User login

A psychiatrist colleague once remarked that I did a better-than-average job diagnosing depression. Maybe so, but I was never quite sure if my patients really met established diagnostic criteria, since I usually “gestalted” the diagnosis. I would talk to my patients about depression so they would understand and accept it as a treatable medical condition, not a moral failing.

Recommending appropriate therapy was fairly easy, since information on pharmacotherapy is so prevalent. But I rarely learned how well my depressed patients were doing, since I practiced the “no news is good news” model of chronic disease management.

Then I was invited to participate in a practice-based study of depression.1 I learned a better way to manage depression, which was more effective, satisfying, and—believe it or not—more efficient than the old way. I learned that successful management also saved time and money by reducing fruitless diagnostic testing and return visits for unmet needs.

The 5 Linked Tasks Of Successful Management

Successful management of depression requires completion of 5 linked tasks: recognition, diagnosis, treatment, systematic follow-up, and outcome assessment. Most important for the busy practitioner, these tasks can be completed without disrupting “usual” patient care.

What specific tools did I acquire? I’ll describe them according to tasks; the first task—recognition—deserves special emphasis and is discussed last.

Diagnosis: 9 simple questions

Whenever I suspect the possibility of depression in a patient, I ask the 9 simple questions in the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).2,3 The PHQ-9 instrument is the best available depression screening tool for primary care.4 An affirmative answer to either question A or B plus a total of 5 positive “nearly every day” replies indicates a diagnosis of major depression. Fewer symptoms indicate minor depression, for which therapy is individualized (Figure 1).

It takes about 1 or 2 minutes to make a PHQ-9 diagnosis of depression; listening to the patient’s story fleshes out the diagnosis and may reveal underlying comorbidities (such as alcohol use or physical abuse) that guide the next task.

I minimize diagnostic testing. In 16 months, 1 of 95 patients in my practice with major depression turned out to have a significant underlying medical illness responsible for his symptoms. I diagnosed a lymphoma during systematic follow-up when treatment failed.

FIGURE 1

PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

Treatment: What to discuss

I use most of the office visit to discuss the diagnosis, patient preferences for treatment (or no treatment), and pharmacotherapy indications, expectations, and side effects. In my experience, this discussion is usually completed within the allotted time of the appointment.

Follow-up: Make 3 appointments

I ask patients to make 3 follow-up appointments: at 1 week (to assess medication side effects, if medication is prescribed), at 4 weeks (to assess early response), and at 8 weeks (to assess maintenance of response). After the week-8 visit, I ask patients to return every 3 months, or sooner if not at goal.

If the patient declines pharmacologic treatment, or if referral for counseling is the sole treatment decision, the schedule of follow-up visits may vary. Visits would then be spent assessing whether the patient is improving or in need of additional treatment.

Outcome assessment: Take “emotional temperature”

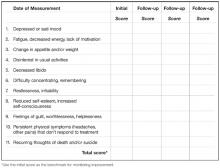

I obtain a quantitative “depression score” (Figure 2) at the initial diagnostic visit and at each follow-up visit. This ad hoc scoring system, developed by my psychiatrist partners, complements a patient’s report of progress. Scores collected from individual patients can also be used to assess overall improvement in the practice population of depressed patients.

I have found that patients understand and support having their “emotional temperature” taken at each visit. The PHQ-9 can be used to quantitate improvement during follow-up visits.3

FIGURE 2

Depression Scoring System

Recognition: Pandora’s box?

No matter how efficient, practical, and “userfriendly,” a protocol is of no value if unused. I suspect that, consciously or unconsciously, many physicians avoid opening the “Pandora’s box” of depression, because they fear disrupting the office schedule.

In my practice, recognizing and managing depression—and other unexpected patient issues—necessitated, I now realize, a complete re-engineering of the way I practiced medicine. Suppose you went to a shoe store on Friday to buy a pair of hiking boots for a weekend outing and were told, “Sorry, you’ll have to come back next week: we sell hiking boots only on Tuesdays and Thursdays.” Think how absurd that would be, and then realize it is exactly how most doctors schedule patient visits—on the “quota system,” despite good evidence that patients’ primary care needs cannot be conveniently categorized and scheduled.

