User login

CASE: Gynecologist accused of placing an IUD without performing a pregnancy test

A 34-year-old woman (G4 P3013) presents to her gynecologist for planned placement of the Mirena Intrauterine System (Bayer HealthCare). She was divorced 2 months ago and is interested in birth control. She smokes 1.5 packs per day, and her history includes irregular menses, an earlier Pap smear result of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) with negative colposcopy results, polycystic ovary syndrome, obesity, migraine headaches with aura, bilateral carpel tunnel surgery, and a herniated L4.5 disc treated conservatively. She has no history of any psychiatric problems.

One week before intrauterine device (IUD) placement, she discussed the options with her gynecologist and received a Mirena patient brochure. At the office visit for IUD placement, the patient stated she had a negative home pregnancy test 1 week earlier. She did not tell the gynecologist that she had taken Plan B One-Step (levonorgestrel, 1.5 mg) emergency contraception 2 weeks prior to presenting to her gynecologist after receiving it from a Planned Parenthood office following condom breakage during coitus. IUD placement was uncomplicated.

After noting spotting several weeks later, she contacted her gynecologist’s office. Results of an office urine pregnancy test were positive; the serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level was reported at 65,000 mIU/mL.The results of a pelvic sonogram showed a 12 5/7-week intrauterine gestation. The gynecologist unsuccessfully tried to remove the IUD. Options for termination or continuation of the pregnancy were discussed. The patient felt the gynecologist strongly encouraged, “almost insisting on,” termination. Termination could not be performed locally as her state laws did not allow second trimester abortion; the gynecologist provided out-of-state clinic options.

The patient aborted the pregnancy in a neighboring state. She was opposed to the termination but decided it was not a good time for her to have a baby. She felt the staff at the facility were “cold” and had a “we got to get this done attitude.” As she left the clinic, she saw people picketing outside and found the whole process “psychologically traumatic.” When bleeding persisted, she sought care from another gynecologist. Pelvic sonography results showed retained products of conception (POC). The new gynecologist performed operative hysteroscopy to remove the POC. The patient became depressed and felt as if she was a victim of pain and suffering.

The patient’s attorney filed a medical malpractice claim against the gynecologist who inserted the IUD, accusing her of negligence for not performing a pregnancy test immediately before IUD insertion.

In a deposition, the patient stated she bought the home pregnancy test in a “dollar store” and was worried about its accuracy, but never told the gynecologist. Conception probably occurred 2 weeks prior to IUD insertion, correlating with the broken condom and taking of Plan B. She did not think the gynecologist needed to know this as it “would not have made any difference in her care.”

The gynecologist confirmed that the patient’s record included “Patient stated ‘pregnancy test negative within 1 week of IUD placement.’” The gynecologist did not feel that obtaining the date of the patient’s last menstrual period (LMP) was required since she asked if the patient had protected coitus since her LMP and the patient answered yes. The gynecologist thought that if a pregnancy were in utero, Mirena placement would prevent implantation. She believed that she had obtained proper informed consent and that the patient acknowledged receiving and reading the Mirena patient information prior to placement. The gynecologist stated she also provided other birth control options.

The patient’s expert witness testified that the gynecologist fell below the standard of care by not obtaining a pregnancy test prior to IUD insertion.

The gynecologist’s expert witness argued that the patient told the gynecologist that she did not have unprotected coitus. The patient herself withheld information from the gynecologist that she had taken Plan B due to condom breakage. The physician’s attorney also noted that the pelvic exam at time of IUD placement was normal.

What’s the verdict?

The patient has a fairly good case. The gynecologist may not have been sufficiently careful, given all of the facts in this case, to ensure that the patient was not pregnant. An expert is testifying that this fell below the acceptable level of care in the profession. At the same time, the failure of the patient to reveal some information may result in reduced damages through “comparative negligence.” Because there will be several questions of fact for a jury to decide, as well as some emotional elements in this case, the outcome of a trial is uncertain. This suggests that a negotiated settlement before trial should be considered.

Read about medical considerations of a pregnancy with an IUD.

Medical considerations

First, some background information on Mirena.

Indications for Mirena

Here are indications for Mirena1:

- intrauterine contraception for up to 5 years

- treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding for women who choose to use intrauterine contraception as their method of contraception.

Prior to insertion, the following are recommended2:

- a complete medical and social history should be obtained to determine conditions that might influence the selection of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG IUS) for contraception

- if indicated, perform a physical examination, and appropriate tests for any forms of genital or other sexually transmitted infections

- there is no requirement for prepregnancy test.

Contraindications for Mirena

Contraindications for Mirena include2:

- pregnancy or suspicion of pregnancy; cannot be used for postcoital contraception

- congenital or acquired uterine anomaly including fibroids if they distort the uterine cavity

- acute pelvic inflammatory disease or a history of pelvic inflammatory disease unless there has been a subsequent intrauterine pregnancy

- postpartum endometritis or infected abortion in the past 3 months

- known or suspected uterine or cervical neoplasia

- known or suspected breast cancer or other progestin-sensitive cancer, now or in the past

- uterine bleeding of unknown etiology

- untreated acute cervicitis or vaginitis, including bacterial vaginosis or other lower genital tract infections until infection is controlled

- acute liver disease or liver tumor (benign or malignant)

- conditions associated with increased susceptibility to pelvic infections

- a previously inserted IUD that has not been removed

- hypersensitivity to any component of this product.

Is Mirena a postcoital contraceptive?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) bulletin on long-acting reversible contraception states “the levonorgestrel intrauterine system has not been studied for emergency contraception.”3 Ongoing studies are comparing the levonor‑gestrel IUD to the copper IUD for emergency contraception.4

Related Article:

Webcast: Emergency contraception: How to choose the right one for your patient

Accuracy of home pregnancy tests

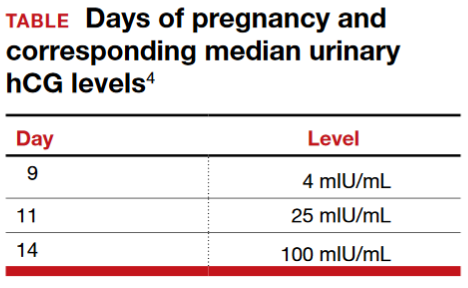

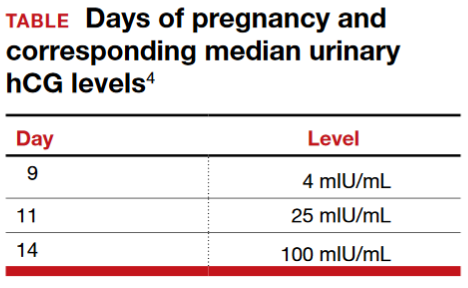

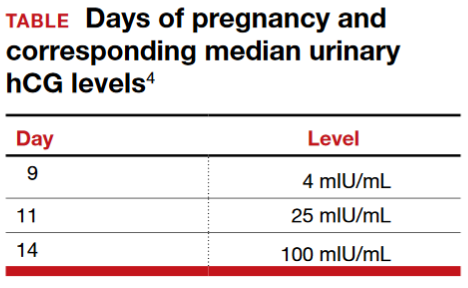

Although the first home pregnancy test was introduced in 1976,5 there are now several home pregnancy tests available over the counter, most designed to detect urinary levels of hCG at ≥25 mIU/mL. The tests identify hCG, hyperglycosylated hCG, and free Betasubunit hCG in urine. When Cole and colleagues evaluated the validity of urinary tests including assessment of 18 brands, results noted that sensitivity of 12.4 mIU/mL of hCG detected 95% of pregnancies at time of missed menses.6 Some brands required 100 mIU/mL levels of hCG for positive results. The authors concluded “the utility of home pregnancy tests is questioned.”6 For urinary levels of hCG, see TABLE.

