User login

From the Tucson Medical Center, Tucson, AZ.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a quality improvement project to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) in an intensive care unit (ICU).

- Methods: Descriptive report.

- Results: CAUTIs are a common health care–associated infection that results in increased length of stay, patient discomfort, excess health care costs, and sometime mortality. However, many cases of CAUTIs are preventable. To address this problem at our institution, we enrolled in the Hospital Engagement Network (HEN) collaborative for the reduction of CAUTIs, utilizing the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) as the platform for our project. This article describes our project implementation, challenges encountered, and the lasting improvement we have achieved at our facility.

- Conclusion: By challenging the ICU culture, providing nursing with alternatives to urinary catheters, and promoting physician engagement, we were able to reduce catheter utilization and CAUTI rates in the ICU.

Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) are important causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States [1]. Among HAIs, urinary tract infections are the 4th most common, with almost all cases caused by urethral instrumentation [2]. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) are associated with an increased hospital length of stay of 2 to 4 days and a cost of $400 million to $500 million annually [3]. As of 2015, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services no longer reimburses hospitals for treating CAUTIs.

CAUTIs are a particular challenge in the intensive care unit (ICU) due to the high urinary catheter utilization rates. In our mixed medical/surgical ICU, the catheter utilization rate was 84% in 2012 and was the setting for the majority of CAUTIs in our hospital. The risk of CAUTI can be reduced by ensuring that catheters are used only when needed and removed as soon as possible; that catheters are placed using proper aseptic technique; and that the closed sterile drainage system is maintained. In 2013 we launched a project to improve our CAUTI rates and enrolled in the Hospital Engagement Network (HEN) collaborative for the reduction of CAUTIs, utilizing the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) [4] as the platform for our project. This article describes our project implementation, the challenges we encountered, and the lasting improvement we have achieved.

Setting

Tucson Medical Center is a 600-bed tertiary care hospital, the largest in southern Arizona, with over 1000 independent medical providers. The medical center is a locally governed, nonprofit teaching hospital that has been providing care to the city of Tucson, southern Arizona, southwest New Mexico, and northern Mexico for the past 70 years. There are 2 adult critical care units: a cardiovascular ICU and a mixed medical/surgical ICU. We focused our efforts and interventions on the mixed ICU, a 16-bed unit that includes medical, surgical (neuro, general and vascular), and neurological patient populations that had 19 CAUTIs in 2012, versus 2 CAUTIs in the cardiovascular ICU.

Project

Initial Phase

The first steps in our project were to develop our unit-based team, identify project goals, and review our current nursing practice and processes. First, using the template from the CUSP platform, we assembled a team that consisted of the chief nursing officer (executive sponsor), ICU medical director, nurse manager, infection control manager, infection control nurse, 4 nurse champions (2 two night shift 2 day shift), and a patient care technician.

The second step was to identify a realistic and achievable goal. A goal of a 20% reduction from our current utilization rate was selected. As our catheter utilization rates were consistently above 90%, we aimed to for a rate of less than 70%. In addition, we sought to reduce our CAUTI standardized infection ratio (number of health care–associated infections observed divided by the national predicted number) from 3.875 to less than 1.0.

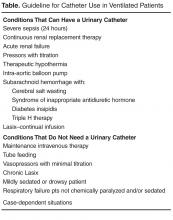

In reviewing our current nursing practice and processes, we utilized the CUSP data collection tool and adapted it to meet our institutional needs. Figure 1 shows the original CUSP data collection tool, which is organized around 5 key questions about the catheter (eg, Is catheter present? Where it was placed? Why does the patient has a catheter today?) as well as lists appropriate and inappropriate indications.

To implement the guidelines, we provided education to the nursing staff via emails, placed posters on the unit, and discussed appropriate and inappropriate indications during bedside conversations using the audit tool. As the project continued, these guidelines were reinforced daily when the question “why does your patient have a catheter today?” was posed to the nurses during the audit. Our chief nursing officer supported our implementation efforts by including a CAUTI prevention lecture with her monthly house-wide nursing education series called “lunch and learn.”

