User login

CE/CME No: CR-13111

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Explain the difference between indirect and direct screening methods for CRC and when to utilize each.

• Understand the age continuum of screening patients with and without increased risk factors for CRC.

• Decide which type of direct screening method is the best choice when looking at sensitivity and specificity and patient preference.

• Understand the risks, benefits, and limitations of each procedure available for CRC screening.

FACULTY

Carolyn Mueller, Molly Perry, and Lisa DeCicco are recent graduates of the Pace University–Lenox Hill Hospital Physician Assistant Program in New York. Ellen D. Mandel is a Clinical Professor in the Pace PA Program and an Associate Professor in the PA Program at Seton Hall University, South Orange, New Jersey.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Because colorectal cancer is often asymptomatic, routine screening is essential to detect lesions at an early stage. The evolution of health care has brought new and improved screening methods for colorectal cancer, including CT colonography. This article weighs the pros and cons of the available screening methods used to detect colorectal cancer in the general population today.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second-leading cause of death from cancer in Europe and the United States and the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in both men and women in the US.1-5 According to the American Cancer Society, 102,480 new cases of colon cancer and 40,340 new cases of rectal cancer will be diagnosed in 2013.5 Although screening rates remain low and the incidence of new CRC diagnoses rises annually, mortality rates are decreasing, most likely due to screening and improved treatment.5

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF COLORECTAL CANCER

CRC is often asymptomatic until it reaches an advanced stage. At this point, symptoms include weight loss, night sweats, fever, loss of appetite, blood in the stool, pencil-shaped stools, diarrhea, constipation, anemia, and/or dizzy spells.6,7 On abdominal exam, a clinician may note dullness to percussion over the right or left lower quadrant, palpate a mass in the right or left lower quadrant, and/or elicit tenderness or guarding upon deep palpation. The clinician may be inclined to do a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) to confirm active GI bleeding.1,3

CURRENT SCREENING RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) currently recommends that screening for CRC—with FOBT, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy—start at age 50 and continue through age 75.8 For patients whose first-degree relative has a history of CRC, initial screening should start at age 40.

It is recommended that people ages 76 to 85 make personalized, informed screening decisions in conjunction with their medical provider. Patients ages 85 or older should not be screened for CRC because of the estimated five-year time frame between the detection of cancer and the onset of symptoms or death. In the unlikely circumstance that the patient is screened and a lesion is found, the patient would not benefit but most likely experience harm from treatment efforts; however, this should be decided on a case-by-case basis.8

CONSIDERATIONS IN SCREENING THE ELDERLY

Much of the data on older populations are outdated, and thus more research needs to be conducted in this population. However, data from two studies dating from 2006 provide tools to help clinicians decide if screening in the older population is beneficial.

One study of the benefit of screening for CRC in the older population stated that clinicians must assess both the burden of chronic illness and the patient’s age as part of their evaluation. This study concluded that, because of the risks and costs that are associated with CRC screening, it is important to identify only those individuals who are likely to benefit from screening, rather than screening the elderly population in general.9

Another study examined the benefit of screening colonoscopy in two elderly groups (ages 75 to 79 and age ≥ 80) versus younger patients (ages 50 to 54; the control group). It was found that

• Screening in the older population may increase the risk for perforation and respiratory depression secondary to sedation,

• Screening may take longer to complete, and

• Screening may be challenging with less successful bowel preparation.10

Further, the prevalence of neoplasia was lowest in the control group (13.8%) compared to the 75-to-79-year-old (26.5%) and oldest (≥ 80; 28.6%) groups. The mean extension of life expectancy was much lower in the oldest group, compared to the control group (0.13 years versus 0.85 years), which represents a 6.5-fold difference. These results suggest that the benefit of colonoscopy screening in elderly persons ages 76 and older results in smaller gains in life expectancy and does not outweigh the risks. This test, therefore, should only be used when the patient expresses a preference for colonoscopy and the clinician feels it will significantly benefit the patient.10

On the next page: Screening methods >>

SCREENING METHODS

Current screening methods for CRC can be divided into two distinct categories: indirect and direct.1 Indirect screening tests include FOBT, fecal immunochemical testing, and stool DNA testing. Cancers are identified by detection of byproducts in the patient’s stool, such as blood or epithelial cells containing DNA of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene. These tests are simple to perform, have high specificity, and are relatively inexpensive, but they need to be repeated annually and have poor sensitivity.1 Positive test results of indirect screening often warrant further diagnostic testing, ultimately utilizing one of the direct screening methods.

Direct screening methods used to detect CRC—from least to most frequently employed—include barium enema (BE), CT colonography (CTC), and colonoscopy. Another direct method, flexible sigmoidoscopy, is not frequently used today, and when used, serves only as an intermediate step to colonoscopy. Direct screening provides visualization of the contour of the colon wall, the internal mucosa, and abnormal architecture. It is important to keep in mind that these tests require that the patient adhere to pretest preparation, may require patient sedation, and are more invasive and costly than indirect tests.1

Although the USPSTF has established recommendations for both test types, questions still remain about what constitutes the most cost-effective and accurate combination of screening tests for detecting CRC.8

On the next page: Barium enema >>

BARIUM ENEMA

Procedure

The BE, also known as a lower GI series, was the first screening test to allow the clinician to identify polyps or masses as outlined by barium sulfate.3 This test requires the patient to lie in an oblique position on his/her left side while barium sulfate (known as single-contrast BE, or SCBE), sometimes followed by air (known as double-contrast BE, or DCBE), is flowed through a tube inserted into the rectum. As the colon fills, the radiologist takes multiple overhead x-ray images. The patient is then required to roll on the table several times, causing the barium to coat the entire mucosa of the colon and rectum, which allows for visualization from various angles (see Figure 1).11

Patient Experience

Screening with the BE has some disadvantages to the patient. Patients may experience discomfort at multiple points: during the instillation of gas and barium into the colon, during the maintenance of the gas and barium levels, and during the maneuvering and holding positions of the procedure itself.2 Some patients, interviewed after a BE was performed, indicated feeling embarrassed during the procedure.6 Although the ability to evaluate images during the exam allows the radiologist to share preliminary results with the patient, the immediate disclosure of bad news is deemed somewhat inappropriate. If the procedure reveals positive findings, the radiologist must be sure to speak with the patient in a private area after the procedure. The patient is in a vulnerable state while in the exam room, and the exam room staff may not be adequately equipped to handle the emotional impact, properly address patient questions, or provide counseling.2,6

Advantages and Disadvantages

Few studies are now being done on the advantages and disadvantages of performing a BE compared to a colonoscopy or CTC—most likely due to the belief that colonoscopy is the better choice. BEs are considered to be one of the safer of the direct screening tests for CRC because sedation is not required and, compared to colonoscopy, the rate of colon perforation is lower (0.02% to 0.04% for BE versus 0.016% to 0.2% for colonoscopy).12,13

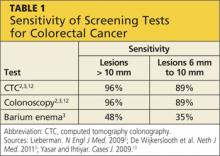

In a small study of 15 asymptomatic men age 71, it was found that BEs have a lower sensitivity for detecting CRC as compared with colonoscopy or CTC.2 Sensitivity for lesions ≥ 10 mm is only 48% and for lesions ≥ 6 mm is only 35%, proving the BE to be a highly ineffective screening test for CRC (see Table 1).3

In a randomized study of 5,025 symptomatic patients with abnormal bowel movements and/or abdominal pain, BE has a detection rate of only 5% compared to the much higher sensitivity of CTC or colonoscopy.14

A third study calls attention to the risks associated with the DCBE exam, noting that it is less invasive and less dangerous than colonoscopy, as it does not require sedation and poses less risk for perforation of the lining of the colon.15 The study authors concluded that DCBE has a high sensitivity for clinically significant neoplasms (> 6 mm) but not for small polyps, which may be captured with other tests. DCBE may also supplement incomplete colonoscopy to rule out obstruction.

