User login

Endometriosis is a benign disease characterized by endometrial glands and stroma outside of the uterine cavity. It is commonly associated with pelvic pain and infertility. Ectopic endometrial tissue is predominantly located in the pelvis, but it can appear anywhere in the body, where it is referred to as extragenital endometriosis. The bowel and urinary tract are the most common sites of extragenital endometriosis.1

Laparoscopic management of extragenital endometriosis has been described since the 1980s.2 However, laparoscopic management of genitourinary endometriosis is still not widespread.3,4 Physicians are often unfamiliar with the signs and symptoms of genitourinary endometriosis and fail to consider it when a patient presents with bladder pain or hematuria, which may or may not be cyclic. Furthermore, many gynecologists do not have the experience to correctly identify the various forms of endometriosis that may appear on the pelvic organ, including the serosa and peritoneum, as variable colored spots, blebs, lesions, or adhesions. Many surgeons are also not adequately trained in the advanced laparoscopic techniques required to treat genitourinary endometriosis.4

In this article, we describe the clinical presentation and diagnosis of genitourinary endometriosis and discuss laparoscopic management strategies with and without robotic assistance.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis of genitourinary endometriosis

While ureteral and bladder endometriosis are both diseases of the urinary tract, they are not always found together in the same patient. The bladder is the most commonly affected organ, followed by the ureter and kidney.3,5,6 Endometriosis of the bladder usually presents with significant lower urinary tract symptoms. In contrast, ureteral endometriosis is usually silent with no apparent urinary symptoms.

Ureteral endometriosis. Cyclic hematuria is present in less than 15% of patients with ureteral endometriosis. Some patients experience cyclic, nonspecific colicky flank pain.7-9 Otherwise, most patients present with the usual symptoms of endometriosis, such as pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea. In a systematic review, Cavaco-Gomes and colleagues described 700 patients with ureteral endometriosis; 81% reported dysmenorrhea, 70% had pelvic pain, and 66% had dyspareunia.10 Rarely, ureteral endometriosis can result in silent kidney loss if the ureter becomes severely obstructed without treatment.11,12

Continue to: The lack of symptoms makes...

The lack of symptoms makes the early diagnosis of ureteral endometriosis difficult. As with all types of endometriosis, histologic evaluation of a biopsy sample is diagnostic. Multiple imaging modalities have been used to preoperatively diagnose ureteral involvement, including computed tomography,13 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),14 intravenous pyelogram (IVP), and pelvic ultrasonography. However, each of these imaging modalities is limited in both sensitivity and the ability to characterize depth of tissue invasion.

In a study of 245 women undergoing pelvic ultrasonography, Pateman and colleagues reported that an experienced sonographer was able to visualize the bilateral ureters in 93% of cases.15 Renal ultrasonography is indicated in any woman suspected of having genitourinary tract involvement with the degree of hydroureter and level of obstruction noted during the exam.16

In our group, we perform renography to assess kidney function when hydroureter is noted preoperatively. Studies suggest that if greater than 10% of normal glomerular filtration rate remains, the kidney is considered salvageable, and near-normal function often returns following resection of disease. If preoperative kidney function is noted to be less than 10%, consultation with a nephrologist for possible nephrectomy is warranted.

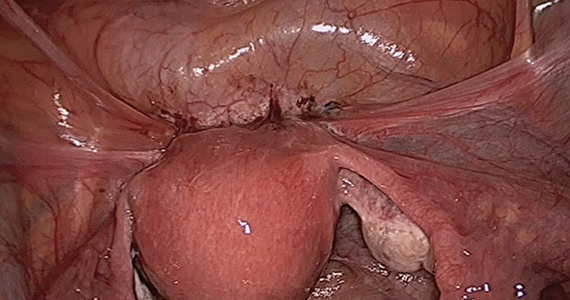

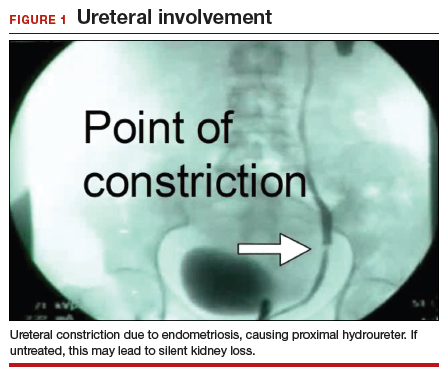

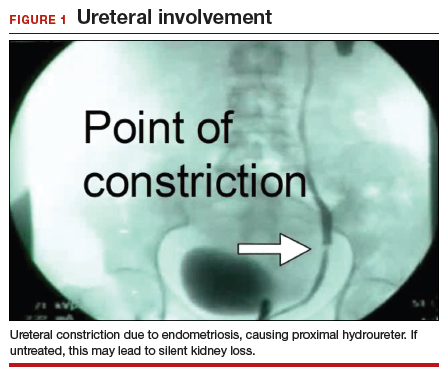

We find that IVP is often helpful for preoperatively identifying the level and degree of ureteral involvement, and it also can be used postoperatively to evaluate for ureteral continuity (FIGURE 1). Sillou and colleagues showed MRI to be adequately sensitive for the detection of intrinsic ureteral endometriosis, but they reported that MRI often overestimates the frequency of disease.17 Authors of a 2016 Cochrane review of imaging modalities for endometriosis, including 4,807 women in 49 studies, reported that no imaging test was superior to surgery for diagnosing endometriosis.18 However, the review notably excluded genitourinary tract endometriosis, as surgery is not an acceptable reference standard, given that many surgeons cannot reliably identify such lesions.18

Bladder endometriosis. Unlike patients with ureteral endometriosis, those with bladder endometriosis are typically symptomatic and experience dysuria, hematuria, urinary frequency, and suprapubic tenderness.7,19 Urinary tract infection, interstitial cystitis, and cancer must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Urinalysis and urine culture should be performed, and other diagnostic procedures such as ultrasonography, MRI, and cystoscopy should be considered to evaluate for endometriosis of the bladder.

Ultrasound and MRI of the bladder both demonstrate a high specificity for detecting bladder endometriosis, but they lack sensitivity for lesions less than 3 cm.20 Deep infiltrating endometriosis of the bladder can be identified at the time of cystoscopy, which can assist in determining the need for ureteroneocystostomy if lesions are within 2 cm of the urethral opening.20 Cystoscopy also allows for biopsy to be performed if underlying malignancy is of concern.19

In our group, when bladder endometriosis is suspected, we routinely perform preoperative bladder ultrasonography to identify the lesion and plan to perform intraoperative cystoscopy at the time of laparoscopic resection.19,21

Continue to: Treatment...

Treatment

Medical management

Empiric medical therapies for endometriosis are centered around the idea that ectopic endometrial tissue responds to treatment in a similar manner as normal eutopic endometrium. The goals of treatment are to reduce or eliminate cyclic menstruation, thereby decreasing peritoneal seeding and suppressing the growth and activity of established ectopic implants. Medical therapy commonly involves the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists, danazol, combined oral contraceptives, progestins, and aromatase inhibitors.

Medical therapy is commonly employed for patients with mild or early-stage disease and in those who are poor surgical candidates or decline surgery. Medical management alone clearly is contraindicated in the setting of ureteral obstruction and—in our opinion—may not be a good option for those with endometriosis of the ureter, given the potential for recurrence and potential serious sequelae of reduced renal function.22 Therefore, surgery has become the standard approach to therapy for mild to moderate cases of ureteral endometriosis.3

Medical therapy for patients with endometriosis of the bladder is generally considered a temporary solution as hormonal suppression, with its associated adverse effects, must be maintained throughout menopause. However, if endometriosis lesions lie within close proximity to the trigone, medical management is preferred, as surgical excision in the area of the trigone may predispose patients to neurogenic bladder and retrograde bladder reflux.23,24

