User login

The no-show rate is high in ambulatory psychiatric clinics, especially those associated with academic medical institutions, which usually accept all public insurance providers and do not maintain a strict rule by which patients are charged a penalty when they fail to keep a scheduled appointment—a policy that, to the contrary, is customary in private practice. The University of Texas (UT) Health Sciences Center at Houston is primarily an academic medical center with resident-managed, faculty-supervised clinics that provide care to a large volume of patients.

At the UT clinics, we have struggled with a high no-show rate, and were challenged to reduce that rate. Our study of the problem, formulation and application of strategies to reduce that rate, and a discussion of our results are provided here for the benefit of psychiatric clinicians who struggle with this problem, to the detriment of their patients’ health and the financial well-being of the practice.

For patients who have a severe psychiatric illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, 60% to 70% of the direct cost of their care is attributable to inpatient services.1,2 Poor medication adherence is a critical factor: It results in exacerbation of symptoms, relapse, and hospitalization. The matter is compounded by patients’ failure to show up for scheduled follow-up appointments.

Studies show that failure to attend routinely scheduled outpatient appointments increases the risk of hospitalization. Recent research has shown that, among all causes of hospitalization, length of stay and relapse hospitalization are increased in patients with low adherence to their treatment regimen.3 Patients who miss an appointment also are more unwell and more functionally impaired—also contributing to a higher risk and rate of rehospitalization.4,5

To begin to address the problem at UT, we acknowledged that an elevated no-show rate is linked to medication nonadherence, increased risk of re-hospitalization, and increased costs associated with poor care.

Impact of nonadherence

Significant evidence supports the efficacy of antipsychotic medications for treating schizophrenia, of course,6 but that success story is undermined by the mean rate of medication nonadherence among schizophrenia patients, which can be as high as 49% in studies.7 (The actual rate might be higher because those studies do not account for persons who refuse treatment or drop out.)

Nonadherence increases the risk of relapse 3.7-fold, compared with what is seen in patients who adhere to treatment.8 Nonadherence to a medication regimen also can increase patients’ risk of engaging in assault and other dangerous behaviors, especially during periods of psychosis.8 Variables consistently associated with nonadherence include poor insight, negative attitude or subjective response toward medication, previous nonadherence, substance abuse, shorter duration of illness, inadequate discharge planning or after-care environment, and poorer therapeutic alliance.7,8

Investigation of medication adherence in bipolar disorder suggests that 1 in 3 patients fail to take at least 30% of their medication.9 In such patients, medication nonadherence can lead to mania, depression, hospital readmission, suicide, increased substance abuse, and nonresponse to treatment.10,11

Depression also is associated with an increased rate of health care utilization and severe limitation in daily functioning.12 Compared with non-depressed patients, depressed patients are 3 times more likely to be nonadherent with medical treatment recommendations.13 Estimates of medication nonadherence for unipolar and bipolar disorders range from 10% to 60% (median, 40%). This prevalence has not changed significantly with the introduction of new medications.14

Our literature review of research devoted to reducing no-shows found that few studies have explored this critical treatment concern. The no-show rate was higher among younger patients and slightly higher among women, but varied by diagnosis.15 The most common reason psychiatric patients gave for missing an appointment was “forgetting”—a response heard twice as often among no-show patients in psychiatry than in other specialties.4

Little has been tried to solve the problem. Often, community mental health centers and private practices double-book appointments. Double-booking is intended to reduce the financial burden on the practice when a patient misses an appointment. This approach fails to address nonadherence or the poor care that usually results when a patient misses regular outpatient appointments.

Several methods have been employed to improve adherence, such as electronic pill dispensing.16 Increasing medication adherence appears to be a key factor in improving quality-of-life measures in patients with schizophrenia.6

The UT project

Methods. This project was completed at the ambulatory psychiatry clinic at the UT Medical School at Houston. The clinic staff comprises residents and faculty members who provide outpatient care. During the study period, the clinic was scheduling as many as 800 office visits a month, including a mix of new and follow-up appointments. Two weeks’ retrospective data revealed a no-show rate of 31%.

For the project, we defined no-show rate as the total number of patients who missed an appointment or canceled fewer than 24 hours before the scheduled time, divided by the total number of patients scheduled that day.

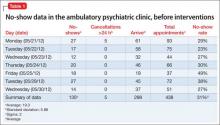

Table 1 demonstrates the no-show rate calculations for 1 of the weeks preceding the start of the project. Given approximately 800 patient appointments a month, a 31% no-show rate meant that, first, 248 patients failed to receive recommended care and, second, 248 appointment slots were wasted.

