User login

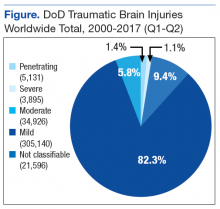

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a health concern for the U.S. Military Health System (MHS) as well as the VHA. It occurs in both deployed and nondeployed settings; however, Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and improved reporting mechanisms have dramatically increased TBI diagnoses in active-duty service members. According to the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC), more than 370,000 service members have been diagnosed with a TBI since 2000 (Figure).1

Background

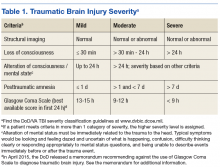

The DoD and the VA are collaborating on clinical research studies to identify, understand, and treat the long-term effects of TBI that can affect patients and their families. Most TBIs are mild (mTBIs), also called concussions, and patients typically recover within a few weeks (Table 1). However, some individuals with mTBI experience symptoms that may persist for months or years. A meta-analysis by Perry and colleagues showed that the prevalence or risk of a neurologic disorder, depression, or other mental health issue following mTBI was 67% higher compared with that in uninjured controls.2

Patients with any severity of TBI may require assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), such as bathing, dressing, managing medications, and feeding. Patients also may need help with instrumental ADLs, such as meal preparation, grocery shopping, household chores, child care, getting to appointments or activities, coordination of educational and vocational services, financial and benefits management, and supportive listening.

Increased injuries have spurred the DoD and VA to coordinate health care to provide a seamless transition for patients between the 2 agencies. However, individuals who sustained a TBI may need various levels of caregiver assistance over time.

TBI and Caregivers

Despite better agency coordination for patients, caregivers can experience stress. Griffin and colleagues found that caregiving responsibilities can compete with other demands on the caregiver, such as work and family, and may negatively impact their health and finances.3,4

Lou and colleagues studied the factors associated with caring for chronically ill family members that may result in stress for the caregivers.5 Along with an unaccounted for economic contribution, caregivers may face lost work time and pay and limitations on work travel and work advancement. Additionally, lost time for leisure, travel, social activities, family obligations, and retirement could result in physical and mental drain on the caregiver. Stress may reach a level at which the caregivers risk psychological distress. The study also noted that families with perceived high stress experience disrupted family functioning. Some TBI caregiver studies sought to understand how best to evaluate and determine the level of caregiver burden, and other studies investigated appropriate interventions.6-9

Health care practitioners within the federal health care system may benefit from a greater awareness of caregiver needs and caregiver resources. Caregiver support can improve outcomes for both the caregiver and care recipient, and many organizations and resources already exist to assist the caregiver. This article reviews recent published literature on TBI caregivers of patients with TBI across civilian, military, and veteran populations and lists caregiver resources for additional information, assistance, and support.

Literature Review

The DVBIC defines the term caregiver as “any family or support person(s) relied upon by the service member or veteran with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who assumes primary responsibility for ensuring the needed level of care and overall well-being of that service member or veteran. A family or family caregiver may include spouse, parents, children, other extended family members, as well as significant others and friends.”3

In the following discussion, findings from military and veteran literature are separated from civilian population findings to highlight similarities and differences between these 2 bodies of research. Several of the studies in the military/veteran cohorts include polytrauma patients with comorbid physical and mental health issues not necessarily found in civilian literature.

Civilian Literature

A 2015 systematic review by Anderson and colleagues on coping and psychological adjustment in TBI caregivers indicated no Class I or Class II studies.10 Four Class III and 3 Class IV studies were found. The authors suggest that more rigorous studies (ie, Class I and II) are needed.

Despite these limitations, peer-reviewed literature indicates that the levels of stress and distress in TBI caregivers are consistent with reports for other diseases. In a civilian population, Carlozzi and colleagues found that TBI caregivers who reported stress, distress, anxiety, and feeling overwhelmed often had concerns for their social, emotional, physical, cognitive health, as well as feelings of loss.5 In addition, caregivers may need to take leaves of absence or leave the workforce entirely to provide for a family member or friend who had a TBI—often leading to financial strain (eg, depleting assets, accumulating debt). These challenges may occur during prime earning years, and the caregiver may lose the ability to resume work if the care receiver requires care for extended periods.11

Kratz and colleagues showed that caregivers of individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI: (1) felt overburdened with responsibilities; (2) lacked personal time and time for self-care; (3) felt their lives were interrupted or lost; (4) grieved the loss of the person with TBI; and (5) endorsed anger, guilt, anxiety, and sadness.12

Perceptions differed between caregiver parents and caregiver partners. Parents expressed feelings of grief and sadness related to the “loss of the person before the TBI.” Parents also reported a sense of guilt and responsibility for their child’s TBI and feelings of being tied down to the individual with TBI. Parents experienced a greater level of stress if the son or daughter with TBI still lived at home. Partners expressed frustration and despair related to their role as sole decision maker and care provider. Partners’ distress also related to the partner relationship and the relationship between children and the individual with TBI.

Verhasghe and colleagues found that partners experience a greater degree of stress than do parents.13 Young families with minimal social support for coping with financial, psychiatric, and medical problems were the most vulnerable to stress. A systematic review by Ennis and colleagues evaluated depression and anxiety in caregiver parents vs spouses.14 Although methods and quality differed in the studies, findings indicated high levels of distress regardless of the type of caregiver.

Anderson and colleagues used the Ways of Coping Questionnaire to evaluate the association between coping and psychological adjustment in caregivers of TBI individuals.10 The use of emotion-focused coping and problem solving was possibly associated with psychological adjustment in caregivers. Verhasghe and colleagues indicated that the nature of the injuries more than the severity of TBI determined the level of stress up to 15 years after the TBI.13 Gender and social and professional support also influenced coping. The review identified the need to develop models of long-term support and care.

An Australian cohort of 79 family caregivers participated in a study by Perlesz and colleagues.15 Participants’ caregiving responsibilities averaged 19.3 months posttrauma. The Family Satisfaction Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, State Anxiety Inventory, and Profile of Mood States were used in this analysis. Male caregivers reported distress in terms of anger and fatigue; female caregivers were at greatest risk of poor psychosocial outcomes. Although findings from primary caregivers indicated that 35% to 49% displayed enough distress to warrant clinical intervention, between 51% and 80% were not psychologically distressed and were satisfied with their families. Data supported previous reports suggesting caregivers are “not universally distressed.”15

Manskow and colleagues followed patients with severe TBI and assessed caregiver burden 1 year later. Using the Caregiver Burden Scale, caregivers reported the highest scores (N = 92) on the General Strain Index followed by the Disappointment Index.16 Bayen and colleagues also studied caregivers of severe TBI patients.17 Objective and subjective caregiver burden data 4 years later indicated 44% of caregivers (N = 98) reported multidimensional burden. Greater burden was associated in caring for individuals who had poorer Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended scores and more severe cognitive disorders.

Military and Veteran Literature

Griffin and colleagues conducted the Family and Caregiver Experience Study (FACES) with caregivers (N = 564) of service members who incurred a TBI.3 According to the caregivers, two-thirds of the patients lost consciousness for more than 30 minutes, which was followed by inpatient rehabilitation care at a VA polytrauma center between 2001 and 2009. The majority of caregivers of TBI patients were female (79%) and aged < 60 years (84%). Parents comprised 62% and spouses 32% of the cohort. Caregivers tended to have some level of education beyond high school (73%), were married (77%), either worked or were enrolled in school (55%), and earned less than $40,000 a year (70%). Common characteristics of the care receivers were male gender (95%), average age 30, high school educated (52%), married (almost 50%), and employed (50%). Forty-five percent of the care receivers were injured 4 to 6 years prior, and 12% were injured 7 or more years prior. The study determined the caregivers’ perception of intensity of care needed and indicated that families as well as clinicians need to plan for some level of long-term support and services.

