User login

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

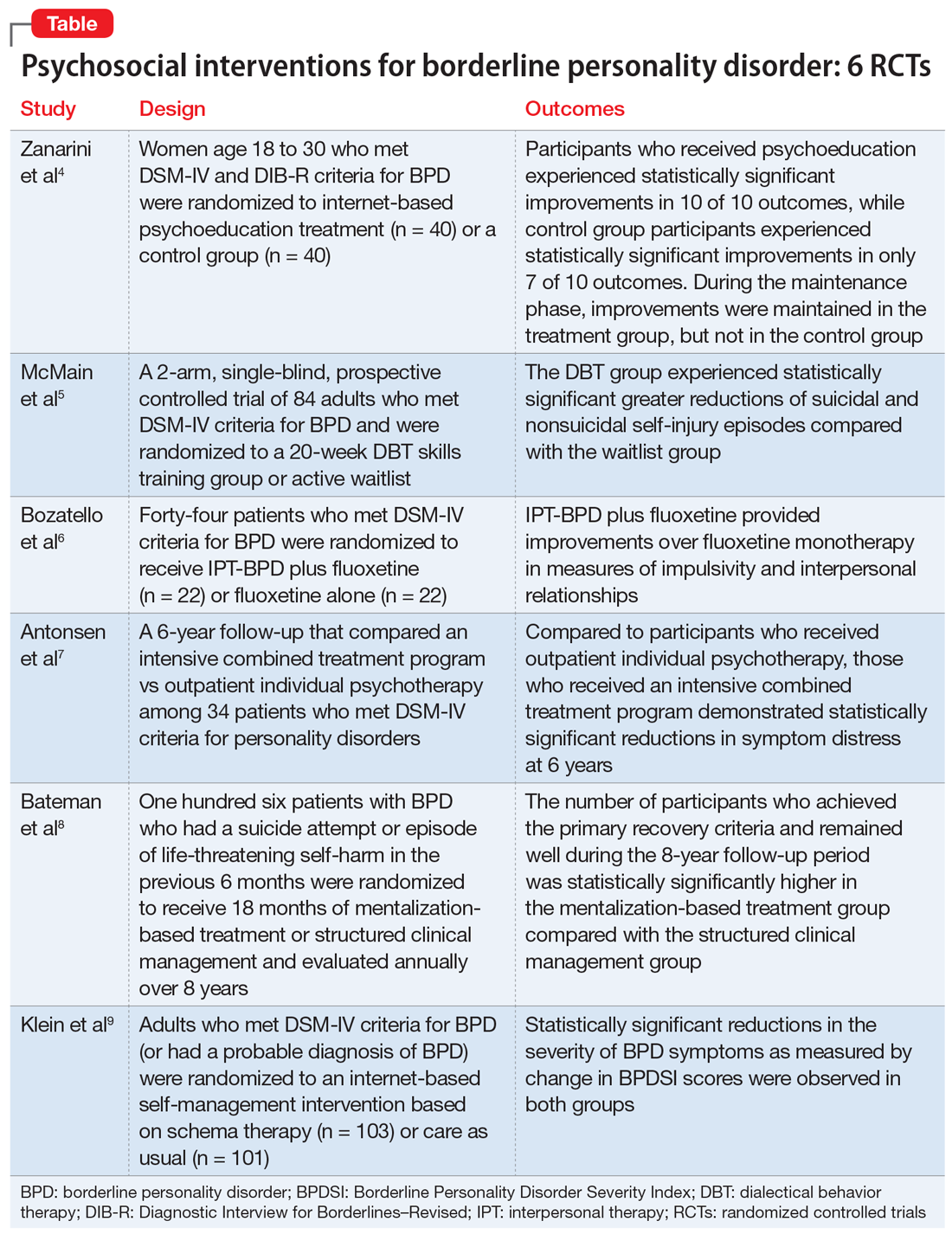

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 It is characterized by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior that often results in problems in relationships. As a result, patients with BPD tend to utilize more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or major depressive disorder.2

Some clinicians believe BPD is difficult to treat. While historically there has been little consensus on the best treatments for this disorder, current options include both pharmacologic and psychological interventions. In Part 1 of this 2-part article, we focused on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions.3 Here in Part 2, we focus on findings from 6 recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychosocial interventions for BPD

1. Zanarini MC, Conkey LC, Temes CM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of web-based psychoeducation for women with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3):16m11153. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11153

Research has shown that BPD is a treatable illness with a more favorable prognosis than previously believed. Despite this, patients often experience difficulty accessing the most up-to-date information on BPD, which can impede their treatment. A 2008 study by Zanarini et al10 of younger female patients with BPD demonstrated that immediate, in-person psychoeducation improved impulsivity and relationships. Widespread implementation of this program proved problematic, however, due to cost and personnel constraints. To resolve this issue, researchers developed an internet-based version of the program. In a 2018 follow-up study, Zanarini et al4 examined the effect of this internet-based psychoeducation program on symptoms of BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- Women (age 18 to 30) who met DSM-IV and Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines–Revised criteria for BPD were randomized to an internet-based psychoeducation treatment group (n = 40) or a control group (n = 40).

- Ten outcomes concerning symptom severity and psychosocial functioning were assessed during weeks 1 to 12 (acute phase) and at months 6, 9, and 12 (maintenance phase) using the self-report version of the Zanarini Rating Scale for BPD (ZAN-BPD), the Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time, the Sheehan Disability Scale, the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale, the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale, and Weissman’s Social Adjustment Scale (SAS).

Outcomes

- In the acute phase, treatment group participants experienced statistically significant improvements in all 10 outcomes. Control group participants demonstrated similar results, achieving statistically significant improvements in 7 of 10 outcomes.

- Compared to the control group, the treatment group experienced a more significant reduction in impulsivity and improvement in psychosocial functioning as measured by the ZAN-BPD and SAS.

- In the maintenance phase, treatment group participants achieved statistically significant improvements in 9 of 10 outcomes, whereas control group participants demonstrated statistically significant improvements in only 3 of 10 outcomes.

- Compared to the control group, the treatment group also demonstrated a significantly greater improvement in all 4 sector scores and the total score of the ZAN-BP

Conclusions/limitations

- In patients with BPD, internet-based psychoeducation reduced symptom severity and improved psychosocial functioning, with effects lasting 1 year. Treatment group participants experienced clinically significant improvements in all outcomes measured during the acute phase of the study; most improvements were maintained over 1 year.

- While the control group initially saw similar improvements in most measurements, these improvements were not maintained as effectively over 1 year.

- Limitations include a female-only population, the restricted age range of participants, and recruitment exclusively from volunteers.

2. McMain SF, Guimond T, Barnhart R, et al. A randomized trial of brief dialectical behaviour therapy skills training in suicidal patients suffering from borderline disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(2):138-148.

Standard dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an effective treatment for BPD; however, access is often limited by shortages of clinicians and resources. Therefore, it has become increasingly common for clinical settings to offer patients only the skills training component of DBT, which requires fewer resources. While several clinical trials examining brief DBT skills–only treatment for BPD have shown promising results, it is unclear how effective this intervention is at reducing suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) episodes. McMain et al5 explored the effectiveness of brief DBT skills–only adjunctive treatment on the rates of suicidal and NSSI episodes in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In this 2-arm, single-blind, prospective controlled trial, 84 adults who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to a 20-week DBT skills training group (DBT group) or an active waitlist (WL group). No restrictions on additional psychosocial or pharmacologic treatments were imposed on either group.

- The primary outcome was the frequency of suicidal and NSSI episodes as measured by the Lifetime Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview and the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI). Measurements occurred at baseline, 10 weeks, 20 weeks, and 3 months posttreatment (32 weeks).

