User login

CE/CME No: CR-1305

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Differentiate between gastroesophageal reflux and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GER and GERD, respectively) in the pediatric patient, including symptomatology and risk factors.

• Explain typical and atypical presentations of GERD as factors in the differential diagnosis.

• Describe diagnostic testing options for GERD and their appropriate use in infants and children with suspected GERD.

• Discuss age-appropriate strategies to reduce the symptoms of GERD in children, including lifestyle changes and pharmacologic and surgical options.

FACULTY

Ellen D. Mandel is Clinical Associate Professor in the Pace University Physician Assistant Program in New York City, and Associate Professor in the Physician Assistant Program at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey. Claudia Ashforth and Kristine Daugherty are students in the Pace University Lenox Hill Hospital Physician Assistant Program.

The authors have no significant financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

As with US adults, infants and children appear to be at increased risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Lacking a cardinal symptom in children and often linked with confounding extra-esophageal symptoms, pediatric GERD challenges the primary care clinician to make an early diagnosis, preventing progressive damage and possible complications. Management begins with conservative lifestyle changes; pharmacologic and surgical options are reserved for specific pediatric patients.

Traditionally, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been viewed as an adult disease, but it is now recognized as a disorder that also occurs in children. A teenager with heartburn, a child with complaints of chest pain, and a coughing infant refusing to feed may all be experiencing it. Review of the literature reveals an increased incidence of GERD in both adults and children, making it one of the five most common gastrointestinal (GI) conditions in the United States.1

US pediatric hospitalization rates associated with GERD significantly increased from 1995 to 2000, accounting for 4% of these admissions.1 In a 2009 review of ICD-9 codes in a large claims database, GERD was diagnosed in 12.3% of North American infants and in 1% of other pediatric age-groups.2,3 In another recent study in which pediatric endoscopy data from 1999 to 2002 were analyzed, 9.5% of children age 1 year and 7.6% of children age 2 had erosive esophagitis.4

It is unclear whether the increased frequency in diagnosis of GERD should be attributed to improved diagnostic strategies or to an actual increase in disease prevalence.1 In any event, a timely diagnosis of GERD is essential to allow for appropriate intervention and early symptom management to reduce the risk for complications.

Overall, GERD is primarily a Western disease, affecting an estimated 10% to 15% of this geographic population. It is associated with obesity, recent dietary trends, and other causes.5 Prevalence of GERD in the general population has been shown to vary across ethnic groups. In the US, persons of Hispanic descent are more likely to be affected than whites, with symptoms of GERD least common among Asian-Americans.5

Since pediatric GERD is seen in primary care settings in the same rising numbers as associated hospital admissions, clinicians who provide primary care must be aware of its contributing factors, treatment modalities that are most effective in reducing symptoms, and strategies to prevent this disease. Treatment choices vary according to patient age-groups: infants (younger than 1 year), children ages 1 to 11 years, and adolescents, 12 to 18.

DISTINGUISHING GERD FROM GER

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the term used to describe the passage of gastric contents, including stomach acid, fluids, and food, into the esophagus, with or without regurgitation or vomiting.6 GER is a normal, common physiologic process among infants, in whom frequent feedings, small stomach size, and predominance of the recumbent position allow reflux to occur during transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter.6-9

Healthy infants and children may have asymptomatic episodes of GER; or episodes may be short, lasting less than three minutes, and occurring postprandially.6 Only when GER involves blood loss, esophagitis, strictures, nutritional deficits, and/or apnea should GERD be considered.9

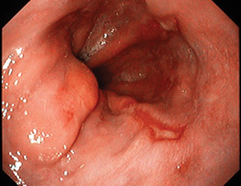

The pathologic process known as GERD involves persistent, troublesome symptoms resulting from continued mucosal exposure to stomach acid, damaging the lining of the esophagus and possibly leading to erosive esophagitis.6,10,11 Endoscopic findings indicating GERD-associated esophageal damage include visible tears in the esophageal mucosa near the gastroesophageal junction6 (see Figure 1). In one single-center US study, almost 30% of patients with pediatric GERD who underwent endoscopy had erosive esophagitis.4

Continued on next page >>

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

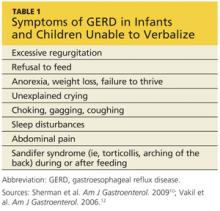

Symptoms of GERD vary among adults and children in different age-groups. According to the Montreal definition, which was developed and modified by an international panel of pediatric gastroenterologists,10,12 GERD should be suspected in infants and toddlers who fail to thrive and exhibit the symptoms listed in Table 1.10,12 Clinicians should also consider GERD in older children and adolescents who present with heartburn, since it is the most common initial presenting symptom.10,13 Of note, a 2010 database study of UK children with GERD revealed a high incidence before age 1 year and the greatest incidence among 16- to 17-year-olds.5

GERD should also be considered in pediatric patients who complain of vague symptoms of “stomachache” or nausea, abdominal pain or chest pain, since children may have trouble describing the sensation of heartburn.6,10 Children may also present with extra-esophageal complaints, such as dry cough, asthma-like symptoms, sore throat, hoarseness, sleep apnea, or dysphagia, all of which can be complications of GERD.10,11 Researchers have suggested that GERD contributes to and/or exacerbates pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, and chronic cough.6,10 Therefore, clinicians should consider GERD in children with these seemingly unrelated illnesses.

Continued on next page >>

RISK FACTORS

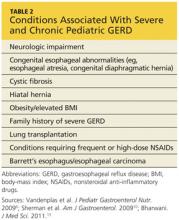

Certain pediatric groups are at increased risk for severe GERD, with or without complications. Neurologic impairment can cause dysphagia, and anatomic abnormalities such as hiatal hernia can impair lower esophageal sphincter function, allowing acid to rise into the esophagus.6,11 Table 26,10,13 lists illnesses and congenital conditions that are considered predisposing factors for severe, chronic GERD.

When seeing patients in these populations, clinicians should specifically focus on relevant GI symptoms during the history and physical exam. Clinicians should also consider long-term monitoring for complications or changes that might indicate new-onset GERD.

Overweight and Obesity

Although data are limited on the relationship between pediatric GERD and obesity,14 associated research findings seem to conflict with the established relationship in adult patients. While certain study groups found an association between obesity, elevated BMI, and increased waist circumference with an increase in symptoms of GERD (eg, regurgitation, heartburn),15,16 others found no significant correlation between overweight and reflux esophagitis.14,17 Notably, one analysis found a significant correlation between male gender and incidence of GERD.17

Although the evidence is not conclusive, clinicians are encouraged to counsel the older children among their patients on the benefits of weight and BMI reduction—encouraging them to achieve an overall healthier lifestyle and avoid diseases associated with excess weight.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In infants with unusual symptoms, certain GI conditions such as obstructive disorders (eg, pyloric stenosis), motility disorders, and peptic ulcer disease must be ruled out with further diagnostic testing.6,7 Red-flag symptoms that warrant further investigation include hematemesis, hematochezia, diarrhea, abdominal tenderness or distention, constipation, bilious vomiting, onset of vomiting after age 6 months, failure to thrive, macrocephaly or microcephaly, fever, lethargy, and hepatosplenomegaly.6,7 More common differentials are described below.

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Eosinophilic esophagitis is an inflammatory condition of the esophagus, an apparent manifestation of food allergy (eg, milk protein), characterized by infiltrating mucosal eosinophils.6,18 First identified in children (though also occurring in adults), eosinophilic esophagitis is recognized as a more common cause of dysphagia than GERD.6

This recently discovered disease is often mistaken for GERD. While symptoms including heartburn and dysphagia occur in both conditions, eosinophilic esophagitis can only be diagnosed via multiple endoscopic mucosal biopsies. Corticosteroid therapy has been found to be a more effective treatment for this condition than acid suppression therapy.19

Current research is focused on a possible link between eosinophilic esophagitis and autoimmune disease, as many affected patients also have asthma, allergic rhinitis, and/or eczema.19 The increasing prevalence of childhood allergies should prompt clinicians to place eosinophilic esophagitis on the short list of differentials when evaluating a child for GERD-type symptoms. Referral for evaluation by an allergist may also be beneficial.

