User login

Do hospitalists, or anyone who spends time practicing within the hospital setting, feel well equipped to deal with all aspects of an inpatient’s chronic pain? In palliative care, we have training and interest in this field, our program has some resources earmarked for this, and we face chronic pain multiple times a day. Yet, it is difficult to recall a patient encounter in which some piece of the pain plan did not seem bereft of a key element.

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) data, government agencies and legislation, media, and other avenues call more attention to the escalating problem of the culture and care of chronic pain. And, because the Joint Commission, HCAHPS, and other trackers of pain in the hospital do not distinguish between acute pain and chronic pain, we are challenged with creating approaches to a problem that in many ways is out of our control.

At Seton Medical Center in Austin, Tex., we have proposed and performed a short pilot of a model that allowed us to see where our gaps exist and to think through how to shrink them. Importantly, it made an impression on our leadership to the degree that they are considering a business plan we put forward to make this a permanent part of our institution.

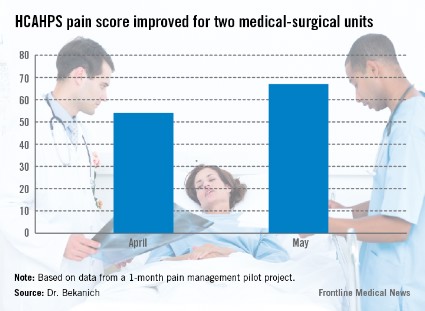

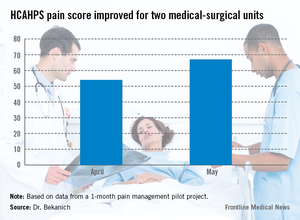

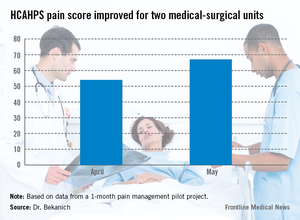

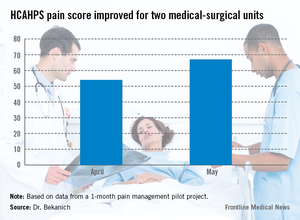

Our pilot project produced data that made us proud as well as demonstrated areas that need improvement. For pain specialties that are hospital based, the response times were excellent. These consults were typically seen within 4 hours of the order being placed. For those specialties that do not have a regular inpatient presence, new consults were often not seen until the next day causing patient frustration. HCAHPS rose during that month (see graphic).

But before exploring the model we have proposed and piloted in conjunction with hospitalists, it is worth examining what we call "pain truths" for chronic pain (CP):

• CP is the most common symptom of many serious or advanced illnesses. While often thought of as a condition associated with cancer, it is now recognized as a part of almost every major illness arising from the failure, or damage to, each major organ. We also have a host of patients with painful conditions that have no clear etiology in areas such as the back, abdomen, and extremities.

• In most cases, CP began long before the patient was hospitalized and has no cure. It is frustrating to be on either side of this equation, because the patient does not always appreciate our limitations, and we can be left feeling less than our best for not being able to solve the problem.

• Hospital operations have not been well equipped to deal with chronic pain. The history of pain control in the hospital is such that we’ve excelled in the perioperative realm and in controlling other forms of acute pain. This is not the case with chronic pain. Whether it is a lack of useful measurements (how helpful is it to use a 10-point pain scale for CP who "feel fine" at a 9 or 10 and rate their pain at 100 out of 10 when they are having an exacerbation?), inadequate access to procedures for CP, or an absence of teams that specialize in tackling it, the number of hospitals fully prepared for CP are indeed few in number.

• No one specialty or provider deals with all facets or forms of pain. This statement frequently elicits surprise. However, no single training tract is available that teaches how to manage medications in medically complex patients, perform procedures, use a variety of counseling techniques, attend to the psychosocial barriers, and improve function via different physical therapies. It takes a diverse team to cover CP from tip to tail.

• The educational and cultural gaps in pain evaluation and management for health care providers are vast. The medical literature is flush with testimonials of this.

