User login

The VA and the DoD operate completely independent health care systems. Integrated provision of health care for the populations served is a compellingly attractive goal given the obvious overlaps, but has proven deceptively difficult to implement.

Despite efforts begun in 1998 to accomplish a reliable, comprehensive, bidirectional exchange of patient-specific health care information between systems, 16 years later this has yet to be reliably available. In most locales, VHA practitioners cannot easily access details of the medical care provided to DoD personnel. Attempts to merge the 2 electronic medical record (EMR) systems have also been fraught with difficulty.1 Even at the new, joint VHA/DoD Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center in North Chicago, Illinois (which opened in October 2010 to serve a mix of active-duty servicemen, TRICARE beneficiaries, and VA enrollees under a single roof), care using a single EMR system has not been possible.

The Institute of Medicine, in an invited review, has specifically criticized the unsatisfactory, piecemeal EMR integration.2 On February 5, 2013, the Secretary of the VA and the Secretary of Defense formally abandoned efforts to construct a single VA/DoD integrated EMR system by 2017. Instead, both organizations would, in then Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta’s words, “…focus our immediate efforts on integrating VA and DoD health data as quickly as possible, by focusing on interoperability and using existing solutions.”3

Joint VA/DoD health care programs in Northern California have abandoned merged structures in favor of mutual alignment. The practical value of aligning care systems is to extract benefit from structured, economically rational, win-win collaborations, as opposed to the forced merger approach. Mutual alignment generates relatively prompt, reliable results, to the benefit of all concerned.

Related: Developing Joint VA and DoD Health Programs

This report details a consistently favorable experience with this philosophy, which has considerable relevance as federal and nonfederal systems explore future joint ventures. Specifically, this report describes the substantial multiyear savings from a combination of various DoD/VA Joint Incentive Fund (JIF) and Sharing Agreement projects conducted by the VA Northern California Health Care System (VANCHCS) and the U.S. Air Force (USAF) 60th Medical Group’s (60MDG’s) David Grant Medical Center (DGMC).

Background and Methods

VA Northern California Health Care System currently serves 92,000 unique veteran patients in a service area of 40,000 square miles through a network of facilities and clinics at 9 sites across northern California. Rapid year-over-year growth of VANCHCS continues, and in fiscal year (FY) 2013, so-called unique enrolled veterans increased by 4.7%. David Grant Medical Center is a 116-bed DoD flagship hospital at Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield, California, which is home to the 60MDG. In 2013, VANCHCS and DGMC celebrated the 20th year of collaborative projects.

Congressional mandates encompassed in sections 101, 1701, 1782, 1783, and 8111 of Title 38, United States Code, as well as sections 1074, 1079, 1086, 1104, and Chapter 61 of Title 10, United States Code, have been addressed through a variety of DoD and VA Health Care Resource Sharing Program directives. The most recent instruction covering these agreements was reissued on January 23, 2012 (DoD instruction 6010.23). Sharing Agreements and joint ventures are permitted when such arrangements “…will improve access to quality health care or increase cost-effectiveness of the health care provided … to beneficiaries of both departments.” A Joint Executive Council (JEC), co-chaired by the VA Deputy Secretary and the DoD Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, oversees joint VA/DoD activities.

The collaborative initiatives described in this article have all blossomed into sustainable, ongoing, valuable programs. Aided by JIF grants, they transitioned to standard VHA and DoD budgetary mechanisms in the third year of operation. For the VHA, such ongoing funding is accomplished through the Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) budgeting system. Despite overall national/regional advantages, this funding model can result in substantial fiscal pressure for rapidly growing VHA systems, such as VANCHCS. DoD facilities and deployable operational teams, such as the 60MDG, are funded through separate DoD mechanisms. TRICARE services are funded through an entirely different budget. The complexities of this process preclude easy summary in this paper.

Recognizing that new collaborative initiatives inevitably add fiscal stress to involved facilities, the JEC has periodically offered 2-year competitive grant funding on a national basis to support winning proposals. Such JIF grants offer financial support to initiate potentially value-added collaborations. The VHA and DoD equally fund the annual award pool for these JIF grants. In response to periodic solicitations, VHA facilities team with DoD partners to jointly submit concept proposals.

Proposals emerging from separate review, revision, and approval by VHA/VA and USAF/DoD leadership are subjected to a rigorous business case analysis. The JEC then competitively scores the proposals according to transparent weighted criteria. High-scoring proposals enjoy support for renovation, equipment, and personnel for a transition period of 2 years. In the third year of ongoing operation, VHA funding (ie, VERA funding) and DoD funding, sometimes modified by a specific Memoranda of Understanding, pay for the third year, based on the workload during the first year of the program. As a result of third-year reimbursement based on previous volume and care provided, productivity under any new JIF-funded program is financially incentivized from day 1.

Each JIF proposal enumerates specific workload targets and time lines. In northern California, at quarterly intervals, a local VANCHCS-DGMC Joint Venture Executive Management Team (EMT) formally reviews clinical and financial metrics. This local EMT also reports results to the national-level JEC. Clinical metrics for most programs include visit count, consult count, procedure count, and the number of individuals treated in a given year, with breakdown tallies according to patients’ VA or DoD affiliation. Financial metrics include personnel costs, equipment costs, and revenue generated or saved. Savings for VHA patients can be calculated using CPT codes, Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG), and set CHAMPUS Maximum Allowable Charge (CMAC) rates, as calculated by the TRICARE Management Calculator (TMA Calculator).

Personnel serving in joint, integrated programs remain employees of either VHA or DoD, according to the staffing plan specified in the original JIF grant. Beyond the 2-year term of the original JIF grant, VANCHCS and DGMC can jointly adjust/expand staffing to meet increasing demand and programmatic needs. Personnel in joint programs work side by side and treat patients equally regardless of VA or DoD affiliation.

By agreement, EMR orders and EMR patient care documentation are entered according to norms for the organization where the care is delivered (usually DGMC for new inpatient programs). This facilitates identical treatment of patients in JIF programs. However, specific accommodations for inadequate cross talk between VHA and DoD EMR systems have proven necessary. Such accommodations have added cost, but not to a degree that jeopardizes any particular venture.

Findings

The mutual alignment approach shows a uniformly favorable 9-year experience with 9 joint VA/DoD clinical programs initiated through JIF grants totaling $29.6 million. Formal JIF closeout reports at the 2-year mark are available for 5 programs and document positive return on investment (ROI) for all programs averaging 83%.

The Joint Neurosurgery Program, planned through a 2005 JIF grant and implemented in 2006, offers a practical example of mutual alignment at work. Pre-JIF, both organizations had limited neurosurgery capability. War-related deployments undermined DGMC service, and ongoing community care expenses beyond $1.5 million per year for DoD beneficiaries seemed inevitable. VANCHCS in 2004-2005 referred nearly all cases to either neighboring VA systems or to community hospitals, suffering both lost VERA revenue on one hand and direct cost on the other. Unreliable care, long wait times, inefficiency, and dissatisfaction plagued the arrangements, which the staff at VANCHCS considered unacceptable.

