User login

With health care costs increasing and economic resources diminishing, substantial efforts have been directed toward improving the quality of care delivered in a cost-effective manner. For a total hip arthroplasty (THA) performed in the United States between 1997 and 2001, total hospital cost, including direct and indirect costs, was estimated as averaging $13,339.1 In 2012, this cost was estimated to be between $43,000 and $100,000.2 This overall cost estimate, along with the rate at which the procedure is performed, may present an opportunity for cost savings.

Length of hospital stay (LHS) is an important outcome measure that has been assessed for optimal health care delivery. Prolonged LHS implies increased resource expenditure. Therefore, it is crucial to identify factors associated with prolonged LHS in order to reduce costs. Investigations have identified factors shown to affect LHS after THA. These factors include advanced age, medical comorbidities, obesity, intraoperative time, anesthesia technique, surgical site infection, and incision length.3-7

We conducted a study to identify the patient and clinical factors that affect LHS and to determine whether the specific day of the week when primary THA is performed affects LHS at a large tertiary-care university-based medical center. This information may prove valuable to hospital planning committees allotting operating room time and floor staffing for elective surgical cases with the goal of delivering cost-efficient care.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively analyzed all primary unilateral THAs (273 patients) performed at our institution, a tertiary-care teaching hospital, between January 2010 and May 2011. The majority of the surgeries were performed through a posterior approach, and a majority of the implants were uncemented. All patients followed the same postoperative clinical pathway; no fast-track pathway was used.

The combined effects of day of surgery, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, anesthesia type, intraoperative time, estimated blood loss (EBL), incision length, presence of complications, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), disposition (skilled nursing facility vs home), transfusion, hematocrit, and hemoglobin on LHS were analyzed using a multiple quasi-Poisson regression model that included a random effect for surgeon. A Poisson regression model (typically used for count data) was deemed appropriate, as LHS was reported in whole days; a quasi-Poisson model relaxes the Poisson model assumption that the variance in the data equals the mean. The random effect for surgeon adjusts for any correlation among data from surgeries conducted by the same surgeon.

All complications were recorded. Complications included excess wound drainage,8 wound hematoma (a case of excess wound drainage necessitated surgical irrigation and débridement), new-onset atrial fibrillation, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, atrial flutter, urinary tract infection, pulmonary embolism, disseminated intravascular coagulation, hepatic decompensation as manifested by elevated liver enzymes, pneumonia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastric ulcer, sepsis, delirium, hypotension, and dysphagia.

The parameter estimates reported from the quasi-Poisson regression model are incident rate ratios (IRRs). IRR represents the change in expected LHS for a 1-unit change in a continuous variable (eg, age) or between categories of a categorical variable (eg, sex). IRR higher than 1 indicates higher risk as the continuous variable increases or a higher risk relative to the comparator group for a categorical variable. IRR lower than 1 indicates lower risk.

Results

Table 1 summarizes patient characteristics by surgical day. Mean LHS ranged from a minimum of 3.7 days for patients who had surgery on a Monday to a maximum of 4.2 days for patients who had surgery on a Thursday.

Table 2 summarizes results of the multivariate quasi-Poisson regression analysis of LHS by surgical day, ASA grade, anesthesia type, intraoperative time, EBL, incision length, presence of complications, age, sex, and BMI. With all other variables included in the model adjusted for, each additional point in ASA grade was associated with a 12% increase in LHS (P = .019). In addition, with all other variables included in the model adjusted for, LHS was 33% longer for patients with complications than for patients without complications (P < .001) and 12% longer for patients who received transfusions than for patients who did not (P = .046). LHS did not differ significantly by the day of the week when the surgery was performed (P = .496). Disposition status (skilled nursing facility vs home) as a variable to determine LHS did approach statistical significance (P = .061). As the effect size we were interested in detecting was an approximate 1-day increase in LHS for patients who had surgery later in the week relative to patients who had surgery earlier in the week, our sample size was adequate (range of required sample size, 200-300 patients). This study had 99% power to detect a 27% increase in LHS (equivalent to 1 day or more).

Discussion

This retrospective analysis explored how day of the week of primary THA affected LHS. Various confounders, such as surgery and patient factors, were also examined so that the multivariate analysis would be able to isolate the effects of surgical day of the week on LHS.

