User login

CE/CME No: CR-1401

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the criteria for diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

• List three dietary interventions that may reduce symptoms of IBS.

• Discuss the role of probiotics in the treatment of IBS.

• List three classes of prescription medication that may reduce symptoms of IBS.

FACULTY

Suzanne Martin is an Assistant Professor at the University of Utah College of Nursing and works as a family nurse practitioner at the University of Utah Student Health Center in Salt Lake City.

The author has no financial disclosures to report.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a functional gastrointestinal disorder usually manifesting with abdominal pain and altered bowel movements, is often seen in primary care. With the recent advances in evidence-based knowledge, you can now more readily make a diagnosis and offer your patients with IBS a variety of treatment options tailored to their needs.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common gastrointestinal complaint seen in both primary and gastroenterology clinics.1 Direct and indirect costs associated with IBS total more than $20 billion. Studies have shown that patients with IBS consume 50% more health care resources than matched controls. The prevalence of IBS ranges from less than 1% to more than 20%. Using strict criteria, the pooled prevalence rate of IBS in North America is 7%.1

IBS occurs more commonly in women and lower socioeconomic populations and is more likely to be diagnosed before age 50.1 Individuals with IBS report diminished health-related quality of life (HRQOL) scores compared to those without the disease. In some cases, decreased HRQOL can be severe, resulting in increased risk for suicidal behavior.1

The pathogenesis of IBS is not entirely understood. Contributing factors may include impaired gastrointestinal motility, visceral hypersensitivity, increased mucosal permeability, carbohydrate malabsorption, bacterial overgrowth, altered brain-gut axis, altered intestinal microbiota, psychosocial disturbances, and genetic predisposition.1,2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Hallmark symptoms of IBS are abdominal pain, dyspepsia, and altered bowel movements. The abdominal pain of IBS can be located anywhere and can range in severity from “annoying” to “debilitating” (see “Living with IBS,”). Eating and stress may aggravate pain, and a bowel movement may attenuate it. The pain is usually intermittent throughout the day; nocturnal pain is unusual and suggests an alternate cause.3

Dyspepsia (epigastric discomfort, postprandial fullness, early satiety) can occur in up to 87% of patients with IBS.4 Other features associated with IBS include gastroesophageal reflux disease nausea; noncardiac chest pain; bloating, belching and/or flatulence; sexual dysfunction; dyspareunia; urinary frequency and urgency; and fibromyalgia.

The patient with IBS will also experience a change in the type of bowel movement. Therefore, IBS is often categorized according to the predominant change: diarrhea (known as IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), and alternating diarrhea and constipation (IBS-M). IBS-D is defined by diarrhea that is typically small to moderate in volume, occurs after meals or in the morning, and is associated with mucus 50% of the time.4 IBS-C is characterized by constipation with stools that are typically hard and pelletlike, accompanied by straining, with fewer than three bowel movements per week.

Patients with IBS may describe a sense of incomplete evacuation.4 Alarm signs and symptoms, which include progressive symptoms; nocturnal symptoms; weight loss, malnutrition, and anorexia; stools that are large in volume, bloody, or greasy; anemia, electrolyte disturbance, and elevated inflammatory markers; or a family history of inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, or celiac disease, should prompt evaluation for alternate etiologies.1,4

Continued on next page >>

DIAGNOSIS

Work-up

Although the patient with IBS may present with mild nonspecific abdominal pain, the physical exam is typically normal.4,5 Patients who meet the Rome III diagnostic criteria—in the absence of alarm signs and symptoms or worrisome family history—are candidates for a clinical diagnosis of IBS.6 These criteria, originally developed for research purposes but useful in a clinical setting, include

• Symptom onset at least six months prior to diagnosis

• Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort for more than three days per month during the past three months, and at least two of the following features:

• Improvement of symptoms with defecation

• A change in stool frequency

• A change in stool form.1,4,6

Due to inherent difficulty in establishing the accuracy of such criteria, a simple and practical alternative clinical definition is suggested by the American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on IBS: IBS is characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort that occurs in association with altered bowel habits over a period of at least three months.1 Patients meeting clinical criteria without alarm symptoms or worrisome family history require no additional testing.1

Moderate evidence supports routine testing for celiac disease in individuals presenting with symptoms consistent with IBS-D or IBS-M.1 Lactose hydrogen breath testing is recommended for individuals reporting symptoms that suggest a correlation between the ingestion of lactose and onset of IBS symptoms.1 When a patient presents with alarm features, significant family history, refractory symptoms, or new concerning symptoms, further testing is indicated, with test selection based on specific symptoms and risk factors.1,4,5

Differential Diagnosis

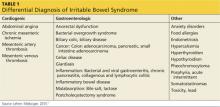

In addition to IBS, there are numerous other conditions spanning several clinical categories that should be considered in patients who present with symptoms of IBS (see Table 1). In the cardiogenic group, abdominal angina, mesenteric artery thrombosis, and mesenteric artery venous thrombosis share common symptoms (eg, sudden stomach pain) with IBS, which may confuse the diagnostic picture. Gastrointestinal disorders such as bacterial overgrowth, celiac disease, gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and anorectal dysfunction (incontinence) should be considered in patients who present with IBS symptoms. Pancreatic, ovarian, and colorectal cancer should also be investigated as a possible diagnosis.4,5,7

Continued on next page >>

TREATMENT

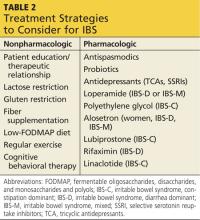

Evidence supports a number of therapeutic options, both lifestyle and pharmacologic (see Table 2). Lifestyle options include comprehensive patient education, dietary manipulation, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and exercise. Pharmacologic options include antispasmodic agents, antidepressants, antidiarrheal agents, osmotic laxatives, alosetron, lubiprostone, rifaximin, and linaclotide.

Lifestyle changes

A therapeutic relationship that includes a nonjudgmental attitude, realistic expectations, and patient-directed care is the cornerstone of successful nonpharmacologic IBS management.4 In addition, patient education should emphasize management instead of cure, and the patient should be informed that IBS may wax and wane over a lifetime but will not shorten his/her lifespan.4

A six-week, single-blind, randomized trial (N = 262) attempted to assess the impact of patient–provider interaction on IBS symptoms and HRQOL. Participants were assigned to one of three groups: waiting list, limited intervention, and augmented intervention, with the last group receiving the greatest amount of education and patient–provider interaction. After three and six weeks, participants in the augmented group reported significant improvements in global IBS symptoms and HRQOL scores.8 Although these findings are limited by a short follow-up period, they underscore the importance of a strong therapeutic relationship in a successful outcome.

