User login

CASE 1 Defining anatomic structures to assure surgical precision

A 44-year-old woman is scheduled for a vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. In your academic practice, a resident routinely operates with you and is accompanied by a medical student. As this is your first case with each learner, you review the steps of the procedure along with pertinent anatomy. During this discussion, numerous anatomic terms are used to describe anterior cul-de-sac entry, including pubocervical fascia, vesicouterine fold, and vesicovaginal space. Which of these terms, if any, are correct? Is there a preferred term that should be used to teach future learners so we can all “speak” the same language?

What’s in a name?

ObGyns must thoroughly understand pelvic anatomy, since much of our patient care relates to structures in that region. We also must understand the terminology that most appropriately describes each pelvic structure so that we can communicate effectively with colleagues and other providers. The case described above lists several terms that are commonly found in gynecologic textbooks and surgical atlases to describe dissection for vaginal hysterectomy. Lack of a standardized vocabulary, however, often confuses teachers and learners alike, and it highlights the importance of having a universal language to ensure the safe, effective performance of surgical procedures.1

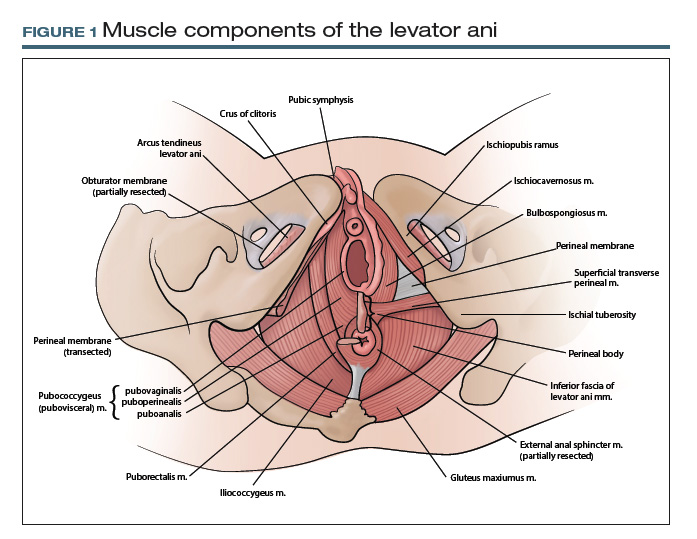

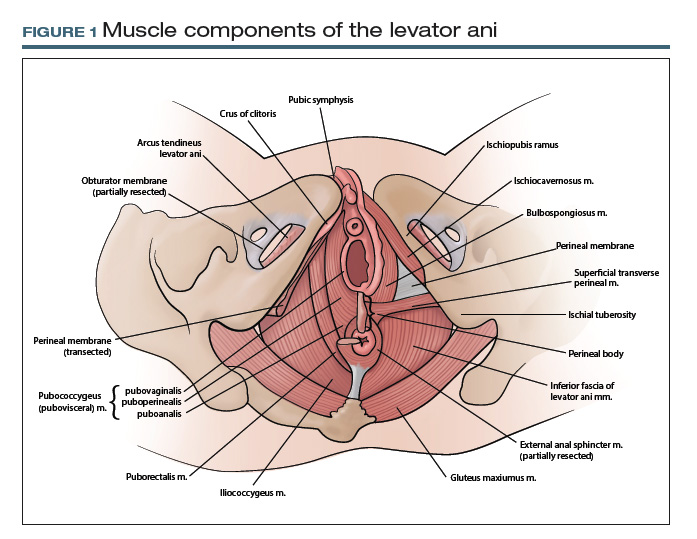

At first glance, it may seem that anatomic terms are inherently descriptive of the structure they represent; for example, the terms uterus and vagina seem rather obvious. However, many anatomic terms convey ambiguity. Which muscles, for example, constitute the levator ani: pubococcygeus, pubovisceral, pubovisceralis, puboperinealis, puboanalis, pubovaginalis, puborectalis, puborectal, iliococcygeus, ischiococcygeus? Do any of these terms redundantly describe the same structure, or does each term refer to an independent structure?

Standard terminology is essential

Anatomists long have recognized the need for standardized terminology to facilitate clear communication. To provide historical background, the term anatomy is derived from the Greek word for “dissection” or “to cut open.”2 Records on the scientific study of human anatomy date back thousands of years.

