User login

From Abington Health, Abington, PA (Ms. Walter) and Duquesne University School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA (Dr. Guimond).

Abstract

- Background: National coverage rates for many recommended adult vaccines are low. Tetanus toxoid, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) and pneumococcal vaccination rates among adults are 20% and 16%, respectively. To address these low rates in our practice, we identified missed opportunities for vaccination as a target for improvement.

- Objective: To examine the effectiveness of a vaccine reminder checklist at the point of care and assess providers’ perceived vaccine practices.

- Methods: The quick sample method was used to assess pre- and post-intervention pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPSV) and Tdap vaccination rates among the target population (adults 18-64 for Tdap; high-risk adults 18-64 for PPSV). A post-intervention survey was used to assess providers’ adult vaccination practices and their opinion of the reminder tool.

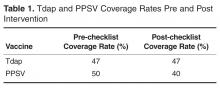

- Results: The Tdap vaccination rate did not change and was constant at 47%. PPSV vaccination rates decreased from 50% to 40%. Among the providers, 47% reported ordering immunizations at sick visits, as compared to 76% at follow-up visits. The providers reported the reminder checklist was useful for determining a patient’s eligibility for a vaccine.

- Conclusion: No improvement in vaccination rates was detected for this project, which may be partially explained by challenges originating at patient check-in. In the future, buy-in from all staff in our practice setting will be sought. Results indicate that providers may hesitate to administer immunizations at sick visits and may need education on vaccination contraindications.

Vaccines are an important public health tool that offer safe and effective protection against certain diseases and reduce the health care burden [1,2]. Missed opportunities to vaccinate, defined as any primary care encounter in which a patient eligible for a vaccine is not administered a vaccine, lead to suboptimal immunization coverage among adults. Providers have been urged to review patients’ vaccine status at every patient encounter [3]. Rates of vaccinations recommended in 2012 by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) remain low [4], particularly coverage rates for tetanus toxoid, diphtheria, and acelluar pertussis vaccine (Tdap) vaccine among adults, and for pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV) among high-risk adults [2]. Nationally, uptake rates are approximately 16% for Tdap and 20% for pneumococcal vaccines among eligible adults aged 18 to 64 years [5]. These low uptake rates suggest that programs are needed to reduce missed opportunities to vaccinate and improve vaccination rates among adults.

There is a strong case for improving Tdap and pneumococcal vaccination uptake among high-risk adults. Since the 1970s, the incidence of pertussis in the United States has increased substantially, with numbers of reported cases reaching as high as 48,277 and 28,639 in 2012 and 2013, respectively [2]. Some states experienced epidemic levels of pertussis [2,6]. Pertussis is often fatal among infected infants, and infection in adolescents and adults may cost upwards of $800 per case [7,8]. In 2005, high-risk adults for whom the PPSV was indicated accounted for half of the 40,000 pneumococcal infections in the United States [9]. PPSV boasts a 50% to 80% effectiveness rate in preventing pneumococcal disease among high-risk patients [9]. In a CDC cost-effectiveness analysis, immunization of immunocompromised patients with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-13) at the time of diagnosis followed with PPSV vaccinations starting 1 year later led to savings of $7.6 million, added 1360 quality-adjusted life years, and prevented 57 cases of invasive pneumococcal disease [10].

Recognizing and overcoming practice-specific barriers to vaccinating adults are needed to improve uptake. A lack of patient- and provider-focused reminders may lead to missed opportunities to vaccinate [11,12]. Provider and patient-focused reminder tools can be effective in increasing vaccine uptake [1,13,14], but interventions that combine reminder tools with patient outreach may be more effective [15]. Furthermore, involving an interdisciplinary team to coordinate the administration of vaccines among adults may improve vaccine uptake rates [16]. These studies suggested the need to determine a standard, effective reminder tool and incorporate multilevel interventions to increase uptake of adult vaccines.

An informal electronic query at a large, suburban family practice revealed approximately 30% Tdap and PPSV coverage rates among eligible adults served by the practice, suggesting that providers fail to assess patients’ vaccine status at every opportunity. Electronic medical records provide no alerts for vaccines that may be due. PPSV and Tdap uptake rates were chosen for this quality improvement project to address low baseline coverage rates among adults. The objective of this project was to increase adult Tdap and 23-valent PPSV uptake rates using a reminder checklist at the point of care. A secondary objective was to assess providers’ vaccination practices during various types of visits, appraise their perceived vaccination practices and barriers to vaccinating adults, and to determine providers’ perceived effectiveness of the reminder checklist.

Methods

This quality improvement project was implemented in a large family practice that is home to a family medicine residency program. Approximately two-thirds of the patients served are adults, over half of whom are minorities, and nearly half are on Medicaid or underinsured. Providers in the practice included 21 resident physicians, 8 attending physicians, and 1 nurse practitioner who served as the primary investigator. Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained.

Measures included pre- and post-intervention vaccination rates for Tdap and PPSV, the providers’ perceived vaccination practices during various types of visits, the providers’ perceptions of practice-specific barriers to vaccinating adults, and the providers’ perceived usefulness of a vaccine checklist. To evaluate the effect of the reminder tool on immunization rates, we conducted a chart review. A random sample of 30 charts was derived separately for each vaccine, pre- and post-intervention, by selecting every 5th chart via the electronic health record after filtering for vaccine eligibility. Eligibility for the vaccines was based on age, vaccine history, and diagnoses noted in the medical history and problem list.