Besides undermining such components of quality care as patient safety and medication compliance, the high no-show rate also harms employee morale and productivity; impairs medical education; and, possibly, increases the use of emergency and after-hour services.

We agreed that our current no-show rate of 31% was too high.

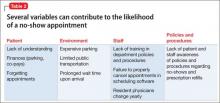

We then formed a team of residents, faculty members, therapists, front office staff, an office manager, and an office nurse. We explored and hypothesized what could be contributing to the high no-show rate (Table 2).

Several interventions were then devised and implemented:

• Patients. We increased patient education about 1) the need for regular follow-up and 2) risks associated with medication nonadherence.

• Environment. We explored environmental limitations to access and agreed that certain static factors could not be modified—eg, location of the clinic and lack of access to public transportation. We were able to make some changes to the environment (explained later) to reduce wait time.

• Staff. Some patients had complained of long wait times, which could hinder active participation in treatment. We agreed that the clinic nurse would make rounds through the waiting room every hour and talk to patients. The nurse would identify patients who had been waiting for longer than 30 minutes after their scheduled appointment time and notify the doctor accordingly. We also agreed to revise patient appointment reminder practices: instead of using an automated answering service, one of the staff members called patients personally to remind them about their appointments. (This also allowed us to update telephone numbers for many patients; numbers on record often were outdated.) We initially recruited summer interns and provided a written script to follow during calls to patients, which allowed patients to confirm, cancel, or reschedule their appointment. Once we demonstrated positive results from the change to personal calls, the department agreed to absorb the cost, and front desk personnel began making reminder calls.

• Policies and procedures. Although some practices are able to charge a small fine for missed appointments, this was not allowed at our institution. Instead, we had several departmental policies on the books, such as discharging patients from our clinics if they missed 3 consecutive appointments and limiting prescription refills to a maximum of 6 months. These policies were neither communicated to patients and staff, nor were they implemented. We decided to educate patients and staff and implement the policies.

• Transparency. We posted the no-show rate in common areas so that the team could review and follow the progression of that rate as we implemented the changes. This allowed team members to take ownership of the project and facilitated active participation.

By implementing these changes, we aimed to reduce the no-show rate to 20%.

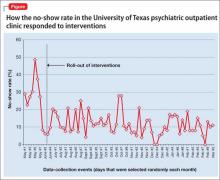

Results. We were able to reduce the no-show rate from a documented average of 31% to an average of 12% during the study period after implementing all the proposed changes in the outpatient clinics.

We calculated the no-show rate (as shown in Table 1 for May 2013), then collected the daily no-show rate from June to September 2013 (Figure). With these calculations, we demonstrated a reduction in the no-show rate to 12%. Because of the time and effort required, we reduced data collection from daily to weekly, beginning in September.

Applying the changes required consistent effort and substantial input from various stakeholders—front desk staff, residents, the nurse, therapists, and faculty. Gradually, we were able to implement all the changes.

Keeping the no-show rate low required consistent effort and monitoring of the newly implemented procedures because even a slight change, such as failure to make reminder calls, resulted in a sudden increase in the no-show rate (that was the case in October of the study period, when we were short-staffed and could not call every patient). Patients told us that it was difficult to ignore a personal call; if they were not planning to keep the appointment, the call allowed them to reschedule on the spot.

We also made sure that current no-show rates were posted in common areas, visible to team members every day.

Discussion

We attempted a literature review of research exploring approaches to reducing the no-show rate but found few studies that explored this critical concern in patient treatment.15 Some data suggested that, in the setting studied, the no-show rate:

• was higher among younger patients (age 20 to 39) than older ones (age 60 to 79)

• was slightly higher in women than in men

• varied by diagnosis.

We found a paucity of data regarding interventions that can reduce the no-show rate.

Among the changes we made, the one that had the greatest impact was personalized appointment reminder calls, as evidenced by our patients’ reports and the increase in the no-show rate when personal calls were not made.

We also realized that, although we had several departmental policies in place regarding appointments, they were not being followed. Raising awareness among team members and their patients also was an effective deterrent to a no-show for an appointment. For example, patients were informed that 3 consecutive no-shows could lead to termination of care. Often, they reacted with surprise to this caution but also voiced a desire to improve their attendance to avoid such an outcome.

We found that establishing common operational definitions is important. It also was important to have a cohesive team, with every member agreeing on goals and changes to operational policies that needed to be implemented. Support from the department chair and the administration, we learned, is vital to the success of such an intervention.

A note about limitations. The goal of the project was limited to reducing the no-show rate. We demonstrated that this is possible among patients who have a severe mental illness, and that reducing the associated waste of time and resources can improve finances in an academic department of psychiatry. We would need additional measures, however, to quantify medication adherence and hospitalization; a larger, more inclusive project is needed to demonstrate that reducing the no-show rate reduces the symptomatic burden of psychiatric illness.

