User login

Many veterans of the Gulf War are experiencing deployment-related chronic illness, known as Gulf War illness (GWI). Symptoms of GWI include cognitive impairments (mood and memory), chronic fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, respiratory problems, and skin rashes.1-4 Three survey studies of the physical and mental health of a large cohort of Gulf War and Gulf era veterans, conducted by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Public Health, established the increased prevalence of GWI in the decades that followed the end of the conflict.5-7 Thus, GWI has become the signature adverse health-related outcome of the Gulf War. Quality improvement (QI) within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is needed in the diagnosis and treatment of GWI.

Background

GWI was first termed chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). According to the CDC-10 case definition, CMI in veterans of the 1990-1991 Gulf War is defined as having ≥ 1 symptoms lasting ≥ 6 months in at least 2 of 3 categories: fatigue, depressed mood and altered cognition, and musculoskeletal pain.3 The Kansas case definition of GWI is more specific and is defined as having moderate-to-severe symptoms that are unexplained by any other diagnosis, in at least 3 of 6 categories: fatigue/sleep, somatic pain, neurologic/cognition/mood, GI, respiratory, and skin.4 Although chronic unexplained symptoms have occurred after other modern conflicts, the prevalence of GWI among Gulf War veterans has proven higher than those of prior conflicts.8

The Persian Gulf War Veterans Act of 1998 and the Veterans Programs Enhancement Act of 1998 mandated studies by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) on the biologic and chemical exposures that may have contributed to illness in the Kuwaiti theater of operations.9 However, elucidating the etiology and underlying pathophysiology of GWI has been a major research challenge. In the absence of objective diagnostic measures, an understanding of the fundamental pathophysiology, evidence-based treatments, a single case definition, and definitive guidelines for health care providers (HCPs) for the diagnosis and management of GWI has not been produced. As a result, veterans with GWI have struggled for nearly 3 decades to find a consistent diagnosis of and an effective treatment for their condition.

According to a report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the VA approved only 17% of claims for compensation for veterans with GWI from 2011 to 2015, about one-third the level of approval for all other claimed disabilities.10 Although the VA applied GAO recommendations to improve the compensation process, many veterans consider that their illness is treated as psychosomatic in clinical practice, despite emerging evidence of GWI-associated biomarkers.11 Others think they have been forgotten due to their short 1-year period of service in the Gulf War.12 To realign research, guidelines, clinical care, and the health care experience of veterans with GWI, focused QI within VHA is urgently needed.

Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, and New Dawn (OEF/OIF/OND) are experiencing similar CMI symptoms. A study of US Army Reserve OEF/OIF veterans found that > 60% met the CDC-10 case definition for GWI 1-year postdeployment.13 Thus, CMI is emerging as a serious health problem for post-9/11 veterans. The evidence of postdeployment CMI among veterans of recent conflicts underscores the need to increase efforts at a national level, beginning with the VHA. This report includes a summary of Gulf War veterans’ experiences at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (MVAHCS) and a proposal for QI of MVAHCS processes focused on HCP education and clinical care.

Methods

To determine areas of GWI health care that needed QI at the MVAHCS, veterans with GWI were contacted for a telephone survey. These veterans had participated in the Gulf War Illness Inflammation Reduction Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NCT02506192). Therefore, all met the Kansas case definition for GWI.4 The aim of the survey was to characterize veterans’ experiences seeking health care for chronic postdeployment symptoms.

Sixty Gulf War veterans were contacted by telephone and invited to participate in a 15-minute survey about their experience seeking diagnosis and treatment for GWI. They were informed that the survey was voluntary and confidential, that it was not part of the research trial in which they had been enrolled, and that their participation would not affect compensation received from VA. Verbal consent was requested, and 30 veterans agreed to participate in the survey.

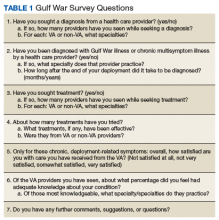

The survey included questions about the course of illness, disability and service connection status, HCPs seen, and suggestions for improvement in their care (Table 1).

Results

Of the 30 veterans who participated in the survey, most were male with only 2 female veterans. This proportion of female veterans (7%) is similar to the overall percentage of female veterans (6.7%) of the first Gulf War.2 Ages ranged from 46 to 66 years with a mean age of 53. Mean duration of illness, defined as time elapsed since perceived onset of chronic systemic symptoms during or after deployment, was 22.8 years, with a range of 4 to 27 years. Most respondents reported symptom onset within a few years after the end of the conflict, while a few reported the onset within weeks of arriving in the Kuwaiti theater of operations. A little more than half the respondents considered themselves disabled due to their symptoms, while one-third reported losing the ability to work due to symptoms. Respondents described needing to reduce hours, retire early, or stop working altogether because of their symptoms.

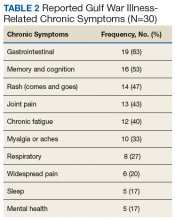

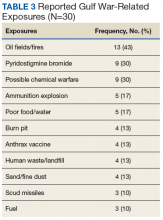

Respondents attributed several common chronic symptoms to deployment in the Gulf Wars (Table 2).

Most veterans surveyed were service connected for individual chronic symptoms. Some were service connected for systemic conditions such as fibromyalgia (FM), chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (5 veterans were connected for each condition). Three of the 30 veterans had been diagnosed with GWI—2 by past VA physicians and 1 by a physician at a GWI research center in another state. Of those 3, only 1 was service connected for the condition. Three respondents were not service connected at all.

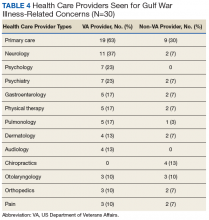

The most common VA HCPs seen were in primary care and neurology followed by psychiatry and psychology. Of non-VA HCPs, most respondents saw primary care providers (PCPs) followed by chiropractors (Table 4).

Before taking the Gulf War survey, a broad subjective question was posed. Respondents were asked whether VA HCPs were “supportive as you sought care for chronic postdeployment symptoms.” A majority of veterans reported that their VA HCPs were supportive. Reasons veterans gave for VA HCPs lack of support included feeling that HCPs did not believe them or trust their reported symptoms; did not care about their symptoms; refused to attribute their symptoms to Gulf War deployment; attributed symptoms to mental health issues; focused on doing things a certain way; or did not have the tools or information necessary to help.

Most non-VA HCPs were supportive. Reasons community HCPs were not supportive included “not looking at the whole picture,” not knowing veteran issues, not feeling comfortable with GWI, or not having much they could do.

Veterans were then asked whether they felt their HCPs were knowledgeable about GWI, and 13 respondents reported that their HCP was knowledgeable. Reasons respondents felt VA HCPs were not knowledgeable included denying that GWI exists, attributing symptoms to other conditions, not being aware of or familiar with GWI, needing education from the veteran, avoiding discussion about GWI or not caring to learn, or not knowing the latest research evidence to talk about GWI with authority. Compared with VA HCPs, veterans found community HCPs about half as likely to be knowledgeable about GWI. Many reported that community HCPs had not heard of GWI or had no knowledge about it.

Respondents also were asked what types of treatments they tried in order to typify the care received. The most common responses were pain medications, symptom-specific treatments, or “just putting up with it” (no treatment). Many patients were also self-medicating, trying lifestyle changes, or seeking alternative therapies.

Finally, respondents were asked on a scale of 0 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied), how satisfied they were with their overall care at the VA. The majority were satisfied with their overall care, with two-thirds very satisfied (5 of 5) or pretty satisfied (4 of 5). Only 3 (10%) were unsatisfied or very unsatisfied. Respondents had the following comments about their care: “They treat me like I am important;” “I am very thankful even though they cannot figure it out;” “They are doing the best they can with no answers and not enough help;” “[I know] it is still a work in progress.” A number of respondents were satisfied with some HCPs or care for some but not all of their symptoms. Reasons respondents were less satisfied included desiring answers, feeling they were not respected, or feeling that their concerns were not addressed.