All I know about my schedule at the start of a day is that I will encounter 25 to 30 patients, and that I will leave the office when it closes. I will not know in advance the complaints, treatments, and time I should spend with each patient. This flexible scheduling works well and liberates me to address patients’ spontaneous needs as they arise during the office encounter.

Case Finding: Don’t Trust Appearances

For depression, the case-finding approach is preferable to screening the entire practice.5 I no longer trust appearances to recognize depression. While participating in the practice-based study of depression,1 I encountered a hardworking, cheerful female executive who had undergone many diagnostic procedures and who did not at all appear depressed—but she was. She got better after treatment and expressed profound gratitude. Not all severely affected patients present saying, “I’m depressed, please treat me.”

Unexplained somatic complaints

In my practice, one third of depressed patients complain only of a variety of somatic symptoms. I tell medical students, “If you can’t figure out what’s going on in an office encounter within minutes (1 to 3 minutes, depending on the level of training), think depression or alcohol abuse.” This clinical pearl is memorable and mostly accurate; the differential diagnosis can be expanded throughout training.

Stress? Suspect depression

Two thirds of my patients with diagnosed depression allude to “stress,” but often only in a very roundabout manner. So, whenever a patient utters the word “stress” during an office encounter, out comes the PHQ-9. I cannot think of a simpler technique for recognizing depression. In general, it is also well to remember that patients suffering from chronic diseases will have a higher-than-average likelihood of associated depression.

Managing depression should be simple

The management of depression should resemble the management of diabetes: astute case finding (mass screening for diabetes is not recommended), clearly defined diagnosis (blood sugar level), effective treatment (both behavioral and pharmacologic), systematic follow-up, and a quantitative outcome (glycosylated hemoglobin level). Diabetes was formerly managed as an acute illness, since once upon a time it was acceptable just to keep patients out of ketoacidosis. Today we treat diabetes better, and patients do better. Now it is time to do better with depression.

Correspondence

David L. Hahn, MD, MS, Arcand Park Clinic, 3434 East Washington Ave, Madison WI 53704. E-mail: dlhahn@wiscmail.wisc.edu

1. Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Henk HJ. Effect of primary care treatment of depression on service use by patients with high medical expenditures. Psychiatr Serv 1997;48:59-64.

2. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 1994;272:1749-1756.

3. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA 1999;282:1737-1744.

4. Nease Jr DE, Malouin JM. Depression screening: a practical strategy. J Fam Pract 2003;52:118-126.

5. Valenstein M, Vijan S, Zeber JE, Boehm K, Buttar A. The cost-utility of screening for depression in primary care. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:345-360.

A psychiatrist colleague once remarked that I did a better-than-average job diagnosing depression. Maybe so, but I was never quite sure if my patients really met established diagnostic criteria, since I usually “gestalted” the diagnosis. I would talk to my patients about depression so they would understand and accept it as a treatable medical condition, not a moral failing.

Recommending appropriate therapy was fairly easy, since information on pharmacotherapy is so prevalent. But I rarely learned how well my depressed patients were doing, since I practiced the “no news is good news” model of chronic disease management.

Then I was invited to participate in a practice-based study of depression.1 I learned a better way to manage depression, which was more effective, satisfying, and—believe it or not—more efficient than the old way. I learned that successful management also saved time and money by reducing fruitless diagnostic testing and return visits for unmet needs.

The 5 Linked Tasks Of Successful Management

Successful management of depression requires completion of 5 linked tasks: recognition, diagnosis, treatment, systematic follow-up, and outcome assessment. Most important for the busy practitioner, these tasks can be completed without disrupting “usual” patient care.

What specific tools did I acquire? I’ll describe them according to tasks; the first task—recognition—deserves special emphasis and is discussed last.

