User login

The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are among the leading registries for cancer surveillance, collecting cancer epidemiology data for the majority of the U.S. population.1 This national coverage aids researchers and policymakers in conducting epidemiologic studies and allocating health resources.1,2

U.S. federal law mandates the reporting of cancer.3,4 State laws require cancer reporting as well, but requirements vary slightly from state to state.5 However, all cancers with an ICD-O (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology) code of 2 or 3 are reportable. For Washington state, cancer must be reported unless it is basal or squamous cell carcinoma of nonmucoepidermoid skin or in situ cancer of the uterine cervix.5 In general, each facility that diagnoses or treats a melanoma is required to report it. Data are consolidated at the central registry level if necessary.

Cancer reporting often fails to meet states’ requirements.6-8 Since the inception of SEER and NPCR, many studies have assessed the accuracy of the cancer data reported to these registries and have found these data to be inaccurate or incomplete.6-8 Melanoma reporting, in particular,

seems to be prone to error. Studies have demonstrated melanoma underreporting ranging from 10% to 70%, with an increase in underreporting over time.9-11 Significant delays of up to 10 years have been found between initial diagnosis and reporting for melanomas.12 In general, these studies have focused on smaller facilities, such as private laboratories, which lack in-house reporting systems.

Cancer reporting is especially important in the VHA, the largest U.S. health care system. Health data on about 9 million enrolled veterans have been invaluable for understanding cancer epidemiology. Underreporting and misreporting of cancer cases in private medical offices and smaller treatment facilities may be attributable to lack of funding, personnel, administrative support, or knowledge of reporting requirements. In contrast, the VHA requires cancer reporting and provides funding, personnel, and administrative support.13

The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) traditionally has employed registrars to perform the majority of basic cancer registry tasks, including abstracting, case finding, and lifelong follow-up of the cancer patients listed in the registry. The registrars use OncoTraX software, which finds possible cancer cases from pathology, radiology, and patient treatment files, to accession cases. Unique cancer cases are reported to the VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR), the Washington state registry, and the NCDB, which then transfer the data to the national registries. Accordingly, cases not accessioned would not be reported to the VA, state, and national registries.

The authors conducted a quality improvement project to ascertain whether primary cutaneous melanomas biopsied at VAPSHCS were underreported.

Materials

The VAPSHCS serves about 100,000 veterans and consists of 2 major treatment facilities, 2 community-based outpatient clinics, 1 outreach clinic, and 4 contract community-based outpatient clinics. Pathology cases for the entire VAPSHCS are accessioned in a central laboratory in Seattle.

Data Sources and Chart Abstraction

Data sources included the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), the VAPSHCS cancer registry, the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), VistA (Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture), VistA Web, and VistA Imaging.

Study Population

The study population consisted of veterans who had been diagnosed with primary cutaneous melanoma and had the diagnosis confirmed by biopsy performed at VAPSHCS between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2012.

Statistical Analysis

Odds ratios were calculated using the MedCalc Odds Ratio Calculator.14

Methods

The authors identified SNOMED (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine) codes that included the character string melanoma (Table 1). Using these codes, they queried VistA to identify melanoma cases diagnosed in the VAPSHCS Pathology and Laboratory Service during the period 2006 to 2012. To confirm the completeness of the local report, the authors performed the same search using the CDW. The SNOMED code case-finding was supplemented with cases ascertained using ICD-9 codes and problem list diagnoses.

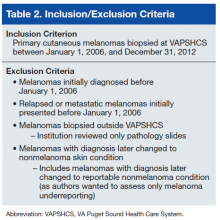

A case must be reported to the local cancer registry if diagnosis or treatment takes place at the facility. All cases ascertained with the authors’ search criteria are, by definition, reportable to the local cancer registry. The authors then applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine

which cases were primary cutaneous melanomas and therefore candidates for this investigation (Table 2).

Having ascertained the primary cutaneous melanomas, the authors abstracted the pathology TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) staging (Breslow depth, mitotic index, presence of ulceration) and diagnosis dates from CPRS pathology reports. They then determined whether each case had been reported to the VACCR (OncoTraX was used to query for the accession status of each melanoma). If the melanoma was not accessioned, the authors tried to determine why.

Results

The authors discovered 193 primary cutaneous melanomas diagnosed by biopsy performed at VAPSHCS. Of these 193 melanomas, 71 (36.8%) had not been reported.