Diet. Since food sensitivities—to lactose; gluten; fiber; fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, and monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP); and carbohydrates—are thought to be integral to the etiology of IBS, dietary manipulation plays a major role in managing symptoms.4

Due to overlapping symptoms, a lactose-restricted diet may be appropriate in a subset of IBS-D and IBS-M patients. A prospective clinical trial enrolled 70 adult participants with IBS, 24% of whom were lactose intolerant. All participants were given a lactose-restricted diet for six weeks, and a significant improvement of IBS symptoms in the lactose-intolerant subgroup was observed. This subgroup was advised to continue a lactose-restricted diet and was then followed for five years. Of the 14 participants who remained in the study for the five years, none reported IBS complaints.9 While limited by its small sample size, this study supports the ACG recommendation to consider lactose hydrogen breath testing to screen for lactose-intolerance in a select group of patients with IBS symptoms.

Gluten. It has been observed that gluten withdrawal may improve IBS symptoms. A recent four-week randomized controlled trial (RCT; N = 45) evaluated the effect of gluten restriction on subjective markers including stool frequency, form, and ease of passage, and on objective markers related to intestinal function in adults with known IBS-D who did not have gluten sensitivity or celiac disease.10 Participants on the gluten-restricted diet reported a significant reduction in stool frequency, especially among those with HLA DQ2 and DQ8 genotypes. There was no effect on stool form or ease of passage.10

An RCT conducted by Biesiekierski and colleagues enrolled 30 patients with IBS who reported symptom control on a gluten-free diet.11 Study participants were randomly assigned to either a continued gluten-free diet or to a gluten-containing diet. Over the six-week

follow-up period, significantly more participants on a gluten-containing diet reported inadequate control of IBS symptoms.11 The small sample size and short follow-up period led the researchers to conclude that additional studies are needed to confirm whether gluten restriction attenuates IBS symptoms.

Fiber. Data are inconclusive regarding efficacy of fiber in reducing IBS symptoms. A subgroup of patients with IBS report increased abdominal pain and bloating when increasing their fiber intake.1 This was supported by a systematic review that found no clinical improvement in IBS symptoms with bulking agents.12 That said, patients with IBS-C may benefit from a trial of dietary fiber, which should be introduced at a low dose (eg, 1/2 to 1 Tb of wheat bran or psyllium daily) and titrated up as needed and tolerated.1

FODMAP. A number of clinical trials have suggested that there is a benefit to consuming a diet low in FODMAP foods (see chart). Shepherd and colleagues conducted an RCT (N = 25) that compared the effects of high- and low-FODMAP diets on IBS symptoms over a two-week period. Of participants in the high-FODMAP group, 79% reported inadequate IBS symptom control, while only 14% in the low-FODMAP group reported inadequate IBS symptom control.13

In a second trial (N = 30) that had similar objectives, symptoms worsened significantly on a

high-FODMAP diet compared to a low one among the IBS participants. Healthy participants experienced more flatulence on the high-FODMAP diet compared to those on a low one.14

Carbohydrates. In a small clinical trial (N = 17), IBS-D participants consumed a standard diet for two weeks followed by a very low carbohydrate diet (< 20 g/d) for four weeks. They were assessed weekly for adequate relief of IBS symptoms. For purposes of the study, a patient was considered a responder if he/she experienced adequate relief of IBS symptoms during at least two of the four treatment weeks. In addition to symptom relief, secondary measures included abdominal pain, stool frequency, stool consistency, and quality of life.15

Of the 13 participants who completed the study, all were considered responders; 10 of 13 (77%) reported adequate relief of IBS symptoms for four out of four treatment weeks. There were significant improvements in abdominal pain, stool frequency, stool consistency, and quality of life during treatment weeks.15 Additional trials with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

Exercise. Regular exercise not only offers general health benefits but may also simultaneously reduce IBS symptoms. An RCT (N =102) assigned patients with IBS either to their normal daily activity or to 20 to 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise three to five days a week. After 12 weeks, the exercise group showed decreased IBS symptom severity. They were also significantly less likely to report worsening IBS symptoms.16

Cognitive behavioral therapy. CBT may be helpful in reducing IBS symptoms. In an RCT (N = 75) that assigned patients with IBS to conventional CBT, self-administered CBT, or a control group, IBS symptoms improved significantly in those assigned to both CBT groups.17 A systematic review and meta-analysis reported a relative risk (RR) of persistent IBS symptoms with CBT of 0.67 and a number needed to treat (NNT) of 4.18

Continued on next page >>

Pharmacologic Treatment

Prescription and OTC medications serve an adjunctive role in the management of IBS.1 Efficacy trials in the IBS population are limited by disease heterogeneity, lack of disease markers, and high placebo response rates.19

Antispasmodics. Prescription antispasmodics, such as dicyclomine, have been shown to offer short-term relief of IBS-related abdominal pain; however, long-term outcomes are unknown. Possible adverse effects such as dizziness, dry mouth, blurred vision, and sluggishness may limit their use. Peppermint oil is considered an alternative to prescription antispasmodics and has been found to improve global IBS symptoms (RR, 2.25).12

Probiotics. A number of trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses have addressed the effect of probiotics on IBS symptoms. Meta-analyses found an RR of 0.72 to 0.77 for persistent IBS symptoms in patients using probiotics.20 Because probiotics can be beneficial, with relatively low cost and minimal associated risks, it is reasonable to consider a trial of probiotics, especially the specific strains offering the most promising results, such as Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 and Escherichia coli DSM 17252. Like most IBS treatments, it is unlikely that probiotics will benefit all IBS patients.20

Antidepressants. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were found to be effective in reducing the risk for persistent IBS symptoms in adults (RR, 0.66; NNT, 4).12,18 TCAs can slow gastrointestinal transit time, which may be beneficial to patients with IBS-D but a drawback to those with IBS-C. SSRIs, such as fluoxetine, are especially appropriate for patients with concurrent anxiety or depression. Note that three to four weeks of treatment with antidepressants are required to see benefits.1

Others. Loperamide has been reported to significantly improve stool frequency and consistency in patients with IBS-D and IBS-M but not global IBS symptoms.1,2 Polyethylene glycol has been shown to be effective in treating adults with isolated constipation, but it was not superior to placebo in adults with IBS-C.21

A systematic review found that the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist alosetron offered clinical benefit to patients with IBS-D and IBS-M.22 However, due to reports of ischemic colitis and severe constipation, the FDA removed the drug from the US market in 2000. Ultimately, postmarketing data and patient demand brought the drug back onto the market in 2002, but it can be prescribed only with careful regulation and only for women with severe, refractory IBS-D.23,24

A locally acting chloride channel activator, lubiprostone, offers clinical benefit to patients with IBS-C and chronic constipation.25 Because of its unknown long-term effects, high expense, and lack of comparison data to other IBS-C treatments, this drug should only be given to women with severe refractory IBS-C.26