After the 3-month intervention period, an 18-item survey was distributed to participating providers to assess their vaccination practices, their perception of practice-related barriers to vaccinating, and their perception of the use of the checklist at the point of care. The survey included 5 demographic items, 5 Yes/No questions asking about the providers’ vaccination practices (adapted from [18]), and 8 questions asking about the providers’ perceptions of practice-specific vaccination barriers and the usefulness of the checklist. For these 8 questions providers were asked to choose a response along a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

Results

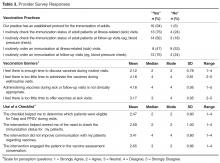

All providers responded to the vaccination practice-related questions. These questions and the frequency of responses are presented in Table 3. At follow-up visits, such as those for blood pressure checks, 82% of the providers stated they checked the patient’s immunization status and 76% of providers stated they ordered an immunization. In contrast, although 76% of providers indicated they checked the immunization status, only 47% noted they routinely ordered a vaccine at a sick visit. A Fisher’s exact test of independence to examine the relationship between providers’ years of experience and decision to vaccinate at sick visits revealed a result that was not significant (P = 1).

Discussion and Lessons Learned

Introduction of the reminder checklist at the point of care did not improve the administration or uptake of Tdap or PPSV during the intervention period. Limitations to our analysis include the small sample size. Also, this project was conducted in the fall, when influenza vaccines are usually given and providers may be more attuned to checking for vaccine eligibility. Future iterations of the project may be conducted to allow for samples over several months and use a process control chart to retrieve a more representative sample of participants from each vaccine-eligible group in the practice.

Usage of a paper reminder system after implementation of an electronic health record may have affected the results. Providers who are focused on the computer documentation may have overlooked paper reminders unless patients asked about vaccination. Although the checklist was printed on bright green paper as a visual cue, patients’ failure to present the reminder to providers undermined effectiveness of the paper system. In another study that used pre-visit paper reminders to improve physician performance on measures of chronic disease and preventive care, no benefit was found [19]. Developers of future vaccination programs should consider integrating reminder systems into the current system to mitigate this potential obstacle.

Staff and practice-related barriers may have also contributed to the limited success of the reminder checklist. Staff informally cited a paperwork burden as a challenge for patients. Informal feedback indicated that patients did not fully understand the questionnaire and often did not complete the form, even after being requested and instructed to do so. A systematic review of barriers to the use of reminders for immunizations showed that reminders can be perceived as disruptive to workflow and therefore not implemented or maintained [20]. These findings were congruent with behavior demonstrated by the office staff in the practice, whose buy-in to using the intervention waned over the course of the project. The front office staff needed reinforcement to continue the intervention as time passed. Informal interviews with staff suggested that patients who could have been given a checklist at the front desk did not receive it. These possibilities underline limitations in the study. Future projects may include collecting data such as perceptions of the office staff involved with vaccine interventions and proportion of patients who receive and complete the reminder checklist. A regression analysis is recommended to identify barriers that are more likely to decrease the likelihood of vaccination.

Providers’ responses to survey questions yielded insights into surveyed providers’ perceptions re the importance of immunizing adults and the use of the reminder checklist as an intervention. The majority of the providers (n = 16, 94%) acknowledged that the office had a procedure in place for immunization of adults. Review of the protocol and more vaccine education may be needed to increase providers’ knowledge of adult vaccine indications. Responses to survey questions related to vaccination barriers suggested that providers believed there was adequate time to assess for and order vaccines at routine visits. The possibility exists that an additional barrier may be present that was not uncovered by this project. Further investigation is needed to determine practice-barriers to administering vaccinations to adults at all types of visits for health care.

The findings of this review suggest that missed opportunities to vaccinate continue to exist. This project revealed that sick and problem visits may be an area warranting further exploration for opportunities to vaccinate adults. Survey findings that 76% of providers in the practice routinely check the immunization status of adult patients at sick visits and only 47% routinely order an immunization at sick visits point to the need in future vaccination programs to target sick visits as opportunities to increase adult vaccine administration. In other studies, years of experience has not been well correlated with performance of evidence based practice [21]. However, in our study, no relationship was identified between years of practice and decision to vaccinate during a sick visit. Follow-up visits, for which 76% of the surveyed providers reported ordering immunization, are another opportunity for improvement. A survey of pediatricians and family physicians regarding their adolescent patient vaccination practices revealed similar low rates for both checking the immunization status and administering vaccinations at sick and follow-up visits [18]. Based on these findings, a larger scale review is warranted that focuses on sick and follow-up visits to determine the rate of vaccination at these visits, barriers to vaccinating at sick and follow-up visits, and successful interventions to increase vaccination rates during these encounters.

Providers’ perceived vaccination behaviors at sick and follow-up visits may be related to time restrictions resulting from shorter appointments as well as providers’ varying degrees of comfort with offering vaccines during those visits. In addition, misunderstanding of vaccination contraindications has led to missed opportunities to vaccinate women and children [22] and this may apply to adults as well. Providers need to be aware of the true contraindications to vaccines. Mild acute illness is neither a contraindication nor a precaution to administering a vaccine [23]. Future projects may also focus on educating providers (at all levels of experience) regarding the safety and efficacy of administering vaccinations during illness-related visits and actual contraindications.

Also, to address time constraints during sick and follow-up visits, making the entire practice responsible for vaccination assessment and administration should be more widely employed to reduce the burden on the primary care provider. A successful model for increasing uptake involves using teamwork [16] among clinical and non-clinical staff. Successful implementation of an adult vaccination program may be improved by using a similar approach that will increase staff buy-in and accountability.

