchable, violaceous macules, patches, papules, and plaques that were most prominent on the trunk and lower extremities. Some of the lesions were surrounded by nonblanchable, yellowish brown, ecchymotic-appearing halos. Lesions spared the oral mucosa, face, and genitalia. There was no evidence of mucocutaneous involvement.