• Inpatient incentives for excellence in pain management are evolving from unfavorable to favorable. With reimbursements tied to HCAHPS and readmission, along with a shift toward rewarding value, we have an opportunity to change the balance sheet in resourcing pain teams.

• Comprehensive inpatient management is not possible without a complimentary outpatient component. Without the "safe place to land," patients may as well run into roundabouts that have an equal chance of spilling them out back in the direction of the hospital. These long-term problems need long-term solutions. Frequently, the best we can hope for in the hospital is to deliver a CP patient an experience that highlights the expression of empathy, demonstrates our commitment to continuously trying to help them, and cools off their pain to a tolerable level. The bulk of the work needs to be done outside the hospital walls.

Making a ‘bright spot’

Using these truths to construct a framework for effective inpatient collaborations, we set about piloting the following model. Please note that the purpose of this pilot project was not to have the intervention stand up to the rigors of scrutiny demanded by a clinical trial. Our intent was to see if we could create a "bright spot" for pain management, cobbling together existing resources, with the hope that hospital leadership would support us with new resources should we demonstrate a promising model.

Seton Medical Center is a large, urban hospital with providers from both the community and an academic medical group practice. We sought buy in for this project with the hospitalists, surgeons, pharmacy, nursing staff, and leadership. The pilot lasted for 1 month and took place on two med-surg units. Currently, there is no dedicated pain team in this hospital. The disciplines that provided pain management were anesthesia, behavioral health, palliative care, and physical medicine, and rehabilitation. The proposal to the hospitalists and surgeons was that once the pain team was involved all pain management decisions through the responsible pain team in an attempt to bring clarity and consistency to the pain plan.

• Consults. Consults were triggered one of three ways. All required a physician order and allowed the physician to opt-out if they disagreed with potential consults generated from options 2 or 3.

Option 1 – Traditional route: The provider saw a need for assistance with pain management and puts in the order.

Option 2 – Nurse initiated: The nurse felt as though pain was uncontrolled or there were other concerns about pain.

Option 3 – Patient initiated: After 48 hours of admission, patients experiencing pain were asked if they would like to visit with someone from the pain team.

• Hotline. A pain hotline was set up for a "one call, that’s all" approach. This obviated the need for those calling us to be familiar with which specialty would be most appropriate for managing a specific painful condition. Prior to the start of the pilot, each specialty agreed upon which etiologies of pain they would be primarily responsible for managing. For example, if it was perioperative pain, then anesthesia would be the primary pain service; if the diagnosis was pain that was related to a neoplastic process, then palliative care would be deployed.

• First contact. Initial encounters with the patient were through an advance practice nurse (APN). The APN was familiar with the purview of each specialty. After quickly assessing the patient, the nurse would distribute a leaflet to the patient and families that provided education about pain, including expectations, limitations, and a definition of how the pain team functions. For instance, they were provided with an explanation of why and when we change the route of administration of opioids from IV to PO. The APN would then activate the proper service, which would take ownership of pain management for that patient while they were hospitalized. We frequently involved colleagues from the different pain specialties to provide a comprehensive service. For example, when our team would see a patient with pain related to cirrhosis but they also had poor coping mechanisms, we would involve our behavioral health colleagues.

• Discharge planning. We sought to have a specific pain discharge plan documented in each patient’s progress note prior to leaving the hospital. This included which medications we recommend, the written prescriptions, and who would be responsible for continued management of the pain after discharge. If this were a primary care doctor or specialist that knows the patient we personally contacted that provider to assure that they concurred with our plans. If the patient had no such provider or their provider was uncomfortable managing the pain then we saw them as an outpatient in our respective clinics within 2 weeks of their hospital release.

We constructed our metrics with the awareness that pain scores do not paint a picture reflective of the patient experience or quality of care. We believe that, especially in the CP population, that less emphasis will be placed on pain scores and more attention given to some of these other markers of effectiveness. Metrics included pain scores, patient’s ability to function, satisfaction through HCAHPS, whether or not a documented pain discharge plan was in the medical record, tolerability, safety measures, and pharmacy use. While a detailed analysis of our results is beyond the scope of this piece, we were pleased with our data. For instance, 91% of our patients had a specific pain discharge plan documented.