Combining forces to provide better care made sense, but reorganizing for a fully merged Neurosurgical Service revealed daunting roadblocks. Eventually, merger frustration conceived a more productive, outcome-oriented, practical philosophy: mutual alignment. We recognized that minimizing change, flexibly capitalizing on opportunity, and reinforcing areas of strength could best achieve mutual joint goals. This mind-set facilitated speedy program assembly, in a “can do” collaborative atmosphere, and with gratifyingly little disruption.

Joint Neurosurgery JIF

The joint Neurosurgery JIF fused outpatient clinics to 1 hub location (a VA clinic adjacent to DGMC), left VA and DoD EMR arrangements intact, and established a single site (DGMC) for inpatient neurosurgical procedures. Dual-trained practitioners accessed both DoD and VA EMR systems, often using side-by-side computer stations. Inpatient work, by mutual agreement, used the DoD EMR exclusively. On inpatient discharge, however, a duplicate care summary was entered into the VHA CPRS EMR system.

Using JIF grants, a sophisticated image-guided surgery system was installed at DGMC, an underused operating room (OR) at DGMC was dedicated to neurosurgery, instruments were purchased, and VA nurses were hired to augment OR/ward/intensive care unit staffing at DGMC to support neurosurgical needs. The 3-year neurosurgery JIF budget totaled $5.5 million, 90% of which was dedicated to salaries for additional personnel to expand the service at DGMC. Deliverables included volume increases of 1,100 neurosurgical consultations per year, and at least 100 major procedures per year.

At the completion of the first 3 years of operation, the final report of the JIF noted a 12% ROI. In the post-JIF sustainment years, as joint volume increased further, the program added an additional VA neurosurgeon, a physician assistant, and other staff. Volume has steadily expanded, with 318 major neurosurgical procedures completed in FY 2013. In maintenance mode, consultations remain essentially free to each organization; VANCHCS is reimbursed for salary/benefits for hospital-based VHA personnel working at DGMC; and DGMC charges VANCHCS 75% of CMAC rates for the inpatient care delivered. The arrangement remains financially desirable for both organizations. For FY 2013 the joint relationship in neurosurgery generated a 22% ROI, saving taxpayers nearly $1 million per year. Most important, patients received prompt, excellent care. Waiting times for elective consults were routinely < 14 days, emergency care was reliably available, outcomes were excellent, and satisfaction at all levels have vastly improved.

Measuring Program Success

The funded and implemented JIF programs have all been successful, with positive ROI ranging from 10% to 284% (Table 1). Newer programs lacking a final closeout report are all on track for positive ROI. One additional JIF program, for a joint hematology-oncology center, was delayed by staffing challenges but has now commenced.

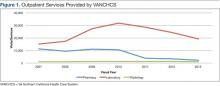

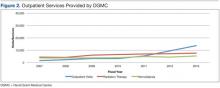

Over the past 7 years, outpatient volume and services provided by DGMC have increased. Outpatient support services provided by VANCHCS for DoD personnel at remote sites, while still substantial, diminished (Figures 1 and 2). Such changes reflect intentional concentration at DGMC. Also, a VHA pharmacy service provided to USAF personnel at a site distant from DGMC was intentionally downsized to embrace a mailed-medication program.

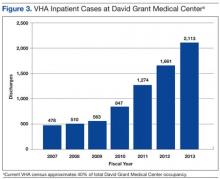

Inpatient hospital discharges for VHA enrollees and bed-days of care at DGMC have increased substantially (Figure 3). As a result of sharing programs and JIF programs, VHA enrollees currently account for about 40% of total hospital census at DGMC. About 108 professionals paid by VANCHCS currently work at DGMC. In most cases, as formalized in specific post-JIF sustainment agreements, VANCHCS is reimbursed for clinical staff salary and benefits if such staff are working at DGMC within a JIF program. For inpatient and procedural care, unless charges are specifically excluded as part of specific JIF agreements, VANCHCS pays DGMC at a rate of 75% of CMAC (ie, about 75% of Medicare rates) for every admission. Given geographic constraints, a VHA mandate to keep waits for specialty care under 14 days, and finite assistance levels from other VAMCs in VISN 21, a majority of these cases would otherwise be treated in community fee programs (at a higher cost of 100% of CMAC plus professional fees).

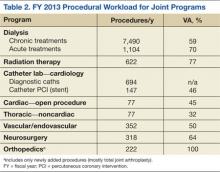

Volume has grown in all such programs (Table 2). Growth in the category of “open cardiac procedures,” however, has been intentionally limited by a VISN 21 requirement that care for VHA patients be provided only when existing VISN 21 cardiac programs cannot accommodate a particular case.

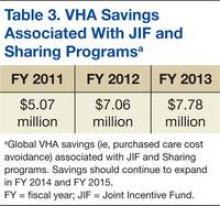

Since FY 2011, as a result of improved analytics, VANCHCS has been able to calculate its global savings (cost avoidance) stemming from all JIF and other sharing programs. Calculating the difference between community fee cost and DGMC cost as about 25% of CMAC (which offers a floor estimate of actual savings), these ongoing programs now save the VANCHCS $7.78 million per year (Table 3).

Positive overall federal ROI (ie, ROI from the taxpayer’s perspective), measured in dollars, is reported at the end of year 3 for every JIF-funded program. Substantial additional ROI could be captured by other metrics, such as timeliness of care and patient satisfaction, and would be favorable for all listed programs (data not shown).

Discussion

Had VANCHCS and DGMC attempted a merged information and management structure for the JIF programs, implementation would have been seriously delayed, if not entirely thwarted. Instead, by explicitly aligning efforts around each organization’s existing capabilities, assets and attributes, new valuable services were quickly developed. Patients now receive high-quality treatment in specialty areas not previously offered (and in some instances, not previously offered by either system).

As noted previously, the DoD and the VHA health care systems vary considerably. For DGMC and the 60MDG, during a time of war, optimal triage practices, safe/speedy transport, and the reliable delivery of appropriate trauma care for the injured warrior represent core missions. The VHA, on the other hand, is dedicated to the well-being, health, and lifetime medical-surgical care of enrolled veterans. The VHA population has relatively high numbers of elderly patients with serious chronic health conditions, such as heart disease, vascular disease, and cancer. VHA also provides subacute and rehabilitative care for younger veterans who served more recently in Iraq and Afghanistan. Overall, the VHA population stands quite distinct from that of our young active-duty forces and their dependents.

The VHA patient population (6.3 million patients receiving treatment and over 8.7 million enrolled) greatly exceeds that of the DoD. For this and other reasons, experience, current skills, and training differ considerably between VHA and DoD practitioners. For active-duty DoD practitioners, especially surgeons, the JIF projects provide avenues for development/maintenance of skills. Further, the JIF-enabled influx of VHA personnel at DGMC enhances staffing at DGMC, thereby improving the capacity of DGMC and the 60MDG’s potential surge capacity. Finally, ongoing joint programs have fostered provider relationships, academic opportunities, and training for DoD personnel between deployments.