Asthma

GER may actually trigger asthma in some patients, even without symptoms of GERD.6 While there is support for a possible link between GERD and asthma in infants and children, a definitive relationship cannot be confirmed without more reliable studies.20 However, clinicians must not overlook the possibility of GERD in a child who presents with symptoms indicative of asthma, such as wheezing, shortness of breath, coughing, and chest tightness.

Other Extra-Esophageal Diseases

Concern exists over apparent associations between GERD and other extra-esophageal illnesses. In addition to asthma, the Montreal consensus group10,12 found a connection between GERD and other respiratory conditions, including chronic cough and chronic laryngitis. These conditions usually represent multifactorial disease processes, researchers state, and GER can be an exacerbating factor rather than an actual cause of these conditions.5,10

Further manifestations of extra-esophageal GERD include pneumonia, bronchiectasis, any apparent life-threatening event, laryngotracheitis, sinusitis, and dental erosion. Again, causality has not been clearly established, and the shortage of high-quality studies with adequate sample sizes makes it impossible to confirm clear relationships.21 It is therefore prudent for clinicians to evaluate any child with these non-GI conditions for reflux disease.

Continued on next page >>

EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

In 2009, the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN)6 released international guidelines for the management of pediatric GERD, including evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Making a diagnosis of GERD in an infant or a toddler can be challenging, since no reliable pathognomonic symptoms are known. Older children and adolescents are better able to articulate their presenting symptoms (which resemble those of adults); thus, a detailed history and physical exam are ordinarily adequate to diagnose GERD and introduce treatment in these patients.6

The diagnostic tool that is considered the gold standard for pediatric patients, including infants, is 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring. This test directly measures the quantity of acid present in the esophagus by way of an internal probe that is passed through the mouth or nose and worn for 24 hours. Esophageal pH monitoring quantifies the amount of acid to which the esophagus is exposed over this time period, compared with standard pediatric values.6,13

However, a newer combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring (MII/pH) tool offers advantages over esophageal pH monitoring, as it detects nonacidic or weakly acidic reflux events, in addition to more obvious episodes of acidic reflux.6,13,22

Clinical benefits of the MII/pH are:

• Better efficiency than pH monitoring alone in the evaluation of respiratory symptoms and GERD

• Ability to correlate timing of reflux episodes with symptoms, including chronic cough, apnea, and other respiratory symptoms

• Improved accuracy in monitoring postprandial reflux episodes, which are typically less acidic.13,23

Additionally, MII/pH provides a graphic readout from which the duration, height, and frequency of the reflux episodes can be analyzed. Currently, the chief disadvantage to its use is the absence of standardized pediatric values.13

Endoscopic biopsy should not be used to establish whether esophagitis is due to reflux. Endoscopically visible breaks in the distal esophageal mucosa are the most reliable indicators of reflux esophagitis. However, because other signs, such as mucosal erythema, pallor, and vascular patterns have normal variations, they cannot be considered evidence of reflux esophagitis.6 Endoscopic biopsy is mainly recommended for confirmation of suspected Barrett’s esophagus (which is rare in children) or for eosinophilic esophagitis, as it can confirm infiltrating mucosal eosinophils.6,19

Nuclear scintigraphy uses imaging to time the passage of a radioisotope-labeled meal through the upper GI tract. It can provide information about gastric emptying, which may be delayed in children with GERD. It may also be useful in diagnosing aspiration in patients with chronic intractable respiratory symptoms.6 Because standardized techniques and age-specific norms are lacking, however, nuclear scintigraphy is not recommended for patients with other potentially reflux-related symptoms. The sensitivity of this test is low, and negative results may not exclude the possibility of reflux and aspiration.6

Barium contrast radiography (upper GI series) is not recommended due to its poor sensitivity and specificity. This test is useful for confirming anatomic anomalies, however.6

For infants and toddlers with symptoms suggestive of GERD, the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN authors6 find no evidence to support an empiric trial of pharmacologic treatment to confirm the diagnosis. For older, verbal children and adolescents who present with heartburn and/or chest pain, a short-term trial (as long as 4 weeks) of acid suppressants may be used to identify acid reflux as the cause of these symptoms.

Based on the guidelines by Vandenplas et al,6 a clinician’s initial approach to evaluation for GERD and its diagnosis should begin with a thorough history and physical exam and the least invasive diagnostic process possible. The child’s specific symptoms and suspected involvement of other organ systems will dictate the use of progressively invasive diagnostic strategies.

MANAGEMENT OF GERD

Conservative Treatment

Nonpharmacologic, age-appropriate approaches focus on diet and lifestyle changes. An effective treatment option for infants uses dry rice cereal to thicken the formula, resulting in decreased visible reflux and regurgitation.6,8 Recommended amounts of thickened formula are 4 oz/kg/d, divided into four to eight daily feedings, depending on the age of the patient; infants close to 1 year require only four feedings.8 For breastfed infants, expressed breast milk can be thickened with rice cereal and given at comparable volumes.8

Recommendations from the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN clinical practice guidelines6 include a two- to four-week trial of an extensively hydrolyzed protein formula for formula-fed infants who vomit frequently. These formulas are considered hypoallergenic and contain shorter protein particles, allowing for easier digestion.8

Lifestyle changes recommended for adults with GERD can also be tailored for use in pediatric patients (see Table 38,11). They include avoidance of overfeeding by giving smaller portions at greater frequency (as described above), avoidance of foods known to cause GERD symptoms, avoidance of cigarette smoke, restriction of eating and drinking close to bedtime, elevation of the head of the bed or crib (use of a pillow is not recommended in children younger than 1 year), and a left-sided sleeping position for adolescents.6,11

Holding infants upright for 30 minutes after feeding with ample burping may reduce reflux.11 In infants, the prone position provides the greatest benefit for reducing acid reflux, according to findings from one study based on pH monitoring.13 Nonetheless, the association between prone positioning and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) has led to recommendations of supine position when infants sleep unobserved.6 Perhaps supervised “tummy time” several times per day (eg, after feeding) can help reduce GERD symptoms in infants.

Finally, breastfeeding mothers are advised to avoid consuming cow’s milk, eggs, and soy products, as their presence in breast milk may promote reflux in an infant with unrecognized food allergy.6,8

Pharmacologic Treatment

Since esophagitis develops as a result of continuous acid exposure from the refluxate, the primary pharmacologic therapy for the treatment of GERD is aimed at acid reduction in the upper GI tract. Current pharmacologic options include histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).6 H2RAs have been shown to alleviate symptoms and promote mucosal healing. To their disadvantage, long-term use of H2RAs may lead to drug tolerance.