Surgical management

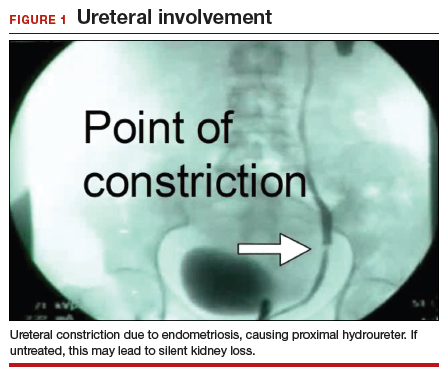

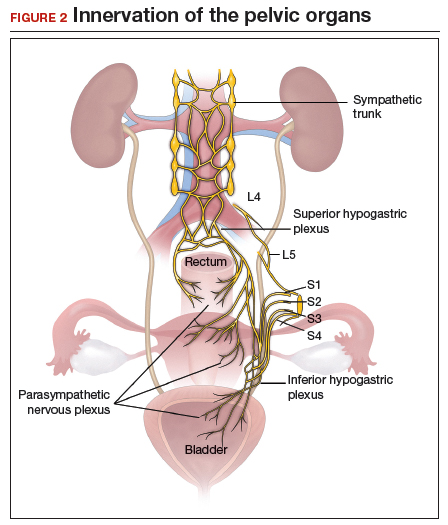

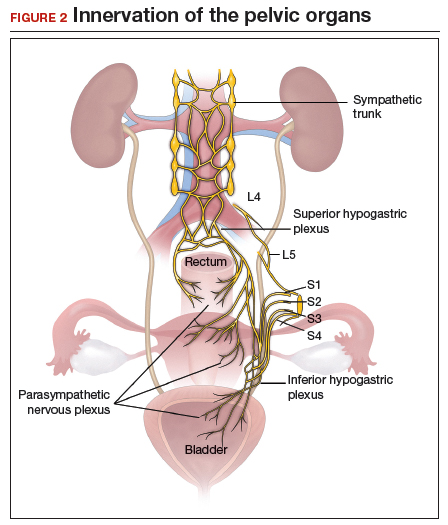

The objectives of surgical treatment for genitourinary tract endometriosis are to excise all visible disease, to prevent or delay recurrence of the disease to the extent possible, and to avoid any further morbidity—in particular, to preserve renal function in cases of ureteral endometriosis—and to avoid iatrogenic injury to surrounding pelvic nervous structures25-27 (FIGURE 2). The surgical approach depends on the technical expertise of the surgeon and the availability of necessary instrumentation. In our experience, laparoscopy with or without robotic assistance is the preferred surgical approach.3,4,6,11,28-32

Others have reported on the benefits of laparoscopy over laparotomy for the surgical management of genitourinary endometriosis. In a review of 61 patients who underwent either robot-assisted laparoscopic (n = 25) or open (n = 41) ureteroneocystostomy (n = 41), Isac and colleagues reported the procedure was longer in the laparoscopic group (279 min vs 200 min, P<.001), but the laparoscopic group had a shorter hospital stay (3 days vs 5 days, P<.001), used fewer narcotics postoperatively (P<.001), and had lower intraoperative blood loss (100 mL vs 150 mL, P<.001).32 No differences in long-term outcomes were observed in either cohort.

In a systematic review of 700 patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for ureteral endometriosis, Cavaco-Gomes and colleagues reported that conversion to laparotomy occurred in only 3% to 7% of cases.10 In instances of ureteral endometriosis, laparoscopy provides greater visualization of the intraperitoneal contents over laparotomy, enabling better evaluation and treatment of lesions.3,29,33,34 Robot-assisted laparoscopy provides the additional advantages of 3D visualization, potential for an accelerated learning curve over traditional laparoscopy, improvement in dissection technique, and ease of suturing technique.6,35,36

Continue to: Extrinsic disease...

Extrinsic disease. In our group, we perform ureterolysis for extrinsic disease.25 The peritoneal incision is made in an area unaffected by endometriosis. Using the suction irrigator, a potential space is developed under the serosa of the ureter by injecting normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution. By creating a fluid barrier between the serosa and underlying tissues, the depth of surgical incision and lateral thermal spread are minimized. Grasping forceps are used to peel the peritoneum away.25,37,38

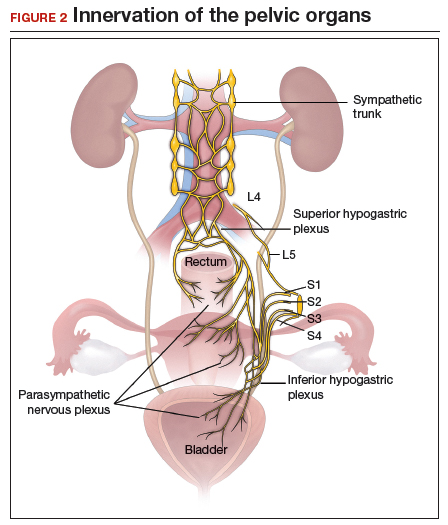

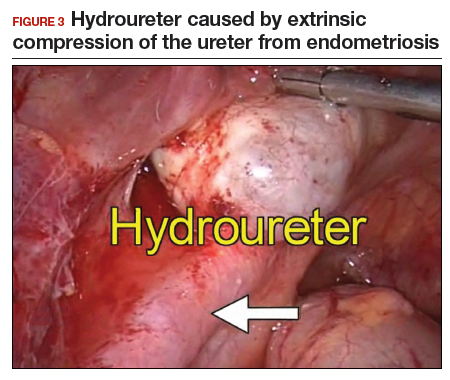

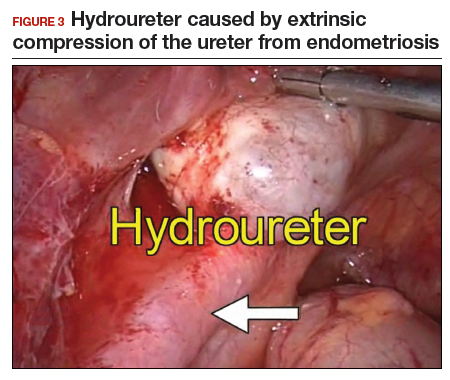

Intrinsic disease. Unlike extrinsic disease, intrinsic disease can infiltrate the muscularis, lamina propria, and ureteral lumen, resulting in proximal dilation of the ureter with strictures.8 In this situation, ureteral compromise is likely and resection of the ureter is indicated3,28 (FIGURE 3). Intrinsic disease can be suggested by preoperative imaging or when there is evidence of deep infiltrating disease on physical exam, such as rectovaginal nodularity.30,39 When intrinsic ureteral disease is known, consultation with a urologist to plan a joint procedure is advisable. The procedure chosen to re-establish a functional ureter following resection depends on the location and extent of the involved ureter. Resection in close proximity to the bladder may be repaired by ureteroneocystostomy with or without psoas hitch,30,39,40 whereas resection of more proximal ureter may be repaired using Boari flap, ileal interposition, or autotransplantation. Lesions in the upper third or middle ureter may be repaired using ureterouretral anastomosis.6,7,30,41-43

Continue to: Bladder endometriosis...

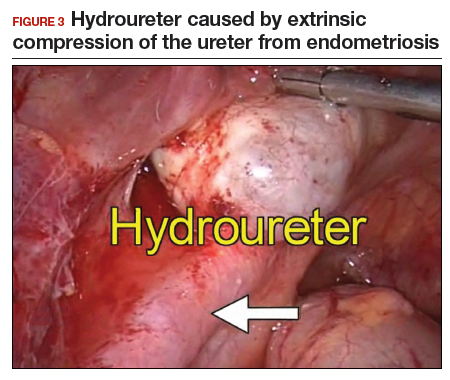

Bladder endometriosis. Surgical treatment for bladder endometriosis depends on the depth of invasion and the location of the lesion (FIGURE 4). Lesions of the superficial aspect of the bladder identified at the time of laparoscopy can be treated with either excision or fulguration28,35,44 In our group, we perform excision over fulguration to remove the entire lesion and obtain a pathologic diagnosis. Deeper lesions involving the detrusor muscle are likely to be an endometrioma of the bladder. In these cases, laparoscopic excision is recommended.7 Rarely, lesions close to the interureteric ridge may require ureteroneocystostomy.19,45

In our experience, laparoscopic resection of bladder endometriomas is associated with better results in terms of symptom relief, progression of disease, and recurrence risk compared with other approaches. When performing laparoscopic excision of bladder lesions, we concomitantly evaluate the bladder lesion via cystoscopy to ensure adequate margins are obtained. Double-J stent placement is advised when lesions are within 2 cm of the urethral meatus to ensure ureteral patency during the postoperative period.45 A postoperative cystogram routinely is performed 7 to 14 days after surgery to ensure adequate repair prior to removing the urinary catheter.9,25,46,47

Postsurgical follow-up

Follow-up after treatment of genitourinary tract endometriosis should include monitoring the patient for symptoms of recurrence. Regular history and physical examination, renal function testing, and, in some instances, pelvic ultrasonography, all have a role in surveillance for recurrent ureteric disease. IVP or MRI may be warranted if a recurrence is suspected. A high index of suspicion should be maintained on the part of the clinician to avoid the devastating consequences of silent kidney loss. Patients should be counseled about the risk of disease recurrence, especially in those not undergoing postoperative hormonal suppression.

In conclusion

While endometriosis of the genitourinary tract is rare, patients can experience significant morbidity. Medical management of the disease is often limited by substantial adverse effects that limit treatment duration and is best used postoperatively after excision. An adequate physical exam and preoperative diagnostic imaging can be employed to characterize the extent of disease. When extensive disease involving the ureter is suspected, preoperative consultation with a urologist is encouraged to plan a multidisciplinary approach to surgical resection.