Conclusion

While care providers in this project generally perceived the reminder checklist at the point of care as helpful as a provider reminder, a patient engager, and a tool to determine vaccine eligibility, it was not effective in increasing Tdap or PPSV coverage among adult patients in the practice. Practice and workflow-related barriers to success of the intervention imply the need for careful consideration of the type of reminder system put in place in various practices. Hesitation to vaccinate during illness-related and follow-up visits denotes the need for further education of providers regarding true contraindications to particular vaccinations and further investigation of ways to make immunizing a collective responsibility shared by the patient, the office staff, and the primary and ancillary providers.

Corresponding author: Dyllan Walter, DNP, CRNP, North Hills Health Center, 212 Girard Ave., Glenside, PA 19038, dyllan79@yahoo.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Stone EG, Morton SC, Hulscher ME, et al. Interventions that increase use of adult immunization and cancer screening services: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:641–51.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis outbreak trends. 2015. Available at www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks/trends.html.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Standards for adult immunization practice. 2014. Available at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/patient-ed/adults/for-practice/standards.html.

4. Bridges CB. Adult immunization in the United States: 2012 update. Available at www.womeningovernment.org/files/file/CarolynBridges.pdf

5. Williams WW, Lu P-J, O’Halloran A, et al. Noninfluenza vaccination coverage among adults—United States, 2012. MMWR 2014;63:95–102.

6. Winter K, Glaser C, Watt J, Harriman K; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pertussis epidemic--California, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:1129–32.

7. Grizas AP, Camenga D, Vázquez M. Cocooning: A concept to protect young children from infectious diseases. Curr Opin Pediatr 2012;24:92–7.

8. Gidengil CA, Sandora TJ, Lee GM. Tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccination of adults in the USA. Expert Rev Vaccines 2008;7:621–34.

9. Wolfe RM. Update on adult immunizations. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:496–510.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2012;61:816–19.

11. Head KJ, Vanderpool RC, Mills LA. Health care providers’ perspectives on low HPV vaccine uptake and adherence in Appalachian Kentucky. Public Health Nurs 2013;30:351–60.

12. Perkins RB, Clark JA. What affects human papilloma virus vaccination rates? A qualitative analysis of providers’ perceptions. Womens Health Issues 2012;22:e379–86.

13. Thomas RE, Russell ML, Lorenzetti DL. Systematic review of interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates of those 60 years and older. Vaccine 2010;28:1684–70.

14. Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:97–140.

15. Humiston SG, Bennett NM, Long C, et al. Increasing inner-city adult influenza vaccination rates: A randomized controlled trial. Public Health Rep 2011;126:39–47.

16. Gannon M, Qaseem A, Snooks Q, Snow V. Improving adult immunization practices using a team approach in the primary setting. Am J Public Health 2012;102:e46–e52.

17. Immunization Action Coalition. Do I need any vaccinations today? 2014. Available at www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4036.pdf.

18. Schaffer SJ, Humiston SG, Shone LP, et al. Adolescent immunization practices: A national survey of US physicians. Arch Pediat Adol Med 2001;155:566–71.

19. Baker DW, Persell SD, Kho AN, et al. The marginal value of pre-visit paper reminders when added to a multifaceted electronic health record based quality improvement system. J Am Med Informat Assoc 2011;18:805–11.

20. Pereira JA, Quach S, Heidebrecht CL, et al. Barriers to the use of reminder/recall interventions for immunizations: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012;12:145.

21. Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: The relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:260–73.

22. Hutchins SS, Jansen HAFM, Robertson SE, et al. Missed opportunities for immunization: review of studies from developing and industrialized countries. Bull World Health Org 1993;71:549–60.

23. Immunization Action Coalition. Precautions and contraindications. 2015. Available at www.immunize.org/askexperts/precautions-contraindications.asp.

From Abington Health, Abington, PA (Ms. Walter) and Duquesne University School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA (Dr. Guimond).

Abstract

- Background: National coverage rates for many recommended adult vaccines are low. Tetanus toxoid, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) and pneumococcal vaccination rates among adults are 20% and 16%, respectively. To address these low rates in our practice, we identified missed opportunities for vaccination as a target for improvement.

- Objective: To examine the effectiveness of a vaccine reminder checklist at the point of care and assess providers’ perceived vaccine practices.

- Methods: The quick sample method was used to assess pre- and post-intervention pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPSV) and Tdap vaccination rates among the target population (adults 18-64 for Tdap; high-risk adults 18-64 for PPSV). A post-intervention survey was used to assess providers’ adult vaccination practices and their opinion of the reminder tool.

- Results: The Tdap vaccination rate did not change and was constant at 47%. PPSV vaccination rates decreased from 50% to 40%. Among the providers, 47% reported ordering immunizations at sick visits, as compared to 76% at follow-up visits. The providers reported the reminder checklist was useful for determining a patient’s eligibility for a vaccine.

- Conclusion: No improvement in vaccination rates was detected for this project, which may be partially explained by challenges originating at patient check-in. In the future, buy-in from all staff in our practice setting will be sought. Results indicate that providers may hesitate to administer immunizations at sick visits and may need education on vaccination contraindications.

