User login

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic disease that is commonly reported in older adults in primary care. Many adults aged > 65 years with DM have other chronic diseases that make management of their care more complex. Overseeing DM care in older adults while comanaging other chronic diseases is a challenge to health care providers (HCPs). The terms older adults and geriatric define persons aged ≥ 65 years.

Diabetes mellitus is growing at a rapid rate, and older adults are at higher risk. In 2012, about 29.1 million people in the U.S. (9.3%) were diagnosed with DM. Of that number, 11.2 million were aged ≥ 65 years. Additionally, 86 million adults had prediabetes when fasting blood glucose and A1c levels were reviewed. Also in 2012, more than 400,000 new cases (11.5 per 1,000 people) were diagnosed in the aged ≥ 65 years group.1-3 This age group is anticipated to double in 25 years, and the incidence of DM is projected to increase 3.2-fold.4 By 2050, 26.7 million older adults—55% of the older adult population—will have DM. As a result, HCPs are faced with treating escalating numbers of older adults with DM as the population ages.4

In 2012, the total cost of DM for the U.S. population was $245 billion: The direct cost of medical care was $176 billion, and the indirect costs in productivity, absenteeism, unemployment, disability, and premature death was nearly $69 billion.2 This is a significant burden in terms of health care costs, productivity, disability, sick days, early retirement, and premature death. Diabetes mellitus increases atherosclerosis and thus accelerates the risk for heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, blindness, and limb amputations.2

Managing DM concurrently with multiple chronic comorbid conditions is challenging. Patients are asked to bring blood glucose under tight control, perform regular blood glucose testing, take antiglycemic medications, watch their diet, lose weight, and exercise regularly—all while managing other chronic diseases. Many older patients are overwhelmed by the demands of self-management recommended by their HCPs. Similarly, HCPs are frustrated with their older patients, who are unable to adequately meet targeted goals for DM management and thereby reduce the associated risks for complications.

The purpose of this article is to discuss the common barriers to DM management, the experiences of patients and HCPs regarding those barriers, and the management strategies for overcoming barriers in treating older adults with DM.

What Are The Barriers?

The experiences of both patients and HCPs matter when working to overcome DM barriers. If no one understands the problem, no one can fix it. What concerns do patients and HCPs have? Do they really value each other’s perspectives? To overcome barriers, can HCPs and patients develop mutually agreed on goals that are reasonable and practical to implement within the framework of a partnership?

Patient Experiences

Continuity of care and access. Some older adults are seen by multiple HCPs during health care visits, and as a result, they receive mixed messages on what is expected of them.3 Patients feel they have a greater sense of security and confidence when they have a therapeutic relationship with a trusted HCP; they feel more connected and confident about their health care system.5

Lack of education. Many patients say they need more DM education, guidance, and support.6 They report that HCPs tell them how to control DM to avoid complications but say they need more education on how DM affects their lives and concrete suggestions on how to change their lifestyles. Researchers say patients need to feel empowered so they can take a leadership role in managing medications, diet, exercise, preventive foot and eye care, and stress.7 In contrast, an empowerment approach identifies patients’ inherent capacity to self-direct and motivate themselves to develop a self-managed plan based on their personal goals and priorities.8 Patients want to be part of the solution.

Communication and language. A significant challenge for elderly patients is loss of hearing and/or vision, which results in difficulty communicating with their HCP.9 The loss of hearing or vision decreases the ability to adequately collaborate with HCPs and hampers an older adult’s ability to take the lead on self-management. As the U.S. population becomes more diverse, language also poses a significant barrier to care. A language barrier inherently affects health literacy about the disease as well as patients’ perceived trust in HCPs to manage their disease.3

Medication regimen. There are numerous barriers to taking medications. Polypharmacy is a common cause of more drug interactions and adverse effects, which are the most common reason for stopping medications.3,10 Cost of medications and difficulty keeping track of multiple medications are also a deterrent to self-management and adherence. Polypharmacy is seen as detrimental to quality of life (QOL).3 Some patients are also resistant to the initiation and titration of insulin.11

Lack of resources. Many patients cite a lack of resources to facilitate DM care. Common barriers include delays in being scheduled for medical appointments, lack of transportation to appointments, difficulty paying out-of-pocket copays, high cost of medications, and cost of DM supplies (eg, glucometers, test strips, insulin pens and/or pumps). The lack of access to community green spaces or gyms to increase physical activity is also a common barrier.12

Health Care Provider Experiences

Lack of motivation. Health care providers’ experiences and motivations can also present barriers to care. Some HCPs believe that evidence-based guidelines are simply theoretical frameworks; they disagree with using these guidelines as a basis to initiate statin therapy or antiglycemic medications, which reduce cardiovascular complications.13 Many also feel justified in taking a more lax approach when treating older adults due to a lack of time.13

Lack of education about DM management. Health care providers often feel less prepared to provide DM care and believe additional education in DM care is needed. Many lack formal postgraduate DM education or professional development, and 19.6% have no postgraduate DM education or training.14 Some are uncomfortable managing insulin because of a lack of knowledge of insulin therapy and its effect on cardiovascular risk. This results in patients remaining too long on oral DM medications and delaying the necessary initiation of insulin.13

Lack of resources. Some HCPs do not have qualified staff, such as dieticians and diabetes nurse educators, to support DM care. Fearing a loss of control over individual patient care, some HCPs also find it difficult to collaborate with multidisciplinary diabetes care team members, such as psychologists and diabetes educators.13 A lack of awareness of community programs hampers HCPs’ ability to get patients connected to resources that help them make lifestyle changes.14

Lack of involvement or empowerment. Health care providers often think patients do not act with a sense of empowerment in DM management. Health care providers commonly perceive patients as lacking the motivation to change and say that as many as 30% of patients are uncooperative, regardless of proposed changes.13 Many are convinced that patients are unwilling to make even small lifestyle adjustments, such as getting physically active and losing weight. Health care providers say patients do not ask questions about DM selfmanagement during visits and often do not verbalize how HCPs can best support their needs.15 They say that patients are so entrenched in their habits, they even refuse DM education.13

Management Strategies

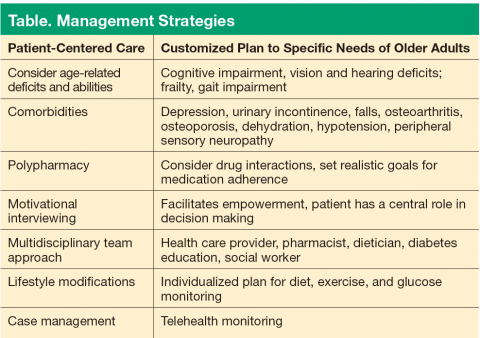

Several strategies can be deployed to overcome barriers in DM care. Of utmost importance is the need to provide patient-centered care with age-specific characteristics of older adults (Table). To foster mutual collaboration in DM care, HCPs need to ask patients about their health care goals. Patients often view their health through a functional and social perspective rather than from a biomedical perspective. In one study, 71% of patients said their most common health goal was to be independent with activities of daily living, which was more important than the specific details of DM care.16 Preventing DM complications was among their secondary health care goals.

