User login

From the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA (Ms. Willard-Grace, Dr. Sharma, Dr. Potter) and the California Primary Care Association, Sacramento, CA (Ms. Parker).

Abstract

- Objective: To explore how community health centers engage patients in practice improvement and factors associated with patient involvement on clinic-level strategies, policies, and programs.

- Methods: Cross-sectional web-based survey of community health centers in California, Arizona, Nevada, and Hawaii (n = 97).

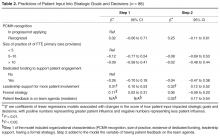

- Results: The most common mechanisms used by community health centers to obtain patient feedback were surveys (94%; 91/97) and advisory councils (69%; 67/97). Patient-centered medical home recognition and dedicated funding for patient engagement activities were not associated with reported patient influence on the clinic’s strategic goals, policies, or programs. When other factors were controlled for in multivariable modeling, leadership support (β = 0.31, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.10–0.53) and having a formal strategy to identify and engage patients as advisors (β = 0.17, 95% CI 0.02–0.31) were positively associated with patient influence on strategic goals. Having a formal strategy to identify and engage patients also was associated with patient impact on polices and programss (β = 0.17, 95% CI 0.01–0.34). The clinic process of setting aside time to discuss patient feedback appeared to be a mechanism by which formal patient engagement strategies resulted in patients having an impact on practice improvement activities (β = 0.35, 95% CI 0.17–0.54 for influence on strategic goals and β = 0.44, 95% CI 0.23–0.65 for influence on policies and programs).

- Conclusion: These findings may provide guidance for primary care practices that wish to engage patients in practice improvement. The relatively simple steps of developing a formal strategy to identify and engage patients and setting aside time in meetings to discuss patient feedback appear to be important prerequisites for success in these activities.

Patient engagement is becoming an increasingly prominent concept within primary care redesign. Called the “next blockbuster drug of the century” and the “holy grail” of health care [1,2], patient engagement has become a key goal for funders such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute [3] and accrediting agencies such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA).

Patient engagement has been defined as patients working in active partnership at various levels across the health care system to improve health and health care [1]. It can be conceptualized as occurring at 3 levels: at the level of direct care (eg, a clinical encounter), at the level of organizational design and governance, and at the level of policy making [1]. For example, engagement at the level of direct care might involve a patient working with her care team to identify a treatment option that matches her values and preferences. At the level of the health care organization, a patient might provide feedback through a survey or serve on a patient advisory council to improve clinic operations. Patients engaged at the level of policy making might share their opinions with their elected representatives or sit on a national committee. Although research has examined engagement at the direct care level, for example, in studies of shared decision making, there is a paucity of research addressing the impact of patient engagement on clinic-level organizational redesign and practice improvement [4,5].

Relatively few studies describe what primary care practice teams are currently doing at the basic level of soliciting and acting on patient input on the way that their care is delivered. A survey of 112 NCQA-certified patient-centered medical home (PCMH) practices found that 78% conducted patient surveys, 63% gathered qualitative input through focus groups or other feedback, 52% provided a suggestion box, and 32% included patients on advisory councils or teams [6]. Fewer than one-third of PCMH-certified practices were engaging patients or families in more intensive roles as ongoing advisors on practice design or practice improvement [6]. Randomized controlled trials have shown that patient involvement in developing informational materials results in more readable and relevant information [7]. Patient and family involvement in identifying organizational priorities within clinical practice settings resulted in greater alignment with the chronic care model and the PCMH when compared with control groups and resulted in greater agreement between patients and health care professionals [4]. Moreover, a number of innovative health care organizations credit their success in transformation to their patient partnerships [8–10].

Within this context, current practices at community health centers (CHCs) are of particular interest. CHCs are not-for-profit organizations that deliver primary and preventive care to more than 22 million people in the United States [11]. A large proportion of their patients are poor and live in medically underserved communities. More than one-third (37.5%) of CHC patients are uninsured and 38.5% are on Medicaid [12]. Perhaps because of their commitment to caring for medically vulnerable populations that have often had difficulty obtaining needed medical services, some CHCs have been on the forefront of patient engagement [8]. In addition, many CHCs are federally qualified health care centers, which are mandated to engage members of their communities within their governing boards [13]. However, relatively little is known about how CHCs are engaging patients as practice improvement partners or the perceived impact of this engagement on CHC strategic goals, policies, and programs. This study explores these factors and examines the organizational characteristics and processes associated with patients having an impact on practice improvement activities.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, web-based survey of primary care clinician and staff leaders at CHCs in July–August 2014 to assess current strategies, attitudes, facilitators, and barriers toward engaging patients in practice improvement efforts. The study protocol was developed jointly by the San Francisco Bay Area Collaborative Research Network (SFBayCRN), the University of California San Francisco Center for Excellence in Primary Care (CEPC), and the Western Clinicians Network (WCN). The protocol was reviewed by the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research and determined to be exempt research (study number 14-13662).

Survey Participants

Participants in the web-based survey were members of the WCN, a peer-led, volunteer, membership-based association of medical leaders of community health centers in California, Arizona, Nevada, and Hawaii. An invitation and link to a web-based survey was sent by email to members working at WCN CHC, who received up to 3 reminders to complete the survey. We allowed one response per CHC surveyed; in cases where more than one CHC leader was a member of WCN, we requested that the person most familiar with patient engagement activities respond to the survey. In the event of multiple respondents from an organization, incomplete responses were dropped and one complete response was randomly selected to represent the organization. Participants in the survey were entered into a drawing for ten $50 gift cards and one iPad.

Conceptual Model

Measures

The primary outcomes of interest were respondents’ perception of patient impact on strategic priorities, policies, and programs. These outcomes were measured by 2 items: “Patient input helps shape strategic goals or priorities” and “Patient feedback has resulted in policy or program changes at our clinic.” Responses were measured on a 5-item Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). Leadership support was measured using a single item that stated, “Our clinic leadership would like to find more ways to involve patients in practice improvement.” Having a formal strategy was measured using a single item that stated, “We have a formal strategy for how we recruit patients to serve in an advisory capacity.” Clinic processes included having dedicated time in meetings to discuss patient input, as measured by the item, “We dedicate time at team meetings to discuss patient feedback and recommendations.”

