User login

Many years ago, when I was still in primary care (internal medicine), I thought I knew a bit about the practice of medicine. I was totally comfortable in the hospital (in those days, we saw our own patients twice a day in the hospital), including the ER, the OR, even obstetrics. MIs, shootings, stab wounds, renal failure—I would never say I had mastered them, but I was comfortable with most of what I saw. Deliveries, assisting with C-sections, performing lumbar punctures, performing and interpreting exercise tolerance tests, performing flexible sigmoidoscopies—no problem.

But the one thing that nearly always stopped me in my tracks was … you guessed it: dermatology complaints. Rashes, lesions, or any other skin complaint the least bit out of the ordinary were completely baffling to me. I still remember that feeling after all these years (and I still occasionally experience it!).

I felt like saying to those patients: What in the world would make you think I’d have any idea what that is? But of course, I couldn’t say that, so I’d mumble something, throw some cream at it, then quickly change the subject. Mind you, this was in a setting where a derm referral from us would take 4 to 6 months. And in case you’re wondering, the other providers in my department were as bad at derm as I was.

Long story short, it got to the point that I would scan my schedule every morning, praying I wouldn’t see the word “rash” or “skin.” But, of course, they still came—often just as my hand touched the doorknob to leave: “Oh, by the way, what about this …?” You get the picture. Many of you, if not most, live that picture.

I finally got up the nerve to go to our dermatology department to ask if I could follow one of the docs while he saw patients. Little did I know that practically every provider in the building had already done the same, and had been dismissed with words that essentially meant, “You? A mere PA? You can’t get there from here. Just send ’em to us.”

For a short time, I bought that line—but in the meantime, my patients were not getting the care they needed. So, driven in part by anger at the notion that a mere PA was simply unable to learn dermatology, I bought a decent textbook, Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas of Dermatology, and started reading it. I also started collecting all the derm articles I could find in the journals, and read about those cases.

I won’t bore you with the grimy details, but what I did differently was work at learning derm (what a concept!). I started going to derm conferences, bought a good camera and started taking pictures with it, and continued to buy books (this was in the pre-computer days of the ’80s) and actually read them.

Continue to: And a funny thing happened...

And a funny thing happened: The more I read, the more diagnoses I recognized on my patients. My colleagues and the clinic schedulers took note of this and began sending me their problem cases. Even the derm department, beleaguered as usual by huge backlogs of patients, started sending patients to me. By 1985, even though I was in the internal medicine department, I had transitioned to doing derm fulltime. And that’s what I’ve been doing since.

Around 1992, I discovered that I was one of 6 dermatology PAs in this country. Last time I checked, our numbers were approaching 4,000. So, yes, derm is indeed difficult, but rocket science it isn’t.

Being the pedantic sort that I am, and finding that whole experience so enlightening, I resolved to make it my mission to foster the use of PAs in dermatology—part of which involves the education of those PAs, by means of taking students but also by writing articles (several hundred at last count) and lecturing at conferences and at PA programs. Nearing retirement, I only practice two days a week, but I write and publish at least 5 clinical articles a month, all of which are based on real cases: my cases, using my photos, doing new research on each case. This keeps my knowledge fresh and my 75-year-old mind sharp, helps ward off burnout, and, most importantly, saves lives while reducing patient discomfort.

What follows are 10 dermatology pearls that I have gleaned along the way. My apologies to my former students and attendees at my lectures who’ve heard all this before:

1 If the treatment for your diagnosis isn’t working, consider another diagnosis. Here’s an example (Figure 1): A man in his 50s was sent to dermatology for psoriasis that wasn’t responding to a biologic. Was it really psoriasis? A KOH prep quickly showed it to be tinea corporis, which cleared completely with a month’s worth of oral terbinafine (250 mg qid).

Continue to: #2...

2 The correct diagnosis dictates correct treatment. This may sound obvious, but in primary care, the emphasis is often on “let’s try this” or “let’s try that,” an understandable approach to a symptomatic patient with an uncertain diagnosis. But by the time he finally gets to dermatology, the patient has tried a whole bag full of prescription and OTC products given for numerous, totally different diagnoses. A better approach might be to expedite an urgent referral to dermatology, when possible.

