User login

Although a common condition in the general population, major depressive disorder (MDD) is even more prevalent among patients receiving medical care. Its early recognition and successful treatment have significant implications in all fields of medicine, and the predominant burden of treatment falls on primary care providers (PCPs). The prevalence of MDD over 12 months is about 6.6%; lifetime risk is about 16.6%.1,2 About 50% of depressive episodes are rated severe or higher level. Of those having a depressive episode lasting 1 year, only 51% will seek medical help, and only 42% of these will receive adequate treatment.3 The illness is present across cultures and socioeconomic strata, although the actual rates vary. Women have about a 2-fold higher rate of MDD than do men.4

The illness can vary from mild to severe. Primary care providers usually provide treatment for patients who are at the mild-to-moderate end of the spectrum; more severely ill patients are likely to require consulting with mental health specialists. Patients who have 1 episode of MDD have a 50% chance of having a second episode during their lifetime. After a second episode, the risk of another episode rises to about 80%.5 After a third episode, it is presumed patients will continue to have subsequent episodes, because the risk rises to 90%. Among patients with MDD, about 35% will have a chronic, relapsing pattern of illness.6 Because of a relative shortage of specialty mental health providers in many areas served by federal practitioners, it is important to maximize the impact of a patient’s primary care team in treating this common and persistent illness.

Morbidity from MDD includes dysfunction in all spheres of life: Difficulties with work, home life, self-care, medication adherence, and mental health are all encountered. Although a minority of patients with depression will attempt or complete suicide, depression is a major predictor of suicide risk. However, it is a modifiable risk factor with successful treatment. Among the general population, the reported risk of suicide is about 11.5 per 100,000 per year.7 Among patients with psychiatric illness, the rate is higher.

Many patients treated through the federal system have been identified as having a risk of suicide higher than that of the general population. These populations include veterans (41% to 61% above the national average); Native Americans aged 18 to 24 years (about 2 to 3 times the national average); and active-duty military (18.7 per 100,000 per year, 50% above the national average).8-10

Diagnosis

Several subtypes of MDD and associated depressive disorders exist. The diagnosis requires a constellation of criteria for diagnosis. Using the full criteria to make an MDD diagnosis may seem excessive, but its use is critical to guide sound treatment decisions (ie, past presence of manic or hypomanic episode, which would signify bipolar disorder, or psychotic symptoms that would dictate a different path and a referral to a psychiatrist). For example, an antidepressant given to a patient with a history of hypomania or mania can trigger a full manic episode with all the potential morbidity that mania entails. The presence of psychotic symptoms leads down a different treatment path that requires antipsychotic medication.

A major depressive episode includes the sine qua non of depressed mood or anhedonia (lack of experiencing or seeking pleasurable activities) and 3 to 4 associated criteria, including poor energy (often noted as “I just can’t seem to get moving”), insomnia/hypersomnia (usually middle or late insomnia) with difficulty concentrating (often seen as problems making decisions), increased sense of guilt or worthlessness, psychomotor agitation or retardation (often noted by the patient’s spouse), significant weight loss or gain (5%), and thoughts of death/dying or suicidal ideation. These must be present most days over the previous 2 weeks.1 The time duration criteria are important because some patients may seem very distressed during a visit but do not meet the criteria for depression or have the chronic depressive symptoms of MDD. Symptoms not meeting the full criteria may likely be noted as unspecified depressive disorder or dysthymia (now termed persistent depressive disorder in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition [DSM 5]).1 There are no FDA-approved treatments for these disorders; however, in cases requiring treatment, the standard of practice would be the same as for MDD.

The more severe types of MDD are usually not subtle and would likely require an immediate referral to a mental health professional. These include the presence of melancholic features, such as severe anhedonia, or loss of reactivity to normally pleasurable things, and at least 3 of the following: (1) distinct quality of depressed mood that is characterized as different from serious loss (ie, death of a loved one); (2) worse depression in the morning; (3) late insomnia (waking 2+ hours early); (4) marked psychomotor agitation or retardation; (5) significant anorexia or weight loss; and (6) excessive and inappropriate guilt; or the presence of psychotic features, such as delusions or hallucinations. There are other subtypes of MDD that can be found in DSM 5.

Treatment

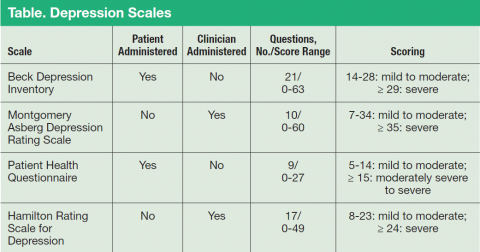

Major depressive disorder can be viewed as analogous to common illnesses, such as hypertension or diabetes, which are treated by a PCP; screening for depression should be systematically included as part of primary care services. The clear goal of treatment for any illness is elimination or reduction of symptoms so they no longer cause any significant problem for the patient. In MDD remission is the complete resolution of depressive symptoms. Response is considered a 50% reduction of MDD symptom severity as rated on various depression scales (Table). Because no objective physical measurements exist for assessing a patient’s depression, using a rating scale is necessary to monitor the severity of depressive symptoms and a patient’s response to treatment.

There are many validated depression scales, both clinician and patient administered. A patient-administered scale can save time and provide needed information; however, the questions of a clinician-administered scale can help screen for depression and improve a clinician’s sensitivity to a patient’s depression even if the patient does not bring up the subject. These scales are available on the Internet and include instructions for proper use. Benefits of the scales include giving clinicians data to discuss with patients and helping patients track their progress. For example, patients do not always recall how they were doing before they started taking medications, so the scales can help them measure the improvement.

