User login

This Is No Measly Rash

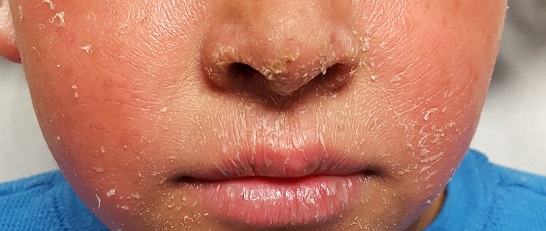

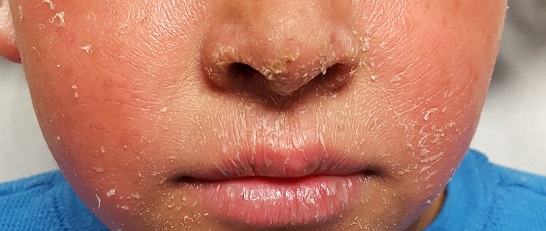

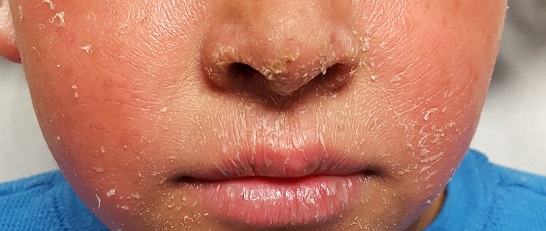

A 7-year-old girl is urgently referred to dermatology for a rash of several weeks’ duration. It is the rash itself, rather than any related symptoms, that frightens the family; the possibility of measles (raised by their primary care provider) compounded their concern. Antifungal cream (clotrimazole) has been of no help.

Physically, the child feels fine, without fever or malaise. But further questioning reveals that she was diagnosed with and treated for strep throat “about a month before” the rash developed.

The child was recently adopted by her aunt and uncle after her parents were killed in an automobile accident. This, understandably, has caused her to fall behind in school. She has no pets, no siblings, and no family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

Numerous discrete, round papules and plaques are distributed very evenly on the trunk. They are uniformly scaly and pink, measuring 2 to 3 cm each. In addition, several areas of thick, white, tenacious scaling are seen in the scalp.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and nails are free of any notable change.

What is the diagnosis?

This is a typical case of guttate psoriasis, which is genetic in predisposition but triggered by strep in the susceptible patient. It’s tempting to partially attribute this case to the child’s high stress level, but this is purely speculative.

Psoriasis affects about 7 million people in the US—more than 150 million worldwide—in a variety of forms. The guttate morphology is seen primarily in children, with plaques that favor extensor surfaces of the arms, trunk, and legs. Biopsy was not needed in this case; if performed, it would have shown characteristic changes (eg, parakeratosis, fusing of rete ridges).

These changes occur because psoriasis, an autoimmune disease, targets keratinocytes—cells that regenerate over a 28-day period to replace the outer layer of skin as it flakes off. With psoriasis, this process is accelerated; keratinocytes move and slough off within a week, creating scaly, inflamed lesions.

Long-term follow-up is needed to monitor the patient’s overall health, because psoriasis increases comorbidity of conditions such as coronary vessel disease, diabetes, stroke, and cancer. In patients with any form of psoriasis, there is the potential for psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive, crippling form of arthropathy that affects up to 25% of all patients. And in a third of guttate psoriasis cases, the condition evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. For this reason, the guttate variety must be treated aggressively with a combination of phototherapy and topical steroids, adequate treatment of any residual strep, and, in adults, the occasional addition of methotrexate.

Regarding the family’s concern, measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause other constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia). The other item in the differential, tinea corporis, involves lesions that are not as uniformly scaly, numerous, or evenly spaced. And with tinea, scaling typically occurs on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Guttate psoriasis is more common in children than in adults and is often triggered by strep infection, though stress has also been implicated as a trigger.

- In about a third of all cases, this type evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. All patients with psoriasis are at risk for psoriatic arthropathy (25% of patients).

- Measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia).

- Tinea corporis lesions are not uniformly scaly, nor would they be as numerous or evenly spaced; most of the scale in tinea is seen on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

A 7-year-old girl is urgently referred to dermatology for a rash of several weeks’ duration. It is the rash itself, rather than any related symptoms, that frightens the family; the possibility of measles (raised by their primary care provider) compounded their concern. Antifungal cream (clotrimazole) has been of no help.

Physically, the child feels fine, without fever or malaise. But further questioning reveals that she was diagnosed with and treated for strep throat “about a month before” the rash developed.

The child was recently adopted by her aunt and uncle after her parents were killed in an automobile accident. This, understandably, has caused her to fall behind in school. She has no pets, no siblings, and no family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

Numerous discrete, round papules and plaques are distributed very evenly on the trunk. They are uniformly scaly and pink, measuring 2 to 3 cm each. In addition, several areas of thick, white, tenacious scaling are seen in the scalp.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and nails are free of any notable change.

What is the diagnosis?

This is a typical case of guttate psoriasis, which is genetic in predisposition but triggered by strep in the susceptible patient. It’s tempting to partially attribute this case to the child’s high stress level, but this is purely speculative.

Psoriasis affects about 7 million people in the US—more than 150 million worldwide—in a variety of forms. The guttate morphology is seen primarily in children, with plaques that favor extensor surfaces of the arms, trunk, and legs. Biopsy was not needed in this case; if performed, it would have shown characteristic changes (eg, parakeratosis, fusing of rete ridges).

These changes occur because psoriasis, an autoimmune disease, targets keratinocytes—cells that regenerate over a 28-day period to replace the outer layer of skin as it flakes off. With psoriasis, this process is accelerated; keratinocytes move and slough off within a week, creating scaly, inflamed lesions.

Long-term follow-up is needed to monitor the patient’s overall health, because psoriasis increases comorbidity of conditions such as coronary vessel disease, diabetes, stroke, and cancer. In patients with any form of psoriasis, there is the potential for psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive, crippling form of arthropathy that affects up to 25% of all patients. And in a third of guttate psoriasis cases, the condition evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. For this reason, the guttate variety must be treated aggressively with a combination of phototherapy and topical steroids, adequate treatment of any residual strep, and, in adults, the occasional addition of methotrexate.

Regarding the family’s concern, measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause other constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia). The other item in the differential, tinea corporis, involves lesions that are not as uniformly scaly, numerous, or evenly spaced. And with tinea, scaling typically occurs on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Guttate psoriasis is more common in children than in adults and is often triggered by strep infection, though stress has also been implicated as a trigger.

- In about a third of all cases, this type evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. All patients with psoriasis are at risk for psoriatic arthropathy (25% of patients).

- Measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia).

- Tinea corporis lesions are not uniformly scaly, nor would they be as numerous or evenly spaced; most of the scale in tinea is seen on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

A 7-year-old girl is urgently referred to dermatology for a rash of several weeks’ duration. It is the rash itself, rather than any related symptoms, that frightens the family; the possibility of measles (raised by their primary care provider) compounded their concern. Antifungal cream (clotrimazole) has been of no help.

Physically, the child feels fine, without fever or malaise. But further questioning reveals that she was diagnosed with and treated for strep throat “about a month before” the rash developed.

The child was recently adopted by her aunt and uncle after her parents were killed in an automobile accident. This, understandably, has caused her to fall behind in school. She has no pets, no siblings, and no family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

Numerous discrete, round papules and plaques are distributed very evenly on the trunk. They are uniformly scaly and pink, measuring 2 to 3 cm each. In addition, several areas of thick, white, tenacious scaling are seen in the scalp.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and nails are free of any notable change.

What is the diagnosis?