Effect of day of the week of primary THA on LHS was not investigated in the United States before. In Denmark, in a study similar to ours, Husted and colleagues4 found a 400% increase in the probability of LHS of more than 3 days when patients operated on a Thursday were compared with patients operated on a Friday. The authors reasoned that the Thursday patients most likely had a compromised physical therapy protocol owing to the inclusion of weekend days in the crucial postoperative period. LHS was consequently increased so that these patients would achieve their therapy goals before being discharged. Our investigation showed that LHS did not differ significantly by surgical day of the week. Although patients who had THA on a Thursday had 15% longer LHS than patients who had THA on a Monday, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .496), even though the study was adequately powered to detect a change in LHS of a whole day.

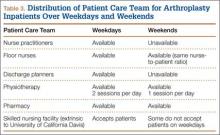

Table 3 summarizes the difference in quantum of workforce on weekdays and weekends at our center. The physiotherapy sessions were reduced to 1 per day. Nurse practitioners and discharge planners were not available on weekends, and some skilled nursing facilities and rehabilitation centers refused to accept patients on weekends. At our center, a teaching institute, the clinical duties of discharge planners and nurse practitioners were assumed by licensed physicians (orthopedic residents covering the arthroplasty team on weekends). This could be one of several possible reasons our study failed to detect statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. This kind of alternative arrangement may not be possible at many other centers. However, our study results provide a reasonably accurate logistical aim with regard to workforce availability on weekends to keep LHS in check.

The importance of giving patients an inpatient physical therapy regimen in timely fashion has been demonstrated in other studies. Munin and colleagues,9 in a randomized controlled trial, evaluated 71 patients who underwent elective hip and knee arthroplasty and received 2 different physical therapy regimens. Patients started their in-treatment physical therapy on postoperative day 3 or 7. Mean total LHS was shorter in the 3-day group (11.7 days) than in the 7-day group (14.5 days) (P < .001). Brusco and colleagues10 also showed that introducing weekend physical therapy services significantly reduced LHS in patients who underwent THA (10.6 vs 12.5 days; P < .05). Rapoport and Judd-Van Eerd11 retrospectively analyzed orthopedic surgery LHS, comparing patients treated in a community hospital during a period of 5-days-a-week physical therapy coverage and patients treated during a period of 7-days-a-week physical therapy coverage. The 7-days-a-week group had significantly statistically shorter mean LHS.

Another rationale for analyzing the impact of surgical day of the week stems from the expectation that patients who undergo THA on Wednesday or Thursday and are scheduled to have physical therapy or be discharged on the weekend may be affected not only by reduced inpatient weekend physical therapy coverage but also by difficulties in being transferred to a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation center if not discharged home. In our study, the patients who were to be discharged to a rehabilitation center were delayed by 12.5%, and this statistic trended toward significance (P = .061). Our literature search did not turn up any studies, US or European, specifically linking LHS to discharge disposition (whether patient is discharged home or to a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation center).

Reduced medical staffing on weekends may not only affect the quality of in-hospital patient care but may also result in unnecessary delays in discharge. Chow and Szeto12 retrospectively analyzed the medical records of all acute medical wards in a university hospital and compared weekend discharge rates before and after implementation of a work ordinance, which decreased the physician workforce by half on Saturday and Sunday. Results showed a 2.7% decrease in the weekend discharge rate after the work ordinance was established. The number of weekday discharges between the 2 time periods did not differ. Increasing the workforce availability presents a challenge in academic medical centers where graduate medical education enforces a strict cap on resident duty hours. Under these circumstances, a more feasible approach to decreasing LHS for THA patients is for surgical planning committees to provide the joint replacement services with operative block times early in the workweek.

Even though the organizational structure at our center is strong enough to provide for an adequate weekend workforce to discharge these patients, this study had a few limitations. We could not study readmission rates and whether the transition to home health and home physical therapy for the patients who went home was seamless.