We added additional questions to the tool as we learned more about the practices and processes that were currently in use. For example, “accurate measurement of urinary output in the critically ill patient” was the most common reason given by nurses for keeping a catheter in. Upon further questioning, however, the common response was that “the doctor ordered it.” By adding “MD order” to the audit tool, we were able to track actual orders versus nurses falling back on old patterns. This data collection item also provided us the names and groups of physicians to approach and educate on our project goals. Two other helpful items added to the tool related to the catheter seal and stat lock (catheter securement device) placement. The data provided by these questions helped us recognize areas for improvement in nursing practice, supply issues, and the impact of other departments. For example, auditing showed that most of our catheters were placed in the emergency department (ED) and surgery. This gave us an opportunity to reach out to these units to discuss CAUTI reduction strategies. For example, after review of the ED catheter supplies, we discovered that they did not have a closed catheter insertion system with a urometer drainage bag. Therefore, when a patient was transferred to the ICU, the integrity of the urinary collection system had to be broken to place a urometer. Evidence has shown that breaking the integrity of the system increases a patient’s risk for a CAUTI [1]. Once this problem was identified, the ED inventory was changed to include the urometer as part of the closed system urinary insertion kit.

Active Phase

After the implementation phase, the next 15 months were dedicated to daily rounding and bedside auditing, the foundation of our project. Rounding was done by the unit manager or nurse champion and involved talking with the bedside nurse and completing the audit tool. These bedside conversations were an opportunity to review the HICPAC guidelines, identify education needs, and reinforce best practices. During these discussions, the nurses often would identify reasons to remove catheters.

The CAUTI team met monthly to review the previous month’s data, other observed opportunities for improvement, and any patient CAUTI information provided by our infection control nurse liaison. We conducted root cause analysis when CAUTIs developed, in which we reviewed the patient’s chart and sought to identify possible interventions that could have reduced the number of catheter days. Our findings were shared in staff meetings, newsletters, and through quality bulletin boards. We also recognized improved performance. Tokens that could be cashed in at the cafeteria for snacks or drinks were awarded to nurses who removed a urinary catheter. We also organized a celebration on the unit the first time we had 3 months without a CAUTI.

Challenges Encountered

Culture change is challenging. The entrenched mindset was that “If a patient is sick enough to be in an ICU, then they are sick enough to need a urinary catheter.” Standard nursing practice typically included placement of a urinary catheter immediately on arrival to the ICU if not already present. Over the years, placing a urinary catheter had become the norm in the ICU, with nurses noting concern about obtaining accurate measurement of urine output and prevention of skin breakdown from incontinence. We had to continually address these concerns to make progress on the project. By providing alternatives to urinary catheters, such as incontinence pads, external male collection devices in varying sizes, moisture barrier products, and scales to measure urine output, nurses were more willing to comply with catheter removal.

We worked with our wound and ostomy nurses to ensure we were providing the proper moisture barrier products and presented research to support that incontinence did not need to lead to pressure ulcers. The wound care team helped with guiding the use of products for incontinent patients to prevent incontinence-associated dermatitis and potential skin breakdown. Our administration financially supported our program, allowing us to bring in and trial supplies. As we identified products for use, we were able to place them into floor stock and make them easily available to nursing. Items such as wicking pads, skin protective creams, and alternatives to catheters were a vital part of our bedside toolkit to maintain our patient’s skin integrity.

Both nurses and physicians were concerned about accurate measurement of output, specifically in surgical patients. The use of scales to weigh and measure output from an incontinent patient’s pads was helpful but sometimes inconvenient. From our surgeons' perspective, not having immediate hourly measurements of urine output to monitor risk for hypovolemia from third spacing of fluid or from abdominal compartment syndrome was not acceptable. Because of this concern, we did not see a decrease in early catheter removal among surgical patients. Daily conversations with nurses and surgeons at the bedside continue to be key to removing catheters as soon as the surgeon is comfortable that the patient is out of risk for hypovolemia.

Outcomes

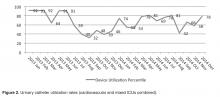

Within the first month we saw an immediate drop in catheter utilization and had zero CAUTIs, but during the next 2 months there was a return to our previous rates (Figure 2 and Figure 3 [figures show combined mixed and cardiovascular ICU rates due to reporting requirements]).

