User login

“So you want to be a gastroenterologist? What do you really want to do?” This is not an uncommon question that a trainee is faced with when progressing through residency and gastroenterology fellowship.

The list of possibilities includes general gastroenterology, advanced endoscopy, transplant hepatology, and neurogastroenterology and motility. From there, each subspecialty can be broken down further into organ system or a specific procedure of interest. Another necessary question is whether to pursue a career in academics or private practice. The first is for the resident who is interested in gaining experience in gastroenterology prior to starting a general gastroenterology fellowship (there are two programs that currently allow for this pathway). The other track is for those who have completed a general gastroenterology fellowship and are looking to enhance their academic careers by pursuing additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility.

There is currently a need for gastroenterologists interested in neurogastroenterology and motility. Among the most common diagnoses in an ambulatory setting, based on International Classification of Disease (ICD) coding, are abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, constipation, nausea and vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, and dysphagia.1,2 While many fellows are exposed to a wide range of motility patients during general gastroenterology fellowship, there is typically not a sufficient amount of training to attain “level 2” proficiency.2,3 In an effort to help standardize training there are recommended thresholds established and advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility can help fellows to attain that proficiency.2,3 The extra year can also help you prepare to run a motility lab, train nurses, establish lab protocols and quality standards, and manage referrals, which are important skills as a neurogastroenterology and motility specialist.

Types of programs

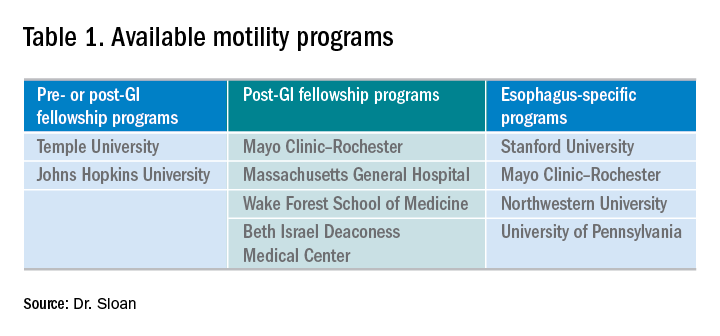

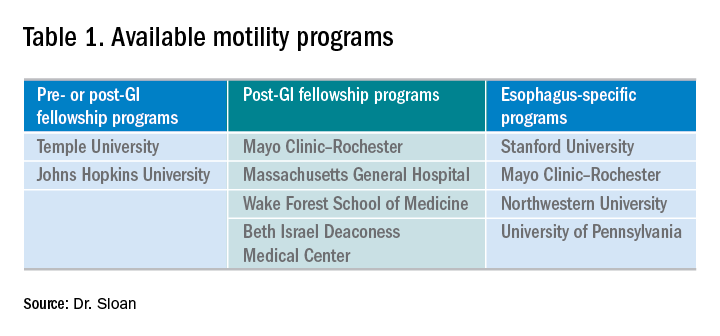

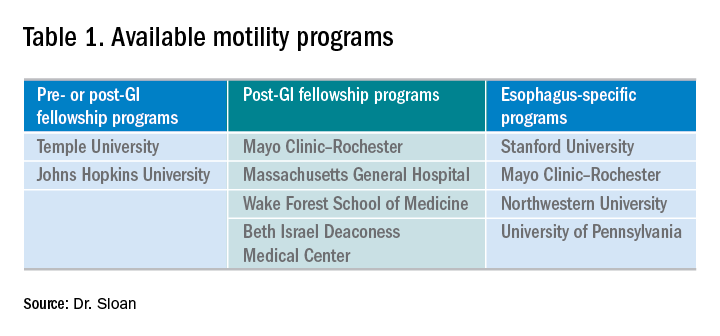

There are several different types of motility programs available. As mentioned previously, some programs afford individuals an opportunity to gain additional experience in gastroenterology before progressing to general gastroenterology fellowship. There are two programs that offer a 1-year fellowship in neurogastroenterology and motility, both prior to or after a general gastroenterology fellowship. Four programs offer 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships only after a general gastroenterology fellowship. While the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships cover esophageal motility, there are four programs that specifically focus solely on the esophagus (Table 1).

In addition to pursuing an extra year of training, interested gastroenterology fellows may choose to explore a 1-month Clinical Training Program sponsored by the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) at 1 of 10 centers.