In addition to the TBI-related caregiving needs, Griffin and colleagues found in a military population that other medical conditions impacted the level of caregiving and strained a marriage.18 Their study found that in a military population between 30% and 50% of marriages of patients with TBI dissolved within the first 10 years after injury. Caregivers may need to learn nursing activities, such as tube feedings, tracheostomy and stoma care, catheter care, wound care, and medication administration. Family stress with caregiving may interfere with the ability to understand information related to the care receivers’ medical care and may require multiple formats to explain care needs. Sander and colleagues associated better emotional functioning in caregivers with greater social integration and occupation outcomes in patients at the postacute rehabilitation program phase (within 6 months of injury).19 However, these outcomes did not continue more than 6 months postinjury.

Intervention and Research Studies

Powell and colleagues used a telephone-based, individualized TBI education intervention along with problem-solving mentoring (10 phone calls at 2-week intervals following patient discharge for moderate-to-severe TBI from a level 1 trauma center) to determine which programs, activities, and coping strategies could decrease caregiver challenges.20 The telephone interventions resulted in better caregiver outcomes than usual care as measured by composite scores on the Bakas Caregiving Outcomes Scale (BCOS) and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18) at 6 months post-TBI survivor discharge. Dyer and colleagues explored Internet approaches and mobile applications to provide support for caregivers. 18 In a small sample of 10 caregivers, Damianakis and colleagues conducted a 10-session pilot videoconferencing support-group intervention program led by a clinician. Results indicated that the intervention enhanced caregiver coping and problem-solving skills.7

Petranovich and colleagues examined the efficacy of counselor-assisted problem-solving interventions in improving long-term caregiver psychological functioning following TBI in adolescents.21 Their findings support the utility of online interventions in improving long-term caregiver psychological distress, particularly for lower income families. Although this study focused on adolescents, research may indicate merit in an adult population. In relatives of patients with severe TBI, Norup and colleagues associated improvements in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) with improvements in symptoms of anxiety and depression without specific intervention.22

Moriarty and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial for veterans who received care at a VA polytrauma center and their family members who participated in a veteran’s in-home program (VIP) intervention.9 The study aimed to evaluate how VIP affected family members’ caregiver burden, depressive symptoms, satisfaction with caregiving, and the program’s acceptability. Eighty-one veterans with a key family member were randomized. Of those, 63 veterans completed a follow-up interview. The intervention consisted of 6 home visits of 1 to 2 hours each and 2 telephone calls from an occupational therapist over 3 to 4 months. Family members were invited to participate during the home visits. The control group received usual clinic care with 2 telephone calls during the study period. All participants received the follow-up interview 3 to 4 months after baseline interviews. The severity of TBI was determined by a review of the electronic medical record using the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines. Findings of this study indicated that family members in the intervention group showed significantly lower depressive symptom scores and caregiver burden scores.9 Additionally, the veterans in the intervention group exhibited higher community integration and ability to manage their targeted outcomes. Further research may indicate that VIP could assist patients with TBI and caregivers in an active-duty population.

The DVBIC is the executive agent for a congressionally mandated 15-year longitudinal study on TBI incurred by members of the armed services in OEF and OIF. The John Warner National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2007 outlined the study. An initial finding identified the need for an HRQOL outcomes assessment specific to TBI caregivers.23 Having these data will allow investigators to fully determine the comprehensive impact of caring for a person who sustained a mild, moderate, severe, or penetrating TBI and to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to address caregivers’ needs. To date, the study has identified the following HRQOL themes generated among caregivers: social health, emotional health, physical/medical health, cognitive functioning, and feelings of loss (related to changing social roles). Carlozzi and colleagues noted that the study also aimed to identify a sensitive outcome measure to evaluate quality of life in the caregivers over time.7

Knowledge Gaps

Ongoing studies focus on caregiving for individuals with various illnesses and needs. Some of the information in each study may be beneficial to TBI caregivers who are not fully aware of resources and interventions. For example, Fortune and colleagues, Hirano and colleagues, and Grover and colleagues are studying caregiver activities involving other diseases to determine, more generally, which programs, activities, and coping strategies can decrease caregiver challenges.24-26 Further, understanding and addressing the needs of these families over many years will provide data that could inform policy, benefits, resources, and needed services (such as the Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010) and assist with family resilience efforts, including understanding and enhancing family protective and recovery factors.

As studies have indicated, some families do not report family distress when providing care to an individual with TBI. Understanding the factors that influence positive family adjustment is important to capture and perhaps replicate in future studies so that they can lead to effective treatment interventions. Although this review does not discuss caregiver needs for patients with TBI with disorders of consciousness that require more care than most caregivers can provide in the home setting, caregiving for this population deserves attention in future studies. Furthermore, an area that has not received much attention is the impact on children in the household. Children aged < 18 years can assist not only in the care of a disabled adult, but also of younger siblings; also they can help with household activities from housekeeping to meal preparation. Children also may provide physical and emotional support.

The impact of aging caregivers and subsequent needs for their own care as well as the person(s) they are providing care for has not been fully addressed. Areas requiring more research include both the aging caregiver taking care of an aging spouse or relative and the aging parent taking care of a young adult or child. Along with aging, the issue of long-term caregiving needs further development. For example, how do the differences between access to services between caregivers of adults with TBI in the military and those in the civilian sector impact the family/caregiver? Further research may answer questions such as:

- Which tools are most useful in evaluating and determining caregiver stress and burden?

- Are the needs of military and veteran caregivers unique?

- Do polytrauma patients with comorbid diagnoses have unique caregiver needs and trajectories?

- Do TBI caregiver stressors differ from stressors related to other medical conditions or chronic diseases?

- Is there a need for military and veteran TBI-specific caregiver programs?

- Which interventions best help caregivers and for how long?

- Should the approach to intervention depend on variables such as age and gender of the caregivers or relationship to the patient with a TBI (eg, spouse vs parent)?

Methods or processes to inform and update caregivers about available resources also are critically needed. Also, Sabab and colleagues noted the importance of research on the effects of denial as it relates to cognitive, emotional, social impact.27 Denial may impact delays in treatments.

Resource

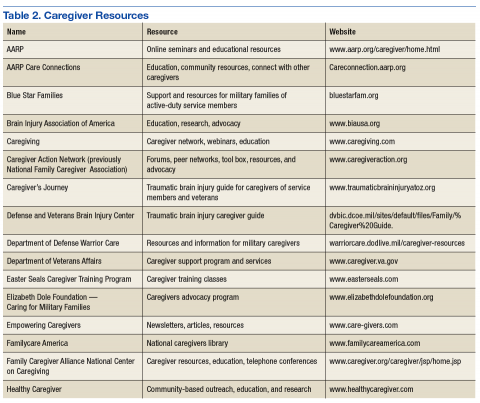

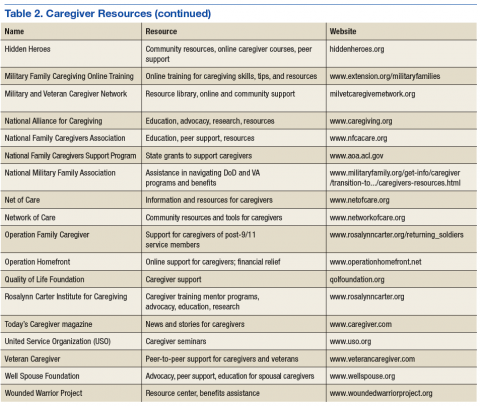

Many national, state, local, and grassroots organizations provide information and support for persons with illness and/or disabilities. Most clinicians of neurologic, mental health, and cancer have developed various forms of support interventions for those with the disease and their caregivers (Table 2). Highlighted in this section are a few organizations that specifically provide resources for caregivers caring for active-duty service members or veterans with a TBI.

