User login

CASE: Resurgent, worsening dysmenorrhea

A 32-year-old woman (G2P2) with a history of 2 spontaneous vaginal deliveries presents to your office after 10 months of severe, worsening dysmenorrhea. Shortly after she developed severe dysmenorrhea, she began to experience daily pain in her lower abdomen and pelvis. This pain occurred in the midline, bilateral lower quadrants, and rectum. She also developed deep dyspareunia.

She has a history of dysmenorrhea from adolescence but has otherwise been healthy and pain-free until the past 10 months. She has tried oral contraceptives and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, without success. She is happily married, and her medical history is unremarkable except for a bout of Lyme disease 6 months before the onset of pain, at which time she also developed symptoms of fatigue.

A physical examination is remarkable for unilateral thickening and shortening of the left uterosacral ligament, dense scarring, and tenderness at the posterior fornix, with poor uterine mobility. Magnetic resonance imaging reveals findings consistent with the physical examination.

What is causing her pain after such a long phase without it? And what treatments should you offer her?

Endometriosis represents the ectopic presence of endometrial glands and stroma. The most common sites of endometriotic implants are the uterosacral ligaments, cul-de-sac peritoneum, and ovarian fossae. Most clinicians are aware that the location of an endometriosis implant does not predict the location of pain experienced by the patient. An understanding of both abdominal and pelvic neuroanatomy may help clarify this phenomenon, as may knowledge of the concept of viscerosomatic convergence.1–3

Not only does the location of the endometriosis implant fail to predict the location of pain, but the level or stage of disease (in other words, the amount of endometriosis present) does not accurately predict the level of pain.4,5 In fact, some women with histopathologically confirmed endometriosis have no pain whatsoever.

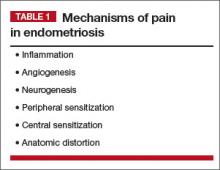

When managing chronic pelvic pain (CPP), we need to consider mechanisms of pain when endometriosis is the primary pain driver, as well as when endometriosis is present but irrelevant to the patient’s pain (TABLE 1).

In this article, I focus on the role of endometriosis in CPP, including the role of the central nervous system (CNS) and other entities that may influence the pain threshold. This discussion is intended to help shift the current paradigm of thought about endometriosis and its association with CPP.

Numerous mechanisms drive pain in endometriosis

There are 2 main anatomic levels at which to consider pain associated with endometriosis—the local level (the endometriosis itself) and the level of the spinal cord and brain. Although emerging evidence points to a significant interaction between local anatomic disease and higher-order neurologically mediated pain,6–8 each level should be considered separately during selection of treatment.

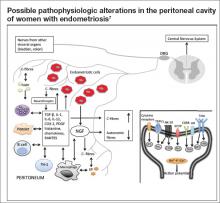

At the most basic level, endometriosis is a disease of inflammation. Although the presence of inflammatory mediators is associated with the presence of endometriosis, the amount of endometriosis does not correlate with the amount of inflammatory mediators. Inflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL) 1, IL-6, IL-8, human monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, RANTES (Regulated on Activation Normal T cell Expressed and Secreted), and tumor necrosis factor alpha are found in significantly higher concentrations in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis, compared with women without endometriosis. The inflammatory mediators are produced by both endometriotic lesions and the surrounding peritoneum (Figure). This set of inflammatory mediators not only leads to angiogenesis and endometriosis tissue maintenance but also to neurogenesis.9 It is from this inflammatory environment that other pathogenic mechanisms can operate.

For example, when dorsal root ganglia are exposed to the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis, as opposed to the peritoneal fluid of women without endometriosis, there is a significant differential in the growth of sensory versus sympathetic neurites.10 This phenomenon translates into increased visceral pain sensitivity. In fact, it is this neurogenesis and increased neuronal responsiveness that are responsible for the upregulation of pain mediated by the spinal cord and brain.

A familiar but imperfectly understood theory is that of central sensitization. When there are prolonged and repeated pain impulses from peripheral sources, the CNS responds anatomically and biochemically by changing the processing of those pain signals. Even after the stimulus (in this case endometriosis) is removed for such high-intensity nociceptive signals, increasing excitability can continue. The result is chronic pain that is unresponsive or poorly responsive to treatment; in some cases, the chronic pain may even mimic the original anatomic site of the pain.

Central sensitization generally involves 2 phases: hyperalgesia, in which the excitatory threshold of the nerve is reset, leading to a lowered stimulatory requirement, and allodynia, in which normally harmless stimuli are interpreted as pain. During the allodynia phase, fibers (eg, C-fibers) that typically carry nonpainful information are recruited to become pain transmitters.

The pain threshold—and why it is important

The concept of the pain threshold is both complex and elusive. It can be defined as the point at which a stimulus begins to be perceived as painful. The pain threshold may be dependent on multiple variables, including gender, genetic issues (a concentration of mu receptors), a history of abuse, socioeconomic status, current and past levels of depression, earlier pain experiences, and psychosocial stressors.