Pregnancy with an IUD

The gynecologist’s concern about pregnancy when an IUD is inserted was valid.

With regard to pregnancy with Mirena in place, the full prescribing information states2:

Intrauterine Pregnancy: If pregnancy occurs while using Mirena, remove Mirena because leaving it in place may increase the risk of spontaneous abortion and preterm labor. Removal of Mirena or probing of the uterus may also result in spontaneous abortion. In the event of an intrauterine pregnancy with Mirena, consider the following:

Septic abortion

In patients becoming pregnant with an IUD in place, septic abortion - with septicemia, septic shock, and death may occur.

Continuation of pregnancy

If a woman becomes pregnant with Mirena in place and if Mirena cannot be removed or the woman chooses not to have it removed, warn her that failure to remove Mirena increases the risk of miscarriage, sepsis, premature labor and premature delivery. Follow her pregnancy closely and advise her to report immediately any symptom that suggests complications of the pregnancy.

Concern for microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity must be considered. Kim and colleagues addressed pregnancy prognosis with an IUD in situ in a retrospective study of 12,297 pregnancies; 196 had an IUD with singleton gestation.7 The study revealed a higher incidence of histologic chorioamnionitis and/or funisitis when compared with those without an IUD (54.2% vs 14.7%, respectively; P<.001). The authors concluded that pregnant women with an IUD in utero are at very high risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Brahmi and colleagues8 reported similar risks with higher incidence of spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, and septic abortion.

Related Article:

Overcoming LARC complications: 7 case challenges

Efficacy and safety concerns with emergency contraception

The efficacy and safety of emergency contraception using levonorgestrel oral tablets (Plan B One-Step; Duramed Pharmaceuticals) is another concern. Plan B One-Step should be taken orally as soon as possible within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse or a known or suspected contraceptive failure. Efficacy is better if Plan B is taken as soon as possible after unprotected intercourse. There are 2 dosages: 1 tablet of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg or 2 tablets of levonorgestrel 0.75 mg. The second 0.75-mg tablet should be taken 12 hours after the first dose.9

Plan B can be used at any time during the menstrual cycle. In a series of 2,445 women aged 15 to 48 years who took levonorgestrel tablets for emergency contraception (Phase IV clinical trial), 5 pregnancies occurred (0.2%).10

ACOG advises that emergency contraception using a pill or the copper IUD should be initiated as soon as possible (up to 5 days) after unprotected coitus or inadequately protected coitus.9

Retained products of contraception

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 135 on complications associated with second trimesterabortion discusses retained POC.11 The approach to second trimester abortion includes dilation and evacuation (D&E) as well as medical therapy with mifepristone and misoprostol. D&E, a safe and effective approach with advantages over medical abortion, is associated with fewer complications (up to 4%) versus medical abortion (29%); the primary complication is retained POC (placenta).11

Read about the legal considerations of this case.

Legal considerations

The malpractice lawsuit filed in this case claims that the gynecologist failed to exercise the level of care of a reasonably prudent practitioner under the circumstances and was therefore negligent or in breach of a duty to the patient.

First, a lawyer would look for a medical error that was related to some harm. Keep in mind that not all medical errors are negligent or subject to liability. Many medical errors occur even though the physician has exercised all reasonable care and engaged in sound practice, given today’s medical knowledge and facilities. When harm is caused through medical error that was careless or otherwise does not meet the standard of care, financial recovery is possible for the patient through a malpractice claim.12

In this case, the expert witnesses’ statements focus on the issue of conducting a pregnancy test prior to IUD insertion. The patient’s expert testified that failure to perform a pregnancy test was below an acceptable standard of care. That opinion may have been based on the typical practice of gynecologists, widely accepted medical text books, and formal practice standards of professional organizations.13

Cost-benefit analysis. Additional support for the claim that not performing the pregnancy test is negligent comes from applying a cost-benefit analysis. In this analysis, the risks and costs of performing a pregnancy test are compared with the benefits of doing the test.

In this case, the cost of conducting the pregnancy test is very low: essentially risk-freeand relatively inexpensive. On the other hand, the harm that could be avoided would be significant. Kim and colleagues suggest that pregnant women with an IUD in utero are at very high risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes.7 Given that women receiving IUDs are candidates for pregnancy (and perhaps do not know they are pregnant), a simple, risk-free pregnancy test would seem to be an efficient way to avoid a nontrivial harm.14

Did she have unprotected sex? The gynecologist’s expert notes that the patient told the gynecologist that she did not have unprotected coitus. Furthermore, the patient withheld from the gynecologist the information that she had taken Plan B because of a broken condom. Is this a defense against the malpractice claim? The answer is “possibly no,” or “possibly somewhat.”

As for unprotected coitus, the patient could easily have misunderstood the question. Technically, the answer “no” was correct. She had not had unprotected sex—it is just that the protection (condom) failed. It does not appear from the facts that she disclosed or was asked about Plan B or other information related to possible failed contraception. As to whether the patient’s failure to provide that information could be a defense for the physician, the best answer is “possibly” and “somewhat.” (See below.)15

Withholding information. Patients, of course, have a responsibility to inform their physicians of information they know is relevant. Many patients, however, will not know what is relevant (or why), or will not be fully disclosing.

Professionals cannot ignore the fact that their patients and clients are often confused, do not understand what is important and relevant, and cannot always be relied upon. For that very reason, professionals generally are obliged to start with the proposition that they may not have all of the relevant information. In this case, this lack of information makes the cost-calculation of performing a pregnancy test that much more important. The risk of not knowing whether a patient is pregnant includes the fact that many patients just will not know or cannot say with assurance.16

A “somewhat” defense and comparative negligence

Earlier we referred to a “somewhat” defense. Almost all states now have some form of “comparative negligence,” meaning that the patient’s recovery is reduced by the proportion of the blame (negligence) that is attributed to the patient. The most common form of comparative negligence works this way: If there are damages of $100,000, and the jury finds that the fault is 20% the patient’s and 80% the physician’s, the patient would receive $80,000 recovery. (In the past, the concept of “contributory negligence” could result in the plaintiff being precluded from any recovery if the plaintiff was partially negligent—those days are mostly gone.)