Psychotherapies

As first-line treatment for patients with MDD, no clear benefit exists for medication over psychological therapy, specifically evidence-based therapies (EBTs).11,12 The best studied and known EBTs are cognitive behavioral therapy for depression (CBT-D) and interpersonal therapy (IPT). Both are brief, targeted therapies with clear rules and expectations as opposed to more traditional long-term therapies, such as insight-oriented psychotherapy. These therapies generally involve weekly meetings with a therapist for about 12 weeks. They both require the patient to do homework during the therapy period; therefore, it is important for the patient to be a willing participant in these treatments to receive the maximum benefit. Many patients prefer not taking medication for depression, so psychotherapy is an excellent option. It is widely believed, although without clear evidence at this time, that the combination of medications and EBT offers improved outcomes. There are no contraindications to combining antidepressant medication and EBT.

Medications

Given the realities of practice settings and patient preferences, medication is often the most practical first-line treatment choice. The newer antidepressant medications are the most likely choices in the primary care setting for treating depression, because they offer effective treatment with less severe adverse effects (AEs) and are much safer than the early tricyclic antidepressant and monoamine oxidase inhibitor medications. There are numerous metaanalyses comparing the effectiveness of the commonly prescribed newer antidepressants that consistently show there is no absolutely best choice antidepressant. A number of studies have tried to identify predictors of response for a particular antidepressant, but these have not yielded clinically significant results. Additionally, there is little difference between an antidepressant’s rate of response and tolerability on a population scale.13 Therefore, it is the AE profile and alternate uses that usually drive the choice of which to use for a particular patient.

Before discussing antidepressant medications with patients, it is important to note the FDA-required black box warning for increased risk of suicidal ideation in young people aged ≤ 24 years. The data that led to this warning did not show an increased risk of suicide.14 In patients aged > 24 years, there is no difference in risk of suicidal ideation, and in patients aged > 65 years, the risk of suicidal ideation decreases with the start of antidepressant medication.1

SSRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a common first-line treatment for MDD. Of interest, all SSRIs share the same mechanism of action (MOA), so failure of a single agent does not preclude a trial of a second agent of the same class, because the chance of response is essentially the same as switching the patient to another class. However, after a second failure, there is less chance of response to another SSRI.5 These agents are used for depression, anxiety (long term not acute), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The AEs include nausea, headache, insomnia, dry mouth, and loss of emotion. Other than feeling emotionally blunted, most of these AEs are usually temporary and resolve in days. Sexual dysfunction is often the AE of SSRIs that draws primary concern from patients. The most frequently experienced sexual AE is delayed orgasm. A review of FDA package inserts showed rates from 7% (sertraline) to as high as 28% (high-dose paroxetine).16,17 Impotence or decreased libido is often more concerning for patients and occurs at 3% to 6%. A common concern for patients is weight gain, and SSRIs are considered weight neutral. There has been no demonstrated benefit from combining these medications or using them with selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which only exposes patients to increased risk of AEs.

Other Medications

Often used as first-line medications for MDD, SNRIs are also useful for MDD, anxiety (long term not acute), and PTSD. Duloxetine also has indications for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, fibromyalgia, and chronic musculoskeletal pain. The SNRIs share the same AEs as SSRIs; however, some patients show an increase in blood pressure with venlafaxine. There has been no demonstrated benefit from combining these medications or with SSRIs. These are also considered weight neutral.

Mirtazapine, bupropion, and trazodone are medications with MOAs that do not fit within the abovementioned categories and differ from one another as well. These carry FDA indications for MDD. Bupropion also has indications of smoking cessation and seasonal affective disorder for the extended-release form. The AEs are varied and unique to each medication. Mirtazapine may show a rapid improvement in mood within 2 weeks and very low risk of sexual AEs.18 Associated with some weight gain and sedation, mirtazapine is useful for patients who have sleep problems or who are experiencing weight loss. It is noted in practice to be more sedating at lower doses.

Bupropion is considered an activating medication that can lead to jitteriness and increased anxiety for some patients. Bupropion also is associated with some weight loss and will disrupt sleep if taken later in the day. Therefore, bupropion can be useful for overweight patients or those with significant energy problems. It has few sexual AEs.

Although not widely used as a primary agent for MDD, trazodone is commonly used at low doses to treat insomnia. Sedation and dry mouth are the primary AEs with some sexual AEs. These medications can be used alone, in combination with SSRIs or SNRIs, or with one another in what is commonly called rational pharmacology.

Patient Response

There is a significant portion of patients who are treated for MDD who will not have an adequate response to their first medication, somewhat analogous to patients who are treated for hypertension or diabetes. If patients are showing a response at 6 to 8 weeks but not remission, the medication trial should continue for 12 or more weeks, increasing the dose as tolerated. If the dose has been raised to the maximum and if there are still significant depressive symptoms, some combination or augmentation strategy should be tried. If patients show no improvement at 6 to 8 weeks, it is appropriate to discontinue the current treatment and trial another medication.

There are no clear guidelines for the best way to switch medications. Some practitioners cross taper; some discontinue one medication prior to starting another; and some abruptly stop one and start another (ie, changing between SSRIs, or from a SSRI to a SNRI). In all cases, some caution is recommended to avoid discontinuation syndromes, which often drive the rate of discontinuation of the medication: Many people have no problem; others are very sensitive to dosage changes.

If a patient has achieved remission with the medication, the next step is easy—continue the medication. It is generally accepted that 6 to 12 months of medication treatment after remission is best, to avoid relapse to another episode of MDD. If a patient desires to stop medication after that period, it is best to slowly titrate off over a month or more, as the patient tolerates, to avoid the discontinuation syndrome and lessen the risk of relapse. Remission rates for a single trial of medication are 35% to 45% and up to 65% with repeated medication changes.19 Therefore, 35% of patients are inadequately relieved of illness, referred to as treatment-resistant illness.

In the patient who has experienced some benefit but not remission after taking the dose to the highest approved or tolerated dose, the question is whether to switch from a medication that has shown some efficacy to another that may be better or to add another medication to augment the efficacy of the first treatment. There are many opinions regarding these decisions and about how to proceed.