- Secondary outcomes included changes in health care utilization, BPD symptoms, and coping. These were assessed using the Treatment History Interview-2, Borderline Symptom List-23, State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory, Symptom Checklist-90-revised (SCL-90-R), Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)-II, Social Adjustment Scale Self-report, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, Distress Tolerance Scale, and Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Scale.

Outcomes

- At Week 32, compared to the WL group, the DBT group showed statistically significant greater reductions in the frequency of suicidal and NSSI episodes as measured by the LSASI but not by the DSHI. The DBT group experienced statistically significant improvements in distress tolerance and emotion regulation over the WL group at all points, but no difference on mindfulness. The DBT group achieved greater reductions in anger over time as compared to the WL group.

- At Week 20, compared to the WL group, the DBT group showed significant improvements in social adjustment, symptom distress, and borderline symptoms. There were no significant group differences on impulsivity. Between-group differences in the number of hospital admissions favored the DBT group at 10 and 20 weeks, but not at 32 weeks. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups with respect to the number of emergency department visits.

- Analyses of group differences in clinical improvement as measured by the SCL-90-R revealed statistically reliable and clinically significant changes in the DBT group over the WL group at 20 weeks, but not at 32 weeks.

Conclusions/limitations

- Brief DBT skills training reduced suicidal and NSSI episodes in patients with BPD. Participants in the DBT group also demonstrated greater improvement in anger, distress tolerance, and emotion regulation compared to the control group. These results were evident 3 months after treatment. However, any gains in health care utilization, social adjustment, symptom distress, and borderline symptoms diminished or did not differ from waitlist participants at Week 32. At that time, participants in the DBT group demonstrated a similar level of symptomatology as the WL group.

- Limitations include the use of an active waitlist control group, allowance of concurrent treatments, the absence of an active therapeutic comparator group, use of self-report measures, use of an instrument with unknown psychometric properties, and a relatively short 3-month follow-up period.

3. Bozzatello P, Bellino S. Combined therapy with interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for borderline personality disorder: a two-years follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:151-156.

Psychotherapeutic options for treating BPD include DBT, mentalization-based treatment, schema-focused therapy, transference-based psychotherapy, and systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving. More recently, interpersonal therapy also has been adapted for BPD (IPT-BPD). However, thus far no trials have investigated the long-term effects of this therapy on BPD. In 2010, Bellino et al11 published a 32-week RCT examining the effect of IPT-BPD on BPD. They concluded that IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine was superior to fluoxetine alone in improving symptoms and quality of life. The present study by Bozzatello et al6 examined whether the benefits of IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine demonstrated in the 2010 study persisted over a 24-month follow-up.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In the 2010 study by Bellino et al,11 55 outpatients who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to receive IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine (combined therapy) or fluoxetine alone for 32 weeks. Forty-four participants completed a 24-month follow-up study (n = 22 for IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine, n = 22 for fluoxetine only).

- Clinical assessments were performed at 6, 12, and 24 months, and used the same instruments as the original study, including the Clinical Global Impression Scale–Severity item, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS), Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment, Satisfaction Profile (SAT-P), and the Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index (BPDSI).

Outcomes

- While the original study demonstrated that combined therapy had a clinically significant effect over fluoxetine alone on both HARS score and the BPDSI item “affective instability” at 32 weeks, this advantage was maintained only at the 6-month assessment.

- The improvements that the combined therapy provided over fluoxetine monotherapy on the BPDSI items of “impulsivity” and “interpersonal relationships” as well as the SAT-P factors of social and psychological functioning at 32 weeks were preserved at 24 months. No additional improvements were seen.

Conclusions/limitations

- The improvements in impulsivity, interpersonal functioning, social functioning, and psychological functioning at 32 weeks seen with IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine compared with fluoxetine alone persisted for 2 years after completing therapy; no further improvements were seen.

- The improvements to anxiety and affective instability that combined therapy demonstrated over fluoxetine monotherapy at 32 weeks were not maintained at 24 months.

- Limitations include a small sample size, exclusion of psychiatric comorbidities, and a lack of assessment of session or medication adherence.

4. Antonsen BT, Kvarstein EH, Urnes Ø, et al. Favourable outcome of long-term combined psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder: six-year follow-up of a randomized study. Psychother Res. 2017;27(1):51-63.

While many studies have demonstrated the benefits of psychotherapy for treating personality disorders, there is limited research of how different levels of psychotherapy may impact treatment outcomes. An RCT called the Ullevål Personality Project (UPP)12 compared an intensive combined treatment program (CP) with outpatient individual psychotherapy (OIP) in patients with personality disorders. The CP program consisted of short-term day-hospital treatment followed by outpatient combined group and individual psychotherapy. The outcomes this RCT evaluated included suicide attempts, suicidal thoughts, self-injury, psychosocial functioning, symptom distress, and interpersonal and personality problems. A 6-year follow-up concluded there were no differences in outcomes between the 2 treatment groups. However, in this RCT, Antonsen et al7 examined whether CP produced statistically significant benefits over OIP in a subset of patients with BPD.

Study design

- In the UPP trial,12 117 patients who met DSM-IV criteria for personality disorders (excluding antisocial and schizotypal personality disorder) were randomized to receive 18 weeks of day hospital psychotherapy followed by CP or OIP. Fifty-two participants in the UPP were diagnosed with BPD, and 34 of these participants completed the 6-year follow-up investigation.

- Symptom distress, psychosocial functioning, interpersonal problems, quality of life, personality functioning, and self-harm/suicidal thoughts/suicide attempts were assessed at baseline, 8 months, 18 months, 3 years, and 6 years using the SCL-90-R Global Severity Index (GSI), BDI, Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS), Quality of Life 10-point scale (QOL), Circumplex of Interpersonal Problems (CIP), and the 60-item short form of the Severity Indices of Personality Problems (SIPP-118) questionnaire.

Outcomes

- Compared to the OIP group, the CP group demonstrated statistically significant reductions in symptom distress at Year 6 as measured by the SCL-90-R GSI. Between Years 3 and 6, the CP group continued to show improvements in psychosocial functioning as demonstrated by improvements in GAF and WSAS scores. The OIP group’s scores worsened during this time. Compared to the OIP group, participants in the CP group also had significantly better outcomes on the SIPP-118 domains of self-control and identity integration.

- There were no significant differences between groups on the proportion of participants who engaged in self-harm or experienced suicidal thoughts or attempts. There were no significant differences in outcomes between the treatment groups on the CIP, BDI, or QOL.

- Participants in CP group tended to use fewer psychotropic medications than those in the OIP group over time, but this difference was not statistically significant. The 2 groups did not differ in use of health care services over the last year.

- Avoidant personality disorder (AVPD) did not have a significant moderator effect on GAF score. Comorbid AVPD was a negative predictor of GAF score, independent of the group.

Conclusions/limitations

- Both groups experienced a remission rate of 90% at 6-year follow-up. Compared with the OIP group, participants in the CP group experienced significantly greater reductions in symptom distress and improvements in self-control and identity integration at 6 years. Between Years 3 and 6, participants in the CP group experienced significant improvements in psychosocial functioning compared with OIP group participants. The 2 groups did not differ on other outcomes, including the CIP, BDI, QOL, suicidal thoughts, suicidal attempts, self-harm, and health care utilization.

- Despite statistically significant differences in GAF scores favoring the CP group over the OIP group during Years 3 to 6, GAF scores did not differ significantly in the final year, which suggests that symptomatic remission does not equal functional improvement.

- Limitations include a lack of control for intensity or length of treatment in statistical analyses, small sample size, lack of correction for multiple testing, lack of an a priori power analysis, missing data and potential violation of the missing at random assumption, use of therapists’ preferred treatment method/practice, and a lack of control for other treatments.

5. Bateman A, Constantinou MP, Fonagy P, et al. Eight-year prospective follow-up of mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for people with borderline personality disorder. Personal Disord. 2021;12(4):291-299.

