User login

Cancer screening is an important example of secondary prevention—the aim being to detect disease at an early stage, when treatment can prevent symptomatic disease. Over the years, screening tests for breast cancer, colorectal cancer (CRC), cervical cancer, and, most recently, lung cancer have been developed and recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Among breast cancer, cervical cancer, and CRC, the screening rate for CRC remains lowest, at 58.6%.1

The importance of screening for CRC is highlighted by the facts that:

- CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed form of cancer in the United States among both men and women

- CRC is the second leading cause of cancer-related death.2

The overall decrease in the incidence of CRC in the United States has been credited to improvements in screening and removal of potentially precancerous lesions.3

Harmful disparity puts the mentally ill at exceptional risk

Screening patterns for CRC among patients with mental illness are poorly characterized, but it is known that the overall cancer screening rate among patients with severe psychiatric illness lags significantly behind the rate in the general population.4,5 In addition, studies have shown that mortality among patients with CRC who have a mental disorder is elevated, compared with CRC patients who do not have a psychiatric diagnosis.6

Why this disparity? It might be that CRC is more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage among these patients, or that they are less likely to receive cancer treatment after diagnosis, or are more likely to have a longer delay between diagnosis and initial treatment than patients who do not have a psychiatric diagnosis.7

Regardless, psychiatric practitioners can make a significant impact on reducing this health disparity by leveraging their unique therapeutic relationship to educate patients about screening options and dispel myths about cancer screening. In this article, we outline practical strategies for CRC screening and weigh the advantages and disadvantages for the use of several tools and guidelines in psychiatric patients.

What is the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer?

Most cases of CRC evolve from polyps, abnormal growths on the lining of the colon or rectum. Constituting an estimated 96% of all polyps, adenomas are by far the most common form in the colon and rectum.

Adenomas also are most likely to transform over time to dysplasia, and then to progress to cancer.8 Although all adenomas have malignant potential, <10% evolve to adenocarcinoma. This proposed adenoma➝carcinoma sequence is not well understood; however, it is known that CRC usually develops slowly—over 10 to 15 years.9 Detection and removal of adenomas and treatable, localized carcinomas form the basis of screening for CRC.

Risk factors for colorectal cancer

A number of risk factors for CRC have been identified.

Specific heritable conditions, such as Lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis, pose the greatest risk of CRC, particularly at younger ages and compared with people without such a history.10

Family history. One of the strongest risk factors for CRC remains a family history of the disease. People who have a first-degree relative with a diagnosis of CRC are at 2 to 3 times the risk of CRC, compared with people without a family history of the disease. This risk increases further if multiple family members are affected or if the diagnosis was made in a relative at a young age.11,12

Other non-modifiable risk factors include a personal history of inflammatory bowel disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, male sex, African American heritage, and increasing age.13-15

Common modifiable risk factors include obesity, smoking, and alcohol consumption.16-18

What is the role of screening?

CRC screening is only appropriate for patients who are asymptomatic. CRC generally is asymptomatic in early stages. Prognosis also is most favorable when CRC is detected in the asymptomatic stage.

As lesions of CRC grow, the presentation might include hematochezia, melena, abdominal pain, weight loss, occult anemia, constipation or diarrhea, and changes in stool caliber.19 These signs and symptoms are not highly specific for CRC, however, and might be indicative of other gastrointestinal pathology, including inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, irritable bowel syndrome, infectious colitis, hemorrhoids, and mesenteric ischemia.

Symptomatic patients should be referred directly for diagnostic evaluation. Colonoscopy with biopsy is the standard for diagnosing CRC. Once a diagnosis of CRC is made, patients should be referred to a specialist to discuss treatment; options largely depend on the stage of the cancer at diagnosis.

What screening tests are available?

Unlike screening for other cancers, there are a number of reasonable options for CRC screening; Table 115 compares their relative pros and cons. Each test has its benefits and drawbacks, allowing the screening strategy to be customized based on patient preference and characteristics, but this variability also can lead to confusion by patient and provider about those options.

Stool-based tests detect trace amounts of blood from early-stage treatable cancers. Highly sensitive fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) has been shown specifically to decrease mortality from CRC.20 Stool-based tests are inexpensive and noninvasive, but require:

- more frequent testing

- that the patient collect the stool specimen

- follow-up colonoscopy when test results are positive.