In addition to the 10 Likert-type items that captured attitudes, beliefs, and practices, we also asked participants to endorse strategies they used to obtain feedback and suggestions from patients (checklist of options including advisory councils, surveys, suggestion box, etc.). In addition, we assessed practice characteristics such as PCMH recognition status (not applying; in process of applying; received recognition), size of practice (< 5; 5–10; > 10 FTE clinicians), and having dedicated funding such as grant support to pay for patient engagement activities (yes; no).

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed in Stata version 13.0 (College Station, TX). Means and frequencies were used to characterize the sample. Stepwise multivariate modeling was used to identify factors associated with patient engagement outcomes. Organizational characteristics (size of the practice, PCMH recognition status, dedicated funding, leadership support, and having a formal strategy) were included as potential independent variables in Step 1 of the model for each of the 2 hypothesized patient engagement outcomes. Because we theorized that it might be a factor associated with the outcomes that was in turn influenced by clinic characteristics, the process of allocating dedicated time in team meetings to discuss and consider actions to take in response to patient feedback was included as a predictor in Step 2 of each model. Survey items that were not answered were treated as missing data (not imputed). We tested for multiple collinearity using variance influence factors.

Results

The most common mechanisms for receiving patient feedback were surveys (94% of respondents; 91/97) and suggestion boxes (57%; 55/97; Table 1). A third of respondents reported soliciting patient feedback on information materials (33%; 32/97), and almost a third involved patients in selecting referral resources (28%; 27/97). As for ongoing participation, 69% (67/97) of respondents reported involving patients on advisory boards or councils, and 36% (35/97) invited patients to take part in quality improvement committees. Other common activities included inviting patients to conferences or workshops (30%; 29/97) and asking patients to lead self-management or support groups (29%; 28/97).

Most respondents (82%; 77/93) agreed or strongly agreed that patient engagement was worth the time it required. About a third (35%; 32/92) reported having a formal strategy for recruiting and engaging patients in an advisory capacity. About half (52%; 49/94) reported setting aside time in team meetings to discuss patient feedback, although fewer (39%; 35/89) reported that their front line staff met regularly with patients to discuss clinic services and programs. Two-thirds of respondents (68%; 64/94) reported that their leadership would like to find more active ways to involve patients in practice improvement. Less than half (44%; 39/89) felt that they were successful at engaging patient advisors who represented the diversity of the population served. When considering downsides of patient engagement, few agreed that revealing the workings of the clinics to patients would expose the clinic to too much risk (8%; 7/89) or that patients would make unrealistic requests if asked their opinions (14%; 12/89).

Discussion

Among the CHCs surveyed, we found that having a formal strategy for recruiting and engaging patients in practice improvement efforts was associated with patient input shaping strategic goals, programs, and policies. Devoting time in staff team meetings to discuss feedback from patients, such as that received through advisory councils or patient surveys, appeared to be the mechanism by which having a formal strategy for engaging patients influenced the outcomes. Leadership support for patient engagement was also associated with patient input in strategic goals. In contrast, anticipated predictors such as PCMH recognition status, the size of a practice, and having dedicated funding for patient engagement were not associated with these outcomes.

This is the first study known to the authors that examines factors associated with patient engagement outcomes such as patient involvement in clinic-level strategies, policies, and programs. The finding that having a formal process for recruiting and engaging patients and devoting time in team meetings to discuss patient input are significantly associated with patient engagement outcomes is encouraging, because it suggests relatively practical and straightforward actions for primary care leaders interested in engaging patients productively in practice improvement.

The level of patient engagement reported by these respondents is higher than that reported by some other studies. For example, 65% of respondents in this study reported conducting patient surveys and involving patients in ongoing roles as patient advisors, compared to 29% in a 2013 study by Han and colleagues for 112 practices that had received PCMH recognition [6]. This could be partially explained by the fact that many CHCs are federally qualified health centers, which are mandated to have consumer members on their board of directors, and in many cases patient board members may be invited to participate actively in practice improvement. In this study, it is also interesting to note that more than 80% of respondents agreed with the statement that “engaging patients in practice improvement is worth the time and effort it takes,” suggesting that this is a group that valued and prioritized patient engagement.

A lack of time or resources to support patient engagement has been reported as a barrier to effective engagement [15], so it was surprising that having dedicated funding to support patient engagement was not associated with the study outcomes. Only 30% of CHC leaders reported having dedicated funding for patient engagement, while over 80% reported soliciting patient input through longitudinal, bidirectional activities such as committees or advisory councils. While financial support for this vital work is likely important to catalyze and sustain patient engagement at the practice level, it would appear many of the practices surveyed in this study are engaging their patients as partners in practice transformation despite a lack of dedicated resources.

The lack of association that we found between PCMH recognition status and patient influence on strategies, programs, and policies is corroborated by work by Han and colleagues [6], in which they found that the level of PCMH status was not associated with the degree of patient engagement in practice improvement and that only 32% of practices were engaging patients in ongoing roles as advisors.

Devoting time in team meetings to discussing patient feedback seemed to be the mechanism through with having a formal strategy for patient engagement predicted outcomes. Although it may seem self-evident that taking time to discuss patient input could make it more likely to affect clinic practices, we have observed through regular interaction with dozens of health centers that many have comment boxes set up but have no mechanism for systematically reviewing that feedback and considering it as a team. This is also borne out by our survey finding that fewer than 60% of sites that report conducting surveys or having suggestion boxes agree that they set aside time in team meetings to discuss the feedback gleaned from these sources. Thus, the results of this survey suggest that there are simple decisions and structures that may help to turn input from patients into clinic actions.