The pain threshold is important because it changes over time. For example, a patient with endometriosis may experience isolated dysmenorrhea as a teen but, over time, may develop a pattern of chronic daily pain and depression. Or a woman with CPP may respond well to initial therapies but worsen after a stressful life event such as death of a loved one or new stressors at work. An understanding of the many variables that can alter the pain threshold can lead to more effective counseling and treatment and help us avoid unnecessary therapies.

Multiple types of pain can coexist in 1 patient

Clinicians who care for women with endometriosis and CPP should have an understanding of the mechanism of their pain, including the differences between nociceptive somatic, nociceptive visceral, and neuropathic pain (TABLE 2). All 3 types of pain can exist in a single patient with CPP.

Nociceptive somatic pain generally originates in somatic structures such as muscle, ligament, bone, and tendons. Women with endometriosis often have somatic pain, for 2 main reasons.11 First, skeletal muscles respond adversely to long-term inflammatory stimuli,12 and endometriosis is primarily a disease of inflammation. Long-term inflammatory stimuli may lead to atrophy and spasm. Second, the presence of inflammation in the muscle likely leads to worsening hyperalgesia with increasing muscle activity.13 This can lead to and explain pain in the pelvic floor, abdominal wall muscles, hips, thighs, buttocks, and lower back. Once this is understood, treatments can be targeted to the underlying mechanisms and specific muscle groups.

Nociceptive visceral pain generally indicates pain originating in visceral structures. In the pelvis, visceral structures of main concern are the uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes, vagina (upper two-thirds), bladder, ureters, sigmoid colon, rectum, and, most importantly related to endometriosis, the visceral peritoneum.

In the case of visceral pain, the likely associated mechanisms are inflammation as well as local nerve growth.14,15 Local inflammation in turn leads to scarring and visceral hyperalgesia.16 Over a long period of time, local visceral hyperalgesia can lead to spinal wind-up and central sensitization. Spinal wind-up is the spinal cord’s expansion of signals from peripheral nociceptors associated with C-fibers. It likely stems from a prolonged, intense, and persistent generation of afferent nociceptive impulses. When this occurs, CNS pathways are well established and sensations of pain can remain even after careful surgery to remove sources of inflammation and anatomic deformity (visceral scarring). For this reason, early radical resection of endometriosis in women with endometriosis-associated pelvic pain may be more likely than later surgery to reduce or eliminate pain. Otherwise, reoperation rates may be high and later surgeries may fail to yield histopathology for endometrial glands and stroma.17

Neuropathic pain generally reflects damage to or dysfunction of either the peripheral nervous system or the CNS. Endometriosis-associated pain is also neuropathic in nature and occurs through multiple mechanisms.

There is good evidence to support the development of abnormal nerve growth in and around areas of endometriosis. When such nerve fibers exist, they serve only a pathologic function. This abnormal nerve growth is induced by multiple molecules, including nerve growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.7 It is likely that once high-density areas of sensitized nerves develop, peripheral nerves also become sensitized by endometriosis-associated inflammatory cytokines.16 When there are abnormal nerve growth and elevated levels of peripheral nerve sensitization, the nerves most often recruited are C-fibers, unmyeli-nated fibers largely associated with both peripheral and central neuropathic pain. When C-fibers are recruited, the ratio of C-fibers to autonomic afferent pain fibers increases.

In endometriosis, persistent inflammatory signals lead to an increase in the excitability of peripheral nerves, thereby significantly increasing transmitted pain signals and likely reducing the body’s ability to suppress pain.

Some of the peripheral nerve changes I have described may be observed via magnetic resonance tractography (MRT), which highlights neuronal tracts over long distances. Fractional anisotropy values measured by MRT yield information about the quality of neuronal structures. In women with endometriosis, fractional anisotropy values in the peripheral nerve roots of S1, S2, and S3 appear to be lower than those in women without endometriosis,18 indicating disruption of the normally myelinated nerve structure.

It’s time to abandon nontargeted treatments

Endometriosis-associated CPP remains a challenging heterogeneous and multifactorial disease state. In the past, treatments such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists have been prescribed without an appropriate consideration of the disease and its mechanism of associated pain. In our CPP specialty practice, we have abandoned such nontargeted approaches. By developing an understanding of central sensitization, local neurologic responses to inflammation, and the pain threshold, clinicians are more likely to select a treatment targeted to specific mechanisms. Such an approach is superior to the traditional “shotgun” approach to treatment, which can produce harmful side effects and have high long-term failure rates. As Stratton and colleagues observed, “traditional methods of classifying endometriosis-associated pain based on disease, duration, and anatomy are inadequate and should be replaced by a mechanism-based evaluation.”19 Future clinical care and research will necessarily focus on specific disease etiologies and pain mechanisms if we are to continue to improve the care of women with CPP.