The ideal approach to surgery is laparoscopic resection with or without robotic assistance. Treatment of ureteral disease most commonly involves ureterolysis for cases of extrinsic disease but may require total resection of the ureter with concurrent ureteral reconstruction when disease is intrinsic to the ureter. Surgery for bladder endometriosis depends on the depth of invasion and location of the lesion. Superficial bladder lesions can be treated with fulguration or excision, while deeper lesions involving the detrusor muscle require excision. Lesions in close proximity to the interureteric ridge may require ureteroneocystostomy. Follow-up after excisional procedures involves monitoring the patient for signs and symptoms of disease recurrence, especially in cases of ureteral involvement, to avoid the devastating consequences of silent kidney loss.

The definitive cause of endometriosis remains unknown, but several prominent theories have been proposed.

Sampson's theory of retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes is the most well-known theory,1 although Schron had acknowledged a similar thought 3 centuries before.2 This theory posits that refluxed endometrial cells enter the abdominal cavity and invade the peritoneum, developing a blood supply necessary for survival and growth. Early reports supported this theory by suggesting that women with genital tract obstruction have a higher incidence of endometriosis.3,4 However, it was later confirmed that women without genital tract obstruction have a similar incidence of retrograde menstruation. In fact, up to 90% of women are found to have retrograde menstruation, but only 10% develop endometriosis. This suggests that once endometrial cells have escaped the uterine cavity, other events are necessary for endometrial cells to implant and survive.3,5 Other evidence to support the theory of retrograde menstruation is the observation that endometriosis is most commonly observed in the dependent portions of the pelvis, on the ovaries, in the anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and on the uterosacral ligament.6

The coelomic metaplasia theory holds that endometriosis results from spontaneous metaplastic change to mesothelial cells derived from the coelomic epithelium (located in the peritoneum and the pleura) upon exposure to menstrual effluent or other stimuli.7 Evidence for this theory is supported by the observation that intact endometrial cells have no access to the thoracic cavity in the absence of anatomical defect; therefore, the implantation theory cannot explain cases of pleural or pulmonary endometriosis.

Immune dysregulation also has been invoked to explain endometriosis implants both inside and outside the genitourinary tract. Studies have shown a higher incidence of endometriosis in women with other autoimmune disorders, including hypothyroidism, chronic fatigue syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren syndrome, and multiple sclerosis as well as in women with allergies, asthma, and eczema.8 In such women, dysregulation of the innate and adaptive immune system might promote the disease by inhibiting apoptosis of ectopic endometrial cells and by promoting their attachment, invasion, and proliferation into healthy peritoneum through the secretion of various growth factors and cytokines.9,10

Other possible theories that might explain the pathogenesis of endometriosis exist.11-13 While each theory has documented supporting evidence, no single theory currently accounts for all cases of endometriosis. It is likely, then, that endometriosis is a multifactorial disease with a combination of immune dysregulation, molecular abnormalities, genetic and epigenetic factors, and environmental exposures involved in its pathogenesis.

References

- Sampson J. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14:422-469.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Endometriosis: ancient disease, ancient treatments. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(6 suppl):S1-62.

- Halme J, Hammond MG, Hulka JF, et al. Retrograde menstruation in healthy women and in patients with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:151-154.

- Sanfilippo JS, Wakim NG, Schikler KN, et al. Endometriosis in association with uterine anomaly. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:39-43.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511-519.

- Vercellini P, Chapron C, Fedele L, et al. Evidence for asymmetric distribution of lower intestinal tract endometriosis. BJOG. 2004;111:1213-1217.

- Sourial S, Tempest N, Hapangama DK. Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Int J Reprod Med. 2014;2014:179515.

- Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, et al. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2715-2724.

- Lebovic DI, Mueller MD, Taylor RN. Immunobiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:1-10.

- Sidell N, Han SW, Parthasarathy S. Regulation and modulation of abnormal immune responses in endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;955: 159-173; discussion 199-200, 396-406.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. The pathogenesis of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013;252-258.

- Buka NJ. Vesical endometriosis after cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:1117-1118.

- Price DT, Maloney KE, Ibrahim GK, et al. Vesical endometriosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Urology. 1996;48:639-643.

- Veeraswamy A, Lewis M, Mann A, et al. Extragenital endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:449-466.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison GP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1986;45:778-783.

- Bosev D, Nicoll LM, Bhagan L, et al. Laparoscopic management of ureteral endometriosis: the Stanford University hospital experience with 96 consecutive cases. J Urol. 2009;182:2748-2752.

- Nezhat C, Falik R, McKinney S, et al. Pathophysiology and management of urinary tract endometriosis. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:359-372.

- Shook TE, Nyberg LM. Endometriosis of the urinary tract. Urology. 1988;31:1-6.

- Nezhat C, Modest AM, King LP. The role of the robot in treating urinary tract endometriosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:308-311.

- Comiter CV. Endometriosis of the urinary tract. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:625-635.

- Gustilo-Ashby AM, Paraiso MF. Treatment of urinary tract endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:559-565.

- Berlanda N, Somigliana E, Frattaruolo MP, et al. Surgery versus hormonal therapy for deep endometriosis: is it a choice of the physician? Eur J Obstet Gyneocol Reprod Biol. 2017;209:67-71.

- Cavaco-Gomes J, Martinho M, Gilabert-Aguilar J, et al. Laparoscopic management of ureteral endometriosis: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:94-101.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Green B. Laparoscopic treatment of obstructed ureter due to endometriosis by resection and ureteroureterostomy: a case report. J Urol. 1992;148:865-868.

- Nezhat C, Paka C, Gomaa M, et al. Silent loss of kidney secondary to ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2012;16:451-455.

- Iosca S, Lumia D, Bracchi E, et al. Multislice computed tomography with colon water distention (MSCT-c) in the study of intestinal and ureteral endometriosis. Clin Imaging. 2013;37(6):1061-1068.

- Medeiros LR, Rosa MI, Silva BR, et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance in deeply infiltrating endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291:611-621.

- Pateman K, Mavrelos D, Hoo WL, et al. Visualization of ureters on standard gynecological transvaginal scan: a feasibility study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:696-701.

- Guerriero S, Condous G, van den Bosch T, et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48:318-332.

- Sillou S, Poirée S, Millischer AE, et al. Urinary endometriosis: MR imaging appearance with surgical and histological correlations. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:373-381.

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, et al. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591.

- Nezhat CH, Malik S, Osias J, et al. Laparoscopic management of 15 patients with infiltrating endometriosis of the bladder and a case of primary intravesical endometrioid adenosarcoma. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:872-875.

- Kolodziej A, Krajewski W, Dolowy L, et al. Urinary tract endometriosis. Urol J. 2015;12:2213-2217.

- Nezhat C, Buescher E, Paka C, et al. Video-assisted laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013;265.

- Al-Fozan H, Tulandi T. Left lateral predisposition of endometriosis and endometrioma. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:164-166.

- Hastings JC, Van Winkle W, Barker E, et al. The effect of suture materials on healing wounds of the bladder. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:933-937.

- Cornell KK. Cystotomy, partial cystectomy, and tube cystostomy. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2000;15:11-16.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Uccella S, Cromi A, Casarin J, et al. Laparoscopy for ureteral endometriosis: surgical details, long-term follow-up, and fertility outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:160-166.e2.

- Knabben L, Imboden S, Fellmann B, et al. Urinary tract endometriosis in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis: prevalence, symptoms, management, and proposal for a new clinical classification. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:147-152.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, et al. Urinary tract endometriosis treated by laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:920-924.

- Nezhat CH, Nezhat F, Seidman D, et al. Laparoscopic ureteroureterostomy: a prospective follow-up of 9 patients. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 1998;5:200.

- Nezhat CH, Bracale U, Scala A, et al. Laparoscopic ureteroneocystostomy and vesicopsoas hitch for infiltrative endometriosis. JSLS. 2004;8:3-7.

- Nezhat C, Lewis M, Kotikela S, et al. Robotic versus standard laparoscopy for the treatment of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2758-2760.

- Isac W, Kaouk J, Altunrende F, et al. Robotic-assisted ureteroneocytostomy: techniques and comparative outcomes. J Endourol. 2013;27:318-323.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F. Laparoscopic repair of ureter resected during operative laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80(3 pt 2):543-544.

- De Cicco C, Ussia A, Koninckx PR. Laparoscopic ureteral repair in gynaecological surgery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23:296-300.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic treatment of bowel, bladder, and ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2011;15:387-392.

