User login

From the Center for Patients and Families (Dr. Fagan, Ms. Wong, Ms. Morrison, Ms. Carnie), and the Division of Women’s Health and Gender Biology (Dr. Lewis-O’Connor), Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe and illustrate the phases of creating, recruiting, launching, and sustaining a successful Patient and Family Advisory Council (PFAC) in a hospital setting.

- Method: Descriptive report.

- Results: There are 4 stages in creating and establishing a PFAC: council preparation, patient/family advisor recruitment, council launch, and sustaining an established council. Each stage poses challenges that need to be addressed in order to progress to the next stage. The ability for hospital leadership to authentically partner with patient and family advisors is key to maintaining and sustaining PFACs.

- Conclusion: The success of a PFAC is based on leadership support, advisors’ commitment to their PFAC, and the ability to sustain the council. PFACs can promote patient- and family-centered care and shift the model of care from a prescribed model to one that embraces partnerships with patients while advancing care delivery. As patient- and family-centered care advances, it is important that best practices and resources for building and sustaining PFACs are developed and made available to ensure all hospitals have access to this valuable resource.

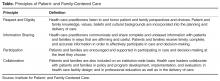

Throughout the country, families, patients, and health care professionals are working together in new ways, including within patient and family advisory councils (PFACs). First established in the 1990s, PFACs became widespread after patient-centeredness was identified by the Institute of Medicine as one of the 6 aims of quality health care [1]. PFACs were created to institutionalize a partnership between hospital leadership, clinicians, patients, and families to improve care delivery. Through this partnership, PFACs facilitate the sharing of patient perspectives and input on hospital policies and programs; serve as a resource to providers; and promote relationships between staff, patients, and family members [2]. PFACs also play an important role in promoting patient- and family-centered care, ensuring that patient needs and values are at the center of the care delivery system.

The BWH Center for Patients and Families includes the executive director, a project manager, and a senior patient advisor, who together oversee the PFACs. The project manager provides logistical support and is available as concerns arise, working closely with the senior patient advisor to ensure patient/family advisors are acclimated to their role and all PFACs run smoothly. The senior patient advisor is a volunteer advisor and patient advocate with long term experience creating and sustaining PFACs and mentoring patient/family advisors. Her role as a mentor includes attending PFAC meetings to model skills and behaviors for other advisors and working with them to ensure they are comfortable in their PFAC. Her advocacy work includes listening to and helping to articulate lived patient/family experiences as compelling narratives, which can be shared with hospital leadership and used as exemplars to spur change. Together, the team recruits and trains patient/family advisors, support all phases of PFAC development, and represent the patient/family voice within the hospital.

In this article, we describe and illustrate the 4 stages of creating and sustaining a successful PFAC to provide guidance and lessons learned to organizations seeking to develop this valuable resource. These stages are: (1) council preparation, (2) patient/family advisor recruitment, (3) council launch, and (4) sustaining an established council.

Council Preparation

Preparation of the PFAC occurs once hospital or service line leadership has identified a need for and is committed to having a PFAC. Leadership contacts the executive director of the Center for Patients and Families to discuss the strategy and vision of the council. The executive director describes the attributes sought in an advisor and the core principles of patient- and family-centered care. This discussion includes recruitment methods, meeting logistics, and who will serve as council chair. The council chair should be in a leadership role and willing to champion the PFAC for their service line. The executive director discusses what is being planned with relevant clinicians and staff at a staff meeting in order to foster buy-in and involve them in the council recruitment process.

The BWH Center for Patients and Families has adapted Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care recommendations for PFAC logistics and structure [3]. Councils generally meet monthly for 90 minutes excluding August and December. As volunteers, our advisors receive no monetary compensation but receive complimentary parking and are often provided meals. Advisors are asked to commit to a 3-year term with the understanding that personal issues can arise and their commitment may change; after their term, they are welcome to continue. We recommend to leadership that PFACs be comprised of no more than 1 staff member to every 4 advisors. This ratio seeks to address any potential power imbalance and promotes a feeling of ownership of their council . The project manager works with leadership in creating council guidelines, including the council’s goals, expectations, and each member’s role.

Patient/Family Advisor Recruitment

We ask service line providers and staff to nominate patients and family members they believe would be suitable advisors. The attributes we look for in an advisor include their ability to: (1) share personal experiences in ways that professional and support staff can learn from, (2) see the big picture of a challenge or scenario and give advice using the lens of the patient or family member, (3) be interested in more than one agenda item, (4) speak to multiple operational topics, (5) listen to other points of view and be empathetic, (6) connect with other advisors and staff, and (7) have a good sense of humor. Candidates with both positive and negative experiences are sought so that we can learn and improve from their experience [2].

To find advisors with these attributes, we ask providers to review their schedule and think about who they look forward to seeing or connect with on a personal level. This method has proven successful at producing candidates that have the attributes we seek. It is vital that the patients we recruit are able to see past their own personal experiences to understand broader objectives and how they fit into the bigger picture, enabling them to participate in a variety of projects and committees. There are no educational or specific skill requirements to become an advisor; the only requirement is that candidates must have experience as a patient or caregiver (family member) of a patient at BWH.

Recommended patients receive a letter notifying them that they have been nominated to be an advisor on a PFAC by their treating clinician. The project manager contacts potential advisors to see if they are interested and provides a brief description of PFACs and the role of patient/family advisors. The project manager emphasizes the importance of patient/family input to the hospital, describing the opportunities patient/family advisors have to contribute their expertise as a patient or caregiver to decisions and projects that will positively affect future patient care. Examples of past successful PFAC projects are shared to give a sense of the importance of the advisor role within the hospital and the appreciation hospital leadership has for PFAC contributions. The project manager reiterates that their clinician nominated them to the council to encourage the candidate to feel that their voice deserves to be heard.

Interested candidates are interviewed by phone by the team. Each candidate is asked the same questions: (1) How long have you been a patient in the clinic or unit?; (2) Describe your experiences in this clinic/service; and (3) Describe what works well and what could be improved in your care. During the interview, we listen to their personal narrative and their perspective on their care, which allows us to assess whether they have the attributes of a successful patient/family advisor. Candidate’s narratives illustrate how they would share their concerns, contribute to solutions, and if they have the ability to see beyond their own personal agenda. We also listen carefully for themes of tolerance, operational insight, empathy, and problem-solving capabilities. Interviews take about 15–20 minutes, depending on how many follow-up questions we have for the candidate and if they have questions for us.

After the phone interview, the team determines whether the candidate would be an appropriate patient/family advisor. If there are any concerns and more information is needed, the project manager reaches out to the staff and contacts the candidate to invite them for an in-person interview. Of the interviewed candidates, about 75% to 80% are invited to join. Candidates who are not chosen are generally unable to clearly articulate issues they see within the hospital/clinic, may have personal relationships with the staff (ie, friends with the physician), or cannot see pass their own issues and are inflexible in their thinking. Those not chosen receive a note thanking them for their time and interest. The candidates chosen to be advisors are on boarded through BWH volunteer services and must attend a 3-hour BWH volunteer orientation, be HIPAA compliant, and be cleared by occupational health before receiving their advisor ID badge and beginning service.