Related Article:

Informed consent: The more you know, the more you and your patient are protected

Statement of risks, informed consent, and liability

The gynecologist must provide an adequate description of the IUD risks. The case facts indicate that appropriate risks were discussed and literature provided, so it appears there was probably appropriate informed consent in this case. If not true, this would provide another basis for recovery.

Two other aspects of this case could be the basis for liability. We can assume that the attempted removal of the IUD was performed competently.16 In addition, if the IUD was defective in terms of design, manufacture, or warnings, the manufacturer of the device could be subject to liability.17

Final verdict: Out of court settlement

Why would the gynecologist and the insurance company settle this case? After all, they have some arguments on their side, and physicians win the majority of malpractice cases that go to trial.18 On the other hand, the patient’s expert witness’ testimony and the cost-benefit analysis of the pregnancy test are strong, contrary claims.

Cases are settled for a variety of reasons. Litigation is inherently risky. In this case, we assume that the court denied a motion to dismiss the case before trial because there is a legitimate question of fact concerning what a reasonably prudent gynecologist would have done under the circumstances. That means a jury would probably decide the issue of medical judgment, which is generally disconcerting. Furthermore, the comparative negligence defense that the patient did not tell the gynecologist about the failed condom/Plan B would most likely reduce the amount of damages, but not eliminate liability. The questions regarding the pressure to terminate a second trimester pregnancy might well complicate a jury’s view.

Other considerations include the high costs in time, money, uncertainty, and disruption associated with litigation. The settlement amount was not stated, but the process of negotiating a settlement would allow factoring in the comparative negligence aspect of the case. It would be reasonable for this case to settle before trial.

Should the physician have apologized before trial? The gynecologist could have sent a statement of regret or apology to the patient before a lawsuit was filed. Most states now have statutes that preclude such statements of regret or apology from being used against the physician. Many experts now favor apology statements as a way to reduce the risk of malpractice suits being filed.19

Related Article:

Medical errors: Meeting ethical obligations and reducing liability with proper communication

Defensive medicine. There has been much discussion of “defensive medicine” in recent years.20 It is appropriately criticized when additional testing is solely used to protect the physician from liability. However, much of defensive medicine is not only to protect the physician but also to protect the patient from potential physical and mental harm. In this case, it would have been “careful medicine” in addition to “defensive medicine.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Heikinheimo O, Gemell-Danielsson K. Emerging indications for the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. ACTA Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(1):3–9.

- Mirena [prescribing information]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2000.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: Implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):184–196.

- Rapid EC–Random clinical trial assessing pregnancy with intrauterine devices for emergency contraception. Clinical Trials Identifier: NCT02175030. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02175030?term=NCT02175030&rank=1. Updated May 1, 2017. Accessed May 11, 2017.

- Gnoth C, Johnson S. Strips of hope: Accuracy of home pregnancy tests and new developments. Gerburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2014;74(7):661–669.

- Cole LA, Khanlian SA, Sutton JM, Davies S, Rayburn WF. Accuracy of home pregnancy tests at the time of missed menses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(1):100–105.

- Kim S, Romero R, Kusanovic J, et al. The prognosis of pregnancy conceived despite the presence of an intrauterine device (IUD). J Perinatal Med. 2010;38(1):45–53.

- Brahmi D, Steenland M, Renner R, Gaffield M, Curtis K. Pregnancy outcomes with an IUD in situ: a systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85(2):131–139.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 152: Emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):685–686.

- Chen Q, Xiang W, Zhang D, et al. Efficacy and safety of a levonorgestrel enteric-coated tablet as an over-the-counter drug for emergency contraception: a Phase IV clinical trial. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(9):2316–2321.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 135: Second-trimester abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(6):1395–1406.

- White A, Pichert J, Bledsoe S, Irwin C, Entman S. Cause and effect analysis of closed claims in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 pt1):1031–1038.

- Mehlman M. Professional power and the standard of care in medicine. Case Western Reserve University Scholarly Commons. 2012: Paper 574. http://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1576&context=faculty_publications. Accessed May 11, 2017.

- Klein D, Arnold J, Reese E. Provision of contraception: key recommendations from the CDC. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(9);625–633.

- Reyes J, Reyes R. The effects of malpractice liability on obstetrics and gynecology: taking the measure of a crisis. N England Law Rev. 2012;47;315–348. https://www.scribd.com/document/136514285/Reyes-Reyes-The-Effect-of-Malpractice-Liability-on-Obstetrics-and -Gynecology#fullscreen&from_embed. Accessed May 11, 2017.

- Peckham C. Medscape Malpractice Report 2015: Why Ob/Gyns get sued. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/malpractice-report-2015/obgyn#page=1. Published January 22, 2016. Accessed May 11. 2017.

- Rheingold P, Paris D. Contraceptives. In: Vargo JJ, ed. Products Liability Practice Guide New York, New York: Matthew Bender & Company; 2017;C:62.

- Jena AB, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, Seabury S. Outcomes of medical malpractice litigation against US physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(11):892–894.

- Helmreich JS. Does sorry incriminate? Evidence, harm and the protection of apology. Cornell J Law Public Policy. 2012;21(3);567–609. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1363&context=cjlpp.

- Baicker K, Wright B, Olson N. Reevaluating reports of defensive medicine. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2015;40(6);1157–1177.

CASE: Gynecologist accused of placing an IUD without performing a pregnancy test

A 34-year-old woman (G4 P3013) presents to her gynecologist for planned placement of the Mirena Intrauterine System (Bayer HealthCare). She was divorced 2 months ago and is interested in birth control. She smokes 1.5 packs per day, and her history includes irregular menses, an earlier Pap smear result of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) with negative colposcopy results, polycystic ovary syndrome, obesity, migraine headaches with aura, bilateral carpel tunnel surgery, and a herniated L4.5 disc treated conservatively. She has no history of any psychiatric problems.

One week before intrauterine device (IUD) placement, she discussed the options with her gynecologist and received a Mirena patient brochure. At the office visit for IUD placement, the patient stated she had a negative home pregnancy test 1 week earlier. She did not tell the gynecologist that she had taken Plan B One-Step (levonorgestrel, 1.5 mg) emergency contraception 2 weeks prior to presenting to her gynecologist after receiving it from a Planned Parenthood office following condom breakage during coitus. IUD placement was uncomplicated.

After noting spotting several weeks later, she contacted her gynecologist’s office. Results of an office urine pregnancy test were positive; the serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level was reported at 65,000 mIU/mL.The results of a pelvic sonogram showed a 12 5/7-week intrauterine gestation. The gynecologist unsuccessfully tried to remove the IUD. Options for termination or continuation of the pregnancy were discussed. The patient felt the gynecologist strongly encouraged, “almost insisting on,” termination. Termination could not be performed locally as her state laws did not allow second trimester abortion; the gynecologist provided out-of-state clinic options.