Creation of a bright spot in the hospital for pain management was not the only benefit. This short pilot project created what we see as elements of sustainability on the nursing staff and providers – getting nurses and physicians on the same page about the goals of pain management, looking at pain through a more refined lens, and building an improved sense of teamwork needed to deliver this complex care.

Our physician colleagues appreciated this service to the point that we had daily requests to include patients in the pilot that were not on the participating units. Response for the program was so enthusiastic that it incurred no additional costs. Everyone who took part did so on a voluntary basis, and those who don’t normally take call at nights or on weekends did so because of their commitment to the cause.

Most importantly, patients and families were grateful, and there was a recurrent feeling that they were well educated about their medications and other aspects of their health care.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin. Share your thoughts with Dr. Bekanich at SJBekanich@seton.org.

Do hospitalists, or anyone who spends time practicing within the hospital setting, feel well equipped to deal with all aspects of an inpatient’s chronic pain? In palliative care, we have training and interest in this field, our program has some resources earmarked for this, and we face chronic pain multiple times a day. Yet, it is difficult to recall a patient encounter in which some piece of the pain plan did not seem bereft of a key element.

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) data, government agencies and legislation, media, and other avenues call more attention to the escalating problem of the culture and care of chronic pain. And, because the Joint Commission, HCAHPS, and other trackers of pain in the hospital do not distinguish between acute pain and chronic pain, we are challenged with creating approaches to a problem that in many ways is out of our control.

At Seton Medical Center in Austin, Tex., we have proposed and performed a short pilot of a model that allowed us to see where our gaps exist and to think through how to shrink them. Importantly, it made an impression on our leadership to the degree that they are considering a business plan we put forward to make this a permanent part of our institution.

Our pilot project produced data that made us proud as well as demonstrated areas that need improvement. For pain specialties that are hospital based, the response times were excellent. These consults were typically seen within 4 hours of the order being placed. For those specialties that do not have a regular inpatient presence, new consults were often not seen until the next day causing patient frustration. HCAHPS rose during that month (see graphic).

But before exploring the model we have proposed and piloted in conjunction with hospitalists, it is worth examining what we call "pain truths" for chronic pain (CP):

• CP is the most common symptom of many serious or advanced illnesses. While often thought of as a condition associated with cancer, it is now recognized as a part of almost every major illness arising from the failure, or damage to, each major organ. We also have a host of patients with painful conditions that have no clear etiology in areas such as the back, abdomen, and extremities.

• In most cases, CP began long before the patient was hospitalized and has no cure. It is frustrating to be on either side of this equation, because the patient does not always appreciate our limitations, and we can be left feeling less than our best for not being able to solve the problem.

• Hospital operations have not been well equipped to deal with chronic pain. The history of pain control in the hospital is such that we’ve excelled in the perioperative realm and in controlling other forms of acute pain. This is not the case with chronic pain. Whether it is a lack of useful measurements (how helpful is it to use a 10-point pain scale for CP who "feel fine" at a 9 or 10 and rate their pain at 100 out of 10 when they are having an exacerbation?), inadequate access to procedures for CP, or an absence of teams that specialize in tackling it, the number of hospitals fully prepared for CP are indeed few in number.

• No one specialty or provider deals with all facets or forms of pain. This statement frequently elicits surprise. However, no single training tract is available that teaches how to manage medications in medically complex patients, perform procedures, use a variety of counseling techniques, attend to the psychosocial barriers, and improve function via different physical therapies. It takes a diverse team to cover CP from tip to tail.

• The educational and cultural gaps in pain evaluation and management for health care providers are vast. The medical literature is flush with testimonials of this.

• Inpatient incentives for excellence in pain management are evolving from unfavorable to favorable. With reimbursements tied to HCAHPS and readmission, along with a shift toward rewarding value, we have an opportunity to change the balance sheet in resourcing pain teams.

• Comprehensive inpatient management is not possible without a complimentary outpatient component. Without the "safe place to land," patients may as well run into roundabouts that have an equal chance of spilling them out back in the direction of the hospital. These long-term problems need long-term solutions. Frequently, the best we can hope for in the hospital is to deliver a CP patient an experience that highlights the expression of empathy, demonstrates our commitment to continuously trying to help them, and cools off their pain to a tolerable level. The bulk of the work needs to be done outside the hospital walls.