This is a typical case of guttate psoriasis, which is genetic in predisposition but triggered by strep in the susceptible patient. It’s tempting to partially attribute this case to the child’s high stress level, but this is purely speculative.

Psoriasis affects about 7 million people in the US—more than 150 million worldwide—in a variety of forms. The guttate morphology is seen primarily in children, with plaques that favor extensor surfaces of the arms, trunk, and legs. Biopsy was not needed in this case; if performed, it would have shown characteristic changes (eg, parakeratosis, fusing of rete ridges).

These changes occur because psoriasis, an autoimmune disease, targets keratinocytes—cells that regenerate over a 28-day period to replace the outer layer of skin as it flakes off. With psoriasis, this process is accelerated; keratinocytes move and slough off within a week, creating scaly, inflamed lesions.

Long-term follow-up is needed to monitor the patient’s overall health, because psoriasis increases comorbidity of conditions such as coronary vessel disease, diabetes, stroke, and cancer. In patients with any form of psoriasis, there is the potential for psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive, crippling form of arthropathy that affects up to 25% of all patients. And in a third of guttate psoriasis cases, the condition evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. For this reason, the guttate variety must be treated aggressively with a combination of phototherapy and topical steroids, adequate treatment of any residual strep, and, in adults, the occasional addition of methotrexate.

Regarding the family’s concern, measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause other constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia). The other item in the differential, tinea corporis, involves lesions that are not as uniformly scaly, numerous, or evenly spaced. And with tinea, scaling typically occurs on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Guttate psoriasis is more common in children than in adults and is often triggered by strep infection, though stress has also been implicated as a trigger.

- In about a third of all cases, this type evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. All patients with psoriasis are at risk for psoriatic arthropathy (25% of patients).

- Measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia).

- Tinea corporis lesions are not uniformly scaly, nor would they be as numerous or evenly spaced; most of the scale in tinea is seen on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

Can’t Quite Put My Finger On It …

ANSWER

The correct answer is perform a shave biopsy (choice “c”). It is a bedrock principle in dermatology that there is no substitute for a correct diagnosis, because correct diagnosis dictates proper treatment. When practical, biopsy is an excellent way to establish the true nature of a lesion and rule out other possibilities; it cuts through all conjecture.

DISCUSSION

The report showed intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma, also known as Bowen disease. In this case, overexposure to the sun was the probable cause; however, Bowen disease can also develop from non–UV-related triggers, including human papillomavirus, arsenic (usually in contaminated ground water), and radiation treatment.

The differential includes psoriasis (which waxes and wanes), fungal infection (unlikely to last 10 years with so little growth), and superficial basal cell carcinoma.

Treatment success can be achieved by electrodessication and curettage or by the application of 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod cream for a month or two. Rarely, Bowen lesions can become invasive and metastasize if left untreated.

This patient’s prognosis, however, is excellent—at least, as far as this lesion is concerned. His history of sun exposure and numerous skin cancers

ANSWER

The correct answer is perform a shave biopsy (choice “c”). It is a bedrock principle in dermatology that there is no substitute for a correct diagnosis, because correct diagnosis dictates proper treatment. When practical, biopsy is an excellent way to establish the true nature of a lesion and rule out other possibilities; it cuts through all conjecture.

DISCUSSION

The report showed intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma, also known as Bowen disease. In this case, overexposure to the sun was the probable cause; however, Bowen disease can also develop from non–UV-related triggers, including human papillomavirus, arsenic (usually in contaminated ground water), and radiation treatment.

The differential includes psoriasis (which waxes and wanes), fungal infection (unlikely to last 10 years with so little growth), and superficial basal cell carcinoma.

Treatment success can be achieved by electrodessication and curettage or by the application of 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod cream for a month or two. Rarely, Bowen lesions can become invasive and metastasize if left untreated.

This patient’s prognosis, however, is excellent—at least, as far as this lesion is concerned. His history of sun exposure and numerous skin cancers

ANSWER

The correct answer is perform a shave biopsy (choice “c”). It is a bedrock principle in dermatology that there is no substitute for a correct diagnosis, because correct diagnosis dictates proper treatment. When practical, biopsy is an excellent way to establish the true nature of a lesion and rule out other possibilities; it cuts through all conjecture.

DISCUSSION

The report showed intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma, also known as Bowen disease. In this case, overexposure to the sun was the probable cause; however, Bowen disease can also develop from non–UV-related triggers, including human papillomavirus, arsenic (usually in contaminated ground water), and radiation treatment.

The differential includes psoriasis (which waxes and wanes), fungal infection (unlikely to last 10 years with so little growth), and superficial basal cell carcinoma.

Treatment success can be achieved by electrodessication and curettage or by the application of 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod cream for a month or two. Rarely, Bowen lesions can become invasive and metastasize if left untreated.

This patient’s prognosis, however, is excellent—at least, as far as this lesion is concerned. His history of sun exposure and numerous skin cancers

For at least 10 years, a now 70-year-old man has had a lesion on his left third finger. It is asymptomatic but gradually growing larger. Various primary care providers have offered diagnoses, the most recent being “fungal infection,” but treatments including nystatin cream have had no good effect.

The oval, pink, scaly lesion is located on the medial aspect of the proximal phalanx of the patient’s left hand; it measures 2.3 cm with well-defined borders. It is barely palpable and is not at all tender. No nodes can be felt in the arm or axilla.

The patient is otherwise healthy and is not immunosuppressed. His skin elsewhere shows evidence of sun damage—including actinic keratosis, solar lentigines, and telangiectasias—and removal of several basal cell carcinomas from his face and arms. His elbows, knees, scalp, and nails are free of any notable skin changes.

Hitting a Rough Patch

Since they appeared in early childhood, the lesions on this 50-year-old woman’s arms have waxed and waned, becoming most noticeable in the winter. Although they are generally asymptomatic, the patient is bothered by their rough feel. She admits to picking at them, which causes further irritation. Moisturizers have provided some (temporary) relief.

The patient’s mother and sister have similar lesions, as well as very sensitive skin that overreacts to contactants. The entire family is markedly atopic, with seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema.

EXAMINATION

The bumps can be seen on the deltoids, triceps, back, and anterior thighs but are particularly prominent on a small area of skin on the patient’s left triceps. The posterior third of both cheeks, which are faintly red, is mildly affected. Overall, glabrous (nonhairy) areas are completely spared.

The individual papules are hyperkeratotic, measure a millimeter or less, and are follicular. Many are faintly erythematous; when picked away, several reveal a coiled hair inside the papule.

What is the diagnosis?

One of the most common dermatologic conditions encountered in medical practice, keratosis pilaris (KP) affects 30% to 50% of the population. KP is an autosomal dominant disorder; the lesions are caused by an inherited overabundance of keratin around follicular orifices, which often precludes the ability of the hair to exit the follicle. The hairs keep growing, but curl up inside the keratotic papule. Fortunately, aside from mild irritation, KP is essentially asymptomatic.

It has a broad range of presentations, from mild to severe. Some children present with a few barely palpable keratotic papules limited to the bilateral triceps, while others have thousands of papules and large patches of prominent follicles that also involve extensor surfaces of hair-bearing skin. Another version of KP, rubra faceii, is distinguished by very red cheeks with keratotic follicular papules; the unwary provider may suspect acne, but that condition presents with comedones and/or a combination of papules, pustules, or cysts confined to sebaceous (oily) areas. The differential also includes Darier disease (keratosis follicularis), but this has a completely different distribution.

KP is often seen in conjunction with atopic stigmata such as eczema, seasonal allergies, xerosis, asthma, and urticaria. It is believed by some to be a marker for atopy.