A brief review of current standardized terminology can be traced back to 1895, with the publication of Basle Terminologia Anatomica.3 That work was intended to provide a consolidated reference with clear direction regarding which anatomic terms should be used. It was updated several times during the ensuing century and was later published as Nomina Anatomica.

In 1990, an international committee was formed with representatives from many anatomical organizations, again with the intention of providing standardized anatomic terminology. Those efforts resulted in the publication of Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology, commonly referred to as TA, in 1998. TA continues to be the referent standard for human anatomic terminology; it was most recently updated in 2011.4

CASE 2 Conveying details of mesh erosion

A 52-year-old woman presents to the general gynecology clinic with a 10-year history of pelvic pain and dyspareunia after undergoing vaginal mesh surgery for prolapse and urinary incontinence. On examination, there is a visible ridge of mesh extending from the left side of the midurethra along the anterior and lateral vagina for a length of 1.5 cm. There also is a palpable tight band on the right vaginal wall near the ischial spine that reproduces her pain and causes spasm of the levator ani. You believe the patient needs a urogynecology referral for complications of vaginal mesh. How do you best describe your findings to your urogynecology colleague?

Continue to: Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective...

Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) recognized the importance of standardizing terminology specific to the pelvis. The SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group thus was organized in 2016. The Pelvic Anatomy Group’s purpose is to help educate physicians about pelvic anatomy, with the overarching goal of compiling instructional materials, primarily from dissections (surgical or cadaveric), and radiologic imaging for all pelvic structures. Throughout the discussions on this initiative, it became clear that standardized terms needed to be established and used for pelvic structures.

While TA is an excellent reference work, it does not include all of the clinically relevant structures for gynecologic surgeons. As physicians, surgeons, and women’s health care providers, we read about and discuss pelvic anatomy structures in medical textbooks, medical literature, and clinical settings that are not necessarily included in TA. In addition, advances in information technology have facilitated the creation of clinically oriented computer-based anatomy programs and expanded the number and availability of electronic publications on surgical and clinical anatomy.5 As a result, there is a need not only to standardize nomenclature but also to continually revise and update terminology and integrate new terms, both from an anatomic and a clinical perspective.

The Pelvic Anatomy Group developed a novel approach to anatomic terminology. We decided to review the medical literature, identify the terms used, adjudicate the terms with current TA terms, and provide consensus for the terms and structures in the pelvis. Because of the volume of literature available and the existing number of terms, we divided the pelvis into 4 regions—anterior, apical, posterior, and vulvar—to improve the feasibility of reviewing the medical literature for the entire female pelvis.

Our process for tackling terminology

Our literature review started with the anterior compartment. (For complete details, see our prior publication.3) Modeled on a systematic review, we searched the MEDLINE database for terms related to the anterior pelvis, screened all associated abstracts, and then extracted terms from appropriate papers. We also identified several book chapters from various disciplines (anatomy, gynecology, urology, and radiology) to ensure wide representation of disciplines. We then extracted all terms pertinent to the anterior pelvis.

We organized the terms, with terms that referred to the same anatomic structure grouped together. Whenever possible, we used TA terms as the preferred terms. In this process, however, we identified several clinically relevant terms that were not included in TA: pelvic sidewall, pelvic bones, anterior compartment, pubourethral ligament, vaginal sulcus, and levator hiatus, among others. The new terms were then proposed and agreed on by members of the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group and accepted by SGS members. We currently are completing a similar process for the apical pelvis, posterior pelvis, and vulvar regions.

TA code numbers pinpoint the nomenclature

As we move forward, we suggest that physicians use TA or other approved terms for patient and research communication. Such use will help standardize anatomic terms and also will improve communication between providers and education for learners.

Continue to: TA includes approved options...

TA includes approved options in English and Latin and lists a unique identification number for each term (shown in parentheses in the examples that follow). For instance, to answer the question posed earlier, the levator ani (A04.5.04.002) is comprised of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), puborectalis (A04.5.04.007), and iliococcygeus (A04.5.04.008) muscles (FIGURE 1).The terms pubovisceral and pubovisceralis are used synonymously in the literature with pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003).3 The additional terms puboperinealis (A04.5.04.004), pubovaginalis (A04.5.04.005), and puboanalis (A04.5.04.006) are subcomponents of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), and this relationship is indicated in TA by indentation formatting.4 Finally, the ischiococcygeus (A04.5.04.011) muscle is not considered part of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).