We found that only 3 patient characteristics had a significant effect on LHS: higher ASA grade (a surrogate for medical comorbidities), requirement for blood transfusion, and presence of complications. In Denmark, blood transfusion increased the likelihood of longer LHS by 400%.4 In that study, patients who were ASA grades 1 and 2 had 60% and 20% decreased likelihood of LHS of more than 3 days compared with patients who were ASA grade 3. Similarly, in 2009, Mears and colleagues5 found 4 factors related to increased LHS: female sex (P < .001), older age (P < .001), higher ASA grade (3, P < .01; 4, P < .001), and increased blood loss (P < .001).5

Conclusion

Over the past decade, there has been a significant reduction in LHS after THA, from a mean of 3 weeks to 4 days. Advances in implant technology, delivery of in-home physical therapy, and improved prevention and management of postoperative complications have contributed to this decline. Early identification of patients with transfusion requirements may be helpful in expediting their care. Although guidelines are in place for transfusion, further study in this regard may be needed. It is important to continue to identify surgery and patient factors that affect LHS, but the importance of organizational and planning issues in optimizing hospital health care expenditures cannot be ignored. Further study of providing a specific discharge planning service to identify patients’ discharge needs (home vs extended care facility) may help reduce LHS.

1. Antoniou J, Martineau PA, Filion KB, et al. In-hospital cost of total hip arthroplasty in Canada and the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(11):2435-2439.

2. Kumar S, Breuing R, Chahal R. Globalization of health care delivery in the United States through medical tourism. J Health Commun. 2012;17(2):177-198.

3. Foote J, Panchoo K, Blair P, Bannister G. Length of stay following primary total hip replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91(6):500-504.

4. Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):168-173.

5. Mears DC, Mears SC, Chelly JE, Dai F, Vulakovich KL. THA with a minimally invasive technique, multi-modal anesthesia, and home rehabilitation: factors associated with early discharge? Clin Orthop. 2009;467(6):1412-1417.

6. Peck CN, Foster A, McLauchlan GJ. Reducing incision length or intensifying rehabilitation: what makes the difference to length of stay in total hip replacement in a UK setting? Int Orthop. 2006;30(5):395-398.

7. Weaver F, Hynes D, Hopkinson W, et al. Preoperative risks and outcomes of hip and knee arthroplasty in the Veterans Health Administration. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(6):693-708.

8. Patel VP, Walsh M, Sehgal B, Preston C, DeWal H, Di Cesare PE. Factors associated with prolonged wound drainage after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):33-38.

9. Munin MC, Rudy TE, Glynn NW, Crossett LS, Rubash HE. Early inpatient rehabilitation after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. JAMA. 1998;279(11):847-852.

10. Brusco NK, Shields N, Taylor NF, Paratz J. A Saturday physiotherapy service may decrease length of stay in patients undergoing rehabilitation in hospital: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother. 2007;53(2):75-81.

11. Rapoport J, Judd-Van Eerd M. Impact of physical therapy weekend coverage on length of stay in an acute care community hospital. Phys Ther. 1989;69(1):32-37.

12. Chow KM, Szeto CC. Impact of enforcing the Labour Ordinance, with 1-in-7-day off for hospital doctors, on weekend hospital discharge rate. J Public Health (Oxf). 2005;27(2):189-191.

With health care costs increasing and economic resources diminishing, substantial efforts have been directed toward improving the quality of care delivered in a cost-effective manner. For a total hip arthroplasty (THA) performed in the United States between 1997 and 2001, total hospital cost, including direct and indirect costs, was estimated as averaging $13,339.1 In 2012, this cost was estimated to be between $43,000 and $100,000.2 This overall cost estimate, along with the rate at which the procedure is performed, may present an opportunity for cost savings.

Length of hospital stay (LHS) is an important outcome measure that has been assessed for optimal health care delivery. Prolonged LHS implies increased resource expenditure. Therefore, it is crucial to identify factors associated with prolonged LHS in order to reduce costs. Investigations have identified factors shown to affect LHS after THA. These factors include advanced age, medical comorbidities, obesity, intraoperative time, anesthesia technique, surgical site infection, and incision length.3-7

We conducted a study to identify the patient and clinical factors that affect LHS and to determine whether the specific day of the week when primary THA is performed affects LHS at a large tertiary-care university-based medical center. This information may prove valuable to hospital planning committees allotting operating room time and floor staffing for elective surgical cases with the goal of delivering cost-efficient care.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively analyzed all primary unilateral THAs (273 patients) performed at our institution, a tertiary-care teaching hospital, between January 2010 and May 2011. The majority of the surgeries were performed through a posterior approach, and a majority of the implants were uncemented. All patients followed the same postoperative clinical pathway; no fast-track pathway was used.