However, because of the loss of biopsy capabilities, further testing is required when abnormalities are found during the DCBE, diminishing the potential cost effectiveness of the exam. The study authors suggested that DCBEs may be used to screen those who are asymptomatic and seem to have minimal risk factors.15

Limitations

Limitations to successful BE screening include patient compliance and test result interpretation skills. With interpretation skills declining due to limited training of professionals to read BEs, results are becoming less accurate, and the test itself can be seen as less reliable. BEs are less popular, and therefore skills in reading the films are becoming outdated.2 If BE screening is to be used as the primary direct screening tool for CRC, it is imperative that radiologists and gastroenterology physicians and clinicians be well trained in this GI procedure.

Also, patients undergoing BE absorb about 15 mGy of radiation per procedure, versus 0.01 mGy to 0.15 mGy absorbed with a typical chest x-ray.16 For patients with a history of increased radiation exposure or if radiation exposure is a major concern of the patient, BE may not be an appropriate first choice.

On the next page: Colonoscopy >>

COLONOSCOPY

Colonoscopy is an endoscopic technique that allows internal inspection of the entire colorectal tract (see Figure 2).3 Although the most invasive of the exams being reviewed (and requiring extensive bowel prep), it is the gold standard for CRC screening.3

Current literature indicates that colonoscopy should be the screening method of choice for patients who have symptoms of colorectal cancer, positive results with an indirect screening exam such as FOBT, or who fall within a high-risk category. Persons at high risk for CRC include those with a significant family history, persons ages 50 and older, African Americans, and persons with an intestinal inflammatory condition, diabetes mellitus, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, positive smoking status, and low-fiber/high-fat diet.

Procedure

This procedure is performed on an outpatient basis; bowel prep is required one day prior to the procedure so that the bowel movements are clear of fecal matter. The patient receives short-lasting sedation, such as midazolam, via an IV line prior to being brought into the exam room. The procedure itself can take up to 30 minutes, with the patient comfortably sedated in an oblique position. The patient is allowed to recover for several hours, or until awake and able to pass flatus.

Patient Experience

The patient may experience discomfort during the bowel prep phase, as with BE preparation. The patient may be uncomfortable during insertion and manipulation of the colonoscope and also with gaseous insufflation that is used to improve visualization.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The advantages of colonoscopy over the other direct methods are the ability to immediately remove early cancer and colonic polyps and the ability to obtain histologic samples. A suspicious mass can be biopsied during the procedure and, depending on the size, may be completely excised. The histology of the biopsied tissue samples can aid in determining need for further treatment or establish an appropriate surveillance interval for the patient.3

The disadvantages of colonoscopy are related to the possible complications of the procedure, including colon perforation and postpolypectomy bleeding. The risk for these events is estimated to be between 0.1% and 0.3%.3 In addition, the short-lasting sedation that is used during the procedure poses the risk for possible respiratory collapse.6 Therefore, each patient requires medical clearance prior to administering sedation. The risk for a serious adverse event is 3 to 5 per 1,000 colonoscopies, and procedure-related mortality, while rare, has been reported.2,4,14

Limitations

Studies have found colonoscopy to be the most expensive of the direct screening tests, which may pose a problem for uninsured or underinsured patients.4,14

A collection of colonoscopy studies done on patients ages 50 to 66 showed an adenoma miss rate of 20% to 26% for any adenoma < 10 mm, and a 2.1% miss rate for adenomas ≥ 10 mm.3 Adenoma detection rates are dependent on optimal bowel preparation, complete examination of the colon, and the time the clinician spends examining all surfaces of the colon mucosa when withdrawing the colonoscope.3

Colonoscopy has the lowest adherence rate of all the CRC screening tests, which is not surprising since it is invasive, involves sedation, and requires thorough preparation. However, colonoscopies may be performed at longer intervals (up to 10 years) compared to other screening tests; the risk for developing CRC after a negative colonoscopy exam remains low.3

On the next page: CT colonography >>

CT COLONOGRAPHY

CTC is an emerging CRC screening test that is also known as virtual colonoscopy. According to available studies, CTC and colonoscopy might be equivalent for diagnosing cancer.14

Procedure

The preparation for CTC requires the patient to consume a low-residue diet one day prior to the procedure, which is considered to be an advantage over colonoscopy due to the decreased bowel preparation.3 With this procedure, a small rectal catheter is inserted into the anus and advanced to the rectum to allow carbon dioxide to be instilled for bowel insufflation. The patient lies supine on the table for a CT scan of the abdomen with the resulting 2D images visualizing polyps and CRC, if present.3 If necessary, 3D images can be compiled by a specialized software program to obtain a 360-degree view of the colon. In fact, recent studies show that 3D CTC is preferred to 2D because 3D polyp measurements are more representative of the true polyp size found on optic colonoscopy or surgery than are 2D measurements.17

Patient Experience

In one study, CTC screening was described as uncomfortable but not painful and was reported to be the most impersonal of all three tests because of less direct interaction, reducing patient embarrassment. This study reviewed qualitative interviews with patients regarding the fairly new CTC procedure and found that patients received little visual or verbal feedback and were confused regarding their test outcome immediately after the procedure.6

CTC was preferred by 72% of patients compared to colonoscopy and by 97% of patients compared to DCBE.18 In a study that evaluated the performance characteristics of CTC among 1,233 asymptomatic patients, 68% deemed CTC to be more convenient than colonoscopy, and more patients indicated that they preferred CTC over colonoscopy for screening (49.8% vs 41.1%; 9.2% had no preference).19

Advantages and Disadvantages

Compared with colonoscopy, CTC is comparably sensitive but safer and more acceptable to patients.2,6,14 CTC has a sensitivity of 96% for detecting lesions > 10 mm in diameter, but sensitivity decreases to 89% for lesions 6 mm to 10 mm in diameter (see Table 1).2,3,14

The follow-up screening intervals for CTC parallel those of colonoscopy. In a recent audit of 1,011 screening participants with a negative baseline CTC, a single carcinoma occurred during an average follow-up period of 4.73 ± 1.15 years.1

The current Colonography Reporting and Data System (C-RADS) guidelines for CTC interpretation recommend 6 mm as the minimum size for polyp reporting.17 This reporting threshold will result in a 77% reduction rate in invasive endoscopic procedures since it minimizes the number of cases that are sent for colonoscopy after CTC screening.17

A study performed by the American College of Radiology Imaging Network found there would be an approximate 12% referral rate for colonoscopy when using the current 6-mm polyp size threshold, but the referral rate would increase to 17% if a 5-mm threshold were used.17 The American Gastroenterological Association has stated that diminutive lesions—those measuring ≤ 5 mm—are of little to no clinical significance because only a fraction of them are neoplastic. Of these, fewer than 1% are histologically advanced, and essentially none are malignant.6 By not reporting diminutive lesions, there would be an incremental gain in the cost-effectiveness of the CTC scan and only a 1.3% loss in clinical CRC prevention efficacy.

It is widely accepted that any polyp ≥ 10 mm detected with CTC screening indicates a need for polypectomy via colonoscopy or surgery.20 For lesions ranging from 6.1 mm to 9.9 mm in diameter, CTC is suggested as a surveillance tool; patients may receive repeat CTC every 1 to 3 years until resection via colonoscopy is warranted.17

Limitations

CTC screening has many limitations, and evidence is lacking for a reduction of CRC incidence or mortality after CTC. Research has revealed a discrepancy between the polyp size measured by CTC versus the true polyp size seen on optic colonoscopy; CTC measurement can underestimate the size of a polyp by nearly 1.2 mm. Considering that C-RADS level 2 includes polyps 6.1 to 9.9 mm and level 3 includes polyps ≥ 10 mm, which automatically requires further investigation with colonoscopy, such a 1.2-mm discrepancy in measurement can make all the difference.17

CTC requires some bowel preparation, special resources, and expertise. The cost-effectiveness and risk profiles will vary, depending on whether referral for colonoscopy is required. Also, treatment recommendations for patients with polyps < 6 mm in diameter are uncertain.