After the pathologist has completed a report, SNOMED codes are assigned by the pathology laboratory. Case finding with OncoTraX depends on SNOMED codes and other parameters (imaging, treatment, oncology consultation). OncoTraX is designed for case finding using World Health Organization (WHO) standardized 8000/X-9000/X series SNOMED codes. To understand the relationship between reporting and SNOMED codes, the authors ascertained the codes for all melanomas in the present study.

Table 3 lists the SNOMED codes assigned to melanomas biopsied at VAPSHCS and the percentage reported for each. Of the 106 melanomas that had been assigned WHO standardized codes, 101 (95.2%) had been reported. In contrast, only 21 (24.1%) of the 87 melanomas that had been assigned non-WHO standardized codes had been reported. In this study, non-WHO standardized codes are locally generated codes; they began with facility station number 663.

Use of locally generated codes may have contributed to nonreporting. Of the 71 melanomas not reported, 66 had a SNOMED code beginning with 663, and the other 5 had a WHO standardized SNOMED code. Odds of being nonreported were much higher for the melanomas with 663 codes than for the melanomas with WHO standardized codes (odds ratio [OR], 63.5; confidence interval [CI], 22.8-176.7; P ≤ .0001).

There was also a difference in coding between invasive and in situ melanomas. Of the 87 melanomas with a 663 code, 68 were in situ. Of the 106 melanomas with a national-level code, 11 were in situ. The odds of being assigned a local code were much higher for the in situ melanomas than they were for the invasive melanomas (OR, 30.9; CI, 13.8-69.1; P ≤ .0001).

Since 2000, the SNOMED code for melanoma in situ has been 87202, but no melanomas in situ were assigned this code. The 87202 code was not available in VistA for pathology laboratories to assign to melanomas at the time this study was conducted. Instead, most melanomas in situ were assigned a locally generated code. However, OncoTraX cannot recognize local codes, so melanomas assigned a local code might not have been accessionable.

The remaining 5 unreported melanomas were assigned WHO standardized codes. Secondary analysis revealed clerical errors, 4 made by the pathology laboratory and 1 by the registrar.

Discussion

Data from central cancer registries are used in a variety of fields, from research studies to health policymaking. They are used to “monitor cancer trends over time, show cancer patterns in various populations, identify high-risk groups, guide planning and evaluation of cancer control programs, help set priorities for allocating health resources, and advance clinical, epidemiologic, and health services research.”1

Melanoma underreporting has been demonstrated in previous studies, with the percentage of underreported cases varying from 10.4%11 to 70%.9 A longitudinal study of melanomas in Washington state found that underreporting of cutaneous melanomas increased from 2% to 21% over a 10-year period.10 This trend prompted examination of this study’s data for a similar temporal trend, and none was found.

A 2008 study found that more melanoma cases were being diagnosed or treated at outpatient facilities.9 Such facilities are prone to problems in reporting because they lack in-house reporting systems and knowledge of melanoma reporting requirements.9 A 2011 study of

practicing dermatologists found that many failed to report melanomas to a registry, and more than half were unaware of the requirement.12 Accordingly, underreporting is likely to continue. Results of the present study showed that melanoma underreporting was a major issue at VAPSHCS and that it could occur even in facilities that used in-house reporting systems and were aware of reporting requirements. The primary cause of underreporting was generation and use of local SNOMED codes that were unrecognizable by OncoTraX. A secondary cause was clerical error.

Discovery of unreported cases prompted facility review of procedures for reporting melanomas and expansion of current methods for melanoma discovery. All unreported cases have been entered into the VACCR, the Washington state registry, and the NCDB, which populate the national cancer registries. Contract registry staff were educated regarding melanoma reporting requirements, particularly requirements for melanoma in situ. The 87202 SNOMED code for melanoma in situ also has been added to VistA at VAPSHCS. A follow-up study will be conducted to ascertain whether the interventions have corrected the underreporting of melanoma.

Study Limitations

The cases used in the study were obtained by SNOMED codes, CDW problem lists, and ICD-9 codes. This method may have missed cases that were assigned incorrect SNOMED codes and were not assigned to the problem list, or that were assigned to the problem list after the study period. The authors used a subset of all reportable cases—namely, those biopsied at VAPSHCS. Although this subset constituted the significant majority of reportable cases, the authors do not know the extent of underreporting of cases that were not biopsied at VAPSHCS. The extent to which other VA facilities generate local SNOMED codes also is unknown.