Council Launch

Once the advisors have been recruited and oriented, the council enters the launching stage, which lasts from the council’s first meeting until the 1-year anniversary. The first meeting agenda is designed to introduce staff and advisors to each other. Advisors each share their health care narratives and the staff shares their motivations for participating in the council. The council chair reviews the purpose and goals of the council.

During the first year, the council gains experience working together as a team. Council projects are initially chosen by the council chair and should be reasonably simple to accomplish and meaningful to advisors so that advisors recognize that their feedback is being heard and acted on. Example projects include creating clearer directional sign-age, assessing recliners for patient rooms, and providing feedback on patient handouts to ensure patient friendliness.

As the council advances, projects can be initiated by the advisors. This process is facilitated when an advisor is added as council co-chair, which usually occurs at the end of the first year. Projects often arise from similar concerns shared by advisors during the recruitment interview process.

Sustaining an Established Council

A council is considered established when it enters its second year and has named a patient advisor as a co-chair. Established councils have undertaken projects such as improving the layout of the whiteboards in patient rooms and providing feedback to staff on how to manage challenging patients. In addition, established councils may be tapped when service lines without a PFAC seek to gather advisor feedback for a project. For example, one of our established councils has provided feedback on two patient safety research projects.

Councils are sustained by continually engaging advisors in projects that are of value to them, both in their department and hospital-wide. Advisors should be given the opportunity to prioritize and set new council goals. One of the overarching goals for all our PFACs is to improve communication between patients and staff. Councils at this stage often participate in grand rounds or attend staff meetings to share their narratives, enabling providers to understand their perspective. The council can also be engaged in grant-funded research initiatives. Having PFACs involved in various projects allows advisors to bring their narratives to a wider audience and be a part of change from numerous avenues within the hospital.

Patient and Family Advisory Councils in Practice

BWH has 16 PFACs in various stages of growth. To illustrate the variety in council structure and function, we describe 3 PFACs below. Each has unique composition and goals based on the needs of service line leadership.

Shapiro Cardiovascular PFAC

The Shapiro Cardiovascular Center, a LEED silver-certified building and with private patient rooms that welcome family members to stay with their loved ones [4], opened in 2008. The chief nursing officer felt the care provided in this new space should promote and embody PFCC. With the assistance of the Center for Patients and Families, the associate chief nursing officer was charged with creating the Shapiro Cardiovascular PFAC. Launched in May 2011, this PFAC provides input to improve the patient experience for inpatient and ambulatory care housed in the Shapiro Center.

The Shapiro PFAC originally consisted of medical/surgical cardiac and heart transplant patients; renal transplant recipients and donors later joined. Initially, this council worked on patient/visitor guidelines for the inpatient units. As the council became more experienced, advisors interviewed nursing director candidates for cardiac surgery ICU and organized two PFCC nursing grand rounds. These grand rounds featured a panel of Shapiro advisors sharing their perspective of their hospital care and reflections on their healing process. This council has also provided feedback on hospital-wide projects, such as the refinement of a nursing fall prevention tool and the development of patient-informed measures of a successful surgery. As advisors became more experienced, they were recruited by the executive director to be part of other committees and research projects.

The Shapiro PFAC is one of the oldest councils at BWH, consisting of 12 advisors and 3 staff members, with most of the inaugural advisors remaining. Because the council chair has changed twice since 2011, this council does not have a formal advisor co-chair but the council remains a cohesive team as they work in partnership with the newest chair. To sustain this PFAC, leadership has consistently engaged the council in operational projects. For example, the associate chief nursing officer has suggested advisors be part of unit-based councils composed of staff nurses and educators who work to improve patient care within their unit. Advisors have also been invited to participate in staff and nursing director meetings to share their narratives and allow staff to reflect on the care they provide patients.

LGBTQ PFAC

In the fall of 2014, BWH held an educational Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) patient experience forum prompted by a complaint from the wife of a maternity patient that the care they received was not patient/family-centered. During this panel discussion, 4 LGBTQ patients described their care at BWH, including what went well and what their providers could have done better. There was an acknowledgement by a majority of providers in the audience that they did not receive training on inclusive care for LGBTQ patients and their families. The providers identified the need to be educated on LGBTQ issues and care concerns, and their desire to work towards creating a warm and inclusive environment that better serves LGBTQ patients. This organic request for education was met with enthusiasm from the panel participants and led to a commitment to form an LGBTQ PFAC at BWH.

The LGBTQ PFAC is co-chaired by the executive director of the Center for Patients and Families and a LGBTQ patient advisor who receives his care at BWH. It was important for this council to be co-led by an advisor from the beginning to acknowledge and validate LGBTQ experiences of care which had previously been marginalized. Because LGBTQ patients interact with all service lines at BWH, it made sense that a central operational leader with significant experience listening and responding to the patient voice co-leads the group. This council is composed of LGBTQ patients, their caregivers/partners/spouses, BWH LGBTQ staff that also receive healthcare from BWH, and LGBTQ academic stakeholders who provide historical contextualization to inform change.

The LGBTQ PFAC began the preparation phase in April 2015 and launched as a hospital-wide council in October 2015. This launch was widely publicized so that all BWH employees would know this council was created to elevate LGBTQ patients and caregivers into the mainstream hospital consciousness. The goals for this year are to partner with the existing LGBTQ employee group to create a standardized LGBTQ provider directory, educate staff on the healthcare needs of the community, and promote educational awareness, compassionate understanding, and improved care for transgender patients. As this council matures into the established stage, new projects will be taken on in line with the needs seen by members.

Women’s Health Council

The Women’s Health Council is a unique PFAC established in 2012. The council serves a population of trauma survivors cared for by the Coordinated Approach to Recovery and Empowerment (C.A.R.E.) clinic at BWH, also founded in 2012. Patients who receive care in this clinic have experienced violence and trauma, including domestic and sexual violence, child maltreatment, and human trafficking. Due to previous experience leading a PFAC, the C.A.R.E. Director understood the importance of patient input and engaged patients as advisors while forming the clinic.

The C.A.R.E. clinic serves both men and women but the majority of survivors served are female; thus, the patient advisors on its PFAC are all female. To recruit advisors, clinicians, and social workers at the clinic refer potential candidates to the C.A.R.E. Director, who then interviews them. The criteria for advisors for this council include being a female survivor of violence and trauma, being physically and mentally able to serve, and able to participate in a way that does not re-traumatize them. There are currently 14 advisors on the council with a goal to grow to 30 advisors. Experience has shown that members become busy with family, school and careers and may need to step away for short periods of time; thus, the council seeks to continually recruit to ensure robust membership.

Instead of the usual monthly scheduled meetings, this council holds “meetings on demand.” Advisors are polled via email to find a time in the near future that works for the group. The PFAC generally uses a web conferencing platform for their meetings and has an in-person meeting once or twice a year. Also unlike other councils, this council does not require their advisors to share their personal narratives; it is up to each advisor to decide what to share.