3 Cutaneous fungal infections (ie, dermatophytosis) are vastly overdiagnosed, especially by novices. If you truly suspect it, ask about a potential source; one doesn’t acquire a fungal infection out of thin air. It must come from a person, animal, or occasionally, the soil. It also helps if the victim has been rendered susceptible by the injudicious use of steroids. Better yet, find the fungus with a microscopic examination (KOH prep) or culture. Finally, remember, not everything round and scaly is fungal (see Figure 2).

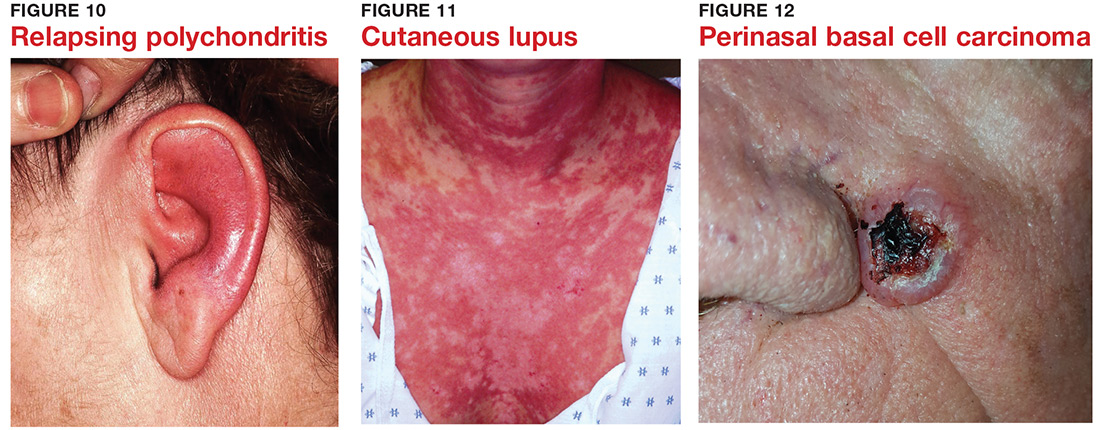

4 Remember these ancient words of wisdom regarding skin complaints: (a) A diagnosis is seldom made if not entertained, (b) you won’t entertain it if you’ve never heard of it, (c) you will not see it if you’re not looking for it, and (d) even if you did see it, you would not “see” it because you’re not looking for it. Dermatology is far deeper and wider than most imagine it to be. The trick is to expose yourself to as many different diagnoses as possible, by reading and attending lectures, ahead of the possible sighting. Figures 3 and 4 offer examples of common conditions that are seldom recognized outside dermatology.