Endoscopic and imaging tests detect polyps and early-stage treatable cancers; all require some degree of bowel preparation, and some require sedation. Testing intervals vary but, as a group, are longer than the interval between stool-based tests because polyps grow slowly. Because colonoscopy with biopsy is the preferred screening method for diagnosing CRC, it is the only screening option that also is a diagnostic procedure.

Where can screening guidelines be found?

Several professional organizations have developed guidelines for CRC screening. The 2 major

An update to both guidelines was released in 2008. Table 221,22 summarizes their recommendations.

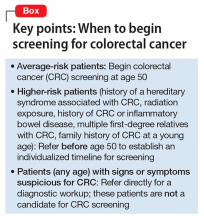

Both guidelines recommend that screening begin at age 50 (Box). The primary differences between the 2 guidelines lie in the scope of recommended options for screening and the time frame for discontinuing screening:

- USPSTF requires a higher level of evidence for screening options and limits recommended options to FOBT, sigmoidoscopy combined with FOBT, and colonoscopy.

- ACS-MSTF-ACR emphasizes options that detect premalignant polyps, and generally is more inclusive of testing options; it also delineates tests as useful for either (1) early detection of cancer (stool-based studies) or (2) cancer prevention (endoscopic and imaging tests).

On the question of when to stop screening, ACS-MSTF-ACR bases its recommendations on life expectancy; USPSTF sets a specific age for ending screening.21,22

Recommendations of a third entity, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), are similar to those of ACS-MSTF-ACR; however, ACG (1) recommends beginning screening African American patients at age 45 because of their increased risk of CRC and (2) gives preference to colonoscopy as the preferred screening modality.23

Guidelines vary for high-risk patients (those with a history of familial adenomatous polyposis or another inherited syndrome associated with CRC; those with a family history of CRC in the young; those with a history of radiation exposure, history of CRC, or inflammatory bowel disease; and those with several first-degree relatives with CRC). Patients who fall into any of these categories should be referred for specialty care to establish the time of initial screening and the interval of subsequent screening.

CRC screening in the presence of psychiatric illness

Psychiatrists have an opportunity to support their patients when considering potentially confusing CRC screening recommendations. This opportunity might occur during a discussion about general preventive care, or a patient might come to an appointment after visiting a primary care provider, and ask for advice about screening options.

The potential benefits of CRC screening are negated if a patient is unable or unwilling to complete the test or undergo timely follow-up of positive results. It is important, therefore, to individualize screening recommendations—keeping in mind the degree of impairment from mental illness and the patient’s preferences and reliability to engage in follow-up. To date, there are no agreed-on screening guidelines specifically for patients with comorbid mental illness.

Adapting USPSTF guidelines for CRC screening of average-risk patients with mental illness, we offer the following recommendations:

Recommend screening. Begin routine screening at age 50. Patients with well-controlled or mild symptoms should be screened with a stool study with or without flexible sigmoidoscopy. Stool studies are safe, noninvasive, and require no bowel preparation; when used alone, however, they need to be performed yearly.

Screening accuracy is increased when a stool-based test is combined with flexible sigmoidoscopy; screening then can be performed less often. Unlike colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy does not involve sedation; a high-functioning patient might find this appealing and tolerate the greater frequency of screening. On the other hand, some patients might not accept the inconvenience of collecting the stool sample with the kit provided and returning it to the lab for processing.

Manage psychiatric illness optimally. For a patient with moderate or severe psychiatric symptoms, first attempt to optimize treatment of the underlying psychiatric condition before establishing a CRC screening program. If control of symptoms is likely to improve over the next 1 or 2 visits, it might be reasonable to defer screening until symptoms are better controlled and then reassess the patient before making specific screening recommendations. Screening should not be delayed, however, if significant improvement in symptoms is not expected in the near future. Lengthy delay might lead to failure in initiating screening at all.

We recommend that patients with persistent moderate or severe symptoms be screened with traditional colonoscopy. The sedation associated with colonoscopy (1) may be preferable to some patients with more severe illness and (2) allows for screening and diagnostic biopsy if needed during the same procedure. Screening with colonoscopy also:

- avoids the yearly adherence to a screening program that is needed with stool cards alone

- does not rely on patients collecting and returning stool kits for processing.

