User login

The integration of palliative care in cancer care is an emerging trend driven by data on the benefits of palliative care intervention in the care of patients with terminal malignancies. Although studies have shown that patients with end-stage organ disease tend to develop similar symptoms and issues as those of cancer patients, the use of palliative care services among patients with end-stage organ disease seems to be limited.1 The clinical course of terminal malignancy is usually marked by a consistent decline, whereas organ failure is usually marked by periods of exacerbations in relation to decompensation.2 Patients with organ failure often exhibit a gradual and subtle decline over time, making it more challenging to predict the disease course.2

Woo and colleagues studied patients with chronic illnesses and showed that, similar to patients diagnosed with cancer, symptoms of fatigue, pain, and dyspnea were common.3 They also found that caregivers of patients with chronic illness reported suboptimal physical and emotional well-being as well as moderate levels of stress.3 These findings suggest that caregivers for cancer and noncancer patients will benefit from the support inherent in an interdisciplinary approach to palliative care.3 According to the CDC, the second leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2011 was cancer followed by chronic respiratory disease.4

The authors conducted a quality improvement (QI) initiative to explore the benefits of integrating palliative care in the care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and share outcomes of improved palliative care education at John D. Dingell VAMC (JDDVAMC) in Detroit, Michigan, for care of patients with COPD.

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a progressive, incurable lung disease.5 It also has been referred to as chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or chronic asthma.5 The degree of severity of COPD is determined by measuring the degree of air flow obstruction by conducting a spirometry test.5 Common symptoms associated with COPD include dyspnea, cough, wheezing, recurring respiratory infections, and generalized weakness.5

Compared with terminally ill patients with lung cancer, patients with COPD were found to have a poorer quality of life as well as more anxiety and depression.6 In a study to evaluate for breathlessness among patients with severe COPD and advanced cancer, Bausewein and colleagues found that both groups reported moderately distressing physical symptoms.7 Both groups also reported shortness of breath as their most distressing physical symptom and worrying as the most common psychological symptom.7 The study also identified a 50% commonality among the participants on palliative care needs.7

The common palliative care needs that were identified were the need for symptom management for breathlessness, access to information, ability to share feelings, a sense of wasted time, and assistance with practical matters.7 During the study’s 6-month data collection period, 61% of the patients with cancer and 10% of the patients with COPD died.7 Median survival for both groups showed that the patients with COPD had a significantly longer median survival of 589 days compared with 107 days for the patients with cancer.7

A retrospective review of patient records from 2010 to 2013 showed that providers referred only 5% of patients with COPD for palliative care.8 In the United Kingdom, the 5-year survival rate among patients diagnosed with severe COPD is 24% to 30%.9 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is one of the most common causes of hospital admissions, and treatments are aimed toward palliation of symptoms.9 As COPD reaches its end stage, incorporation of end-of-life (EOL) care should be considered. Signs that may indicate EOL care is needed include long-term oxygen therapy, depression, hospitalization for exacerbations at a rate of 2 or more a year, evidence of right-sided heart failure, cortisone treatment for > 6 weeks, and a history of noninvasive ventilation or admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).9

Nguyen and colleagues conducted a study in Montreal, Canada, among patients with moderate-to-severe COPD.10 The participants watched a DVD on EOL topics as well as life support measures and their implications.10 After watching the DVD, the researchers conducted interviews with the participants’ about their beliefs and experiences with regards to advance care planning.10 In conducting advance care planning, the participants identified having a relationship with the medical team and appropriate timing for the discussion as important.10

Crucial topics identified by participants included life expectancy, availability of medications to treat symptoms, different treatment options, stages of disease progression, and quality of EOL care.10 Other findings from the study included the participants’ desire to consider their families in the decision-making process.10 Becoming a burden to their families due to their need for physical and financial assistance and the inability to establish clear health care directives were identified as sources of concern.10 Many of the participants also shared a preference to die rather than to give up quality of life or mental capacity.10 Nguyen and colleagues also found that the severity of illness was not a good predictor of the participants’ readiness to engage in advance care planning.10

