User login

In the last decade, there has been a major shift in our understanding of the pathogenesis of ovarian cancers. Current literature suggests that many high-grade serous carcinomas develop from the distal aspect of the fallopian tube and that serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma is likely the precursor. The critical role that the fallopian tubes play as the likely origin of many serous ovarian and pelvic cancers has resulted in a shift from prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy, which may increase risk for cardiovascular disease, to prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy (PBS) at the time of hysterectomy.

It is important that this shift occur with vaginal hysterectomy (VH) and not only with other surgical approaches. It is known that PBS is performed more commonly during laparoscopic or abdominal hysterectomy, and it’s possible that the need for adnexal surgery may further contribute to the decline in the rate of VH performed in the United States. This is despite evidence that the vaginal approach is preferred for benign hysterectomy even in patients with a nonprolapsed and large fibroid uterus, obesity, or previous pelvic surgery. Current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines also state that the need to perform adnexal surgery is not a contraindication to the vaginal approach.

So that more women may attain the benefits and advantages of VH, we need more effective teaching programs for vaginal surgery in residency training programs, hospitals, and community surgical centers. Moreover, we must appreciate that PBS with VH is safe and feasible. There are multiple techniques and tools available to facilitate the successful removal of the tubes, particularly in difficult cases.

The benefit and safety of PBS

Is PBS really effective in decreasing the incidence and mortality of ovarian cancer? A proposed randomized trial in Sweden with a target accrual of 4,400 patients – the Hysterectomy and Opportunistic Salpingectromy Study (HOPPSA, NCT03045965) – will evaluate the risk of ovarian cancer over a 10- to 30-year follow-up period in patients undergoing hysterectomy through all routes. While we wait for these prospective results, an elegant decision-model analysis suggests that routine PBS during VH would eliminate one diagnosis of ovarian cancer for every 225 women undergoing hysterectomy (reducing the risk from 0.956% to 0.511%) and would prevent one death for every 450 women (reducing the risk from 0.478% to 0.256%). The analysis, which drew upon published literature, Medicare reimbursement data, and the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, also found that PBS with VH is a less expensive strategy than VH alone because of an increased risk of future adnexal surgery in women retaining their tubes.1

The question of whether PBS places a woman at risk for early menopause is a relevant one. A study following women for 3-5 years after surgery showed that the addition of PBS to total laparoscopic hysterectomy in women of reproductive age does not appear to modify ovarian function.2 However, a recently published retrospective study from the Swedish National Registry showed that women who underwent PBS with abdominal or laparoscopic benign hysterectomy had an increased risk of menopausal symptoms 1 year after surgery.3 Women between the ages of 45-49 years were at highest risk, suggesting increased vulnerability to possible vascular effects of PBS. A longer follow-up period may be necessary to assess younger age groups.

In a multicenter, prospective and observational trial involving 69 patients undergoing VH, PBS was feasible in 75% (a majority of whom [78%] had pelvic organ prolapse) and increased operating time by 11 minutes with no additional complications noted. The surgeons in this study, primarily urogynecologists, utilized a clamp or double-clamp technique to remove the fimbriae.4

The decision-model analysis mentioned above found that PBS would involve slightly more complications than VH alone (7.95% vs. 7.68%),1 and a systematic review that I coauthored of PBS in low-risk women found a small to no increase in operative time and no additional estimated blood loss, hospital stay, or complications for PBS.5

Tools and techniques

Vaginal PBS can be accomplished easily with traditional clamp-cut-tie technique in cases where the fallopian tubes are accessible, such as in patients with uterine prolapse. Generally, most surgeons perform a distal fimbriectomy only for risk-reduction purposes because this is where precursor lesions known as serous tubal intraepithelial cancer (STIC) reside.

To perform a fimbriectomy in cases where the distal portion of the tube is easily accessible, a Kelly clamp is placed across the mesosalpinx, and a fine tie is used for ligature. In more challenging hysterectomy cases, such as in lack of uterine prolapse, large fibroid uterus, morbid obesity, and in patients with previous tubal ligation, the fallopian tubes can be more difficult to access. In these cases, I prefer the use of the vessel-sealing device to seal and divide the mesosalpinx.

Here I describe three specific techniques that can facilitate the removal of the fallopian tubes in more challenging cases. In each technique, the entire fallopian tubes are removed – without leaving behind the proximal stump. The residual stump has the potential of developing into a hydrosalpinx that may necessitate another procedure in the future for the patient.