A potential challenge for patients with limited social support is the requirement to have someone accompany the patient on the day of colonoscopy.

Take steps to improve the screening rate. In addition to specific recommendations based on symptom severity, there are systems-level interventions that should be considered to improve the screening rate. These include:

- addressing transportation issues that are a barrier to screening

- considering the use of health navigators or peer advocates to help guide patients through the sometimes complex systems of care.

A more comprehensive systems-level intervention for mental health clinics that work primarily with persistent and severe mentally ill populations might include employing a care coordinator to organize referrals to primary care or even exploring reverse integration. In reverse integration, primary care providers co-locate within the mental health clinic, (1) allowing for “one-stop shopping” of mental health and primary care needs and (2) facilitating collaboration and shared treatment planning between primary care and mental health for complex patients.

2. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11-30.

3. Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116(3):544-573.

4. Miller E, Lasser KE, Becker AE. Breast and cervical cancer screening for women with mental illness: patient and provider perspectives on improving linkages between primary care and mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(5):189-197.

5. Howard LM, Barley EA, Davies E, et al. Cancer diagnosis in people with severe mental illness: practical and ethical issues. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(8):797-804.

6. Baillargeon J, Kuo YF, Lin YL, et al. Effect of mental disorders on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older adults with colon cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(7):1268-1273.

7. Robertson R, Campbell NC, Smith S, et al. Factors influencing time from presentation to treatment of colorectal and breast cancer in urban and rural areas. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(8):1479-1485.

8. Stewart SL, Wike JM, Kato I, et al. A population-based study of colorectal cancer histology in the United States, 1998-2001. Cancer. 2006;107(suppl 5):1128-1141.

9. Levine JS, Ahnen DJ. Clinical practice. Adenomatous polyps of the colon. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2551-2557.

10. Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(10):919-932.

11. Butterworth AS, Higgins JP, Pharoah P. Relative and absolute risk of colorectal cancer for individuals with a family history: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(2):216-227.

12. Johns LE, Houlston RS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2992-3003.

13. Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, et al. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(18):1228-1233.

14. Yang YX, Hennessy S, Lewis JD. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(6):587-594.

15. American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts & figures 2011-2013. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-028323.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed July 5, 2016.

16. Botteri E, Iodice S, Bagnardi V, et al. Smoking and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(23):2765-2778.

17. Cho E, Smith-Warner SA, Ritz J, et al. Alcohol intake and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 8 cohort studies. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(8):603-613.

18. Larsson SC, Wolk A. Obesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(3):556-565.

19. Speights VO, Johnston MW, Stoltenberg PH, et al. Colorectal cancer: current trends in initial clinical manifestations. South Med J. 1991;84(5):575-578.

20. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106-1114.

21. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627-637.

22. Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al; American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Advisory Group; US Multi-Society Task Force; American College of Radiology Colon Cancer Committee. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(3):130-160.

23. Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines for Colorectal Cancer Screening 2009 [corrected] [Erratum in: Am J Gastroenetrol. 2009;104(6):1613]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):739-750.

Cancer screening is an important example of secondary prevention—the aim being to detect disease at an early stage, when treatment can prevent symptomatic disease. Over the years, screening tests for breast cancer, colorectal cancer (CRC), cervical cancer, and, most recently, lung cancer have been developed and recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Among breast cancer, cervical cancer, and CRC, the screening rate for CRC remains lowest, at 58.6%.1

The importance of screening for CRC is highlighted by the facts that:

- CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed form of cancer in the United States among both men and women

- CRC is the second leading cause of cancer-related death.2

The overall decrease in the incidence of CRC in the United States has been credited to improvements in screening and removal of potentially precancerous lesions.3

Harmful disparity puts the mentally ill at exceptional risk

Screening patterns for CRC among patients with mental illness are poorly characterized, but it is known that the overall cancer screening rate among patients with severe psychiatric illness lags significantly behind the rate in the general population.4,5 In addition, studies have shown that mortality among patients with CRC who have a mental disorder is elevated, compared with CRC patients who do not have a psychiatric diagnosis.6

Why this disparity? It might be that CRC is more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage among these patients, or that they are less likely to receive cancer treatment after diagnosis, or are more likely to have a longer delay between diagnosis and initial treatment than patients who do not have a psychiatric diagnosis.7

Regardless, psychiatric practitioners can make a significant impact on reducing this health disparity by leveraging their unique therapeutic relationship to educate patients about screening options and dispel myths about cancer screening. In this article, we outline practical strategies for CRC screening and weigh the advantages and disadvantages for the use of several tools and guidelines in psychiatric patients.