Although a caregiver generally does not receive money from an outside source for services, the DoD may consider the caregiver as a nonmedical attendant for an active-duty service member and provide a temporary stipend. The VA provides several support and service options for caregivers under the Caregiver Support Program, through which more than 300 VA health care professionals provide support to caregivers. The Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010 authorizes the VA to provide additional VA services for seriously injured post-9/11 veterans and their family caregivers through the Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (VA Caregiver Support Program). After meeting eligibility criteria, primary caregivers of post-9/11 veterans may receive a monthly stipend (based on the level of care needed) as well as comprehensive caregiver training, referral services, access to health care insurance, mental health services, counseling, and respite care. The Caregiver Support Program offers a toll-free support line and a 24-hour crisis hot line.

In 2014, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) outlined the VA health care improvements needed to manage the demand for the Caregiver Support Program, which are established at VA medical centers.28 The GAO reported that the “VA significantly underestimated caregivers’ demand for services… larger than expected workloads and …delays in approval determinations” with about 500 approved caregivers who are added to the program each month. Original estimates indicated that about 4,000 caregivers would be approved by September 2014; however, by May 2014 about 15,600 caregivers were approved.

In addition to the VA Caregiver Support Program, a variety of state, local, and nonprofit organizations offer support for caregivers. Established in 2012, the Elizabeth Dole Foundation’s program Caring for Military Families “assists caregivers by raising awareness of the caregiver role, leveraging resources and partnerships to provide support, and identifying best practices and solutions to address the challenges caregivers face.” The foundation commissioned the RAND Corporation to “describe the magnitude of military caregiving in the United States, and to identify gaps in programs, policies, and services.” The 2014 RAND report estimated that among the 5.5 million military caregivers in the U.S., 1 million (19.6%) cared for post-9/11 veterans.29 The military caregivers consistently experienced poorer health outcomes, greater strains on family relationships, and more workplace problems than noncaregivers; post-9/11 military caregivers fared worse in those areas.

The Elizabeth Dole Foundation, Hidden Heroes Impact Council Forum advocates for caregiver empowerment, cultural competency awareness, and better policies, programs, and services. The council focuses its efforts on key impact: community support at home, education and training, employment and workplace support, financial and legal issues, interfaith action and ministry council, mental and physical health, and respite care. It aims to raise the money to build awareness and support for military and veterans’ caregivers. The Military and Veteran Caregiver Network is another Elizabeth Dole Foundation initiative. It is an online forum community, peer support group, and peer mentor program structure. A resource library for referrals to local services also is available.

A variety of other organizations, such as United Service Organizations; Easter Seals; Team Red, White and Blue; Operation Homefront; Blue Star Families; state Brain Injury Associations; and support groups for TBI at local hospitals and community centers provide resources to both patients and caregivers. Organizations for caregivers not exclusive to TBI patients include the Caregiver Action Network (formerly National Family Caregiver Association) and the Family Caregiver Alliance. The National Family Caregivers Support Program provides grants to states and territories to develop and provide supportive services to caregivers. Some training for caregivers could include long-term financial planning, legal issues, residential and educational planning, caregiver stress management, the benefits of utilizing support resources, and actions and behaviors that enhance coping strategies. In 2007, DVBIC developed The Traumatic Brain Injury Guide for Caregivers of Service Members and Veterans, which is intended for family caregivers assisting a service member or veteran who sustained a moderate or severe TBI.6 A recent assessment determined the need to update the guide. The Center of Excellence for Medical Multimedia is another source of information for caregivers.

Conclusion

The recent combat conflicts of OEF and OIF have resulted in a dramatic increase in the occurrence of TBI injuries in active-duty service members both in theater and stateside and have highlighted the need for some service members and veterans with a TBI to require ongoing assistance from a caregiver. The levels of assistance and length of time vary greatly, impacted by the severity of the TBI and psychosocial situations.

In response to elevated awareness, several programs and resources have been developed or enhanced to address the specific needs of caregivers. Certain programs and resources are specific for caregivers of military service members and veterans, whereas others benefit caregivers in general. Likewise, some programs are not specific to individuals with TBI.

Caregivers assume many roles in their efforts to support the person with a TBI. They may need to dramatically adjust their lives to serve as a caregiver. Providing adequate resources for the caregivers impacts their ability to continue providing care. Thus, awareness of and access to resources play a critical role in helping to reduce stress, distress, burden (eg, physical, emotional, and financial), and caregiver burnout. Programs and resources often change, making it difficult for health care practitioners to know which programs offer what or even whether they still exist. Therefore, the authors synthesized the current medical literature of the topic of TBI and their caregiver needs as well as current resources for additional information and support.

Ongoing research studies, such as the congressionally mandated 15-year longitudinal study, are examining the impact of caregiving in the military and veteran communities. Future research could identify specific needs of military caregivers, identify gaps in services or programs, and identify interventions that promote resilience. Moreover, research directed at military and veteran caregivers can promote change that will benefit the general population of caregivers. It will be important for health care practitioners to keep abreast of new findings and information to incorporate into care plans for their patients who have had a TBI and their families.

1. Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. DoD worldwide numbers for TBI. http://dvbic.dcoe.mil/dod-worldwide-numbers-tbi. Updated October 5, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2017.

2. Perry DC, Sturm VE, Peterson MJ, et al. Association of traumatic brain injury with subsequent neurological and psychiatric disease: a meta-analysis. J Neurosurg. 2016;124(2):511-526.

3. Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. Traumatic brain injury: a guide for caregivers of service members and veterans. https://dvbic.dcoe.mil /sites/default/files/Family%20Caregiver%20Guide.All%20Modules_updated.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2017

4. Griffin JM, Friedemann-Sánchez G, Jensen AC, et al. The invisible side of war: families caring for US service members with traumatic brain injuries and polytrauma. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2012;27(1):3-13.

5. Lou VW, Kwan CW, Chong ML, Chi I. Associations between secondary caregivers’ supportive behavior and psychological distress of primary spousal caregivers of cognitively intact and impaired elders. Gerontologist. 2015;55(4):584-594.

6. Carlozzi NE, Kratz AL, Sander AM, et al. Health-related quality of life in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury: development of a conceptual model. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(1):105-113.

7. Damianakis T, Tough A, Marziali E, Dawson DR. Therapy online: a web-based video support group for family caregivers of survivors with traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016;31(4):E12-E20.

8. Dyer EA, Kansagara D, McInnes DK, Freeman M, Woods, S. Mobile applications and internet-based approaches for supporting non-professional caregivers: a systematic review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0050675. Accessed October 10, 2017.

9. Moriarty H, Winter L, Robinson K, et al. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the veterans’ in-home program for military veterans with traumatic brain injury and their families: report on impact for family members. PMR. 2016;8(6):495-509.

10. Anderson MI, Simpson GK, Daher M, Matheson L. Chapter 7 the relationship between coping and psychological adjustment in family caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2015;33:219-247.