Case: Resolved

Because the history, physical examination, and imaging are strongly suggestive of endometriosis, the patient is counseled about the treatments most likely to be effective, which include medical therapies such as centrally acting agents (gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants) and local treatments such as placement of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or surgical resection. She elects to undergo total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy and radical resection of endometriosis. Histopathology confirms adenomyosis and deep infiltrating endometriosis, including implants on the rectovaginal septum. The patient remains pain-free at her 2-year follow-up.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Brumovsky PR, Gebhart GF. Visceral organ cross-sensitization—an integrated perspective. Auton Neurosci. 2010;153(1–2):106–115.

2. Schwartz ES, Gebhart GF. Visceral pain. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2014;20:171–197.

3. Gebhart GF. Visceral pain—peripheral sensitization. Gut. 2000;47(suppl 4):54–58.

4. Fukaya T, Hoshiai H, Yajima A. Is pelvic endometriosis always associated with chronic pain? A retrospective study of 618 cases diagnosed by laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(3):719–722.

5. Vercellini P, Trespidi L, De GO, Cortesi I, Parazzini F, Crosignani PG. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: relation to disease stage and localization. Fertil Steril. 1996;65(2):299–304.

6. Brawn J, Morotti M, Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Vincent K. Central changes associated with chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):737–747.

7. Morotti M, Vincent K, Brawn J, Zondervan KT, Becker CM. Peripheral changes in endometriosis-associated pain. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):717–736.

8. Neziri AY, Bersinger NA, Andersen OK, Arendt-Nielsen L, Mueller MD, Curatolo M. Correlation between altered central pain processing and concentration of peritoneal fluid inflammatory cytokines in endometriosis patients with chronic pelvic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39(3):181–184.

9. Asante A, Taylor RN. Endometriosis: the role of neuroangiogenesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:163–182.

10. Arnold J, Barcena de Arellano ML, Ruster C, et al. Imbalance between sympathetic and sensory innervation in peritoneal endometriosis. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(1):132–141.

11. Warren JW, Morozov V, Howard FM. Could chronic pelvic pain be a functional somatic syndrome? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(3):199–205.

12. Korotkova M, Lundberg IE. The skeletal muscle arachidonic acid cascade in health and inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(5):295–303.

13. Sluka KA, Rasmussen LA. Fatiguing exercise enhances hyperalgesia to muscle inflammation. Pain. 2010;148(2):188–197.

14. McKinnon B, Bersinger NA, Wotzkow C, Mueller MD. Endometriosis-associated nerve fibers, peritoneal fluid cytokine concentrations, and pain in endometriotic lesions from different locations. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(2):373–380.

15. Anaf V, El Nakadi I, De Moor V, Chapron C, Pistofidis G, Noel JC. Increased nerve density in deep infiltrating endometriotic nodules. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;71(2):112–117.

16. McKinnon BD, Bertschi D, Bersinger NA, Mueller MD. Inflammation and nerve fiber interaction in endometriotic pain. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(1):1–10.

17. Redwine DB. Conservative laparoscopic excision of endometriosis by sharp dissection: life table analysis of reoperation and persistent or recurrent disease. Fertil Steril. 1991;56(4):628–634.

18. Manganaro L, Porpora MG, Vinci V, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging and tractography to evaluate sacral nerve root abnormalities in endometriosis-related pain: a pilot study. Eur Radiol. 2014;24(1):95–101.

19. Stratton P, Khachikyan I, Sinaii N, Ortiz R, Shah J. Association of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis with signs of sensitization and myofascial pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):719–728.

CASE: Resurgent, worsening dysmenorrhea

A 32-year-old woman (G2P2) with a history of 2 spontaneous vaginal deliveries presents to your office after 10 months of severe, worsening dysmenorrhea. Shortly after she developed severe dysmenorrhea, she began to experience daily pain in her lower abdomen and pelvis. This pain occurred in the midline, bilateral lower quadrants, and rectum. She also developed deep dyspareunia.

She has a history of dysmenorrhea from adolescence but has otherwise been healthy and pain-free until the past 10 months. She has tried oral contraceptives and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, without success. She is happily married, and her medical history is unremarkable except for a bout of Lyme disease 6 months before the onset of pain, at which time she also developed symptoms of fatigue.

A physical examination is remarkable for unilateral thickening and shortening of the left uterosacral ligament, dense scarring, and tenderness at the posterior fornix, with poor uterine mobility. Magnetic resonance imaging reveals findings consistent with the physical examination.

What is causing her pain after such a long phase without it? And what treatments should you offer her?

Endometriosis represents the ectopic presence of endometrial glands and stroma. The most common sites of endometriotic implants are the uterosacral ligaments, cul-de-sac peritoneum, and ovarian fossae. Most clinicians are aware that the location of an endometriosis implant does not predict the location of pain experienced by the patient. An understanding of both abdominal and pelvic neuroanatomy may help clarify this phenomenon, as may knowledge of the concept of viscerosomatic convergence.1–3

Not only does the location of the endometriosis implant fail to predict the location of pain, but the level or stage of disease (in other words, the amount of endometriosis present) does not accurately predict the level of pain.4,5 In fact, some women with histopathologically confirmed endometriosis have no pain whatsoever.