Conclusion

Melanoma underreporting at VAPSHCS is an addressable concern. The primary cause of underreporting was the use of locally generated SNOMED codes that were not recognized by cancer registry software. The present study should be repeated at other VA facilities to determine the extent to which its findings are generalizable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Stevan Knezevich for reviewing cases, Pam Pehan for providing the list of VAPSHCS melanomas accessioned from VistA, and Eddie Alaniz and Eugene Gavrilenko for helping ascertain SNOMED codes.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR). CDC website. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/about.htm. Updated April 20, 2016. Accessed July 1, 2016.

2. National Cancer Institute. Overview of the SEER program. National Cancer Institute website. http://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html. Accessed July 18, 2016.

3. Cancer Registries Amendment Act. 42 USC §201-280e (2016).

4. Cancer Registry of Greater California. Cancer reporting. Cancer Registry of Greater California website. http://crgc-cancer.org/hospitals-and-physicians. Accessed July 18, 2016.

5. American Academy of Dermatology. State cancer registry laws and requirements. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/file%20library/global%20navigatio/education%20and%20quality%20care/state%20cancer%20registries/state-cancer-registries-laws-and-requirements.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2016.

6. Craig BM, Rollison DE, List AF, Cogle CR. Underreporting of myeloid malignancies by United States cancer registries. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(3):474-481.

7. Fanning J, Gangestad A, Andrews SJ. National Cancer Data Base/Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results: potential insensitive-measure bias. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77(3):450-453.

8. Thoburn KK, German RR, Lewis M, Nichols PJ, Ahmed F, Jackson-Thompson J. Case completeness and data accuracy in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries. Cancer. 2007;109(8):1607-1616.

9. Cockburn M, Swetter SM, Peng D, Keegan TH, Deapen D, Clarke CA. Melanoma underreporting: why does it happen, how big is the problem, and how do we fix it? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(6):1081-1085.

10. Karagas MR, Thomas DB, Roth GJ, Johnson LK, Weiss NS. The effects of changes in health care delivery on the reported incidence of cutaneous melanoma in western Washington state. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133(1):58-62.

11. Merlino LA, Sullivan KJ, Whitaker DC, Lynch CF. The independent pathology laboratory as a reporting source for cutaneous melanoma incidence in Iowa, 1977–1994. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(4):578-585.

12. Cartee TV, Kini SP, Chen SC. Melanoma reporting to central cancer registries by US dermatologists: an analysis of the persistent knowledge and practice gap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5)(suppl 1):S124-S132.

13. Clegg LX, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN, Fay MP, Hankey BF. Impact of reporting delay and reporting error on cancer incidence rates and trends. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(20):1537-1545.

14. Odds ratio calculator. MedCalc website. https://www.medcalc.org/calc/odds_ratio.php. Accessed June 16, 2016.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are among the leading registries for cancer surveillance, collecting cancer epidemiology data for the majority of the U.S. population.1 This national coverage aids researchers and policymakers in conducting epidemiologic studies and allocating health resources.1,2

U.S. federal law mandates the reporting of cancer.3,4 State laws require cancer reporting as well, but requirements vary slightly from state to state.5 However, all cancers with an ICD-O (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology) code of 2 or 3 are reportable. For Washington state, cancer must be reported unless it is basal or squamous cell carcinoma of nonmucoepidermoid skin or in situ cancer of the uterine cervix.5 In general, each facility that diagnoses or treats a melanoma is required to report it. Data are consolidated at the central registry level if necessary.

Cancer reporting often fails to meet states’ requirements.6-8 Since the inception of SEER and NPCR, many studies have assessed the accuracy of the cancer data reported to these registries and have found these data to be inaccurate or incomplete.6-8 Melanoma reporting, in particular,

seems to be prone to error. Studies have demonstrated melanoma underreporting ranging from 10% to 70%, with an increase in underreporting over time.9-11 Significant delays of up to 10 years have been found between initial diagnosis and reporting for melanomas.12 In general, these studies have focused on smaller facilities, such as private laboratories, which lack in-house reporting systems.