11. Van Houtven CH, Friedemann-Sanchez G, Clothier B, et al. Is policy well-targeted to remedy financial strain among caregivers of severely injured U.S. service members? Inquiry. 2012-2013;49(4):339-351.

12. Kratz AL, Sander AM, Brickell TA, Lange RT, Carlozzi NE. Traumatic brain injury caregivers: a qualitative analysis of spouse and parent perspectives on quality of life. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2017;27(1):16-37.13. Verhasghe S, Defloor T, Grypdonck M. Stress and coping among families of patients with traumatic brain injury: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(8):1004-1012.

14. Ennis N, Rosenbloom BN, Canzian S, Topolovec-Vranic J. Depression and anxiety in parent versus spouse caregivers of adult patients with traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2013;23(1):1-18.

15. Perlesz A, Kinsella G, Crowe S. Psychological distress and family satisfaction following traumatic brain injury: injured individuals and their primary, secondary, and tertiary carers. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2000;15(3):909-929.

16. Manskow US, Sigurdardottir S, Røe C, et al. Factors affecting caregiving burden 1 year after severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective nationwide multicenter study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30(6):411-423.

17. Bayen E, Jourdan C, Ghout I, et al. Objective and subjective burden of informal caregivers 4 years after a severe traumatic brain injury: results from the Paris-TBI study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016;31(5):E59-E67.

18. Griffin JM, Friedemann-Sanchez G, Hall C, Phelan S, van Ryn M. Families of patients with polytrauma: understanding the evidence and charting a new research agenda. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(6):879-892.

19. Sander AM, Maestas KL, Sherer M, Malac JF, Nakase-Richardson R. Relationship of caregiver and family functioning to participation outcomes after post-acute rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury: a multicenter investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(5):842-848.

20. Powell JM, Fraser R, Brockway JA, Temkin N, Bell KR. A telehealth approach to caregiver self-management following traumatic brain injury: a randomized control trial. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;31(3):180-190.

21. Petranovich CL, Wade SL, Taylor HG, et al. Long-term caregiver mental health outcomes following a predominately online intervention for adolescents with complicated mild to severe traumatic brain injury. J Pediatr Psychol, 2015;40(7):680-688.

22. Norup A, Kristensen KS, Poulsen I, Mortensen EL. Evaluating clinically significant changes in health-related quality of life: a sample of relatives of patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2017;27(2):196-215.

23. John Warner National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2007, HR 5122, 109th Cong, 2nd Sess (2006).

24. Fortune DG, Rogan CR, Richards HL. A structured multicomponent group program for carers of people with acquired brain injury: effects on perceived criticism, strain, and psychological distress. Br J Health Psychol. 2016;21(1):224-243.

25. Hirano A, Umegaki H, Suzuki Y, Hayashi T, Kuzuya M. Effects of leisure activities at home on perceived care burden and the endocrine system of caregivers of dementia patients: a randomized controlled study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(2):261-268.

26. Grover S, Pradyumna, Chakrabarti S. Coping among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Ind Psychiatry J. 2015;24(1):5-11.

27. Saban KL, Hogan NS, Hogan TP, Pape TL. He looks normal but…challenges of family caregivers of veterans diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury. Rehabil Nurs. 2015;40(5):277-285.

28. Williamson RB; United States Government Accountability Office. VA health care improvements needed to manage higher-than-expected demand for the family caregiver program. http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/667275.pdf. Published December 3, 2014. Accessed October 10, 2017.

29. Ramchand R, Tanielian T, Fisher MP, et al. Hidden heroes America’s military caregivers. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR400/RR499/RAND_RR499.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed October 10, 2017.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a health concern for the U.S. Military Health System (MHS) as well as the VHA. It occurs in both deployed and nondeployed settings; however, Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and improved reporting mechanisms have dramatically increased TBI diagnoses in active-duty service members. According to the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC), more than 370,000 service members have been diagnosed with a TBI since 2000 (Figure).1

Background

The DoD and the VA are collaborating on clinical research studies to identify, understand, and treat the long-term effects of TBI that can affect patients and their families. Most TBIs are mild (mTBIs), also called concussions, and patients typically recover within a few weeks (Table 1). However, some individuals with mTBI experience symptoms that may persist for months or years. A meta-analysis by Perry and colleagues showed that the prevalence or risk of a neurologic disorder, depression, or other mental health issue following mTBI was 67% higher compared with that in uninjured controls.2

Patients with any severity of TBI may require assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), such as bathing, dressing, managing medications, and feeding. Patients also may need help with instrumental ADLs, such as meal preparation, grocery shopping, household chores, child care, getting to appointments or activities, coordination of educational and vocational services, financial and benefits management, and supportive listening.

Increased injuries have spurred the DoD and VA to coordinate health care to provide a seamless transition for patients between the 2 agencies. However, individuals who sustained a TBI may need various levels of caregiver assistance over time.

TBI and Caregivers

Despite better agency coordination for patients, caregivers can experience stress. Griffin and colleagues found that caregiving responsibilities can compete with other demands on the caregiver, such as work and family, and may negatively impact their health and finances.3,4

Lou and colleagues studied the factors associated with caring for chronically ill family members that may result in stress for the caregivers.5 Along with an unaccounted for economic contribution, caregivers may face lost work time and pay and limitations on work travel and work advancement. Additionally, lost time for leisure, travel, social activities, family obligations, and retirement could result in physical and mental drain on the caregiver. Stress may reach a level at which the caregivers risk psychological distress. The study also noted that families with perceived high stress experience disrupted family functioning. Some TBI caregiver studies sought to understand how best to evaluate and determine the level of caregiver burden, and other studies investigated appropriate interventions.6-9

Health care practitioners within the federal health care system may benefit from a greater awareness of caregiver needs and caregiver resources. Caregiver support can improve outcomes for both the caregiver and care recipient, and many organizations and resources already exist to assist the caregiver. This article reviews recent published literature on TBI caregivers of patients with TBI across civilian, military, and veteran populations and lists caregiver resources for additional information, assistance, and support.

Literature Review

The DVBIC defines the term caregiver as “any family or support person(s) relied upon by the service member or veteran with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who assumes primary responsibility for ensuring the needed level of care and overall well-being of that service member or veteran. A family or family caregiver may include spouse, parents, children, other extended family members, as well as significant others and friends.”3

In the following discussion, findings from military and veteran literature are separated from civilian population findings to highlight similarities and differences between these 2 bodies of research. Several of the studies in the military/veteran cohorts include polytrauma patients with comorbid physical and mental health issues not necessarily found in civilian literature.

Civilian Literature

A 2015 systematic review by Anderson and colleagues on coping and psychological adjustment in TBI caregivers indicated no Class I or Class II studies.10 Four Class III and 3 Class IV studies were found. The authors suggest that more rigorous studies (ie, Class I and II) are needed.

Despite these limitations, peer-reviewed literature indicates that the levels of stress and distress in TBI caregivers are consistent with reports for other diseases. In a civilian population, Carlozzi and colleagues found that TBI caregivers who reported stress, distress, anxiety, and feeling overwhelmed often had concerns for their social, emotional, physical, cognitive health, as well as feelings of loss.5 In addition, caregivers may need to take leaves of absence or leave the workforce entirely to provide for a family member or friend who had a TBI—often leading to financial strain (eg, depleting assets, accumulating debt). These challenges may occur during prime earning years, and the caregiver may lose the ability to resume work if the care receiver requires care for extended periods.11

Kratz and colleagues showed that caregivers of individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI: (1) felt overburdened with responsibilities; (2) lacked personal time and time for self-care; (3) felt their lives were interrupted or lost; (4) grieved the loss of the person with TBI; and (5) endorsed anger, guilt, anxiety, and sadness.12

Perceptions differed between caregiver parents and caregiver partners. Parents expressed feelings of grief and sadness related to the “loss of the person before the TBI.” Parents also reported a sense of guilt and responsibility for their child’s TBI and feelings of being tied down to the individual with TBI. Parents experienced a greater level of stress if the son or daughter with TBI still lived at home. Partners expressed frustration and despair related to their role as sole decision maker and care provider. Partners’ distress also related to the partner relationship and the relationship between children and the individual with TBI.