Treatment is unsatisfactory in terms of a cure, though most patients see their disease lessen over time. Emollients (heavy moisturizers) containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, or retinoic acid can minimize the height of the papules and smooth the skin, but they do not provide a long-term solution.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is an extremely common autosomal dominant condition that affects 30% to 50% of children.

- It manifests very early in life with tiny, hyperkeratotic, follicular papules in a characteristic distribution.

- The bilateral posterior triceps, deltoids, anterior thighs, buttocks, and face are typically affected, while glabrous skin is spared.

- Treatment is difficult; KP responds to emollients and keratolytics containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, and retinoic acid—but any relief will be temporary.

Since they appeared in early childhood, the lesions on this 50-year-old woman’s arms have waxed and waned, becoming most noticeable in the winter. Although they are generally asymptomatic, the patient is bothered by their rough feel. She admits to picking at them, which causes further irritation. Moisturizers have provided some (temporary) relief.

The patient’s mother and sister have similar lesions, as well as very sensitive skin that overreacts to contactants. The entire family is markedly atopic, with seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema.

EXAMINATION

The bumps can be seen on the deltoids, triceps, back, and anterior thighs but are particularly prominent on a small area of skin on the patient’s left triceps. The posterior third of both cheeks, which are faintly red, is mildly affected. Overall, glabrous (nonhairy) areas are completely spared.

The individual papules are hyperkeratotic, measure a millimeter or less, and are follicular. Many are faintly erythematous; when picked away, several reveal a coiled hair inside the papule.

What is the diagnosis?

One of the most common dermatologic conditions encountered in medical practice, keratosis pilaris (KP) affects 30% to 50% of the population. KP is an autosomal dominant disorder; the lesions are caused by an inherited overabundance of keratin around follicular orifices, which often precludes the ability of the hair to exit the follicle. The hairs keep growing, but curl up inside the keratotic papule. Fortunately, aside from mild irritation, KP is essentially asymptomatic.

It has a broad range of presentations, from mild to severe. Some children present with a few barely palpable keratotic papules limited to the bilateral triceps, while others have thousands of papules and large patches of prominent follicles that also involve extensor surfaces of hair-bearing skin. Another version of KP, rubra faceii, is distinguished by very red cheeks with keratotic follicular papules; the unwary provider may suspect acne, but that condition presents with comedones and/or a combination of papules, pustules, or cysts confined to sebaceous (oily) areas. The differential also includes Darier disease (keratosis follicularis), but this has a completely different distribution.

KP is often seen in conjunction with atopic stigmata such as eczema, seasonal allergies, xerosis, asthma, and urticaria. It is believed by some to be a marker for atopy.

Treatment is unsatisfactory in terms of a cure, though most patients see their disease lessen over time. Emollients (heavy moisturizers) containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, or retinoic acid can minimize the height of the papules and smooth the skin, but they do not provide a long-term solution.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is an extremely common autosomal dominant condition that affects 30% to 50% of children.

- It manifests very early in life with tiny, hyperkeratotic, follicular papules in a characteristic distribution.

- The bilateral posterior triceps, deltoids, anterior thighs, buttocks, and face are typically affected, while glabrous skin is spared.

- Treatment is difficult; KP responds to emollients and keratolytics containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, and retinoic acid—but any relief will be temporary.

Since they appeared in early childhood, the lesions on this 50-year-old woman’s arms have waxed and waned, becoming most noticeable in the winter. Although they are generally asymptomatic, the patient is bothered by their rough feel. She admits to picking at them, which causes further irritation. Moisturizers have provided some (temporary) relief.

The patient’s mother and sister have similar lesions, as well as very sensitive skin that overreacts to contactants. The entire family is markedly atopic, with seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema.

EXAMINATION

The bumps can be seen on the deltoids, triceps, back, and anterior thighs but are particularly prominent on a small area of skin on the patient’s left triceps. The posterior third of both cheeks, which are faintly red, is mildly affected. Overall, glabrous (nonhairy) areas are completely spared.

The individual papules are hyperkeratotic, measure a millimeter or less, and are follicular. Many are faintly erythematous; when picked away, several reveal a coiled hair inside the papule.

What is the diagnosis?

One of the most common dermatologic conditions encountered in medical practice, keratosis pilaris (KP) affects 30% to 50% of the population. KP is an autosomal dominant disorder; the lesions are caused by an inherited overabundance of keratin around follicular orifices, which often precludes the ability of the hair to exit the follicle. The hairs keep growing, but curl up inside the keratotic papule. Fortunately, aside from mild irritation, KP is essentially asymptomatic.

It has a broad range of presentations, from mild to severe. Some children present with a few barely palpable keratotic papules limited to the bilateral triceps, while others have thousands of papules and large patches of prominent follicles that also involve extensor surfaces of hair-bearing skin. Another version of KP, rubra faceii, is distinguished by very red cheeks with keratotic follicular papules; the unwary provider may suspect acne, but that condition presents with comedones and/or a combination of papules, pustules, or cysts confined to sebaceous (oily) areas. The differential also includes Darier disease (keratosis follicularis), but this has a completely different distribution.

KP is often seen in conjunction with atopic stigmata such as eczema, seasonal allergies, xerosis, asthma, and urticaria. It is believed by some to be a marker for atopy.

Treatment is unsatisfactory in terms of a cure, though most patients see their disease lessen over time. Emollients (heavy moisturizers) containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, or retinoic acid can minimize the height of the papules and smooth the skin, but they do not provide a long-term solution.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is an extremely common autosomal dominant condition that affects 30% to 50% of children.

- It manifests very early in life with tiny, hyperkeratotic, follicular papules in a characteristic distribution.

- The bilateral posterior triceps, deltoids, anterior thighs, buttocks, and face are typically affected, while glabrous skin is spared.

- Treatment is difficult; KP responds to emollients and keratolytics containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, and retinoic acid—but any relief will be temporary.

She's Losing It—Her Hair, That Is

Following the stressful divorce of her parents, this 8-year-old girl’s hair began to fall out, prompting her referral to dermatology. Along with the hair loss, she has mild itching and burning in the area.

The child has a history of several atopic phenomena, including seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema—all of which are replete in her family’s history.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no distress and is quite willing to show the affected area—a sizeable (10 x 8 cm), roughly round area of complete hair loss involving the nuchal periphery of her scalp. Fortunately, the area is covered by longer hair that drapes down.

No epidermal changes (ie, redness, scaling, edema) are seen, and no nodes are palpable in the area. Her arms, brows, and lashes appear normal after careful examination.

What is the diagnosis?

Alopecia areata (AA) is quite common, especially among children, and affects both genders equally. It appears to be stress-related and can manifest in many forms. This particular type, with its distinguishing features of large size and peripheral involvement of the scalp margin, is known as ophiasis.

However, the real significance of ophiasis is its uncertain prognosis. For this patient, the extent and type of hair loss, her young age, and her atopic history all predict a poor prognosis. The hair loss is likely to be slow to resolve, if it does at all. It could progress to loss of all scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or every hair on her body (alopecia universalis).

Compounding the problem is the fact that no good treatment exists for this autoimmune disease, which affects those with genetic predisposition. Topical steroid application or intralesional steroid injections (3 to 5 mg/cc triamcinolone suspension) can promote the growth of a few hairs, but neither have an effect on the ultimate outcome. There have been reports of benefit from injectable biologics and oral antimalarials, but these medications have not been approved for use in AA.

Histopathologic studies with special stains show a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding the hair follicle that prevents the growth of new hairs. Glucocorticoids (eg, prednisone) resolve this and allow new hair growth, but the treatment must be continued for months with unjustifiable adverse effects. Even then, full resolution must come on its own.

This patient was treated with a month-long course of topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream. But as stated above, her prognosis is somewhat guarded.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune process and a common cause of localized hair loss.

- This hair loss is usually acute, complete, and round, and is often seen in multiple patches.