Revisiting the mesh erosion case: Reporting your findings

After reviewing the recommended terminology for the anterior pelvis,3,4 you might draft a report as follows: “A mesh erosion was visualized in anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006) at the level of the mid-urethra extending into ‘anterior and lateral vaginal sulci’ (proposed term). In addition, there is a painful tight band in the ‘lateral vaginal wall’ (proposed term) near the ischial spine (A02.5.01.205). Palpation of this band reproduces the patient’s pain and causes secondary spasm of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).” Certainly, TA identification numbers would not be expected to be included in medical communication; they are included here for reference.

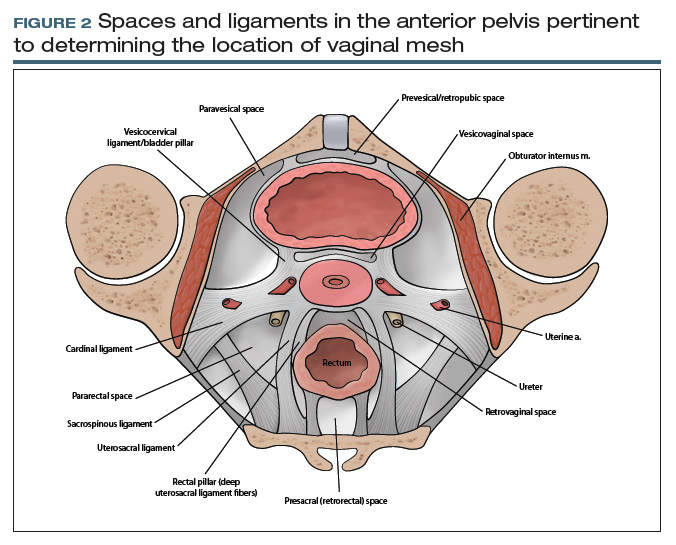

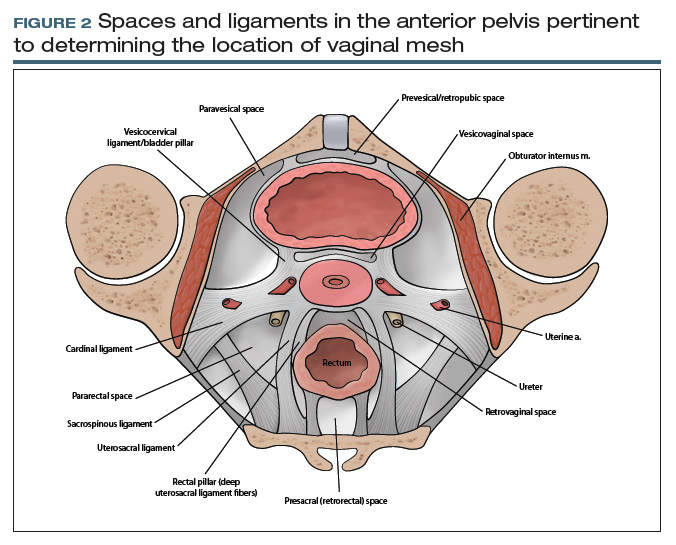

From your description, your urogynecology colleague has a better understanding of the location of your patient’s vaginal mesh and requests her operative report from an outside facility. In the operative report, the surgeon described “placement of mesh into the vagina, dissection through the rectal spaces, and anchoring of the mesh into the levator/pelvic muscles, the cervix, and lastly to the paraurethral ligaments,” and “passage of trocars through the cave of Retzius at the level of the midurethra” (FIGURE 2).

Based on this description, the urogynecologist ascertains that the mesh is located in the anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006), with passage of anchoring arms through the bilateral sacrospinous ligaments (A03.6.03.007) and retropubic space (A10.1.01.003). Exposed mesh is visible, extending from the midurethra to the “anterior and lateral vaginal sulci” (proposed term).

This case clearly demonstrates the importance of communication between providers for patient care, since understanding the patient’s anatomy and the location of the vaginal mesh is important for planning surgical excision of the exposed mesh.