In Australia, a study conducted among bereaved and current caregivers for patients with severe COPD showed that > 20% of patients who had died of COPD required hands-on care by their caregivers.11 The caregivers also reported similar concerns as those patients with COPD, which included uncertainty about the future, fear of exacerbations, social isolation, and deteriorating health.11 They also reported competing emotions of loyalty, resentment, guilt, and exhaustion.11 Caregivers identified areas they felt could have improved their ability to provide care, such as availability of adaptive equipment, contingency plans for emergency situations, education on the illness, its symptoms and prognosis, and advance care planning information.11 The caregivers believed that receiving this information might have lessened their stress and plan for the future.11 Although most of the aspects of care that they identified as important are components of palliative care, most of the caregivers were unfamiliar with the term palliative care.11

QI Initiative

To improve palliative care education and use in the ICUs of the VA hospitals, the VHA conducted training, which was made available to intensive care providers on improving EOL care and communication. An attending physician in the ICU who also is a pulmonologist took part in this training in July 2013. To evaluate the outcome of this educational effort, the authors’ reviewed the palliative care referrals from 2012 to 2014.

Results

There were a total of 29 patients with COPD who were referred for palliative care services. Sixteen (55%) were referred by pulmonology. Medical oncology and primary care each referred 4 patients (14%). Acute care referred 5 patients (17%). Emergency department (ED) visits were compared 1 year prior with postpalliative care involvement in the patients’ care (Figure 1). The average ED visit for these patients prepalliative care was 3.2 days, and this dropped to 1.7 days postpalliative care involvement. Of the 29 patients, there were 7 who were never seen in the ED for symptoms of COPD prior to palliative care involvement in their care, and 17 who did not have ED visits after palliative care’s involvement in their care. Of the 29 patients, 3 had frequent visits to the ED (more than 10 days total) prepalliative care, and only 1 had frequent visits to the ED following involvement in the palliative care clinic.

According to the JDDVAMC Managerial Cost Accounting Office (MCAO), the average cost to care for a patient who is presenting to the ED with symptoms related to COPD is $527. The cost of caring for the 22 patients who were seen at least once in the ED for symptoms related to their COPD would be $11,594. With palliative care involvement, only 12 of the 29 patients were seen in the ED for symptoms related to COPD for a total of $6,324, a savings of $5,270 for single ED visits for this set of patients.

Prior to palliative care involvement for the 29 patients, there were 27 admissions, which dropped to 15 admissions after palliative care involvement. According to the MCAO, the average cost to care for a patient who is admitted to the hospital due to an exacerbation of COPD is $20,944. With 27 admissions prior to palliative care involvement, the results total $565,488 compared with $314,160 for 15 admissions with palliative care involvement, showing a cost savings of $251,328.

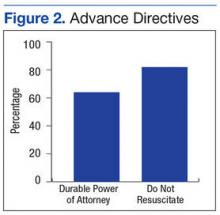

Fourteen of the 29 patients had advance directive discussions, 9 of which were completed by assigning a durable power of attorney and/or completing a living will. There were 22 (76%) of the 29 patients who had code status discussions, and 18 (62%) elected not to be resuscitated (Figure 2). According to MCAO, the average cost to care for a patient in the ICU who required ventilator support for at least 96 hours is $102,175. For the 18 patients who decided not to pursue cardiopulmonary resuscitation, this results in a potential cost savings of $1,839,150.

Conclusion

The outcome of this QI initiative is congruent with the findings published in the literature on the benefits of palliative care involvement in the care of patients with COPD. Palliative care involvement improved goals of care discussions and resulted in decreased ED visits. Palliative care educational outreach also seems to improve palliative care referrals.

In 2007, the American Thoracic Society issued a policy statement recommending that palliative care should be available at any stage during the course of a progressive or chronic respiratory disease or critical illness when the patient becomes symptomatic.12 Compared with patients with lung cancer, patients with COPD have to cope with symptom burden for a longer period. Breathlessness seems to be the most debilitating physical symptom for COPD and should trigger a palliative care referral.7 Comprehensive respiratory care similar to that for cancer care should be considered for severe COPD and should involve both the palliative care team and the pulmonary care teams for optimal results.

The results of this QI initiative also seem to support the potential benefits of palliative care involvement in the care of patients with other chronic illnesses that are expected to progress over time, leading to a shortened life expectancy.

1. Saini T, Murtagh FE, Dupont PJ, McKinnon PM, Hatfield P, Saunders Y. Comparative pilot study of symptoms and quality of life in cancer patients and patients with end stage renal disease. Palliat Med. 2006;20(6):631-636.

2. Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, et al. Evidence for improving palliative care at end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):147-159.