The efficacy of various psychotherapies for symptoms of BPD has been well established. However, there is limited evidence that these effects persist over time. In 2009, Bateman et al13 conducted an 18-month RCT comparing the effectiveness of outpatient mentalization-based treatment (MBT) against structured clinical management (SCM) for patients with BPD. Both groups experienced substantial improvements, but patients assigned to MBT demonstrated greater improvement in clinically significant problems, including suicide attempts and hospitalizations. In a 2021 follow-up to this study, Bateman et al8 investigated whether the MBT group’s gains in the primary outcomes (absence of severe self-harm, suicide attempts, and inpatient admissions in the previous 12 months), social functioning, vocational engagement, and mental health service usage were maintained throughout an 8-year follow-up period.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In the 2009 trial, Bateman et al13 randomized adult participants who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD and had a suicide attempt or episode of life-threatening self-harm in the past 6 months to receive 18 months of MBT or SCM. The primary outcome was crisis events, defined as a composite of suicidal and severe self-injurious behaviors and hospitalizations. The 2021 Bateman et al8 study expanded this investigation by collecting additional data on a yearly basis for 8 years.

- Of the 134 original participants, 98 agreed to complete the follow-up. Due to attrition, the follow-up period was limited to 8 years. At each yearly visit, researchers collected information on the primary outcome, the absence of severe self-harm, suicide attempts, and inpatient admissions in the previous 12 months.

- Secondary measures were collected mainly through a modified version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory and included critical incidents, psychiatric and medical hospital and community services, employment and other personally meaningful activity, psychoactive medication, and other mental health treatments.

Outcomes

- The number of participants who met diagnostic criteria for BPD at the 1-year follow-up was significantly lower in the MBT group compared with the SCM group. To improve participant retention, this outcome was not evaluated at later visits.

- The number of participants who achieved the primary recovery criteria of the original trial (absence of severe self-harm, suicide attempts, and inpatient admissions in the previous 12 months) and remained well throughout the entire follow-up period was significantly higher in the MBT group compared with the SCM group. The average number of years during which participants failed to meet recovery criteria was significantly greater in the SCM group compared with the MBT group.

- When controlling for age, treatment group was a significant predictor of recovery during the follow-up period. Overall, significantly fewer participants in the MBT group experienced critical incidents during the follow-up period.

- The SCM group used crisis mental health services for a significantly greater number of follow-up years than the MBT group, although the likelihood of ever using crisis services did not statistically differ between the groups. Both groups had similar use of outpatient mental health services, primary care services, and nonmental health medical services. Compared to the SCM group, the MBT group had significantly fewer professional support service visits and significantly fewer outpatient psychiatrist visits.

- MBT group participants spent more time in education, were less likely to be unemployed, and were less likely to use social care interventions than SCM group participants. Although those in the MBT group spent more months engaged in purposeful activity, there was no significant difference between the groups in the proportion of participants who did not engage in purposeful activity.

- The MBT group spent fewer months receiving psychotherapeutic medication compared with the SCM group. The variables that yielded significant 2-way interactions were eating disorder, substance use disorder, and physical abuse, suggesting greater benefit from MBT with these concurrent diagnoses. Younger age was associated with better outcomes.

Conclusions/limitations

- This study demonstrated that patients with BPD significantly benefited from specialized therapies such as MBT.

- At the 1 follow-up visit, the number of participants who met diagnostic criteria for BPD was significantly lower in the MBT group compared with the SCM group.

- The number of participants who had achieved the primary recovery criteria and remained well during the 8-year follow-up period was significantly higher in the MBT group compared to the SCM group.

- Limitations include increasing attrition over time, possible allegiance effects and unmasking of research assistants, lack of self-report questionnaires, and the potentially erroneous conclusion that increased use of services equates to poorer treatment response and greater need for support.

6. Klein JP, Hauer-von Mauschwitz A, Berger T, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the adjunctive use of an internet-based self-management intervention for borderline personality disorder in addition to care as usual: results from a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e047771.

Fewer than 1 in 4 patients with BPD have access to effective psychotherapies. The use of internet-based self-management interventions (SMIs) developed from evidence-based psychotherapies can help close this treatment gap. Although the efficacy of SMIs for several mental disorders has been demonstrated in multiple meta-analyses, results for BPD are mixed. In this study, Klein et al9 examined the effectiveness and safety of the adjunctive use of an SMI based on schema therapy in addition to care as usual (CAU) in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In a 12-month, rater-blind, controlled parallel group trial, adults who had a total BPDSI score ≥15 and either a diagnosis of BPD according to DSM-IV criteria or a probable diagnosis of BPD (if they had also received a BPD diagnosis from their treating physician) were randomized to an internet-based SMI based on schema therapy called priovi (n = 103) or CAU (n = 101). Participants could complete the SMI content in approximately 6 months but were recommended to use the intervention for the entire year.

- Participation in psychotherapy and psychiatric treatment, including pharmacotherapy, was permitted. At baseline, 74% of participants were receiving psychotherapy and 88% were receiving psychiatric treatment.

- The primary outcome was change in BPDSI score at 12 months. The primary safety outcome was the number of serious adverse events at 12 months. Secondary outcomes included BPD severity, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, quality of life, uncontrolled internet use, negative treatment effects, and satisfaction with the intervention. Most assessments were measured at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months.

Outcomes

- Large reductions in the severity of BPD symptoms as measured by change in BPDSI score was observed in both groups. Although the average reduction in BPDSI score was greater in the SMI group, this difference was not statistically significant from the CAU group.

- There was no statistically significant difference in the number of serious adverse events between groups at any time.

Conclusions/limitations

- Treatment with SMI did not result in improved outcomes over CAU. Although the average reduction in BPDSI score was greater in the SMI group compared to the CAU group, this difference was not statistically significant.

- The authors cautioned that the smaller-than-expected between-groups effect size must be interpreted against the background of an unexpectedly large effect in the CAU group. In fact, the CAU group pre/post effect was comparable to the pre/post effect of intensive specialized DBT treatment groups in previous RCTs.

- The authors also suggested that the high percentage of participants who received psychotherapy did not allow for an additional benefit from SMI.

- Limitations include recruitment method, lack of systematic assessment of accidental unblinding, high exclusion rate due to failure of the participant or treating clinician to provide confirmation of diagnosis, and the use of a serious adverse events assessment that is not psychometrically validated.

Bottom Line

Evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that internet-based psychoeducation, brief dialectical behavior therapy skills-only treatment, interpersonal therapy, a program that combines day treatment with individual and group psychotherapy, and mentalization-based treatment can improve symptoms and quality of life for patients with borderline personality disorder.

1. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TM, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):276-83.

2. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):295-302.

3. Saeed SA, Kallis AC. Borderline personality disorder: 6 studies of biological interventions. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):26-30,34-36.

4. Zanarini MC, Conkey LC, Temes CM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of web-based psychoeducation for women with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3):16m11153. doi:10.4088/JCP.16m11153

5. McMain SF, Guimond T, Barnhart R, et al. A randomized trial of brief dialectical behaviour therapy skills training in suicidal patients suffering from borderline disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(2):138-148. doi:10.1111/acps.12664

6. Bozzatello P, Bellino S. Combined therapy with interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for borderline personality disorder: a two-years follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:151-156. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.014

7. Antonsen BT, Kvarstein EH, Urnes Ø, et al. Favourable outcome of long-term combined psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder: six-year follow-up of a randomized study. Psychother Res. 2017;27(1):51-63. doi:10.1080/10503307.2015.1072283

8. Bateman A, Constantinou MP, Fonagy P, et al. Eight-year prospective follow-up of mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for people with borderline personality disorder. Personal Disord. 2021;12(4):291-299. doi:10.1037/per0000422

9. Klein JP, Hauer-von Mauschwitz A, Berger T, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the adjunctive use of an internet-based self-management intervention for borderline personality disorder in addition to care as usual: results from a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e047771. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047771

10. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. A preliminary, randomized trial of psychoeducation for women with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2008;22(3):284-290.

