User login

It’s a scenario with which hospitalists are quite familiar: Mrs. A is discharged from the hospital to a skilled nursing facility on a Friday night. On Saturday, she develops a deep cough and fever, but the nursing facility’s attending physician isn’t scheduled to round until Monday. So Mrs. A ends up back in the hospital.

Such a readmission could have been prevented – and now that Medicare’s readmission penalties are about to kick in, more hospitalists are investigating systems and models to help them improve their readmission rates.

Under the Affordable Care Act, Medicare will begin on Oct. 1 to penalize hospitals with excess readmission for pneumonia, heart failure, and myocardial infarction – up to 1% of their overall Medicare payments, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently announced. The penalty for this fiscal year (Oct. 1, 2012–Sept. 30, 2013) is based on hospital performance between July 2008 and June 2011, and is adjusted per hospital based on patient demographics, comorbidities, and frailty.

So, what’s a hospitalist to do to help lower the penalty going forward?

Focus on Skilled Nursing Facilities

Readmissions such as Mrs. A’s could be prevented if physicians had a stronger presence at the skilled nursing facility (SNF) level, according to Dr. Darius K. Joshi of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

At the University of Michigan Health System, a small team of geriatricians and nurse practitioners, led by Dr. Joshi, has been assigned to staff local SNFs 7 days a week. The goal is to discharge patients from the hospital to SNFs sooner and to keep them from being readmitted.

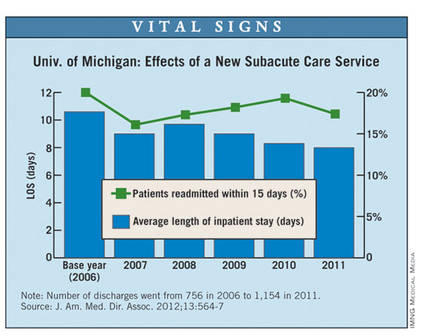

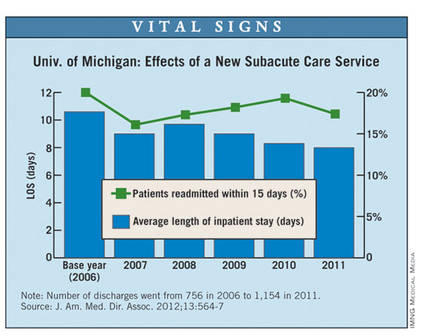

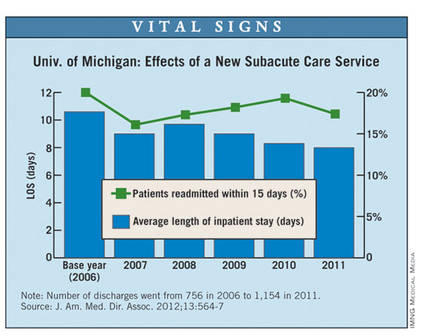

The subacute care program reduced the average hospital length of stay before transfer to an SNF from 10.6 days to 8 days between 2006 and 2011. The hospital’s 15-day readmission rates have also improved somewhat, dropping from 20% to 17% over the same period (J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012;13:564-7).

"Being at the bedside, seeing these patients, knowing their history, having good laboratory tests available, avoids sending many of these patients back to the hospital," said Dr. Joshi of the geriatric medicine division at the University of Michigan, a former hospitalist who runs the subacute program.

Doctors and nurse practitioners practicing in the SNFs also have access to the health system’s electronic health record (EHR) system. This allows physicians at the SNF to understand the patient’s hospital care; it also transfers data on care provided at the SNF back to the hospital.

But even with this effort, the University of Michigan health system (which has invested in ways to prevent bounce-back to the hospital) will face a 0.64% cut under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in FY 2013.

"[Readmissions are] a very, very resistant problem with our patients," Dr. Joshi explained.

Many times, families may insist that their loved ones go to the emergency department when their conditions worsen. In the case of falls, there is little alternative to returning to the hospital because most SNFs don’t have appropriate imaging equipment.

"There are limitations in what we can do, but if there’s any chance of cutting down readmissions, it needs to be with bedside presence," Dr. Joshi said.

Multidisciplinary Approach

At Sarasota (Fla.) Memorial Hospital, one focus in the fight to lower readmission rates is on heart failure.