What is the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer?

Most cases of CRC evolve from polyps, abnormal growths on the lining of the colon or rectum. Constituting an estimated 96% of all polyps, adenomas are by far the most common form in the colon and rectum.

Adenomas also are most likely to transform over time to dysplasia, and then to progress to cancer.8 Although all adenomas have malignant potential, <10% evolve to adenocarcinoma. This proposed adenoma➝carcinoma sequence is not well understood; however, it is known that CRC usually develops slowly—over 10 to 15 years.9 Detection and removal of adenomas and treatable, localized carcinomas form the basis of screening for CRC.

Risk factors for colorectal cancer

A number of risk factors for CRC have been identified.

Specific heritable conditions, such as Lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis, pose the greatest risk of CRC, particularly at younger ages and compared with people without such a history.10

Family history. One of the strongest risk factors for CRC remains a family history of the disease. People who have a first-degree relative with a diagnosis of CRC are at 2 to 3 times the risk of CRC, compared with people without a family history of the disease. This risk increases further if multiple family members are affected or if the diagnosis was made in a relative at a young age.11,12

Other non-modifiable risk factors include a personal history of inflammatory bowel disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, male sex, African American heritage, and increasing age.13-15

Common modifiable risk factors include obesity, smoking, and alcohol consumption.16-18

What is the role of screening?

CRC screening is only appropriate for patients who are asymptomatic. CRC generally is asymptomatic in early stages. Prognosis also is most favorable when CRC is detected in the asymptomatic stage.

As lesions of CRC grow, the presentation might include hematochezia, melena, abdominal pain, weight loss, occult anemia, constipation or diarrhea, and changes in stool caliber.19 These signs and symptoms are not highly specific for CRC, however, and might be indicative of other gastrointestinal pathology, including inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, irritable bowel syndrome, infectious colitis, hemorrhoids, and mesenteric ischemia.

Symptomatic patients should be referred directly for diagnostic evaluation. Colonoscopy with biopsy is the standard for diagnosing CRC. Once a diagnosis of CRC is made, patients should be referred to a specialist to discuss treatment; options largely depend on the stage of the cancer at diagnosis.

What screening tests are available?

Unlike screening for other cancers, there are a number of reasonable options for CRC screening; Table 115 compares their relative pros and cons. Each test has its benefits and drawbacks, allowing the screening strategy to be customized based on patient preference and characteristics, but this variability also can lead to confusion by patient and provider about those options.

Stool-based tests detect trace amounts of blood from early-stage treatable cancers. Highly sensitive fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) has been shown specifically to decrease mortality from CRC.20 Stool-based tests are inexpensive and noninvasive, but require:

- more frequent testing

- that the patient collect the stool specimen

- follow-up colonoscopy when test results are positive.

Endoscopic and imaging tests detect polyps and early-stage treatable cancers; all require some degree of bowel preparation, and some require sedation. Testing intervals vary but, as a group, are longer than the interval between stool-based tests because polyps grow slowly. Because colonoscopy with biopsy is the preferred screening method for diagnosing CRC, it is the only screening option that also is a diagnostic procedure.

Where can screening guidelines be found?

Several professional organizations have developed guidelines for CRC screening. The 2 major

An update to both guidelines was released in 2008. Table 221,22 summarizes their recommendations.

Both guidelines recommend that screening begin at age 50 (Box). The primary differences between the 2 guidelines lie in the scope of recommended options for screening and the time frame for discontinuing screening:

- USPSTF requires a higher level of evidence for screening options and limits recommended options to FOBT, sigmoidoscopy combined with FOBT, and colonoscopy.

- ACS-MSTF-ACR emphasizes options that detect premalignant polyps, and generally is more inclusive of testing options; it also delineates tests as useful for either (1) early detection of cancer (stool-based studies) or (2) cancer prevention (endoscopic and imaging tests).