Two large multicenter RCTs found that a two-week course of rifaximin, a nonabsorbable antibiotic, reduced global IBS symptoms, especially bloating, in patients with IBS without constipation. The benefits continued through 10 weeks of follow-up.27 Prescribing rifaximin for the treatment of IBS is an off-label use and should be limited to patients with IBS-D who have not responded to currently available symptom-directed therapies. In addition, the lack of evidence for long-term benefits as well as the potential for development of antibiotic resistance should be borne in mind when using this drug.28

Linaclotide is approved for IBS-C, based on two large RCTs with 12- and 26-week follow-up periods. Treatment group participants reported substantial improvement in IBS-C symptoms. Approximately 5% of participants discontinued treatment due to diarrhea.29,30

Continued on next page >>

CONCLUSION

IBS is a commonly occurring disorder of heterogeneous nature and pathogenesis. Therefore, basing a diagnosis on the presenting symptoms is not ideal; using clinical criteria to make a determination is more accurate. Once the diagnosis is made, IBS can be categorized into subtypes according to bowel function: diarrhea, constipation, or mixed. Knowing the subtype may guide the clinician in recommending a treatment, eg, patients with IBS-D may benefit from loperamide and those with IBS-C find relief with lubiprostone. The range of treatment strategies includes making lifestyle changes (eg, diet and exercise); incorporating CBT; and prescribing neuromotility agents and probiotics.

1. Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, et al; American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(suppl 1):S1-S35.

2. Wald A. Irritable bowel syndrome—diarrhoea. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:573-580.

3. Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108-2131.

4. World Gastroenterology Organization. Irritable bowel syndrome: a global perspective (2009). www.worldgastroenterology.org/assets/downloads/en/pdf/guidelines/20_irritable_bowel_syndrome.pdf. Accessed December 16, 2013.

5. Olden KW. Diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1701-1714.

6. Engsbro AL, Begtrup LM, Kjeldsen J, et al. Patients suspected of irritable bowel syndrome—cross-sectional study exploring the sensitivity of Rome III criteria in primary care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:972-980.

7. Lehrer JK. Irritable bowel syndrome differential diagnoses. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/180389-overview. Accessed December 16, 2013.

8. Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 2008;336:999-1003.

9. Böhmer CJ, Tuynman HA. The effect of a lactose-restricted diet in patients with a positive lactose tolerance test, earlier diagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome: a 5-year follow-up study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001; 13:941-944.

10. Vazquez-Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:903-911.

11. Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:508-514.

12. Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10(8):CD003460.

13. Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir G, Gibson PR. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:765-771.

14. Ong DK, Mitchell SB, Barrett JS, et al. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1366-1373.

15. Austin GL, Dalton CB, Hu Y, et al. A very low-carbohydrate diet improves symptoms and quality of life in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:706-708.

16. Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, et al. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:915-922.

17. Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS, et al. Self-administered cognitive behavior therapy for moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome: clinical efficacy, tolerability, feasibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:899-906.

18. Ford AC, Talley NJ, Schoenfeld PS, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2009;58:367-378.

19. Jailwala J, Imperiale TF, Kroenke K. Pharmacologic treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:136-147.

20. Parkes GC, Sanderson JD, Whelan K. Treating irritable bowel syndrome with probiotics: the evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69:187-194.

21. Awad RA, Camacho S. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of polyethylene glycol effects on fasting and postprandial rectal sensitivity and symptoms in hypersensitive constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:1131-1138.

22. Andresen V, Montori VM, Keller J, et al. Effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) type 3 antagonists on symptom relief and constipation in nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6: 545-555.

23. FDA. Lotronex (alosetron hydrochloride) tablets. www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/safetyinformation/safetyalertsforhumanmedicalproducts/ucm172946.htm. Accessed December 16, 2013.

24. FDA. Lotronex (alosetron hydrochloride) information. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm110450.htm. Accessed December 16, 2013.

25. Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, et al. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome—results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:329-341.

26. Lunsford TN, Harris LA. Lubiprostone: evaluation of the newest medication for the treatment of adult women with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Womens Health. 2010;2:361-374.

27. Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al; TARGET Study Group. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation.

N Engl J Med. 2011;364:22-32.

28. Tack J. Antibiotic therapy for the irritable bowel syndrome.N Engl J Med. 2011;364:81-82.

29. Rao S, Lembo AJ, Shiff SJ, et al. A 12-week, randomized, controlled trial with a 4-week randomized withdrawal period to evaluate the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1714-1724.

30. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Lavins BJ, et al. Linaclotide for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1702-1712.

31. Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: the FODMAP approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:252-258.

32. Magge S, Lembo A. Low-FODMAP diet for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;8:739-745.

CE/CME No: CR-1401

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the criteria for diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

• List three dietary interventions that may reduce symptoms of IBS.

• Discuss the role of probiotics in the treatment of IBS.

• List three classes of prescription medication that may reduce symptoms of IBS.

FACULTY

Suzanne Martin is an Assistant Professor at the University of Utah College of Nursing and works as a family nurse practitioner at the University of Utah Student Health Center in Salt Lake City.

The author has no financial disclosures to report.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a functional gastrointestinal disorder usually manifesting with abdominal pain and altered bowel movements, is often seen in primary care. With the recent advances in evidence-based knowledge, you can now more readily make a diagnosis and offer your patients with IBS a variety of treatment options tailored to their needs.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common gastrointestinal complaint seen in both primary and gastroenterology clinics.1 Direct and indirect costs associated with IBS total more than $20 billion. Studies have shown that patients with IBS consume 50% more health care resources than matched controls. The prevalence of IBS ranges from less than 1% to more than 20%. Using strict criteria, the pooled prevalence rate of IBS in North America is 7%.1

IBS occurs more commonly in women and lower socioeconomic populations and is more likely to be diagnosed before age 50.1 Individuals with IBS report diminished health-related quality of life (HRQOL) scores compared to those without the disease. In some cases, decreased HRQOL can be severe, resulting in increased risk for suicidal behavior.1

The pathogenesis of IBS is not entirely understood. Contributing factors may include impaired gastrointestinal motility, visceral hypersensitivity, increased mucosal permeability, carbohydrate malabsorption, bacterial overgrowth, altered brain-gut axis, altered intestinal microbiota, psychosocial disturbances, and genetic predisposition.1,2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Hallmark symptoms of IBS are abdominal pain, dyspepsia, and altered bowel movements. The abdominal pain of IBS can be located anywhere and can range in severity from “annoying” to “debilitating” (see “Living with IBS,”). Eating and stress may aggravate pain, and a bowel movement may attenuate it. The pain is usually intermittent throughout the day; nocturnal pain is unusual and suggests an alternate cause.3

Dyspepsia (epigastric discomfort, postprandial fullness, early satiety) can occur in up to 87% of patients with IBS.4 Other features associated with IBS include gastroesophageal reflux disease nausea; noncardiac chest pain; bloating, belching and/or flatulence; sexual dysfunction; dyspareunia; urinary frequency and urgency; and fibromyalgia.