3. Woo J, Lo R, Cheng JO, Wong F, Mak B. Quality of end-of-life care for non-cancer patients in a non-acute hospital. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(13-14):1834-1841.

4. Hoyert DL, Xu JQ. Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol 61. No 6. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_06.pdf. Published October 10, 2012. Accessed July 1, 2016.

5. Barnett M. End of life issues in the management of COPD. J Comm Nurs. 2012; 26(3):4-8.

6. Fitzsimons D, Mullan D, Wilson JS, et al. The challenge of patients’ unmet palliative care needs in the final stages of chronic illness. Palliat Med. 2007;21(4):313-322.

7. Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, Kühnbach R, Haberland B, Higginson IJ. Understanding breathlessness: cross-sectional comparison of symptom burden and palliative care needs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(9):1109-1118.

8. Schroedl C, Yount S, Szmullowicz E, Rosenberg SR, Kalhan R. Outpatient palliative care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a case series. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1256-1261.

9. Iley K. Improving palliative care for patients with COPD. Nurs Stand. 2012;26(37):40-46.

10. Nguyen M, Chamber-Evans J, Joubert A, Drouin I, Ouellet I. Exploring the advance care planning needs of moderately to severely ill people with COPD. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2013;19(8):389-395.

11. Philip J, Gold M, Brand C, Miller B, Douglass J, Sundararajan V. Facilitating change and adaptation: the experiences of current and bereaved carers of patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(4):421-427.

12. Lanken PN, Terry PB, DeLisser HM, et al; American Thoracic Society End-of-Life Care Task Force. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(8):912-927.

The integration of palliative care in cancer care is an emerging trend driven by data on the benefits of palliative care intervention in the care of patients with terminal malignancies. Although studies have shown that patients with end-stage organ disease tend to develop similar symptoms and issues as those of cancer patients, the use of palliative care services among patients with end-stage organ disease seems to be limited.1 The clinical course of terminal malignancy is usually marked by a consistent decline, whereas organ failure is usually marked by periods of exacerbations in relation to decompensation.2 Patients with organ failure often exhibit a gradual and subtle decline over time, making it more challenging to predict the disease course.2

Woo and colleagues studied patients with chronic illnesses and showed that, similar to patients diagnosed with cancer, symptoms of fatigue, pain, and dyspnea were common.3 They also found that caregivers of patients with chronic illness reported suboptimal physical and emotional well-being as well as moderate levels of stress.3 These findings suggest that caregivers for cancer and noncancer patients will benefit from the support inherent in an interdisciplinary approach to palliative care.3 According to the CDC, the second leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2011 was cancer followed by chronic respiratory disease.4

The authors conducted a quality improvement (QI) initiative to explore the benefits of integrating palliative care in the care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and share outcomes of improved palliative care education at John D. Dingell VAMC (JDDVAMC) in Detroit, Michigan, for care of patients with COPD.

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a progressive, incurable lung disease.5 It also has been referred to as chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or chronic asthma.5 The degree of severity of COPD is determined by measuring the degree of air flow obstruction by conducting a spirometry test.5 Common symptoms associated with COPD include dyspnea, cough, wheezing, recurring respiratory infections, and generalized weakness.5

Compared with terminally ill patients with lung cancer, patients with COPD were found to have a poorer quality of life as well as more anxiety and depression.6 In a study to evaluate for breathlessness among patients with severe COPD and advanced cancer, Bausewein and colleagues found that both groups reported moderately distressing physical symptoms.7 Both groups also reported shortness of breath as their most distressing physical symptom and worrying as the most common psychological symptom.7 The study also identified a 50% commonality among the participants on palliative care needs.7

The common palliative care needs that were identified were the need for symptom management for breathlessness, access to information, ability to share feelings, a sense of wasted time, and assistance with practical matters.7 During the study’s 6-month data collection period, 61% of the patients with cancer and 10% of the patients with COPD died.7 Median survival for both groups showed that the patients with COPD had a significantly longer median survival of 589 days compared with 107 days for the patients with cancer.7

A retrospective review of patient records from 2010 to 2013 showed that providers referred only 5% of patients with COPD for palliative care.8 In the United Kingdom, the 5-year survival rate among patients diagnosed with severe COPD is 24% to 30%.9 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is one of the most common causes of hospital admissions, and treatments are aimed toward palliation of symptoms.9 As COPD reaches its end stage, incorporation of end-of-life (EOL) care should be considered. Signs that may indicate EOL care is needed include long-term oxygen therapy, depression, hospitalization for exacerbations at a rate of 2 or more a year, evidence of right-sided heart failure, cortisone treatment for > 6 weeks, and a history of noninvasive ventilation or admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).9

