User login

Because eclampsia occurs but rarely during pregnancy and the postpartum period, most health-care providers have little to no personal experience with management of this life-threatening obstetric emergency. Knowledge about maternal resuscitation during and after an eclamptic seizure is critical for improving maternal and perinatal outcomes.

In this round-up, I present 10 practical recommendations for prompt diagnosis and management of women who have eclampsia. Immediate implementation of these recommendations can lead to improved maternal and perinatal outcomes (both acute and long-term).

1. Practice. Practice again.

Implement regular monthly simulation training sessions

Fisher N, Bernstein PS, Satin A, et al. Resident training for eclampsia and magnesium toxicity management: simulation or traditional lecture? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):379.e1–5.

Eclampsia is unpredictable and can develop rapidly at home, in labor and delivery, on the antepartum/postpartum ward, and in the emergency room. Therefore, it is prudent that all health-care providers who treat pregnant or postpartum women on a daily basis be trained and knowledgeable about early detection and management of eclampsia. This goal can be achieved by developing drills for rehearsal and by testing the response and skills of all providers.

2. Preventive: Magnesium sulfate

Do not attempt to arrest the seizure. Use MgSO4 to prevent recurrent convulsions.

Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Walker GJ, Chou D. Magnesium sulfate versus diazepam for eclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(12):CD000127.

Most eclamptic seizures are self-limiting. Therefore, there is no need to administer bolus drugs such as diazepam or midazolam. These drugs are usually used in the emergency room, but they inhibit maternal laryngeal reflexes and may lead to aspiration. They also suppress the central nervous system respiratory centers and can cause apnea, requiring intubation.

When used in the management of eclampsia, magnesium sulfate is associated with a lower rate of recurrent seizures and maternal death than is diazepam.

3. FHR changes? Be patient.

Do not rush the patient to emergent cesarean section because of an abnormal FHR tracing

Sibai BM. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):402–410.

During an eclamptic convulsion, there is usually prolonged fetal heart rate (FHR) deceleration or even bradycardia—with or without an increase in both frequency and uterine tone. After the convulsion, as a result of maternal hypoxia and hypercarbia, the FHR tracing can show tachycardia, reduced beat-to-beat variability, and transient recurrent decelerations. When this happens, concern about fetal status can distract the obstetric provider from resuscitation of the mother. However, these FHR changes usually return to normal after maternal resuscitation. If the FHR changes persist for longer than 15 minutes, consider abruptio placentae and move to delivery.

4. Target: Lower BP

Reduce maternal blood pressure to a safe level to prevent stroke, but without compromising uteroplacental perfusion

Zwart JJ, Richters A, Ory F, de Vries JI, Bloemenkamp KW, van Roosmalen J. Eclampsia in the Netherlands. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):820–827.

In this nationwide review of complications from eclampsia in the Netherlands, the authors found that failure to treat persistent severe hypertension was associated with hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebral infarction, bleeding, or congestive heart failure. They also found that 35.2% of women had systolic or diastolic blood pressure at or above 170/110 mm Hg at admission, but fewer than half were given antihypertensive drugs at that time. Among the cases deemed to have received substandard care, one third involved inadequate treatment of hypertension.

5. Know your antihypertensives

Learn which agents are best to control severe hypertension in eclampsia

Sibai BM. Hypertensive Emergencies. In: Foley MR, Strong TH, Garite TJ, eds. Obstetric Intensive Care Manual. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2010.

It is critical to familiarize oneself with the mechanism of action, dose, and potential side effects of agents used to control hypertension. For example, neither hydralazine nor nifedipine should be used in patients who have severe headache and persistent tachycardia (pulse, >100 bpm). Labetalol should be avoided in women who have persistent bradycardia (pulse, <60 bpm), asthma, or congestive heart failure.

For women who have persistent headache and tachycardia, I suggest intravenous (IV) labetalol, starting at a dose of 20 mg, 40 mg, or 80 mg every 10 minutes as needed to keep systolic blood pressure below 160 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg. The maximum dose of labetalol should not exceed 300 mg in 1 hour.