- Of the many forms of AA, this one (ophiasis) has a less certain prognosis, worsened by youth, atopy, and lesion size.

- While ordinary AA resolves on its own in most cases, ophiasis can progress into total loss of scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or loss of all body hair (alopecia universalis).

Following the stressful divorce of her parents, this 8-year-old girl’s hair began to fall out, prompting her referral to dermatology. Along with the hair loss, she has mild itching and burning in the area.

The child has a history of several atopic phenomena, including seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema—all of which are replete in her family’s history.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no distress and is quite willing to show the affected area—a sizeable (10 x 8 cm), roughly round area of complete hair loss involving the nuchal periphery of her scalp. Fortunately, the area is covered by longer hair that drapes down.

No epidermal changes (ie, redness, scaling, edema) are seen, and no nodes are palpable in the area. Her arms, brows, and lashes appear normal after careful examination.

What is the diagnosis?

Alopecia areata (AA) is quite common, especially among children, and affects both genders equally. It appears to be stress-related and can manifest in many forms. This particular type, with its distinguishing features of large size and peripheral involvement of the scalp margin, is known as ophiasis.

However, the real significance of ophiasis is its uncertain prognosis. For this patient, the extent and type of hair loss, her young age, and her atopic history all predict a poor prognosis. The hair loss is likely to be slow to resolve, if it does at all. It could progress to loss of all scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or every hair on her body (alopecia universalis).

Compounding the problem is the fact that no good treatment exists for this autoimmune disease, which affects those with genetic predisposition. Topical steroid application or intralesional steroid injections (3 to 5 mg/cc triamcinolone suspension) can promote the growth of a few hairs, but neither have an effect on the ultimate outcome. There have been reports of benefit from injectable biologics and oral antimalarials, but these medications have not been approved for use in AA.

Histopathologic studies with special stains show a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding the hair follicle that prevents the growth of new hairs. Glucocorticoids (eg, prednisone) resolve this and allow new hair growth, but the treatment must be continued for months with unjustifiable adverse effects. Even then, full resolution must come on its own.

This patient was treated with a month-long course of topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream. But as stated above, her prognosis is somewhat guarded.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune process and a common cause of localized hair loss.

- This hair loss is usually acute, complete, and round, and is often seen in multiple patches.

- Of the many forms of AA, this one (ophiasis) has a less certain prognosis, worsened by youth, atopy, and lesion size.

- While ordinary AA resolves on its own in most cases, ophiasis can progress into total loss of scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or loss of all body hair (alopecia universalis).

Following the stressful divorce of her parents, this 8-year-old girl’s hair began to fall out, prompting her referral to dermatology. Along with the hair loss, she has mild itching and burning in the area.

The child has a history of several atopic phenomena, including seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema—all of which are replete in her family’s history.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no distress and is quite willing to show the affected area—a sizeable (10 x 8 cm), roughly round area of complete hair loss involving the nuchal periphery of her scalp. Fortunately, the area is covered by longer hair that drapes down.

No epidermal changes (ie, redness, scaling, edema) are seen, and no nodes are palpable in the area. Her arms, brows, and lashes appear normal after careful examination.

What is the diagnosis?

Alopecia areata (AA) is quite common, especially among children, and affects both genders equally. It appears to be stress-related and can manifest in many forms. This particular type, with its distinguishing features of large size and peripheral involvement of the scalp margin, is known as ophiasis.

However, the real significance of ophiasis is its uncertain prognosis. For this patient, the extent and type of hair loss, her young age, and her atopic history all predict a poor prognosis. The hair loss is likely to be slow to resolve, if it does at all. It could progress to loss of all scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or every hair on her body (alopecia universalis).

Compounding the problem is the fact that no good treatment exists for this autoimmune disease, which affects those with genetic predisposition. Topical steroid application or intralesional steroid injections (3 to 5 mg/cc triamcinolone suspension) can promote the growth of a few hairs, but neither have an effect on the ultimate outcome. There have been reports of benefit from injectable biologics and oral antimalarials, but these medications have not been approved for use in AA.

Histopathologic studies with special stains show a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding the hair follicle that prevents the growth of new hairs. Glucocorticoids (eg, prednisone) resolve this and allow new hair growth, but the treatment must be continued for months with unjustifiable adverse effects. Even then, full resolution must come on its own.

This patient was treated with a month-long course of topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream. But as stated above, her prognosis is somewhat guarded.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune process and a common cause of localized hair loss.

- This hair loss is usually acute, complete, and round, and is often seen in multiple patches.

- Of the many forms of AA, this one (ophiasis) has a less certain prognosis, worsened by youth, atopy, and lesion size.

- While ordinary AA resolves on its own in most cases, ophiasis can progress into total loss of scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or loss of all body hair (alopecia universalis).

There’s More Where That Came From

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (choice “d”).

Virtually all patients with this condition believe that they have a terrible case of “ringworm” (ie, fungal infection; choice “a”)—an opinion all too often corroborated by the medical provider unacquainted with pityriasis rosea. The two can be difficult to distinguish, but the “herald” patch, oval shape, odd color, and fine scale all serve to confirm the diagnosis. When necessary, a KOH prep or biopsy can be done.

Psoriasis (choice “b”) can manifest acutely, but it is distinctly salmon-pink under coarse, white scale that affects the palms, nails (with pits), and scalp. Psoriasis lesions are round (rather than oval), with coarser scale and without a herald patch.

The lack of antecedent sores and denial of sexual contact ruled out secondary syphilis (choice “c”). Patients with secondary syphilis often present with low-grade fever, malaise, and palmar scaly papules—all of which were missing in this case. Syphilis serology (rapid plasma reagin) can be easily obtained if doubt persists.

DISCUSSION

Pityriasis rosea (PR) is a papulosquamous eruption that is common in younger populations. About 40% of affected patients present with a large scaly lesion, which is followed by the appearance of multiple smaller oval lesions within days. In most cases, PR is fairly easy to diagnose: the lesion’s oval shape, pinkish-brown color, centripetal fine scale, herald patch, and adherence to skin tension lines are all characteristic findings.

Though the exact organism has not been identified, PR is almost certainly viral in origin. Like many viral exanthems, occurrence tends to peak in the spring and fall. There are also indications that the body builds immunity to the infection, since recurrence outside the acute phase is rare.

Treatment options are unsatisfactory, though exposure to UV sources appears to help. Patients must be informed that their condition will, unfortunately, last for at least six to nine weeks, during which crops of lesions will come and go.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (choice “d”).

Virtually all patients with this condition believe that they have a terrible case of “ringworm” (ie, fungal infection; choice “a”)—an opinion all too often corroborated by the medical provider unacquainted with pityriasis rosea. The two can be difficult to distinguish, but the “herald” patch, oval shape, odd color, and fine scale all serve to confirm the diagnosis. When necessary, a KOH prep or biopsy can be done.

Psoriasis (choice “b”) can manifest acutely, but it is distinctly salmon-pink under coarse, white scale that affects the palms, nails (with pits), and scalp. Psoriasis lesions are round (rather than oval), with coarser scale and without a herald patch.

The lack of antecedent sores and denial of sexual contact ruled out secondary syphilis (choice “c”). Patients with secondary syphilis often present with low-grade fever, malaise, and palmar scaly papules—all of which were missing in this case. Syphilis serology (rapid plasma reagin) can be easily obtained if doubt persists.

DISCUSSION

Pityriasis rosea (PR) is a papulosquamous eruption that is common in younger populations. About 40% of affected patients present with a large scaly lesion, which is followed by the appearance of multiple smaller oval lesions within days. In most cases, PR is fairly easy to diagnose: the lesion’s oval shape, pinkish-brown color, centripetal fine scale, herald patch, and adherence to skin tension lines are all characteristic findings.