Augmentation and Combination Treatments

Augmentation is the use of a nonantidepressant medication in addition to the antidepressant to improve the efficacy of the antidepressant medication. Combination treatments use 2 antidepressant medications to improve efficacy. Although there is clear evidence of benefit from a number of augmentation strategies, including some that are FDA approved, combination treatments have conflicting

published evidence of efficacy.20,21

The FDA-approved medications for augmenting antidepressant medications in treatment-resistant MDD are aripiprazole and quetiapine XR. Both are atypical antipsychotic medications with the intrinsic class risks associated with them. Only psychiatrists usually use them, because most systems require the approval of a specialist to use these agents. Of particular concern is the longterm risks of tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, weight gain, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and sudden death in geriatric patients with dementia that warranted a black box warning. Other well-established augmentation strategies used by psychiatrists include the usage of lithium or T3 hormone. Using these agents requires collaborative monitoring with the PCP to prevent potential renal, cardiac, and thyroid abnormalities.

Conclusions

Successful treatment of depression in medical settings can have a positive impact on medical conditions, such as potentially improving outcomes in the treatment of diabetes, cardiovascular problems, and pain. Active screening for depression followed by a safe and well-tolerated antidepressant may relieve symptoms in 6 to 8 weeks in about half of treated patients.

Tracking responses with one of the aforementioned scales is an excellent way to guide treatment decisions. Lack of tolerability or response should not discourage physicians from trying a different antidepressant. The successful treatment of depression requires patience but can make a big difference in the patient’s quality of life.

Click here to read the digital editition.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5). 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas K, Walters E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

3. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al; National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095-3105.

4. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depressive and bipolar disorder. JAMA. 1996;276(4):293-299.

5. Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psych Rev. 2007;279(8):959-985.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Psychiatry Online Website. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed February 17, 2016.

7. American Association of Suicidology. U.S.A. suicide: 2014 official final data. American Association of Suicidology Website. http://www.suicidology.org /Portals/14/docs/Resources/FactSheets/2014/2014datapgsv1b.pdf. Revised December 22, 2015. Accessed February 17, 2016.

8. Kang HK, Bullman TA, Smolenski DJ, Skopp NA, Gahm GA, Reger MA. Suicide risk among 1.3 million veterans who were on active duty during the Iraq and Afghanistan

wars. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(2):96-100.

9. Jiang C, Mitran A, Miniño A, Ni H. Racial and gender disparities in suicide among young adults aged 18-24: United States, 2009-2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/suicide/racial_and_gender_2009_2013.htm. Updated September 30, 2015. Accessed February 9, 2016.

10. Smolenski DJ, Reger MA, Bush NE, Skopp NA, Zhang Y, Campise RL. Department of Defense suicide event report 2013 annual report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology Website. http://t2health.dcoe.mil/sites/default/files/DoDSER-2013-Jan-13-2015-Final.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2016.

11. DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):409-416.

12. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):971-978.

13. Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Reichenpfader U, et al. Drug class review: secondgeneration antidepressants final update 5 report. National Center for Biotechnology Information Website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK54355/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK54355.pdf. Updated March 11, 2011. Accessed February 17, 2016.

14. Friedman RA. Antidepressants’ black-box warning—10 years later. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1666-1668.

15. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Antidepressant use in children, adolescents, and adults. Revisions to product labeling. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrug-Class/UCM173233.pdf. Updated December 23, 2014. Accessed February 17, 2016.

16. Zoloft [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2014.

17. Paxil [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2012.

18. Lavergne F, Berlin I, Gamma A, Stassen H, Angst J. Onset of improvement and response to mirtazapine in depression: a multicenter naturalistic study of 4771 patients. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2005;1(1):59-68.

19. Rush JA, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12): 1231-1242.

20. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Stewart JW, et al. Combining medications to enhance depression outcomes (CO-MED): acute and long-term outcomes of a single-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):689-701.

21. Blier P, Ward HE, Tremblay P, Laberge L, Hébert C, Bergeron R. Combination of antidepressant medications from treatment initiation for major depressive disorder: a double-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):281-288.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

Although a common condition in the general population, major depressive disorder (MDD) is even more prevalent among patients receiving medical care. Its early recognition and successful treatment have significant implications in all fields of medicine, and the predominant burden of treatment falls on primary care providers (PCPs). The prevalence of MDD over 12 months is about 6.6%; lifetime risk is about 16.6%.1,2 About 50% of depressive episodes are rated severe or higher level. Of those having a depressive episode lasting 1 year, only 51% will seek medical help, and only 42% of these will receive adequate treatment.3 The illness is present across cultures and socioeconomic strata, although the actual rates vary. Women have about a 2-fold higher rate of MDD than do men.4

The illness can vary from mild to severe. Primary care providers usually provide treatment for patients who are at the mild-to-moderate end of the spectrum; more severely ill patients are likely to require consulting with mental health specialists. Patients who have 1 episode of MDD have a 50% chance of having a second episode during their lifetime. After a second episode, the risk of another episode rises to about 80%.5 After a third episode, it is presumed patients will continue to have subsequent episodes, because the risk rises to 90%. Among patients with MDD, about 35% will have a chronic, relapsing pattern of illness.6 Because of a relative shortage of specialty mental health providers in many areas served by federal practitioners, it is important to maximize the impact of a patient’s primary care team in treating this common and persistent illness.

Morbidity from MDD includes dysfunction in all spheres of life: Difficulties with work, home life, self-care, medication adherence, and mental health are all encountered. Although a minority of patients with depression will attempt or complete suicide, depression is a major predictor of suicide risk. However, it is a modifiable risk factor with successful treatment. Among the general population, the reported risk of suicide is about 11.5 per 100,000 per year.7 Among patients with psychiatric illness, the rate is higher.

