User login

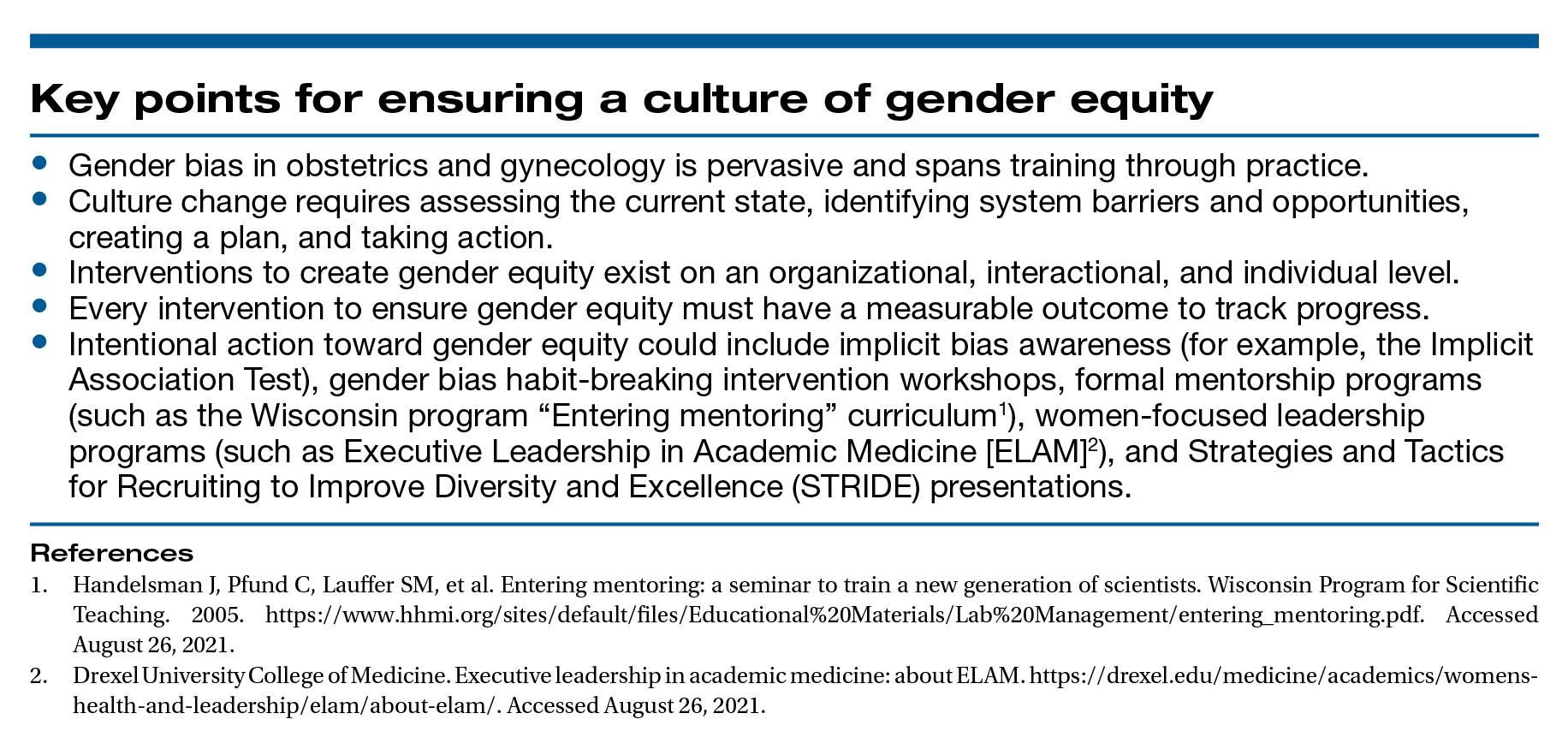

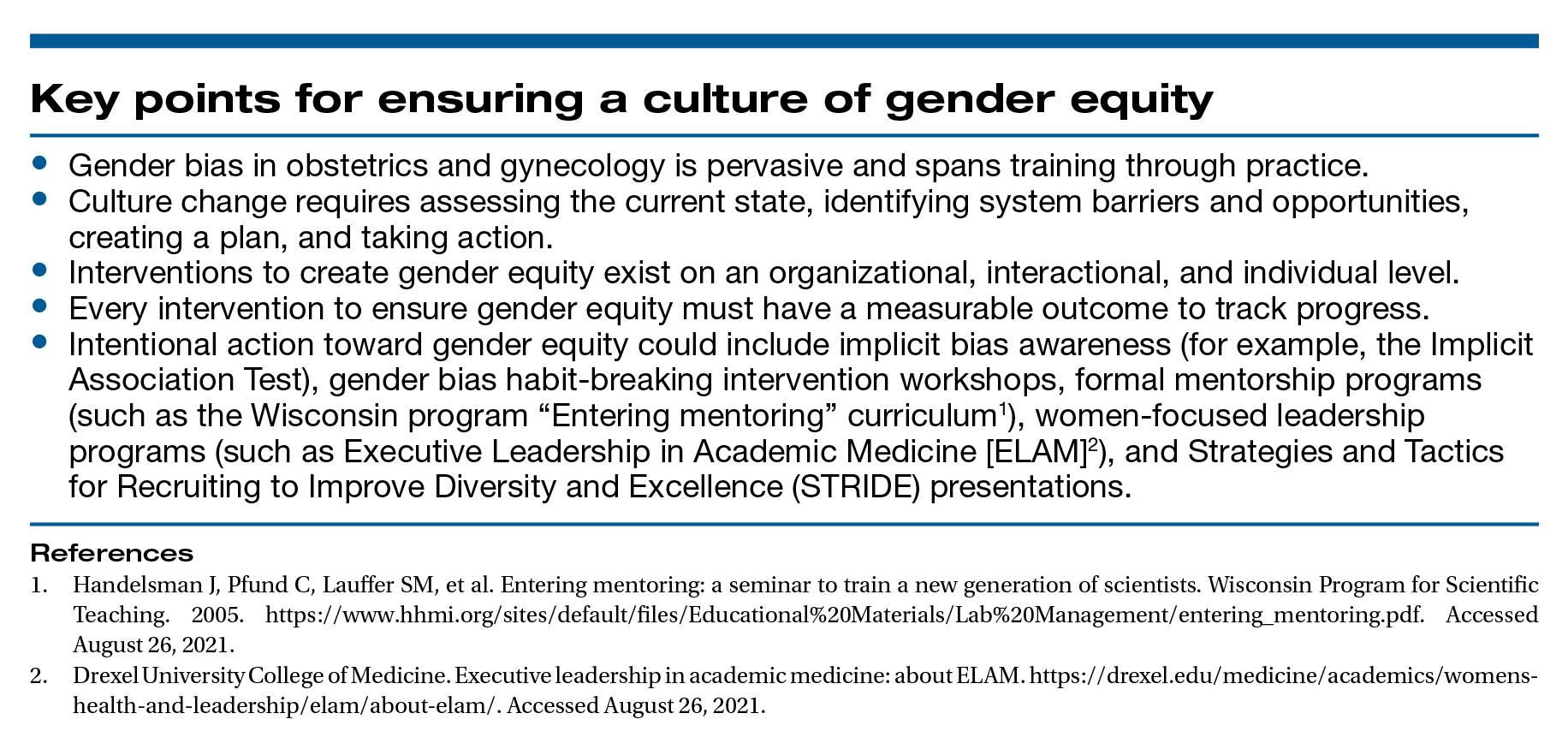

A workplace environment conducive to success includes equal access to resources and opportunities, work-life integration, freedom from gender discrimination and sexual harassment, and supportive leadership. With focused leadership that is accountable for actionable interventions through measurable outcomes, it is possible to create an equitable, safe, and dignified workplace for all ObGyns.