This study has several limitations. Causation cannot be inferred from this cross-sectional study; additional research is required to understand if helping clinics develop formal strategies for patient recruitment or set aside time in meetings to discuss patient feedback would lead to greater influence of patients on strategic goals, policies, and programs. Data were self-reported by a single person from each CHC, and although members of WCN typically represent clinic leaders who are actively engaged in PCMH-related activities, it is not clear if respondents were aware of the full range of patient engagement strategies used at their clinical site. Front-line clinicians and staff could provide a different perspective on patient engagement. There was no external validation of survey instrument statements regarding the impact of patient input on strategic goals, policies, or programs. The number of respondents (n = 97) is limited, but it is comparable to that in other existing studies [6]. The response rate for this survey was 21%, and respondents may have differed from non-respondents in important ways. When respondents of this study are compared to national samples reporting to the Uniform Data System, the proportion of CHCs with PCMH recognition is lower in our sample (52% versus 65%) [16]. The high level of patient engagement reported by CHC leaders in this study compared to other studies suggests that highly engaged practices may have been more likely to respond than those with lower levels of engagement with their patients. There may have been differences in how patient engagement and advisory roles were interpreted by respondents.

Conclusion

CHC leaders who reported a formal strategy for engaging patients in practice improvement and dedicated time to discuss patient input during team meetings were more likely to report patient input on policies, programs, and strategic goals. Developing a formal strategy to engage patients and establishing protected time on team agendas to discuss patient feedback may be practical ways to promote greater patient engagement in primary care transformation.

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank the leadership of Western Clinicians Network. A special thanks to Dr. Carl Heard, Dr. Mike Witte, Dr. Eric Henley, Dr. Kevin Grumbach, Dr. David Thom, Dr. Quynh Bui, Lucia Angel, and Dr. Thomas Bodenheimer for their feedback on survey and manuscript development. Valuable input on the survey questions were also received from the UCSF Lakeshore Family Medicine Center Patient Advisory Council, the San Francisco General Hospital Patient Advisory Council, and the Malden Family Health Center Patient Advisory Council. Finally, thanks to the community health centers who shared their time and experiences through our survey.

Corresponding author: Rachel Willard-Grace, MPH, Department of Family & Community Medicine, UCSF, 1001 Potrero Hill, Ward 83, Building 80, 3rd Fl, San Francisco, CA 94110, rachel.willard@ucsf.edu.

Funding/support: Internal departmental funding covered the direct costs of conducting this research. This project was also supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000004 which supported Dr. Potter’s time. Dr. Sharma received support from the UCSF primary care research fellowship funded by NRSA grant T32 HP19025. Contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

1. Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:223–31.

2. Dentzer S. Rx for the ‘blockbuster drug’ of patient engagement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:202.

3. Fleurence R, Selby JV, Odom-Walker K, et al. How the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is engaging patients and others in shaping its research agenda. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:393–400.

4. Boivin A, Lehoux P, Lacombe R, et al. Involving patients in setting priorities for healthcare improvement: a cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci 2014;9(24).

5. Peikes D, Genevro J, Scholle SH, Torda P. The patient-centered medical home: strategies to put patients at the center of primary care. AHRQ Publication No. 11-0029. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007.

6. Han E, Hudson Scholle S, Morton S, et al. Survey shows that fewer than a third of patient-centered medical home practices engage patients in quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:368–75.

7. Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johnasen M, et al. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines, and patient information material. Cochrane Database Syst Review 2006;19(3):CD004563.

8. Gottlieb K, Sylvester I, Eby D. Transforming your practice: what matters most. Fam Pract Manage 2008:32–8.

9. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Profiles of change: MCGHealth, 2012. Available at www.ipfcc.org/profiles/prof-mcg.html.

10. Sharma AE, Angel L, Bui Q. Patient advisory councils: giving patients a seat at the table. Fam Pract Manage 2015;22:22–7.

11. National Association of Community Health Centers. Website. Accessed 23 Dec 2014 at www.nachc.com/.

12. Neuhausen K, Grumbach K, Bazemore A, Phillips RL. Integrating community health centers into organized delivery systems can improve access to subspecialty care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1708–16.

13. National Association of Community Health Centers. Health center program governing board workbook. July 2015. Accessed 31 May 2016 at www.aachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Governance-Workbook-8-18.pdf.

14. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psych 1986;51:1173–82.

15. Roseman D, Osborne-Stafsnes J, Helwig AC, et al. Early lessons from four ‘aligning forces for quality’ communities bolster the case for patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:232–41.

16. National Association of Community Health Centers. United States health center fact sheet. 2014. Accessed 27 May 2016 at www.nachc.com/client//US16.pdf.

From the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA (Ms. Willard-Grace, Dr. Sharma, Dr. Potter) and the California Primary Care Association, Sacramento, CA (Ms. Parker).

Abstract

- Objective: To explore how community health centers engage patients in practice improvement and factors associated with patient involvement on clinic-level strategies, policies, and programs.

- Methods: Cross-sectional web-based survey of community health centers in California, Arizona, Nevada, and Hawaii (n = 97).

- Results: The most common mechanisms used by community health centers to obtain patient feedback were surveys (94%; 91/97) and advisory councils (69%; 67/97). Patient-centered medical home recognition and dedicated funding for patient engagement activities were not associated with reported patient influence on the clinic’s strategic goals, policies, or programs. When other factors were controlled for in multivariable modeling, leadership support (β = 0.31, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.10–0.53) and having a formal strategy to identify and engage patients as advisors (β = 0.17, 95% CI 0.02–0.31) were positively associated with patient influence on strategic goals. Having a formal strategy to identify and engage patients also was associated with patient impact on polices and programss (β = 0.17, 95% CI 0.01–0.34). The clinic process of setting aside time to discuss patient feedback appeared to be a mechanism by which formal patient engagement strategies resulted in patients having an impact on practice improvement activities (β = 0.35, 95% CI 0.17–0.54 for influence on strategic goals and β = 0.44, 95% CI 0.23–0.65 for influence on policies and programs).

- Conclusion: These findings may provide guidance for primary care practices that wish to engage patients in practice improvement. The relatively simple steps of developing a formal strategy to identify and engage patients and setting aside time in meetings to discuss patient feedback appear to be important prerequisites for success in these activities.

Patient engagement is becoming an increasingly prominent concept within primary care redesign. Called the “next blockbuster drug of the century” and the “holy grail” of health care [1,2], patient engagement has become a key goal for funders such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute [3] and accrediting agencies such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA).