Diagnosis: 9 simple questions

Whenever I suspect the possibility of depression in a patient, I ask the 9 simple questions in the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).2,3 The PHQ-9 instrument is the best available depression screening tool for primary care.4 An affirmative answer to either question A or B plus a total of 5 positive “nearly every day” replies indicates a diagnosis of major depression. Fewer symptoms indicate minor depression, for which therapy is individualized (Figure 1).

It takes about 1 or 2 minutes to make a PHQ-9 diagnosis of depression; listening to the patient’s story fleshes out the diagnosis and may reveal underlying comorbidities (such as alcohol use or physical abuse) that guide the next task.

I minimize diagnostic testing. In 16 months, 1 of 95 patients in my practice with major depression turned out to have a significant underlying medical illness responsible for his symptoms. I diagnosed a lymphoma during systematic follow-up when treatment failed.

FIGURE 1

PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

Treatment: What to discuss

I use most of the office visit to discuss the diagnosis, patient preferences for treatment (or no treatment), and pharmacotherapy indications, expectations, and side effects. In my experience, this discussion is usually completed within the allotted time of the appointment.

Follow-up: Make 3 appointments

I ask patients to make 3 follow-up appointments: at 1 week (to assess medication side effects, if medication is prescribed), at 4 weeks (to assess early response), and at 8 weeks (to assess maintenance of response). After the week-8 visit, I ask patients to return every 3 months, or sooner if not at goal.

If the patient declines pharmacologic treatment, or if referral for counseling is the sole treatment decision, the schedule of follow-up visits may vary. Visits would then be spent assessing whether the patient is improving or in need of additional treatment.

Outcome assessment: Take “emotional temperature”

I obtain a quantitative “depression score” (Figure 2) at the initial diagnostic visit and at each follow-up visit. This ad hoc scoring system, developed by my psychiatrist partners, complements a patient’s report of progress. Scores collected from individual patients can also be used to assess overall improvement in the practice population of depressed patients.

I have found that patients understand and support having their “emotional temperature” taken at each visit. The PHQ-9 can be used to quantitate improvement during follow-up visits.3

FIGURE 2

Depression Scoring System

Recognition: Pandora’s box?

No matter how efficient, practical, and “userfriendly,” a protocol is of no value if unused. I suspect that, consciously or unconsciously, many physicians avoid opening the “Pandora’s box” of depression, because they fear disrupting the office schedule.

In my practice, recognizing and managing depression—and other unexpected patient issues—necessitated, I now realize, a complete re-engineering of the way I practiced medicine. Suppose you went to a shoe store on Friday to buy a pair of hiking boots for a weekend outing and were told, “Sorry, you’ll have to come back next week: we sell hiking boots only on Tuesdays and Thursdays.” Think how absurd that would be, and then realize it is exactly how most doctors schedule patient visits—on the “quota system,” despite good evidence that patients’ primary care needs cannot be conveniently categorized and scheduled.

All I know about my schedule at the start of a day is that I will encounter 25 to 30 patients, and that I will leave the office when it closes. I will not know in advance the complaints, treatments, and time I should spend with each patient. This flexible scheduling works well and liberates me to address patients’ spontaneous needs as they arise during the office encounter.

Case Finding: Don’t Trust Appearances

For depression, the case-finding approach is preferable to screening the entire practice.5 I no longer trust appearances to recognize depression. While participating in the practice-based study of depression,1 I encountered a hardworking, cheerful female executive who had undergone many diagnostic procedures and who did not at all appear depressed—but she was. She got better after treatment and expressed profound gratitude. Not all severely affected patients present saying, “I’m depressed, please treat me.”

Unexplained somatic complaints

In my practice, one third of depressed patients complain only of a variety of somatic symptoms. I tell medical students, “If you can’t figure out what’s going on in an office encounter within minutes (1 to 3 minutes, depending on the level of training), think depression or alcohol abuse.” This clinical pearl is memorable and mostly accurate; the differential diagnosis can be expanded throughout training.