Many patients treated through the federal system have been identified as having a risk of suicide higher than that of the general population. These populations include veterans (41% to 61% above the national average); Native Americans aged 18 to 24 years (about 2 to 3 times the national average); and active-duty military (18.7 per 100,000 per year, 50% above the national average).8-10

Diagnosis

Several subtypes of MDD and associated depressive disorders exist. The diagnosis requires a constellation of criteria for diagnosis. Using the full criteria to make an MDD diagnosis may seem excessive, but its use is critical to guide sound treatment decisions (ie, past presence of manic or hypomanic episode, which would signify bipolar disorder, or psychotic symptoms that would dictate a different path and a referral to a psychiatrist). For example, an antidepressant given to a patient with a history of hypomania or mania can trigger a full manic episode with all the potential morbidity that mania entails. The presence of psychotic symptoms leads down a different treatment path that requires antipsychotic medication.

A major depressive episode includes the sine qua non of depressed mood or anhedonia (lack of experiencing or seeking pleasurable activities) and 3 to 4 associated criteria, including poor energy (often noted as “I just can’t seem to get moving”), insomnia/hypersomnia (usually middle or late insomnia) with difficulty concentrating (often seen as problems making decisions), increased sense of guilt or worthlessness, psychomotor agitation or retardation (often noted by the patient’s spouse), significant weight loss or gain (5%), and thoughts of death/dying or suicidal ideation. These must be present most days over the previous 2 weeks.1 The time duration criteria are important because some patients may seem very distressed during a visit but do not meet the criteria for depression or have the chronic depressive symptoms of MDD. Symptoms not meeting the full criteria may likely be noted as unspecified depressive disorder or dysthymia (now termed persistent depressive disorder in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition [DSM 5]).1 There are no FDA-approved treatments for these disorders; however, in cases requiring treatment, the standard of practice would be the same as for MDD.

The more severe types of MDD are usually not subtle and would likely require an immediate referral to a mental health professional. These include the presence of melancholic features, such as severe anhedonia, or loss of reactivity to normally pleasurable things, and at least 3 of the following: (1) distinct quality of depressed mood that is characterized as different from serious loss (ie, death of a loved one); (2) worse depression in the morning; (3) late insomnia (waking 2+ hours early); (4) marked psychomotor agitation or retardation; (5) significant anorexia or weight loss; and (6) excessive and inappropriate guilt; or the presence of psychotic features, such as delusions or hallucinations. There are other subtypes of MDD that can be found in DSM 5.

Treatment

Major depressive disorder can be viewed as analogous to common illnesses, such as hypertension or diabetes, which are treated by a PCP; screening for depression should be systematically included as part of primary care services. The clear goal of treatment for any illness is elimination or reduction of symptoms so they no longer cause any significant problem for the patient. In MDD remission is the complete resolution of depressive symptoms. Response is considered a 50% reduction of MDD symptom severity as rated on various depression scales (Table). Because no objective physical measurements exist for assessing a patient’s depression, using a rating scale is necessary to monitor the severity of depressive symptoms and a patient’s response to treatment.

There are many validated depression scales, both clinician and patient administered. A patient-administered scale can save time and provide needed information; however, the questions of a clinician-administered scale can help screen for depression and improve a clinician’s sensitivity to a patient’s depression even if the patient does not bring up the subject. These scales are available on the Internet and include instructions for proper use. Benefits of the scales include giving clinicians data to discuss with patients and helping patients track their progress. For example, patients do not always recall how they were doing before they started taking medications, so the scales can help them measure the improvement.

Psychotherapies

As first-line treatment for patients with MDD, no clear benefit exists for medication over psychological therapy, specifically evidence-based therapies (EBTs).11,12 The best studied and known EBTs are cognitive behavioral therapy for depression (CBT-D) and interpersonal therapy (IPT). Both are brief, targeted therapies with clear rules and expectations as opposed to more traditional long-term therapies, such as insight-oriented psychotherapy. These therapies generally involve weekly meetings with a therapist for about 12 weeks. They both require the patient to do homework during the therapy period; therefore, it is important for the patient to be a willing participant in these treatments to receive the maximum benefit. Many patients prefer not taking medication for depression, so psychotherapy is an excellent option. It is widely believed, although without clear evidence at this time, that the combination of medications and EBT offers improved outcomes. There are no contraindications to combining antidepressant medication and EBT.

Medications

Given the realities of practice settings and patient preferences, medication is often the most practical first-line treatment choice. The newer antidepressant medications are the most likely choices in the primary care setting for treating depression, because they offer effective treatment with less severe adverse effects (AEs) and are much safer than the early tricyclic antidepressant and monoamine oxidase inhibitor medications. There are numerous metaanalyses comparing the effectiveness of the commonly prescribed newer antidepressants that consistently show there is no absolutely best choice antidepressant. A number of studies have tried to identify predictors of response for a particular antidepressant, but these have not yielded clinically significant results. Additionally, there is little difference between an antidepressant’s rate of response and tolerability on a population scale.13 Therefore, it is the AE profile and alternate uses that usually drive the choice of which to use for a particular patient.

Before discussing antidepressant medications with patients, it is important to note the FDA-required black box warning for increased risk of suicidal ideation in young people aged ≤ 24 years. The data that led to this warning did not show an increased risk of suicide.14 In patients aged > 24 years, there is no difference in risk of suicidal ideation, and in patients aged > 65 years, the risk of suicidal ideation decreases with the start of antidepressant medication.1

SSRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a common first-line treatment for MDD. Of interest, all SSRIs share the same mechanism of action (MOA), so failure of a single agent does not preclude a trial of a second agent of the same class, because the chance of response is essentially the same as switching the patient to another class. However, after a second failure, there is less chance of response to another SSRI.5 These agents are used for depression, anxiety (long term not acute), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The AEs include nausea, headache, insomnia, dry mouth, and loss of emotion. Other than feeling emotionally blunted, most of these AEs are usually temporary and resolve in days. Sexual dysfunction is often the AE of SSRIs that draws primary concern from patients. The most frequently experienced sexual AE is delayed orgasm. A review of FDA package inserts showed rates from 7% (sertraline) to as high as 28% (high-dose paroxetine).16,17 Impotence or decreased libido is often more concerning for patients and occurs at 3% to 6%. A common concern for patients is weight gain, and SSRIs are considered weight neutral. There has been no demonstrated benefit from combining these medications or using them with selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which only exposes patients to increased risk of AEs.