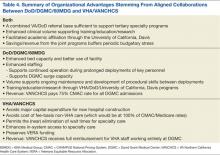

The effort also helps personnel satisfy new, quantitative, procedural volume standards (aka currency standards) for DoD/USAF surgeons. For VANCHCS, which is seriously pressed for acute inpatient capacity, the DGMC facility space and beds supporting the joint programs represent an attractive alternative to other options, such as new hospital construction, distant transfers, or reliance on community care (Table 4).

The JIF submission process encourages thoughtful planning and specific identification of resources necessary for success. The intra-and extra-organizational review process, as well as competitive national-level scoring, encourages thrift and innovation. Funded project proposals are generally compelling. Some JIF programs are constructed anew, combining space, bed capacity, and commitment with the requisite staffing, equipment, and team development to ensure safe startup. Examples include the neurosurgery and heart-lung-vascular programs. Others, like the orthopedics program, expand existing capabilities. In each instance, the new programs benefit all concerned: the federal taxpayer, each organization, and patients.

Outside Support and New Programs

The UC Davis Health System (UCDHS), through high-level education, training, and staffing, has explicitly supported these joint programs. Reliable, safe initiation, particularly for the cardiac and vascular programs, would not have been otherwise possible. Key staff members often hold academic faculty appointments, teach, write, and participate in UCDHS programs at all levels. Research in trauma care and other topics has also been facilitated. The positive relationship has supported joint program infrastructure, recruitment, and enhanced/maintained quality.

Multiple successful JIF collaborations and sharing projects, have generated a further, unforeseen benefit: The emergence of an intra-agency, financially relevant, federal market for innovative proposals. This has been coupled in the northern California setting with an emerging willingness by both organizations to potentially sustain a short-term loss for long-term financial or programmatic gain. Strict accounting between organizations, with real dollars going back and forth, has created pools of uncommitted profit, which organizational leaders can use to fund proposals not previously feasible given otherwise daunting fiscal constraints.

One recent example is a non-JIF program for patients requiring general surgery care. Under a no-load pilot program, some DoD surgeons work without additional compensation at VANCHCS facilities, and some general surgery operations are performed at DGMC. This serves to both maintain DoD practitioners’ clinical volume between deployments, and simultaneously address temporary VHA backlogs. Previous and current sharing agreement revenue, complemented by goodwill, supports the exchange. In this particular instance, previous JIF experience has cultivated innovation. Analysis and market discipline will determine its fate.

Limitations

Obstacles thwarting potential joint projects include inadequate projected case volume, logistical constraints, and inadequate ROI. Geographic challenges also limit collaboration in certain areas. The VANCHCS system covers 40,000 square miles. Emergency acute care for a patient mandates use of the nearest capable facility, often a local nonfederal facility. Inadequate communication between VHA and DoD EMR systems, exacerbated by privacy and security protections initiated by both organizations, also tends to block collaboration.

Notwithstanding the alignment over merger philosophy, merged information systems, or at least a faster, more reliable cross talk tool would certainly help. Bidirectional Healthcare Information Exchange (BHIE), if implemented more reliably, might still work. As a work-around, practitioners in joint programs usually practice with a VHA computer and a DoD computer side by side in order to obtain complete information for a given patient. Providers view this as ridiculous. However, all involved respect the need for intact DoD and VHA firewall/security systems.

These collaborative ventures have been created in a unique budgetary environment. Wars end. Congress adjusts budgets. Health care systems change. One or the other partner periodically experiences serious budgetary stress. However, the back-and-forth revenue streams described here tend to smooth the transitions. Despite budgetary and programmatic stress, we are maintaining/expanding all of the joint programs described herein. These programs deliver sustained, cost-effective care with improved access for veterans and military beneficiaries alike and continue to do so through planned, mutually aligned effort, not merger.

Acknowledgements

Current and former commanders of the 60th Medical Group at DGMC: Col Rawson Wood (current commander); Col Kevin Connelly, MD ; Col Brian Hayes, MD; Col Lee Payne, MD.

Current and former directors of VANCHCS: David Stockwell (current director); Brian O’Neill, MD; Lawrence Sandler; Lucille Swanson. UC Davis: Kenneth W. Kizer, MD, MPH, The Institute for Population Health Improvement, and The Center for Veterans and Military Health.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Panangala SV, Jansen DJ. Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs: Status of the Integrated Electronic Health Record (iEHR). Federation of American Scientists Website. http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42970.pdf. Published February 26, 2013. Accessed November 11, 2014.

2. Committee on Evaluation of the Lovell Federal Health Care Center Merger; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine. Evaluation of the Lovell Federal Health Care Center Merger: Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations (2012). The National Academies Press Website. http://www.iom.edu/evaluatinglovell. Released October 12, 2012. Accessed November 5, 2014.

3. U.S. Department of Defense. Remarks by Secretary Panetta and Secretary Shinseki from the Department of Veterans Affairs [News transcript]. U.S. Department of Defense Website. http://www.defense.gov/Transcripts/Transcript.aspx?TranscriptID=5187. Published February 5, 2013. Accessed November 5, 2014.

The VA and the DoD operate completely independent health care systems. Integrated provision of health care for the populations served is a compellingly attractive goal given the obvious overlaps, but has proven deceptively difficult to implement.

Despite efforts begun in 1998 to accomplish a reliable, comprehensive, bidirectional exchange of patient-specific health care information between systems, 16 years later this has yet to be reliably available. In most locales, VHA practitioners cannot easily access details of the medical care provided to DoD personnel. Attempts to merge the 2 electronic medical record (EMR) systems have also been fraught with difficulty.1 Even at the new, joint VHA/DoD Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center in North Chicago, Illinois (which opened in October 2010 to serve a mix of active-duty servicemen, TRICARE beneficiaries, and VA enrollees under a single roof), care using a single EMR system has not been possible.

The Institute of Medicine, in an invited review, has specifically criticized the unsatisfactory, piecemeal EMR integration.2 On February 5, 2013, the Secretary of the VA and the Secretary of Defense formally abandoned efforts to construct a single VA/DoD integrated EMR system by 2017. Instead, both organizations would, in then Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta’s words, “…focus our immediate efforts on integrating VA and DoD health data as quickly as possible, by focusing on interoperability and using existing solutions.”3

Joint VA/DoD health care programs in Northern California have abandoned merged structures in favor of mutual alignment. The practical value of aligning care systems is to extract benefit from structured, economically rational, win-win collaborations, as opposed to the forced merger approach. Mutual alignment generates relatively prompt, reliable results, to the benefit of all concerned.

Related: Developing Joint VA and DoD Health Programs

This report details a consistently favorable experience with this philosophy, which has considerable relevance as federal and nonfederal systems explore future joint ventures. Specifically, this report describes the substantial multiyear savings from a combination of various DoD/VA Joint Incentive Fund (JIF) and Sharing Agreement projects conducted by the VA Northern California Health Care System (VANCHCS) and the U.S. Air Force (USAF) 60th Medical Group’s (60MDG’s) David Grant Medical Center (DGMC).