Recently, obstetrics and gynecology has become the only surgical specialty in which a majority of practitioners are women. Since the 1990s, women in ObGyn have composed the majority of trainees, and 2012 marked the first year that more than half of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Fellows in practice were women.1

Despite the large proportion of women within the specialty, ongoing gender-based inequities continue. Many of these inequities are rooted in our pervasive societal views of behavioral norms based on biologic or perceived sex, otherwise known as “gender,” roles.2 The cultural gender role for men embodies characteristics that are bold, competitive, decisive, analytical; qualities for women include modesty, nurturing, and accommodating in interactions with others. Such male-typed traits and behaviors are termed “agentic” because they involve human agency, whereas female-typed traits and behaviors are termed “communal.”3

Gender biases remain widespread, even among health care providers.4 When gender roles are applied to medical specialties, there is an assumption that women tend toward “communal” specialties, such as pediatrics or family practice, whereas men are better suited for technical or procedural specialties.5 ObGyn is an outlier in this schema because its procedural and surgical aspects would characterize the specialty as “agentic,” yet the majority of ObGyn trainees and physicians are women.

Biases related to gender impact many aspects of practice for the ObGyn, including:

- surgical education and training

- the gender wage gap

- interpersonal interactions and sexual harassment

- advancement and promotion.

Surgical education and training

The message that desirable characteristics for leadership and autonomy are aligned with masculinity is enforced early in medical culture, and it supports the ubiquity of deep-seated stereotypes about gender roles in medicine. For example, the language used for letters of recommendation for women applying to residency and fellowship highlight communal language (nurturing, warm), whereas those for men more typically use agentic terms (decisive, strong, future leader).6 During ObGyn surgical training, women residents receive more negative evaluations than men from nurses throughout training, and they report spending more effort to nurture these relationships, including changing communication in order to engage assistance from nurses.7

Similarly, women trainees receive harsher and more contradictory feedback from attending physicians.8 For example, a woman resident may be criticized for failing to develop independence and execute complete plans for patient care; later, she might be labeled as “rogue” and told that she should engage with and seek input from supervising faculty when independently executing a treatment plan.

Even when attempting to apply feedback in the operating room, women trainees are afforded less surgical autonomy than men trainees.9 These factors contribute to lower surgical confidence in women trainees despite their having the same technical skills as men, as measured by the Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery skills exam.10

Continue to: The gender wage gap...

The gender wage gap

The mean salary for women ObGyns remains lower than that for men at every academic rank, with the differences ranging from $54,700 at the assistant professor rank to $183,200 for the department chair position.11 Notably, the pay discrepancy persists after adjustments are made for common salary-influencing metrics, such as experience, practice construct, and academic productivity.12 The gender salary gap is further identified for women subspecialists, as women reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists and gynecologic oncologists earn $67,000 and $120,000 less, respectively, than men colleagues.13,14

While the gender wage gap often is attributed to women’s desire to work part time, similar rates of graduating women and men medical students in 2018 ranked schedule flexibility as important, suggesting that work-life balance is related to an individual’s generation rather than gender.11

Parenting status specifically adversely affects women physicians, with an ascribed “motherhood penalty” and “fatherhood bonus” phenomenon: women physicians who became parents lost an additional 6% salary, whereas men physicians saw a salary increase of 4% with parenthood.15

Most worrisome for the specialty is evidence of declining wages for ObGyns relative to other fields. “Occupational segregation”16 refers to the pronounced negative effect on earnings as more women enter a given field, which has been described in other professions.17 Overall, ObGyn salaries are the lowest among surgical specialties18 and show evidence of decline corresponding to the increasing numbers of women in the field.16

Interpersonal interactions and sexual harassment

In the workplace, women in ObGyn face more interpersonal relationship friction than men. Practicing women ObGyns report differing treatment by nurses as compared to men,19 noting that additional time and effort are required to nurture professional relationships. Additionally, nurses and trainees20 evaluate practicing women ObGyns more harshly than they evaluate men. Further, women gynecologic surgeons experience gender bias from patients, as patients endorse a preference to have a woman gynecologist but prefer a man gynecologic surgeon.21

In addition to gender bias, the experience of gender harassment, including sexual harassment, is common, as two-thirds of women gynecologists report workplace harassment, 90% of which is attributed to gender.22 This rate is 3 times higher than that for men, with a senior colleague in a position of power within the same organization reported to be the harasser to women in 91% of occurrences.

Advancement and promotion

Within academia, women faculty face specific career-limiting barriers related to gender. Rates of academic promotion and leadership opportunities remain lower for women than for men faculty. Although there has been more women representation in ObGyn over the past 20 years, the number of women serving as department chairs, cancer center directors, editors-in-chief, or on a board of directors remains lower than what would be expected by representation ratios.23 (Representation ratios were calculated as the proportion of ObGyn department-based leadership roles held by women in 2019 divided by the proportion of women ObGyn residents in 1990; representation ratios <1.0 indicate underrepresentation of women). This lag in attainment of leadership roles is compounded by the difficulties women faculty experience in finding mentorship and sponsorship,24 which are known benefits to career advancement.

Having fewer women hold leadership roles also negatively influences those in training. For example, a survey of emergency medicine and ObGyn residents identified an implicit gender bias that men and women residents favored men for leadership roles.25 This difference, however, was not significant when division chiefs and department chairs were women, which suggests that visibility of women leaders positively influences the stereotype perception of men and women trainees.4

Continue to: Blueprint for change...

Blueprint for change

While the issues surrounding gender bias are widespread, solutions exist to create gender equity within ObGyn. Efforts to change individual behavior and organizational culture should start with an understanding of the current environment.

Multiple studies have promoted the concept of “culture change,”26,27 which parallels a standard change process. A critical aspect of change is that individuals and organizations maintain the status quo until something prompts a desire to achieve a different way of being. As data regarding the breadth and impact of gender bias emerge and awareness is raised, there is recognition that the status quo is not achieving the goals of the department or institution. This may occur through the result of loss of physician talent, reduced access for vulnerable patient populations, or lower financial productivity.