Cancer reporting is especially important in the VHA, the largest U.S. health care system. Health data on about 9 million enrolled veterans have been invaluable for understanding cancer epidemiology. Underreporting and misreporting of cancer cases in private medical offices and smaller treatment facilities may be attributable to lack of funding, personnel, administrative support, or knowledge of reporting requirements. In contrast, the VHA requires cancer reporting and provides funding, personnel, and administrative support.13

The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) traditionally has employed registrars to perform the majority of basic cancer registry tasks, including abstracting, case finding, and lifelong follow-up of the cancer patients listed in the registry. The registrars use OncoTraX software, which finds possible cancer cases from pathology, radiology, and patient treatment files, to accession cases. Unique cancer cases are reported to the VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR), the Washington state registry, and the NCDB, which then transfer the data to the national registries. Accordingly, cases not accessioned would not be reported to the VA, state, and national registries.

The authors conducted a quality improvement project to ascertain whether primary cutaneous melanomas biopsied at VAPSHCS were underreported.

Materials

The VAPSHCS serves about 100,000 veterans and consists of 2 major treatment facilities, 2 community-based outpatient clinics, 1 outreach clinic, and 4 contract community-based outpatient clinics. Pathology cases for the entire VAPSHCS are accessioned in a central laboratory in Seattle.

Data Sources and Chart Abstraction

Data sources included the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), the VAPSHCS cancer registry, the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), VistA (Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture), VistA Web, and VistA Imaging.

Study Population

The study population consisted of veterans who had been diagnosed with primary cutaneous melanoma and had the diagnosis confirmed by biopsy performed at VAPSHCS between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2012.

Statistical Analysis

Odds ratios were calculated using the MedCalc Odds Ratio Calculator.14

Methods

The authors identified SNOMED (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine) codes that included the character string melanoma (Table 1). Using these codes, they queried VistA to identify melanoma cases diagnosed in the VAPSHCS Pathology and Laboratory Service during the period 2006 to 2012. To confirm the completeness of the local report, the authors performed the same search using the CDW. The SNOMED code case-finding was supplemented with cases ascertained using ICD-9 codes and problem list diagnoses.

A case must be reported to the local cancer registry if diagnosis or treatment takes place at the facility. All cases ascertained with the authors’ search criteria are, by definition, reportable to the local cancer registry. The authors then applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine

which cases were primary cutaneous melanomas and therefore candidates for this investigation (Table 2).

Having ascertained the primary cutaneous melanomas, the authors abstracted the pathology TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) staging (Breslow depth, mitotic index, presence of ulceration) and diagnosis dates from CPRS pathology reports. They then determined whether each case had been reported to the VACCR (OncoTraX was used to query for the accession status of each melanoma). If the melanoma was not accessioned, the authors tried to determine why.

Results

The authors discovered 193 primary cutaneous melanomas diagnosed by biopsy performed at VAPSHCS. Of these 193 melanomas, 71 (36.8%) had not been reported.

After the pathologist has completed a report, SNOMED codes are assigned by the pathology laboratory. Case finding with OncoTraX depends on SNOMED codes and other parameters (imaging, treatment, oncology consultation). OncoTraX is designed for case finding using World Health Organization (WHO) standardized 8000/X-9000/X series SNOMED codes. To understand the relationship between reporting and SNOMED codes, the authors ascertained the codes for all melanomas in the present study.

Table 3 lists the SNOMED codes assigned to melanomas biopsied at VAPSHCS and the percentage reported for each. Of the 106 melanomas that had been assigned WHO standardized codes, 101 (95.2%) had been reported. In contrast, only 21 (24.1%) of the 87 melanomas that had been assigned non-WHO standardized codes had been reported. In this study, non-WHO standardized codes are locally generated codes; they began with facility station number 663.

Use of locally generated codes may have contributed to nonreporting. Of the 71 melanomas not reported, 66 had a SNOMED code beginning with 663, and the other 5 had a WHO standardized SNOMED code. Odds of being nonreported were much higher for the melanomas with 663 codes than for the melanomas with WHO standardized codes (odds ratio [OR], 63.5; confidence interval [CI], 22.8-176.7; P ≤ .0001).

There was also a difference in coding between invasive and in situ melanomas. Of the 87 melanomas with a 663 code, 68 were in situ. Of the 106 melanomas with a national-level code, 11 were in situ. The odds of being assigned a local code were much higher for the in situ melanomas than they were for the invasive melanomas (OR, 30.9; CI, 13.8-69.1; P ≤ .0001).