Verhasghe and colleagues found that partners experience a greater degree of stress than do parents.13 Young families with minimal social support for coping with financial, psychiatric, and medical problems were the most vulnerable to stress. A systematic review by Ennis and colleagues evaluated depression and anxiety in caregiver parents vs spouses.14 Although methods and quality differed in the studies, findings indicated high levels of distress regardless of the type of caregiver.

Anderson and colleagues used the Ways of Coping Questionnaire to evaluate the association between coping and psychological adjustment in caregivers of TBI individuals.10 The use of emotion-focused coping and problem solving was possibly associated with psychological adjustment in caregivers. Verhasghe and colleagues indicated that the nature of the injuries more than the severity of TBI determined the level of stress up to 15 years after the TBI.13 Gender and social and professional support also influenced coping. The review identified the need to develop models of long-term support and care.

An Australian cohort of 79 family caregivers participated in a study by Perlesz and colleagues.15 Participants’ caregiving responsibilities averaged 19.3 months posttrauma. The Family Satisfaction Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, State Anxiety Inventory, and Profile of Mood States were used in this analysis. Male caregivers reported distress in terms of anger and fatigue; female caregivers were at greatest risk of poor psychosocial outcomes. Although findings from primary caregivers indicated that 35% to 49% displayed enough distress to warrant clinical intervention, between 51% and 80% were not psychologically distressed and were satisfied with their families. Data supported previous reports suggesting caregivers are “not universally distressed.”15

Manskow and colleagues followed patients with severe TBI and assessed caregiver burden 1 year later. Using the Caregiver Burden Scale, caregivers reported the highest scores (N = 92) on the General Strain Index followed by the Disappointment Index.16 Bayen and colleagues also studied caregivers of severe TBI patients.17 Objective and subjective caregiver burden data 4 years later indicated 44% of caregivers (N = 98) reported multidimensional burden. Greater burden was associated in caring for individuals who had poorer Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended scores and more severe cognitive disorders.

Military and Veteran Literature

Griffin and colleagues conducted the Family and Caregiver Experience Study (FACES) with caregivers (N = 564) of service members who incurred a TBI.3 According to the caregivers, two-thirds of the patients lost consciousness for more than 30 minutes, which was followed by inpatient rehabilitation care at a VA polytrauma center between 2001 and 2009. The majority of caregivers of TBI patients were female (79%) and aged < 60 years (84%). Parents comprised 62% and spouses 32% of the cohort. Caregivers tended to have some level of education beyond high school (73%), were married (77%), either worked or were enrolled in school (55%), and earned less than $40,000 a year (70%). Common characteristics of the care receivers were male gender (95%), average age 30, high school educated (52%), married (almost 50%), and employed (50%). Forty-five percent of the care receivers were injured 4 to 6 years prior, and 12% were injured 7 or more years prior. The study determined the caregivers’ perception of intensity of care needed and indicated that families as well as clinicians need to plan for some level of long-term support and services.

In addition to the TBI-related caregiving needs, Griffin and colleagues found in a military population that other medical conditions impacted the level of caregiving and strained a marriage.18 Their study found that in a military population between 30% and 50% of marriages of patients with TBI dissolved within the first 10 years after injury. Caregivers may need to learn nursing activities, such as tube feedings, tracheostomy and stoma care, catheter care, wound care, and medication administration. Family stress with caregiving may interfere with the ability to understand information related to the care receivers’ medical care and may require multiple formats to explain care needs. Sander and colleagues associated better emotional functioning in caregivers with greater social integration and occupation outcomes in patients at the postacute rehabilitation program phase (within 6 months of injury).19 However, these outcomes did not continue more than 6 months postinjury.

Intervention and Research Studies

Powell and colleagues used a telephone-based, individualized TBI education intervention along with problem-solving mentoring (10 phone calls at 2-week intervals following patient discharge for moderate-to-severe TBI from a level 1 trauma center) to determine which programs, activities, and coping strategies could decrease caregiver challenges.20 The telephone interventions resulted in better caregiver outcomes than usual care as measured by composite scores on the Bakas Caregiving Outcomes Scale (BCOS) and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18) at 6 months post-TBI survivor discharge. Dyer and colleagues explored Internet approaches and mobile applications to provide support for caregivers. 18 In a small sample of 10 caregivers, Damianakis and colleagues conducted a 10-session pilot videoconferencing support-group intervention program led by a clinician. Results indicated that the intervention enhanced caregiver coping and problem-solving skills.7

Petranovich and colleagues examined the efficacy of counselor-assisted problem-solving interventions in improving long-term caregiver psychological functioning following TBI in adolescents.21 Their findings support the utility of online interventions in improving long-term caregiver psychological distress, particularly for lower income families. Although this study focused on adolescents, research may indicate merit in an adult population. In relatives of patients with severe TBI, Norup and colleagues associated improvements in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) with improvements in symptoms of anxiety and depression without specific intervention.22

Moriarty and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial for veterans who received care at a VA polytrauma center and their family members who participated in a veteran’s in-home program (VIP) intervention.9 The study aimed to evaluate how VIP affected family members’ caregiver burden, depressive symptoms, satisfaction with caregiving, and the program’s acceptability. Eighty-one veterans with a key family member were randomized. Of those, 63 veterans completed a follow-up interview. The intervention consisted of 6 home visits of 1 to 2 hours each and 2 telephone calls from an occupational therapist over 3 to 4 months. Family members were invited to participate during the home visits. The control group received usual clinic care with 2 telephone calls during the study period. All participants received the follow-up interview 3 to 4 months after baseline interviews. The severity of TBI was determined by a review of the electronic medical record using the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines. Findings of this study indicated that family members in the intervention group showed significantly lower depressive symptom scores and caregiver burden scores.9 Additionally, the veterans in the intervention group exhibited higher community integration and ability to manage their targeted outcomes. Further research may indicate that VIP could assist patients with TBI and caregivers in an active-duty population.

The DVBIC is the executive agent for a congressionally mandated 15-year longitudinal study on TBI incurred by members of the armed services in OEF and OIF. The John Warner National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2007 outlined the study. An initial finding identified the need for an HRQOL outcomes assessment specific to TBI caregivers.23 Having these data will allow investigators to fully determine the comprehensive impact of caring for a person who sustained a mild, moderate, severe, or penetrating TBI and to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to address caregivers’ needs. To date, the study has identified the following HRQOL themes generated among caregivers: social health, emotional health, physical/medical health, cognitive functioning, and feelings of loss (related to changing social roles). Carlozzi and colleagues noted that the study also aimed to identify a sensitive outcome measure to evaluate quality of life in the caregivers over time.7

Knowledge Gaps

Ongoing studies focus on caregiving for individuals with various illnesses and needs. Some of the information in each study may be beneficial to TBI caregivers who are not fully aware of resources and interventions. For example, Fortune and colleagues, Hirano and colleagues, and Grover and colleagues are studying caregiver activities involving other diseases to determine, more generally, which programs, activities, and coping strategies can decrease caregiver challenges.24-26 Further, understanding and addressing the needs of these families over many years will provide data that could inform policy, benefits, resources, and needed services (such as the Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010) and assist with family resilience efforts, including understanding and enhancing family protective and recovery factors.