CTC screening exposes the patient to increased amounts of ionizing radiation, which raises concern regarding risk for radiation-induced cancers. The effective dose to the whole body during a CTC is 6 to 20 mSv, compared to 0.02 mSv for a chest x-ray.16 One study estimated that performing CTC screening every five years from ages 50 to 80 would prevent the development of 24 CRC cases for every one radiation-induced cancer.21 Thus, the risks of radiation must be weighed against the benefits of screening, and the decision is often made by the individual patient.

Finally, the greatest limitation of CTC is that further testing may be required based on the preliminary results. Therefore, the patient may undergo two procedures rather than just one all-inclusive procedure, such as colonoscopy.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

CRC is the second leading cause of death from cancer among men and women in the United States despite the fact that it is largely preventable through diagnostic screening. Patients need education about the different types of CRC screening and about which method may be best for them, given their preferences, family history, personal history, age, and symptoms. All screening tests, direct or indirect, are cost-effective compared with no screening at all.20 Regardless of current recommendations, any screening that the patient is comfortable with should be encouraged.

BE was the first diagnostic tool to provide clinicians with the ability to visualize the patient’s lower gastrointestinal tract. It is becoming technologically outdated, however, and is no longer accepted as a primary diagnostic tool for CRC screening.

Colonoscopy, the most expensive direct screening test, provides complete visualization of the colon and allows for immediate biopsy and possible resection of a suspicious mass. This procedure is the most cost-effective direct screening method because it is comprehensive compared to BE and CTC, which may result in further investigation via colonoscopy if a mass is identified. Although colonoscopy is the most specific and sensitive for CRC screening, the outcome of the test strongly correlates with patient compliance with bowel preparation as well as clinician experience and expertise in performing a thorough exam.

While most US guidelines recommend colonoscopy as the gold standard diagnostic test, CTC is a reliable alternative for those patients who refuse colonoscopy. Future research on this newer method should consider altering the C-RADS threshold that necessitates follow-up with colonoscopy to account for the variation in polyp measurement. CTC is not a stand-alone replacement for the other direct CRC screening tests but is useful as an adjunct to increase overall patient compliance. Perhaps with time, this test may evolve to be a more prevailing recommendation for the preventive screening of CRC.

1. de Haan MC, Halligan S, Stoker J. Does CT colonography have a role for population-based colorectal cancer CRC screening? Eur Radiol. 2012;22: 1495-1503.

2. Lieberman D. Screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361: 1179-1187.

3. de Wijkerslooth TR, Bossuyt PM, Dekker E. Strategies in screening for colon carcinoma. Neth J Med. 2011;69:112-119.

4. Whitlock E, Lin J, Liles E, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: an updated systematic review. Evidence Synthesis No. 65, Part 1. AHRQ Publication No. 08-05124-EF-1. Rockville, Maryland, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, October 2008.

5. Colorectal cancer: What are the key statistics about colorectal cancer? American Cancer Society. www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/detailedguide/colorectal-cancer-key-statistics. Accessed October 14, 2013.

6. Von Wagner C, Knight K, Halligan S, et al. Patient experiences of colonoscopy, barium enema and CT colonography: a qualitative study. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:13-19.

7. Cappell MS. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and management of colon cancer. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2008;37:1-24.

8. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. US Preventive Services Task Force web site. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscolo.htm. Published 2008. Accessed October 14, 2013.

9. Gross CP, McAvay GJ, Krumholz HM, et al. The effect of age and chronic illness on life expectancy after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer: implications for screening. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:646-653.

10. Lin OS, Kozarek RA, Schembre DB, et al. Screening colonoscopy in very elderly patients: prevalence of neoplasia and estimated impact on life expectancy. JAMA. 2006;295:2357-2365.

11. Colorectal cancer early detection: colorectal cancer screening tests. American Cancer Society. www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/moreinformation/colonandrectumcancerearlydetection/colorectal-cancer-early-detection-screening-tests-used. Accessed October 14, 2013.

12. Lohsiriwat V. Colonoscopic perforation: incidence, risk factors, management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:425-430.

13. Yasar NF, Ihtiyar E. Colonic perforation during barium enema in a patient without known colonic disease: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:6716.

14. Halligan S, Lilford RJ, Wardle J, et al. Design of a multicentre randomized trial to evaluate CT colonography versus colonoscopy or barium enema for diagnosis of colonic cancer in older symptomatic patients: The SIGGAR study. Trials. 2007;8:1-9.

15. Lohsiriwat V, Prapasrivorakul S, Suthikeeree W. Colorectal cancer screening by double contrast barium enema in Thai people.Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:1273-1276.

16. Mayo JR, Aldrich J, Muller NL; Fleischner Society. Radiation exposure at chest CT: a statement of the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2003;228:15-21.

17. Summers RM. Polyp size measurement at CT colonography: what do we know and what do we need to know? Radiology. 2010;255(3):707-720.

18. Gluecker TM, Johnson CD, Harmsen WS, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with CT colonography, colonoscopy, and double-contrast barium enema examination: prospective assessment of patient perceptions and p. Radiology. 2003;227:378-384.

19. Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2191-2200.

20. Pickhardt P, Hassan C, Laghi A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening with computed tomography colonography. Cancer. 2007;109:2213-2221.

21. Berrington de Gonzalez A, Kim KP, Knudsen AB, et al. Radiation-related cancer risks from CT colongraphy screening: a risk-benefit analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:816-823.

CE/CME No: CR-13111

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Explain the difference between indirect and direct screening methods for CRC and when to utilize each.

• Understand the age continuum of screening patients with and without increased risk factors for CRC.

• Decide which type of direct screening method is the best choice when looking at sensitivity and specificity and patient preference.

• Understand the risks, benefits, and limitations of each procedure available for CRC screening.

FACULTY

Carolyn Mueller, Molly Perry, and Lisa DeCicco are recent graduates of the Pace University–Lenox Hill Hospital Physician Assistant Program in New York. Ellen D. Mandel is a Clinical Professor in the Pace PA Program and an Associate Professor in the PA Program at Seton Hall University, South Orange, New Jersey.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Because colorectal cancer is often asymptomatic, routine screening is essential to detect lesions at an early stage. The evolution of health care has brought new and improved screening methods for colorectal cancer, including CT colonography. This article weighs the pros and cons of the available screening methods used to detect colorectal cancer in the general population today.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second-leading cause of death from cancer in Europe and the United States and the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in both men and women in the US.1-5 According to the American Cancer Society, 102,480 new cases of colon cancer and 40,340 new cases of rectal cancer will be diagnosed in 2013.5 Although screening rates remain low and the incidence of new CRC diagnoses rises annually, mortality rates are decreasing, most likely due to screening and improved treatment.5

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF COLORECTAL CANCER

CRC is often asymptomatic until it reaches an advanced stage. At this point, symptoms include weight loss, night sweats, fever, loss of appetite, blood in the stool, pencil-shaped stools, diarrhea, constipation, anemia, and/or dizzy spells.6,7 On abdominal exam, a clinician may note dullness to percussion over the right or left lower quadrant, palpate a mass in the right or left lower quadrant, and/or elicit tenderness or guarding upon deep palpation. The clinician may be inclined to do a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) to confirm active GI bleeding.1,3

CURRENT SCREENING RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) currently recommends that screening for CRC—with FOBT, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy—start at age 50 and continue through age 75.8 For patients whose first-degree relative has a history of CRC, initial screening should start at age 40.

It is recommended that people ages 76 to 85 make personalized, informed screening decisions in conjunction with their medical provider. Patients ages 85 or older should not be screened for CRC because of the estimated five-year time frame between the detection of cancer and the onset of symptoms or death. In the unlikely circumstance that the patient is screened and a lesion is found, the patient would not benefit but most likely experience harm from treatment efforts; however, this should be decided on a case-by-case basis.8

CONSIDERATIONS IN SCREENING THE ELDERLY

Much of the data on older populations are outdated, and thus more research needs to be conducted in this population. However, data from two studies dating from 2006 provide tools to help clinicians decide if screening in the older population is beneficial.