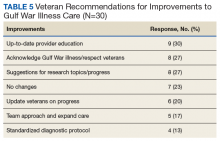

When asked for suggestions for improvement of GWI care, the most common response was providing up-to-date HCP education (Table 5).

Discussion

The veterans participating in this QI survey had similar demographics, symptomology, and exposures as did those in other studies.1-7 Therefore, improvements based on their responses are likely applicable to the health care of veterans experiencing GWI-associated symptoms at other VA health care systems as well.

Veterans with GWI can lose significant functional capacity and productivity due to their symptoms. The symptoms are chronic and have afflicted many Gulf War veterans for nearly 3 decades. Furthermore, the prevalence of GWI in Gulf War veterans continues to increase.5-7 These facts testify to the enormous health-related quality-of-life impact of GWI.

Veterans who meet the Kansas case definition for GWI were not diagnosed or service connected in a uniform manner. Only 3 of the 30 veterans in this study were given a unifying diagnosis that connected their chronic illness to Gulf War deployment. Under current guidelines, Gulf War veterans are able to receive compensation for chronic symptoms in 3 ways: (1) compensation for chronic unexplained symptoms existing for ≥ 6 months that appeared during active duty in the Southwest Asia theater or by December 31, 2021, and are ≥ 10% disabling; (2) the 1995 Persian Gulf War Veterans’ Act recognizes 3 multisymptom illnesses for which veterans can be service connected: FM, CFS, and functional GI disorders, including IBS; and (3) expansion to include any CMI of unknown etiology is underway. A uniform diagnostic protocol based on biomarkers and updated understanding of disease pathology would be helpful.

Respondents shared experiences that demonstrated perceived gaps in HCP support or knowledge. Overall, more respondents found their HCPs supportive. Many of the reasons respondents found HCPs unsupportive related to acknowledgment of symptoms. Also, more respondents found that both VA and non-VA HCPs lacked knowledge about GWI symptoms. These findings further highlight the need for HCP education within the VA and in community-based care.

The treatments tried by respondents also highlight potential areas for improvement. Most of the treatments were for pain; therefore, more involvement with pain clinics and specialists could be helpful. Symptom-specific medications also are appropriate, although only one-third of patients reported use. While medications are not necessarily markers of quality care, the fact that many patients self-medicate or go without treatment suggests that access to care could be improved. In 2014, the VA and the US Department of Defense (DoD) released the “VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Multisymptom Illness,” which recommended treatments for the global disease and specific symptoms.15

Since then, GWI research points to inflammatory and metabolic disease mechanisms.11-14,16 As the underlying pathophysiology is further elucidated, practice guidelines will need to be updated to include anti-inflammatory and antioxidant treatments used in practice for GWI and similar chronic systemic illnesses (eg, CFS, FM, and IBS).17-19

Randomized control trials are needed to determine the efficacy of such medications for the treatment of GWI. As new results emerge, disseminating and updating evidence-based guidelines in a coordinated manner will be required for veterans to receive appropriate treatment. Veterans also seek alternative or nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as physical therapy and diet changes. Improving access to integrative medicine, physical therapy, nutritionists, and other practitioners also could optimize veterans’ health and function.

HCP Education

The Gulf War veteran respondents who participated in the survey noted HCP education, research progress, and veteran inclusion as areas for improvement. Respondents requested dissemination of information on diagnosis and treatment of GWI for HCPs and updates on research and other actions. They suggested ways research could be more effective (such as subgrouping by exposure, which researchers have been doing) and could extend to veterans experiencing CMI from other conflicts as well.20 Respondents also recommended team approaches or centers of excellence in order to receive more comprehensive care.

An asset of VHA is the culture of QI and education. The VA Employee Education System previously produced “Caring for Gulf War I Veterans,” a systemwide training module.21 In 2014, updated clinical practice guidelines for GWI were provided by the VA and the DoD, including evidence for each recommendation. In 2016, the VA in collaboration with the IOM produced a report summarizing conclusions and recommendations regarding associations between health concerns and Gulf War deployment.22 A concise guide for HCPs caring for veterans with GWI, updated in 2018, is available.23 Updated treatment guidelines, based on evolving understanding of GWI pathophysiology, and continuing efforts to disseminate information will be essential.

Respondents most often presented to primary care, both within and outside of MVAHCS. Therefore, VA and community PCPs who see veterans should be equipped to recognize and diagnose GWI as well as be familiar with basic disease management and specialists whom they could refer their patients. Neurology was the second most common specialty seen by respondents. The most prominent symptoms of GWI are related to nervous system function in addition to evidence of underlying neuroinflammation.20 Veterans may present to a neurologist with a variety of concerns, such as cognitive issues, sleep problems, migraines and headaches, and pain. Neurologists could best manage treatments targeting common neurologic GWI symptoms and neuroinflammation, especially as new treatments are discovered.

The next 2 most common specialty services seen were psychiatry and psychology (7 responses for each). Five respondents reported mental health issues as part of their chronic postdeployment symptoms. Population-based studies have indicated that rates of PTSD in Gulf War veterans is 3% to 6%, much lower than the prevalence of GWI.8,20 The 2010 IOM study concluded that GWI symptoms cannot be ascribed to any known psychiatric disorder. Unfortunately, several surveyed veterans made it clear that they had been denied care due to HCPs attributing their symptoms solely to mental health issues. Therefore, psychiatrists and psychologists must be educated about GWI, mental health issues occurring in Gulf War veterans, and physiologic symptoms of GWI that may mimic or coincide with mental health issues. These HCPs also would be important to include in an interdisciplinary clinic for veterans with GWI.

Finally, respondents sought care from numerous other specialties, including gastroenterology, physical therapy, pulmonology, dermatology, and surgical subspecialties, such as orthopedics and otolaryngology. This wide range of specialists seen emphasizes the need for medical education, beginning in medical school. If provided education on GWI, these specialists would be able to treat veterans with GWI, know to look for updates on GWI management, or know to look for other common symptoms, such as chronic sinusitis in otolaryngology or recurring rashes in dermatology. We also recommend identifying HCPs in these specialties who could be part of an interdisciplinary clinic or be referrals for symptom management.

Protocol Implementation

HCP education and clinical care protocol implementation should be the initial focus of improving GWI management. A team of stakeholders within the different areas of MVAHCS, including education, HCPs, and administrative staff, will need to be developed. Reaching out to VA HCPs who have seen veterans with GWI will be an essential first step to equip them with updated education about the diagnosis and management of CMI. Providing integrated widespread education to current HCPs who are likely to encounter veterans with deployment-related CMI from the Gulf War, OND/OEF/OIF, or other deployments also will be necessary. Finally, educating medical trainees, including residents and medical students, will ensure continuous care for future veterans, post-9/11 veterans.

GWI presentations at medical grand rounds or at other medical community educational events could provide educational outlets. These events create face-to-face opportunities to discuss GWI/CMI education with HCPs, giving them the opportunity to offer feedback about their experiences and create relationships with other HCPs who have seen patients with GWI/CMI. At an educational event, a short postevent feedback form that indicates whether HCPs would like more information or get involved in a clinic for veterans with CMI could be included. This information would help identify key HCPs and areas within the local VA needing further improvements, such as creating a clinic for veterans with GWI.

Since 1946, the VA has worked with academic institutions to provide state-of-the-art health care to US veterans and train new HCPs to meet the health care needs of the nation. Every year, > 40,000 residents and 20,000 medical students receive medical training at VA facilities, making VA the largest single provider of medical education in the country. Therefore, providing detailed GWI/CMI education to medical students and residents as a standard part of the VA Talent Management System would be of value for all VA professionals.