This council has accomplished numerous goals since its inception, including its first task of giving the C.A.R.E. clinic its name. The council has provided feedback on the development of the C.A.R.E. brochure and website and serves as key informants in all aspects of policy and procedures for the C.A.R.E. clinic. Additionally, they have provided input on how to create a safe environment for patients and screen patients to identify a victim of violence or human trafficking [5]. This council has been sustained by the strong community fostered by the director and projects led by the advisors, as each advisor has a vested interest in ensuring the clinic provides a safe environment for patients seeking care. This year, the council is hoping to host experts from the Boston Health Commission to share best practices in providing services to victims of abuse and violence.

Lessons Learned

The BWH Center for Patients and Families has encountered challenges when creating and sustaining PFACs, such as recruiting advisors from diverse ethnic, cultural, and economic backgrounds. Currently, our advisor population is primarily comprised of Caucasian patient/family members from middle and upper economic backgrounds, though it has increasingly diversified as the program has grown. We believe the lack of representation from other backgrounds is due to scheduling difficulties, the lack of payment for advisors, visibility of the PFAC program, and, potentially, cultural norms that promote deference to medical expertise. We have worked to increase PFAC diversity by asking providers to specifically seek out and nominate patients that will broaden our reach as a council.

Retaining and recruiting advisors after the PFACs have launched can also present a challenge. Some advisors have had to resign due to job demands, relocation, health issues, or the need to take care of family. To resolve this issue, we have asked PFAC chairs to continuously actively recruit advisors. By doing so, the councils gain new perspectives and ensure there are adequate number of advisors should a vacancy occur.

Sustaining PFACs once they are established requires time, effort, and commitment of leadership, advisors, and dedicated staff resources. The council needs to be continuously engaged in meaningful projects and feel that their participation is impactful and creates change. It is important that clinical leadership stays actively involved and attends all PFAC meetings. If there is a change in leadership as we experienced on our Shapiro PFAC, it is critical that the interim chair participates and supports the goal of the council. Regardless, leadership must show sustained enthusiasm for PFAC engagement and achievement.

Employing technology can also help sustain councils. Although we prefer in-person meetings, the option to attend meetings through online or phone conferencing should be made available to support advisors who are unable to attend in person. At this time, only one of our councils uses web conferencing, while several of our councils offer an option to call in via a conference line. The conference line has been beneficial in helping us retain and engage advisors who travel a significant distance to attend meetings.

We recognize that BWH has many resources available due to its status as a large, academic medical center in an urban center. Nonetheless, PFACs can play a vital role in hospitals no matter the setting, location, or size as long as there is buy in from hospital leadership. Although BWH has 16 PFACs, it is not necessary to have this many councils. Having one PFAC may be sufficient for smaller hospitals; the ideal number of councils depends on the size and complexity of the institution. Hospitals without a dedicated department like the Center for Patients and Families can create PFACs by partnering with volunteer services, patient engagement, or quality and safety departments. Existing departments with the capability to train advisors and provide meeting resources to support patient/family recruitment and engagement should be harnessed whenever possible. It is, however, important to have a dedicated staff member to serve as a point person for the advisors should they have any questions or concerns. Technology, such as web conferencing described above, can facilitate attendance by patient/family advisors who have limited time or resources and will be valuable for hospitals in a rural setting. The stages we have described are critical to the success of creating and sustaining a PFAC regardless of where they are developed and can be adapted to fit the unique needs and environments of any healthcare setting.

Conclusion

BWH’s Center for Patients and Families has created 16 PFACs since 2008, which are in various stages of development. Our PFACs are successful for many reasons, including a rigorous recruitment and interview process, leadership support, advisors’ commitment to their PFAC, and making modifications made based on lessons learned, as illustrated by the 3 PFACs discussed. We are able to sustain our councils by continually engagingadvisors, having leadership partner with advisors, setting feasible goals, and recruiting new advisors for a fresh perspective. PFACs promote patient- and family-centered care and can shift the model of care from a prescribed model to one that embraces collaboration with patients while advancing care delivery. As patient- and family-centered care advances, it is important that best practices for building and sustaining PFACs are developed and made available to ensure all hospitals have access to this valuable resource.

Corresponding author: Celene Wong, MHA, Center for Patients and Families, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis St., Boston, MA 02115, cwong3@partners.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. Accessed 6 Apr 2016 at www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf.

2. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care creating patient and family advisory councils. Oct 2010. Accessed 10 Jan 2016 at www.ipfcc.org/advance/Advisory_Councils.pdf.

3. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care core concepts. Dec 2010. Accessed 10 Jan 2016 at www.ipfcc.org/faq.html.

4. NBBJ. Caring to connect. 2016. Accessed 22 Feb 2016 at www.nbbj.com/work/brigham-and-womens-hospital-shapiro/.

5. Lewis-O’Connor A, Chadwick M. Engaging the voice of patients affected by gender-based violence: informing practice and policy. J Forensic Nurs 2015;11:240–9.

From the Center for Patients and Families (Dr. Fagan, Ms. Wong, Ms. Morrison, Ms. Carnie), and the Division of Women’s Health and Gender Biology (Dr. Lewis-O’Connor), Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe and illustrate the phases of creating, recruiting, launching, and sustaining a successful Patient and Family Advisory Council (PFAC) in a hospital setting.

- Method: Descriptive report.

- Results: There are 4 stages in creating and establishing a PFAC: council preparation, patient/family advisor recruitment, council launch, and sustaining an established council. Each stage poses challenges that need to be addressed in order to progress to the next stage. The ability for hospital leadership to authentically partner with patient and family advisors is key to maintaining and sustaining PFACs.

- Conclusion: The success of a PFAC is based on leadership support, advisors’ commitment to their PFAC, and the ability to sustain the council. PFACs can promote patient- and family-centered care and shift the model of care from a prescribed model to one that embraces partnerships with patients while advancing care delivery. As patient- and family-centered care advances, it is important that best practices and resources for building and sustaining PFACs are developed and made available to ensure all hospitals have access to this valuable resource.

Throughout the country, families, patients, and health care professionals are working together in new ways, including within patient and family advisory councils (PFACs). First established in the 1990s, PFACs became widespread after patient-centeredness was identified by the Institute of Medicine as one of the 6 aims of quality health care [1]. PFACs were created to institutionalize a partnership between hospital leadership, clinicians, patients, and families to improve care delivery. Through this partnership, PFACs facilitate the sharing of patient perspectives and input on hospital policies and programs; serve as a resource to providers; and promote relationships between staff, patients, and family members [2]. PFACs also play an important role in promoting patient- and family-centered care, ensuring that patient needs and values are at the center of the care delivery system.

The BWH Center for Patients and Families includes the executive director, a project manager, and a senior patient advisor, who together oversee the PFACs. The project manager provides logistical support and is available as concerns arise, working closely with the senior patient advisor to ensure patient/family advisors are acclimated to their role and all PFACs run smoothly. The senior patient advisor is a volunteer advisor and patient advocate with long term experience creating and sustaining PFACs and mentoring patient/family advisors. Her role as a mentor includes attending PFAC meetings to model skills and behaviors for other advisors and working with them to ensure they are comfortable in their PFAC. Her advocacy work includes listening to and helping to articulate lived patient/family experiences as compelling narratives, which can be shared with hospital leadership and used as exemplars to spur change. Together, the team recruits and trains patient/family advisors, support all phases of PFAC development, and represent the patient/family voice within the hospital.