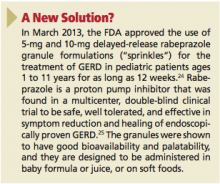

PPIs are superior to H2RAs in symptom relief and esophageal healing without causing tolerance; however, although certain agents are FDA approved for treatment of children age 1 year or older with GERD (including esomeprazole, lansoprazole, and omeprazole), use of PPIs in infants younger than 1 year is controversial.6,13 (See “New Solution for Pediatric GERD?”24,25)

According to results from existing studies of PPI use in infants with GERD ages 34 weeks to 1 year, PPIs are no more effective at symptom reduction than placebo.2,26 Further, data to demonstrate efficacy of long-term PPI use in infants and toddlers are scant.6,27 Safety results from various trials are inconsistent, ranging from no reported adverse effects to rare but severe adverse events, including necrotizing enterocolitis in infants, and lower respiratory tract infections, community-acquired pneumonia, gastric polyps, and acute gastroenteritis in children.2,26

The most common adverse effects of esomeprazole use in infants and children are nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, pyrexia, and headache.4,6 Because of these potential risks, none of the PPIs is approved for use in infants younger than 1 year. However, a short-term PPI trial for as long as 4 weeks (along with lifestyle changes) for symptom reduction in older children is recommended by the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN clinical practice guidelines.2,6,13

Also based on the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN guidelines,6 empiric PPI therapy is not recommended in pediatric patients presenting with wheezing or asthma. One research team has reported that asthma symptoms may be validly treated with a PPI in patients who do not respond to standard asthma treatment and who have a high reflux index.28 However, an absence of studies to support this finding makes a firm recommendation impossible.

According to the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN guidelines,6 there is insufficient evidence to justify the use of prokinetic agents (eg, metoclopramide, erythromycin, bethanechol, domperidone) for pediatric GERD, as their potential risks outweigh their potential benefits. Neither are alginates nor sucralfate recommended for long-term therapy, because PPIs and H2RAs are considered more effective.6

Surgical Treatment

As with adults, surgery should be a last resort for treatment. Antireflux surgery is deemed appropriate only in children who cannot tolerate long-term medical therapy due to life-threatening complications, who cannot comply with the treatment schedule, or in whom medications have been found ineffective.6

The gold standard for the surgical treatment of GERD is laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, a procedure in which the shape of the stomach fundus is modified to provide strength and functional support to the lower esophageal sphincter.29 Although children with heartburn, asthma, nocturnal asthma symptoms, or steroid-dependent asthma have been found to benefit clinically from long-term medical therapy or antireflux surgery, the comparable benefits of surgical versus medical treatment in these children is unknown.6

Continued on next page >>

PROGNOSIS AND FOLLOW-UP

The large majority of infants respond well to conservative nonpharmacologic treatment and outgrow their reflux symptoms by age 1 year, with maturation of muscle control and lower esophageal sphincter function.7 Further testing and intervention is generally not required in healthy infants, and parents should be reassured by this information.6,7 If regurgitation does not resolve by age 12 to 18 months, or if red-flag symptoms develop, referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist is recommended.6

For older children and adolescents with GERD, lifestyle changes should be implemented first, followed by short-term pharmacologic intervention, as recommended by appropriate guidelines.

Children with other illnesses or complications, such as neurologic impairment, premature birth, or a strong family history of severe GERD, have a poorer prognosis and may require more aggressive diagnostic evaluation and management.7 Complications such as esophageal stricture and Barrett’s esophagus, which poses an increased risk for adenocarcinoma, require referral to a specialist for further evaluation.10

CONCLUSION

GERD is no longer a condition found only in adults. Since primary care practitioners are increasingly likely to see GERD in their pediatric patients, it is important for these clinicians to become familiar with the contributing factors, definitive signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of GERD. Children at high risk for GERD should be followed closely and introduced to appropriate lifestyle modifications to avoid the troublesome symptoms of GERD and its complications, whenever possible. In the differential diagnosis, respiratory illnesses and other extra-esophageal diseases, as well as eosinophilic esophagitis in allergic patients, should be considered.

Practitioners should consult the 2009 NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN clinical practice guidelines for further details regarding the evaluation, diagnosis, preferred treatment, management of pediatric GERD, and indications for specialist referral. Research is ongoing in many areas, including the suitability of PPI use in pediatrics. More research is needed to clarify the theorized link between GERD and asthma.

1. Diaz DM, Winter HS, Colletti RB, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practice styles of North American pediatricians regarding gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:56-64.

2. van der Pol RJ, Smits MJ, van Wijk MP, et al. Efficacy of proton-pump inhibitors in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:925-935.

3. Nelson SP, Kothari S, Wu EQ, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux disease and acid-related conditions: trends in incidence of diagnosis and acid suppression therapy. J Med Econ. 2009;12:348-355.

4. Tolia V, Gilger MA, Barker PN, Illueca M. Healing of erosive esophagitis and improvement of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease after esomeprazole treatment in children 12 to 36 months old. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:593-598.

5. Vakil N. Disease definition, clinical manifestations, epidemiology and natural history of GERD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:759-764.

6. Vandenplas Y, Rudolph CD, Di Lorenzo C, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:498-547.

7. Michail S. Gastroesophageal reflux. Pediatr Rev. 2007;28:101-111.

8. Orenstein SR, McGowan JD. Efficacy of conservative therapy as taught in the primary care setting for symptoms suggesting infant gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. 2008;152:310-314.

9. Vandenplas Y, Lifshitz JZ, Orenstein S, et al. Nutritional management of regurgitation in infants. J Am Coll Nutr. 1998;17:308-316.

10. Sherman PM, Hassall E, Fagundes-Neto U, et al. A global, evidence-based consensus on the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the pediatric population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1278-1295.

11. Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. Heartburn, gastroesophageal reflux (GER), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)(2007). http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/gerd. Accessed April 4, 2013.

12. Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et al; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920.

13. Bharwani S. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in children: from infancy to adolescence. J Med Sci. 2011;4:25-39.

14. Patel NR, Ward MJ, Beneck D, et al. The association between childhood overweight and reflux esophagitis. J Obes. 2010;2010.

15. Quitadamo P, Buonavolontà R, Miele E, et al. Total and abdominal obesity are risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:72-75.

16. Pashankar DS, Corbin Z, Shah SK, Caprio S. Increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in obese children evaluated in an academic medical center. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:410-413.

17. Elitsur Y, Dementieva Y, Elitsur R, Rewalt M. Obesity is not a risk factor in children with reflux esophagitis: a retrospective analysis of 738 children. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009;7:211-214.

18. Hill DJ, Heine RG, Cameron DJ, et al. Role of food protein intolerance in infants with persistent distress attributed to reflux esophagitis. J Pediatr. 2000;136:641-647.

19. Franciosi JP, Liacouras CA. Eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin N America. 2009;29:19-27.

20. Thakkar K, Boatright RO, Gilger MA, El-Serag HB. Gastroesophageal reflux and asthma in children: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010; 125:e925-e930.

21. Tolia V, Vandenplas Y. Systematic review: the extra-oesophageal symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:258-272.

22. Cresi F, Locatelli E, Marinaccio C, et al. Prognostic values of multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring in newborns with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr. 2012 Nov 10. [Epub ahead of print]

23. Dalby K, Nielsen RG, Markoew S, et al. Reproducibility of 24-hour combined multiple intraluminal impedance (MII) and pH measurements in infants and children: evaluation of a diagnostic procedure for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2159-2165.

24. Tucker ME. FDA approves pediatric formulation of proton-pump inhibitor. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/781615. Accessed April 4, 2013.

25. Zannikos PN, Doose DR, Leitz GJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of rabeprazole in children 1 to 11 years old with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:691-701.

26. Orenstein SR, Hassall E. Infants and proton pump inhibitors: tribulations, no trials. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:395-398.

27. Barron JJ, Tan H, Spalding J, et al. Proton pump inhibitor utilization patterns in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:421-427.

28. Sopo SM, Radzik D, Calvani M. Does treatment with proton pump inhibitors for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) improve asthma symptoms in children with asthma and GERD? A systematic review. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2009;19:1-5.

29. Anvari M, Allen C, Marshall J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for the treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): 3-year outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2547-2554

CE/CME No: CR-1305

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Differentiate between gastroesophageal reflux and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GER and GERD, respectively) in the pediatric patient, including symptomatology and risk factors.

• Explain typical and atypical presentations of GERD as factors in the differential diagnosis.