Patient engagement has been defined as patients working in active partnership at various levels across the health care system to improve health and health care [1]. It can be conceptualized as occurring at 3 levels: at the level of direct care (eg, a clinical encounter), at the level of organizational design and governance, and at the level of policy making [1]. For example, engagement at the level of direct care might involve a patient working with her care team to identify a treatment option that matches her values and preferences. At the level of the health care organization, a patient might provide feedback through a survey or serve on a patient advisory council to improve clinic operations. Patients engaged at the level of policy making might share their opinions with their elected representatives or sit on a national committee. Although research has examined engagement at the direct care level, for example, in studies of shared decision making, there is a paucity of research addressing the impact of patient engagement on clinic-level organizational redesign and practice improvement [4,5].

Relatively few studies describe what primary care practice teams are currently doing at the basic level of soliciting and acting on patient input on the way that their care is delivered. A survey of 112 NCQA-certified patient-centered medical home (PCMH) practices found that 78% conducted patient surveys, 63% gathered qualitative input through focus groups or other feedback, 52% provided a suggestion box, and 32% included patients on advisory councils or teams [6]. Fewer than one-third of PCMH-certified practices were engaging patients or families in more intensive roles as ongoing advisors on practice design or practice improvement [6]. Randomized controlled trials have shown that patient involvement in developing informational materials results in more readable and relevant information [7]. Patient and family involvement in identifying organizational priorities within clinical practice settings resulted in greater alignment with the chronic care model and the PCMH when compared with control groups and resulted in greater agreement between patients and health care professionals [4]. Moreover, a number of innovative health care organizations credit their success in transformation to their patient partnerships [8–10].

Within this context, current practices at community health centers (CHCs) are of particular interest. CHCs are not-for-profit organizations that deliver primary and preventive care to more than 22 million people in the United States [11]. A large proportion of their patients are poor and live in medically underserved communities. More than one-third (37.5%) of CHC patients are uninsured and 38.5% are on Medicaid [12]. Perhaps because of their commitment to caring for medically vulnerable populations that have often had difficulty obtaining needed medical services, some CHCs have been on the forefront of patient engagement [8]. In addition, many CHCs are federally qualified health care centers, which are mandated to engage members of their communities within their governing boards [13]. However, relatively little is known about how CHCs are engaging patients as practice improvement partners or the perceived impact of this engagement on CHC strategic goals, policies, and programs. This study explores these factors and examines the organizational characteristics and processes associated with patients having an impact on practice improvement activities.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, web-based survey of primary care clinician and staff leaders at CHCs in July–August 2014 to assess current strategies, attitudes, facilitators, and barriers toward engaging patients in practice improvement efforts. The study protocol was developed jointly by the San Francisco Bay Area Collaborative Research Network (SFBayCRN), the University of California San Francisco Center for Excellence in Primary Care (CEPC), and the Western Clinicians Network (WCN). The protocol was reviewed by the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research and determined to be exempt research (study number 14-13662).

Survey Participants

Participants in the web-based survey were members of the WCN, a peer-led, volunteer, membership-based association of medical leaders of community health centers in California, Arizona, Nevada, and Hawaii. An invitation and link to a web-based survey was sent by email to members working at WCN CHC, who received up to 3 reminders to complete the survey. We allowed one response per CHC surveyed; in cases where more than one CHC leader was a member of WCN, we requested that the person most familiar with patient engagement activities respond to the survey. In the event of multiple respondents from an organization, incomplete responses were dropped and one complete response was randomly selected to represent the organization. Participants in the survey were entered into a drawing for ten $50 gift cards and one iPad.

Conceptual Model

Measures

The primary outcomes of interest were respondents’ perception of patient impact on strategic priorities, policies, and programs. These outcomes were measured by 2 items: “Patient input helps shape strategic goals or priorities” and “Patient feedback has resulted in policy or program changes at our clinic.” Responses were measured on a 5-item Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). Leadership support was measured using a single item that stated, “Our clinic leadership would like to find more ways to involve patients in practice improvement.” Having a formal strategy was measured using a single item that stated, “We have a formal strategy for how we recruit patients to serve in an advisory capacity.” Clinic processes included having dedicated time in meetings to discuss patient input, as measured by the item, “We dedicate time at team meetings to discuss patient feedback and recommendations.”

In addition to the 10 Likert-type items that captured attitudes, beliefs, and practices, we also asked participants to endorse strategies they used to obtain feedback and suggestions from patients (checklist of options including advisory councils, surveys, suggestion box, etc.). In addition, we assessed practice characteristics such as PCMH recognition status (not applying; in process of applying; received recognition), size of practice (< 5; 5–10; > 10 FTE clinicians), and having dedicated funding such as grant support to pay for patient engagement activities (yes; no).

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed in Stata version 13.0 (College Station, TX). Means and frequencies were used to characterize the sample. Stepwise multivariate modeling was used to identify factors associated with patient engagement outcomes. Organizational characteristics (size of the practice, PCMH recognition status, dedicated funding, leadership support, and having a formal strategy) were included as potential independent variables in Step 1 of the model for each of the 2 hypothesized patient engagement outcomes. Because we theorized that it might be a factor associated with the outcomes that was in turn influenced by clinic characteristics, the process of allocating dedicated time in team meetings to discuss and consider actions to take in response to patient feedback was included as a predictor in Step 2 of each model. Survey items that were not answered were treated as missing data (not imputed). We tested for multiple collinearity using variance influence factors.

Results

The most common mechanisms for receiving patient feedback were surveys (94% of respondents; 91/97) and suggestion boxes (57%; 55/97; Table 1). A third of respondents reported soliciting patient feedback on information materials (33%; 32/97), and almost a third involved patients in selecting referral resources (28%; 27/97). As for ongoing participation, 69% (67/97) of respondents reported involving patients on advisory boards or councils, and 36% (35/97) invited patients to take part in quality improvement committees. Other common activities included inviting patients to conferences or workshops (30%; 29/97) and asking patients to lead self-management or support groups (29%; 28/97).