In this article, we describe and illustrate the 4 stages of creating and sustaining a successful PFAC to provide guidance and lessons learned to organizations seeking to develop this valuable resource. These stages are: (1) council preparation, (2) patient/family advisor recruitment, (3) council launch, and (4) sustaining an established council.

Council Preparation

Preparation of the PFAC occurs once hospital or service line leadership has identified a need for and is committed to having a PFAC. Leadership contacts the executive director of the Center for Patients and Families to discuss the strategy and vision of the council. The executive director describes the attributes sought in an advisor and the core principles of patient- and family-centered care. This discussion includes recruitment methods, meeting logistics, and who will serve as council chair. The council chair should be in a leadership role and willing to champion the PFAC for their service line. The executive director discusses what is being planned with relevant clinicians and staff at a staff meeting in order to foster buy-in and involve them in the council recruitment process.

The BWH Center for Patients and Families has adapted Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care recommendations for PFAC logistics and structure [3]. Councils generally meet monthly for 90 minutes excluding August and December. As volunteers, our advisors receive no monetary compensation but receive complimentary parking and are often provided meals. Advisors are asked to commit to a 3-year term with the understanding that personal issues can arise and their commitment may change; after their term, they are welcome to continue. We recommend to leadership that PFACs be comprised of no more than 1 staff member to every 4 advisors. This ratio seeks to address any potential power imbalance and promotes a feeling of ownership of their council . The project manager works with leadership in creating council guidelines, including the council’s goals, expectations, and each member’s role.

Patient/Family Advisor Recruitment

We ask service line providers and staff to nominate patients and family members they believe would be suitable advisors. The attributes we look for in an advisor include their ability to: (1) share personal experiences in ways that professional and support staff can learn from, (2) see the big picture of a challenge or scenario and give advice using the lens of the patient or family member, (3) be interested in more than one agenda item, (4) speak to multiple operational topics, (5) listen to other points of view and be empathetic, (6) connect with other advisors and staff, and (7) have a good sense of humor. Candidates with both positive and negative experiences are sought so that we can learn and improve from their experience [2].

To find advisors with these attributes, we ask providers to review their schedule and think about who they look forward to seeing or connect with on a personal level. This method has proven successful at producing candidates that have the attributes we seek. It is vital that the patients we recruit are able to see past their own personal experiences to understand broader objectives and how they fit into the bigger picture, enabling them to participate in a variety of projects and committees. There are no educational or specific skill requirements to become an advisor; the only requirement is that candidates must have experience as a patient or caregiver (family member) of a patient at BWH.

Recommended patients receive a letter notifying them that they have been nominated to be an advisor on a PFAC by their treating clinician. The project manager contacts potential advisors to see if they are interested and provides a brief description of PFACs and the role of patient/family advisors. The project manager emphasizes the importance of patient/family input to the hospital, describing the opportunities patient/family advisors have to contribute their expertise as a patient or caregiver to decisions and projects that will positively affect future patient care. Examples of past successful PFAC projects are shared to give a sense of the importance of the advisor role within the hospital and the appreciation hospital leadership has for PFAC contributions. The project manager reiterates that their clinician nominated them to the council to encourage the candidate to feel that their voice deserves to be heard.

Interested candidates are interviewed by phone by the team. Each candidate is asked the same questions: (1) How long have you been a patient in the clinic or unit?; (2) Describe your experiences in this clinic/service; and (3) Describe what works well and what could be improved in your care. During the interview, we listen to their personal narrative and their perspective on their care, which allows us to assess whether they have the attributes of a successful patient/family advisor. Candidate’s narratives illustrate how they would share their concerns, contribute to solutions, and if they have the ability to see beyond their own personal agenda. We also listen carefully for themes of tolerance, operational insight, empathy, and problem-solving capabilities. Interviews take about 15–20 minutes, depending on how many follow-up questions we have for the candidate and if they have questions for us.

After the phone interview, the team determines whether the candidate would be an appropriate patient/family advisor. If there are any concerns and more information is needed, the project manager reaches out to the staff and contacts the candidate to invite them for an in-person interview. Of the interviewed candidates, about 75% to 80% are invited to join. Candidates who are not chosen are generally unable to clearly articulate issues they see within the hospital/clinic, may have personal relationships with the staff (ie, friends with the physician), or cannot see pass their own issues and are inflexible in their thinking. Those not chosen receive a note thanking them for their time and interest. The candidates chosen to be advisors are on boarded through BWH volunteer services and must attend a 3-hour BWH volunteer orientation, be HIPAA compliant, and be cleared by occupational health before receiving their advisor ID badge and beginning service.

Council Launch

Once the advisors have been recruited and oriented, the council enters the launching stage, which lasts from the council’s first meeting until the 1-year anniversary. The first meeting agenda is designed to introduce staff and advisors to each other. Advisors each share their health care narratives and the staff shares their motivations for participating in the council. The council chair reviews the purpose and goals of the council.

During the first year, the council gains experience working together as a team. Council projects are initially chosen by the council chair and should be reasonably simple to accomplish and meaningful to advisors so that advisors recognize that their feedback is being heard and acted on. Example projects include creating clearer directional sign-age, assessing recliners for patient rooms, and providing feedback on patient handouts to ensure patient friendliness.

As the council advances, projects can be initiated by the advisors. This process is facilitated when an advisor is added as council co-chair, which usually occurs at the end of the first year. Projects often arise from similar concerns shared by advisors during the recruitment interview process.

Sustaining an Established Council

A council is considered established when it enters its second year and has named a patient advisor as a co-chair. Established councils have undertaken projects such as improving the layout of the whiteboards in patient rooms and providing feedback to staff on how to manage challenging patients. In addition, established councils may be tapped when service lines without a PFAC seek to gather advisor feedback for a project. For example, one of our established councils has provided feedback on two patient safety research projects.

Councils are sustained by continually engaging advisors in projects that are of value to them, both in their department and hospital-wide. Advisors should be given the opportunity to prioritize and set new council goals. One of the overarching goals for all our PFACs is to improve communication between patients and staff. Councils at this stage often participate in grand rounds or attend staff meetings to share their narratives, enabling providers to understand their perspective. The council can also be engaged in grant-funded research initiatives. Having PFACs involved in various projects allows advisors to bring their narratives to a wider audience and be a part of change from numerous avenues within the hospital.

Patient and Family Advisory Councils in Practice

BWH has 16 PFACs in various stages of growth. To illustrate the variety in council structure and function, we describe 3 PFACs below. Each has unique composition and goals based on the needs of service line leadership.

Shapiro Cardiovascular PFAC

The Shapiro Cardiovascular Center, a LEED silver-certified building and with private patient rooms that welcome family members to stay with their loved ones [4], opened in 2008. The chief nursing officer felt the care provided in this new space should promote and embody PFCC. With the assistance of the Center for Patients and Families, the associate chief nursing officer was charged with creating the Shapiro Cardiovascular PFAC. Launched in May 2011, this PFAC provides input to improve the patient experience for inpatient and ambulatory care housed in the Shapiro Center.

