User login

Female genital cutting (FGC), also known as female circumcision or female genital mutilation, is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.”1 It is a culturally determined practice that is mainly concentrated in certain parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia and now is observed worldwide among migrants from those areas.1 Approximately 200 million women and girls alive today have undergone FGC in 31 countries, although encouragingly the practice’s prevalence seems to be declining, especially among younger women.2

Too often, FGC goes unrecognized in women who present for medical care, even in cases where a genitourinary exam is performed and documented.3,4 As a result, patients face delays in diagnosis and management of associated complications and symptoms. Female genital cutting is usually excluded from medical school or residency training curricula,5 and physicians often lack familiarity with the necessary clinical or surgical management of patients who have had the procedure.6 It is crucial, however, that ObGyns feel comfortable recognizing FGC and clinically caring for pregnant and nonpregnant patients who have undergone the procedure. The obstetric-gynecologic setting should be the clinical space in which FGC is correctly diagnosed and from where patients with complications can be referred for appropriate care.

FGC: Through the lens of inequity

Providing culturally competent and sensitive care to women who have undergone FGC is paramount to reducing health care inequities for these patients. Beyond the medical recommendations we review below, we suggest the following considerations when approaching care for these patients.

Acknowledge our biases. It is paramount for us, as providers, to acknowledge our own biases and how these might affect our relationship with the patient and how our care is received. This starts with our language and terminology: The term female genital mutilation can be judgmental or offensive to our patients, many of whom do not consider themselves to have been mutilated. This is why we prefer to use the term female genital cutting, or whichever word the patient uses, so as not to alienate a patient who might already face many other barriers and microaggressions in seeking health care.

Control our responses. Another way we must check our bias is by controlling our reactions during history taking or examining patients who have undergone FGC. Understandably, providers might be shocked to hear patients recount their childhood experiences of FGC or by examining an infibulated scar, but patients report noticing and experiencing hurt, distress, and shame when providers display judgment, horror, or disgust.7 Patients have reported that they are acutely aware that they might be viewed as “backward” and “primitive” in US health care settings.8 These kinds of feelings and experiences can further exacerbate patients’ distrust and avoidance of the health care system altogether. Therefore, providers should acknowledge their own biases regarding the issue as well as those of their staff and work to mitigate them.

Avoid stigmatization. While FGC can have long-term effects (discussed below), it is important to remember that many women who have undergone FGC do not experience symptoms that are bothersome or feel that FGC is central to their lives or lived experiences. While we must be thorough in our history taking to explore possible urinary, gynecologic, and sexual symptoms of concern and bother to the patient, we must avoid stigmatizing our patients by assuming that all who have undergone FGC are “sexually disabled,” which may lead a provider to recommend medically unindicated intervention, such as clitoral reconstruction.9

Continue to: Classifying FGC types...

Classifying FGC types

The WHO has classified FGC into 4 different types1:

- type 1, partial or total removal of the clitoris or prepuce

- type 2, partial or total removal of part of the clitoris and labia minora

- type 3 (also known as infibulation), the narrowing of the vaginal orifice by cutting, removing, and/or repositioning the labia, and

- type 4, all other procedures to the female genitalia for nonmedical reasons.