The hospital established a heart failure center for ambulatory patients and instituted telemonitoring for nonambulatory patients who are discharged to home. A team of hospitalists, cardiologists, floor nurses, and home health care staff identifies high-risk heart failure patients, addresses their needs in the hospital, and arranges for follow-up care after discharge.

Sarasota Memorial Hospital is considered a standout when it comes to keeping readmission rates low. It was one of only two hospitals identified by CMS as having better-than-average readmission rates for all three assessed conditions.

The lion’s share of the credit for their success goes to the multidisciplinary culture of the health system, according to Dr. John Moritz, a hospitalist at Sarasota Memorial.

"Communication and teamwork are key," Dr. Moritz said. "Our whole culture is characterized by working with the other staff members to ensure a favorable outcome for our patients."

This fall, Sarasota Memorial will take that approach a step further. They have dedicated two hospital floors to multidisciplinary rounds, where hospitalists, case managers, social workers, heart failure nurses, and physical therapists will round as a group.

"During that visit, we’ll be able to identify what’s needed," Dr. Moritz said. "We’ll be able to clearly communicate that to the patient and to each other."

Applying Project BOOST

Sherman Health System in Elgin, Ill., also takes a multipronged, multidisciplinary approach. The hospital is one of the mentored-implementation sites for Project BOOST, a Society of Hospital Medicine initiative to improve the hospital-to-home transition while reducing readmission rates and length of stay.

At Sherman Health, nurses employ "teach back" techniques, in which they teach patients about their discharge instructions and ask them open-ended questions to make sure the patients understand.

"Patients will tell us anything to get out the door," said Kelly Tarpey, R.N., director of clinical excellence at Sherman Health. "What teach back does is make sure that the key points really are validated and understood."

After using the teach-back approach on one unit, Sherman Health saw its H-CAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) survey scores increase for patient perception of the quality of the discharge instruction, from 84% in 2011 to 92% in 2012, according to the hospital.

Through BOOST, they have also taken a more aggressive approach to postdischarge follow-up. Although the hospital staff has always called patients 24-48 hours after discharge, they are now focusing the calls on clinical concerns. Nurses have the patients’ charts in hand when they call and ask about medications and follow-up appointments. And the nurses continue to use the teach back method they employed in the hospital.

So far, the BOOST work and other care-coordination efforts seem to be paying off. In the first half of 2009, Sherman Health’s 30-day readmission rates for heart failure were 26%. But by the second half of 2011, that figure had fallen to 11%, according to the hospital.

But the improvements came too late to shield the health system from Medicare penalties that are based on performance data. Sherman Health will face a 0.61% cut to its Medicare payments starting in October.

Paying Attention to the Stick

Although hospitals are at various stages of readiness, experts say it is the penalty that has made readmissions a top priority for many hospitalist programs.

Dr. Luke Hansen of Northwestern University in Chicago and the lead analyst for Project BOOST said that there has been a steady increase in the attention that hospitals have paid to readmissions in just the last 3 years. Now when he first meets with the staff at a BOOST site, they are much more likely to have already undertaken some type of effort to reduce readmissions. They also frequently have funded positions such as a transitions nurse who can help identify patients at high risk for rehospitalization.

"Those are things that in the beginning were really uncommon," he said.

Many hospitalist programs are leading the readmission reduction efforts in their institutions, said Dr. Greg Maynard of the University of California, San Diego, and a coinvestigator for Project BOOST. Hospitalists are leading system redesigns by improving interdisciplinary rounds, setting up communication protocols, and reaching out to providers outside the hospital.

"For the first time in my memory, there’s a lot of work being done with the hospital and hospitalists’ groups working with outside groups of skilled nursing facilities, for example," Dr. Maynard said. "I am seeing an incredible amount of dynamism around better partnership, better communication, [and] better tools, and I think hospitalists are playing a big role in that."

In contrast, Dr. Maynard said that there are also hospitalist programs in which the business model allows time only for seeing patients, not for quality improvement.

"To them, it feels like something is being done to them," he said. "They may be feeling like they’re victims instead of leaders."

It’s a scenario with which hospitalists are quite familiar: Mrs. A is discharged from the hospital to a skilled nursing facility on a Friday night. On Saturday, she develops a deep cough and fever, but the nursing facility’s attending physician isn’t scheduled to round until Monday. So Mrs. A ends up back in the hospital.

Such a readmission could have been prevented – and now that Medicare’s readmission penalties are about to kick in, more hospitalists are investigating systems and models to help them improve their readmission rates.