Vaccines are an important public health tool that offer safe and effective protection against certain diseases and reduce the health care burden [1,2]. Missed opportunities to vaccinate, defined as any primary care encounter in which a patient eligible for a vaccine is not administered a vaccine, lead to suboptimal immunization coverage among adults. Providers have been urged to review patients’ vaccine status at every patient encounter [3]. Rates of vaccinations recommended in 2012 by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) remain low [4], particularly coverage rates for tetanus toxoid, diphtheria, and acelluar pertussis vaccine (Tdap) vaccine among adults, and for pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV) among high-risk adults [2]. Nationally, uptake rates are approximately 16% for Tdap and 20% for pneumococcal vaccines among eligible adults aged 18 to 64 years [5]. These low uptake rates suggest that programs are needed to reduce missed opportunities to vaccinate and improve vaccination rates among adults.

There is a strong case for improving Tdap and pneumococcal vaccination uptake among high-risk adults. Since the 1970s, the incidence of pertussis in the United States has increased substantially, with numbers of reported cases reaching as high as 48,277 and 28,639 in 2012 and 2013, respectively [2]. Some states experienced epidemic levels of pertussis [2,6]. Pertussis is often fatal among infected infants, and infection in adolescents and adults may cost upwards of $800 per case [7,8]. In 2005, high-risk adults for whom the PPSV was indicated accounted for half of the 40,000 pneumococcal infections in the United States [9]. PPSV boasts a 50% to 80% effectiveness rate in preventing pneumococcal disease among high-risk patients [9]. In a CDC cost-effectiveness analysis, immunization of immunocompromised patients with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-13) at the time of diagnosis followed with PPSV vaccinations starting 1 year later led to savings of $7.6 million, added 1360 quality-adjusted life years, and prevented 57 cases of invasive pneumococcal disease [10].

Recognizing and overcoming practice-specific barriers to vaccinating adults are needed to improve uptake. A lack of patient- and provider-focused reminders may lead to missed opportunities to vaccinate [11,12]. Provider and patient-focused reminder tools can be effective in increasing vaccine uptake [1,13,14], but interventions that combine reminder tools with patient outreach may be more effective [15]. Furthermore, involving an interdisciplinary team to coordinate the administration of vaccines among adults may improve vaccine uptake rates [16]. These studies suggested the need to determine a standard, effective reminder tool and incorporate multilevel interventions to increase uptake of adult vaccines.

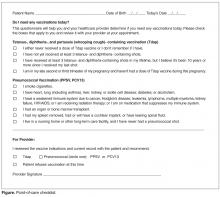

An informal electronic query at a large, suburban family practice revealed approximately 30% Tdap and PPSV coverage rates among eligible adults served by the practice, suggesting that providers fail to assess patients’ vaccine status at every opportunity. Electronic medical records provide no alerts for vaccines that may be due. PPSV and Tdap uptake rates were chosen for this quality improvement project to address low baseline coverage rates among adults. The objective of this project was to increase adult Tdap and 23-valent PPSV uptake rates using a reminder checklist at the point of care. A secondary objective was to assess providers’ vaccination practices during various types of visits, appraise their perceived vaccination practices and barriers to vaccinating adults, and to determine providers’ perceived effectiveness of the reminder checklist.

Methods

This quality improvement project was implemented in a large family practice that is home to a family medicine residency program. Approximately two-thirds of the patients served are adults, over half of whom are minorities, and nearly half are on Medicaid or underinsured. Providers in the practice included 21 resident physicians, 8 attending physicians, and 1 nurse practitioner who served as the primary investigator. Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained.

Measures included pre- and post-intervention vaccination rates for Tdap and PPSV, the providers’ perceived vaccination practices during various types of visits, the providers’ perceptions of practice-specific barriers to vaccinating adults, and the providers’ perceived usefulness of a vaccine checklist. To evaluate the effect of the reminder tool on immunization rates, we conducted a chart review. A random sample of 30 charts was derived separately for each vaccine, pre- and post-intervention, by selecting every 5th chart via the electronic health record after filtering for vaccine eligibility. Eligibility for the vaccines was based on age, vaccine history, and diagnoses noted in the medical history and problem list.

After the 3-month intervention period, an 18-item survey was distributed to participating providers to assess their vaccination practices, their perception of practice-related barriers to vaccinating, and their perception of the use of the checklist at the point of care. The survey included 5 demographic items, 5 Yes/No questions asking about the providers’ vaccination practices (adapted from [18]), and 8 questions asking about the providers’ perceptions of practice-specific vaccination barriers and the usefulness of the checklist. For these 8 questions providers were asked to choose a response along a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

Results

All providers responded to the vaccination practice-related questions. These questions and the frequency of responses are presented in Table 3. At follow-up visits, such as those for blood pressure checks, 82% of the providers stated they checked the patient’s immunization status and 76% of providers stated they ordered an immunization. In contrast, although 76% of providers indicated they checked the immunization status, only 47% noted they routinely ordered a vaccine at a sick visit. A Fisher’s exact test of independence to examine the relationship between providers’ years of experience and decision to vaccinate at sick visits revealed a result that was not significant (P = 1).

Discussion and Lessons Learned

Introduction of the reminder checklist at the point of care did not improve the administration or uptake of Tdap or PPSV during the intervention period. Limitations to our analysis include the small sample size. Also, this project was conducted in the fall, when influenza vaccines are usually given and providers may be more attuned to checking for vaccine eligibility. Future iterations of the project may be conducted to allow for samples over several months and use a process control chart to retrieve a more representative sample of participants from each vaccine-eligible group in the practice.

Usage of a paper reminder system after implementation of an electronic health record may have affected the results. Providers who are focused on the computer documentation may have overlooked paper reminders unless patients asked about vaccination. Although the checklist was printed on bright green paper as a visual cue, patients’ failure to present the reminder to providers undermined effectiveness of the paper system. In another study that used pre-visit paper reminders to improve physician performance on measures of chronic disease and preventive care, no benefit was found [19]. Developers of future vaccination programs should consider integrating reminder systems into the current system to mitigate this potential obstacle.