For patients who have bradycardia and severe asthma, I suggest oral, rapid-acting nifedipine, starting at 10 mg to 20 mg, to be repeated in 20 to 30 minutes as needed, up to a maximum of 50 mg to 60 mg in 1 hour. Oral nifedipine can be used with magnesium sulfate. An alternative is an IV bolus injection of hydralazine, starting at a dose of 5 mg to 10 mg, to be repeated every 15 minutes, up to a maximum dose of 25 mg.

6. Avoid general anesthesia

Use neuraxial anesthesia for labor and delivery in eclampsia

Turner JA. Severe preeclampsia: anesthetic implications of the disease and its management. Am J Ther. 2009;16(4):284–248.

Huang CJ, Fan YC, Tsai PS. Differential impacts of modes of anaesthesia on the risk of stroke among preeclamptic women who undergo Cesarean delivery: a population-based study. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105(6):818–826.

Epidural, spinal, or combined anesthesia is safe in the absence of coagulopathy or severe thrombocytopenia. General anesthesia increases the risk of aspiration, failed intubation due to pharyngolaryngeal edema, and stroke secondary to the increase in systemic and intracerebral pressures during intubation and extubation.

Eclampsia is not an indication for cesarean delivery

Repke JT, Sibai BM. Preeclampsia and eclampsia. OBG Manage. 2009;21(4):44–55.

Once the mother has been resuscitated and stabilized, the provider should choose a mode of delivery that is based on fetal condition, gestational age, presence or absence of labor, and the cervical Bishop score. Vaginal delivery can be achieved in most patients who have a gestational age of 34 weeks or greater.

8. Late presentation happens

Be aware that eclampsia can develop for the first time as long as 28 days postpartum

Sibai BM, Stella CL. Diagnosis and management of atypical preeclampsia-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(5):481.e31–37.

Atypical eclampsia is any eclampsia that develops beyond 48 hours postpartum. A history of diagnosed predelivery preeclampsia is not necessary for development of late postpartum eclampsia. In general, more than 50% of patients who develop late postpartum eclampsia have no evidence of preeclampsia prior to delivery.

Be aware that the clinical and neuro-imaging features of eclampsia overlap with those of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (angiopathy)

Fletcher JJ, Kramer AH, Bleck TP, Solenski NJ. Overlapping features of eclampsia and postpartum angiopathy. Neurocrit Care. 2009;11(2):199–209.

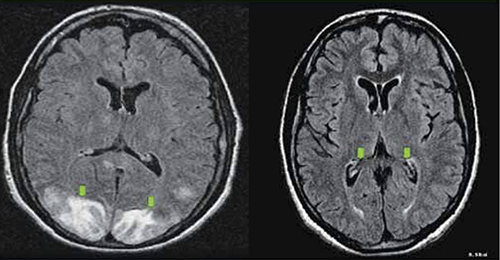

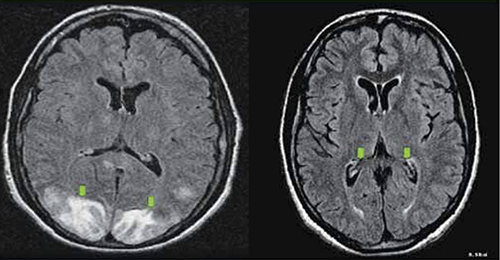

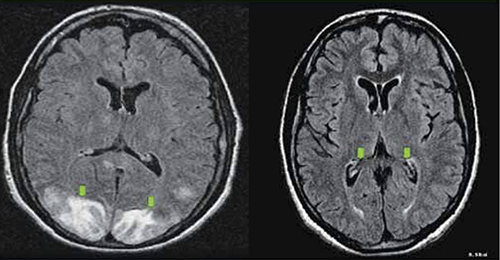

Women who have reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome have clinical findings (acute onset of recurrent headaches, visual changes, seizures, and hypertension) and cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings (posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome) that are similar to those of women who have late postpartum eclampsia (FIGURE). However, in women who have postpartum cerebral angiopathy, cerebral angiography will show the presence of bead-like vasoconstriction—which is usually absent in eclampsia.