On the question of when to stop screening, ACS-MSTF-ACR bases its recommendations on life expectancy; USPSTF sets a specific age for ending screening.21,22

Recommendations of a third entity, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), are similar to those of ACS-MSTF-ACR; however, ACG (1) recommends beginning screening African American patients at age 45 because of their increased risk of CRC and (2) gives preference to colonoscopy as the preferred screening modality.23

Guidelines vary for high-risk patients (those with a history of familial adenomatous polyposis or another inherited syndrome associated with CRC; those with a family history of CRC in the young; those with a history of radiation exposure, history of CRC, or inflammatory bowel disease; and those with several first-degree relatives with CRC). Patients who fall into any of these categories should be referred for specialty care to establish the time of initial screening and the interval of subsequent screening.

CRC screening in the presence of psychiatric illness

Psychiatrists have an opportunity to support their patients when considering potentially confusing CRC screening recommendations. This opportunity might occur during a discussion about general preventive care, or a patient might come to an appointment after visiting a primary care provider, and ask for advice about screening options.

The potential benefits of CRC screening are negated if a patient is unable or unwilling to complete the test or undergo timely follow-up of positive results. It is important, therefore, to individualize screening recommendations—keeping in mind the degree of impairment from mental illness and the patient’s preferences and reliability to engage in follow-up. To date, there are no agreed-on screening guidelines specifically for patients with comorbid mental illness.

Adapting USPSTF guidelines for CRC screening of average-risk patients with mental illness, we offer the following recommendations:

Recommend screening. Begin routine screening at age 50. Patients with well-controlled or mild symptoms should be screened with a stool study with or without flexible sigmoidoscopy. Stool studies are safe, noninvasive, and require no bowel preparation; when used alone, however, they need to be performed yearly.

Screening accuracy is increased when a stool-based test is combined with flexible sigmoidoscopy; screening then can be performed less often. Unlike colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy does not involve sedation; a high-functioning patient might find this appealing and tolerate the greater frequency of screening. On the other hand, some patients might not accept the inconvenience of collecting the stool sample with the kit provided and returning it to the lab for processing.

Manage psychiatric illness optimally. For a patient with moderate or severe psychiatric symptoms, first attempt to optimize treatment of the underlying psychiatric condition before establishing a CRC screening program. If control of symptoms is likely to improve over the next 1 or 2 visits, it might be reasonable to defer screening until symptoms are better controlled and then reassess the patient before making specific screening recommendations. Screening should not be delayed, however, if significant improvement in symptoms is not expected in the near future. Lengthy delay might lead to failure in initiating screening at all.

We recommend that patients with persistent moderate or severe symptoms be screened with traditional colonoscopy. The sedation associated with colonoscopy (1) may be preferable to some patients with more severe illness and (2) allows for screening and diagnostic biopsy if needed during the same procedure. Screening with colonoscopy also:

- avoids the yearly adherence to a screening program that is needed with stool cards alone

- does not rely on patients collecting and returning stool kits for processing.

A potential challenge for patients with limited social support is the requirement to have someone accompany the patient on the day of colonoscopy.

Take steps to improve the screening rate. In addition to specific recommendations based on symptom severity, there are systems-level interventions that should be considered to improve the screening rate. These include:

- addressing transportation issues that are a barrier to screening

- considering the use of health navigators or peer advocates to help guide patients through the sometimes complex systems of care.

A more comprehensive systems-level intervention for mental health clinics that work primarily with persistent and severe mentally ill populations might include employing a care coordinator to organize referrals to primary care or even exploring reverse integration. In reverse integration, primary care providers co-locate within the mental health clinic, (1) allowing for “one-stop shopping” of mental health and primary care needs and (2) facilitating collaboration and shared treatment planning between primary care and mental health for complex patients.

Cancer screening is an important example of secondary prevention—the aim being to detect disease at an early stage, when treatment can prevent symptomatic disease. Over the years, screening tests for breast cancer, colorectal cancer (CRC), cervical cancer, and, most recently, lung cancer have been developed and recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Among breast cancer, cervical cancer, and CRC, the screening rate for CRC remains lowest, at 58.6%.1

The importance of screening for CRC is highlighted by the facts that:

- CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed form of cancer in the United States among both men and women

- CRC is the second leading cause of cancer-related death.2

The overall decrease in the incidence of CRC in the United States has been credited to improvements in screening and removal of potentially precancerous lesions.3

