User login

ABSTRACT

Background: The Altman Rule, a simple tool for consumers seeking to make healthier packaged food choices at the point of sale, applies to packaged carbohydrates. According to the Altman Rule, a food is a healthier option if it has at least 3 g of fiber per serving and the grams of fiber plus the grams of protein exceed the grams of sugar per serving. This study sought to evaluate whether the Altman Rule is a valid proxy for glycemic load (GL).

Methods: We compared the binary outcome of whether a food item meets the Altman Rule with the GL of all foods categorized as cereals, chips, crackers, and granola bars in the Nutrition Data System for Research Database (University of Minnesota, Version 2010). We examined the percentage of foods in low-, medium-, and high-GL categories that met the Altman Rule.

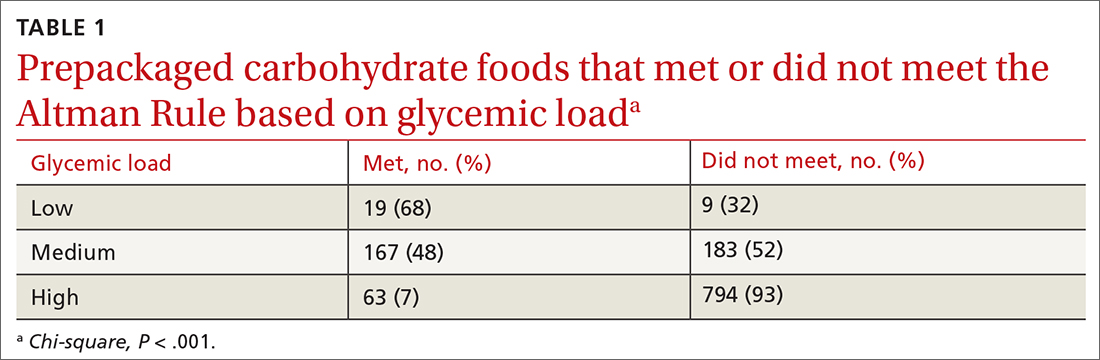

Results: There were 1235 foods (342 cereals, 305 chips, 379 crackers, and 209 granola bars) in this analysis. There was a significant relationship between the GL of foods and the Altman Rule (P < .001) in that most low-GL (68%), almost half of medium-GL (48%), and very few high-GL (7%) foods met the criteria of the rule.

Conclusions: The Altman Rule is a reasonable proxy for GL and can be a useful and accessible tool for consumers interested in buying healthier packaged carbohydrate foods.

Nutrition can be complicated for consumers interested in making healthier choices at the grocery store. Consumers may have difficulty identifying more nutritious options, especially when food labels are adorned with claims such as “Good Source of Fiber” or “Heart Healthy.”1 In addition, when reading food labels, consumers may find it difficult to decipher which data to prioritize when carbohydrates, total sugars, added sugars, total dietary fiber, soluble fiber, and insoluble fiber are all listed.

The concept of glycemic load (GL) is an important consideration, especially for people with diabetes. GL approximates the blood sugar response to different foods. A food with a high GL is digested quickly, and its carbohydrates are taken into the bloodstream rapidly. This leads to a spike and subsequent drop in blood sugars, which can cause symptoms of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in a person with diabetes.2,3 Despite its usefulness, GL may be too complicated for a consumer to understand, and it does not appear anywhere on the food label. Since GL is calculated using pooled blood sugar response from individuals after the ingestion of the particular food, estimation of the GL is not intuitable.4

Point-of-sale tools. People seeking to lose weight, control diabetes, improve dyslipidemia and/or blood pressure, and/or decrease their risk for heart disease may benefit from point-of-sale tools such as the Altman Rule, which simplifies and encourages the selection of more nutritious foods.1 Other tools—such as Guiding Stars (https://guidingstars.com), NuVal (www.nuval.com), and different variations of traffic lights—have been created to help consumers make more informed and healthier food choices.5-8 However, Guiding Stars and NuVal are based on complicated algorithms that are not entirely transparent and not accessible to the average consumer.6,7 Evaluations of these nutrition tools indicate that consumers tend to underrate the healthiness of some foods, such as raw almonds and salmon, and overrate the healthiness of others, such as fruit punch and diet soda, when using traffic light systems.6 Furthermore, these nutrition tools are not available in many supermarkets. Previous research suggests that the use of point-of-sale nutrition apps decreases with the time and effort involved in using an app.9

Continue to: The Altman Rule

The Altman Rule was developed by a family physician (author WA) to provide a more accessible tool for people interested in choosing healthier prepackaged carbohydrate foods while shopping. Since the user does not need to have a smartphone, and they are not required to download or understand an app for each purchase, the Altman Rule may be more usable compared with more complicated alternatives.