Nguyen and colleagues conducted a study in Montreal, Canada, among patients with moderate-to-severe COPD.10 The participants watched a DVD on EOL topics as well as life support measures and their implications.10 After watching the DVD, the researchers conducted interviews with the participants’ about their beliefs and experiences with regards to advance care planning.10 In conducting advance care planning, the participants identified having a relationship with the medical team and appropriate timing for the discussion as important.10

Crucial topics identified by participants included life expectancy, availability of medications to treat symptoms, different treatment options, stages of disease progression, and quality of EOL care.10 Other findings from the study included the participants’ desire to consider their families in the decision-making process.10 Becoming a burden to their families due to their need for physical and financial assistance and the inability to establish clear health care directives were identified as sources of concern.10 Many of the participants also shared a preference to die rather than to give up quality of life or mental capacity.10 Nguyen and colleagues also found that the severity of illness was not a good predictor of the participants’ readiness to engage in advance care planning.10

In Australia, a study conducted among bereaved and current caregivers for patients with severe COPD showed that > 20% of patients who had died of COPD required hands-on care by their caregivers.11 The caregivers also reported similar concerns as those patients with COPD, which included uncertainty about the future, fear of exacerbations, social isolation, and deteriorating health.11 They also reported competing emotions of loyalty, resentment, guilt, and exhaustion.11 Caregivers identified areas they felt could have improved their ability to provide care, such as availability of adaptive equipment, contingency plans for emergency situations, education on the illness, its symptoms and prognosis, and advance care planning information.11 The caregivers believed that receiving this information might have lessened their stress and plan for the future.11 Although most of the aspects of care that they identified as important are components of palliative care, most of the caregivers were unfamiliar with the term palliative care.11

QI Initiative

To improve palliative care education and use in the ICUs of the VA hospitals, the VHA conducted training, which was made available to intensive care providers on improving EOL care and communication. An attending physician in the ICU who also is a pulmonologist took part in this training in July 2013. To evaluate the outcome of this educational effort, the authors’ reviewed the palliative care referrals from 2012 to 2014.

Results

There were a total of 29 patients with COPD who were referred for palliative care services. Sixteen (55%) were referred by pulmonology. Medical oncology and primary care each referred 4 patients (14%). Acute care referred 5 patients (17%). Emergency department (ED) visits were compared 1 year prior with postpalliative care involvement in the patients’ care (Figure 1). The average ED visit for these patients prepalliative care was 3.2 days, and this dropped to 1.7 days postpalliative care involvement. Of the 29 patients, there were 7 who were never seen in the ED for symptoms of COPD prior to palliative care involvement in their care, and 17 who did not have ED visits after palliative care’s involvement in their care. Of the 29 patients, 3 had frequent visits to the ED (more than 10 days total) prepalliative care, and only 1 had frequent visits to the ED following involvement in the palliative care clinic.

According to the JDDVAMC Managerial Cost Accounting Office (MCAO), the average cost to care for a patient who is presenting to the ED with symptoms related to COPD is $527. The cost of caring for the 22 patients who were seen at least once in the ED for symptoms related to their COPD would be $11,594. With palliative care involvement, only 12 of the 29 patients were seen in the ED for symptoms related to COPD for a total of $6,324, a savings of $5,270 for single ED visits for this set of patients.

Prior to palliative care involvement for the 29 patients, there were 27 admissions, which dropped to 15 admissions after palliative care involvement. According to the MCAO, the average cost to care for a patient who is admitted to the hospital due to an exacerbation of COPD is $20,944. With 27 admissions prior to palliative care involvement, the results total $565,488 compared with $314,160 for 15 admissions with palliative care involvement, showing a cost savings of $251,328.

Fourteen of the 29 patients had advance directive discussions, 9 of which were completed by assigning a durable power of attorney and/or completing a living will. There were 22 (76%) of the 29 patients who had code status discussions, and 18 (62%) elected not to be resuscitated (Figure 2). According to MCAO, the average cost to care for a patient in the ICU who required ventilator support for at least 96 hours is $102,175. For the 18 patients who decided not to pursue cardiopulmonary resuscitation, this results in a potential cost savings of $1,839,150.