11. Bellino S, Rinaldi C, Bogetto F. Adaptation of interpersonal psychotherapy to borderline personality disorder: a comparison of combined therapy and single pharmacotherapy. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(2):74-81.

12. Arnevik E, Wilberg T, Urnes Ø, et al. Psychotherapy for personality disorders: short-term day hospital psychotherapy versus outpatient individual therapy – a randomized controlled study. Eur Psychiatry. 2009,24(2):71-78. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.09.004

13. Bateman A, Fonagy P. Randomized controlled trial of outpatient mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(12):1355-1364.

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 It is characterized by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior that often results in problems in relationships. As a result, patients with BPD tend to utilize more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or major depressive disorder.2

Some clinicians believe BPD is difficult to treat. While historically there has been little consensus on the best treatments for this disorder, current options include both pharmacologic and psychological interventions. In Part 1 of this 2-part article, we focused on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions.3 Here in Part 2, we focus on findings from 6 recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychosocial interventions for BPD

1. Zanarini MC, Conkey LC, Temes CM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of web-based psychoeducation for women with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3):16m11153. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11153

Research has shown that BPD is a treatable illness with a more favorable prognosis than previously believed. Despite this, patients often experience difficulty accessing the most up-to-date information on BPD, which can impede their treatment. A 2008 study by Zanarini et al10 of younger female patients with BPD demonstrated that immediate, in-person psychoeducation improved impulsivity and relationships. Widespread implementation of this program proved problematic, however, due to cost and personnel constraints. To resolve this issue, researchers developed an internet-based version of the program. In a 2018 follow-up study, Zanarini et al4 examined the effect of this internet-based psychoeducation program on symptoms of BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- Women (age 18 to 30) who met DSM-IV and Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines–Revised criteria for BPD were randomized to an internet-based psychoeducation treatment group (n = 40) or a control group (n = 40).

- Ten outcomes concerning symptom severity and psychosocial functioning were assessed during weeks 1 to 12 (acute phase) and at months 6, 9, and 12 (maintenance phase) using the self-report version of the Zanarini Rating Scale for BPD (ZAN-BPD), the Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time, the Sheehan Disability Scale, the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale, the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale, and Weissman’s Social Adjustment Scale (SAS).

Outcomes

- In the acute phase, treatment group participants experienced statistically significant improvements in all 10 outcomes. Control group participants demonstrated similar results, achieving statistically significant improvements in 7 of 10 outcomes.

- Compared to the control group, the treatment group experienced a more significant reduction in impulsivity and improvement in psychosocial functioning as measured by the ZAN-BPD and SAS.

- In the maintenance phase, treatment group participants achieved statistically significant improvements in 9 of 10 outcomes, whereas control group participants demonstrated statistically significant improvements in only 3 of 10 outcomes.

- Compared to the control group, the treatment group also demonstrated a significantly greater improvement in all 4 sector scores and the total score of the ZAN-BP

Conclusions/limitations

- In patients with BPD, internet-based psychoeducation reduced symptom severity and improved psychosocial functioning, with effects lasting 1 year. Treatment group participants experienced clinically significant improvements in all outcomes measured during the acute phase of the study; most improvements were maintained over 1 year.

- While the control group initially saw similar improvements in most measurements, these improvements were not maintained as effectively over 1 year.

- Limitations include a female-only population, the restricted age range of participants, and recruitment exclusively from volunteers.

2. McMain SF, Guimond T, Barnhart R, et al. A randomized trial of brief dialectical behaviour therapy skills training in suicidal patients suffering from borderline disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(2):138-148.

Standard dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an effective treatment for BPD; however, access is often limited by shortages of clinicians and resources. Therefore, it has become increasingly common for clinical settings to offer patients only the skills training component of DBT, which requires fewer resources. While several clinical trials examining brief DBT skills–only treatment for BPD have shown promising results, it is unclear how effective this intervention is at reducing suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) episodes. McMain et al5 explored the effectiveness of brief DBT skills–only adjunctive treatment on the rates of suicidal and NSSI episodes in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In this 2-arm, single-blind, prospective controlled trial, 84 adults who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to a 20-week DBT skills training group (DBT group) or an active waitlist (WL group). No restrictions on additional psychosocial or pharmacologic treatments were imposed on either group.

- The primary outcome was the frequency of suicidal and NSSI episodes as measured by the Lifetime Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview and the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI). Measurements occurred at baseline, 10 weeks, 20 weeks, and 3 months posttreatment (32 weeks).

- Secondary outcomes included changes in health care utilization, BPD symptoms, and coping. These were assessed using the Treatment History Interview-2, Borderline Symptom List-23, State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory, Symptom Checklist-90-revised (SCL-90-R), Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)-II, Social Adjustment Scale Self-report, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, Distress Tolerance Scale, and Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Scale.

Outcomes

- At Week 32, compared to the WL group, the DBT group showed statistically significant greater reductions in the frequency of suicidal and NSSI episodes as measured by the LSASI but not by the DSHI. The DBT group experienced statistically significant improvements in distress tolerance and emotion regulation over the WL group at all points, but no difference on mindfulness. The DBT group achieved greater reductions in anger over time as compared to the WL group.

- At Week 20, compared to the WL group, the DBT group showed significant improvements in social adjustment, symptom distress, and borderline symptoms. There were no significant group differences on impulsivity. Between-group differences in the number of hospital admissions favored the DBT group at 10 and 20 weeks, but not at 32 weeks. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups with respect to the number of emergency department visits.

- Analyses of group differences in clinical improvement as measured by the SCL-90-R revealed statistically reliable and clinically significant changes in the DBT group over the WL group at 20 weeks, but not at 32 weeks.

Conclusions/limitations

- Brief DBT skills training reduced suicidal and NSSI episodes in patients with BPD. Participants in the DBT group also demonstrated greater improvement in anger, distress tolerance, and emotion regulation compared to the control group. These results were evident 3 months after treatment. However, any gains in health care utilization, social adjustment, symptom distress, and borderline symptoms diminished or did not differ from waitlist participants at Week 32. At that time, participants in the DBT group demonstrated a similar level of symptomatology as the WL group.

- Limitations include the use of an active waitlist control group, allowance of concurrent treatments, the absence of an active therapeutic comparator group, use of self-report measures, use of an instrument with unknown psychometric properties, and a relatively short 3-month follow-up period.

3. Bozzatello P, Bellino S. Combined therapy with interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for borderline personality disorder: a two-years follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:151-156.

Psychotherapeutic options for treating BPD include DBT, mentalization-based treatment, schema-focused therapy, transference-based psychotherapy, and systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving. More recently, interpersonal therapy also has been adapted for BPD (IPT-BPD). However, thus far no trials have investigated the long-term effects of this therapy on BPD. In 2010, Bellino et al11 published a 32-week RCT examining the effect of IPT-BPD on BPD. They concluded that IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine was superior to fluoxetine alone in improving symptoms and quality of life. The present study by Bozzatello et al6 examined whether the benefits of IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine demonstrated in the 2010 study persisted over a 24-month follow-up.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In the 2010 study by Bellino et al,11 55 outpatients who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to receive IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine (combined therapy) or fluoxetine alone for 32 weeks. Forty-four participants completed a 24-month follow-up study (n = 22 for IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine, n = 22 for fluoxetine only).

- Clinical assessments were performed at 6, 12, and 24 months, and used the same instruments as the original study, including the Clinical Global Impression Scale–Severity item, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS), Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment, Satisfaction Profile (SAT-P), and the Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index (BPDSI).