Comments in conclusion

This project was designed and conducted as a required part of a Clinical Safety and Effectiveness Program at Memorial Hermann Texas Medical Center and the UT Medical School at Houston.17 Although there was initial hesitancy about attempting to reduce the no-show rate in a chronically mentally ill population, the success of this project—indeed, it surpassed its proposed goals—demonstrates that operational changes in any clinic can reduce the no-show rate. It also is important to maintain operational changes, however; without consistent effort, desired results cannot be sustained.

Last, it is possible to replicate the methodology of this project and thereby attempt to reduce the no-show rate in other divisions of medicine that offer care to chronically ill patients, such as pediatrics and family medicine.

Bottom Line

Failure to attend routinely scheduled outpatient appointments increases a patient’s functional impairment and risk of hospitalization. Patient education, appointment reminder phone calls, revised policies and procedures, and transparency regarding the no-show rate can reduce the number of missed appointments and improve patient outcomes.

Related Resources

• Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007;13:423-434.

• Molfenter T. Reducing appointment no-shows: going from theory to practice. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48(9):743-749.

• Williston MA, Block-Lerner J, Wolanin A, et al. Brief acceptance-based intervention for increasing intake attendance at a community mental health center. Psychol Serv. 2014;11(3):324-332.

Disclosure

Dr. Gajwani receives grant or research support from the National Institute on Mental Health, the National Institute of Drug Abuse, The Stanley Foundation, and Forest Laboratories, Inc. He is a member of the speakers’ bureau of AstraZeneca, Merck, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

1. Wyatt RJ, Henter I. An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness—1991. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30(5):213-219.

2. Wyatt RJ, Henter I, Leary MC, et al. An economic evaluation of schizophrenia—1991. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30(5);196-205.

3. Offord S, Lin J, Wong B, et al. Impact of oral antipsychotic medication adherence on healthcare resource utilization among schizophrenic patients with medicare coverage. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49(6):625-629.

4. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, et al. Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance: characteristics and outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:160- 165.

5. Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL. Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):885-889.

6. Thornley B, Adams C. Content and quality of 2000 controlled trials in schizophrenia over 50 years. BMJ. 1998;317(7167):1181-1184.

7. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):892-909.

8. Fenton WS, Blyler C, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(4):637-651.

9. Scott J, Pope M. Self-reported adherence to treatment with mood stabilizers, plasma levels, and psychiatric hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1927-1929.

10. Adams J, Scott J. Predicting medication adherence in severe mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(2):119-124.

11. Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Müser-Causemann B, Volk J. Suicides and parasuicides in a high-risk patient group on and off lithium long-term treatment. J Affect Disord. 1992;25(4):261-269.

12. Manning WG Jr, Wells KB. The effects of psychological distress and psychological well-being on use of medical services. Med Care. 1992;30(6):541-553.

13. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101-2107.

14. Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non‐adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105(3):164-172.

15. Allan AT. No-shows at a community mental health clinic: a pilot study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1988;34(1):40-46.

16. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R. Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(2):196-201.

17. Gajwani P. Improving quality of care: reducing no-show rate in ambulatory psychiatry clinic. Poster presented at: American Psychiatric Association 166th Annual Meeting; May 18-22, 2013; San Francisco, CA.

The no-show rate is high in ambulatory psychiatric clinics, especially those associated with academic medical institutions, which usually accept all public insurance providers and do not maintain a strict rule by which patients are charged a penalty when they fail to keep a scheduled appointment—a policy that, to the contrary, is customary in private practice. The University of Texas (UT) Health Sciences Center at Houston is primarily an academic medical center with resident-managed, faculty-supervised clinics that provide care to a large volume of patients.

At the UT clinics, we have struggled with a high no-show rate, and were challenged to reduce that rate. Our study of the problem, formulation and application of strategies to reduce that rate, and a discussion of our results are provided here for the benefit of psychiatric clinicians who struggle with this problem, to the detriment of their patients’ health and the financial well-being of the practice.

For patients who have a severe psychiatric illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, 60% to 70% of the direct cost of their care is attributable to inpatient services.1,2 Poor medication adherence is a critical factor: It results in exacerbation of symptoms, relapse, and hospitalization. The matter is compounded by patients’ failure to show up for scheduled follow-up appointments.

Studies show that failure to attend routinely scheduled outpatient appointments increases the risk of hospitalization. Recent research has shown that, among all causes of hospitalization, length of stay and relapse hospitalization are increased in patients with low adherence to their treatment regimen.3 Patients who miss an appointment also are more unwell and more functionally impaired—also contributing to a higher risk and rate of rehospitalization.4,5

To begin to address the problem at UT, we acknowledged that an elevated no-show rate is linked to medication nonadherence, increased risk of re-hospitalization, and increased costs associated with poor care.