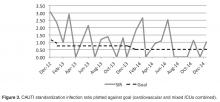

Although nursing is at the heart of this engagement, it is the combined efforts of all disciplines that promote the reduction of CAUTIs and improve patient outcomes. When our CAUTI counts plateaued at 10 annually in 2014–2015, we reached out to physicians and found that we had not adequately educated our medical and surgical staff of our project and goals. With the backing of a supportive and vocal ICU director, physician engagement has increased and there is more attention paid to catheter removal by our ICU intensivists. This collaborative approach has helped lower our rates even further in 2016 (n = 3). We achieved our CAUTI SIR goal of less than 1.0 , and changed our current goal to less than 0.5 (Figure 3).

In addition to greater intensivist engagement, the ED reduced their urinary catheter insertion rate from 12% to 4% for all patients transferring to an inpatient status. As previously mentioned, they are now placing catheters from kits that include urometers, so we do not have to break the integrity of the closed system after the patient it transferred to the ICU. We are also collaborating with surgical services to reduce catheter use. This is still a work in progress that requires collaboration with surgeons and hospitalists in changing departmental norms.

Conclusion

Through a combined effort involving a number of departments across the hospital, we were able to reduce catheter utilization and CAUTI rates in the ICU. We have seen a culture shift, with more ICU nursing staff questioning the use of catheters and requesting to have them removed during daily bedside rounds or simply removing them based on our nursing-driven protocol. Currently, both critical care units have been actively working on reducing CAUTI rates and have gone 310 days without a CAUTI.

Reluctance among ICU nurses to remove urinary catheters has declined; however, it is easy to fall back on the convenience of catheters. We have found that each rise in utilization rates and CAUTIs pointed to the need to refocus our effort on the daily bedside conversations. Unless we can eliminate the need for urinary catheters, there will always be a risk of a CAUTI. However, with advances in catheter technology, alternatives to catheters, and nursing education, the reduction in this hospital-acquired infection can be realized.

Acknowledgments: The author thanks our devoted infection control manager (now director), Nina Espinoza Mazzola, BSM, CIC. Our attaining success at the bedside is a reflection of her commitment as a resource and in providing support for nursing practice.

Corresponding author: Jennifer C. Tuttle, RN, MSNEd, CNRN, Tucson Medical Center, 5301 E. Grant Rd, Tucson, AZ 85712.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Nicolle LE. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2014;3:23.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Urinary tract infection (catheter-associated urinary tract infection [cauti] and non-catheter-associated urinary tract infection [uti]) and other urinary system infection [usi]) events. 2017. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/7psccauticurrent.pdf.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (cauti) toolkit. Accessed 5 Mar 2017 at www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/toolkits/CAUTItoolkit_3_10.pdf.

4. On the CUSP implementation guide. Accessed at http://web.mhanet.com/cauti-implementation_guide_508.pdf.

5. Healthcare Infection Control Practice Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guidelines for the prevention of catheter associated urinary tract infections 2009. Accessed 25 Feb 2017 at www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/cauti-guidelines.pdf.

From the Tucson Medical Center, Tucson, AZ.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a quality improvement project to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) in an intensive care unit (ICU).

- Methods: Descriptive report.

- Results: CAUTIs are a common health care–associated infection that results in increased length of stay, patient discomfort, excess health care costs, and sometime mortality. However, many cases of CAUTIs are preventable. To address this problem at our institution, we enrolled in the Hospital Engagement Network (HEN) collaborative for the reduction of CAUTIs, utilizing the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) as the platform for our project. This article describes our project implementation, challenges encountered, and the lasting improvement we have achieved at our facility.

- Conclusion: By challenging the ICU culture, providing nursing with alternatives to urinary catheters, and promoting physician engagement, we were able to reduce catheter utilization and CAUTI rates in the ICU.

Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) are important causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States [1]. Among HAIs, urinary tract infections are the 4th most common, with almost all cases caused by urethral instrumentation [2]. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) are associated with an increased hospital length of stay of 2 to 4 days and a cost of $400 million to $500 million annually [3]. As of 2015, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services no longer reimburses hospitals for treating CAUTIs.