The patient aborted the pregnancy in a neighboring state. She was opposed to the termination but decided it was not a good time for her to have a baby. She felt the staff at the facility were “cold” and had a “we got to get this done attitude.” As she left the clinic, she saw people picketing outside and found the whole process “psychologically traumatic.” When bleeding persisted, she sought care from another gynecologist. Pelvic sonography results showed retained products of conception (POC). The new gynecologist performed operative hysteroscopy to remove the POC. The patient became depressed and felt as if she was a victim of pain and suffering.

The patient’s attorney filed a medical malpractice claim against the gynecologist who inserted the IUD, accusing her of negligence for not performing a pregnancy test immediately before IUD insertion.

In a deposition, the patient stated she bought the home pregnancy test in a “dollar store” and was worried about its accuracy, but never told the gynecologist. Conception probably occurred 2 weeks prior to IUD insertion, correlating with the broken condom and taking of Plan B. She did not think the gynecologist needed to know this as it “would not have made any difference in her care.”

The gynecologist confirmed that the patient’s record included “Patient stated ‘pregnancy test negative within 1 week of IUD placement.’” The gynecologist did not feel that obtaining the date of the patient’s last menstrual period (LMP) was required since she asked if the patient had protected coitus since her LMP and the patient answered yes. The gynecologist thought that if a pregnancy were in utero, Mirena placement would prevent implantation. She believed that she had obtained proper informed consent and that the patient acknowledged receiving and reading the Mirena patient information prior to placement. The gynecologist stated she also provided other birth control options.

The patient’s expert witness testified that the gynecologist fell below the standard of care by not obtaining a pregnancy test prior to IUD insertion.

The gynecologist’s expert witness argued that the patient told the gynecologist that she did not have unprotected coitus. The patient herself withheld information from the gynecologist that she had taken Plan B due to condom breakage. The physician’s attorney also noted that the pelvic exam at time of IUD placement was normal.

What’s the verdict?

The patient has a fairly good case. The gynecologist may not have been sufficiently careful, given all of the facts in this case, to ensure that the patient was not pregnant. An expert is testifying that this fell below the acceptable level of care in the profession. At the same time, the failure of the patient to reveal some information may result in reduced damages through “comparative negligence.” Because there will be several questions of fact for a jury to decide, as well as some emotional elements in this case, the outcome of a trial is uncertain. This suggests that a negotiated settlement before trial should be considered.

Read about medical considerations of a pregnancy with an IUD.

Medical considerations

First, some background information on Mirena.

Indications for Mirena

Here are indications for Mirena1:

- intrauterine contraception for up to 5 years

- treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding for women who choose to use intrauterine contraception as their method of contraception.

Prior to insertion, the following are recommended2:

- a complete medical and social history should be obtained to determine conditions that might influence the selection of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG IUS) for contraception

- if indicated, perform a physical examination, and appropriate tests for any forms of genital or other sexually transmitted infections

- there is no requirement for prepregnancy test.

Contraindications for Mirena

Contraindications for Mirena include2:

- pregnancy or suspicion of pregnancy; cannot be used for postcoital contraception

- congenital or acquired uterine anomaly including fibroids if they distort the uterine cavity

- acute pelvic inflammatory disease or a history of pelvic inflammatory disease unless there has been a subsequent intrauterine pregnancy

- postpartum endometritis or infected abortion in the past 3 months

- known or suspected uterine or cervical neoplasia

- known or suspected breast cancer or other progestin-sensitive cancer, now or in the past

- uterine bleeding of unknown etiology

- untreated acute cervicitis or vaginitis, including bacterial vaginosis or other lower genital tract infections until infection is controlled

- acute liver disease or liver tumor (benign or malignant)

- conditions associated with increased susceptibility to pelvic infections

- a previously inserted IUD that has not been removed

- hypersensitivity to any component of this product.

Is Mirena a postcoital contraceptive?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) bulletin on long-acting reversible contraception states “the levonorgestrel intrauterine system has not been studied for emergency contraception.”3 Ongoing studies are comparing the levonor‑gestrel IUD to the copper IUD for emergency contraception.4

Related Article:

Webcast: Emergency contraception: How to choose the right one for your patient

Accuracy of home pregnancy tests

Although the first home pregnancy test was introduced in 1976,5 there are now several home pregnancy tests available over the counter, most designed to detect urinary levels of hCG at ≥25 mIU/mL. The tests identify hCG, hyperglycosylated hCG, and free Betasubunit hCG in urine. When Cole and colleagues evaluated the validity of urinary tests including assessment of 18 brands, results noted that sensitivity of 12.4 mIU/mL of hCG detected 95% of pregnancies at time of missed menses.6 Some brands required 100 mIU/mL levels of hCG for positive results. The authors concluded “the utility of home pregnancy tests is questioned.”6 For urinary levels of hCG, see TABLE.

Pregnancy with an IUD

The gynecologist’s concern about pregnancy when an IUD is inserted was valid.

With regard to pregnancy with Mirena in place, the full prescribing information states2:

Intrauterine Pregnancy: If pregnancy occurs while using Mirena, remove Mirena because leaving it in place may increase the risk of spontaneous abortion and preterm labor. Removal of Mirena or probing of the uterus may also result in spontaneous abortion. In the event of an intrauterine pregnancy with Mirena, consider the following:

Septic abortion

In patients becoming pregnant with an IUD in place, septic abortion - with septicemia, septic shock, and death may occur.

Continuation of pregnancy

If a woman becomes pregnant with Mirena in place and if Mirena cannot be removed or the woman chooses not to have it removed, warn her that failure to remove Mirena increases the risk of miscarriage, sepsis, premature labor and premature delivery. Follow her pregnancy closely and advise her to report immediately any symptom that suggests complications of the pregnancy.

Concern for microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity must be considered. Kim and colleagues addressed pregnancy prognosis with an IUD in situ in a retrospective study of 12,297 pregnancies; 196 had an IUD with singleton gestation.7 The study revealed a higher incidence of histologic chorioamnionitis and/or funisitis when compared with those without an IUD (54.2% vs 14.7%, respectively; P<.001). The authors concluded that pregnant women with an IUD in utero are at very high risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Brahmi and colleagues8 reported similar risks with higher incidence of spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, and septic abortion.