Separate the fallopian tube before clamping the ‘utero-ovarian ligament’ technique

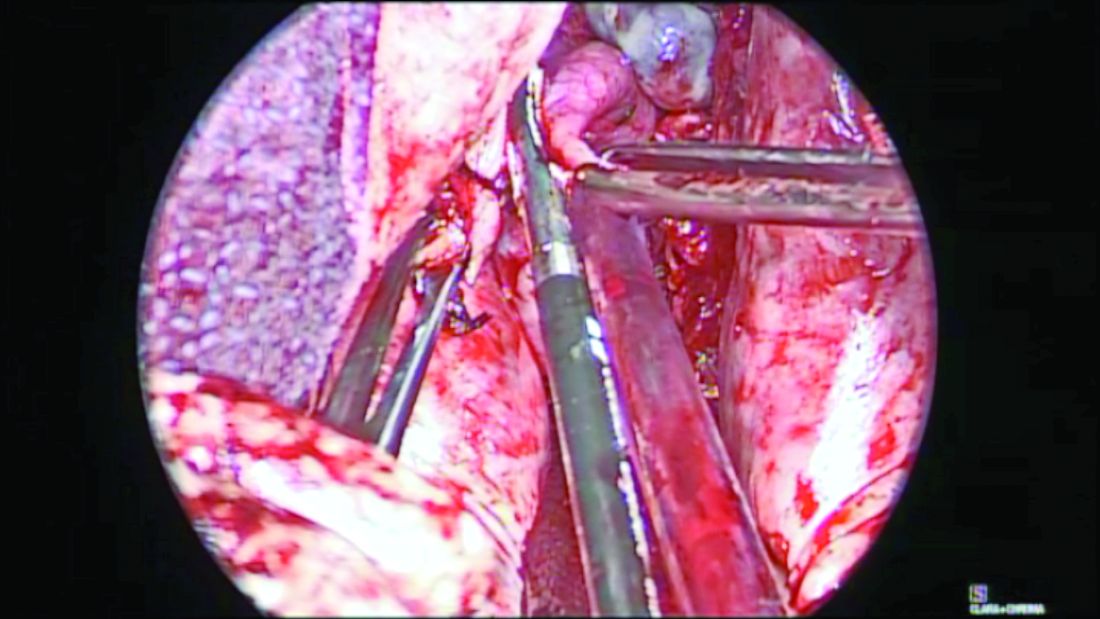

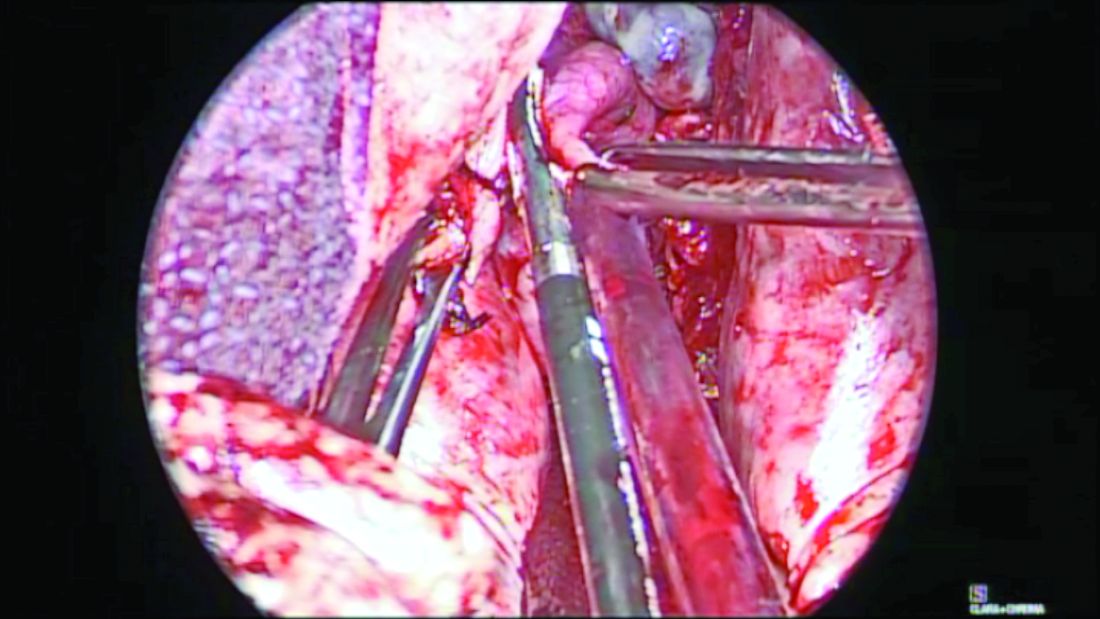

Before completion of the hysterectomy and clamping of the round ligament/fallopian tube/utero-ovarian ligament (RFUO) complex (commonly referred as the “utero-ovarian ligament”), I recommend first identifying the proximal portion of the fallopian tube. The isthmus is sealed and divided from its attachment to the uterine cornua, and a clamp is placed on the remaining round ligament/utero-ovarian ligament complex. The pedicle is then cut and tied. (Figure 1.) After removal of the uterus, the fallopian tube is ready to be grasped with an Allis clamp or Babcock forceps, and the remaining mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal portion/fimbriae.