Other Medications

Often used as first-line medications for MDD, SNRIs are also useful for MDD, anxiety (long term not acute), and PTSD. Duloxetine also has indications for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, fibromyalgia, and chronic musculoskeletal pain. The SNRIs share the same AEs as SSRIs; however, some patients show an increase in blood pressure with venlafaxine. There has been no demonstrated benefit from combining these medications or with SSRIs. These are also considered weight neutral.

Mirtazapine, bupropion, and trazodone are medications with MOAs that do not fit within the abovementioned categories and differ from one another as well. These carry FDA indications for MDD. Bupropion also has indications of smoking cessation and seasonal affective disorder for the extended-release form. The AEs are varied and unique to each medication. Mirtazapine may show a rapid improvement in mood within 2 weeks and very low risk of sexual AEs.18 Associated with some weight gain and sedation, mirtazapine is useful for patients who have sleep problems or who are experiencing weight loss. It is noted in practice to be more sedating at lower doses.

Bupropion is considered an activating medication that can lead to jitteriness and increased anxiety for some patients. Bupropion also is associated with some weight loss and will disrupt sleep if taken later in the day. Therefore, bupropion can be useful for overweight patients or those with significant energy problems. It has few sexual AEs.

Although not widely used as a primary agent for MDD, trazodone is commonly used at low doses to treat insomnia. Sedation and dry mouth are the primary AEs with some sexual AEs. These medications can be used alone, in combination with SSRIs or SNRIs, or with one another in what is commonly called rational pharmacology.

Patient Response

There is a significant portion of patients who are treated for MDD who will not have an adequate response to their first medication, somewhat analogous to patients who are treated for hypertension or diabetes. If patients are showing a response at 6 to 8 weeks but not remission, the medication trial should continue for 12 or more weeks, increasing the dose as tolerated. If the dose has been raised to the maximum and if there are still significant depressive symptoms, some combination or augmentation strategy should be tried. If patients show no improvement at 6 to 8 weeks, it is appropriate to discontinue the current treatment and trial another medication.

There are no clear guidelines for the best way to switch medications. Some practitioners cross taper; some discontinue one medication prior to starting another; and some abruptly stop one and start another (ie, changing between SSRIs, or from a SSRI to a SNRI). In all cases, some caution is recommended to avoid discontinuation syndromes, which often drive the rate of discontinuation of the medication: Many people have no problem; others are very sensitive to dosage changes.

If a patient has achieved remission with the medication, the next step is easy—continue the medication. It is generally accepted that 6 to 12 months of medication treatment after remission is best, to avoid relapse to another episode of MDD. If a patient desires to stop medication after that period, it is best to slowly titrate off over a month or more, as the patient tolerates, to avoid the discontinuation syndrome and lessen the risk of relapse. Remission rates for a single trial of medication are 35% to 45% and up to 65% with repeated medication changes.19 Therefore, 35% of patients are inadequately relieved of illness, referred to as treatment-resistant illness.

In the patient who has experienced some benefit but not remission after taking the dose to the highest approved or tolerated dose, the question is whether to switch from a medication that has shown some efficacy to another that may be better or to add another medication to augment the efficacy of the first treatment. There are many opinions regarding these decisions and about how to proceed.

Augmentation and Combination Treatments

Augmentation is the use of a nonantidepressant medication in addition to the antidepressant to improve the efficacy of the antidepressant medication. Combination treatments use 2 antidepressant medications to improve efficacy. Although there is clear evidence of benefit from a number of augmentation strategies, including some that are FDA approved, combination treatments have conflicting

published evidence of efficacy.20,21

The FDA-approved medications for augmenting antidepressant medications in treatment-resistant MDD are aripiprazole and quetiapine XR. Both are atypical antipsychotic medications with the intrinsic class risks associated with them. Only psychiatrists usually use them, because most systems require the approval of a specialist to use these agents. Of particular concern is the longterm risks of tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, weight gain, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and sudden death in geriatric patients with dementia that warranted a black box warning. Other well-established augmentation strategies used by psychiatrists include the usage of lithium or T3 hormone. Using these agents requires collaborative monitoring with the PCP to prevent potential renal, cardiac, and thyroid abnormalities.

Conclusions

Successful treatment of depression in medical settings can have a positive impact on medical conditions, such as potentially improving outcomes in the treatment of diabetes, cardiovascular problems, and pain. Active screening for depression followed by a safe and well-tolerated antidepressant may relieve symptoms in 6 to 8 weeks in about half of treated patients.

Tracking responses with one of the aforementioned scales is an excellent way to guide treatment decisions. Lack of tolerability or response should not discourage physicians from trying a different antidepressant. The successful treatment of depression requires patience but can make a big difference in the patient’s quality of life.

Click here to read the digital editition.