A DM care plan for older adults should be individualized with careful consideration given to medical history, functional capacity, home care environment, and life expectancy. Many older adults have health problems, such as impaired vision, cognitive impairment, depression, and peripheral sensory neuropathy. They may have osteoarthritis of the knees, osteoporosis of the hip and spine, or urinary incontinence; all these conditions increase the risk for falls. Many older adults are on multiple medications, which can increase falls by causing dizziness, dehydration, or hypotension.17 Polypharmacy can negatively impact one or more comorbid conditions and QOL.18

The clinical guidelines for DM management are based on studies conducted in younger populations. However, the 2015 guidelines from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) have been tailored to consider level of health, frailty, cognition, comorbidities, and life expectancy of older adults. The 2015 ADA recommendations provide a framework to guide treatment goals in older adults. A reasonable goal for healthy older adults with few chronic diseases, intact cognition, high functional status, and an anticipated longer remaining life expectancy is an A1c of < 7.5%.19 For older adults with comorbidities of intermediate complexity, such as mild cognitive impairment, an A1c treatment goal of < 8.0% is suggested. An A1c goal of < 8.5% is recommended for older adults in poor health, such as those with end-stage chronic disease, significant cognitive impairment, or those in long-term care. Health care providers may choose to further individualize A1c treatment goals to < 7% if patients are healthy and if treatment burdens are not severe or excessive.19

Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Chronic illness in older adults can be complex to manage due to competing comorbidities and polypharmacy. A diabetes care team consisting of a dietician, social worker, pharmacist, and certified diabetes educator is well suited to effectively manage DM in older adults. Up to 10 hours of DM education with a registered dietician or certified diabetes educator is covered under Medicare in a 12-month period if at least one of the following criteria are met: new diagnosis of DM with A1c > 8.5%, recent initiation of medication, or a high risk for complications.20

Motivational Interviewing

Many HCPs are frustrated that they are unable to persuade patients to adhere to their DM care recommendations. Health care providers often use strategies such as badgering or blaming patients for being nonadherent or scare tactics about the negative consequences of the disease.21 This approach is often ineffective and results in patients becoming more resistant to change.

Motivational interviewing using open-ended questions is an evidenced-based counseling technique that has been shown to elicit sustained behavioral changes. Motivational interviewing increases intrinsic motivation within patients and establishes a goal of incorporating patient-centered values into care by examining ambivalence and passivity in a nonjudgmental way.22 Motivational interviewing facilitates empowerment by using a decision-making process based on each individual’s unique physical, emotional, and environmental circumstances. With guidance from HCPs, patients are able to set the ground rules for DM management by defining a plan that works best for them. For example, a patient may consider a meal plan with stricter caloric intake vs one with a higher calorie count but with more frequent insulin injections or blood glucose monitoring. This strategy puts patients at the center of decision making about medications, diet, and exercise. It also allows them to implement an individualized plan that they believe will work best for them based on their own perceived goals, priorities, and stressors. This approach is shown to work effectively in DM care.8,23

Medication Regimen and Glucose Monitoring

Hypoglycemia is a major concern when managing DM in older adults.20 Hypoglycemia can be triggered by polypharmacy, cognitive impairment, renal insufficiency, sedatives, alcohol intake, malnutrition, and the use of sulfonylureas or insulin. Medications should be considered within the context of other geriatric problems such as falls, depression, urinary incontinence, and pain.20 A simplified approach based on the patient’s functional and cognitive abilities is a good starting point.20 Unless contraindicated, medication initiation could begin with a biguanide.1 Sulfonylureas should generally be avoided in older adults due to the high risk of hypoglycemia.1 Older adults with frequent hypoglycemia should be referred to an endocrinologist or diabetes educator for further management.24

Insulin therapy is recommended if oral therapy alone is insufficient or fails.20 Insulin can be prescribed with adequate DM education and blood glucose monitoring. When prescribing insulin, HCPs should consider older patients’ physical dexterity, visual acuity, cognitive function, financial circumstances, and family support to determine whether insulin therapy is a realistic option that patients can appropriately manage.12,20

Many older adults are resistant to starting insulin and are often reluctant to titrate insulin doses between clinic visits as prescribed by HCPs.12 Older adults on insulin need reassurance and education from a diabetes educator or HCP to gain confidence in adjusting insulin.12 A simple approach to starting insulin can be to start with an evening dose of long-acting insulin.20 Short-acting agents can be added later as needed to control postprandial hyperglycemia.20 Prefilled insulin flex pens also provide a quick and easy way to administer insulin in precise doses.20

Barriers to self-monitoring of blood glucose include pain from finger sticks, inconvenience of testing, and the expense of test strips.25 The newer glucometers and test strips use smaller amounts of blood from other body parts such as the upper arm, calf, or thigh, and these glucometers are ideally suited for older adults.20

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle interventions, including weight loss and exercise, are the mainstay in glycemic control of diabetes. The Diabetes Prevention Program study found a group of patients on lifestyle intervention alone (weight loss goal of 7% and ≥ 150 minutes of weekly exercise) had a 58% lower prevalence of DM compared with a group of patients taking metformin, which had a 31% lower prevalence.26 When older adults were compared with younger persons, lifestyle interventions were more effective than was taking metformin. High-intensity resistance training with moderate weights and repetition lowered glycemic index and caused a 3-fold reduction in A1c in older patients.27,28

Case Management

Older adults may have difficulty getting in touch with HCPs through traditional automated telephone systems. Many have difficulty transmitting glucose monitoring log sheets to HCPs for medication adjustments, which can result in delayed interventions. Telephone visits initiated by a competent case manager can serve as a primary point of contact between HCPs and older adults to optimize treatment and effectively get patients to targeted goals.

Telemedicine is an important tool for monitoring older adults in their home. The technology includes installing a home telemedicine unit, which supports videoconferencing, exchanging messages with case managers, uploading blood glucose readings, and accessing DM educational materials. A study on medication adherence in older diabetic patients found increased adherence through telemonitoring.29 Telemedicine can quickly identify new or persistent barriers between clinic visits so interventions can be made.