Impact of nonadherence

Significant evidence supports the efficacy of antipsychotic medications for treating schizophrenia, of course,6 but that success story is undermined by the mean rate of medication nonadherence among schizophrenia patients, which can be as high as 49% in studies.7 (The actual rate might be higher because those studies do not account for persons who refuse treatment or drop out.)

Nonadherence increases the risk of relapse 3.7-fold, compared with what is seen in patients who adhere to treatment.8 Nonadherence to a medication regimen also can increase patients’ risk of engaging in assault and other dangerous behaviors, especially during periods of psychosis.8 Variables consistently associated with nonadherence include poor insight, negative attitude or subjective response toward medication, previous nonadherence, substance abuse, shorter duration of illness, inadequate discharge planning or after-care environment, and poorer therapeutic alliance.7,8

Investigation of medication adherence in bipolar disorder suggests that 1 in 3 patients fail to take at least 30% of their medication.9 In such patients, medication nonadherence can lead to mania, depression, hospital readmission, suicide, increased substance abuse, and nonresponse to treatment.10,11

Depression also is associated with an increased rate of health care utilization and severe limitation in daily functioning.12 Compared with non-depressed patients, depressed patients are 3 times more likely to be nonadherent with medical treatment recommendations.13 Estimates of medication nonadherence for unipolar and bipolar disorders range from 10% to 60% (median, 40%). This prevalence has not changed significantly with the introduction of new medications.14

Our literature review of research devoted to reducing no-shows found that few studies have explored this critical treatment concern. The no-show rate was higher among younger patients and slightly higher among women, but varied by diagnosis.15 The most common reason psychiatric patients gave for missing an appointment was “forgetting”—a response heard twice as often among no-show patients in psychiatry than in other specialties.4

Little has been tried to solve the problem. Often, community mental health centers and private practices double-book appointments. Double-booking is intended to reduce the financial burden on the practice when a patient misses an appointment. This approach fails to address nonadherence or the poor care that usually results when a patient misses regular outpatient appointments.

Several methods have been employed to improve adherence, such as electronic pill dispensing.16 Increasing medication adherence appears to be a key factor in improving quality-of-life measures in patients with schizophrenia.6

The UT project

Methods. This project was completed at the ambulatory psychiatry clinic at the UT Medical School at Houston. The clinic staff comprises residents and faculty members who provide outpatient care. During the study period, the clinic was scheduling as many as 800 office visits a month, including a mix of new and follow-up appointments. Two weeks’ retrospective data revealed a no-show rate of 31%.

For the project, we defined no-show rate as the total number of patients who missed an appointment or canceled fewer than 24 hours before the scheduled time, divided by the total number of patients scheduled that day.

Table 1 demonstrates the no-show rate calculations for 1 of the weeks preceding the start of the project. Given approximately 800 patient appointments a month, a 31% no-show rate meant that, first, 248 patients failed to receive recommended care and, second, 248 appointment slots were wasted.

Besides undermining such components of quality care as patient safety and medication compliance, the high no-show rate also harms employee morale and productivity; impairs medical education; and, possibly, increases the use of emergency and after-hour services.

We agreed that our current no-show rate of 31% was too high.

We then formed a team of residents, faculty members, therapists, front office staff, an office manager, and an office nurse. We explored and hypothesized what could be contributing to the high no-show rate (Table 2).

Several interventions were then devised and implemented:

• Patients. We increased patient education about 1) the need for regular follow-up and 2) risks associated with medication nonadherence.

• Environment. We explored environmental limitations to access and agreed that certain static factors could not be modified—eg, location of the clinic and lack of access to public transportation. We were able to make some changes to the environment (explained later) to reduce wait time.

• Staff. Some patients had complained of long wait times, which could hinder active participation in treatment. We agreed that the clinic nurse would make rounds through the waiting room every hour and talk to patients. The nurse would identify patients who had been waiting for longer than 30 minutes after their scheduled appointment time and notify the doctor accordingly. We also agreed to revise patient appointment reminder practices: instead of using an automated answering service, one of the staff members called patients personally to remind them about their appointments. (This also allowed us to update telephone numbers for many patients; numbers on record often were outdated.) We initially recruited summer interns and provided a written script to follow during calls to patients, which allowed patients to confirm, cancel, or reschedule their appointment. Once we demonstrated positive results from the change to personal calls, the department agreed to absorb the cost, and front desk personnel began making reminder calls.