Stress? Suspect depression

Two thirds of my patients with diagnosed depression allude to “stress,” but often only in a very roundabout manner. So, whenever a patient utters the word “stress” during an office encounter, out comes the PHQ-9. I cannot think of a simpler technique for recognizing depression. In general, it is also well to remember that patients suffering from chronic diseases will have a higher-than-average likelihood of associated depression.

Managing depression should be simple

The management of depression should resemble the management of diabetes: astute case finding (mass screening for diabetes is not recommended), clearly defined diagnosis (blood sugar level), effective treatment (both behavioral and pharmacologic), systematic follow-up, and a quantitative outcome (glycosylated hemoglobin level). Diabetes was formerly managed as an acute illness, since once upon a time it was acceptable just to keep patients out of ketoacidosis. Today we treat diabetes better, and patients do better. Now it is time to do better with depression.

Correspondence

David L. Hahn, MD, MS, Arcand Park Clinic, 3434 East Washington Ave, Madison WI 53704. E-mail: dlhahn@wiscmail.wisc.edu

A psychiatrist colleague once remarked that I did a better-than-average job diagnosing depression. Maybe so, but I was never quite sure if my patients really met established diagnostic criteria, since I usually “gestalted” the diagnosis. I would talk to my patients about depression so they would understand and accept it as a treatable medical condition, not a moral failing.

Recommending appropriate therapy was fairly easy, since information on pharmacotherapy is so prevalent. But I rarely learned how well my depressed patients were doing, since I practiced the “no news is good news” model of chronic disease management.

Then I was invited to participate in a practice-based study of depression.1 I learned a better way to manage depression, which was more effective, satisfying, and—believe it or not—more efficient than the old way. I learned that successful management also saved time and money by reducing fruitless diagnostic testing and return visits for unmet needs.

The 5 Linked Tasks Of Successful Management

Successful management of depression requires completion of 5 linked tasks: recognition, diagnosis, treatment, systematic follow-up, and outcome assessment. Most important for the busy practitioner, these tasks can be completed without disrupting “usual” patient care.

What specific tools did I acquire? I’ll describe them according to tasks; the first task—recognition—deserves special emphasis and is discussed last.

Diagnosis: 9 simple questions

Whenever I suspect the possibility of depression in a patient, I ask the 9 simple questions in the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).2,3 The PHQ-9 instrument is the best available depression screening tool for primary care.4 An affirmative answer to either question A or B plus a total of 5 positive “nearly every day” replies indicates a diagnosis of major depression. Fewer symptoms indicate minor depression, for which therapy is individualized (Figure 1).

It takes about 1 or 2 minutes to make a PHQ-9 diagnosis of depression; listening to the patient’s story fleshes out the diagnosis and may reveal underlying comorbidities (such as alcohol use or physical abuse) that guide the next task.

I minimize diagnostic testing. In 16 months, 1 of 95 patients in my practice with major depression turned out to have a significant underlying medical illness responsible for his symptoms. I diagnosed a lymphoma during systematic follow-up when treatment failed.

FIGURE 1

PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

Treatment: What to discuss

I use most of the office visit to discuss the diagnosis, patient preferences for treatment (or no treatment), and pharmacotherapy indications, expectations, and side effects. In my experience, this discussion is usually completed within the allotted time of the appointment.

Follow-up: Make 3 appointments

I ask patients to make 3 follow-up appointments: at 1 week (to assess medication side effects, if medication is prescribed), at 4 weeks (to assess early response), and at 8 weeks (to assess maintenance of response). After the week-8 visit, I ask patients to return every 3 months, or sooner if not at goal.

If the patient declines pharmacologic treatment, or if referral for counseling is the sole treatment decision, the schedule of follow-up visits may vary. Visits would then be spent assessing whether the patient is improving or in need of additional treatment.

Outcome assessment: Take “emotional temperature”

I obtain a quantitative “depression score” (Figure 2) at the initial diagnostic visit and at each follow-up visit. This ad hoc scoring system, developed by my psychiatrist partners, complements a patient’s report of progress. Scores collected from individual patients can also be used to assess overall improvement in the practice population of depressed patients.