Though the exact organism has not been identified, PR is almost certainly viral in origin. Like many viral exanthems, occurrence tends to peak in the spring and fall. There are also indications that the body builds immunity to the infection, since recurrence outside the acute phase is rare.

Treatment options are unsatisfactory, though exposure to UV sources appears to help. Patients must be informed that their condition will, unfortunately, last for at least six to nine weeks, during which crops of lesions will come and go.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (choice “d”).

Virtually all patients with this condition believe that they have a terrible case of “ringworm” (ie, fungal infection; choice “a”)—an opinion all too often corroborated by the medical provider unacquainted with pityriasis rosea. The two can be difficult to distinguish, but the “herald” patch, oval shape, odd color, and fine scale all serve to confirm the diagnosis. When necessary, a KOH prep or biopsy can be done.

Psoriasis (choice “b”) can manifest acutely, but it is distinctly salmon-pink under coarse, white scale that affects the palms, nails (with pits), and scalp. Psoriasis lesions are round (rather than oval), with coarser scale and without a herald patch.

The lack of antecedent sores and denial of sexual contact ruled out secondary syphilis (choice “c”). Patients with secondary syphilis often present with low-grade fever, malaise, and palmar scaly papules—all of which were missing in this case. Syphilis serology (rapid plasma reagin) can be easily obtained if doubt persists.

DISCUSSION

Pityriasis rosea (PR) is a papulosquamous eruption that is common in younger populations. About 40% of affected patients present with a large scaly lesion, which is followed by the appearance of multiple smaller oval lesions within days. In most cases, PR is fairly easy to diagnose: the lesion’s oval shape, pinkish-brown color, centripetal fine scale, herald patch, and adherence to skin tension lines are all characteristic findings.

Though the exact organism has not been identified, PR is almost certainly viral in origin. Like many viral exanthems, occurrence tends to peak in the spring and fall. There are also indications that the body builds immunity to the infection, since recurrence outside the acute phase is rare.

Treatment options are unsatisfactory, though exposure to UV sources appears to help. Patients must be informed that their condition will, unfortunately, last for at least six to nine weeks, during which crops of lesions will come and go.

About 10 days ago, an asymptomatic, scaly lesion arose overnight on this 21-year-old man’s upper left chest, near the anterior deltoid area. Within the past week, multiple scaly lesions—much smaller than the original—have appeared on his trunk and arms.

The patient claims to be in good health otherwise, denying fever, malaise, or myalgia. He denies sexual contact of any kind in the past two months. There is no personal or family history of skin disease or atopy.

On exam, the patient looks his stated age, is afebrile, and is in no acute distress. On his chest is an oval, pinkish brown, papulosquamous lesion with very fine, sparse scaling in the center. The long axis of the lesion parallels local skin tension lines.

About 20 additional lesions are observed elsewhere, primarily on the truncal skin, sparing the upper neck, face, and palms. All are oval, with the same odd color and scale, and follow skin tension lines. The patient’s elbows, knees, scalp, and nails are unaffected, as are the areas around and below the waist.

"It's the Pits"

The several-week duration of this 14-year-old boy’s rash is worrisome to him and his family, despite a lack of other symptoms. Located on his right axilla, the rash was previously diagnosed as “yeast infection” but was unaffected by topical anti-yeast medications (nystatin and clotrimazole creams) and oral fluconazole.

A serious family crisis preceded the appearance of the rash: The parents lost custody of their children, who were then placed under the care of grandparents in another state. The boy lost his family and friends and had to start again in a new school.

EXAMINATION

Additional rashes are present on his face, in and behind his ears, and on focal areas of his genitals. They are all orangish red with faintly scaly surfaces. The scale on his face, ears, and genitals is coarser than that of his axilla, but it is the same salmon-pink. Focal areas of his brows and scalp are also involved.

What is the diagnosis?

Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is most commonly seen on the scalp in the form of dandruff, but it can also flare in other locations. Seborrhea is an adverse inflammatory response to the consumption of sebum by commensal yeast organisms (eg, Pityrosporum) on oil-rich skin. Stress is believed to trigger flares (as exemplified in this case), presumably because it increases the production and outflow of sebum.

Non-dermatology providers often incorrectly diagnose axillary rashes as yeast infections, or seborrhea on the face as fungal infection, simply for lack of a complete differential. The truth is, yeast infections of the skin are unusual. The differential should include psoriasis or eczema, as well as sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

The “trick” to diagnosing seborrhea is to recognize that it is incredibly common (affecting around 30% of the Caucasian population), is often inherited, and can affect multiple sites. When it is seen in one area, corroboration can be sought by locating typical changes elsewhere.

Although there is no cure, control is obtained through use of topical anti-yeast creams (eg, ketoconazole) combined with a mild topical steroid (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone). Using ketoconazole 2% shampoo for the scalp and other affected areas can be helpful as well. Use of nystatin, however, has long been replaced by more effective alternatives.

With a bit of luck, the patient’s stress will diminish over time, which should be a big help in resolving this problem.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is extremely common among those of northern European descent and can affect not only the scalp, but also the face, ears, chest, axillae, and genitals.

- The rash is usually orangish pink and slightly scaly, unless it’s in the axillae, where moisture and friction preclude the formation of significant scale.

- Seborrhea is often misdiagnosed as yeast infection, but the latter is quite unusual on the skin.

- The differential should include psoriasis, eczema, and sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

The several-week duration of this 14-year-old boy’s rash is worrisome to him and his family, despite a lack of other symptoms. Located on his right axilla, the rash was previously diagnosed as “yeast infection” but was unaffected by topical anti-yeast medications (nystatin and clotrimazole creams) and oral fluconazole.

A serious family crisis preceded the appearance of the rash: The parents lost custody of their children, who were then placed under the care of grandparents in another state. The boy lost his family and friends and had to start again in a new school.

EXAMINATION

Additional rashes are present on his face, in and behind his ears, and on focal areas of his genitals. They are all orangish red with faintly scaly surfaces. The scale on his face, ears, and genitals is coarser than that of his axilla, but it is the same salmon-pink. Focal areas of his brows and scalp are also involved.

What is the diagnosis?

Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is most commonly seen on the scalp in the form of dandruff, but it can also flare in other locations. Seborrhea is an adverse inflammatory response to the consumption of sebum by commensal yeast organisms (eg, Pityrosporum) on oil-rich skin. Stress is believed to trigger flares (as exemplified in this case), presumably because it increases the production and outflow of sebum.

Non-dermatology providers often incorrectly diagnose axillary rashes as yeast infections, or seborrhea on the face as fungal infection, simply for lack of a complete differential. The truth is, yeast infections of the skin are unusual. The differential should include psoriasis or eczema, as well as sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

The “trick” to diagnosing seborrhea is to recognize that it is incredibly common (affecting around 30% of the Caucasian population), is often inherited, and can affect multiple sites. When it is seen in one area, corroboration can be sought by locating typical changes elsewhere.

Although there is no cure, control is obtained through use of topical anti-yeast creams (eg, ketoconazole) combined with a mild topical steroid (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone). Using ketoconazole 2% shampoo for the scalp and other affected areas can be helpful as well. Use of nystatin, however, has long been replaced by more effective alternatives.

With a bit of luck, the patient’s stress will diminish over time, which should be a big help in resolving this problem.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is extremely common among those of northern European descent and can affect not only the scalp, but also the face, ears, chest, axillae, and genitals.

- The rash is usually orangish pink and slightly scaly, unless it’s in the axillae, where moisture and friction preclude the formation of significant scale.

- Seborrhea is often misdiagnosed as yeast infection, but the latter is quite unusual on the skin.