GWI Clinics

Access to comprehensive care can be accomplished by organizing a clinic for veterans with GWI. The most likely effective location would be in primary care. PCPs who have seen veterans with GWI and/or expressed interest in learning more about GWI will be the initial point of contact. As the primary care service has connections to ancillary services, such as pharmacists, dieticians, psychologists, and social workers, organizing 1 day each week to see patients with GWI would improve care.

As the need for specialty care arises, the team also would need to identify specialists willing to receive referrals from HCPs of veterans with GWI. These specialists could be identified via feedback forms from educational events, surveys after an online educational training, or through relationships among VA physicians. As the clinic becomes established, it may be effective to have certain commonly seen specialists available in person, most likely neurology, psychiatry, gastroenterology, pulmonology, and dermatology. Also, relationships with a pain clinic, sleep medicine, and integrative medicine services should be established.

Measures of improvement in the veteran health care experience could include veterans’ perceptions of the supportiveness and knowledge of physicians about GWI as well as overall satisfaction. A follow-up survey on these measures of veterans involved in a GWI clinic and those not involved would be a way to determine whether these clinics better meet veterans’ needs and what additional QI is needed.

Conclusion

A significant number of Gulf War veterans experience chronic postdeployment symptoms that need to be better addressed. Physicians need to be equipped to recognize and manage GWI and similar postdeployment CMI among veterans of OEF/OIF/OND. We recommend creating an educational initiative about GWI among VA physicians and trainees, connecting physicians who see veterans with GWI, and establishing an interdisciplinary clinic with a referral system as the next steps to improve care for veterans. An additional goal would be to reach out to veteran networks to update them on GWI research, education, and available health care, as veterans are the essential stakeholders in the QI process.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses. Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans: Scientific Findings and Recommendations. https://www.va.gov/RAC-GWVI/docs/Committee_Documents/GWIandHealthofGWVeterans_RAC-GWVIReport_2008.pdf. Published November 2008. Accessed April 16, 2019.

2. Institute of Medicine. Gulf War and Health. Update of Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War. Vol 8. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

3. Fukuda K, Nisenbaum R, Stewart G, et al. Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. JAMA. 1998;280(11):981-988.

4. Steele L. Prevalence and patterns of Gulf War illness in Kansas veterans: association of symptoms with characteristics of person, place, and time of military service. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(10):992-1002.

5. Kang HK, Mahan CM, Lee KY, Magee CA, Murphy FM. Illnesses among United States veterans of the Gulf War: a population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42(5):491-501.

6. Kang HK, Li B, Mahan CM, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: a follow-up survey in 10 years. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):401-410.

7. Dursa EK, Barth SK, Schneiderman AI, Bossarte RM. Physical and mental health status of Gulf War and Gulf era veterans: results from a large population-based epidemiological study. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(1):41-46.

8. Institute of Medicine. Gulf War and Health: Treatment for Chronic Multisymptom Illness. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013.

9. Institute of Medicine. Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014.

10. United States Government Accountability Office. Gulf War illness: improvements needed for VA to better understand, process, and communicate decisions on claims. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/685562.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed April 16, 2019.

11. Johnson GJ, Slater BC, Leis LA, Rector TS, Bach RR. Blood biomarkers of chronic inflammation in Gulf War illness. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157855.

12. Reno J. Gulf War veterans still fighting serious health problems. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/gulf-war-veterans-still-fighting-serious-health-problems#1. Published June 17, 2016. Accessed April 16, 2019.

13. McAndrew LM, Helmer DA, Phillips LA, Chandler HK, Ray K, Quigley KS. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans report symptoms consistent with chronic multisymptom illness one year after deployment. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(1):59-70.

14. Steele L, Sastre A, Gerkovich MM, Cook MR. Complex factors in the etiology of Gulf War illness: wartime exposures and risk factors in veteran subgroups. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(1):112-118.

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Multisymptom Illness. Version 2.0. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MR/cmi/VADoDCMICPG2014.pdf. Published October 2014. Accessed April 22, 2019.

16. Koslik HJ, Hamilton G, Golomb BA. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Gulf War illness revealed by 31phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92887.

17. Brewer KL, Mainhart A, Meggs WJ. Double-blinded placebo-controlled cross-over pilot trial of naltrexone to treat Gulf War illness. Fatigue: Biomed Health Behav. 2018;6(3):132-140.

18. Golomb BA, Allison M, Koperski S, Koslik HJ, Devaraj S, Ritchie JB. Coenzyme Q10 benefits symptoms in Gulf War veterans: results of a randomized double-blind study. Neural Comput. 2014;26(11):2594-2651.

19. Weiduschat N, Mao X, Vu D, et al. N-acetylcysteine alleviates cortical glutathione deficit and improves symptoms in CFS: an in vivo validation study using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In: Proceedings from the IACFS/ME 12th Biennial Conference; October 27-30, 2016; Fort Lauderdale, FL. Abstract. http://iacfsme.org/ME-CFS-Primer-Education/News/IACFSME-2016-Program.aspx. Accessed April 22, 2019.

20. White RF, Steele L, O’Callaghan JP, et al. Recent research on Gulf War illness and other health problems in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: effects of toxicant exposures during deployment. Cortex. 2016;74:449-475.

21. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Caring for Gulf War I Veterans. http://www.ngwrc.net/PDF%20Files/caring-for-gulf-war.pdf. Published July 2011. Accessed April 15, 2019.

22. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Gulf War and Health. Update of Serving in the Gulf War. Vol 10. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016.

23. US Department of Veterans Affairs. War-Related Illness and Injury Study Center. Gulf War illness: a guide for veteran health care providers. https://www.warrelatedillness.va.gov/education/factsheets/gulf-war-illness-for-providers.pdf. Updated October 2018. Accessed April 16, 2019.

Many veterans of the Gulf War are experiencing deployment-related chronic illness, known as Gulf War illness (GWI). Symptoms of GWI include cognitive impairments (mood and memory), chronic fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, respiratory problems, and skin rashes.1-4 Three survey studies of the physical and mental health of a large cohort of Gulf War and Gulf era veterans, conducted by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Public Health, established the increased prevalence of GWI in the decades that followed the end of the conflict.5-7 Thus, GWI has become the signature adverse health-related outcome of the Gulf War. Quality improvement (QI) within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is needed in the diagnosis and treatment of GWI.

Background

GWI was first termed chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). According to the CDC-10 case definition, CMI in veterans of the 1990-1991 Gulf War is defined as having ≥ 1 symptoms lasting ≥ 6 months in at least 2 of 3 categories: fatigue, depressed mood and altered cognition, and musculoskeletal pain.3 The Kansas case definition of GWI is more specific and is defined as having moderate-to-severe symptoms that are unexplained by any other diagnosis, in at least 3 of 6 categories: fatigue/sleep, somatic pain, neurologic/cognition/mood, GI, respiratory, and skin.4 Although chronic unexplained symptoms have occurred after other modern conflicts, the prevalence of GWI among Gulf War veterans has proven higher than those of prior conflicts.8

The Persian Gulf War Veterans Act of 1998 and the Veterans Programs Enhancement Act of 1998 mandated studies by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) on the biologic and chemical exposures that may have contributed to illness in the Kuwaiti theater of operations.9 However, elucidating the etiology and underlying pathophysiology of GWI has been a major research challenge. In the absence of objective diagnostic measures, an understanding of the fundamental pathophysiology, evidence-based treatments, a single case definition, and definitive guidelines for health care providers (HCPs) for the diagnosis and management of GWI has not been produced. As a result, veterans with GWI have struggled for nearly 3 decades to find a consistent diagnosis of and an effective treatment for their condition.