A case manager can also facilitate family and social support to address issues such as infrequent glucose monitoring, infrequent medical appointments, caregiver stress, lack of transportation, and financial difficulties, all of which can adversely affect DM care for older adults. The use of a network of family and friends is a good tool for DM management. One study found that when family or friends attended clinic visits, patients were more motivated to understand, follow HCP advice, and find resolutions to difficult issues in DM care.30

Conclusion

Diabetes is a chronic illness with a high burden for older adults. It is important to understand the experiences of patients and HCPs that influence common diabetes barriers. In older adults, barriers should be evaluated in an age-specific context to devise practical interventions to overcome them. Individualizing therapies and empowering older adults prepares them to live confidently while maintaining a sense of control over their lives. A patientcentered collaboration between HCPs and older adults that incorporates a multidisciplinary team approach to resolve problems can improve patient outcomes.

Additional research is needed to identify methods that are most suitable and applicable to older adults. If new evidenced-based research can eliminate diabetes barriers and improve diabetes care in older adults, the consequential burden of diabetes is more likely to decline.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Care of Older Adults With Diabetes Mellitus; Moreno G, Mangione CM, Kimbro L, Vaisberg E. Guidelines abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for Improving the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 Update. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):2020-2026.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

3. Williams A, Manias E. Exploring motivation and confidence in taking prescribed medicines in coexisting diseases: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(3-4):471-481.

4. Narayan KMV, Boyle JP, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB, Thompson TJ. Impact of recent

increase in incidence on future diabetes burden: U.S., 2005-2050. Diabetes Care.

2006;29(9):2114-2116.

5. von Bültzingslöwen I, Eliasson G, Sarvimäki A, Mattsson B, Hjortdahl P. Patients’ views on interpersonal continuity in primary care: a sense of security based on four core foundations. Fam Pract. 2006;23(2):210-219.

6. Koenigsberg MR, Bartlett D, Cramer JS. Facilitating treatment adherence with lifestyle changes in diabetes. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(2):309-316.

7. Mensing C, Boucher J, Cypress M, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Task Force to Review and Revise the National Standards for Diabetes Self-Management Education Programs. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(5):682-689.

8. Funnell MM, Weiss MA. Empowering patients with diabetes. Nursing. 2009;39(3):34-37.

9. Hammouda EI. Overcoming barriers to diabetes control in geriatrics. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(4):420-424.

10. Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2650-2664.

11. Brod M, Kongsø JH, Lessard S, Christensen TL. Psychological insulin resistance: patient beliefs and implications for diabetes management. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):23-32.

12. Munshi MN, Segal AR, Suhl E, et al. Assessment of barriers to improve diabetes management in older adults: a randomized controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(3):543-549.

13. Goderis G, Borgermans L, Mathieu C, et al. Barriers and facilitators to evidence based care of type 2 diabetes patients: experiences of general practitioners participating to a quality improvement program. Implement Sci. 2009;4:41.

14. Raaijmakers LGM, Hamers FJM, Martens MK, Bagchus C, de Vries NK, Kremers SPJ. Perceived facilitators and barriers in diabetes care: a qualitative study among health care professionals in the Netherlands. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14(1):114.

15. Holt RIG, Nicolucci A, Kovacs Burns K, et al; DAWN2 Study Group. Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs second study (DAWN2™): cross-national comparisons on barriers and resources for optimal care—healthcare professional perspective. Diabet Med. 2013;30(7):789-798.

16. Huang ES, Gorawara-Bhat R, Chin MH. Self-reported goals of older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):306-311.

17. Haas LB. Special considerations for older adults with diabetes residing in skilled nursing facilities. Diabetes Spectrum. 2014;27(1):37-43.

18. Mason NA, Bakus JL. Strategies for reducing polypharmacy and other medicationrelated problems in chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial. 2010;23(1):55-61.

19. American Diabetes Association. Older adults. Sec.10. In Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(suppl 1):S67-S69.

20. Hornick T, Aron DC. Managing diabetes in the elderly: go easy, individualize. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(1):70-78.

21. Gabbay RA, Durdock K. Strategies to increase adherence through diabetes technology. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(3):661-665.

22. Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008.

23. West D, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, Greene PG. Motivational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1081-1087.

24. Graber AL, Elasy TA, Quinn D, Wolff K, Brown A. Improving glycemic control in adults with diabetes mellitus: shared responsibility in primary care practices. South Med J. 2002;95(7):684-690.

25. Zgibor JC, Simmons D. Barriers to blood glucose monitoring in a multiethnic community. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1772-1777.

26. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393-403.

27. Witham MD, Avenell A. Interventions to achieve long-term weight loss in obese older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2010;39(2):176-184.

28. Dunstan DW, Daly RM, Owen N, et al. High-intensity resistance training improves glycemic control in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1729-1736.

29. Brath H, Morak J, Kästenbauer T, et al. Mobile health (mHealth) based medication adherence measurement–a pilot trial using electronic blisters in diabetes patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(suppl 1):47-55.

30. Rosland AM, Piette JD, Choi H, Heisler M. Family and friend participation in primary care visits of patients with diabetes or heart failure: patient and physician determinants and experiences. Med Care. 2011;49(1):37-45.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic disease that is commonly reported in older adults in primary care. Many adults aged > 65 years with DM have other chronic diseases that make management of their care more complex. Overseeing DM care in older adults while comanaging other chronic diseases is a challenge to health care providers (HCPs). The terms older adults and geriatric define persons aged ≥ 65 years.

Diabetes mellitus is growing at a rapid rate, and older adults are at higher risk. In 2012, about 29.1 million people in the U.S. (9.3%) were diagnosed with DM. Of that number, 11.2 million were aged ≥ 65 years. Additionally, 86 million adults had prediabetes when fasting blood glucose and A1c levels were reviewed. Also in 2012, more than 400,000 new cases (11.5 per 1,000 people) were diagnosed in the aged ≥ 65 years group.1-3 This age group is anticipated to double in 25 years, and the incidence of DM is projected to increase 3.2-fold.4 By 2050, 26.7 million older adults—55% of the older adult population—will have DM. As a result, HCPs are faced with treating escalating numbers of older adults with DM as the population ages.4

In 2012, the total cost of DM for the U.S. population was $245 billion: The direct cost of medical care was $176 billion, and the indirect costs in productivity, absenteeism, unemployment, disability, and premature death was nearly $69 billion.2 This is a significant burden in terms of health care costs, productivity, disability, sick days, early retirement, and premature death. Diabetes mellitus increases atherosclerosis and thus accelerates the risk for heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, blindness, and limb amputations.2

Managing DM concurrently with multiple chronic comorbid conditions is challenging. Patients are asked to bring blood glucose under tight control, perform regular blood glucose testing, take antiglycemic medications, watch their diet, lose weight, and exercise regularly—all while managing other chronic diseases. Many older patients are overwhelmed by the demands of self-management recommended by their HCPs. Similarly, HCPs are frustrated with their older patients, who are unable to adequately meet targeted goals for DM management and thereby reduce the associated risks for complications.