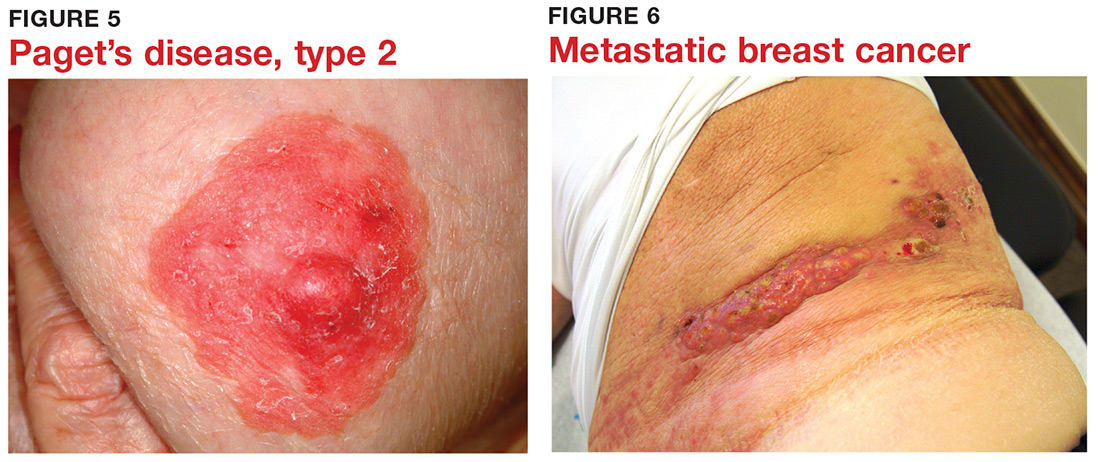

5 Skin cancer can present as a rash. Examples abound, such as mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease (Figure 5), mycosis fungoides, metastatic breast cancer (Figure 6), and superficial basal cell carcinoma. A biopsy is usually required to diagnose these, but you wouldn’t think to do that if you’d never heard of the condition.

6 Melanoma doesn’t typically arise from a mole or other pre-existing lesion. Far more often, it arises “de novo,” out of nothing. So, in general, we’re not worried about “moles” (nevi) unless there’s a history of change (see Figure 7).

Continue to: #7...

7 When looking for skin cancer, pay as much attention to the owner as to the lesion. The most common skin cancers—basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma—usually occur on sun-damaged, fair-skinned, blue-eyed older patients. Though there are certainly exceptions to this paradigm, it pays to be generally suspicious of any odd lesion seen on these patients (Figure 8).

8 It’s practically impossible to overstate the role of atopy when evaluating pediatric skin complaints. These children—20% of all newborns!—are born with thin, dry, sensitive, overreactive skin that is prone to eczema and urticaria. They will also have a marked tendency to develop seasonal allergies, allergic rhinitis, and asthma. Parents find it difficult to accept the genetic basis for atopic dermatitis (Figure 9), preferring instead to blame everything on laundry detergent or food. Education (of oneself first!) is the key.

9 “Infections” are not always what they seem

10 Overcome your fear of steroids by educating yourself about their safe use. Glucocorticoids (eg, triamcinolone, prednisone, betamethasone) are extremely useful in treating common derm conditions. We see patients every day who are so frightened of steroids, they won’t even consider using them because some well-meaning medical provider scared them to death. The proper use of these miraculous products could easily be the subject of an entire article. For now, I’ll advise you to read about their safe use in any number of dermatology texts (including online publications).

Many years ago, when I was still in primary care (internal medicine), I thought I knew a bit about the practice of medicine. I was totally comfortable in the hospital (in those days, we saw our own patients twice a day in the hospital), including the ER, the OR, even obstetrics. MIs, shootings, stab wounds, renal failure—I would never say I had mastered them, but I was comfortable with most of what I saw. Deliveries, assisting with C-sections, performing lumbar punctures, performing and interpreting exercise tolerance tests, performing flexible sigmoidoscopies—no problem.

But the one thing that nearly always stopped me in my tracks was … you guessed it: dermatology complaints. Rashes, lesions, or any other skin complaint the least bit out of the ordinary were completely baffling to me. I still remember that feeling after all these years (and I still occasionally experience it!).

I felt like saying to those patients: What in the world would make you think I’d have any idea what that is? But of course, I couldn’t say that, so I’d mumble something, throw some cream at it, then quickly change the subject. Mind you, this was in a setting where a derm referral from us would take 4 to 6 months. And in case you’re wondering, the other providers in my department were as bad at derm as I was.

Long story short, it got to the point that I would scan my schedule every morning, praying I wouldn’t see the word “rash” or “skin.” But, of course, they still came—often just as my hand touched the doorknob to leave: “Oh, by the way, what about this …?” You get the picture. Many of you, if not most, live that picture.

I finally got up the nerve to go to our dermatology department to ask if I could follow one of the docs while he saw patients. Little did I know that practically every provider in the building had already done the same, and had been dismissed with words that essentially meant, “You? A mere PA? You can’t get there from here. Just send ’em to us.”

For a short time, I bought that line—but in the meantime, my patients were not getting the care they needed. So, driven in part by anger at the notion that a mere PA was simply unable to learn dermatology, I bought a decent textbook, Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas of Dermatology, and started reading it. I also started collecting all the derm articles I could find in the journals, and read about those cases.