Related Article:

Overcoming LARC complications: 7 case challenges

Efficacy and safety concerns with emergency contraception

The efficacy and safety of emergency contraception using levonorgestrel oral tablets (Plan B One-Step; Duramed Pharmaceuticals) is another concern. Plan B One-Step should be taken orally as soon as possible within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse or a known or suspected contraceptive failure. Efficacy is better if Plan B is taken as soon as possible after unprotected intercourse. There are 2 dosages: 1 tablet of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg or 2 tablets of levonorgestrel 0.75 mg. The second 0.75-mg tablet should be taken 12 hours after the first dose.9

Plan B can be used at any time during the menstrual cycle. In a series of 2,445 women aged 15 to 48 years who took levonorgestrel tablets for emergency contraception (Phase IV clinical trial), 5 pregnancies occurred (0.2%).10

ACOG advises that emergency contraception using a pill or the copper IUD should be initiated as soon as possible (up to 5 days) after unprotected coitus or inadequately protected coitus.9

Retained products of contraception

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 135 on complications associated with second trimesterabortion discusses retained POC.11 The approach to second trimester abortion includes dilation and evacuation (D&E) as well as medical therapy with mifepristone and misoprostol. D&E, a safe and effective approach with advantages over medical abortion, is associated with fewer complications (up to 4%) versus medical abortion (29%); the primary complication is retained POC (placenta).11

Read about the legal considerations of this case.

Legal considerations

The malpractice lawsuit filed in this case claims that the gynecologist failed to exercise the level of care of a reasonably prudent practitioner under the circumstances and was therefore negligent or in breach of a duty to the patient.

First, a lawyer would look for a medical error that was related to some harm. Keep in mind that not all medical errors are negligent or subject to liability. Many medical errors occur even though the physician has exercised all reasonable care and engaged in sound practice, given today’s medical knowledge and facilities. When harm is caused through medical error that was careless or otherwise does not meet the standard of care, financial recovery is possible for the patient through a malpractice claim.12

In this case, the expert witnesses’ statements focus on the issue of conducting a pregnancy test prior to IUD insertion. The patient’s expert testified that failure to perform a pregnancy test was below an acceptable standard of care. That opinion may have been based on the typical practice of gynecologists, widely accepted medical text books, and formal practice standards of professional organizations.13

Cost-benefit analysis. Additional support for the claim that not performing the pregnancy test is negligent comes from applying a cost-benefit analysis. In this analysis, the risks and costs of performing a pregnancy test are compared with the benefits of doing the test.

In this case, the cost of conducting the pregnancy test is very low: essentially risk-freeand relatively inexpensive. On the other hand, the harm that could be avoided would be significant. Kim and colleagues suggest that pregnant women with an IUD in utero are at very high risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes.7 Given that women receiving IUDs are candidates for pregnancy (and perhaps do not know they are pregnant), a simple, risk-free pregnancy test would seem to be an efficient way to avoid a nontrivial harm.14

Did she have unprotected sex? The gynecologist’s expert notes that the patient told the gynecologist that she did not have unprotected coitus. Furthermore, the patient withheld from the gynecologist the information that she had taken Plan B because of a broken condom. Is this a defense against the malpractice claim? The answer is “possibly no,” or “possibly somewhat.”

As for unprotected coitus, the patient could easily have misunderstood the question. Technically, the answer “no” was correct. She had not had unprotected sex—it is just that the protection (condom) failed. It does not appear from the facts that she disclosed or was asked about Plan B or other information related to possible failed contraception. As to whether the patient’s failure to provide that information could be a defense for the physician, the best answer is “possibly” and “somewhat.” (See below.)15

Withholding information. Patients, of course, have a responsibility to inform their physicians of information they know is relevant. Many patients, however, will not know what is relevant (or why), or will not be fully disclosing.

Professionals cannot ignore the fact that their patients and clients are often confused, do not understand what is important and relevant, and cannot always be relied upon. For that very reason, professionals generally are obliged to start with the proposition that they may not have all of the relevant information. In this case, this lack of information makes the cost-calculation of performing a pregnancy test that much more important. The risk of not knowing whether a patient is pregnant includes the fact that many patients just will not know or cannot say with assurance.16

A “somewhat” defense and comparative negligence

Earlier we referred to a “somewhat” defense. Almost all states now have some form of “comparative negligence,” meaning that the patient’s recovery is reduced by the proportion of the blame (negligence) that is attributed to the patient. The most common form of comparative negligence works this way: If there are damages of $100,000, and the jury finds that the fault is 20% the patient’s and 80% the physician’s, the patient would receive $80,000 recovery. (In the past, the concept of “contributory negligence” could result in the plaintiff being precluded from any recovery if the plaintiff was partially negligent—those days are mostly gone.)

Related Article:

Informed consent: The more you know, the more you and your patient are protected

Statement of risks, informed consent, and liability

The gynecologist must provide an adequate description of the IUD risks. The case facts indicate that appropriate risks were discussed and literature provided, so it appears there was probably appropriate informed consent in this case. If not true, this would provide another basis for recovery.

Two other aspects of this case could be the basis for liability. We can assume that the attempted removal of the IUD was performed competently.16 In addition, if the IUD was defective in terms of design, manufacture, or warnings, the manufacturer of the device could be subject to liability.17

Final verdict: Out of court settlement

Why would the gynecologist and the insurance company settle this case? After all, they have some arguments on their side, and physicians win the majority of malpractice cases that go to trial.18 On the other hand, the patient’s expert witness’ testimony and the cost-benefit analysis of the pregnancy test are strong, contrary claims.

Cases are settled for a variety of reasons. Litigation is inherently risky. In this case, we assume that the court denied a motion to dismiss the case before trial because there is a legitimate question of fact concerning what a reasonably prudent gynecologist would have done under the circumstances. That means a jury would probably decide the issue of medical judgment, which is generally disconcerting. Furthermore, the comparative negligence defense that the patient did not tell the gynecologist about the failed condom/Plan B would most likely reduce the amount of damages, but not eliminate liability. The questions regarding the pressure to terminate a second trimester pregnancy might well complicate a jury’s view.

Other considerations include the high costs in time, money, uncertainty, and disruption associated with litigation. The settlement amount was not stated, but the process of negotiating a settlement would allow factoring in the comparative negligence aspect of the case. It would be reasonable for this case to settle before trial.

Should the physician have apologized before trial? The gynecologist could have sent a statement of regret or apology to the patient before a lawsuit was filed. Most states now have statutes that preclude such statements of regret or apology from being used against the physician. Many experts now favor apology statements as a way to reduce the risk of malpractice suits being filed.19

Related Article:

Medical errors: Meeting ethical obligations and reducing liability with proper communication

Defensive medicine. There has been much discussion of “defensive medicine” in recent years.20 It is appropriately criticized when additional testing is solely used to protect the physician from liability. However, much of defensive medicine is not only to protect the physician but also to protect the patient from potential physical and mental harm. In this case, it would have been “careful medicine” in addition to “defensive medicine.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE: Gynecologist accused of placing an IUD without performing a pregnancy test

A 34-year-old woman (G4 P3013) presents to her gynecologist for planned placement of the Mirena Intrauterine System (Bayer HealthCare). She was divorced 2 months ago and is interested in birth control. She smokes 1.5 packs per day, and her history includes irregular menses, an earlier Pap smear result of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) with negative colposcopy results, polycystic ovary syndrome, obesity, migraine headaches with aura, bilateral carpel tunnel surgery, and a herniated L4.5 disc treated conservatively. She has no history of any psychiatric problems.