Additional initiatives

Outlining standardized terminology is just the first step toward improving the anatomic “language” used among providers. Ongoing efforts from the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group include a special imaging group’s review of imaging modalities (ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomography) to improve standardization on reporting clinical anatomy. In addition, SGS has developed a group to create educational content related to the structures identified by the terminology group from cadaveric or surgical dissections. Educational materials will be compiled to help physicians and learners expand their anatomic understanding and improve their communication.

Further details of the Pelvic Anatomy Group’s efforts can be found on the SGS website at https://www.sgsonline.org.

- American Association of Clinical Anatomists, Educational Affairs Committee. The clinical anatomy of several invasive procedures. Clin Anat. 1999;12:43-54.

- Venes D, ed. Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Company; 2017.

- Jeppson PC, Balgobin S, Washington BB, et al; for the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Pelvic Anatomy Group. Recommended standardized terminology of the anterior female pelvis based on a structured medical literature review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:26-39.

- Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminologies (FCAT). Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 2011.

- Rosse C. Terminologia Anatomica: considered from the perspective of next-generation knowledge sources. Clin Anat. 2001;14:120-133.

CASE 1 Defining anatomic structures to assure surgical precision

A 44-year-old woman is scheduled for a vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. In your academic practice, a resident routinely operates with you and is accompanied by a medical student. As this is your first case with each learner, you review the steps of the procedure along with pertinent anatomy. During this discussion, numerous anatomic terms are used to describe anterior cul-de-sac entry, including pubocervical fascia, vesicouterine fold, and vesicovaginal space. Which of these terms, if any, are correct? Is there a preferred term that should be used to teach future learners so we can all “speak” the same language?

What’s in a name?

ObGyns must thoroughly understand pelvic anatomy, since much of our patient care relates to structures in that region. We also must understand the terminology that most appropriately describes each pelvic structure so that we can communicate effectively with colleagues and other providers. The case described above lists several terms that are commonly found in gynecologic textbooks and surgical atlases to describe dissection for vaginal hysterectomy. Lack of a standardized vocabulary, however, often confuses teachers and learners alike, and it highlights the importance of having a universal language to ensure the safe, effective performance of surgical procedures.1

At first glance, it may seem that anatomic terms are inherently descriptive of the structure they represent; for example, the terms uterus and vagina seem rather obvious. However, many anatomic terms convey ambiguity. Which muscles, for example, constitute the levator ani: pubococcygeus, pubovisceral, pubovisceralis, puboperinealis, puboanalis, pubovaginalis, puborectalis, puborectal, iliococcygeus, ischiococcygeus? Do any of these terms redundantly describe the same structure, or does each term refer to an independent structure?

Standard terminology is essential

Anatomists long have recognized the need for standardized terminology to facilitate clear communication. To provide historical background, the term anatomy is derived from the Greek word for “dissection” or “to cut open.”2 Records on the scientific study of human anatomy date back thousands of years.

A brief review of current standardized terminology can be traced back to 1895, with the publication of Basle Terminologia Anatomica.3 That work was intended to provide a consolidated reference with clear direction regarding which anatomic terms should be used. It was updated several times during the ensuing century and was later published as Nomina Anatomica.

In 1990, an international committee was formed with representatives from many anatomical organizations, again with the intention of providing standardized anatomic terminology. Those efforts resulted in the publication of Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology, commonly referred to as TA, in 1998. TA continues to be the referent standard for human anatomic terminology; it was most recently updated in 2011.4

CASE 2 Conveying details of mesh erosion

A 52-year-old woman presents to the general gynecology clinic with a 10-year history of pelvic pain and dyspareunia after undergoing vaginal mesh surgery for prolapse and urinary incontinence. On examination, there is a visible ridge of mesh extending from the left side of the midurethra along the anterior and lateral vagina for a length of 1.5 cm. There also is a palpable tight band on the right vaginal wall near the ischial spine that reproduces her pain and causes spasm of the levator ani. You believe the patient needs a urogynecology referral for complications of vaginal mesh. How do you best describe your findings to your urogynecology colleague?

Continue to: Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective...

Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) recognized the importance of standardizing terminology specific to the pelvis. The SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group thus was organized in 2016. The Pelvic Anatomy Group’s purpose is to help educate physicians about pelvic anatomy, with the overarching goal of compiling instructional materials, primarily from dissections (surgical or cadaveric), and radiologic imaging for all pelvic structures. Throughout the discussions on this initiative, it became clear that standardized terms needed to be established and used for pelvic structures.

While TA is an excellent reference work, it does not include all of the clinically relevant structures for gynecologic surgeons. As physicians, surgeons, and women’s health care providers, we read about and discuss pelvic anatomy structures in medical textbooks, medical literature, and clinical settings that are not necessarily included in TA. In addition, advances in information technology have facilitated the creation of clinically oriented computer-based anatomy programs and expanded the number and availability of electronic publications on surgical and clinical anatomy.5 As a result, there is a need not only to standardize nomenclature but also to continually revise and update terminology and integrate new terms, both from an anatomic and a clinical perspective.

The Pelvic Anatomy Group developed a novel approach to anatomic terminology. We decided to review the medical literature, identify the terms used, adjudicate the terms with current TA terms, and provide consensus for the terms and structures in the pelvis. Because of the volume of literature available and the existing number of terms, we divided the pelvis into 4 regions—anterior, apical, posterior, and vulvar—to improve the feasibility of reviewing the medical literature for the entire female pelvis.

Our process for tackling terminology

Our literature review started with the anterior compartment. (For complete details, see our prior publication.3) Modeled on a systematic review, we searched the MEDLINE database for terms related to the anterior pelvis, screened all associated abstracts, and then extracted terms from appropriate papers. We also identified several book chapters from various disciplines (anatomy, gynecology, urology, and radiology) to ensure wide representation of disciplines. We then extracted all terms pertinent to the anterior pelvis.

We organized the terms, with terms that referred to the same anatomic structure grouped together. Whenever possible, we used TA terms as the preferred terms. In this process, however, we identified several clinically relevant terms that were not included in TA: pelvic sidewall, pelvic bones, anterior compartment, pubourethral ligament, vaginal sulcus, and levator hiatus, among others. The new terms were then proposed and agreed on by members of the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group and accepted by SGS members. We currently are completing a similar process for the apical pelvis, posterior pelvis, and vulvar regions.

TA code numbers pinpoint the nomenclature

As we move forward, we suggest that physicians use TA or other approved terms for patient and research communication. Such use will help standardize anatomic terms and also will improve communication between providers and education for learners.

Continue to: TA includes approved options...

TA includes approved options in English and Latin and lists a unique identification number for each term (shown in parentheses in the examples that follow). For instance, to answer the question posed earlier, the levator ani (A04.5.04.002) is comprised of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), puborectalis (A04.5.04.007), and iliococcygeus (A04.5.04.008) muscles (FIGURE 1).The terms pubovisceral and pubovisceralis are used synonymously in the literature with pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003).3 The additional terms puboperinealis (A04.5.04.004), pubovaginalis (A04.5.04.005), and puboanalis (A04.5.04.006) are subcomponents of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), and this relationship is indicated in TA by indentation formatting.4 Finally, the ischiococcygeus (A04.5.04.011) muscle is not considered part of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).

Revisiting the mesh erosion case: Reporting your findings

After reviewing the recommended terminology for the anterior pelvis,3,4 you might draft a report as follows: “A mesh erosion was visualized in anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006) at the level of the mid-urethra extending into ‘anterior and lateral vaginal sulci’ (proposed term). In addition, there is a painful tight band in the ‘lateral vaginal wall’ (proposed term) near the ischial spine (A02.5.01.205). Palpation of this band reproduces the patient’s pain and causes secondary spasm of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).” Certainly, TA identification numbers would not be expected to be included in medical communication; they are included here for reference.

From your description, your urogynecology colleague has a better understanding of the location of your patient’s vaginal mesh and requests her operative report from an outside facility. In the operative report, the surgeon described “placement of mesh into the vagina, dissection through the rectal spaces, and anchoring of the mesh into the levator/pelvic muscles, the cervix, and lastly to the paraurethral ligaments,” and “passage of trocars through the cave of Retzius at the level of the midurethra” (FIGURE 2).

Based on this description, the urogynecologist ascertains that the mesh is located in the anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006), with passage of anchoring arms through the bilateral sacrospinous ligaments (A03.6.03.007) and retropubic space (A10.1.01.003). Exposed mesh is visible, extending from the midurethra to the “anterior and lateral vaginal sulci” (proposed term).