The purpose of this article is to discuss the common barriers to DM management, the experiences of patients and HCPs regarding those barriers, and the management strategies for overcoming barriers in treating older adults with DM.

What Are The Barriers?

The experiences of both patients and HCPs matter when working to overcome DM barriers. If no one understands the problem, no one can fix it. What concerns do patients and HCPs have? Do they really value each other’s perspectives? To overcome barriers, can HCPs and patients develop mutually agreed on goals that are reasonable and practical to implement within the framework of a partnership?

Patient Experiences

Continuity of care and access. Some older adults are seen by multiple HCPs during health care visits, and as a result, they receive mixed messages on what is expected of them.3 Patients feel they have a greater sense of security and confidence when they have a therapeutic relationship with a trusted HCP; they feel more connected and confident about their health care system.5

Lack of education. Many patients say they need more DM education, guidance, and support.6 They report that HCPs tell them how to control DM to avoid complications but say they need more education on how DM affects their lives and concrete suggestions on how to change their lifestyles. Researchers say patients need to feel empowered so they can take a leadership role in managing medications, diet, exercise, preventive foot and eye care, and stress.7 In contrast, an empowerment approach identifies patients’ inherent capacity to self-direct and motivate themselves to develop a self-managed plan based on their personal goals and priorities.8 Patients want to be part of the solution.

Communication and language. A significant challenge for elderly patients is loss of hearing and/or vision, which results in difficulty communicating with their HCP.9 The loss of hearing or vision decreases the ability to adequately collaborate with HCPs and hampers an older adult’s ability to take the lead on self-management. As the U.S. population becomes more diverse, language also poses a significant barrier to care. A language barrier inherently affects health literacy about the disease as well as patients’ perceived trust in HCPs to manage their disease.3

Medication regimen. There are numerous barriers to taking medications. Polypharmacy is a common cause of more drug interactions and adverse effects, which are the most common reason for stopping medications.3,10 Cost of medications and difficulty keeping track of multiple medications are also a deterrent to self-management and adherence. Polypharmacy is seen as detrimental to quality of life (QOL).3 Some patients are also resistant to the initiation and titration of insulin.11

Lack of resources. Many patients cite a lack of resources to facilitate DM care. Common barriers include delays in being scheduled for medical appointments, lack of transportation to appointments, difficulty paying out-of-pocket copays, high cost of medications, and cost of DM supplies (eg, glucometers, test strips, insulin pens and/or pumps). The lack of access to community green spaces or gyms to increase physical activity is also a common barrier.12

Health Care Provider Experiences

Lack of motivation. Health care providers’ experiences and motivations can also present barriers to care. Some HCPs believe that evidence-based guidelines are simply theoretical frameworks; they disagree with using these guidelines as a basis to initiate statin therapy or antiglycemic medications, which reduce cardiovascular complications.13 Many also feel justified in taking a more lax approach when treating older adults due to a lack of time.13

Lack of education about DM management. Health care providers often feel less prepared to provide DM care and believe additional education in DM care is needed. Many lack formal postgraduate DM education or professional development, and 19.6% have no postgraduate DM education or training.14 Some are uncomfortable managing insulin because of a lack of knowledge of insulin therapy and its effect on cardiovascular risk. This results in patients remaining too long on oral DM medications and delaying the necessary initiation of insulin.13

Lack of resources. Some HCPs do not have qualified staff, such as dieticians and diabetes nurse educators, to support DM care. Fearing a loss of control over individual patient care, some HCPs also find it difficult to collaborate with multidisciplinary diabetes care team members, such as psychologists and diabetes educators.13 A lack of awareness of community programs hampers HCPs’ ability to get patients connected to resources that help them make lifestyle changes.14

Lack of involvement or empowerment. Health care providers often think patients do not act with a sense of empowerment in DM management. Health care providers commonly perceive patients as lacking the motivation to change and say that as many as 30% of patients are uncooperative, regardless of proposed changes.13 Many are convinced that patients are unwilling to make even small lifestyle adjustments, such as getting physically active and losing weight. Health care providers say patients do not ask questions about DM selfmanagement during visits and often do not verbalize how HCPs can best support their needs.15 They say that patients are so entrenched in their habits, they even refuse DM education.13

Management Strategies

Several strategies can be deployed to overcome barriers in DM care. Of utmost importance is the need to provide patient-centered care with age-specific characteristics of older adults (Table). To foster mutual collaboration in DM care, HCPs need to ask patients about their health care goals. Patients often view their health through a functional and social perspective rather than from a biomedical perspective. In one study, 71% of patients said their most common health goal was to be independent with activities of daily living, which was more important than the specific details of DM care.16 Preventing DM complications was among their secondary health care goals.

A DM care plan for older adults should be individualized with careful consideration given to medical history, functional capacity, home care environment, and life expectancy. Many older adults have health problems, such as impaired vision, cognitive impairment, depression, and peripheral sensory neuropathy. They may have osteoarthritis of the knees, osteoporosis of the hip and spine, or urinary incontinence; all these conditions increase the risk for falls. Many older adults are on multiple medications, which can increase falls by causing dizziness, dehydration, or hypotension.17 Polypharmacy can negatively impact one or more comorbid conditions and QOL.18

The clinical guidelines for DM management are based on studies conducted in younger populations. However, the 2015 guidelines from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) have been tailored to consider level of health, frailty, cognition, comorbidities, and life expectancy of older adults. The 2015 ADA recommendations provide a framework to guide treatment goals in older adults. A reasonable goal for healthy older adults with few chronic diseases, intact cognition, high functional status, and an anticipated longer remaining life expectancy is an A1c of < 7.5%.19 For older adults with comorbidities of intermediate complexity, such as mild cognitive impairment, an A1c treatment goal of < 8.0% is suggested. An A1c goal of < 8.5% is recommended for older adults in poor health, such as those with end-stage chronic disease, significant cognitive impairment, or those in long-term care. Health care providers may choose to further individualize A1c treatment goals to < 7% if patients are healthy and if treatment burdens are not severe or excessive.19

Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Chronic illness in older adults can be complex to manage due to competing comorbidities and polypharmacy. A diabetes care team consisting of a dietician, social worker, pharmacist, and certified diabetes educator is well suited to effectively manage DM in older adults. Up to 10 hours of DM education with a registered dietician or certified diabetes educator is covered under Medicare in a 12-month period if at least one of the following criteria are met: new diagnosis of DM with A1c > 8.5%, recent initiation of medication, or a high risk for complications.20

Motivational Interviewing

Many HCPs are frustrated that they are unable to persuade patients to adhere to their DM care recommendations. Health care providers often use strategies such as badgering or blaming patients for being nonadherent or scare tactics about the negative consequences of the disease.21 This approach is often ineffective and results in patients becoming more resistant to change.