Conclusion

The outcome of this QI initiative is congruent with the findings published in the literature on the benefits of palliative care involvement in the care of patients with COPD. Palliative care involvement improved goals of care discussions and resulted in decreased ED visits. Palliative care educational outreach also seems to improve palliative care referrals.

In 2007, the American Thoracic Society issued a policy statement recommending that palliative care should be available at any stage during the course of a progressive or chronic respiratory disease or critical illness when the patient becomes symptomatic.12 Compared with patients with lung cancer, patients with COPD have to cope with symptom burden for a longer period. Breathlessness seems to be the most debilitating physical symptom for COPD and should trigger a palliative care referral.7 Comprehensive respiratory care similar to that for cancer care should be considered for severe COPD and should involve both the palliative care team and the pulmonary care teams for optimal results.

The results of this QI initiative also seem to support the potential benefits of palliative care involvement in the care of patients with other chronic illnesses that are expected to progress over time, leading to a shortened life expectancy.

The integration of palliative care in cancer care is an emerging trend driven by data on the benefits of palliative care intervention in the care of patients with terminal malignancies. Although studies have shown that patients with end-stage organ disease tend to develop similar symptoms and issues as those of cancer patients, the use of palliative care services among patients with end-stage organ disease seems to be limited.1 The clinical course of terminal malignancy is usually marked by a consistent decline, whereas organ failure is usually marked by periods of exacerbations in relation to decompensation.2 Patients with organ failure often exhibit a gradual and subtle decline over time, making it more challenging to predict the disease course.2

Woo and colleagues studied patients with chronic illnesses and showed that, similar to patients diagnosed with cancer, symptoms of fatigue, pain, and dyspnea were common.3 They also found that caregivers of patients with chronic illness reported suboptimal physical and emotional well-being as well as moderate levels of stress.3 These findings suggest that caregivers for cancer and noncancer patients will benefit from the support inherent in an interdisciplinary approach to palliative care.3 According to the CDC, the second leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2011 was cancer followed by chronic respiratory disease.4

The authors conducted a quality improvement (QI) initiative to explore the benefits of integrating palliative care in the care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and share outcomes of improved palliative care education at John D. Dingell VAMC (JDDVAMC) in Detroit, Michigan, for care of patients with COPD.

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a progressive, incurable lung disease.5 It also has been referred to as chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or chronic asthma.5 The degree of severity of COPD is determined by measuring the degree of air flow obstruction by conducting a spirometry test.5 Common symptoms associated with COPD include dyspnea, cough, wheezing, recurring respiratory infections, and generalized weakness.5

Compared with terminally ill patients with lung cancer, patients with COPD were found to have a poorer quality of life as well as more anxiety and depression.6 In a study to evaluate for breathlessness among patients with severe COPD and advanced cancer, Bausewein and colleagues found that both groups reported moderately distressing physical symptoms.7 Both groups also reported shortness of breath as their most distressing physical symptom and worrying as the most common psychological symptom.7 The study also identified a 50% commonality among the participants on palliative care needs.7

The common palliative care needs that were identified were the need for symptom management for breathlessness, access to information, ability to share feelings, a sense of wasted time, and assistance with practical matters.7 During the study’s 6-month data collection period, 61% of the patients with cancer and 10% of the patients with COPD died.7 Median survival for both groups showed that the patients with COPD had a significantly longer median survival of 589 days compared with 107 days for the patients with cancer.7

A retrospective review of patient records from 2010 to 2013 showed that providers referred only 5% of patients with COPD for palliative care.8 In the United Kingdom, the 5-year survival rate among patients diagnosed with severe COPD is 24% to 30%.9 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is one of the most common causes of hospital admissions, and treatments are aimed toward palliation of symptoms.9 As COPD reaches its end stage, incorporation of end-of-life (EOL) care should be considered. Signs that may indicate EOL care is needed include long-term oxygen therapy, depression, hospitalization for exacerbations at a rate of 2 or more a year, evidence of right-sided heart failure, cortisone treatment for > 6 weeks, and a history of noninvasive ventilation or admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).9