Staff and practice-related barriers may have also contributed to the limited success of the reminder checklist. Staff informally cited a paperwork burden as a challenge for patients. Informal feedback indicated that patients did not fully understand the questionnaire and often did not complete the form, even after being requested and instructed to do so. A systematic review of barriers to the use of reminders for immunizations showed that reminders can be perceived as disruptive to workflow and therefore not implemented or maintained [20]. These findings were congruent with behavior demonstrated by the office staff in the practice, whose buy-in to using the intervention waned over the course of the project. The front office staff needed reinforcement to continue the intervention as time passed. Informal interviews with staff suggested that patients who could have been given a checklist at the front desk did not receive it. These possibilities underline limitations in the study. Future projects may include collecting data such as perceptions of the office staff involved with vaccine interventions and proportion of patients who receive and complete the reminder checklist. A regression analysis is recommended to identify barriers that are more likely to decrease the likelihood of vaccination.

Providers’ responses to survey questions yielded insights into surveyed providers’ perceptions re the importance of immunizing adults and the use of the reminder checklist as an intervention. The majority of the providers (n = 16, 94%) acknowledged that the office had a procedure in place for immunization of adults. Review of the protocol and more vaccine education may be needed to increase providers’ knowledge of adult vaccine indications. Responses to survey questions related to vaccination barriers suggested that providers believed there was adequate time to assess for and order vaccines at routine visits. The possibility exists that an additional barrier may be present that was not uncovered by this project. Further investigation is needed to determine practice-barriers to administering vaccinations to adults at all types of visits for health care.

The findings of this review suggest that missed opportunities to vaccinate continue to exist. This project revealed that sick and problem visits may be an area warranting further exploration for opportunities to vaccinate adults. Survey findings that 76% of providers in the practice routinely check the immunization status of adult patients at sick visits and only 47% routinely order an immunization at sick visits point to the need in future vaccination programs to target sick visits as opportunities to increase adult vaccine administration. In other studies, years of experience has not been well correlated with performance of evidence based practice [21]. However, in our study, no relationship was identified between years of practice and decision to vaccinate during a sick visit. Follow-up visits, for which 76% of the surveyed providers reported ordering immunization, are another opportunity for improvement. A survey of pediatricians and family physicians regarding their adolescent patient vaccination practices revealed similar low rates for both checking the immunization status and administering vaccinations at sick and follow-up visits [18]. Based on these findings, a larger scale review is warranted that focuses on sick and follow-up visits to determine the rate of vaccination at these visits, barriers to vaccinating at sick and follow-up visits, and successful interventions to increase vaccination rates during these encounters.

Providers’ perceived vaccination behaviors at sick and follow-up visits may be related to time restrictions resulting from shorter appointments as well as providers’ varying degrees of comfort with offering vaccines during those visits. In addition, misunderstanding of vaccination contraindications has led to missed opportunities to vaccinate women and children [22] and this may apply to adults as well. Providers need to be aware of the true contraindications to vaccines. Mild acute illness is neither a contraindication nor a precaution to administering a vaccine [23]. Future projects may also focus on educating providers (at all levels of experience) regarding the safety and efficacy of administering vaccinations during illness-related visits and actual contraindications.

Also, to address time constraints during sick and follow-up visits, making the entire practice responsible for vaccination assessment and administration should be more widely employed to reduce the burden on the primary care provider. A successful model for increasing uptake involves using teamwork [16] among clinical and non-clinical staff. Successful implementation of an adult vaccination program may be improved by using a similar approach that will increase staff buy-in and accountability.

Conclusion

While care providers in this project generally perceived the reminder checklist at the point of care as helpful as a provider reminder, a patient engager, and a tool to determine vaccine eligibility, it was not effective in increasing Tdap or PPSV coverage among adult patients in the practice. Practice and workflow-related barriers to success of the intervention imply the need for careful consideration of the type of reminder system put in place in various practices. Hesitation to vaccinate during illness-related and follow-up visits denotes the need for further education of providers regarding true contraindications to particular vaccinations and further investigation of ways to make immunizing a collective responsibility shared by the patient, the office staff, and the primary and ancillary providers.

Corresponding author: Dyllan Walter, DNP, CRNP, North Hills Health Center, 212 Girard Ave., Glenside, PA 19038, dyllan79@yahoo.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Abington Health, Abington, PA (Ms. Walter) and Duquesne University School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA (Dr. Guimond).

Abstract

- Background: National coverage rates for many recommended adult vaccines are low. Tetanus toxoid, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) and pneumococcal vaccination rates among adults are 20% and 16%, respectively. To address these low rates in our practice, we identified missed opportunities for vaccination as a target for improvement.

- Objective: To examine the effectiveness of a vaccine reminder checklist at the point of care and assess providers’ perceived vaccine practices.

- Methods: The quick sample method was used to assess pre- and post-intervention pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPSV) and Tdap vaccination rates among the target population (adults 18-64 for Tdap; high-risk adults 18-64 for PPSV). A post-intervention survey was used to assess providers’ adult vaccination practices and their opinion of the reminder tool.

- Results: The Tdap vaccination rate did not change and was constant at 47%. PPSV vaccination rates decreased from 50% to 40%. Among the providers, 47% reported ordering immunizations at sick visits, as compared to 76% at follow-up visits. The providers reported the reminder checklist was useful for determining a patient’s eligibility for a vaccine.

