User login

CASE Depression, or something else?

Ms. A, age 56, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depressed mood, poor sleep, anhedonia, irritability, agitation, and recent self-injurious behavior; she had superficially cut her wrists. She also has a longstanding history of multiple sclerosis (MS), depression, and anxiety. She is admitted voluntarily to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

According to medical records, at age 32, Ms. A was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, which initially presented with facial numbness, and later with optic neuritis with transient loss of vision. As her disease progressed to the secondary progressive type, she experienced spasticity and vertigo. In the past few years, she also had experienced cognitive difficulties, particularly with memory and focus.

Ms. A has a history of recurrent depressive symptoms that began at an unspecified time after being diagnosed with MS. In the past few years, she had greatly increased her alcohol use in response to multiple psychosocial stressors and as an attempt to self-medicate MS-related pain. Several years ago, Ms. A had been admitted to a rehabilitation facility to address her alcohol use.

In the past, Ms. A’s depressive symptoms had been treated with various antidepressants, including fluoxetine (unspecified dose), which for a time was effective. The most recently prescribed antidepressant was duloxetine, 60 mg/d, which was discontinued because Ms. A felt it activated her mood lability. A few years before this current hospitalization, Ms. A had been started on a trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine (20 mg/10 mg, twice daily), which was discontinued due to concomitant use of an unspecified serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) and subsequent precipitation of serotonin syndrome.

At the time of this current admission to the psychiatric unit, Ms. A is being treated for MS with rituximab (10 mg/mL IV, every 6 months). Additionally, just before her admission, she was taking alprazolam (.25 mg, 3 times per day) for anxiety. She denies experiencing any spasticity or vision impairment.

[polldaddy:10175070]

The authors’ observations

We initially considered a diagnosis of MDD due to Ms. A’s past history of depressive episodes, her recent increase in tearfulness and anhedonia, and her self-injurious behaviors. However, diagnosis of a mood disorder was complicated by her complex history of longstanding MS and other psychosocial factors.

Continue to: Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS...

Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS, including the impact of the patient accepting a chronic and incurable diagnosis, the toll of progressive neurologic/physical disability and subsequent decline in functioning, and the availability of a support system.2 As opposed to disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, where disease progression is relatively more predictable, the culture of MS involves the obscurity of symptom fluctuation, both from the patient’s and/or clinician’s viewpoint. Psychiatric and neurologic symptoms may be difficult to predict, leading to speculation and projection as to the progression of the disease. The diagnosis of psychiatric conditions, such as depression, can be complicated by the fact that MS and psychiatric disorders share presenting symptoms; for example, disturbances in sleep and concentration may be seen in both conditions.

While studies have examined the neurobiology of MS lesions and their effects on mood symptoms, there has been no clear consensus of specific lesion distributions, although lesions in the superior frontal lobe and right temporal lobe regions have been identified in depressed MS patients.8 Lesions in the left frontal lobe may also have some contribution; studies have shown hyperintense lesion load in this area, which was found to be an independent predictor of MDD in MS.9 This, in turn, coincides with the association of left frontal cortex involvement in modulating affective depression, evidenced by studies that have associated depression severity with left frontal lobe damage in post-stroke patients10 as well as the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left prefrontal cortex for treatment-resistant MDD.11 Lesions along the orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex have similarly been connected to mood lability and impulsivity, which are characteristics of bipolar disorder.8 Within the general population, bipolar disorder is associated with areas of hyperintensity on MRI, particularly in the frontal and parietal white matter, which may provide clues as to the role of MS demyelinating lesions in similar locations, although research concerning the relationship between MS and bipolar disorder remains limited.12

EVALUATION No exacerbation of MS

Upon admission, Ms. A’s lability of affect is apparent as she quickly switches from being tearful to bright depending on the topic of discussion. She smiles when talking about the hobbies she enjoys and becomes tearful when speaking of personal problems within her family. She denies suicidal ideation/intent, shows no evidence of psychosis, and denies any history of bipolar disorder or recollection of hypomanic/manic symptoms. Overall, she exhibits low energy and difficulty sleeping, and reiterates her various psychosocial stressors, including her family history of depression and ongoing marital conflicts. Ms. A denies experiencing any acute exacerbations of clinical neurologic features of MS immediately before or during her admission. Laboratory values are normal, except for an elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) value of 11.136 uIU/mL, which is expected given her history of hypothyroidism. Results of the most recent brain MRI scans for Ms. A are pending.