Background and Methods

VA Northern California Health Care System currently serves 92,000 unique veteran patients in a service area of 40,000 square miles through a network of facilities and clinics at 9 sites across northern California. Rapid year-over-year growth of VANCHCS continues, and in fiscal year (FY) 2013, so-called unique enrolled veterans increased by 4.7%. David Grant Medical Center is a 116-bed DoD flagship hospital at Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield, California, which is home to the 60MDG. In 2013, VANCHCS and DGMC celebrated the 20th year of collaborative projects.

Congressional mandates encompassed in sections 101, 1701, 1782, 1783, and 8111 of Title 38, United States Code, as well as sections 1074, 1079, 1086, 1104, and Chapter 61 of Title 10, United States Code, have been addressed through a variety of DoD and VA Health Care Resource Sharing Program directives. The most recent instruction covering these agreements was reissued on January 23, 2012 (DoD instruction 6010.23). Sharing Agreements and joint ventures are permitted when such arrangements “…will improve access to quality health care or increase cost-effectiveness of the health care provided … to beneficiaries of both departments.” A Joint Executive Council (JEC), co-chaired by the VA Deputy Secretary and the DoD Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, oversees joint VA/DoD activities.

The collaborative initiatives described in this article have all blossomed into sustainable, ongoing, valuable programs. Aided by JIF grants, they transitioned to standard VHA and DoD budgetary mechanisms in the third year of operation. For the VHA, such ongoing funding is accomplished through the Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) budgeting system. Despite overall national/regional advantages, this funding model can result in substantial fiscal pressure for rapidly growing VHA systems, such as VANCHCS. DoD facilities and deployable operational teams, such as the 60MDG, are funded through separate DoD mechanisms. TRICARE services are funded through an entirely different budget. The complexities of this process preclude easy summary in this paper.

Recognizing that new collaborative initiatives inevitably add fiscal stress to involved facilities, the JEC has periodically offered 2-year competitive grant funding on a national basis to support winning proposals. Such JIF grants offer financial support to initiate potentially value-added collaborations. The VHA and DoD equally fund the annual award pool for these JIF grants. In response to periodic solicitations, VHA facilities team with DoD partners to jointly submit concept proposals.

Proposals emerging from separate review, revision, and approval by VHA/VA and USAF/DoD leadership are subjected to a rigorous business case analysis. The JEC then competitively scores the proposals according to transparent weighted criteria. High-scoring proposals enjoy support for renovation, equipment, and personnel for a transition period of 2 years. In the third year of ongoing operation, VHA funding (ie, VERA funding) and DoD funding, sometimes modified by a specific Memoranda of Understanding, pay for the third year, based on the workload during the first year of the program. As a result of third-year reimbursement based on previous volume and care provided, productivity under any new JIF-funded program is financially incentivized from day 1.

Each JIF proposal enumerates specific workload targets and time lines. In northern California, at quarterly intervals, a local VANCHCS-DGMC Joint Venture Executive Management Team (EMT) formally reviews clinical and financial metrics. This local EMT also reports results to the national-level JEC. Clinical metrics for most programs include visit count, consult count, procedure count, and the number of individuals treated in a given year, with breakdown tallies according to patients’ VA or DoD affiliation. Financial metrics include personnel costs, equipment costs, and revenue generated or saved. Savings for VHA patients can be calculated using CPT codes, Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG), and set CHAMPUS Maximum Allowable Charge (CMAC) rates, as calculated by the TRICARE Management Calculator (TMA Calculator).

Personnel serving in joint, integrated programs remain employees of either VHA or DoD, according to the staffing plan specified in the original JIF grant. Beyond the 2-year term of the original JIF grant, VANCHCS and DGMC can jointly adjust/expand staffing to meet increasing demand and programmatic needs. Personnel in joint programs work side by side and treat patients equally regardless of VA or DoD affiliation.

By agreement, EMR orders and EMR patient care documentation are entered according to norms for the organization where the care is delivered (usually DGMC for new inpatient programs). This facilitates identical treatment of patients in JIF programs. However, specific accommodations for inadequate cross talk between VHA and DoD EMR systems have proven necessary. Such accommodations have added cost, but not to a degree that jeopardizes any particular venture.

Findings

The mutual alignment approach shows a uniformly favorable 9-year experience with 9 joint VA/DoD clinical programs initiated through JIF grants totaling $29.6 million. Formal JIF closeout reports at the 2-year mark are available for 5 programs and document positive return on investment (ROI) for all programs averaging 83%.

The Joint Neurosurgery Program, planned through a 2005 JIF grant and implemented in 2006, offers a practical example of mutual alignment at work. Pre-JIF, both organizations had limited neurosurgery capability. War-related deployments undermined DGMC service, and ongoing community care expenses beyond $1.5 million per year for DoD beneficiaries seemed inevitable. VANCHCS in 2004-2005 referred nearly all cases to either neighboring VA systems or to community hospitals, suffering both lost VERA revenue on one hand and direct cost on the other. Unreliable care, long wait times, inefficiency, and dissatisfaction plagued the arrangements, which the staff at VANCHCS considered unacceptable.

Combining forces to provide better care made sense, but reorganizing for a fully merged Neurosurgical Service revealed daunting roadblocks. Eventually, merger frustration conceived a more productive, outcome-oriented, practical philosophy: mutual alignment. We recognized that minimizing change, flexibly capitalizing on opportunity, and reinforcing areas of strength could best achieve mutual joint goals. This mind-set facilitated speedy program assembly, in a “can do” collaborative atmosphere, and with gratifyingly little disruption.

Joint Neurosurgery JIF

The joint Neurosurgery JIF fused outpatient clinics to 1 hub location (a VA clinic adjacent to DGMC), left VA and DoD EMR arrangements intact, and established a single site (DGMC) for inpatient neurosurgical procedures. Dual-trained practitioners accessed both DoD and VA EMR systems, often using side-by-side computer stations. Inpatient work, by mutual agreement, used the DoD EMR exclusively. On inpatient discharge, however, a duplicate care summary was entered into the VHA CPRS EMR system.

Using JIF grants, a sophisticated image-guided surgery system was installed at DGMC, an underused operating room (OR) at DGMC was dedicated to neurosurgery, instruments were purchased, and VA nurses were hired to augment OR/ward/intensive care unit staffing at DGMC to support neurosurgical needs. The 3-year neurosurgery JIF budget totaled $5.5 million, 90% of which was dedicated to salaries for additional personnel to expand the service at DGMC. Deliverables included volume increases of 1,100 neurosurgical consultations per year, and at least 100 major procedures per year.