As studies have indicated, some families do not report family distress when providing care to an individual with TBI. Understanding the factors that influence positive family adjustment is important to capture and perhaps replicate in future studies so that they can lead to effective treatment interventions. Although this review does not discuss caregiver needs for patients with TBI with disorders of consciousness that require more care than most caregivers can provide in the home setting, caregiving for this population deserves attention in future studies. Furthermore, an area that has not received much attention is the impact on children in the household. Children aged < 18 years can assist not only in the care of a disabled adult, but also of younger siblings; also they can help with household activities from housekeeping to meal preparation. Children also may provide physical and emotional support.

The impact of aging caregivers and subsequent needs for their own care as well as the person(s) they are providing care for has not been fully addressed. Areas requiring more research include both the aging caregiver taking care of an aging spouse or relative and the aging parent taking care of a young adult or child. Along with aging, the issue of long-term caregiving needs further development. For example, how do the differences between access to services between caregivers of adults with TBI in the military and those in the civilian sector impact the family/caregiver? Further research may answer questions such as:

- Which tools are most useful in evaluating and determining caregiver stress and burden?

- Are the needs of military and veteran caregivers unique?

- Do polytrauma patients with comorbid diagnoses have unique caregiver needs and trajectories?

- Do TBI caregiver stressors differ from stressors related to other medical conditions or chronic diseases?

- Is there a need for military and veteran TBI-specific caregiver programs?

- Which interventions best help caregivers and for how long?

- Should the approach to intervention depend on variables such as age and gender of the caregivers or relationship to the patient with a TBI (eg, spouse vs parent)?

Methods or processes to inform and update caregivers about available resources also are critically needed. Also, Sabab and colleagues noted the importance of research on the effects of denial as it relates to cognitive, emotional, social impact.27 Denial may impact delays in treatments.

Resource

Many national, state, local, and grassroots organizations provide information and support for persons with illness and/or disabilities. Most clinicians of neurologic, mental health, and cancer have developed various forms of support interventions for those with the disease and their caregivers (Table 2). Highlighted in this section are a few organizations that specifically provide resources for caregivers caring for active-duty service members or veterans with a TBI.

Although a caregiver generally does not receive money from an outside source for services, the DoD may consider the caregiver as a nonmedical attendant for an active-duty service member and provide a temporary stipend. The VA provides several support and service options for caregivers under the Caregiver Support Program, through which more than 300 VA health care professionals provide support to caregivers. The Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010 authorizes the VA to provide additional VA services for seriously injured post-9/11 veterans and their family caregivers through the Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (VA Caregiver Support Program). After meeting eligibility criteria, primary caregivers of post-9/11 veterans may receive a monthly stipend (based on the level of care needed) as well as comprehensive caregiver training, referral services, access to health care insurance, mental health services, counseling, and respite care. The Caregiver Support Program offers a toll-free support line and a 24-hour crisis hot line.

In 2014, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) outlined the VA health care improvements needed to manage the demand for the Caregiver Support Program, which are established at VA medical centers.28 The GAO reported that the “VA significantly underestimated caregivers’ demand for services… larger than expected workloads and …delays in approval determinations” with about 500 approved caregivers who are added to the program each month. Original estimates indicated that about 4,000 caregivers would be approved by September 2014; however, by May 2014 about 15,600 caregivers were approved.

In addition to the VA Caregiver Support Program, a variety of state, local, and nonprofit organizations offer support for caregivers. Established in 2012, the Elizabeth Dole Foundation’s program Caring for Military Families “assists caregivers by raising awareness of the caregiver role, leveraging resources and partnerships to provide support, and identifying best practices and solutions to address the challenges caregivers face.” The foundation commissioned the RAND Corporation to “describe the magnitude of military caregiving in the United States, and to identify gaps in programs, policies, and services.” The 2014 RAND report estimated that among the 5.5 million military caregivers in the U.S., 1 million (19.6%) cared for post-9/11 veterans.29 The military caregivers consistently experienced poorer health outcomes, greater strains on family relationships, and more workplace problems than noncaregivers; post-9/11 military caregivers fared worse in those areas.

The Elizabeth Dole Foundation, Hidden Heroes Impact Council Forum advocates for caregiver empowerment, cultural competency awareness, and better policies, programs, and services. The council focuses its efforts on key impact: community support at home, education and training, employment and workplace support, financial and legal issues, interfaith action and ministry council, mental and physical health, and respite care. It aims to raise the money to build awareness and support for military and veterans’ caregivers. The Military and Veteran Caregiver Network is another Elizabeth Dole Foundation initiative. It is an online forum community, peer support group, and peer mentor program structure. A resource library for referrals to local services also is available.

A variety of other organizations, such as United Service Organizations; Easter Seals; Team Red, White and Blue; Operation Homefront; Blue Star Families; state Brain Injury Associations; and support groups for TBI at local hospitals and community centers provide resources to both patients and caregivers. Organizations for caregivers not exclusive to TBI patients include the Caregiver Action Network (formerly National Family Caregiver Association) and the Family Caregiver Alliance. The National Family Caregivers Support Program provides grants to states and territories to develop and provide supportive services to caregivers. Some training for caregivers could include long-term financial planning, legal issues, residential and educational planning, caregiver stress management, the benefits of utilizing support resources, and actions and behaviors that enhance coping strategies. In 2007, DVBIC developed The Traumatic Brain Injury Guide for Caregivers of Service Members and Veterans, which is intended for family caregivers assisting a service member or veteran who sustained a moderate or severe TBI.6 A recent assessment determined the need to update the guide. The Center of Excellence for Medical Multimedia is another source of information for caregivers.

Conclusion

The recent combat conflicts of OEF and OIF have resulted in a dramatic increase in the occurrence of TBI injuries in active-duty service members both in theater and stateside and have highlighted the need for some service members and veterans with a TBI to require ongoing assistance from a caregiver. The levels of assistance and length of time vary greatly, impacted by the severity of the TBI and psychosocial situations.

In response to elevated awareness, several programs and resources have been developed or enhanced to address the specific needs of caregivers. Certain programs and resources are specific for caregivers of military service members and veterans, whereas others benefit caregivers in general. Likewise, some programs are not specific to individuals with TBI.

Caregivers assume many roles in their efforts to support the person with a TBI. They may need to dramatically adjust their lives to serve as a caregiver. Providing adequate resources for the caregivers impacts their ability to continue providing care. Thus, awareness of and access to resources play a critical role in helping to reduce stress, distress, burden (eg, physical, emotional, and financial), and caregiver burnout. Programs and resources often change, making it difficult for health care practitioners to know which programs offer what or even whether they still exist. Therefore, the authors synthesized the current medical literature of the topic of TBI and their caregiver needs as well as current resources for additional information and support.