Long-term complications

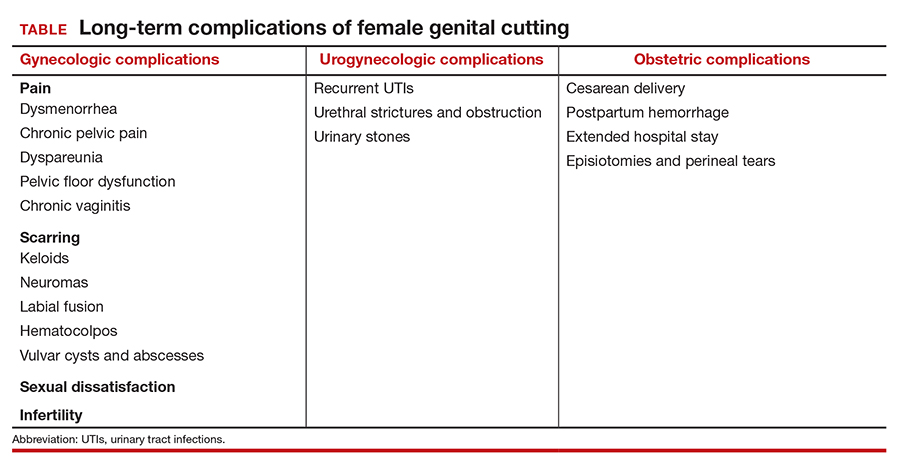

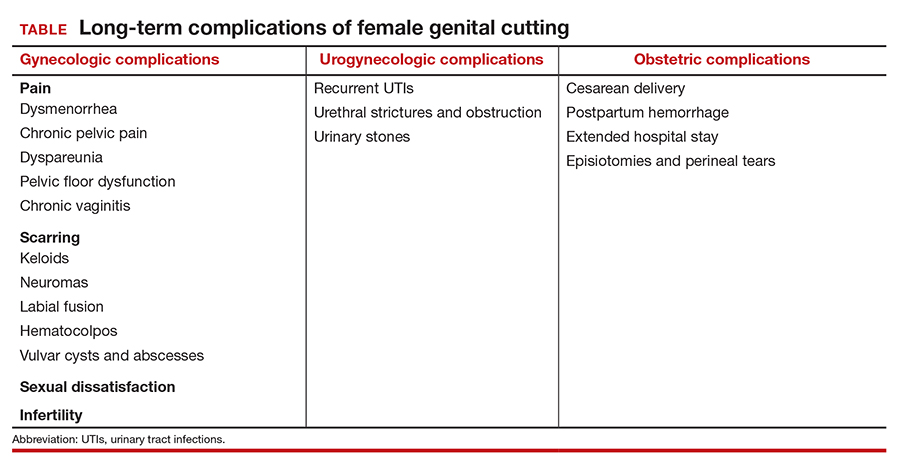

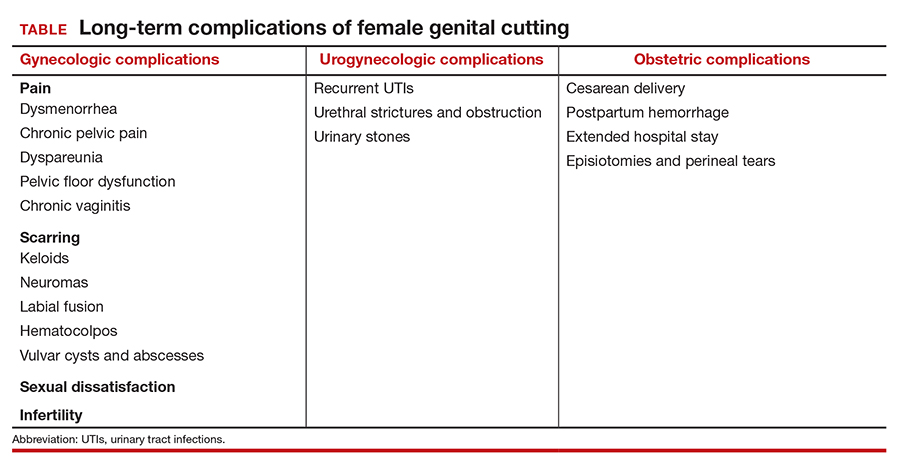

Female genital cutting, especially types 2 and 3, can lead to long-term obstetric and gynecologic complications that the ObGyn should be able to diagnose and manage (TABLE).

The most common long-term complications of FGC are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, recurrent vaginal and urinary tract infections, and sexual dysfunction/dissatisfaction.10 One recent cross-sectional study that used validated questionnaires on pelvic floor and psychosexual symptoms found that women with FGC had higher distress scores than women who had not undergone FGC, indicating various pelvic floor symptoms responsible for impact on their daily lives.11

Infertility can result from a combination of physical barriers (vaginal stenosis and an infibulated scar) and psychologic barriers secondary to dyspareunia, for example.12 Labor and delivery also presents a challenge to both patients and providers, especially in cases of infibulation. Studies show that patients who have undergone FGC are at increased risk of adverse obstetric outcomes, including postpartum hemorrhage, episiotomy, cesarean delivery, and extended hospital stay.13 Neonatal complications, including infant resuscitation and perinatal death, are more commonly reported in studies outside the United States.13

Clinical management recommendations

It is important to be aware of the WHO FCG classifications and be able to recognize evidence of the procedure on examination. The ObGyn should perform a detailed physical exam of the external genitalia as well as a pelvic floor exam of every patient. If the patient does not disclose a history of FGC but it is suspected based on the examination, the clinician should inquire sensitively if the patient is aware of having undergone any genital procedures.

Especially when a history of FGC has been confirmed, clinicians should ask patients sensitively about their urinary and sexual function and satisfaction. Validated tools, such as the Female Sexual Function Index, the Female Sexual Distress Scale, and the Pelvic Floor Disability Index, may be helpful in gathering an objective and detailed assessment of the patient’s symptoms and level of distress.14 Clinicians also should ask about the patient’s detailed obstetric history, particularly regarding the second stage, delivery, and postpartum complications. The clinician also should specifically inquire about a history of defibulation or additional genital procedures.