Where to find programs

Currently, there is not a singular list of neurogastroenterology and motility programs available for review as you might find with an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) residency or fellowship. At present, the best way to identify the available programs is to search online. Motivation to select a specific program may be related to individual preference and can include geography and department expertise; this ultimately helps to create a focused list. With regard to the ANMS 1-month Clinical Training Program, the list of available programs is available on the society’s website and is for fellows currently in training who wish to incorporate neurogastroenterology and motility into their general GI fellowship.

How to apply

Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility is currently a non-ACGME pathway and does not offer a match process for its applicants. After identifying a program of interest, one can find specific instructions on how to apply at the programs’ websites. Typically the process involves reaching out to the program director, writing a letter of interest or personal statement, providing letters of recommendation, and interviewing. Each program has some variability in what is required and attention should be paid to the criteria listed on the specific website.

My experience

I was fortunate to have substantial exposure to esophageal motility in my general gastroenterology fellowship. Gaining this experience was invaluable and laid the foundation for my interest in neurogastroenterology and motility, and, specifically, esophageal dysmotility. My interest in neurogastroenterology and motility then collided with my desire to pursue a career in academics. Knowing the general trajectory for my future career, I began exploring the possibility of undergoing an additional 1-year fellowship early in my second year of GI fellowship. I worked closely with my program director to help define my future goals and to identify available places that would help me attain those goals. While I continued to have an interest in the esophagus, additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility would broaden my understanding and enhance my ability to manage complex patients and perform research at a tertiary care center. I investigated the different neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship programs online and followed the online application instructions. Utilizing national gastroenterology society conferences as networking opportunities, I was able to meet with the program director of my current neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship. In my third year of general gastroenterology fellowship I formally interviewed with the motility group at Johns Hopkins and was later accepted into the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship program.

Now, nearing the end of my 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship, I reflect on my extremely positive experience. Throughout the course of the year I have been able to work with multiple GI providers — each with their own area of expertise within the field. There has been a profound exposure to a wide variety of patients with a spectrum of motility conditions covering the entire GI tract. There has been ample opportunity to read motility studies with the guidance and support of the motility faculty to further enhance my skills. The additional year has broadened my exposure to, and the management of, the biopsychosocial aspect of this specific patient population. In line with that, I have had the ability to grow with regard to my use of pharmacology and recognize which symptom might benefit from a particular neuromodulator. An emphasis was also placed on learning the gut-brain axis, and, through multidisciplinary clinics, I worked closely with other disciplines such as psychiatry and GI clinical psychology. Furthermore, the additional year has allowed me to be involved in several research projects within neurogastroenterology and motility that will undoubtedly enhance my future career.

Conclusion

Deciding to pursue an additional year in neurogastroenterology and motility has been one that has helped to give a solid direction to my budding career. It has left me confident in managing this diverse and complex patient population and has helped prepare me for a career in academic gastroenterology. For those who are interested in academic neurogastroenterology and motility, an additional fellowship can help define you as a gastroenterologist and help you to pursue the career of your dreams.

Dr. Sloan is a clinical instructor in the division of gastroenterology at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.

References

1. Peery A. et al. Burden of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1731-41.e3.

2. Rao S., Parkman H. Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and gastrointestinal motility. Gastroenterology 2015;148:881-5.

3. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The gastroenterology core curriculum, third edition. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2012-18.

“So you want to be a gastroenterologist? What do you really want to do?” This is not an uncommon question that a trainee is faced with when progressing through residency and gastroenterology fellowship.

The list of possibilities includes general gastroenterology, advanced endoscopy, transplant hepatology, and neurogastroenterology and motility. From there, each subspecialty can be broken down further into organ system or a specific procedure of interest. Another necessary question is whether to pursue a career in academics or private practice. The first is for the resident who is interested in gaining experience in gastroenterology prior to starting a general gastroenterology fellowship (there are two programs that currently allow for this pathway). The other track is for those who have completed a general gastroenterology fellowship and are looking to enhance their academic careers by pursuing additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility.

There is currently a need for gastroenterologists interested in neurogastroenterology and motility. Among the most common diagnoses in an ambulatory setting, based on International Classification of Disease (ICD) coding, are abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, constipation, nausea and vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, and dysphagia.1,2 While many fellows are exposed to a wide range of motility patients during general gastroenterology fellowship, there is typically not a sufficient amount of training to attain “level 2” proficiency.2,3 In an effort to help standardize training there are recommended thresholds established and advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility can help fellows to attain that proficiency.2,3 The extra year can also help you prepare to run a motility lab, train nurses, establish lab protocols and quality standards, and manage referrals, which are important skills as a neurogastroenterology and motility specialist.