Motivational interviewing using open-ended questions is an evidenced-based counseling technique that has been shown to elicit sustained behavioral changes. Motivational interviewing increases intrinsic motivation within patients and establishes a goal of incorporating patient-centered values into care by examining ambivalence and passivity in a nonjudgmental way.22 Motivational interviewing facilitates empowerment by using a decision-making process based on each individual’s unique physical, emotional, and environmental circumstances. With guidance from HCPs, patients are able to set the ground rules for DM management by defining a plan that works best for them. For example, a patient may consider a meal plan with stricter caloric intake vs one with a higher calorie count but with more frequent insulin injections or blood glucose monitoring. This strategy puts patients at the center of decision making about medications, diet, and exercise. It also allows them to implement an individualized plan that they believe will work best for them based on their own perceived goals, priorities, and stressors. This approach is shown to work effectively in DM care.8,23

Medication Regimen and Glucose Monitoring

Hypoglycemia is a major concern when managing DM in older adults.20 Hypoglycemia can be triggered by polypharmacy, cognitive impairment, renal insufficiency, sedatives, alcohol intake, malnutrition, and the use of sulfonylureas or insulin. Medications should be considered within the context of other geriatric problems such as falls, depression, urinary incontinence, and pain.20 A simplified approach based on the patient’s functional and cognitive abilities is a good starting point.20 Unless contraindicated, medication initiation could begin with a biguanide.1 Sulfonylureas should generally be avoided in older adults due to the high risk of hypoglycemia.1 Older adults with frequent hypoglycemia should be referred to an endocrinologist or diabetes educator for further management.24

Insulin therapy is recommended if oral therapy alone is insufficient or fails.20 Insulin can be prescribed with adequate DM education and blood glucose monitoring. When prescribing insulin, HCPs should consider older patients’ physical dexterity, visual acuity, cognitive function, financial circumstances, and family support to determine whether insulin therapy is a realistic option that patients can appropriately manage.12,20

Many older adults are resistant to starting insulin and are often reluctant to titrate insulin doses between clinic visits as prescribed by HCPs.12 Older adults on insulin need reassurance and education from a diabetes educator or HCP to gain confidence in adjusting insulin.12 A simple approach to starting insulin can be to start with an evening dose of long-acting insulin.20 Short-acting agents can be added later as needed to control postprandial hyperglycemia.20 Prefilled insulin flex pens also provide a quick and easy way to administer insulin in precise doses.20

Barriers to self-monitoring of blood glucose include pain from finger sticks, inconvenience of testing, and the expense of test strips.25 The newer glucometers and test strips use smaller amounts of blood from other body parts such as the upper arm, calf, or thigh, and these glucometers are ideally suited for older adults.20

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle interventions, including weight loss and exercise, are the mainstay in glycemic control of diabetes. The Diabetes Prevention Program study found a group of patients on lifestyle intervention alone (weight loss goal of 7% and ≥ 150 minutes of weekly exercise) had a 58% lower prevalence of DM compared with a group of patients taking metformin, which had a 31% lower prevalence.26 When older adults were compared with younger persons, lifestyle interventions were more effective than was taking metformin. High-intensity resistance training with moderate weights and repetition lowered glycemic index and caused a 3-fold reduction in A1c in older patients.27,28

Case Management

Older adults may have difficulty getting in touch with HCPs through traditional automated telephone systems. Many have difficulty transmitting glucose monitoring log sheets to HCPs for medication adjustments, which can result in delayed interventions. Telephone visits initiated by a competent case manager can serve as a primary point of contact between HCPs and older adults to optimize treatment and effectively get patients to targeted goals.

Telemedicine is an important tool for monitoring older adults in their home. The technology includes installing a home telemedicine unit, which supports videoconferencing, exchanging messages with case managers, uploading blood glucose readings, and accessing DM educational materials. A study on medication adherence in older diabetic patients found increased adherence through telemonitoring.29 Telemedicine can quickly identify new or persistent barriers between clinic visits so interventions can be made.

A case manager can also facilitate family and social support to address issues such as infrequent glucose monitoring, infrequent medical appointments, caregiver stress, lack of transportation, and financial difficulties, all of which can adversely affect DM care for older adults. The use of a network of family and friends is a good tool for DM management. One study found that when family or friends attended clinic visits, patients were more motivated to understand, follow HCP advice, and find resolutions to difficult issues in DM care.30

Conclusion

Diabetes is a chronic illness with a high burden for older adults. It is important to understand the experiences of patients and HCPs that influence common diabetes barriers. In older adults, barriers should be evaluated in an age-specific context to devise practical interventions to overcome them. Individualizing therapies and empowering older adults prepares them to live confidently while maintaining a sense of control over their lives. A patientcentered collaboration between HCPs and older adults that incorporates a multidisciplinary team approach to resolve problems can improve patient outcomes.

Additional research is needed to identify methods that are most suitable and applicable to older adults. If new evidenced-based research can eliminate diabetes barriers and improve diabetes care in older adults, the consequential burden of diabetes is more likely to decline.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic disease that is commonly reported in older adults in primary care. Many adults aged > 65 years with DM have other chronic diseases that make management of their care more complex. Overseeing DM care in older adults while comanaging other chronic diseases is a challenge to health care providers (HCPs). The terms older adults and geriatric define persons aged ≥ 65 years.

Diabetes mellitus is growing at a rapid rate, and older adults are at higher risk. In 2012, about 29.1 million people in the U.S. (9.3%) were diagnosed with DM. Of that number, 11.2 million were aged ≥ 65 years. Additionally, 86 million adults had prediabetes when fasting blood glucose and A1c levels were reviewed. Also in 2012, more than 400,000 new cases (11.5 per 1,000 people) were diagnosed in the aged ≥ 65 years group.1-3 This age group is anticipated to double in 25 years, and the incidence of DM is projected to increase 3.2-fold.4 By 2050, 26.7 million older adults—55% of the older adult population—will have DM. As a result, HCPs are faced with treating escalating numbers of older adults with DM as the population ages.4

In 2012, the total cost of DM for the U.S. population was $245 billion: The direct cost of medical care was $176 billion, and the indirect costs in productivity, absenteeism, unemployment, disability, and premature death was nearly $69 billion.2 This is a significant burden in terms of health care costs, productivity, disability, sick days, early retirement, and premature death. Diabetes mellitus increases atherosclerosis and thus accelerates the risk for heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, blindness, and limb amputations.2

Managing DM concurrently with multiple chronic comorbid conditions is challenging. Patients are asked to bring blood glucose under tight control, perform regular blood glucose testing, take antiglycemic medications, watch their diet, lose weight, and exercise regularly—all while managing other chronic diseases. Many older patients are overwhelmed by the demands of self-management recommended by their HCPs. Similarly, HCPs are frustrated with their older patients, who are unable to adequately meet targeted goals for DM management and thereby reduce the associated risks for complications.

