User login

Wayne Fenton, MD, an associate director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), was murdered September 3—allegedly by a patient—in his Bethesda, MD, office. The case has led other mental health professionals to wonder how susceptible they are to assault and whether they are doing all they can to protect themselves.

To explore these safety issues, Current Psychiatry Deputy Editor Lois E. Krahn, MD, talked with John Battaglia, MD, medical director of the Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) in Madison, WI.

Dr. Battaglia’s work takes him into the community to treat patients with severe chronic mental illnesses. The Madison PACT program uses an intensive, team-based approach for patients who have been inadequately treated in usual mental health services. Patients with complicated psychiatric, social, and legal problems are seen in their homes, at work, or on the streets in an assertive and comprehensive style of case management.

Dr. Krahn: Dr. Fenton’s death was a tremendous loss to the psychiatric community.

Dr. Battaglia: We were all shaken; my first reaction was horror and sadness.

Dr. Krahn: Dr. Fenton was a very experienced psychiatrist (Box 1). His murder makes us think about our own vulnerability and wonder if such an assault could happen to us.

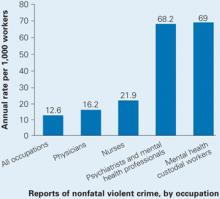

Dr. Battaglia: Yes, it’s very common for psychiatrists or mental health providers to be assaulted (Box 2).

Dr. Fenton devoted his life to schizophrenia, through his compassion for those afflicted and his research that aided untold numbers of the mentally ill and their caregivers.

So it was especially sad that Dr. Fenton died while reaching out to a patient in need. On September 3, the NIMH associate director answered an urgent call to help a distressed, psychotic young man. A short time later, Dr. Fenton was found beaten to death at his Bethesda, MD, office.

Dr. Fenton was just 53 when he died, but his accomplishments were great. He joined NIMH in 1999, helping the organization find new treatments to enable schizophrenia patients to function in society. In this role, he galvanized colleagues nationwide to tackle the complex issue of difficult-to-treat schizophrenia. Before joining NIMH, Dr. Fenton was director and CEO of the Chestnut Lodge Hospital in Rockville, MD, where he did pivotal long-term studies of therapies for schizophrenia. From 2000 to 2005, he was deputy editor-in-chief of the journal Schizophrenia Bulletin. He served on numerous boards and in advocacy roles and won numerous awards.

In addition to these responsibilities, Dr. Fenton made time for his patients. And he gave his life, as he had lived it, trying to help. His obituary in the Washington Post included this quotation from Dr. Fenton, whom the newspaper interviewed in 2002:

All one has to do is walk through a downtown area to appreciate that the availability of adequate treatment for patients with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses is a serious problem for the country. We wouldn’t let our 80-year-old mother with Alzheimer’s live on a grate. Why is it all right for a 30-year-old daughter with schizophrenia?

In one study, more than 50% of psychiatrists and 75% of mental health nurses reported experiencing an act or threat of violence within the past year.1

Dr. Krahn: Have you been assaulted by a patient?

Dr. Battaglia: Yes I have, and I think we need to define assault. A 15-year analysis of assaults on staff in a Massachusetts mental health system divided the acts into four types: physical, sexual, nonverbal threats/intimidation, and verbal assault.2 And you might think physical assault would be worse than verbal assaults. But a threat from a patient—especially one aimed toward your family—can leave you feeling vulnerable, stressed, and hypervigilant. Every sound at night makes you wonder if that person is coming after your family.

Dr. Krahn: What kinds of patients are associated with violence and assault?

Dr. Battaglia: The DSM-IV-TR diagnosis that comes up most often is schizophrenia, but it’s debatable whether diagnosis alone increases the risk of violence.

A study in Sweden published this year found a definite correlation between severe mental illness and violent crime. The authors concluded that about 5% of violent crimes in that country were committed by persons with severe mental illness.3

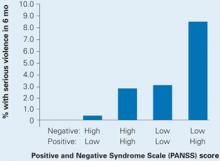

Also this year, a study of data from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) found an increased risk of violence in schizophrenia patients with positive psychotic symptoms but a decreased risk in those with predominantly negative symptoms such as social withdrawal. Those with a combination of above-median positive and below-median negative symptoms were at highest risk for serious violence (Box 3).