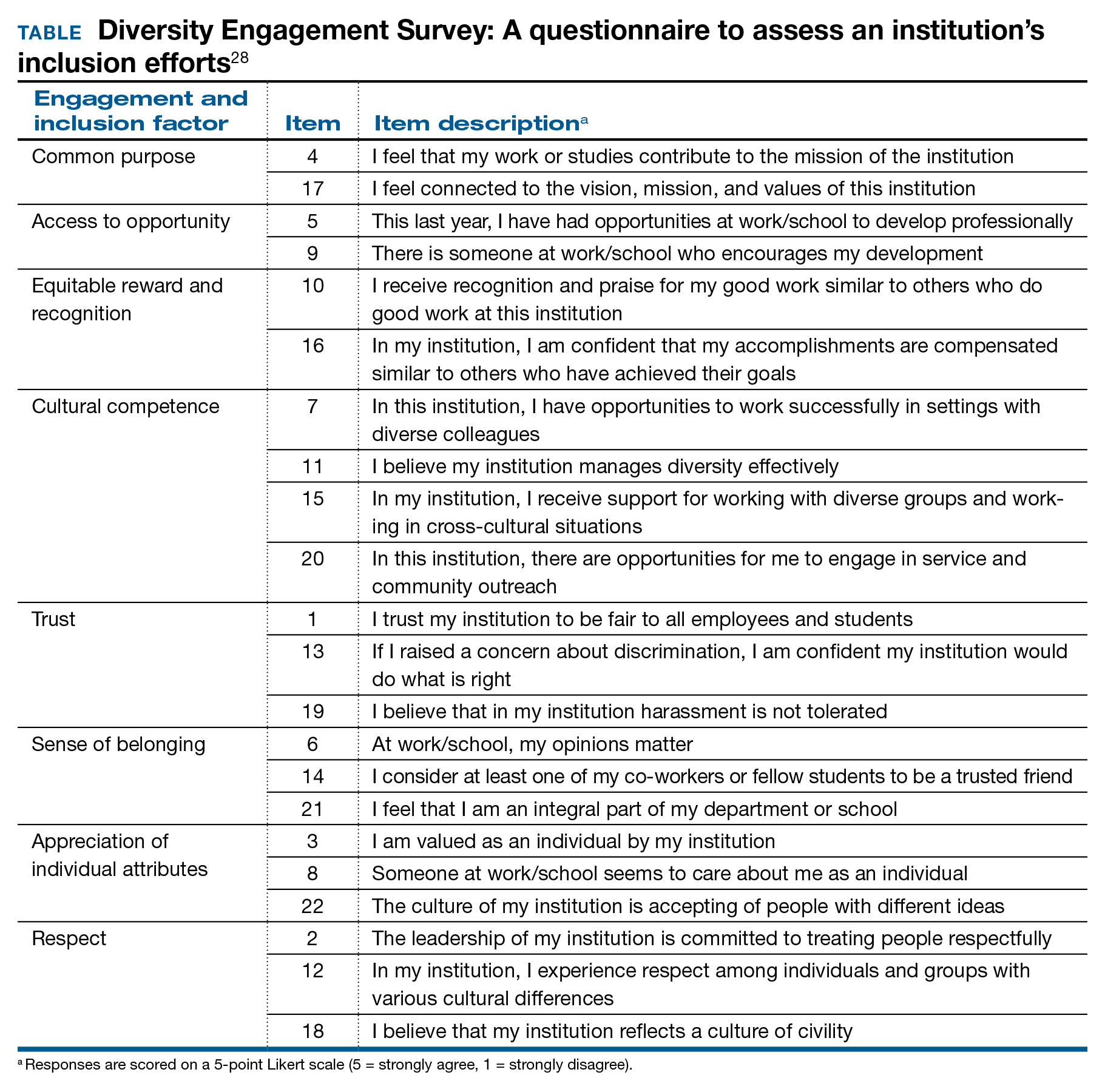

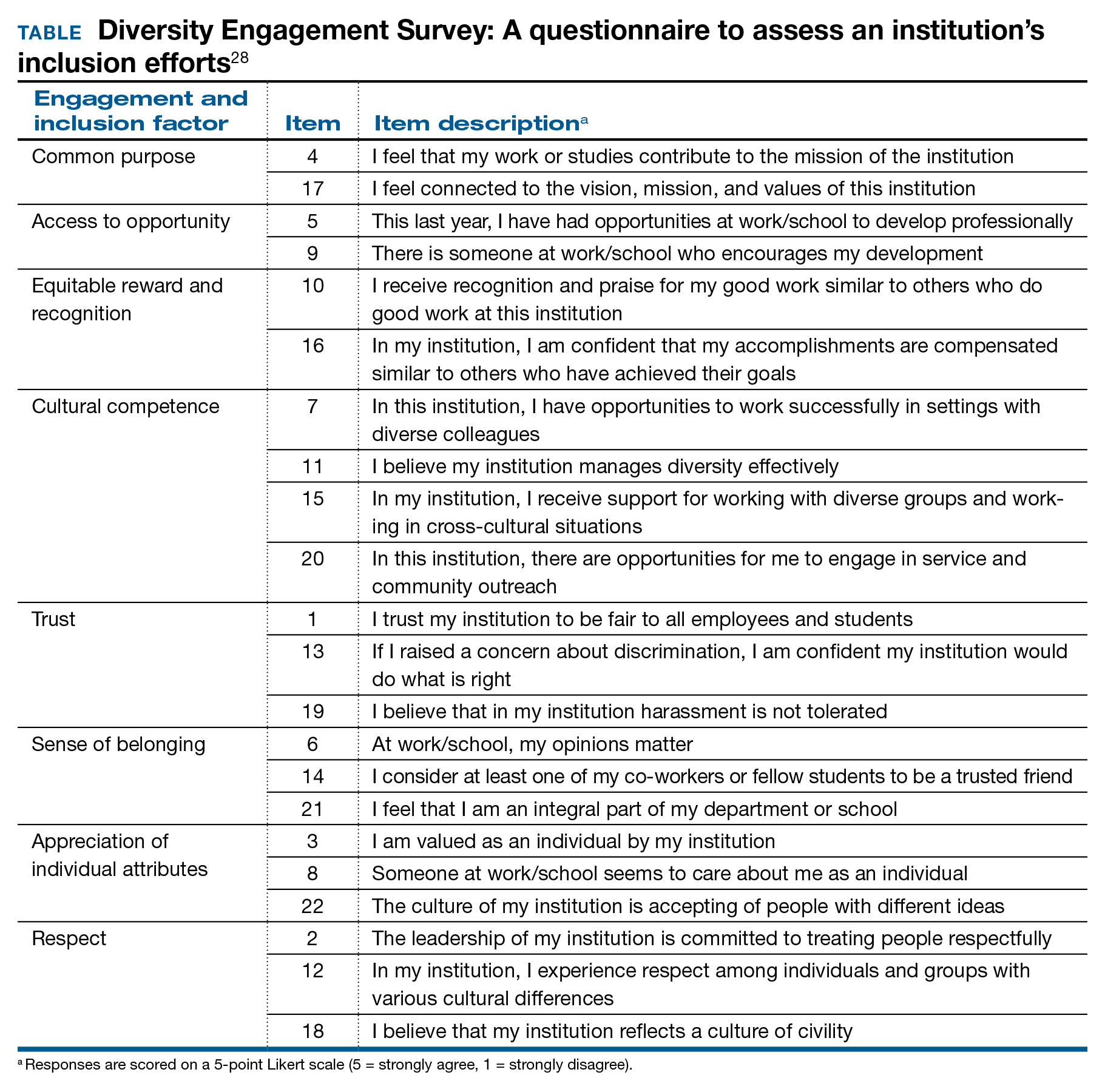

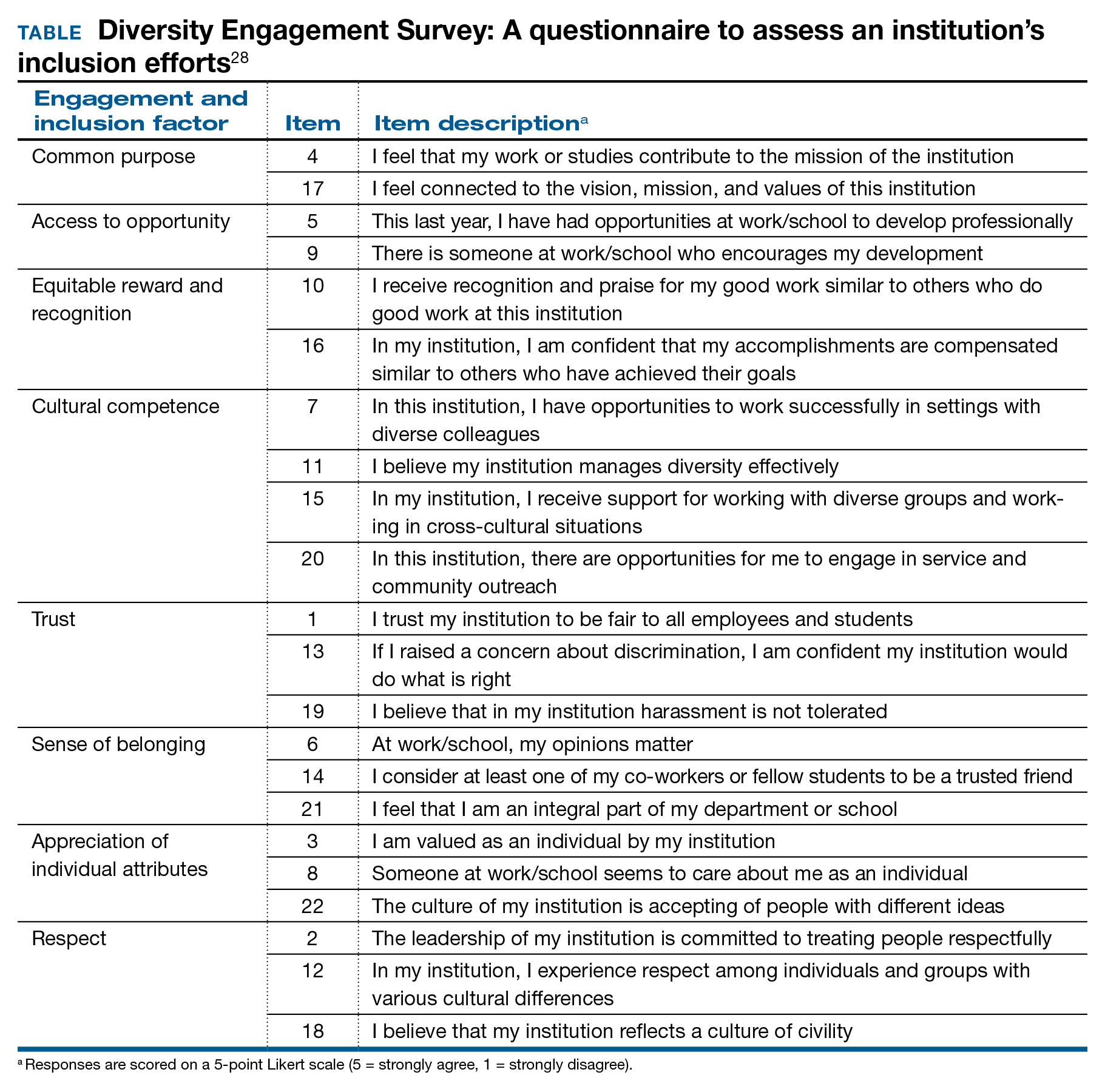

Once change is considered, it must deliberately be pursued through a specific process. The first actionable step is to assess the existing state and then identify prior barriers to and current opportunities for success. A validated instrument that has been applied for this purpose is the Diversity Engagement Survey, a 22-item questionnaire that assesses 8 domains of organizational inclusion on a 5-point Likert scale (see TABLE).28 This tool not only provides a measure of institutional culture but also obtains characteristics of the respondents so that it additionally assesses how engaged specific groups are within the organization. Once baseline data are obtained, an action plan can be formulated and enacted. This cycle of assessment, system influences, plan, and act should be continued until the desired changes are achieved.

It is critically important to identify objective, measurable outcomes to assure that the interventions are moving the culture toward enhanced gender equity. As the ideal state is achieved, development of practices and enforceable policies help to ensure the longevity of cultural changes. Furthermore, periodic re-evaluation of the existing organizational culture will confirm the maintenance of gender equity objectives.

Solutions toward gender equity

Gender inequity may arise from societal gender roles, but it is incumbent on health care organizations to create an environment free from gender bias and gender harassment. An imperative first step is to identify the occurrence of gender discrimination.

The HITS (Hurt, Insulted, Threatened with harm, or Screamed at) screening tool has been used effectively with surgical residents to identify the prevalence of and most common types of abuse.29 This instrument could be adapted and administered to ObGyns in practice or in training. These data should inform the need for system-level antisexist training as well as enforcement of zero-tolerance policies.

Organizations have the ability to create a salary-only compensation model for physicians within the same specialty regardless of academic rank or academic productivity, which has been demonstrated to eliminate gender pay disparity.30 Additional measures to achieve gender equity involve antisexist hiring processes31 and transparency in metrics for job performance, salary, and promotion.32

While health care organizations are obliged to construct a gender-equitable culture, efforts can be made on the individual level. Implicit bias is ascribed to the unconscious attitudes and stereotypes people conclude about groups. The Implicit Association Test (IAT) is a validated instrument that provides the respondent with information about one’s own implicit biases. By uncovering gender bias “blind spots,” an individual can work to consciously overcome these stereotypes. Extending from the mental reframing required for overturning implicit biases, individuals can learn to identify and intervene in real-world situations. This concept of “being an upstander” denotes stepping in and standing up when an inappropriate situation arises33 (see “Case example: Being an upstander”). The targeted individual may not have the ability or safety to navigate through a confrontation, but an upstander might be able to assist the target with empowerment, verbalization of needs, and support.

Lastly, mentorship and sponsorship are critical factors for professional development and career advancement. Bidirectional mentorship identifies benefit for the mentee and the mentor whereby the junior faculty obtain career development and support and the senior faculty may learn new teaching or communication skills.34

A final word

As recognized advocates for women’s health, we must intentionally move toward a workplace that is equitable, safe, and dignified for all ObGyns. Ensuring gender equity within obstetrics and gynecology is everyone’s responsibility. ●

Dr. Bethany Wain is attending a departmental conference and is talking with another member of her division when Dr. Joselle, her division director, approaches. He is accompanied by the Visiting Professor, an internationally reputable and dynamic man, a content expert in the field of work in which Dr. Wain is interested and has published. Dr. Joselle introduces the Visiting Professor formally, using his title of “doctor.” He then introduces Dr. Wain by her abridged first name, Beth.