Since 2000, the SNOMED code for melanoma in situ has been 87202, but no melanomas in situ were assigned this code. The 87202 code was not available in VistA for pathology laboratories to assign to melanomas at the time this study was conducted. Instead, most melanomas in situ were assigned a locally generated code. However, OncoTraX cannot recognize local codes, so melanomas assigned a local code might not have been accessionable.

The remaining 5 unreported melanomas were assigned WHO standardized codes. Secondary analysis revealed clerical errors, 4 made by the pathology laboratory and 1 by the registrar.

Discussion

Data from central cancer registries are used in a variety of fields, from research studies to health policymaking. They are used to “monitor cancer trends over time, show cancer patterns in various populations, identify high-risk groups, guide planning and evaluation of cancer control programs, help set priorities for allocating health resources, and advance clinical, epidemiologic, and health services research.”1

Melanoma underreporting has been demonstrated in previous studies, with the percentage of underreported cases varying from 10.4%11 to 70%.9 A longitudinal study of melanomas in Washington state found that underreporting of cutaneous melanomas increased from 2% to 21% over a 10-year period.10 This trend prompted examination of this study’s data for a similar temporal trend, and none was found.

A 2008 study found that more melanoma cases were being diagnosed or treated at outpatient facilities.9 Such facilities are prone to problems in reporting because they lack in-house reporting systems and knowledge of melanoma reporting requirements.9 A 2011 study of

practicing dermatologists found that many failed to report melanomas to a registry, and more than half were unaware of the requirement.12 Accordingly, underreporting is likely to continue. Results of the present study showed that melanoma underreporting was a major issue at VAPSHCS and that it could occur even in facilities that used in-house reporting systems and were aware of reporting requirements. The primary cause of underreporting was generation and use of local SNOMED codes that were unrecognizable by OncoTraX. A secondary cause was clerical error.

Discovery of unreported cases prompted facility review of procedures for reporting melanomas and expansion of current methods for melanoma discovery. All unreported cases have been entered into the VACCR, the Washington state registry, and the NCDB, which populate the national cancer registries. Contract registry staff were educated regarding melanoma reporting requirements, particularly requirements for melanoma in situ. The 87202 SNOMED code for melanoma in situ also has been added to VistA at VAPSHCS. A follow-up study will be conducted to ascertain whether the interventions have corrected the underreporting of melanoma.

Study Limitations

The cases used in the study were obtained by SNOMED codes, CDW problem lists, and ICD-9 codes. This method may have missed cases that were assigned incorrect SNOMED codes and were not assigned to the problem list, or that were assigned to the problem list after the study period. The authors used a subset of all reportable cases—namely, those biopsied at VAPSHCS. Although this subset constituted the significant majority of reportable cases, the authors do not know the extent of underreporting of cases that were not biopsied at VAPSHCS. The extent to which other VA facilities generate local SNOMED codes also is unknown.

Conclusion

Melanoma underreporting at VAPSHCS is an addressable concern. The primary cause of underreporting was the use of locally generated SNOMED codes that were not recognized by cancer registry software. The present study should be repeated at other VA facilities to determine the extent to which its findings are generalizable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Stevan Knezevich for reviewing cases, Pam Pehan for providing the list of VAPSHCS melanomas accessioned from VistA, and Eddie Alaniz and Eugene Gavrilenko for helping ascertain SNOMED codes.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are among the leading registries for cancer surveillance, collecting cancer epidemiology data for the majority of the U.S. population.1 This national coverage aids researchers and policymakers in conducting epidemiologic studies and allocating health resources.1,2

U.S. federal law mandates the reporting of cancer.3,4 State laws require cancer reporting as well, but requirements vary slightly from state to state.5 However, all cancers with an ICD-O (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology) code of 2 or 3 are reportable. For Washington state, cancer must be reported unless it is basal or squamous cell carcinoma of nonmucoepidermoid skin or in situ cancer of the uterine cervix.5 In general, each facility that diagnoses or treats a melanoma is required to report it. Data are consolidated at the central registry level if necessary.