The patient with IBS will also experience a change in the type of bowel movement. Therefore, IBS is often categorized according to the predominant change: diarrhea (known as IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), and alternating diarrhea and constipation (IBS-M). IBS-D is defined by diarrhea that is typically small to moderate in volume, occurs after meals or in the morning, and is associated with mucus 50% of the time.4 IBS-C is characterized by constipation with stools that are typically hard and pelletlike, accompanied by straining, with fewer than three bowel movements per week.

Patients with IBS may describe a sense of incomplete evacuation.4 Alarm signs and symptoms, which include progressive symptoms; nocturnal symptoms; weight loss, malnutrition, and anorexia; stools that are large in volume, bloody, or greasy; anemia, electrolyte disturbance, and elevated inflammatory markers; or a family history of inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, or celiac disease, should prompt evaluation for alternate etiologies.1,4

Continued on next page >>

DIAGNOSIS

Work-up

Although the patient with IBS may present with mild nonspecific abdominal pain, the physical exam is typically normal.4,5 Patients who meet the Rome III diagnostic criteria—in the absence of alarm signs and symptoms or worrisome family history—are candidates for a clinical diagnosis of IBS.6 These criteria, originally developed for research purposes but useful in a clinical setting, include

• Symptom onset at least six months prior to diagnosis

• Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort for more than three days per month during the past three months, and at least two of the following features:

• Improvement of symptoms with defecation

• A change in stool frequency

• A change in stool form.1,4,6

Due to inherent difficulty in establishing the accuracy of such criteria, a simple and practical alternative clinical definition is suggested by the American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on IBS: IBS is characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort that occurs in association with altered bowel habits over a period of at least three months.1 Patients meeting clinical criteria without alarm symptoms or worrisome family history require no additional testing.1

Moderate evidence supports routine testing for celiac disease in individuals presenting with symptoms consistent with IBS-D or IBS-M.1 Lactose hydrogen breath testing is recommended for individuals reporting symptoms that suggest a correlation between the ingestion of lactose and onset of IBS symptoms.1 When a patient presents with alarm features, significant family history, refractory symptoms, or new concerning symptoms, further testing is indicated, with test selection based on specific symptoms and risk factors.1,4,5

Differential Diagnosis

In addition to IBS, there are numerous other conditions spanning several clinical categories that should be considered in patients who present with symptoms of IBS (see Table 1). In the cardiogenic group, abdominal angina, mesenteric artery thrombosis, and mesenteric artery venous thrombosis share common symptoms (eg, sudden stomach pain) with IBS, which may confuse the diagnostic picture. Gastrointestinal disorders such as bacterial overgrowth, celiac disease, gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and anorectal dysfunction (incontinence) should be considered in patients who present with IBS symptoms. Pancreatic, ovarian, and colorectal cancer should also be investigated as a possible diagnosis.4,5,7

Continued on next page >>

TREATMENT

Evidence supports a number of therapeutic options, both lifestyle and pharmacologic (see Table 2). Lifestyle options include comprehensive patient education, dietary manipulation, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and exercise. Pharmacologic options include antispasmodic agents, antidepressants, antidiarrheal agents, osmotic laxatives, alosetron, lubiprostone, rifaximin, and linaclotide.

Lifestyle changes

A therapeutic relationship that includes a nonjudgmental attitude, realistic expectations, and patient-directed care is the cornerstone of successful nonpharmacologic IBS management.4 In addition, patient education should emphasize management instead of cure, and the patient should be informed that IBS may wax and wane over a lifetime but will not shorten his/her lifespan.4

A six-week, single-blind, randomized trial (N = 262) attempted to assess the impact of patient–provider interaction on IBS symptoms and HRQOL. Participants were assigned to one of three groups: waiting list, limited intervention, and augmented intervention, with the last group receiving the greatest amount of education and patient–provider interaction. After three and six weeks, participants in the augmented group reported significant improvements in global IBS symptoms and HRQOL scores.8 Although these findings are limited by a short follow-up period, they underscore the importance of a strong therapeutic relationship in a successful outcome.

Diet. Since food sensitivities—to lactose; gluten; fiber; fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, and monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP); and carbohydrates—are thought to be integral to the etiology of IBS, dietary manipulation plays a major role in managing symptoms.4

Due to overlapping symptoms, a lactose-restricted diet may be appropriate in a subset of IBS-D and IBS-M patients. A prospective clinical trial enrolled 70 adult participants with IBS, 24% of whom were lactose intolerant. All participants were given a lactose-restricted diet for six weeks, and a significant improvement of IBS symptoms in the lactose-intolerant subgroup was observed. This subgroup was advised to continue a lactose-restricted diet and was then followed for five years. Of the 14 participants who remained in the study for the five years, none reported IBS complaints.9 While limited by its small sample size, this study supports the ACG recommendation to consider lactose hydrogen breath testing to screen for lactose-intolerance in a select group of patients with IBS symptoms.

Gluten. It has been observed that gluten withdrawal may improve IBS symptoms. A recent four-week randomized controlled trial (RCT; N = 45) evaluated the effect of gluten restriction on subjective markers including stool frequency, form, and ease of passage, and on objective markers related to intestinal function in adults with known IBS-D who did not have gluten sensitivity or celiac disease.10 Participants on the gluten-restricted diet reported a significant reduction in stool frequency, especially among those with HLA DQ2 and DQ8 genotypes. There was no effect on stool form or ease of passage.10

An RCT conducted by Biesiekierski and colleagues enrolled 30 patients with IBS who reported symptom control on a gluten-free diet.11 Study participants were randomly assigned to either a continued gluten-free diet or to a gluten-containing diet. Over the six-week

follow-up period, significantly more participants on a gluten-containing diet reported inadequate control of IBS symptoms.11 The small sample size and short follow-up period led the researchers to conclude that additional studies are needed to confirm whether gluten restriction attenuates IBS symptoms.