As an upstander, the Visiting Professor quickly addresses Dr. Wain by her title and uses the situation as a platform to highlight the need to maintain professional address in the professional environment. He then adds that women, who are usually junior in academic rank, confer more benefit to being addressed formally and receiving visibility and respect for their work in a public forum. In this way, the Visiting Professor amplifies Dr. Wain’s work and status and demonstrates the standard of using professional address for women and men.

- Rayburn WF. The Obstetrician-Gynecologist Workforce in the United States: Facts, Figures, and Implications, 2017. Washington, DC: American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

- Carnes M. Commentary: deconstructing gender differences. Acad Med. 2010;85:575-577.

- Eagly AH. The his and hers of prosocial behavior: an examination of the social psychology of gender. Am Psychol. 2009;64:644-658.

- Salles A, Awad M, Goldin L, et al. Estimating implicit and explicit gender bias among health care professionals and surgeons. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e196545.

- Carnes M, Bartels CM, Kaatz A, et al. Why is John more likely to become department chair than Jennifer? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:197-214.

- Hoffman A, Grant, W, McCormick, et al. Gendered differences in letters of recommendation for transplant surgery fellowship applicants. J Surg Edu. 2019;76:427-432.

- Galvin SL, Parlier AB, Martino E, et al. Gender bias in nurse evaluations of residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(suppl 4):7S-12S.

- Gerull KM, Loe M, Seiler K, et al. Assessing gender bias in qualitative evaluations of surgical residents. Am J Surg. 2019;217:306-313.

- Meyerson SL, Sternbach JM, Zwischenberger JB, et al. The effect of gender on resident autonomy in the operating room. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:e111-e118.

- Flyckt RL, White EE, Goodman LR, et al. The use of laparoscopy simulation to explore gender differences in resident surgical confidence. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2017;2017:1945801.

- Heisler CA, Mark K, Ton J, et al. Has a critical mass of women resulted in gender equity in gynecologic surgery? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:665-673.

- Warner AS, Lehmann LS. Gender wage disparities in medicine: time to close the gap. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1334-1336.

- Gilbert SB, Allshouse A, Skaznik-Wikiel ME. Gender inequality in salaries among reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:1194-1200.

- Croft KM, Rauh LA, Orr JW, et al. Compensation differences by gender in gynecologic oncology. Society of Gynecologic Oncology Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. 2020. https://sgo.confex.com /sgo/2020/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/15762. 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Wang SS, Ackerman S. The motherhood penalty: is it alive and well in 2020? J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:688-689.

- Pelley E, Carnes M. When a specialty becomes “women’s work”: trends in and implications of specialty gender segregation in medicine. Acad Med. 2020;95:1499-1506.

- Hegewisch A, Hartmann H. Occupational segregation and the gender wage gap: a job half done. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. 2014. https://iwpr.org/iwpr-issues/employment-and-earnings /occupational-segregation-and-the-gender-wage-gap-a-job-half -done/. Accessed August 26, 2021.

- Greenberg CC. Association for Academic Surgery presidential address: sticky floors and glass ceilings. J Surg Res. 2017;219:ix-xviii.

- Dossett LA, Vitous CA, Lindquist K, et al. Women surgeons’ experiences of interprofessional workplace conflict. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2019843.

- Morgan HK, Purkis JA, Porter AC, et al. Student evaluation of faculty physicians: gender differences in teaching evaluations. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25:453-456.