• Policies and procedures. Although some practices are able to charge a small fine for missed appointments, this was not allowed at our institution. Instead, we had several departmental policies on the books, such as discharging patients from our clinics if they missed 3 consecutive appointments and limiting prescription refills to a maximum of 6 months. These policies were neither communicated to patients and staff, nor were they implemented. We decided to educate patients and staff and implement the policies.

• Transparency. We posted the no-show rate in common areas so that the team could review and follow the progression of that rate as we implemented the changes. This allowed team members to take ownership of the project and facilitated active participation.

By implementing these changes, we aimed to reduce the no-show rate to 20%.

Results. We were able to reduce the no-show rate from a documented average of 31% to an average of 12% during the study period after implementing all the proposed changes in the outpatient clinics.

We calculated the no-show rate (as shown in Table 1 for May 2013), then collected the daily no-show rate from June to September 2013 (Figure). With these calculations, we demonstrated a reduction in the no-show rate to 12%. Because of the time and effort required, we reduced data collection from daily to weekly, beginning in September.

Applying the changes required consistent effort and substantial input from various stakeholders—front desk staff, residents, the nurse, therapists, and faculty. Gradually, we were able to implement all the changes.

Keeping the no-show rate low required consistent effort and monitoring of the newly implemented procedures because even a slight change, such as failure to make reminder calls, resulted in a sudden increase in the no-show rate (that was the case in October of the study period, when we were short-staffed and could not call every patient). Patients told us that it was difficult to ignore a personal call; if they were not planning to keep the appointment, the call allowed them to reschedule on the spot.

We also made sure that current no-show rates were posted in common areas, visible to team members every day.

Discussion

We attempted a literature review of research exploring approaches to reducing the no-show rate but found few studies that explored this critical concern in patient treatment.15 Some data suggested that, in the setting studied, the no-show rate:

• was higher among younger patients (age 20 to 39) than older ones (age 60 to 79)

• was slightly higher in women than in men

• varied by diagnosis.

We found a paucity of data regarding interventions that can reduce the no-show rate.

Among the changes we made, the one that had the greatest impact was personalized appointment reminder calls, as evidenced by our patients’ reports and the increase in the no-show rate when personal calls were not made.

We also realized that, although we had several departmental policies in place regarding appointments, they were not being followed. Raising awareness among team members and their patients also was an effective deterrent to a no-show for an appointment. For example, patients were informed that 3 consecutive no-shows could lead to termination of care. Often, they reacted with surprise to this caution but also voiced a desire to improve their attendance to avoid such an outcome.

We found that establishing common operational definitions is important. It also was important to have a cohesive team, with every member agreeing on goals and changes to operational policies that needed to be implemented. Support from the department chair and the administration, we learned, is vital to the success of such an intervention.

A note about limitations. The goal of the project was limited to reducing the no-show rate. We demonstrated that this is possible among patients who have a severe mental illness, and that reducing the associated waste of time and resources can improve finances in an academic department of psychiatry. We would need additional measures, however, to quantify medication adherence and hospitalization; a larger, more inclusive project is needed to demonstrate that reducing the no-show rate reduces the symptomatic burden of psychiatric illness.

Comments in conclusion

This project was designed and conducted as a required part of a Clinical Safety and Effectiveness Program at Memorial Hermann Texas Medical Center and the UT Medical School at Houston.17 Although there was initial hesitancy about attempting to reduce the no-show rate in a chronically mentally ill population, the success of this project—indeed, it surpassed its proposed goals—demonstrates that operational changes in any clinic can reduce the no-show rate. It also is important to maintain operational changes, however; without consistent effort, desired results cannot be sustained.

Last, it is possible to replicate the methodology of this project and thereby attempt to reduce the no-show rate in other divisions of medicine that offer care to chronically ill patients, such as pediatrics and family medicine.

Bottom Line

Failure to attend routinely scheduled outpatient appointments increases a patient’s functional impairment and risk of hospitalization. Patient education, appointment reminder phone calls, revised policies and procedures, and transparency regarding the no-show rate can reduce the number of missed appointments and improve patient outcomes.

Related Resources

• Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007;13:423-434.

• Molfenter T. Reducing appointment no-shows: going from theory to practice. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48(9):743-749.

• Williston MA, Block-Lerner J, Wolanin A, et al. Brief acceptance-based intervention for increasing intake attendance at a community mental health center. Psychol Serv. 2014;11(3):324-332.