Round ligament–mesosalpinx technique

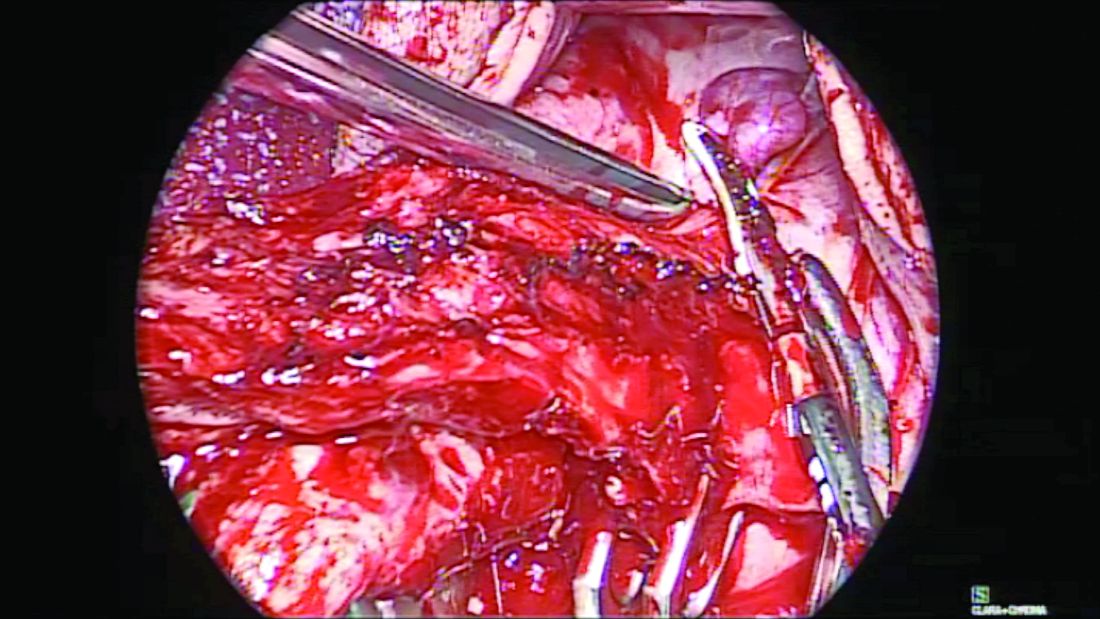

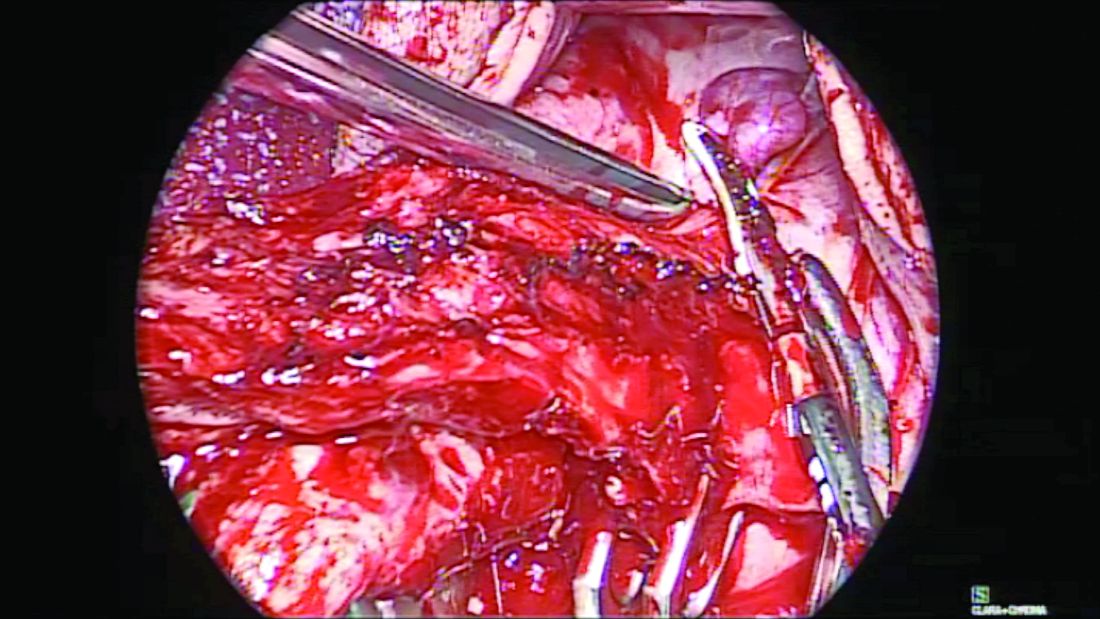

When the uterus is large or lacks prolapse, the fallopian tubes can be difficult to visualize. In such cases, I recommend the use of the round ligament–mesosalpinx technique. After completion of the hysterectomy and ligation of the RFUO complex, a long and moist vaginal pack (I prefer the 4” x 36” cotton vaginal pack by Dukal) is used to push the bowels back and expose the adnexae. The round ligament is identified within the RFUO complex and transected using a monopolar instrument. This step that separates the round ligament from the RFUO complex successfully releases the adnexae from the pelvic sidewall, making it easier to access the fallopian tubes (and the ovaries, when needed). A window is created in the mesosalpinx, and a curved clamp is placed on the ovarian vessels. Using sharp scissors, the proximal portion of the fallopian tube contained within the RFUO complex is separated, and the mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal end using the vessel-sealing device. (Figure 2.)

vNOTES (transvaginal Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery) salpingectomy technique