- Childs AJ, Friedman WH, Schwartz MP, et al. Female patients’ sex preferences in selection of gynecologists and surgeons. South Med J. 2005;98:405-408.

- Brown J, Drury L, Raub K, et al. Workplace harassment and discrimination in gynecology: results of the AAGL Member Survey. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:838-846.

- Temkin AM, Rubinsak L, Benoit MF, et al. Take me to your leader: reporting structures and equity in academic gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;157:759-764.

- Shakil S, Redberg RF. Gender disparities in sponsorship—how they perpetuate the glass ceiling. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:582.

- Hansen M, Schoonover A, Skarica B, et al. Implicit gender bias among US resident physicians. BMC Med Ed. 2019;19:396.

- Estrada M, Burnett M, Campbell AG, et al. Improving underrepresented minority student persistence in STEM. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15:es5.

- Carnes M, Handelsman J, Sheridan J. Diversity in academic medicine: the stages of change model. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2005;14:471-475.

- Person SD, Jordan CG, Allison JJ, et al. Measuring diversity and inclusion in academic medicine. The Diversity Engagement Survey. Acad Med. 2015;90:1675-1683.

- Fitzgerald CA, Smith RN, Luo-Owen X, et al. Screening for harassment, abuse, and discrimination among surgery residents: an EAST multicenter trial. Am Surg. 2019;85:456-461.

- Hayes SN, Noseworthy JH, Farrugia G. A structured compensation plan results in equitable physician compensation: a single-center analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:35-43.

- Devine PG, Forscher PS, Cox WT, et al. A gender bias habit-breaking intervention led to increased hiring of female faculty in STEMM departments. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2017;73:211-215.

- Morgan AU, Chaiyachati KH, Weissman GE, et al. Eliminating genderbased bias in academic medicine: more than naming the “elephant in the room.” J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:966-968.

- Mello MM, Jagsi R. Standing up against gender bias and harassment— a matter of professional ethics. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1385-1387.

- Burgess A, van Diggele C, Mellis C. Mentorship in the health profession: a review. Clin Teach. 2018;15:197-202.

A workplace environment conducive to success includes equal access to resources and opportunities, work-life integration, freedom from gender discrimination and sexual harassment, and supportive leadership. With focused leadership that is accountable for actionable interventions through measurable outcomes, it is possible to create an equitable, safe, and dignified workplace for all ObGyns.

Recently, obstetrics and gynecology has become the only surgical specialty in which a majority of practitioners are women. Since the 1990s, women in ObGyn have composed the majority of trainees, and 2012 marked the first year that more than half of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Fellows in practice were women.1

Despite the large proportion of women within the specialty, ongoing gender-based inequities continue. Many of these inequities are rooted in our pervasive societal views of behavioral norms based on biologic or perceived sex, otherwise known as “gender,” roles.2 The cultural gender role for men embodies characteristics that are bold, competitive, decisive, analytical; qualities for women include modesty, nurturing, and accommodating in interactions with others. Such male-typed traits and behaviors are termed “agentic” because they involve human agency, whereas female-typed traits and behaviors are termed “communal.”3

Gender biases remain widespread, even among health care providers.4 When gender roles are applied to medical specialties, there is an assumption that women tend toward “communal” specialties, such as pediatrics or family practice, whereas men are better suited for technical or procedural specialties.5 ObGyn is an outlier in this schema because its procedural and surgical aspects would characterize the specialty as “agentic,” yet the majority of ObGyn trainees and physicians are women.

Biases related to gender impact many aspects of practice for the ObGyn, including:

- surgical education and training

- the gender wage gap

- interpersonal interactions and sexual harassment

- advancement and promotion.

Surgical education and training

The message that desirable characteristics for leadership and autonomy are aligned with masculinity is enforced early in medical culture, and it supports the ubiquity of deep-seated stereotypes about gender roles in medicine. For example, the language used for letters of recommendation for women applying to residency and fellowship highlight communal language (nurturing, warm), whereas those for men more typically use agentic terms (decisive, strong, future leader).6 During ObGyn surgical training, women residents receive more negative evaluations than men from nurses throughout training, and they report spending more effort to nurture these relationships, including changing communication in order to engage assistance from nurses.7

Similarly, women trainees receive harsher and more contradictory feedback from attending physicians.8 For example, a woman resident may be criticized for failing to develop independence and execute complete plans for patient care; later, she might be labeled as “rogue” and told that she should engage with and seek input from supervising faculty when independently executing a treatment plan.

Even when attempting to apply feedback in the operating room, women trainees are afforded less surgical autonomy than men trainees.9 These factors contribute to lower surgical confidence in women trainees despite their having the same technical skills as men, as measured by the Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery skills exam.10

Continue to: The gender wage gap...

The gender wage gap

The mean salary for women ObGyns remains lower than that for men at every academic rank, with the differences ranging from $54,700 at the assistant professor rank to $183,200 for the department chair position.11 Notably, the pay discrepancy persists after adjustments are made for common salary-influencing metrics, such as experience, practice construct, and academic productivity.12 The gender salary gap is further identified for women subspecialists, as women reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists and gynecologic oncologists earn $67,000 and $120,000 less, respectively, than men colleagues.13,14

While the gender wage gap often is attributed to women’s desire to work part time, similar rates of graduating women and men medical students in 2018 ranked schedule flexibility as important, suggesting that work-life balance is related to an individual’s generation rather than gender.11

Parenting status specifically adversely affects women physicians, with an ascribed “motherhood penalty” and “fatherhood bonus” phenomenon: women physicians who became parents lost an additional 6% salary, whereas men physicians saw a salary increase of 4% with parenthood.15

Most worrisome for the specialty is evidence of declining wages for ObGyns relative to other fields. “Occupational segregation”16 refers to the pronounced negative effect on earnings as more women enter a given field, which has been described in other professions.17 Overall, ObGyn salaries are the lowest among surgical specialties18 and show evidence of decline corresponding to the increasing numbers of women in the field.16

Interpersonal interactions and sexual harassment

In the workplace, women in ObGyn face more interpersonal relationship friction than men. Practicing women ObGyns report differing treatment by nurses as compared to men,19 noting that additional time and effort are required to nurture professional relationships. Additionally, nurses and trainees20 evaluate practicing women ObGyns more harshly than they evaluate men. Further, women gynecologic surgeons experience gender bias from patients, as patients endorse a preference to have a woman gynecologist but prefer a man gynecologic surgeon.21

In addition to gender bias, the experience of gender harassment, including sexual harassment, is common, as two-thirds of women gynecologists report workplace harassment, 90% of which is attributed to gender.22 This rate is 3 times higher than that for men, with a senior colleague in a position of power within the same organization reported to be the harasser to women in 91% of occurrences.

Advancement and promotion

Within academia, women faculty face specific career-limiting barriers related to gender. Rates of academic promotion and leadership opportunities remain lower for women than for men faculty. Although there has been more women representation in ObGyn over the past 20 years, the number of women serving as department chairs, cancer center directors, editors-in-chief, or on a board of directors remains lower than what would be expected by representation ratios.23 (Representation ratios were calculated as the proportion of ObGyn department-based leadership roles held by women in 2019 divided by the proportion of women ObGyn residents in 1990; representation ratios <1.0 indicate underrepresentation of women). This lag in attainment of leadership roles is compounded by the difficulties women faculty experience in finding mentorship and sponsorship,24 which are known benefits to career advancement.

Having fewer women hold leadership roles also negatively influences those in training. For example, a survey of emergency medicine and ObGyn residents identified an implicit gender bias that men and women residents favored men for leadership roles.25 This difference, however, was not significant when division chiefs and department chairs were women, which suggests that visibility of women leaders positively influences the stereotype perception of men and women trainees.4

Continue to: Blueprint for change...

Blueprint for change

While the issues surrounding gender bias are widespread, solutions exist to create gender equity within ObGyn. Efforts to change individual behavior and organizational culture should start with an understanding of the current environment.