One study of the benefit of screening for CRC in the older population stated that clinicians must assess both the burden of chronic illness and the patient’s age as part of their evaluation. This study concluded that, because of the risks and costs that are associated with CRC screening, it is important to identify only those individuals who are likely to benefit from screening, rather than screening the elderly population in general.9

Another study examined the benefit of screening colonoscopy in two elderly groups (ages 75 to 79 and age ≥ 80) versus younger patients (ages 50 to 54; the control group). It was found that

• Screening in the older population may increase the risk for perforation and respiratory depression secondary to sedation,

• Screening may take longer to complete, and

• Screening may be challenging with less successful bowel preparation.10

Further, the prevalence of neoplasia was lowest in the control group (13.8%) compared to the 75-to-79-year-old (26.5%) and oldest (≥ 80; 28.6%) groups. The mean extension of life expectancy was much lower in the oldest group, compared to the control group (0.13 years versus 0.85 years), which represents a 6.5-fold difference. These results suggest that the benefit of colonoscopy screening in elderly persons ages 76 and older results in smaller gains in life expectancy and does not outweigh the risks. This test, therefore, should only be used when the patient expresses a preference for colonoscopy and the clinician feels it will significantly benefit the patient.10

On the next page: Screening methods >>

SCREENING METHODS

Current screening methods for CRC can be divided into two distinct categories: indirect and direct.1 Indirect screening tests include FOBT, fecal immunochemical testing, and stool DNA testing. Cancers are identified by detection of byproducts in the patient’s stool, such as blood or epithelial cells containing DNA of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene. These tests are simple to perform, have high specificity, and are relatively inexpensive, but they need to be repeated annually and have poor sensitivity.1 Positive test results of indirect screening often warrant further diagnostic testing, ultimately utilizing one of the direct screening methods.

Direct screening methods used to detect CRC—from least to most frequently employed—include barium enema (BE), CT colonography (CTC), and colonoscopy. Another direct method, flexible sigmoidoscopy, is not frequently used today, and when used, serves only as an intermediate step to colonoscopy. Direct screening provides visualization of the contour of the colon wall, the internal mucosa, and abnormal architecture. It is important to keep in mind that these tests require that the patient adhere to pretest preparation, may require patient sedation, and are more invasive and costly than indirect tests.1

Although the USPSTF has established recommendations for both test types, questions still remain about what constitutes the most cost-effective and accurate combination of screening tests for detecting CRC.8

On the next page: Barium enema >>

BARIUM ENEMA

Procedure

The BE, also known as a lower GI series, was the first screening test to allow the clinician to identify polyps or masses as outlined by barium sulfate.3 This test requires the patient to lie in an oblique position on his/her left side while barium sulfate (known as single-contrast BE, or SCBE), sometimes followed by air (known as double-contrast BE, or DCBE), is flowed through a tube inserted into the rectum. As the colon fills, the radiologist takes multiple overhead x-ray images. The patient is then required to roll on the table several times, causing the barium to coat the entire mucosa of the colon and rectum, which allows for visualization from various angles (see Figure 1).11

Patient Experience

Screening with the BE has some disadvantages to the patient. Patients may experience discomfort at multiple points: during the instillation of gas and barium into the colon, during the maintenance of the gas and barium levels, and during the maneuvering and holding positions of the procedure itself.2 Some patients, interviewed after a BE was performed, indicated feeling embarrassed during the procedure.6 Although the ability to evaluate images during the exam allows the radiologist to share preliminary results with the patient, the immediate disclosure of bad news is deemed somewhat inappropriate. If the procedure reveals positive findings, the radiologist must be sure to speak with the patient in a private area after the procedure. The patient is in a vulnerable state while in the exam room, and the exam room staff may not be adequately equipped to handle the emotional impact, properly address patient questions, or provide counseling.2,6

Advantages and Disadvantages

Few studies are now being done on the advantages and disadvantages of performing a BE compared to a colonoscopy or CTC—most likely due to the belief that colonoscopy is the better choice. BEs are considered to be one of the safer of the direct screening tests for CRC because sedation is not required and, compared to colonoscopy, the rate of colon perforation is lower (0.02% to 0.04% for BE versus 0.016% to 0.2% for colonoscopy).12,13

In a small study of 15 asymptomatic men age 71, it was found that BEs have a lower sensitivity for detecting CRC as compared with colonoscopy or CTC.2 Sensitivity for lesions ≥ 10 mm is only 48% and for lesions ≥ 6 mm is only 35%, proving the BE to be a highly ineffective screening test for CRC (see Table 1).3

In a randomized study of 5,025 symptomatic patients with abnormal bowel movements and/or abdominal pain, BE has a detection rate of only 5% compared to the much higher sensitivity of CTC or colonoscopy.14

A third study calls attention to the risks associated with the DCBE exam, noting that it is less invasive and less dangerous than colonoscopy, as it does not require sedation and poses less risk for perforation of the lining of the colon.15 The study authors concluded that DCBE has a high sensitivity for clinically significant neoplasms (> 6 mm) but not for small polyps, which may be captured with other tests. DCBE may also supplement incomplete colonoscopy to rule out obstruction.

However, because of the loss of biopsy capabilities, further testing is required when abnormalities are found during the DCBE, diminishing the potential cost effectiveness of the exam. The study authors suggested that DCBEs may be used to screen those who are asymptomatic and seem to have minimal risk factors.15

Limitations

Limitations to successful BE screening include patient compliance and test result interpretation skills. With interpretation skills declining due to limited training of professionals to read BEs, results are becoming less accurate, and the test itself can be seen as less reliable. BEs are less popular, and therefore skills in reading the films are becoming outdated.2 If BE screening is to be used as the primary direct screening tool for CRC, it is imperative that radiologists and gastroenterology physicians and clinicians be well trained in this GI procedure.

Also, patients undergoing BE absorb about 15 mGy of radiation per procedure, versus 0.01 mGy to 0.15 mGy absorbed with a typical chest x-ray.16 For patients with a history of increased radiation exposure or if radiation exposure is a major concern of the patient, BE may not be an appropriate first choice.

On the next page: Colonoscopy >>

COLONOSCOPY

Colonoscopy is an endoscopic technique that allows internal inspection of the entire colorectal tract (see Figure 2).3 Although the most invasive of the exams being reviewed (and requiring extensive bowel prep), it is the gold standard for CRC screening.3

Current literature indicates that colonoscopy should be the screening method of choice for patients who have symptoms of colorectal cancer, positive results with an indirect screening exam such as FOBT, or who fall within a high-risk category. Persons at high risk for CRC include those with a significant family history, persons ages 50 and older, African Americans, and persons with an intestinal inflammatory condition, diabetes mellitus, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, positive smoking status, and low-fiber/high-fat diet.

Procedure

This procedure is performed on an outpatient basis; bowel prep is required one day prior to the procedure so that the bowel movements are clear of fecal matter. The patient receives short-lasting sedation, such as midazolam, via an IV line prior to being brought into the exam room. The procedure itself can take up to 30 minutes, with the patient comfortably sedated in an oblique position. The patient is allowed to recover for several hours, or until awake and able to pass flatus.