When managing chronic pelvic pain (CPP), we need to consider mechanisms of pain when endometriosis is the primary pain driver, as well as when endometriosis is present but irrelevant to the patient’s pain (TABLE 1).

In this article, I focus on the role of endometriosis in CPP, including the role of the central nervous system (CNS) and other entities that may influence the pain threshold. This discussion is intended to help shift the current paradigm of thought about endometriosis and its association with CPP.

Numerous mechanisms drive pain in endometriosis

There are 2 main anatomic levels at which to consider pain associated with endometriosis—the local level (the endometriosis itself) and the level of the spinal cord and brain. Although emerging evidence points to a significant interaction between local anatomic disease and higher-order neurologically mediated pain,6–8 each level should be considered separately during selection of treatment.

At the most basic level, endometriosis is a disease of inflammation. Although the presence of inflammatory mediators is associated with the presence of endometriosis, the amount of endometriosis does not correlate with the amount of inflammatory mediators. Inflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL) 1, IL-6, IL-8, human monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, RANTES (Regulated on Activation Normal T cell Expressed and Secreted), and tumor necrosis factor alpha are found in significantly higher concentrations in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis, compared with women without endometriosis. The inflammatory mediators are produced by both endometriotic lesions and the surrounding peritoneum (Figure). This set of inflammatory mediators not only leads to angiogenesis and endometriosis tissue maintenance but also to neurogenesis.9 It is from this inflammatory environment that other pathogenic mechanisms can operate.

For example, when dorsal root ganglia are exposed to the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis, as opposed to the peritoneal fluid of women without endometriosis, there is a significant differential in the growth of sensory versus sympathetic neurites.10 This phenomenon translates into increased visceral pain sensitivity. In fact, it is this neurogenesis and increased neuronal responsiveness that are responsible for the upregulation of pain mediated by the spinal cord and brain.

A familiar but imperfectly understood theory is that of central sensitization. When there are prolonged and repeated pain impulses from peripheral sources, the CNS responds anatomically and biochemically by changing the processing of those pain signals. Even after the stimulus (in this case endometriosis) is removed for such high-intensity nociceptive signals, increasing excitability can continue. The result is chronic pain that is unresponsive or poorly responsive to treatment; in some cases, the chronic pain may even mimic the original anatomic site of the pain.

Central sensitization generally involves 2 phases: hyperalgesia, in which the excitatory threshold of the nerve is reset, leading to a lowered stimulatory requirement, and allodynia, in which normally harmless stimuli are interpreted as pain. During the allodynia phase, fibers (eg, C-fibers) that typically carry nonpainful information are recruited to become pain transmitters.

The pain threshold—and why it is important

The concept of the pain threshold is both complex and elusive. It can be defined as the point at which a stimulus begins to be perceived as painful. The pain threshold may be dependent on multiple variables, including gender, genetic issues (a concentration of mu receptors), a history of abuse, socioeconomic status, current and past levels of depression, earlier pain experiences, and psychosocial stressors.

The pain threshold is important because it changes over time. For example, a patient with endometriosis may experience isolated dysmenorrhea as a teen but, over time, may develop a pattern of chronic daily pain and depression. Or a woman with CPP may respond well to initial therapies but worsen after a stressful life event such as death of a loved one or new stressors at work. An understanding of the many variables that can alter the pain threshold can lead to more effective counseling and treatment and help us avoid unnecessary therapies.

Multiple types of pain can coexist in 1 patient

Clinicians who care for women with endometriosis and CPP should have an understanding of the mechanism of their pain, including the differences between nociceptive somatic, nociceptive visceral, and neuropathic pain (TABLE 2). All 3 types of pain can exist in a single patient with CPP.

Nociceptive somatic pain generally originates in somatic structures such as muscle, ligament, bone, and tendons. Women with endometriosis often have somatic pain, for 2 main reasons.11 First, skeletal muscles respond adversely to long-term inflammatory stimuli,12 and endometriosis is primarily a disease of inflammation. Long-term inflammatory stimuli may lead to atrophy and spasm. Second, the presence of inflammation in the muscle likely leads to worsening hyperalgesia with increasing muscle activity.13 This can lead to and explain pain in the pelvic floor, abdominal wall muscles, hips, thighs, buttocks, and lower back. Once this is understood, treatments can be targeted to the underlying mechanisms and specific muscle groups.

Nociceptive visceral pain generally indicates pain originating in visceral structures. In the pelvis, visceral structures of main concern are the uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes, vagina (upper two-thirds), bladder, ureters, sigmoid colon, rectum, and, most importantly related to endometriosis, the visceral peritoneum.