Disclosure

Dr. Gajwani receives grant or research support from the National Institute on Mental Health, the National Institute of Drug Abuse, The Stanley Foundation, and Forest Laboratories, Inc. He is a member of the speakers’ bureau of AstraZeneca, Merck, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

The no-show rate is high in ambulatory psychiatric clinics, especially those associated with academic medical institutions, which usually accept all public insurance providers and do not maintain a strict rule by which patients are charged a penalty when they fail to keep a scheduled appointment—a policy that, to the contrary, is customary in private practice. The University of Texas (UT) Health Sciences Center at Houston is primarily an academic medical center with resident-managed, faculty-supervised clinics that provide care to a large volume of patients.

At the UT clinics, we have struggled with a high no-show rate, and were challenged to reduce that rate. Our study of the problem, formulation and application of strategies to reduce that rate, and a discussion of our results are provided here for the benefit of psychiatric clinicians who struggle with this problem, to the detriment of their patients’ health and the financial well-being of the practice.

For patients who have a severe psychiatric illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, 60% to 70% of the direct cost of their care is attributable to inpatient services.1,2 Poor medication adherence is a critical factor: It results in exacerbation of symptoms, relapse, and hospitalization. The matter is compounded by patients’ failure to show up for scheduled follow-up appointments.

Studies show that failure to attend routinely scheduled outpatient appointments increases the risk of hospitalization. Recent research has shown that, among all causes of hospitalization, length of stay and relapse hospitalization are increased in patients with low adherence to their treatment regimen.3 Patients who miss an appointment also are more unwell and more functionally impaired—also contributing to a higher risk and rate of rehospitalization.4,5

To begin to address the problem at UT, we acknowledged that an elevated no-show rate is linked to medication nonadherence, increased risk of re-hospitalization, and increased costs associated with poor care.

Impact of nonadherence

Significant evidence supports the efficacy of antipsychotic medications for treating schizophrenia, of course,6 but that success story is undermined by the mean rate of medication nonadherence among schizophrenia patients, which can be as high as 49% in studies.7 (The actual rate might be higher because those studies do not account for persons who refuse treatment or drop out.)

Nonadherence increases the risk of relapse 3.7-fold, compared with what is seen in patients who adhere to treatment.8 Nonadherence to a medication regimen also can increase patients’ risk of engaging in assault and other dangerous behaviors, especially during periods of psychosis.8 Variables consistently associated with nonadherence include poor insight, negative attitude or subjective response toward medication, previous nonadherence, substance abuse, shorter duration of illness, inadequate discharge planning or after-care environment, and poorer therapeutic alliance.7,8

Investigation of medication adherence in bipolar disorder suggests that 1 in 3 patients fail to take at least 30% of their medication.9 In such patients, medication nonadherence can lead to mania, depression, hospital readmission, suicide, increased substance abuse, and nonresponse to treatment.10,11

Depression also is associated with an increased rate of health care utilization and severe limitation in daily functioning.12 Compared with non-depressed patients, depressed patients are 3 times more likely to be nonadherent with medical treatment recommendations.13 Estimates of medication nonadherence for unipolar and bipolar disorders range from 10% to 60% (median, 40%). This prevalence has not changed significantly with the introduction of new medications.14

Our literature review of research devoted to reducing no-shows found that few studies have explored this critical treatment concern. The no-show rate was higher among younger patients and slightly higher among women, but varied by diagnosis.15 The most common reason psychiatric patients gave for missing an appointment was “forgetting”—a response heard twice as often among no-show patients in psychiatry than in other specialties.4

Little has been tried to solve the problem. Often, community mental health centers and private practices double-book appointments. Double-booking is intended to reduce the financial burden on the practice when a patient misses an appointment. This approach fails to address nonadherence or the poor care that usually results when a patient misses regular outpatient appointments.

Several methods have been employed to improve adherence, such as electronic pill dispensing.16 Increasing medication adherence appears to be a key factor in improving quality-of-life measures in patients with schizophrenia.6

The UT project

Methods. This project was completed at the ambulatory psychiatry clinic at the UT Medical School at Houston. The clinic staff comprises residents and faculty members who provide outpatient care. During the study period, the clinic was scheduling as many as 800 office visits a month, including a mix of new and follow-up appointments. Two weeks’ retrospective data revealed a no-show rate of 31%.

For the project, we defined no-show rate as the total number of patients who missed an appointment or canceled fewer than 24 hours before the scheduled time, divided by the total number of patients scheduled that day.

Table 1 demonstrates the no-show rate calculations for 1 of the weeks preceding the start of the project. Given approximately 800 patient appointments a month, a 31% no-show rate meant that, first, 248 patients failed to receive recommended care and, second, 248 appointment slots were wasted.

Besides undermining such components of quality care as patient safety and medication compliance, the high no-show rate also harms employee morale and productivity; impairs medical education; and, possibly, increases the use of emergency and after-hour services.

We agreed that our current no-show rate of 31% was too high.