At the completion of the first 3 years of operation, the final report of the JIF noted a 12% ROI. In the post-JIF sustainment years, as joint volume increased further, the program added an additional VA neurosurgeon, a physician assistant, and other staff. Volume has steadily expanded, with 318 major neurosurgical procedures completed in FY 2013. In maintenance mode, consultations remain essentially free to each organization; VANCHCS is reimbursed for salary/benefits for hospital-based VHA personnel working at DGMC; and DGMC charges VANCHCS 75% of CMAC rates for the inpatient care delivered. The arrangement remains financially desirable for both organizations. For FY 2013 the joint relationship in neurosurgery generated a 22% ROI, saving taxpayers nearly $1 million per year. Most important, patients received prompt, excellent care. Waiting times for elective consults were routinely < 14 days, emergency care was reliably available, outcomes were excellent, and satisfaction at all levels have vastly improved.

Measuring Program Success

The funded and implemented JIF programs have all been successful, with positive ROI ranging from 10% to 284% (Table 1). Newer programs lacking a final closeout report are all on track for positive ROI. One additional JIF program, for a joint hematology-oncology center, was delayed by staffing challenges but has now commenced.

Over the past 7 years, outpatient volume and services provided by DGMC have increased. Outpatient support services provided by VANCHCS for DoD personnel at remote sites, while still substantial, diminished (Figures 1 and 2). Such changes reflect intentional concentration at DGMC. Also, a VHA pharmacy service provided to USAF personnel at a site distant from DGMC was intentionally downsized to embrace a mailed-medication program.

Inpatient hospital discharges for VHA enrollees and bed-days of care at DGMC have increased substantially (Figure 3). As a result of sharing programs and JIF programs, VHA enrollees currently account for about 40% of total hospital census at DGMC. About 108 professionals paid by VANCHCS currently work at DGMC. In most cases, as formalized in specific post-JIF sustainment agreements, VANCHCS is reimbursed for clinical staff salary and benefits if such staff are working at DGMC within a JIF program. For inpatient and procedural care, unless charges are specifically excluded as part of specific JIF agreements, VANCHCS pays DGMC at a rate of 75% of CMAC (ie, about 75% of Medicare rates) for every admission. Given geographic constraints, a VHA mandate to keep waits for specialty care under 14 days, and finite assistance levels from other VAMCs in VISN 21, a majority of these cases would otherwise be treated in community fee programs (at a higher cost of 100% of CMAC plus professional fees).

Volume has grown in all such programs (Table 2). Growth in the category of “open cardiac procedures,” however, has been intentionally limited by a VISN 21 requirement that care for VHA patients be provided only when existing VISN 21 cardiac programs cannot accommodate a particular case.

Since FY 2011, as a result of improved analytics, VANCHCS has been able to calculate its global savings (cost avoidance) stemming from all JIF and other sharing programs. Calculating the difference between community fee cost and DGMC cost as about 25% of CMAC (which offers a floor estimate of actual savings), these ongoing programs now save the VANCHCS $7.78 million per year (Table 3).

Positive overall federal ROI (ie, ROI from the taxpayer’s perspective), measured in dollars, is reported at the end of year 3 for every JIF-funded program. Substantial additional ROI could be captured by other metrics, such as timeliness of care and patient satisfaction, and would be favorable for all listed programs (data not shown).

Discussion

Had VANCHCS and DGMC attempted a merged information and management structure for the JIF programs, implementation would have been seriously delayed, if not entirely thwarted. Instead, by explicitly aligning efforts around each organization’s existing capabilities, assets and attributes, new valuable services were quickly developed. Patients now receive high-quality treatment in specialty areas not previously offered (and in some instances, not previously offered by either system).

As noted previously, the DoD and the VHA health care systems vary considerably. For DGMC and the 60MDG, during a time of war, optimal triage practices, safe/speedy transport, and the reliable delivery of appropriate trauma care for the injured warrior represent core missions. The VHA, on the other hand, is dedicated to the well-being, health, and lifetime medical-surgical care of enrolled veterans. The VHA population has relatively high numbers of elderly patients with serious chronic health conditions, such as heart disease, vascular disease, and cancer. VHA also provides subacute and rehabilitative care for younger veterans who served more recently in Iraq and Afghanistan. Overall, the VHA population stands quite distinct from that of our young active-duty forces and their dependents.

The VHA patient population (6.3 million patients receiving treatment and over 8.7 million enrolled) greatly exceeds that of the DoD. For this and other reasons, experience, current skills, and training differ considerably between VHA and DoD practitioners. For active-duty DoD practitioners, especially surgeons, the JIF projects provide avenues for development/maintenance of skills. Further, the JIF-enabled influx of VHA personnel at DGMC enhances staffing at DGMC, thereby improving the capacity of DGMC and the 60MDG’s potential surge capacity. Finally, ongoing joint programs have fostered provider relationships, academic opportunities, and training for DoD personnel between deployments.

The effort also helps personnel satisfy new, quantitative, procedural volume standards (aka currency standards) for DoD/USAF surgeons. For VANCHCS, which is seriously pressed for acute inpatient capacity, the DGMC facility space and beds supporting the joint programs represent an attractive alternative to other options, such as new hospital construction, distant transfers, or reliance on community care (Table 4).

The JIF submission process encourages thoughtful planning and specific identification of resources necessary for success. The intra-and extra-organizational review process, as well as competitive national-level scoring, encourages thrift and innovation. Funded project proposals are generally compelling. Some JIF programs are constructed anew, combining space, bed capacity, and commitment with the requisite staffing, equipment, and team development to ensure safe startup. Examples include the neurosurgery and heart-lung-vascular programs. Others, like the orthopedics program, expand existing capabilities. In each instance, the new programs benefit all concerned: the federal taxpayer, each organization, and patients.

Outside Support and New Programs

The UC Davis Health System (UCDHS), through high-level education, training, and staffing, has explicitly supported these joint programs. Reliable, safe initiation, particularly for the cardiac and vascular programs, would not have been otherwise possible. Key staff members often hold academic faculty appointments, teach, write, and participate in UCDHS programs at all levels. Research in trauma care and other topics has also been facilitated. The positive relationship has supported joint program infrastructure, recruitment, and enhanced/maintained quality.

Multiple successful JIF collaborations and sharing projects, have generated a further, unforeseen benefit: The emergence of an intra-agency, financially relevant, federal market for innovative proposals. This has been coupled in the northern California setting with an emerging willingness by both organizations to potentially sustain a short-term loss for long-term financial or programmatic gain. Strict accounting between organizations, with real dollars going back and forth, has created pools of uncommitted profit, which organizational leaders can use to fund proposals not previously feasible given otherwise daunting fiscal constraints.

One recent example is a non-JIF program for patients requiring general surgery care. Under a no-load pilot program, some DoD surgeons work without additional compensation at VANCHCS facilities, and some general surgery operations are performed at DGMC. This serves to both maintain DoD practitioners’ clinical volume between deployments, and simultaneously address temporary VHA backlogs. Previous and current sharing agreement revenue, complemented by goodwill, supports the exchange. In this particular instance, previous JIF experience has cultivated innovation. Analysis and market discipline will determine its fate.