This case clearly demonstrates the importance of communication between providers for patient care, since understanding the patient’s anatomy and the location of the vaginal mesh is important for planning surgical excision of the exposed mesh.

Additional initiatives

Outlining standardized terminology is just the first step toward improving the anatomic “language” used among providers. Ongoing efforts from the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group include a special imaging group’s review of imaging modalities (ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomography) to improve standardization on reporting clinical anatomy. In addition, SGS has developed a group to create educational content related to the structures identified by the terminology group from cadaveric or surgical dissections. Educational materials will be compiled to help physicians and learners expand their anatomic understanding and improve their communication.

Further details of the Pelvic Anatomy Group’s efforts can be found on the SGS website at https://www.sgsonline.org.

CASE 1 Defining anatomic structures to assure surgical precision

A 44-year-old woman is scheduled for a vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. In your academic practice, a resident routinely operates with you and is accompanied by a medical student. As this is your first case with each learner, you review the steps of the procedure along with pertinent anatomy. During this discussion, numerous anatomic terms are used to describe anterior cul-de-sac entry, including pubocervical fascia, vesicouterine fold, and vesicovaginal space. Which of these terms, if any, are correct? Is there a preferred term that should be used to teach future learners so we can all “speak” the same language?

What’s in a name?

ObGyns must thoroughly understand pelvic anatomy, since much of our patient care relates to structures in that region. We also must understand the terminology that most appropriately describes each pelvic structure so that we can communicate effectively with colleagues and other providers. The case described above lists several terms that are commonly found in gynecologic textbooks and surgical atlases to describe dissection for vaginal hysterectomy. Lack of a standardized vocabulary, however, often confuses teachers and learners alike, and it highlights the importance of having a universal language to ensure the safe, effective performance of surgical procedures.1

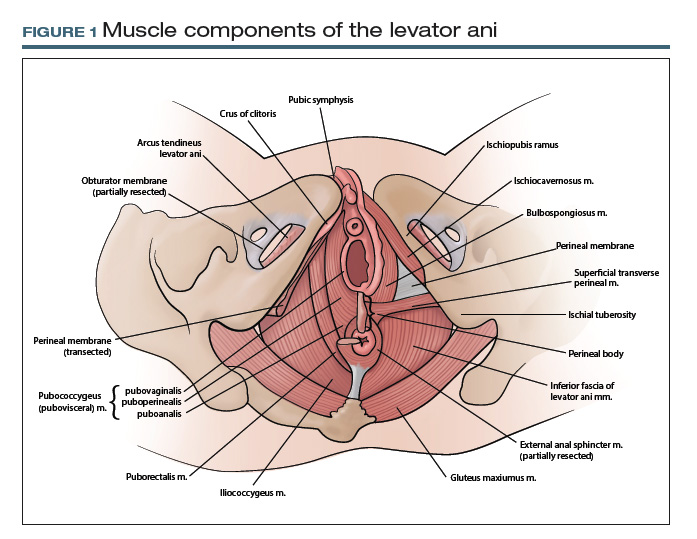

At first glance, it may seem that anatomic terms are inherently descriptive of the structure they represent; for example, the terms uterus and vagina seem rather obvious. However, many anatomic terms convey ambiguity. Which muscles, for example, constitute the levator ani: pubococcygeus, pubovisceral, pubovisceralis, puboperinealis, puboanalis, pubovaginalis, puborectalis, puborectal, iliococcygeus, ischiococcygeus? Do any of these terms redundantly describe the same structure, or does each term refer to an independent structure?

Standard terminology is essential

Anatomists long have recognized the need for standardized terminology to facilitate clear communication. To provide historical background, the term anatomy is derived from the Greek word for “dissection” or “to cut open.”2 Records on the scientific study of human anatomy date back thousands of years.

A brief review of current standardized terminology can be traced back to 1895, with the publication of Basle Terminologia Anatomica.3 That work was intended to provide a consolidated reference with clear direction regarding which anatomic terms should be used. It was updated several times during the ensuing century and was later published as Nomina Anatomica.