Under the Affordable Care Act, Medicare will begin on Oct. 1 to penalize hospitals with excess readmission for pneumonia, heart failure, and myocardial infarction – up to 1% of their overall Medicare payments, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently announced. The penalty for this fiscal year (Oct. 1, 2012–Sept. 30, 2013) is based on hospital performance between July 2008 and June 2011, and is adjusted per hospital based on patient demographics, comorbidities, and frailty.

So, what’s a hospitalist to do to help lower the penalty going forward?

Focus on Skilled Nursing Facilities

Readmissions such as Mrs. A’s could be prevented if physicians had a stronger presence at the skilled nursing facility (SNF) level, according to Dr. Darius K. Joshi of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

At the University of Michigan Health System, a small team of geriatricians and nurse practitioners, led by Dr. Joshi, has been assigned to staff local SNFs 7 days a week. The goal is to discharge patients from the hospital to SNFs sooner and to keep them from being readmitted.

The subacute care program reduced the average hospital length of stay before transfer to an SNF from 10.6 days to 8 days between 2006 and 2011. The hospital’s 15-day readmission rates have also improved somewhat, dropping from 20% to 17% over the same period (J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012;13:564-7).

"Being at the bedside, seeing these patients, knowing their history, having good laboratory tests available, avoids sending many of these patients back to the hospital," said Dr. Joshi of the geriatric medicine division at the University of Michigan, a former hospitalist who runs the subacute program.

Doctors and nurse practitioners practicing in the SNFs also have access to the health system’s electronic health record (EHR) system. This allows physicians at the SNF to understand the patient’s hospital care; it also transfers data on care provided at the SNF back to the hospital.

But even with this effort, the University of Michigan health system (which has invested in ways to prevent bounce-back to the hospital) will face a 0.64% cut under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in FY 2013.

"[Readmissions are] a very, very resistant problem with our patients," Dr. Joshi explained.

Many times, families may insist that their loved ones go to the emergency department when their conditions worsen. In the case of falls, there is little alternative to returning to the hospital because most SNFs don’t have appropriate imaging equipment.

"There are limitations in what we can do, but if there’s any chance of cutting down readmissions, it needs to be with bedside presence," Dr. Joshi said.

Multidisciplinary Approach

At Sarasota (Fla.) Memorial Hospital, one focus in the fight to lower readmission rates is on heart failure.

The hospital established a heart failure center for ambulatory patients and instituted telemonitoring for nonambulatory patients who are discharged to home. A team of hospitalists, cardiologists, floor nurses, and home health care staff identifies high-risk heart failure patients, addresses their needs in the hospital, and arranges for follow-up care after discharge.

Sarasota Memorial Hospital is considered a standout when it comes to keeping readmission rates low. It was one of only two hospitals identified by CMS as having better-than-average readmission rates for all three assessed conditions.

The lion’s share of the credit for their success goes to the multidisciplinary culture of the health system, according to Dr. John Moritz, a hospitalist at Sarasota Memorial.

"Communication and teamwork are key," Dr. Moritz said. "Our whole culture is characterized by working with the other staff members to ensure a favorable outcome for our patients."

This fall, Sarasota Memorial will take that approach a step further. They have dedicated two hospital floors to multidisciplinary rounds, where hospitalists, case managers, social workers, heart failure nurses, and physical therapists will round as a group.

"During that visit, we’ll be able to identify what’s needed," Dr. Moritz said. "We’ll be able to clearly communicate that to the patient and to each other."

Applying Project BOOST

Sherman Health System in Elgin, Ill., also takes a multipronged, multidisciplinary approach. The hospital is one of the mentored-implementation sites for Project BOOST, a Society of Hospital Medicine initiative to improve the hospital-to-home transition while reducing readmission rates and length of stay.

At Sherman Health, nurses employ "teach back" techniques, in which they teach patients about their discharge instructions and ask them open-ended questions to make sure the patients understand.

"Patients will tell us anything to get out the door," said Kelly Tarpey, R.N., director of clinical excellence at Sherman Health. "What teach back does is make sure that the key points really are validated and understood."

After using the teach-back approach on one unit, Sherman Health saw its H-CAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) survey scores increase for patient perception of the quality of the discharge instruction, from 84% in 2011 to 92% in 2012, according to the hospital.

Through BOOST, they have also taken a more aggressive approach to postdischarge follow-up. Although the hospital staff has always called patients 24-48 hours after discharge, they are now focusing the calls on clinical concerns. Nurses have the patients’ charts in hand when they call and ask about medications and follow-up appointments. And the nurses continue to use the teach back method they employed in the hospital.