I won’t bore you with the grimy details, but what I did differently was work at learning derm (what a concept!). I started going to derm conferences, bought a good camera and started taking pictures with it, and continued to buy books (this was in the pre-computer days of the ’80s) and actually read them.

Continue to: And a funny thing happened...

And a funny thing happened: The more I read, the more diagnoses I recognized on my patients. My colleagues and the clinic schedulers took note of this and began sending me their problem cases. Even the derm department, beleaguered as usual by huge backlogs of patients, started sending patients to me. By 1985, even though I was in the internal medicine department, I had transitioned to doing derm fulltime. And that’s what I’ve been doing since.

Around 1992, I discovered that I was one of 6 dermatology PAs in this country. Last time I checked, our numbers were approaching 4,000. So, yes, derm is indeed difficult, but rocket science it isn’t.

Being the pedantic sort that I am, and finding that whole experience so enlightening, I resolved to make it my mission to foster the use of PAs in dermatology—part of which involves the education of those PAs, by means of taking students but also by writing articles (several hundred at last count) and lecturing at conferences and at PA programs. Nearing retirement, I only practice two days a week, but I write and publish at least 5 clinical articles a month, all of which are based on real cases: my cases, using my photos, doing new research on each case. This keeps my knowledge fresh and my 75-year-old mind sharp, helps ward off burnout, and, most importantly, saves lives while reducing patient discomfort.

What follows are 10 dermatology pearls that I have gleaned along the way. My apologies to my former students and attendees at my lectures who’ve heard all this before:

1 If the treatment for your diagnosis isn’t working, consider another diagnosis. Here’s an example (Figure 1): A man in his 50s was sent to dermatology for psoriasis that wasn’t responding to a biologic. Was it really psoriasis? A KOH prep quickly showed it to be tinea corporis, which cleared completely with a month’s worth of oral terbinafine (250 mg qid).

Continue to: #2...

2 The correct diagnosis dictates correct treatment. This may sound obvious, but in primary care, the emphasis is often on “let’s try this” or “let’s try that,” an understandable approach to a symptomatic patient with an uncertain diagnosis. But by the time he finally gets to dermatology, the patient has tried a whole bag full of prescription and OTC products given for numerous, totally different diagnoses. A better approach might be to expedite an urgent referral to dermatology, when possible.

3 Cutaneous fungal infections (ie, dermatophytosis) are vastly overdiagnosed, especially by novices. If you truly suspect it, ask about a potential source; one doesn’t acquire a fungal infection out of thin air. It must come from a person, animal, or occasionally, the soil. It also helps if the victim has been rendered susceptible by the injudicious use of steroids. Better yet, find the fungus with a microscopic examination (KOH prep) or culture. Finally, remember, not everything round and scaly is fungal (see Figure 2).

4 Remember these ancient words of wisdom regarding skin complaints: (a) A diagnosis is seldom made if not entertained, (b) you won’t entertain it if you’ve never heard of it, (c) you will not see it if you’re not looking for it, and (d) even if you did see it, you would not “see” it because you’re not looking for it. Dermatology is far deeper and wider than most imagine it to be. The trick is to expose yourself to as many different diagnoses as possible, by reading and attending lectures, ahead of the possible sighting. Figures 3 and 4 offer examples of common conditions that are seldom recognized outside dermatology.

5 Skin cancer can present as a rash. Examples abound, such as mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease (Figure 5), mycosis fungoides, metastatic breast cancer (Figure 6), and superficial basal cell carcinoma. A biopsy is usually required to diagnose these, but you wouldn’t think to do that if you’d never heard of the condition.

6 Melanoma doesn’t typically arise from a mole or other pre-existing lesion. Far more often, it arises “de novo,” out of nothing. So, in general, we’re not worried about “moles” (nevi) unless there’s a history of change (see Figure 7).

Continue to: #7...