Patient Experience

The patient may experience discomfort during the bowel prep phase, as with BE preparation. The patient may be uncomfortable during insertion and manipulation of the colonoscope and also with gaseous insufflation that is used to improve visualization.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The advantages of colonoscopy over the other direct methods are the ability to immediately remove early cancer and colonic polyps and the ability to obtain histologic samples. A suspicious mass can be biopsied during the procedure and, depending on the size, may be completely excised. The histology of the biopsied tissue samples can aid in determining need for further treatment or establish an appropriate surveillance interval for the patient.3

The disadvantages of colonoscopy are related to the possible complications of the procedure, including colon perforation and postpolypectomy bleeding. The risk for these events is estimated to be between 0.1% and 0.3%.3 In addition, the short-lasting sedation that is used during the procedure poses the risk for possible respiratory collapse.6 Therefore, each patient requires medical clearance prior to administering sedation. The risk for a serious adverse event is 3 to 5 per 1,000 colonoscopies, and procedure-related mortality, while rare, has been reported.2,4,14

Limitations

Studies have found colonoscopy to be the most expensive of the direct screening tests, which may pose a problem for uninsured or underinsured patients.4,14

A collection of colonoscopy studies done on patients ages 50 to 66 showed an adenoma miss rate of 20% to 26% for any adenoma < 10 mm, and a 2.1% miss rate for adenomas ≥ 10 mm.3 Adenoma detection rates are dependent on optimal bowel preparation, complete examination of the colon, and the time the clinician spends examining all surfaces of the colon mucosa when withdrawing the colonoscope.3

Colonoscopy has the lowest adherence rate of all the CRC screening tests, which is not surprising since it is invasive, involves sedation, and requires thorough preparation. However, colonoscopies may be performed at longer intervals (up to 10 years) compared to other screening tests; the risk for developing CRC after a negative colonoscopy exam remains low.3

On the next page: CT colonography >>

CT COLONOGRAPHY

CTC is an emerging CRC screening test that is also known as virtual colonoscopy. According to available studies, CTC and colonoscopy might be equivalent for diagnosing cancer.14

Procedure

The preparation for CTC requires the patient to consume a low-residue diet one day prior to the procedure, which is considered to be an advantage over colonoscopy due to the decreased bowel preparation.3 With this procedure, a small rectal catheter is inserted into the anus and advanced to the rectum to allow carbon dioxide to be instilled for bowel insufflation. The patient lies supine on the table for a CT scan of the abdomen with the resulting 2D images visualizing polyps and CRC, if present.3 If necessary, 3D images can be compiled by a specialized software program to obtain a 360-degree view of the colon. In fact, recent studies show that 3D CTC is preferred to 2D because 3D polyp measurements are more representative of the true polyp size found on optic colonoscopy or surgery than are 2D measurements.17

Patient Experience

In one study, CTC screening was described as uncomfortable but not painful and was reported to be the most impersonal of all three tests because of less direct interaction, reducing patient embarrassment. This study reviewed qualitative interviews with patients regarding the fairly new CTC procedure and found that patients received little visual or verbal feedback and were confused regarding their test outcome immediately after the procedure.6

CTC was preferred by 72% of patients compared to colonoscopy and by 97% of patients compared to DCBE.18 In a study that evaluated the performance characteristics of CTC among 1,233 asymptomatic patients, 68% deemed CTC to be more convenient than colonoscopy, and more patients indicated that they preferred CTC over colonoscopy for screening (49.8% vs 41.1%; 9.2% had no preference).19

Advantages and Disadvantages

Compared with colonoscopy, CTC is comparably sensitive but safer and more acceptable to patients.2,6,14 CTC has a sensitivity of 96% for detecting lesions > 10 mm in diameter, but sensitivity decreases to 89% for lesions 6 mm to 10 mm in diameter (see Table 1).2,3,14

The follow-up screening intervals for CTC parallel those of colonoscopy. In a recent audit of 1,011 screening participants with a negative baseline CTC, a single carcinoma occurred during an average follow-up period of 4.73 ± 1.15 years.1

The current Colonography Reporting and Data System (C-RADS) guidelines for CTC interpretation recommend 6 mm as the minimum size for polyp reporting.17 This reporting threshold will result in a 77% reduction rate in invasive endoscopic procedures since it minimizes the number of cases that are sent for colonoscopy after CTC screening.17

A study performed by the American College of Radiology Imaging Network found there would be an approximate 12% referral rate for colonoscopy when using the current 6-mm polyp size threshold, but the referral rate would increase to 17% if a 5-mm threshold were used.17 The American Gastroenterological Association has stated that diminutive lesions—those measuring ≤ 5 mm—are of little to no clinical significance because only a fraction of them are neoplastic. Of these, fewer than 1% are histologically advanced, and essentially none are malignant.6 By not reporting diminutive lesions, there would be an incremental gain in the cost-effectiveness of the CTC scan and only a 1.3% loss in clinical CRC prevention efficacy.

It is widely accepted that any polyp ≥ 10 mm detected with CTC screening indicates a need for polypectomy via colonoscopy or surgery.20 For lesions ranging from 6.1 mm to 9.9 mm in diameter, CTC is suggested as a surveillance tool; patients may receive repeat CTC every 1 to 3 years until resection via colonoscopy is warranted.17

Limitations

CTC screening has many limitations, and evidence is lacking for a reduction of CRC incidence or mortality after CTC. Research has revealed a discrepancy between the polyp size measured by CTC versus the true polyp size seen on optic colonoscopy; CTC measurement can underestimate the size of a polyp by nearly 1.2 mm. Considering that C-RADS level 2 includes polyps 6.1 to 9.9 mm and level 3 includes polyps ≥ 10 mm, which automatically requires further investigation with colonoscopy, such a 1.2-mm discrepancy in measurement can make all the difference.17

CTC requires some bowel preparation, special resources, and expertise. The cost-effectiveness and risk profiles will vary, depending on whether referral for colonoscopy is required. Also, treatment recommendations for patients with polyps < 6 mm in diameter are uncertain.

CTC screening exposes the patient to increased amounts of ionizing radiation, which raises concern regarding risk for radiation-induced cancers. The effective dose to the whole body during a CTC is 6 to 20 mSv, compared to 0.02 mSv for a chest x-ray.16 One study estimated that performing CTC screening every five years from ages 50 to 80 would prevent the development of 24 CRC cases for every one radiation-induced cancer.21 Thus, the risks of radiation must be weighed against the benefits of screening, and the decision is often made by the individual patient.

Finally, the greatest limitation of CTC is that further testing may be required based on the preliminary results. Therefore, the patient may undergo two procedures rather than just one all-inclusive procedure, such as colonoscopy.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

CRC is the second leading cause of death from cancer among men and women in the United States despite the fact that it is largely preventable through diagnostic screening. Patients need education about the different types of CRC screening and about which method may be best for them, given their preferences, family history, personal history, age, and symptoms. All screening tests, direct or indirect, are cost-effective compared with no screening at all.20 Regardless of current recommendations, any screening that the patient is comfortable with should be encouraged.

BE was the first diagnostic tool to provide clinicians with the ability to visualize the patient’s lower gastrointestinal tract. It is becoming technologically outdated, however, and is no longer accepted as a primary diagnostic tool for CRC screening.

Colonoscopy, the most expensive direct screening test, provides complete visualization of the colon and allows for immediate biopsy and possible resection of a suspicious mass. This procedure is the most cost-effective direct screening method because it is comprehensive compared to BE and CTC, which may result in further investigation via colonoscopy if a mass is identified. Although colonoscopy is the most specific and sensitive for CRC screening, the outcome of the test strongly correlates with patient compliance with bowel preparation as well as clinician experience and expertise in performing a thorough exam.

While most US guidelines recommend colonoscopy as the gold standard diagnostic test, CTC is a reliable alternative for those patients who refuse colonoscopy. Future research on this newer method should consider altering the C-RADS threshold that necessitates follow-up with colonoscopy to account for the variation in polyp measurement. CTC is not a stand-alone replacement for the other direct CRC screening tests but is useful as an adjunct to increase overall patient compliance. Perhaps with time, this test may evolve to be a more prevailing recommendation for the preventive screening of CRC.

CE/CME No: CR-13111

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Explain the difference between indirect and direct screening methods for CRC and when to utilize each.

• Understand the age continuum of screening patients with and without increased risk factors for CRC.

• Decide which type of direct screening method is the best choice when looking at sensitivity and specificity and patient preference.

• Understand the risks, benefits, and limitations of each procedure available for CRC screening.