The Shapiro PFAC originally consisted of medical/surgical cardiac and heart transplant patients; renal transplant recipients and donors later joined. Initially, this council worked on patient/visitor guidelines for the inpatient units. As the council became more experienced, advisors interviewed nursing director candidates for cardiac surgery ICU and organized two PFCC nursing grand rounds. These grand rounds featured a panel of Shapiro advisors sharing their perspective of their hospital care and reflections on their healing process. This council has also provided feedback on hospital-wide projects, such as the refinement of a nursing fall prevention tool and the development of patient-informed measures of a successful surgery. As advisors became more experienced, they were recruited by the executive director to be part of other committees and research projects.

The Shapiro PFAC is one of the oldest councils at BWH, consisting of 12 advisors and 3 staff members, with most of the inaugural advisors remaining. Because the council chair has changed twice since 2011, this council does not have a formal advisor co-chair but the council remains a cohesive team as they work in partnership with the newest chair. To sustain this PFAC, leadership has consistently engaged the council in operational projects. For example, the associate chief nursing officer has suggested advisors be part of unit-based councils composed of staff nurses and educators who work to improve patient care within their unit. Advisors have also been invited to participate in staff and nursing director meetings to share their narratives and allow staff to reflect on the care they provide patients.

LGBTQ PFAC

In the fall of 2014, BWH held an educational Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) patient experience forum prompted by a complaint from the wife of a maternity patient that the care they received was not patient/family-centered. During this panel discussion, 4 LGBTQ patients described their care at BWH, including what went well and what their providers could have done better. There was an acknowledgement by a majority of providers in the audience that they did not receive training on inclusive care for LGBTQ patients and their families. The providers identified the need to be educated on LGBTQ issues and care concerns, and their desire to work towards creating a warm and inclusive environment that better serves LGBTQ patients. This organic request for education was met with enthusiasm from the panel participants and led to a commitment to form an LGBTQ PFAC at BWH.

The LGBTQ PFAC is co-chaired by the executive director of the Center for Patients and Families and a LGBTQ patient advisor who receives his care at BWH. It was important for this council to be co-led by an advisor from the beginning to acknowledge and validate LGBTQ experiences of care which had previously been marginalized. Because LGBTQ patients interact with all service lines at BWH, it made sense that a central operational leader with significant experience listening and responding to the patient voice co-leads the group. This council is composed of LGBTQ patients, their caregivers/partners/spouses, BWH LGBTQ staff that also receive healthcare from BWH, and LGBTQ academic stakeholders who provide historical contextualization to inform change.

The LGBTQ PFAC began the preparation phase in April 2015 and launched as a hospital-wide council in October 2015. This launch was widely publicized so that all BWH employees would know this council was created to elevate LGBTQ patients and caregivers into the mainstream hospital consciousness. The goals for this year are to partner with the existing LGBTQ employee group to create a standardized LGBTQ provider directory, educate staff on the healthcare needs of the community, and promote educational awareness, compassionate understanding, and improved care for transgender patients. As this council matures into the established stage, new projects will be taken on in line with the needs seen by members.

Women’s Health Council

The Women’s Health Council is a unique PFAC established in 2012. The council serves a population of trauma survivors cared for by the Coordinated Approach to Recovery and Empowerment (C.A.R.E.) clinic at BWH, also founded in 2012. Patients who receive care in this clinic have experienced violence and trauma, including domestic and sexual violence, child maltreatment, and human trafficking. Due to previous experience leading a PFAC, the C.A.R.E. Director understood the importance of patient input and engaged patients as advisors while forming the clinic.

The C.A.R.E. clinic serves both men and women but the majority of survivors served are female; thus, the patient advisors on its PFAC are all female. To recruit advisors, clinicians, and social workers at the clinic refer potential candidates to the C.A.R.E. Director, who then interviews them. The criteria for advisors for this council include being a female survivor of violence and trauma, being physically and mentally able to serve, and able to participate in a way that does not re-traumatize them. There are currently 14 advisors on the council with a goal to grow to 30 advisors. Experience has shown that members become busy with family, school and careers and may need to step away for short periods of time; thus, the council seeks to continually recruit to ensure robust membership.

Instead of the usual monthly scheduled meetings, this council holds “meetings on demand.” Advisors are polled via email to find a time in the near future that works for the group. The PFAC generally uses a web conferencing platform for their meetings and has an in-person meeting once or twice a year. Also unlike other councils, this council does not require their advisors to share their personal narratives; it is up to each advisor to decide what to share.

This council has accomplished numerous goals since its inception, including its first task of giving the C.A.R.E. clinic its name. The council has provided feedback on the development of the C.A.R.E. brochure and website and serves as key informants in all aspects of policy and procedures for the C.A.R.E. clinic. Additionally, they have provided input on how to create a safe environment for patients and screen patients to identify a victim of violence or human trafficking [5]. This council has been sustained by the strong community fostered by the director and projects led by the advisors, as each advisor has a vested interest in ensuring the clinic provides a safe environment for patients seeking care. This year, the council is hoping to host experts from the Boston Health Commission to share best practices in providing services to victims of abuse and violence.

Lessons Learned

The BWH Center for Patients and Families has encountered challenges when creating and sustaining PFACs, such as recruiting advisors from diverse ethnic, cultural, and economic backgrounds. Currently, our advisor population is primarily comprised of Caucasian patient/family members from middle and upper economic backgrounds, though it has increasingly diversified as the program has grown. We believe the lack of representation from other backgrounds is due to scheduling difficulties, the lack of payment for advisors, visibility of the PFAC program, and, potentially, cultural norms that promote deference to medical expertise. We have worked to increase PFAC diversity by asking providers to specifically seek out and nominate patients that will broaden our reach as a council.

Retaining and recruiting advisors after the PFACs have launched can also present a challenge. Some advisors have had to resign due to job demands, relocation, health issues, or the need to take care of family. To resolve this issue, we have asked PFAC chairs to continuously actively recruit advisors. By doing so, the councils gain new perspectives and ensure there are adequate number of advisors should a vacancy occur.

Sustaining PFACs once they are established requires time, effort, and commitment of leadership, advisors, and dedicated staff resources. The council needs to be continuously engaged in meaningful projects and feel that their participation is impactful and creates change. It is important that clinical leadership stays actively involved and attends all PFAC meetings. If there is a change in leadership as we experienced on our Shapiro PFAC, it is critical that the interim chair participates and supports the goal of the council. Regardless, leadership must show sustained enthusiasm for PFAC engagement and achievement.

Employing technology can also help sustain councils. Although we prefer in-person meetings, the option to attend meetings through online or phone conferencing should be made available to support advisors who are unable to attend in person. At this time, only one of our councils uses web conferencing, while several of our councils offer an option to call in via a conference line. The conference line has been beneficial in helping us retain and engage advisors who travel a significant distance to attend meetings.