In the case of visceral pain, the likely associated mechanisms are inflammation as well as local nerve growth.14,15 Local inflammation in turn leads to scarring and visceral hyperalgesia.16 Over a long period of time, local visceral hyperalgesia can lead to spinal wind-up and central sensitization. Spinal wind-up is the spinal cord’s expansion of signals from peripheral nociceptors associated with C-fibers. It likely stems from a prolonged, intense, and persistent generation of afferent nociceptive impulses. When this occurs, CNS pathways are well established and sensations of pain can remain even after careful surgery to remove sources of inflammation and anatomic deformity (visceral scarring). For this reason, early radical resection of endometriosis in women with endometriosis-associated pelvic pain may be more likely than later surgery to reduce or eliminate pain. Otherwise, reoperation rates may be high and later surgeries may fail to yield histopathology for endometrial glands and stroma.17

Neuropathic pain generally reflects damage to or dysfunction of either the peripheral nervous system or the CNS. Endometriosis-associated pain is also neuropathic in nature and occurs through multiple mechanisms.

There is good evidence to support the development of abnormal nerve growth in and around areas of endometriosis. When such nerve fibers exist, they serve only a pathologic function. This abnormal nerve growth is induced by multiple molecules, including nerve growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.7 It is likely that once high-density areas of sensitized nerves develop, peripheral nerves also become sensitized by endometriosis-associated inflammatory cytokines.16 When there are abnormal nerve growth and elevated levels of peripheral nerve sensitization, the nerves most often recruited are C-fibers, unmyeli-nated fibers largely associated with both peripheral and central neuropathic pain. When C-fibers are recruited, the ratio of C-fibers to autonomic afferent pain fibers increases.

In endometriosis, persistent inflammatory signals lead to an increase in the excitability of peripheral nerves, thereby significantly increasing transmitted pain signals and likely reducing the body’s ability to suppress pain.

Some of the peripheral nerve changes I have described may be observed via magnetic resonance tractography (MRT), which highlights neuronal tracts over long distances. Fractional anisotropy values measured by MRT yield information about the quality of neuronal structures. In women with endometriosis, fractional anisotropy values in the peripheral nerve roots of S1, S2, and S3 appear to be lower than those in women without endometriosis,18 indicating disruption of the normally myelinated nerve structure.

It’s time to abandon nontargeted treatments

Endometriosis-associated CPP remains a challenging heterogeneous and multifactorial disease state. In the past, treatments such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists have been prescribed without an appropriate consideration of the disease and its mechanism of associated pain. In our CPP specialty practice, we have abandoned such nontargeted approaches. By developing an understanding of central sensitization, local neurologic responses to inflammation, and the pain threshold, clinicians are more likely to select a treatment targeted to specific mechanisms. Such an approach is superior to the traditional “shotgun” approach to treatment, which can produce harmful side effects and have high long-term failure rates. As Stratton and colleagues observed, “traditional methods of classifying endometriosis-associated pain based on disease, duration, and anatomy are inadequate and should be replaced by a mechanism-based evaluation.”19 Future clinical care and research will necessarily focus on specific disease etiologies and pain mechanisms if we are to continue to improve the care of women with CPP.

Case: Resolved

Because the history, physical examination, and imaging are strongly suggestive of endometriosis, the patient is counseled about the treatments most likely to be effective, which include medical therapies such as centrally acting agents (gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants) and local treatments such as placement of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or surgical resection. She elects to undergo total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy and radical resection of endometriosis. Histopathology confirms adenomyosis and deep infiltrating endometriosis, including implants on the rectovaginal septum. The patient remains pain-free at her 2-year follow-up.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE: Resurgent, worsening dysmenorrhea

A 32-year-old woman (G2P2) with a history of 2 spontaneous vaginal deliveries presents to your office after 10 months of severe, worsening dysmenorrhea. Shortly after she developed severe dysmenorrhea, she began to experience daily pain in her lower abdomen and pelvis. This pain occurred in the midline, bilateral lower quadrants, and rectum. She also developed deep dyspareunia.

She has a history of dysmenorrhea from adolescence but has otherwise been healthy and pain-free until the past 10 months. She has tried oral contraceptives and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, without success. She is happily married, and her medical history is unremarkable except for a bout of Lyme disease 6 months before the onset of pain, at which time she also developed symptoms of fatigue.

A physical examination is remarkable for unilateral thickening and shortening of the left uterosacral ligament, dense scarring, and tenderness at the posterior fornix, with poor uterine mobility. Magnetic resonance imaging reveals findings consistent with the physical examination.

What is causing her pain after such a long phase without it? And what treatments should you offer her?

Endometriosis represents the ectopic presence of endometrial glands and stroma. The most common sites of endometriotic implants are the uterosacral ligaments, cul-de-sac peritoneum, and ovarian fossae. Most clinicians are aware that the location of an endometriosis implant does not predict the location of pain experienced by the patient. An understanding of both abdominal and pelvic neuroanatomy may help clarify this phenomenon, as may knowledge of the concept of viscerosomatic convergence.1–3

Not only does the location of the endometriosis implant fail to predict the location of pain, but the level or stage of disease (in other words, the amount of endometriosis present) does not accurately predict the level of pain.4,5 In fact, some women with histopathologically confirmed endometriosis have no pain whatsoever.