Although a common condition in the general population, major depressive disorder (MDD) is even more prevalent among patients receiving medical care. Its early recognition and successful treatment have significant implications in all fields of medicine, and the predominant burden of treatment falls on primary care providers (PCPs). The prevalence of MDD over 12 months is about 6.6%; lifetime risk is about 16.6%.1,2 About 50% of depressive episodes are rated severe or higher level. Of those having a depressive episode lasting 1 year, only 51% will seek medical help, and only 42% of these will receive adequate treatment.3 The illness is present across cultures and socioeconomic strata, although the actual rates vary. Women have about a 2-fold higher rate of MDD than do men.4

The illness can vary from mild to severe. Primary care providers usually provide treatment for patients who are at the mild-to-moderate end of the spectrum; more severely ill patients are likely to require consulting with mental health specialists. Patients who have 1 episode of MDD have a 50% chance of having a second episode during their lifetime. After a second episode, the risk of another episode rises to about 80%.5 After a third episode, it is presumed patients will continue to have subsequent episodes, because the risk rises to 90%. Among patients with MDD, about 35% will have a chronic, relapsing pattern of illness.6 Because of a relative shortage of specialty mental health providers in many areas served by federal practitioners, it is important to maximize the impact of a patient’s primary care team in treating this common and persistent illness.

Morbidity from MDD includes dysfunction in all spheres of life: Difficulties with work, home life, self-care, medication adherence, and mental health are all encountered. Although a minority of patients with depression will attempt or complete suicide, depression is a major predictor of suicide risk. However, it is a modifiable risk factor with successful treatment. Among the general population, the reported risk of suicide is about 11.5 per 100,000 per year.7 Among patients with psychiatric illness, the rate is higher.

Many patients treated through the federal system have been identified as having a risk of suicide higher than that of the general population. These populations include veterans (41% to 61% above the national average); Native Americans aged 18 to 24 years (about 2 to 3 times the national average); and active-duty military (18.7 per 100,000 per year, 50% above the national average).8-10

Diagnosis

Several subtypes of MDD and associated depressive disorders exist. The diagnosis requires a constellation of criteria for diagnosis. Using the full criteria to make an MDD diagnosis may seem excessive, but its use is critical to guide sound treatment decisions (ie, past presence of manic or hypomanic episode, which would signify bipolar disorder, or psychotic symptoms that would dictate a different path and a referral to a psychiatrist). For example, an antidepressant given to a patient with a history of hypomania or mania can trigger a full manic episode with all the potential morbidity that mania entails. The presence of psychotic symptoms leads down a different treatment path that requires antipsychotic medication.

A major depressive episode includes the sine qua non of depressed mood or anhedonia (lack of experiencing or seeking pleasurable activities) and 3 to 4 associated criteria, including poor energy (often noted as “I just can’t seem to get moving”), insomnia/hypersomnia (usually middle or late insomnia) with difficulty concentrating (often seen as problems making decisions), increased sense of guilt or worthlessness, psychomotor agitation or retardation (often noted by the patient’s spouse), significant weight loss or gain (5%), and thoughts of death/dying or suicidal ideation. These must be present most days over the previous 2 weeks.1 The time duration criteria are important because some patients may seem very distressed during a visit but do not meet the criteria for depression or have the chronic depressive symptoms of MDD. Symptoms not meeting the full criteria may likely be noted as unspecified depressive disorder or dysthymia (now termed persistent depressive disorder in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition [DSM 5]).1 There are no FDA-approved treatments for these disorders; however, in cases requiring treatment, the standard of practice would be the same as for MDD.

The more severe types of MDD are usually not subtle and would likely require an immediate referral to a mental health professional. These include the presence of melancholic features, such as severe anhedonia, or loss of reactivity to normally pleasurable things, and at least 3 of the following: (1) distinct quality of depressed mood that is characterized as different from serious loss (ie, death of a loved one); (2) worse depression in the morning; (3) late insomnia (waking 2+ hours early); (4) marked psychomotor agitation or retardation; (5) significant anorexia or weight loss; and (6) excessive and inappropriate guilt; or the presence of psychotic features, such as delusions or hallucinations. There are other subtypes of MDD that can be found in DSM 5.

Treatment

Major depressive disorder can be viewed as analogous to common illnesses, such as hypertension or diabetes, which are treated by a PCP; screening for depression should be systematically included as part of primary care services. The clear goal of treatment for any illness is elimination or reduction of symptoms so they no longer cause any significant problem for the patient. In MDD remission is the complete resolution of depressive symptoms. Response is considered a 50% reduction of MDD symptom severity as rated on various depression scales (Table). Because no objective physical measurements exist for assessing a patient’s depression, using a rating scale is necessary to monitor the severity of depressive symptoms and a patient’s response to treatment.

There are many validated depression scales, both clinician and patient administered. A patient-administered scale can save time and provide needed information; however, the questions of a clinician-administered scale can help screen for depression and improve a clinician’s sensitivity to a patient’s depression even if the patient does not bring up the subject. These scales are available on the Internet and include instructions for proper use. Benefits of the scales include giving clinicians data to discuss with patients and helping patients track their progress. For example, patients do not always recall how they were doing before they started taking medications, so the scales can help them measure the improvement.

Psychotherapies

As first-line treatment for patients with MDD, no clear benefit exists for medication over psychological therapy, specifically evidence-based therapies (EBTs).11,12 The best studied and known EBTs are cognitive behavioral therapy for depression (CBT-D) and interpersonal therapy (IPT). Both are brief, targeted therapies with clear rules and expectations as opposed to more traditional long-term therapies, such as insight-oriented psychotherapy. These therapies generally involve weekly meetings with a therapist for about 12 weeks. They both require the patient to do homework during the therapy period; therefore, it is important for the patient to be a willing participant in these treatments to receive the maximum benefit. Many patients prefer not taking medication for depression, so psychotherapy is an excellent option. It is widely believed, although without clear evidence at this time, that the combination of medications and EBT offers improved outcomes. There are no contraindications to combining antidepressant medication and EBT.