CAUTIs are a particular challenge in the intensive care unit (ICU) due to the high urinary catheter utilization rates. In our mixed medical/surgical ICU, the catheter utilization rate was 84% in 2012 and was the setting for the majority of CAUTIs in our hospital. The risk of CAUTI can be reduced by ensuring that catheters are used only when needed and removed as soon as possible; that catheters are placed using proper aseptic technique; and that the closed sterile drainage system is maintained. In 2013 we launched a project to improve our CAUTI rates and enrolled in the Hospital Engagement Network (HEN) collaborative for the reduction of CAUTIs, utilizing the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) [4] as the platform for our project. This article describes our project implementation, the challenges we encountered, and the lasting improvement we have achieved.

Setting

Tucson Medical Center is a 600-bed tertiary care hospital, the largest in southern Arizona, with over 1000 independent medical providers. The medical center is a locally governed, nonprofit teaching hospital that has been providing care to the city of Tucson, southern Arizona, southwest New Mexico, and northern Mexico for the past 70 years. There are 2 adult critical care units: a cardiovascular ICU and a mixed medical/surgical ICU. We focused our efforts and interventions on the mixed ICU, a 16-bed unit that includes medical, surgical (neuro, general and vascular), and neurological patient populations that had 19 CAUTIs in 2012, versus 2 CAUTIs in the cardiovascular ICU.

Project

Initial Phase

The first steps in our project were to develop our unit-based team, identify project goals, and review our current nursing practice and processes. First, using the template from the CUSP platform, we assembled a team that consisted of the chief nursing officer (executive sponsor), ICU medical director, nurse manager, infection control manager, infection control nurse, 4 nurse champions (2 two night shift 2 day shift), and a patient care technician.

The second step was to identify a realistic and achievable goal. A goal of a 20% reduction from our current utilization rate was selected. As our catheter utilization rates were consistently above 90%, we aimed to for a rate of less than 70%. In addition, we sought to reduce our CAUTI standardized infection ratio (number of health care–associated infections observed divided by the national predicted number) from 3.875 to less than 1.0.

In reviewing our current nursing practice and processes, we utilized the CUSP data collection tool and adapted it to meet our institutional needs. Figure 1 shows the original CUSP data collection tool, which is organized around 5 key questions about the catheter (eg, Is catheter present? Where it was placed? Why does the patient has a catheter today?) as well as lists appropriate and inappropriate indications.

To implement the guidelines, we provided education to the nursing staff via emails, placed posters on the unit, and discussed appropriate and inappropriate indications during bedside conversations using the audit tool. As the project continued, these guidelines were reinforced daily when the question “why does your patient have a catheter today?” was posed to the nurses during the audit. Our chief nursing officer supported our implementation efforts by including a CAUTI prevention lecture with her monthly house-wide nursing education series called “lunch and learn.”

We added additional questions to the tool as we learned more about the practices and processes that were currently in use. For example, “accurate measurement of urinary output in the critically ill patient” was the most common reason given by nurses for keeping a catheter in. Upon further questioning, however, the common response was that “the doctor ordered it.” By adding “MD order” to the audit tool, we were able to track actual orders versus nurses falling back on old patterns. This data collection item also provided us the names and groups of physicians to approach and educate on our project goals. Two other helpful items added to the tool related to the catheter seal and stat lock (catheter securement device) placement. The data provided by these questions helped us recognize areas for improvement in nursing practice, supply issues, and the impact of other departments. For example, auditing showed that most of our catheters were placed in the emergency department (ED) and surgery. This gave us an opportunity to reach out to these units to discuss CAUTI reduction strategies. For example, after review of the ED catheter supplies, we discovered that they did not have a closed catheter insertion system with a urometer drainage bag. Therefore, when a patient was transferred to the ICU, the integrity of the urinary collection system had to be broken to place a urometer. Evidence has shown that breaking the integrity of the system increases a patient’s risk for a CAUTI [1]. Once this problem was identified, the ED inventory was changed to include the urometer as part of the closed system urinary insertion kit.

Active Phase

After the implementation phase, the next 15 months were dedicated to daily rounding and bedside auditing, the foundation of our project. Rounding was done by the unit manager or nurse champion and involved talking with the bedside nurse and completing the audit tool. These bedside conversations were an opportunity to review the HICPAC guidelines, identify education needs, and reinforce best practices. During these discussions, the nurses often would identify reasons to remove catheters.