So far, the BOOST work and other care-coordination efforts seem to be paying off. In the first half of 2009, Sherman Health’s 30-day readmission rates for heart failure were 26%. But by the second half of 2011, that figure had fallen to 11%, according to the hospital.

But the improvements came too late to shield the health system from Medicare penalties that are based on performance data. Sherman Health will face a 0.61% cut to its Medicare payments starting in October.

Paying Attention to the Stick

Although hospitals are at various stages of readiness, experts say it is the penalty that has made readmissions a top priority for many hospitalist programs.

Dr. Luke Hansen of Northwestern University in Chicago and the lead analyst for Project BOOST said that there has been a steady increase in the attention that hospitals have paid to readmissions in just the last 3 years. Now when he first meets with the staff at a BOOST site, they are much more likely to have already undertaken some type of effort to reduce readmissions. They also frequently have funded positions such as a transitions nurse who can help identify patients at high risk for rehospitalization.

"Those are things that in the beginning were really uncommon," he said.

Many hospitalist programs are leading the readmission reduction efforts in their institutions, said Dr. Greg Maynard of the University of California, San Diego, and a coinvestigator for Project BOOST. Hospitalists are leading system redesigns by improving interdisciplinary rounds, setting up communication protocols, and reaching out to providers outside the hospital.

"For the first time in my memory, there’s a lot of work being done with the hospital and hospitalists’ groups working with outside groups of skilled nursing facilities, for example," Dr. Maynard said. "I am seeing an incredible amount of dynamism around better partnership, better communication, [and] better tools, and I think hospitalists are playing a big role in that."

In contrast, Dr. Maynard said that there are also hospitalist programs in which the business model allows time only for seeing patients, not for quality improvement.

"To them, it feels like something is being done to them," he said. "They may be feeling like they’re victims instead of leaders."

It’s a scenario with which hospitalists are quite familiar: Mrs. A is discharged from the hospital to a skilled nursing facility on a Friday night. On Saturday, she develops a deep cough and fever, but the nursing facility’s attending physician isn’t scheduled to round until Monday. So Mrs. A ends up back in the hospital.

Such a readmission could have been prevented – and now that Medicare’s readmission penalties are about to kick in, more hospitalists are investigating systems and models to help them improve their readmission rates.

Under the Affordable Care Act, Medicare will begin on Oct. 1 to penalize hospitals with excess readmission for pneumonia, heart failure, and myocardial infarction – up to 1% of their overall Medicare payments, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently announced. The penalty for this fiscal year (Oct. 1, 2012–Sept. 30, 2013) is based on hospital performance between July 2008 and June 2011, and is adjusted per hospital based on patient demographics, comorbidities, and frailty.

So, what’s a hospitalist to do to help lower the penalty going forward?

Focus on Skilled Nursing Facilities

Readmissions such as Mrs. A’s could be prevented if physicians had a stronger presence at the skilled nursing facility (SNF) level, according to Dr. Darius K. Joshi of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

At the University of Michigan Health System, a small team of geriatricians and nurse practitioners, led by Dr. Joshi, has been assigned to staff local SNFs 7 days a week. The goal is to discharge patients from the hospital to SNFs sooner and to keep them from being readmitted.

The subacute care program reduced the average hospital length of stay before transfer to an SNF from 10.6 days to 8 days between 2006 and 2011. The hospital’s 15-day readmission rates have also improved somewhat, dropping from 20% to 17% over the same period (J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012;13:564-7).

"Being at the bedside, seeing these patients, knowing their history, having good laboratory tests available, avoids sending many of these patients back to the hospital," said Dr. Joshi of the geriatric medicine division at the University of Michigan, a former hospitalist who runs the subacute program.

Doctors and nurse practitioners practicing in the SNFs also have access to the health system’s electronic health record (EHR) system. This allows physicians at the SNF to understand the patient’s hospital care; it also transfers data on care provided at the SNF back to the hospital.

But even with this effort, the University of Michigan health system (which has invested in ways to prevent bounce-back to the hospital) will face a 0.64% cut under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in FY 2013.

"[Readmissions are] a very, very resistant problem with our patients," Dr. Joshi explained.

Many times, families may insist that their loved ones go to the emergency department when their conditions worsen. In the case of falls, there is little alternative to returning to the hospital because most SNFs don’t have appropriate imaging equipment.