The purpose of this article is to discuss the common barriers to DM management, the experiences of patients and HCPs regarding those barriers, and the management strategies for overcoming barriers in treating older adults with DM.

What Are The Barriers?

The experiences of both patients and HCPs matter when working to overcome DM barriers. If no one understands the problem, no one can fix it. What concerns do patients and HCPs have? Do they really value each other’s perspectives? To overcome barriers, can HCPs and patients develop mutually agreed on goals that are reasonable and practical to implement within the framework of a partnership?

Patient Experiences

Continuity of care and access. Some older adults are seen by multiple HCPs during health care visits, and as a result, they receive mixed messages on what is expected of them.3 Patients feel they have a greater sense of security and confidence when they have a therapeutic relationship with a trusted HCP; they feel more connected and confident about their health care system.5

Lack of education. Many patients say they need more DM education, guidance, and support.6 They report that HCPs tell them how to control DM to avoid complications but say they need more education on how DM affects their lives and concrete suggestions on how to change their lifestyles. Researchers say patients need to feel empowered so they can take a leadership role in managing medications, diet, exercise, preventive foot and eye care, and stress.7 In contrast, an empowerment approach identifies patients’ inherent capacity to self-direct and motivate themselves to develop a self-managed plan based on their personal goals and priorities.8 Patients want to be part of the solution.

Communication and language. A significant challenge for elderly patients is loss of hearing and/or vision, which results in difficulty communicating with their HCP.9 The loss of hearing or vision decreases the ability to adequately collaborate with HCPs and hampers an older adult’s ability to take the lead on self-management. As the U.S. population becomes more diverse, language also poses a significant barrier to care. A language barrier inherently affects health literacy about the disease as well as patients’ perceived trust in HCPs to manage their disease.3

Medication regimen. There are numerous barriers to taking medications. Polypharmacy is a common cause of more drug interactions and adverse effects, which are the most common reason for stopping medications.3,10 Cost of medications and difficulty keeping track of multiple medications are also a deterrent to self-management and adherence. Polypharmacy is seen as detrimental to quality of life (QOL).3 Some patients are also resistant to the initiation and titration of insulin.11

Lack of resources. Many patients cite a lack of resources to facilitate DM care. Common barriers include delays in being scheduled for medical appointments, lack of transportation to appointments, difficulty paying out-of-pocket copays, high cost of medications, and cost of DM supplies (eg, glucometers, test strips, insulin pens and/or pumps). The lack of access to community green spaces or gyms to increase physical activity is also a common barrier.12

Health Care Provider Experiences

Lack of motivation. Health care providers’ experiences and motivations can also present barriers to care. Some HCPs believe that evidence-based guidelines are simply theoretical frameworks; they disagree with using these guidelines as a basis to initiate statin therapy or antiglycemic medications, which reduce cardiovascular complications.13 Many also feel justified in taking a more lax approach when treating older adults due to a lack of time.13

Lack of education about DM management. Health care providers often feel less prepared to provide DM care and believe additional education in DM care is needed. Many lack formal postgraduate DM education or professional development, and 19.6% have no postgraduate DM education or training.14 Some are uncomfortable managing insulin because of a lack of knowledge of insulin therapy and its effect on cardiovascular risk. This results in patients remaining too long on oral DM medications and delaying the necessary initiation of insulin.13

Lack of resources. Some HCPs do not have qualified staff, such as dieticians and diabetes nurse educators, to support DM care. Fearing a loss of control over individual patient care, some HCPs also find it difficult to collaborate with multidisciplinary diabetes care team members, such as psychologists and diabetes educators.13 A lack of awareness of community programs hampers HCPs’ ability to get patients connected to resources that help them make lifestyle changes.14

Lack of involvement or empowerment. Health care providers often think patients do not act with a sense of empowerment in DM management. Health care providers commonly perceive patients as lacking the motivation to change and say that as many as 30% of patients are uncooperative, regardless of proposed changes.13 Many are convinced that patients are unwilling to make even small lifestyle adjustments, such as getting physically active and losing weight. Health care providers say patients do not ask questions about DM selfmanagement during visits and often do not verbalize how HCPs can best support their needs.15 They say that patients are so entrenched in their habits, they even refuse DM education.13

Management Strategies

Several strategies can be deployed to overcome barriers in DM care. Of utmost importance is the need to provide patient-centered care with age-specific characteristics of older adults (Table). To foster mutual collaboration in DM care, HCPs need to ask patients about their health care goals. Patients often view their health through a functional and social perspective rather than from a biomedical perspective. In one study, 71% of patients said their most common health goal was to be independent with activities of daily living, which was more important than the specific details of DM care.16 Preventing DM complications was among their secondary health care goals.

A DM care plan for older adults should be individualized with careful consideration given to medical history, functional capacity, home care environment, and life expectancy. Many older adults have health problems, such as impaired vision, cognitive impairment, depression, and peripheral sensory neuropathy. They may have osteoarthritis of the knees, osteoporosis of the hip and spine, or urinary incontinence; all these conditions increase the risk for falls. Many older adults are on multiple medications, which can increase falls by causing dizziness, dehydration, or hypotension.17 Polypharmacy can negatively impact one or more comorbid conditions and QOL.18

The clinical guidelines for DM management are based on studies conducted in younger populations. However, the 2015 guidelines from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) have been tailored to consider level of health, frailty, cognition, comorbidities, and life expectancy of older adults. The 2015 ADA recommendations provide a framework to guide treatment goals in older adults. A reasonable goal for healthy older adults with few chronic diseases, intact cognition, high functional status, and an anticipated longer remaining life expectancy is an A1c of < 7.5%.19 For older adults with comorbidities of intermediate complexity, such as mild cognitive impairment, an A1c treatment goal of < 8.0% is suggested. An A1c goal of < 8.5% is recommended for older adults in poor health, such as those with end-stage chronic disease, significant cognitive impairment, or those in long-term care. Health care providers may choose to further individualize A1c treatment goals to < 7% if patients are healthy and if treatment burdens are not severe or excessive.19

Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Chronic illness in older adults can be complex to manage due to competing comorbidities and polypharmacy. A diabetes care team consisting of a dietician, social worker, pharmacist, and certified diabetes educator is well suited to effectively manage DM in older adults. Up to 10 hours of DM education with a registered dietician or certified diabetes educator is covered under Medicare in a 12-month period if at least one of the following criteria are met: new diagnosis of DM with A1c > 8.5%, recent initiation of medication, or a high risk for complications.20

Motivational Interviewing

Many HCPs are frustrated that they are unable to persuade patients to adhere to their DM care recommendations. Health care providers often use strategies such as badgering or blaming patients for being nonadherent or scare tactics about the negative consequences of the disease.21 This approach is often ineffective and results in patients becoming more resistant to change.