I have found that patients understand and support having their “emotional temperature” taken at each visit. The PHQ-9 can be used to quantitate improvement during follow-up visits.3

FIGURE 2

Depression Scoring System

Recognition: Pandora’s box?

No matter how efficient, practical, and “userfriendly,” a protocol is of no value if unused. I suspect that, consciously or unconsciously, many physicians avoid opening the “Pandora’s box” of depression, because they fear disrupting the office schedule.

In my practice, recognizing and managing depression—and other unexpected patient issues—necessitated, I now realize, a complete re-engineering of the way I practiced medicine. Suppose you went to a shoe store on Friday to buy a pair of hiking boots for a weekend outing and were told, “Sorry, you’ll have to come back next week: we sell hiking boots only on Tuesdays and Thursdays.” Think how absurd that would be, and then realize it is exactly how most doctors schedule patient visits—on the “quota system,” despite good evidence that patients’ primary care needs cannot be conveniently categorized and scheduled.

All I know about my schedule at the start of a day is that I will encounter 25 to 30 patients, and that I will leave the office when it closes. I will not know in advance the complaints, treatments, and time I should spend with each patient. This flexible scheduling works well and liberates me to address patients’ spontaneous needs as they arise during the office encounter.

Case Finding: Don’t Trust Appearances

For depression, the case-finding approach is preferable to screening the entire practice.5 I no longer trust appearances to recognize depression. While participating in the practice-based study of depression,1 I encountered a hardworking, cheerful female executive who had undergone many diagnostic procedures and who did not at all appear depressed—but she was. She got better after treatment and expressed profound gratitude. Not all severely affected patients present saying, “I’m depressed, please treat me.”

Unexplained somatic complaints

In my practice, one third of depressed patients complain only of a variety of somatic symptoms. I tell medical students, “If you can’t figure out what’s going on in an office encounter within minutes (1 to 3 minutes, depending on the level of training), think depression or alcohol abuse.” This clinical pearl is memorable and mostly accurate; the differential diagnosis can be expanded throughout training.

Stress? Suspect depression

Two thirds of my patients with diagnosed depression allude to “stress,” but often only in a very roundabout manner. So, whenever a patient utters the word “stress” during an office encounter, out comes the PHQ-9. I cannot think of a simpler technique for recognizing depression. In general, it is also well to remember that patients suffering from chronic diseases will have a higher-than-average likelihood of associated depression.

Managing depression should be simple

The management of depression should resemble the management of diabetes: astute case finding (mass screening for diabetes is not recommended), clearly defined diagnosis (blood sugar level), effective treatment (both behavioral and pharmacologic), systematic follow-up, and a quantitative outcome (glycosylated hemoglobin level). Diabetes was formerly managed as an acute illness, since once upon a time it was acceptable just to keep patients out of ketoacidosis. Today we treat diabetes better, and patients do better. Now it is time to do better with depression.

Correspondence

David L. Hahn, MD, MS, Arcand Park Clinic, 3434 East Washington Ave, Madison WI 53704. E-mail: dlhahn@wiscmail.wisc.edu

1. Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Henk HJ. Effect of primary care treatment of depression on service use by patients with high medical expenditures. Psychiatr Serv 1997;48:59-64.

2. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 1994;272:1749-1756.

3. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA 1999;282:1737-1744.

4. Nease Jr DE, Malouin JM. Depression screening: a practical strategy. J Fam Pract 2003;52:118-126.

5. Valenstein M, Vijan S, Zeber JE, Boehm K, Buttar A. The cost-utility of screening for depression in primary care. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:345-360.

1. Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Henk HJ. Effect of primary care treatment of depression on service use by patients with high medical expenditures. Psychiatr Serv 1997;48:59-64.

2. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 1994;272:1749-1756.

3. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA 1999;282:1737-1744.

4. Nease Jr DE, Malouin JM. Depression screening: a practical strategy. J Fam Pract 2003;52:118-126.

5. Valenstein M, Vijan S, Zeber JE, Boehm K, Buttar A. The cost-utility of screening for depression in primary care. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:345-360.