When managing chronic pelvic pain (CPP), we need to consider mechanisms of pain when endometriosis is the primary pain driver, as well as when endometriosis is present but irrelevant to the patient’s pain (TABLE 1).

In this article, I focus on the role of endometriosis in CPP, including the role of the central nervous system (CNS) and other entities that may influence the pain threshold. This discussion is intended to help shift the current paradigm of thought about endometriosis and its association with CPP.

Numerous mechanisms drive pain in endometriosis

There are 2 main anatomic levels at which to consider pain associated with endometriosis—the local level (the endometriosis itself) and the level of the spinal cord and brain. Although emerging evidence points to a significant interaction between local anatomic disease and higher-order neurologically mediated pain,6–8 each level should be considered separately during selection of treatment.

At the most basic level, endometriosis is a disease of inflammation. Although the presence of inflammatory mediators is associated with the presence of endometriosis, the amount of endometriosis does not correlate with the amount of inflammatory mediators. Inflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL) 1, IL-6, IL-8, human monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, RANTES (Regulated on Activation Normal T cell Expressed and Secreted), and tumor necrosis factor alpha are found in significantly higher concentrations in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis, compared with women without endometriosis. The inflammatory mediators are produced by both endometriotic lesions and the surrounding peritoneum (Figure). This set of inflammatory mediators not only leads to angiogenesis and endometriosis tissue maintenance but also to neurogenesis.9 It is from this inflammatory environment that other pathogenic mechanisms can operate.

For example, when dorsal root ganglia are exposed to the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis, as opposed to the peritoneal fluid of women without endometriosis, there is a significant differential in the growth of sensory versus sympathetic neurites.10 This phenomenon translates into increased visceral pain sensitivity. In fact, it is this neurogenesis and increased neuronal responsiveness that are responsible for the upregulation of pain mediated by the spinal cord and brain.

A familiar but imperfectly understood theory is that of central sensitization. When there are prolonged and repeated pain impulses from peripheral sources, the CNS responds anatomically and biochemically by changing the processing of those pain signals. Even after the stimulus (in this case endometriosis) is removed for such high-intensity nociceptive signals, increasing excitability can continue. The result is chronic pain that is unresponsive or poorly responsive to treatment; in some cases, the chronic pain may even mimic the original anatomic site of the pain.

Central sensitization generally involves 2 phases: hyperalgesia, in which the excitatory threshold of the nerve is reset, leading to a lowered stimulatory requirement, and allodynia, in which normally harmless stimuli are interpreted as pain. During the allodynia phase, fibers (eg, C-fibers) that typically carry nonpainful information are recruited to become pain transmitters.

The pain threshold—and why it is important

The concept of the pain threshold is both complex and elusive. It can be defined as the point at which a stimulus begins to be perceived as painful. The pain threshold may be dependent on multiple variables, including gender, genetic issues (a concentration of mu receptors), a history of abuse, socioeconomic status, current and past levels of depression, earlier pain experiences, and psychosocial stressors.

The pain threshold is important because it changes over time. For example, a patient with endometriosis may experience isolated dysmenorrhea as a teen but, over time, may develop a pattern of chronic daily pain and depression. Or a woman with CPP may respond well to initial therapies but worsen after a stressful life event such as death of a loved one or new stressors at work. An understanding of the many variables that can alter the pain threshold can lead to more effective counseling and treatment and help us avoid unnecessary therapies.

Multiple types of pain can coexist in 1 patient

Clinicians who care for women with endometriosis and CPP should have an understanding of the mechanism of their pain, including the differences between nociceptive somatic, nociceptive visceral, and neuropathic pain (TABLE 2). All 3 types of pain can exist in a single patient with CPP.

Nociceptive somatic pain generally originates in somatic structures such as muscle, ligament, bone, and tendons. Women with endometriosis often have somatic pain, for 2 main reasons.11 First, skeletal muscles respond adversely to long-term inflammatory stimuli,12 and endometriosis is primarily a disease of inflammation. Long-term inflammatory stimuli may lead to atrophy and spasm. Second, the presence of inflammation in the muscle likely leads to worsening hyperalgesia with increasing muscle activity.13 This can lead to and explain pain in the pelvic floor, abdominal wall muscles, hips, thighs, buttocks, and lower back. Once this is understood, treatments can be targeted to the underlying mechanisms and specific muscle groups.

Nociceptive visceral pain generally indicates pain originating in visceral structures. In the pelvis, visceral structures of main concern are the uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes, vagina (upper two-thirds), bladder, ureters, sigmoid colon, rectum, and, most importantly related to endometriosis, the visceral peritoneum.