According to a report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the VA approved only 17% of claims for compensation for veterans with GWI from 2011 to 2015, about one-third the level of approval for all other claimed disabilities.10 Although the VA applied GAO recommendations to improve the compensation process, many veterans consider that their illness is treated as psychosomatic in clinical practice, despite emerging evidence of GWI-associated biomarkers.11 Others think they have been forgotten due to their short 1-year period of service in the Gulf War.12 To realign research, guidelines, clinical care, and the health care experience of veterans with GWI, focused QI within VHA is urgently needed.

Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, and New Dawn (OEF/OIF/OND) are experiencing similar CMI symptoms. A study of US Army Reserve OEF/OIF veterans found that > 60% met the CDC-10 case definition for GWI 1-year postdeployment.13 Thus, CMI is emerging as a serious health problem for post-9/11 veterans. The evidence of postdeployment CMI among veterans of recent conflicts underscores the need to increase efforts at a national level, beginning with the VHA. This report includes a summary of Gulf War veterans’ experiences at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (MVAHCS) and a proposal for QI of MVAHCS processes focused on HCP education and clinical care.

Methods

To determine areas of GWI health care that needed QI at the MVAHCS, veterans with GWI were contacted for a telephone survey. These veterans had participated in the Gulf War Illness Inflammation Reduction Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NCT02506192). Therefore, all met the Kansas case definition for GWI.4 The aim of the survey was to characterize veterans’ experiences seeking health care for chronic postdeployment symptoms.

Sixty Gulf War veterans were contacted by telephone and invited to participate in a 15-minute survey about their experience seeking diagnosis and treatment for GWI. They were informed that the survey was voluntary and confidential, that it was not part of the research trial in which they had been enrolled, and that their participation would not affect compensation received from VA. Verbal consent was requested, and 30 veterans agreed to participate in the survey.

The survey included questions about the course of illness, disability and service connection status, HCPs seen, and suggestions for improvement in their care (Table 1).

Results

Of the 30 veterans who participated in the survey, most were male with only 2 female veterans. This proportion of female veterans (7%) is similar to the overall percentage of female veterans (6.7%) of the first Gulf War.2 Ages ranged from 46 to 66 years with a mean age of 53. Mean duration of illness, defined as time elapsed since perceived onset of chronic systemic symptoms during or after deployment, was 22.8 years, with a range of 4 to 27 years. Most respondents reported symptom onset within a few years after the end of the conflict, while a few reported the onset within weeks of arriving in the Kuwaiti theater of operations. A little more than half the respondents considered themselves disabled due to their symptoms, while one-third reported losing the ability to work due to symptoms. Respondents described needing to reduce hours, retire early, or stop working altogether because of their symptoms.

Respondents attributed several common chronic symptoms to deployment in the Gulf Wars (Table 2).

Most veterans surveyed were service connected for individual chronic symptoms. Some were service connected for systemic conditions such as fibromyalgia (FM), chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (5 veterans were connected for each condition). Three of the 30 veterans had been diagnosed with GWI—2 by past VA physicians and 1 by a physician at a GWI research center in another state. Of those 3, only 1 was service connected for the condition. Three respondents were not service connected at all.

The most common VA HCPs seen were in primary care and neurology followed by psychiatry and psychology. Of non-VA HCPs, most respondents saw primary care providers (PCPs) followed by chiropractors (Table 4).

Before taking the Gulf War survey, a broad subjective question was posed. Respondents were asked whether VA HCPs were “supportive as you sought care for chronic postdeployment symptoms.” A majority of veterans reported that their VA HCPs were supportive. Reasons veterans gave for VA HCPs lack of support included feeling that HCPs did not believe them or trust their reported symptoms; did not care about their symptoms; refused to attribute their symptoms to Gulf War deployment; attributed symptoms to mental health issues; focused on doing things a certain way; or did not have the tools or information necessary to help.

Most non-VA HCPs were supportive. Reasons community HCPs were not supportive included “not looking at the whole picture,” not knowing veteran issues, not feeling comfortable with GWI, or not having much they could do.

Veterans were then asked whether they felt their HCPs were knowledgeable about GWI, and 13 respondents reported that their HCP was knowledgeable. Reasons respondents felt VA HCPs were not knowledgeable included denying that GWI exists, attributing symptoms to other conditions, not being aware of or familiar with GWI, needing education from the veteran, avoiding discussion about GWI or not caring to learn, or not knowing the latest research evidence to talk about GWI with authority. Compared with VA HCPs, veterans found community HCPs about half as likely to be knowledgeable about GWI. Many reported that community HCPs had not heard of GWI or had no knowledge about it.

Respondents also were asked what types of treatments they tried in order to typify the care received. The most common responses were pain medications, symptom-specific treatments, or “just putting up with it” (no treatment). Many patients were also self-medicating, trying lifestyle changes, or seeking alternative therapies.

Finally, respondents were asked on a scale of 0 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied), how satisfied they were with their overall care at the VA. The majority were satisfied with their overall care, with two-thirds very satisfied (5 of 5) or pretty satisfied (4 of 5). Only 3 (10%) were unsatisfied or very unsatisfied. Respondents had the following comments about their care: “They treat me like I am important;” “I am very thankful even though they cannot figure it out;” “They are doing the best they can with no answers and not enough help;” “[I know] it is still a work in progress.” A number of respondents were satisfied with some HCPs or care for some but not all of their symptoms. Reasons respondents were less satisfied included desiring answers, feeling they were not respected, or feeling that their concerns were not addressed.

When asked for suggestions for improvement of GWI care, the most common response was providing up-to-date HCP education (Table 5).

Discussion

The veterans participating in this QI survey had similar demographics, symptomology, and exposures as did those in other studies.1-7 Therefore, improvements based on their responses are likely applicable to the health care of veterans experiencing GWI-associated symptoms at other VA health care systems as well.

Veterans with GWI can lose significant functional capacity and productivity due to their symptoms. The symptoms are chronic and have afflicted many Gulf War veterans for nearly 3 decades. Furthermore, the prevalence of GWI in Gulf War veterans continues to increase.5-7 These facts testify to the enormous health-related quality-of-life impact of GWI.

Veterans who meet the Kansas case definition for GWI were not diagnosed or service connected in a uniform manner. Only 3 of the 30 veterans in this study were given a unifying diagnosis that connected their chronic illness to Gulf War deployment. Under current guidelines, Gulf War veterans are able to receive compensation for chronic symptoms in 3 ways: (1) compensation for chronic unexplained symptoms existing for ≥ 6 months that appeared during active duty in the Southwest Asia theater or by December 31, 2021, and are ≥ 10% disabling; (2) the 1995 Persian Gulf War Veterans’ Act recognizes 3 multisymptom illnesses for which veterans can be service connected: FM, CFS, and functional GI disorders, including IBS; and (3) expansion to include any CMI of unknown etiology is underway. A uniform diagnostic protocol based on biomarkers and updated understanding of disease pathology would be helpful.

Respondents shared experiences that demonstrated perceived gaps in HCP support or knowledge. Overall, more respondents found their HCPs supportive. Many of the reasons respondents found HCPs unsupportive related to acknowledgment of symptoms. Also, more respondents found that both VA and non-VA HCPs lacked knowledge about GWI symptoms. These findings further highlight the need for HCP education within the VA and in community-based care.

The treatments tried by respondents also highlight potential areas for improvement. Most of the treatments were for pain; therefore, more involvement with pain clinics and specialists could be helpful. Symptom-specific medications also are appropriate, although only one-third of patients reported use. While medications are not necessarily markers of quality care, the fact that many patients self-medicate or go without treatment suggests that access to care could be improved. In 2014, the VA and the US Department of Defense (DoD) released the “VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Multisymptom Illness,” which recommended treatments for the global disease and specific symptoms.15

Since then, GWI research points to inflammatory and metabolic disease mechanisms.11-14,16 As the underlying pathophysiology is further elucidated, practice guidelines will need to be updated to include anti-inflammatory and antioxidant treatments used in practice for GWI and similar chronic systemic illnesses (eg, CFS, FM, and IBS).17-19

Randomized control trials are needed to determine the efficacy of such medications for the treatment of GWI. As new results emerge, disseminating and updating evidence-based guidelines in a coordinated manner will be required for veterans to receive appropriate treatment. Veterans also seek alternative or nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as physical therapy and diet changes. Improving access to integrative medicine, physical therapy, nutritionists, and other practitioners also could optimize veterans’ health and function.