Most respondents (82%; 77/93) agreed or strongly agreed that patient engagement was worth the time it required. About a third (35%; 32/92) reported having a formal strategy for recruiting and engaging patients in an advisory capacity. About half (52%; 49/94) reported setting aside time in team meetings to discuss patient feedback, although fewer (39%; 35/89) reported that their front line staff met regularly with patients to discuss clinic services and programs. Two-thirds of respondents (68%; 64/94) reported that their leadership would like to find more active ways to involve patients in practice improvement. Less than half (44%; 39/89) felt that they were successful at engaging patient advisors who represented the diversity of the population served. When considering downsides of patient engagement, few agreed that revealing the workings of the clinics to patients would expose the clinic to too much risk (8%; 7/89) or that patients would make unrealistic requests if asked their opinions (14%; 12/89).

Discussion

Among the CHCs surveyed, we found that having a formal strategy for recruiting and engaging patients in practice improvement efforts was associated with patient input shaping strategic goals, programs, and policies. Devoting time in staff team meetings to discuss feedback from patients, such as that received through advisory councils or patient surveys, appeared to be the mechanism by which having a formal strategy for engaging patients influenced the outcomes. Leadership support for patient engagement was also associated with patient input in strategic goals. In contrast, anticipated predictors such as PCMH recognition status, the size of a practice, and having dedicated funding for patient engagement were not associated with these outcomes.

This is the first study known to the authors that examines factors associated with patient engagement outcomes such as patient involvement in clinic-level strategies, policies, and programs. The finding that having a formal process for recruiting and engaging patients and devoting time in team meetings to discuss patient input are significantly associated with patient engagement outcomes is encouraging, because it suggests relatively practical and straightforward actions for primary care leaders interested in engaging patients productively in practice improvement.

The level of patient engagement reported by these respondents is higher than that reported by some other studies. For example, 65% of respondents in this study reported conducting patient surveys and involving patients in ongoing roles as patient advisors, compared to 29% in a 2013 study by Han and colleagues for 112 practices that had received PCMH recognition [6]. This could be partially explained by the fact that many CHCs are federally qualified health centers, which are mandated to have consumer members on their board of directors, and in many cases patient board members may be invited to participate actively in practice improvement. In this study, it is also interesting to note that more than 80% of respondents agreed with the statement that “engaging patients in practice improvement is worth the time and effort it takes,” suggesting that this is a group that valued and prioritized patient engagement.

A lack of time or resources to support patient engagement has been reported as a barrier to effective engagement [15], so it was surprising that having dedicated funding to support patient engagement was not associated with the study outcomes. Only 30% of CHC leaders reported having dedicated funding for patient engagement, while over 80% reported soliciting patient input through longitudinal, bidirectional activities such as committees or advisory councils. While financial support for this vital work is likely important to catalyze and sustain patient engagement at the practice level, it would appear many of the practices surveyed in this study are engaging their patients as partners in practice transformation despite a lack of dedicated resources.

The lack of association that we found between PCMH recognition status and patient influence on strategies, programs, and policies is corroborated by work by Han and colleagues [6], in which they found that the level of PCMH status was not associated with the degree of patient engagement in practice improvement and that only 32% of practices were engaging patients in ongoing roles as advisors.

Devoting time in team meetings to discussing patient feedback seemed to be the mechanism through with having a formal strategy for patient engagement predicted outcomes. Although it may seem self-evident that taking time to discuss patient input could make it more likely to affect clinic practices, we have observed through regular interaction with dozens of health centers that many have comment boxes set up but have no mechanism for systematically reviewing that feedback and considering it as a team. This is also borne out by our survey finding that fewer than 60% of sites that report conducting surveys or having suggestion boxes agree that they set aside time in team meetings to discuss the feedback gleaned from these sources. Thus, the results of this survey suggest that there are simple decisions and structures that may help to turn input from patients into clinic actions.

This study has several limitations. Causation cannot be inferred from this cross-sectional study; additional research is required to understand if helping clinics develop formal strategies for patient recruitment or set aside time in meetings to discuss patient feedback would lead to greater influence of patients on strategic goals, policies, and programs. Data were self-reported by a single person from each CHC, and although members of WCN typically represent clinic leaders who are actively engaged in PCMH-related activities, it is not clear if respondents were aware of the full range of patient engagement strategies used at their clinical site. Front-line clinicians and staff could provide a different perspective on patient engagement. There was no external validation of survey instrument statements regarding the impact of patient input on strategic goals, policies, or programs. The number of respondents (n = 97) is limited, but it is comparable to that in other existing studies [6]. The response rate for this survey was 21%, and respondents may have differed from non-respondents in important ways. When respondents of this study are compared to national samples reporting to the Uniform Data System, the proportion of CHCs with PCMH recognition is lower in our sample (52% versus 65%) [16]. The high level of patient engagement reported by CHC leaders in this study compared to other studies suggests that highly engaged practices may have been more likely to respond than those with lower levels of engagement with their patients. There may have been differences in how patient engagement and advisory roles were interpreted by respondents.

Conclusion

CHC leaders who reported a formal strategy for engaging patients in practice improvement and dedicated time to discuss patient input during team meetings were more likely to report patient input on policies, programs, and strategic goals. Developing a formal strategy to engage patients and establishing protected time on team agendas to discuss patient feedback may be practical ways to promote greater patient engagement in primary care transformation.

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank the leadership of Western Clinicians Network. A special thanks to Dr. Carl Heard, Dr. Mike Witte, Dr. Eric Henley, Dr. Kevin Grumbach, Dr. David Thom, Dr. Quynh Bui, Lucia Angel, and Dr. Thomas Bodenheimer for their feedback on survey and manuscript development. Valuable input on the survey questions were also received from the UCSF Lakeshore Family Medicine Center Patient Advisory Council, the San Francisco General Hospital Patient Advisory Council, and the Malden Family Health Center Patient Advisory Council. Finally, thanks to the community health centers who shared their time and experiences through our survey.

Corresponding author: Rachel Willard-Grace, MPH, Department of Family & Community Medicine, UCSF, 1001 Potrero Hill, Ward 83, Building 80, 3rd Fl, San Francisco, CA 94110, rachel.willard@ucsf.edu.