The combined effects of day of surgery, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, anesthesia type, intraoperative time, estimated blood loss (EBL), incision length, presence of complications, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), disposition (skilled nursing facility vs home), transfusion, hematocrit, and hemoglobin on LHS were analyzed using a multiple quasi-Poisson regression model that included a random effect for surgeon. A Poisson regression model (typically used for count data) was deemed appropriate, as LHS was reported in whole days; a quasi-Poisson model relaxes the Poisson model assumption that the variance in the data equals the mean. The random effect for surgeon adjusts for any correlation among data from surgeries conducted by the same surgeon.

All complications were recorded. Complications included excess wound drainage,8 wound hematoma (a case of excess wound drainage necessitated surgical irrigation and débridement), new-onset atrial fibrillation, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, atrial flutter, urinary tract infection, pulmonary embolism, disseminated intravascular coagulation, hepatic decompensation as manifested by elevated liver enzymes, pneumonia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastric ulcer, sepsis, delirium, hypotension, and dysphagia.

The parameter estimates reported from the quasi-Poisson regression model are incident rate ratios (IRRs). IRR represents the change in expected LHS for a 1-unit change in a continuous variable (eg, age) or between categories of a categorical variable (eg, sex). IRR higher than 1 indicates higher risk as the continuous variable increases or a higher risk relative to the comparator group for a categorical variable. IRR lower than 1 indicates lower risk.

Results

Table 1 summarizes patient characteristics by surgical day. Mean LHS ranged from a minimum of 3.7 days for patients who had surgery on a Monday to a maximum of 4.2 days for patients who had surgery on a Thursday.

Table 2 summarizes results of the multivariate quasi-Poisson regression analysis of LHS by surgical day, ASA grade, anesthesia type, intraoperative time, EBL, incision length, presence of complications, age, sex, and BMI. With all other variables included in the model adjusted for, each additional point in ASA grade was associated with a 12% increase in LHS (P = .019). In addition, with all other variables included in the model adjusted for, LHS was 33% longer for patients with complications than for patients without complications (P < .001) and 12% longer for patients who received transfusions than for patients who did not (P = .046). LHS did not differ significantly by the day of the week when the surgery was performed (P = .496). Disposition status (skilled nursing facility vs home) as a variable to determine LHS did approach statistical significance (P = .061). As the effect size we were interested in detecting was an approximate 1-day increase in LHS for patients who had surgery later in the week relative to patients who had surgery earlier in the week, our sample size was adequate (range of required sample size, 200-300 patients). This study had 99% power to detect a 27% increase in LHS (equivalent to 1 day or more).

Discussion

This retrospective analysis explored how day of the week of primary THA affected LHS. Various confounders, such as surgery and patient factors, were also examined so that the multivariate analysis would be able to isolate the effects of surgical day of the week on LHS.

Effect of day of the week of primary THA on LHS was not investigated in the United States before. In Denmark, in a study similar to ours, Husted and colleagues4 found a 400% increase in the probability of LHS of more than 3 days when patients operated on a Thursday were compared with patients operated on a Friday. The authors reasoned that the Thursday patients most likely had a compromised physical therapy protocol owing to the inclusion of weekend days in the crucial postoperative period. LHS was consequently increased so that these patients would achieve their therapy goals before being discharged. Our investigation showed that LHS did not differ significantly by surgical day of the week. Although patients who had THA on a Thursday had 15% longer LHS than patients who had THA on a Monday, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .496), even though the study was adequately powered to detect a change in LHS of a whole day.

Table 3 summarizes the difference in quantum of workforce on weekdays and weekends at our center. The physiotherapy sessions were reduced to 1 per day. Nurse practitioners and discharge planners were not available on weekends, and some skilled nursing facilities and rehabilitation centers refused to accept patients on weekends. At our center, a teaching institute, the clinical duties of discharge planners and nurse practitioners were assumed by licensed physicians (orthopedic residents covering the arthroplasty team on weekends). This could be one of several possible reasons our study failed to detect statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. This kind of alternative arrangement may not be possible at many other centers. However, our study results provide a reasonably accurate logistical aim with regard to workforce availability on weekends to keep LHS in check.