HCP Education

The Gulf War veteran respondents who participated in the survey noted HCP education, research progress, and veteran inclusion as areas for improvement. Respondents requested dissemination of information on diagnosis and treatment of GWI for HCPs and updates on research and other actions. They suggested ways research could be more effective (such as subgrouping by exposure, which researchers have been doing) and could extend to veterans experiencing CMI from other conflicts as well.20 Respondents also recommended team approaches or centers of excellence in order to receive more comprehensive care.

An asset of VHA is the culture of QI and education. The VA Employee Education System previously produced “Caring for Gulf War I Veterans,” a systemwide training module.21 In 2014, updated clinical practice guidelines for GWI were provided by the VA and the DoD, including evidence for each recommendation. In 2016, the VA in collaboration with the IOM produced a report summarizing conclusions and recommendations regarding associations between health concerns and Gulf War deployment.22 A concise guide for HCPs caring for veterans with GWI, updated in 2018, is available.23 Updated treatment guidelines, based on evolving understanding of GWI pathophysiology, and continuing efforts to disseminate information will be essential.

Respondents most often presented to primary care, both within and outside of MVAHCS. Therefore, VA and community PCPs who see veterans should be equipped to recognize and diagnose GWI as well as be familiar with basic disease management and specialists whom they could refer their patients. Neurology was the second most common specialty seen by respondents. The most prominent symptoms of GWI are related to nervous system function in addition to evidence of underlying neuroinflammation.20 Veterans may present to a neurologist with a variety of concerns, such as cognitive issues, sleep problems, migraines and headaches, and pain. Neurologists could best manage treatments targeting common neurologic GWI symptoms and neuroinflammation, especially as new treatments are discovered.

The next 2 most common specialty services seen were psychiatry and psychology (7 responses for each). Five respondents reported mental health issues as part of their chronic postdeployment symptoms. Population-based studies have indicated that rates of PTSD in Gulf War veterans is 3% to 6%, much lower than the prevalence of GWI.8,20 The 2010 IOM study concluded that GWI symptoms cannot be ascribed to any known psychiatric disorder. Unfortunately, several surveyed veterans made it clear that they had been denied care due to HCPs attributing their symptoms solely to mental health issues. Therefore, psychiatrists and psychologists must be educated about GWI, mental health issues occurring in Gulf War veterans, and physiologic symptoms of GWI that may mimic or coincide with mental health issues. These HCPs also would be important to include in an interdisciplinary clinic for veterans with GWI.

Finally, respondents sought care from numerous other specialties, including gastroenterology, physical therapy, pulmonology, dermatology, and surgical subspecialties, such as orthopedics and otolaryngology. This wide range of specialists seen emphasizes the need for medical education, beginning in medical school. If provided education on GWI, these specialists would be able to treat veterans with GWI, know to look for updates on GWI management, or know to look for other common symptoms, such as chronic sinusitis in otolaryngology or recurring rashes in dermatology. We also recommend identifying HCPs in these specialties who could be part of an interdisciplinary clinic or be referrals for symptom management.

Protocol Implementation

HCP education and clinical care protocol implementation should be the initial focus of improving GWI management. A team of stakeholders within the different areas of MVAHCS, including education, HCPs, and administrative staff, will need to be developed. Reaching out to VA HCPs who have seen veterans with GWI will be an essential first step to equip them with updated education about the diagnosis and management of CMI. Providing integrated widespread education to current HCPs who are likely to encounter veterans with deployment-related CMI from the Gulf War, OND/OEF/OIF, or other deployments also will be necessary. Finally, educating medical trainees, including residents and medical students, will ensure continuous care for future veterans, post-9/11 veterans.

GWI presentations at medical grand rounds or at other medical community educational events could provide educational outlets. These events create face-to-face opportunities to discuss GWI/CMI education with HCPs, giving them the opportunity to offer feedback about their experiences and create relationships with other HCPs who have seen patients with GWI/CMI. At an educational event, a short postevent feedback form that indicates whether HCPs would like more information or get involved in a clinic for veterans with CMI could be included. This information would help identify key HCPs and areas within the local VA needing further improvements, such as creating a clinic for veterans with GWI.

Since 1946, the VA has worked with academic institutions to provide state-of-the-art health care to US veterans and train new HCPs to meet the health care needs of the nation. Every year, > 40,000 residents and 20,000 medical students receive medical training at VA facilities, making VA the largest single provider of medical education in the country. Therefore, providing detailed GWI/CMI education to medical students and residents as a standard part of the VA Talent Management System would be of value for all VA professionals.

GWI Clinics

Access to comprehensive care can be accomplished by organizing a clinic for veterans with GWI. The most likely effective location would be in primary care. PCPs who have seen veterans with GWI and/or expressed interest in learning more about GWI will be the initial point of contact. As the primary care service has connections to ancillary services, such as pharmacists, dieticians, psychologists, and social workers, organizing 1 day each week to see patients with GWI would improve care.

As the need for specialty care arises, the team also would need to identify specialists willing to receive referrals from HCPs of veterans with GWI. These specialists could be identified via feedback forms from educational events, surveys after an online educational training, or through relationships among VA physicians. As the clinic becomes established, it may be effective to have certain commonly seen specialists available in person, most likely neurology, psychiatry, gastroenterology, pulmonology, and dermatology. Also, relationships with a pain clinic, sleep medicine, and integrative medicine services should be established.

Measures of improvement in the veteran health care experience could include veterans’ perceptions of the supportiveness and knowledge of physicians about GWI as well as overall satisfaction. A follow-up survey on these measures of veterans involved in a GWI clinic and those not involved would be a way to determine whether these clinics better meet veterans’ needs and what additional QI is needed.

Conclusion

A significant number of Gulf War veterans experience chronic postdeployment symptoms that need to be better addressed. Physicians need to be equipped to recognize and manage GWI and similar postdeployment CMI among veterans of OEF/OIF/OND. We recommend creating an educational initiative about GWI among VA physicians and trainees, connecting physicians who see veterans with GWI, and establishing an interdisciplinary clinic with a referral system as the next steps to improve care for veterans. An additional goal would be to reach out to veteran networks to update them on GWI research, education, and available health care, as veterans are the essential stakeholders in the QI process.

Many veterans of the Gulf War are experiencing deployment-related chronic illness, known as Gulf War illness (GWI). Symptoms of GWI include cognitive impairments (mood and memory), chronic fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, respiratory problems, and skin rashes.1-4 Three survey studies of the physical and mental health of a large cohort of Gulf War and Gulf era veterans, conducted by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Public Health, established the increased prevalence of GWI in the decades that followed the end of the conflict.5-7 Thus, GWI has become the signature adverse health-related outcome of the Gulf War. Quality improvement (QI) within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is needed in the diagnosis and treatment of GWI.