- The differential should include psoriasis, eczema, and sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

The several-week duration of this 14-year-old boy’s rash is worrisome to him and his family, despite a lack of other symptoms. Located on his right axilla, the rash was previously diagnosed as “yeast infection” but was unaffected by topical anti-yeast medications (nystatin and clotrimazole creams) and oral fluconazole.

A serious family crisis preceded the appearance of the rash: The parents lost custody of their children, who were then placed under the care of grandparents in another state. The boy lost his family and friends and had to start again in a new school.

EXAMINATION

Additional rashes are present on his face, in and behind his ears, and on focal areas of his genitals. They are all orangish red with faintly scaly surfaces. The scale on his face, ears, and genitals is coarser than that of his axilla, but it is the same salmon-pink. Focal areas of his brows and scalp are also involved.

What is the diagnosis?

Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is most commonly seen on the scalp in the form of dandruff, but it can also flare in other locations. Seborrhea is an adverse inflammatory response to the consumption of sebum by commensal yeast organisms (eg, Pityrosporum) on oil-rich skin. Stress is believed to trigger flares (as exemplified in this case), presumably because it increases the production and outflow of sebum.

Non-dermatology providers often incorrectly diagnose axillary rashes as yeast infections, or seborrhea on the face as fungal infection, simply for lack of a complete differential. The truth is, yeast infections of the skin are unusual. The differential should include psoriasis or eczema, as well as sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

The “trick” to diagnosing seborrhea is to recognize that it is incredibly common (affecting around 30% of the Caucasian population), is often inherited, and can affect multiple sites. When it is seen in one area, corroboration can be sought by locating typical changes elsewhere.

Although there is no cure, control is obtained through use of topical anti-yeast creams (eg, ketoconazole) combined with a mild topical steroid (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone). Using ketoconazole 2% shampoo for the scalp and other affected areas can be helpful as well. Use of nystatin, however, has long been replaced by more effective alternatives.

With a bit of luck, the patient’s stress will diminish over time, which should be a big help in resolving this problem.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is extremely common among those of northern European descent and can affect not only the scalp, but also the face, ears, chest, axillae, and genitals.

- The rash is usually orangish pink and slightly scaly, unless it’s in the axillae, where moisture and friction preclude the formation of significant scale.

- Seborrhea is often misdiagnosed as yeast infection, but the latter is quite unusual on the skin.

- The differential should include psoriasis, eczema, and sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

Sunny With a Chance of Skin Damage

A 56-year-old woman has several lesions she is worried might be cancerous. Added to that, there have been changes to her facial skin over the past several years that are increasingly obvious to her friends and family and therefore concerning to the patient.

She has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancers, including basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, which were removed from her trunk in the distant past. She has lived in the southwestern United States all her life and has been smoking cigarettes since age 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s skin is quite fair, with abundant evidence of sun damage. She looks considerably older than her stated age.

Fortunately, no skin cancers are found on examination, but many closed and open comedones can be seen on both of her cheeks, stippled on rough, weathered skin. Solar elastosis manifests in this area as diffuse white thickening—what some might call “chicken skin.”

What is the diagnosis?

Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is a fairly common result of chronic overexposure to UV sources; it is especially prevalent among men who smoke. For reasons not fully understood, the changes associated with FRS tend to be relegated to the bilateral malar cheeks, roughly even with the eyes. Apart from the patient being female, this case is quite typical.

Chronic overexposure to UV light is known to result in dermatologic changes such as solar elastosis and the aforementioned whitish plaques—which, on microscopic exam, are simply basophilic degeneration of the dermis. This degeneration can be seen all over the face, but it is particularly evident on the forehead and cheeks; the concentration of comedones on the cheeks is unique to FRS.

Treatment options include lasers and peels, which involve considerable expenditure of time and money. While the comedones can be extracted, they are likely to recur unless more invasive methods are used.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is seen primarily in men with chronic overexposure to sunlight—particularly those who smoke.

- FRS is characterized by localized collections of open and closed comedones superimposed on thickened, white “chicken skin” (solar elastosis).

- These changes typically occur on the bilateral cheeks of patients in the later decades of life, though they have been seen on patients in their 20s.

- Treatment is possible by means of laser resurfacing and/or chemical peels.

A 56-year-old woman has several lesions she is worried might be cancerous. Added to that, there have been changes to her facial skin over the past several years that are increasingly obvious to her friends and family and therefore concerning to the patient.

She has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancers, including basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, which were removed from her trunk in the distant past. She has lived in the southwestern United States all her life and has been smoking cigarettes since age 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s skin is quite fair, with abundant evidence of sun damage. She looks considerably older than her stated age.

Fortunately, no skin cancers are found on examination, but many closed and open comedones can be seen on both of her cheeks, stippled on rough, weathered skin. Solar elastosis manifests in this area as diffuse white thickening—what some might call “chicken skin.”

What is the diagnosis?

Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is a fairly common result of chronic overexposure to UV sources; it is especially prevalent among men who smoke. For reasons not fully understood, the changes associated with FRS tend to be relegated to the bilateral malar cheeks, roughly even with the eyes. Apart from the patient being female, this case is quite typical.

Chronic overexposure to UV light is known to result in dermatologic changes such as solar elastosis and the aforementioned whitish plaques—which, on microscopic exam, are simply basophilic degeneration of the dermis. This degeneration can be seen all over the face, but it is particularly evident on the forehead and cheeks; the concentration of comedones on the cheeks is unique to FRS.

Treatment options include lasers and peels, which involve considerable expenditure of time and money. While the comedones can be extracted, they are likely to recur unless more invasive methods are used.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is seen primarily in men with chronic overexposure to sunlight—particularly those who smoke.

- FRS is characterized by localized collections of open and closed comedones superimposed on thickened, white “chicken skin” (solar elastosis).

- These changes typically occur on the bilateral cheeks of patients in the later decades of life, though they have been seen on patients in their 20s.

- Treatment is possible by means of laser resurfacing and/or chemical peels.

A 56-year-old woman has several lesions she is worried might be cancerous. Added to that, there have been changes to her facial skin over the past several years that are increasingly obvious to her friends and family and therefore concerning to the patient.

She has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancers, including basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, which were removed from her trunk in the distant past. She has lived in the southwestern United States all her life and has been smoking cigarettes since age 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s skin is quite fair, with abundant evidence of sun damage. She looks considerably older than her stated age.

Fortunately, no skin cancers are found on examination, but many closed and open comedones can be seen on both of her cheeks, stippled on rough, weathered skin. Solar elastosis manifests in this area as diffuse white thickening—what some might call “chicken skin.”

What is the diagnosis?

Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is a fairly common result of chronic overexposure to UV sources; it is especially prevalent among men who smoke. For reasons not fully understood, the changes associated with FRS tend to be relegated to the bilateral malar cheeks, roughly even with the eyes. Apart from the patient being female, this case is quite typical.

Chronic overexposure to UV light is known to result in dermatologic changes such as solar elastosis and the aforementioned whitish plaques—which, on microscopic exam, are simply basophilic degeneration of the dermis. This degeneration can be seen all over the face, but it is particularly evident on the forehead and cheeks; the concentration of comedones on the cheeks is unique to FRS.

Treatment options include lasers and peels, which involve considerable expenditure of time and money. While the comedones can be extracted, they are likely to recur unless more invasive methods are used.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is seen primarily in men with chronic overexposure to sunlight—particularly those who smoke.

- FRS is characterized by localized collections of open and closed comedones superimposed on thickened, white “chicken skin” (solar elastosis).

- These changes typically occur on the bilateral cheeks of patients in the later decades of life, though they have been seen on patients in their 20s.

- Treatment is possible by means of laser resurfacing and/or chemical peels.