The importance of giving patients an inpatient physical therapy regimen in timely fashion has been demonstrated in other studies. Munin and colleagues,9 in a randomized controlled trial, evaluated 71 patients who underwent elective hip and knee arthroplasty and received 2 different physical therapy regimens. Patients started their in-treatment physical therapy on postoperative day 3 or 7. Mean total LHS was shorter in the 3-day group (11.7 days) than in the 7-day group (14.5 days) (P < .001). Brusco and colleagues10 also showed that introducing weekend physical therapy services significantly reduced LHS in patients who underwent THA (10.6 vs 12.5 days; P < .05). Rapoport and Judd-Van Eerd11 retrospectively analyzed orthopedic surgery LHS, comparing patients treated in a community hospital during a period of 5-days-a-week physical therapy coverage and patients treated during a period of 7-days-a-week physical therapy coverage. The 7-days-a-week group had significantly statistically shorter mean LHS.

Another rationale for analyzing the impact of surgical day of the week stems from the expectation that patients who undergo THA on Wednesday or Thursday and are scheduled to have physical therapy or be discharged on the weekend may be affected not only by reduced inpatient weekend physical therapy coverage but also by difficulties in being transferred to a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation center if not discharged home. In our study, the patients who were to be discharged to a rehabilitation center were delayed by 12.5%, and this statistic trended toward significance (P = .061). Our literature search did not turn up any studies, US or European, specifically linking LHS to discharge disposition (whether patient is discharged home or to a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation center).

Reduced medical staffing on weekends may not only affect the quality of in-hospital patient care but may also result in unnecessary delays in discharge. Chow and Szeto12 retrospectively analyzed the medical records of all acute medical wards in a university hospital and compared weekend discharge rates before and after implementation of a work ordinance, which decreased the physician workforce by half on Saturday and Sunday. Results showed a 2.7% decrease in the weekend discharge rate after the work ordinance was established. The number of weekday discharges between the 2 time periods did not differ. Increasing the workforce availability presents a challenge in academic medical centers where graduate medical education enforces a strict cap on resident duty hours. Under these circumstances, a more feasible approach to decreasing LHS for THA patients is for surgical planning committees to provide the joint replacement services with operative block times early in the workweek.

Even though the organizational structure at our center is strong enough to provide for an adequate weekend workforce to discharge these patients, this study had a few limitations. We could not study readmission rates and whether the transition to home health and home physical therapy for the patients who went home was seamless.

We found that only 3 patient characteristics had a significant effect on LHS: higher ASA grade (a surrogate for medical comorbidities), requirement for blood transfusion, and presence of complications. In Denmark, blood transfusion increased the likelihood of longer LHS by 400%.4 In that study, patients who were ASA grades 1 and 2 had 60% and 20% decreased likelihood of LHS of more than 3 days compared with patients who were ASA grade 3. Similarly, in 2009, Mears and colleagues5 found 4 factors related to increased LHS: female sex (P < .001), older age (P < .001), higher ASA grade (3, P < .01; 4, P < .001), and increased blood loss (P < .001).5

Conclusion

Over the past decade, there has been a significant reduction in LHS after THA, from a mean of 3 weeks to 4 days. Advances in implant technology, delivery of in-home physical therapy, and improved prevention and management of postoperative complications have contributed to this decline. Early identification of patients with transfusion requirements may be helpful in expediting their care. Although guidelines are in place for transfusion, further study in this regard may be needed. It is important to continue to identify surgery and patient factors that affect LHS, but the importance of organizational and planning issues in optimizing hospital health care expenditures cannot be ignored. Further study of providing a specific discharge planning service to identify patients’ discharge needs (home vs extended care facility) may help reduce LHS.

With health care costs increasing and economic resources diminishing, substantial efforts have been directed toward improving the quality of care delivered in a cost-effective manner. For a total hip arthroplasty (THA) performed in the United States between 1997 and 2001, total hospital cost, including direct and indirect costs, was estimated as averaging $13,339.1 In 2012, this cost was estimated to be between $43,000 and $100,000.2 This overall cost estimate, along with the rate at which the procedure is performed, may present an opportunity for cost savings.