Background

GWI was first termed chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). According to the CDC-10 case definition, CMI in veterans of the 1990-1991 Gulf War is defined as having ≥ 1 symptoms lasting ≥ 6 months in at least 2 of 3 categories: fatigue, depressed mood and altered cognition, and musculoskeletal pain.3 The Kansas case definition of GWI is more specific and is defined as having moderate-to-severe symptoms that are unexplained by any other diagnosis, in at least 3 of 6 categories: fatigue/sleep, somatic pain, neurologic/cognition/mood, GI, respiratory, and skin.4 Although chronic unexplained symptoms have occurred after other modern conflicts, the prevalence of GWI among Gulf War veterans has proven higher than those of prior conflicts.8

The Persian Gulf War Veterans Act of 1998 and the Veterans Programs Enhancement Act of 1998 mandated studies by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) on the biologic and chemical exposures that may have contributed to illness in the Kuwaiti theater of operations.9 However, elucidating the etiology and underlying pathophysiology of GWI has been a major research challenge. In the absence of objective diagnostic measures, an understanding of the fundamental pathophysiology, evidence-based treatments, a single case definition, and definitive guidelines for health care providers (HCPs) for the diagnosis and management of GWI has not been produced. As a result, veterans with GWI have struggled for nearly 3 decades to find a consistent diagnosis of and an effective treatment for their condition.

According to a report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the VA approved only 17% of claims for compensation for veterans with GWI from 2011 to 2015, about one-third the level of approval for all other claimed disabilities.10 Although the VA applied GAO recommendations to improve the compensation process, many veterans consider that their illness is treated as psychosomatic in clinical practice, despite emerging evidence of GWI-associated biomarkers.11 Others think they have been forgotten due to their short 1-year period of service in the Gulf War.12 To realign research, guidelines, clinical care, and the health care experience of veterans with GWI, focused QI within VHA is urgently needed.

Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, and New Dawn (OEF/OIF/OND) are experiencing similar CMI symptoms. A study of US Army Reserve OEF/OIF veterans found that > 60% met the CDC-10 case definition for GWI 1-year postdeployment.13 Thus, CMI is emerging as a serious health problem for post-9/11 veterans. The evidence of postdeployment CMI among veterans of recent conflicts underscores the need to increase efforts at a national level, beginning with the VHA. This report includes a summary of Gulf War veterans’ experiences at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (MVAHCS) and a proposal for QI of MVAHCS processes focused on HCP education and clinical care.

Methods

To determine areas of GWI health care that needed QI at the MVAHCS, veterans with GWI were contacted for a telephone survey. These veterans had participated in the Gulf War Illness Inflammation Reduction Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NCT02506192). Therefore, all met the Kansas case definition for GWI.4 The aim of the survey was to characterize veterans’ experiences seeking health care for chronic postdeployment symptoms.

Sixty Gulf War veterans were contacted by telephone and invited to participate in a 15-minute survey about their experience seeking diagnosis and treatment for GWI. They were informed that the survey was voluntary and confidential, that it was not part of the research trial in which they had been enrolled, and that their participation would not affect compensation received from VA. Verbal consent was requested, and 30 veterans agreed to participate in the survey.

The survey included questions about the course of illness, disability and service connection status, HCPs seen, and suggestions for improvement in their care (Table 1).

Results

Of the 30 veterans who participated in the survey, most were male with only 2 female veterans. This proportion of female veterans (7%) is similar to the overall percentage of female veterans (6.7%) of the first Gulf War.2 Ages ranged from 46 to 66 years with a mean age of 53. Mean duration of illness, defined as time elapsed since perceived onset of chronic systemic symptoms during or after deployment, was 22.8 years, with a range of 4 to 27 years. Most respondents reported symptom onset within a few years after the end of the conflict, while a few reported the onset within weeks of arriving in the Kuwaiti theater of operations. A little more than half the respondents considered themselves disabled due to their symptoms, while one-third reported losing the ability to work due to symptoms. Respondents described needing to reduce hours, retire early, or stop working altogether because of their symptoms.

Respondents attributed several common chronic symptoms to deployment in the Gulf Wars (Table 2).

Most veterans surveyed were service connected for individual chronic symptoms. Some were service connected for systemic conditions such as fibromyalgia (FM), chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (5 veterans were connected for each condition). Three of the 30 veterans had been diagnosed with GWI—2 by past VA physicians and 1 by a physician at a GWI research center in another state. Of those 3, only 1 was service connected for the condition. Three respondents were not service connected at all.

The most common VA HCPs seen were in primary care and neurology followed by psychiatry and psychology. Of non-VA HCPs, most respondents saw primary care providers (PCPs) followed by chiropractors (Table 4).

Before taking the Gulf War survey, a broad subjective question was posed. Respondents were asked whether VA HCPs were “supportive as you sought care for chronic postdeployment symptoms.” A majority of veterans reported that their VA HCPs were supportive. Reasons veterans gave for VA HCPs lack of support included feeling that HCPs did not believe them or trust their reported symptoms; did not care about their symptoms; refused to attribute their symptoms to Gulf War deployment; attributed symptoms to mental health issues; focused on doing things a certain way; or did not have the tools or information necessary to help.

Most non-VA HCPs were supportive. Reasons community HCPs were not supportive included “not looking at the whole picture,” not knowing veteran issues, not feeling comfortable with GWI, or not having much they could do.

Veterans were then asked whether they felt their HCPs were knowledgeable about GWI, and 13 respondents reported that their HCP was knowledgeable. Reasons respondents felt VA HCPs were not knowledgeable included denying that GWI exists, attributing symptoms to other conditions, not being aware of or familiar with GWI, needing education from the veteran, avoiding discussion about GWI or not caring to learn, or not knowing the latest research evidence to talk about GWI with authority. Compared with VA HCPs, veterans found community HCPs about half as likely to be knowledgeable about GWI. Many reported that community HCPs had not heard of GWI or had no knowledge about it.

Respondents also were asked what types of treatments they tried in order to typify the care received. The most common responses were pain medications, symptom-specific treatments, or “just putting up with it” (no treatment). Many patients were also self-medicating, trying lifestyle changes, or seeking alternative therapies.

Finally, respondents were asked on a scale of 0 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied), how satisfied they were with their overall care at the VA. The majority were satisfied with their overall care, with two-thirds very satisfied (5 of 5) or pretty satisfied (4 of 5). Only 3 (10%) were unsatisfied or very unsatisfied. Respondents had the following comments about their care: “They treat me like I am important;” “I am very thankful even though they cannot figure it out;” “They are doing the best they can with no answers and not enough help;” “[I know] it is still a work in progress.” A number of respondents were satisfied with some HCPs or care for some but not all of their symptoms. Reasons respondents were less satisfied included desiring answers, feeling they were not respected, or feeling that their concerns were not addressed.

When asked for suggestions for improvement of GWI care, the most common response was providing up-to-date HCP education (Table 5).

Discussion

The veterans participating in this QI survey had similar demographics, symptomology, and exposures as did those in other studies.1-7 Therefore, improvements based on their responses are likely applicable to the health care of veterans experiencing GWI-associated symptoms at other VA health care systems as well.

Veterans with GWI can lose significant functional capacity and productivity due to their symptoms. The symptoms are chronic and have afflicted many Gulf War veterans for nearly 3 decades. Furthermore, the prevalence of GWI in Gulf War veterans continues to increase.5-7 These facts testify to the enormous health-related quality-of-life impact of GWI.

Veterans who meet the Kansas case definition for GWI were not diagnosed or service connected in a uniform manner. Only 3 of the 30 veterans in this study were given a unifying diagnosis that connected their chronic illness to Gulf War deployment. Under current guidelines, Gulf War veterans are able to receive compensation for chronic symptoms in 3 ways: (1) compensation for chronic unexplained symptoms existing for ≥ 6 months that appeared during active duty in the Southwest Asia theater or by December 31, 2021, and are ≥ 10% disabling; (2) the 1995 Persian Gulf War Veterans’ Act recognizes 3 multisymptom illnesses for which veterans can be service connected: FM, CFS, and functional GI disorders, including IBS; and (3) expansion to include any CMI of unknown etiology is underway. A uniform diagnostic protocol based on biomarkers and updated understanding of disease pathology would be helpful.

Respondents shared experiences that demonstrated perceived gaps in HCP support or knowledge. Overall, more respondents found their HCPs supportive. Many of the reasons respondents found HCPs unsupportive related to acknowledgment of symptoms. Also, more respondents found that both VA and non-VA HCPs lacked knowledge about GWI symptoms. These findings further highlight the need for HCP education within the VA and in community-based care.