Perplexingly Purple

A 55-year-old woman presents for evaluation of a widespread rash that first appeared several months ago. The rash has resisted treatment with various OTC products—antifungal cream (tolnaftate), triple-antibiotic cream, and tea tree oil—and continues to itch terribly at times.

Her primary care provider prescribed oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) for a proposed fungal etiology after viewing the rash with a Wood lamp and performing a KOH prep. A one-month course yielded no relief.

The patient claims to be in good health otherwise. She does admit to going through a stressful period involving job loss, divorce, and care of her aging parents.

EXAMINATION

Multiple papulosquamous papules, nodules, and plaques are located on the patient’s arms, legs, wrists, and sacrum. The lesions range from pinpoint to several centimeters and oval to polygonal. They have a striking purple appearance. On closer inspection, many have a shiny, whitish sheen on the surface.

What is the diagnosis?

This is a classic case of lichen planus (LP), an unusual papulosquamous condition of unknown etiology. In addition to the mentioned areas, it can affect the mucosal surfaces, scalp, genitals, nails, and internal organs.

There is no evidence that the cause is infectious; rather, it appears to be triggered by a reaction to an unknown (possibly autoimmune) antigen. LP targets specific cells and produces a lichenoid reaction, in which the upper level of the dermis is broken down by an apoptotic process. This produces a characteristic sawtooth pattern at the dermoepidermal junction by a pathognomic lymphocytic infiltrate. The surface of the affected skin has a shiny, frosty appearance, also seen in other lichenoid conditions (eg, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus).

Other key diagnostic features are classified as “the Ps”: purple, plaquish, papular, planar (flat-topped), polygonal (multi-angular), penile, pruritic, and puzzling. The last word is key to triggering consideration of the other “Ps.”

LP that affects the scalp and mucosal surfaces can be problematic to treat. Topical steroids are the mainstay, but treatment can also include oral retinoids (acetretin, isotretinoin), methotrexate, antimalarials, and cyclosporine. Furthermore, LP can overlap with other diseases—notably lupus, for which TNF-[a] inhibitors are used with some success. For limited disease, intralesional steroid injections can be used (5 to 10 mg/cc triamcinolone).

This patient achieved good relief with a combination of topical and intralesional steroids. Fortunately, in most cases, the disease eventually resolves on its own.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen planus is an unusual condition, but the look and distribution seen in this case are fairly typical.

- The classic diagnostic “Ps” include: purple, papular, pruritic, plaquish, planar, and most of all puzzling.

- Wood lamp examination is useless for the most common dermatophytoses, which will not fluoresce; however, KOH preps are useful when correctly interpreted.

- In more obscure cases, a punch or shave biopsy will confirm the diagnosis.

A 55-year-old woman presents for evaluation of a widespread rash that first appeared several months ago. The rash has resisted treatment with various OTC products—antifungal cream (tolnaftate), triple-antibiotic cream, and tea tree oil—and continues to itch terribly at times.

Her primary care provider prescribed oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) for a proposed fungal etiology after viewing the rash with a Wood lamp and performing a KOH prep. A one-month course yielded no relief.

The patient claims to be in good health otherwise. She does admit to going through a stressful period involving job loss, divorce, and care of her aging parents.

EXAMINATION

Multiple papulosquamous papules, nodules, and plaques are located on the patient’s arms, legs, wrists, and sacrum. The lesions range from pinpoint to several centimeters and oval to polygonal. They have a striking purple appearance. On closer inspection, many have a shiny, whitish sheen on the surface.

What is the diagnosis?

This is a classic case of lichen planus (LP), an unusual papulosquamous condition of unknown etiology. In addition to the mentioned areas, it can affect the mucosal surfaces, scalp, genitals, nails, and internal organs.

There is no evidence that the cause is infectious; rather, it appears to be triggered by a reaction to an unknown (possibly autoimmune) antigen. LP targets specific cells and produces a lichenoid reaction, in which the upper level of the dermis is broken down by an apoptotic process. This produces a characteristic sawtooth pattern at the dermoepidermal junction by a pathognomic lymphocytic infiltrate. The surface of the affected skin has a shiny, frosty appearance, also seen in other lichenoid conditions (eg, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus).

Other key diagnostic features are classified as “the Ps”: purple, plaquish, papular, planar (flat-topped), polygonal (multi-angular), penile, pruritic, and puzzling. The last word is key to triggering consideration of the other “Ps.”

LP that affects the scalp and mucosal surfaces can be problematic to treat. Topical steroids are the mainstay, but treatment can also include oral retinoids (acetretin, isotretinoin), methotrexate, antimalarials, and cyclosporine. Furthermore, LP can overlap with other diseases—notably lupus, for which TNF-[a] inhibitors are used with some success. For limited disease, intralesional steroid injections can be used (5 to 10 mg/cc triamcinolone).

This patient achieved good relief with a combination of topical and intralesional steroids. Fortunately, in most cases, the disease eventually resolves on its own.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen planus is an unusual condition, but the look and distribution seen in this case are fairly typical.

- The classic diagnostic “Ps” include: purple, papular, pruritic, plaquish, planar, and most of all puzzling.

- Wood lamp examination is useless for the most common dermatophytoses, which will not fluoresce; however, KOH preps are useful when correctly interpreted.

- In more obscure cases, a punch or shave biopsy will confirm the diagnosis.

A 55-year-old woman presents for evaluation of a widespread rash that first appeared several months ago. The rash has resisted treatment with various OTC products—antifungal cream (tolnaftate), triple-antibiotic cream, and tea tree oil—and continues to itch terribly at times.

Her primary care provider prescribed oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) for a proposed fungal etiology after viewing the rash with a Wood lamp and performing a KOH prep. A one-month course yielded no relief.

The patient claims to be in good health otherwise. She does admit to going through a stressful period involving job loss, divorce, and care of her aging parents.

EXAMINATION

Multiple papulosquamous papules, nodules, and plaques are located on the patient’s arms, legs, wrists, and sacrum. The lesions range from pinpoint to several centimeters and oval to polygonal. They have a striking purple appearance. On closer inspection, many have a shiny, whitish sheen on the surface.

What is the diagnosis?

This is a classic case of lichen planus (LP), an unusual papulosquamous condition of unknown etiology. In addition to the mentioned areas, it can affect the mucosal surfaces, scalp, genitals, nails, and internal organs.

There is no evidence that the cause is infectious; rather, it appears to be triggered by a reaction to an unknown (possibly autoimmune) antigen. LP targets specific cells and produces a lichenoid reaction, in which the upper level of the dermis is broken down by an apoptotic process. This produces a characteristic sawtooth pattern at the dermoepidermal junction by a pathognomic lymphocytic infiltrate. The surface of the affected skin has a shiny, frosty appearance, also seen in other lichenoid conditions (eg, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus).

Other key diagnostic features are classified as “the Ps”: purple, plaquish, papular, planar (flat-topped), polygonal (multi-angular), penile, pruritic, and puzzling. The last word is key to triggering consideration of the other “Ps.”

LP that affects the scalp and mucosal surfaces can be problematic to treat. Topical steroids are the mainstay, but treatment can also include oral retinoids (acetretin, isotretinoin), methotrexate, antimalarials, and cyclosporine. Furthermore, LP can overlap with other diseases—notably lupus, for which TNF-[a] inhibitors are used with some success. For limited disease, intralesional steroid injections can be used (5 to 10 mg/cc triamcinolone).

This patient achieved good relief with a combination of topical and intralesional steroids. Fortunately, in most cases, the disease eventually resolves on its own.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen planus is an unusual condition, but the look and distribution seen in this case are fairly typical.

- The classic diagnostic “Ps” include: purple, papular, pruritic, plaquish, planar, and most of all puzzling.

- Wood lamp examination is useless for the most common dermatophytoses, which will not fluoresce; however, KOH preps are useful when correctly interpreted.

