according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Those new lows – TB incidence of 2.8 per 100,000 persons and 9,093 new cases – continue a downward trend that started in 1993, but the current rate of decline is much lower than the threshold needed to eliminate TB by the year 2100, Rebekah J. Stewart and her associates at the CDC’s Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, Atlanta, wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

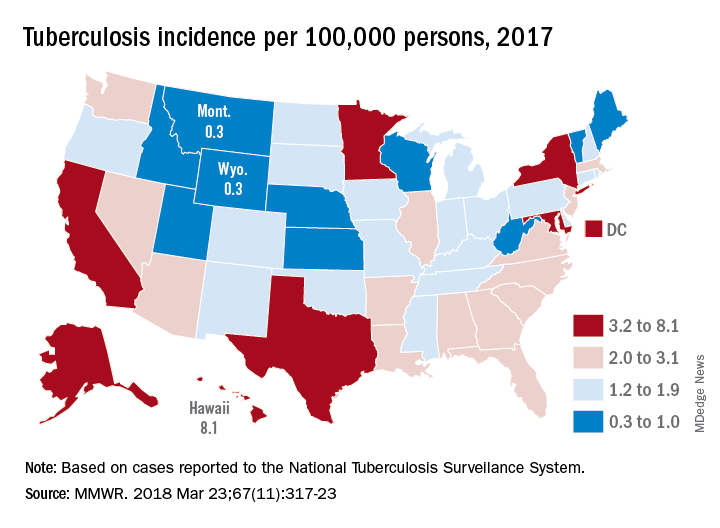

TB incidence for 2017 was, in fact, 28 times higher than the U.S. elimination threshold of less than one case per 1,000,000 persons, and the average annual rate of decline since 2014, 2.0%, is only about half the sustained annual decline of 3.9% needed to eliminate TB by the year 2100. “Ongoing efforts to prevent TB transmission must be sustained, and efforts to detect and treat [latent TB infection], especially among groups at high risk, must be increased,” they said.Geographically, at least, the states with populations at the highest risk are Hawaii, which had a TB incidence of 8.1 per 100,000 persons in 2017, and Alaska, with an incidence of 7.0 per 100,000. California and the District of Columbia were next, each with an incidence of 5.2. The states with the lowest rates were Montana and Wyoming at 0.3 per 100,000, the investigators reported, based on data from the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System as of Feb. 12, 2018.

Groups most affected by TB include persons housed in congregate settings – homeless shelters, long-term care facilities, and correctional facilities – and those from countries that have high TB prevalence. Overall incidence for non–U.S. born residents was 14.6 per 100,000 in 2017, compared with 1.0 for the native born, with large discrepancies seen between U.S. and non–U.S. born blacks (2.8 vs. 22.0), native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders (6.5 vs. 21.0), and Asians (2.0 vs. 27.0), Ms. Stewart and her associates said.

“Increased support of global TB elimination efforts would help to reduce global … prevalence, thereby indirectly reducing the incidence of reactivation TB in the United States among non–U.S. born persons from higher-prevalence countries,” they wrote.

The issue of global action on TB was addressed by the Forum of International Respiratory Societies in a statement recognizing World TB Day (March 24). “TB is the world’s most common infectious disease killer, yet is identifiable, treatable and preventable; what is missing is the political will to dedicate the resources necessary to eradicate it, once and for all,” said Dean E. Schraufnagel, MD, the organization’s executive director.

SOURCE: Stewart RJ et al. MMWR 2018 Mar 23;67(11):317-23.