Cancer reporting often fails to meet states’ requirements.6-8 Since the inception of SEER and NPCR, many studies have assessed the accuracy of the cancer data reported to these registries and have found these data to be inaccurate or incomplete.6-8 Melanoma reporting, in particular,

seems to be prone to error. Studies have demonstrated melanoma underreporting ranging from 10% to 70%, with an increase in underreporting over time.9-11 Significant delays of up to 10 years have been found between initial diagnosis and reporting for melanomas.12 In general, these studies have focused on smaller facilities, such as private laboratories, which lack in-house reporting systems.

Cancer reporting is especially important in the VHA, the largest U.S. health care system. Health data on about 9 million enrolled veterans have been invaluable for understanding cancer epidemiology. Underreporting and misreporting of cancer cases in private medical offices and smaller treatment facilities may be attributable to lack of funding, personnel, administrative support, or knowledge of reporting requirements. In contrast, the VHA requires cancer reporting and provides funding, personnel, and administrative support.13

The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) traditionally has employed registrars to perform the majority of basic cancer registry tasks, including abstracting, case finding, and lifelong follow-up of the cancer patients listed in the registry. The registrars use OncoTraX software, which finds possible cancer cases from pathology, radiology, and patient treatment files, to accession cases. Unique cancer cases are reported to the VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR), the Washington state registry, and the NCDB, which then transfer the data to the national registries. Accordingly, cases not accessioned would not be reported to the VA, state, and national registries.

The authors conducted a quality improvement project to ascertain whether primary cutaneous melanomas biopsied at VAPSHCS were underreported.

Materials

The VAPSHCS serves about 100,000 veterans and consists of 2 major treatment facilities, 2 community-based outpatient clinics, 1 outreach clinic, and 4 contract community-based outpatient clinics. Pathology cases for the entire VAPSHCS are accessioned in a central laboratory in Seattle.

Data Sources and Chart Abstraction

Data sources included the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), the VAPSHCS cancer registry, the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), VistA (Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture), VistA Web, and VistA Imaging.

Study Population

The study population consisted of veterans who had been diagnosed with primary cutaneous melanoma and had the diagnosis confirmed by biopsy performed at VAPSHCS between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2012.

Statistical Analysis

Odds ratios were calculated using the MedCalc Odds Ratio Calculator.14

Methods

The authors identified SNOMED (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine) codes that included the character string melanoma (Table 1). Using these codes, they queried VistA to identify melanoma cases diagnosed in the VAPSHCS Pathology and Laboratory Service during the period 2006 to 2012. To confirm the completeness of the local report, the authors performed the same search using the CDW. The SNOMED code case-finding was supplemented with cases ascertained using ICD-9 codes and problem list diagnoses.

A case must be reported to the local cancer registry if diagnosis or treatment takes place at the facility. All cases ascertained with the authors’ search criteria are, by definition, reportable to the local cancer registry. The authors then applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine

which cases were primary cutaneous melanomas and therefore candidates for this investigation (Table 2).

Having ascertained the primary cutaneous melanomas, the authors abstracted the pathology TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) staging (Breslow depth, mitotic index, presence of ulceration) and diagnosis dates from CPRS pathology reports. They then determined whether each case had been reported to the VACCR (OncoTraX was used to query for the accession status of each melanoma). If the melanoma was not accessioned, the authors tried to determine why.

Results

The authors discovered 193 primary cutaneous melanomas diagnosed by biopsy performed at VAPSHCS. Of these 193 melanomas, 71 (36.8%) had not been reported.

After the pathologist has completed a report, SNOMED codes are assigned by the pathology laboratory. Case finding with OncoTraX depends on SNOMED codes and other parameters (imaging, treatment, oncology consultation). OncoTraX is designed for case finding using World Health Organization (WHO) standardized 8000/X-9000/X series SNOMED codes. To understand the relationship between reporting and SNOMED codes, the authors ascertained the codes for all melanomas in the present study.

Table 3 lists the SNOMED codes assigned to melanomas biopsied at VAPSHCS and the percentage reported for each. Of the 106 melanomas that had been assigned WHO standardized codes, 101 (95.2%) had been reported. In contrast, only 21 (24.1%) of the 87 melanomas that had been assigned non-WHO standardized codes had been reported. In this study, non-WHO standardized codes are locally generated codes; they began with facility station number 663.