We recognize that BWH has many resources available due to its status as a large, academic medical center in an urban center. Nonetheless, PFACs can play a vital role in hospitals no matter the setting, location, or size as long as there is buy in from hospital leadership. Although BWH has 16 PFACs, it is not necessary to have this many councils. Having one PFAC may be sufficient for smaller hospitals; the ideal number of councils depends on the size and complexity of the institution. Hospitals without a dedicated department like the Center for Patients and Families can create PFACs by partnering with volunteer services, patient engagement, or quality and safety departments. Existing departments with the capability to train advisors and provide meeting resources to support patient/family recruitment and engagement should be harnessed whenever possible. It is, however, important to have a dedicated staff member to serve as a point person for the advisors should they have any questions or concerns. Technology, such as web conferencing described above, can facilitate attendance by patient/family advisors who have limited time or resources and will be valuable for hospitals in a rural setting. The stages we have described are critical to the success of creating and sustaining a PFAC regardless of where they are developed and can be adapted to fit the unique needs and environments of any healthcare setting.

Conclusion

BWH’s Center for Patients and Families has created 16 PFACs since 2008, which are in various stages of development. Our PFACs are successful for many reasons, including a rigorous recruitment and interview process, leadership support, advisors’ commitment to their PFAC, and making modifications made based on lessons learned, as illustrated by the 3 PFACs discussed. We are able to sustain our councils by continually engagingadvisors, having leadership partner with advisors, setting feasible goals, and recruiting new advisors for a fresh perspective. PFACs promote patient- and family-centered care and can shift the model of care from a prescribed model to one that embraces collaboration with patients while advancing care delivery. As patient- and family-centered care advances, it is important that best practices for building and sustaining PFACs are developed and made available to ensure all hospitals have access to this valuable resource.

Corresponding author: Celene Wong, MHA, Center for Patients and Families, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis St., Boston, MA 02115, cwong3@partners.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Center for Patients and Families (Dr. Fagan, Ms. Wong, Ms. Morrison, Ms. Carnie), and the Division of Women’s Health and Gender Biology (Dr. Lewis-O’Connor), Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe and illustrate the phases of creating, recruiting, launching, and sustaining a successful Patient and Family Advisory Council (PFAC) in a hospital setting.

- Method: Descriptive report.

- Results: There are 4 stages in creating and establishing a PFAC: council preparation, patient/family advisor recruitment, council launch, and sustaining an established council. Each stage poses challenges that need to be addressed in order to progress to the next stage. The ability for hospital leadership to authentically partner with patient and family advisors is key to maintaining and sustaining PFACs.

- Conclusion: The success of a PFAC is based on leadership support, advisors’ commitment to their PFAC, and the ability to sustain the council. PFACs can promote patient- and family-centered care and shift the model of care from a prescribed model to one that embraces partnerships with patients while advancing care delivery. As patient- and family-centered care advances, it is important that best practices and resources for building and sustaining PFACs are developed and made available to ensure all hospitals have access to this valuable resource.

Throughout the country, families, patients, and health care professionals are working together in new ways, including within patient and family advisory councils (PFACs). First established in the 1990s, PFACs became widespread after patient-centeredness was identified by the Institute of Medicine as one of the 6 aims of quality health care [1]. PFACs were created to institutionalize a partnership between hospital leadership, clinicians, patients, and families to improve care delivery. Through this partnership, PFACs facilitate the sharing of patient perspectives and input on hospital policies and programs; serve as a resource to providers; and promote relationships between staff, patients, and family members [2]. PFACs also play an important role in promoting patient- and family-centered care, ensuring that patient needs and values are at the center of the care delivery system.

The BWH Center for Patients and Families includes the executive director, a project manager, and a senior patient advisor, who together oversee the PFACs. The project manager provides logistical support and is available as concerns arise, working closely with the senior patient advisor to ensure patient/family advisors are acclimated to their role and all PFACs run smoothly. The senior patient advisor is a volunteer advisor and patient advocate with long term experience creating and sustaining PFACs and mentoring patient/family advisors. Her role as a mentor includes attending PFAC meetings to model skills and behaviors for other advisors and working with them to ensure they are comfortable in their PFAC. Her advocacy work includes listening to and helping to articulate lived patient/family experiences as compelling narratives, which can be shared with hospital leadership and used as exemplars to spur change. Together, the team recruits and trains patient/family advisors, support all phases of PFAC development, and represent the patient/family voice within the hospital.

In this article, we describe and illustrate the 4 stages of creating and sustaining a successful PFAC to provide guidance and lessons learned to organizations seeking to develop this valuable resource. These stages are: (1) council preparation, (2) patient/family advisor recruitment, (3) council launch, and (4) sustaining an established council.

Council Preparation

Preparation of the PFAC occurs once hospital or service line leadership has identified a need for and is committed to having a PFAC. Leadership contacts the executive director of the Center for Patients and Families to discuss the strategy and vision of the council. The executive director describes the attributes sought in an advisor and the core principles of patient- and family-centered care. This discussion includes recruitment methods, meeting logistics, and who will serve as council chair. The council chair should be in a leadership role and willing to champion the PFAC for their service line. The executive director discusses what is being planned with relevant clinicians and staff at a staff meeting in order to foster buy-in and involve them in the council recruitment process.

The BWH Center for Patients and Families has adapted Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care recommendations for PFAC logistics and structure [3]. Councils generally meet monthly for 90 minutes excluding August and December. As volunteers, our advisors receive no monetary compensation but receive complimentary parking and are often provided meals. Advisors are asked to commit to a 3-year term with the understanding that personal issues can arise and their commitment may change; after their term, they are welcome to continue. We recommend to leadership that PFACs be comprised of no more than 1 staff member to every 4 advisors. This ratio seeks to address any potential power imbalance and promotes a feeling of ownership of their council . The project manager works with leadership in creating council guidelines, including the council’s goals, expectations, and each member’s role.

Patient/Family Advisor Recruitment

We ask service line providers and staff to nominate patients and family members they believe would be suitable advisors. The attributes we look for in an advisor include their ability to: (1) share personal experiences in ways that professional and support staff can learn from, (2) see the big picture of a challenge or scenario and give advice using the lens of the patient or family member, (3) be interested in more than one agenda item, (4) speak to multiple operational topics, (5) listen to other points of view and be empathetic, (6) connect with other advisors and staff, and (7) have a good sense of humor. Candidates with both positive and negative experiences are sought so that we can learn and improve from their experience [2].

To find advisors with these attributes, we ask providers to review their schedule and think about who they look forward to seeing or connect with on a personal level. This method has proven successful at producing candidates that have the attributes we seek. It is vital that the patients we recruit are able to see past their own personal experiences to understand broader objectives and how they fit into the bigger picture, enabling them to participate in a variety of projects and committees. There are no educational or specific skill requirements to become an advisor; the only requirement is that candidates must have experience as a patient or caregiver (family member) of a patient at BWH.

Recommended patients receive a letter notifying them that they have been nominated to be an advisor on a PFAC by their treating clinician. The project manager contacts potential advisors to see if they are interested and provides a brief description of PFACs and the role of patient/family advisors. The project manager emphasizes the importance of patient/family input to the hospital, describing the opportunities patient/family advisors have to contribute their expertise as a patient or caregiver to decisions and projects that will positively affect future patient care. Examples of past successful PFAC projects are shared to give a sense of the importance of the advisor role within the hospital and the appreciation hospital leadership has for PFAC contributions. The project manager reiterates that their clinician nominated them to the council to encourage the candidate to feel that their voice deserves to be heard.