Funding/support: Internal departmental funding covered the direct costs of conducting this research. This project was also supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000004 which supported Dr. Potter’s time. Dr. Sharma received support from the UCSF primary care research fellowship funded by NRSA grant T32 HP19025. Contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

From the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA (Ms. Willard-Grace, Dr. Sharma, Dr. Potter) and the California Primary Care Association, Sacramento, CA (Ms. Parker).

Abstract

- Objective: To explore how community health centers engage patients in practice improvement and factors associated with patient involvement on clinic-level strategies, policies, and programs.

- Methods: Cross-sectional web-based survey of community health centers in California, Arizona, Nevada, and Hawaii (n = 97).

- Results: The most common mechanisms used by community health centers to obtain patient feedback were surveys (94%; 91/97) and advisory councils (69%; 67/97). Patient-centered medical home recognition and dedicated funding for patient engagement activities were not associated with reported patient influence on the clinic’s strategic goals, policies, or programs. When other factors were controlled for in multivariable modeling, leadership support (β = 0.31, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.10–0.53) and having a formal strategy to identify and engage patients as advisors (β = 0.17, 95% CI 0.02–0.31) were positively associated with patient influence on strategic goals. Having a formal strategy to identify and engage patients also was associated with patient impact on polices and programss (β = 0.17, 95% CI 0.01–0.34). The clinic process of setting aside time to discuss patient feedback appeared to be a mechanism by which formal patient engagement strategies resulted in patients having an impact on practice improvement activities (β = 0.35, 95% CI 0.17–0.54 for influence on strategic goals and β = 0.44, 95% CI 0.23–0.65 for influence on policies and programs).

- Conclusion: These findings may provide guidance for primary care practices that wish to engage patients in practice improvement. The relatively simple steps of developing a formal strategy to identify and engage patients and setting aside time in meetings to discuss patient feedback appear to be important prerequisites for success in these activities.

Patient engagement is becoming an increasingly prominent concept within primary care redesign. Called the “next blockbuster drug of the century” and the “holy grail” of health care [1,2], patient engagement has become a key goal for funders such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute [3] and accrediting agencies such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA).

Patient engagement has been defined as patients working in active partnership at various levels across the health care system to improve health and health care [1]. It can be conceptualized as occurring at 3 levels: at the level of direct care (eg, a clinical encounter), at the level of organizational design and governance, and at the level of policy making [1]. For example, engagement at the level of direct care might involve a patient working with her care team to identify a treatment option that matches her values and preferences. At the level of the health care organization, a patient might provide feedback through a survey or serve on a patient advisory council to improve clinic operations. Patients engaged at the level of policy making might share their opinions with their elected representatives or sit on a national committee. Although research has examined engagement at the direct care level, for example, in studies of shared decision making, there is a paucity of research addressing the impact of patient engagement on clinic-level organizational redesign and practice improvement [4,5].

Relatively few studies describe what primary care practice teams are currently doing at the basic level of soliciting and acting on patient input on the way that their care is delivered. A survey of 112 NCQA-certified patient-centered medical home (PCMH) practices found that 78% conducted patient surveys, 63% gathered qualitative input through focus groups or other feedback, 52% provided a suggestion box, and 32% included patients on advisory councils or teams [6]. Fewer than one-third of PCMH-certified practices were engaging patients or families in more intensive roles as ongoing advisors on practice design or practice improvement [6]. Randomized controlled trials have shown that patient involvement in developing informational materials results in more readable and relevant information [7]. Patient and family involvement in identifying organizational priorities within clinical practice settings resulted in greater alignment with the chronic care model and the PCMH when compared with control groups and resulted in greater agreement between patients and health care professionals [4]. Moreover, a number of innovative health care organizations credit their success in transformation to their patient partnerships [8–10].

Within this context, current practices at community health centers (CHCs) are of particular interest. CHCs are not-for-profit organizations that deliver primary and preventive care to more than 22 million people in the United States [11]. A large proportion of their patients are poor and live in medically underserved communities. More than one-third (37.5%) of CHC patients are uninsured and 38.5% are on Medicaid [12]. Perhaps because of their commitment to caring for medically vulnerable populations that have often had difficulty obtaining needed medical services, some CHCs have been on the forefront of patient engagement [8]. In addition, many CHCs are federally qualified health care centers, which are mandated to engage members of their communities within their governing boards [13]. However, relatively little is known about how CHCs are engaging patients as practice improvement partners or the perceived impact of this engagement on CHC strategic goals, policies, and programs. This study explores these factors and examines the organizational characteristics and processes associated with patients having an impact on practice improvement activities.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, web-based survey of primary care clinician and staff leaders at CHCs in July–August 2014 to assess current strategies, attitudes, facilitators, and barriers toward engaging patients in practice improvement efforts. The study protocol was developed jointly by the San Francisco Bay Area Collaborative Research Network (SFBayCRN), the University of California San Francisco Center for Excellence in Primary Care (CEPC), and the Western Clinicians Network (WCN). The protocol was reviewed by the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research and determined to be exempt research (study number 14-13662).

Survey Participants

Participants in the web-based survey were members of the WCN, a peer-led, volunteer, membership-based association of medical leaders of community health centers in California, Arizona, Nevada, and Hawaii. An invitation and link to a web-based survey was sent by email to members working at WCN CHC, who received up to 3 reminders to complete the survey. We allowed one response per CHC surveyed; in cases where more than one CHC leader was a member of WCN, we requested that the person most familiar with patient engagement activities respond to the survey. In the event of multiple respondents from an organization, incomplete responses were dropped and one complete response was randomly selected to represent the organization. Participants in the survey were entered into a drawing for ten $50 gift cards and one iPad.

Conceptual Model

Measures

The primary outcomes of interest were respondents’ perception of patient impact on strategic priorities, policies, and programs. These outcomes were measured by 2 items: “Patient input helps shape strategic goals or priorities” and “Patient feedback has resulted in policy or program changes at our clinic.” Responses were measured on a 5-item Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). Leadership support was measured using a single item that stated, “Our clinic leadership would like to find more ways to involve patients in practice improvement.” Having a formal strategy was measured using a single item that stated, “We have a formal strategy for how we recruit patients to serve in an advisory capacity.” Clinic processes included having dedicated time in meetings to discuss patient input, as measured by the item, “We dedicate time at team meetings to discuss patient feedback and recommendations.”