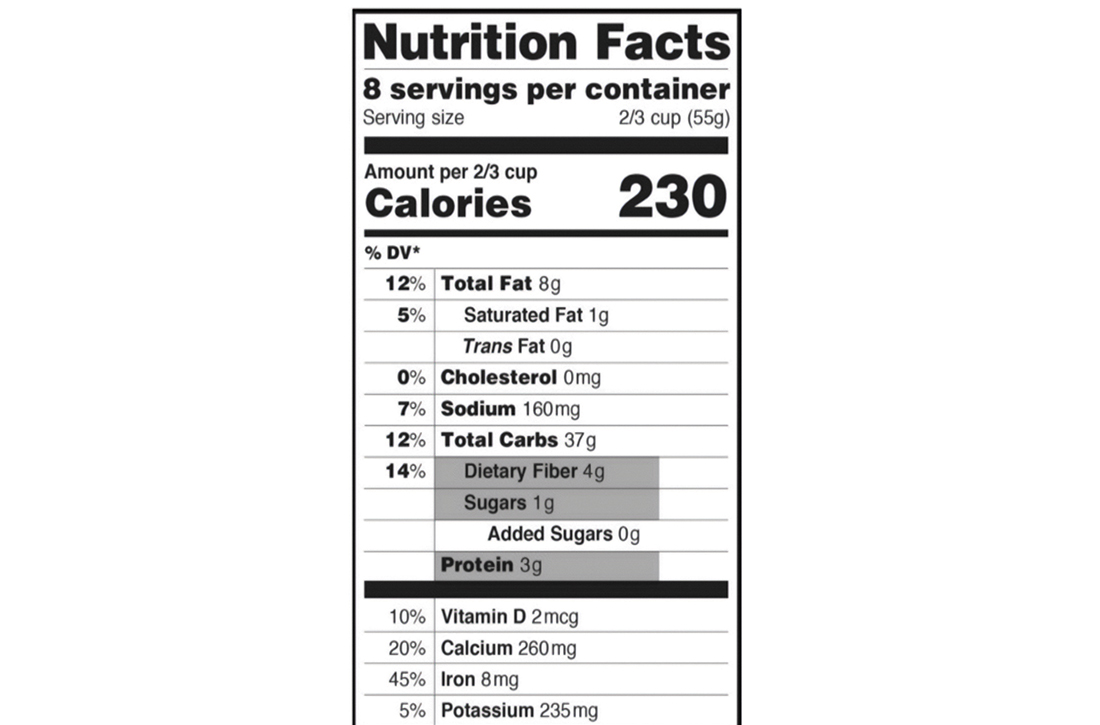

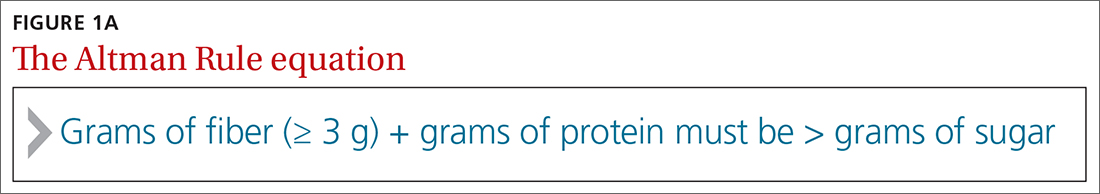

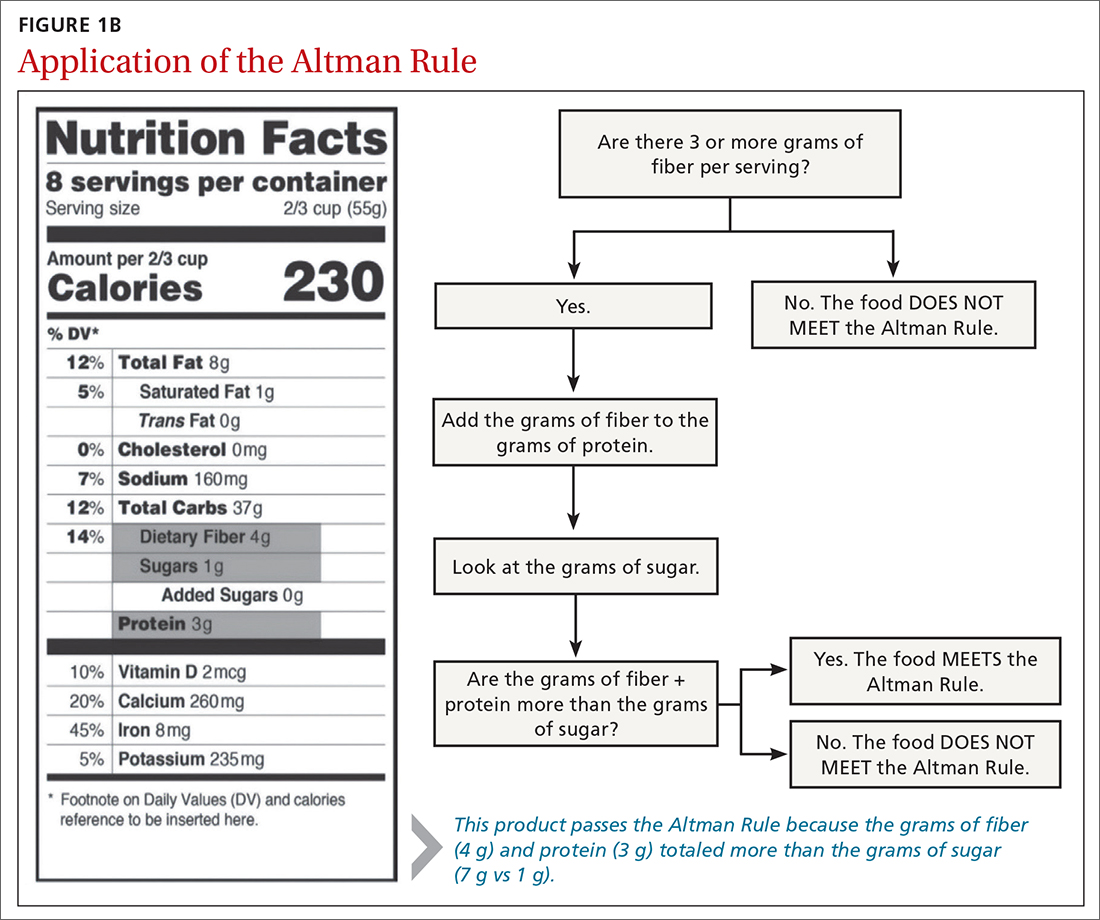

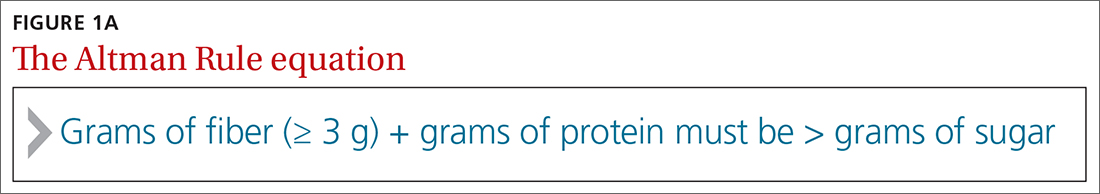

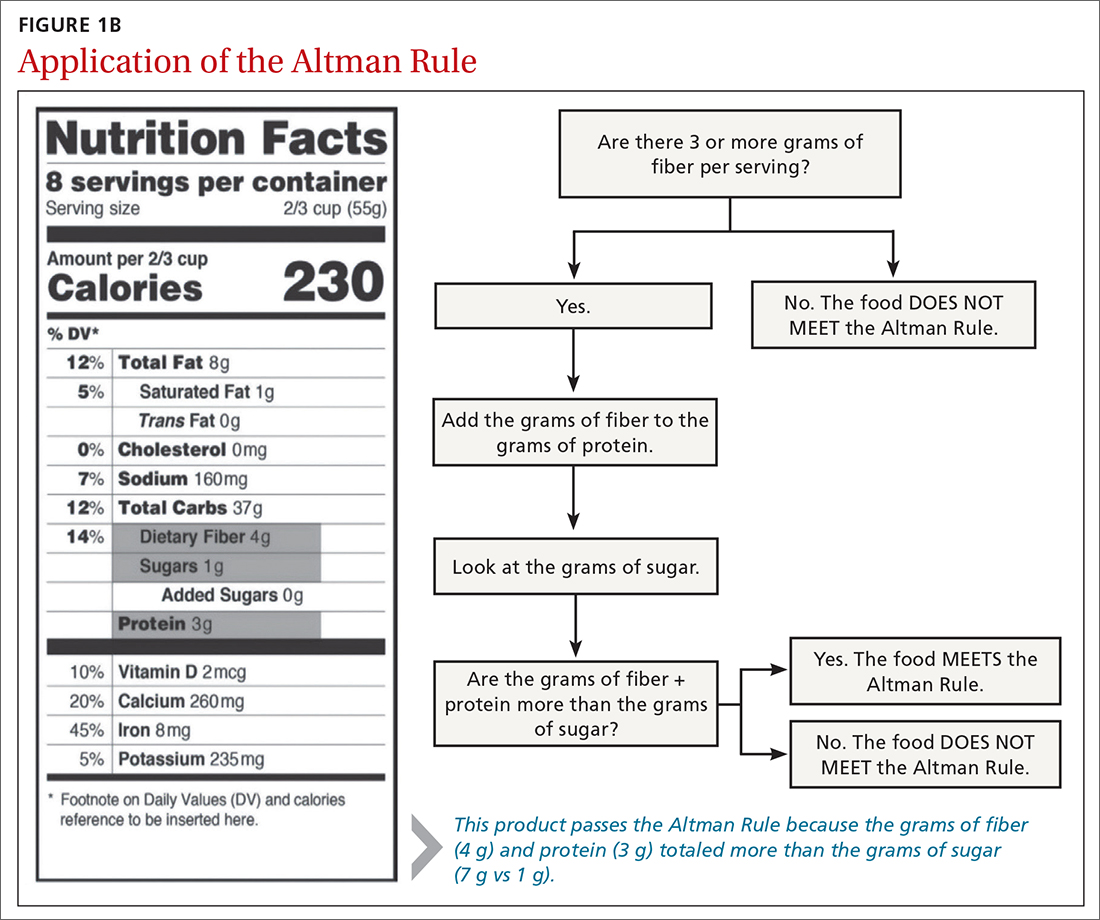

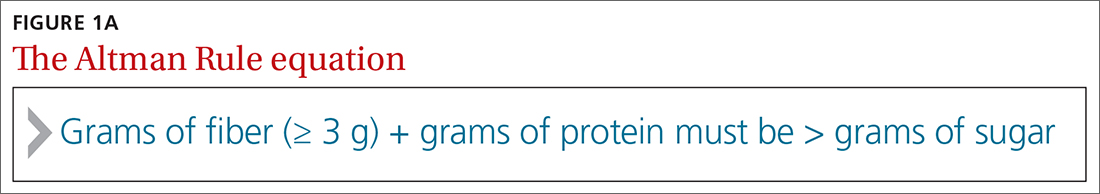

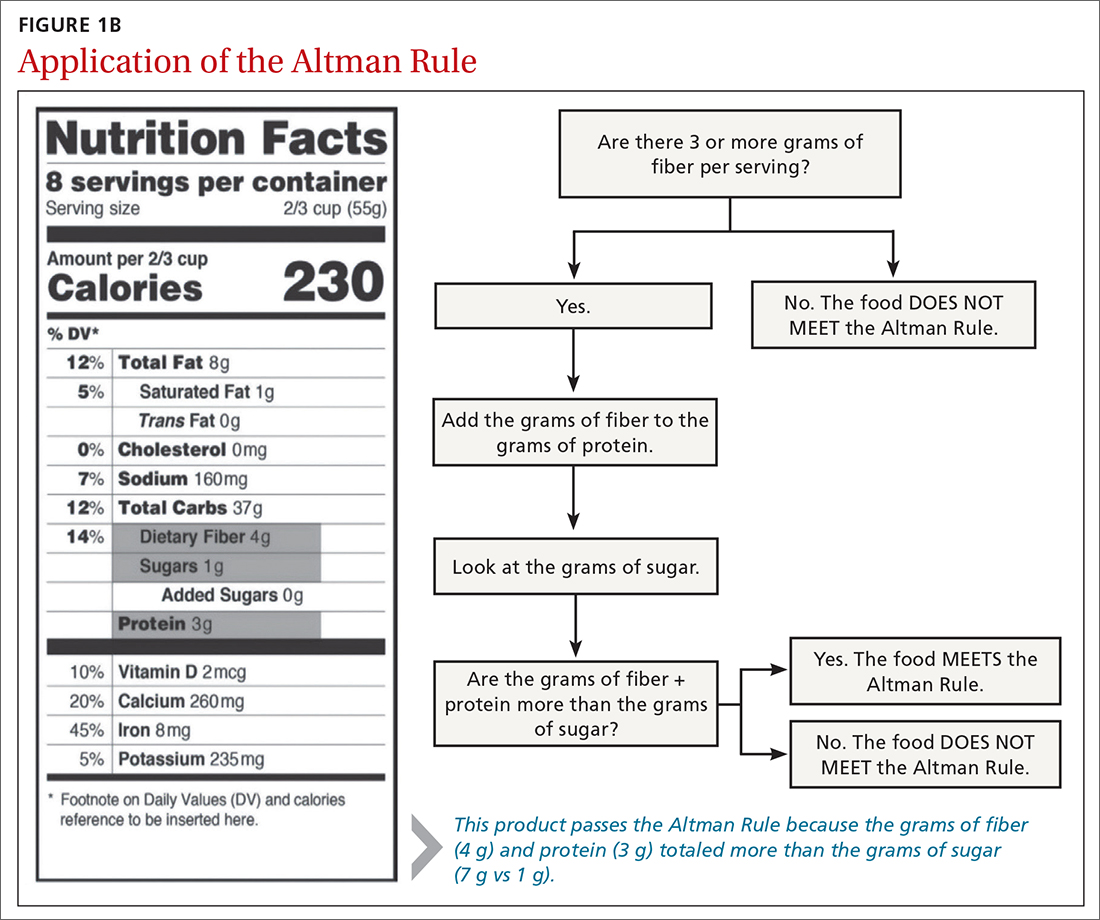

The Altman Rule can be used with nutrition labels that feature serving information and calories in enlarged and bold type, in compliance with the most recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guideline from 2016. Many foods with high fiber also have high amounts of sugar, so the criteria of the Altman Rule includes a 2-step process requiring (1) a minimum of 3 g of total dietary fiber per serving and (2) the sum of the grams of fiber plus the grams of protein per serving to be greater than the total grams of sugar (not grams of added sugar or grams of carbohydrate) per serving (FIGURE 1A). Unlike the relatively complicated formula related to GL, this 2-part rule can be applied in seconds while shopping (FIGURE 1B).

The rule is intended only to be used for packaged carbohydrate products, such as bread, muffins, bagels, pasta, rice, oatmeal, cereals, snack bars, chips, and crackers. It does not apply to whole foods, such as meat, dairy, fruits, or vegetables. These foods are excluded to prevent any consumer confusion related to the nutritional content of whole foods (eg, an apple may have more sugar than fiber and protein combined, but it is still a nutritious option).

This study aimed to determine if the Altman Rule is a reasonable proxy for the more complicated concept of GL. We calculated the relationship between the GL of commercially available packaged carbohydrate foods and whether those foods met the Altman Rule.

METHODS

The Altman Rule was tested by comparing the binary outcome of the rule (meets/does not meet) with data on all foods categorized as cereals, chips, crackers, and granola bars in the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) Database (University of Minnesota, Version 2010).

Continue to: To account for differences...

To account for differences in serving size, we used the standard of 50 g for each product as 1 serving. We used 50 g (about 1.7 oz) to help compare the different foods and between foods within the same group. Additionally, 50 g is close to 1 serving for most foods in these groups; it is about the size of a typical granola bar, three-quarters to 2 cups of cereal, 10 to 12 crackers, and 15 to 25 chips. We determined the GL for each product by multiplying the number of available carbohydrates (total carbohydrate – dietary fiber) by the product’s glycemic index/100. In general, GL is categorized as low (≤ 10), medium (11-19), or high (≥ 20).

We applied the Altman Rule to categorize each product as meeting or not meeting the rule. We compared the proportion of foods meeting the Altman Rule, stratified by GL and by specific foods, and used chi-square to determine if differences were statistically significant. These data were collected and analyzed in the summer of 2019.