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

Green arrows point to vasogenic edema in the occipital lobes and, partially, the parietal lobes. The edema is gone on repeat magnetic resonance imaging (see Recommendation #9).

10. Act today, see a better outcome tomorrow

Avoid long-term maternal neurologic injury by managing eclampsia properly

Zeeman GG. Neurologic complications of preeclampsia. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33(3):166–172.

Residual neurologic damage is rare in the majority of women who have eclampsia. However, long-term cerebral white-matter injury (cytotoxic edema, infarction) on MRI imaging and impaired memory and cognitive function may develop in some women who have multiple seizures and who have inadequately controlled persistent severe hypertension.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Because eclampsia occurs but rarely during pregnancy and the postpartum period, most health-care providers have little to no personal experience with management of this life-threatening obstetric emergency. Knowledge about maternal resuscitation during and after an eclamptic seizure is critical for improving maternal and perinatal outcomes.

In this round-up, I present 10 practical recommendations for prompt diagnosis and management of women who have eclampsia. Immediate implementation of these recommendations can lead to improved maternal and perinatal outcomes (both acute and long-term).

1. Practice. Practice again.

Implement regular monthly simulation training sessions

Fisher N, Bernstein PS, Satin A, et al. Resident training for eclampsia and magnesium toxicity management: simulation or traditional lecture? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):379.e1–5.

Eclampsia is unpredictable and can develop rapidly at home, in labor and delivery, on the antepartum/postpartum ward, and in the emergency room. Therefore, it is prudent that all health-care providers who treat pregnant or postpartum women on a daily basis be trained and knowledgeable about early detection and management of eclampsia. This goal can be achieved by developing drills for rehearsal and by testing the response and skills of all providers.

2. Preventive: Magnesium sulfate

Do not attempt to arrest the seizure. Use MgSO4 to prevent recurrent convulsions.

Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Walker GJ, Chou D. Magnesium sulfate versus diazepam for eclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(12):CD000127.

Most eclamptic seizures are self-limiting. Therefore, there is no need to administer bolus drugs such as diazepam or midazolam. These drugs are usually used in the emergency room, but they inhibit maternal laryngeal reflexes and may lead to aspiration. They also suppress the central nervous system respiratory centers and can cause apnea, requiring intubation.

When used in the management of eclampsia, magnesium sulfate is associated with a lower rate of recurrent seizures and maternal death than is diazepam.

3. FHR changes? Be patient.

Do not rush the patient to emergent cesarean section because of an abnormal FHR tracing

Sibai BM. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):402–410.

During an eclamptic convulsion, there is usually prolonged fetal heart rate (FHR) deceleration or even bradycardia—with or without an increase in both frequency and uterine tone. After the convulsion, as a result of maternal hypoxia and hypercarbia, the FHR tracing can show tachycardia, reduced beat-to-beat variability, and transient recurrent decelerations. When this happens, concern about fetal status can distract the obstetric provider from resuscitation of the mother. However, these FHR changes usually return to normal after maternal resuscitation. If the FHR changes persist for longer than 15 minutes, consider abruptio placentae and move to delivery.

4. Target: Lower BP

Reduce maternal blood pressure to a safe level to prevent stroke, but without compromising uteroplacental perfusion

Zwart JJ, Richters A, Ory F, de Vries JI, Bloemenkamp KW, van Roosmalen J. Eclampsia in the Netherlands. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):820–827.

In this nationwide review of complications from eclampsia in the Netherlands, the authors found that failure to treat persistent severe hypertension was associated with hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebral infarction, bleeding, or congestive heart failure. They also found that 35.2% of women had systolic or diastolic blood pressure at or above 170/110 mm Hg at admission, but fewer than half were given antihypertensive drugs at that time. Among the cases deemed to have received substandard care, one third involved inadequate treatment of hypertension.