Types of programs

There are several different types of motility programs available. As mentioned previously, some programs afford individuals an opportunity to gain additional experience in gastroenterology before progressing to general gastroenterology fellowship. There are two programs that offer a 1-year fellowship in neurogastroenterology and motility, both prior to or after a general gastroenterology fellowship. Four programs offer 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships only after a general gastroenterology fellowship. While the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships cover esophageal motility, there are four programs that specifically focus solely on the esophagus (Table 1).

In addition to pursuing an extra year of training, interested gastroenterology fellows may choose to explore a 1-month Clinical Training Program sponsored by the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) at 1 of 10 centers.

Where to find programs

Currently, there is not a singular list of neurogastroenterology and motility programs available for review as you might find with an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) residency or fellowship. At present, the best way to identify the available programs is to search online. Motivation to select a specific program may be related to individual preference and can include geography and department expertise; this ultimately helps to create a focused list. With regard to the ANMS 1-month Clinical Training Program, the list of available programs is available on the society’s website and is for fellows currently in training who wish to incorporate neurogastroenterology and motility into their general GI fellowship.

How to apply

Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility is currently a non-ACGME pathway and does not offer a match process for its applicants. After identifying a program of interest, one can find specific instructions on how to apply at the programs’ websites. Typically the process involves reaching out to the program director, writing a letter of interest or personal statement, providing letters of recommendation, and interviewing. Each program has some variability in what is required and attention should be paid to the criteria listed on the specific website.

My experience

I was fortunate to have substantial exposure to esophageal motility in my general gastroenterology fellowship. Gaining this experience was invaluable and laid the foundation for my interest in neurogastroenterology and motility, and, specifically, esophageal dysmotility. My interest in neurogastroenterology and motility then collided with my desire to pursue a career in academics. Knowing the general trajectory for my future career, I began exploring the possibility of undergoing an additional 1-year fellowship early in my second year of GI fellowship. I worked closely with my program director to help define my future goals and to identify available places that would help me attain those goals. While I continued to have an interest in the esophagus, additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility would broaden my understanding and enhance my ability to manage complex patients and perform research at a tertiary care center. I investigated the different neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship programs online and followed the online application instructions. Utilizing national gastroenterology society conferences as networking opportunities, I was able to meet with the program director of my current neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship. In my third year of general gastroenterology fellowship I formally interviewed with the motility group at Johns Hopkins and was later accepted into the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship program.

Now, nearing the end of my 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship, I reflect on my extremely positive experience. Throughout the course of the year I have been able to work with multiple GI providers — each with their own area of expertise within the field. There has been a profound exposure to a wide variety of patients with a spectrum of motility conditions covering the entire GI tract. There has been ample opportunity to read motility studies with the guidance and support of the motility faculty to further enhance my skills. The additional year has broadened my exposure to, and the management of, the biopsychosocial aspect of this specific patient population. In line with that, I have had the ability to grow with regard to my use of pharmacology and recognize which symptom might benefit from a particular neuromodulator. An emphasis was also placed on learning the gut-brain axis, and, through multidisciplinary clinics, I worked closely with other disciplines such as psychiatry and GI clinical psychology. Furthermore, the additional year has allowed me to be involved in several research projects within neurogastroenterology and motility that will undoubtedly enhance my future career.

Conclusion

Deciding to pursue an additional year in neurogastroenterology and motility has been one that has helped to give a solid direction to my budding career. It has left me confident in managing this diverse and complex patient population and has helped prepare me for a career in academic gastroenterology. For those who are interested in academic neurogastroenterology and motility, an additional fellowship can help define you as a gastroenterologist and help you to pursue the career of your dreams.

Dr. Sloan is a clinical instructor in the division of gastroenterology at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.

References

1. Peery A. et al. Burden of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1731-41.e3.

2. Rao S., Parkman H. Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and gastrointestinal motility. Gastroenterology 2015;148:881-5.

3. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The gastroenterology core curriculum, third edition. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2012-18.

“So you want to be a gastroenterologist? What do you really want to do?” This is not an uncommon question that a trainee is faced with when progressing through residency and gastroenterology fellowship.

The list of possibilities includes general gastroenterology, advanced endoscopy, transplant hepatology, and neurogastroenterology and motility. From there, each subspecialty can be broken down further into organ system or a specific procedure of interest. Another necessary question is whether to pursue a career in academics or private practice. The first is for the resident who is interested in gaining experience in gastroenterology prior to starting a general gastroenterology fellowship (there are two programs that currently allow for this pathway). The other track is for those who have completed a general gastroenterology fellowship and are looking to enhance their academic careers by pursuing additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility.

