User login

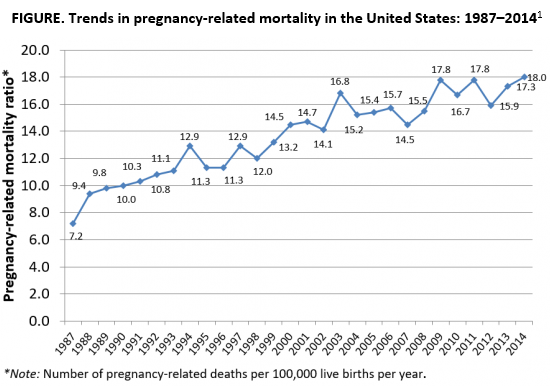

As the rest of the industrialized world has seen a decline in maternal mortality, the United States has seen a substantial rise over the last 30 years (FIGURE).1 It is estimated that more than 60% of these pregnancy-related deaths are preventable. Additionally, substantial disparities exist, with African-American women 3 to 4 times more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications than white women.1

A good first step

The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act was passed by the 115th Congress and signed into law December 2018 in an effort to support and expand maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) on a state level while allowing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to further study disparities within maternal mortality. Although these efforts are a good first step to help reduce maternal mortality, more needs to be done to quell this growing epidemic.

We must now improve care access

One strategy to aid in decreasing maternal morbidity and mortality is to improve affordable access to medical care. Medicaid is the largest single payer of maternity care in the United States, covering 42.6% of births. Currently, in many states, Medicaid coverage only lasts until a woman is 60 days postpartum.2 Although 31 states, including the District of Columbia, have adopted Medicaid expansion programs to allow women to extend coverage beyond those 60 days, offering these programs is not a federal law. In the 19 remaining states with no extension options, the vast majority of women will lose their Medicaid coverage just after they are 2 months postpartum and will have no alternative health insurance coverage.2

Why does this coverage cutoff matter? Pregnancy-related deaths are defined as up to 12 months postpartum. A report reviewing 9 MMRCs found that 38% of pregnancy-related deaths occurred while a woman was pregnant, 45% of deaths occurred within 42 days of delivery, and 18% from 43 days to 1 year after delivery.3 Additionally, nearly half of women with Medicaid do not come to their 6-week postpartum visit (for a variety of reasons), missing a critical opportunity to address health concerns.2 Of the deaths that occurred in this later postpartum period, leading causes were cardiomyopathy (32%), mental health conditions (16%), and embolism (11%).3 Prevention and management of these conditions require regular follow-up with an ObGyn, as well as potentially from subspecialists in cardiology, psychiatry, hematology, and other subspecialties. Women not having access to affordable health care during the critical postpartum period greatly increases their risk of death or severe morbidity.

An important next step beyond the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act is to extend Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum for all women everywhere. MMRCs have concluded that extending coverage would ensure that “medical and behavioral health conditions [could be] managed and treated before becoming progressively severe.”3 This would presumably help decrease the risk of pregnancy-related death and address worsening morbidity. Additionally, the postpartum period is a well-established time of increased stress and can be an overwhelming and emotional time for many new mothers, especially for those with limited resources for childcare, transportation, stable housing, etc.6 Providing and ensuring ongoing medical care would substantially improve the lives and health of women and the health of their families.

We, as a country, need to make changes

Every step of the way, a woman faces challenges to safely and affordably access health care. Providing access to insurance coverage for 12 months postpartum can help to decrease our country’s rising maternal mortality and morbidity rates.

Take action

Congresswoman Robin Kelly (D-IL) and Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) have introduced the MOMMA Act (H.R. 1897/S. 916) to help address the rising maternal mortality rate.

This Act would:

- Expand Medicaid coverage to 1 year postpartum.

- Work with the CDC to uniformly collect data to accurately assess maternal mortality and morbidity.

- Ensure the sharing of best practices of care across hospital systems.

- Focus on culturally-competent care to address implicit bias among health care workers.

- Support and expand the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM)—a data-driven initiative to implement safety protocols in hospitals across the country.

To call or contact your representative to co-sponsor this bill, click here. To review if your Congressperson is a co-sponsor, click here. To review if your Senator is a co-sponsor, click here.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, Trends in Pregnancy-Related Deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Stuebe A, Moore JE, Mittal P, et al. Extending medicaid coverage for postpartum moms. May 6, 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190501.254675/full/. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. Report from nine maternal mortality review committees. 2018. Color/Word_R17_G85_B204http://reviewtoaction.org/Report_from_Nine_MMRCs. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, et al. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-55.

- Vestal C. For addicted women, the year after childbirth is the deadliest. August 14, 2018. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2018/08/14/for-addicted-women-the-year-after-childbirth-is-the-deadliest. Accessed May 29, 2019.