Multiple studies have promoted the concept of “culture change,”26,27 which parallels a standard change process. A critical aspect of change is that individuals and organizations maintain the status quo until something prompts a desire to achieve a different way of being. As data regarding the breadth and impact of gender bias emerge and awareness is raised, there is recognition that the status quo is not achieving the goals of the department or institution. This may occur through the result of loss of physician talent, reduced access for vulnerable patient populations, or lower financial productivity.

Once change is considered, it must deliberately be pursued through a specific process. The first actionable step is to assess the existing state and then identify prior barriers to and current opportunities for success. A validated instrument that has been applied for this purpose is the Diversity Engagement Survey, a 22-item questionnaire that assesses 8 domains of organizational inclusion on a 5-point Likert scale (see TABLE).28 This tool not only provides a measure of institutional culture but also obtains characteristics of the respondents so that it additionally assesses how engaged specific groups are within the organization. Once baseline data are obtained, an action plan can be formulated and enacted. This cycle of assessment, system influences, plan, and act should be continued until the desired changes are achieved.

It is critically important to identify objective, measurable outcomes to assure that the interventions are moving the culture toward enhanced gender equity. As the ideal state is achieved, development of practices and enforceable policies help to ensure the longevity of cultural changes. Furthermore, periodic re-evaluation of the existing organizational culture will confirm the maintenance of gender equity objectives.

Solutions toward gender equity

Gender inequity may arise from societal gender roles, but it is incumbent on health care organizations to create an environment free from gender bias and gender harassment. An imperative first step is to identify the occurrence of gender discrimination.

The HITS (Hurt, Insulted, Threatened with harm, or Screamed at) screening tool has been used effectively with surgical residents to identify the prevalence of and most common types of abuse.29 This instrument could be adapted and administered to ObGyns in practice or in training. These data should inform the need for system-level antisexist training as well as enforcement of zero-tolerance policies.

Organizations have the ability to create a salary-only compensation model for physicians within the same specialty regardless of academic rank or academic productivity, which has been demonstrated to eliminate gender pay disparity.30 Additional measures to achieve gender equity involve antisexist hiring processes31 and transparency in metrics for job performance, salary, and promotion.32

While health care organizations are obliged to construct a gender-equitable culture, efforts can be made on the individual level. Implicit bias is ascribed to the unconscious attitudes and stereotypes people conclude about groups. The Implicit Association Test (IAT) is a validated instrument that provides the respondent with information about one’s own implicit biases. By uncovering gender bias “blind spots,” an individual can work to consciously overcome these stereotypes. Extending from the mental reframing required for overturning implicit biases, individuals can learn to identify and intervene in real-world situations. This concept of “being an upstander” denotes stepping in and standing up when an inappropriate situation arises33 (see “Case example: Being an upstander”). The targeted individual may not have the ability or safety to navigate through a confrontation, but an upstander might be able to assist the target with empowerment, verbalization of needs, and support.

Lastly, mentorship and sponsorship are critical factors for professional development and career advancement. Bidirectional mentorship identifies benefit for the mentee and the mentor whereby the junior faculty obtain career development and support and the senior faculty may learn new teaching or communication skills.34

A final word

As recognized advocates for women’s health, we must intentionally move toward a workplace that is equitable, safe, and dignified for all ObGyns. Ensuring gender equity within obstetrics and gynecology is everyone’s responsibility. ●

Dr. Bethany Wain is attending a departmental conference and is talking with another member of her division when Dr. Joselle, her division director, approaches. He is accompanied by the Visiting Professor, an internationally reputable and dynamic man, a content expert in the field of work in which Dr. Wain is interested and has published. Dr. Joselle introduces the Visiting Professor formally, using his title of “doctor.” He then introduces Dr. Wain by her abridged first name, Beth.

As an upstander, the Visiting Professor quickly addresses Dr. Wain by her title and uses the situation as a platform to highlight the need to maintain professional address in the professional environment. He then adds that women, who are usually junior in academic rank, confer more benefit to being addressed formally and receiving visibility and respect for their work in a public forum. In this way, the Visiting Professor amplifies Dr. Wain’s work and status and demonstrates the standard of using professional address for women and men.

A workplace environment conducive to success includes equal access to resources and opportunities, work-life integration, freedom from gender discrimination and sexual harassment, and supportive leadership. With focused leadership that is accountable for actionable interventions through measurable outcomes, it is possible to create an equitable, safe, and dignified workplace for all ObGyns.

Recently, obstetrics and gynecology has become the only surgical specialty in which a majority of practitioners are women. Since the 1990s, women in ObGyn have composed the majority of trainees, and 2012 marked the first year that more than half of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Fellows in practice were women.1

Despite the large proportion of women within the specialty, ongoing gender-based inequities continue. Many of these inequities are rooted in our pervasive societal views of behavioral norms based on biologic or perceived sex, otherwise known as “gender,” roles.2 The cultural gender role for men embodies characteristics that are bold, competitive, decisive, analytical; qualities for women include modesty, nurturing, and accommodating in interactions with others. Such male-typed traits and behaviors are termed “agentic” because they involve human agency, whereas female-typed traits and behaviors are termed “communal.”3

Gender biases remain widespread, even among health care providers.4 When gender roles are applied to medical specialties, there is an assumption that women tend toward “communal” specialties, such as pediatrics or family practice, whereas men are better suited for technical or procedural specialties.5 ObGyn is an outlier in this schema because its procedural and surgical aspects would characterize the specialty as “agentic,” yet the majority of ObGyn trainees and physicians are women.

Biases related to gender impact many aspects of practice for the ObGyn, including:

- surgical education and training

- the gender wage gap

- interpersonal interactions and sexual harassment

- advancement and promotion.

Surgical education and training

The message that desirable characteristics for leadership and autonomy are aligned with masculinity is enforced early in medical culture, and it supports the ubiquity of deep-seated stereotypes about gender roles in medicine. For example, the language used for letters of recommendation for women applying to residency and fellowship highlight communal language (nurturing, warm), whereas those for men more typically use agentic terms (decisive, strong, future leader).6 During ObGyn surgical training, women residents receive more negative evaluations than men from nurses throughout training, and they report spending more effort to nurture these relationships, including changing communication in order to engage assistance from nurses.7

Similarly, women trainees receive harsher and more contradictory feedback from attending physicians.8 For example, a woman resident may be criticized for failing to develop independence and execute complete plans for patient care; later, she might be labeled as “rogue” and told that she should engage with and seek input from supervising faculty when independently executing a treatment plan.

Even when attempting to apply feedback in the operating room, women trainees are afforded less surgical autonomy than men trainees.9 These factors contribute to lower surgical confidence in women trainees despite their having the same technical skills as men, as measured by the Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery skills exam.10

Continue to: The gender wage gap...

The gender wage gap

The mean salary for women ObGyns remains lower than that for men at every academic rank, with the differences ranging from $54,700 at the assistant professor rank to $183,200 for the department chair position.11 Notably, the pay discrepancy persists after adjustments are made for common salary-influencing metrics, such as experience, practice construct, and academic productivity.12 The gender salary gap is further identified for women subspecialists, as women reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists and gynecologic oncologists earn $67,000 and $120,000 less, respectively, than men colleagues.13,14

While the gender wage gap often is attributed to women’s desire to work part time, similar rates of graduating women and men medical students in 2018 ranked schedule flexibility as important, suggesting that work-life balance is related to an individual’s generation rather than gender.11

Parenting status specifically adversely affects women physicians, with an ascribed “motherhood penalty” and “fatherhood bonus” phenomenon: women physicians who became parents lost an additional 6% salary, whereas men physicians saw a salary increase of 4% with parenthood.15

Most worrisome for the specialty is evidence of declining wages for ObGyns relative to other fields. “Occupational segregation”16 refers to the pronounced negative effect on earnings as more women enter a given field, which has been described in other professions.17 Overall, ObGyn salaries are the lowest among surgical specialties18 and show evidence of decline corresponding to the increasing numbers of women in the field.16

Interpersonal interactions and sexual harassment

In the workplace, women in ObGyn face more interpersonal relationship friction than men. Practicing women ObGyns report differing treatment by nurses as compared to men,19 noting that additional time and effort are required to nurture professional relationships. Additionally, nurses and trainees20 evaluate practicing women ObGyns more harshly than they evaluate men. Further, women gynecologic surgeons experience gender bias from patients, as patients endorse a preference to have a woman gynecologist but prefer a man gynecologic surgeon.21

In addition to gender bias, the experience of gender harassment, including sexual harassment, is common, as two-thirds of women gynecologists report workplace harassment, 90% of which is attributed to gender.22 This rate is 3 times higher than that for men, with a senior colleague in a position of power within the same organization reported to be the harasser to women in 91% of occurrences.