The authors’ observations

Although we considered a diagnosis of bipolar disorder–mixed subtype, this was less likely to be the diagnosis considering her lack of any frank manic/hypomanic symptoms or history of such symptoms. Additionally, while we also considered a diagnosis of pseudobulbar affect due to her current mood swings and past trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine, this diagnosis was also less likely because Ms. A’s affect was not characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of emotion but was congruent with her experiences and surroundings. For example, Ms. A smiled when talking about her hobbies and became tearful when speaking of conflicts within her family.

Given Ms. A’s mood dysregulation and lability and her history of depressive episodes that began to manifest after her diagnosis of MS was established, and after ruling out other etiologic psychiatric disorders, a diagnosis of mood disorder secondary to MS was made.

[polldaddy:10175136]

Continue to: TREATMENT Mood stabilization

TREATMENT Mood stabilization

We start Ms. A on divalproex sodium, 250 mg 2 times a day, which is eventually titrated to 250 mg every morning with an additional daily 750 mg (total daily dose of 1,000 mg) for mood stabilization. Additionally, quetiapine, 50 mg nightly, is added and eventually titrated to 300 mg to augment mood stabilization and to aid sleep. Before being admitted, Ms. A had been prescribed

The authors’ observations

Definitive treatments for psychiatric conditions in patients with MS have been lacking, and current recommendations are based on regimens used to treat general psychiatric populations. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are frequently considered for treatment of MDD in patients with MS, whereas SNRIs are considered for patients with concomitant neuropathic pain.13 Similarly,

OUTCOME Improved mood, energy

After 2 weeks of inpatient treatment, Ms. A shows improvement in mood lability and energy levels, and she is able to tolerate titration of divalproex sodium and quetiapine to therapeutic levels. She is referred to an outpatient psychiatrist after discharge, as well as a follow-up appointment with her neurologist. On discharge, Ms. A expresses a commitment to treatment and hope for the future.