Fiber. Data are inconclusive regarding efficacy of fiber in reducing IBS symptoms. A subgroup of patients with IBS report increased abdominal pain and bloating when increasing their fiber intake.1 This was supported by a systematic review that found no clinical improvement in IBS symptoms with bulking agents.12 That said, patients with IBS-C may benefit from a trial of dietary fiber, which should be introduced at a low dose (eg, 1/2 to 1 Tb of wheat bran or psyllium daily) and titrated up as needed and tolerated.1

FODMAP. A number of clinical trials have suggested that there is a benefit to consuming a diet low in FODMAP foods (see chart). Shepherd and colleagues conducted an RCT (N = 25) that compared the effects of high- and low-FODMAP diets on IBS symptoms over a two-week period. Of participants in the high-FODMAP group, 79% reported inadequate IBS symptom control, while only 14% in the low-FODMAP group reported inadequate IBS symptom control.13

In a second trial (N = 30) that had similar objectives, symptoms worsened significantly on a

high-FODMAP diet compared to a low one among the IBS participants. Healthy participants experienced more flatulence on the high-FODMAP diet compared to those on a low one.14

Carbohydrates. In a small clinical trial (N = 17), IBS-D participants consumed a standard diet for two weeks followed by a very low carbohydrate diet (< 20 g/d) for four weeks. They were assessed weekly for adequate relief of IBS symptoms. For purposes of the study, a patient was considered a responder if he/she experienced adequate relief of IBS symptoms during at least two of the four treatment weeks. In addition to symptom relief, secondary measures included abdominal pain, stool frequency, stool consistency, and quality of life.15

Of the 13 participants who completed the study, all were considered responders; 10 of 13 (77%) reported adequate relief of IBS symptoms for four out of four treatment weeks. There were significant improvements in abdominal pain, stool frequency, stool consistency, and quality of life during treatment weeks.15 Additional trials with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

Exercise. Regular exercise not only offers general health benefits but may also simultaneously reduce IBS symptoms. An RCT (N =102) assigned patients with IBS either to their normal daily activity or to 20 to 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise three to five days a week. After 12 weeks, the exercise group showed decreased IBS symptom severity. They were also significantly less likely to report worsening IBS symptoms.16

Cognitive behavioral therapy. CBT may be helpful in reducing IBS symptoms. In an RCT (N = 75) that assigned patients with IBS to conventional CBT, self-administered CBT, or a control group, IBS symptoms improved significantly in those assigned to both CBT groups.17 A systematic review and meta-analysis reported a relative risk (RR) of persistent IBS symptoms with CBT of 0.67 and a number needed to treat (NNT) of 4.18

Continued on next page >>

Pharmacologic Treatment

Prescription and OTC medications serve an adjunctive role in the management of IBS.1 Efficacy trials in the IBS population are limited by disease heterogeneity, lack of disease markers, and high placebo response rates.19

Antispasmodics. Prescription antispasmodics, such as dicyclomine, have been shown to offer short-term relief of IBS-related abdominal pain; however, long-term outcomes are unknown. Possible adverse effects such as dizziness, dry mouth, blurred vision, and sluggishness may limit their use. Peppermint oil is considered an alternative to prescription antispasmodics and has been found to improve global IBS symptoms (RR, 2.25).12

Probiotics. A number of trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses have addressed the effect of probiotics on IBS symptoms. Meta-analyses found an RR of 0.72 to 0.77 for persistent IBS symptoms in patients using probiotics.20 Because probiotics can be beneficial, with relatively low cost and minimal associated risks, it is reasonable to consider a trial of probiotics, especially the specific strains offering the most promising results, such as Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 and Escherichia coli DSM 17252. Like most IBS treatments, it is unlikely that probiotics will benefit all IBS patients.20

Antidepressants. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were found to be effective in reducing the risk for persistent IBS symptoms in adults (RR, 0.66; NNT, 4).12,18 TCAs can slow gastrointestinal transit time, which may be beneficial to patients with IBS-D but a drawback to those with IBS-C. SSRIs, such as fluoxetine, are especially appropriate for patients with concurrent anxiety or depression. Note that three to four weeks of treatment with antidepressants are required to see benefits.1

Others. Loperamide has been reported to significantly improve stool frequency and consistency in patients with IBS-D and IBS-M but not global IBS symptoms.1,2 Polyethylene glycol has been shown to be effective in treating adults with isolated constipation, but it was not superior to placebo in adults with IBS-C.21

A systematic review found that the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist alosetron offered clinical benefit to patients with IBS-D and IBS-M.22 However, due to reports of ischemic colitis and severe constipation, the FDA removed the drug from the US market in 2000. Ultimately, postmarketing data and patient demand brought the drug back onto the market in 2002, but it can be prescribed only with careful regulation and only for women with severe, refractory IBS-D.23,24

A locally acting chloride channel activator, lubiprostone, offers clinical benefit to patients with IBS-C and chronic constipation.25 Because of its unknown long-term effects, high expense, and lack of comparison data to other IBS-C treatments, this drug should only be given to women with severe refractory IBS-C.26

Two large multicenter RCTs found that a two-week course of rifaximin, a nonabsorbable antibiotic, reduced global IBS symptoms, especially bloating, in patients with IBS without constipation. The benefits continued through 10 weeks of follow-up.27 Prescribing rifaximin for the treatment of IBS is an off-label use and should be limited to patients with IBS-D who have not responded to currently available symptom-directed therapies. In addition, the lack of evidence for long-term benefits as well as the potential for development of antibiotic resistance should be borne in mind when using this drug.28

Linaclotide is approved for IBS-C, based on two large RCTs with 12- and 26-week follow-up periods. Treatment group participants reported substantial improvement in IBS-C symptoms. Approximately 5% of participants discontinued treatment due to diarrhea.29,30

Continued on next page >>

CONCLUSION

IBS is a commonly occurring disorder of heterogeneous nature and pathogenesis. Therefore, basing a diagnosis on the presenting symptoms is not ideal; using clinical criteria to make a determination is more accurate. Once the diagnosis is made, IBS can be categorized into subtypes according to bowel function: diarrhea, constipation, or mixed. Knowing the subtype may guide the clinician in recommending a treatment, eg, patients with IBS-D may benefit from loperamide and those with IBS-C find relief with lubiprostone. The range of treatment strategies includes making lifestyle changes (eg, diet and exercise); incorporating CBT; and prescribing neuromotility agents and probiotics.

CE/CME No: CR-1401

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the criteria for diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

• List three dietary interventions that may reduce symptoms of IBS.

• Discuss the role of probiotics in the treatment of IBS.

• List three classes of prescription medication that may reduce symptoms of IBS.

FACULTY

Suzanne Martin is an Assistant Professor at the University of Utah College of Nursing and works as a family nurse practitioner at the University of Utah Student Health Center in Salt Lake City.