Making a ‘bright spot’

Using these truths to construct a framework for effective inpatient collaborations, we set about piloting the following model. Please note that the purpose of this pilot project was not to have the intervention stand up to the rigors of scrutiny demanded by a clinical trial. Our intent was to see if we could create a "bright spot" for pain management, cobbling together existing resources, with the hope that hospital leadership would support us with new resources should we demonstrate a promising model.

Seton Medical Center is a large, urban hospital with providers from both the community and an academic medical group practice. We sought buy in for this project with the hospitalists, surgeons, pharmacy, nursing staff, and leadership. The pilot lasted for 1 month and took place on two med-surg units. Currently, there is no dedicated pain team in this hospital. The disciplines that provided pain management were anesthesia, behavioral health, palliative care, and physical medicine, and rehabilitation. The proposal to the hospitalists and surgeons was that once the pain team was involved all pain management decisions through the responsible pain team in an attempt to bring clarity and consistency to the pain plan.

• Consults. Consults were triggered one of three ways. All required a physician order and allowed the physician to opt-out if they disagreed with potential consults generated from options 2 or 3.

Option 1 – Traditional route: The provider saw a need for assistance with pain management and puts in the order.

Option 2 – Nurse initiated: The nurse felt as though pain was uncontrolled or there were other concerns about pain.

Option 3 – Patient initiated: After 48 hours of admission, patients experiencing pain were asked if they would like to visit with someone from the pain team.

• Hotline. A pain hotline was set up for a "one call, that’s all" approach. This obviated the need for those calling us to be familiar with which specialty would be most appropriate for managing a specific painful condition. Prior to the start of the pilot, each specialty agreed upon which etiologies of pain they would be primarily responsible for managing. For example, if it was perioperative pain, then anesthesia would be the primary pain service; if the diagnosis was pain that was related to a neoplastic process, then palliative care would be deployed.

• First contact. Initial encounters with the patient were through an advance practice nurse (APN). The APN was familiar with the purview of each specialty. After quickly assessing the patient, the nurse would distribute a leaflet to the patient and families that provided education about pain, including expectations, limitations, and a definition of how the pain team functions. For instance, they were provided with an explanation of why and when we change the route of administration of opioids from IV to PO. The APN would then activate the proper service, which would take ownership of pain management for that patient while they were hospitalized. We frequently involved colleagues from the different pain specialties to provide a comprehensive service. For example, when our team would see a patient with pain related to cirrhosis but they also had poor coping mechanisms, we would involve our behavioral health colleagues.

• Discharge planning. We sought to have a specific pain discharge plan documented in each patient’s progress note prior to leaving the hospital. This included which medications we recommend, the written prescriptions, and who would be responsible for continued management of the pain after discharge. If this were a primary care doctor or specialist that knows the patient we personally contacted that provider to assure that they concurred with our plans. If the patient had no such provider or their provider was uncomfortable managing the pain then we saw them as an outpatient in our respective clinics within 2 weeks of their hospital release.

We constructed our metrics with the awareness that pain scores do not paint a picture reflective of the patient experience or quality of care. We believe that, especially in the CP population, that less emphasis will be placed on pain scores and more attention given to some of these other markers of effectiveness. Metrics included pain scores, patient’s ability to function, satisfaction through HCAHPS, whether or not a documented pain discharge plan was in the medical record, tolerability, safety measures, and pharmacy use. While a detailed analysis of our results is beyond the scope of this piece, we were pleased with our data. For instance, 91% of our patients had a specific pain discharge plan documented.

Creation of a bright spot in the hospital for pain management was not the only benefit. This short pilot project created what we see as elements of sustainability on the nursing staff and providers – getting nurses and physicians on the same page about the goals of pain management, looking at pain through a more refined lens, and building an improved sense of teamwork needed to deliver this complex care.