One week before intrauterine device (IUD) placement, she discussed the options with her gynecologist and received a Mirena patient brochure. At the office visit for IUD placement, the patient stated she had a negative home pregnancy test 1 week earlier. She did not tell the gynecologist that she had taken Plan B One-Step (levonorgestrel, 1.5 mg) emergency contraception 2 weeks prior to presenting to her gynecologist after receiving it from a Planned Parenthood office following condom breakage during coitus. IUD placement was uncomplicated.

After noting spotting several weeks later, she contacted her gynecologist’s office. Results of an office urine pregnancy test were positive; the serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level was reported at 65,000 mIU/mL.The results of a pelvic sonogram showed a 12 5/7-week intrauterine gestation. The gynecologist unsuccessfully tried to remove the IUD. Options for termination or continuation of the pregnancy were discussed. The patient felt the gynecologist strongly encouraged, “almost insisting on,” termination. Termination could not be performed locally as her state laws did not allow second trimester abortion; the gynecologist provided out-of-state clinic options.

The patient aborted the pregnancy in a neighboring state. She was opposed to the termination but decided it was not a good time for her to have a baby. She felt the staff at the facility were “cold” and had a “we got to get this done attitude.” As she left the clinic, she saw people picketing outside and found the whole process “psychologically traumatic.” When bleeding persisted, she sought care from another gynecologist. Pelvic sonography results showed retained products of conception (POC). The new gynecologist performed operative hysteroscopy to remove the POC. The patient became depressed and felt as if she was a victim of pain and suffering.

The patient’s attorney filed a medical malpractice claim against the gynecologist who inserted the IUD, accusing her of negligence for not performing a pregnancy test immediately before IUD insertion.

In a deposition, the patient stated she bought the home pregnancy test in a “dollar store” and was worried about its accuracy, but never told the gynecologist. Conception probably occurred 2 weeks prior to IUD insertion, correlating with the broken condom and taking of Plan B. She did not think the gynecologist needed to know this as it “would not have made any difference in her care.”

The gynecologist confirmed that the patient’s record included “Patient stated ‘pregnancy test negative within 1 week of IUD placement.’” The gynecologist did not feel that obtaining the date of the patient’s last menstrual period (LMP) was required since she asked if the patient had protected coitus since her LMP and the patient answered yes. The gynecologist thought that if a pregnancy were in utero, Mirena placement would prevent implantation. She believed that she had obtained proper informed consent and that the patient acknowledged receiving and reading the Mirena patient information prior to placement. The gynecologist stated she also provided other birth control options.

The patient’s expert witness testified that the gynecologist fell below the standard of care by not obtaining a pregnancy test prior to IUD insertion.

The gynecologist’s expert witness argued that the patient told the gynecologist that she did not have unprotected coitus. The patient herself withheld information from the gynecologist that she had taken Plan B due to condom breakage. The physician’s attorney also noted that the pelvic exam at time of IUD placement was normal.

What’s the verdict?

The patient has a fairly good case. The gynecologist may not have been sufficiently careful, given all of the facts in this case, to ensure that the patient was not pregnant. An expert is testifying that this fell below the acceptable level of care in the profession. At the same time, the failure of the patient to reveal some information may result in reduced damages through “comparative negligence.” Because there will be several questions of fact for a jury to decide, as well as some emotional elements in this case, the outcome of a trial is uncertain. This suggests that a negotiated settlement before trial should be considered.

Read about medical considerations of a pregnancy with an IUD.

Medical considerations

First, some background information on Mirena.

Indications for Mirena

Here are indications for Mirena1:

- intrauterine contraception for up to 5 years

- treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding for women who choose to use intrauterine contraception as their method of contraception.

Prior to insertion, the following are recommended2:

- a complete medical and social history should be obtained to determine conditions that might influence the selection of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG IUS) for contraception

- if indicated, perform a physical examination, and appropriate tests for any forms of genital or other sexually transmitted infections

- there is no requirement for prepregnancy test.

Contraindications for Mirena

Contraindications for Mirena include2:

- pregnancy or suspicion of pregnancy; cannot be used for postcoital contraception

- congenital or acquired uterine anomaly including fibroids if they distort the uterine cavity

- acute pelvic inflammatory disease or a history of pelvic inflammatory disease unless there has been a subsequent intrauterine pregnancy

- postpartum endometritis or infected abortion in the past 3 months

- known or suspected uterine or cervical neoplasia

- known or suspected breast cancer or other progestin-sensitive cancer, now or in the past

- uterine bleeding of unknown etiology

- untreated acute cervicitis or vaginitis, including bacterial vaginosis or other lower genital tract infections until infection is controlled

- acute liver disease or liver tumor (benign or malignant)

- conditions associated with increased susceptibility to pelvic infections

- a previously inserted IUD that has not been removed

- hypersensitivity to any component of this product.

Is Mirena a postcoital contraceptive?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) bulletin on long-acting reversible contraception states “the levonorgestrel intrauterine system has not been studied for emergency contraception.”3 Ongoing studies are comparing the levonor‑gestrel IUD to the copper IUD for emergency contraception.4

Related Article:

Webcast: Emergency contraception: How to choose the right one for your patient

Accuracy of home pregnancy tests

Although the first home pregnancy test was introduced in 1976,5 there are now several home pregnancy tests available over the counter, most designed to detect urinary levels of hCG at ≥25 mIU/mL. The tests identify hCG, hyperglycosylated hCG, and free Betasubunit hCG in urine. When Cole and colleagues evaluated the validity of urinary tests including assessment of 18 brands, results noted that sensitivity of 12.4 mIU/mL of hCG detected 95% of pregnancies at time of missed menses.6 Some brands required 100 mIU/mL levels of hCG for positive results. The authors concluded “the utility of home pregnancy tests is questioned.”6 For urinary levels of hCG, see TABLE.

Pregnancy with an IUD

The gynecologist’s concern about pregnancy when an IUD is inserted was valid.

With regard to pregnancy with Mirena in place, the full prescribing information states2:

Intrauterine Pregnancy: If pregnancy occurs while using Mirena, remove Mirena because leaving it in place may increase the risk of spontaneous abortion and preterm labor. Removal of Mirena or probing of the uterus may also result in spontaneous abortion. In the event of an intrauterine pregnancy with Mirena, consider the following:

Septic abortion

In patients becoming pregnant with an IUD in place, septic abortion - with septicemia, septic shock, and death may occur.