Motivational interviewing using open-ended questions is an evidenced-based counseling technique that has been shown to elicit sustained behavioral changes. Motivational interviewing increases intrinsic motivation within patients and establishes a goal of incorporating patient-centered values into care by examining ambivalence and passivity in a nonjudgmental way.22 Motivational interviewing facilitates empowerment by using a decision-making process based on each individual’s unique physical, emotional, and environmental circumstances. With guidance from HCPs, patients are able to set the ground rules for DM management by defining a plan that works best for them. For example, a patient may consider a meal plan with stricter caloric intake vs one with a higher calorie count but with more frequent insulin injections or blood glucose monitoring. This strategy puts patients at the center of decision making about medications, diet, and exercise. It also allows them to implement an individualized plan that they believe will work best for them based on their own perceived goals, priorities, and stressors. This approach is shown to work effectively in DM care.8,23

Medication Regimen and Glucose Monitoring

Hypoglycemia is a major concern when managing DM in older adults.20 Hypoglycemia can be triggered by polypharmacy, cognitive impairment, renal insufficiency, sedatives, alcohol intake, malnutrition, and the use of sulfonylureas or insulin. Medications should be considered within the context of other geriatric problems such as falls, depression, urinary incontinence, and pain.20 A simplified approach based on the patient’s functional and cognitive abilities is a good starting point.20 Unless contraindicated, medication initiation could begin with a biguanide.1 Sulfonylureas should generally be avoided in older adults due to the high risk of hypoglycemia.1 Older adults with frequent hypoglycemia should be referred to an endocrinologist or diabetes educator for further management.24

Insulin therapy is recommended if oral therapy alone is insufficient or fails.20 Insulin can be prescribed with adequate DM education and blood glucose monitoring. When prescribing insulin, HCPs should consider older patients’ physical dexterity, visual acuity, cognitive function, financial circumstances, and family support to determine whether insulin therapy is a realistic option that patients can appropriately manage.12,20

Many older adults are resistant to starting insulin and are often reluctant to titrate insulin doses between clinic visits as prescribed by HCPs.12 Older adults on insulin need reassurance and education from a diabetes educator or HCP to gain confidence in adjusting insulin.12 A simple approach to starting insulin can be to start with an evening dose of long-acting insulin.20 Short-acting agents can be added later as needed to control postprandial hyperglycemia.20 Prefilled insulin flex pens also provide a quick and easy way to administer insulin in precise doses.20

Barriers to self-monitoring of blood glucose include pain from finger sticks, inconvenience of testing, and the expense of test strips.25 The newer glucometers and test strips use smaller amounts of blood from other body parts such as the upper arm, calf, or thigh, and these glucometers are ideally suited for older adults.20

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle interventions, including weight loss and exercise, are the mainstay in glycemic control of diabetes. The Diabetes Prevention Program study found a group of patients on lifestyle intervention alone (weight loss goal of 7% and ≥ 150 minutes of weekly exercise) had a 58% lower prevalence of DM compared with a group of patients taking metformin, which had a 31% lower prevalence.26 When older adults were compared with younger persons, lifestyle interventions were more effective than was taking metformin. High-intensity resistance training with moderate weights and repetition lowered glycemic index and caused a 3-fold reduction in A1c in older patients.27,28

Case Management

Older adults may have difficulty getting in touch with HCPs through traditional automated telephone systems. Many have difficulty transmitting glucose monitoring log sheets to HCPs for medication adjustments, which can result in delayed interventions. Telephone visits initiated by a competent case manager can serve as a primary point of contact between HCPs and older adults to optimize treatment and effectively get patients to targeted goals.

Telemedicine is an important tool for monitoring older adults in their home. The technology includes installing a home telemedicine unit, which supports videoconferencing, exchanging messages with case managers, uploading blood glucose readings, and accessing DM educational materials. A study on medication adherence in older diabetic patients found increased adherence through telemonitoring.29 Telemedicine can quickly identify new or persistent barriers between clinic visits so interventions can be made.

A case manager can also facilitate family and social support to address issues such as infrequent glucose monitoring, infrequent medical appointments, caregiver stress, lack of transportation, and financial difficulties, all of which can adversely affect DM care for older adults. The use of a network of family and friends is a good tool for DM management. One study found that when family or friends attended clinic visits, patients were more motivated to understand, follow HCP advice, and find resolutions to difficult issues in DM care.30

Conclusion

Diabetes is a chronic illness with a high burden for older adults. It is important to understand the experiences of patients and HCPs that influence common diabetes barriers. In older adults, barriers should be evaluated in an age-specific context to devise practical interventions to overcome them. Individualizing therapies and empowering older adults prepares them to live confidently while maintaining a sense of control over their lives. A patientcentered collaboration between HCPs and older adults that incorporates a multidisciplinary team approach to resolve problems can improve patient outcomes.

Additional research is needed to identify methods that are most suitable and applicable to older adults. If new evidenced-based research can eliminate diabetes barriers and improve diabetes care in older adults, the consequential burden of diabetes is more likely to decline.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Care of Older Adults With Diabetes Mellitus; Moreno G, Mangione CM, Kimbro L, Vaisberg E. Guidelines abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for Improving the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 Update. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):2020-2026.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

3. Williams A, Manias E. Exploring motivation and confidence in taking prescribed medicines in coexisting diseases: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(3-4):471-481.

4. Narayan KMV, Boyle JP, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB, Thompson TJ. Impact of recent

increase in incidence on future diabetes burden: U.S., 2005-2050. Diabetes Care.

2006;29(9):2114-2116.

5. von Bültzingslöwen I, Eliasson G, Sarvimäki A, Mattsson B, Hjortdahl P. Patients’ views on interpersonal continuity in primary care: a sense of security based on four core foundations. Fam Pract. 2006;23(2):210-219.

6. Koenigsberg MR, Bartlett D, Cramer JS. Facilitating treatment adherence with lifestyle changes in diabetes. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(2):309-316.

7. Mensing C, Boucher J, Cypress M, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Task Force to Review and Revise the National Standards for Diabetes Self-Management Education Programs. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(5):682-689.

8. Funnell MM, Weiss MA. Empowering patients with diabetes. Nursing. 2009;39(3):34-37.

9. Hammouda EI. Overcoming barriers to diabetes control in geriatrics. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(4):420-424.

10. Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2650-2664.

11. Brod M, Kongsø JH, Lessard S, Christensen TL. Psychological insulin resistance: patient beliefs and implications for diabetes management. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):23-32.