Our physician colleagues appreciated this service to the point that we had daily requests to include patients in the pilot that were not on the participating units. Response for the program was so enthusiastic that it incurred no additional costs. Everyone who took part did so on a voluntary basis, and those who don’t normally take call at nights or on weekends did so because of their commitment to the cause.

Most importantly, patients and families were grateful, and there was a recurrent feeling that they were well educated about their medications and other aspects of their health care.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin. Share your thoughts with Dr. Bekanich at SJBekanich@seton.org.

Do hospitalists, or anyone who spends time practicing within the hospital setting, feel well equipped to deal with all aspects of an inpatient’s chronic pain? In palliative care, we have training and interest in this field, our program has some resources earmarked for this, and we face chronic pain multiple times a day. Yet, it is difficult to recall a patient encounter in which some piece of the pain plan did not seem bereft of a key element.

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) data, government agencies and legislation, media, and other avenues call more attention to the escalating problem of the culture and care of chronic pain. And, because the Joint Commission, HCAHPS, and other trackers of pain in the hospital do not distinguish between acute pain and chronic pain, we are challenged with creating approaches to a problem that in many ways is out of our control.

At Seton Medical Center in Austin, Tex., we have proposed and performed a short pilot of a model that allowed us to see where our gaps exist and to think through how to shrink them. Importantly, it made an impression on our leadership to the degree that they are considering a business plan we put forward to make this a permanent part of our institution.

Our pilot project produced data that made us proud as well as demonstrated areas that need improvement. For pain specialties that are hospital based, the response times were excellent. These consults were typically seen within 4 hours of the order being placed. For those specialties that do not have a regular inpatient presence, new consults were often not seen until the next day causing patient frustration. HCAHPS rose during that month (see graphic).

But before exploring the model we have proposed and piloted in conjunction with hospitalists, it is worth examining what we call "pain truths" for chronic pain (CP):

• CP is the most common symptom of many serious or advanced illnesses. While often thought of as a condition associated with cancer, it is now recognized as a part of almost every major illness arising from the failure, or damage to, each major organ. We also have a host of patients with painful conditions that have no clear etiology in areas such as the back, abdomen, and extremities.

• In most cases, CP began long before the patient was hospitalized and has no cure. It is frustrating to be on either side of this equation, because the patient does not always appreciate our limitations, and we can be left feeling less than our best for not being able to solve the problem.

• Hospital operations have not been well equipped to deal with chronic pain. The history of pain control in the hospital is such that we’ve excelled in the perioperative realm and in controlling other forms of acute pain. This is not the case with chronic pain. Whether it is a lack of useful measurements (how helpful is it to use a 10-point pain scale for CP who "feel fine" at a 9 or 10 and rate their pain at 100 out of 10 when they are having an exacerbation?), inadequate access to procedures for CP, or an absence of teams that specialize in tackling it, the number of hospitals fully prepared for CP are indeed few in number.

• No one specialty or provider deals with all facets or forms of pain. This statement frequently elicits surprise. However, no single training tract is available that teaches how to manage medications in medically complex patients, perform procedures, use a variety of counseling techniques, attend to the psychosocial barriers, and improve function via different physical therapies. It takes a diverse team to cover CP from tip to tail.

• The educational and cultural gaps in pain evaluation and management for health care providers are vast. The medical literature is flush with testimonials of this.

• Inpatient incentives for excellence in pain management are evolving from unfavorable to favorable. With reimbursements tied to HCAHPS and readmission, along with a shift toward rewarding value, we have an opportunity to change the balance sheet in resourcing pain teams.

• Comprehensive inpatient management is not possible without a complimentary outpatient component. Without the "safe place to land," patients may as well run into roundabouts that have an equal chance of spilling them out back in the direction of the hospital. These long-term problems need long-term solutions. Frequently, the best we can hope for in the hospital is to deliver a CP patient an experience that highlights the expression of empathy, demonstrates our commitment to continuously trying to help them, and cools off their pain to a tolerable level. The bulk of the work needs to be done outside the hospital walls.