RESULTS

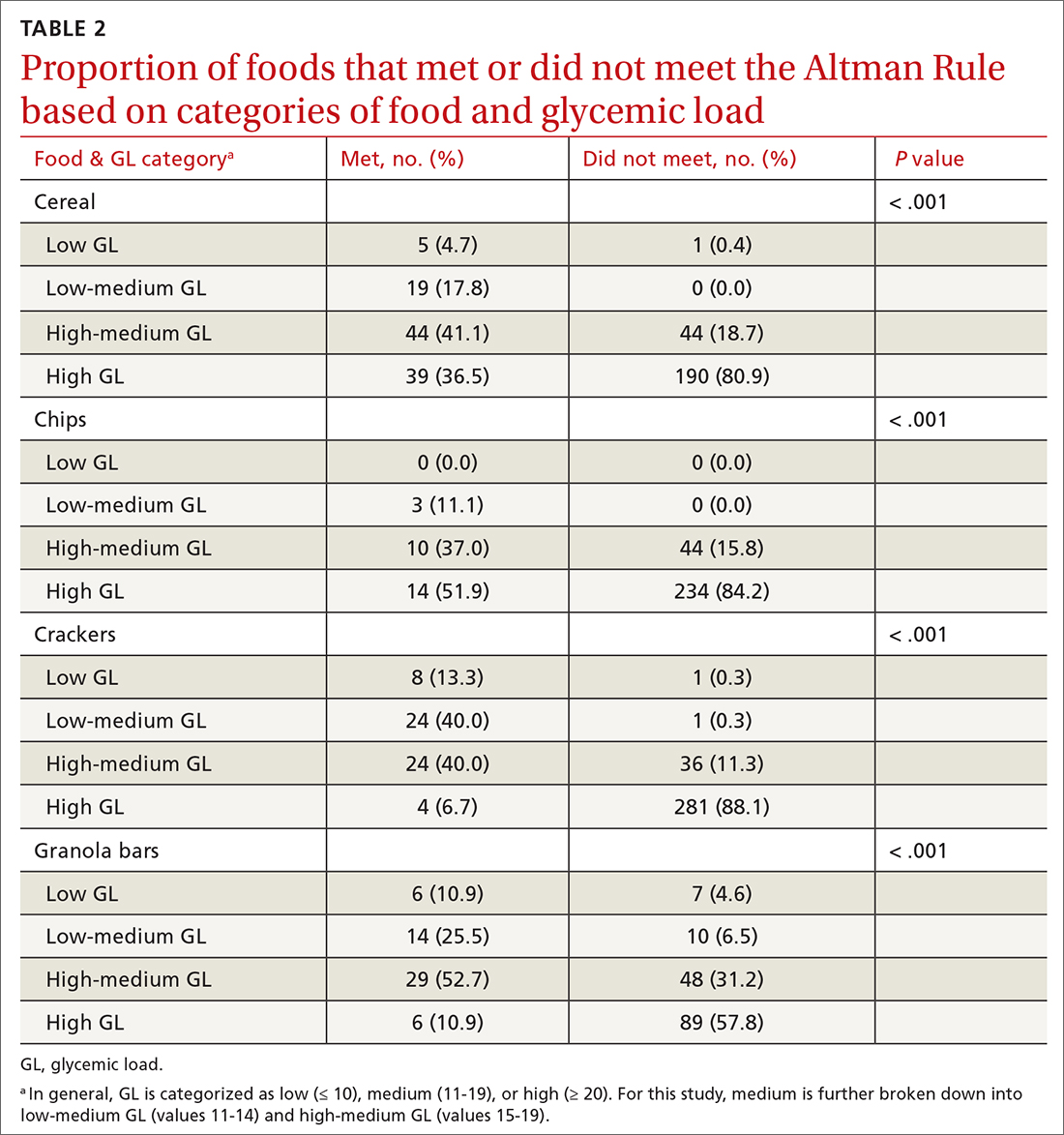

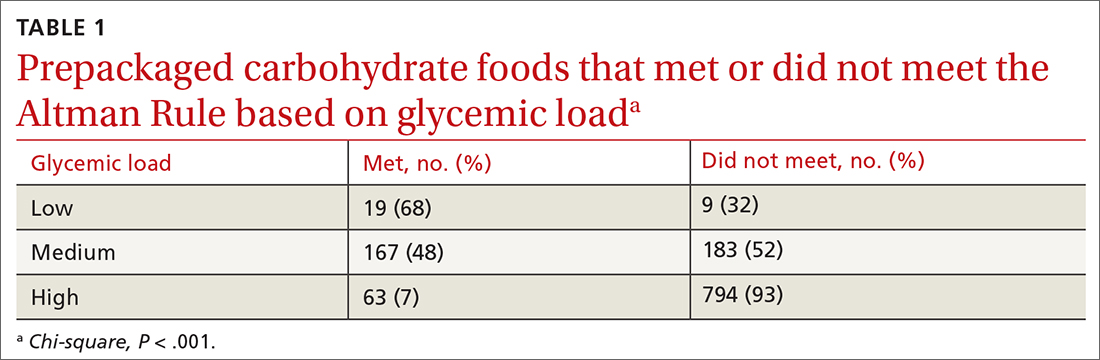

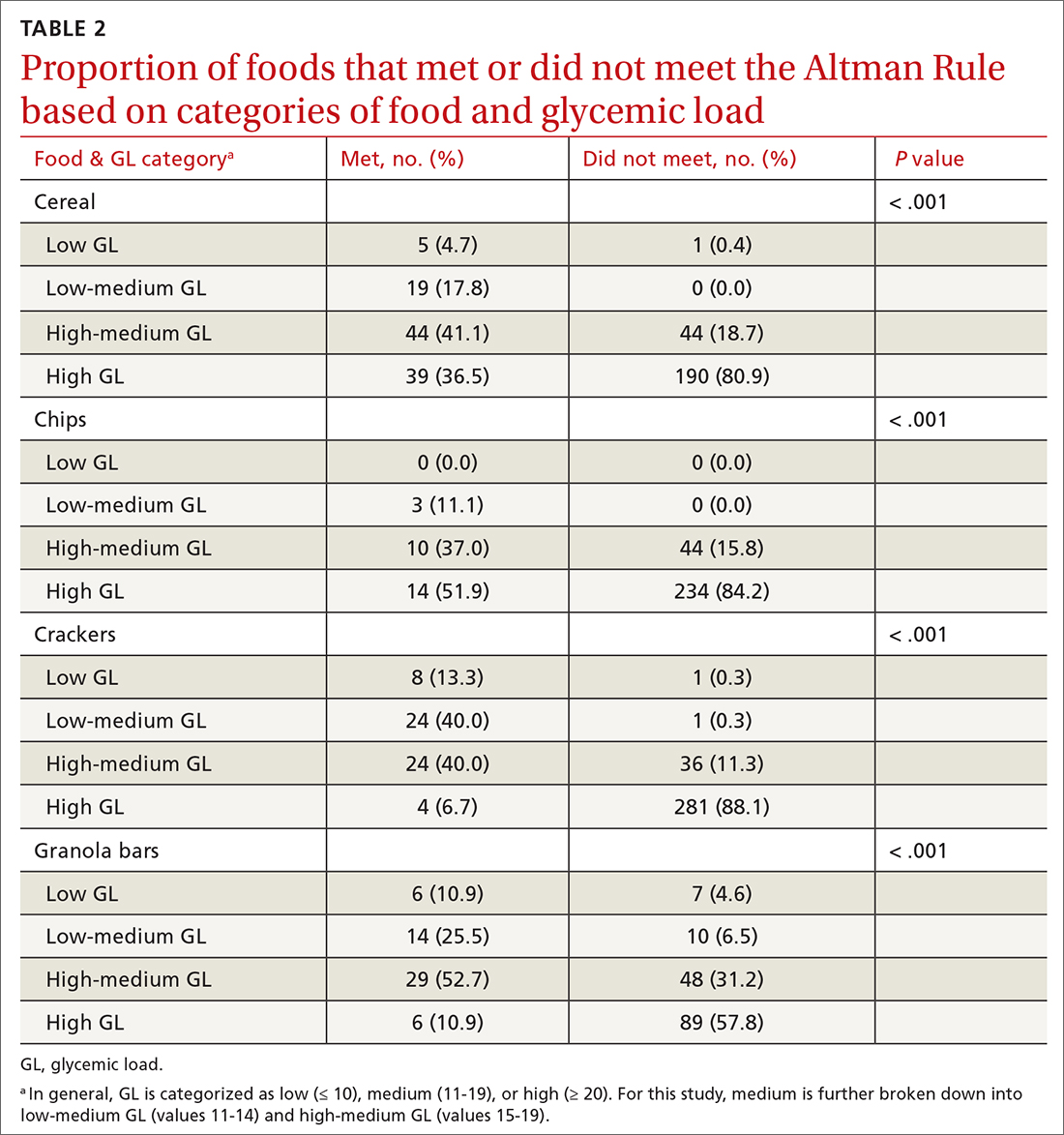

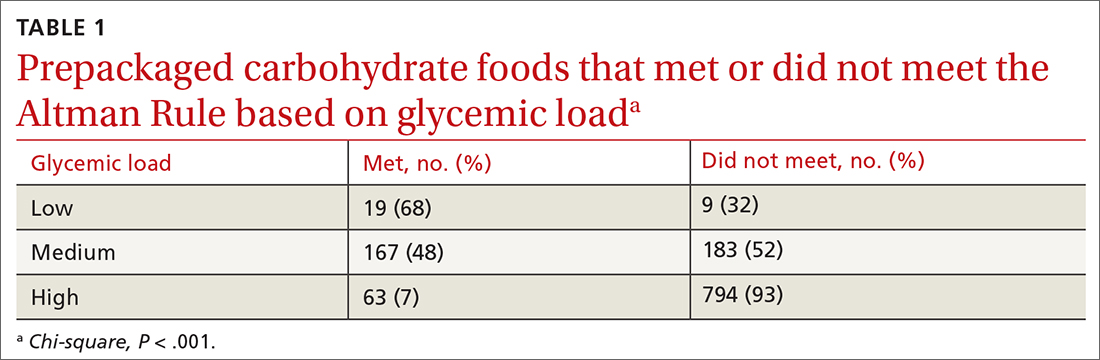

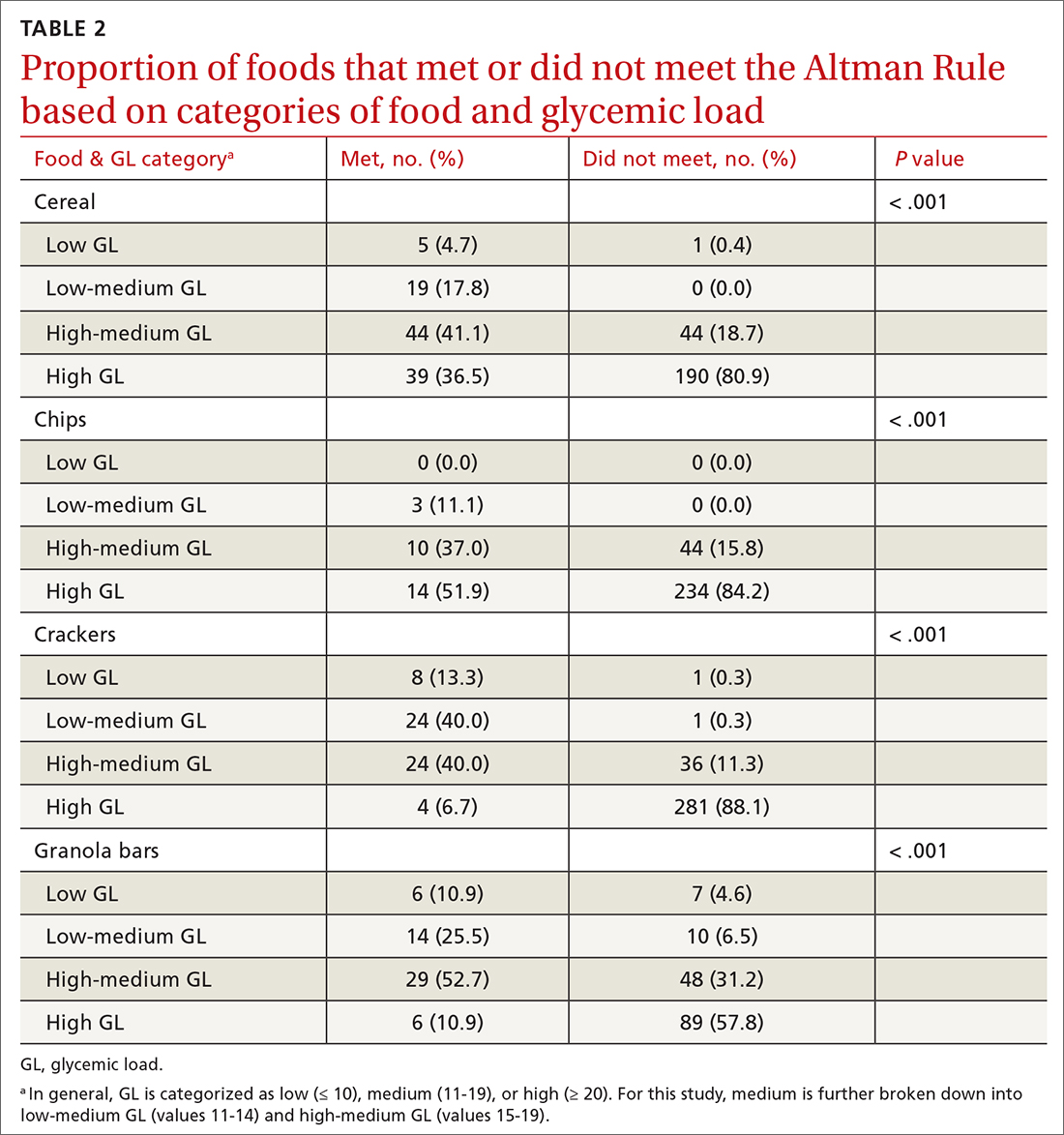

There were 1235 foods (342 breakfast cereals, 305 chips, 379 crackers, and 209 granola bars) used for this analysis. There is a significant relationship between the GL of foods and the Altman Rule in that most low-GL (68%), almost half of medium-GL (48%), and only a few high-GL foods (7%) met the rule (P < .001) (TABLE 1). There was also a significant relationship between “meeting the Altman Rule” and GL within each food type (P < .001) (TABLE 2).