Continuation of pregnancy

If a woman becomes pregnant with Mirena in place and if Mirena cannot be removed or the woman chooses not to have it removed, warn her that failure to remove Mirena increases the risk of miscarriage, sepsis, premature labor and premature delivery. Follow her pregnancy closely and advise her to report immediately any symptom that suggests complications of the pregnancy.

Concern for microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity must be considered. Kim and colleagues addressed pregnancy prognosis with an IUD in situ in a retrospective study of 12,297 pregnancies; 196 had an IUD with singleton gestation.7 The study revealed a higher incidence of histologic chorioamnionitis and/or funisitis when compared with those without an IUD (54.2% vs 14.7%, respectively; P<.001). The authors concluded that pregnant women with an IUD in utero are at very high risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Brahmi and colleagues8 reported similar risks with higher incidence of spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, and septic abortion.

Related Article:

Overcoming LARC complications: 7 case challenges

Efficacy and safety concerns with emergency contraception

The efficacy and safety of emergency contraception using levonorgestrel oral tablets (Plan B One-Step; Duramed Pharmaceuticals) is another concern. Plan B One-Step should be taken orally as soon as possible within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse or a known or suspected contraceptive failure. Efficacy is better if Plan B is taken as soon as possible after unprotected intercourse. There are 2 dosages: 1 tablet of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg or 2 tablets of levonorgestrel 0.75 mg. The second 0.75-mg tablet should be taken 12 hours after the first dose.9

Plan B can be used at any time during the menstrual cycle. In a series of 2,445 women aged 15 to 48 years who took levonorgestrel tablets for emergency contraception (Phase IV clinical trial), 5 pregnancies occurred (0.2%).10

ACOG advises that emergency contraception using a pill or the copper IUD should be initiated as soon as possible (up to 5 days) after unprotected coitus or inadequately protected coitus.9

Retained products of contraception

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 135 on complications associated with second trimesterabortion discusses retained POC.11 The approach to second trimester abortion includes dilation and evacuation (D&E) as well as medical therapy with mifepristone and misoprostol. D&E, a safe and effective approach with advantages over medical abortion, is associated with fewer complications (up to 4%) versus medical abortion (29%); the primary complication is retained POC (placenta).11

Read about the legal considerations of this case.

Legal considerations

The malpractice lawsuit filed in this case claims that the gynecologist failed to exercise the level of care of a reasonably prudent practitioner under the circumstances and was therefore negligent or in breach of a duty to the patient.

First, a lawyer would look for a medical error that was related to some harm. Keep in mind that not all medical errors are negligent or subject to liability. Many medical errors occur even though the physician has exercised all reasonable care and engaged in sound practice, given today’s medical knowledge and facilities. When harm is caused through medical error that was careless or otherwise does not meet the standard of care, financial recovery is possible for the patient through a malpractice claim.12

In this case, the expert witnesses’ statements focus on the issue of conducting a pregnancy test prior to IUD insertion. The patient’s expert testified that failure to perform a pregnancy test was below an acceptable standard of care. That opinion may have been based on the typical practice of gynecologists, widely accepted medical text books, and formal practice standards of professional organizations.13

Cost-benefit analysis. Additional support for the claim that not performing the pregnancy test is negligent comes from applying a cost-benefit analysis. In this analysis, the risks and costs of performing a pregnancy test are compared with the benefits of doing the test.

In this case, the cost of conducting the pregnancy test is very low: essentially risk-freeand relatively inexpensive. On the other hand, the harm that could be avoided would be significant. Kim and colleagues suggest that pregnant women with an IUD in utero are at very high risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes.7 Given that women receiving IUDs are candidates for pregnancy (and perhaps do not know they are pregnant), a simple, risk-free pregnancy test would seem to be an efficient way to avoid a nontrivial harm.14

Did she have unprotected sex? The gynecologist’s expert notes that the patient told the gynecologist that she did not have unprotected coitus. Furthermore, the patient withheld from the gynecologist the information that she had taken Plan B because of a broken condom. Is this a defense against the malpractice claim? The answer is “possibly no,” or “possibly somewhat.”

As for unprotected coitus, the patient could easily have misunderstood the question. Technically, the answer “no” was correct. She had not had unprotected sex—it is just that the protection (condom) failed. It does not appear from the facts that she disclosed or was asked about Plan B or other information related to possible failed contraception. As to whether the patient’s failure to provide that information could be a defense for the physician, the best answer is “possibly” and “somewhat.” (See below.)15

Withholding information. Patients, of course, have a responsibility to inform their physicians of information they know is relevant. Many patients, however, will not know what is relevant (or why), or will not be fully disclosing.

Professionals cannot ignore the fact that their patients and clients are often confused, do not understand what is important and relevant, and cannot always be relied upon. For that very reason, professionals generally are obliged to start with the proposition that they may not have all of the relevant information. In this case, this lack of information makes the cost-calculation of performing a pregnancy test that much more important. The risk of not knowing whether a patient is pregnant includes the fact that many patients just will not know or cannot say with assurance.16

A “somewhat” defense and comparative negligence

Earlier we referred to a “somewhat” defense. Almost all states now have some form of “comparative negligence,” meaning that the patient’s recovery is reduced by the proportion of the blame (negligence) that is attributed to the patient. The most common form of comparative negligence works this way: If there are damages of $100,000, and the jury finds that the fault is 20% the patient’s and 80% the physician’s, the patient would receive $80,000 recovery. (In the past, the concept of “contributory negligence” could result in the plaintiff being precluded from any recovery if the plaintiff was partially negligent—those days are mostly gone.)

Related Article:

Informed consent: The more you know, the more you and your patient are protected

Statement of risks, informed consent, and liability

The gynecologist must provide an adequate description of the IUD risks. The case facts indicate that appropriate risks were discussed and literature provided, so it appears there was probably appropriate informed consent in this case. If not true, this would provide another basis for recovery.

Two other aspects of this case could be the basis for liability. We can assume that the attempted removal of the IUD was performed competently.16 In addition, if the IUD was defective in terms of design, manufacture, or warnings, the manufacturer of the device could be subject to liability.17

Final verdict: Out of court settlement

Why would the gynecologist and the insurance company settle this case? After all, they have some arguments on their side, and physicians win the majority of malpractice cases that go to trial.18 On the other hand, the patient’s expert witness’ testimony and the cost-benefit analysis of the pregnancy test are strong, contrary claims.

Cases are settled for a variety of reasons. Litigation is inherently risky. In this case, we assume that the court denied a motion to dismiss the case before trial because there is a legitimate question of fact concerning what a reasonably prudent gynecologist would have done under the circumstances. That means a jury would probably decide the issue of medical judgment, which is generally disconcerting. Furthermore, the comparative negligence defense that the patient did not tell the gynecologist about the failed condom/Plan B would most likely reduce the amount of damages, but not eliminate liability. The questions regarding the pressure to terminate a second trimester pregnancy might well complicate a jury’s view.