In addition to the 10 Likert-type items that captured attitudes, beliefs, and practices, we also asked participants to endorse strategies they used to obtain feedback and suggestions from patients (checklist of options including advisory councils, surveys, suggestion box, etc.). In addition, we assessed practice characteristics such as PCMH recognition status (not applying; in process of applying; received recognition), size of practice (< 5; 5–10; > 10 FTE clinicians), and having dedicated funding such as grant support to pay for patient engagement activities (yes; no).

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed in Stata version 13.0 (College Station, TX). Means and frequencies were used to characterize the sample. Stepwise multivariate modeling was used to identify factors associated with patient engagement outcomes. Organizational characteristics (size of the practice, PCMH recognition status, dedicated funding, leadership support, and having a formal strategy) were included as potential independent variables in Step 1 of the model for each of the 2 hypothesized patient engagement outcomes. Because we theorized that it might be a factor associated with the outcomes that was in turn influenced by clinic characteristics, the process of allocating dedicated time in team meetings to discuss and consider actions to take in response to patient feedback was included as a predictor in Step 2 of each model. Survey items that were not answered were treated as missing data (not imputed). We tested for multiple collinearity using variance influence factors.

Results

The most common mechanisms for receiving patient feedback were surveys (94% of respondents; 91/97) and suggestion boxes (57%; 55/97; Table 1). A third of respondents reported soliciting patient feedback on information materials (33%; 32/97), and almost a third involved patients in selecting referral resources (28%; 27/97). As for ongoing participation, 69% (67/97) of respondents reported involving patients on advisory boards or councils, and 36% (35/97) invited patients to take part in quality improvement committees. Other common activities included inviting patients to conferences or workshops (30%; 29/97) and asking patients to lead self-management or support groups (29%; 28/97).

Most respondents (82%; 77/93) agreed or strongly agreed that patient engagement was worth the time it required. About a third (35%; 32/92) reported having a formal strategy for recruiting and engaging patients in an advisory capacity. About half (52%; 49/94) reported setting aside time in team meetings to discuss patient feedback, although fewer (39%; 35/89) reported that their front line staff met regularly with patients to discuss clinic services and programs. Two-thirds of respondents (68%; 64/94) reported that their leadership would like to find more active ways to involve patients in practice improvement. Less than half (44%; 39/89) felt that they were successful at engaging patient advisors who represented the diversity of the population served. When considering downsides of patient engagement, few agreed that revealing the workings of the clinics to patients would expose the clinic to too much risk (8%; 7/89) or that patients would make unrealistic requests if asked their opinions (14%; 12/89).

Discussion

Among the CHCs surveyed, we found that having a formal strategy for recruiting and engaging patients in practice improvement efforts was associated with patient input shaping strategic goals, programs, and policies. Devoting time in staff team meetings to discuss feedback from patients, such as that received through advisory councils or patient surveys, appeared to be the mechanism by which having a formal strategy for engaging patients influenced the outcomes. Leadership support for patient engagement was also associated with patient input in strategic goals. In contrast, anticipated predictors such as PCMH recognition status, the size of a practice, and having dedicated funding for patient engagement were not associated with these outcomes.

This is the first study known to the authors that examines factors associated with patient engagement outcomes such as patient involvement in clinic-level strategies, policies, and programs. The finding that having a formal process for recruiting and engaging patients and devoting time in team meetings to discuss patient input are significantly associated with patient engagement outcomes is encouraging, because it suggests relatively practical and straightforward actions for primary care leaders interested in engaging patients productively in practice improvement.

The level of patient engagement reported by these respondents is higher than that reported by some other studies. For example, 65% of respondents in this study reported conducting patient surveys and involving patients in ongoing roles as patient advisors, compared to 29% in a 2013 study by Han and colleagues for 112 practices that had received PCMH recognition [6]. This could be partially explained by the fact that many CHCs are federally qualified health centers, which are mandated to have consumer members on their board of directors, and in many cases patient board members may be invited to participate actively in practice improvement. In this study, it is also interesting to note that more than 80% of respondents agreed with the statement that “engaging patients in practice improvement is worth the time and effort it takes,” suggesting that this is a group that valued and prioritized patient engagement.

A lack of time or resources to support patient engagement has been reported as a barrier to effective engagement [15], so it was surprising that having dedicated funding to support patient engagement was not associated with the study outcomes. Only 30% of CHC leaders reported having dedicated funding for patient engagement, while over 80% reported soliciting patient input through longitudinal, bidirectional activities such as committees or advisory councils. While financial support for this vital work is likely important to catalyze and sustain patient engagement at the practice level, it would appear many of the practices surveyed in this study are engaging their patients as partners in practice transformation despite a lack of dedicated resources.

The lack of association that we found between PCMH recognition status and patient influence on strategies, programs, and policies is corroborated by work by Han and colleagues [6], in which they found that the level of PCMH status was not associated with the degree of patient engagement in practice improvement and that only 32% of practices were engaging patients in ongoing roles as advisors.

Devoting time in team meetings to discussing patient feedback seemed to be the mechanism through with having a formal strategy for patient engagement predicted outcomes. Although it may seem self-evident that taking time to discuss patient input could make it more likely to affect clinic practices, we have observed through regular interaction with dozens of health centers that many have comment boxes set up but have no mechanism for systematically reviewing that feedback and considering it as a team. This is also borne out by our survey finding that fewer than 60% of sites that report conducting surveys or having suggestion boxes agree that they set aside time in team meetings to discuss the feedback gleaned from these sources. Thus, the results of this survey suggest that there are simple decisions and structures that may help to turn input from patients into clinic actions.