- Conclusion: No improvement in vaccination rates was detected for this project, which may be partially explained by challenges originating at patient check-in. In the future, buy-in from all staff in our practice setting will be sought. Results indicate that providers may hesitate to administer immunizations at sick visits and may need education on vaccination contraindications.

Vaccines are an important public health tool that offer safe and effective protection against certain diseases and reduce the health care burden [1,2]. Missed opportunities to vaccinate, defined as any primary care encounter in which a patient eligible for a vaccine is not administered a vaccine, lead to suboptimal immunization coverage among adults. Providers have been urged to review patients’ vaccine status at every patient encounter [3]. Rates of vaccinations recommended in 2012 by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) remain low [4], particularly coverage rates for tetanus toxoid, diphtheria, and acelluar pertussis vaccine (Tdap) vaccine among adults, and for pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV) among high-risk adults [2]. Nationally, uptake rates are approximately 16% for Tdap and 20% for pneumococcal vaccines among eligible adults aged 18 to 64 years [5]. These low uptake rates suggest that programs are needed to reduce missed opportunities to vaccinate and improve vaccination rates among adults.

There is a strong case for improving Tdap and pneumococcal vaccination uptake among high-risk adults. Since the 1970s, the incidence of pertussis in the United States has increased substantially, with numbers of reported cases reaching as high as 48,277 and 28,639 in 2012 and 2013, respectively [2]. Some states experienced epidemic levels of pertussis [2,6]. Pertussis is often fatal among infected infants, and infection in adolescents and adults may cost upwards of $800 per case [7,8]. In 2005, high-risk adults for whom the PPSV was indicated accounted for half of the 40,000 pneumococcal infections in the United States [9]. PPSV boasts a 50% to 80% effectiveness rate in preventing pneumococcal disease among high-risk patients [9]. In a CDC cost-effectiveness analysis, immunization of immunocompromised patients with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-13) at the time of diagnosis followed with PPSV vaccinations starting 1 year later led to savings of $7.6 million, added 1360 quality-adjusted life years, and prevented 57 cases of invasive pneumococcal disease [10].

Recognizing and overcoming practice-specific barriers to vaccinating adults are needed to improve uptake. A lack of patient- and provider-focused reminders may lead to missed opportunities to vaccinate [11,12]. Provider and patient-focused reminder tools can be effective in increasing vaccine uptake [1,13,14], but interventions that combine reminder tools with patient outreach may be more effective [15]. Furthermore, involving an interdisciplinary team to coordinate the administration of vaccines among adults may improve vaccine uptake rates [16]. These studies suggested the need to determine a standard, effective reminder tool and incorporate multilevel interventions to increase uptake of adult vaccines.

An informal electronic query at a large, suburban family practice revealed approximately 30% Tdap and PPSV coverage rates among eligible adults served by the practice, suggesting that providers fail to assess patients’ vaccine status at every opportunity. Electronic medical records provide no alerts for vaccines that may be due. PPSV and Tdap uptake rates were chosen for this quality improvement project to address low baseline coverage rates among adults. The objective of this project was to increase adult Tdap and 23-valent PPSV uptake rates using a reminder checklist at the point of care. A secondary objective was to assess providers’ vaccination practices during various types of visits, appraise their perceived vaccination practices and barriers to vaccinating adults, and to determine providers’ perceived effectiveness of the reminder checklist.

Methods

This quality improvement project was implemented in a large family practice that is home to a family medicine residency program. Approximately two-thirds of the patients served are adults, over half of whom are minorities, and nearly half are on Medicaid or underinsured. Providers in the practice included 21 resident physicians, 8 attending physicians, and 1 nurse practitioner who served as the primary investigator. Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained.

Measures included pre- and post-intervention vaccination rates for Tdap and PPSV, the providers’ perceived vaccination practices during various types of visits, the providers’ perceptions of practice-specific barriers to vaccinating adults, and the providers’ perceived usefulness of a vaccine checklist. To evaluate the effect of the reminder tool on immunization rates, we conducted a chart review. A random sample of 30 charts was derived separately for each vaccine, pre- and post-intervention, by selecting every 5th chart via the electronic health record after filtering for vaccine eligibility. Eligibility for the vaccines was based on age, vaccine history, and diagnoses noted in the medical history and problem list.

After the 3-month intervention period, an 18-item survey was distributed to participating providers to assess their vaccination practices, their perception of practice-related barriers to vaccinating, and their perception of the use of the checklist at the point of care. The survey included 5 demographic items, 5 Yes/No questions asking about the providers’ vaccination practices (adapted from [18]), and 8 questions asking about the providers’ perceptions of practice-specific vaccination barriers and the usefulness of the checklist. For these 8 questions providers were asked to choose a response along a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

Results

All providers responded to the vaccination practice-related questions. These questions and the frequency of responses are presented in Table 3. At follow-up visits, such as those for blood pressure checks, 82% of the providers stated they checked the patient’s immunization status and 76% of providers stated they ordered an immunization. In contrast, although 76% of providers indicated they checked the immunization status, only 47% noted they routinely ordered a vaccine at a sick visit. A Fisher’s exact test of independence to examine the relationship between providers’ years of experience and decision to vaccinate at sick visits revealed a result that was not significant (P = 1).

Discussion and Lessons Learned

Introduction of the reminder checklist at the point of care did not improve the administration or uptake of Tdap or PPSV during the intervention period. Limitations to our analysis include the small sample size. Also, this project was conducted in the fall, when influenza vaccines are usually given and providers may be more attuned to checking for vaccine eligibility. Future iterations of the project may be conducted to allow for samples over several months and use a process control chart to retrieve a more representative sample of participants from each vaccine-eligible group in the practice.