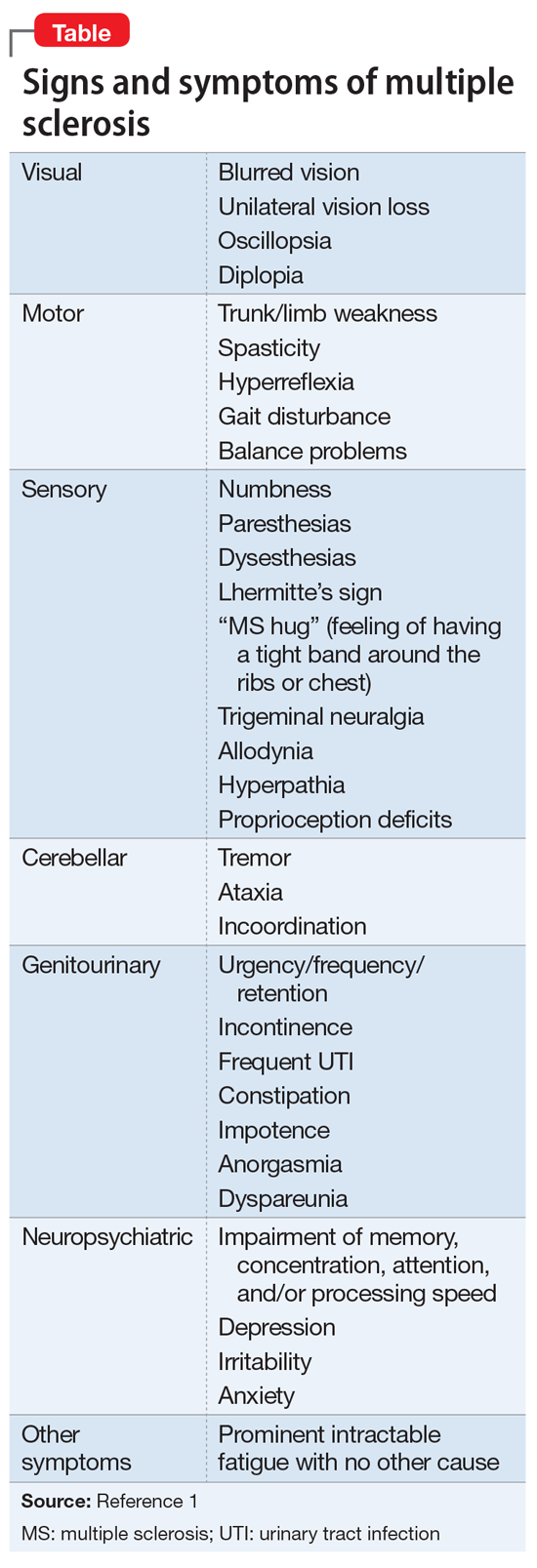

1. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Signs and symptoms consistent with demyelinating disease (for professionals). https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/Diagnosing-MS/Signs-and-Symptoms-Consistent-with-Demyelinating-D. Accessed October 29, 2018.

2. Politte LC, Huffman JC, Stern TA. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(4):318-324.

3. Siegert RJ, Abernethy D. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(4):469-475.

4. Scalfari A, Knappertz V, Cutter G, et al. Mortality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(2):184-192.

5. Ghaffar O, Feinstein A. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(3):278-285.

6. Duncan A, Malcolm-Smith S, Ameen O, et al. The incidence of euphoria in multiple sclerosis: artefact of measure. Mult Scler Int. 2016;2016:1-8.

7. Paparrigopoulos T, Ferentinos P, Kouzoupis A, et al. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: focus on disorders of mood, affect and behaviour. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):14-21.

8. Bakshi R, Czarnecki D, Shaikh ZA, et al. Brain MRI lesions and atrophy are related to depression in multiple sclerosis. Neuroreport. 2000;11(6):1153-1158.

9. Feinstein A, Roy P, Lobaugh N, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in multiple sclerosis patients with major depression. Neurology. 2004;62(4):586-590.

10. Hama S, Yamashita H, Shigenobu M, et al. Post-stroke affective or apathetic depression and lesion location: left frontal lobe and bilateral basal ganglia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257(3):149-152.

11. Carpenter LL, Janicak PG, Aaronson ST, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for major depression: a multisite, naturalistic, observational study of acute treatment outcomes in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(7):587-596.

12. Beyer JL, Young R, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Hyperintense MRI lesions in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis and review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(4):394-409.

13. Feinstein A. Neuropsychiatric syndromes associated with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2007;254(S2):1173-1176.

14. Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, et al. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004431.pub2.

CASE Depression, or something else?

Ms. A, age 56, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depressed mood, poor sleep, anhedonia, irritability, agitation, and recent self-injurious behavior; she had superficially cut her wrists. She also has a longstanding history of multiple sclerosis (MS), depression, and anxiety. She is admitted voluntarily to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

According to medical records, at age 32, Ms. A was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, which initially presented with facial numbness, and later with optic neuritis with transient loss of vision. As her disease progressed to the secondary progressive type, she experienced spasticity and vertigo. In the past few years, she also had experienced cognitive difficulties, particularly with memory and focus.