• Describe diagnostic testing options for GERD and their appropriate use in infants and children with suspected GERD.

• Discuss age-appropriate strategies to reduce the symptoms of GERD in children, including lifestyle changes and pharmacologic and surgical options.

FACULTY

Ellen D. Mandel is Clinical Associate Professor in the Pace University Physician Assistant Program in New York City, and Associate Professor in the Physician Assistant Program at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey. Claudia Ashforth and Kristine Daugherty are students in the Pace University Lenox Hill Hospital Physician Assistant Program.

The authors have no significant financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

As with US adults, infants and children appear to be at increased risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Lacking a cardinal symptom in children and often linked with confounding extra-esophageal symptoms, pediatric GERD challenges the primary care clinician to make an early diagnosis, preventing progressive damage and possible complications. Management begins with conservative lifestyle changes; pharmacologic and surgical options are reserved for specific pediatric patients.

Traditionally, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been viewed as an adult disease, but it is now recognized as a disorder that also occurs in children. A teenager with heartburn, a child with complaints of chest pain, and a coughing infant refusing to feed may all be experiencing it. Review of the literature reveals an increased incidence of GERD in both adults and children, making it one of the five most common gastrointestinal (GI) conditions in the United States.1

US pediatric hospitalization rates associated with GERD significantly increased from 1995 to 2000, accounting for 4% of these admissions.1 In a 2009 review of ICD-9 codes in a large claims database, GERD was diagnosed in 12.3% of North American infants and in 1% of other pediatric age-groups.2,3 In another recent study in which pediatric endoscopy data from 1999 to 2002 were analyzed, 9.5% of children age 1 year and 7.6% of children age 2 had erosive esophagitis.4

It is unclear whether the increased frequency in diagnosis of GERD should be attributed to improved diagnostic strategies or to an actual increase in disease prevalence.1 In any event, a timely diagnosis of GERD is essential to allow for appropriate intervention and early symptom management to reduce the risk for complications.

Overall, GERD is primarily a Western disease, affecting an estimated 10% to 15% of this geographic population. It is associated with obesity, recent dietary trends, and other causes.5 Prevalence of GERD in the general population has been shown to vary across ethnic groups. In the US, persons of Hispanic descent are more likely to be affected than whites, with symptoms of GERD least common among Asian-Americans.5

Since pediatric GERD is seen in primary care settings in the same rising numbers as associated hospital admissions, clinicians who provide primary care must be aware of its contributing factors, treatment modalities that are most effective in reducing symptoms, and strategies to prevent this disease. Treatment choices vary according to patient age-groups: infants (younger than 1 year), children ages 1 to 11 years, and adolescents, 12 to 18.

DISTINGUISHING GERD FROM GER

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the term used to describe the passage of gastric contents, including stomach acid, fluids, and food, into the esophagus, with or without regurgitation or vomiting.6 GER is a normal, common physiologic process among infants, in whom frequent feedings, small stomach size, and predominance of the recumbent position allow reflux to occur during transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter.6-9

Healthy infants and children may have asymptomatic episodes of GER; or episodes may be short, lasting less than three minutes, and occurring postprandially.6 Only when GER involves blood loss, esophagitis, strictures, nutritional deficits, and/or apnea should GERD be considered.9

The pathologic process known as GERD involves persistent, troublesome symptoms resulting from continued mucosal exposure to stomach acid, damaging the lining of the esophagus and possibly leading to erosive esophagitis.6,10,11 Endoscopic findings indicating GERD-associated esophageal damage include visible tears in the esophageal mucosa near the gastroesophageal junction6 (see Figure 1). In one single-center US study, almost 30% of patients with pediatric GERD who underwent endoscopy had erosive esophagitis.4

Continued on next page >>

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of GERD vary among adults and children in different age-groups. According to the Montreal definition, which was developed and modified by an international panel of pediatric gastroenterologists,10,12 GERD should be suspected in infants and toddlers who fail to thrive and exhibit the symptoms listed in Table 1.10,12 Clinicians should also consider GERD in older children and adolescents who present with heartburn, since it is the most common initial presenting symptom.10,13 Of note, a 2010 database study of UK children with GERD revealed a high incidence before age 1 year and the greatest incidence among 16- to 17-year-olds.5

GERD should also be considered in pediatric patients who complain of vague symptoms of “stomachache” or nausea, abdominal pain or chest pain, since children may have trouble describing the sensation of heartburn.6,10 Children may also present with extra-esophageal complaints, such as dry cough, asthma-like symptoms, sore throat, hoarseness, sleep apnea, or dysphagia, all of which can be complications of GERD.10,11 Researchers have suggested that GERD contributes to and/or exacerbates pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, and chronic cough.6,10 Therefore, clinicians should consider GERD in children with these seemingly unrelated illnesses.

Continued on next page >>

RISK FACTORS

Certain pediatric groups are at increased risk for severe GERD, with or without complications. Neurologic impairment can cause dysphagia, and anatomic abnormalities such as hiatal hernia can impair lower esophageal sphincter function, allowing acid to rise into the esophagus.6,11 Table 26,10,13 lists illnesses and congenital conditions that are considered predisposing factors for severe, chronic GERD.

When seeing patients in these populations, clinicians should specifically focus on relevant GI symptoms during the history and physical exam. Clinicians should also consider long-term monitoring for complications or changes that might indicate new-onset GERD.

Overweight and Obesity

Although data are limited on the relationship between pediatric GERD and obesity,14 associated research findings seem to conflict with the established relationship in adult patients. While certain study groups found an association between obesity, elevated BMI, and increased waist circumference with an increase in symptoms of GERD (eg, regurgitation, heartburn),15,16 others found no significant correlation between overweight and reflux esophagitis.14,17 Notably, one analysis found a significant correlation between male gender and incidence of GERD.17

Although the evidence is not conclusive, clinicians are encouraged to counsel the older children among their patients on the benefits of weight and BMI reduction—encouraging them to achieve an overall healthier lifestyle and avoid diseases associated with excess weight.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In infants with unusual symptoms, certain GI conditions such as obstructive disorders (eg, pyloric stenosis), motility disorders, and peptic ulcer disease must be ruled out with further diagnostic testing.6,7 Red-flag symptoms that warrant further investigation include hematemesis, hematochezia, diarrhea, abdominal tenderness or distention, constipation, bilious vomiting, onset of vomiting after age 6 months, failure to thrive, macrocephaly or microcephaly, fever, lethargy, and hepatosplenomegaly.6,7 More common differentials are described below.

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Eosinophilic esophagitis is an inflammatory condition of the esophagus, an apparent manifestation of food allergy (eg, milk protein), characterized by infiltrating mucosal eosinophils.6,18 First identified in children (though also occurring in adults), eosinophilic esophagitis is recognized as a more common cause of dysphagia than GERD.6

This recently discovered disease is often mistaken for GERD. While symptoms including heartburn and dysphagia occur in both conditions, eosinophilic esophagitis can only be diagnosed via multiple endoscopic mucosal biopsies. Corticosteroid therapy has been found to be a more effective treatment for this condition than acid suppression therapy.19

Current research is focused on a possible link between eosinophilic esophagitis and autoimmune disease, as many affected patients also have asthma, allergic rhinitis, and/or eczema.19 The increasing prevalence of childhood allergies should prompt clinicians to place eosinophilic esophagitis on the short list of differentials when evaluating a child for GERD-type symptoms. Referral for evaluation by an allergist may also be beneficial.

Asthma

GER may actually trigger asthma in some patients, even without symptoms of GERD.6 While there is support for a possible link between GERD and asthma in infants and children, a definitive relationship cannot be confirmed without more reliable studies.20 However, clinicians must not overlook the possibility of GERD in a child who presents with symptoms indicative of asthma, such as wheezing, shortness of breath, coughing, and chest tightness.