- Fadhlaoui A, Gillon T, Lebbi I, et al. Endometriosis and vesico-sphincteral disorders. Front Surg. 2015;2:23.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat FR. Safe laser endoscopic excision or vaporization of peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1989;52:149-151.

- Nezhat C, Winer W, Nezhat FA. Comparison of the CO2, argon, and KTP/532 lasers in the videolaseroscopic treatment of endometriosis. J Gynecol Surg. 2009;41-47.

- Azioni G, Bracale U, Scala A, et al. Laparoscopic ureteroneocytostomy and vesicopsoas hitch for infiltrative ureteral endometriosis. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2010;19:292-297.

- Stepniewska A, Grosso G, Molon A, et al. Ureteral endometriosis: clinical and radiological follow-up after laparoscopic ureterocystoneostomy. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:112-116.

- Nezhat CH, Nezhat FR, Freiha F, et al. Laparoscopic vesicopsoas hitch for infiltrative ureteral endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:376-379.

- Scioscia M, Molon A, Grosso G, et al. Laparoscopic management of ureteral endometriosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21:325-328.

- Antonelli A. Urinary tract endometriosis. Urologia. 2012;79:167-170.

- Camanni M, Bonino L, Delpiano EM, et al. Laparoscopic conservative management of ureteral endometriosis: a survey of eighty patients submitted to ureterolysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:109.

- Chapron C, Bourret A, Chopin N, et al. Surgery for bladder endometriosis: long-term results and concomitant management of associated posterior deep lesions. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:884-889.

- Nezhat CR, Nezhat FR. Laparoscopic segmental bladder resection for endometriosis: a report of two cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81(5 pt 2):882-884.

- Bourdel N, Cognet S, Canis M, et al. Laparoscopic ureteroneocystostomy: be prepared! J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:827-833.

- Page B. Camran Nezhat and the Advent of Advanced Operative Video-laparoscopy. In: Nezhat C, ed. Nezhat's History of Endoscopy. Tuttlingen, Germany: Endo Press; 2011:159-187.

- Podratz K. Degrees of Freedom: Advances in Gynecological and Obstetrical Surgery. Remembering Milestones and Achievements in Surgery: Inspiring Quality for a Hundred Years 1913-2012. Published by American College of Surgeons 2012. Tampa, FL: Faircount Media Group; 2013.

- Kelley WE. The evolution of laparoscopy and the revolution in surgery in the decade of the 1990s. JSLS: J Soc Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2008;12:351-357.

Endometriosis is a benign disease characterized by endometrial glands and stroma outside of the uterine cavity. It is commonly associated with pelvic pain and infertility. Ectopic endometrial tissue is predominantly located in the pelvis, but it can appear anywhere in the body, where it is referred to as extragenital endometriosis. The bowel and urinary tract are the most common sites of extragenital endometriosis.1

Laparoscopic management of extragenital endometriosis has been described since the 1980s.2 However, laparoscopic management of genitourinary endometriosis is still not widespread.3,4 Physicians are often unfamiliar with the signs and symptoms of genitourinary endometriosis and fail to consider it when a patient presents with bladder pain or hematuria, which may or may not be cyclic. Furthermore, many gynecologists do not have the experience to correctly identify the various forms of endometriosis that may appear on the pelvic organ, including the serosa and peritoneum, as variable colored spots, blebs, lesions, or adhesions. Many surgeons are also not adequately trained in the advanced laparoscopic techniques required to treat genitourinary endometriosis.4

In this article, we describe the clinical presentation and diagnosis of genitourinary endometriosis and discuss laparoscopic management strategies with and without robotic assistance.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis of genitourinary endometriosis

While ureteral and bladder endometriosis are both diseases of the urinary tract, they are not always found together in the same patient. The bladder is the most commonly affected organ, followed by the ureter and kidney.3,5,6 Endometriosis of the bladder usually presents with significant lower urinary tract symptoms. In contrast, ureteral endometriosis is usually silent with no apparent urinary symptoms.

Ureteral endometriosis. Cyclic hematuria is present in less than 15% of patients with ureteral endometriosis. Some patients experience cyclic, nonspecific colicky flank pain.7-9 Otherwise, most patients present with the usual symptoms of endometriosis, such as pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea. In a systematic review, Cavaco-Gomes and colleagues described 700 patients with ureteral endometriosis; 81% reported dysmenorrhea, 70% had pelvic pain, and 66% had dyspareunia.10 Rarely, ureteral endometriosis can result in silent kidney loss if the ureter becomes severely obstructed without treatment.11,12

Continue to: The lack of symptoms makes...

The lack of symptoms makes the early diagnosis of ureteral endometriosis difficult. As with all types of endometriosis, histologic evaluation of a biopsy sample is diagnostic. Multiple imaging modalities have been used to preoperatively diagnose ureteral involvement, including computed tomography,13 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),14 intravenous pyelogram (IVP), and pelvic ultrasonography. However, each of these imaging modalities is limited in both sensitivity and the ability to characterize depth of tissue invasion.

In a study of 245 women undergoing pelvic ultrasonography, Pateman and colleagues reported that an experienced sonographer was able to visualize the bilateral ureters in 93% of cases.15 Renal ultrasonography is indicated in any woman suspected of having genitourinary tract involvement with the degree of hydroureter and level of obstruction noted during the exam.16

In our group, we perform renography to assess kidney function when hydroureter is noted preoperatively. Studies suggest that if greater than 10% of normal glomerular filtration rate remains, the kidney is considered salvageable, and near-normal function often returns following resection of disease. If preoperative kidney function is noted to be less than 10%, consultation with a nephrologist for possible nephrectomy is warranted.

We find that IVP is often helpful for preoperatively identifying the level and degree of ureteral involvement, and it also can be used postoperatively to evaluate for ureteral continuity (FIGURE 1). Sillou and colleagues showed MRI to be adequately sensitive for the detection of intrinsic ureteral endometriosis, but they reported that MRI often overestimates the frequency of disease.17 Authors of a 2016 Cochrane review of imaging modalities for endometriosis, including 4,807 women in 49 studies, reported that no imaging test was superior to surgery for diagnosing endometriosis.18 However, the review notably excluded genitourinary tract endometriosis, as surgery is not an acceptable reference standard, given that many surgeons cannot reliably identify such lesions.18

Bladder endometriosis. Unlike patients with ureteral endometriosis, those with bladder endometriosis are typically symptomatic and experience dysuria, hematuria, urinary frequency, and suprapubic tenderness.7,19 Urinary tract infection, interstitial cystitis, and cancer must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Urinalysis and urine culture should be performed, and other diagnostic procedures such as ultrasonography, MRI, and cystoscopy should be considered to evaluate for endometriosis of the bladder.

Ultrasound and MRI of the bladder both demonstrate a high specificity for detecting bladder endometriosis, but they lack sensitivity for lesions less than 3 cm.20 Deep infiltrating endometriosis of the bladder can be identified at the time of cystoscopy, which can assist in determining the need for ureteroneocystostomy if lesions are within 2 cm of the urethral opening.20 Cystoscopy also allows for biopsy to be performed if underlying malignancy is of concern.19

In our group, when bladder endometriosis is suspected, we routinely perform preoperative bladder ultrasonography to identify the lesion and plan to perform intraoperative cystoscopy at the time of laparoscopic resection.19,21

Continue to: Treatment...

Treatment

Medical management

Empiric medical therapies for endometriosis are centered around the idea that ectopic endometrial tissue responds to treatment in a similar manner as normal eutopic endometrium. The goals of treatment are to reduce or eliminate cyclic menstruation, thereby decreasing peritoneal seeding and suppressing the growth and activity of established ectopic implants. Medical therapy commonly involves the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists, danazol, combined oral contraceptives, progestins, and aromatase inhibitors.

Medical therapy is commonly employed for patients with mild or early-stage disease and in those who are poor surgical candidates or decline surgery. Medical management alone clearly is contraindicated in the setting of ureteral obstruction and—in our opinion—may not be a good option for those with endometriosis of the ureter, given the potential for recurrence and potential serious sequelae of reduced renal function.22 Therefore, surgery has become the standard approach to therapy for mild to moderate cases of ureteral endometriosis.3

Medical therapy for patients with endometriosis of the bladder is generally considered a temporary solution as hormonal suppression, with its associated adverse effects, must be maintained throughout menopause. However, if endometriosis lesions lie within close proximity to the trigone, medical management is preferred, as surgical excision in the area of the trigone may predispose patients to neurogenic bladder and retrograde bladder reflux.23,24

Surgical management

The objectives of surgical treatment for genitourinary tract endometriosis are to excise all visible disease, to prevent or delay recurrence of the disease to the extent possible, and to avoid any further morbidity—in particular, to preserve renal function in cases of ureteral endometriosis—and to avoid iatrogenic injury to surrounding pelvic nervous structures25-27 (FIGURE 2). The surgical approach depends on the technical expertise of the surgeon and the availability of necessary instrumentation. In our experience, laparoscopy with or without robotic assistance is the preferred surgical approach.3,4,6,11,28-32

Others have reported on the benefits of laparoscopy over laparotomy for the surgical management of genitourinary endometriosis. In a review of 61 patients who underwent either robot-assisted laparoscopic (n = 25) or open (n = 41) ureteroneocystostomy (n = 41), Isac and colleagues reported the procedure was longer in the laparoscopic group (279 min vs 200 min, P<.001), but the laparoscopic group had a shorter hospital stay (3 days vs 5 days, P<.001), used fewer narcotics postoperatively (P<.001), and had lower intraoperative blood loss (100 mL vs 150 mL, P<.001).32 No differences in long-term outcomes were observed in either cohort.