The CAUTI team met monthly to review the previous month’s data, other observed opportunities for improvement, and any patient CAUTI information provided by our infection control nurse liaison. We conducted root cause analysis when CAUTIs developed, in which we reviewed the patient’s chart and sought to identify possible interventions that could have reduced the number of catheter days. Our findings were shared in staff meetings, newsletters, and through quality bulletin boards. We also recognized improved performance. Tokens that could be cashed in at the cafeteria for snacks or drinks were awarded to nurses who removed a urinary catheter. We also organized a celebration on the unit the first time we had 3 months without a CAUTI.

Challenges Encountered

Culture change is challenging. The entrenched mindset was that “If a patient is sick enough to be in an ICU, then they are sick enough to need a urinary catheter.” Standard nursing practice typically included placement of a urinary catheter immediately on arrival to the ICU if not already present. Over the years, placing a urinary catheter had become the norm in the ICU, with nurses noting concern about obtaining accurate measurement of urine output and prevention of skin breakdown from incontinence. We had to continually address these concerns to make progress on the project. By providing alternatives to urinary catheters, such as incontinence pads, external male collection devices in varying sizes, moisture barrier products, and scales to measure urine output, nurses were more willing to comply with catheter removal.

We worked with our wound and ostomy nurses to ensure we were providing the proper moisture barrier products and presented research to support that incontinence did not need to lead to pressure ulcers. The wound care team helped with guiding the use of products for incontinent patients to prevent incontinence-associated dermatitis and potential skin breakdown. Our administration financially supported our program, allowing us to bring in and trial supplies. As we identified products for use, we were able to place them into floor stock and make them easily available to nursing. Items such as wicking pads, skin protective creams, and alternatives to catheters were a vital part of our bedside toolkit to maintain our patient’s skin integrity.

Both nurses and physicians were concerned about accurate measurement of output, specifically in surgical patients. The use of scales to weigh and measure output from an incontinent patient’s pads was helpful but sometimes inconvenient. From our surgeons' perspective, not having immediate hourly measurements of urine output to monitor risk for hypovolemia from third spacing of fluid or from abdominal compartment syndrome was not acceptable. Because of this concern, we did not see a decrease in early catheter removal among surgical patients. Daily conversations with nurses and surgeons at the bedside continue to be key to removing catheters as soon as the surgeon is comfortable that the patient is out of risk for hypovolemia.

Outcomes

Within the first month we saw an immediate drop in catheter utilization and had zero CAUTIs, but during the next 2 months there was a return to our previous rates (Figure 2 and Figure 3 [figures show combined mixed and cardiovascular ICU rates due to reporting requirements]).

Although nursing is at the heart of this engagement, it is the combined efforts of all disciplines that promote the reduction of CAUTIs and improve patient outcomes. When our CAUTI counts plateaued at 10 annually in 2014–2015, we reached out to physicians and found that we had not adequately educated our medical and surgical staff of our project and goals. With the backing of a supportive and vocal ICU director, physician engagement has increased and there is more attention paid to catheter removal by our ICU intensivists. This collaborative approach has helped lower our rates even further in 2016 (n = 3). We achieved our CAUTI SIR goal of less than 1.0 , and changed our current goal to less than 0.5 (Figure 3).

In addition to greater intensivist engagement, the ED reduced their urinary catheter insertion rate from 12% to 4% for all patients transferring to an inpatient status. As previously mentioned, they are now placing catheters from kits that include urometers, so we do not have to break the integrity of the closed system after the patient it transferred to the ICU. We are also collaborating with surgical services to reduce catheter use. This is still a work in progress that requires collaboration with surgeons and hospitalists in changing departmental norms.

Conclusion

Through a combined effort involving a number of departments across the hospital, we were able to reduce catheter utilization and CAUTI rates in the ICU. We have seen a culture shift, with more ICU nursing staff questioning the use of catheters and requesting to have them removed during daily bedside rounds or simply removing them based on our nursing-driven protocol. Currently, both critical care units have been actively working on reducing CAUTI rates and have gone 310 days without a CAUTI.