Patients with urethral strictures or stenosis may require an exam under anesthesia, cystoscopy, urethral dilation, or urethroplasty.12 Those with chronic urinary tract or vaginal infections may require chronic oral suppressive therapy or defibulation (described below). Defibulation also may be considered for relief of severe dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia that may be resulting from hematocolpos. The ObGyn also should make certain to evaluate for other common causes of these symptoms that may be unrelated to FGC, such as endometriosis.

Many women who have undergone FGC do not report dyspareunia or sexual dissatisfaction; however, infibulation especially has been associated with higher rates of these sequelae.12 In addition to defibulation, pelvic floor physical therapy with an experienced therapist may be helpful for patients with pelvic floor dysfunction, vaginismus, and/or dyspareunia.

The defibulation procedure

Defibulation (or deinfibulation) is a surgical reconstructive procedure that opens the infibulated scar of patients who have undergone type 3 FGC (infibulation), thus exposing the urethra and introitus, and in almost half of cases an intact clitoris.15 Defibulation may be specifically requested by a patient or it may be recommended by the ObGyn either for reducing complications of pregnancy or to address the patient’s gynecologic, sexual, or urogynecologic symptoms by allowing penetrative intercourse, urinary flow, physiologic delivery, and menstruation.16

Defibulation should be performed under regional or general anesthesia and can be performed during pregnancy (or even in labor). An anterior incision is made on the infibulated scar, creating a new labia major, and the edges are sutured separately. Postoperatively, patients should be instructed to perform sitz baths and to expect a change in their urinary voiding stream.12 The few studies that have evaluated defibulation have shown high rates of success in addressing preoperative symptoms; the complication rates of defibulation are low and the satisfaction rates are high.16

The ethical conundrum of reinfibulation

Reinfibulation is defined as the restitching or reapproximation of scar tissue or the labia after delivery or a gynecologic procedure, and it is often performed routinely after every delivery in patients’ countries of origin.17

Postpartum reinfibulation on patient request raises legal and ethical issues for the ObGyn. In the United Kingdom, reinfibulation is illegal, and some international organizations, including the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics and the WHO, have recommended against the practice. In the United States, reinfibulation of an adult is legal, as it falls under the umbrella of elective female genital cosmetic surgery.18,19

The procedure could create or exacerbate long-term complications and should generally be discouraged. However, if despite extensive counseling (preferably in the prenatal period) a patient insists on having the procedure, the ObGyn may need to elevate the principle of patient autonomy and either comply or find a practitioner who is comfortable performing it. One retrospective review in Switzerland suggested that specific care and informative counseling prenatally with the inclusion of a patient’s partner in the discussion can improve the acceptability of defibulation without reinfibulation.20

Conclusion

It is important for ObGyns to be familiar with the practice of FGC and to be trained in its recognition on examination and care for the long-term complications that can result from the practice. At the same time, ObGyns should be especially conscious of their biases in order to provide culturally competent care and reduce health care stigmatization and inequities for these patients.

- World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation. February 3, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- UNICEF. Female genital mutilation (FGM). February 2020. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/female-genital-mutilation/. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- Stoklosa H, Nour NM. The eye cannot see what the mind does not know: female genital mutilation. Emerg Med J. 2018;35:585-586. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2018-207994.

- Abdulcadir J, Dugerdil A, Boulvain M, et al. Missed opportunities for diagnosis of female genital mutilation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;125:256-260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.11.016.

- Jäger F, Schulze S, Hohlfeld P. Female genital mutilation in Switzerland: a survey among gynaecologists. Swiss Med Wkly. 2002;132:259-264.

- Zaidi N, Khalil A, Roberts C, et al. Knowledge of female genital mutilation among healthcare professionals. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27:161-164. doi: 10.1080/01443610601124257.

- Chalmers B, Hashi KO. 432 Somali women’s birth experiences in Canada after earlier female genital mutilation. Birth. 2000;27:227-234. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00227.x.

- Shahawy S, Amanuel H, Nour NM. Perspectives on female genital cutting among immigrant women and men in Boston. Soc Sci Med. 2019;220:331-339. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.11.030.

- Sharif Mohamed F, Wild V, Earp BD, et al. Clitoral reconstruction after female genital mutilation/cutting: a review of surgical techniques and ethical debate. J Sex Med. 2020;17:531-542. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.12.004.

- Nour NM. Female genital cutting: a persisting practice. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Summer;1(3):135-139.