The medium-GL foods were the second largest category of foods we calculated; thus we further broke them into binary categories of

Foods that met the rule were more likely to be low GL and foods that did not pass the rule were more likely high GL. Within the medium-GL category, foods that met the rule were more likely to be low-medium GL.

Continue to: The findings within food categories...

The findings within food categories showed that very few cereals, chips, crackers, and granola bars were low GL. For every food category, except granola bars, far more low-GL foods met the Altman Rule than those that did not. At the same time, very few high-GL foods met the Altman Rule. The category with the most individual high-GL food items meeting the Altman Rule was cereal. This was also the subcategory with the largest percentage of high-GL food items meeting the Altman Rule. Thirty-nine cereals that were high GL met the rule, but more than 4 times as many high-GL cereals did not (n = 190).

DISCUSSION

Marketing and nutrition messaging create consumer confusion that makes it challenging to identify packaged food items that are more nutrient dense. The Altman Rule simplifies food choices that have become unnecessarily complex. Our findings suggest this 2-step rule is a reasonable proxy for the more complicated and less accessible GL for packaged carbohydrates, such as cereals, chips, crackers, and snack bars. Foods that meet the rule are likely low or low-medium GL and thus are foods that are likely to be healthier choices.

Of note, only 9% of chips (n = 27) passed the Altman Rule, likely due to their low dietary fiber content, which was typical of chips. If a food item does not have at least 3 grams of total dietary fiber per serving, it does not pass the Altman Rule, regardless of how much protein or sugar is in the product. This may be considered a strength or a weakness of the Altman Rule. Few nutrition-dense foods are low in fiber, but some foods could be nutritious but do not meet the Altman Rule due to having < 3 g of fiber.

With the high prevalence of chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease, it is essential to help consumers prevent chronic disease altogether or manage their chronic disease by providing tools to identify healthier food choices. The tool also has a place in clinical medicine for use by physicians and other health care professionals. Research shows that physicians find both time and lack of knowledge/resources to be a barrier to providing nutritional counseling to patients.10 Since the Altman Rule can be shared and explained with very little time and without extensive nutritional knowledge, it meets these needs.

Limitations

Glycemic load. We acknowledge that the Altman Rule is not foolproof and that assessing this rule based on GL has some limitations. GL is not a perfect or comprehensive way to measure the nutritional value of a food. For example, fruits such as watermelon and grapes are nutritionally dense. However, they contain high amounts of natural sugars—and as such, their GL is relatively high, which could lead a consumer to perceive them as unhealthy. Nevertheless, GL is both a useful and accepted tool and a reasonable way to assess the validity of the rule, specifically when assessing packaged carbohydrates. The simplicity of the Altman Rule and its relationship with GL makes it such that consumers are more likely to make a healthier food choice using it.9

Continue to: Specificity and sensitivity

Specificity and sensitivity. There are other limitations to the Altman Rule, given that a small number of high-GL foods meet the rule. For example, some granola bars had high dietary protein, which offset a high sugar content just enough to pass the rule despite a higher GL. As such, concluding that a snack bar is a healthier choice because it meets the Altman Rule when it has high amounts of sugar may not be appropriate. This limitation could be considered a lack of specificity (the rule includes food it ought not to include). Another limitation to consider would be a lack of sensitivity, given that only 68% of low-GL foods passed the Altman Rule. Since GL is associated with carbohydrate content, foods with a low carbohydrate count often have little to no fiber and thus would fall into the category of foods that did not meet the Altman Rule but had low GL. In this case, however, the low amount of fiber may render the Altman Rule a better indicator of a healthier food choice than the GL.

Hidden sugars. Foods with sugar alcohols and artificial sweeteners may be as deleterious as caloric alternatives while not being accounted for when reporting the grams of sugar per serving on the nutrition label.7 This may represent an exception to the Altman Rule, as foods that are not healthier choices may pass the rule because the sugar content on the nutrition label is, in a sense, artificially lowered. Future research may investigate the hypothesis that these foods are nutritionally inferior despite meeting the Altman Rule.

The sample. Our study also was limited to working only with foods that were included in the NDSR database up to 2010. This limitation is mitigated by the fact that the sample size was large (> 1000 packaged food items were included in our analyses). The study also could be limited by the food categories that were analyzed; food categories such as bread, rice, pasta, and bagels were not included.

The objective of this research was to investigate the relationship between GL and the Altman Rule, rather than to conduct an exhaustive analysis of the Altman Rule for every possible food category. Studying the relationship between the Altman Rule and GL in other categories of food is an objective for future research. The data so far support a relationship between these entities. The likelihood of the nutrition facts of foods changing without the GL changing (or vice versa) is very low. As such, the Altman Rule still seems to be a reasonable proxy of GL.

CONCLUSIONS

Research indicates that point-of-sale tools, such as Guiding Stars, NuVal, and other stoplight tools, can successfully alter consumers’ behaviors.9 These tools can be helpful but are not available in many supermarkets. Despite the limitations, the Altman Rule is a useful decision aid that is accessible to all consumers no matter where they live or shop and is easy to use and remember.

The Altman rule can be used in clinical practice by health care professionals, such as physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, dietitians, and health coaches. It also has the potential to be used in commercial settings, such as grocery stores, to help consumers easily identify healthier convenience foods. This has public health implications, as the rule can both empower consumers and potentially incentivize food manufacturers to upgrade their products nutritionally.

Additional research would be useful to evaluate consumers’ preferences and perceptions about how user-friendly the Altman Rule is at the point of sale with packaged carbohydrate foods. This would help to further understand how the use of information on food packaging can motivate healthier decisions—thereby helping to alleviate the burden of chronic disease.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kimberly R. Dong, DrPH, MS, RDN, Tufts University School of Medicine, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, 136 Harrison Avenue, MV Building, Boston, MA 02111; kimberly.dong@tufts.edu

1. Hersey JC, Wohlgenant KC, Arsenault JE, et al. Effects of front-of-package and shelf nutrition labeling systems on consumers. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:1-14. doi: 10.1111/nure.12000

2. Jenkins DJA, Dehghan M, Mente A, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and cardiovascular disease and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1312-1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007123

3. Brand-Miller J, Hayne S, Petocz P, et al. Low–glycemic index diets in the management of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2261-2267. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2261

4. Matthan NR, Ausman LM, Meng H, et al. Estimating the reliability of glycemic index values and potential sources of methodological and biological variability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:1004-1013. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.137208

5. Sonnenberg L, Gelsomin E, Levy DE, et al. A traffic light food labeling intervention increases consumer awareness of health and healthy choices at the point-of-purchase. Prev Med. 2013;57:253-257. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.07.001

6. Savoie N, Barlow K, Harvey KL, et al. Consumer perceptions of front-of-package labelling systems and healthiness of foods. Can J Public Health. 2013;104:e359-e363. doi: 10.17269/cjph.104.4027

7. Fischer LM, Sutherland LA, Kaley LA, et al. Development and implementation of the Guiding Stars nutrition guidance program. Am J Health Promot. 2011;26:e55-e63. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.100709-QUAL-238

8. Maubach N, Hoek J, Mather D. Interpretive front-of-pack nutrition labels. Comparing competing recommendations. Appetite. 2014;82:67-77. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.07.006

9. Chan J, McMahon E, Brimblecombe J. Point‐of‐sale nutrition information interventions in food retail stores to promote healthier food purchase and intake: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2021;22. doi: 10.1111/obr.13311

10. Mathioudakis N, Bashura H, Boyér L, et al. Development, implementation, and evaluation of a physician-targeted inpatient glycemic management curriculum. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:238212051986134. doi: 10.1177/2382120519861342

ABSTRACT

Background: The Altman Rule, a simple tool for consumers seeking to make healthier packaged food choices at the point of sale, applies to packaged carbohydrates. According to the Altman Rule, a food is a healthier option if it has at least 3 g of fiber per serving and the grams of fiber plus the grams of protein exceed the grams of sugar per serving. This study sought to evaluate whether the Altman Rule is a valid proxy for glycemic load (GL).

Methods: We compared the binary outcome of whether a food item meets the Altman Rule with the GL of all foods categorized as cereals, chips, crackers, and granola bars in the Nutrition Data System for Research Database (University of Minnesota, Version 2010). We examined the percentage of foods in low-, medium-, and high-GL categories that met the Altman Rule.