Nguyen and colleagues conducted a study in Montreal, Canada, among patients with moderate-to-severe COPD.10 The participants watched a DVD on EOL topics as well as life support measures and their implications.10 After watching the DVD, the researchers conducted interviews with the participants’ about their beliefs and experiences with regards to advance care planning.10 In conducting advance care planning, the participants identified having a relationship with the medical team and appropriate timing for the discussion as important.10

Crucial topics identified by participants included life expectancy, availability of medications to treat symptoms, different treatment options, stages of disease progression, and quality of EOL care.10 Other findings from the study included the participants’ desire to consider their families in the decision-making process.10 Becoming a burden to their families due to their need for physical and financial assistance and the inability to establish clear health care directives were identified as sources of concern.10 Many of the participants also shared a preference to die rather than to give up quality of life or mental capacity.10 Nguyen and colleagues also found that the severity of illness was not a good predictor of the participants’ readiness to engage in advance care planning.10

In Australia, a study conducted among bereaved and current caregivers for patients with severe COPD showed that > 20% of patients who had died of COPD required hands-on care by their caregivers.11 The caregivers also reported similar concerns as those patients with COPD, which included uncertainty about the future, fear of exacerbations, social isolation, and deteriorating health.11 They also reported competing emotions of loyalty, resentment, guilt, and exhaustion.11 Caregivers identified areas they felt could have improved their ability to provide care, such as availability of adaptive equipment, contingency plans for emergency situations, education on the illness, its symptoms and prognosis, and advance care planning information.11 The caregivers believed that receiving this information might have lessened their stress and plan for the future.11 Although most of the aspects of care that they identified as important are components of palliative care, most of the caregivers were unfamiliar with the term palliative care.11

QI Initiative

To improve palliative care education and use in the ICUs of the VA hospitals, the VHA conducted training, which was made available to intensive care providers on improving EOL care and communication. An attending physician in the ICU who also is a pulmonologist took part in this training in July 2013. To evaluate the outcome of this educational effort, the authors’ reviewed the palliative care referrals from 2012 to 2014.

Results

There were a total of 29 patients with COPD who were referred for palliative care services. Sixteen (55%) were referred by pulmonology. Medical oncology and primary care each referred 4 patients (14%). Acute care referred 5 patients (17%). Emergency department (ED) visits were compared 1 year prior with postpalliative care involvement in the patients’ care (Figure 1). The average ED visit for these patients prepalliative care was 3.2 days, and this dropped to 1.7 days postpalliative care involvement. Of the 29 patients, there were 7 who were never seen in the ED for symptoms of COPD prior to palliative care involvement in their care, and 17 who did not have ED visits after palliative care’s involvement in their care. Of the 29 patients, 3 had frequent visits to the ED (more than 10 days total) prepalliative care, and only 1 had frequent visits to the ED following involvement in the palliative care clinic.

According to the JDDVAMC Managerial Cost Accounting Office (MCAO), the average cost to care for a patient who is presenting to the ED with symptoms related to COPD is $527. The cost of caring for the 22 patients who were seen at least once in the ED for symptoms related to their COPD would be $11,594. With palliative care involvement, only 12 of the 29 patients were seen in the ED for symptoms related to COPD for a total of $6,324, a savings of $5,270 for single ED visits for this set of patients.

Prior to palliative care involvement for the 29 patients, there were 27 admissions, which dropped to 15 admissions after palliative care involvement. According to the MCAO, the average cost to care for a patient who is admitted to the hospital due to an exacerbation of COPD is $20,944. With 27 admissions prior to palliative care involvement, the results total $565,488 compared with $314,160 for 15 admissions with palliative care involvement, showing a cost savings of $251,328.

Fourteen of the 29 patients had advance directive discussions, 9 of which were completed by assigning a durable power of attorney and/or completing a living will. There were 22 (76%) of the 29 patients who had code status discussions, and 18 (62%) elected not to be resuscitated (Figure 2). According to MCAO, the average cost to care for a patient in the ICU who required ventilator support for at least 96 hours is $102,175. For the 18 patients who decided not to pursue cardiopulmonary resuscitation, this results in a potential cost savings of $1,839,150.

Conclusion

The outcome of this QI initiative is congruent with the findings published in the literature on the benefits of palliative care involvement in the care of patients with COPD. Palliative care involvement improved goals of care discussions and resulted in decreased ED visits. Palliative care educational outreach also seems to improve palliative care referrals.