The author has no financial disclosures to report.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a functional gastrointestinal disorder usually manifesting with abdominal pain and altered bowel movements, is often seen in primary care. With the recent advances in evidence-based knowledge, you can now more readily make a diagnosis and offer your patients with IBS a variety of treatment options tailored to their needs.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common gastrointestinal complaint seen in both primary and gastroenterology clinics.1 Direct and indirect costs associated with IBS total more than $20 billion. Studies have shown that patients with IBS consume 50% more health care resources than matched controls. The prevalence of IBS ranges from less than 1% to more than 20%. Using strict criteria, the pooled prevalence rate of IBS in North America is 7%.1

IBS occurs more commonly in women and lower socioeconomic populations and is more likely to be diagnosed before age 50.1 Individuals with IBS report diminished health-related quality of life (HRQOL) scores compared to those without the disease. In some cases, decreased HRQOL can be severe, resulting in increased risk for suicidal behavior.1

The pathogenesis of IBS is not entirely understood. Contributing factors may include impaired gastrointestinal motility, visceral hypersensitivity, increased mucosal permeability, carbohydrate malabsorption, bacterial overgrowth, altered brain-gut axis, altered intestinal microbiota, psychosocial disturbances, and genetic predisposition.1,2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Hallmark symptoms of IBS are abdominal pain, dyspepsia, and altered bowel movements. The abdominal pain of IBS can be located anywhere and can range in severity from “annoying” to “debilitating” (see “Living with IBS,”). Eating and stress may aggravate pain, and a bowel movement may attenuate it. The pain is usually intermittent throughout the day; nocturnal pain is unusual and suggests an alternate cause.3

Dyspepsia (epigastric discomfort, postprandial fullness, early satiety) can occur in up to 87% of patients with IBS.4 Other features associated with IBS include gastroesophageal reflux disease nausea; noncardiac chest pain; bloating, belching and/or flatulence; sexual dysfunction; dyspareunia; urinary frequency and urgency; and fibromyalgia.

The patient with IBS will also experience a change in the type of bowel movement. Therefore, IBS is often categorized according to the predominant change: diarrhea (known as IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), and alternating diarrhea and constipation (IBS-M). IBS-D is defined by diarrhea that is typically small to moderate in volume, occurs after meals or in the morning, and is associated with mucus 50% of the time.4 IBS-C is characterized by constipation with stools that are typically hard and pelletlike, accompanied by straining, with fewer than three bowel movements per week.

Patients with IBS may describe a sense of incomplete evacuation.4 Alarm signs and symptoms, which include progressive symptoms; nocturnal symptoms; weight loss, malnutrition, and anorexia; stools that are large in volume, bloody, or greasy; anemia, electrolyte disturbance, and elevated inflammatory markers; or a family history of inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, or celiac disease, should prompt evaluation for alternate etiologies.1,4

Continued on next page >>

DIAGNOSIS

Work-up

Although the patient with IBS may present with mild nonspecific abdominal pain, the physical exam is typically normal.4,5 Patients who meet the Rome III diagnostic criteria—in the absence of alarm signs and symptoms or worrisome family history—are candidates for a clinical diagnosis of IBS.6 These criteria, originally developed for research purposes but useful in a clinical setting, include

• Symptom onset at least six months prior to diagnosis

• Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort for more than three days per month during the past three months, and at least two of the following features:

• Improvement of symptoms with defecation

• A change in stool frequency

• A change in stool form.1,4,6

Due to inherent difficulty in establishing the accuracy of such criteria, a simple and practical alternative clinical definition is suggested by the American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on IBS: IBS is characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort that occurs in association with altered bowel habits over a period of at least three months.1 Patients meeting clinical criteria without alarm symptoms or worrisome family history require no additional testing.1

Moderate evidence supports routine testing for celiac disease in individuals presenting with symptoms consistent with IBS-D or IBS-M.1 Lactose hydrogen breath testing is recommended for individuals reporting symptoms that suggest a correlation between the ingestion of lactose and onset of IBS symptoms.1 When a patient presents with alarm features, significant family history, refractory symptoms, or new concerning symptoms, further testing is indicated, with test selection based on specific symptoms and risk factors.1,4,5

Differential Diagnosis

In addition to IBS, there are numerous other conditions spanning several clinical categories that should be considered in patients who present with symptoms of IBS (see Table 1). In the cardiogenic group, abdominal angina, mesenteric artery thrombosis, and mesenteric artery venous thrombosis share common symptoms (eg, sudden stomach pain) with IBS, which may confuse the diagnostic picture. Gastrointestinal disorders such as bacterial overgrowth, celiac disease, gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and anorectal dysfunction (incontinence) should be considered in patients who present with IBS symptoms. Pancreatic, ovarian, and colorectal cancer should also be investigated as a possible diagnosis.4,5,7

Continued on next page >>

TREATMENT

Evidence supports a number of therapeutic options, both lifestyle and pharmacologic (see Table 2). Lifestyle options include comprehensive patient education, dietary manipulation, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and exercise. Pharmacologic options include antispasmodic agents, antidepressants, antidiarrheal agents, osmotic laxatives, alosetron, lubiprostone, rifaximin, and linaclotide.

Lifestyle changes

A therapeutic relationship that includes a nonjudgmental attitude, realistic expectations, and patient-directed care is the cornerstone of successful nonpharmacologic IBS management.4 In addition, patient education should emphasize management instead of cure, and the patient should be informed that IBS may wax and wane over a lifetime but will not shorten his/her lifespan.4

A six-week, single-blind, randomized trial (N = 262) attempted to assess the impact of patient–provider interaction on IBS symptoms and HRQOL. Participants were assigned to one of three groups: waiting list, limited intervention, and augmented intervention, with the last group receiving the greatest amount of education and patient–provider interaction. After three and six weeks, participants in the augmented group reported significant improvements in global IBS symptoms and HRQOL scores.8 Although these findings are limited by a short follow-up period, they underscore the importance of a strong therapeutic relationship in a successful outcome.

Diet. Since food sensitivities—to lactose; gluten; fiber; fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, and monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP); and carbohydrates—are thought to be integral to the etiology of IBS, dietary manipulation plays a major role in managing symptoms.4

Due to overlapping symptoms, a lactose-restricted diet may be appropriate in a subset of IBS-D and IBS-M patients. A prospective clinical trial enrolled 70 adult participants with IBS, 24% of whom were lactose intolerant. All participants were given a lactose-restricted diet for six weeks, and a significant improvement of IBS symptoms in the lactose-intolerant subgroup was observed. This subgroup was advised to continue a lactose-restricted diet and was then followed for five years. Of the 14 participants who remained in the study for the five years, none reported IBS complaints.9 While limited by its small sample size, this study supports the ACG recommendation to consider lactose hydrogen breath testing to screen for lactose-intolerance in a select group of patients with IBS symptoms.