The treatments tried by respondents also highlight potential areas for improvement. Most of the treatments were for pain; therefore, more involvement with pain clinics and specialists could be helpful. Symptom-specific medications also are appropriate, although only one-third of patients reported use. While medications are not necessarily markers of quality care, the fact that many patients self-medicate or go without treatment suggests that access to care could be improved. In 2014, the VA and the US Department of Defense (DoD) released the “VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Multisymptom Illness,” which recommended treatments for the global disease and specific symptoms.15

Since then, GWI research points to inflammatory and metabolic disease mechanisms.11-14,16 As the underlying pathophysiology is further elucidated, practice guidelines will need to be updated to include anti-inflammatory and antioxidant treatments used in practice for GWI and similar chronic systemic illnesses (eg, CFS, FM, and IBS).17-19

Randomized control trials are needed to determine the efficacy of such medications for the treatment of GWI. As new results emerge, disseminating and updating evidence-based guidelines in a coordinated manner will be required for veterans to receive appropriate treatment. Veterans also seek alternative or nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as physical therapy and diet changes. Improving access to integrative medicine, physical therapy, nutritionists, and other practitioners also could optimize veterans’ health and function.

HCP Education

The Gulf War veteran respondents who participated in the survey noted HCP education, research progress, and veteran inclusion as areas for improvement. Respondents requested dissemination of information on diagnosis and treatment of GWI for HCPs and updates on research and other actions. They suggested ways research could be more effective (such as subgrouping by exposure, which researchers have been doing) and could extend to veterans experiencing CMI from other conflicts as well.20 Respondents also recommended team approaches or centers of excellence in order to receive more comprehensive care.

An asset of VHA is the culture of QI and education. The VA Employee Education System previously produced “Caring for Gulf War I Veterans,” a systemwide training module.21 In 2014, updated clinical practice guidelines for GWI were provided by the VA and the DoD, including evidence for each recommendation. In 2016, the VA in collaboration with the IOM produced a report summarizing conclusions and recommendations regarding associations between health concerns and Gulf War deployment.22 A concise guide for HCPs caring for veterans with GWI, updated in 2018, is available.23 Updated treatment guidelines, based on evolving understanding of GWI pathophysiology, and continuing efforts to disseminate information will be essential.

Respondents most often presented to primary care, both within and outside of MVAHCS. Therefore, VA and community PCPs who see veterans should be equipped to recognize and diagnose GWI as well as be familiar with basic disease management and specialists whom they could refer their patients. Neurology was the second most common specialty seen by respondents. The most prominent symptoms of GWI are related to nervous system function in addition to evidence of underlying neuroinflammation.20 Veterans may present to a neurologist with a variety of concerns, such as cognitive issues, sleep problems, migraines and headaches, and pain. Neurologists could best manage treatments targeting common neurologic GWI symptoms and neuroinflammation, especially as new treatments are discovered.

The next 2 most common specialty services seen were psychiatry and psychology (7 responses for each). Five respondents reported mental health issues as part of their chronic postdeployment symptoms. Population-based studies have indicated that rates of PTSD in Gulf War veterans is 3% to 6%, much lower than the prevalence of GWI.8,20 The 2010 IOM study concluded that GWI symptoms cannot be ascribed to any known psychiatric disorder. Unfortunately, several surveyed veterans made it clear that they had been denied care due to HCPs attributing their symptoms solely to mental health issues. Therefore, psychiatrists and psychologists must be educated about GWI, mental health issues occurring in Gulf War veterans, and physiologic symptoms of GWI that may mimic or coincide with mental health issues. These HCPs also would be important to include in an interdisciplinary clinic for veterans with GWI.

Finally, respondents sought care from numerous other specialties, including gastroenterology, physical therapy, pulmonology, dermatology, and surgical subspecialties, such as orthopedics and otolaryngology. This wide range of specialists seen emphasizes the need for medical education, beginning in medical school. If provided education on GWI, these specialists would be able to treat veterans with GWI, know to look for updates on GWI management, or know to look for other common symptoms, such as chronic sinusitis in otolaryngology or recurring rashes in dermatology. We also recommend identifying HCPs in these specialties who could be part of an interdisciplinary clinic or be referrals for symptom management.

Protocol Implementation

HCP education and clinical care protocol implementation should be the initial focus of improving GWI management. A team of stakeholders within the different areas of MVAHCS, including education, HCPs, and administrative staff, will need to be developed. Reaching out to VA HCPs who have seen veterans with GWI will be an essential first step to equip them with updated education about the diagnosis and management of CMI. Providing integrated widespread education to current HCPs who are likely to encounter veterans with deployment-related CMI from the Gulf War, OND/OEF/OIF, or other deployments also will be necessary. Finally, educating medical trainees, including residents and medical students, will ensure continuous care for future veterans, post-9/11 veterans.

GWI presentations at medical grand rounds or at other medical community educational events could provide educational outlets. These events create face-to-face opportunities to discuss GWI/CMI education with HCPs, giving them the opportunity to offer feedback about their experiences and create relationships with other HCPs who have seen patients with GWI/CMI. At an educational event, a short postevent feedback form that indicates whether HCPs would like more information or get involved in a clinic for veterans with CMI could be included. This information would help identify key HCPs and areas within the local VA needing further improvements, such as creating a clinic for veterans with GWI.

Since 1946, the VA has worked with academic institutions to provide state-of-the-art health care to US veterans and train new HCPs to meet the health care needs of the nation. Every year, > 40,000 residents and 20,000 medical students receive medical training at VA facilities, making VA the largest single provider of medical education in the country. Therefore, providing detailed GWI/CMI education to medical students and residents as a standard part of the VA Talent Management System would be of value for all VA professionals.

GWI Clinics

Access to comprehensive care can be accomplished by organizing a clinic for veterans with GWI. The most likely effective location would be in primary care. PCPs who have seen veterans with GWI and/or expressed interest in learning more about GWI will be the initial point of contact. As the primary care service has connections to ancillary services, such as pharmacists, dieticians, psychologists, and social workers, organizing 1 day each week to see patients with GWI would improve care.

As the need for specialty care arises, the team also would need to identify specialists willing to receive referrals from HCPs of veterans with GWI. These specialists could be identified via feedback forms from educational events, surveys after an online educational training, or through relationships among VA physicians. As the clinic becomes established, it may be effective to have certain commonly seen specialists available in person, most likely neurology, psychiatry, gastroenterology, pulmonology, and dermatology. Also, relationships with a pain clinic, sleep medicine, and integrative medicine services should be established.

Measures of improvement in the veteran health care experience could include veterans’ perceptions of the supportiveness and knowledge of physicians about GWI as well as overall satisfaction. A follow-up survey on these measures of veterans involved in a GWI clinic and those not involved would be a way to determine whether these clinics better meet veterans’ needs and what additional QI is needed.

Conclusion

A significant number of Gulf War veterans experience chronic postdeployment symptoms that need to be better addressed. Physicians need to be equipped to recognize and manage GWI and similar postdeployment CMI among veterans of OEF/OIF/OND. We recommend creating an educational initiative about GWI among VA physicians and trainees, connecting physicians who see veterans with GWI, and establishing an interdisciplinary clinic with a referral system as the next steps to improve care for veterans. An additional goal would be to reach out to veteran networks to update them on GWI research, education, and available health care, as veterans are the essential stakeholders in the QI process.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses. Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans: Scientific Findings and Recommendations. https://www.va.gov/RAC-GWVI/docs/Committee_Documents/GWIandHealthofGWVeterans_RAC-GWVIReport_2008.pdf. Published November 2008. Accessed April 16, 2019.