Limitations

Obstacles thwarting potential joint projects include inadequate projected case volume, logistical constraints, and inadequate ROI. Geographic challenges also limit collaboration in certain areas. The VANCHCS system covers 40,000 square miles. Emergency acute care for a patient mandates use of the nearest capable facility, often a local nonfederal facility. Inadequate communication between VHA and DoD EMR systems, exacerbated by privacy and security protections initiated by both organizations, also tends to block collaboration.

Notwithstanding the alignment over merger philosophy, merged information systems, or at least a faster, more reliable cross talk tool would certainly help. Bidirectional Healthcare Information Exchange (BHIE), if implemented more reliably, might still work. As a work-around, practitioners in joint programs usually practice with a VHA computer and a DoD computer side by side in order to obtain complete information for a given patient. Providers view this as ridiculous. However, all involved respect the need for intact DoD and VHA firewall/security systems.

These collaborative ventures have been created in a unique budgetary environment. Wars end. Congress adjusts budgets. Health care systems change. One or the other partner periodically experiences serious budgetary stress. However, the back-and-forth revenue streams described here tend to smooth the transitions. Despite budgetary and programmatic stress, we are maintaining/expanding all of the joint programs described herein. These programs deliver sustained, cost-effective care with improved access for veterans and military beneficiaries alike and continue to do so through planned, mutually aligned effort, not merger.

Acknowledgements

Current and former commanders of the 60th Medical Group at DGMC: Col Rawson Wood (current commander); Col Kevin Connelly, MD ; Col Brian Hayes, MD; Col Lee Payne, MD.

Current and former directors of VANCHCS: David Stockwell (current director); Brian O’Neill, MD; Lawrence Sandler; Lucille Swanson. UC Davis: Kenneth W. Kizer, MD, MPH, The Institute for Population Health Improvement, and The Center for Veterans and Military Health.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

The VA and the DoD operate completely independent health care systems. Integrated provision of health care for the populations served is a compellingly attractive goal given the obvious overlaps, but has proven deceptively difficult to implement.

Despite efforts begun in 1998 to accomplish a reliable, comprehensive, bidirectional exchange of patient-specific health care information between systems, 16 years later this has yet to be reliably available. In most locales, VHA practitioners cannot easily access details of the medical care provided to DoD personnel. Attempts to merge the 2 electronic medical record (EMR) systems have also been fraught with difficulty.1 Even at the new, joint VHA/DoD Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center in North Chicago, Illinois (which opened in October 2010 to serve a mix of active-duty servicemen, TRICARE beneficiaries, and VA enrollees under a single roof), care using a single EMR system has not been possible.

The Institute of Medicine, in an invited review, has specifically criticized the unsatisfactory, piecemeal EMR integration.2 On February 5, 2013, the Secretary of the VA and the Secretary of Defense formally abandoned efforts to construct a single VA/DoD integrated EMR system by 2017. Instead, both organizations would, in then Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta’s words, “…focus our immediate efforts on integrating VA and DoD health data as quickly as possible, by focusing on interoperability and using existing solutions.”3

Joint VA/DoD health care programs in Northern California have abandoned merged structures in favor of mutual alignment. The practical value of aligning care systems is to extract benefit from structured, economically rational, win-win collaborations, as opposed to the forced merger approach. Mutual alignment generates relatively prompt, reliable results, to the benefit of all concerned.

Related: Developing Joint VA and DoD Health Programs

This report details a consistently favorable experience with this philosophy, which has considerable relevance as federal and nonfederal systems explore future joint ventures. Specifically, this report describes the substantial multiyear savings from a combination of various DoD/VA Joint Incentive Fund (JIF) and Sharing Agreement projects conducted by the VA Northern California Health Care System (VANCHCS) and the U.S. Air Force (USAF) 60th Medical Group’s (60MDG’s) David Grant Medical Center (DGMC).

Background and Methods

VA Northern California Health Care System currently serves 92,000 unique veteran patients in a service area of 40,000 square miles through a network of facilities and clinics at 9 sites across northern California. Rapid year-over-year growth of VANCHCS continues, and in fiscal year (FY) 2013, so-called unique enrolled veterans increased by 4.7%. David Grant Medical Center is a 116-bed DoD flagship hospital at Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield, California, which is home to the 60MDG. In 2013, VANCHCS and DGMC celebrated the 20th year of collaborative projects.

Congressional mandates encompassed in sections 101, 1701, 1782, 1783, and 8111 of Title 38, United States Code, as well as sections 1074, 1079, 1086, 1104, and Chapter 61 of Title 10, United States Code, have been addressed through a variety of DoD and VA Health Care Resource Sharing Program directives. The most recent instruction covering these agreements was reissued on January 23, 2012 (DoD instruction 6010.23). Sharing Agreements and joint ventures are permitted when such arrangements “…will improve access to quality health care or increase cost-effectiveness of the health care provided … to beneficiaries of both departments.” A Joint Executive Council (JEC), co-chaired by the VA Deputy Secretary and the DoD Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, oversees joint VA/DoD activities.

The collaborative initiatives described in this article have all blossomed into sustainable, ongoing, valuable programs. Aided by JIF grants, they transitioned to standard VHA and DoD budgetary mechanisms in the third year of operation. For the VHA, such ongoing funding is accomplished through the Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) budgeting system. Despite overall national/regional advantages, this funding model can result in substantial fiscal pressure for rapidly growing VHA systems, such as VANCHCS. DoD facilities and deployable operational teams, such as the 60MDG, are funded through separate DoD mechanisms. TRICARE services are funded through an entirely different budget. The complexities of this process preclude easy summary in this paper.

Recognizing that new collaborative initiatives inevitably add fiscal stress to involved facilities, the JEC has periodically offered 2-year competitive grant funding on a national basis to support winning proposals. Such JIF grants offer financial support to initiate potentially value-added collaborations. The VHA and DoD equally fund the annual award pool for these JIF grants. In response to periodic solicitations, VHA facilities team with DoD partners to jointly submit concept proposals.

Proposals emerging from separate review, revision, and approval by VHA/VA and USAF/DoD leadership are subjected to a rigorous business case analysis. The JEC then competitively scores the proposals according to transparent weighted criteria. High-scoring proposals enjoy support for renovation, equipment, and personnel for a transition period of 2 years. In the third year of ongoing operation, VHA funding (ie, VERA funding) and DoD funding, sometimes modified by a specific Memoranda of Understanding, pay for the third year, based on the workload during the first year of the program. As a result of third-year reimbursement based on previous volume and care provided, productivity under any new JIF-funded program is financially incentivized from day 1.

Each JIF proposal enumerates specific workload targets and time lines. In northern California, at quarterly intervals, a local VANCHCS-DGMC Joint Venture Executive Management Team (EMT) formally reviews clinical and financial metrics. This local EMT also reports results to the national-level JEC. Clinical metrics for most programs include visit count, consult count, procedure count, and the number of individuals treated in a given year, with breakdown tallies according to patients’ VA or DoD affiliation. Financial metrics include personnel costs, equipment costs, and revenue generated or saved. Savings for VHA patients can be calculated using CPT codes, Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG), and set CHAMPUS Maximum Allowable Charge (CMAC) rates, as calculated by the TRICARE Management Calculator (TMA Calculator).