In the case of visceral pain, the likely associated mechanisms are inflammation as well as local nerve growth.14,15 Local inflammation in turn leads to scarring and visceral hyperalgesia.16 Over a long period of time, local visceral hyperalgesia can lead to spinal wind-up and central sensitization. Spinal wind-up is the spinal cord’s expansion of signals from peripheral nociceptors associated with C-fibers. It likely stems from a prolonged, intense, and persistent generation of afferent nociceptive impulses. When this occurs, CNS pathways are well established and sensations of pain can remain even after careful surgery to remove sources of inflammation and anatomic deformity (visceral scarring). For this reason, early radical resection of endometriosis in women with endometriosis-associated pelvic pain may be more likely than later surgery to reduce or eliminate pain. Otherwise, reoperation rates may be high and later surgeries may fail to yield histopathology for endometrial glands and stroma.17

Neuropathic pain generally reflects damage to or dysfunction of either the peripheral nervous system or the CNS. Endometriosis-associated pain is also neuropathic in nature and occurs through multiple mechanisms.

There is good evidence to support the development of abnormal nerve growth in and around areas of endometriosis. When such nerve fibers exist, they serve only a pathologic function. This abnormal nerve growth is induced by multiple molecules, including nerve growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.7 It is likely that once high-density areas of sensitized nerves develop, peripheral nerves also become sensitized by endometriosis-associated inflammatory cytokines.16 When there are abnormal nerve growth and elevated levels of peripheral nerve sensitization, the nerves most often recruited are C-fibers, unmyeli-nated fibers largely associated with both peripheral and central neuropathic pain. When C-fibers are recruited, the ratio of C-fibers to autonomic afferent pain fibers increases.

In endometriosis, persistent inflammatory signals lead to an increase in the excitability of peripheral nerves, thereby significantly increasing transmitted pain signals and likely reducing the body’s ability to suppress pain.

Some of the peripheral nerve changes I have described may be observed via magnetic resonance tractography (MRT), which highlights neuronal tracts over long distances. Fractional anisotropy values measured by MRT yield information about the quality of neuronal structures. In women with endometriosis, fractional anisotropy values in the peripheral nerve roots of S1, S2, and S3 appear to be lower than those in women without endometriosis,18 indicating disruption of the normally myelinated nerve structure.

It’s time to abandon nontargeted treatments

Endometriosis-associated CPP remains a challenging heterogeneous and multifactorial disease state. In the past, treatments such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists have been prescribed without an appropriate consideration of the disease and its mechanism of associated pain. In our CPP specialty practice, we have abandoned such nontargeted approaches. By developing an understanding of central sensitization, local neurologic responses to inflammation, and the pain threshold, clinicians are more likely to select a treatment targeted to specific mechanisms. Such an approach is superior to the traditional “shotgun” approach to treatment, which can produce harmful side effects and have high long-term failure rates. As Stratton and colleagues observed, “traditional methods of classifying endometriosis-associated pain based on disease, duration, and anatomy are inadequate and should be replaced by a mechanism-based evaluation.”19 Future clinical care and research will necessarily focus on specific disease etiologies and pain mechanisms if we are to continue to improve the care of women with CPP.

Case: Resolved

Because the history, physical examination, and imaging are strongly suggestive of endometriosis, the patient is counseled about the treatments most likely to be effective, which include medical therapies such as centrally acting agents (gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants) and local treatments such as placement of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or surgical resection. She elects to undergo total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy and radical resection of endometriosis. Histopathology confirms adenomyosis and deep infiltrating endometriosis, including implants on the rectovaginal septum. The patient remains pain-free at her 2-year follow-up.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Brumovsky PR, Gebhart GF. Visceral organ cross-sensitization—an integrated perspective. Auton Neurosci. 2010;153(1–2):106–115.

2. Schwartz ES, Gebhart GF. Visceral pain. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2014;20:171–197.

3. Gebhart GF. Visceral pain—peripheral sensitization. Gut. 2000;47(suppl 4):54–58.

4. Fukaya T, Hoshiai H, Yajima A. Is pelvic endometriosis always associated with chronic pain? A retrospective study of 618 cases diagnosed by laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(3):719–722.

5. Vercellini P, Trespidi L, De GO, Cortesi I, Parazzini F, Crosignani PG. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: relation to disease stage and localization. Fertil Steril. 1996;65(2):299–304.

6. Brawn J, Morotti M, Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Vincent K. Central changes associated with chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):737–747.

7. Morotti M, Vincent K, Brawn J, Zondervan KT, Becker CM. Peripheral changes in endometriosis-associated pain. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):717–736.

8. Neziri AY, Bersinger NA, Andersen OK, Arendt-Nielsen L, Mueller MD, Curatolo M. Correlation between altered central pain processing and concentration of peritoneal fluid inflammatory cytokines in endometriosis patients with chronic pelvic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39(3):181–184.

9. Asante A, Taylor RN. Endometriosis: the role of neuroangiogenesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:163–182.

