User login

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has presented physicians with a challenge by adding the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to its protective roster for a subset of high-risk adults.

It’s wonderful that we have a new prevention tool. The question is how to ensure that it’s implemented when we are still far from perfect in fulfilling longstanding adult vaccination recommendations for the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). There are strategies and resources that can help us meet the pneumococcal vaccination needs of our patients, whether they require one or both vaccines.

The new recommendations call for one dose of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), in addition to PPSV23, for adults with immunocompromising conditions (including HIV infection), functional or anatomic asplenia, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, or cochlear implants (MMWR 2012;61:816-19). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices did not change recommendations for other adults. Adults who are at least 65 years old who smoke or have chronic conditions such as alcoholism, asthma, diabetes, or heart disease should receive PPSV23 only.

These recommendations are in place for good reason. Case fatality rates for pneumococcal bacteremia and meningitis are as high as 20%-30%. Pneumococcal pneumonia is less dangerous, with mortality of 5%-7%, but it is much more prevalent, leading to 175,000 hospitalizations in the United States annually.

Adults with chronic conditions such as diabetes and heart disease have up to ten times as great a risk for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), compared with healthy individuals. For immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV or cancer, the risk is 173 and 186 times greater, respectively (J. Infect. Dis. 2005;192:377-86). Every effort should be made to protect these adults from pneumococcal infection.

Vaccination provides the best chance of protection against invasive disease, yet compliance is low. According to the most recent National Health Interview Survey data, 64.7% of adults who are at least 65 years old have received a pneumococcal vaccination, up from 59.7% in 2010. We are still a long way from reaching Healthy People 2020 objectives. Rates among younger adults are even more disappointing. Only 18.5% of working-age adults with a pneumococcal vaccine indication have received it (MMWR 2012;61:66-72).

Another reason for pneumococcal vaccination is that secondary bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia can be a major complication of flu. Pneumococcal vaccine, which can be administered at the same time as flu vaccine, may have an impact on this life-threatening complication.

There are many strategies that health care professionals can implement to address this public health problem (Postgrad. Med. 2012;124:71-79). A good place to start is to become familiar with the recommendations, educate caregivers, and engage clinical and ancillary staff in screening and vaccinating patients as appropriate (National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, Pneumococcal Vaccination Is Everyone’s Responsibility, April 2012).

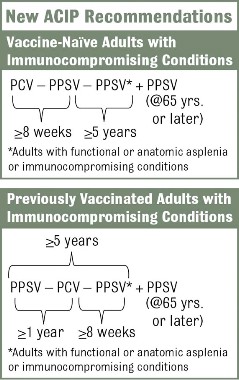

The vaccination approach, including potential sequencing of PCV13 and PPSV23, varies depending on a patient’s risk condition and history. Vaccine-naive adults with an indication for PPSV23 should receive only a first dose immediately, with a second dose at age 65 years (or later if less than 5 years has elapsed). Dosing for those with a PCV13 indication is more complicated, but the sequence is outlined in several resources, including an Adult Pneumococcal Vaccination Guide.

Further, every pneumococcal discussion opens the door for identifying other vaccination needs such as influenza, Tdap, and hepatitis B, which is now indicated for adults aged 19-59 years with diabetes (MMWR 2011;60:1709-11). Tools to support these efforts are available at the NFID, the CDC, and the Immunization Action Coalition.

Dr. Rehm is medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases and vice chair of the department of infectious diseases at the Cleveland Clinic. She is a member of advisory boards for Becton Dickenson, Merck, and Pfizer.

Dr. File is president of NFID and chair of the division of infectious disease at Summa Health System in Akron, Ohio. He is a consultant and/or a member of advisory boards for Astellas, Bayer, Cerexa/Forest, DaiichiSankyo, Durata, GSK, Merck, Pfizer, and Tetraphase.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has presented physicians with a challenge by adding the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to its protective roster for a subset of high-risk adults.

It’s wonderful that we have a new prevention tool. The question is how to ensure that it’s implemented when we are still far from perfect in fulfilling longstanding adult vaccination recommendations for the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). There are strategies and resources that can help us meet the pneumococcal vaccination needs of our patients, whether they require one or both vaccines.

The new recommendations call for one dose of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), in addition to PPSV23, for adults with immunocompromising conditions (including HIV infection), functional or anatomic asplenia, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, or cochlear implants (MMWR 2012;61:816-19). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices did not change recommendations for other adults. Adults who are at least 65 years old who smoke or have chronic conditions such as alcoholism, asthma, diabetes, or heart disease should receive PPSV23 only.

These recommendations are in place for good reason. Case fatality rates for pneumococcal bacteremia and meningitis are as high as 20%-30%. Pneumococcal pneumonia is less dangerous, with mortality of 5%-7%, but it is much more prevalent, leading to 175,000 hospitalizations in the United States annually.

Adults with chronic conditions such as diabetes and heart disease have up to ten times as great a risk for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), compared with healthy individuals. For immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV or cancer, the risk is 173 and 186 times greater, respectively (J. Infect. Dis. 2005;192:377-86). Every effort should be made to protect these adults from pneumococcal infection.

Vaccination provides the best chance of protection against invasive disease, yet compliance is low. According to the most recent National Health Interview Survey data, 64.7% of adults who are at least 65 years old have received a pneumococcal vaccination, up from 59.7% in 2010. We are still a long way from reaching Healthy People 2020 objectives. Rates among younger adults are even more disappointing. Only 18.5% of working-age adults with a pneumococcal vaccine indication have received it (MMWR 2012;61:66-72).