In 1990, an international committee was formed with representatives from many anatomical organizations, again with the intention of providing standardized anatomic terminology. Those efforts resulted in the publication of Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology, commonly referred to as TA, in 1998. TA continues to be the referent standard for human anatomic terminology; it was most recently updated in 2011.4

CASE 2 Conveying details of mesh erosion

A 52-year-old woman presents to the general gynecology clinic with a 10-year history of pelvic pain and dyspareunia after undergoing vaginal mesh surgery for prolapse and urinary incontinence. On examination, there is a visible ridge of mesh extending from the left side of the midurethra along the anterior and lateral vagina for a length of 1.5 cm. There also is a palpable tight band on the right vaginal wall near the ischial spine that reproduces her pain and causes spasm of the levator ani. You believe the patient needs a urogynecology referral for complications of vaginal mesh. How do you best describe your findings to your urogynecology colleague?

Continue to: Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective...

Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) recognized the importance of standardizing terminology specific to the pelvis. The SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group thus was organized in 2016. The Pelvic Anatomy Group’s purpose is to help educate physicians about pelvic anatomy, with the overarching goal of compiling instructional materials, primarily from dissections (surgical or cadaveric), and radiologic imaging for all pelvic structures. Throughout the discussions on this initiative, it became clear that standardized terms needed to be established and used for pelvic structures.

While TA is an excellent reference work, it does not include all of the clinically relevant structures for gynecologic surgeons. As physicians, surgeons, and women’s health care providers, we read about and discuss pelvic anatomy structures in medical textbooks, medical literature, and clinical settings that are not necessarily included in TA. In addition, advances in information technology have facilitated the creation of clinically oriented computer-based anatomy programs and expanded the number and availability of electronic publications on surgical and clinical anatomy.5 As a result, there is a need not only to standardize nomenclature but also to continually revise and update terminology and integrate new terms, both from an anatomic and a clinical perspective.

The Pelvic Anatomy Group developed a novel approach to anatomic terminology. We decided to review the medical literature, identify the terms used, adjudicate the terms with current TA terms, and provide consensus for the terms and structures in the pelvis. Because of the volume of literature available and the existing number of terms, we divided the pelvis into 4 regions—anterior, apical, posterior, and vulvar—to improve the feasibility of reviewing the medical literature for the entire female pelvis.

Our process for tackling terminology

Our literature review started with the anterior compartment. (For complete details, see our prior publication.3) Modeled on a systematic review, we searched the MEDLINE database for terms related to the anterior pelvis, screened all associated abstracts, and then extracted terms from appropriate papers. We also identified several book chapters from various disciplines (anatomy, gynecology, urology, and radiology) to ensure wide representation of disciplines. We then extracted all terms pertinent to the anterior pelvis.

We organized the terms, with terms that referred to the same anatomic structure grouped together. Whenever possible, we used TA terms as the preferred terms. In this process, however, we identified several clinically relevant terms that were not included in TA: pelvic sidewall, pelvic bones, anterior compartment, pubourethral ligament, vaginal sulcus, and levator hiatus, among others. The new terms were then proposed and agreed on by members of the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group and accepted by SGS members. We currently are completing a similar process for the apical pelvis, posterior pelvis, and vulvar regions.

TA code numbers pinpoint the nomenclature

As we move forward, we suggest that physicians use TA or other approved terms for patient and research communication. Such use will help standardize anatomic terms and also will improve communication between providers and education for learners.

Continue to: TA includes approved options...

TA includes approved options in English and Latin and lists a unique identification number for each term (shown in parentheses in the examples that follow). For instance, to answer the question posed earlier, the levator ani (A04.5.04.002) is comprised of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), puborectalis (A04.5.04.007), and iliococcygeus (A04.5.04.008) muscles (FIGURE 1).The terms pubovisceral and pubovisceralis are used synonymously in the literature with pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003).3 The additional terms puboperinealis (A04.5.04.004), pubovaginalis (A04.5.04.005), and puboanalis (A04.5.04.006) are subcomponents of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), and this relationship is indicated in TA by indentation formatting.4 Finally, the ischiococcygeus (A04.5.04.011) muscle is not considered part of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).