Usage of a paper reminder system after implementation of an electronic health record may have affected the results. Providers who are focused on the computer documentation may have overlooked paper reminders unless patients asked about vaccination. Although the checklist was printed on bright green paper as a visual cue, patients’ failure to present the reminder to providers undermined effectiveness of the paper system. In another study that used pre-visit paper reminders to improve physician performance on measures of chronic disease and preventive care, no benefit was found [19]. Developers of future vaccination programs should consider integrating reminder systems into the current system to mitigate this potential obstacle.

Staff and practice-related barriers may have also contributed to the limited success of the reminder checklist. Staff informally cited a paperwork burden as a challenge for patients. Informal feedback indicated that patients did not fully understand the questionnaire and often did not complete the form, even after being requested and instructed to do so. A systematic review of barriers to the use of reminders for immunizations showed that reminders can be perceived as disruptive to workflow and therefore not implemented or maintained [20]. These findings were congruent with behavior demonstrated by the office staff in the practice, whose buy-in to using the intervention waned over the course of the project. The front office staff needed reinforcement to continue the intervention as time passed. Informal interviews with staff suggested that patients who could have been given a checklist at the front desk did not receive it. These possibilities underline limitations in the study. Future projects may include collecting data such as perceptions of the office staff involved with vaccine interventions and proportion of patients who receive and complete the reminder checklist. A regression analysis is recommended to identify barriers that are more likely to decrease the likelihood of vaccination.

Providers’ responses to survey questions yielded insights into surveyed providers’ perceptions re the importance of immunizing adults and the use of the reminder checklist as an intervention. The majority of the providers (n = 16, 94%) acknowledged that the office had a procedure in place for immunization of adults. Review of the protocol and more vaccine education may be needed to increase providers’ knowledge of adult vaccine indications. Responses to survey questions related to vaccination barriers suggested that providers believed there was adequate time to assess for and order vaccines at routine visits. The possibility exists that an additional barrier may be present that was not uncovered by this project. Further investigation is needed to determine practice-barriers to administering vaccinations to adults at all types of visits for health care.

The findings of this review suggest that missed opportunities to vaccinate continue to exist. This project revealed that sick and problem visits may be an area warranting further exploration for opportunities to vaccinate adults. Survey findings that 76% of providers in the practice routinely check the immunization status of adult patients at sick visits and only 47% routinely order an immunization at sick visits point to the need in future vaccination programs to target sick visits as opportunities to increase adult vaccine administration. In other studies, years of experience has not been well correlated with performance of evidence based practice [21]. However, in our study, no relationship was identified between years of practice and decision to vaccinate during a sick visit. Follow-up visits, for which 76% of the surveyed providers reported ordering immunization, are another opportunity for improvement. A survey of pediatricians and family physicians regarding their adolescent patient vaccination practices revealed similar low rates for both checking the immunization status and administering vaccinations at sick and follow-up visits [18]. Based on these findings, a larger scale review is warranted that focuses on sick and follow-up visits to determine the rate of vaccination at these visits, barriers to vaccinating at sick and follow-up visits, and successful interventions to increase vaccination rates during these encounters.

Providers’ perceived vaccination behaviors at sick and follow-up visits may be related to time restrictions resulting from shorter appointments as well as providers’ varying degrees of comfort with offering vaccines during those visits. In addition, misunderstanding of vaccination contraindications has led to missed opportunities to vaccinate women and children [22] and this may apply to adults as well. Providers need to be aware of the true contraindications to vaccines. Mild acute illness is neither a contraindication nor a precaution to administering a vaccine [23]. Future projects may also focus on educating providers (at all levels of experience) regarding the safety and efficacy of administering vaccinations during illness-related visits and actual contraindications.

Also, to address time constraints during sick and follow-up visits, making the entire practice responsible for vaccination assessment and administration should be more widely employed to reduce the burden on the primary care provider. A successful model for increasing uptake involves using teamwork [16] among clinical and non-clinical staff. Successful implementation of an adult vaccination program may be improved by using a similar approach that will increase staff buy-in and accountability.

Conclusion

While care providers in this project generally perceived the reminder checklist at the point of care as helpful as a provider reminder, a patient engager, and a tool to determine vaccine eligibility, it was not effective in increasing Tdap or PPSV coverage among adult patients in the practice. Practice and workflow-related barriers to success of the intervention imply the need for careful consideration of the type of reminder system put in place in various practices. Hesitation to vaccinate during illness-related and follow-up visits denotes the need for further education of providers regarding true contraindications to particular vaccinations and further investigation of ways to make immunizing a collective responsibility shared by the patient, the office staff, and the primary and ancillary providers.

Corresponding author: Dyllan Walter, DNP, CRNP, North Hills Health Center, 212 Girard Ave., Glenside, PA 19038, dyllan79@yahoo.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Stone EG, Morton SC, Hulscher ME, et al. Interventions that increase use of adult immunization and cancer screening services: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:641–51.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis outbreak trends. 2015. Available at www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks/trends.html.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Standards for adult immunization practice. 2014. Available at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/patient-ed/adults/for-practice/standards.html.

4. Bridges CB. Adult immunization in the United States: 2012 update. Available at www.womeningovernment.org/files/file/CarolynBridges.pdf

5. Williams WW, Lu P-J, O’Halloran A, et al. Noninfluenza vaccination coverage among adults—United States, 2012. MMWR 2014;63:95–102.