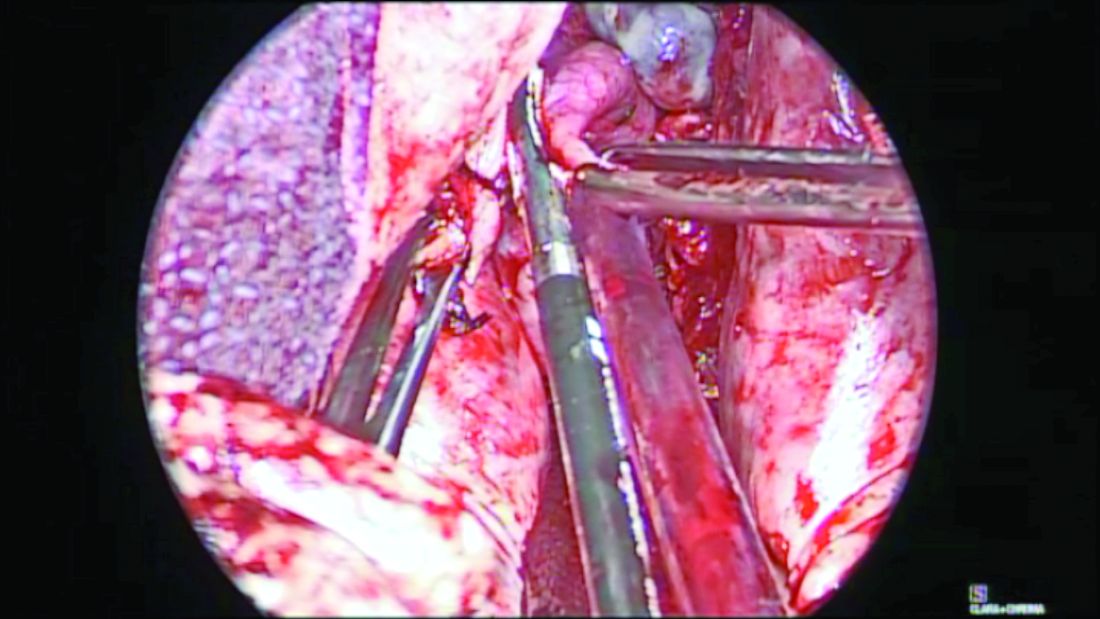

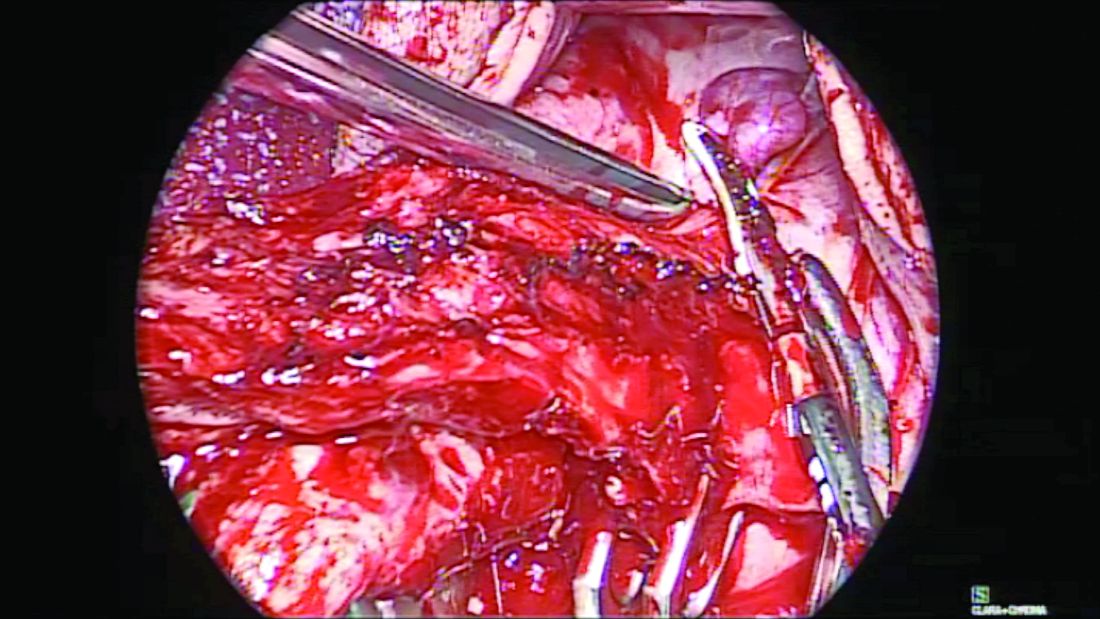

When the adnexae is noted to be high in the pelvis or when it is adherent to the pelvic sidewall, I recommend the vNOTES technique. It involves insertion of a mini-gel port into the vaginal opening. (Figure 3.) A 5-mm or 10-mm scope is inserted through this port for visualization. The fallopian tube can be grasped with a laparoscopic grasper and the mesosalpinx sealed and divided using a vessel-sealing device. (Figure 4.) Often, because the bowel is already retracted up with the vaginal pack, insufflation is not necessary with this procedure.

The change in our understanding of the etiology of ovarian cancer calls for salpingectomy during hysterectomy. With such tools, devices, and techniques that facilitate the vaginal removal of the fallopian tubes, the need for prophylactic salpingectomy should not be a deterrent to pursuing a hysterectomy vaginally.

Dr. Kho is head of the section of benign gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):503-4.

2. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Jan 1;24(1):145-50.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:85.e1-10.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:605.e1-5.

5. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Feb;24(2):218-29.

In the last decade, there has been a major shift in our understanding of the pathogenesis of ovarian cancers. Current literature suggests that many high-grade serous carcinomas develop from the distal aspect of the fallopian tube and that serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma is likely the precursor. The critical role that the fallopian tubes play as the likely origin of many serous ovarian and pelvic cancers has resulted in a shift from prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy, which may increase risk for cardiovascular disease, to prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy (PBS) at the time of hysterectomy.

It is important that this shift occur with vaginal hysterectomy (VH) and not only with other surgical approaches. It is known that PBS is performed more commonly during laparoscopic or abdominal hysterectomy, and it’s possible that the need for adnexal surgery may further contribute to the decline in the rate of VH performed in the United States. This is despite evidence that the vaginal approach is preferred for benign hysterectomy even in patients with a nonprolapsed and large fibroid uterus, obesity, or previous pelvic surgery. Current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines also state that the need to perform adnexal surgery is not a contraindication to the vaginal approach.