Other considerations include the high costs in time, money, uncertainty, and disruption associated with litigation. The settlement amount was not stated, but the process of negotiating a settlement would allow factoring in the comparative negligence aspect of the case. It would be reasonable for this case to settle before trial.

Should the physician have apologized before trial? The gynecologist could have sent a statement of regret or apology to the patient before a lawsuit was filed. Most states now have statutes that preclude such statements of regret or apology from being used against the physician. Many experts now favor apology statements as a way to reduce the risk of malpractice suits being filed.19

Related Article:

Medical errors: Meeting ethical obligations and reducing liability with proper communication

Defensive medicine. There has been much discussion of “defensive medicine” in recent years.20 It is appropriately criticized when additional testing is solely used to protect the physician from liability. However, much of defensive medicine is not only to protect the physician but also to protect the patient from potential physical and mental harm. In this case, it would have been “careful medicine” in addition to “defensive medicine.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Heikinheimo O, Gemell-Danielsson K. Emerging indications for the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. ACTA Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(1):3–9.

- Mirena [prescribing information]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2000.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: Implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):184–196.

- Rapid EC–Random clinical trial assessing pregnancy with intrauterine devices for emergency contraception. Clinical Trials Identifier: NCT02175030. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02175030?term=NCT02175030&rank=1. Updated May 1, 2017. Accessed May 11, 2017.

- Gnoth C, Johnson S. Strips of hope: Accuracy of home pregnancy tests and new developments. Gerburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2014;74(7):661–669.

- Cole LA, Khanlian SA, Sutton JM, Davies S, Rayburn WF. Accuracy of home pregnancy tests at the time of missed menses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(1):100–105.

- Kim S, Romero R, Kusanovic J, et al. The prognosis of pregnancy conceived despite the presence of an intrauterine device (IUD). J Perinatal Med. 2010;38(1):45–53.

- Brahmi D, Steenland M, Renner R, Gaffield M, Curtis K. Pregnancy outcomes with an IUD in situ: a systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85(2):131–139.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 152: Emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):685–686.

- Chen Q, Xiang W, Zhang D, et al. Efficacy and safety of a levonorgestrel enteric-coated tablet as an over-the-counter drug for emergency contraception: a Phase IV clinical trial. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(9):2316–2321.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 135: Second-trimester abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(6):1395–1406.

- White A, Pichert J, Bledsoe S, Irwin C, Entman S. Cause and effect analysis of closed claims in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 pt1):1031–1038.

- Mehlman M. Professional power and the standard of care in medicine. Case Western Reserve University Scholarly Commons. 2012: Paper 574. http://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1576&context=faculty_publications. Accessed May 11, 2017.

- Klein D, Arnold J, Reese E. Provision of contraception: key recommendations from the CDC. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(9);625–633.

- Reyes J, Reyes R. The effects of malpractice liability on obstetrics and gynecology: taking the measure of a crisis. N England Law Rev. 2012;47;315–348. https://www.scribd.com/document/136514285/Reyes-Reyes-The-Effect-of-Malpractice-Liability-on-Obstetrics-and -Gynecology#fullscreen&from_embed. Accessed May 11, 2017.

- Peckham C. Medscape Malpractice Report 2015: Why Ob/Gyns get sued. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/malpractice-report-2015/obgyn#page=1. Published January 22, 2016. Accessed May 11. 2017.

- Rheingold P, Paris D. Contraceptives. In: Vargo JJ, ed. Products Liability Practice Guide New York, New York: Matthew Bender & Company; 2017;C:62.

- Jena AB, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, Seabury S. Outcomes of medical malpractice litigation against US physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(11):892–894.

- Helmreich JS. Does sorry incriminate? Evidence, harm and the protection of apology. Cornell J Law Public Policy. 2012;21(3);567–609. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1363&context=cjlpp.

- Baicker K, Wright B, Olson N. Reevaluating reports of defensive medicine. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2015;40(6);1157–1177.

- Heikinheimo O, Gemell-Danielsson K. Emerging indications for the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. ACTA Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(1):3–9.

- Mirena [prescribing information]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2000.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: Implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):184–196.

- Rapid EC–Random clinical trial assessing pregnancy with intrauterine devices for emergency contraception. Clinical Trials Identifier: NCT02175030. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02175030?term=NCT02175030&rank=1. Updated May 1, 2017. Accessed May 11, 2017.

- Gnoth C, Johnson S. Strips of hope: Accuracy of home pregnancy tests and new developments. Gerburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2014;74(7):661–669.

- Cole LA, Khanlian SA, Sutton JM, Davies S, Rayburn WF. Accuracy of home pregnancy tests at the time of missed menses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(1):100–105.

- Kim S, Romero R, Kusanovic J, et al. The prognosis of pregnancy conceived despite the presence of an intrauterine device (IUD). J Perinatal Med. 2010;38(1):45–53.

- Brahmi D, Steenland M, Renner R, Gaffield M, Curtis K. Pregnancy outcomes with an IUD in situ: a systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85(2):131–139.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 152: Emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):685–686.

- Chen Q, Xiang W, Zhang D, et al. Efficacy and safety of a levonorgestrel enteric-coated tablet as an over-the-counter drug for emergency contraception: a Phase IV clinical trial. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(9):2316–2321.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 135: Second-trimester abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(6):1395–1406.

- White A, Pichert J, Bledsoe S, Irwin C, Entman S. Cause and effect analysis of closed claims in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 pt1):1031–1038.

- Mehlman M. Professional power and the standard of care in medicine. Case Western Reserve University Scholarly Commons. 2012: Paper 574. http://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1576&context=faculty_publications. Accessed May 11, 2017.

- Klein D, Arnold J, Reese E. Provision of contraception: key recommendations from the CDC. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(9);625–633.

- Reyes J, Reyes R. The effects of malpractice liability on obstetrics and gynecology: taking the measure of a crisis. N England Law Rev. 2012;47;315–348. https://www.scribd.com/document/136514285/Reyes-Reyes-The-Effect-of-Malpractice-Liability-on-Obstetrics-and -Gynecology#fullscreen&from_embed. Accessed May 11, 2017.

- Peckham C. Medscape Malpractice Report 2015: Why Ob/Gyns get sued. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/malpractice-report-2015/obgyn#page=1. Published January 22, 2016. Accessed May 11. 2017.

- Rheingold P, Paris D. Contraceptives. In: Vargo JJ, ed. Products Liability Practice Guide New York, New York: Matthew Bender & Company; 2017;C:62.

- Jena AB, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, Seabury S. Outcomes of medical malpractice litigation against US physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(11):892–894.

- Helmreich JS. Does sorry incriminate? Evidence, harm and the protection of apology. Cornell J Law Public Policy. 2012;21(3);567–609. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1363&context=cjlpp.

- Baicker K, Wright B, Olson N. Reevaluating reports of defensive medicine. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2015;40(6);1157–1177.