Another reason for pneumococcal vaccination is that secondary bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia can be a major complication of flu. Pneumococcal vaccine, which can be administered at the same time as flu vaccine, may have an impact on this life-threatening complication.

There are many strategies that health care professionals can implement to address this public health problem (Postgrad. Med. 2012;124:71-79). A good place to start is to become familiar with the recommendations, educate caregivers, and engage clinical and ancillary staff in screening and vaccinating patients as appropriate (National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, Pneumococcal Vaccination Is Everyone’s Responsibility, April 2012).

The vaccination approach, including potential sequencing of PCV13 and PPSV23, varies depending on a patient’s risk condition and history. Vaccine-naive adults with an indication for PPSV23 should receive only a first dose immediately, with a second dose at age 65 years (or later if less than 5 years has elapsed). Dosing for those with a PCV13 indication is more complicated, but the sequence is outlined in several resources, including an Adult Pneumococcal Vaccination Guide.

Further, every pneumococcal discussion opens the door for identifying other vaccination needs such as influenza, Tdap, and hepatitis B, which is now indicated for adults aged 19-59 years with diabetes (MMWR 2011;60:1709-11). Tools to support these efforts are available at the NFID, the CDC, and the Immunization Action Coalition.

Dr. Rehm is medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases and vice chair of the department of infectious diseases at the Cleveland Clinic. She is a member of advisory boards for Becton Dickenson, Merck, and Pfizer.

Dr. File is president of NFID and chair of the division of infectious disease at Summa Health System in Akron, Ohio. He is a consultant and/or a member of advisory boards for Astellas, Bayer, Cerexa/Forest, DaiichiSankyo, Durata, GSK, Merck, Pfizer, and Tetraphase.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has presented physicians with a challenge by adding the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to its protective roster for a subset of high-risk adults.

It’s wonderful that we have a new prevention tool. The question is how to ensure that it’s implemented when we are still far from perfect in fulfilling longstanding adult vaccination recommendations for the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). There are strategies and resources that can help us meet the pneumococcal vaccination needs of our patients, whether they require one or both vaccines.

The new recommendations call for one dose of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), in addition to PPSV23, for adults with immunocompromising conditions (including HIV infection), functional or anatomic asplenia, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, or cochlear implants (MMWR 2012;61:816-19). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices did not change recommendations for other adults. Adults who are at least 65 years old who smoke or have chronic conditions such as alcoholism, asthma, diabetes, or heart disease should receive PPSV23 only.

These recommendations are in place for good reason. Case fatality rates for pneumococcal bacteremia and meningitis are as high as 20%-30%. Pneumococcal pneumonia is less dangerous, with mortality of 5%-7%, but it is much more prevalent, leading to 175,000 hospitalizations in the United States annually.

Adults with chronic conditions such as diabetes and heart disease have up to ten times as great a risk for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), compared with healthy individuals. For immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV or cancer, the risk is 173 and 186 times greater, respectively (J. Infect. Dis. 2005;192:377-86). Every effort should be made to protect these adults from pneumococcal infection.

Vaccination provides the best chance of protection against invasive disease, yet compliance is low. According to the most recent National Health Interview Survey data, 64.7% of adults who are at least 65 years old have received a pneumococcal vaccination, up from 59.7% in 2010. We are still a long way from reaching Healthy People 2020 objectives. Rates among younger adults are even more disappointing. Only 18.5% of working-age adults with a pneumococcal vaccine indication have received it (MMWR 2012;61:66-72).

Another reason for pneumococcal vaccination is that secondary bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia can be a major complication of flu. Pneumococcal vaccine, which can be administered at the same time as flu vaccine, may have an impact on this life-threatening complication.

There are many strategies that health care professionals can implement to address this public health problem (Postgrad. Med. 2012;124:71-79). A good place to start is to become familiar with the recommendations, educate caregivers, and engage clinical and ancillary staff in screening and vaccinating patients as appropriate (National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, Pneumococcal Vaccination Is Everyone’s Responsibility, April 2012).

The vaccination approach, including potential sequencing of PCV13 and PPSV23, varies depending on a patient’s risk condition and history. Vaccine-naive adults with an indication for PPSV23 should receive only a first dose immediately, with a second dose at age 65 years (or later if less than 5 years has elapsed). Dosing for those with a PCV13 indication is more complicated, but the sequence is outlined in several resources, including an Adult Pneumococcal Vaccination Guide.

Further, every pneumococcal discussion opens the door for identifying other vaccination needs such as influenza, Tdap, and hepatitis B, which is now indicated for adults aged 19-59 years with diabetes (MMWR 2011;60:1709-11). Tools to support these efforts are available at the NFID, the CDC, and the Immunization Action Coalition.

Dr. Rehm is medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases and vice chair of the department of infectious diseases at the Cleveland Clinic. She is a member of advisory boards for Becton Dickenson, Merck, and Pfizer.

Dr. File is president of NFID and chair of the division of infectious disease at Summa Health System in Akron, Ohio. He is a consultant and/or a member of advisory boards for Astellas, Bayer, Cerexa/Forest, DaiichiSankyo, Durata, GSK, Merck, Pfizer, and Tetraphase.