Other Extra-Esophageal Diseases

Concern exists over apparent associations between GERD and other extra-esophageal illnesses. In addition to asthma, the Montreal consensus group10,12 found a connection between GERD and other respiratory conditions, including chronic cough and chronic laryngitis. These conditions usually represent multifactorial disease processes, researchers state, and GER can be an exacerbating factor rather than an actual cause of these conditions.5,10

Further manifestations of extra-esophageal GERD include pneumonia, bronchiectasis, any apparent life-threatening event, laryngotracheitis, sinusitis, and dental erosion. Again, causality has not been clearly established, and the shortage of high-quality studies with adequate sample sizes makes it impossible to confirm clear relationships.21 It is therefore prudent for clinicians to evaluate any child with these non-GI conditions for reflux disease.

Continued on next page >>

EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

In 2009, the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN)6 released international guidelines for the management of pediatric GERD, including evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Making a diagnosis of GERD in an infant or a toddler can be challenging, since no reliable pathognomonic symptoms are known. Older children and adolescents are better able to articulate their presenting symptoms (which resemble those of adults); thus, a detailed history and physical exam are ordinarily adequate to diagnose GERD and introduce treatment in these patients.6

The diagnostic tool that is considered the gold standard for pediatric patients, including infants, is 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring. This test directly measures the quantity of acid present in the esophagus by way of an internal probe that is passed through the mouth or nose and worn for 24 hours. Esophageal pH monitoring quantifies the amount of acid to which the esophagus is exposed over this time period, compared with standard pediatric values.6,13

However, a newer combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring (MII/pH) tool offers advantages over esophageal pH monitoring, as it detects nonacidic or weakly acidic reflux events, in addition to more obvious episodes of acidic reflux.6,13,22

Clinical benefits of the MII/pH are:

• Better efficiency than pH monitoring alone in the evaluation of respiratory symptoms and GERD

• Ability to correlate timing of reflux episodes with symptoms, including chronic cough, apnea, and other respiratory symptoms

• Improved accuracy in monitoring postprandial reflux episodes, which are typically less acidic.13,23

Additionally, MII/pH provides a graphic readout from which the duration, height, and frequency of the reflux episodes can be analyzed. Currently, the chief disadvantage to its use is the absence of standardized pediatric values.13

Endoscopic biopsy should not be used to establish whether esophagitis is due to reflux. Endoscopically visible breaks in the distal esophageal mucosa are the most reliable indicators of reflux esophagitis. However, because other signs, such as mucosal erythema, pallor, and vascular patterns have normal variations, they cannot be considered evidence of reflux esophagitis.6 Endoscopic biopsy is mainly recommended for confirmation of suspected Barrett’s esophagus (which is rare in children) or for eosinophilic esophagitis, as it can confirm infiltrating mucosal eosinophils.6,19

Nuclear scintigraphy uses imaging to time the passage of a radioisotope-labeled meal through the upper GI tract. It can provide information about gastric emptying, which may be delayed in children with GERD. It may also be useful in diagnosing aspiration in patients with chronic intractable respiratory symptoms.6 Because standardized techniques and age-specific norms are lacking, however, nuclear scintigraphy is not recommended for patients with other potentially reflux-related symptoms. The sensitivity of this test is low, and negative results may not exclude the possibility of reflux and aspiration.6

Barium contrast radiography (upper GI series) is not recommended due to its poor sensitivity and specificity. This test is useful for confirming anatomic anomalies, however.6

For infants and toddlers with symptoms suggestive of GERD, the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN authors6 find no evidence to support an empiric trial of pharmacologic treatment to confirm the diagnosis. For older, verbal children and adolescents who present with heartburn and/or chest pain, a short-term trial (as long as 4 weeks) of acid suppressants may be used to identify acid reflux as the cause of these symptoms.

Based on the guidelines by Vandenplas et al,6 a clinician’s initial approach to evaluation for GERD and its diagnosis should begin with a thorough history and physical exam and the least invasive diagnostic process possible. The child’s specific symptoms and suspected involvement of other organ systems will dictate the use of progressively invasive diagnostic strategies.

MANAGEMENT OF GERD

Conservative Treatment

Nonpharmacologic, age-appropriate approaches focus on diet and lifestyle changes. An effective treatment option for infants uses dry rice cereal to thicken the formula, resulting in decreased visible reflux and regurgitation.6,8 Recommended amounts of thickened formula are 4 oz/kg/d, divided into four to eight daily feedings, depending on the age of the patient; infants close to 1 year require only four feedings.8 For breastfed infants, expressed breast milk can be thickened with rice cereal and given at comparable volumes.8

Recommendations from the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN clinical practice guidelines6 include a two- to four-week trial of an extensively hydrolyzed protein formula for formula-fed infants who vomit frequently. These formulas are considered hypoallergenic and contain shorter protein particles, allowing for easier digestion.8

Lifestyle changes recommended for adults with GERD can also be tailored for use in pediatric patients (see Table 38,11). They include avoidance of overfeeding by giving smaller portions at greater frequency (as described above), avoidance of foods known to cause GERD symptoms, avoidance of cigarette smoke, restriction of eating and drinking close to bedtime, elevation of the head of the bed or crib (use of a pillow is not recommended in children younger than 1 year), and a left-sided sleeping position for adolescents.6,11

Holding infants upright for 30 minutes after feeding with ample burping may reduce reflux.11 In infants, the prone position provides the greatest benefit for reducing acid reflux, according to findings from one study based on pH monitoring.13 Nonetheless, the association between prone positioning and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) has led to recommendations of supine position when infants sleep unobserved.6 Perhaps supervised “tummy time” several times per day (eg, after feeding) can help reduce GERD symptoms in infants.

Finally, breastfeeding mothers are advised to avoid consuming cow’s milk, eggs, and soy products, as their presence in breast milk may promote reflux in an infant with unrecognized food allergy.6,8

Pharmacologic Treatment

Since esophagitis develops as a result of continuous acid exposure from the refluxate, the primary pharmacologic therapy for the treatment of GERD is aimed at acid reduction in the upper GI tract. Current pharmacologic options include histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).6 H2RAs have been shown to alleviate symptoms and promote mucosal healing. To their disadvantage, long-term use of H2RAs may lead to drug tolerance.

PPIs are superior to H2RAs in symptom relief and esophageal healing without causing tolerance; however, although certain agents are FDA approved for treatment of children age 1 year or older with GERD (including esomeprazole, lansoprazole, and omeprazole), use of PPIs in infants younger than 1 year is controversial.6,13 (See “New Solution for Pediatric GERD?”24,25)

According to results from existing studies of PPI use in infants with GERD ages 34 weeks to 1 year, PPIs are no more effective at symptom reduction than placebo.2,26 Further, data to demonstrate efficacy of long-term PPI use in infants and toddlers are scant.6,27 Safety results from various trials are inconsistent, ranging from no reported adverse effects to rare but severe adverse events, including necrotizing enterocolitis in infants, and lower respiratory tract infections, community-acquired pneumonia, gastric polyps, and acute gastroenteritis in children.2,26

The most common adverse effects of esomeprazole use in infants and children are nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, pyrexia, and headache.4,6 Because of these potential risks, none of the PPIs is approved for use in infants younger than 1 year. However, a short-term PPI trial for as long as 4 weeks (along with lifestyle changes) for symptom reduction in older children is recommended by the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN clinical practice guidelines.2,6,13

Also based on the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN guidelines,6 empiric PPI therapy is not recommended in pediatric patients presenting with wheezing or asthma. One research team has reported that asthma symptoms may be validly treated with a PPI in patients who do not respond to standard asthma treatment and who have a high reflux index.28 However, an absence of studies to support this finding makes a firm recommendation impossible.