Advancement and promotion

Within academia, women faculty face specific career-limiting barriers related to gender. Rates of academic promotion and leadership opportunities remain lower for women than for men faculty. Although there has been more women representation in ObGyn over the past 20 years, the number of women serving as department chairs, cancer center directors, editors-in-chief, or on a board of directors remains lower than what would be expected by representation ratios.23 (Representation ratios were calculated as the proportion of ObGyn department-based leadership roles held by women in 2019 divided by the proportion of women ObGyn residents in 1990; representation ratios <1.0 indicate underrepresentation of women). This lag in attainment of leadership roles is compounded by the difficulties women faculty experience in finding mentorship and sponsorship,24 which are known benefits to career advancement.

Having fewer women hold leadership roles also negatively influences those in training. For example, a survey of emergency medicine and ObGyn residents identified an implicit gender bias that men and women residents favored men for leadership roles.25 This difference, however, was not significant when division chiefs and department chairs were women, which suggests that visibility of women leaders positively influences the stereotype perception of men and women trainees.4

Continue to: Blueprint for change...

Blueprint for change

While the issues surrounding gender bias are widespread, solutions exist to create gender equity within ObGyn. Efforts to change individual behavior and organizational culture should start with an understanding of the current environment.

Multiple studies have promoted the concept of “culture change,”26,27 which parallels a standard change process. A critical aspect of change is that individuals and organizations maintain the status quo until something prompts a desire to achieve a different way of being. As data regarding the breadth and impact of gender bias emerge and awareness is raised, there is recognition that the status quo is not achieving the goals of the department or institution. This may occur through the result of loss of physician talent, reduced access for vulnerable patient populations, or lower financial productivity.

Once change is considered, it must deliberately be pursued through a specific process. The first actionable step is to assess the existing state and then identify prior barriers to and current opportunities for success. A validated instrument that has been applied for this purpose is the Diversity Engagement Survey, a 22-item questionnaire that assesses 8 domains of organizational inclusion on a 5-point Likert scale (see TABLE).28 This tool not only provides a measure of institutional culture but also obtains characteristics of the respondents so that it additionally assesses how engaged specific groups are within the organization. Once baseline data are obtained, an action plan can be formulated and enacted. This cycle of assessment, system influences, plan, and act should be continued until the desired changes are achieved.

It is critically important to identify objective, measurable outcomes to assure that the interventions are moving the culture toward enhanced gender equity. As the ideal state is achieved, development of practices and enforceable policies help to ensure the longevity of cultural changes. Furthermore, periodic re-evaluation of the existing organizational culture will confirm the maintenance of gender equity objectives.

Solutions toward gender equity

Gender inequity may arise from societal gender roles, but it is incumbent on health care organizations to create an environment free from gender bias and gender harassment. An imperative first step is to identify the occurrence of gender discrimination.

The HITS (Hurt, Insulted, Threatened with harm, or Screamed at) screening tool has been used effectively with surgical residents to identify the prevalence of and most common types of abuse.29 This instrument could be adapted and administered to ObGyns in practice or in training. These data should inform the need for system-level antisexist training as well as enforcement of zero-tolerance policies.

Organizations have the ability to create a salary-only compensation model for physicians within the same specialty regardless of academic rank or academic productivity, which has been demonstrated to eliminate gender pay disparity.30 Additional measures to achieve gender equity involve antisexist hiring processes31 and transparency in metrics for job performance, salary, and promotion.32

While health care organizations are obliged to construct a gender-equitable culture, efforts can be made on the individual level. Implicit bias is ascribed to the unconscious attitudes and stereotypes people conclude about groups. The Implicit Association Test (IAT) is a validated instrument that provides the respondent with information about one’s own implicit biases. By uncovering gender bias “blind spots,” an individual can work to consciously overcome these stereotypes. Extending from the mental reframing required for overturning implicit biases, individuals can learn to identify and intervene in real-world situations. This concept of “being an upstander” denotes stepping in and standing up when an inappropriate situation arises33 (see “Case example: Being an upstander”). The targeted individual may not have the ability or safety to navigate through a confrontation, but an upstander might be able to assist the target with empowerment, verbalization of needs, and support.

Lastly, mentorship and sponsorship are critical factors for professional development and career advancement. Bidirectional mentorship identifies benefit for the mentee and the mentor whereby the junior faculty obtain career development and support and the senior faculty may learn new teaching or communication skills.34

A final word

As recognized advocates for women’s health, we must intentionally move toward a workplace that is equitable, safe, and dignified for all ObGyns. Ensuring gender equity within obstetrics and gynecology is everyone’s responsibility. ●

Dr. Bethany Wain is attending a departmental conference and is talking with another member of her division when Dr. Joselle, her division director, approaches. He is accompanied by the Visiting Professor, an internationally reputable and dynamic man, a content expert in the field of work in which Dr. Wain is interested and has published. Dr. Joselle introduces the Visiting Professor formally, using his title of “doctor.” He then introduces Dr. Wain by her abridged first name, Beth.

As an upstander, the Visiting Professor quickly addresses Dr. Wain by her title and uses the situation as a platform to highlight the need to maintain professional address in the professional environment. He then adds that women, who are usually junior in academic rank, confer more benefit to being addressed formally and receiving visibility and respect for their work in a public forum. In this way, the Visiting Professor amplifies Dr. Wain’s work and status and demonstrates the standard of using professional address for women and men.

- Rayburn WF. The Obstetrician-Gynecologist Workforce in the United States: Facts, Figures, and Implications, 2017. Washington, DC: American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

- Carnes M. Commentary: deconstructing gender differences. Acad Med. 2010;85:575-577.

- Eagly AH. The his and hers of prosocial behavior: an examination of the social psychology of gender. Am Psychol. 2009;64:644-658.

- Salles A, Awad M, Goldin L, et al. Estimating implicit and explicit gender bias among health care professionals and surgeons. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e196545.

- Carnes M, Bartels CM, Kaatz A, et al. Why is John more likely to become department chair than Jennifer? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:197-214.

- Hoffman A, Grant, W, McCormick, et al. Gendered differences in letters of recommendation for transplant surgery fellowship applicants. J Surg Edu. 2019;76:427-432.

- Galvin SL, Parlier AB, Martino E, et al. Gender bias in nurse evaluations of residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(suppl 4):7S-12S.

- Gerull KM, Loe M, Seiler K, et al. Assessing gender bias in qualitative evaluations of surgical residents. Am J Surg. 2019;217:306-313.

- Meyerson SL, Sternbach JM, Zwischenberger JB, et al. The effect of gender on resident autonomy in the operating room. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:e111-e118.

- Flyckt RL, White EE, Goodman LR, et al. The use of laparoscopy simulation to explore gender differences in resident surgical confidence. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2017;2017:1945801.

- Heisler CA, Mark K, Ton J, et al. Has a critical mass of women resulted in gender equity in gynecologic surgery? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:665-673.

- Warner AS, Lehmann LS. Gender wage disparities in medicine: time to close the gap. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1334-1336.

- Gilbert SB, Allshouse A, Skaznik-Wikiel ME. Gender inequality in salaries among reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:1194-1200.

- Croft KM, Rauh LA, Orr JW, et al. Compensation differences by gender in gynecologic oncology. Society of Gynecologic Oncology Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. 2020. https://sgo.confex.com /sgo/2020/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/15762. 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Wang SS, Ackerman S. The motherhood penalty: is it alive and well in 2020? J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:688-689.