In a systematic review of 700 patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for ureteral endometriosis, Cavaco-Gomes and colleagues reported that conversion to laparotomy occurred in only 3% to 7% of cases.10 In instances of ureteral endometriosis, laparoscopy provides greater visualization of the intraperitoneal contents over laparotomy, enabling better evaluation and treatment of lesions.3,29,33,34 Robot-assisted laparoscopy provides the additional advantages of 3D visualization, potential for an accelerated learning curve over traditional laparoscopy, improvement in dissection technique, and ease of suturing technique.6,35,36

Continue to: Extrinsic disease...

Extrinsic disease. In our group, we perform ureterolysis for extrinsic disease.25 The peritoneal incision is made in an area unaffected by endometriosis. Using the suction irrigator, a potential space is developed under the serosa of the ureter by injecting normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution. By creating a fluid barrier between the serosa and underlying tissues, the depth of surgical incision and lateral thermal spread are minimized. Grasping forceps are used to peel the peritoneum away.25,37,38

Intrinsic disease. Unlike extrinsic disease, intrinsic disease can infiltrate the muscularis, lamina propria, and ureteral lumen, resulting in proximal dilation of the ureter with strictures.8 In this situation, ureteral compromise is likely and resection of the ureter is indicated3,28 (FIGURE 3). Intrinsic disease can be suggested by preoperative imaging or when there is evidence of deep infiltrating disease on physical exam, such as rectovaginal nodularity.30,39 When intrinsic ureteral disease is known, consultation with a urologist to plan a joint procedure is advisable. The procedure chosen to re-establish a functional ureter following resection depends on the location and extent of the involved ureter. Resection in close proximity to the bladder may be repaired by ureteroneocystostomy with or without psoas hitch,30,39,40 whereas resection of more proximal ureter may be repaired using Boari flap, ileal interposition, or autotransplantation. Lesions in the upper third or middle ureter may be repaired using ureterouretral anastomosis.6,7,30,41-43

Continue to: Bladder endometriosis...

Bladder endometriosis. Surgical treatment for bladder endometriosis depends on the depth of invasion and the location of the lesion (FIGURE 4). Lesions of the superficial aspect of the bladder identified at the time of laparoscopy can be treated with either excision or fulguration28,35,44 In our group, we perform excision over fulguration to remove the entire lesion and obtain a pathologic diagnosis. Deeper lesions involving the detrusor muscle are likely to be an endometrioma of the bladder. In these cases, laparoscopic excision is recommended.7 Rarely, lesions close to the interureteric ridge may require ureteroneocystostomy.19,45

In our experience, laparoscopic resection of bladder endometriomas is associated with better results in terms of symptom relief, progression of disease, and recurrence risk compared with other approaches. When performing laparoscopic excision of bladder lesions, we concomitantly evaluate the bladder lesion via cystoscopy to ensure adequate margins are obtained. Double-J stent placement is advised when lesions are within 2 cm of the urethral meatus to ensure ureteral patency during the postoperative period.45 A postoperative cystogram routinely is performed 7 to 14 days after surgery to ensure adequate repair prior to removing the urinary catheter.9,25,46,47

Postsurgical follow-up

Follow-up after treatment of genitourinary tract endometriosis should include monitoring the patient for symptoms of recurrence. Regular history and physical examination, renal function testing, and, in some instances, pelvic ultrasonography, all have a role in surveillance for recurrent ureteric disease. IVP or MRI may be warranted if a recurrence is suspected. A high index of suspicion should be maintained on the part of the clinician to avoid the devastating consequences of silent kidney loss. Patients should be counseled about the risk of disease recurrence, especially in those not undergoing postoperative hormonal suppression.

In conclusion

While endometriosis of the genitourinary tract is rare, patients can experience significant morbidity. Medical management of the disease is often limited by substantial adverse effects that limit treatment duration and is best used postoperatively after excision. An adequate physical exam and preoperative diagnostic imaging can be employed to characterize the extent of disease. When extensive disease involving the ureter is suspected, preoperative consultation with a urologist is encouraged to plan a multidisciplinary approach to surgical resection.

The ideal approach to surgery is laparoscopic resection with or without robotic assistance. Treatment of ureteral disease most commonly involves ureterolysis for cases of extrinsic disease but may require total resection of the ureter with concurrent ureteral reconstruction when disease is intrinsic to the ureter. Surgery for bladder endometriosis depends on the depth of invasion and location of the lesion. Superficial bladder lesions can be treated with fulguration or excision, while deeper lesions involving the detrusor muscle require excision. Lesions in close proximity to the interureteric ridge may require ureteroneocystostomy. Follow-up after excisional procedures involves monitoring the patient for signs and symptoms of disease recurrence, especially in cases of ureteral involvement, to avoid the devastating consequences of silent kidney loss.

The definitive cause of endometriosis remains unknown, but several prominent theories have been proposed.

Sampson's theory of retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes is the most well-known theory,1 although Schron had acknowledged a similar thought 3 centuries before.2 This theory posits that refluxed endometrial cells enter the abdominal cavity and invade the peritoneum, developing a blood supply necessary for survival and growth. Early reports supported this theory by suggesting that women with genital tract obstruction have a higher incidence of endometriosis.3,4 However, it was later confirmed that women without genital tract obstruction have a similar incidence of retrograde menstruation. In fact, up to 90% of women are found to have retrograde menstruation, but only 10% develop endometriosis. This suggests that once endometrial cells have escaped the uterine cavity, other events are necessary for endometrial cells to implant and survive.3,5 Other evidence to support the theory of retrograde menstruation is the observation that endometriosis is most commonly observed in the dependent portions of the pelvis, on the ovaries, in the anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and on the uterosacral ligament.6

The coelomic metaplasia theory holds that endometriosis results from spontaneous metaplastic change to mesothelial cells derived from the coelomic epithelium (located in the peritoneum and the pleura) upon exposure to menstrual effluent or other stimuli.7 Evidence for this theory is supported by the observation that intact endometrial cells have no access to the thoracic cavity in the absence of anatomical defect; therefore, the implantation theory cannot explain cases of pleural or pulmonary endometriosis.

Immune dysregulation also has been invoked to explain endometriosis implants both inside and outside the genitourinary tract. Studies have shown a higher incidence of endometriosis in women with other autoimmune disorders, including hypothyroidism, chronic fatigue syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren syndrome, and multiple sclerosis as well as in women with allergies, asthma, and eczema.8 In such women, dysregulation of the innate and adaptive immune system might promote the disease by inhibiting apoptosis of ectopic endometrial cells and by promoting their attachment, invasion, and proliferation into healthy peritoneum through the secretion of various growth factors and cytokines.9,10

Other possible theories that might explain the pathogenesis of endometriosis exist.11-13 While each theory has documented supporting evidence, no single theory currently accounts for all cases of endometriosis. It is likely, then, that endometriosis is a multifactorial disease with a combination of immune dysregulation, molecular abnormalities, genetic and epigenetic factors, and environmental exposures involved in its pathogenesis.

References

- Sampson J. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14:422-469.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Endometriosis: ancient disease, ancient treatments. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(6 suppl):S1-62.

- Halme J, Hammond MG, Hulka JF, et al. Retrograde menstruation in healthy women and in patients with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:151-154.

- Sanfilippo JS, Wakim NG, Schikler KN, et al. Endometriosis in association with uterine anomaly. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:39-43.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511-519.

- Vercellini P, Chapron C, Fedele L, et al. Evidence for asymmetric distribution of lower intestinal tract endometriosis. BJOG. 2004;111:1213-1217.

- Sourial S, Tempest N, Hapangama DK. Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Int J Reprod Med. 2014;2014:179515.

- Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, et al. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2715-2724.

- Lebovic DI, Mueller MD, Taylor RN. Immunobiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:1-10.

- Sidell N, Han SW, Parthasarathy S. Regulation and modulation of abnormal immune responses in endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;955: 159-173; discussion 199-200, 396-406.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. The pathogenesis of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013;252-258.