Medications

Given the realities of practice settings and patient preferences, medication is often the most practical first-line treatment choice. The newer antidepressant medications are the most likely choices in the primary care setting for treating depression, because they offer effective treatment with less severe adverse effects (AEs) and are much safer than the early tricyclic antidepressant and monoamine oxidase inhibitor medications. There are numerous metaanalyses comparing the effectiveness of the commonly prescribed newer antidepressants that consistently show there is no absolutely best choice antidepressant. A number of studies have tried to identify predictors of response for a particular antidepressant, but these have not yielded clinically significant results. Additionally, there is little difference between an antidepressant’s rate of response and tolerability on a population scale.13 Therefore, it is the AE profile and alternate uses that usually drive the choice of which to use for a particular patient.

Before discussing antidepressant medications with patients, it is important to note the FDA-required black box warning for increased risk of suicidal ideation in young people aged ≤ 24 years. The data that led to this warning did not show an increased risk of suicide.14 In patients aged > 24 years, there is no difference in risk of suicidal ideation, and in patients aged > 65 years, the risk of suicidal ideation decreases with the start of antidepressant medication.1

SSRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a common first-line treatment for MDD. Of interest, all SSRIs share the same mechanism of action (MOA), so failure of a single agent does not preclude a trial of a second agent of the same class, because the chance of response is essentially the same as switching the patient to another class. However, after a second failure, there is less chance of response to another SSRI.5 These agents are used for depression, anxiety (long term not acute), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The AEs include nausea, headache, insomnia, dry mouth, and loss of emotion. Other than feeling emotionally blunted, most of these AEs are usually temporary and resolve in days. Sexual dysfunction is often the AE of SSRIs that draws primary concern from patients. The most frequently experienced sexual AE is delayed orgasm. A review of FDA package inserts showed rates from 7% (sertraline) to as high as 28% (high-dose paroxetine).16,17 Impotence or decreased libido is often more concerning for patients and occurs at 3% to 6%. A common concern for patients is weight gain, and SSRIs are considered weight neutral. There has been no demonstrated benefit from combining these medications or using them with selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which only exposes patients to increased risk of AEs.

Other Medications

Often used as first-line medications for MDD, SNRIs are also useful for MDD, anxiety (long term not acute), and PTSD. Duloxetine also has indications for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, fibromyalgia, and chronic musculoskeletal pain. The SNRIs share the same AEs as SSRIs; however, some patients show an increase in blood pressure with venlafaxine. There has been no demonstrated benefit from combining these medications or with SSRIs. These are also considered weight neutral.

Mirtazapine, bupropion, and trazodone are medications with MOAs that do not fit within the abovementioned categories and differ from one another as well. These carry FDA indications for MDD. Bupropion also has indications of smoking cessation and seasonal affective disorder for the extended-release form. The AEs are varied and unique to each medication. Mirtazapine may show a rapid improvement in mood within 2 weeks and very low risk of sexual AEs.18 Associated with some weight gain and sedation, mirtazapine is useful for patients who have sleep problems or who are experiencing weight loss. It is noted in practice to be more sedating at lower doses.

Bupropion is considered an activating medication that can lead to jitteriness and increased anxiety for some patients. Bupropion also is associated with some weight loss and will disrupt sleep if taken later in the day. Therefore, bupropion can be useful for overweight patients or those with significant energy problems. It has few sexual AEs.

Although not widely used as a primary agent for MDD, trazodone is commonly used at low doses to treat insomnia. Sedation and dry mouth are the primary AEs with some sexual AEs. These medications can be used alone, in combination with SSRIs or SNRIs, or with one another in what is commonly called rational pharmacology.

Patient Response

There is a significant portion of patients who are treated for MDD who will not have an adequate response to their first medication, somewhat analogous to patients who are treated for hypertension or diabetes. If patients are showing a response at 6 to 8 weeks but not remission, the medication trial should continue for 12 or more weeks, increasing the dose as tolerated. If the dose has been raised to the maximum and if there are still significant depressive symptoms, some combination or augmentation strategy should be tried. If patients show no improvement at 6 to 8 weeks, it is appropriate to discontinue the current treatment and trial another medication.

There are no clear guidelines for the best way to switch medications. Some practitioners cross taper; some discontinue one medication prior to starting another; and some abruptly stop one and start another (ie, changing between SSRIs, or from a SSRI to a SNRI). In all cases, some caution is recommended to avoid discontinuation syndromes, which often drive the rate of discontinuation of the medication: Many people have no problem; others are very sensitive to dosage changes.

If a patient has achieved remission with the medication, the next step is easy—continue the medication. It is generally accepted that 6 to 12 months of medication treatment after remission is best, to avoid relapse to another episode of MDD. If a patient desires to stop medication after that period, it is best to slowly titrate off over a month or more, as the patient tolerates, to avoid the discontinuation syndrome and lessen the risk of relapse. Remission rates for a single trial of medication are 35% to 45% and up to 65% with repeated medication changes.19 Therefore, 35% of patients are inadequately relieved of illness, referred to as treatment-resistant illness.

In the patient who has experienced some benefit but not remission after taking the dose to the highest approved or tolerated dose, the question is whether to switch from a medication that has shown some efficacy to another that may be better or to add another medication to augment the efficacy of the first treatment. There are many opinions regarding these decisions and about how to proceed.

Augmentation and Combination Treatments

Augmentation is the use of a nonantidepressant medication in addition to the antidepressant to improve the efficacy of the antidepressant medication. Combination treatments use 2 antidepressant medications to improve efficacy. Although there is clear evidence of benefit from a number of augmentation strategies, including some that are FDA approved, combination treatments have conflicting

published evidence of efficacy.20,21

The FDA-approved medications for augmenting antidepressant medications in treatment-resistant MDD are aripiprazole and quetiapine XR. Both are atypical antipsychotic medications with the intrinsic class risks associated with them. Only psychiatrists usually use them, because most systems require the approval of a specialist to use these agents. Of particular concern is the longterm risks of tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, weight gain, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and sudden death in geriatric patients with dementia that warranted a black box warning. Other well-established augmentation strategies used by psychiatrists include the usage of lithium or T3 hormone. Using these agents requires collaborative monitoring with the PCP to prevent potential renal, cardiac, and thyroid abnormalities.