12. Munshi MN, Segal AR, Suhl E, et al. Assessment of barriers to improve diabetes management in older adults: a randomized controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(3):543-549.

13. Goderis G, Borgermans L, Mathieu C, et al. Barriers and facilitators to evidence based care of type 2 diabetes patients: experiences of general practitioners participating to a quality improvement program. Implement Sci. 2009;4:41.

14. Raaijmakers LGM, Hamers FJM, Martens MK, Bagchus C, de Vries NK, Kremers SPJ. Perceived facilitators and barriers in diabetes care: a qualitative study among health care professionals in the Netherlands. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14(1):114.

15. Holt RIG, Nicolucci A, Kovacs Burns K, et al; DAWN2 Study Group. Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs second study (DAWN2™): cross-national comparisons on barriers and resources for optimal care—healthcare professional perspective. Diabet Med. 2013;30(7):789-798.

16. Huang ES, Gorawara-Bhat R, Chin MH. Self-reported goals of older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):306-311.

17. Haas LB. Special considerations for older adults with diabetes residing in skilled nursing facilities. Diabetes Spectrum. 2014;27(1):37-43.

18. Mason NA, Bakus JL. Strategies for reducing polypharmacy and other medicationrelated problems in chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial. 2010;23(1):55-61.

19. American Diabetes Association. Older adults. Sec.10. In Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(suppl 1):S67-S69.

20. Hornick T, Aron DC. Managing diabetes in the elderly: go easy, individualize. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(1):70-78.

21. Gabbay RA, Durdock K. Strategies to increase adherence through diabetes technology. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(3):661-665.

22. Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008.

23. West D, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, Greene PG. Motivational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1081-1087.

24. Graber AL, Elasy TA, Quinn D, Wolff K, Brown A. Improving glycemic control in adults with diabetes mellitus: shared responsibility in primary care practices. South Med J. 2002;95(7):684-690.

25. Zgibor JC, Simmons D. Barriers to blood glucose monitoring in a multiethnic community. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1772-1777.

26. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393-403.

27. Witham MD, Avenell A. Interventions to achieve long-term weight loss in obese older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2010;39(2):176-184.

28. Dunstan DW, Daly RM, Owen N, et al. High-intensity resistance training improves glycemic control in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1729-1736.

29. Brath H, Morak J, Kästenbauer T, et al. Mobile health (mHealth) based medication adherence measurement–a pilot trial using electronic blisters in diabetes patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(suppl 1):47-55.

30. Rosland AM, Piette JD, Choi H, Heisler M. Family and friend participation in primary care visits of patients with diabetes or heart failure: patient and physician determinants and experiences. Med Care. 2011;49(1):37-45.

1. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Care of Older Adults With Diabetes Mellitus; Moreno G, Mangione CM, Kimbro L, Vaisberg E. Guidelines abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for Improving the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 Update. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):2020-2026.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

3. Williams A, Manias E. Exploring motivation and confidence in taking prescribed medicines in coexisting diseases: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(3-4):471-481.

4. Narayan KMV, Boyle JP, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB, Thompson TJ. Impact of recent

increase in incidence on future diabetes burden: U.S., 2005-2050. Diabetes Care.

2006;29(9):2114-2116.

5. von Bültzingslöwen I, Eliasson G, Sarvimäki A, Mattsson B, Hjortdahl P. Patients’ views on interpersonal continuity in primary care: a sense of security based on four core foundations. Fam Pract. 2006;23(2):210-219.

6. Koenigsberg MR, Bartlett D, Cramer JS. Facilitating treatment adherence with lifestyle changes in diabetes. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(2):309-316.

7. Mensing C, Boucher J, Cypress M, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Task Force to Review and Revise the National Standards for Diabetes Self-Management Education Programs. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(5):682-689.

8. Funnell MM, Weiss MA. Empowering patients with diabetes. Nursing. 2009;39(3):34-37.

9. Hammouda EI. Overcoming barriers to diabetes control in geriatrics. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(4):420-424.

10. Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2650-2664.

11. Brod M, Kongsø JH, Lessard S, Christensen TL. Psychological insulin resistance: patient beliefs and implications for diabetes management. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):23-32.

12. Munshi MN, Segal AR, Suhl E, et al. Assessment of barriers to improve diabetes management in older adults: a randomized controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(3):543-549.

13. Goderis G, Borgermans L, Mathieu C, et al. Barriers and facilitators to evidence based care of type 2 diabetes patients: experiences of general practitioners participating to a quality improvement program. Implement Sci. 2009;4:41.

14. Raaijmakers LGM, Hamers FJM, Martens MK, Bagchus C, de Vries NK, Kremers SPJ. Perceived facilitators and barriers in diabetes care: a qualitative study among health care professionals in the Netherlands. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14(1):114.

15. Holt RIG, Nicolucci A, Kovacs Burns K, et al; DAWN2 Study Group. Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs second study (DAWN2™): cross-national comparisons on barriers and resources for optimal care—healthcare professional perspective. Diabet Med. 2013;30(7):789-798.

16. Huang ES, Gorawara-Bhat R, Chin MH. Self-reported goals of older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):306-311.

17. Haas LB. Special considerations for older adults with diabetes residing in skilled nursing facilities. Diabetes Spectrum. 2014;27(1):37-43.

18. Mason NA, Bakus JL. Strategies for reducing polypharmacy and other medicationrelated problems in chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial. 2010;23(1):55-61.

19. American Diabetes Association. Older adults. Sec.10. In Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(suppl 1):S67-S69.

20. Hornick T, Aron DC. Managing diabetes in the elderly: go easy, individualize. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(1):70-78.

21. Gabbay RA, Durdock K. Strategies to increase adherence through diabetes technology. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(3):661-665.

22. Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008.

23. West D, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, Greene PG. Motivational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1081-1087.

24. Graber AL, Elasy TA, Quinn D, Wolff K, Brown A. Improving glycemic control in adults with diabetes mellitus: shared responsibility in primary care practices. South Med J. 2002;95(7):684-690.

25. Zgibor JC, Simmons D. Barriers to blood glucose monitoring in a multiethnic community. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1772-1777.

26. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393-403.

27. Witham MD, Avenell A. Interventions to achieve long-term weight loss in obese older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2010;39(2):176-184.

28. Dunstan DW, Daly RM, Owen N, et al. High-intensity resistance training improves glycemic control in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1729-1736.

29. Brath H, Morak J, Kästenbauer T, et al. Mobile health (mHealth) based medication adherence measurement–a pilot trial using electronic blisters in diabetes patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(suppl 1):47-55.

30. Rosland AM, Piette JD, Choi H, Heisler M. Family and friend participation in primary care visits of patients with diabetes or heart failure: patient and physician determinants and experiences. Med Care. 2011;49(1):37-45.