- Buka NJ. Vesical endometriosis after cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:1117-1118.

- Price DT, Maloney KE, Ibrahim GK, et al. Vesical endometriosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Urology. 1996;48:639-643.

Endometriosis is a benign disease characterized by endometrial glands and stroma outside of the uterine cavity. It is commonly associated with pelvic pain and infertility. Ectopic endometrial tissue is predominantly located in the pelvis, but it can appear anywhere in the body, where it is referred to as extragenital endometriosis. The bowel and urinary tract are the most common sites of extragenital endometriosis.1

Laparoscopic management of extragenital endometriosis has been described since the 1980s.2 However, laparoscopic management of genitourinary endometriosis is still not widespread.3,4 Physicians are often unfamiliar with the signs and symptoms of genitourinary endometriosis and fail to consider it when a patient presents with bladder pain or hematuria, which may or may not be cyclic. Furthermore, many gynecologists do not have the experience to correctly identify the various forms of endometriosis that may appear on the pelvic organ, including the serosa and peritoneum, as variable colored spots, blebs, lesions, or adhesions. Many surgeons are also not adequately trained in the advanced laparoscopic techniques required to treat genitourinary endometriosis.4

In this article, we describe the clinical presentation and diagnosis of genitourinary endometriosis and discuss laparoscopic management strategies with and without robotic assistance.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis of genitourinary endometriosis

While ureteral and bladder endometriosis are both diseases of the urinary tract, they are not always found together in the same patient. The bladder is the most commonly affected organ, followed by the ureter and kidney.3,5,6 Endometriosis of the bladder usually presents with significant lower urinary tract symptoms. In contrast, ureteral endometriosis is usually silent with no apparent urinary symptoms.

Ureteral endometriosis. Cyclic hematuria is present in less than 15% of patients with ureteral endometriosis. Some patients experience cyclic, nonspecific colicky flank pain.7-9 Otherwise, most patients present with the usual symptoms of endometriosis, such as pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea. In a systematic review, Cavaco-Gomes and colleagues described 700 patients with ureteral endometriosis; 81% reported dysmenorrhea, 70% had pelvic pain, and 66% had dyspareunia.10 Rarely, ureteral endometriosis can result in silent kidney loss if the ureter becomes severely obstructed without treatment.11,12

Continue to: The lack of symptoms makes...

The lack of symptoms makes the early diagnosis of ureteral endometriosis difficult. As with all types of endometriosis, histologic evaluation of a biopsy sample is diagnostic. Multiple imaging modalities have been used to preoperatively diagnose ureteral involvement, including computed tomography,13 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),14 intravenous pyelogram (IVP), and pelvic ultrasonography. However, each of these imaging modalities is limited in both sensitivity and the ability to characterize depth of tissue invasion.

In a study of 245 women undergoing pelvic ultrasonography, Pateman and colleagues reported that an experienced sonographer was able to visualize the bilateral ureters in 93% of cases.15 Renal ultrasonography is indicated in any woman suspected of having genitourinary tract involvement with the degree of hydroureter and level of obstruction noted during the exam.16

In our group, we perform renography to assess kidney function when hydroureter is noted preoperatively. Studies suggest that if greater than 10% of normal glomerular filtration rate remains, the kidney is considered salvageable, and near-normal function often returns following resection of disease. If preoperative kidney function is noted to be less than 10%, consultation with a nephrologist for possible nephrectomy is warranted.

We find that IVP is often helpful for preoperatively identifying the level and degree of ureteral involvement, and it also can be used postoperatively to evaluate for ureteral continuity (FIGURE 1). Sillou and colleagues showed MRI to be adequately sensitive for the detection of intrinsic ureteral endometriosis, but they reported that MRI often overestimates the frequency of disease.17 Authors of a 2016 Cochrane review of imaging modalities for endometriosis, including 4,807 women in 49 studies, reported that no imaging test was superior to surgery for diagnosing endometriosis.18 However, the review notably excluded genitourinary tract endometriosis, as surgery is not an acceptable reference standard, given that many surgeons cannot reliably identify such lesions.18

Bladder endometriosis. Unlike patients with ureteral endometriosis, those with bladder endometriosis are typically symptomatic and experience dysuria, hematuria, urinary frequency, and suprapubic tenderness.7,19 Urinary tract infection, interstitial cystitis, and cancer must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Urinalysis and urine culture should be performed, and other diagnostic procedures such as ultrasonography, MRI, and cystoscopy should be considered to evaluate for endometriosis of the bladder.

Ultrasound and MRI of the bladder both demonstrate a high specificity for detecting bladder endometriosis, but they lack sensitivity for lesions less than 3 cm.20 Deep infiltrating endometriosis of the bladder can be identified at the time of cystoscopy, which can assist in determining the need for ureteroneocystostomy if lesions are within 2 cm of the urethral opening.20 Cystoscopy also allows for biopsy to be performed if underlying malignancy is of concern.19

In our group, when bladder endometriosis is suspected, we routinely perform preoperative bladder ultrasonography to identify the lesion and plan to perform intraoperative cystoscopy at the time of laparoscopic resection.19,21

Continue to: Treatment...

Treatment

Medical management

Empiric medical therapies for endometriosis are centered around the idea that ectopic endometrial tissue responds to treatment in a similar manner as normal eutopic endometrium. The goals of treatment are to reduce or eliminate cyclic menstruation, thereby decreasing peritoneal seeding and suppressing the growth and activity of established ectopic implants. Medical therapy commonly involves the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists, danazol, combined oral contraceptives, progestins, and aromatase inhibitors.

Medical therapy is commonly employed for patients with mild or early-stage disease and in those who are poor surgical candidates or decline surgery. Medical management alone clearly is contraindicated in the setting of ureteral obstruction and—in our opinion—may not be a good option for those with endometriosis of the ureter, given the potential for recurrence and potential serious sequelae of reduced renal function.22 Therefore, surgery has become the standard approach to therapy for mild to moderate cases of ureteral endometriosis.3

Medical therapy for patients with endometriosis of the bladder is generally considered a temporary solution as hormonal suppression, with its associated adverse effects, must be maintained throughout menopause. However, if endometriosis lesions lie within close proximity to the trigone, medical management is preferred, as surgical excision in the area of the trigone may predispose patients to neurogenic bladder and retrograde bladder reflux.23,24

Surgical management

The objectives of surgical treatment for genitourinary tract endometriosis are to excise all visible disease, to prevent or delay recurrence of the disease to the extent possible, and to avoid any further morbidity—in particular, to preserve renal function in cases of ureteral endometriosis—and to avoid iatrogenic injury to surrounding pelvic nervous structures25-27 (FIGURE 2). The surgical approach depends on the technical expertise of the surgeon and the availability of necessary instrumentation. In our experience, laparoscopy with or without robotic assistance is the preferred surgical approach.3,4,6,11,28-32

Others have reported on the benefits of laparoscopy over laparotomy for the surgical management of genitourinary endometriosis. In a review of 61 patients who underwent either robot-assisted laparoscopic (n = 25) or open (n = 41) ureteroneocystostomy (n = 41), Isac and colleagues reported the procedure was longer in the laparoscopic group (279 min vs 200 min, P<.001), but the laparoscopic group had a shorter hospital stay (3 days vs 5 days, P<.001), used fewer narcotics postoperatively (P<.001), and had lower intraoperative blood loss (100 mL vs 150 mL, P<.001).32 No differences in long-term outcomes were observed in either cohort.

In a systematic review of 700 patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for ureteral endometriosis, Cavaco-Gomes and colleagues reported that conversion to laparotomy occurred in only 3% to 7% of cases.10 In instances of ureteral endometriosis, laparoscopy provides greater visualization of the intraperitoneal contents over laparotomy, enabling better evaluation and treatment of lesions.3,29,33,34 Robot-assisted laparoscopy provides the additional advantages of 3D visualization, potential for an accelerated learning curve over traditional laparoscopy, improvement in dissection technique, and ease of suturing technique.6,35,36

Continue to: Extrinsic disease...