Personnel serving in joint, integrated programs remain employees of either VHA or DoD, according to the staffing plan specified in the original JIF grant. Beyond the 2-year term of the original JIF grant, VANCHCS and DGMC can jointly adjust/expand staffing to meet increasing demand and programmatic needs. Personnel in joint programs work side by side and treat patients equally regardless of VA or DoD affiliation.

By agreement, EMR orders and EMR patient care documentation are entered according to norms for the organization where the care is delivered (usually DGMC for new inpatient programs). This facilitates identical treatment of patients in JIF programs. However, specific accommodations for inadequate cross talk between VHA and DoD EMR systems have proven necessary. Such accommodations have added cost, but not to a degree that jeopardizes any particular venture.

Findings

The mutual alignment approach shows a uniformly favorable 9-year experience with 9 joint VA/DoD clinical programs initiated through JIF grants totaling $29.6 million. Formal JIF closeout reports at the 2-year mark are available for 5 programs and document positive return on investment (ROI) for all programs averaging 83%.

The Joint Neurosurgery Program, planned through a 2005 JIF grant and implemented in 2006, offers a practical example of mutual alignment at work. Pre-JIF, both organizations had limited neurosurgery capability. War-related deployments undermined DGMC service, and ongoing community care expenses beyond $1.5 million per year for DoD beneficiaries seemed inevitable. VANCHCS in 2004-2005 referred nearly all cases to either neighboring VA systems or to community hospitals, suffering both lost VERA revenue on one hand and direct cost on the other. Unreliable care, long wait times, inefficiency, and dissatisfaction plagued the arrangements, which the staff at VANCHCS considered unacceptable.

Combining forces to provide better care made sense, but reorganizing for a fully merged Neurosurgical Service revealed daunting roadblocks. Eventually, merger frustration conceived a more productive, outcome-oriented, practical philosophy: mutual alignment. We recognized that minimizing change, flexibly capitalizing on opportunity, and reinforcing areas of strength could best achieve mutual joint goals. This mind-set facilitated speedy program assembly, in a “can do” collaborative atmosphere, and with gratifyingly little disruption.

Joint Neurosurgery JIF

The joint Neurosurgery JIF fused outpatient clinics to 1 hub location (a VA clinic adjacent to DGMC), left VA and DoD EMR arrangements intact, and established a single site (DGMC) for inpatient neurosurgical procedures. Dual-trained practitioners accessed both DoD and VA EMR systems, often using side-by-side computer stations. Inpatient work, by mutual agreement, used the DoD EMR exclusively. On inpatient discharge, however, a duplicate care summary was entered into the VHA CPRS EMR system.

Using JIF grants, a sophisticated image-guided surgery system was installed at DGMC, an underused operating room (OR) at DGMC was dedicated to neurosurgery, instruments were purchased, and VA nurses were hired to augment OR/ward/intensive care unit staffing at DGMC to support neurosurgical needs. The 3-year neurosurgery JIF budget totaled $5.5 million, 90% of which was dedicated to salaries for additional personnel to expand the service at DGMC. Deliverables included volume increases of 1,100 neurosurgical consultations per year, and at least 100 major procedures per year.

At the completion of the first 3 years of operation, the final report of the JIF noted a 12% ROI. In the post-JIF sustainment years, as joint volume increased further, the program added an additional VA neurosurgeon, a physician assistant, and other staff. Volume has steadily expanded, with 318 major neurosurgical procedures completed in FY 2013. In maintenance mode, consultations remain essentially free to each organization; VANCHCS is reimbursed for salary/benefits for hospital-based VHA personnel working at DGMC; and DGMC charges VANCHCS 75% of CMAC rates for the inpatient care delivered. The arrangement remains financially desirable for both organizations. For FY 2013 the joint relationship in neurosurgery generated a 22% ROI, saving taxpayers nearly $1 million per year. Most important, patients received prompt, excellent care. Waiting times for elective consults were routinely < 14 days, emergency care was reliably available, outcomes were excellent, and satisfaction at all levels have vastly improved.

Measuring Program Success

The funded and implemented JIF programs have all been successful, with positive ROI ranging from 10% to 284% (Table 1). Newer programs lacking a final closeout report are all on track for positive ROI. One additional JIF program, for a joint hematology-oncology center, was delayed by staffing challenges but has now commenced.

Over the past 7 years, outpatient volume and services provided by DGMC have increased. Outpatient support services provided by VANCHCS for DoD personnel at remote sites, while still substantial, diminished (Figures 1 and 2). Such changes reflect intentional concentration at DGMC. Also, a VHA pharmacy service provided to USAF personnel at a site distant from DGMC was intentionally downsized to embrace a mailed-medication program.

Inpatient hospital discharges for VHA enrollees and bed-days of care at DGMC have increased substantially (Figure 3). As a result of sharing programs and JIF programs, VHA enrollees currently account for about 40% of total hospital census at DGMC. About 108 professionals paid by VANCHCS currently work at DGMC. In most cases, as formalized in specific post-JIF sustainment agreements, VANCHCS is reimbursed for clinical staff salary and benefits if such staff are working at DGMC within a JIF program. For inpatient and procedural care, unless charges are specifically excluded as part of specific JIF agreements, VANCHCS pays DGMC at a rate of 75% of CMAC (ie, about 75% of Medicare rates) for every admission. Given geographic constraints, a VHA mandate to keep waits for specialty care under 14 days, and finite assistance levels from other VAMCs in VISN 21, a majority of these cases would otherwise be treated in community fee programs (at a higher cost of 100% of CMAC plus professional fees).

Volume has grown in all such programs (Table 2). Growth in the category of “open cardiac procedures,” however, has been intentionally limited by a VISN 21 requirement that care for VHA patients be provided only when existing VISN 21 cardiac programs cannot accommodate a particular case.

Since FY 2011, as a result of improved analytics, VANCHCS has been able to calculate its global savings (cost avoidance) stemming from all JIF and other sharing programs. Calculating the difference between community fee cost and DGMC cost as about 25% of CMAC (which offers a floor estimate of actual savings), these ongoing programs now save the VANCHCS $7.78 million per year (Table 3).

Positive overall federal ROI (ie, ROI from the taxpayer’s perspective), measured in dollars, is reported at the end of year 3 for every JIF-funded program. Substantial additional ROI could be captured by other metrics, such as timeliness of care and patient satisfaction, and would be favorable for all listed programs (data not shown).

Discussion

Had VANCHCS and DGMC attempted a merged information and management structure for the JIF programs, implementation would have been seriously delayed, if not entirely thwarted. Instead, by explicitly aligning efforts around each organization’s existing capabilities, assets and attributes, new valuable services were quickly developed. Patients now receive high-quality treatment in specialty areas not previously offered (and in some instances, not previously offered by either system).