Interested candidates are interviewed by phone by the team. Each candidate is asked the same questions: (1) How long have you been a patient in the clinic or unit?; (2) Describe your experiences in this clinic/service; and (3) Describe what works well and what could be improved in your care. During the interview, we listen to their personal narrative and their perspective on their care, which allows us to assess whether they have the attributes of a successful patient/family advisor. Candidate’s narratives illustrate how they would share their concerns, contribute to solutions, and if they have the ability to see beyond their own personal agenda. We also listen carefully for themes of tolerance, operational insight, empathy, and problem-solving capabilities. Interviews take about 15–20 minutes, depending on how many follow-up questions we have for the candidate and if they have questions for us.

After the phone interview, the team determines whether the candidate would be an appropriate patient/family advisor. If there are any concerns and more information is needed, the project manager reaches out to the staff and contacts the candidate to invite them for an in-person interview. Of the interviewed candidates, about 75% to 80% are invited to join. Candidates who are not chosen are generally unable to clearly articulate issues they see within the hospital/clinic, may have personal relationships with the staff (ie, friends with the physician), or cannot see pass their own issues and are inflexible in their thinking. Those not chosen receive a note thanking them for their time and interest. The candidates chosen to be advisors are on boarded through BWH volunteer services and must attend a 3-hour BWH volunteer orientation, be HIPAA compliant, and be cleared by occupational health before receiving their advisor ID badge and beginning service.

Council Launch

Once the advisors have been recruited and oriented, the council enters the launching stage, which lasts from the council’s first meeting until the 1-year anniversary. The first meeting agenda is designed to introduce staff and advisors to each other. Advisors each share their health care narratives and the staff shares their motivations for participating in the council. The council chair reviews the purpose and goals of the council.

During the first year, the council gains experience working together as a team. Council projects are initially chosen by the council chair and should be reasonably simple to accomplish and meaningful to advisors so that advisors recognize that their feedback is being heard and acted on. Example projects include creating clearer directional sign-age, assessing recliners for patient rooms, and providing feedback on patient handouts to ensure patient friendliness.

As the council advances, projects can be initiated by the advisors. This process is facilitated when an advisor is added as council co-chair, which usually occurs at the end of the first year. Projects often arise from similar concerns shared by advisors during the recruitment interview process.

Sustaining an Established Council

A council is considered established when it enters its second year and has named a patient advisor as a co-chair. Established councils have undertaken projects such as improving the layout of the whiteboards in patient rooms and providing feedback to staff on how to manage challenging patients. In addition, established councils may be tapped when service lines without a PFAC seek to gather advisor feedback for a project. For example, one of our established councils has provided feedback on two patient safety research projects.

Councils are sustained by continually engaging advisors in projects that are of value to them, both in their department and hospital-wide. Advisors should be given the opportunity to prioritize and set new council goals. One of the overarching goals for all our PFACs is to improve communication between patients and staff. Councils at this stage often participate in grand rounds or attend staff meetings to share their narratives, enabling providers to understand their perspective. The council can also be engaged in grant-funded research initiatives. Having PFACs involved in various projects allows advisors to bring their narratives to a wider audience and be a part of change from numerous avenues within the hospital.

Patient and Family Advisory Councils in Practice

BWH has 16 PFACs in various stages of growth. To illustrate the variety in council structure and function, we describe 3 PFACs below. Each has unique composition and goals based on the needs of service line leadership.

Shapiro Cardiovascular PFAC

The Shapiro Cardiovascular Center, a LEED silver-certified building and with private patient rooms that welcome family members to stay with their loved ones [4], opened in 2008. The chief nursing officer felt the care provided in this new space should promote and embody PFCC. With the assistance of the Center for Patients and Families, the associate chief nursing officer was charged with creating the Shapiro Cardiovascular PFAC. Launched in May 2011, this PFAC provides input to improve the patient experience for inpatient and ambulatory care housed in the Shapiro Center.

The Shapiro PFAC originally consisted of medical/surgical cardiac and heart transplant patients; renal transplant recipients and donors later joined. Initially, this council worked on patient/visitor guidelines for the inpatient units. As the council became more experienced, advisors interviewed nursing director candidates for cardiac surgery ICU and organized two PFCC nursing grand rounds. These grand rounds featured a panel of Shapiro advisors sharing their perspective of their hospital care and reflections on their healing process. This council has also provided feedback on hospital-wide projects, such as the refinement of a nursing fall prevention tool and the development of patient-informed measures of a successful surgery. As advisors became more experienced, they were recruited by the executive director to be part of other committees and research projects.

The Shapiro PFAC is one of the oldest councils at BWH, consisting of 12 advisors and 3 staff members, with most of the inaugural advisors remaining. Because the council chair has changed twice since 2011, this council does not have a formal advisor co-chair but the council remains a cohesive team as they work in partnership with the newest chair. To sustain this PFAC, leadership has consistently engaged the council in operational projects. For example, the associate chief nursing officer has suggested advisors be part of unit-based councils composed of staff nurses and educators who work to improve patient care within their unit. Advisors have also been invited to participate in staff and nursing director meetings to share their narratives and allow staff to reflect on the care they provide patients.

LGBTQ PFAC

In the fall of 2014, BWH held an educational Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) patient experience forum prompted by a complaint from the wife of a maternity patient that the care they received was not patient/family-centered. During this panel discussion, 4 LGBTQ patients described their care at BWH, including what went well and what their providers could have done better. There was an acknowledgement by a majority of providers in the audience that they did not receive training on inclusive care for LGBTQ patients and their families. The providers identified the need to be educated on LGBTQ issues and care concerns, and their desire to work towards creating a warm and inclusive environment that better serves LGBTQ patients. This organic request for education was met with enthusiasm from the panel participants and led to a commitment to form an LGBTQ PFAC at BWH.

The LGBTQ PFAC is co-chaired by the executive director of the Center for Patients and Families and a LGBTQ patient advisor who receives his care at BWH. It was important for this council to be co-led by an advisor from the beginning to acknowledge and validate LGBTQ experiences of care which had previously been marginalized. Because LGBTQ patients interact with all service lines at BWH, it made sense that a central operational leader with significant experience listening and responding to the patient voice co-leads the group. This council is composed of LGBTQ patients, their caregivers/partners/spouses, BWH LGBTQ staff that also receive healthcare from BWH, and LGBTQ academic stakeholders who provide historical contextualization to inform change.

The LGBTQ PFAC began the preparation phase in April 2015 and launched as a hospital-wide council in October 2015. This launch was widely publicized so that all BWH employees would know this council was created to elevate LGBTQ patients and caregivers into the mainstream hospital consciousness. The goals for this year are to partner with the existing LGBTQ employee group to create a standardized LGBTQ provider directory, educate staff on the healthcare needs of the community, and promote educational awareness, compassionate understanding, and improved care for transgender patients. As this council matures into the established stage, new projects will be taken on in line with the needs seen by members.