Reluctance among ICU nurses to remove urinary catheters has declined; however, it is easy to fall back on the convenience of catheters. We have found that each rise in utilization rates and CAUTIs pointed to the need to refocus our effort on the daily bedside conversations. Unless we can eliminate the need for urinary catheters, there will always be a risk of a CAUTI. However, with advances in catheter technology, alternatives to catheters, and nursing education, the reduction in this hospital-acquired infection can be realized.

Acknowledgments: The author thanks our devoted infection control manager (now director), Nina Espinoza Mazzola, BSM, CIC. Our attaining success at the bedside is a reflection of her commitment as a resource and in providing support for nursing practice.

Corresponding author: Jennifer C. Tuttle, RN, MSNEd, CNRN, Tucson Medical Center, 5301 E. Grant Rd, Tucson, AZ 85712.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Tucson Medical Center, Tucson, AZ.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a quality improvement project to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) in an intensive care unit (ICU).

- Methods: Descriptive report.

- Results: CAUTIs are a common health care–associated infection that results in increased length of stay, patient discomfort, excess health care costs, and sometime mortality. However, many cases of CAUTIs are preventable. To address this problem at our institution, we enrolled in the Hospital Engagement Network (HEN) collaborative for the reduction of CAUTIs, utilizing the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) as the platform for our project. This article describes our project implementation, challenges encountered, and the lasting improvement we have achieved at our facility.

- Conclusion: By challenging the ICU culture, providing nursing with alternatives to urinary catheters, and promoting physician engagement, we were able to reduce catheter utilization and CAUTI rates in the ICU.

Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) are important causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States [1]. Among HAIs, urinary tract infections are the 4th most common, with almost all cases caused by urethral instrumentation [2]. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) are associated with an increased hospital length of stay of 2 to 4 days and a cost of $400 million to $500 million annually [3]. As of 2015, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services no longer reimburses hospitals for treating CAUTIs.

CAUTIs are a particular challenge in the intensive care unit (ICU) due to the high urinary catheter utilization rates. In our mixed medical/surgical ICU, the catheter utilization rate was 84% in 2012 and was the setting for the majority of CAUTIs in our hospital. The risk of CAUTI can be reduced by ensuring that catheters are used only when needed and removed as soon as possible; that catheters are placed using proper aseptic technique; and that the closed sterile drainage system is maintained. In 2013 we launched a project to improve our CAUTI rates and enrolled in the Hospital Engagement Network (HEN) collaborative for the reduction of CAUTIs, utilizing the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) [4] as the platform for our project. This article describes our project implementation, the challenges we encountered, and the lasting improvement we have achieved.

Setting

Tucson Medical Center is a 600-bed tertiary care hospital, the largest in southern Arizona, with over 1000 independent medical providers. The medical center is a locally governed, nonprofit teaching hospital that has been providing care to the city of Tucson, southern Arizona, southwest New Mexico, and northern Mexico for the past 70 years. There are 2 adult critical care units: a cardiovascular ICU and a mixed medical/surgical ICU. We focused our efforts and interventions on the mixed ICU, a 16-bed unit that includes medical, surgical (neuro, general and vascular), and neurological patient populations that had 19 CAUTIs in 2012, versus 2 CAUTIs in the cardiovascular ICU.

Project

Initial Phase

The first steps in our project were to develop our unit-based team, identify project goals, and review our current nursing practice and processes. First, using the template from the CUSP platform, we assembled a team that consisted of the chief nursing officer (executive sponsor), ICU medical director, nurse manager, infection control manager, infection control nurse, 4 nurse champions (2 two night shift 2 day shift), and a patient care technician.

The second step was to identify a realistic and achievable goal. A goal of a 20% reduction from our current utilization rate was selected. As our catheter utilization rates were consistently above 90%, we aimed to for a rate of less than 70%. In addition, we sought to reduce our CAUTI standardized infection ratio (number of health care–associated infections observed divided by the national predicted number) from 3.875 to less than 1.0.

In reviewing our current nursing practice and processes, we utilized the CUSP data collection tool and adapted it to meet our institutional needs. Figure 1 shows the original CUSP data collection tool, which is organized around 5 key questions about the catheter (eg, Is catheter present? Where it was placed? Why does the patient has a catheter today?) as well as lists appropriate and inappropriate indications.