Harmful disparity puts the mentally ill at exceptional risk

Screening patterns for CRC among patients with mental illness are poorly characterized, but it is known that the overall cancer screening rate among patients with severe psychiatric illness lags significantly behind the rate in the general population.4,5 In addition, studies have shown that mortality among patients with CRC who have a mental disorder is elevated, compared with CRC patients who do not have a psychiatric diagnosis.6

Why this disparity? It might be that CRC is more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage among these patients, or that they are less likely to receive cancer treatment after diagnosis, or are more likely to have a longer delay between diagnosis and initial treatment than patients who do not have a psychiatric diagnosis.7

Regardless, psychiatric practitioners can make a significant impact on reducing this health disparity by leveraging their unique therapeutic relationship to educate patients about screening options and dispel myths about cancer screening. In this article, we outline practical strategies for CRC screening and weigh the advantages and disadvantages for the use of several tools and guidelines in psychiatric patients.

What is the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer?

Most cases of CRC evolve from polyps, abnormal growths on the lining of the colon or rectum. Constituting an estimated 96% of all polyps, adenomas are by far the most common form in the colon and rectum.

Adenomas also are most likely to transform over time to dysplasia, and then to progress to cancer.8 Although all adenomas have malignant potential, <10% evolve to adenocarcinoma. This proposed adenoma➝carcinoma sequence is not well understood; however, it is known that CRC usually develops slowly—over 10 to 15 years.9 Detection and removal of adenomas and treatable, localized carcinomas form the basis of screening for CRC.

Risk factors for colorectal cancer

A number of risk factors for CRC have been identified.

Specific heritable conditions, such as Lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis, pose the greatest risk of CRC, particularly at younger ages and compared with people without such a history.10

Family history. One of the strongest risk factors for CRC remains a family history of the disease. People who have a first-degree relative with a diagnosis of CRC are at 2 to 3 times the risk of CRC, compared with people without a family history of the disease. This risk increases further if multiple family members are affected or if the diagnosis was made in a relative at a young age.11,12

Other non-modifiable risk factors include a personal history of inflammatory bowel disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, male sex, African American heritage, and increasing age.13-15

Common modifiable risk factors include obesity, smoking, and alcohol consumption.16-18

What is the role of screening?

CRC screening is only appropriate for patients who are asymptomatic. CRC generally is asymptomatic in early stages. Prognosis also is most favorable when CRC is detected in the asymptomatic stage.

As lesions of CRC grow, the presentation might include hematochezia, melena, abdominal pain, weight loss, occult anemia, constipation or diarrhea, and changes in stool caliber.19 These signs and symptoms are not highly specific for CRC, however, and might be indicative of other gastrointestinal pathology, including inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, irritable bowel syndrome, infectious colitis, hemorrhoids, and mesenteric ischemia.

Symptomatic patients should be referred directly for diagnostic evaluation. Colonoscopy with biopsy is the standard for diagnosing CRC. Once a diagnosis of CRC is made, patients should be referred to a specialist to discuss treatment; options largely depend on the stage of the cancer at diagnosis.

What screening tests are available?

Unlike screening for other cancers, there are a number of reasonable options for CRC screening; Table 115 compares their relative pros and cons. Each test has its benefits and drawbacks, allowing the screening strategy to be customized based on patient preference and characteristics, but this variability also can lead to confusion by patient and provider about those options.

Stool-based tests detect trace amounts of blood from early-stage treatable cancers. Highly sensitive fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) has been shown specifically to decrease mortality from CRC.20 Stool-based tests are inexpensive and noninvasive, but require:

- more frequent testing

- that the patient collect the stool specimen

- follow-up colonoscopy when test results are positive.

Endoscopic and imaging tests detect polyps and early-stage treatable cancers; all require some degree of bowel preparation, and some require sedation. Testing intervals vary but, as a group, are longer than the interval between stool-based tests because polyps grow slowly. Because colonoscopy with biopsy is the preferred screening method for diagnosing CRC, it is the only screening option that also is a diagnostic procedure.

Where can screening guidelines be found?

Several professional organizations have developed guidelines for CRC screening. The 2 major

An update to both guidelines was released in 2008. Table 221,22 summarizes their recommendations.

Both guidelines recommend that screening begin at age 50 (Box). The primary differences between the 2 guidelines lie in the scope of recommended options for screening and the time frame for discontinuing screening:

- USPSTF requires a higher level of evidence for screening options and limits recommended options to FOBT, sigmoidoscopy combined with FOBT, and colonoscopy.