We then formed a team of residents, faculty members, therapists, front office staff, an office manager, and an office nurse. We explored and hypothesized what could be contributing to the high no-show rate (Table 2).

Several interventions were then devised and implemented:

• Patients. We increased patient education about 1) the need for regular follow-up and 2) risks associated with medication nonadherence.

• Environment. We explored environmental limitations to access and agreed that certain static factors could not be modified—eg, location of the clinic and lack of access to public transportation. We were able to make some changes to the environment (explained later) to reduce wait time.

• Staff. Some patients had complained of long wait times, which could hinder active participation in treatment. We agreed that the clinic nurse would make rounds through the waiting room every hour and talk to patients. The nurse would identify patients who had been waiting for longer than 30 minutes after their scheduled appointment time and notify the doctor accordingly. We also agreed to revise patient appointment reminder practices: instead of using an automated answering service, one of the staff members called patients personally to remind them about their appointments. (This also allowed us to update telephone numbers for many patients; numbers on record often were outdated.) We initially recruited summer interns and provided a written script to follow during calls to patients, which allowed patients to confirm, cancel, or reschedule their appointment. Once we demonstrated positive results from the change to personal calls, the department agreed to absorb the cost, and front desk personnel began making reminder calls.

• Policies and procedures. Although some practices are able to charge a small fine for missed appointments, this was not allowed at our institution. Instead, we had several departmental policies on the books, such as discharging patients from our clinics if they missed 3 consecutive appointments and limiting prescription refills to a maximum of 6 months. These policies were neither communicated to patients and staff, nor were they implemented. We decided to educate patients and staff and implement the policies.

• Transparency. We posted the no-show rate in common areas so that the team could review and follow the progression of that rate as we implemented the changes. This allowed team members to take ownership of the project and facilitated active participation.

By implementing these changes, we aimed to reduce the no-show rate to 20%.

Results. We were able to reduce the no-show rate from a documented average of 31% to an average of 12% during the study period after implementing all the proposed changes in the outpatient clinics.

We calculated the no-show rate (as shown in Table 1 for May 2013), then collected the daily no-show rate from June to September 2013 (Figure). With these calculations, we demonstrated a reduction in the no-show rate to 12%. Because of the time and effort required, we reduced data collection from daily to weekly, beginning in September.

Applying the changes required consistent effort and substantial input from various stakeholders—front desk staff, residents, the nurse, therapists, and faculty. Gradually, we were able to implement all the changes.

Keeping the no-show rate low required consistent effort and monitoring of the newly implemented procedures because even a slight change, such as failure to make reminder calls, resulted in a sudden increase in the no-show rate (that was the case in October of the study period, when we were short-staffed and could not call every patient). Patients told us that it was difficult to ignore a personal call; if they were not planning to keep the appointment, the call allowed them to reschedule on the spot.

We also made sure that current no-show rates were posted in common areas, visible to team members every day.

Discussion

We attempted a literature review of research exploring approaches to reducing the no-show rate but found few studies that explored this critical concern in patient treatment.15 Some data suggested that, in the setting studied, the no-show rate:

• was higher among younger patients (age 20 to 39) than older ones (age 60 to 79)

• was slightly higher in women than in men

• varied by diagnosis.

We found a paucity of data regarding interventions that can reduce the no-show rate.

Among the changes we made, the one that had the greatest impact was personalized appointment reminder calls, as evidenced by our patients’ reports and the increase in the no-show rate when personal calls were not made.

We also realized that, although we had several departmental policies in place regarding appointments, they were not being followed. Raising awareness among team members and their patients also was an effective deterrent to a no-show for an appointment. For example, patients were informed that 3 consecutive no-shows could lead to termination of care. Often, they reacted with surprise to this caution but also voiced a desire to improve their attendance to avoid such an outcome.

We found that establishing common operational definitions is important. It also was important to have a cohesive team, with every member agreeing on goals and changes to operational policies that needed to be implemented. Support from the department chair and the administration, we learned, is vital to the success of such an intervention.

A note about limitations. The goal of the project was limited to reducing the no-show rate. We demonstrated that this is possible among patients who have a severe mental illness, and that reducing the associated waste of time and resources can improve finances in an academic department of psychiatry. We would need additional measures, however, to quantify medication adherence and hospitalization; a larger, more inclusive project is needed to demonstrate that reducing the no-show rate reduces the symptomatic burden of psychiatric illness.

Comments in conclusion

This project was designed and conducted as a required part of a Clinical Safety and Effectiveness Program at Memorial Hermann Texas Medical Center and the UT Medical School at Houston.17 Although there was initial hesitancy about attempting to reduce the no-show rate in a chronically mentally ill population, the success of this project—indeed, it surpassed its proposed goals—demonstrates that operational changes in any clinic can reduce the no-show rate. It also is important to maintain operational changes, however; without consistent effort, desired results cannot be sustained.