According to the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN guidelines,6 there is insufficient evidence to justify the use of prokinetic agents (eg, metoclopramide, erythromycin, bethanechol, domperidone) for pediatric GERD, as their potential risks outweigh their potential benefits. Neither are alginates nor sucralfate recommended for long-term therapy, because PPIs and H2RAs are considered more effective.6

Surgical Treatment

As with adults, surgery should be a last resort for treatment. Antireflux surgery is deemed appropriate only in children who cannot tolerate long-term medical therapy due to life-threatening complications, who cannot comply with the treatment schedule, or in whom medications have been found ineffective.6

The gold standard for the surgical treatment of GERD is laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, a procedure in which the shape of the stomach fundus is modified to provide strength and functional support to the lower esophageal sphincter.29 Although children with heartburn, asthma, nocturnal asthma symptoms, or steroid-dependent asthma have been found to benefit clinically from long-term medical therapy or antireflux surgery, the comparable benefits of surgical versus medical treatment in these children is unknown.6

Continued on next page >>

PROGNOSIS AND FOLLOW-UP

The large majority of infants respond well to conservative nonpharmacologic treatment and outgrow their reflux symptoms by age 1 year, with maturation of muscle control and lower esophageal sphincter function.7 Further testing and intervention is generally not required in healthy infants, and parents should be reassured by this information.6,7 If regurgitation does not resolve by age 12 to 18 months, or if red-flag symptoms develop, referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist is recommended.6

For older children and adolescents with GERD, lifestyle changes should be implemented first, followed by short-term pharmacologic intervention, as recommended by appropriate guidelines.

Children with other illnesses or complications, such as neurologic impairment, premature birth, or a strong family history of severe GERD, have a poorer prognosis and may require more aggressive diagnostic evaluation and management.7 Complications such as esophageal stricture and Barrett’s esophagus, which poses an increased risk for adenocarcinoma, require referral to a specialist for further evaluation.10

CONCLUSION

GERD is no longer a condition found only in adults. Since primary care practitioners are increasingly likely to see GERD in their pediatric patients, it is important for these clinicians to become familiar with the contributing factors, definitive signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of GERD. Children at high risk for GERD should be followed closely and introduced to appropriate lifestyle modifications to avoid the troublesome symptoms of GERD and its complications, whenever possible. In the differential diagnosis, respiratory illnesses and other extra-esophageal diseases, as well as eosinophilic esophagitis in allergic patients, should be considered.

Practitioners should consult the 2009 NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN clinical practice guidelines for further details regarding the evaluation, diagnosis, preferred treatment, management of pediatric GERD, and indications for specialist referral. Research is ongoing in many areas, including the suitability of PPI use in pediatrics. More research is needed to clarify the theorized link between GERD and asthma.

CE/CME No: CR-1305

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Differentiate between gastroesophageal reflux and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GER and GERD, respectively) in the pediatric patient, including symptomatology and risk factors.

• Explain typical and atypical presentations of GERD as factors in the differential diagnosis.

• Describe diagnostic testing options for GERD and their appropriate use in infants and children with suspected GERD.

• Discuss age-appropriate strategies to reduce the symptoms of GERD in children, including lifestyle changes and pharmacologic and surgical options.

FACULTY

Ellen D. Mandel is Clinical Associate Professor in the Pace University Physician Assistant Program in New York City, and Associate Professor in the Physician Assistant Program at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey. Claudia Ashforth and Kristine Daugherty are students in the Pace University Lenox Hill Hospital Physician Assistant Program.

The authors have no significant financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

As with US adults, infants and children appear to be at increased risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Lacking a cardinal symptom in children and often linked with confounding extra-esophageal symptoms, pediatric GERD challenges the primary care clinician to make an early diagnosis, preventing progressive damage and possible complications. Management begins with conservative lifestyle changes; pharmacologic and surgical options are reserved for specific pediatric patients.

Traditionally, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been viewed as an adult disease, but it is now recognized as a disorder that also occurs in children. A teenager with heartburn, a child with complaints of chest pain, and a coughing infant refusing to feed may all be experiencing it. Review of the literature reveals an increased incidence of GERD in both adults and children, making it one of the five most common gastrointestinal (GI) conditions in the United States.1

US pediatric hospitalization rates associated with GERD significantly increased from 1995 to 2000, accounting for 4% of these admissions.1 In a 2009 review of ICD-9 codes in a large claims database, GERD was diagnosed in 12.3% of North American infants and in 1% of other pediatric age-groups.2,3 In another recent study in which pediatric endoscopy data from 1999 to 2002 were analyzed, 9.5% of children age 1 year and 7.6% of children age 2 had erosive esophagitis.4

It is unclear whether the increased frequency in diagnosis of GERD should be attributed to improved diagnostic strategies or to an actual increase in disease prevalence.1 In any event, a timely diagnosis of GERD is essential to allow for appropriate intervention and early symptom management to reduce the risk for complications.

Overall, GERD is primarily a Western disease, affecting an estimated 10% to 15% of this geographic population. It is associated with obesity, recent dietary trends, and other causes.5 Prevalence of GERD in the general population has been shown to vary across ethnic groups. In the US, persons of Hispanic descent are more likely to be affected than whites, with symptoms of GERD least common among Asian-Americans.5

Since pediatric GERD is seen in primary care settings in the same rising numbers as associated hospital admissions, clinicians who provide primary care must be aware of its contributing factors, treatment modalities that are most effective in reducing symptoms, and strategies to prevent this disease. Treatment choices vary according to patient age-groups: infants (younger than 1 year), children ages 1 to 11 years, and adolescents, 12 to 18.

DISTINGUISHING GERD FROM GER

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the term used to describe the passage of gastric contents, including stomach acid, fluids, and food, into the esophagus, with or without regurgitation or vomiting.6 GER is a normal, common physiologic process among infants, in whom frequent feedings, small stomach size, and predominance of the recumbent position allow reflux to occur during transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter.6-9

Healthy infants and children may have asymptomatic episodes of GER; or episodes may be short, lasting less than three minutes, and occurring postprandially.6 Only when GER involves blood loss, esophagitis, strictures, nutritional deficits, and/or apnea should GERD be considered.9

The pathologic process known as GERD involves persistent, troublesome symptoms resulting from continued mucosal exposure to stomach acid, damaging the lining of the esophagus and possibly leading to erosive esophagitis.6,10,11 Endoscopic findings indicating GERD-associated esophageal damage include visible tears in the esophageal mucosa near the gastroesophageal junction6 (see Figure 1). In one single-center US study, almost 30% of patients with pediatric GERD who underwent endoscopy had erosive esophagitis.4

Continued on next page >>

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of GERD vary among adults and children in different age-groups. According to the Montreal definition, which was developed and modified by an international panel of pediatric gastroenterologists,10,12 GERD should be suspected in infants and toddlers who fail to thrive and exhibit the symptoms listed in Table 1.10,12 Clinicians should also consider GERD in older children and adolescents who present with heartburn, since it is the most common initial presenting symptom.10,13 Of note, a 2010 database study of UK children with GERD revealed a high incidence before age 1 year and the greatest incidence among 16- to 17-year-olds.5

GERD should also be considered in pediatric patients who complain of vague symptoms of “stomachache” or nausea, abdominal pain or chest pain, since children may have trouble describing the sensation of heartburn.6,10 Children may also present with extra-esophageal complaints, such as dry cough, asthma-like symptoms, sore throat, hoarseness, sleep apnea, or dysphagia, all of which can be complications of GERD.10,11 Researchers have suggested that GERD contributes to and/or exacerbates pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, and chronic cough.6,10 Therefore, clinicians should consider GERD in children with these seemingly unrelated illnesses.