Outcomes

- While the original study demonstrated that combined therapy had a clinically significant effect over fluoxetine alone on both HARS score and the BPDSI item “affective instability” at 32 weeks, this advantage was maintained only at the 6-month assessment.

- The improvements that the combined therapy provided over fluoxetine monotherapy on the BPDSI items of “impulsivity” and “interpersonal relationships” as well as the SAT-P factors of social and psychological functioning at 32 weeks were preserved at 24 months. No additional improvements were seen.

Conclusions/limitations

- The improvements in impulsivity, interpersonal functioning, social functioning, and psychological functioning at 32 weeks seen with IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine compared with fluoxetine alone persisted for 2 years after completing therapy; no further improvements were seen.

- The improvements to anxiety and affective instability that combined therapy demonstrated over fluoxetine monotherapy at 32 weeks were not maintained at 24 months.

- Limitations include a small sample size, exclusion of psychiatric comorbidities, and a lack of assessment of session or medication adherence.

4. Antonsen BT, Kvarstein EH, Urnes Ø, et al. Favourable outcome of long-term combined psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder: six-year follow-up of a randomized study. Psychother Res. 2017;27(1):51-63.

While many studies have demonstrated the benefits of psychotherapy for treating personality disorders, there is limited research of how different levels of psychotherapy may impact treatment outcomes. An RCT called the Ullevål Personality Project (UPP)12 compared an intensive combined treatment program (CP) with outpatient individual psychotherapy (OIP) in patients with personality disorders. The CP program consisted of short-term day-hospital treatment followed by outpatient combined group and individual psychotherapy. The outcomes this RCT evaluated included suicide attempts, suicidal thoughts, self-injury, psychosocial functioning, symptom distress, and interpersonal and personality problems. A 6-year follow-up concluded there were no differences in outcomes between the 2 treatment groups. However, in this RCT, Antonsen et al7 examined whether CP produced statistically significant benefits over OIP in a subset of patients with BPD.

Study design

- In the UPP trial,12 117 patients who met DSM-IV criteria for personality disorders (excluding antisocial and schizotypal personality disorder) were randomized to receive 18 weeks of day hospital psychotherapy followed by CP or OIP. Fifty-two participants in the UPP were diagnosed with BPD, and 34 of these participants completed the 6-year follow-up investigation.

- Symptom distress, psychosocial functioning, interpersonal problems, quality of life, personality functioning, and self-harm/suicidal thoughts/suicide attempts were assessed at baseline, 8 months, 18 months, 3 years, and 6 years using the SCL-90-R Global Severity Index (GSI), BDI, Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS), Quality of Life 10-point scale (QOL), Circumplex of Interpersonal Problems (CIP), and the 60-item short form of the Severity Indices of Personality Problems (SIPP-118) questionnaire.

Outcomes

- Compared to the OIP group, the CP group demonstrated statistically significant reductions in symptom distress at Year 6 as measured by the SCL-90-R GSI. Between Years 3 and 6, the CP group continued to show improvements in psychosocial functioning as demonstrated by improvements in GAF and WSAS scores. The OIP group’s scores worsened during this time. Compared to the OIP group, participants in the CP group also had significantly better outcomes on the SIPP-118 domains of self-control and identity integration.

- There were no significant differences between groups on the proportion of participants who engaged in self-harm or experienced suicidal thoughts or attempts. There were no significant differences in outcomes between the treatment groups on the CIP, BDI, or QOL.

- Participants in CP group tended to use fewer psychotropic medications than those in the OIP group over time, but this difference was not statistically significant. The 2 groups did not differ in use of health care services over the last year.

- Avoidant personality disorder (AVPD) did not have a significant moderator effect on GAF score. Comorbid AVPD was a negative predictor of GAF score, independent of the group.

Conclusions/limitations

- Both groups experienced a remission rate of 90% at 6-year follow-up. Compared with the OIP group, participants in the CP group experienced significantly greater reductions in symptom distress and improvements in self-control and identity integration at 6 years. Between Years 3 and 6, participants in the CP group experienced significant improvements in psychosocial functioning compared with OIP group participants. The 2 groups did not differ on other outcomes, including the CIP, BDI, QOL, suicidal thoughts, suicidal attempts, self-harm, and health care utilization.

- Despite statistically significant differences in GAF scores favoring the CP group over the OIP group during Years 3 to 6, GAF scores did not differ significantly in the final year, which suggests that symptomatic remission does not equal functional improvement.

- Limitations include a lack of control for intensity or length of treatment in statistical analyses, small sample size, lack of correction for multiple testing, lack of an a priori power analysis, missing data and potential violation of the missing at random assumption, use of therapists’ preferred treatment method/practice, and a lack of control for other treatments.

5. Bateman A, Constantinou MP, Fonagy P, et al. Eight-year prospective follow-up of mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for people with borderline personality disorder. Personal Disord. 2021;12(4):291-299.

The efficacy of various psychotherapies for symptoms of BPD has been well established. However, there is limited evidence that these effects persist over time. In 2009, Bateman et al13 conducted an 18-month RCT comparing the effectiveness of outpatient mentalization-based treatment (MBT) against structured clinical management (SCM) for patients with BPD. Both groups experienced substantial improvements, but patients assigned to MBT demonstrated greater improvement in clinically significant problems, including suicide attempts and hospitalizations. In a 2021 follow-up to this study, Bateman et al8 investigated whether the MBT group’s gains in the primary outcomes (absence of severe self-harm, suicide attempts, and inpatient admissions in the previous 12 months), social functioning, vocational engagement, and mental health service usage were maintained throughout an 8-year follow-up period.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In the 2009 trial, Bateman et al13 randomized adult participants who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD and had a suicide attempt or episode of life-threatening self-harm in the past 6 months to receive 18 months of MBT or SCM. The primary outcome was crisis events, defined as a composite of suicidal and severe self-injurious behaviors and hospitalizations. The 2021 Bateman et al8 study expanded this investigation by collecting additional data on a yearly basis for 8 years.

- Of the 134 original participants, 98 agreed to complete the follow-up. Due to attrition, the follow-up period was limited to 8 years. At each yearly visit, researchers collected information on the primary outcome, the absence of severe self-harm, suicide attempts, and inpatient admissions in the previous 12 months.

- Secondary measures were collected mainly through a modified version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory and included critical incidents, psychiatric and medical hospital and community services, employment and other personally meaningful activity, psychoactive medication, and other mental health treatments.

Outcomes

- The number of participants who met diagnostic criteria for BPD at the 1-year follow-up was significantly lower in the MBT group compared with the SCM group. To improve participant retention, this outcome was not evaluated at later visits.

- The number of participants who achieved the primary recovery criteria of the original trial (absence of severe self-harm, suicide attempts, and inpatient admissions in the previous 12 months) and remained well throughout the entire follow-up period was significantly higher in the MBT group compared with the SCM group. The average number of years during which participants failed to meet recovery criteria was significantly greater in the SCM group compared with the MBT group.

- When controlling for age, treatment group was a significant predictor of recovery during the follow-up period. Overall, significantly fewer participants in the MBT group experienced critical incidents during the follow-up period.

- The SCM group used crisis mental health services for a significantly greater number of follow-up years than the MBT group, although the likelihood of ever using crisis services did not statistically differ between the groups. Both groups had similar use of outpatient mental health services, primary care services, and nonmental health medical services. Compared to the SCM group, the MBT group had significantly fewer professional support service visits and significantly fewer outpatient psychiatrist visits.

- MBT group participants spent more time in education, were less likely to be unemployed, and were less likely to use social care interventions than SCM group participants. Although those in the MBT group spent more months engaged in purposeful activity, there was no significant difference between the groups in the proportion of participants who did not engage in purposeful activity.