Extrinsic disease. In our group, we perform ureterolysis for extrinsic disease.25 The peritoneal incision is made in an area unaffected by endometriosis. Using the suction irrigator, a potential space is developed under the serosa of the ureter by injecting normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution. By creating a fluid barrier between the serosa and underlying tissues, the depth of surgical incision and lateral thermal spread are minimized. Grasping forceps are used to peel the peritoneum away.25,37,38

Intrinsic disease. Unlike extrinsic disease, intrinsic disease can infiltrate the muscularis, lamina propria, and ureteral lumen, resulting in proximal dilation of the ureter with strictures.8 In this situation, ureteral compromise is likely and resection of the ureter is indicated3,28 (FIGURE 3). Intrinsic disease can be suggested by preoperative imaging or when there is evidence of deep infiltrating disease on physical exam, such as rectovaginal nodularity.30,39 When intrinsic ureteral disease is known, consultation with a urologist to plan a joint procedure is advisable. The procedure chosen to re-establish a functional ureter following resection depends on the location and extent of the involved ureter. Resection in close proximity to the bladder may be repaired by ureteroneocystostomy with or without psoas hitch,30,39,40 whereas resection of more proximal ureter may be repaired using Boari flap, ileal interposition, or autotransplantation. Lesions in the upper third or middle ureter may be repaired using ureterouretral anastomosis.6,7,30,41-43

Continue to: Bladder endometriosis...

Bladder endometriosis. Surgical treatment for bladder endometriosis depends on the depth of invasion and the location of the lesion (FIGURE 4). Lesions of the superficial aspect of the bladder identified at the time of laparoscopy can be treated with either excision or fulguration28,35,44 In our group, we perform excision over fulguration to remove the entire lesion and obtain a pathologic diagnosis. Deeper lesions involving the detrusor muscle are likely to be an endometrioma of the bladder. In these cases, laparoscopic excision is recommended.7 Rarely, lesions close to the interureteric ridge may require ureteroneocystostomy.19,45

In our experience, laparoscopic resection of bladder endometriomas is associated with better results in terms of symptom relief, progression of disease, and recurrence risk compared with other approaches. When performing laparoscopic excision of bladder lesions, we concomitantly evaluate the bladder lesion via cystoscopy to ensure adequate margins are obtained. Double-J stent placement is advised when lesions are within 2 cm of the urethral meatus to ensure ureteral patency during the postoperative period.45 A postoperative cystogram routinely is performed 7 to 14 days after surgery to ensure adequate repair prior to removing the urinary catheter.9,25,46,47

Postsurgical follow-up

Follow-up after treatment of genitourinary tract endometriosis should include monitoring the patient for symptoms of recurrence. Regular history and physical examination, renal function testing, and, in some instances, pelvic ultrasonography, all have a role in surveillance for recurrent ureteric disease. IVP or MRI may be warranted if a recurrence is suspected. A high index of suspicion should be maintained on the part of the clinician to avoid the devastating consequences of silent kidney loss. Patients should be counseled about the risk of disease recurrence, especially in those not undergoing postoperative hormonal suppression.

In conclusion

While endometriosis of the genitourinary tract is rare, patients can experience significant morbidity. Medical management of the disease is often limited by substantial adverse effects that limit treatment duration and is best used postoperatively after excision. An adequate physical exam and preoperative diagnostic imaging can be employed to characterize the extent of disease. When extensive disease involving the ureter is suspected, preoperative consultation with a urologist is encouraged to plan a multidisciplinary approach to surgical resection.

The ideal approach to surgery is laparoscopic resection with or without robotic assistance. Treatment of ureteral disease most commonly involves ureterolysis for cases of extrinsic disease but may require total resection of the ureter with concurrent ureteral reconstruction when disease is intrinsic to the ureter. Surgery for bladder endometriosis depends on the depth of invasion and location of the lesion. Superficial bladder lesions can be treated with fulguration or excision, while deeper lesions involving the detrusor muscle require excision. Lesions in close proximity to the interureteric ridge may require ureteroneocystostomy. Follow-up after excisional procedures involves monitoring the patient for signs and symptoms of disease recurrence, especially in cases of ureteral involvement, to avoid the devastating consequences of silent kidney loss.

The definitive cause of endometriosis remains unknown, but several prominent theories have been proposed.

Sampson's theory of retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes is the most well-known theory,1 although Schron had acknowledged a similar thought 3 centuries before.2 This theory posits that refluxed endometrial cells enter the abdominal cavity and invade the peritoneum, developing a blood supply necessary for survival and growth. Early reports supported this theory by suggesting that women with genital tract obstruction have a higher incidence of endometriosis.3,4 However, it was later confirmed that women without genital tract obstruction have a similar incidence of retrograde menstruation. In fact, up to 90% of women are found to have retrograde menstruation, but only 10% develop endometriosis. This suggests that once endometrial cells have escaped the uterine cavity, other events are necessary for endometrial cells to implant and survive.3,5 Other evidence to support the theory of retrograde menstruation is the observation that endometriosis is most commonly observed in the dependent portions of the pelvis, on the ovaries, in the anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and on the uterosacral ligament.6

The coelomic metaplasia theory holds that endometriosis results from spontaneous metaplastic change to mesothelial cells derived from the coelomic epithelium (located in the peritoneum and the pleura) upon exposure to menstrual effluent or other stimuli.7 Evidence for this theory is supported by the observation that intact endometrial cells have no access to the thoracic cavity in the absence of anatomical defect; therefore, the implantation theory cannot explain cases of pleural or pulmonary endometriosis.

Immune dysregulation also has been invoked to explain endometriosis implants both inside and outside the genitourinary tract. Studies have shown a higher incidence of endometriosis in women with other autoimmune disorders, including hypothyroidism, chronic fatigue syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren syndrome, and multiple sclerosis as well as in women with allergies, asthma, and eczema.8 In such women, dysregulation of the innate and adaptive immune system might promote the disease by inhibiting apoptosis of ectopic endometrial cells and by promoting their attachment, invasion, and proliferation into healthy peritoneum through the secretion of various growth factors and cytokines.9,10

Other possible theories that might explain the pathogenesis of endometriosis exist.11-13 While each theory has documented supporting evidence, no single theory currently accounts for all cases of endometriosis. It is likely, then, that endometriosis is a multifactorial disease with a combination of immune dysregulation, molecular abnormalities, genetic and epigenetic factors, and environmental exposures involved in its pathogenesis.

References

- Sampson J. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14:422-469.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Endometriosis: ancient disease, ancient treatments. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(6 suppl):S1-62.

- Halme J, Hammond MG, Hulka JF, et al. Retrograde menstruation in healthy women and in patients with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:151-154.

- Sanfilippo JS, Wakim NG, Schikler KN, et al. Endometriosis in association with uterine anomaly. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:39-43.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511-519.

- Vercellini P, Chapron C, Fedele L, et al. Evidence for asymmetric distribution of lower intestinal tract endometriosis. BJOG. 2004;111:1213-1217.

- Sourial S, Tempest N, Hapangama DK. Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Int J Reprod Med. 2014;2014:179515.

- Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, et al. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2715-2724.

- Lebovic DI, Mueller MD, Taylor RN. Immunobiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:1-10.

- Sidell N, Han SW, Parthasarathy S. Regulation and modulation of abnormal immune responses in endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;955: 159-173; discussion 199-200, 396-406.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. The pathogenesis of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013;252-258.

- Buka NJ. Vesical endometriosis after cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:1117-1118.

- Price DT, Maloney KE, Ibrahim GK, et al. Vesical endometriosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Urology. 1996;48:639-643.

- Veeraswamy A, Lewis M, Mann A, et al. Extragenital endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:449-466.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison GP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1986;45:778-783.

- Bosev D, Nicoll LM, Bhagan L, et al. Laparoscopic management of ureteral endometriosis: the Stanford University hospital experience with 96 consecutive cases. J Urol. 2009;182:2748-2752.

- Nezhat C, Falik R, McKinney S, et al. Pathophysiology and management of urinary tract endometriosis. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:359-372.

- Shook TE, Nyberg LM. Endometriosis of the urinary tract. Urology. 1988;31:1-6.

- Nezhat C, Modest AM, King LP. The role of the robot in treating urinary tract endometriosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:308-311.

- Comiter CV. Endometriosis of the urinary tract. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:625-635.

- Gustilo-Ashby AM, Paraiso MF. Treatment of urinary tract endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:559-565.

- Berlanda N, Somigliana E, Frattaruolo MP, et al. Surgery versus hormonal therapy for deep endometriosis: is it a choice of the physician? Eur J Obstet Gyneocol Reprod Biol. 2017;209:67-71.

- Cavaco-Gomes J, Martinho M, Gilabert-Aguilar J, et al. Laparoscopic management of ureteral endometriosis: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:94-101.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Green B. Laparoscopic treatment of obstructed ureter due to endometriosis by resection and ureteroureterostomy: a case report. J Urol. 1992;148:865-868.

- Nezhat C, Paka C, Gomaa M, et al. Silent loss of kidney secondary to ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2012;16:451-455.

- Iosca S, Lumia D, Bracchi E, et al. Multislice computed tomography with colon water distention (MSCT-c) in the study of intestinal and ureteral endometriosis. Clin Imaging. 2013;37(6):1061-1068.

- Medeiros LR, Rosa MI, Silva BR, et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance in deeply infiltrating endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291:611-621.