So that more women may attain the benefits and advantages of VH, we need more effective teaching programs for vaginal surgery in residency training programs, hospitals, and community surgical centers. Moreover, we must appreciate that PBS with VH is safe and feasible. There are multiple techniques and tools available to facilitate the successful removal of the tubes, particularly in difficult cases.

The benefit and safety of PBS

Is PBS really effective in decreasing the incidence and mortality of ovarian cancer? A proposed randomized trial in Sweden with a target accrual of 4,400 patients – the Hysterectomy and Opportunistic Salpingectromy Study (HOPPSA, NCT03045965) – will evaluate the risk of ovarian cancer over a 10- to 30-year follow-up period in patients undergoing hysterectomy through all routes. While we wait for these prospective results, an elegant decision-model analysis suggests that routine PBS during VH would eliminate one diagnosis of ovarian cancer for every 225 women undergoing hysterectomy (reducing the risk from 0.956% to 0.511%) and would prevent one death for every 450 women (reducing the risk from 0.478% to 0.256%). The analysis, which drew upon published literature, Medicare reimbursement data, and the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, also found that PBS with VH is a less expensive strategy than VH alone because of an increased risk of future adnexal surgery in women retaining their tubes.1

The question of whether PBS places a woman at risk for early menopause is a relevant one. A study following women for 3-5 years after surgery showed that the addition of PBS to total laparoscopic hysterectomy in women of reproductive age does not appear to modify ovarian function.2 However, a recently published retrospective study from the Swedish National Registry showed that women who underwent PBS with abdominal or laparoscopic benign hysterectomy had an increased risk of menopausal symptoms 1 year after surgery.3 Women between the ages of 45-49 years were at highest risk, suggesting increased vulnerability to possible vascular effects of PBS. A longer follow-up period may be necessary to assess younger age groups.

In a multicenter, prospective and observational trial involving 69 patients undergoing VH, PBS was feasible in 75% (a majority of whom [78%] had pelvic organ prolapse) and increased operating time by 11 minutes with no additional complications noted. The surgeons in this study, primarily urogynecologists, utilized a clamp or double-clamp technique to remove the fimbriae.4

The decision-model analysis mentioned above found that PBS would involve slightly more complications than VH alone (7.95% vs. 7.68%),1 and a systematic review that I coauthored of PBS in low-risk women found a small to no increase in operative time and no additional estimated blood loss, hospital stay, or complications for PBS.5

Tools and techniques

Vaginal PBS can be accomplished easily with traditional clamp-cut-tie technique in cases where the fallopian tubes are accessible, such as in patients with uterine prolapse. Generally, most surgeons perform a distal fimbriectomy only for risk-reduction purposes because this is where precursor lesions known as serous tubal intraepithelial cancer (STIC) reside.

To perform a fimbriectomy in cases where the distal portion of the tube is easily accessible, a Kelly clamp is placed across the mesosalpinx, and a fine tie is used for ligature. In more challenging hysterectomy cases, such as in lack of uterine prolapse, large fibroid uterus, morbid obesity, and in patients with previous tubal ligation, the fallopian tubes can be more difficult to access. In these cases, I prefer the use of the vessel-sealing device to seal and divide the mesosalpinx.

Here I describe three specific techniques that can facilitate the removal of the fallopian tubes in more challenging cases. In each technique, the entire fallopian tubes are removed – without leaving behind the proximal stump. The residual stump has the potential of developing into a hydrosalpinx that may necessitate another procedure in the future for the patient.

Separate the fallopian tube before clamping the ‘utero-ovarian ligament’ technique

Before completion of the hysterectomy and clamping of the round ligament/fallopian tube/utero-ovarian ligament (RFUO) complex (commonly referred as the “utero-ovarian ligament”), I recommend first identifying the proximal portion of the fallopian tube. The isthmus is sealed and divided from its attachment to the uterine cornua, and a clamp is placed on the remaining round ligament/utero-ovarian ligament complex. The pedicle is then cut and tied. (Figure 1.) After removal of the uterus, the fallopian tube is ready to be grasped with an Allis clamp or Babcock forceps, and the remaining mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal portion/fimbriae.