2. Institute of Medicine. Gulf War and Health. Update of Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War. Vol 8. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

3. Fukuda K, Nisenbaum R, Stewart G, et al. Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. JAMA. 1998;280(11):981-988.

4. Steele L. Prevalence and patterns of Gulf War illness in Kansas veterans: association of symptoms with characteristics of person, place, and time of military service. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(10):992-1002.

5. Kang HK, Mahan CM, Lee KY, Magee CA, Murphy FM. Illnesses among United States veterans of the Gulf War: a population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42(5):491-501.

6. Kang HK, Li B, Mahan CM, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: a follow-up survey in 10 years. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):401-410.

7. Dursa EK, Barth SK, Schneiderman AI, Bossarte RM. Physical and mental health status of Gulf War and Gulf era veterans: results from a large population-based epidemiological study. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(1):41-46.

8. Institute of Medicine. Gulf War and Health: Treatment for Chronic Multisymptom Illness. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013.

9. Institute of Medicine. Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014.

10. United States Government Accountability Office. Gulf War illness: improvements needed for VA to better understand, process, and communicate decisions on claims. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/685562.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed April 16, 2019.

11. Johnson GJ, Slater BC, Leis LA, Rector TS, Bach RR. Blood biomarkers of chronic inflammation in Gulf War illness. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157855.

12. Reno J. Gulf War veterans still fighting serious health problems. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/gulf-war-veterans-still-fighting-serious-health-problems#1. Published June 17, 2016. Accessed April 16, 2019.

13. McAndrew LM, Helmer DA, Phillips LA, Chandler HK, Ray K, Quigley KS. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans report symptoms consistent with chronic multisymptom illness one year after deployment. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(1):59-70.

14. Steele L, Sastre A, Gerkovich MM, Cook MR. Complex factors in the etiology of Gulf War illness: wartime exposures and risk factors in veteran subgroups. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(1):112-118.

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Multisymptom Illness. Version 2.0. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MR/cmi/VADoDCMICPG2014.pdf. Published October 2014. Accessed April 22, 2019.

16. Koslik HJ, Hamilton G, Golomb BA. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Gulf War illness revealed by 31phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92887.

17. Brewer KL, Mainhart A, Meggs WJ. Double-blinded placebo-controlled cross-over pilot trial of naltrexone to treat Gulf War illness. Fatigue: Biomed Health Behav. 2018;6(3):132-140.

18. Golomb BA, Allison M, Koperski S, Koslik HJ, Devaraj S, Ritchie JB. Coenzyme Q10 benefits symptoms in Gulf War veterans: results of a randomized double-blind study. Neural Comput. 2014;26(11):2594-2651.

19. Weiduschat N, Mao X, Vu D, et al. N-acetylcysteine alleviates cortical glutathione deficit and improves symptoms in CFS: an in vivo validation study using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In: Proceedings from the IACFS/ME 12th Biennial Conference; October 27-30, 2016; Fort Lauderdale, FL. Abstract. http://iacfsme.org/ME-CFS-Primer-Education/News/IACFSME-2016-Program.aspx. Accessed April 22, 2019.

20. White RF, Steele L, O’Callaghan JP, et al. Recent research on Gulf War illness and other health problems in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: effects of toxicant exposures during deployment. Cortex. 2016;74:449-475.

21. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Caring for Gulf War I Veterans. http://www.ngwrc.net/PDF%20Files/caring-for-gulf-war.pdf. Published July 2011. Accessed April 15, 2019.

22. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Gulf War and Health. Update of Serving in the Gulf War. Vol 10. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016.

23. US Department of Veterans Affairs. War-Related Illness and Injury Study Center. Gulf War illness: a guide for veteran health care providers. https://www.warrelatedillness.va.gov/education/factsheets/gulf-war-illness-for-providers.pdf. Updated October 2018. Accessed April 16, 2019.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses. Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans: Scientific Findings and Recommendations. https://www.va.gov/RAC-GWVI/docs/Committee_Documents/GWIandHealthofGWVeterans_RAC-GWVIReport_2008.pdf. Published November 2008. Accessed April 16, 2019.

2. Institute of Medicine. Gulf War and Health. Update of Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War. Vol 8. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

3. Fukuda K, Nisenbaum R, Stewart G, et al. Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. JAMA. 1998;280(11):981-988.

4. Steele L. Prevalence and patterns of Gulf War illness in Kansas veterans: association of symptoms with characteristics of person, place, and time of military service. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(10):992-1002.

5. Kang HK, Mahan CM, Lee KY, Magee CA, Murphy FM. Illnesses among United States veterans of the Gulf War: a population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42(5):491-501.

6. Kang HK, Li B, Mahan CM, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: a follow-up survey in 10 years. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):401-410.

7. Dursa EK, Barth SK, Schneiderman AI, Bossarte RM. Physical and mental health status of Gulf War and Gulf era veterans: results from a large population-based epidemiological study. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(1):41-46.

8. Institute of Medicine. Gulf War and Health: Treatment for Chronic Multisymptom Illness. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013.

9. Institute of Medicine. Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014.

10. United States Government Accountability Office. Gulf War illness: improvements needed for VA to better understand, process, and communicate decisions on claims. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/685562.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed April 16, 2019.

11. Johnson GJ, Slater BC, Leis LA, Rector TS, Bach RR. Blood biomarkers of chronic inflammation in Gulf War illness. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157855.

12. Reno J. Gulf War veterans still fighting serious health problems. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/gulf-war-veterans-still-fighting-serious-health-problems#1. Published June 17, 2016. Accessed April 16, 2019.

13. McAndrew LM, Helmer DA, Phillips LA, Chandler HK, Ray K, Quigley KS. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans report symptoms consistent with chronic multisymptom illness one year after deployment. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(1):59-70.

14. Steele L, Sastre A, Gerkovich MM, Cook MR. Complex factors in the etiology of Gulf War illness: wartime exposures and risk factors in veteran subgroups. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(1):112-118.

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Multisymptom Illness. Version 2.0. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MR/cmi/VADoDCMICPG2014.pdf. Published October 2014. Accessed April 22, 2019.

16. Koslik HJ, Hamilton G, Golomb BA. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Gulf War illness revealed by 31phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92887.

17. Brewer KL, Mainhart A, Meggs WJ. Double-blinded placebo-controlled cross-over pilot trial of naltrexone to treat Gulf War illness. Fatigue: Biomed Health Behav. 2018;6(3):132-140.

18. Golomb BA, Allison M, Koperski S, Koslik HJ, Devaraj S, Ritchie JB. Coenzyme Q10 benefits symptoms in Gulf War veterans: results of a randomized double-blind study. Neural Comput. 2014;26(11):2594-2651.

19. Weiduschat N, Mao X, Vu D, et al. N-acetylcysteine alleviates cortical glutathione deficit and improves symptoms in CFS: an in vivo validation study using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In: Proceedings from the IACFS/ME 12th Biennial Conference; October 27-30, 2016; Fort Lauderdale, FL. Abstract. http://iacfsme.org/ME-CFS-Primer-Education/News/IACFSME-2016-Program.aspx. Accessed April 22, 2019.

20. White RF, Steele L, O’Callaghan JP, et al. Recent research on Gulf War illness and other health problems in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: effects of toxicant exposures during deployment. Cortex. 2016;74:449-475.

21. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Caring for Gulf War I Veterans. http://www.ngwrc.net/PDF%20Files/caring-for-gulf-war.pdf. Published July 2011. Accessed April 15, 2019.

22. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Gulf War and Health. Update of Serving in the Gulf War. Vol 10. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016.

23. US Department of Veterans Affairs. War-Related Illness and Injury Study Center. Gulf War illness: a guide for veteran health care providers. https://www.warrelatedillness.va.gov/education/factsheets/gulf-war-illness-for-providers.pdf. Updated October 2018. Accessed April 16, 2019.