In 2007, the American Thoracic Society issued a policy statement recommending that palliative care should be available at any stage during the course of a progressive or chronic respiratory disease or critical illness when the patient becomes symptomatic.12 Compared with patients with lung cancer, patients with COPD have to cope with symptom burden for a longer period. Breathlessness seems to be the most debilitating physical symptom for COPD and should trigger a palliative care referral.7 Comprehensive respiratory care similar to that for cancer care should be considered for severe COPD and should involve both the palliative care team and the pulmonary care teams for optimal results.

The results of this QI initiative also seem to support the potential benefits of palliative care involvement in the care of patients with other chronic illnesses that are expected to progress over time, leading to a shortened life expectancy.

1. Saini T, Murtagh FE, Dupont PJ, McKinnon PM, Hatfield P, Saunders Y. Comparative pilot study of symptoms and quality of life in cancer patients and patients with end stage renal disease. Palliat Med. 2006;20(6):631-636.

2. Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, et al. Evidence for improving palliative care at end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):147-159.

3. Woo J, Lo R, Cheng JO, Wong F, Mak B. Quality of end-of-life care for non-cancer patients in a non-acute hospital. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(13-14):1834-1841.

4. Hoyert DL, Xu JQ. Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol 61. No 6. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_06.pdf. Published October 10, 2012. Accessed July 1, 2016.

5. Barnett M. End of life issues in the management of COPD. J Comm Nurs. 2012; 26(3):4-8.

6. Fitzsimons D, Mullan D, Wilson JS, et al. The challenge of patients’ unmet palliative care needs in the final stages of chronic illness. Palliat Med. 2007;21(4):313-322.

7. Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, Kühnbach R, Haberland B, Higginson IJ. Understanding breathlessness: cross-sectional comparison of symptom burden and palliative care needs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(9):1109-1118.

8. Schroedl C, Yount S, Szmullowicz E, Rosenberg SR, Kalhan R. Outpatient palliative care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a case series. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1256-1261.

9. Iley K. Improving palliative care for patients with COPD. Nurs Stand. 2012;26(37):40-46.

10. Nguyen M, Chamber-Evans J, Joubert A, Drouin I, Ouellet I. Exploring the advance care planning needs of moderately to severely ill people with COPD. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2013;19(8):389-395.

11. Philip J, Gold M, Brand C, Miller B, Douglass J, Sundararajan V. Facilitating change and adaptation: the experiences of current and bereaved carers of patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(4):421-427.

12. Lanken PN, Terry PB, DeLisser HM, et al; American Thoracic Society End-of-Life Care Task Force. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(8):912-927.

1. Saini T, Murtagh FE, Dupont PJ, McKinnon PM, Hatfield P, Saunders Y. Comparative pilot study of symptoms and quality of life in cancer patients and patients with end stage renal disease. Palliat Med. 2006;20(6):631-636.

2. Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, et al. Evidence for improving palliative care at end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):147-159.

3. Woo J, Lo R, Cheng JO, Wong F, Mak B. Quality of end-of-life care for non-cancer patients in a non-acute hospital. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(13-14):1834-1841.

4. Hoyert DL, Xu JQ. Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol 61. No 6. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_06.pdf. Published October 10, 2012. Accessed July 1, 2016.

5. Barnett M. End of life issues in the management of COPD. J Comm Nurs. 2012; 26(3):4-8.

6. Fitzsimons D, Mullan D, Wilson JS, et al. The challenge of patients’ unmet palliative care needs in the final stages of chronic illness. Palliat Med. 2007;21(4):313-322.

7. Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, Kühnbach R, Haberland B, Higginson IJ. Understanding breathlessness: cross-sectional comparison of symptom burden and palliative care needs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(9):1109-1118.

8. Schroedl C, Yount S, Szmullowicz E, Rosenberg SR, Kalhan R. Outpatient palliative care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a case series. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1256-1261.

9. Iley K. Improving palliative care for patients with COPD. Nurs Stand. 2012;26(37):40-46.

10. Nguyen M, Chamber-Evans J, Joubert A, Drouin I, Ouellet I. Exploring the advance care planning needs of moderately to severely ill people with COPD. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2013;19(8):389-395.

11. Philip J, Gold M, Brand C, Miller B, Douglass J, Sundararajan V. Facilitating change and adaptation: the experiences of current and bereaved carers of patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(4):421-427.

12. Lanken PN, Terry PB, DeLisser HM, et al; American Thoracic Society End-of-Life Care Task Force. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(8):912-927.