There is currently a need for gastroenterologists interested in neurogastroenterology and motility. Among the most common diagnoses in an ambulatory setting, based on International Classification of Disease (ICD) coding, are abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, constipation, nausea and vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, and dysphagia.1,2 While many fellows are exposed to a wide range of motility patients during general gastroenterology fellowship, there is typically not a sufficient amount of training to attain “level 2” proficiency.2,3 In an effort to help standardize training there are recommended thresholds established and advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility can help fellows to attain that proficiency.2,3 The extra year can also help you prepare to run a motility lab, train nurses, establish lab protocols and quality standards, and manage referrals, which are important skills as a neurogastroenterology and motility specialist.

Types of programs

There are several different types of motility programs available. As mentioned previously, some programs afford individuals an opportunity to gain additional experience in gastroenterology before progressing to general gastroenterology fellowship. There are two programs that offer a 1-year fellowship in neurogastroenterology and motility, both prior to or after a general gastroenterology fellowship. Four programs offer 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships only after a general gastroenterology fellowship. While the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships cover esophageal motility, there are four programs that specifically focus solely on the esophagus (Table 1).

In addition to pursuing an extra year of training, interested gastroenterology fellows may choose to explore a 1-month Clinical Training Program sponsored by the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) at 1 of 10 centers.

Where to find programs

Currently, there is not a singular list of neurogastroenterology and motility programs available for review as you might find with an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) residency or fellowship. At present, the best way to identify the available programs is to search online. Motivation to select a specific program may be related to individual preference and can include geography and department expertise; this ultimately helps to create a focused list. With regard to the ANMS 1-month Clinical Training Program, the list of available programs is available on the society’s website and is for fellows currently in training who wish to incorporate neurogastroenterology and motility into their general GI fellowship.

How to apply

Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility is currently a non-ACGME pathway and does not offer a match process for its applicants. After identifying a program of interest, one can find specific instructions on how to apply at the programs’ websites. Typically the process involves reaching out to the program director, writing a letter of interest or personal statement, providing letters of recommendation, and interviewing. Each program has some variability in what is required and attention should be paid to the criteria listed on the specific website.

My experience

I was fortunate to have substantial exposure to esophageal motility in my general gastroenterology fellowship. Gaining this experience was invaluable and laid the foundation for my interest in neurogastroenterology and motility, and, specifically, esophageal dysmotility. My interest in neurogastroenterology and motility then collided with my desire to pursue a career in academics. Knowing the general trajectory for my future career, I began exploring the possibility of undergoing an additional 1-year fellowship early in my second year of GI fellowship. I worked closely with my program director to help define my future goals and to identify available places that would help me attain those goals. While I continued to have an interest in the esophagus, additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility would broaden my understanding and enhance my ability to manage complex patients and perform research at a tertiary care center. I investigated the different neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship programs online and followed the online application instructions. Utilizing national gastroenterology society conferences as networking opportunities, I was able to meet with the program director of my current neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship. In my third year of general gastroenterology fellowship I formally interviewed with the motility group at Johns Hopkins and was later accepted into the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship program.

Now, nearing the end of my 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship, I reflect on my extremely positive experience. Throughout the course of the year I have been able to work with multiple GI providers — each with their own area of expertise within the field. There has been a profound exposure to a wide variety of patients with a spectrum of motility conditions covering the entire GI tract. There has been ample opportunity to read motility studies with the guidance and support of the motility faculty to further enhance my skills. The additional year has broadened my exposure to, and the management of, the biopsychosocial aspect of this specific patient population. In line with that, I have had the ability to grow with regard to my use of pharmacology and recognize which symptom might benefit from a particular neuromodulator. An emphasis was also placed on learning the gut-brain axis, and, through multidisciplinary clinics, I worked closely with other disciplines such as psychiatry and GI clinical psychology. Furthermore, the additional year has allowed me to be involved in several research projects within neurogastroenterology and motility that will undoubtedly enhance my future career.

Conclusion

Deciding to pursue an additional year in neurogastroenterology and motility has been one that has helped to give a solid direction to my budding career. It has left me confident in managing this diverse and complex patient population and has helped prepare me for a career in academic gastroenterology. For those who are interested in academic neurogastroenterology and motility, an additional fellowship can help define you as a gastroenterologist and help you to pursue the career of your dreams.

Dr. Sloan is a clinical instructor in the division of gastroenterology at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.

References

1. Peery A. et al. Burden of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1731-41.e3.

2. Rao S., Parkman H. Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and gastrointestinal motility. Gastroenterology 2015;148:881-5.

3. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The gastroenterology core curriculum, third edition. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2012-18.