5. Know your antihypertensives

Learn which agents are best to control severe hypertension in eclampsia

Sibai BM. Hypertensive Emergencies. In: Foley MR, Strong TH, Garite TJ, eds. Obstetric Intensive Care Manual. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2010.

It is critical to familiarize oneself with the mechanism of action, dose, and potential side effects of agents used to control hypertension. For example, neither hydralazine nor nifedipine should be used in patients who have severe headache and persistent tachycardia (pulse, >100 bpm). Labetalol should be avoided in women who have persistent bradycardia (pulse, <60 bpm), asthma, or congestive heart failure.

For women who have persistent headache and tachycardia, I suggest intravenous (IV) labetalol, starting at a dose of 20 mg, 40 mg, or 80 mg every 10 minutes as needed to keep systolic blood pressure below 160 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg. The maximum dose of labetalol should not exceed 300 mg in 1 hour.

For patients who have bradycardia and severe asthma, I suggest oral, rapid-acting nifedipine, starting at 10 mg to 20 mg, to be repeated in 20 to 30 minutes as needed, up to a maximum of 50 mg to 60 mg in 1 hour. Oral nifedipine can be used with magnesium sulfate. An alternative is an IV bolus injection of hydralazine, starting at a dose of 5 mg to 10 mg, to be repeated every 15 minutes, up to a maximum dose of 25 mg.

6. Avoid general anesthesia

Use neuraxial anesthesia for labor and delivery in eclampsia

Turner JA. Severe preeclampsia: anesthetic implications of the disease and its management. Am J Ther. 2009;16(4):284–248.

Huang CJ, Fan YC, Tsai PS. Differential impacts of modes of anaesthesia on the risk of stroke among preeclamptic women who undergo Cesarean delivery: a population-based study. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105(6):818–826.

Epidural, spinal, or combined anesthesia is safe in the absence of coagulopathy or severe thrombocytopenia. General anesthesia increases the risk of aspiration, failed intubation due to pharyngolaryngeal edema, and stroke secondary to the increase in systemic and intracerebral pressures during intubation and extubation.

Eclampsia is not an indication for cesarean delivery

Repke JT, Sibai BM. Preeclampsia and eclampsia. OBG Manage. 2009;21(4):44–55.

Once the mother has been resuscitated and stabilized, the provider should choose a mode of delivery that is based on fetal condition, gestational age, presence or absence of labor, and the cervical Bishop score. Vaginal delivery can be achieved in most patients who have a gestational age of 34 weeks or greater.

8. Late presentation happens

Be aware that eclampsia can develop for the first time as long as 28 days postpartum

Sibai BM, Stella CL. Diagnosis and management of atypical preeclampsia-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(5):481.e31–37.

Atypical eclampsia is any eclampsia that develops beyond 48 hours postpartum. A history of diagnosed predelivery preeclampsia is not necessary for development of late postpartum eclampsia. In general, more than 50% of patients who develop late postpartum eclampsia have no evidence of preeclampsia prior to delivery.

Be aware that the clinical and neuro-imaging features of eclampsia overlap with those of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (angiopathy)

Fletcher JJ, Kramer AH, Bleck TP, Solenski NJ. Overlapping features of eclampsia and postpartum angiopathy. Neurocrit Care. 2009;11(2):199–209.

Women who have reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome have clinical findings (acute onset of recurrent headaches, visual changes, seizures, and hypertension) and cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings (posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome) that are similar to those of women who have late postpartum eclampsia (FIGURE). However, in women who have postpartum cerebral angiopathy, cerebral angiography will show the presence of bead-like vasoconstriction—which is usually absent in eclampsia.

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

Green arrows point to vasogenic edema in the occipital lobes and, partially, the parietal lobes. The edema is gone on repeat magnetic resonance imaging (see Recommendation #9).