- Binkova A, Uebelhart M, Dällenbach P, et al. A cross-sectional study on pelvic floor symptoms in women living with female genital mutilation/cutting. Reprod Health. 2021;18:39. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01097-9.

- Nour NM. Female genital cutting: clinical and cultural guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:272-279. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000118939.19371.af.

- WHO Study Group on Female Genital Mutilation and Obstetric Outcome; Banks E, Meirik O, Farley T, et al. Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet. 2006;367:1835-1841. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 119: female sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:996-1007. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821921ce.

- Nour NM, Michels KB, Bryant AE. Defibulation to treat female genital cutting: effect on symptoms and sexual function. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:55-60. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000224613.72892.77.

- Johnson C, Nour NM. Surgical techniques: defibulation of type III female genital cutting. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1544-1547. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00616.x.

- Serour GI. The issue of reinfibulation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;109:93-96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.01.001.

- Shahawy S, Deshpande NA, Nour NM. Cross-cultural obstetric and gynecologic care of Muslim patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:969-973. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001112.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Elective female genital cosmetic surgery: ACOG committee opinion summary, number 795. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:249-250. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003617.

- Abdulcadir J, McLaren S, Boulvain M, et al. Health education and clinical care of immigrant women with female genital mutilation/cutting who request postpartum reinfibulation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;135:69-72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.03.027.

Female genital cutting (FGC), also known as female circumcision or female genital mutilation, is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.”1 It is a culturally determined practice that is mainly concentrated in certain parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia and now is observed worldwide among migrants from those areas.1 Approximately 200 million women and girls alive today have undergone FGC in 31 countries, although encouragingly the practice’s prevalence seems to be declining, especially among younger women.2

Too often, FGC goes unrecognized in women who present for medical care, even in cases where a genitourinary exam is performed and documented.3,4 As a result, patients face delays in diagnosis and management of associated complications and symptoms. Female genital cutting is usually excluded from medical school or residency training curricula,5 and physicians often lack familiarity with the necessary clinical or surgical management of patients who have had the procedure.6 It is crucial, however, that ObGyns feel comfortable recognizing FGC and clinically caring for pregnant and nonpregnant patients who have undergone the procedure. The obstetric-gynecologic setting should be the clinical space in which FGC is correctly diagnosed and from where patients with complications can be referred for appropriate care.

FGC: Through the lens of inequity

Providing culturally competent and sensitive care to women who have undergone FGC is paramount to reducing health care inequities for these patients. Beyond the medical recommendations we review below, we suggest the following considerations when approaching care for these patients.

Acknowledge our biases. It is paramount for us, as providers, to acknowledge our own biases and how these might affect our relationship with the patient and how our care is received. This starts with our language and terminology: The term female genital mutilation can be judgmental or offensive to our patients, many of whom do not consider themselves to have been mutilated. This is why we prefer to use the term female genital cutting, or whichever word the patient uses, so as not to alienate a patient who might already face many other barriers and microaggressions in seeking health care.

Control our responses. Another way we must check our bias is by controlling our reactions during history taking or examining patients who have undergone FGC. Understandably, providers might be shocked to hear patients recount their childhood experiences of FGC or by examining an infibulated scar, but patients report noticing and experiencing hurt, distress, and shame when providers display judgment, horror, or disgust.7 Patients have reported that they are acutely aware that they might be viewed as “backward” and “primitive” in US health care settings.8 These kinds of feelings and experiences can further exacerbate patients’ distrust and avoidance of the health care system altogether. Therefore, providers should acknowledge their own biases regarding the issue as well as those of their staff and work to mitigate them.

Avoid stigmatization. While FGC can have long-term effects (discussed below), it is important to remember that many women who have undergone FGC do not experience symptoms that are bothersome or feel that FGC is central to their lives or lived experiences. While we must be thorough in our history taking to explore possible urinary, gynecologic, and sexual symptoms of concern and bother to the patient, we must avoid stigmatizing our patients by assuming that all who have undergone FGC are “sexually disabled,” which may lead a provider to recommend medically unindicated intervention, such as clitoral reconstruction.9

Continue to: Classifying FGC types...

Classifying FGC types

The WHO has classified FGC into 4 different types1:

- type 1, partial or total removal of the clitoris or prepuce

- type 2, partial or total removal of part of the clitoris and labia minora

- type 3 (also known as infibulation), the narrowing of the vaginal orifice by cutting, removing, and/or repositioning the labia, and

- type 4, all other procedures to the female genitalia for nonmedical reasons.

Long-term complications

Female genital cutting, especially types 2 and 3, can lead to long-term obstetric and gynecologic complications that the ObGyn should be able to diagnose and manage (TABLE).