- The MBT group spent fewer months receiving psychotherapeutic medication compared with the SCM group. The variables that yielded significant 2-way interactions were eating disorder, substance use disorder, and physical abuse, suggesting greater benefit from MBT with these concurrent diagnoses. Younger age was associated with better outcomes.

Conclusions/limitations

- This study demonstrated that patients with BPD significantly benefited from specialized therapies such as MBT.

- At the 1 follow-up visit, the number of participants who met diagnostic criteria for BPD was significantly lower in the MBT group compared with the SCM group.

- The number of participants who had achieved the primary recovery criteria and remained well during the 8-year follow-up period was significantly higher in the MBT group compared to the SCM group.

- Limitations include increasing attrition over time, possible allegiance effects and unmasking of research assistants, lack of self-report questionnaires, and the potentially erroneous conclusion that increased use of services equates to poorer treatment response and greater need for support.

6. Klein JP, Hauer-von Mauschwitz A, Berger T, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the adjunctive use of an internet-based self-management intervention for borderline personality disorder in addition to care as usual: results from a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e047771.

Fewer than 1 in 4 patients with BPD have access to effective psychotherapies. The use of internet-based self-management interventions (SMIs) developed from evidence-based psychotherapies can help close this treatment gap. Although the efficacy of SMIs for several mental disorders has been demonstrated in multiple meta-analyses, results for BPD are mixed. In this study, Klein et al9 examined the effectiveness and safety of the adjunctive use of an SMI based on schema therapy in addition to care as usual (CAU) in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In a 12-month, rater-blind, controlled parallel group trial, adults who had a total BPDSI score ≥15 and either a diagnosis of BPD according to DSM-IV criteria or a probable diagnosis of BPD (if they had also received a BPD diagnosis from their treating physician) were randomized to an internet-based SMI based on schema therapy called priovi (n = 103) or CAU (n = 101). Participants could complete the SMI content in approximately 6 months but were recommended to use the intervention for the entire year.

- Participation in psychotherapy and psychiatric treatment, including pharmacotherapy, was permitted. At baseline, 74% of participants were receiving psychotherapy and 88% were receiving psychiatric treatment.

- The primary outcome was change in BPDSI score at 12 months. The primary safety outcome was the number of serious adverse events at 12 months. Secondary outcomes included BPD severity, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, quality of life, uncontrolled internet use, negative treatment effects, and satisfaction with the intervention. Most assessments were measured at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months.

Outcomes

- Large reductions in the severity of BPD symptoms as measured by change in BPDSI score was observed in both groups. Although the average reduction in BPDSI score was greater in the SMI group, this difference was not statistically significant from the CAU group.

- There was no statistically significant difference in the number of serious adverse events between groups at any time.

Conclusions/limitations

- Treatment with SMI did not result in improved outcomes over CAU. Although the average reduction in BPDSI score was greater in the SMI group compared to the CAU group, this difference was not statistically significant.

- The authors cautioned that the smaller-than-expected between-groups effect size must be interpreted against the background of an unexpectedly large effect in the CAU group. In fact, the CAU group pre/post effect was comparable to the pre/post effect of intensive specialized DBT treatment groups in previous RCTs.

- The authors also suggested that the high percentage of participants who received psychotherapy did not allow for an additional benefit from SMI.

- Limitations include recruitment method, lack of systematic assessment of accidental unblinding, high exclusion rate due to failure of the participant or treating clinician to provide confirmation of diagnosis, and the use of a serious adverse events assessment that is not psychometrically validated.

Bottom Line

Evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that internet-based psychoeducation, brief dialectical behavior therapy skills-only treatment, interpersonal therapy, a program that combines day treatment with individual and group psychotherapy, and mentalization-based treatment can improve symptoms and quality of life for patients with borderline personality disorder.

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 It is characterized by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior that often results in problems in relationships. As a result, patients with BPD tend to utilize more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or major depressive disorder.2

Some clinicians believe BPD is difficult to treat. While historically there has been little consensus on the best treatments for this disorder, current options include both pharmacologic and psychological interventions. In Part 1 of this 2-part article, we focused on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions.3 Here in Part 2, we focus on findings from 6 recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychosocial interventions for BPD

1. Zanarini MC, Conkey LC, Temes CM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of web-based psychoeducation for women with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3):16m11153. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11153

Research has shown that BPD is a treatable illness with a more favorable prognosis than previously believed. Despite this, patients often experience difficulty accessing the most up-to-date information on BPD, which can impede their treatment. A 2008 study by Zanarini et al10 of younger female patients with BPD demonstrated that immediate, in-person psychoeducation improved impulsivity and relationships. Widespread implementation of this program proved problematic, however, due to cost and personnel constraints. To resolve this issue, researchers developed an internet-based version of the program. In a 2018 follow-up study, Zanarini et al4 examined the effect of this internet-based psychoeducation program on symptoms of BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- Women (age 18 to 30) who met DSM-IV and Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines–Revised criteria for BPD were randomized to an internet-based psychoeducation treatment group (n = 40) or a control group (n = 40).

- Ten outcomes concerning symptom severity and psychosocial functioning were assessed during weeks 1 to 12 (acute phase) and at months 6, 9, and 12 (maintenance phase) using the self-report version of the Zanarini Rating Scale for BPD (ZAN-BPD), the Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time, the Sheehan Disability Scale, the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale, the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale, and Weissman’s Social Adjustment Scale (SAS).

Outcomes

- In the acute phase, treatment group participants experienced statistically significant improvements in all 10 outcomes. Control group participants demonstrated similar results, achieving statistically significant improvements in 7 of 10 outcomes.

- Compared to the control group, the treatment group experienced a more significant reduction in impulsivity and improvement in psychosocial functioning as measured by the ZAN-BPD and SAS.

- In the maintenance phase, treatment group participants achieved statistically significant improvements in 9 of 10 outcomes, whereas control group participants demonstrated statistically significant improvements in only 3 of 10 outcomes.

- Compared to the control group, the treatment group also demonstrated a significantly greater improvement in all 4 sector scores and the total score of the ZAN-BP

Conclusions/limitations

- In patients with BPD, internet-based psychoeducation reduced symptom severity and improved psychosocial functioning, with effects lasting 1 year. Treatment group participants experienced clinically significant improvements in all outcomes measured during the acute phase of the study; most improvements were maintained over 1 year.

- While the control group initially saw similar improvements in most measurements, these improvements were not maintained as effectively over 1 year.

- Limitations include a female-only population, the restricted age range of participants, and recruitment exclusively from volunteers.

2. McMain SF, Guimond T, Barnhart R, et al. A randomized trial of brief dialectical behaviour therapy skills training in suicidal patients suffering from borderline disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(2):138-148.

Standard dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an effective treatment for BPD; however, access is often limited by shortages of clinicians and resources. Therefore, it has become increasingly common for clinical settings to offer patients only the skills training component of DBT, which requires fewer resources. While several clinical trials examining brief DBT skills–only treatment for BPD have shown promising results, it is unclear how effective this intervention is at reducing suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) episodes. McMain et al5 explored the effectiveness of brief DBT skills–only adjunctive treatment on the rates of suicidal and NSSI episodes in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In this 2-arm, single-blind, prospective controlled trial, 84 adults who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to a 20-week DBT skills training group (DBT group) or an active waitlist (WL group). No restrictions on additional psychosocial or pharmacologic treatments were imposed on either group.

- The primary outcome was the frequency of suicidal and NSSI episodes as measured by the Lifetime Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview and the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI). Measurements occurred at baseline, 10 weeks, 20 weeks, and 3 months posttreatment (32 weeks).