- Pelley E, Carnes M. When a specialty becomes “women’s work”: trends in and implications of specialty gender segregation in medicine. Acad Med. 2020;95:1499-1506.

- Hegewisch A, Hartmann H. Occupational segregation and the gender wage gap: a job half done. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. 2014. https://iwpr.org/iwpr-issues/employment-and-earnings /occupational-segregation-and-the-gender-wage-gap-a-job-half -done/. Accessed August 26, 2021.

- Greenberg CC. Association for Academic Surgery presidential address: sticky floors and glass ceilings. J Surg Res. 2017;219:ix-xviii.

- Dossett LA, Vitous CA, Lindquist K, et al. Women surgeons’ experiences of interprofessional workplace conflict. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2019843.

- Morgan HK, Purkis JA, Porter AC, et al. Student evaluation of faculty physicians: gender differences in teaching evaluations. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25:453-456.

- Childs AJ, Friedman WH, Schwartz MP, et al. Female patients’ sex preferences in selection of gynecologists and surgeons. South Med J. 2005;98:405-408.

- Brown J, Drury L, Raub K, et al. Workplace harassment and discrimination in gynecology: results of the AAGL Member Survey. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:838-846.

- Temkin AM, Rubinsak L, Benoit MF, et al. Take me to your leader: reporting structures and equity in academic gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;157:759-764.

- Shakil S, Redberg RF. Gender disparities in sponsorship—how they perpetuate the glass ceiling. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:582.

- Hansen M, Schoonover A, Skarica B, et al. Implicit gender bias among US resident physicians. BMC Med Ed. 2019;19:396.

- Estrada M, Burnett M, Campbell AG, et al. Improving underrepresented minority student persistence in STEM. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15:es5.

- Carnes M, Handelsman J, Sheridan J. Diversity in academic medicine: the stages of change model. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2005;14:471-475.

- Person SD, Jordan CG, Allison JJ, et al. Measuring diversity and inclusion in academic medicine. The Diversity Engagement Survey. Acad Med. 2015;90:1675-1683.

- Fitzgerald CA, Smith RN, Luo-Owen X, et al. Screening for harassment, abuse, and discrimination among surgery residents: an EAST multicenter trial. Am Surg. 2019;85:456-461.

- Hayes SN, Noseworthy JH, Farrugia G. A structured compensation plan results in equitable physician compensation: a single-center analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:35-43.

- Devine PG, Forscher PS, Cox WT, et al. A gender bias habit-breaking intervention led to increased hiring of female faculty in STEMM departments. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2017;73:211-215.

- Morgan AU, Chaiyachati KH, Weissman GE, et al. Eliminating genderbased bias in academic medicine: more than naming the “elephant in the room.” J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:966-968.

- Mello MM, Jagsi R. Standing up against gender bias and harassment— a matter of professional ethics. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1385-1387.

- Burgess A, van Diggele C, Mellis C. Mentorship in the health profession: a review. Clin Teach. 2018;15:197-202.

- Rayburn WF. The Obstetrician-Gynecologist Workforce in the United States: Facts, Figures, and Implications, 2017. Washington, DC: American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

- Carnes M. Commentary: deconstructing gender differences. Acad Med. 2010;85:575-577.

- Eagly AH. The his and hers of prosocial behavior: an examination of the social psychology of gender. Am Psychol. 2009;64:644-658.

- Salles A, Awad M, Goldin L, et al. Estimating implicit and explicit gender bias among health care professionals and surgeons. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e196545.

- Carnes M, Bartels CM, Kaatz A, et al. Why is John more likely to become department chair than Jennifer? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:197-214.

- Hoffman A, Grant, W, McCormick, et al. Gendered differences in letters of recommendation for transplant surgery fellowship applicants. J Surg Edu. 2019;76:427-432.

- Galvin SL, Parlier AB, Martino E, et al. Gender bias in nurse evaluations of residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(suppl 4):7S-12S.

- Gerull KM, Loe M, Seiler K, et al. Assessing gender bias in qualitative evaluations of surgical residents. Am J Surg. 2019;217:306-313.

- Meyerson SL, Sternbach JM, Zwischenberger JB, et al. The effect of gender on resident autonomy in the operating room. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:e111-e118.

- Flyckt RL, White EE, Goodman LR, et al. The use of laparoscopy simulation to explore gender differences in resident surgical confidence. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2017;2017:1945801.

- Heisler CA, Mark K, Ton J, et al. Has a critical mass of women resulted in gender equity in gynecologic surgery? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:665-673.

- Warner AS, Lehmann LS. Gender wage disparities in medicine: time to close the gap. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1334-1336.

- Gilbert SB, Allshouse A, Skaznik-Wikiel ME. Gender inequality in salaries among reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:1194-1200.

- Croft KM, Rauh LA, Orr JW, et al. Compensation differences by gender in gynecologic oncology. Society of Gynecologic Oncology Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. 2020. https://sgo.confex.com /sgo/2020/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/15762. 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Wang SS, Ackerman S. The motherhood penalty: is it alive and well in 2020? J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:688-689.

- Pelley E, Carnes M. When a specialty becomes “women’s work”: trends in and implications of specialty gender segregation in medicine. Acad Med. 2020;95:1499-1506.

- Hegewisch A, Hartmann H. Occupational segregation and the gender wage gap: a job half done. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. 2014. https://iwpr.org/iwpr-issues/employment-and-earnings /occupational-segregation-and-the-gender-wage-gap-a-job-half -done/. Accessed August 26, 2021.

- Greenberg CC. Association for Academic Surgery presidential address: sticky floors and glass ceilings. J Surg Res. 2017;219:ix-xviii.

- Dossett LA, Vitous CA, Lindquist K, et al. Women surgeons’ experiences of interprofessional workplace conflict. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2019843.

- Morgan HK, Purkis JA, Porter AC, et al. Student evaluation of faculty physicians: gender differences in teaching evaluations. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25:453-456.

- Childs AJ, Friedman WH, Schwartz MP, et al. Female patients’ sex preferences in selection of gynecologists and surgeons. South Med J. 2005;98:405-408.

- Brown J, Drury L, Raub K, et al. Workplace harassment and discrimination in gynecology: results of the AAGL Member Survey. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:838-846.

- Temkin AM, Rubinsak L, Benoit MF, et al. Take me to your leader: reporting structures and equity in academic gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;157:759-764.

- Shakil S, Redberg RF. Gender disparities in sponsorship—how they perpetuate the glass ceiling. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:582.

- Hansen M, Schoonover A, Skarica B, et al. Implicit gender bias among US resident physicians. BMC Med Ed. 2019;19:396.

- Estrada M, Burnett M, Campbell AG, et al. Improving underrepresented minority student persistence in STEM. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15:es5.

- Carnes M, Handelsman J, Sheridan J. Diversity in academic medicine: the stages of change model. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2005;14:471-475.

- Person SD, Jordan CG, Allison JJ, et al. Measuring diversity and inclusion in academic medicine. The Diversity Engagement Survey. Acad Med. 2015;90:1675-1683.

- Fitzgerald CA, Smith RN, Luo-Owen X, et al. Screening for harassment, abuse, and discrimination among surgery residents: an EAST multicenter trial. Am Surg. 2019;85:456-461.

- Hayes SN, Noseworthy JH, Farrugia G. A structured compensation plan results in equitable physician compensation: a single-center analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:35-43.

- Devine PG, Forscher PS, Cox WT, et al. A gender bias habit-breaking intervention led to increased hiring of female faculty in STEMM departments. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2017;73:211-215.

- Morgan AU, Chaiyachati KH, Weissman GE, et al. Eliminating genderbased bias in academic medicine: more than naming the “elephant in the room.” J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:966-968.

- Mello MM, Jagsi R. Standing up against gender bias and harassment— a matter of professional ethics. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1385-1387.

- Burgess A, van Diggele C, Mellis C. Mentorship in the health profession: a review. Clin Teach. 2018;15:197-202.