To implement the guidelines, we provided education to the nursing staff via emails, placed posters on the unit, and discussed appropriate and inappropriate indications during bedside conversations using the audit tool. As the project continued, these guidelines were reinforced daily when the question “why does your patient have a catheter today?” was posed to the nurses during the audit. Our chief nursing officer supported our implementation efforts by including a CAUTI prevention lecture with her monthly house-wide nursing education series called “lunch and learn.”

We added additional questions to the tool as we learned more about the practices and processes that were currently in use. For example, “accurate measurement of urinary output in the critically ill patient” was the most common reason given by nurses for keeping a catheter in. Upon further questioning, however, the common response was that “the doctor ordered it.” By adding “MD order” to the audit tool, we were able to track actual orders versus nurses falling back on old patterns. This data collection item also provided us the names and groups of physicians to approach and educate on our project goals. Two other helpful items added to the tool related to the catheter seal and stat lock (catheter securement device) placement. The data provided by these questions helped us recognize areas for improvement in nursing practice, supply issues, and the impact of other departments. For example, auditing showed that most of our catheters were placed in the emergency department (ED) and surgery. This gave us an opportunity to reach out to these units to discuss CAUTI reduction strategies. For example, after review of the ED catheter supplies, we discovered that they did not have a closed catheter insertion system with a urometer drainage bag. Therefore, when a patient was transferred to the ICU, the integrity of the urinary collection system had to be broken to place a urometer. Evidence has shown that breaking the integrity of the system increases a patient’s risk for a CAUTI [1]. Once this problem was identified, the ED inventory was changed to include the urometer as part of the closed system urinary insertion kit.

Active Phase

After the implementation phase, the next 15 months were dedicated to daily rounding and bedside auditing, the foundation of our project. Rounding was done by the unit manager or nurse champion and involved talking with the bedside nurse and completing the audit tool. These bedside conversations were an opportunity to review the HICPAC guidelines, identify education needs, and reinforce best practices. During these discussions, the nurses often would identify reasons to remove catheters.

The CAUTI team met monthly to review the previous month’s data, other observed opportunities for improvement, and any patient CAUTI information provided by our infection control nurse liaison. We conducted root cause analysis when CAUTIs developed, in which we reviewed the patient’s chart and sought to identify possible interventions that could have reduced the number of catheter days. Our findings were shared in staff meetings, newsletters, and through quality bulletin boards. We also recognized improved performance. Tokens that could be cashed in at the cafeteria for snacks or drinks were awarded to nurses who removed a urinary catheter. We also organized a celebration on the unit the first time we had 3 months without a CAUTI.

Challenges Encountered

Culture change is challenging. The entrenched mindset was that “If a patient is sick enough to be in an ICU, then they are sick enough to need a urinary catheter.” Standard nursing practice typically included placement of a urinary catheter immediately on arrival to the ICU if not already present. Over the years, placing a urinary catheter had become the norm in the ICU, with nurses noting concern about obtaining accurate measurement of urine output and prevention of skin breakdown from incontinence. We had to continually address these concerns to make progress on the project. By providing alternatives to urinary catheters, such as incontinence pads, external male collection devices in varying sizes, moisture barrier products, and scales to measure urine output, nurses were more willing to comply with catheter removal.

We worked with our wound and ostomy nurses to ensure we were providing the proper moisture barrier products and presented research to support that incontinence did not need to lead to pressure ulcers. The wound care team helped with guiding the use of products for incontinent patients to prevent incontinence-associated dermatitis and potential skin breakdown. Our administration financially supported our program, allowing us to bring in and trial supplies. As we identified products for use, we were able to place them into floor stock and make them easily available to nursing. Items such as wicking pads, skin protective creams, and alternatives to catheters were a vital part of our bedside toolkit to maintain our patient’s skin integrity.