Revisiting the mesh erosion case: Reporting your findings

After reviewing the recommended terminology for the anterior pelvis,3,4 you might draft a report as follows: “A mesh erosion was visualized in anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006) at the level of the mid-urethra extending into ‘anterior and lateral vaginal sulci’ (proposed term). In addition, there is a painful tight band in the ‘lateral vaginal wall’ (proposed term) near the ischial spine (A02.5.01.205). Palpation of this band reproduces the patient’s pain and causes secondary spasm of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).” Certainly, TA identification numbers would not be expected to be included in medical communication; they are included here for reference.

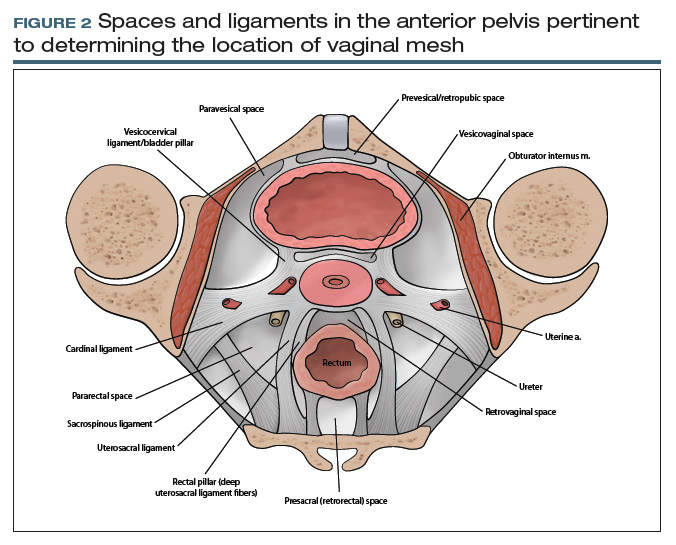

From your description, your urogynecology colleague has a better understanding of the location of your patient’s vaginal mesh and requests her operative report from an outside facility. In the operative report, the surgeon described “placement of mesh into the vagina, dissection through the rectal spaces, and anchoring of the mesh into the levator/pelvic muscles, the cervix, and lastly to the paraurethral ligaments,” and “passage of trocars through the cave of Retzius at the level of the midurethra” (FIGURE 2).

Based on this description, the urogynecologist ascertains that the mesh is located in the anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006), with passage of anchoring arms through the bilateral sacrospinous ligaments (A03.6.03.007) and retropubic space (A10.1.01.003). Exposed mesh is visible, extending from the midurethra to the “anterior and lateral vaginal sulci” (proposed term).

This case clearly demonstrates the importance of communication between providers for patient care, since understanding the patient’s anatomy and the location of the vaginal mesh is important for planning surgical excision of the exposed mesh.

Additional initiatives

Outlining standardized terminology is just the first step toward improving the anatomic “language” used among providers. Ongoing efforts from the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group include a special imaging group’s review of imaging modalities (ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomography) to improve standardization on reporting clinical anatomy. In addition, SGS has developed a group to create educational content related to the structures identified by the terminology group from cadaveric or surgical dissections. Educational materials will be compiled to help physicians and learners expand their anatomic understanding and improve their communication.

Further details of the Pelvic Anatomy Group’s efforts can be found on the SGS website at https://www.sgsonline.org.

- American Association of Clinical Anatomists, Educational Affairs Committee. The clinical anatomy of several invasive procedures. Clin Anat. 1999;12:43-54.

- Venes D, ed. Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Company; 2017.

- Jeppson PC, Balgobin S, Washington BB, et al; for the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Pelvic Anatomy Group. Recommended standardized terminology of the anterior female pelvis based on a structured medical literature review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:26-39.

- Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminologies (FCAT). Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 2011.

- Rosse C. Terminologia Anatomica: considered from the perspective of next-generation knowledge sources. Clin Anat. 2001;14:120-133.

- American Association of Clinical Anatomists, Educational Affairs Committee. The clinical anatomy of several invasive procedures. Clin Anat. 1999;12:43-54.

- Venes D, ed. Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Company; 2017.

- Jeppson PC, Balgobin S, Washington BB, et al; for the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Pelvic Anatomy Group. Recommended standardized terminology of the anterior female pelvis based on a structured medical literature review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:26-39.

- Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminologies (FCAT). Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 2011.

- Rosse C. Terminologia Anatomica: considered from the perspective of next-generation knowledge sources. Clin Anat. 2001;14:120-133.