Length of hospital stay (LHS) is an important outcome measure that has been assessed for optimal health care delivery. Prolonged LHS implies increased resource expenditure. Therefore, it is crucial to identify factors associated with prolonged LHS in order to reduce costs. Investigations have identified factors shown to affect LHS after THA. These factors include advanced age, medical comorbidities, obesity, intraoperative time, anesthesia technique, surgical site infection, and incision length.3-7

We conducted a study to identify the patient and clinical factors that affect LHS and to determine whether the specific day of the week when primary THA is performed affects LHS at a large tertiary-care university-based medical center. This information may prove valuable to hospital planning committees allotting operating room time and floor staffing for elective surgical cases with the goal of delivering cost-efficient care.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively analyzed all primary unilateral THAs (273 patients) performed at our institution, a tertiary-care teaching hospital, between January 2010 and May 2011. The majority of the surgeries were performed through a posterior approach, and a majority of the implants were uncemented. All patients followed the same postoperative clinical pathway; no fast-track pathway was used.

The combined effects of day of surgery, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, anesthesia type, intraoperative time, estimated blood loss (EBL), incision length, presence of complications, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), disposition (skilled nursing facility vs home), transfusion, hematocrit, and hemoglobin on LHS were analyzed using a multiple quasi-Poisson regression model that included a random effect for surgeon. A Poisson regression model (typically used for count data) was deemed appropriate, as LHS was reported in whole days; a quasi-Poisson model relaxes the Poisson model assumption that the variance in the data equals the mean. The random effect for surgeon adjusts for any correlation among data from surgeries conducted by the same surgeon.

All complications were recorded. Complications included excess wound drainage,8 wound hematoma (a case of excess wound drainage necessitated surgical irrigation and débridement), new-onset atrial fibrillation, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, atrial flutter, urinary tract infection, pulmonary embolism, disseminated intravascular coagulation, hepatic decompensation as manifested by elevated liver enzymes, pneumonia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastric ulcer, sepsis, delirium, hypotension, and dysphagia.

The parameter estimates reported from the quasi-Poisson regression model are incident rate ratios (IRRs). IRR represents the change in expected LHS for a 1-unit change in a continuous variable (eg, age) or between categories of a categorical variable (eg, sex). IRR higher than 1 indicates higher risk as the continuous variable increases or a higher risk relative to the comparator group for a categorical variable. IRR lower than 1 indicates lower risk.

Results

Table 1 summarizes patient characteristics by surgical day. Mean LHS ranged from a minimum of 3.7 days for patients who had surgery on a Monday to a maximum of 4.2 days for patients who had surgery on a Thursday.

Table 2 summarizes results of the multivariate quasi-Poisson regression analysis of LHS by surgical day, ASA grade, anesthesia type, intraoperative time, EBL, incision length, presence of complications, age, sex, and BMI. With all other variables included in the model adjusted for, each additional point in ASA grade was associated with a 12% increase in LHS (P = .019). In addition, with all other variables included in the model adjusted for, LHS was 33% longer for patients with complications than for patients without complications (P < .001) and 12% longer for patients who received transfusions than for patients who did not (P = .046). LHS did not differ significantly by the day of the week when the surgery was performed (P = .496). Disposition status (skilled nursing facility vs home) as a variable to determine LHS did approach statistical significance (P = .061). As the effect size we were interested in detecting was an approximate 1-day increase in LHS for patients who had surgery later in the week relative to patients who had surgery earlier in the week, our sample size was adequate (range of required sample size, 200-300 patients). This study had 99% power to detect a 27% increase in LHS (equivalent to 1 day or more).

Discussion

This retrospective analysis explored how day of the week of primary THA affected LHS. Various confounders, such as surgery and patient factors, were also examined so that the multivariate analysis would be able to isolate the effects of surgical day of the week on LHS.

Effect of day of the week of primary THA on LHS was not investigated in the United States before. In Denmark, in a study similar to ours, Husted and colleagues4 found a 400% increase in the probability of LHS of more than 3 days when patients operated on a Thursday were compared with patients operated on a Friday. The authors reasoned that the Thursday patients most likely had a compromised physical therapy protocol owing to the inclusion of weekend days in the crucial postoperative period. LHS was consequently increased so that these patients would achieve their therapy goals before being discharged. Our investigation showed that LHS did not differ significantly by surgical day of the week. Although patients who had THA on a Thursday had 15% longer LHS than patients who had THA on a Monday, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .496), even though the study was adequately powered to detect a change in LHS of a whole day.