The most common long-term complications of FGC are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, recurrent vaginal and urinary tract infections, and sexual dysfunction/dissatisfaction.10 One recent cross-sectional study that used validated questionnaires on pelvic floor and psychosexual symptoms found that women with FGC had higher distress scores than women who had not undergone FGC, indicating various pelvic floor symptoms responsible for impact on their daily lives.11

Infertility can result from a combination of physical barriers (vaginal stenosis and an infibulated scar) and psychologic barriers secondary to dyspareunia, for example.12 Labor and delivery also presents a challenge to both patients and providers, especially in cases of infibulation. Studies show that patients who have undergone FGC are at increased risk of adverse obstetric outcomes, including postpartum hemorrhage, episiotomy, cesarean delivery, and extended hospital stay.13 Neonatal complications, including infant resuscitation and perinatal death, are more commonly reported in studies outside the United States.13

Clinical management recommendations

It is important to be aware of the WHO FCG classifications and be able to recognize evidence of the procedure on examination. The ObGyn should perform a detailed physical exam of the external genitalia as well as a pelvic floor exam of every patient. If the patient does not disclose a history of FGC but it is suspected based on the examination, the clinician should inquire sensitively if the patient is aware of having undergone any genital procedures.

Especially when a history of FGC has been confirmed, clinicians should ask patients sensitively about their urinary and sexual function and satisfaction. Validated tools, such as the Female Sexual Function Index, the Female Sexual Distress Scale, and the Pelvic Floor Disability Index, may be helpful in gathering an objective and detailed assessment of the patient’s symptoms and level of distress.14 Clinicians also should ask about the patient’s detailed obstetric history, particularly regarding the second stage, delivery, and postpartum complications. The clinician also should specifically inquire about a history of defibulation or additional genital procedures.

Patients with urethral strictures or stenosis may require an exam under anesthesia, cystoscopy, urethral dilation, or urethroplasty.12 Those with chronic urinary tract or vaginal infections may require chronic oral suppressive therapy or defibulation (described below). Defibulation also may be considered for relief of severe dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia that may be resulting from hematocolpos. The ObGyn also should make certain to evaluate for other common causes of these symptoms that may be unrelated to FGC, such as endometriosis.

Many women who have undergone FGC do not report dyspareunia or sexual dissatisfaction; however, infibulation especially has been associated with higher rates of these sequelae.12 In addition to defibulation, pelvic floor physical therapy with an experienced therapist may be helpful for patients with pelvic floor dysfunction, vaginismus, and/or dyspareunia.

The defibulation procedure

Defibulation (or deinfibulation) is a surgical reconstructive procedure that opens the infibulated scar of patients who have undergone type 3 FGC (infibulation), thus exposing the urethra and introitus, and in almost half of cases an intact clitoris.15 Defibulation may be specifically requested by a patient or it may be recommended by the ObGyn either for reducing complications of pregnancy or to address the patient’s gynecologic, sexual, or urogynecologic symptoms by allowing penetrative intercourse, urinary flow, physiologic delivery, and menstruation.16

Defibulation should be performed under regional or general anesthesia and can be performed during pregnancy (or even in labor). An anterior incision is made on the infibulated scar, creating a new labia major, and the edges are sutured separately. Postoperatively, patients should be instructed to perform sitz baths and to expect a change in their urinary voiding stream.12 The few studies that have evaluated defibulation have shown high rates of success in addressing preoperative symptoms; the complication rates of defibulation are low and the satisfaction rates are high.16

The ethical conundrum of reinfibulation

Reinfibulation is defined as the restitching or reapproximation of scar tissue or the labia after delivery or a gynecologic procedure, and it is often performed routinely after every delivery in patients’ countries of origin.17

Postpartum reinfibulation on patient request raises legal and ethical issues for the ObGyn. In the United Kingdom, reinfibulation is illegal, and some international organizations, including the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics and the WHO, have recommended against the practice. In the United States, reinfibulation of an adult is legal, as it falls under the umbrella of elective female genital cosmetic surgery.18,19

The procedure could create or exacerbate long-term complications and should generally be discouraged. However, if despite extensive counseling (preferably in the prenatal period) a patient insists on having the procedure, the ObGyn may need to elevate the principle of patient autonomy and either comply or find a practitioner who is comfortable performing it. One retrospective review in Switzerland suggested that specific care and informative counseling prenatally with the inclusion of a patient’s partner in the discussion can improve the acceptability of defibulation without reinfibulation.20

Conclusion

It is important for ObGyns to be familiar with the practice of FGC and to be trained in its recognition on examination and care for the long-term complications that can result from the practice. At the same time, ObGyns should be especially conscious of their biases in order to provide culturally competent care and reduce health care stigmatization and inequities for these patients.