10. Arnold J, Barcena de Arellano ML, Ruster C, et al. Imbalance between sympathetic and sensory innervation in peritoneal endometriosis. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(1):132–141.

11. Warren JW, Morozov V, Howard FM. Could chronic pelvic pain be a functional somatic syndrome? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(3):199–205.

12. Korotkova M, Lundberg IE. The skeletal muscle arachidonic acid cascade in health and inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(5):295–303.

13. Sluka KA, Rasmussen LA. Fatiguing exercise enhances hyperalgesia to muscle inflammation. Pain. 2010;148(2):188–197.

14. McKinnon B, Bersinger NA, Wotzkow C, Mueller MD. Endometriosis-associated nerve fibers, peritoneal fluid cytokine concentrations, and pain in endometriotic lesions from different locations. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(2):373–380.

15. Anaf V, El Nakadi I, De Moor V, Chapron C, Pistofidis G, Noel JC. Increased nerve density in deep infiltrating endometriotic nodules. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;71(2):112–117.

16. McKinnon BD, Bertschi D, Bersinger NA, Mueller MD. Inflammation and nerve fiber interaction in endometriotic pain. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(1):1–10.

17. Redwine DB. Conservative laparoscopic excision of endometriosis by sharp dissection: life table analysis of reoperation and persistent or recurrent disease. Fertil Steril. 1991;56(4):628–634.

18. Manganaro L, Porpora MG, Vinci V, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging and tractography to evaluate sacral nerve root abnormalities in endometriosis-related pain: a pilot study. Eur Radiol. 2014;24(1):95–101.

19. Stratton P, Khachikyan I, Sinaii N, Ortiz R, Shah J. Association of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis with signs of sensitization and myofascial pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):719–728.

1. Brumovsky PR, Gebhart GF. Visceral organ cross-sensitization—an integrated perspective. Auton Neurosci. 2010;153(1–2):106–115.

2. Schwartz ES, Gebhart GF. Visceral pain. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2014;20:171–197.

3. Gebhart GF. Visceral pain—peripheral sensitization. Gut. 2000;47(suppl 4):54–58.

4. Fukaya T, Hoshiai H, Yajima A. Is pelvic endometriosis always associated with chronic pain? A retrospective study of 618 cases diagnosed by laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(3):719–722.

5. Vercellini P, Trespidi L, De GO, Cortesi I, Parazzini F, Crosignani PG. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: relation to disease stage and localization. Fertil Steril. 1996;65(2):299–304.

6. Brawn J, Morotti M, Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Vincent K. Central changes associated with chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):737–747.

7. Morotti M, Vincent K, Brawn J, Zondervan KT, Becker CM. Peripheral changes in endometriosis-associated pain. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):717–736.

8. Neziri AY, Bersinger NA, Andersen OK, Arendt-Nielsen L, Mueller MD, Curatolo M. Correlation between altered central pain processing and concentration of peritoneal fluid inflammatory cytokines in endometriosis patients with chronic pelvic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39(3):181–184.

9. Asante A, Taylor RN. Endometriosis: the role of neuroangiogenesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:163–182.

10. Arnold J, Barcena de Arellano ML, Ruster C, et al. Imbalance between sympathetic and sensory innervation in peritoneal endometriosis. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(1):132–141.

11. Warren JW, Morozov V, Howard FM. Could chronic pelvic pain be a functional somatic syndrome? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(3):199–205.

12. Korotkova M, Lundberg IE. The skeletal muscle arachidonic acid cascade in health and inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(5):295–303.

13. Sluka KA, Rasmussen LA. Fatiguing exercise enhances hyperalgesia to muscle inflammation. Pain. 2010;148(2):188–197.

14. McKinnon B, Bersinger NA, Wotzkow C, Mueller MD. Endometriosis-associated nerve fibers, peritoneal fluid cytokine concentrations, and pain in endometriotic lesions from different locations. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(2):373–380.

15. Anaf V, El Nakadi I, De Moor V, Chapron C, Pistofidis G, Noel JC. Increased nerve density in deep infiltrating endometriotic nodules. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;71(2):112–117.

16. McKinnon BD, Bertschi D, Bersinger NA, Mueller MD. Inflammation and nerve fiber interaction in endometriotic pain. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(1):1–10.

17. Redwine DB. Conservative laparoscopic excision of endometriosis by sharp dissection: life table analysis of reoperation and persistent or recurrent disease. Fertil Steril. 1991;56(4):628–634.

18. Manganaro L, Porpora MG, Vinci V, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging and tractography to evaluate sacral nerve root abnormalities in endometriosis-related pain: a pilot study. Eur Radiol. 2014;24(1):95–101.

19. Stratton P, Khachikyan I, Sinaii N, Ortiz R, Shah J. Association of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis with signs of sensitization and myofascial pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):719–728.

In This Article

- The pain threshold and why it is important

- Types of pain and their implications

- It’s time to abandon nontargeted treatments