Table 3 summarizes the difference in quantum of workforce on weekdays and weekends at our center. The physiotherapy sessions were reduced to 1 per day. Nurse practitioners and discharge planners were not available on weekends, and some skilled nursing facilities and rehabilitation centers refused to accept patients on weekends. At our center, a teaching institute, the clinical duties of discharge planners and nurse practitioners were assumed by licensed physicians (orthopedic residents covering the arthroplasty team on weekends). This could be one of several possible reasons our study failed to detect statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. This kind of alternative arrangement may not be possible at many other centers. However, our study results provide a reasonably accurate logistical aim with regard to workforce availability on weekends to keep LHS in check.

The importance of giving patients an inpatient physical therapy regimen in timely fashion has been demonstrated in other studies. Munin and colleagues,9 in a randomized controlled trial, evaluated 71 patients who underwent elective hip and knee arthroplasty and received 2 different physical therapy regimens. Patients started their in-treatment physical therapy on postoperative day 3 or 7. Mean total LHS was shorter in the 3-day group (11.7 days) than in the 7-day group (14.5 days) (P < .001). Brusco and colleagues10 also showed that introducing weekend physical therapy services significantly reduced LHS in patients who underwent THA (10.6 vs 12.5 days; P < .05). Rapoport and Judd-Van Eerd11 retrospectively analyzed orthopedic surgery LHS, comparing patients treated in a community hospital during a period of 5-days-a-week physical therapy coverage and patients treated during a period of 7-days-a-week physical therapy coverage. The 7-days-a-week group had significantly statistically shorter mean LHS.

Another rationale for analyzing the impact of surgical day of the week stems from the expectation that patients who undergo THA on Wednesday or Thursday and are scheduled to have physical therapy or be discharged on the weekend may be affected not only by reduced inpatient weekend physical therapy coverage but also by difficulties in being transferred to a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation center if not discharged home. In our study, the patients who were to be discharged to a rehabilitation center were delayed by 12.5%, and this statistic trended toward significance (P = .061). Our literature search did not turn up any studies, US or European, specifically linking LHS to discharge disposition (whether patient is discharged home or to a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation center).

Reduced medical staffing on weekends may not only affect the quality of in-hospital patient care but may also result in unnecessary delays in discharge. Chow and Szeto12 retrospectively analyzed the medical records of all acute medical wards in a university hospital and compared weekend discharge rates before and after implementation of a work ordinance, which decreased the physician workforce by half on Saturday and Sunday. Results showed a 2.7% decrease in the weekend discharge rate after the work ordinance was established. The number of weekday discharges between the 2 time periods did not differ. Increasing the workforce availability presents a challenge in academic medical centers where graduate medical education enforces a strict cap on resident duty hours. Under these circumstances, a more feasible approach to decreasing LHS for THA patients is for surgical planning committees to provide the joint replacement services with operative block times early in the workweek.

Even though the organizational structure at our center is strong enough to provide for an adequate weekend workforce to discharge these patients, this study had a few limitations. We could not study readmission rates and whether the transition to home health and home physical therapy for the patients who went home was seamless.

We found that only 3 patient characteristics had a significant effect on LHS: higher ASA grade (a surrogate for medical comorbidities), requirement for blood transfusion, and presence of complications. In Denmark, blood transfusion increased the likelihood of longer LHS by 400%.4 In that study, patients who were ASA grades 1 and 2 had 60% and 20% decreased likelihood of LHS of more than 3 days compared with patients who were ASA grade 3. Similarly, in 2009, Mears and colleagues5 found 4 factors related to increased LHS: female sex (P < .001), older age (P < .001), higher ASA grade (3, P < .01; 4, P < .001), and increased blood loss (P < .001).5

Conclusion

Over the past decade, there has been a significant reduction in LHS after THA, from a mean of 3 weeks to 4 days. Advances in implant technology, delivery of in-home physical therapy, and improved prevention and management of postoperative complications have contributed to this decline. Early identification of patients with transfusion requirements may be helpful in expediting their care. Although guidelines are in place for transfusion, further study in this regard may be needed. It is important to continue to identify surgery and patient factors that affect LHS, but the importance of organizational and planning issues in optimizing hospital health care expenditures cannot be ignored. Further study of providing a specific discharge planning service to identify patients’ discharge needs (home vs extended care facility) may help reduce LHS.