Ongoing research studies, such as the congressionally mandated 15-year longitudinal study, are examining the impact of caregiving in the military and veteran communities. Future research could identify specific needs of military caregivers, identify gaps in services or programs, and identify interventions that promote resilience. Moreover, research directed at military and veteran caregivers can promote change that will benefit the general population of caregivers. It will be important for health care practitioners to keep abreast of new findings and information to incorporate into care plans for their patients who have had a TBI and their families.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a health concern for the U.S. Military Health System (MHS) as well as the VHA. It occurs in both deployed and nondeployed settings; however, Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and improved reporting mechanisms have dramatically increased TBI diagnoses in active-duty service members. According to the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC), more than 370,000 service members have been diagnosed with a TBI since 2000 (Figure).1

Background

The DoD and the VA are collaborating on clinical research studies to identify, understand, and treat the long-term effects of TBI that can affect patients and their families. Most TBIs are mild (mTBIs), also called concussions, and patients typically recover within a few weeks (Table 1). However, some individuals with mTBI experience symptoms that may persist for months or years. A meta-analysis by Perry and colleagues showed that the prevalence or risk of a neurologic disorder, depression, or other mental health issue following mTBI was 67% higher compared with that in uninjured controls.2

Patients with any severity of TBI may require assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), such as bathing, dressing, managing medications, and feeding. Patients also may need help with instrumental ADLs, such as meal preparation, grocery shopping, household chores, child care, getting to appointments or activities, coordination of educational and vocational services, financial and benefits management, and supportive listening.

Increased injuries have spurred the DoD and VA to coordinate health care to provide a seamless transition for patients between the 2 agencies. However, individuals who sustained a TBI may need various levels of caregiver assistance over time.

TBI and Caregivers

Despite better agency coordination for patients, caregivers can experience stress. Griffin and colleagues found that caregiving responsibilities can compete with other demands on the caregiver, such as work and family, and may negatively impact their health and finances.3,4

Lou and colleagues studied the factors associated with caring for chronically ill family members that may result in stress for the caregivers.5 Along with an unaccounted for economic contribution, caregivers may face lost work time and pay and limitations on work travel and work advancement. Additionally, lost time for leisure, travel, social activities, family obligations, and retirement could result in physical and mental drain on the caregiver. Stress may reach a level at which the caregivers risk psychological distress. The study also noted that families with perceived high stress experience disrupted family functioning. Some TBI caregiver studies sought to understand how best to evaluate and determine the level of caregiver burden, and other studies investigated appropriate interventions.6-9

Health care practitioners within the federal health care system may benefit from a greater awareness of caregiver needs and caregiver resources. Caregiver support can improve outcomes for both the caregiver and care recipient, and many organizations and resources already exist to assist the caregiver. This article reviews recent published literature on TBI caregivers of patients with TBI across civilian, military, and veteran populations and lists caregiver resources for additional information, assistance, and support.

Literature Review

The DVBIC defines the term caregiver as “any family or support person(s) relied upon by the service member or veteran with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who assumes primary responsibility for ensuring the needed level of care and overall well-being of that service member or veteran. A family or family caregiver may include spouse, parents, children, other extended family members, as well as significant others and friends.”3

In the following discussion, findings from military and veteran literature are separated from civilian population findings to highlight similarities and differences between these 2 bodies of research. Several of the studies in the military/veteran cohorts include polytrauma patients with comorbid physical and mental health issues not necessarily found in civilian literature.

Civilian Literature

A 2015 systematic review by Anderson and colleagues on coping and psychological adjustment in TBI caregivers indicated no Class I or Class II studies.10 Four Class III and 3 Class IV studies were found. The authors suggest that more rigorous studies (ie, Class I and II) are needed.

Despite these limitations, peer-reviewed literature indicates that the levels of stress and distress in TBI caregivers are consistent with reports for other diseases. In a civilian population, Carlozzi and colleagues found that TBI caregivers who reported stress, distress, anxiety, and feeling overwhelmed often had concerns for their social, emotional, physical, cognitive health, as well as feelings of loss.5 In addition, caregivers may need to take leaves of absence or leave the workforce entirely to provide for a family member or friend who had a TBI—often leading to financial strain (eg, depleting assets, accumulating debt). These challenges may occur during prime earning years, and the caregiver may lose the ability to resume work if the care receiver requires care for extended periods.11

Kratz and colleagues showed that caregivers of individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI: (1) felt overburdened with responsibilities; (2) lacked personal time and time for self-care; (3) felt their lives were interrupted or lost; (4) grieved the loss of the person with TBI; and (5) endorsed anger, guilt, anxiety, and sadness.12

Perceptions differed between caregiver parents and caregiver partners. Parents expressed feelings of grief and sadness related to the “loss of the person before the TBI.” Parents also reported a sense of guilt and responsibility for their child’s TBI and feelings of being tied down to the individual with TBI. Parents experienced a greater level of stress if the son or daughter with TBI still lived at home. Partners expressed frustration and despair related to their role as sole decision maker and care provider. Partners’ distress also related to the partner relationship and the relationship between children and the individual with TBI.

Verhasghe and colleagues found that partners experience a greater degree of stress than do parents.13 Young families with minimal social support for coping with financial, psychiatric, and medical problems were the most vulnerable to stress. A systematic review by Ennis and colleagues evaluated depression and anxiety in caregiver parents vs spouses.14 Although methods and quality differed in the studies, findings indicated high levels of distress regardless of the type of caregiver.

Anderson and colleagues used the Ways of Coping Questionnaire to evaluate the association between coping and psychological adjustment in caregivers of TBI individuals.10 The use of emotion-focused coping and problem solving was possibly associated with psychological adjustment in caregivers. Verhasghe and colleagues indicated that the nature of the injuries more than the severity of TBI determined the level of stress up to 15 years after the TBI.13 Gender and social and professional support also influenced coping. The review identified the need to develop models of long-term support and care.

An Australian cohort of 79 family caregivers participated in a study by Perlesz and colleagues.15 Participants’ caregiving responsibilities averaged 19.3 months posttrauma. The Family Satisfaction Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, State Anxiety Inventory, and Profile of Mood States were used in this analysis. Male caregivers reported distress in terms of anger and fatigue; female caregivers were at greatest risk of poor psychosocial outcomes. Although findings from primary caregivers indicated that 35% to 49% displayed enough distress to warrant clinical intervention, between 51% and 80% were not psychologically distressed and were satisfied with their families. Data supported previous reports suggesting caregivers are “not universally distressed.”15

Manskow and colleagues followed patients with severe TBI and assessed caregiver burden 1 year later. Using the Caregiver Burden Scale, caregivers reported the highest scores (N = 92) on the General Strain Index followed by the Disappointment Index.16 Bayen and colleagues also studied caregivers of severe TBI patients.17 Objective and subjective caregiver burden data 4 years later indicated 44% of caregivers (N = 98) reported multidimensional burden. Greater burden was associated in caring for individuals who had poorer Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended scores and more severe cognitive disorders.

Military and Veteran Literature

Griffin and colleagues conducted the Family and Caregiver Experience Study (FACES) with caregivers (N = 564) of service members who incurred a TBI.3 According to the caregivers, two-thirds of the patients lost consciousness for more than 30 minutes, which was followed by inpatient rehabilitation care at a VA polytrauma center between 2001 and 2009. The majority of caregivers of TBI patients were female (79%) and aged < 60 years (84%). Parents comprised 62% and spouses 32% of the cohort. Caregivers tended to have some level of education beyond high school (73%), were married (77%), either worked or were enrolled in school (55%), and earned less than $40,000 a year (70%). Common characteristics of the care receivers were male gender (95%), average age 30, high school educated (52%), married (almost 50%), and employed (50%). Forty-five percent of the care receivers were injured 4 to 6 years prior, and 12% were injured 7 or more years prior. The study determined the caregivers’ perception of intensity of care needed and indicated that families as well as clinicians need to plan for some level of long-term support and services.