Results: There were 1235 foods (342 cereals, 305 chips, 379 crackers, and 209 granola bars) in this analysis. There was a significant relationship between the GL of foods and the Altman Rule (P < .001) in that most low-GL (68%), almost half of medium-GL (48%), and very few high-GL (7%) foods met the criteria of the rule.

Conclusions: The Altman Rule is a reasonable proxy for GL and can be a useful and accessible tool for consumers interested in buying healthier packaged carbohydrate foods.

Nutrition can be complicated for consumers interested in making healthier choices at the grocery store. Consumers may have difficulty identifying more nutritious options, especially when food labels are adorned with claims such as “Good Source of Fiber” or “Heart Healthy.”1 In addition, when reading food labels, consumers may find it difficult to decipher which data to prioritize when carbohydrates, total sugars, added sugars, total dietary fiber, soluble fiber, and insoluble fiber are all listed.

The concept of glycemic load (GL) is an important consideration, especially for people with diabetes. GL approximates the blood sugar response to different foods. A food with a high GL is digested quickly, and its carbohydrates are taken into the bloodstream rapidly. This leads to a spike and subsequent drop in blood sugars, which can cause symptoms of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in a person with diabetes.2,3 Despite its usefulness, GL may be too complicated for a consumer to understand, and it does not appear anywhere on the food label. Since GL is calculated using pooled blood sugar response from individuals after the ingestion of the particular food, estimation of the GL is not intuitable.4

Point-of-sale tools. People seeking to lose weight, control diabetes, improve dyslipidemia and/or blood pressure, and/or decrease their risk for heart disease may benefit from point-of-sale tools such as the Altman Rule, which simplifies and encourages the selection of more nutritious foods.1 Other tools—such as Guiding Stars (https://guidingstars.com), NuVal (www.nuval.com), and different variations of traffic lights—have been created to help consumers make more informed and healthier food choices.5-8 However, Guiding Stars and NuVal are based on complicated algorithms that are not entirely transparent and not accessible to the average consumer.6,7 Evaluations of these nutrition tools indicate that consumers tend to underrate the healthiness of some foods, such as raw almonds and salmon, and overrate the healthiness of others, such as fruit punch and diet soda, when using traffic light systems.6 Furthermore, these nutrition tools are not available in many supermarkets. Previous research suggests that the use of point-of-sale nutrition apps decreases with the time and effort involved in using an app.9

Continue to: The Altman Rule

The Altman Rule was developed by a family physician (author WA) to provide a more accessible tool for people interested in choosing healthier prepackaged carbohydrate foods while shopping. Since the user does not need to have a smartphone, and they are not required to download or understand an app for each purchase, the Altman Rule may be more usable compared with more complicated alternatives.

The Altman Rule can be used with nutrition labels that feature serving information and calories in enlarged and bold type, in compliance with the most recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guideline from 2016. Many foods with high fiber also have high amounts of sugar, so the criteria of the Altman Rule includes a 2-step process requiring (1) a minimum of 3 g of total dietary fiber per serving and (2) the sum of the grams of fiber plus the grams of protein per serving to be greater than the total grams of sugar (not grams of added sugar or grams of carbohydrate) per serving (FIGURE 1A). Unlike the relatively complicated formula related to GL, this 2-part rule can be applied in seconds while shopping (FIGURE 1B).

The rule is intended only to be used for packaged carbohydrate products, such as bread, muffins, bagels, pasta, rice, oatmeal, cereals, snack bars, chips, and crackers. It does not apply to whole foods, such as meat, dairy, fruits, or vegetables. These foods are excluded to prevent any consumer confusion related to the nutritional content of whole foods (eg, an apple may have more sugar than fiber and protein combined, but it is still a nutritious option).

This study aimed to determine if the Altman Rule is a reasonable proxy for the more complicated concept of GL. We calculated the relationship between the GL of commercially available packaged carbohydrate foods and whether those foods met the Altman Rule.

METHODS

The Altman Rule was tested by comparing the binary outcome of the rule (meets/does not meet) with data on all foods categorized as cereals, chips, crackers, and granola bars in the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) Database (University of Minnesota, Version 2010).

Continue to: To account for differences...

To account for differences in serving size, we used the standard of 50 g for each product as 1 serving. We used 50 g (about 1.7 oz) to help compare the different foods and between foods within the same group. Additionally, 50 g is close to 1 serving for most foods in these groups; it is about the size of a typical granola bar, three-quarters to 2 cups of cereal, 10 to 12 crackers, and 15 to 25 chips. We determined the GL for each product by multiplying the number of available carbohydrates (total carbohydrate – dietary fiber) by the product’s glycemic index/100. In general, GL is categorized as low (≤ 10), medium (11-19), or high (≥ 20).

We applied the Altman Rule to categorize each product as meeting or not meeting the rule. We compared the proportion of foods meeting the Altman Rule, stratified by GL and by specific foods, and used chi-square to determine if differences were statistically significant. These data were collected and analyzed in the summer of 2019.

RESULTS

There were 1235 foods (342 breakfast cereals, 305 chips, 379 crackers, and 209 granola bars) used for this analysis. There is a significant relationship between the GL of foods and the Altman Rule in that most low-GL (68%), almost half of medium-GL (48%), and only a few high-GL foods (7%) met the rule (P < .001) (TABLE 1). There was also a significant relationship between “meeting the Altman Rule” and GL within each food type (P < .001) (TABLE 2).

The medium-GL foods were the second largest category of foods we calculated; thus we further broke them into binary categories of

Foods that met the rule were more likely to be low GL and foods that did not pass the rule were more likely high GL. Within the medium-GL category, foods that met the rule were more likely to be low-medium GL.

Continue to: The findings within food categories...

The findings within food categories showed that very few cereals, chips, crackers, and granola bars were low GL. For every food category, except granola bars, far more low-GL foods met the Altman Rule than those that did not. At the same time, very few high-GL foods met the Altman Rule. The category with the most individual high-GL food items meeting the Altman Rule was cereal. This was also the subcategory with the largest percentage of high-GL food items meeting the Altman Rule. Thirty-nine cereals that were high GL met the rule, but more than 4 times as many high-GL cereals did not (n = 190).

DISCUSSION

Marketing and nutrition messaging create consumer confusion that makes it challenging to identify packaged food items that are more nutrient dense. The Altman Rule simplifies food choices that have become unnecessarily complex. Our findings suggest this 2-step rule is a reasonable proxy for the more complicated and less accessible GL for packaged carbohydrates, such as cereals, chips, crackers, and snack bars. Foods that meet the rule are likely low or low-medium GL and thus are foods that are likely to be healthier choices.

Of note, only 9% of chips (n = 27) passed the Altman Rule, likely due to their low dietary fiber content, which was typical of chips. If a food item does not have at least 3 grams of total dietary fiber per serving, it does not pass the Altman Rule, regardless of how much protein or sugar is in the product. This may be considered a strength or a weakness of the Altman Rule. Few nutrition-dense foods are low in fiber, but some foods could be nutritious but do not meet the Altman Rule due to having < 3 g of fiber.

With the high prevalence of chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease, it is essential to help consumers prevent chronic disease altogether or manage their chronic disease by providing tools to identify healthier food choices. The tool also has a place in clinical medicine for use by physicians and other health care professionals. Research shows that physicians find both time and lack of knowledge/resources to be a barrier to providing nutritional counseling to patients.10 Since the Altman Rule can be shared and explained with very little time and without extensive nutritional knowledge, it meets these needs.

Limitations

Glycemic load. We acknowledge that the Altman Rule is not foolproof and that assessing this rule based on GL has some limitations. GL is not a perfect or comprehensive way to measure the nutritional value of a food. For example, fruits such as watermelon and grapes are nutritionally dense. However, they contain high amounts of natural sugars—and as such, their GL is relatively high, which could lead a consumer to perceive them as unhealthy. Nevertheless, GL is both a useful and accepted tool and a reasonable way to assess the validity of the rule, specifically when assessing packaged carbohydrates. The simplicity of the Altman Rule and its relationship with GL makes it such that consumers are more likely to make a healthier food choice using it.9

Continue to: Specificity and sensitivity

Specificity and sensitivity. There are other limitations to the Altman Rule, given that a small number of high-GL foods meet the rule. For example, some granola bars had high dietary protein, which offset a high sugar content just enough to pass the rule despite a higher GL. As such, concluding that a snack bar is a healthier choice because it meets the Altman Rule when it has high amounts of sugar may not be appropriate. This limitation could be considered a lack of specificity (the rule includes food it ought not to include). Another limitation to consider would be a lack of sensitivity, given that only 68% of low-GL foods passed the Altman Rule. Since GL is associated with carbohydrate content, foods with a low carbohydrate count often have little to no fiber and thus would fall into the category of foods that did not meet the Altman Rule but had low GL. In this case, however, the low amount of fiber may render the Altman Rule a better indicator of a healthier food choice than the GL.