Ms. A has a history of recurrent depressive symptoms that began at an unspecified time after being diagnosed with MS. In the past few years, she had greatly increased her alcohol use in response to multiple psychosocial stressors and as an attempt to self-medicate MS-related pain. Several years ago, Ms. A had been admitted to a rehabilitation facility to address her alcohol use.

In the past, Ms. A’s depressive symptoms had been treated with various antidepressants, including fluoxetine (unspecified dose), which for a time was effective. The most recently prescribed antidepressant was duloxetine, 60 mg/d, which was discontinued because Ms. A felt it activated her mood lability. A few years before this current hospitalization, Ms. A had been started on a trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine (20 mg/10 mg, twice daily), which was discontinued due to concomitant use of an unspecified serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) and subsequent precipitation of serotonin syndrome.

At the time of this current admission to the psychiatric unit, Ms. A is being treated for MS with rituximab (10 mg/mL IV, every 6 months). Additionally, just before her admission, she was taking alprazolam (.25 mg, 3 times per day) for anxiety. She denies experiencing any spasticity or vision impairment.

[polldaddy:10175070]

The authors’ observations

We initially considered a diagnosis of MDD due to Ms. A’s past history of depressive episodes, her recent increase in tearfulness and anhedonia, and her self-injurious behaviors. However, diagnosis of a mood disorder was complicated by her complex history of longstanding MS and other psychosocial factors.

Continue to: Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS...

Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS, including the impact of the patient accepting a chronic and incurable diagnosis, the toll of progressive neurologic/physical disability and subsequent decline in functioning, and the availability of a support system.2 As opposed to disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, where disease progression is relatively more predictable, the culture of MS involves the obscurity of symptom fluctuation, both from the patient’s and/or clinician’s viewpoint. Psychiatric and neurologic symptoms may be difficult to predict, leading to speculation and projection as to the progression of the disease. The diagnosis of psychiatric conditions, such as depression, can be complicated by the fact that MS and psychiatric disorders share presenting symptoms; for example, disturbances in sleep and concentration may be seen in both conditions.

While studies have examined the neurobiology of MS lesions and their effects on mood symptoms, there has been no clear consensus of specific lesion distributions, although lesions in the superior frontal lobe and right temporal lobe regions have been identified in depressed MS patients.8 Lesions in the left frontal lobe may also have some contribution; studies have shown hyperintense lesion load in this area, which was found to be an independent predictor of MDD in MS.9 This, in turn, coincides with the association of left frontal cortex involvement in modulating affective depression, evidenced by studies that have associated depression severity with left frontal lobe damage in post-stroke patients10 as well as the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left prefrontal cortex for treatment-resistant MDD.11 Lesions along the orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex have similarly been connected to mood lability and impulsivity, which are characteristics of bipolar disorder.8 Within the general population, bipolar disorder is associated with areas of hyperintensity on MRI, particularly in the frontal and parietal white matter, which may provide clues as to the role of MS demyelinating lesions in similar locations, although research concerning the relationship between MS and bipolar disorder remains limited.12

EVALUATION No exacerbation of MS

Upon admission, Ms. A’s lability of affect is apparent as she quickly switches from being tearful to bright depending on the topic of discussion. She smiles when talking about the hobbies she enjoys and becomes tearful when speaking of personal problems within her family. She denies suicidal ideation/intent, shows no evidence of psychosis, and denies any history of bipolar disorder or recollection of hypomanic/manic symptoms. Overall, she exhibits low energy and difficulty sleeping, and reiterates her various psychosocial stressors, including her family history of depression and ongoing marital conflicts. Ms. A denies experiencing any acute exacerbations of clinical neurologic features of MS immediately before or during her admission. Laboratory values are normal, except for an elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) value of 11.136 uIU/mL, which is expected given her history of hypothyroidism. Results of the most recent brain MRI scans for Ms. A are pending.