Female genital cutting (FGC), also known as female circumcision or female genital mutilation, is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.”1 It is a culturally determined practice that is mainly concentrated in certain parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia and now is observed worldwide among migrants from those areas.1 Approximately 200 million women and girls alive today have undergone FGC in 31 countries, although encouragingly the practice’s prevalence seems to be declining, especially among younger women.2

Too often, FGC goes unrecognized in women who present for medical care, even in cases where a genitourinary exam is performed and documented.3,4 As a result, patients face delays in diagnosis and management of associated complications and symptoms. Female genital cutting is usually excluded from medical school or residency training curricula,5 and physicians often lack familiarity with the necessary clinical or surgical management of patients who have had the procedure.6 It is crucial, however, that ObGyns feel comfortable recognizing FGC and clinically caring for pregnant and nonpregnant patients who have undergone the procedure. The obstetric-gynecologic setting should be the clinical space in which FGC is correctly diagnosed and from where patients with complications can be referred for appropriate care.

FGC: Through the lens of inequity

Providing culturally competent and sensitive care to women who have undergone FGC is paramount to reducing health care inequities for these patients. Beyond the medical recommendations we review below, we suggest the following considerations when approaching care for these patients.

Acknowledge our biases. It is paramount for us, as providers, to acknowledge our own biases and how these might affect our relationship with the patient and how our care is received. This starts with our language and terminology: The term female genital mutilation can be judgmental or offensive to our patients, many of whom do not consider themselves to have been mutilated. This is why we prefer to use the term female genital cutting, or whichever word the patient uses, so as not to alienate a patient who might already face many other barriers and microaggressions in seeking health care.

Control our responses. Another way we must check our bias is by controlling our reactions during history taking or examining patients who have undergone FGC. Understandably, providers might be shocked to hear patients recount their childhood experiences of FGC or by examining an infibulated scar, but patients report noticing and experiencing hurt, distress, and shame when providers display judgment, horror, or disgust.7 Patients have reported that they are acutely aware that they might be viewed as “backward” and “primitive” in US health care settings.8 These kinds of feelings and experiences can further exacerbate patients’ distrust and avoidance of the health care system altogether. Therefore, providers should acknowledge their own biases regarding the issue as well as those of their staff and work to mitigate them.

Avoid stigmatization. While FGC can have long-term effects (discussed below), it is important to remember that many women who have undergone FGC do not experience symptoms that are bothersome or feel that FGC is central to their lives or lived experiences. While we must be thorough in our history taking to explore possible urinary, gynecologic, and sexual symptoms of concern and bother to the patient, we must avoid stigmatizing our patients by assuming that all who have undergone FGC are “sexually disabled,” which may lead a provider to recommend medically unindicated intervention, such as clitoral reconstruction.9

Continue to: Classifying FGC types...

Classifying FGC types

The WHO has classified FGC into 4 different types1:

- type 1, partial or total removal of the clitoris or prepuce

- type 2, partial or total removal of part of the clitoris and labia minora

- type 3 (also known as infibulation), the narrowing of the vaginal orifice by cutting, removing, and/or repositioning the labia, and

- type 4, all other procedures to the female genitalia for nonmedical reasons.

Long-term complications

Female genital cutting, especially types 2 and 3, can lead to long-term obstetric and gynecologic complications that the ObGyn should be able to diagnose and manage (TABLE).

The most common long-term complications of FGC are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, recurrent vaginal and urinary tract infections, and sexual dysfunction/dissatisfaction.10 One recent cross-sectional study that used validated questionnaires on pelvic floor and psychosexual symptoms found that women with FGC had higher distress scores than women who had not undergone FGC, indicating various pelvic floor symptoms responsible for impact on their daily lives.11

Infertility can result from a combination of physical barriers (vaginal stenosis and an infibulated scar) and psychologic barriers secondary to dyspareunia, for example.12 Labor and delivery also presents a challenge to both patients and providers, especially in cases of infibulation. Studies show that patients who have undergone FGC are at increased risk of adverse obstetric outcomes, including postpartum hemorrhage, episiotomy, cesarean delivery, and extended hospital stay.13 Neonatal complications, including infant resuscitation and perinatal death, are more commonly reported in studies outside the United States.13

Clinical management recommendations

It is important to be aware of the WHO FCG classifications and be able to recognize evidence of the procedure on examination. The ObGyn should perform a detailed physical exam of the external genitalia as well as a pelvic floor exam of every patient. If the patient does not disclose a history of FGC but it is suspected based on the examination, the clinician should inquire sensitively if the patient is aware of having undergone any genital procedures.