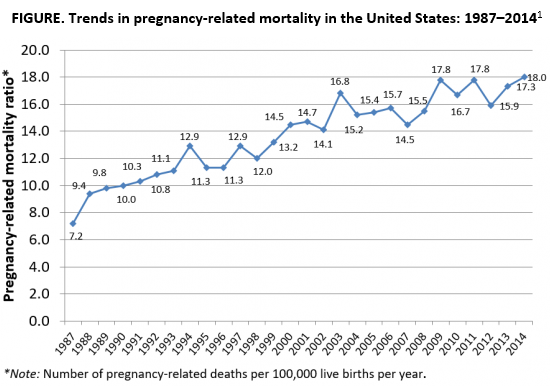

As the rest of the industrialized world has seen a decline in maternal mortality, the United States has seen a substantial rise over the last 30 years (FIGURE).1 It is estimated that more than 60% of these pregnancy-related deaths are preventable. Additionally, substantial disparities exist, with African-American women 3 to 4 times more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications than white women.1

A good first step

The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act was passed by the 115th Congress and signed into law December 2018 in an effort to support and expand maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) on a state level while allowing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to further study disparities within maternal mortality. Although these efforts are a good first step to help reduce maternal mortality, more needs to be done to quell this growing epidemic.

We must now improve care access

One strategy to aid in decreasing maternal morbidity and mortality is to improve affordable access to medical care. Medicaid is the largest single payer of maternity care in the United States, covering 42.6% of births. Currently, in many states, Medicaid coverage only lasts until a woman is 60 days postpartum.2 Although 31 states, including the District of Columbia, have adopted Medicaid expansion programs to allow women to extend coverage beyond those 60 days, offering these programs is not a federal law. In the 19 remaining states with no extension options, the vast majority of women will lose their Medicaid coverage just after they are 2 months postpartum and will have no alternative health insurance coverage.2

Why does this coverage cutoff matter? Pregnancy-related deaths are defined as up to 12 months postpartum. A report reviewing 9 MMRCs found that 38% of pregnancy-related deaths occurred while a woman was pregnant, 45% of deaths occurred within 42 days of delivery, and 18% from 43 days to 1 year after delivery.3 Additionally, nearly half of women with Medicaid do not come to their 6-week postpartum visit (for a variety of reasons), missing a critical opportunity to address health concerns.2 Of the deaths that occurred in this later postpartum period, leading causes were cardiomyopathy (32%), mental health conditions (16%), and embolism (11%).3 Prevention and management of these conditions require regular follow-up with an ObGyn, as well as potentially from subspecialists in cardiology, psychiatry, hematology, and other subspecialties. Women not having access to affordable health care during the critical postpartum period greatly increases their risk of death or severe morbidity.

An important next step beyond the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act is to extend Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum for all women everywhere. MMRCs have concluded that extending coverage would ensure that “medical and behavioral health conditions [could be] managed and treated before becoming progressively severe.”3 This would presumably help decrease the risk of pregnancy-related death and address worsening morbidity. Additionally, the postpartum period is a well-established time of increased stress and can be an overwhelming and emotional time for many new mothers, especially for those with limited resources for childcare, transportation, stable housing, etc.6 Providing and ensuring ongoing medical care would substantially improve the lives and health of women and the health of their families.

We, as a country, need to make changes

Every step of the way, a woman faces challenges to safely and affordably access health care. Providing access to insurance coverage for 12 months postpartum can help to decrease our country’s rising maternal mortality and morbidity rates.

Take action

Congresswoman Robin Kelly (D-IL) and Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) have introduced the MOMMA Act (H.R. 1897/S. 916) to help address the rising maternal mortality rate.

This Act would:

- Expand Medicaid coverage to 1 year postpartum.

- Work with the CDC to uniformly collect data to accurately assess maternal mortality and morbidity.

- Ensure the sharing of best practices of care across hospital systems.

- Focus on culturally-competent care to address implicit bias among health care workers.

- Support and expand the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM)—a data-driven initiative to implement safety protocols in hospitals across the country.

To call or contact your representative to co-sponsor this bill, click here. To review if your Congressperson is a co-sponsor, click here. To review if your Senator is a co-sponsor, click here.