Women’s Health Council

The Women’s Health Council is a unique PFAC established in 2012. The council serves a population of trauma survivors cared for by the Coordinated Approach to Recovery and Empowerment (C.A.R.E.) clinic at BWH, also founded in 2012. Patients who receive care in this clinic have experienced violence and trauma, including domestic and sexual violence, child maltreatment, and human trafficking. Due to previous experience leading a PFAC, the C.A.R.E. Director understood the importance of patient input and engaged patients as advisors while forming the clinic.

The C.A.R.E. clinic serves both men and women but the majority of survivors served are female; thus, the patient advisors on its PFAC are all female. To recruit advisors, clinicians, and social workers at the clinic refer potential candidates to the C.A.R.E. Director, who then interviews them. The criteria for advisors for this council include being a female survivor of violence and trauma, being physically and mentally able to serve, and able to participate in a way that does not re-traumatize them. There are currently 14 advisors on the council with a goal to grow to 30 advisors. Experience has shown that members become busy with family, school and careers and may need to step away for short periods of time; thus, the council seeks to continually recruit to ensure robust membership.

Instead of the usual monthly scheduled meetings, this council holds “meetings on demand.” Advisors are polled via email to find a time in the near future that works for the group. The PFAC generally uses a web conferencing platform for their meetings and has an in-person meeting once or twice a year. Also unlike other councils, this council does not require their advisors to share their personal narratives; it is up to each advisor to decide what to share.

This council has accomplished numerous goals since its inception, including its first task of giving the C.A.R.E. clinic its name. The council has provided feedback on the development of the C.A.R.E. brochure and website and serves as key informants in all aspects of policy and procedures for the C.A.R.E. clinic. Additionally, they have provided input on how to create a safe environment for patients and screen patients to identify a victim of violence or human trafficking [5]. This council has been sustained by the strong community fostered by the director and projects led by the advisors, as each advisor has a vested interest in ensuring the clinic provides a safe environment for patients seeking care. This year, the council is hoping to host experts from the Boston Health Commission to share best practices in providing services to victims of abuse and violence.

Lessons Learned

The BWH Center for Patients and Families has encountered challenges when creating and sustaining PFACs, such as recruiting advisors from diverse ethnic, cultural, and economic backgrounds. Currently, our advisor population is primarily comprised of Caucasian patient/family members from middle and upper economic backgrounds, though it has increasingly diversified as the program has grown. We believe the lack of representation from other backgrounds is due to scheduling difficulties, the lack of payment for advisors, visibility of the PFAC program, and, potentially, cultural norms that promote deference to medical expertise. We have worked to increase PFAC diversity by asking providers to specifically seek out and nominate patients that will broaden our reach as a council.

Retaining and recruiting advisors after the PFACs have launched can also present a challenge. Some advisors have had to resign due to job demands, relocation, health issues, or the need to take care of family. To resolve this issue, we have asked PFAC chairs to continuously actively recruit advisors. By doing so, the councils gain new perspectives and ensure there are adequate number of advisors should a vacancy occur.

Sustaining PFACs once they are established requires time, effort, and commitment of leadership, advisors, and dedicated staff resources. The council needs to be continuously engaged in meaningful projects and feel that their participation is impactful and creates change. It is important that clinical leadership stays actively involved and attends all PFAC meetings. If there is a change in leadership as we experienced on our Shapiro PFAC, it is critical that the interim chair participates and supports the goal of the council. Regardless, leadership must show sustained enthusiasm for PFAC engagement and achievement.

Employing technology can also help sustain councils. Although we prefer in-person meetings, the option to attend meetings through online or phone conferencing should be made available to support advisors who are unable to attend in person. At this time, only one of our councils uses web conferencing, while several of our councils offer an option to call in via a conference line. The conference line has been beneficial in helping us retain and engage advisors who travel a significant distance to attend meetings.

We recognize that BWH has many resources available due to its status as a large, academic medical center in an urban center. Nonetheless, PFACs can play a vital role in hospitals no matter the setting, location, or size as long as there is buy in from hospital leadership. Although BWH has 16 PFACs, it is not necessary to have this many councils. Having one PFAC may be sufficient for smaller hospitals; the ideal number of councils depends on the size and complexity of the institution. Hospitals without a dedicated department like the Center for Patients and Families can create PFACs by partnering with volunteer services, patient engagement, or quality and safety departments. Existing departments with the capability to train advisors and provide meeting resources to support patient/family recruitment and engagement should be harnessed whenever possible. It is, however, important to have a dedicated staff member to serve as a point person for the advisors should they have any questions or concerns. Technology, such as web conferencing described above, can facilitate attendance by patient/family advisors who have limited time or resources and will be valuable for hospitals in a rural setting. The stages we have described are critical to the success of creating and sustaining a PFAC regardless of where they are developed and can be adapted to fit the unique needs and environments of any healthcare setting.

Conclusion

BWH’s Center for Patients and Families has created 16 PFACs since 2008, which are in various stages of development. Our PFACs are successful for many reasons, including a rigorous recruitment and interview process, leadership support, advisors’ commitment to their PFAC, and making modifications made based on lessons learned, as illustrated by the 3 PFACs discussed. We are able to sustain our councils by continually engagingadvisors, having leadership partner with advisors, setting feasible goals, and recruiting new advisors for a fresh perspective. PFACs promote patient- and family-centered care and can shift the model of care from a prescribed model to one that embraces collaboration with patients while advancing care delivery. As patient- and family-centered care advances, it is important that best practices for building and sustaining PFACs are developed and made available to ensure all hospitals have access to this valuable resource.

Corresponding author: Celene Wong, MHA, Center for Patients and Families, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis St., Boston, MA 02115, cwong3@partners.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. Accessed 6 Apr 2016 at www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf.

2. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care creating patient and family advisory councils. Oct 2010. Accessed 10 Jan 2016 at www.ipfcc.org/advance/Advisory_Councils.pdf.

3. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care core concepts. Dec 2010. Accessed 10 Jan 2016 at www.ipfcc.org/faq.html.

4. NBBJ. Caring to connect. 2016. Accessed 22 Feb 2016 at www.nbbj.com/work/brigham-and-womens-hospital-shapiro/.

5. Lewis-O’Connor A, Chadwick M. Engaging the voice of patients affected by gender-based violence: informing practice and policy. J Forensic Nurs 2015;11:240–9.

1. Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. Accessed 6 Apr 2016 at www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf.

2. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care creating patient and family advisory councils. Oct 2010. Accessed 10 Jan 2016 at www.ipfcc.org/advance/Advisory_Councils.pdf.

3. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care core concepts. Dec 2010. Accessed 10 Jan 2016 at www.ipfcc.org/faq.html.

4. NBBJ. Caring to connect. 2016. Accessed 22 Feb 2016 at www.nbbj.com/work/brigham-and-womens-hospital-shapiro/.

5. Lewis-O’Connor A, Chadwick M. Engaging the voice of patients affected by gender-based violence: informing practice and policy. J Forensic Nurs 2015;11:240–9.