This study has several limitations. Causation cannot be inferred from this cross-sectional study; additional research is required to understand if helping clinics develop formal strategies for patient recruitment or set aside time in meetings to discuss patient feedback would lead to greater influence of patients on strategic goals, policies, and programs. Data were self-reported by a single person from each CHC, and although members of WCN typically represent clinic leaders who are actively engaged in PCMH-related activities, it is not clear if respondents were aware of the full range of patient engagement strategies used at their clinical site. Front-line clinicians and staff could provide a different perspective on patient engagement. There was no external validation of survey instrument statements regarding the impact of patient input on strategic goals, policies, or programs. The number of respondents (n = 97) is limited, but it is comparable to that in other existing studies [6]. The response rate for this survey was 21%, and respondents may have differed from non-respondents in important ways. When respondents of this study are compared to national samples reporting to the Uniform Data System, the proportion of CHCs with PCMH recognition is lower in our sample (52% versus 65%) [16]. The high level of patient engagement reported by CHC leaders in this study compared to other studies suggests that highly engaged practices may have been more likely to respond than those with lower levels of engagement with their patients. There may have been differences in how patient engagement and advisory roles were interpreted by respondents.

Conclusion

CHC leaders who reported a formal strategy for engaging patients in practice improvement and dedicated time to discuss patient input during team meetings were more likely to report patient input on policies, programs, and strategic goals. Developing a formal strategy to engage patients and establishing protected time on team agendas to discuss patient feedback may be practical ways to promote greater patient engagement in primary care transformation.

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank the leadership of Western Clinicians Network. A special thanks to Dr. Carl Heard, Dr. Mike Witte, Dr. Eric Henley, Dr. Kevin Grumbach, Dr. David Thom, Dr. Quynh Bui, Lucia Angel, and Dr. Thomas Bodenheimer for their feedback on survey and manuscript development. Valuable input on the survey questions were also received from the UCSF Lakeshore Family Medicine Center Patient Advisory Council, the San Francisco General Hospital Patient Advisory Council, and the Malden Family Health Center Patient Advisory Council. Finally, thanks to the community health centers who shared their time and experiences through our survey.

Corresponding author: Rachel Willard-Grace, MPH, Department of Family & Community Medicine, UCSF, 1001 Potrero Hill, Ward 83, Building 80, 3rd Fl, San Francisco, CA 94110, rachel.willard@ucsf.edu.

Funding/support: Internal departmental funding covered the direct costs of conducting this research. This project was also supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000004 which supported Dr. Potter’s time. Dr. Sharma received support from the UCSF primary care research fellowship funded by NRSA grant T32 HP19025. Contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

1. Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:223–31.

2. Dentzer S. Rx for the ‘blockbuster drug’ of patient engagement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:202.

3. Fleurence R, Selby JV, Odom-Walker K, et al. How the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is engaging patients and others in shaping its research agenda. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:393–400.

4. Boivin A, Lehoux P, Lacombe R, et al. Involving patients in setting priorities for healthcare improvement: a cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci 2014;9(24).

5. Peikes D, Genevro J, Scholle SH, Torda P. The patient-centered medical home: strategies to put patients at the center of primary care. AHRQ Publication No. 11-0029. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007.

6. Han E, Hudson Scholle S, Morton S, et al. Survey shows that fewer than a third of patient-centered medical home practices engage patients in quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:368–75.

7. Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johnasen M, et al. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines, and patient information material. Cochrane Database Syst Review 2006;19(3):CD004563.

8. Gottlieb K, Sylvester I, Eby D. Transforming your practice: what matters most. Fam Pract Manage 2008:32–8.

9. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Profiles of change: MCGHealth, 2012. Available at www.ipfcc.org/profiles/prof-mcg.html.

10. Sharma AE, Angel L, Bui Q. Patient advisory councils: giving patients a seat at the table. Fam Pract Manage 2015;22:22–7.

11. National Association of Community Health Centers. Website. Accessed 23 Dec 2014 at www.nachc.com/.

12. Neuhausen K, Grumbach K, Bazemore A, Phillips RL. Integrating community health centers into organized delivery systems can improve access to subspecialty care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1708–16.

13. National Association of Community Health Centers. Health center program governing board workbook. July 2015. Accessed 31 May 2016 at www.aachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Governance-Workbook-8-18.pdf.

14. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psych 1986;51:1173–82.

15. Roseman D, Osborne-Stafsnes J, Helwig AC, et al. Early lessons from four ‘aligning forces for quality’ communities bolster the case for patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:232–41.

16. National Association of Community Health Centers. United States health center fact sheet. 2014. Accessed 27 May 2016 at www.nachc.com/client//US16.pdf.

1. Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:223–31.

2. Dentzer S. Rx for the ‘blockbuster drug’ of patient engagement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:202.

3. Fleurence R, Selby JV, Odom-Walker K, et al. How the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is engaging patients and others in shaping its research agenda. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:393–400.

4. Boivin A, Lehoux P, Lacombe R, et al. Involving patients in setting priorities for healthcare improvement: a cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci 2014;9(24).

5. Peikes D, Genevro J, Scholle SH, Torda P. The patient-centered medical home: strategies to put patients at the center of primary care. AHRQ Publication No. 11-0029. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007.

6. Han E, Hudson Scholle S, Morton S, et al. Survey shows that fewer than a third of patient-centered medical home practices engage patients in quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:368–75.

7. Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johnasen M, et al. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines, and patient information material. Cochrane Database Syst Review 2006;19(3):CD004563.

8. Gottlieb K, Sylvester I, Eby D. Transforming your practice: what matters most. Fam Pract Manage 2008:32–8.

9. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Profiles of change: MCGHealth, 2012. Available at www.ipfcc.org/profiles/prof-mcg.html.

10. Sharma AE, Angel L, Bui Q. Patient advisory councils: giving patients a seat at the table. Fam Pract Manage 2015;22:22–7.

11. National Association of Community Health Centers. Website. Accessed 23 Dec 2014 at www.nachc.com/.

12. Neuhausen K, Grumbach K, Bazemore A, Phillips RL. Integrating community health centers into organized delivery systems can improve access to subspecialty care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1708–16.

13. National Association of Community Health Centers. Health center program governing board workbook. July 2015. Accessed 31 May 2016 at www.aachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Governance-Workbook-8-18.pdf.

14. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psych 1986;51:1173–82.

15. Roseman D, Osborne-Stafsnes J, Helwig AC, et al. Early lessons from four ‘aligning forces for quality’ communities bolster the case for patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:232–41.

16. National Association of Community Health Centers. United States health center fact sheet. 2014. Accessed 27 May 2016 at www.nachc.com/client//US16.pdf.