Hidden sugars. Foods with sugar alcohols and artificial sweeteners may be as deleterious as caloric alternatives while not being accounted for when reporting the grams of sugar per serving on the nutrition label.7 This may represent an exception to the Altman Rule, as foods that are not healthier choices may pass the rule because the sugar content on the nutrition label is, in a sense, artificially lowered. Future research may investigate the hypothesis that these foods are nutritionally inferior despite meeting the Altman Rule.

The sample. Our study also was limited to working only with foods that were included in the NDSR database up to 2010. This limitation is mitigated by the fact that the sample size was large (> 1000 packaged food items were included in our analyses). The study also could be limited by the food categories that were analyzed; food categories such as bread, rice, pasta, and bagels were not included.

The objective of this research was to investigate the relationship between GL and the Altman Rule, rather than to conduct an exhaustive analysis of the Altman Rule for every possible food category. Studying the relationship between the Altman Rule and GL in other categories of food is an objective for future research. The data so far support a relationship between these entities. The likelihood of the nutrition facts of foods changing without the GL changing (or vice versa) is very low. As such, the Altman Rule still seems to be a reasonable proxy of GL.

CONCLUSIONS

Research indicates that point-of-sale tools, such as Guiding Stars, NuVal, and other stoplight tools, can successfully alter consumers’ behaviors.9 These tools can be helpful but are not available in many supermarkets. Despite the limitations, the Altman Rule is a useful decision aid that is accessible to all consumers no matter where they live or shop and is easy to use and remember.

The Altman rule can be used in clinical practice by health care professionals, such as physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, dietitians, and health coaches. It also has the potential to be used in commercial settings, such as grocery stores, to help consumers easily identify healthier convenience foods. This has public health implications, as the rule can both empower consumers and potentially incentivize food manufacturers to upgrade their products nutritionally.

Additional research would be useful to evaluate consumers’ preferences and perceptions about how user-friendly the Altman Rule is at the point of sale with packaged carbohydrate foods. This would help to further understand how the use of information on food packaging can motivate healthier decisions—thereby helping to alleviate the burden of chronic disease.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kimberly R. Dong, DrPH, MS, RDN, Tufts University School of Medicine, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, 136 Harrison Avenue, MV Building, Boston, MA 02111; kimberly.dong@tufts.edu

ABSTRACT

Background: The Altman Rule, a simple tool for consumers seeking to make healthier packaged food choices at the point of sale, applies to packaged carbohydrates. According to the Altman Rule, a food is a healthier option if it has at least 3 g of fiber per serving and the grams of fiber plus the grams of protein exceed the grams of sugar per serving. This study sought to evaluate whether the Altman Rule is a valid proxy for glycemic load (GL).

Methods: We compared the binary outcome of whether a food item meets the Altman Rule with the GL of all foods categorized as cereals, chips, crackers, and granola bars in the Nutrition Data System for Research Database (University of Minnesota, Version 2010). We examined the percentage of foods in low-, medium-, and high-GL categories that met the Altman Rule.

Results: There were 1235 foods (342 cereals, 305 chips, 379 crackers, and 209 granola bars) in this analysis. There was a significant relationship between the GL of foods and the Altman Rule (P < .001) in that most low-GL (68%), almost half of medium-GL (48%), and very few high-GL (7%) foods met the criteria of the rule.

Conclusions: The Altman Rule is a reasonable proxy for GL and can be a useful and accessible tool for consumers interested in buying healthier packaged carbohydrate foods.

Nutrition can be complicated for consumers interested in making healthier choices at the grocery store. Consumers may have difficulty identifying more nutritious options, especially when food labels are adorned with claims such as “Good Source of Fiber” or “Heart Healthy.”1 In addition, when reading food labels, consumers may find it difficult to decipher which data to prioritize when carbohydrates, total sugars, added sugars, total dietary fiber, soluble fiber, and insoluble fiber are all listed.

The concept of glycemic load (GL) is an important consideration, especially for people with diabetes. GL approximates the blood sugar response to different foods. A food with a high GL is digested quickly, and its carbohydrates are taken into the bloodstream rapidly. This leads to a spike and subsequent drop in blood sugars, which can cause symptoms of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in a person with diabetes.2,3 Despite its usefulness, GL may be too complicated for a consumer to understand, and it does not appear anywhere on the food label. Since GL is calculated using pooled blood sugar response from individuals after the ingestion of the particular food, estimation of the GL is not intuitable.4

Point-of-sale tools. People seeking to lose weight, control diabetes, improve dyslipidemia and/or blood pressure, and/or decrease their risk for heart disease may benefit from point-of-sale tools such as the Altman Rule, which simplifies and encourages the selection of more nutritious foods.1 Other tools—such as Guiding Stars (https://guidingstars.com), NuVal (www.nuval.com), and different variations of traffic lights—have been created to help consumers make more informed and healthier food choices.5-8 However, Guiding Stars and NuVal are based on complicated algorithms that are not entirely transparent and not accessible to the average consumer.6,7 Evaluations of these nutrition tools indicate that consumers tend to underrate the healthiness of some foods, such as raw almonds and salmon, and overrate the healthiness of others, such as fruit punch and diet soda, when using traffic light systems.6 Furthermore, these nutrition tools are not available in many supermarkets. Previous research suggests that the use of point-of-sale nutrition apps decreases with the time and effort involved in using an app.9

Continue to: The Altman Rule

The Altman Rule was developed by a family physician (author WA) to provide a more accessible tool for people interested in choosing healthier prepackaged carbohydrate foods while shopping. Since the user does not need to have a smartphone, and they are not required to download or understand an app for each purchase, the Altman Rule may be more usable compared with more complicated alternatives.

The Altman Rule can be used with nutrition labels that feature serving information and calories in enlarged and bold type, in compliance with the most recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guideline from 2016. Many foods with high fiber also have high amounts of sugar, so the criteria of the Altman Rule includes a 2-step process requiring (1) a minimum of 3 g of total dietary fiber per serving and (2) the sum of the grams of fiber plus the grams of protein per serving to be greater than the total grams of sugar (not grams of added sugar or grams of carbohydrate) per serving (FIGURE 1A). Unlike the relatively complicated formula related to GL, this 2-part rule can be applied in seconds while shopping (FIGURE 1B).

The rule is intended only to be used for packaged carbohydrate products, such as bread, muffins, bagels, pasta, rice, oatmeal, cereals, snack bars, chips, and crackers. It does not apply to whole foods, such as meat, dairy, fruits, or vegetables. These foods are excluded to prevent any consumer confusion related to the nutritional content of whole foods (eg, an apple may have more sugar than fiber and protein combined, but it is still a nutritious option).

This study aimed to determine if the Altman Rule is a reasonable proxy for the more complicated concept of GL. We calculated the relationship between the GL of commercially available packaged carbohydrate foods and whether those foods met the Altman Rule.

METHODS

The Altman Rule was tested by comparing the binary outcome of the rule (meets/does not meet) with data on all foods categorized as cereals, chips, crackers, and granola bars in the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) Database (University of Minnesota, Version 2010).

Continue to: To account for differences...

To account for differences in serving size, we used the standard of 50 g for each product as 1 serving. We used 50 g (about 1.7 oz) to help compare the different foods and between foods within the same group. Additionally, 50 g is close to 1 serving for most foods in these groups; it is about the size of a typical granola bar, three-quarters to 2 cups of cereal, 10 to 12 crackers, and 15 to 25 chips. We determined the GL for each product by multiplying the number of available carbohydrates (total carbohydrate – dietary fiber) by the product’s glycemic index/100. In general, GL is categorized as low (≤ 10), medium (11-19), or high (≥ 20).

We applied the Altman Rule to categorize each product as meeting or not meeting the rule. We compared the proportion of foods meeting the Altman Rule, stratified by GL and by specific foods, and used chi-square to determine if differences were statistically significant. These data were collected and analyzed in the summer of 2019.

RESULTS

There were 1235 foods (342 breakfast cereals, 305 chips, 379 crackers, and 209 granola bars) used for this analysis. There is a significant relationship between the GL of foods and the Altman Rule in that most low-GL (68%), almost half of medium-GL (48%), and only a few high-GL foods (7%) met the rule (P < .001) (TABLE 1). There was also a significant relationship between “meeting the Altman Rule” and GL within each food type (P < .001) (TABLE 2).

The medium-GL foods were the second largest category of foods we calculated; thus we further broke them into binary categories of

Foods that met the rule were more likely to be low GL and foods that did not pass the rule were more likely high GL. Within the medium-GL category, foods that met the rule were more likely to be low-medium GL.

Continue to: The findings within food categories...

The findings within food categories showed that very few cereals, chips, crackers, and granola bars were low GL. For every food category, except granola bars, far more low-GL foods met the Altman Rule than those that did not. At the same time, very few high-GL foods met the Altman Rule. The category with the most individual high-GL food items meeting the Altman Rule was cereal. This was also the subcategory with the largest percentage of high-GL food items meeting the Altman Rule. Thirty-nine cereals that were high GL met the rule, but more than 4 times as many high-GL cereals did not (n = 190).