Continued on next page >>

RISK FACTORS

Certain pediatric groups are at increased risk for severe GERD, with or without complications. Neurologic impairment can cause dysphagia, and anatomic abnormalities such as hiatal hernia can impair lower esophageal sphincter function, allowing acid to rise into the esophagus.6,11 Table 26,10,13 lists illnesses and congenital conditions that are considered predisposing factors for severe, chronic GERD.

When seeing patients in these populations, clinicians should specifically focus on relevant GI symptoms during the history and physical exam. Clinicians should also consider long-term monitoring for complications or changes that might indicate new-onset GERD.

Overweight and Obesity

Although data are limited on the relationship between pediatric GERD and obesity,14 associated research findings seem to conflict with the established relationship in adult patients. While certain study groups found an association between obesity, elevated BMI, and increased waist circumference with an increase in symptoms of GERD (eg, regurgitation, heartburn),15,16 others found no significant correlation between overweight and reflux esophagitis.14,17 Notably, one analysis found a significant correlation between male gender and incidence of GERD.17

Although the evidence is not conclusive, clinicians are encouraged to counsel the older children among their patients on the benefits of weight and BMI reduction—encouraging them to achieve an overall healthier lifestyle and avoid diseases associated with excess weight.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In infants with unusual symptoms, certain GI conditions such as obstructive disorders (eg, pyloric stenosis), motility disorders, and peptic ulcer disease must be ruled out with further diagnostic testing.6,7 Red-flag symptoms that warrant further investigation include hematemesis, hematochezia, diarrhea, abdominal tenderness or distention, constipation, bilious vomiting, onset of vomiting after age 6 months, failure to thrive, macrocephaly or microcephaly, fever, lethargy, and hepatosplenomegaly.6,7 More common differentials are described below.

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Eosinophilic esophagitis is an inflammatory condition of the esophagus, an apparent manifestation of food allergy (eg, milk protein), characterized by infiltrating mucosal eosinophils.6,18 First identified in children (though also occurring in adults), eosinophilic esophagitis is recognized as a more common cause of dysphagia than GERD.6

This recently discovered disease is often mistaken for GERD. While symptoms including heartburn and dysphagia occur in both conditions, eosinophilic esophagitis can only be diagnosed via multiple endoscopic mucosal biopsies. Corticosteroid therapy has been found to be a more effective treatment for this condition than acid suppression therapy.19

Current research is focused on a possible link between eosinophilic esophagitis and autoimmune disease, as many affected patients also have asthma, allergic rhinitis, and/or eczema.19 The increasing prevalence of childhood allergies should prompt clinicians to place eosinophilic esophagitis on the short list of differentials when evaluating a child for GERD-type symptoms. Referral for evaluation by an allergist may also be beneficial.

Asthma

GER may actually trigger asthma in some patients, even without symptoms of GERD.6 While there is support for a possible link between GERD and asthma in infants and children, a definitive relationship cannot be confirmed without more reliable studies.20 However, clinicians must not overlook the possibility of GERD in a child who presents with symptoms indicative of asthma, such as wheezing, shortness of breath, coughing, and chest tightness.

Other Extra-Esophageal Diseases

Concern exists over apparent associations between GERD and other extra-esophageal illnesses. In addition to asthma, the Montreal consensus group10,12 found a connection between GERD and other respiratory conditions, including chronic cough and chronic laryngitis. These conditions usually represent multifactorial disease processes, researchers state, and GER can be an exacerbating factor rather than an actual cause of these conditions.5,10

Further manifestations of extra-esophageal GERD include pneumonia, bronchiectasis, any apparent life-threatening event, laryngotracheitis, sinusitis, and dental erosion. Again, causality has not been clearly established, and the shortage of high-quality studies with adequate sample sizes makes it impossible to confirm clear relationships.21 It is therefore prudent for clinicians to evaluate any child with these non-GI conditions for reflux disease.

Continued on next page >>

EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

In 2009, the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN)6 released international guidelines for the management of pediatric GERD, including evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Making a diagnosis of GERD in an infant or a toddler can be challenging, since no reliable pathognomonic symptoms are known. Older children and adolescents are better able to articulate their presenting symptoms (which resemble those of adults); thus, a detailed history and physical exam are ordinarily adequate to diagnose GERD and introduce treatment in these patients.6

The diagnostic tool that is considered the gold standard for pediatric patients, including infants, is 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring. This test directly measures the quantity of acid present in the esophagus by way of an internal probe that is passed through the mouth or nose and worn for 24 hours. Esophageal pH monitoring quantifies the amount of acid to which the esophagus is exposed over this time period, compared with standard pediatric values.6,13

However, a newer combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring (MII/pH) tool offers advantages over esophageal pH monitoring, as it detects nonacidic or weakly acidic reflux events, in addition to more obvious episodes of acidic reflux.6,13,22

Clinical benefits of the MII/pH are:

• Better efficiency than pH monitoring alone in the evaluation of respiratory symptoms and GERD

• Ability to correlate timing of reflux episodes with symptoms, including chronic cough, apnea, and other respiratory symptoms

• Improved accuracy in monitoring postprandial reflux episodes, which are typically less acidic.13,23

Additionally, MII/pH provides a graphic readout from which the duration, height, and frequency of the reflux episodes can be analyzed. Currently, the chief disadvantage to its use is the absence of standardized pediatric values.13

Endoscopic biopsy should not be used to establish whether esophagitis is due to reflux. Endoscopically visible breaks in the distal esophageal mucosa are the most reliable indicators of reflux esophagitis. However, because other signs, such as mucosal erythema, pallor, and vascular patterns have normal variations, they cannot be considered evidence of reflux esophagitis.6 Endoscopic biopsy is mainly recommended for confirmation of suspected Barrett’s esophagus (which is rare in children) or for eosinophilic esophagitis, as it can confirm infiltrating mucosal eosinophils.6,19

Nuclear scintigraphy uses imaging to time the passage of a radioisotope-labeled meal through the upper GI tract. It can provide information about gastric emptying, which may be delayed in children with GERD. It may also be useful in diagnosing aspiration in patients with chronic intractable respiratory symptoms.6 Because standardized techniques and age-specific norms are lacking, however, nuclear scintigraphy is not recommended for patients with other potentially reflux-related symptoms. The sensitivity of this test is low, and negative results may not exclude the possibility of reflux and aspiration.6

Barium contrast radiography (upper GI series) is not recommended due to its poor sensitivity and specificity. This test is useful for confirming anatomic anomalies, however.6

For infants and toddlers with symptoms suggestive of GERD, the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN authors6 find no evidence to support an empiric trial of pharmacologic treatment to confirm the diagnosis. For older, verbal children and adolescents who present with heartburn and/or chest pain, a short-term trial (as long as 4 weeks) of acid suppressants may be used to identify acid reflux as the cause of these symptoms.

Based on the guidelines by Vandenplas et al,6 a clinician’s initial approach to evaluation for GERD and its diagnosis should begin with a thorough history and physical exam and the least invasive diagnostic process possible. The child’s specific symptoms and suspected involvement of other organ systems will dictate the use of progressively invasive diagnostic strategies.