- ACS-MSTF-ACR emphasizes options that detect premalignant polyps, and generally is more inclusive of testing options; it also delineates tests as useful for either (1) early detection of cancer (stool-based studies) or (2) cancer prevention (endoscopic and imaging tests).

On the question of when to stop screening, ACS-MSTF-ACR bases its recommendations on life expectancy; USPSTF sets a specific age for ending screening.21,22

Recommendations of a third entity, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), are similar to those of ACS-MSTF-ACR; however, ACG (1) recommends beginning screening African American patients at age 45 because of their increased risk of CRC and (2) gives preference to colonoscopy as the preferred screening modality.23

Guidelines vary for high-risk patients (those with a history of familial adenomatous polyposis or another inherited syndrome associated with CRC; those with a family history of CRC in the young; those with a history of radiation exposure, history of CRC, or inflammatory bowel disease; and those with several first-degree relatives with CRC). Patients who fall into any of these categories should be referred for specialty care to establish the time of initial screening and the interval of subsequent screening.

CRC screening in the presence of psychiatric illness

Psychiatrists have an opportunity to support their patients when considering potentially confusing CRC screening recommendations. This opportunity might occur during a discussion about general preventive care, or a patient might come to an appointment after visiting a primary care provider, and ask for advice about screening options.

The potential benefits of CRC screening are negated if a patient is unable or unwilling to complete the test or undergo timely follow-up of positive results. It is important, therefore, to individualize screening recommendations—keeping in mind the degree of impairment from mental illness and the patient’s preferences and reliability to engage in follow-up. To date, there are no agreed-on screening guidelines specifically for patients with comorbid mental illness.

Adapting USPSTF guidelines for CRC screening of average-risk patients with mental illness, we offer the following recommendations:

Recommend screening. Begin routine screening at age 50. Patients with well-controlled or mild symptoms should be screened with a stool study with or without flexible sigmoidoscopy. Stool studies are safe, noninvasive, and require no bowel preparation; when used alone, however, they need to be performed yearly.

Screening accuracy is increased when a stool-based test is combined with flexible sigmoidoscopy; screening then can be performed less often. Unlike colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy does not involve sedation; a high-functioning patient might find this appealing and tolerate the greater frequency of screening. On the other hand, some patients might not accept the inconvenience of collecting the stool sample with the kit provided and returning it to the lab for processing.

Manage psychiatric illness optimally. For a patient with moderate or severe psychiatric symptoms, first attempt to optimize treatment of the underlying psychiatric condition before establishing a CRC screening program. If control of symptoms is likely to improve over the next 1 or 2 visits, it might be reasonable to defer screening until symptoms are better controlled and then reassess the patient before making specific screening recommendations. Screening should not be delayed, however, if significant improvement in symptoms is not expected in the near future. Lengthy delay might lead to failure in initiating screening at all.

We recommend that patients with persistent moderate or severe symptoms be screened with traditional colonoscopy. The sedation associated with colonoscopy (1) may be preferable to some patients with more severe illness and (2) allows for screening and diagnostic biopsy if needed during the same procedure. Screening with colonoscopy also:

- avoids the yearly adherence to a screening program that is needed with stool cards alone

- does not rely on patients collecting and returning stool kits for processing.

A potential challenge for patients with limited social support is the requirement to have someone accompany the patient on the day of colonoscopy.

Take steps to improve the screening rate. In addition to specific recommendations based on symptom severity, there are systems-level interventions that should be considered to improve the screening rate. These include:

- addressing transportation issues that are a barrier to screening

- considering the use of health navigators or peer advocates to help guide patients through the sometimes complex systems of care.

A more comprehensive systems-level intervention for mental health clinics that work primarily with persistent and severe mentally ill populations might include employing a care coordinator to organize referrals to primary care or even exploring reverse integration. In reverse integration, primary care providers co-locate within the mental health clinic, (1) allowing for “one-stop shopping” of mental health and primary care needs and (2) facilitating collaboration and shared treatment planning between primary care and mental health for complex patients.

2. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11-30.

3. Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116(3):544-573.

4. Miller E, Lasser KE, Becker AE. Breast and cervical cancer screening for women with mental illness: patient and provider perspectives on improving linkages between primary care and mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(5):189-197.