7 When looking for skin cancer, pay as much attention to the owner as to the lesion. The most common skin cancers—basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma—usually occur on sun-damaged, fair-skinned, blue-eyed older patients. Though there are certainly exceptions to this paradigm, it pays to be generally suspicious of any odd lesion seen on these patients (Figure 8).

8 It’s practically impossible to overstate the role of atopy when evaluating pediatric skin complaints. These children—20% of all newborns!—are born with thin, dry, sensitive, overreactive skin that is prone to eczema and urticaria. They will also have a marked tendency to develop seasonal allergies, allergic rhinitis, and asthma. Parents find it difficult to accept the genetic basis for atopic dermatitis (Figure 9), preferring instead to blame everything on laundry detergent or food. Education (of oneself first!) is the key.

9 “Infections” are not always what they seem

10 Overcome your fear of steroids by educating yourself about their safe use. Glucocorticoids (eg, triamcinolone, prednisone, betamethasone) are extremely useful in treating common derm conditions. We see patients every day who are so frightened of steroids, they won’t even consider using them because some well-meaning medical provider scared them to death. The proper use of these miraculous products could easily be the subject of an entire article. For now, I’ll advise you to read about their safe use in any number of dermatology texts (including online publications).

Many years ago, when I was still in primary care (internal medicine), I thought I knew a bit about the practice of medicine. I was totally comfortable in the hospital (in those days, we saw our own patients twice a day in the hospital), including the ER, the OR, even obstetrics. MIs, shootings, stab wounds, renal failure—I would never say I had mastered them, but I was comfortable with most of what I saw. Deliveries, assisting with C-sections, performing lumbar punctures, performing and interpreting exercise tolerance tests, performing flexible sigmoidoscopies—no problem.

But the one thing that nearly always stopped me in my tracks was … you guessed it: dermatology complaints. Rashes, lesions, or any other skin complaint the least bit out of the ordinary were completely baffling to me. I still remember that feeling after all these years (and I still occasionally experience it!).

I felt like saying to those patients: What in the world would make you think I’d have any idea what that is? But of course, I couldn’t say that, so I’d mumble something, throw some cream at it, then quickly change the subject. Mind you, this was in a setting where a derm referral from us would take 4 to 6 months. And in case you’re wondering, the other providers in my department were as bad at derm as I was.

Long story short, it got to the point that I would scan my schedule every morning, praying I wouldn’t see the word “rash” or “skin.” But, of course, they still came—often just as my hand touched the doorknob to leave: “Oh, by the way, what about this …?” You get the picture. Many of you, if not most, live that picture.

I finally got up the nerve to go to our dermatology department to ask if I could follow one of the docs while he saw patients. Little did I know that practically every provider in the building had already done the same, and had been dismissed with words that essentially meant, “You? A mere PA? You can’t get there from here. Just send ’em to us.”

For a short time, I bought that line—but in the meantime, my patients were not getting the care they needed. So, driven in part by anger at the notion that a mere PA was simply unable to learn dermatology, I bought a decent textbook, Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas of Dermatology, and started reading it. I also started collecting all the derm articles I could find in the journals, and read about those cases.

I won’t bore you with the grimy details, but what I did differently was work at learning derm (what a concept!). I started going to derm conferences, bought a good camera and started taking pictures with it, and continued to buy books (this was in the pre-computer days of the ’80s) and actually read them.

Continue to: And a funny thing happened...

And a funny thing happened: The more I read, the more diagnoses I recognized on my patients. My colleagues and the clinic schedulers took note of this and began sending me their problem cases. Even the derm department, beleaguered as usual by huge backlogs of patients, started sending patients to me. By 1985, even though I was in the internal medicine department, I had transitioned to doing derm fulltime. And that’s what I’ve been doing since.

Around 1992, I discovered that I was one of 6 dermatology PAs in this country. Last time I checked, our numbers were approaching 4,000. So, yes, derm is indeed difficult, but rocket science it isn’t.