DISCUSSION

Marketing and nutrition messaging create consumer confusion that makes it challenging to identify packaged food items that are more nutrient dense. The Altman Rule simplifies food choices that have become unnecessarily complex. Our findings suggest this 2-step rule is a reasonable proxy for the more complicated and less accessible GL for packaged carbohydrates, such as cereals, chips, crackers, and snack bars. Foods that meet the rule are likely low or low-medium GL and thus are foods that are likely to be healthier choices.

Of note, only 9% of chips (n = 27) passed the Altman Rule, likely due to their low dietary fiber content, which was typical of chips. If a food item does not have at least 3 grams of total dietary fiber per serving, it does not pass the Altman Rule, regardless of how much protein or sugar is in the product. This may be considered a strength or a weakness of the Altman Rule. Few nutrition-dense foods are low in fiber, but some foods could be nutritious but do not meet the Altman Rule due to having < 3 g of fiber.

With the high prevalence of chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease, it is essential to help consumers prevent chronic disease altogether or manage their chronic disease by providing tools to identify healthier food choices. The tool also has a place in clinical medicine for use by physicians and other health care professionals. Research shows that physicians find both time and lack of knowledge/resources to be a barrier to providing nutritional counseling to patients.10 Since the Altman Rule can be shared and explained with very little time and without extensive nutritional knowledge, it meets these needs.

Limitations

Glycemic load. We acknowledge that the Altman Rule is not foolproof and that assessing this rule based on GL has some limitations. GL is not a perfect or comprehensive way to measure the nutritional value of a food. For example, fruits such as watermelon and grapes are nutritionally dense. However, they contain high amounts of natural sugars—and as such, their GL is relatively high, which could lead a consumer to perceive them as unhealthy. Nevertheless, GL is both a useful and accepted tool and a reasonable way to assess the validity of the rule, specifically when assessing packaged carbohydrates. The simplicity of the Altman Rule and its relationship with GL makes it such that consumers are more likely to make a healthier food choice using it.9

Continue to: Specificity and sensitivity

Specificity and sensitivity. There are other limitations to the Altman Rule, given that a small number of high-GL foods meet the rule. For example, some granola bars had high dietary protein, which offset a high sugar content just enough to pass the rule despite a higher GL. As such, concluding that a snack bar is a healthier choice because it meets the Altman Rule when it has high amounts of sugar may not be appropriate. This limitation could be considered a lack of specificity (the rule includes food it ought not to include). Another limitation to consider would be a lack of sensitivity, given that only 68% of low-GL foods passed the Altman Rule. Since GL is associated with carbohydrate content, foods with a low carbohydrate count often have little to no fiber and thus would fall into the category of foods that did not meet the Altman Rule but had low GL. In this case, however, the low amount of fiber may render the Altman Rule a better indicator of a healthier food choice than the GL.

Hidden sugars. Foods with sugar alcohols and artificial sweeteners may be as deleterious as caloric alternatives while not being accounted for when reporting the grams of sugar per serving on the nutrition label.7 This may represent an exception to the Altman Rule, as foods that are not healthier choices may pass the rule because the sugar content on the nutrition label is, in a sense, artificially lowered. Future research may investigate the hypothesis that these foods are nutritionally inferior despite meeting the Altman Rule.

The sample. Our study also was limited to working only with foods that were included in the NDSR database up to 2010. This limitation is mitigated by the fact that the sample size was large (> 1000 packaged food items were included in our analyses). The study also could be limited by the food categories that were analyzed; food categories such as bread, rice, pasta, and bagels were not included.

The objective of this research was to investigate the relationship between GL and the Altman Rule, rather than to conduct an exhaustive analysis of the Altman Rule for every possible food category. Studying the relationship between the Altman Rule and GL in other categories of food is an objective for future research. The data so far support a relationship between these entities. The likelihood of the nutrition facts of foods changing without the GL changing (or vice versa) is very low. As such, the Altman Rule still seems to be a reasonable proxy of GL.

CONCLUSIONS

Research indicates that point-of-sale tools, such as Guiding Stars, NuVal, and other stoplight tools, can successfully alter consumers’ behaviors.9 These tools can be helpful but are not available in many supermarkets. Despite the limitations, the Altman Rule is a useful decision aid that is accessible to all consumers no matter where they live or shop and is easy to use and remember.

The Altman rule can be used in clinical practice by health care professionals, such as physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, dietitians, and health coaches. It also has the potential to be used in commercial settings, such as grocery stores, to help consumers easily identify healthier convenience foods. This has public health implications, as the rule can both empower consumers and potentially incentivize food manufacturers to upgrade their products nutritionally.

Additional research would be useful to evaluate consumers’ preferences and perceptions about how user-friendly the Altman Rule is at the point of sale with packaged carbohydrate foods. This would help to further understand how the use of information on food packaging can motivate healthier decisions—thereby helping to alleviate the burden of chronic disease.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kimberly R. Dong, DrPH, MS, RDN, Tufts University School of Medicine, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, 136 Harrison Avenue, MV Building, Boston, MA 02111; kimberly.dong@tufts.edu

1. Hersey JC, Wohlgenant KC, Arsenault JE, et al. Effects of front-of-package and shelf nutrition labeling systems on consumers. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:1-14. doi: 10.1111/nure.12000

2. Jenkins DJA, Dehghan M, Mente A, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and cardiovascular disease and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1312-1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007123

3. Brand-Miller J, Hayne S, Petocz P, et al. Low–glycemic index diets in the management of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2261-2267. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2261

4. Matthan NR, Ausman LM, Meng H, et al. Estimating the reliability of glycemic index values and potential sources of methodological and biological variability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:1004-1013. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.137208

5. Sonnenberg L, Gelsomin E, Levy DE, et al. A traffic light food labeling intervention increases consumer awareness of health and healthy choices at the point-of-purchase. Prev Med. 2013;57:253-257. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.07.001

6. Savoie N, Barlow K, Harvey KL, et al. Consumer perceptions of front-of-package labelling systems and healthiness of foods. Can J Public Health. 2013;104:e359-e363. doi: 10.17269/cjph.104.4027

7. Fischer LM, Sutherland LA, Kaley LA, et al. Development and implementation of the Guiding Stars nutrition guidance program. Am J Health Promot. 2011;26:e55-e63. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.100709-QUAL-238

8. Maubach N, Hoek J, Mather D. Interpretive front-of-pack nutrition labels. Comparing competing recommendations. Appetite. 2014;82:67-77. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.07.006

9. Chan J, McMahon E, Brimblecombe J. Point‐of‐sale nutrition information interventions in food retail stores to promote healthier food purchase and intake: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2021;22. doi: 10.1111/obr.13311

10. Mathioudakis N, Bashura H, Boyér L, et al. Development, implementation, and evaluation of a physician-targeted inpatient glycemic management curriculum. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:238212051986134. doi: 10.1177/2382120519861342

1. Hersey JC, Wohlgenant KC, Arsenault JE, et al. Effects of front-of-package and shelf nutrition labeling systems on consumers. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:1-14. doi: 10.1111/nure.12000

2. Jenkins DJA, Dehghan M, Mente A, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and cardiovascular disease and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1312-1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007123

3. Brand-Miller J, Hayne S, Petocz P, et al. Low–glycemic index diets in the management of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2261-2267. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2261

4. Matthan NR, Ausman LM, Meng H, et al. Estimating the reliability of glycemic index values and potential sources of methodological and biological variability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:1004-1013. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.137208

5. Sonnenberg L, Gelsomin E, Levy DE, et al. A traffic light food labeling intervention increases consumer awareness of health and healthy choices at the point-of-purchase. Prev Med. 2013;57:253-257. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.07.001

6. Savoie N, Barlow K, Harvey KL, et al. Consumer perceptions of front-of-package labelling systems and healthiness of foods. Can J Public Health. 2013;104:e359-e363. doi: 10.17269/cjph.104.4027

7. Fischer LM, Sutherland LA, Kaley LA, et al. Development and implementation of the Guiding Stars nutrition guidance program. Am J Health Promot. 2011;26:e55-e63. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.100709-QUAL-238

8. Maubach N, Hoek J, Mather D. Interpretive front-of-pack nutrition labels. Comparing competing recommendations. Appetite. 2014;82:67-77. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.07.006

9. Chan J, McMahon E, Brimblecombe J. Point‐of‐sale nutrition information interventions in food retail stores to promote healthier food purchase and intake: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2021;22. doi: 10.1111/obr.13311

10. Mathioudakis N, Bashura H, Boyér L, et al. Development, implementation, and evaluation of a physician-targeted inpatient glycemic management curriculum. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:238212051986134. doi: 10.1177/2382120519861342