Especially when a history of FGC has been confirmed, clinicians should ask patients sensitively about their urinary and sexual function and satisfaction. Validated tools, such as the Female Sexual Function Index, the Female Sexual Distress Scale, and the Pelvic Floor Disability Index, may be helpful in gathering an objective and detailed assessment of the patient’s symptoms and level of distress.14 Clinicians also should ask about the patient’s detailed obstetric history, particularly regarding the second stage, delivery, and postpartum complications. The clinician also should specifically inquire about a history of defibulation or additional genital procedures.

Patients with urethral strictures or stenosis may require an exam under anesthesia, cystoscopy, urethral dilation, or urethroplasty.12 Those with chronic urinary tract or vaginal infections may require chronic oral suppressive therapy or defibulation (described below). Defibulation also may be considered for relief of severe dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia that may be resulting from hematocolpos. The ObGyn also should make certain to evaluate for other common causes of these symptoms that may be unrelated to FGC, such as endometriosis.

Many women who have undergone FGC do not report dyspareunia or sexual dissatisfaction; however, infibulation especially has been associated with higher rates of these sequelae.12 In addition to defibulation, pelvic floor physical therapy with an experienced therapist may be helpful for patients with pelvic floor dysfunction, vaginismus, and/or dyspareunia.

The defibulation procedure

Defibulation (or deinfibulation) is a surgical reconstructive procedure that opens the infibulated scar of patients who have undergone type 3 FGC (infibulation), thus exposing the urethra and introitus, and in almost half of cases an intact clitoris.15 Defibulation may be specifically requested by a patient or it may be recommended by the ObGyn either for reducing complications of pregnancy or to address the patient’s gynecologic, sexual, or urogynecologic symptoms by allowing penetrative intercourse, urinary flow, physiologic delivery, and menstruation.16

Defibulation should be performed under regional or general anesthesia and can be performed during pregnancy (or even in labor). An anterior incision is made on the infibulated scar, creating a new labia major, and the edges are sutured separately. Postoperatively, patients should be instructed to perform sitz baths and to expect a change in their urinary voiding stream.12 The few studies that have evaluated defibulation have shown high rates of success in addressing preoperative symptoms; the complication rates of defibulation are low and the satisfaction rates are high.16

The ethical conundrum of reinfibulation

Reinfibulation is defined as the restitching or reapproximation of scar tissue or the labia after delivery or a gynecologic procedure, and it is often performed routinely after every delivery in patients’ countries of origin.17

Postpartum reinfibulation on patient request raises legal and ethical issues for the ObGyn. In the United Kingdom, reinfibulation is illegal, and some international organizations, including the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics and the WHO, have recommended against the practice. In the United States, reinfibulation of an adult is legal, as it falls under the umbrella of elective female genital cosmetic surgery.18,19

The procedure could create or exacerbate long-term complications and should generally be discouraged. However, if despite extensive counseling (preferably in the prenatal period) a patient insists on having the procedure, the ObGyn may need to elevate the principle of patient autonomy and either comply or find a practitioner who is comfortable performing it. One retrospective review in Switzerland suggested that specific care and informative counseling prenatally with the inclusion of a patient’s partner in the discussion can improve the acceptability of defibulation without reinfibulation.20

Conclusion

It is important for ObGyns to be familiar with the practice of FGC and to be trained in its recognition on examination and care for the long-term complications that can result from the practice. At the same time, ObGyns should be especially conscious of their biases in order to provide culturally competent care and reduce health care stigmatization and inequities for these patients.

- World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation. February 3, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- UNICEF. Female genital mutilation (FGM). February 2020. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/female-genital-mutilation/. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- Stoklosa H, Nour NM. The eye cannot see what the mind does not know: female genital mutilation. Emerg Med J. 2018;35:585-586. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2018-207994.

- Abdulcadir J, Dugerdil A, Boulvain M, et al. Missed opportunities for diagnosis of female genital mutilation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;125:256-260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.11.016.

- Jäger F, Schulze S, Hohlfeld P. Female genital mutilation in Switzerland: a survey among gynaecologists. Swiss Med Wkly. 2002;132:259-264.

- Zaidi N, Khalil A, Roberts C, et al. Knowledge of female genital mutilation among healthcare professionals. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27:161-164. doi: 10.1080/01443610601124257.

- Chalmers B, Hashi KO. 432 Somali women’s birth experiences in Canada after earlier female genital mutilation. Birth. 2000;27:227-234. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00227.x.