In addition to the TBI-related caregiving needs, Griffin and colleagues found in a military population that other medical conditions impacted the level of caregiving and strained a marriage.18 Their study found that in a military population between 30% and 50% of marriages of patients with TBI dissolved within the first 10 years after injury. Caregivers may need to learn nursing activities, such as tube feedings, tracheostomy and stoma care, catheter care, wound care, and medication administration. Family stress with caregiving may interfere with the ability to understand information related to the care receivers’ medical care and may require multiple formats to explain care needs. Sander and colleagues associated better emotional functioning in caregivers with greater social integration and occupation outcomes in patients at the postacute rehabilitation program phase (within 6 months of injury).19 However, these outcomes did not continue more than 6 months postinjury.

Intervention and Research Studies

Powell and colleagues used a telephone-based, individualized TBI education intervention along with problem-solving mentoring (10 phone calls at 2-week intervals following patient discharge for moderate-to-severe TBI from a level 1 trauma center) to determine which programs, activities, and coping strategies could decrease caregiver challenges.20 The telephone interventions resulted in better caregiver outcomes than usual care as measured by composite scores on the Bakas Caregiving Outcomes Scale (BCOS) and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18) at 6 months post-TBI survivor discharge. Dyer and colleagues explored Internet approaches and mobile applications to provide support for caregivers. 18 In a small sample of 10 caregivers, Damianakis and colleagues conducted a 10-session pilot videoconferencing support-group intervention program led by a clinician. Results indicated that the intervention enhanced caregiver coping and problem-solving skills.7

Petranovich and colleagues examined the efficacy of counselor-assisted problem-solving interventions in improving long-term caregiver psychological functioning following TBI in adolescents.21 Their findings support the utility of online interventions in improving long-term caregiver psychological distress, particularly for lower income families. Although this study focused on adolescents, research may indicate merit in an adult population. In relatives of patients with severe TBI, Norup and colleagues associated improvements in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) with improvements in symptoms of anxiety and depression without specific intervention.22

Moriarty and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial for veterans who received care at a VA polytrauma center and their family members who participated in a veteran’s in-home program (VIP) intervention.9 The study aimed to evaluate how VIP affected family members’ caregiver burden, depressive symptoms, satisfaction with caregiving, and the program’s acceptability. Eighty-one veterans with a key family member were randomized. Of those, 63 veterans completed a follow-up interview. The intervention consisted of 6 home visits of 1 to 2 hours each and 2 telephone calls from an occupational therapist over 3 to 4 months. Family members were invited to participate during the home visits. The control group received usual clinic care with 2 telephone calls during the study period. All participants received the follow-up interview 3 to 4 months after baseline interviews. The severity of TBI was determined by a review of the electronic medical record using the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines. Findings of this study indicated that family members in the intervention group showed significantly lower depressive symptom scores and caregiver burden scores.9 Additionally, the veterans in the intervention group exhibited higher community integration and ability to manage their targeted outcomes. Further research may indicate that VIP could assist patients with TBI and caregivers in an active-duty population.

The DVBIC is the executive agent for a congressionally mandated 15-year longitudinal study on TBI incurred by members of the armed services in OEF and OIF. The John Warner National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2007 outlined the study. An initial finding identified the need for an HRQOL outcomes assessment specific to TBI caregivers.23 Having these data will allow investigators to fully determine the comprehensive impact of caring for a person who sustained a mild, moderate, severe, or penetrating TBI and to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to address caregivers’ needs. To date, the study has identified the following HRQOL themes generated among caregivers: social health, emotional health, physical/medical health, cognitive functioning, and feelings of loss (related to changing social roles). Carlozzi and colleagues noted that the study also aimed to identify a sensitive outcome measure to evaluate quality of life in the caregivers over time.7

Knowledge Gaps

Ongoing studies focus on caregiving for individuals with various illnesses and needs. Some of the information in each study may be beneficial to TBI caregivers who are not fully aware of resources and interventions. For example, Fortune and colleagues, Hirano and colleagues, and Grover and colleagues are studying caregiver activities involving other diseases to determine, more generally, which programs, activities, and coping strategies can decrease caregiver challenges.24-26 Further, understanding and addressing the needs of these families over many years will provide data that could inform policy, benefits, resources, and needed services (such as the Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010) and assist with family resilience efforts, including understanding and enhancing family protective and recovery factors.

As studies have indicated, some families do not report family distress when providing care to an individual with TBI. Understanding the factors that influence positive family adjustment is important to capture and perhaps replicate in future studies so that they can lead to effective treatment interventions. Although this review does not discuss caregiver needs for patients with TBI with disorders of consciousness that require more care than most caregivers can provide in the home setting, caregiving for this population deserves attention in future studies. Furthermore, an area that has not received much attention is the impact on children in the household. Children aged < 18 years can assist not only in the care of a disabled adult, but also of younger siblings; also they can help with household activities from housekeeping to meal preparation. Children also may provide physical and emotional support.

The impact of aging caregivers and subsequent needs for their own care as well as the person(s) they are providing care for has not been fully addressed. Areas requiring more research include both the aging caregiver taking care of an aging spouse or relative and the aging parent taking care of a young adult or child. Along with aging, the issue of long-term caregiving needs further development. For example, how do the differences between access to services between caregivers of adults with TBI in the military and those in the civilian sector impact the family/caregiver? Further research may answer questions such as:

- Which tools are most useful in evaluating and determining caregiver stress and burden?

- Are the needs of military and veteran caregivers unique?

- Do polytrauma patients with comorbid diagnoses have unique caregiver needs and trajectories?

- Do TBI caregiver stressors differ from stressors related to other medical conditions or chronic diseases?

- Is there a need for military and veteran TBI-specific caregiver programs?

- Which interventions best help caregivers and for how long?

- Should the approach to intervention depend on variables such as age and gender of the caregivers or relationship to the patient with a TBI (eg, spouse vs parent)?

Methods or processes to inform and update caregivers about available resources also are critically needed. Also, Sabab and colleagues noted the importance of research on the effects of denial as it relates to cognitive, emotional, social impact.27 Denial may impact delays in treatments.

Resource

Many national, state, local, and grassroots organizations provide information and support for persons with illness and/or disabilities. Most clinicians of neurologic, mental health, and cancer have developed various forms of support interventions for those with the disease and their caregivers (Table 2). Highlighted in this section are a few organizations that specifically provide resources for caregivers caring for active-duty service members or veterans with a TBI.

Although a caregiver generally does not receive money from an outside source for services, the DoD may consider the caregiver as a nonmedical attendant for an active-duty service member and provide a temporary stipend. The VA provides several support and service options for caregivers under the Caregiver Support Program, through which more than 300 VA health care professionals provide support to caregivers. The Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010 authorizes the VA to provide additional VA services for seriously injured post-9/11 veterans and their family caregivers through the Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (VA Caregiver Support Program). After meeting eligibility criteria, primary caregivers of post-9/11 veterans may receive a monthly stipend (based on the level of care needed) as well as comprehensive caregiver training, referral services, access to health care insurance, mental health services, counseling, and respite care. The Caregiver Support Program offers a toll-free support line and a 24-hour crisis hot line.

In 2014, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) outlined the VA health care improvements needed to manage the demand for the Caregiver Support Program, which are established at VA medical centers.28 The GAO reported that the “VA significantly underestimated caregivers’ demand for services… larger than expected workloads and …delays in approval determinations” with about 500 approved caregivers who are added to the program each month. Original estimates indicated that about 4,000 caregivers would be approved by September 2014; however, by May 2014 about 15,600 caregivers were approved.