FACULTY

Carolyn Mueller, Molly Perry, and Lisa DeCicco are recent graduates of the Pace University–Lenox Hill Hospital Physician Assistant Program in New York. Ellen D. Mandel is a Clinical Professor in the Pace PA Program and an Associate Professor in the PA Program at Seton Hall University, South Orange, New Jersey.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Because colorectal cancer is often asymptomatic, routine screening is essential to detect lesions at an early stage. The evolution of health care has brought new and improved screening methods for colorectal cancer, including CT colonography. This article weighs the pros and cons of the available screening methods used to detect colorectal cancer in the general population today.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second-leading cause of death from cancer in Europe and the United States and the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in both men and women in the US.1-5 According to the American Cancer Society, 102,480 new cases of colon cancer and 40,340 new cases of rectal cancer will be diagnosed in 2013.5 Although screening rates remain low and the incidence of new CRC diagnoses rises annually, mortality rates are decreasing, most likely due to screening and improved treatment.5

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF COLORECTAL CANCER

CRC is often asymptomatic until it reaches an advanced stage. At this point, symptoms include weight loss, night sweats, fever, loss of appetite, blood in the stool, pencil-shaped stools, diarrhea, constipation, anemia, and/or dizzy spells.6,7 On abdominal exam, a clinician may note dullness to percussion over the right or left lower quadrant, palpate a mass in the right or left lower quadrant, and/or elicit tenderness or guarding upon deep palpation. The clinician may be inclined to do a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) to confirm active GI bleeding.1,3

CURRENT SCREENING RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) currently recommends that screening for CRC—with FOBT, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy—start at age 50 and continue through age 75.8 For patients whose first-degree relative has a history of CRC, initial screening should start at age 40.

It is recommended that people ages 76 to 85 make personalized, informed screening decisions in conjunction with their medical provider. Patients ages 85 or older should not be screened for CRC because of the estimated five-year time frame between the detection of cancer and the onset of symptoms or death. In the unlikely circumstance that the patient is screened and a lesion is found, the patient would not benefit but most likely experience harm from treatment efforts; however, this should be decided on a case-by-case basis.8

CONSIDERATIONS IN SCREENING THE ELDERLY

Much of the data on older populations are outdated, and thus more research needs to be conducted in this population. However, data from two studies dating from 2006 provide tools to help clinicians decide if screening in the older population is beneficial.

One study of the benefit of screening for CRC in the older population stated that clinicians must assess both the burden of chronic illness and the patient’s age as part of their evaluation. This study concluded that, because of the risks and costs that are associated with CRC screening, it is important to identify only those individuals who are likely to benefit from screening, rather than screening the elderly population in general.9

Another study examined the benefit of screening colonoscopy in two elderly groups (ages 75 to 79 and age ≥ 80) versus younger patients (ages 50 to 54; the control group). It was found that

• Screening in the older population may increase the risk for perforation and respiratory depression secondary to sedation,

• Screening may take longer to complete, and

• Screening may be challenging with less successful bowel preparation.10

Further, the prevalence of neoplasia was lowest in the control group (13.8%) compared to the 75-to-79-year-old (26.5%) and oldest (≥ 80; 28.6%) groups. The mean extension of life expectancy was much lower in the oldest group, compared to the control group (0.13 years versus 0.85 years), which represents a 6.5-fold difference. These results suggest that the benefit of colonoscopy screening in elderly persons ages 76 and older results in smaller gains in life expectancy and does not outweigh the risks. This test, therefore, should only be used when the patient expresses a preference for colonoscopy and the clinician feels it will significantly benefit the patient.10

On the next page: Screening methods >>

SCREENING METHODS

Current screening methods for CRC can be divided into two distinct categories: indirect and direct.1 Indirect screening tests include FOBT, fecal immunochemical testing, and stool DNA testing. Cancers are identified by detection of byproducts in the patient’s stool, such as blood or epithelial cells containing DNA of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene. These tests are simple to perform, have high specificity, and are relatively inexpensive, but they need to be repeated annually and have poor sensitivity.1 Positive test results of indirect screening often warrant further diagnostic testing, ultimately utilizing one of the direct screening methods.

Direct screening methods used to detect CRC—from least to most frequently employed—include barium enema (BE), CT colonography (CTC), and colonoscopy. Another direct method, flexible sigmoidoscopy, is not frequently used today, and when used, serves only as an intermediate step to colonoscopy. Direct screening provides visualization of the contour of the colon wall, the internal mucosa, and abnormal architecture. It is important to keep in mind that these tests require that the patient adhere to pretest preparation, may require patient sedation, and are more invasive and costly than indirect tests.1

Although the USPSTF has established recommendations for both test types, questions still remain about what constitutes the most cost-effective and accurate combination of screening tests for detecting CRC.8

On the next page: Barium enema >>

BARIUM ENEMA

Procedure

The BE, also known as a lower GI series, was the first screening test to allow the clinician to identify polyps or masses as outlined by barium sulfate.3 This test requires the patient to lie in an oblique position on his/her left side while barium sulfate (known as single-contrast BE, or SCBE), sometimes followed by air (known as double-contrast BE, or DCBE), is flowed through a tube inserted into the rectum. As the colon fills, the radiologist takes multiple overhead x-ray images. The patient is then required to roll on the table several times, causing the barium to coat the entire mucosa of the colon and rectum, which allows for visualization from various angles (see Figure 1).11

Patient Experience

Screening with the BE has some disadvantages to the patient. Patients may experience discomfort at multiple points: during the instillation of gas and barium into the colon, during the maintenance of the gas and barium levels, and during the maneuvering and holding positions of the procedure itself.2 Some patients, interviewed after a BE was performed, indicated feeling embarrassed during the procedure.6 Although the ability to evaluate images during the exam allows the radiologist to share preliminary results with the patient, the immediate disclosure of bad news is deemed somewhat inappropriate. If the procedure reveals positive findings, the radiologist must be sure to speak with the patient in a private area after the procedure. The patient is in a vulnerable state while in the exam room, and the exam room staff may not be adequately equipped to handle the emotional impact, properly address patient questions, or provide counseling.2,6

Advantages and Disadvantages

Few studies are now being done on the advantages and disadvantages of performing a BE compared to a colonoscopy or CTC—most likely due to the belief that colonoscopy is the better choice. BEs are considered to be one of the safer of the direct screening tests for CRC because sedation is not required and, compared to colonoscopy, the rate of colon perforation is lower (0.02% to 0.04% for BE versus 0.016% to 0.2% for colonoscopy).12,13

In a small study of 15 asymptomatic men age 71, it was found that BEs have a lower sensitivity for detecting CRC as compared with colonoscopy or CTC.2 Sensitivity for lesions ≥ 10 mm is only 48% and for lesions ≥ 6 mm is only 35%, proving the BE to be a highly ineffective screening test for CRC (see Table 1).3

In a randomized study of 5,025 symptomatic patients with abnormal bowel movements and/or abdominal pain, BE has a detection rate of only 5% compared to the much higher sensitivity of CTC or colonoscopy.14

A third study calls attention to the risks associated with the DCBE exam, noting that it is less invasive and less dangerous than colonoscopy, as it does not require sedation and poses less risk for perforation of the lining of the colon.15 The study authors concluded that DCBE has a high sensitivity for clinically significant neoplasms (> 6 mm) but not for small polyps, which may be captured with other tests. DCBE may also supplement incomplete colonoscopy to rule out obstruction.

However, because of the loss of biopsy capabilities, further testing is required when abnormalities are found during the DCBE, diminishing the potential cost effectiveness of the exam. The study authors suggested that DCBEs may be used to screen those who are asymptomatic and seem to have minimal risk factors.15

Limitations

Limitations to successful BE screening include patient compliance and test result interpretation skills. With interpretation skills declining due to limited training of professionals to read BEs, results are becoming less accurate, and the test itself can be seen as less reliable. BEs are less popular, and therefore skills in reading the films are becoming outdated.2 If BE screening is to be used as the primary direct screening tool for CRC, it is imperative that radiologists and gastroenterology physicians and clinicians be well trained in this GI procedure.