Round ligament–mesosalpinx technique

When the uterus is large or lacks prolapse, the fallopian tubes can be difficult to visualize. In such cases, I recommend the use of the round ligament–mesosalpinx technique. After completion of the hysterectomy and ligation of the RFUO complex, a long and moist vaginal pack (I prefer the 4” x 36” cotton vaginal pack by Dukal) is used to push the bowels back and expose the adnexae. The round ligament is identified within the RFUO complex and transected using a monopolar instrument. This step that separates the round ligament from the RFUO complex successfully releases the adnexae from the pelvic sidewall, making it easier to access the fallopian tubes (and the ovaries, when needed). A window is created in the mesosalpinx, and a curved clamp is placed on the ovarian vessels. Using sharp scissors, the proximal portion of the fallopian tube contained within the RFUO complex is separated, and the mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal end using the vessel-sealing device. (Figure 2.)

vNOTES (transvaginal Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery) salpingectomy technique

When the adnexae is noted to be high in the pelvis or when it is adherent to the pelvic sidewall, I recommend the vNOTES technique. It involves insertion of a mini-gel port into the vaginal opening. (Figure 3.) A 5-mm or 10-mm scope is inserted through this port for visualization. The fallopian tube can be grasped with a laparoscopic grasper and the mesosalpinx sealed and divided using a vessel-sealing device. (Figure 4.) Often, because the bowel is already retracted up with the vaginal pack, insufflation is not necessary with this procedure.

The change in our understanding of the etiology of ovarian cancer calls for salpingectomy during hysterectomy. With such tools, devices, and techniques that facilitate the vaginal removal of the fallopian tubes, the need for prophylactic salpingectomy should not be a deterrent to pursuing a hysterectomy vaginally.

Dr. Kho is head of the section of benign gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):503-4.

2. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Jan 1;24(1):145-50.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:85.e1-10.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:605.e1-5.

5. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Feb;24(2):218-29.

In the last decade, there has been a major shift in our understanding of the pathogenesis of ovarian cancers. Current literature suggests that many high-grade serous carcinomas develop from the distal aspect of the fallopian tube and that serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma is likely the precursor. The critical role that the fallopian tubes play as the likely origin of many serous ovarian and pelvic cancers has resulted in a shift from prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy, which may increase risk for cardiovascular disease, to prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy (PBS) at the time of hysterectomy.

It is important that this shift occur with vaginal hysterectomy (VH) and not only with other surgical approaches. It is known that PBS is performed more commonly during laparoscopic or abdominal hysterectomy, and it’s possible that the need for adnexal surgery may further contribute to the decline in the rate of VH performed in the United States. This is despite evidence that the vaginal approach is preferred for benign hysterectomy even in patients with a nonprolapsed and large fibroid uterus, obesity, or previous pelvic surgery. Current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines also state that the need to perform adnexal surgery is not a contraindication to the vaginal approach.

So that more women may attain the benefits and advantages of VH, we need more effective teaching programs for vaginal surgery in residency training programs, hospitals, and community surgical centers. Moreover, we must appreciate that PBS with VH is safe and feasible. There are multiple techniques and tools available to facilitate the successful removal of the tubes, particularly in difficult cases.

The benefit and safety of PBS

Is PBS really effective in decreasing the incidence and mortality of ovarian cancer? A proposed randomized trial in Sweden with a target accrual of 4,400 patients – the Hysterectomy and Opportunistic Salpingectromy Study (HOPPSA, NCT03045965) – will evaluate the risk of ovarian cancer over a 10- to 30-year follow-up period in patients undergoing hysterectomy through all routes. While we wait for these prospective results, an elegant decision-model analysis suggests that routine PBS during VH would eliminate one diagnosis of ovarian cancer for every 225 women undergoing hysterectomy (reducing the risk from 0.956% to 0.511%) and would prevent one death for every 450 women (reducing the risk from 0.478% to 0.256%). The analysis, which drew upon published literature, Medicare reimbursement data, and the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, also found that PBS with VH is a less expensive strategy than VH alone because of an increased risk of future adnexal surgery in women retaining their tubes.1

The question of whether PBS places a woman at risk for early menopause is a relevant one. A study following women for 3-5 years after surgery showed that the addition of PBS to total laparoscopic hysterectomy in women of reproductive age does not appear to modify ovarian function.2 However, a recently published retrospective study from the Swedish National Registry showed that women who underwent PBS with abdominal or laparoscopic benign hysterectomy had an increased risk of menopausal symptoms 1 year after surgery.3 Women between the ages of 45-49 years were at highest risk, suggesting increased vulnerability to possible vascular effects of PBS. A longer follow-up period may be necessary to assess younger age groups.