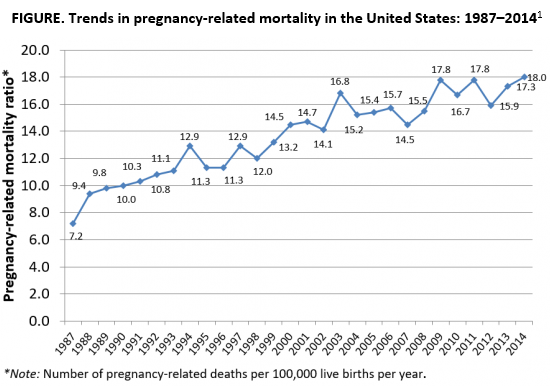

As the rest of the industrialized world has seen a decline in maternal mortality, the United States has seen a substantial rise over the last 30 years (FIGURE).1 It is estimated that more than 60% of these pregnancy-related deaths are preventable. Additionally, substantial disparities exist, with African-American women 3 to 4 times more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications than white women.1

A good first step

The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act was passed by the 115th Congress and signed into law December 2018 in an effort to support and expand maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) on a state level while allowing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to further study disparities within maternal mortality. Although these efforts are a good first step to help reduce maternal mortality, more needs to be done to quell this growing epidemic.

We must now improve care access

One strategy to aid in decreasing maternal morbidity and mortality is to improve affordable access to medical care. Medicaid is the largest single payer of maternity care in the United States, covering 42.6% of births. Currently, in many states, Medicaid coverage only lasts until a woman is 60 days postpartum.2 Although 31 states, including the District of Columbia, have adopted Medicaid expansion programs to allow women to extend coverage beyond those 60 days, offering these programs is not a federal law. In the 19 remaining states with no extension options, the vast majority of women will lose their Medicaid coverage just after they are 2 months postpartum and will have no alternative health insurance coverage.2

Why does this coverage cutoff matter? Pregnancy-related deaths are defined as up to 12 months postpartum. A report reviewing 9 MMRCs found that 38% of pregnancy-related deaths occurred while a woman was pregnant, 45% of deaths occurred within 42 days of delivery, and 18% from 43 days to 1 year after delivery.3 Additionally, nearly half of women with Medicaid do not come to their 6-week postpartum visit (for a variety of reasons), missing a critical opportunity to address health concerns.2 Of the deaths that occurred in this later postpartum period, leading causes were cardiomyopathy (32%), mental health conditions (16%), and embolism (11%).3 Prevention and management of these conditions require regular follow-up with an ObGyn, as well as potentially from subspecialists in cardiology, psychiatry, hematology, and other subspecialties. Women not having access to affordable health care during the critical postpartum period greatly increases their risk of death or severe morbidity.

An important next step beyond the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act is to extend Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum for all women everywhere. MMRCs have concluded that extending coverage would ensure that “medical and behavioral health conditions [could be] managed and treated before becoming progressively severe.”3 This would presumably help decrease the risk of pregnancy-related death and address worsening morbidity. Additionally, the postpartum period is a well-established time of increased stress and can be an overwhelming and emotional time for many new mothers, especially for those with limited resources for childcare, transportation, stable housing, etc.6 Providing and ensuring ongoing medical care would substantially improve the lives and health of women and the health of their families.

We, as a country, need to make changes

Every step of the way, a woman faces challenges to safely and affordably access health care. Providing access to insurance coverage for 12 months postpartum can help to decrease our country’s rising maternal mortality and morbidity rates.

Take action

Congresswoman Robin Kelly (D-IL) and Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) have introduced the MOMMA Act (H.R. 1897/S. 916) to help address the rising maternal mortality rate.

This Act would:

- Expand Medicaid coverage to 1 year postpartum.

- Work with the CDC to uniformly collect data to accurately assess maternal mortality and morbidity.

- Ensure the sharing of best practices of care across hospital systems.

- Focus on culturally-competent care to address implicit bias among health care workers.

- Support and expand the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM)—a data-driven initiative to implement safety protocols in hospitals across the country.

To call or contact your representative to co-sponsor this bill, click here. To review if your Congressperson is a co-sponsor, click here. To review if your Senator is a co-sponsor, click here.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, Trends in Pregnancy-Related Deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Stuebe A, Moore JE, Mittal P, et al. Extending medicaid coverage for postpartum moms. May 6, 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190501.254675/full/. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. Report from nine maternal mortality review committees. 2018. Color/Word_R17_G85_B204http://reviewtoaction.org/Report_from_Nine_MMRCs. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, et al. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-55.

- Vestal C. For addicted women, the year after childbirth is the deadliest. August 14, 2018. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2018/08/14/for-addicted-women-the-year-after-childbirth-is-the-deadliest. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, Trends in Pregnancy-Related Deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Stuebe A, Moore JE, Mittal P, et al. Extending medicaid coverage for postpartum moms. May 6, 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190501.254675/full/. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. Report from nine maternal mortality review committees. 2018. Color/Word_R17_G85_B204http://reviewtoaction.org/Report_from_Nine_MMRCs. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, et al. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-55.

- Vestal C. For addicted women, the year after childbirth is the deadliest. August 14, 2018. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2018/08/14/for-addicted-women-the-year-after-childbirth-is-the-deadliest. Accessed May 29, 2019.