Also, patients undergoing BE absorb about 15 mGy of radiation per procedure, versus 0.01 mGy to 0.15 mGy absorbed with a typical chest x-ray.16 For patients with a history of increased radiation exposure or if radiation exposure is a major concern of the patient, BE may not be an appropriate first choice.

On the next page: Colonoscopy >>

COLONOSCOPY

Colonoscopy is an endoscopic technique that allows internal inspection of the entire colorectal tract (see Figure 2).3 Although the most invasive of the exams being reviewed (and requiring extensive bowel prep), it is the gold standard for CRC screening.3

Current literature indicates that colonoscopy should be the screening method of choice for patients who have symptoms of colorectal cancer, positive results with an indirect screening exam such as FOBT, or who fall within a high-risk category. Persons at high risk for CRC include those with a significant family history, persons ages 50 and older, African Americans, and persons with an intestinal inflammatory condition, diabetes mellitus, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, positive smoking status, and low-fiber/high-fat diet.

Procedure

This procedure is performed on an outpatient basis; bowel prep is required one day prior to the procedure so that the bowel movements are clear of fecal matter. The patient receives short-lasting sedation, such as midazolam, via an IV line prior to being brought into the exam room. The procedure itself can take up to 30 minutes, with the patient comfortably sedated in an oblique position. The patient is allowed to recover for several hours, or until awake and able to pass flatus.

Patient Experience

The patient may experience discomfort during the bowel prep phase, as with BE preparation. The patient may be uncomfortable during insertion and manipulation of the colonoscope and also with gaseous insufflation that is used to improve visualization.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The advantages of colonoscopy over the other direct methods are the ability to immediately remove early cancer and colonic polyps and the ability to obtain histologic samples. A suspicious mass can be biopsied during the procedure and, depending on the size, may be completely excised. The histology of the biopsied tissue samples can aid in determining need for further treatment or establish an appropriate surveillance interval for the patient.3

The disadvantages of colonoscopy are related to the possible complications of the procedure, including colon perforation and postpolypectomy bleeding. The risk for these events is estimated to be between 0.1% and 0.3%.3 In addition, the short-lasting sedation that is used during the procedure poses the risk for possible respiratory collapse.6 Therefore, each patient requires medical clearance prior to administering sedation. The risk for a serious adverse event is 3 to 5 per 1,000 colonoscopies, and procedure-related mortality, while rare, has been reported.2,4,14

Limitations

Studies have found colonoscopy to be the most expensive of the direct screening tests, which may pose a problem for uninsured or underinsured patients.4,14

A collection of colonoscopy studies done on patients ages 50 to 66 showed an adenoma miss rate of 20% to 26% for any adenoma < 10 mm, and a 2.1% miss rate for adenomas ≥ 10 mm.3 Adenoma detection rates are dependent on optimal bowel preparation, complete examination of the colon, and the time the clinician spends examining all surfaces of the colon mucosa when withdrawing the colonoscope.3

Colonoscopy has the lowest adherence rate of all the CRC screening tests, which is not surprising since it is invasive, involves sedation, and requires thorough preparation. However, colonoscopies may be performed at longer intervals (up to 10 years) compared to other screening tests; the risk for developing CRC after a negative colonoscopy exam remains low.3

On the next page: CT colonography >>

CT COLONOGRAPHY

CTC is an emerging CRC screening test that is also known as virtual colonoscopy. According to available studies, CTC and colonoscopy might be equivalent for diagnosing cancer.14

Procedure

The preparation for CTC requires the patient to consume a low-residue diet one day prior to the procedure, which is considered to be an advantage over colonoscopy due to the decreased bowel preparation.3 With this procedure, a small rectal catheter is inserted into the anus and advanced to the rectum to allow carbon dioxide to be instilled for bowel insufflation. The patient lies supine on the table for a CT scan of the abdomen with the resulting 2D images visualizing polyps and CRC, if present.3 If necessary, 3D images can be compiled by a specialized software program to obtain a 360-degree view of the colon. In fact, recent studies show that 3D CTC is preferred to 2D because 3D polyp measurements are more representative of the true polyp size found on optic colonoscopy or surgery than are 2D measurements.17

Patient Experience

In one study, CTC screening was described as uncomfortable but not painful and was reported to be the most impersonal of all three tests because of less direct interaction, reducing patient embarrassment. This study reviewed qualitative interviews with patients regarding the fairly new CTC procedure and found that patients received little visual or verbal feedback and were confused regarding their test outcome immediately after the procedure.6

CTC was preferred by 72% of patients compared to colonoscopy and by 97% of patients compared to DCBE.18 In a study that evaluated the performance characteristics of CTC among 1,233 asymptomatic patients, 68% deemed CTC to be more convenient than colonoscopy, and more patients indicated that they preferred CTC over colonoscopy for screening (49.8% vs 41.1%; 9.2% had no preference).19

Advantages and Disadvantages

Compared with colonoscopy, CTC is comparably sensitive but safer and more acceptable to patients.2,6,14 CTC has a sensitivity of 96% for detecting lesions > 10 mm in diameter, but sensitivity decreases to 89% for lesions 6 mm to 10 mm in diameter (see Table 1).2,3,14

The follow-up screening intervals for CTC parallel those of colonoscopy. In a recent audit of 1,011 screening participants with a negative baseline CTC, a single carcinoma occurred during an average follow-up period of 4.73 ± 1.15 years.1

The current Colonography Reporting and Data System (C-RADS) guidelines for CTC interpretation recommend 6 mm as the minimum size for polyp reporting.17 This reporting threshold will result in a 77% reduction rate in invasive endoscopic procedures since it minimizes the number of cases that are sent for colonoscopy after CTC screening.17

A study performed by the American College of Radiology Imaging Network found there would be an approximate 12% referral rate for colonoscopy when using the current 6-mm polyp size threshold, but the referral rate would increase to 17% if a 5-mm threshold were used.17 The American Gastroenterological Association has stated that diminutive lesions—those measuring ≤ 5 mm—are of little to no clinical significance because only a fraction of them are neoplastic. Of these, fewer than 1% are histologically advanced, and essentially none are malignant.6 By not reporting diminutive lesions, there would be an incremental gain in the cost-effectiveness of the CTC scan and only a 1.3% loss in clinical CRC prevention efficacy.

It is widely accepted that any polyp ≥ 10 mm detected with CTC screening indicates a need for polypectomy via colonoscopy or surgery.20 For lesions ranging from 6.1 mm to 9.9 mm in diameter, CTC is suggested as a surveillance tool; patients may receive repeat CTC every 1 to 3 years until resection via colonoscopy is warranted.17

Limitations

CTC screening has many limitations, and evidence is lacking for a reduction of CRC incidence or mortality after CTC. Research has revealed a discrepancy between the polyp size measured by CTC versus the true polyp size seen on optic colonoscopy; CTC measurement can underestimate the size of a polyp by nearly 1.2 mm. Considering that C-RADS level 2 includes polyps 6.1 to 9.9 mm and level 3 includes polyps ≥ 10 mm, which automatically requires further investigation with colonoscopy, such a 1.2-mm discrepancy in measurement can make all the difference.17

CTC requires some bowel preparation, special resources, and expertise. The cost-effectiveness and risk profiles will vary, depending on whether referral for colonoscopy is required. Also, treatment recommendations for patients with polyps < 6 mm in diameter are uncertain.

CTC screening exposes the patient to increased amounts of ionizing radiation, which raises concern regarding risk for radiation-induced cancers. The effective dose to the whole body during a CTC is 6 to 20 mSv, compared to 0.02 mSv for a chest x-ray.16 One study estimated that performing CTC screening every five years from ages 50 to 80 would prevent the development of 24 CRC cases for every one radiation-induced cancer.21 Thus, the risks of radiation must be weighed against the benefits of screening, and the decision is often made by the individual patient.