5. Howard LM, Barley EA, Davies E, et al. Cancer diagnosis in people with severe mental illness: practical and ethical issues. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(8):797-804.

6. Baillargeon J, Kuo YF, Lin YL, et al. Effect of mental disorders on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older adults with colon cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(7):1268-1273.

7. Robertson R, Campbell NC, Smith S, et al. Factors influencing time from presentation to treatment of colorectal and breast cancer in urban and rural areas. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(8):1479-1485.

8. Stewart SL, Wike JM, Kato I, et al. A population-based study of colorectal cancer histology in the United States, 1998-2001. Cancer. 2006;107(suppl 5):1128-1141.

9. Levine JS, Ahnen DJ. Clinical practice. Adenomatous polyps of the colon. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2551-2557.

10. Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(10):919-932.

11. Butterworth AS, Higgins JP, Pharoah P. Relative and absolute risk of colorectal cancer for individuals with a family history: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(2):216-227.

12. Johns LE, Houlston RS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2992-3003.

13. Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, et al. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(18):1228-1233.

14. Yang YX, Hennessy S, Lewis JD. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(6):587-594.

15. American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts & figures 2011-2013. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-028323.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed July 5, 2016.

16. Botteri E, Iodice S, Bagnardi V, et al. Smoking and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(23):2765-2778.

17. Cho E, Smith-Warner SA, Ritz J, et al. Alcohol intake and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 8 cohort studies. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(8):603-613.

18. Larsson SC, Wolk A. Obesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(3):556-565.

19. Speights VO, Johnston MW, Stoltenberg PH, et al. Colorectal cancer: current trends in initial clinical manifestations. South Med J. 1991;84(5):575-578.

20. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106-1114.

21. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627-637.

22. Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al; American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Advisory Group; US Multi-Society Task Force; American College of Radiology Colon Cancer Committee. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(3):130-160.

23. Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines for Colorectal Cancer Screening 2009 [corrected] [Erratum in: Am J Gastroenetrol. 2009;104(6):1613]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):739-750.

2. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11-30.

3. Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116(3):544-573.

4. Miller E, Lasser KE, Becker AE. Breast and cervical cancer screening for women with mental illness: patient and provider perspectives on improving linkages between primary care and mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(5):189-197.

5. Howard LM, Barley EA, Davies E, et al. Cancer diagnosis in people with severe mental illness: practical and ethical issues. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(8):797-804.

6. Baillargeon J, Kuo YF, Lin YL, et al. Effect of mental disorders on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older adults with colon cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(7):1268-1273.

7. Robertson R, Campbell NC, Smith S, et al. Factors influencing time from presentation to treatment of colorectal and breast cancer in urban and rural areas. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(8):1479-1485.

8. Stewart SL, Wike JM, Kato I, et al. A population-based study of colorectal cancer histology in the United States, 1998-2001. Cancer. 2006;107(suppl 5):1128-1141.

9. Levine JS, Ahnen DJ. Clinical practice. Adenomatous polyps of the colon. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2551-2557.

10. Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(10):919-932.

11. Butterworth AS, Higgins JP, Pharoah P. Relative and absolute risk of colorectal cancer for individuals with a family history: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(2):216-227.

12. Johns LE, Houlston RS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2992-3003.

13. Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, et al. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(18):1228-1233.

14. Yang YX, Hennessy S, Lewis JD. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(6):587-594.

15. American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts & figures 2011-2013. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-028323.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed July 5, 2016.

16. Botteri E, Iodice S, Bagnardi V, et al. Smoking and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(23):2765-2778.

17. Cho E, Smith-Warner SA, Ritz J, et al. Alcohol intake and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 8 cohort studies. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(8):603-613.

18. Larsson SC, Wolk A. Obesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(3):556-565.

19. Speights VO, Johnston MW, Stoltenberg PH, et al. Colorectal cancer: current trends in initial clinical manifestations. South Med J. 1991;84(5):575-578.

20. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106-1114.

21. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627-637.

22. Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al; American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Advisory Group; US Multi-Society Task Force; American College of Radiology Colon Cancer Committee. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(3):130-160.

23. Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines for Colorectal Cancer Screening 2009 [corrected] [Erratum in: Am J Gastroenetrol. 2009;104(6):1613]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):739-750.