10. Act today, see a better outcome tomorrow

Avoid long-term maternal neurologic injury by managing eclampsia properly

Zeeman GG. Neurologic complications of preeclampsia. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33(3):166–172.

Residual neurologic damage is rare in the majority of women who have eclampsia. However, long-term cerebral white-matter injury (cytotoxic edema, infarction) on MRI imaging and impaired memory and cognitive function may develop in some women who have multiple seizures and who have inadequately controlled persistent severe hypertension.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Because eclampsia occurs but rarely during pregnancy and the postpartum period, most health-care providers have little to no personal experience with management of this life-threatening obstetric emergency. Knowledge about maternal resuscitation during and after an eclamptic seizure is critical for improving maternal and perinatal outcomes.

In this round-up, I present 10 practical recommendations for prompt diagnosis and management of women who have eclampsia. Immediate implementation of these recommendations can lead to improved maternal and perinatal outcomes (both acute and long-term).

1. Practice. Practice again.

Implement regular monthly simulation training sessions

Fisher N, Bernstein PS, Satin A, et al. Resident training for eclampsia and magnesium toxicity management: simulation or traditional lecture? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):379.e1–5.

Eclampsia is unpredictable and can develop rapidly at home, in labor and delivery, on the antepartum/postpartum ward, and in the emergency room. Therefore, it is prudent that all health-care providers who treat pregnant or postpartum women on a daily basis be trained and knowledgeable about early detection and management of eclampsia. This goal can be achieved by developing drills for rehearsal and by testing the response and skills of all providers.

2. Preventive: Magnesium sulfate

Do not attempt to arrest the seizure. Use MgSO4 to prevent recurrent convulsions.

Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Walker GJ, Chou D. Magnesium sulfate versus diazepam for eclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(12):CD000127.

Most eclamptic seizures are self-limiting. Therefore, there is no need to administer bolus drugs such as diazepam or midazolam. These drugs are usually used in the emergency room, but they inhibit maternal laryngeal reflexes and may lead to aspiration. They also suppress the central nervous system respiratory centers and can cause apnea, requiring intubation.

When used in the management of eclampsia, magnesium sulfate is associated with a lower rate of recurrent seizures and maternal death than is diazepam.

3. FHR changes? Be patient.

Do not rush the patient to emergent cesarean section because of an abnormal FHR tracing

Sibai BM. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):402–410.

During an eclamptic convulsion, there is usually prolonged fetal heart rate (FHR) deceleration or even bradycardia—with or without an increase in both frequency and uterine tone. After the convulsion, as a result of maternal hypoxia and hypercarbia, the FHR tracing can show tachycardia, reduced beat-to-beat variability, and transient recurrent decelerations. When this happens, concern about fetal status can distract the obstetric provider from resuscitation of the mother. However, these FHR changes usually return to normal after maternal resuscitation. If the FHR changes persist for longer than 15 minutes, consider abruptio placentae and move to delivery.

4. Target: Lower BP

Reduce maternal blood pressure to a safe level to prevent stroke, but without compromising uteroplacental perfusion

Zwart JJ, Richters A, Ory F, de Vries JI, Bloemenkamp KW, van Roosmalen J. Eclampsia in the Netherlands. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):820–827.

In this nationwide review of complications from eclampsia in the Netherlands, the authors found that failure to treat persistent severe hypertension was associated with hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebral infarction, bleeding, or congestive heart failure. They also found that 35.2% of women had systolic or diastolic blood pressure at or above 170/110 mm Hg at admission, but fewer than half were given antihypertensive drugs at that time. Among the cases deemed to have received substandard care, one third involved inadequate treatment of hypertension.

5. Know your antihypertensives

Learn which agents are best to control severe hypertension in eclampsia

Sibai BM. Hypertensive Emergencies. In: Foley MR, Strong TH, Garite TJ, eds. Obstetric Intensive Care Manual. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2010.