Use of locally generated codes may have contributed to nonreporting. Of the 71 melanomas not reported, 66 had a SNOMED code beginning with 663, and the other 5 had a WHO standardized SNOMED code. Odds of being nonreported were much higher for the melanomas with 663 codes than for the melanomas with WHO standardized codes (odds ratio [OR], 63.5; confidence interval [CI], 22.8-176.7; P ≤ .0001).

There was also a difference in coding between invasive and in situ melanomas. Of the 87 melanomas with a 663 code, 68 were in situ. Of the 106 melanomas with a national-level code, 11 were in situ. The odds of being assigned a local code were much higher for the in situ melanomas than they were for the invasive melanomas (OR, 30.9; CI, 13.8-69.1; P ≤ .0001).

Since 2000, the SNOMED code for melanoma in situ has been 87202, but no melanomas in situ were assigned this code. The 87202 code was not available in VistA for pathology laboratories to assign to melanomas at the time this study was conducted. Instead, most melanomas in situ were assigned a locally generated code. However, OncoTraX cannot recognize local codes, so melanomas assigned a local code might not have been accessionable.

The remaining 5 unreported melanomas were assigned WHO standardized codes. Secondary analysis revealed clerical errors, 4 made by the pathology laboratory and 1 by the registrar.

Discussion

Data from central cancer registries are used in a variety of fields, from research studies to health policymaking. They are used to “monitor cancer trends over time, show cancer patterns in various populations, identify high-risk groups, guide planning and evaluation of cancer control programs, help set priorities for allocating health resources, and advance clinical, epidemiologic, and health services research.”1

Melanoma underreporting has been demonstrated in previous studies, with the percentage of underreported cases varying from 10.4%11 to 70%.9 A longitudinal study of melanomas in Washington state found that underreporting of cutaneous melanomas increased from 2% to 21% over a 10-year period.10 This trend prompted examination of this study’s data for a similar temporal trend, and none was found.

A 2008 study found that more melanoma cases were being diagnosed or treated at outpatient facilities.9 Such facilities are prone to problems in reporting because they lack in-house reporting systems and knowledge of melanoma reporting requirements.9 A 2011 study of

practicing dermatologists found that many failed to report melanomas to a registry, and more than half were unaware of the requirement.12 Accordingly, underreporting is likely to continue. Results of the present study showed that melanoma underreporting was a major issue at VAPSHCS and that it could occur even in facilities that used in-house reporting systems and were aware of reporting requirements. The primary cause of underreporting was generation and use of local SNOMED codes that were unrecognizable by OncoTraX. A secondary cause was clerical error.

Discovery of unreported cases prompted facility review of procedures for reporting melanomas and expansion of current methods for melanoma discovery. All unreported cases have been entered into the VACCR, the Washington state registry, and the NCDB, which populate the national cancer registries. Contract registry staff were educated regarding melanoma reporting requirements, particularly requirements for melanoma in situ. The 87202 SNOMED code for melanoma in situ also has been added to VistA at VAPSHCS. A follow-up study will be conducted to ascertain whether the interventions have corrected the underreporting of melanoma.

Study Limitations

The cases used in the study were obtained by SNOMED codes, CDW problem lists, and ICD-9 codes. This method may have missed cases that were assigned incorrect SNOMED codes and were not assigned to the problem list, or that were assigned to the problem list after the study period. The authors used a subset of all reportable cases—namely, those biopsied at VAPSHCS. Although this subset constituted the significant majority of reportable cases, the authors do not know the extent of underreporting of cases that were not biopsied at VAPSHCS. The extent to which other VA facilities generate local SNOMED codes also is unknown.

Conclusion

Melanoma underreporting at VAPSHCS is an addressable concern. The primary cause of underreporting was the use of locally generated SNOMED codes that were not recognized by cancer registry software. The present study should be repeated at other VA facilities to determine the extent to which its findings are generalizable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Stevan Knezevich for reviewing cases, Pam Pehan for providing the list of VAPSHCS melanomas accessioned from VistA, and Eddie Alaniz and Eugene Gavrilenko for helping ascertain SNOMED codes.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR). CDC website. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/about.htm. Updated April 20, 2016. Accessed July 1, 2016.

2. National Cancer Institute. Overview of the SEER program. National Cancer Institute website. http://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html. Accessed July 18, 2016.