The authors’ observations

Although we considered a diagnosis of bipolar disorder–mixed subtype, this was less likely to be the diagnosis considering her lack of any frank manic/hypomanic symptoms or history of such symptoms. Additionally, while we also considered a diagnosis of pseudobulbar affect due to her current mood swings and past trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine, this diagnosis was also less likely because Ms. A’s affect was not characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of emotion but was congruent with her experiences and surroundings. For example, Ms. A smiled when talking about her hobbies and became tearful when speaking of conflicts within her family.

Given Ms. A’s mood dysregulation and lability and her history of depressive episodes that began to manifest after her diagnosis of MS was established, and after ruling out other etiologic psychiatric disorders, a diagnosis of mood disorder secondary to MS was made.

[polldaddy:10175136]

Continue to: TREATMENT Mood stabilization

TREATMENT Mood stabilization

We start Ms. A on divalproex sodium, 250 mg 2 times a day, which is eventually titrated to 250 mg every morning with an additional daily 750 mg (total daily dose of 1,000 mg) for mood stabilization. Additionally, quetiapine, 50 mg nightly, is added and eventually titrated to 300 mg to augment mood stabilization and to aid sleep. Before being admitted, Ms. A had been prescribed

The authors’ observations

Definitive treatments for psychiatric conditions in patients with MS have been lacking, and current recommendations are based on regimens used to treat general psychiatric populations. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are frequently considered for treatment of MDD in patients with MS, whereas SNRIs are considered for patients with concomitant neuropathic pain.13 Similarly,

OUTCOME Improved mood, energy

After 2 weeks of inpatient treatment, Ms. A shows improvement in mood lability and energy levels, and she is able to tolerate titration of divalproex sodium and quetiapine to therapeutic levels. She is referred to an outpatient psychiatrist after discharge, as well as a follow-up appointment with her neurologist. On discharge, Ms. A expresses a commitment to treatment and hope for the future.

CASE Depression, or something else?

Ms. A, age 56, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depressed mood, poor sleep, anhedonia, irritability, agitation, and recent self-injurious behavior; she had superficially cut her wrists. She also has a longstanding history of multiple sclerosis (MS), depression, and anxiety. She is admitted voluntarily to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

According to medical records, at age 32, Ms. A was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, which initially presented with facial numbness, and later with optic neuritis with transient loss of vision. As her disease progressed to the secondary progressive type, she experienced spasticity and vertigo. In the past few years, she also had experienced cognitive difficulties, particularly with memory and focus.

Ms. A has a history of recurrent depressive symptoms that began at an unspecified time after being diagnosed with MS. In the past few years, she had greatly increased her alcohol use in response to multiple psychosocial stressors and as an attempt to self-medicate MS-related pain. Several years ago, Ms. A had been admitted to a rehabilitation facility to address her alcohol use.

In the past, Ms. A’s depressive symptoms had been treated with various antidepressants, including fluoxetine (unspecified dose), which for a time was effective. The most recently prescribed antidepressant was duloxetine, 60 mg/d, which was discontinued because Ms. A felt it activated her mood lability. A few years before this current hospitalization, Ms. A had been started on a trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine (20 mg/10 mg, twice daily), which was discontinued due to concomitant use of an unspecified serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) and subsequent precipitation of serotonin syndrome.

At the time of this current admission to the psychiatric unit, Ms. A is being treated for MS with rituximab (10 mg/mL IV, every 6 months). Additionally, just before her admission, she was taking alprazolam (.25 mg, 3 times per day) for anxiety. She denies experiencing any spasticity or vision impairment.

[polldaddy:10175070]

The authors’ observations

We initially considered a diagnosis of MDD due to Ms. A’s past history of depressive episodes, her recent increase in tearfulness and anhedonia, and her self-injurious behaviors. However, diagnosis of a mood disorder was complicated by her complex history of longstanding MS and other psychosocial factors.

Continue to: Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS...

Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS, including the impact of the patient accepting a chronic and incurable diagnosis, the toll of progressive neurologic/physical disability and subsequent decline in functioning, and the availability of a support system.2 As opposed to disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, where disease progression is relatively more predictable, the culture of MS involves the obscurity of symptom fluctuation, both from the patient’s and/or clinician’s viewpoint. Psychiatric and neurologic symptoms may be difficult to predict, leading to speculation and projection as to the progression of the disease. The diagnosis of psychiatric conditions, such as depression, can be complicated by the fact that MS and psychiatric disorders share presenting symptoms; for example, disturbances in sleep and concentration may be seen in both conditions.

While studies have examined the neurobiology of MS lesions and their effects on mood symptoms, there has been no clear consensus of specific lesion distributions, although lesions in the superior frontal lobe and right temporal lobe regions have been identified in depressed MS patients.8 Lesions in the left frontal lobe may also have some contribution; studies have shown hyperintense lesion load in this area, which was found to be an independent predictor of MDD in MS.9 This, in turn, coincides with the association of left frontal cortex involvement in modulating affective depression, evidenced by studies that have associated depression severity with left frontal lobe damage in post-stroke patients10 as well as the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left prefrontal cortex for treatment-resistant MDD.11 Lesions along the orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex have similarly been connected to mood lability and impulsivity, which are characteristics of bipolar disorder.8 Within the general population, bipolar disorder is associated with areas of hyperintensity on MRI, particularly in the frontal and parietal white matter, which may provide clues as to the role of MS demyelinating lesions in similar locations, although research concerning the relationship between MS and bipolar disorder remains limited.12

EVALUATION No exacerbation of MS

Upon admission, Ms. A’s lability of affect is apparent as she quickly switches from being tearful to bright depending on the topic of discussion. She smiles when talking about the hobbies she enjoys and becomes tearful when speaking of personal problems within her family. She denies suicidal ideation/intent, shows no evidence of psychosis, and denies any history of bipolar disorder or recollection of hypomanic/manic symptoms. Overall, she exhibits low energy and difficulty sleeping, and reiterates her various psychosocial stressors, including her family history of depression and ongoing marital conflicts. Ms. A denies experiencing any acute exacerbations of clinical neurologic features of MS immediately before or during her admission. Laboratory values are normal, except for an elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) value of 11.136 uIU/mL, which is expected given her history of hypothyroidism. Results of the most recent brain MRI scans for Ms. A are pending.

The authors’ observations

Although we considered a diagnosis of bipolar disorder–mixed subtype, this was less likely to be the diagnosis considering her lack of any frank manic/hypomanic symptoms or history of such symptoms. Additionally, while we also considered a diagnosis of pseudobulbar affect due to her current mood swings and past trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine, this diagnosis was also less likely because Ms. A’s affect was not characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of emotion but was congruent with her experiences and surroundings. For example, Ms. A smiled when talking about her hobbies and became tearful when speaking of conflicts within her family.

Given Ms. A’s mood dysregulation and lability and her history of depressive episodes that began to manifest after her diagnosis of MS was established, and after ruling out other etiologic psychiatric disorders, a diagnosis of mood disorder secondary to MS was made.

[polldaddy:10175136]

Continue to: TREATMENT Mood stabilization

TREATMENT Mood stabilization

We start Ms. A on divalproex sodium, 250 mg 2 times a day, which is eventually titrated to 250 mg every morning with an additional daily 750 mg (total daily dose of 1,000 mg) for mood stabilization. Additionally, quetiapine, 50 mg nightly, is added and eventually titrated to 300 mg to augment mood stabilization and to aid sleep. Before being admitted, Ms. A had been prescribed

The authors’ observations

Definitive treatments for psychiatric conditions in patients with MS have been lacking, and current recommendations are based on regimens used to treat general psychiatric populations. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are frequently considered for treatment of MDD in patients with MS, whereas SNRIs are considered for patients with concomitant neuropathic pain.13 Similarly,

OUTCOME Improved mood, energy

After 2 weeks of inpatient treatment, Ms. A shows improvement in mood lability and energy levels, and she is able to tolerate titration of divalproex sodium and quetiapine to therapeutic levels. She is referred to an outpatient psychiatrist after discharge, as well as a follow-up appointment with her neurologist. On discharge, Ms. A expresses a commitment to treatment and hope for the future.

1. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Signs and symptoms consistent with demyelinating disease (for professionals). https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/Diagnosing-MS/Signs-and-Symptoms-Consistent-with-Demyelinating-D. Accessed October 29, 2018.

2. Politte LC, Huffman JC, Stern TA. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(4):318-324.

3. Siegert RJ, Abernethy D. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(4):469-475.

4. Scalfari A, Knappertz V, Cutter G, et al. Mortality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(2):184-192.

5. Ghaffar O, Feinstein A. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(3):278-285.

6. Duncan A, Malcolm-Smith S, Ameen O, et al. The incidence of euphoria in multiple sclerosis: artefact of measure. Mult Scler Int. 2016;2016:1-8.

7. Paparrigopoulos T, Ferentinos P, Kouzoupis A, et al. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: focus on disorders of mood, affect and behaviour. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):14-21.

8. Bakshi R, Czarnecki D, Shaikh ZA, et al. Brain MRI lesions and atrophy are related to depression in multiple sclerosis. Neuroreport. 2000;11(6):1153-1158.

9. Feinstein A, Roy P, Lobaugh N, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in multiple sclerosis patients with major depression. Neurology. 2004;62(4):586-590.

10. Hama S, Yamashita H, Shigenobu M, et al. Post-stroke affective or apathetic depression and lesion location: left frontal lobe and bilateral basal ganglia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257(3):149-152.

11. Carpenter LL, Janicak PG, Aaronson ST, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for major depression: a multisite, naturalistic, observational study of acute treatment outcomes in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(7):587-596.

12. Beyer JL, Young R, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Hyperintense MRI lesions in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis and review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(4):394-409.

13. Feinstein A. Neuropsychiatric syndromes associated with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2007;254(S2):1173-1176.

14. Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, et al. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004431.pub2.

1. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Signs and symptoms consistent with demyelinating disease (for professionals). https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/Diagnosing-MS/Signs-and-Symptoms-Consistent-with-Demyelinating-D. Accessed October 29, 2018.

2. Politte LC, Huffman JC, Stern TA. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(4):318-324.

3. Siegert RJ, Abernethy D. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(4):469-475.

4. Scalfari A, Knappertz V, Cutter G, et al. Mortality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(2):184-192.

5. Ghaffar O, Feinstein A. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(3):278-285.

6. Duncan A, Malcolm-Smith S, Ameen O, et al. The incidence of euphoria in multiple sclerosis: artefact of measure. Mult Scler Int. 2016;2016:1-8.

7. Paparrigopoulos T, Ferentinos P, Kouzoupis A, et al. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: focus on disorders of mood, affect and behaviour. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):14-21.

8. Bakshi R, Czarnecki D, Shaikh ZA, et al. Brain MRI lesions and atrophy are related to depression in multiple sclerosis. Neuroreport. 2000;11(6):1153-1158.

9. Feinstein A, Roy P, Lobaugh N, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in multiple sclerosis patients with major depression. Neurology. 2004;62(4):586-590.

10. Hama S, Yamashita H, Shigenobu M, et al. Post-stroke affective or apathetic depression and lesion location: left frontal lobe and bilateral basal ganglia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257(3):149-152.

11. Carpenter LL, Janicak PG, Aaronson ST, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for major depression: a multisite, naturalistic, observational study of acute treatment outcomes in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(7):587-596.

12. Beyer JL, Young R, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Hyperintense MRI lesions in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis and review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(4):394-409.

13. Feinstein A. Neuropsychiatric syndromes associated with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2007;254(S2):1173-1176.

14. Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, et al. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004431.pub2.