- Secondary outcomes included changes in health care utilization, BPD symptoms, and coping. These were assessed using the Treatment History Interview-2, Borderline Symptom List-23, State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory, Symptom Checklist-90-revised (SCL-90-R), Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)-II, Social Adjustment Scale Self-report, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, Distress Tolerance Scale, and Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Scale.

Outcomes

- At Week 32, compared to the WL group, the DBT group showed statistically significant greater reductions in the frequency of suicidal and NSSI episodes as measured by the LSASI but not by the DSHI. The DBT group experienced statistically significant improvements in distress tolerance and emotion regulation over the WL group at all points, but no difference on mindfulness. The DBT group achieved greater reductions in anger over time as compared to the WL group.

- At Week 20, compared to the WL group, the DBT group showed significant improvements in social adjustment, symptom distress, and borderline symptoms. There were no significant group differences on impulsivity. Between-group differences in the number of hospital admissions favored the DBT group at 10 and 20 weeks, but not at 32 weeks. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups with respect to the number of emergency department visits.

- Analyses of group differences in clinical improvement as measured by the SCL-90-R revealed statistically reliable and clinically significant changes in the DBT group over the WL group at 20 weeks, but not at 32 weeks.

Conclusions/limitations

- Brief DBT skills training reduced suicidal and NSSI episodes in patients with BPD. Participants in the DBT group also demonstrated greater improvement in anger, distress tolerance, and emotion regulation compared to the control group. These results were evident 3 months after treatment. However, any gains in health care utilization, social adjustment, symptom distress, and borderline symptoms diminished or did not differ from waitlist participants at Week 32. At that time, participants in the DBT group demonstrated a similar level of symptomatology as the WL group.

- Limitations include the use of an active waitlist control group, allowance of concurrent treatments, the absence of an active therapeutic comparator group, use of self-report measures, use of an instrument with unknown psychometric properties, and a relatively short 3-month follow-up period.

3. Bozzatello P, Bellino S. Combined therapy with interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for borderline personality disorder: a two-years follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:151-156.

Psychotherapeutic options for treating BPD include DBT, mentalization-based treatment, schema-focused therapy, transference-based psychotherapy, and systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving. More recently, interpersonal therapy also has been adapted for BPD (IPT-BPD). However, thus far no trials have investigated the long-term effects of this therapy on BPD. In 2010, Bellino et al11 published a 32-week RCT examining the effect of IPT-BPD on BPD. They concluded that IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine was superior to fluoxetine alone in improving symptoms and quality of life. The present study by Bozzatello et al6 examined whether the benefits of IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine demonstrated in the 2010 study persisted over a 24-month follow-up.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In the 2010 study by Bellino et al,11 55 outpatients who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to receive IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine (combined therapy) or fluoxetine alone for 32 weeks. Forty-four participants completed a 24-month follow-up study (n = 22 for IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine, n = 22 for fluoxetine only).

- Clinical assessments were performed at 6, 12, and 24 months, and used the same instruments as the original study, including the Clinical Global Impression Scale–Severity item, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS), Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment, Satisfaction Profile (SAT-P), and the Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index (BPDSI).

Outcomes

- While the original study demonstrated that combined therapy had a clinically significant effect over fluoxetine alone on both HARS score and the BPDSI item “affective instability” at 32 weeks, this advantage was maintained only at the 6-month assessment.

- The improvements that the combined therapy provided over fluoxetine monotherapy on the BPDSI items of “impulsivity” and “interpersonal relationships” as well as the SAT-P factors of social and psychological functioning at 32 weeks were preserved at 24 months. No additional improvements were seen.

Conclusions/limitations

- The improvements in impulsivity, interpersonal functioning, social functioning, and psychological functioning at 32 weeks seen with IPT-BPD plus fluoxetine compared with fluoxetine alone persisted for 2 years after completing therapy; no further improvements were seen.

- The improvements to anxiety and affective instability that combined therapy demonstrated over fluoxetine monotherapy at 32 weeks were not maintained at 24 months.

- Limitations include a small sample size, exclusion of psychiatric comorbidities, and a lack of assessment of session or medication adherence.

4. Antonsen BT, Kvarstein EH, Urnes Ø, et al. Favourable outcome of long-term combined psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder: six-year follow-up of a randomized study. Psychother Res. 2017;27(1):51-63.

While many studies have demonstrated the benefits of psychotherapy for treating personality disorders, there is limited research of how different levels of psychotherapy may impact treatment outcomes. An RCT called the Ullevål Personality Project (UPP)12 compared an intensive combined treatment program (CP) with outpatient individual psychotherapy (OIP) in patients with personality disorders. The CP program consisted of short-term day-hospital treatment followed by outpatient combined group and individual psychotherapy. The outcomes this RCT evaluated included suicide attempts, suicidal thoughts, self-injury, psychosocial functioning, symptom distress, and interpersonal and personality problems. A 6-year follow-up concluded there were no differences in outcomes between the 2 treatment groups. However, in this RCT, Antonsen et al7 examined whether CP produced statistically significant benefits over OIP in a subset of patients with BPD.

Study design

- In the UPP trial,12 117 patients who met DSM-IV criteria for personality disorders (excluding antisocial and schizotypal personality disorder) were randomized to receive 18 weeks of day hospital psychotherapy followed by CP or OIP. Fifty-two participants in the UPP were diagnosed with BPD, and 34 of these participants completed the 6-year follow-up investigation.

- Symptom distress, psychosocial functioning, interpersonal problems, quality of life, personality functioning, and self-harm/suicidal thoughts/suicide attempts were assessed at baseline, 8 months, 18 months, 3 years, and 6 years using the SCL-90-R Global Severity Index (GSI), BDI, Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS), Quality of Life 10-point scale (QOL), Circumplex of Interpersonal Problems (CIP), and the 60-item short form of the Severity Indices of Personality Problems (SIPP-118) questionnaire.

Outcomes

- Compared to the OIP group, the CP group demonstrated statistically significant reductions in symptom distress at Year 6 as measured by the SCL-90-R GSI. Between Years 3 and 6, the CP group continued to show improvements in psychosocial functioning as demonstrated by improvements in GAF and WSAS scores. The OIP group’s scores worsened during this time. Compared to the OIP group, participants in the CP group also had significantly better outcomes on the SIPP-118 domains of self-control and identity integration.

- There were no significant differences between groups on the proportion of participants who engaged in self-harm or experienced suicidal thoughts or attempts. There were no significant differences in outcomes between the treatment groups on the CIP, BDI, or QOL.

- Participants in CP group tended to use fewer psychotropic medications than those in the OIP group over time, but this difference was not statistically significant. The 2 groups did not differ in use of health care services over the last year.

- Avoidant personality disorder (AVPD) did not have a significant moderator effect on GAF score. Comorbid AVPD was a negative predictor of GAF score, independent of the group.

Conclusions/limitations

- Both groups experienced a remission rate of 90% at 6-year follow-up. Compared with the OIP group, participants in the CP group experienced significantly greater reductions in symptom distress and improvements in self-control and identity integration at 6 years. Between Years 3 and 6, participants in the CP group experienced significant improvements in psychosocial functioning compared with OIP group participants. The 2 groups did not differ on other outcomes, including the CIP, BDI, QOL, suicidal thoughts, suicidal attempts, self-harm, and health care utilization.

- Despite statistically significant differences in GAF scores favoring the CP group over the OIP group during Years 3 to 6, GAF scores did not differ significantly in the final year, which suggests that symptomatic remission does not equal functional improvement.

- Limitations include a lack of control for intensity or length of treatment in statistical analyses, small sample size, lack of correction for multiple testing, lack of an a priori power analysis, missing data and potential violation of the missing at random assumption, use of therapists’ preferred treatment method/practice, and a lack of control for other treatments.

5. Bateman A, Constantinou MP, Fonagy P, et al. Eight-year prospective follow-up of mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for people with borderline personality disorder. Personal Disord. 2021;12(4):291-299.