- Shahawy S, Amanuel H, Nour NM. Perspectives on female genital cutting among immigrant women and men in Boston. Soc Sci Med. 2019;220:331-339. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.11.030.

- Sharif Mohamed F, Wild V, Earp BD, et al. Clitoral reconstruction after female genital mutilation/cutting: a review of surgical techniques and ethical debate. J Sex Med. 2020;17:531-542. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.12.004.

- Nour NM. Female genital cutting: a persisting practice. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Summer;1(3):135-139.

- Binkova A, Uebelhart M, Dällenbach P, et al. A cross-sectional study on pelvic floor symptoms in women living with female genital mutilation/cutting. Reprod Health. 2021;18:39. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01097-9.

- Nour NM. Female genital cutting: clinical and cultural guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:272-279. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000118939.19371.af.

- WHO Study Group on Female Genital Mutilation and Obstetric Outcome; Banks E, Meirik O, Farley T, et al. Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet. 2006;367:1835-1841. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 119: female sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:996-1007. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821921ce.

- Nour NM, Michels KB, Bryant AE. Defibulation to treat female genital cutting: effect on symptoms and sexual function. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:55-60. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000224613.72892.77.

- Johnson C, Nour NM. Surgical techniques: defibulation of type III female genital cutting. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1544-1547. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00616.x.

- Serour GI. The issue of reinfibulation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;109:93-96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.01.001.

- Shahawy S, Deshpande NA, Nour NM. Cross-cultural obstetric and gynecologic care of Muslim patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:969-973. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001112.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Elective female genital cosmetic surgery: ACOG committee opinion summary, number 795. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:249-250. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003617.

- Abdulcadir J, McLaren S, Boulvain M, et al. Health education and clinical care of immigrant women with female genital mutilation/cutting who request postpartum reinfibulation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;135:69-72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.03.027.

- World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation. February 3, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- UNICEF. Female genital mutilation (FGM). February 2020. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/female-genital-mutilation/. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- Stoklosa H, Nour NM. The eye cannot see what the mind does not know: female genital mutilation. Emerg Med J. 2018;35:585-586. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2018-207994.

- Abdulcadir J, Dugerdil A, Boulvain M, et al. Missed opportunities for diagnosis of female genital mutilation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;125:256-260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.11.016.

- Jäger F, Schulze S, Hohlfeld P. Female genital mutilation in Switzerland: a survey among gynaecologists. Swiss Med Wkly. 2002;132:259-264.

- Zaidi N, Khalil A, Roberts C, et al. Knowledge of female genital mutilation among healthcare professionals. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27:161-164. doi: 10.1080/01443610601124257.

- Chalmers B, Hashi KO. 432 Somali women’s birth experiences in Canada after earlier female genital mutilation. Birth. 2000;27:227-234. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00227.x.

- Shahawy S, Amanuel H, Nour NM. Perspectives on female genital cutting among immigrant women and men in Boston. Soc Sci Med. 2019;220:331-339. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.11.030.

- Sharif Mohamed F, Wild V, Earp BD, et al. Clitoral reconstruction after female genital mutilation/cutting: a review of surgical techniques and ethical debate. J Sex Med. 2020;17:531-542. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.12.004.

- Nour NM. Female genital cutting: a persisting practice. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Summer;1(3):135-139.

- Binkova A, Uebelhart M, Dällenbach P, et al. A cross-sectional study on pelvic floor symptoms in women living with female genital mutilation/cutting. Reprod Health. 2021;18:39. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01097-9.

- Nour NM. Female genital cutting: clinical and cultural guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:272-279. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000118939.19371.af.

- WHO Study Group on Female Genital Mutilation and Obstetric Outcome; Banks E, Meirik O, Farley T, et al. Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet. 2006;367:1835-1841. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 119: female sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:996-1007. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821921ce.

- Nour NM, Michels KB, Bryant AE. Defibulation to treat female genital cutting: effect on symptoms and sexual function. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:55-60. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000224613.72892.77.

- Johnson C, Nour NM. Surgical techniques: defibulation of type III female genital cutting. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1544-1547. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00616.x.

- Serour GI. The issue of reinfibulation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;109:93-96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.01.001.

- Shahawy S, Deshpande NA, Nour NM. Cross-cultural obstetric and gynecologic care of Muslim patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:969-973. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001112.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Elective female genital cosmetic surgery: ACOG committee opinion summary, number 795. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:249-250. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003617.

- Abdulcadir J, McLaren S, Boulvain M, et al. Health education and clinical care of immigrant women with female genital mutilation/cutting who request postpartum reinfibulation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;135:69-72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.03.027.