Both nurses and physicians were concerned about accurate measurement of output, specifically in surgical patients. The use of scales to weigh and measure output from an incontinent patient’s pads was helpful but sometimes inconvenient. From our surgeons' perspective, not having immediate hourly measurements of urine output to monitor risk for hypovolemia from third spacing of fluid or from abdominal compartment syndrome was not acceptable. Because of this concern, we did not see a decrease in early catheter removal among surgical patients. Daily conversations with nurses and surgeons at the bedside continue to be key to removing catheters as soon as the surgeon is comfortable that the patient is out of risk for hypovolemia.

Outcomes

Within the first month we saw an immediate drop in catheter utilization and had zero CAUTIs, but during the next 2 months there was a return to our previous rates (Figure 2 and Figure 3 [figures show combined mixed and cardiovascular ICU rates due to reporting requirements]).

Although nursing is at the heart of this engagement, it is the combined efforts of all disciplines that promote the reduction of CAUTIs and improve patient outcomes. When our CAUTI counts plateaued at 10 annually in 2014–2015, we reached out to physicians and found that we had not adequately educated our medical and surgical staff of our project and goals. With the backing of a supportive and vocal ICU director, physician engagement has increased and there is more attention paid to catheter removal by our ICU intensivists. This collaborative approach has helped lower our rates even further in 2016 (n = 3). We achieved our CAUTI SIR goal of less than 1.0 , and changed our current goal to less than 0.5 (Figure 3).

In addition to greater intensivist engagement, the ED reduced their urinary catheter insertion rate from 12% to 4% for all patients transferring to an inpatient status. As previously mentioned, they are now placing catheters from kits that include urometers, so we do not have to break the integrity of the closed system after the patient it transferred to the ICU. We are also collaborating with surgical services to reduce catheter use. This is still a work in progress that requires collaboration with surgeons and hospitalists in changing departmental norms.

Conclusion

Through a combined effort involving a number of departments across the hospital, we were able to reduce catheter utilization and CAUTI rates in the ICU. We have seen a culture shift, with more ICU nursing staff questioning the use of catheters and requesting to have them removed during daily bedside rounds or simply removing them based on our nursing-driven protocol. Currently, both critical care units have been actively working on reducing CAUTI rates and have gone 310 days without a CAUTI.

Reluctance among ICU nurses to remove urinary catheters has declined; however, it is easy to fall back on the convenience of catheters. We have found that each rise in utilization rates and CAUTIs pointed to the need to refocus our effort on the daily bedside conversations. Unless we can eliminate the need for urinary catheters, there will always be a risk of a CAUTI. However, with advances in catheter technology, alternatives to catheters, and nursing education, the reduction in this hospital-acquired infection can be realized.

Acknowledgments: The author thanks our devoted infection control manager (now director), Nina Espinoza Mazzola, BSM, CIC. Our attaining success at the bedside is a reflection of her commitment as a resource and in providing support for nursing practice.

Corresponding author: Jennifer C. Tuttle, RN, MSNEd, CNRN, Tucson Medical Center, 5301 E. Grant Rd, Tucson, AZ 85712.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Nicolle LE. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2014;3:23.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Urinary tract infection (catheter-associated urinary tract infection [cauti] and non-catheter-associated urinary tract infection [uti]) and other urinary system infection [usi]) events. 2017. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/7psccauticurrent.pdf.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (cauti) toolkit. Accessed 5 Mar 2017 at www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/toolkits/CAUTItoolkit_3_10.pdf.

4. On the CUSP implementation guide. Accessed at http://web.mhanet.com/cauti-implementation_guide_508.pdf.

5. Healthcare Infection Control Practice Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guidelines for the prevention of catheter associated urinary tract infections 2009. Accessed 25 Feb 2017 at www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/cauti-guidelines.pdf.

1. Nicolle LE. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2014;3:23.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Urinary tract infection (catheter-associated urinary tract infection [cauti] and non-catheter-associated urinary tract infection [uti]) and other urinary system infection [usi]) events. 2017. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/7psccauticurrent.pdf.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (cauti) toolkit. Accessed 5 Mar 2017 at www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/toolkits/CAUTItoolkit_3_10.pdf.

4. On the CUSP implementation guide. Accessed at http://web.mhanet.com/cauti-implementation_guide_508.pdf.

5. Healthcare Infection Control Practice Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guidelines for the prevention of catheter associated urinary tract infections 2009. Accessed 25 Feb 2017 at www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/cauti-guidelines.pdf.