Conclusions

Successful treatment of depression in medical settings can have a positive impact on medical conditions, such as potentially improving outcomes in the treatment of diabetes, cardiovascular problems, and pain. Active screening for depression followed by a safe and well-tolerated antidepressant may relieve symptoms in 6 to 8 weeks in about half of treated patients.

Tracking responses with one of the aforementioned scales is an excellent way to guide treatment decisions. Lack of tolerability or response should not discourage physicians from trying a different antidepressant. The successful treatment of depression requires patience but can make a big difference in the patient’s quality of life.

Click here to read the digital editition.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5). 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas K, Walters E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

3. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al; National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095-3105.

4. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depressive and bipolar disorder. JAMA. 1996;276(4):293-299.

5. Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psych Rev. 2007;279(8):959-985.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Psychiatry Online Website. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed February 17, 2016.

7. American Association of Suicidology. U.S.A. suicide: 2014 official final data. American Association of Suicidology Website. http://www.suicidology.org /Portals/14/docs/Resources/FactSheets/2014/2014datapgsv1b.pdf. Revised December 22, 2015. Accessed February 17, 2016.

8. Kang HK, Bullman TA, Smolenski DJ, Skopp NA, Gahm GA, Reger MA. Suicide risk among 1.3 million veterans who were on active duty during the Iraq and Afghanistan

wars. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(2):96-100.

9. Jiang C, Mitran A, Miniño A, Ni H. Racial and gender disparities in suicide among young adults aged 18-24: United States, 2009-2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/suicide/racial_and_gender_2009_2013.htm. Updated September 30, 2015. Accessed February 9, 2016.

10. Smolenski DJ, Reger MA, Bush NE, Skopp NA, Zhang Y, Campise RL. Department of Defense suicide event report 2013 annual report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology Website. http://t2health.dcoe.mil/sites/default/files/DoDSER-2013-Jan-13-2015-Final.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2016.

11. DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):409-416.

12. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):971-978.

13. Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Reichenpfader U, et al. Drug class review: secondgeneration antidepressants final update 5 report. National Center for Biotechnology Information Website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK54355/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK54355.pdf. Updated March 11, 2011. Accessed February 17, 2016.

14. Friedman RA. Antidepressants’ black-box warning—10 years later. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1666-1668.

15. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Antidepressant use in children, adolescents, and adults. Revisions to product labeling. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrug-Class/UCM173233.pdf. Updated December 23, 2014. Accessed February 17, 2016.

16. Zoloft [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2014.

17. Paxil [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2012.

18. Lavergne F, Berlin I, Gamma A, Stassen H, Angst J. Onset of improvement and response to mirtazapine in depression: a multicenter naturalistic study of 4771 patients. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2005;1(1):59-68.

19. Rush JA, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12): 1231-1242.

20. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Stewart JW, et al. Combining medications to enhance depression outcomes (CO-MED): acute and long-term outcomes of a single-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):689-701.

21. Blier P, Ward HE, Tremblay P, Laberge L, Hébert C, Bergeron R. Combination of antidepressant medications from treatment initiation for major depressive disorder: a double-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):281-288.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5). 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas K, Walters E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

3. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al; National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095-3105.

4. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depressive and bipolar disorder. JAMA. 1996;276(4):293-299.

5. Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psych Rev. 2007;279(8):959-985.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Psychiatry Online Website. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed February 17, 2016.

7. American Association of Suicidology. U.S.A. suicide: 2014 official final data. American Association of Suicidology Website. http://www.suicidology.org /Portals/14/docs/Resources/FactSheets/2014/2014datapgsv1b.pdf. Revised December 22, 2015. Accessed February 17, 2016.

8. Kang HK, Bullman TA, Smolenski DJ, Skopp NA, Gahm GA, Reger MA. Suicide risk among 1.3 million veterans who were on active duty during the Iraq and Afghanistan

wars. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(2):96-100.

9. Jiang C, Mitran A, Miniño A, Ni H. Racial and gender disparities in suicide among young adults aged 18-24: United States, 2009-2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/suicide/racial_and_gender_2009_2013.htm. Updated September 30, 2015. Accessed February 9, 2016.

10. Smolenski DJ, Reger MA, Bush NE, Skopp NA, Zhang Y, Campise RL. Department of Defense suicide event report 2013 annual report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology Website. http://t2health.dcoe.mil/sites/default/files/DoDSER-2013-Jan-13-2015-Final.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2016.

11. DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):409-416.

12. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):971-978.

13. Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Reichenpfader U, et al. Drug class review: secondgeneration antidepressants final update 5 report. National Center for Biotechnology Information Website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK54355/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK54355.pdf. Updated March 11, 2011. Accessed February 17, 2016.

14. Friedman RA. Antidepressants’ black-box warning—10 years later. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1666-1668.

15. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Antidepressant use in children, adolescents, and adults. Revisions to product labeling. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrug-Class/UCM173233.pdf. Updated December 23, 2014. Accessed February 17, 2016.

16. Zoloft [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2014.

17. Paxil [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2012.

18. Lavergne F, Berlin I, Gamma A, Stassen H, Angst J. Onset of improvement and response to mirtazapine in depression: a multicenter naturalistic study of 4771 patients. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2005;1(1):59-68.

19. Rush JA, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12): 1231-1242.

20. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Stewart JW, et al. Combining medications to enhance depression outcomes (CO-MED): acute and long-term outcomes of a single-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):689-701.

21. Blier P, Ward HE, Tremblay P, Laberge L, Hébert C, Bergeron R. Combination of antidepressant medications from treatment initiation for major depressive disorder: a double-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):281-288.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.