- In more obscure cases, a punch or shave biopsy will confirm the diagnosis.

Slow and Steady: A Worrisome Pace

ANSWER

The false statement is that most melanomas are raised (choice “a”), since most melanomas are essentially macular (flat).

DISCUSSION

Misconceptions about melanomas often delay diagnosis, costing lives. In truth, the majority of melanomas are difficult, if not impossible, to feel on palpation. This is because they arise in the skin, rather than on it.

Malignant melanomas are cancers of melanocytes (the cells that line the basal cell layer). Overexposure to UV sources damages the nuclei of these cells, compromising their ability to repair the damage. This can lead to focally unregulated cell growth.

Initially, this uncontrolled cell replication spreads horizontally. Over time, though, it can grow vertically and penetrate deep enough to invade the vasculature (roughly 1 mm deep), and spread to the liver, lung, or brain. This is why ascertaining the depth of a melanoma is critical for predicting prognosis and determining the extent of additional surgery and search for evidence of metastatic disease.

Melanomas do not typically itch or bleed until they are advanced (if at all). And most arise de novo (as new lesions, rather than pre-existing). So, contrary to popular belief, moles rarely turn into melanomas.

It is also true that approximately 80% of all melanomas arise on skin normally covered by clothing, despite the role of sunlight in the development of melanoma. For reasons not totally understood, the combination of fair, su

ANSWER

The false statement is that most melanomas are raised (choice “a”), since most melanomas are essentially macular (flat).

DISCUSSION

Misconceptions about melanomas often delay diagnosis, costing lives. In truth, the majority of melanomas are difficult, if not impossible, to feel on palpation. This is because they arise in the skin, rather than on it.

Malignant melanomas are cancers of melanocytes (the cells that line the basal cell layer). Overexposure to UV sources damages the nuclei of these cells, compromising their ability to repair the damage. This can lead to focally unregulated cell growth.

Initially, this uncontrolled cell replication spreads horizontally. Over time, though, it can grow vertically and penetrate deep enough to invade the vasculature (roughly 1 mm deep), and spread to the liver, lung, or brain. This is why ascertaining the depth of a melanoma is critical for predicting prognosis and determining the extent of additional surgery and search for evidence of metastatic disease.

Melanomas do not typically itch or bleed until they are advanced (if at all). And most arise de novo (as new lesions, rather than pre-existing). So, contrary to popular belief, moles rarely turn into melanomas.

It is also true that approximately 80% of all melanomas arise on skin normally covered by clothing, despite the role of sunlight in the development of melanoma. For reasons not totally understood, the combination of fair, su

ANSWER

The false statement is that most melanomas are raised (choice “a”), since most melanomas are essentially macular (flat).

DISCUSSION

Misconceptions about melanomas often delay diagnosis, costing lives. In truth, the majority of melanomas are difficult, if not impossible, to feel on palpation. This is because they arise in the skin, rather than on it.

Malignant melanomas are cancers of melanocytes (the cells that line the basal cell layer). Overexposure to UV sources damages the nuclei of these cells, compromising their ability to repair the damage. This can lead to focally unregulated cell growth.

Initially, this uncontrolled cell replication spreads horizontally. Over time, though, it can grow vertically and penetrate deep enough to invade the vasculature (roughly 1 mm deep), and spread to the liver, lung, or brain. This is why ascertaining the depth of a melanoma is critical for predicting prognosis and determining the extent of additional surgery and search for evidence of metastatic disease.

Melanomas do not typically itch or bleed until they are advanced (if at all). And most arise de novo (as new lesions, rather than pre-existing). So, contrary to popular belief, moles rarely turn into melanomas.

It is also true that approximately 80% of all melanomas arise on skin normally covered by clothing, despite the role of sunlight in the development of melanoma. For reasons not totally understood, the combination of fair, su

For more than two years, a 43-year-old man has had an asymptomatic lesion on his right deltoid area. His primary care provider has repeatedly assured him of its benignancy “because it is flat.” But its slow, steady, horizontal growth concerns the patient, who is otherwise healthy.

He does admit to a significant history of sun exposure, explaining that he burns easily but acquires a tan by summer’s end each year. Several members of his immediate family have had skin cancers removed.

Examination reveals a round, dark macule, measuring 1.1 cm, on the right lateral deltoid area. The lesion has poorly defined borders and a variety of colors—mostly black and brown, with flecks of red and pink. There is no palpable component, and no nodes can be detected in the area.

The rest of his type II skin has abundant evidence of UV overexposure, including solar lentigines and weathering, especially around the neck.

The lesion is anesthetized, removed by deep shave technique, and submitted to pathology. The report shows a superficial, spreading melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.75 mm. Malignant cells extend to the dermoepidermal junction (Clark level II). Only a few mitotic cells can be seen, with no intravascular invasion or signs of ulceration.

It's Not Appealing, But It Is A-Peeling

A 6-year-old boy is referred to dermatology for evaluation of his dry, thin skin. Since birth, it has frequently torn, and it burns with the application of almost any product or soap. Neither OTC nor prescription products have helped.

The boy is reportedly in good health otherwise and is not atopic. Nonetheless, two of his siblings are similarly affected, and there is a strong family history of similar dermatologic problems on his father’s side. He and his family are from Mexico and have type IV skin.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no distress but does complain about his skin problems. His skin is quite thin and dry, and fine scaling covers his palms, face, legs, trunk, and scalp. In short, none of his skin looks normal. The skin on his legs is especially scaly and has a pronounced reticulated appearance.

His fingernails are dystrophic, with transverse ridging and a loss of connection between the cuticles and nail plates.

What is the diagnosis?

Ichthyosis vulgaris (IV) is one of a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together. This breakdown can lead to excessive water loss, as well as vulnerability of skin to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

IV is by far the most common variation, comprising at least 95% of all ichthyosiform dermatoses. It results from an inherited abnormality of epidermal differentiation or metabolism; affected patients have a higher incidence of eye problems (eg, keratitis, cataracts) in addition to their skin problems.

A total of 28 types of ichthyosis have been described, many of which are part of larger syndromes (such as keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome or Netherton syndrome). Another uncommon type, X-linked recessive ichthyosis, manifests in about 1 in 5,000 births; these patients improve dramatically in the summertime with additional sun exposure.

Ichthyosis manifests with varying degrees of severity. While this case is fairly severe, the worst cases (Harlequin and lamellar forms) begin at birth with a nearly absent stratum corneum.

This patient and his family were advised on the use of emollients and avoidance of excessive drying of skin. They were also strongly encouraged to seek genetic counseling.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Ichthyosis is a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together.

- The resultant water loss can leave skin vulnerable to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

- Ichthyosis vulgaris is by far the most common member of this family of disorders, comprising more than 95% of cases.

- Heavy emollients and avoidance of drying constitute the bulk of treatment efforts.

A 6-year-old boy is referred to dermatology for evaluation of his dry, thin skin. Since birth, it has frequently torn, and it burns with the application of almost any product or soap. Neither OTC nor prescription products have helped.

The boy is reportedly in good health otherwise and is not atopic. Nonetheless, two of his siblings are similarly affected, and there is a strong family history of similar dermatologic problems on his father’s side. He and his family are from Mexico and have type IV skin.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no distress but does complain about his skin problems. His skin is quite thin and dry, and fine scaling covers his palms, face, legs, trunk, and scalp. In short, none of his skin looks normal. The skin on his legs is especially scaly and has a pronounced reticulated appearance.

His fingernails are dystrophic, with transverse ridging and a loss of connection between the cuticles and nail plates.

What is the diagnosis?

Ichthyosis vulgaris (IV) is one of a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together. This breakdown can lead to excessive water loss, as well as vulnerability of skin to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.