Being the pedantic sort that I am, and finding that whole experience so enlightening, I resolved to make it my mission to foster the use of PAs in dermatology—part of which involves the education of those PAs, by means of taking students but also by writing articles (several hundred at last count) and lecturing at conferences and at PA programs. Nearing retirement, I only practice two days a week, but I write and publish at least 5 clinical articles a month, all of which are based on real cases: my cases, using my photos, doing new research on each case. This keeps my knowledge fresh and my 75-year-old mind sharp, helps ward off burnout, and, most importantly, saves lives while reducing patient discomfort.

What follows are 10 dermatology pearls that I have gleaned along the way. My apologies to my former students and attendees at my lectures who’ve heard all this before:

1 If the treatment for your diagnosis isn’t working, consider another diagnosis. Here’s an example (Figure 1): A man in his 50s was sent to dermatology for psoriasis that wasn’t responding to a biologic. Was it really psoriasis? A KOH prep quickly showed it to be tinea corporis, which cleared completely with a month’s worth of oral terbinafine (250 mg qid).

Continue to: #2...

2 The correct diagnosis dictates correct treatment. This may sound obvious, but in primary care, the emphasis is often on “let’s try this” or “let’s try that,” an understandable approach to a symptomatic patient with an uncertain diagnosis. But by the time he finally gets to dermatology, the patient has tried a whole bag full of prescription and OTC products given for numerous, totally different diagnoses. A better approach might be to expedite an urgent referral to dermatology, when possible.

3 Cutaneous fungal infections (ie, dermatophytosis) are vastly overdiagnosed, especially by novices. If you truly suspect it, ask about a potential source; one doesn’t acquire a fungal infection out of thin air. It must come from a person, animal, or occasionally, the soil. It also helps if the victim has been rendered susceptible by the injudicious use of steroids. Better yet, find the fungus with a microscopic examination (KOH prep) or culture. Finally, remember, not everything round and scaly is fungal (see Figure 2).

4 Remember these ancient words of wisdom regarding skin complaints: (a) A diagnosis is seldom made if not entertained, (b) you won’t entertain it if you’ve never heard of it, (c) you will not see it if you’re not looking for it, and (d) even if you did see it, you would not “see” it because you’re not looking for it. Dermatology is far deeper and wider than most imagine it to be. The trick is to expose yourself to as many different diagnoses as possible, by reading and attending lectures, ahead of the possible sighting. Figures 3 and 4 offer examples of common conditions that are seldom recognized outside dermatology.

5 Skin cancer can present as a rash. Examples abound, such as mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease (Figure 5), mycosis fungoides, metastatic breast cancer (Figure 6), and superficial basal cell carcinoma. A biopsy is usually required to diagnose these, but you wouldn’t think to do that if you’d never heard of the condition.

6 Melanoma doesn’t typically arise from a mole or other pre-existing lesion. Far more often, it arises “de novo,” out of nothing. So, in general, we’re not worried about “moles” (nevi) unless there’s a history of change (see Figure 7).

Continue to: #7...

7 When looking for skin cancer, pay as much attention to the owner as to the lesion. The most common skin cancers—basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma—usually occur on sun-damaged, fair-skinned, blue-eyed older patients. Though there are certainly exceptions to this paradigm, it pays to be generally suspicious of any odd lesion seen on these patients (Figure 8).

8 It’s practically impossible to overstate the role of atopy when evaluating pediatric skin complaints. These children—20% of all newborns!—are born with thin, dry, sensitive, overreactive skin that is prone to eczema and urticaria. They will also have a marked tendency to develop seasonal allergies, allergic rhinitis, and asthma. Parents find it difficult to accept the genetic basis for atopic dermatitis (Figure 9), preferring instead to blame everything on laundry detergent or food. Education (of oneself first!) is the key.

9 “Infections” are not always what they seem

10 Overcome your fear of steroids by educating yourself about their safe use. Glucocorticoids (eg, triamcinolone, prednisone, betamethasone) are extremely useful in treating common derm conditions. We see patients every day who are so frightened of steroids, they won’t even consider using them because some well-meaning medical provider scared them to death. The proper use of these miraculous products could easily be the subject of an entire article. For now, I’ll advise you to read about their safe use in any number of dermatology texts (including online publications).