MANAGEMENT OF GERD

Conservative Treatment

Nonpharmacologic, age-appropriate approaches focus on diet and lifestyle changes. An effective treatment option for infants uses dry rice cereal to thicken the formula, resulting in decreased visible reflux and regurgitation.6,8 Recommended amounts of thickened formula are 4 oz/kg/d, divided into four to eight daily feedings, depending on the age of the patient; infants close to 1 year require only four feedings.8 For breastfed infants, expressed breast milk can be thickened with rice cereal and given at comparable volumes.8

Recommendations from the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN clinical practice guidelines6 include a two- to four-week trial of an extensively hydrolyzed protein formula for formula-fed infants who vomit frequently. These formulas are considered hypoallergenic and contain shorter protein particles, allowing for easier digestion.8

Lifestyle changes recommended for adults with GERD can also be tailored for use in pediatric patients (see Table 38,11). They include avoidance of overfeeding by giving smaller portions at greater frequency (as described above), avoidance of foods known to cause GERD symptoms, avoidance of cigarette smoke, restriction of eating and drinking close to bedtime, elevation of the head of the bed or crib (use of a pillow is not recommended in children younger than 1 year), and a left-sided sleeping position for adolescents.6,11

Holding infants upright for 30 minutes after feeding with ample burping may reduce reflux.11 In infants, the prone position provides the greatest benefit for reducing acid reflux, according to findings from one study based on pH monitoring.13 Nonetheless, the association between prone positioning and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) has led to recommendations of supine position when infants sleep unobserved.6 Perhaps supervised “tummy time” several times per day (eg, after feeding) can help reduce GERD symptoms in infants.

Finally, breastfeeding mothers are advised to avoid consuming cow’s milk, eggs, and soy products, as their presence in breast milk may promote reflux in an infant with unrecognized food allergy.6,8

Pharmacologic Treatment

Since esophagitis develops as a result of continuous acid exposure from the refluxate, the primary pharmacologic therapy for the treatment of GERD is aimed at acid reduction in the upper GI tract. Current pharmacologic options include histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).6 H2RAs have been shown to alleviate symptoms and promote mucosal healing. To their disadvantage, long-term use of H2RAs may lead to drug tolerance.

PPIs are superior to H2RAs in symptom relief and esophageal healing without causing tolerance; however, although certain agents are FDA approved for treatment of children age 1 year or older with GERD (including esomeprazole, lansoprazole, and omeprazole), use of PPIs in infants younger than 1 year is controversial.6,13 (See “New Solution for Pediatric GERD?”24,25)

According to results from existing studies of PPI use in infants with GERD ages 34 weeks to 1 year, PPIs are no more effective at symptom reduction than placebo.2,26 Further, data to demonstrate efficacy of long-term PPI use in infants and toddlers are scant.6,27 Safety results from various trials are inconsistent, ranging from no reported adverse effects to rare but severe adverse events, including necrotizing enterocolitis in infants, and lower respiratory tract infections, community-acquired pneumonia, gastric polyps, and acute gastroenteritis in children.2,26

The most common adverse effects of esomeprazole use in infants and children are nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, pyrexia, and headache.4,6 Because of these potential risks, none of the PPIs is approved for use in infants younger than 1 year. However, a short-term PPI trial for as long as 4 weeks (along with lifestyle changes) for symptom reduction in older children is recommended by the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN clinical practice guidelines.2,6,13

Also based on the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN guidelines,6 empiric PPI therapy is not recommended in pediatric patients presenting with wheezing or asthma. One research team has reported that asthma symptoms may be validly treated with a PPI in patients who do not respond to standard asthma treatment and who have a high reflux index.28 However, an absence of studies to support this finding makes a firm recommendation impossible.

According to the NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN guidelines,6 there is insufficient evidence to justify the use of prokinetic agents (eg, metoclopramide, erythromycin, bethanechol, domperidone) for pediatric GERD, as their potential risks outweigh their potential benefits. Neither are alginates nor sucralfate recommended for long-term therapy, because PPIs and H2RAs are considered more effective.6

Surgical Treatment

As with adults, surgery should be a last resort for treatment. Antireflux surgery is deemed appropriate only in children who cannot tolerate long-term medical therapy due to life-threatening complications, who cannot comply with the treatment schedule, or in whom medications have been found ineffective.6

The gold standard for the surgical treatment of GERD is laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, a procedure in which the shape of the stomach fundus is modified to provide strength and functional support to the lower esophageal sphincter.29 Although children with heartburn, asthma, nocturnal asthma symptoms, or steroid-dependent asthma have been found to benefit clinically from long-term medical therapy or antireflux surgery, the comparable benefits of surgical versus medical treatment in these children is unknown.6

Continued on next page >>

PROGNOSIS AND FOLLOW-UP

The large majority of infants respond well to conservative nonpharmacologic treatment and outgrow their reflux symptoms by age 1 year, with maturation of muscle control and lower esophageal sphincter function.7 Further testing and intervention is generally not required in healthy infants, and parents should be reassured by this information.6,7 If regurgitation does not resolve by age 12 to 18 months, or if red-flag symptoms develop, referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist is recommended.6

For older children and adolescents with GERD, lifestyle changes should be implemented first, followed by short-term pharmacologic intervention, as recommended by appropriate guidelines.

Children with other illnesses or complications, such as neurologic impairment, premature birth, or a strong family history of severe GERD, have a poorer prognosis and may require more aggressive diagnostic evaluation and management.7 Complications such as esophageal stricture and Barrett’s esophagus, which poses an increased risk for adenocarcinoma, require referral to a specialist for further evaluation.10

CONCLUSION

GERD is no longer a condition found only in adults. Since primary care practitioners are increasingly likely to see GERD in their pediatric patients, it is important for these clinicians to become familiar with the contributing factors, definitive signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of GERD. Children at high risk for GERD should be followed closely and introduced to appropriate lifestyle modifications to avoid the troublesome symptoms of GERD and its complications, whenever possible. In the differential diagnosis, respiratory illnesses and other extra-esophageal diseases, as well as eosinophilic esophagitis in allergic patients, should be considered.

Practitioners should consult the 2009 NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN clinical practice guidelines for further details regarding the evaluation, diagnosis, preferred treatment, management of pediatric GERD, and indications for specialist referral. Research is ongoing in many areas, including the suitability of PPI use in pediatrics. More research is needed to clarify the theorized link between GERD and asthma.

1. Diaz DM, Winter HS, Colletti RB, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practice styles of North American pediatricians regarding gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:56-64.

2. van der Pol RJ, Smits MJ, van Wijk MP, et al. Efficacy of proton-pump inhibitors in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:925-935.

3. Nelson SP, Kothari S, Wu EQ, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux disease and acid-related conditions: trends in incidence of diagnosis and acid suppression therapy. J Med Econ. 2009;12:348-355.

4. Tolia V, Gilger MA, Barker PN, Illueca M. Healing of erosive esophagitis and improvement of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease after esomeprazole treatment in children 12 to 36 months old. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:593-598.

5. Vakil N. Disease definition, clinical manifestations, epidemiology and natural history of GERD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:759-764.

6. Vandenplas Y, Rudolph CD, Di Lorenzo C, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:498-547.

7. Michail S. Gastroesophageal reflux. Pediatr Rev. 2007;28:101-111.

8. Orenstein SR, McGowan JD. Efficacy of conservative therapy as taught in the primary care setting for symptoms suggesting infant gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. 2008;152:310-314.

9. Vandenplas Y, Lifshitz JZ, Orenstein S, et al. Nutritional management of regurgitation in infants. J Am Coll Nutr. 1998;17:308-316.

10. Sherman PM, Hassall E, Fagundes-Neto U, et al. A global, evidence-based consensus on the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the pediatric population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1278-1295.

11. Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. Heartburn, gastroesophageal reflux (GER), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)(2007). http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/gerd. Accessed April 4, 2013.

12. Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et al; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920.

13. Bharwani S. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in children: from infancy to adolescence. J Med Sci. 2011;4:25-39.

14. Patel NR, Ward MJ, Beneck D, et al. The association between childhood overweight and reflux esophagitis. J Obes. 2010;2010.

15. Quitadamo P, Buonavolontà R, Miele E, et al. Total and abdominal obesity are risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:72-75.

16. Pashankar DS, Corbin Z, Shah SK, Caprio S. Increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in obese children evaluated in an academic medical center. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:410-413.