Gluten. It has been observed that gluten withdrawal may improve IBS symptoms. A recent four-week randomized controlled trial (RCT; N = 45) evaluated the effect of gluten restriction on subjective markers including stool frequency, form, and ease of passage, and on objective markers related to intestinal function in adults with known IBS-D who did not have gluten sensitivity or celiac disease.10 Participants on the gluten-restricted diet reported a significant reduction in stool frequency, especially among those with HLA DQ2 and DQ8 genotypes. There was no effect on stool form or ease of passage.10

An RCT conducted by Biesiekierski and colleagues enrolled 30 patients with IBS who reported symptom control on a gluten-free diet.11 Study participants were randomly assigned to either a continued gluten-free diet or to a gluten-containing diet. Over the six-week

follow-up period, significantly more participants on a gluten-containing diet reported inadequate control of IBS symptoms.11 The small sample size and short follow-up period led the researchers to conclude that additional studies are needed to confirm whether gluten restriction attenuates IBS symptoms.

Fiber. Data are inconclusive regarding efficacy of fiber in reducing IBS symptoms. A subgroup of patients with IBS report increased abdominal pain and bloating when increasing their fiber intake.1 This was supported by a systematic review that found no clinical improvement in IBS symptoms with bulking agents.12 That said, patients with IBS-C may benefit from a trial of dietary fiber, which should be introduced at a low dose (eg, 1/2 to 1 Tb of wheat bran or psyllium daily) and titrated up as needed and tolerated.1

FODMAP. A number of clinical trials have suggested that there is a benefit to consuming a diet low in FODMAP foods (see chart). Shepherd and colleagues conducted an RCT (N = 25) that compared the effects of high- and low-FODMAP diets on IBS symptoms over a two-week period. Of participants in the high-FODMAP group, 79% reported inadequate IBS symptom control, while only 14% in the low-FODMAP group reported inadequate IBS symptom control.13

In a second trial (N = 30) that had similar objectives, symptoms worsened significantly on a

high-FODMAP diet compared to a low one among the IBS participants. Healthy participants experienced more flatulence on the high-FODMAP diet compared to those on a low one.14

Carbohydrates. In a small clinical trial (N = 17), IBS-D participants consumed a standard diet for two weeks followed by a very low carbohydrate diet (< 20 g/d) for four weeks. They were assessed weekly for adequate relief of IBS symptoms. For purposes of the study, a patient was considered a responder if he/she experienced adequate relief of IBS symptoms during at least two of the four treatment weeks. In addition to symptom relief, secondary measures included abdominal pain, stool frequency, stool consistency, and quality of life.15

Of the 13 participants who completed the study, all were considered responders; 10 of 13 (77%) reported adequate relief of IBS symptoms for four out of four treatment weeks. There were significant improvements in abdominal pain, stool frequency, stool consistency, and quality of life during treatment weeks.15 Additional trials with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

Exercise. Regular exercise not only offers general health benefits but may also simultaneously reduce IBS symptoms. An RCT (N =102) assigned patients with IBS either to their normal daily activity or to 20 to 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise three to five days a week. After 12 weeks, the exercise group showed decreased IBS symptom severity. They were also significantly less likely to report worsening IBS symptoms.16

Cognitive behavioral therapy. CBT may be helpful in reducing IBS symptoms. In an RCT (N = 75) that assigned patients with IBS to conventional CBT, self-administered CBT, or a control group, IBS symptoms improved significantly in those assigned to both CBT groups.17 A systematic review and meta-analysis reported a relative risk (RR) of persistent IBS symptoms with CBT of 0.67 and a number needed to treat (NNT) of 4.18

Continued on next page >>

Pharmacologic Treatment

Prescription and OTC medications serve an adjunctive role in the management of IBS.1 Efficacy trials in the IBS population are limited by disease heterogeneity, lack of disease markers, and high placebo response rates.19

Antispasmodics. Prescription antispasmodics, such as dicyclomine, have been shown to offer short-term relief of IBS-related abdominal pain; however, long-term outcomes are unknown. Possible adverse effects such as dizziness, dry mouth, blurred vision, and sluggishness may limit their use. Peppermint oil is considered an alternative to prescription antispasmodics and has been found to improve global IBS symptoms (RR, 2.25).12

Probiotics. A number of trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses have addressed the effect of probiotics on IBS symptoms. Meta-analyses found an RR of 0.72 to 0.77 for persistent IBS symptoms in patients using probiotics.20 Because probiotics can be beneficial, with relatively low cost and minimal associated risks, it is reasonable to consider a trial of probiotics, especially the specific strains offering the most promising results, such as Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 and Escherichia coli DSM 17252. Like most IBS treatments, it is unlikely that probiotics will benefit all IBS patients.20

Antidepressants. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were found to be effective in reducing the risk for persistent IBS symptoms in adults (RR, 0.66; NNT, 4).12,18 TCAs can slow gastrointestinal transit time, which may be beneficial to patients with IBS-D but a drawback to those with IBS-C. SSRIs, such as fluoxetine, are especially appropriate for patients with concurrent anxiety or depression. Note that three to four weeks of treatment with antidepressants are required to see benefits.1

Others. Loperamide has been reported to significantly improve stool frequency and consistency in patients with IBS-D and IBS-M but not global IBS symptoms.1,2 Polyethylene glycol has been shown to be effective in treating adults with isolated constipation, but it was not superior to placebo in adults with IBS-C.21

A systematic review found that the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist alosetron offered clinical benefit to patients with IBS-D and IBS-M.22 However, due to reports of ischemic colitis and severe constipation, the FDA removed the drug from the US market in 2000. Ultimately, postmarketing data and patient demand brought the drug back onto the market in 2002, but it can be prescribed only with careful regulation and only for women with severe, refractory IBS-D.23,24

A locally acting chloride channel activator, lubiprostone, offers clinical benefit to patients with IBS-C and chronic constipation.25 Because of its unknown long-term effects, high expense, and lack of comparison data to other IBS-C treatments, this drug should only be given to women with severe refractory IBS-C.26

Two large multicenter RCTs found that a two-week course of rifaximin, a nonabsorbable antibiotic, reduced global IBS symptoms, especially bloating, in patients with IBS without constipation. The benefits continued through 10 weeks of follow-up.27 Prescribing rifaximin for the treatment of IBS is an off-label use and should be limited to patients with IBS-D who have not responded to currently available symptom-directed therapies. In addition, the lack of evidence for long-term benefits as well as the potential for development of antibiotic resistance should be borne in mind when using this drug.28

Linaclotide is approved for IBS-C, based on two large RCTs with 12- and 26-week follow-up periods. Treatment group participants reported substantial improvement in IBS-C symptoms. Approximately 5% of participants discontinued treatment due to diarrhea.29,30

Continued on next page >>

CONCLUSION

IBS is a commonly occurring disorder of heterogeneous nature and pathogenesis. Therefore, basing a diagnosis on the presenting symptoms is not ideal; using clinical criteria to make a determination is more accurate. Once the diagnosis is made, IBS can be categorized into subtypes according to bowel function: diarrhea, constipation, or mixed. Knowing the subtype may guide the clinician in recommending a treatment, eg, patients with IBS-D may benefit from loperamide and those with IBS-C find relief with lubiprostone. The range of treatment strategies includes making lifestyle changes (eg, diet and exercise); incorporating CBT; and prescribing neuromotility agents and probiotics.

1. Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, et al; American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(suppl 1):S1-S35.

2. Wald A. Irritable bowel syndrome—diarrhoea. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:573-580.

3. Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108-2131.

4. World Gastroenterology Organization. Irritable bowel syndrome: a global perspective (2009). www.worldgastroenterology.org/assets/downloads/en/pdf/guidelines/20_irritable_bowel_syndrome.pdf. Accessed December 16, 2013.

5. Olden KW. Diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1701-1714.

6. Engsbro AL, Begtrup LM, Kjeldsen J, et al. Patients suspected of irritable bowel syndrome—cross-sectional study exploring the sensitivity of Rome III criteria in primary care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:972-980.

7. Lehrer JK. Irritable bowel syndrome differential diagnoses. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/180389-overview. Accessed December 16, 2013.

8. Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 2008;336:999-1003.

9. Böhmer CJ, Tuynman HA. The effect of a lactose-restricted diet in patients with a positive lactose tolerance test, earlier diagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome: a 5-year follow-up study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001; 13:941-944.

10. Vazquez-Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:903-911.

11. Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:508-514.

12. Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10(8):CD003460.

13. Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir G, Gibson PR. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:765-771.

14. Ong DK, Mitchell SB, Barrett JS, et al. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1366-1373.

15. Austin GL, Dalton CB, Hu Y, et al. A very low-carbohydrate diet improves symptoms and quality of life in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:706-708.

16. Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, et al. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:915-922.

17. Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS, et al. Self-administered cognitive behavior therapy for moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome: clinical efficacy, tolerability, feasibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:899-906.

18. Ford AC, Talley NJ, Schoenfeld PS, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2009;58:367-378.

19. Jailwala J, Imperiale TF, Kroenke K. Pharmacologic treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:136-147.

20. Parkes GC, Sanderson JD, Whelan K. Treating irritable bowel syndrome with probiotics: the evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69:187-194.

21. Awad RA, Camacho S. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of polyethylene glycol effects on fasting and postprandial rectal sensitivity and symptoms in hypersensitive constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:1131-1138.

22. Andresen V, Montori VM, Keller J, et al. Effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) type 3 antagonists on symptom relief and constipation in nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6: 545-555.

23. FDA. Lotronex (alosetron hydrochloride) tablets. www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/safetyinformation/safetyalertsforhumanmedicalproducts/ucm172946.htm. Accessed December 16, 2013.

24. FDA. Lotronex (alosetron hydrochloride) information. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm110450.htm. Accessed December 16, 2013.

25. Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, et al. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome—results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:329-341.

26. Lunsford TN, Harris LA. Lubiprostone: evaluation of the newest medication for the treatment of adult women with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Womens Health. 2010;2:361-374.

27. Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al; TARGET Study Group. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation.

N Engl J Med. 2011;364:22-32.

28. Tack J. Antibiotic therapy for the irritable bowel syndrome.N Engl J Med. 2011;364:81-82.

29. Rao S, Lembo AJ, Shiff SJ, et al. A 12-week, randomized, controlled trial with a 4-week randomized withdrawal period to evaluate the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1714-1724.

30. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Lavins BJ, et al. Linaclotide for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1702-1712.

31. Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: the FODMAP approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:252-258.

32. Magge S, Lembo A. Low-FODMAP diet for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;8:739-745.

1. Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, et al; American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(suppl 1):S1-S35.

2. Wald A. Irritable bowel syndrome—diarrhoea. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:573-580.

3. Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108-2131.

4. World Gastroenterology Organization. Irritable bowel syndrome: a global perspective (2009). www.worldgastroenterology.org/assets/downloads/en/pdf/guidelines/20_irritable_bowel_syndrome.pdf. Accessed December 16, 2013.

5. Olden KW. Diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1701-1714.

6. Engsbro AL, Begtrup LM, Kjeldsen J, et al. Patients suspected of irritable bowel syndrome—cross-sectional study exploring the sensitivity of Rome III criteria in primary care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:972-980.

7. Lehrer JK. Irritable bowel syndrome differential diagnoses. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/180389-overview. Accessed December 16, 2013.

8. Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 2008;336:999-1003.

9. Böhmer CJ, Tuynman HA. The effect of a lactose-restricted diet in patients with a positive lactose tolerance test, earlier diagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome: a 5-year follow-up study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001; 13:941-944.

10. Vazquez-Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:903-911.

11. Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:508-514.

12. Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10(8):CD003460.

13. Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir G, Gibson PR. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:765-771.

14. Ong DK, Mitchell SB, Barrett JS, et al. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1366-1373.

15. Austin GL, Dalton CB, Hu Y, et al. A very low-carbohydrate diet improves symptoms and quality of life in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:706-708.

16. Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, et al. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:915-922.

17. Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS, et al. Self-administered cognitive behavior therapy for moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome: clinical efficacy, tolerability, feasibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:899-906.

18. Ford AC, Talley NJ, Schoenfeld PS, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2009;58:367-378.

19. Jailwala J, Imperiale TF, Kroenke K. Pharmacologic treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:136-147.

20. Parkes GC, Sanderson JD, Whelan K. Treating irritable bowel syndrome with probiotics: the evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69:187-194.

21. Awad RA, Camacho S. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of polyethylene glycol effects on fasting and postprandial rectal sensitivity and symptoms in hypersensitive constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:1131-1138.

22. Andresen V, Montori VM, Keller J, et al. Effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) type 3 antagonists on symptom relief and constipation in nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6: 545-555.

23. FDA. Lotronex (alosetron hydrochloride) tablets. www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/safetyinformation/safetyalertsforhumanmedicalproducts/ucm172946.htm. Accessed December 16, 2013.

24. FDA. Lotronex (alosetron hydrochloride) information. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm110450.htm. Accessed December 16, 2013.

25. Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, et al. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome—results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:329-341.

26. Lunsford TN, Harris LA. Lubiprostone: evaluation of the newest medication for the treatment of adult women with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Womens Health. 2010;2:361-374.

27. Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al; TARGET Study Group. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation.

N Engl J Med. 2011;364:22-32.

28. Tack J. Antibiotic therapy for the irritable bowel syndrome.N Engl J Med. 2011;364:81-82.

29. Rao S, Lembo AJ, Shiff SJ, et al. A 12-week, randomized, controlled trial with a 4-week randomized withdrawal period to evaluate the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1714-1724.

30. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Lavins BJ, et al. Linaclotide for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1702-1712.

31. Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: the FODMAP approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:252-258.

32. Magge S, Lembo A. Low-FODMAP diet for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;8:739-745.