The efficacy of various psychotherapies for symptoms of BPD has been well established. However, there is limited evidence that these effects persist over time. In 2009, Bateman et al13 conducted an 18-month RCT comparing the effectiveness of outpatient mentalization-based treatment (MBT) against structured clinical management (SCM) for patients with BPD. Both groups experienced substantial improvements, but patients assigned to MBT demonstrated greater improvement in clinically significant problems, including suicide attempts and hospitalizations. In a 2021 follow-up to this study, Bateman et al8 investigated whether the MBT group’s gains in the primary outcomes (absence of severe self-harm, suicide attempts, and inpatient admissions in the previous 12 months), social functioning, vocational engagement, and mental health service usage were maintained throughout an 8-year follow-up period.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In the 2009 trial, Bateman et al13 randomized adult participants who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD and had a suicide attempt or episode of life-threatening self-harm in the past 6 months to receive 18 months of MBT or SCM. The primary outcome was crisis events, defined as a composite of suicidal and severe self-injurious behaviors and hospitalizations. The 2021 Bateman et al8 study expanded this investigation by collecting additional data on a yearly basis for 8 years.

- Of the 134 original participants, 98 agreed to complete the follow-up. Due to attrition, the follow-up period was limited to 8 years. At each yearly visit, researchers collected information on the primary outcome, the absence of severe self-harm, suicide attempts, and inpatient admissions in the previous 12 months.

- Secondary measures were collected mainly through a modified version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory and included critical incidents, psychiatric and medical hospital and community services, employment and other personally meaningful activity, psychoactive medication, and other mental health treatments.

Outcomes

- The number of participants who met diagnostic criteria for BPD at the 1-year follow-up was significantly lower in the MBT group compared with the SCM group. To improve participant retention, this outcome was not evaluated at later visits.

- The number of participants who achieved the primary recovery criteria of the original trial (absence of severe self-harm, suicide attempts, and inpatient admissions in the previous 12 months) and remained well throughout the entire follow-up period was significantly higher in the MBT group compared with the SCM group. The average number of years during which participants failed to meet recovery criteria was significantly greater in the SCM group compared with the MBT group.

- When controlling for age, treatment group was a significant predictor of recovery during the follow-up period. Overall, significantly fewer participants in the MBT group experienced critical incidents during the follow-up period.

- The SCM group used crisis mental health services for a significantly greater number of follow-up years than the MBT group, although the likelihood of ever using crisis services did not statistically differ between the groups. Both groups had similar use of outpatient mental health services, primary care services, and nonmental health medical services. Compared to the SCM group, the MBT group had significantly fewer professional support service visits and significantly fewer outpatient psychiatrist visits.

- MBT group participants spent more time in education, were less likely to be unemployed, and were less likely to use social care interventions than SCM group participants. Although those in the MBT group spent more months engaged in purposeful activity, there was no significant difference between the groups in the proportion of participants who did not engage in purposeful activity.

- The MBT group spent fewer months receiving psychotherapeutic medication compared with the SCM group. The variables that yielded significant 2-way interactions were eating disorder, substance use disorder, and physical abuse, suggesting greater benefit from MBT with these concurrent diagnoses. Younger age was associated with better outcomes.

Conclusions/limitations

- This study demonstrated that patients with BPD significantly benefited from specialized therapies such as MBT.

- At the 1 follow-up visit, the number of participants who met diagnostic criteria for BPD was significantly lower in the MBT group compared with the SCM group.

- The number of participants who had achieved the primary recovery criteria and remained well during the 8-year follow-up period was significantly higher in the MBT group compared to the SCM group.

- Limitations include increasing attrition over time, possible allegiance effects and unmasking of research assistants, lack of self-report questionnaires, and the potentially erroneous conclusion that increased use of services equates to poorer treatment response and greater need for support.

6. Klein JP, Hauer-von Mauschwitz A, Berger T, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the adjunctive use of an internet-based self-management intervention for borderline personality disorder in addition to care as usual: results from a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e047771.

Fewer than 1 in 4 patients with BPD have access to effective psychotherapies. The use of internet-based self-management interventions (SMIs) developed from evidence-based psychotherapies can help close this treatment gap. Although the efficacy of SMIs for several mental disorders has been demonstrated in multiple meta-analyses, results for BPD are mixed. In this study, Klein et al9 examined the effectiveness and safety of the adjunctive use of an SMI based on schema therapy in addition to care as usual (CAU) in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In a 12-month, rater-blind, controlled parallel group trial, adults who had a total BPDSI score ≥15 and either a diagnosis of BPD according to DSM-IV criteria or a probable diagnosis of BPD (if they had also received a BPD diagnosis from their treating physician) were randomized to an internet-based SMI based on schema therapy called priovi (n = 103) or CAU (n = 101). Participants could complete the SMI content in approximately 6 months but were recommended to use the intervention for the entire year.

- Participation in psychotherapy and psychiatric treatment, including pharmacotherapy, was permitted. At baseline, 74% of participants were receiving psychotherapy and 88% were receiving psychiatric treatment.

- The primary outcome was change in BPDSI score at 12 months. The primary safety outcome was the number of serious adverse events at 12 months. Secondary outcomes included BPD severity, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, quality of life, uncontrolled internet use, negative treatment effects, and satisfaction with the intervention. Most assessments were measured at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months.

Outcomes

- Large reductions in the severity of BPD symptoms as measured by change in BPDSI score was observed in both groups. Although the average reduction in BPDSI score was greater in the SMI group, this difference was not statistically significant from the CAU group.

- There was no statistically significant difference in the number of serious adverse events between groups at any time.

Conclusions/limitations

- Treatment with SMI did not result in improved outcomes over CAU. Although the average reduction in BPDSI score was greater in the SMI group compared to the CAU group, this difference was not statistically significant.

- The authors cautioned that the smaller-than-expected between-groups effect size must be interpreted against the background of an unexpectedly large effect in the CAU group. In fact, the CAU group pre/post effect was comparable to the pre/post effect of intensive specialized DBT treatment groups in previous RCTs.

- The authors also suggested that the high percentage of participants who received psychotherapy did not allow for an additional benefit from SMI.

- Limitations include recruitment method, lack of systematic assessment of accidental unblinding, high exclusion rate due to failure of the participant or treating clinician to provide confirmation of diagnosis, and the use of a serious adverse events assessment that is not psychometrically validated.

Bottom Line

Evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that internet-based psychoeducation, brief dialectical behavior therapy skills-only treatment, interpersonal therapy, a program that combines day treatment with individual and group psychotherapy, and mentalization-based treatment can improve symptoms and quality of life for patients with borderline personality disorder.

1. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TM, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):276-83.

2. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):295-302.

3. Saeed SA, Kallis AC. Borderline personality disorder: 6 studies of biological interventions. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):26-30,34-36.

4. Zanarini MC, Conkey LC, Temes CM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of web-based psychoeducation for women with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3):16m11153. doi:10.4088/JCP.16m11153

5. McMain SF, Guimond T, Barnhart R, et al. A randomized trial of brief dialectical behaviour therapy skills training in suicidal patients suffering from borderline disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(2):138-148. doi:10.1111/acps.12664

6. Bozzatello P, Bellino S. Combined therapy with interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for borderline personality disorder: a two-years follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:151-156. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.014

7. Antonsen BT, Kvarstein EH, Urnes Ø, et al. Favourable outcome of long-term combined psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder: six-year follow-up of a randomized study. Psychother Res. 2017;27(1):51-63. doi:10.1080/10503307.2015.1072283

8. Bateman A, Constantinou MP, Fonagy P, et al. Eight-year prospective follow-up of mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for people with borderline personality disorder. Personal Disord. 2021;12(4):291-299. doi:10.1037/per0000422