Last, it is possible to replicate the methodology of this project and thereby attempt to reduce the no-show rate in other divisions of medicine that offer care to chronically ill patients, such as pediatrics and family medicine.

Bottom Line

Failure to attend routinely scheduled outpatient appointments increases a patient’s functional impairment and risk of hospitalization. Patient education, appointment reminder phone calls, revised policies and procedures, and transparency regarding the no-show rate can reduce the number of missed appointments and improve patient outcomes.

Related Resources

• Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007;13:423-434.

• Molfenter T. Reducing appointment no-shows: going from theory to practice. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48(9):743-749.

• Williston MA, Block-Lerner J, Wolanin A, et al. Brief acceptance-based intervention for increasing intake attendance at a community mental health center. Psychol Serv. 2014;11(3):324-332.

Disclosure

Dr. Gajwani receives grant or research support from the National Institute on Mental Health, the National Institute of Drug Abuse, The Stanley Foundation, and Forest Laboratories, Inc. He is a member of the speakers’ bureau of AstraZeneca, Merck, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

1. Wyatt RJ, Henter I. An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness—1991. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30(5):213-219.

2. Wyatt RJ, Henter I, Leary MC, et al. An economic evaluation of schizophrenia—1991. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30(5);196-205.

3. Offord S, Lin J, Wong B, et al. Impact of oral antipsychotic medication adherence on healthcare resource utilization among schizophrenic patients with medicare coverage. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49(6):625-629.

4. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, et al. Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance: characteristics and outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:160- 165.

5. Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL. Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):885-889.

6. Thornley B, Adams C. Content and quality of 2000 controlled trials in schizophrenia over 50 years. BMJ. 1998;317(7167):1181-1184.

7. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):892-909.

8. Fenton WS, Blyler C, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(4):637-651.

9. Scott J, Pope M. Self-reported adherence to treatment with mood stabilizers, plasma levels, and psychiatric hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1927-1929.

10. Adams J, Scott J. Predicting medication adherence in severe mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(2):119-124.

11. Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Müser-Causemann B, Volk J. Suicides and parasuicides in a high-risk patient group on and off lithium long-term treatment. J Affect Disord. 1992;25(4):261-269.

12. Manning WG Jr, Wells KB. The effects of psychological distress and psychological well-being on use of medical services. Med Care. 1992;30(6):541-553.

13. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101-2107.

14. Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non‐adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105(3):164-172.

15. Allan AT. No-shows at a community mental health clinic: a pilot study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1988;34(1):40-46.

16. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R. Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(2):196-201.

17. Gajwani P. Improving quality of care: reducing no-show rate in ambulatory psychiatry clinic. Poster presented at: American Psychiatric Association 166th Annual Meeting; May 18-22, 2013; San Francisco, CA.

1. Wyatt RJ, Henter I. An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness—1991. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30(5):213-219.

2. Wyatt RJ, Henter I, Leary MC, et al. An economic evaluation of schizophrenia—1991. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30(5);196-205.

3. Offord S, Lin J, Wong B, et al. Impact of oral antipsychotic medication adherence on healthcare resource utilization among schizophrenic patients with medicare coverage. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49(6):625-629.

4. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, et al. Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance: characteristics and outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:160- 165.

5. Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL. Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):885-889.

6. Thornley B, Adams C. Content and quality of 2000 controlled trials in schizophrenia over 50 years. BMJ. 1998;317(7167):1181-1184.

7. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):892-909.

8. Fenton WS, Blyler C, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(4):637-651.

9. Scott J, Pope M. Self-reported adherence to treatment with mood stabilizers, plasma levels, and psychiatric hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1927-1929.

10. Adams J, Scott J. Predicting medication adherence in severe mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(2):119-124.

11. Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Müser-Causemann B, Volk J. Suicides and parasuicides in a high-risk patient group on and off lithium long-term treatment. J Affect Disord. 1992;25(4):261-269.

12. Manning WG Jr, Wells KB. The effects of psychological distress and psychological well-being on use of medical services. Med Care. 1992;30(6):541-553.

13. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101-2107.

14. Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non‐adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105(3):164-172.

15. Allan AT. No-shows at a community mental health clinic: a pilot study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1988;34(1):40-46.

16. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R. Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(2):196-201.

17. Gajwani P. Improving quality of care: reducing no-show rate in ambulatory psychiatry clinic. Poster presented at: American Psychiatric Association 166th Annual Meeting; May 18-22, 2013; San Francisco, CA.