It is critical to familiarize oneself with the mechanism of action, dose, and potential side effects of agents used to control hypertension. For example, neither hydralazine nor nifedipine should be used in patients who have severe headache and persistent tachycardia (pulse, >100 bpm). Labetalol should be avoided in women who have persistent bradycardia (pulse, <60 bpm), asthma, or congestive heart failure.

For women who have persistent headache and tachycardia, I suggest intravenous (IV) labetalol, starting at a dose of 20 mg, 40 mg, or 80 mg every 10 minutes as needed to keep systolic blood pressure below 160 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg. The maximum dose of labetalol should not exceed 300 mg in 1 hour.

For patients who have bradycardia and severe asthma, I suggest oral, rapid-acting nifedipine, starting at 10 mg to 20 mg, to be repeated in 20 to 30 minutes as needed, up to a maximum of 50 mg to 60 mg in 1 hour. Oral nifedipine can be used with magnesium sulfate. An alternative is an IV bolus injection of hydralazine, starting at a dose of 5 mg to 10 mg, to be repeated every 15 minutes, up to a maximum dose of 25 mg.

6. Avoid general anesthesia

Use neuraxial anesthesia for labor and delivery in eclampsia

Turner JA. Severe preeclampsia: anesthetic implications of the disease and its management. Am J Ther. 2009;16(4):284–248.

Huang CJ, Fan YC, Tsai PS. Differential impacts of modes of anaesthesia on the risk of stroke among preeclamptic women who undergo Cesarean delivery: a population-based study. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105(6):818–826.

Epidural, spinal, or combined anesthesia is safe in the absence of coagulopathy or severe thrombocytopenia. General anesthesia increases the risk of aspiration, failed intubation due to pharyngolaryngeal edema, and stroke secondary to the increase in systemic and intracerebral pressures during intubation and extubation.

Eclampsia is not an indication for cesarean delivery

Repke JT, Sibai BM. Preeclampsia and eclampsia. OBG Manage. 2009;21(4):44–55.

Once the mother has been resuscitated and stabilized, the provider should choose a mode of delivery that is based on fetal condition, gestational age, presence or absence of labor, and the cervical Bishop score. Vaginal delivery can be achieved in most patients who have a gestational age of 34 weeks or greater.

8. Late presentation happens

Be aware that eclampsia can develop for the first time as long as 28 days postpartum

Sibai BM, Stella CL. Diagnosis and management of atypical preeclampsia-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(5):481.e31–37.

Atypical eclampsia is any eclampsia that develops beyond 48 hours postpartum. A history of diagnosed predelivery preeclampsia is not necessary for development of late postpartum eclampsia. In general, more than 50% of patients who develop late postpartum eclampsia have no evidence of preeclampsia prior to delivery.

Be aware that the clinical and neuro-imaging features of eclampsia overlap with those of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (angiopathy)

Fletcher JJ, Kramer AH, Bleck TP, Solenski NJ. Overlapping features of eclampsia and postpartum angiopathy. Neurocrit Care. 2009;11(2):199–209.

Women who have reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome have clinical findings (acute onset of recurrent headaches, visual changes, seizures, and hypertension) and cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings (posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome) that are similar to those of women who have late postpartum eclampsia (FIGURE). However, in women who have postpartum cerebral angiopathy, cerebral angiography will show the presence of bead-like vasoconstriction—which is usually absent in eclampsia.

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

Green arrows point to vasogenic edema in the occipital lobes and, partially, the parietal lobes. The edema is gone on repeat magnetic resonance imaging (see Recommendation #9).

10. Act today, see a better outcome tomorrow

Avoid long-term maternal neurologic injury by managing eclampsia properly

Zeeman GG. Neurologic complications of preeclampsia. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33(3):166–172.

Residual neurologic damage is rare in the majority of women who have eclampsia. However, long-term cerebral white-matter injury (cytotoxic edema, infarction) on MRI imaging and impaired memory and cognitive function may develop in some women who have multiple seizures and who have inadequately controlled persistent severe hypertension.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.