Making a ‘bright spot’

Using these truths to construct a framework for effective inpatient collaborations, we set about piloting the following model. Please note that the purpose of this pilot project was not to have the intervention stand up to the rigors of scrutiny demanded by a clinical trial. Our intent was to see if we could create a "bright spot" for pain management, cobbling together existing resources, with the hope that hospital leadership would support us with new resources should we demonstrate a promising model.

Seton Medical Center is a large, urban hospital with providers from both the community and an academic medical group practice. We sought buy in for this project with the hospitalists, surgeons, pharmacy, nursing staff, and leadership. The pilot lasted for 1 month and took place on two med-surg units. Currently, there is no dedicated pain team in this hospital. The disciplines that provided pain management were anesthesia, behavioral health, palliative care, and physical medicine, and rehabilitation. The proposal to the hospitalists and surgeons was that once the pain team was involved all pain management decisions through the responsible pain team in an attempt to bring clarity and consistency to the pain plan.

• Consults. Consults were triggered one of three ways. All required a physician order and allowed the physician to opt-out if they disagreed with potential consults generated from options 2 or 3.

Option 1 – Traditional route: The provider saw a need for assistance with pain management and puts in the order.

Option 2 – Nurse initiated: The nurse felt as though pain was uncontrolled or there were other concerns about pain.

Option 3 – Patient initiated: After 48 hours of admission, patients experiencing pain were asked if they would like to visit with someone from the pain team.

• Hotline. A pain hotline was set up for a "one call, that’s all" approach. This obviated the need for those calling us to be familiar with which specialty would be most appropriate for managing a specific painful condition. Prior to the start of the pilot, each specialty agreed upon which etiologies of pain they would be primarily responsible for managing. For example, if it was perioperative pain, then anesthesia would be the primary pain service; if the diagnosis was pain that was related to a neoplastic process, then palliative care would be deployed.

• First contact. Initial encounters with the patient were through an advance practice nurse (APN). The APN was familiar with the purview of each specialty. After quickly assessing the patient, the nurse would distribute a leaflet to the patient and families that provided education about pain, including expectations, limitations, and a definition of how the pain team functions. For instance, they were provided with an explanation of why and when we change the route of administration of opioids from IV to PO. The APN would then activate the proper service, which would take ownership of pain management for that patient while they were hospitalized. We frequently involved colleagues from the different pain specialties to provide a comprehensive service. For example, when our team would see a patient with pain related to cirrhosis but they also had poor coping mechanisms, we would involve our behavioral health colleagues.

• Discharge planning. We sought to have a specific pain discharge plan documented in each patient’s progress note prior to leaving the hospital. This included which medications we recommend, the written prescriptions, and who would be responsible for continued management of the pain after discharge. If this were a primary care doctor or specialist that knows the patient we personally contacted that provider to assure that they concurred with our plans. If the patient had no such provider or their provider was uncomfortable managing the pain then we saw them as an outpatient in our respective clinics within 2 weeks of their hospital release.

We constructed our metrics with the awareness that pain scores do not paint a picture reflective of the patient experience or quality of care. We believe that, especially in the CP population, that less emphasis will be placed on pain scores and more attention given to some of these other markers of effectiveness. Metrics included pain scores, patient’s ability to function, satisfaction through HCAHPS, whether or not a documented pain discharge plan was in the medical record, tolerability, safety measures, and pharmacy use. While a detailed analysis of our results is beyond the scope of this piece, we were pleased with our data. For instance, 91% of our patients had a specific pain discharge plan documented.

Creation of a bright spot in the hospital for pain management was not the only benefit. This short pilot project created what we see as elements of sustainability on the nursing staff and providers – getting nurses and physicians on the same page about the goals of pain management, looking at pain through a more refined lens, and building an improved sense of teamwork needed to deliver this complex care.

Our physician colleagues appreciated this service to the point that we had daily requests to include patients in the pilot that were not on the participating units. Response for the program was so enthusiastic that it incurred no additional costs. Everyone who took part did so on a voluntary basis, and those who don’t normally take call at nights or on weekends did so because of their commitment to the cause.

Most importantly, patients and families were grateful, and there was a recurrent feeling that they were well educated about their medications and other aspects of their health care.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin. Share your thoughts with Dr. Bekanich at SJBekanich@seton.org.