- Pateman K, Mavrelos D, Hoo WL, et al. Visualization of ureters on standard gynecological transvaginal scan: a feasibility study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:696-701.

- Guerriero S, Condous G, van den Bosch T, et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48:318-332.

- Sillou S, Poirée S, Millischer AE, et al. Urinary endometriosis: MR imaging appearance with surgical and histological correlations. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:373-381.

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, et al. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591.

- Nezhat CH, Malik S, Osias J, et al. Laparoscopic management of 15 patients with infiltrating endometriosis of the bladder and a case of primary intravesical endometrioid adenosarcoma. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:872-875.

- Kolodziej A, Krajewski W, Dolowy L, et al. Urinary tract endometriosis. Urol J. 2015;12:2213-2217.

- Nezhat C, Buescher E, Paka C, et al. Video-assisted laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013;265.

- Al-Fozan H, Tulandi T. Left lateral predisposition of endometriosis and endometrioma. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:164-166.

- Hastings JC, Van Winkle W, Barker E, et al. The effect of suture materials on healing wounds of the bladder. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:933-937.

- Cornell KK. Cystotomy, partial cystectomy, and tube cystostomy. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2000;15:11-16.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Uccella S, Cromi A, Casarin J, et al. Laparoscopy for ureteral endometriosis: surgical details, long-term follow-up, and fertility outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:160-166.e2.

- Knabben L, Imboden S, Fellmann B, et al. Urinary tract endometriosis in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis: prevalence, symptoms, management, and proposal for a new clinical classification. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:147-152.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, et al. Urinary tract endometriosis treated by laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:920-924.

- Nezhat CH, Nezhat F, Seidman D, et al. Laparoscopic ureteroureterostomy: a prospective follow-up of 9 patients. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 1998;5:200.

- Nezhat CH, Bracale U, Scala A, et al. Laparoscopic ureteroneocystostomy and vesicopsoas hitch for infiltrative endometriosis. JSLS. 2004;8:3-7.

- Nezhat C, Lewis M, Kotikela S, et al. Robotic versus standard laparoscopy for the treatment of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2758-2760.

- Isac W, Kaouk J, Altunrende F, et al. Robotic-assisted ureteroneocytostomy: techniques and comparative outcomes. J Endourol. 2013;27:318-323.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F. Laparoscopic repair of ureter resected during operative laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80(3 pt 2):543-544.

- De Cicco C, Ussia A, Koninckx PR. Laparoscopic ureteral repair in gynaecological surgery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23:296-300.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic treatment of bowel, bladder, and ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2011;15:387-392.

- Fadhlaoui A, Gillon T, Lebbi I, et al. Endometriosis and vesico-sphincteral disorders. Front Surg. 2015;2:23.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat FR. Safe laser endoscopic excision or vaporization of peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1989;52:149-151.

- Nezhat C, Winer W, Nezhat FA. Comparison of the CO2, argon, and KTP/532 lasers in the videolaseroscopic treatment of endometriosis. J Gynecol Surg. 2009;41-47.

- Azioni G, Bracale U, Scala A, et al. Laparoscopic ureteroneocytostomy and vesicopsoas hitch for infiltrative ureteral endometriosis. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2010;19:292-297.

- Stepniewska A, Grosso G, Molon A, et al. Ureteral endometriosis: clinical and radiological follow-up after laparoscopic ureterocystoneostomy. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:112-116.

- Nezhat CH, Nezhat FR, Freiha F, et al. Laparoscopic vesicopsoas hitch for infiltrative ureteral endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:376-379.

- Scioscia M, Molon A, Grosso G, et al. Laparoscopic management of ureteral endometriosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21:325-328.

- Antonelli A. Urinary tract endometriosis. Urologia. 2012;79:167-170.

- Camanni M, Bonino L, Delpiano EM, et al. Laparoscopic conservative management of ureteral endometriosis: a survey of eighty patients submitted to ureterolysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:109.

- Chapron C, Bourret A, Chopin N, et al. Surgery for bladder endometriosis: long-term results and concomitant management of associated posterior deep lesions. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:884-889.

- Nezhat CR, Nezhat FR. Laparoscopic segmental bladder resection for endometriosis: a report of two cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81(5 pt 2):882-884.

- Bourdel N, Cognet S, Canis M, et al. Laparoscopic ureteroneocystostomy: be prepared! J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:827-833.

- Page B. Camran Nezhat and the Advent of Advanced Operative Video-laparoscopy. In: Nezhat C, ed. Nezhat's History of Endoscopy. Tuttlingen, Germany: Endo Press; 2011:159-187.

- Podratz K. Degrees of Freedom: Advances in Gynecological and Obstetrical Surgery. Remembering Milestones and Achievements in Surgery: Inspiring Quality for a Hundred Years 1913-2012. Published by American College of Surgeons 2012. Tampa, FL: Faircount Media Group; 2013.

- Kelley WE. The evolution of laparoscopy and the revolution in surgery in the decade of the 1990s. JSLS: J Soc Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2008;12:351-357.

- Veeraswamy A, Lewis M, Mann A, et al. Extragenital endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:449-466.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison GP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1986;45:778-783.

- Bosev D, Nicoll LM, Bhagan L, et al. Laparoscopic management of ureteral endometriosis: the Stanford University hospital experience with 96 consecutive cases. J Urol. 2009;182:2748-2752.

- Nezhat C, Falik R, McKinney S, et al. Pathophysiology and management of urinary tract endometriosis. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:359-372.

- Shook TE, Nyberg LM. Endometriosis of the urinary tract. Urology. 1988;31:1-6.

- Nezhat C, Modest AM, King LP. The role of the robot in treating urinary tract endometriosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:308-311.

- Comiter CV. Endometriosis of the urinary tract. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:625-635.

- Gustilo-Ashby AM, Paraiso MF. Treatment of urinary tract endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:559-565.

- Berlanda N, Somigliana E, Frattaruolo MP, et al. Surgery versus hormonal therapy for deep endometriosis: is it a choice of the physician? Eur J Obstet Gyneocol Reprod Biol. 2017;209:67-71.

- Cavaco-Gomes J, Martinho M, Gilabert-Aguilar J, et al. Laparoscopic management of ureteral endometriosis: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:94-101.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Green B. Laparoscopic treatment of obstructed ureter due to endometriosis by resection and ureteroureterostomy: a case report. J Urol. 1992;148:865-868.

- Nezhat C, Paka C, Gomaa M, et al. Silent loss of kidney secondary to ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2012;16:451-455.

- Iosca S, Lumia D, Bracchi E, et al. Multislice computed tomography with colon water distention (MSCT-c) in the study of intestinal and ureteral endometriosis. Clin Imaging. 2013;37(6):1061-1068.

- Medeiros LR, Rosa MI, Silva BR, et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance in deeply infiltrating endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291:611-621.

- Pateman K, Mavrelos D, Hoo WL, et al. Visualization of ureters on standard gynecological transvaginal scan: a feasibility study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:696-701.

- Guerriero S, Condous G, van den Bosch T, et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48:318-332.

- Sillou S, Poirée S, Millischer AE, et al. Urinary endometriosis: MR imaging appearance with surgical and histological correlations. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:373-381.

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, et al. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591.

- Nezhat CH, Malik S, Osias J, et al. Laparoscopic management of 15 patients with infiltrating endometriosis of the bladder and a case of primary intravesical endometrioid adenosarcoma. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:872-875.

- Kolodziej A, Krajewski W, Dolowy L, et al. Urinary tract endometriosis. Urol J. 2015;12:2213-2217.

- Nezhat C, Buescher E, Paka C, et al. Video-assisted laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013;265.

- Al-Fozan H, Tulandi T. Left lateral predisposition of endometriosis and endometrioma. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:164-166.

- Hastings JC, Van Winkle W, Barker E, et al. The effect of suture materials on healing wounds of the bladder. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:933-937.

- Cornell KK. Cystotomy, partial cystectomy, and tube cystostomy. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2000;15:11-16.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Uccella S, Cromi A, Casarin J, et al. Laparoscopy for ureteral endometriosis: surgical details, long-term follow-up, and fertility outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:160-166.e2.

- Knabben L, Imboden S, Fellmann B, et al. Urinary tract endometriosis in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis: prevalence, symptoms, management, and proposal for a new clinical classification. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:147-152.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, et al. Urinary tract endometriosis treated by laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:920-924.

- Nezhat CH, Nezhat F, Seidman D, et al. Laparoscopic ureteroureterostomy: a prospective follow-up of 9 patients. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 1998;5:200.

- Nezhat CH, Bracale U, Scala A, et al. Laparoscopic ureteroneocystostomy and vesicopsoas hitch for infiltrative endometriosis. JSLS. 2004;8:3-7.