"There are limitations in what we can do, but if there’s any chance of cutting down readmissions, it needs to be with bedside presence," Dr. Joshi said.

Multidisciplinary Approach

At Sarasota (Fla.) Memorial Hospital, one focus in the fight to lower readmission rates is on heart failure.

The hospital established a heart failure center for ambulatory patients and instituted telemonitoring for nonambulatory patients who are discharged to home. A team of hospitalists, cardiologists, floor nurses, and home health care staff identifies high-risk heart failure patients, addresses their needs in the hospital, and arranges for follow-up care after discharge.

Sarasota Memorial Hospital is considered a standout when it comes to keeping readmission rates low. It was one of only two hospitals identified by CMS as having better-than-average readmission rates for all three assessed conditions.

The lion’s share of the credit for their success goes to the multidisciplinary culture of the health system, according to Dr. John Moritz, a hospitalist at Sarasota Memorial.

"Communication and teamwork are key," Dr. Moritz said. "Our whole culture is characterized by working with the other staff members to ensure a favorable outcome for our patients."

This fall, Sarasota Memorial will take that approach a step further. They have dedicated two hospital floors to multidisciplinary rounds, where hospitalists, case managers, social workers, heart failure nurses, and physical therapists will round as a group.

"During that visit, we’ll be able to identify what’s needed," Dr. Moritz said. "We’ll be able to clearly communicate that to the patient and to each other."

Applying Project BOOST

Sherman Health System in Elgin, Ill., also takes a multipronged, multidisciplinary approach. The hospital is one of the mentored-implementation sites for Project BOOST, a Society of Hospital Medicine initiative to improve the hospital-to-home transition while reducing readmission rates and length of stay.

At Sherman Health, nurses employ "teach back" techniques, in which they teach patients about their discharge instructions and ask them open-ended questions to make sure the patients understand.

"Patients will tell us anything to get out the door," said Kelly Tarpey, R.N., director of clinical excellence at Sherman Health. "What teach back does is make sure that the key points really are validated and understood."

After using the teach-back approach on one unit, Sherman Health saw its H-CAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) survey scores increase for patient perception of the quality of the discharge instruction, from 84% in 2011 to 92% in 2012, according to the hospital.

Through BOOST, they have also taken a more aggressive approach to postdischarge follow-up. Although the hospital staff has always called patients 24-48 hours after discharge, they are now focusing the calls on clinical concerns. Nurses have the patients’ charts in hand when they call and ask about medications and follow-up appointments. And the nurses continue to use the teach back method they employed in the hospital.

So far, the BOOST work and other care-coordination efforts seem to be paying off. In the first half of 2009, Sherman Health’s 30-day readmission rates for heart failure were 26%. But by the second half of 2011, that figure had fallen to 11%, according to the hospital.

But the improvements came too late to shield the health system from Medicare penalties that are based on performance data. Sherman Health will face a 0.61% cut to its Medicare payments starting in October.

Paying Attention to the Stick

Although hospitals are at various stages of readiness, experts say it is the penalty that has made readmissions a top priority for many hospitalist programs.

Dr. Luke Hansen of Northwestern University in Chicago and the lead analyst for Project BOOST said that there has been a steady increase in the attention that hospitals have paid to readmissions in just the last 3 years. Now when he first meets with the staff at a BOOST site, they are much more likely to have already undertaken some type of effort to reduce readmissions. They also frequently have funded positions such as a transitions nurse who can help identify patients at high risk for rehospitalization.

"Those are things that in the beginning were really uncommon," he said.

Many hospitalist programs are leading the readmission reduction efforts in their institutions, said Dr. Greg Maynard of the University of California, San Diego, and a coinvestigator for Project BOOST. Hospitalists are leading system redesigns by improving interdisciplinary rounds, setting up communication protocols, and reaching out to providers outside the hospital.

"For the first time in my memory, there’s a lot of work being done with the hospital and hospitalists’ groups working with outside groups of skilled nursing facilities, for example," Dr. Maynard said. "I am seeing an incredible amount of dynamism around better partnership, better communication, [and] better tools, and I think hospitalists are playing a big role in that."

In contrast, Dr. Maynard said that there are also hospitalist programs in which the business model allows time only for seeing patients, not for quality improvement.

"To them, it feels like something is being done to them," he said. "They may be feeling like they’re victims instead of leaders."