Finally, the greatest limitation of CTC is that further testing may be required based on the preliminary results. Therefore, the patient may undergo two procedures rather than just one all-inclusive procedure, such as colonoscopy.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

CRC is the second leading cause of death from cancer among men and women in the United States despite the fact that it is largely preventable through diagnostic screening. Patients need education about the different types of CRC screening and about which method may be best for them, given their preferences, family history, personal history, age, and symptoms. All screening tests, direct or indirect, are cost-effective compared with no screening at all.20 Regardless of current recommendations, any screening that the patient is comfortable with should be encouraged.

BE was the first diagnostic tool to provide clinicians with the ability to visualize the patient’s lower gastrointestinal tract. It is becoming technologically outdated, however, and is no longer accepted as a primary diagnostic tool for CRC screening.

Colonoscopy, the most expensive direct screening test, provides complete visualization of the colon and allows for immediate biopsy and possible resection of a suspicious mass. This procedure is the most cost-effective direct screening method because it is comprehensive compared to BE and CTC, which may result in further investigation via colonoscopy if a mass is identified. Although colonoscopy is the most specific and sensitive for CRC screening, the outcome of the test strongly correlates with patient compliance with bowel preparation as well as clinician experience and expertise in performing a thorough exam.

While most US guidelines recommend colonoscopy as the gold standard diagnostic test, CTC is a reliable alternative for those patients who refuse colonoscopy. Future research on this newer method should consider altering the C-RADS threshold that necessitates follow-up with colonoscopy to account for the variation in polyp measurement. CTC is not a stand-alone replacement for the other direct CRC screening tests but is useful as an adjunct to increase overall patient compliance. Perhaps with time, this test may evolve to be a more prevailing recommendation for the preventive screening of CRC.

1. de Haan MC, Halligan S, Stoker J. Does CT colonography have a role for population-based colorectal cancer CRC screening? Eur Radiol. 2012;22: 1495-1503.

2. Lieberman D. Screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361: 1179-1187.

3. de Wijkerslooth TR, Bossuyt PM, Dekker E. Strategies in screening for colon carcinoma. Neth J Med. 2011;69:112-119.

4. Whitlock E, Lin J, Liles E, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: an updated systematic review. Evidence Synthesis No. 65, Part 1. AHRQ Publication No. 08-05124-EF-1. Rockville, Maryland, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, October 2008.

5. Colorectal cancer: What are the key statistics about colorectal cancer? American Cancer Society. www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/detailedguide/colorectal-cancer-key-statistics. Accessed October 14, 2013.

6. Von Wagner C, Knight K, Halligan S, et al. Patient experiences of colonoscopy, barium enema and CT colonography: a qualitative study. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:13-19.

7. Cappell MS. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and management of colon cancer. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2008;37:1-24.

8. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. US Preventive Services Task Force web site. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscolo.htm. Published 2008. Accessed October 14, 2013.

9. Gross CP, McAvay GJ, Krumholz HM, et al. The effect of age and chronic illness on life expectancy after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer: implications for screening. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:646-653.

10. Lin OS, Kozarek RA, Schembre DB, et al. Screening colonoscopy in very elderly patients: prevalence of neoplasia and estimated impact on life expectancy. JAMA. 2006;295:2357-2365.

11. Colorectal cancer early detection: colorectal cancer screening tests. American Cancer Society. www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/moreinformation/colonandrectumcancerearlydetection/colorectal-cancer-early-detection-screening-tests-used. Accessed October 14, 2013.

12. Lohsiriwat V. Colonoscopic perforation: incidence, risk factors, management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:425-430.

13. Yasar NF, Ihtiyar E. Colonic perforation during barium enema in a patient without known colonic disease: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:6716.

14. Halligan S, Lilford RJ, Wardle J, et al. Design of a multicentre randomized trial to evaluate CT colonography versus colonoscopy or barium enema for diagnosis of colonic cancer in older symptomatic patients: The SIGGAR study. Trials. 2007;8:1-9.

15. Lohsiriwat V, Prapasrivorakul S, Suthikeeree W. Colorectal cancer screening by double contrast barium enema in Thai people.Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:1273-1276.

16. Mayo JR, Aldrich J, Muller NL; Fleischner Society. Radiation exposure at chest CT: a statement of the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2003;228:15-21.

17. Summers RM. Polyp size measurement at CT colonography: what do we know and what do we need to know? Radiology. 2010;255(3):707-720.

18. Gluecker TM, Johnson CD, Harmsen WS, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with CT colonography, colonoscopy, and double-contrast barium enema examination: prospective assessment of patient perceptions and p. Radiology. 2003;227:378-384.

19. Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2191-2200.

20. Pickhardt P, Hassan C, Laghi A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening with computed tomography colonography. Cancer. 2007;109:2213-2221.

21. Berrington de Gonzalez A, Kim KP, Knudsen AB, et al. Radiation-related cancer risks from CT colongraphy screening: a risk-benefit analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:816-823.

1. de Haan MC, Halligan S, Stoker J. Does CT colonography have a role for population-based colorectal cancer CRC screening? Eur Radiol. 2012;22: 1495-1503.

2. Lieberman D. Screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361: 1179-1187.

3. de Wijkerslooth TR, Bossuyt PM, Dekker E. Strategies in screening for colon carcinoma. Neth J Med. 2011;69:112-119.

4. Whitlock E, Lin J, Liles E, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: an updated systematic review. Evidence Synthesis No. 65, Part 1. AHRQ Publication No. 08-05124-EF-1. Rockville, Maryland, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, October 2008.

5. Colorectal cancer: What are the key statistics about colorectal cancer? American Cancer Society. www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/detailedguide/colorectal-cancer-key-statistics. Accessed October 14, 2013.

6. Von Wagner C, Knight K, Halligan S, et al. Patient experiences of colonoscopy, barium enema and CT colonography: a qualitative study. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:13-19.

7. Cappell MS. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and management of colon cancer. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2008;37:1-24.

8. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. US Preventive Services Task Force web site. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscolo.htm. Published 2008. Accessed October 14, 2013.

9. Gross CP, McAvay GJ, Krumholz HM, et al. The effect of age and chronic illness on life expectancy after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer: implications for screening. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:646-653.

10. Lin OS, Kozarek RA, Schembre DB, et al. Screening colonoscopy in very elderly patients: prevalence of neoplasia and estimated impact on life expectancy. JAMA. 2006;295:2357-2365.

11. Colorectal cancer early detection: colorectal cancer screening tests. American Cancer Society. www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/moreinformation/colonandrectumcancerearlydetection/colorectal-cancer-early-detection-screening-tests-used. Accessed October 14, 2013.

12. Lohsiriwat V. Colonoscopic perforation: incidence, risk factors, management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:425-430.

13. Yasar NF, Ihtiyar E. Colonic perforation during barium enema in a patient without known colonic disease: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:6716.

14. Halligan S, Lilford RJ, Wardle J, et al. Design of a multicentre randomized trial to evaluate CT colonography versus colonoscopy or barium enema for diagnosis of colonic cancer in older symptomatic patients: The SIGGAR study. Trials. 2007;8:1-9.

15. Lohsiriwat V, Prapasrivorakul S, Suthikeeree W. Colorectal cancer screening by double contrast barium enema in Thai people.Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:1273-1276.

16. Mayo JR, Aldrich J, Muller NL; Fleischner Society. Radiation exposure at chest CT: a statement of the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2003;228:15-21.

17. Summers RM. Polyp size measurement at CT colonography: what do we know and what do we need to know? Radiology. 2010;255(3):707-720.

18. Gluecker TM, Johnson CD, Harmsen WS, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with CT colonography, colonoscopy, and double-contrast barium enema examination: prospective assessment of patient perceptions and p. Radiology. 2003;227:378-384.

19. Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2191-2200.

20. Pickhardt P, Hassan C, Laghi A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening with computed tomography colonography. Cancer. 2007;109:2213-2221.

21. Berrington de Gonzalez A, Kim KP, Knudsen AB, et al. Radiation-related cancer risks from CT colongraphy screening: a risk-benefit analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:816-823.