In a multicenter, prospective and observational trial involving 69 patients undergoing VH, PBS was feasible in 75% (a majority of whom [78%] had pelvic organ prolapse) and increased operating time by 11 minutes with no additional complications noted. The surgeons in this study, primarily urogynecologists, utilized a clamp or double-clamp technique to remove the fimbriae.4

The decision-model analysis mentioned above found that PBS would involve slightly more complications than VH alone (7.95% vs. 7.68%),1 and a systematic review that I coauthored of PBS in low-risk women found a small to no increase in operative time and no additional estimated blood loss, hospital stay, or complications for PBS.5

Tools and techniques

Vaginal PBS can be accomplished easily with traditional clamp-cut-tie technique in cases where the fallopian tubes are accessible, such as in patients with uterine prolapse. Generally, most surgeons perform a distal fimbriectomy only for risk-reduction purposes because this is where precursor lesions known as serous tubal intraepithelial cancer (STIC) reside.

To perform a fimbriectomy in cases where the distal portion of the tube is easily accessible, a Kelly clamp is placed across the mesosalpinx, and a fine tie is used for ligature. In more challenging hysterectomy cases, such as in lack of uterine prolapse, large fibroid uterus, morbid obesity, and in patients with previous tubal ligation, the fallopian tubes can be more difficult to access. In these cases, I prefer the use of the vessel-sealing device to seal and divide the mesosalpinx.

Here I describe three specific techniques that can facilitate the removal of the fallopian tubes in more challenging cases. In each technique, the entire fallopian tubes are removed – without leaving behind the proximal stump. The residual stump has the potential of developing into a hydrosalpinx that may necessitate another procedure in the future for the patient.

Separate the fallopian tube before clamping the ‘utero-ovarian ligament’ technique

Before completion of the hysterectomy and clamping of the round ligament/fallopian tube/utero-ovarian ligament (RFUO) complex (commonly referred as the “utero-ovarian ligament”), I recommend first identifying the proximal portion of the fallopian tube. The isthmus is sealed and divided from its attachment to the uterine cornua, and a clamp is placed on the remaining round ligament/utero-ovarian ligament complex. The pedicle is then cut and tied. (Figure 1.) After removal of the uterus, the fallopian tube is ready to be grasped with an Allis clamp or Babcock forceps, and the remaining mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal portion/fimbriae.

Round ligament–mesosalpinx technique

When the uterus is large or lacks prolapse, the fallopian tubes can be difficult to visualize. In such cases, I recommend the use of the round ligament–mesosalpinx technique. After completion of the hysterectomy and ligation of the RFUO complex, a long and moist vaginal pack (I prefer the 4” x 36” cotton vaginal pack by Dukal) is used to push the bowels back and expose the adnexae. The round ligament is identified within the RFUO complex and transected using a monopolar instrument. This step that separates the round ligament from the RFUO complex successfully releases the adnexae from the pelvic sidewall, making it easier to access the fallopian tubes (and the ovaries, when needed). A window is created in the mesosalpinx, and a curved clamp is placed on the ovarian vessels. Using sharp scissors, the proximal portion of the fallopian tube contained within the RFUO complex is separated, and the mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal end using the vessel-sealing device. (Figure 2.)

vNOTES (transvaginal Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery) salpingectomy technique

When the adnexae is noted to be high in the pelvis or when it is adherent to the pelvic sidewall, I recommend the vNOTES technique. It involves insertion of a mini-gel port into the vaginal opening. (Figure 3.) A 5-mm or 10-mm scope is inserted through this port for visualization. The fallopian tube can be grasped with a laparoscopic grasper and the mesosalpinx sealed and divided using a vessel-sealing device. (Figure 4.) Often, because the bowel is already retracted up with the vaginal pack, insufflation is not necessary with this procedure.

The change in our understanding of the etiology of ovarian cancer calls for salpingectomy during hysterectomy. With such tools, devices, and techniques that facilitate the vaginal removal of the fallopian tubes, the need for prophylactic salpingectomy should not be a deterrent to pursuing a hysterectomy vaginally.

Dr. Kho is head of the section of benign gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):503-4.

2. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Jan 1;24(1):145-50.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:85.e1-10.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:605.e1-5.

5. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Feb;24(2):218-29.