As noted previously, the DoD and the VHA health care systems vary considerably. For DGMC and the 60MDG, during a time of war, optimal triage practices, safe/speedy transport, and the reliable delivery of appropriate trauma care for the injured warrior represent core missions. The VHA, on the other hand, is dedicated to the well-being, health, and lifetime medical-surgical care of enrolled veterans. The VHA population has relatively high numbers of elderly patients with serious chronic health conditions, such as heart disease, vascular disease, and cancer. VHA also provides subacute and rehabilitative care for younger veterans who served more recently in Iraq and Afghanistan. Overall, the VHA population stands quite distinct from that of our young active-duty forces and their dependents.

The VHA patient population (6.3 million patients receiving treatment and over 8.7 million enrolled) greatly exceeds that of the DoD. For this and other reasons, experience, current skills, and training differ considerably between VHA and DoD practitioners. For active-duty DoD practitioners, especially surgeons, the JIF projects provide avenues for development/maintenance of skills. Further, the JIF-enabled influx of VHA personnel at DGMC enhances staffing at DGMC, thereby improving the capacity of DGMC and the 60MDG’s potential surge capacity. Finally, ongoing joint programs have fostered provider relationships, academic opportunities, and training for DoD personnel between deployments.

The effort also helps personnel satisfy new, quantitative, procedural volume standards (aka currency standards) for DoD/USAF surgeons. For VANCHCS, which is seriously pressed for acute inpatient capacity, the DGMC facility space and beds supporting the joint programs represent an attractive alternative to other options, such as new hospital construction, distant transfers, or reliance on community care (Table 4).

The JIF submission process encourages thoughtful planning and specific identification of resources necessary for success. The intra-and extra-organizational review process, as well as competitive national-level scoring, encourages thrift and innovation. Funded project proposals are generally compelling. Some JIF programs are constructed anew, combining space, bed capacity, and commitment with the requisite staffing, equipment, and team development to ensure safe startup. Examples include the neurosurgery and heart-lung-vascular programs. Others, like the orthopedics program, expand existing capabilities. In each instance, the new programs benefit all concerned: the federal taxpayer, each organization, and patients.

Outside Support and New Programs

The UC Davis Health System (UCDHS), through high-level education, training, and staffing, has explicitly supported these joint programs. Reliable, safe initiation, particularly for the cardiac and vascular programs, would not have been otherwise possible. Key staff members often hold academic faculty appointments, teach, write, and participate in UCDHS programs at all levels. Research in trauma care and other topics has also been facilitated. The positive relationship has supported joint program infrastructure, recruitment, and enhanced/maintained quality.

Multiple successful JIF collaborations and sharing projects, have generated a further, unforeseen benefit: The emergence of an intra-agency, financially relevant, federal market for innovative proposals. This has been coupled in the northern California setting with an emerging willingness by both organizations to potentially sustain a short-term loss for long-term financial or programmatic gain. Strict accounting between organizations, with real dollars going back and forth, has created pools of uncommitted profit, which organizational leaders can use to fund proposals not previously feasible given otherwise daunting fiscal constraints.

One recent example is a non-JIF program for patients requiring general surgery care. Under a no-load pilot program, some DoD surgeons work without additional compensation at VANCHCS facilities, and some general surgery operations are performed at DGMC. This serves to both maintain DoD practitioners’ clinical volume between deployments, and simultaneously address temporary VHA backlogs. Previous and current sharing agreement revenue, complemented by goodwill, supports the exchange. In this particular instance, previous JIF experience has cultivated innovation. Analysis and market discipline will determine its fate.

Limitations

Obstacles thwarting potential joint projects include inadequate projected case volume, logistical constraints, and inadequate ROI. Geographic challenges also limit collaboration in certain areas. The VANCHCS system covers 40,000 square miles. Emergency acute care for a patient mandates use of the nearest capable facility, often a local nonfederal facility. Inadequate communication between VHA and DoD EMR systems, exacerbated by privacy and security protections initiated by both organizations, also tends to block collaboration.

Notwithstanding the alignment over merger philosophy, merged information systems, or at least a faster, more reliable cross talk tool would certainly help. Bidirectional Healthcare Information Exchange (BHIE), if implemented more reliably, might still work. As a work-around, practitioners in joint programs usually practice with a VHA computer and a DoD computer side by side in order to obtain complete information for a given patient. Providers view this as ridiculous. However, all involved respect the need for intact DoD and VHA firewall/security systems.

These collaborative ventures have been created in a unique budgetary environment. Wars end. Congress adjusts budgets. Health care systems change. One or the other partner periodically experiences serious budgetary stress. However, the back-and-forth revenue streams described here tend to smooth the transitions. Despite budgetary and programmatic stress, we are maintaining/expanding all of the joint programs described herein. These programs deliver sustained, cost-effective care with improved access for veterans and military beneficiaries alike and continue to do so through planned, mutually aligned effort, not merger.

Acknowledgements

Current and former commanders of the 60th Medical Group at DGMC: Col Rawson Wood (current commander); Col Kevin Connelly, MD ; Col Brian Hayes, MD; Col Lee Payne, MD.

Current and former directors of VANCHCS: David Stockwell (current director); Brian O’Neill, MD; Lawrence Sandler; Lucille Swanson. UC Davis: Kenneth W. Kizer, MD, MPH, The Institute for Population Health Improvement, and The Center for Veterans and Military Health.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Panangala SV, Jansen DJ. Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs: Status of the Integrated Electronic Health Record (iEHR). Federation of American Scientists Website. http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42970.pdf. Published February 26, 2013. Accessed November 11, 2014.

2. Committee on Evaluation of the Lovell Federal Health Care Center Merger; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine. Evaluation of the Lovell Federal Health Care Center Merger: Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations (2012). The National Academies Press Website. http://www.iom.edu/evaluatinglovell. Released October 12, 2012. Accessed November 5, 2014.

3. U.S. Department of Defense. Remarks by Secretary Panetta and Secretary Shinseki from the Department of Veterans Affairs [News transcript]. U.S. Department of Defense Website. http://www.defense.gov/Transcripts/Transcript.aspx?TranscriptID=5187. Published February 5, 2013. Accessed November 5, 2014.

1. Panangala SV, Jansen DJ. Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs: Status of the Integrated Electronic Health Record (iEHR). Federation of American Scientists Website. http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42970.pdf. Published February 26, 2013. Accessed November 11, 2014.

2. Committee on Evaluation of the Lovell Federal Health Care Center Merger; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine. Evaluation of the Lovell Federal Health Care Center Merger: Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations (2012). The National Academies Press Website. http://www.iom.edu/evaluatinglovell. Released October 12, 2012. Accessed November 5, 2014.

3. U.S. Department of Defense. Remarks by Secretary Panetta and Secretary Shinseki from the Department of Veterans Affairs [News transcript]. U.S. Department of Defense Website. http://www.defense.gov/Transcripts/Transcript.aspx?TranscriptID=5187. Published February 5, 2013. Accessed November 5, 2014.