1. Antoniou J, Martineau PA, Filion KB, et al. In-hospital cost of total hip arthroplasty in Canada and the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(11):2435-2439.

2. Kumar S, Breuing R, Chahal R. Globalization of health care delivery in the United States through medical tourism. J Health Commun. 2012;17(2):177-198.

3. Foote J, Panchoo K, Blair P, Bannister G. Length of stay following primary total hip replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91(6):500-504.

4. Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):168-173.

5. Mears DC, Mears SC, Chelly JE, Dai F, Vulakovich KL. THA with a minimally invasive technique, multi-modal anesthesia, and home rehabilitation: factors associated with early discharge? Clin Orthop. 2009;467(6):1412-1417.

6. Peck CN, Foster A, McLauchlan GJ. Reducing incision length or intensifying rehabilitation: what makes the difference to length of stay in total hip replacement in a UK setting? Int Orthop. 2006;30(5):395-398.

7. Weaver F, Hynes D, Hopkinson W, et al. Preoperative risks and outcomes of hip and knee arthroplasty in the Veterans Health Administration. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(6):693-708.

8. Patel VP, Walsh M, Sehgal B, Preston C, DeWal H, Di Cesare PE. Factors associated with prolonged wound drainage after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):33-38.

9. Munin MC, Rudy TE, Glynn NW, Crossett LS, Rubash HE. Early inpatient rehabilitation after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. JAMA. 1998;279(11):847-852.

10. Brusco NK, Shields N, Taylor NF, Paratz J. A Saturday physiotherapy service may decrease length of stay in patients undergoing rehabilitation in hospital: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother. 2007;53(2):75-81.

11. Rapoport J, Judd-Van Eerd M. Impact of physical therapy weekend coverage on length of stay in an acute care community hospital. Phys Ther. 1989;69(1):32-37.

12. Chow KM, Szeto CC. Impact of enforcing the Labour Ordinance, with 1-in-7-day off for hospital doctors, on weekend hospital discharge rate. J Public Health (Oxf). 2005;27(2):189-191.

1. Antoniou J, Martineau PA, Filion KB, et al. In-hospital cost of total hip arthroplasty in Canada and the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(11):2435-2439.

2. Kumar S, Breuing R, Chahal R. Globalization of health care delivery in the United States through medical tourism. J Health Commun. 2012;17(2):177-198.

3. Foote J, Panchoo K, Blair P, Bannister G. Length of stay following primary total hip replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91(6):500-504.

4. Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):168-173.

5. Mears DC, Mears SC, Chelly JE, Dai F, Vulakovich KL. THA with a minimally invasive technique, multi-modal anesthesia, and home rehabilitation: factors associated with early discharge? Clin Orthop. 2009;467(6):1412-1417.

6. Peck CN, Foster A, McLauchlan GJ. Reducing incision length or intensifying rehabilitation: what makes the difference to length of stay in total hip replacement in a UK setting? Int Orthop. 2006;30(5):395-398.

7. Weaver F, Hynes D, Hopkinson W, et al. Preoperative risks and outcomes of hip and knee arthroplasty in the Veterans Health Administration. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(6):693-708.

8. Patel VP, Walsh M, Sehgal B, Preston C, DeWal H, Di Cesare PE. Factors associated with prolonged wound drainage after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):33-38.

9. Munin MC, Rudy TE, Glynn NW, Crossett LS, Rubash HE. Early inpatient rehabilitation after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. JAMA. 1998;279(11):847-852.

10. Brusco NK, Shields N, Taylor NF, Paratz J. A Saturday physiotherapy service may decrease length of stay in patients undergoing rehabilitation in hospital: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother. 2007;53(2):75-81.

11. Rapoport J, Judd-Van Eerd M. Impact of physical therapy weekend coverage on length of stay in an acute care community hospital. Phys Ther. 1989;69(1):32-37.

12. Chow KM, Szeto CC. Impact of enforcing the Labour Ordinance, with 1-in-7-day off for hospital doctors, on weekend hospital discharge rate. J Public Health (Oxf). 2005;27(2):189-191.