6. Winter K, Glaser C, Watt J, Harriman K; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pertussis epidemic--California, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:1129–32.

7. Grizas AP, Camenga D, Vázquez M. Cocooning: A concept to protect young children from infectious diseases. Curr Opin Pediatr 2012;24:92–7.

8. Gidengil CA, Sandora TJ, Lee GM. Tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccination of adults in the USA. Expert Rev Vaccines 2008;7:621–34.

9. Wolfe RM. Update on adult immunizations. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:496–510.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2012;61:816–19.

11. Head KJ, Vanderpool RC, Mills LA. Health care providers’ perspectives on low HPV vaccine uptake and adherence in Appalachian Kentucky. Public Health Nurs 2013;30:351–60.

12. Perkins RB, Clark JA. What affects human papilloma virus vaccination rates? A qualitative analysis of providers’ perceptions. Womens Health Issues 2012;22:e379–86.

13. Thomas RE, Russell ML, Lorenzetti DL. Systematic review of interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates of those 60 years and older. Vaccine 2010;28:1684–70.

14. Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:97–140.

15. Humiston SG, Bennett NM, Long C, et al. Increasing inner-city adult influenza vaccination rates: A randomized controlled trial. Public Health Rep 2011;126:39–47.

16. Gannon M, Qaseem A, Snooks Q, Snow V. Improving adult immunization practices using a team approach in the primary setting. Am J Public Health 2012;102:e46–e52.

17. Immunization Action Coalition. Do I need any vaccinations today? 2014. Available at www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4036.pdf.

18. Schaffer SJ, Humiston SG, Shone LP, et al. Adolescent immunization practices: A national survey of US physicians. Arch Pediat Adol Med 2001;155:566–71.

19. Baker DW, Persell SD, Kho AN, et al. The marginal value of pre-visit paper reminders when added to a multifaceted electronic health record based quality improvement system. J Am Med Informat Assoc 2011;18:805–11.

20. Pereira JA, Quach S, Heidebrecht CL, et al. Barriers to the use of reminder/recall interventions for immunizations: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012;12:145.

21. Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: The relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:260–73.

22. Hutchins SS, Jansen HAFM, Robertson SE, et al. Missed opportunities for immunization: review of studies from developing and industrialized countries. Bull World Health Org 1993;71:549–60.

23. Immunization Action Coalition. Precautions and contraindications. 2015. Available at www.immunize.org/askexperts/precautions-contraindications.asp.

1. Stone EG, Morton SC, Hulscher ME, et al. Interventions that increase use of adult immunization and cancer screening services: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:641–51.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis outbreak trends. 2015. Available at www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks/trends.html.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Standards for adult immunization practice. 2014. Available at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/patient-ed/adults/for-practice/standards.html.

4. Bridges CB. Adult immunization in the United States: 2012 update. Available at www.womeningovernment.org/files/file/CarolynBridges.pdf

5. Williams WW, Lu P-J, O’Halloran A, et al. Noninfluenza vaccination coverage among adults—United States, 2012. MMWR 2014;63:95–102.

6. Winter K, Glaser C, Watt J, Harriman K; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pertussis epidemic--California, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:1129–32.

7. Grizas AP, Camenga D, Vázquez M. Cocooning: A concept to protect young children from infectious diseases. Curr Opin Pediatr 2012;24:92–7.

8. Gidengil CA, Sandora TJ, Lee GM. Tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccination of adults in the USA. Expert Rev Vaccines 2008;7:621–34.

9. Wolfe RM. Update on adult immunizations. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:496–510.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2012;61:816–19.

11. Head KJ, Vanderpool RC, Mills LA. Health care providers’ perspectives on low HPV vaccine uptake and adherence in Appalachian Kentucky. Public Health Nurs 2013;30:351–60.

12. Perkins RB, Clark JA. What affects human papilloma virus vaccination rates? A qualitative analysis of providers’ perceptions. Womens Health Issues 2012;22:e379–86.

13. Thomas RE, Russell ML, Lorenzetti DL. Systematic review of interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates of those 60 years and older. Vaccine 2010;28:1684–70.

14. Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:97–140.

15. Humiston SG, Bennett NM, Long C, et al. Increasing inner-city adult influenza vaccination rates: A randomized controlled trial. Public Health Rep 2011;126:39–47.

16. Gannon M, Qaseem A, Snooks Q, Snow V. Improving adult immunization practices using a team approach in the primary setting. Am J Public Health 2012;102:e46–e52.

17. Immunization Action Coalition. Do I need any vaccinations today? 2014. Available at www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4036.pdf.

18. Schaffer SJ, Humiston SG, Shone LP, et al. Adolescent immunization practices: A national survey of US physicians. Arch Pediat Adol Med 2001;155:566–71.

19. Baker DW, Persell SD, Kho AN, et al. The marginal value of pre-visit paper reminders when added to a multifaceted electronic health record based quality improvement system. J Am Med Informat Assoc 2011;18:805–11.

20. Pereira JA, Quach S, Heidebrecht CL, et al. Barriers to the use of reminder/recall interventions for immunizations: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012;12:145.

21. Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: The relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:260–73.

22. Hutchins SS, Jansen HAFM, Robertson SE, et al. Missed opportunities for immunization: review of studies from developing and industrialized countries. Bull World Health Org 1993;71:549–60.

23. Immunization Action Coalition. Precautions and contraindications. 2015. Available at www.immunize.org/askexperts/precautions-contraindications.asp.