3. Cancer Registries Amendment Act. 42 USC §201-280e (2016).

4. Cancer Registry of Greater California. Cancer reporting. Cancer Registry of Greater California website. http://crgc-cancer.org/hospitals-and-physicians. Accessed July 18, 2016.

5. American Academy of Dermatology. State cancer registry laws and requirements. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/file%20library/global%20navigatio/education%20and%20quality%20care/state%20cancer%20registries/state-cancer-registries-laws-and-requirements.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2016.

6. Craig BM, Rollison DE, List AF, Cogle CR. Underreporting of myeloid malignancies by United States cancer registries. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(3):474-481.

7. Fanning J, Gangestad A, Andrews SJ. National Cancer Data Base/Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results: potential insensitive-measure bias. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77(3):450-453.

8. Thoburn KK, German RR, Lewis M, Nichols PJ, Ahmed F, Jackson-Thompson J. Case completeness and data accuracy in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries. Cancer. 2007;109(8):1607-1616.

9. Cockburn M, Swetter SM, Peng D, Keegan TH, Deapen D, Clarke CA. Melanoma underreporting: why does it happen, how big is the problem, and how do we fix it? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(6):1081-1085.

10. Karagas MR, Thomas DB, Roth GJ, Johnson LK, Weiss NS. The effects of changes in health care delivery on the reported incidence of cutaneous melanoma in western Washington state. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133(1):58-62.

11. Merlino LA, Sullivan KJ, Whitaker DC, Lynch CF. The independent pathology laboratory as a reporting source for cutaneous melanoma incidence in Iowa, 1977–1994. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(4):578-585.

12. Cartee TV, Kini SP, Chen SC. Melanoma reporting to central cancer registries by US dermatologists: an analysis of the persistent knowledge and practice gap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5)(suppl 1):S124-S132.

13. Clegg LX, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN, Fay MP, Hankey BF. Impact of reporting delay and reporting error on cancer incidence rates and trends. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(20):1537-1545.

14. Odds ratio calculator. MedCalc website. https://www.medcalc.org/calc/odds_ratio.php. Accessed June 16, 2016.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

1. Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR). CDC website. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/about.htm. Updated April 20, 2016. Accessed July 1, 2016.

2. National Cancer Institute. Overview of the SEER program. National Cancer Institute website. http://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html. Accessed July 18, 2016.

3. Cancer Registries Amendment Act. 42 USC §201-280e (2016).

4. Cancer Registry of Greater California. Cancer reporting. Cancer Registry of Greater California website. http://crgc-cancer.org/hospitals-and-physicians. Accessed July 18, 2016.

5. American Academy of Dermatology. State cancer registry laws and requirements. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/file%20library/global%20navigatio/education%20and%20quality%20care/state%20cancer%20registries/state-cancer-registries-laws-and-requirements.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2016.

6. Craig BM, Rollison DE, List AF, Cogle CR. Underreporting of myeloid malignancies by United States cancer registries. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(3):474-481.

7. Fanning J, Gangestad A, Andrews SJ. National Cancer Data Base/Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results: potential insensitive-measure bias. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77(3):450-453.

8. Thoburn KK, German RR, Lewis M, Nichols PJ, Ahmed F, Jackson-Thompson J. Case completeness and data accuracy in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries. Cancer. 2007;109(8):1607-1616.

9. Cockburn M, Swetter SM, Peng D, Keegan TH, Deapen D, Clarke CA. Melanoma underreporting: why does it happen, how big is the problem, and how do we fix it? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(6):1081-1085.

10. Karagas MR, Thomas DB, Roth GJ, Johnson LK, Weiss NS. The effects of changes in health care delivery on the reported incidence of cutaneous melanoma in western Washington state. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133(1):58-62.

11. Merlino LA, Sullivan KJ, Whitaker DC, Lynch CF. The independent pathology laboratory as a reporting source for cutaneous melanoma incidence in Iowa, 1977–1994. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(4):578-585.

12. Cartee TV, Kini SP, Chen SC. Melanoma reporting to central cancer registries by US dermatologists: an analysis of the persistent knowledge and practice gap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5)(suppl 1):S124-S132.

13. Clegg LX, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN, Fay MP, Hankey BF. Impact of reporting delay and reporting error on cancer incidence rates and trends. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(20):1537-1545.

14. Odds ratio calculator. MedCalc website. https://www.medcalc.org/calc/odds_ratio.php. Accessed June 16, 2016.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.