Among a sample of 1,410 chronic schizophrenia patients enrolled in the NIMH-sponsored CATIE, 19% were involved in either minor or serious violent behavior in the past 6 months and 3.6% in serious violent behavior.4

Nobody argues that someone with schizophrenia is clearly at higher risk of becoming violent when in a high arousal state with positive symptoms or unpleasant delusions or hallucinations. A person with schizophrenia who is in an agitated, aroused psychotic state with active paranoid delusions and hallucinations is clearly at higher risk for committing violence.5,6 The patient who has been charged in the beating death of Dr. Fenton was a 19-year-old man with severe psychosis.

Dr. Krahn: Are there other disorders, such as bipolar mania, that are high risk for patient violence?

Dr. Battaglia: Acute manic states are higher risk.7 But, again, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in and of itself does not show an increased incidence of violence. Personality disorders can be higher risk, as can nonspecific neurologic abnormalities, such as abnormal EEGs or neurologic “soft signs” by exam or testing.

Dr. Krahn: What about substance abuse?

Dr. Battaglia: The risk of violence is higher in patients who are under the influence of certain stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamines, as opposed to marijuana or sedatives.8

Dr. Krahn: How can we predict whether a patient is at high risk for assault?

Dr. Battaglia: The best predictor is a history of violence, especially when the act was unprovoked or resulted in injury.9 A small number of patients is responsible for the majority of aggression. One study showed that recidivists committed 53% of all violent acts in a health care setting.10

Dr. Krahn: What if the patient’s history is unknown?

Dr. Battaglia: Most assaults in health care occur in high arousal states. Planned, methodical assaults are significantly less frequent. So, in the case of patients making threats against staff—let’s say you terminated your relationship with a patient and obtained a restraining order—very commonly that patient’s passion toward the clinic will wane over time.

Dr. Krahn: But not every arousal state results in assault.

Dr. Battaglia: Right. I have a colleague who says, “Risk factors make you worry more, and nothing makes you worry less.” That’s the attitude to have. Nothing should make you lower your antenna.

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, National Crime Victimization Survey, 1993 to 1999

Dr. Krahn: Is the risk higher with a new patient, or does it go down as you establish a relationship?

Dr. Battaglia: Clearly, untreated patients in high arousal states are a much greater risk. Does risk go down with somebody you’ve known for a while? I don’t know. My own experiences with assault have sometimes occurred with people I’ve grown to trust and when I let my guard down.

Dr. Krahn: So we might relax once we know the patient, but then we might be more vulnerable. Any clues that should put us on high alert?

Dr. Battaglia: The first clue—and this is going to sound obvious—is our internal, visceral, emotional sense of impending danger. In my experience, psychiatrists have a very good sense of that, but we override or don’t pay attention to it. Part of that inattention is an occupational hazard; we have to turn off our sense of danger again and again so that we can stay in situations that would repulse most people.

For instance, medical students with no psychiatric experience might sit in an interview with an agitated patient and feel an intense need to flee. Their antennae are telling them the situation looks dangerous. Seasoned psychiatrists, however, will calm themselves and stay through the interview. We are so used to being healers and helpers that we often turn off or dampen our sense of danger.

Dr. Krahn: Can you elaborate?

Dr. Battaglia: A nurse and I were with a patient who was highly agitated. He was labile; he was angry; he was spitting as he was speaking. In any other context, people would be keeping their distance because the signals were so powerful. Instead, the nurse leaned in, held his hand, and started telling him, “Come on now (Bob), you need to settle down. This is scaring us.”

That’s what I call the “leaning-in response.” We do that day in and day out. We turn off our danger signals in order to be therapeutic, and that makes us vulnerable.

Dr. Krahn: So, how do we keep our signals tuned?

Dr. Battaglia: When our senses are telling us we’re scared or we’re noticing a feeling of wanting to flee, we have to shift away from the goal of being therapeutic and focus on the goal of harm reduction. In assault cases, two clinician errors I see are:

- people had a sense that something was dangerous, but they ignored or dampened it

- people were passive when tension was mounting and didn’t abort an assault situation.

Anger is easy to recognize. Raised voice, inappropriate staring, clenched fists, agitation, and verbal threats are common before a violent episode. This seems self-evident, yet it’s surprising—even when these signs are obvious—that clinicians often took no de-escalation measures to ward off violence. A verbal threat is a red flag to prepare for violence.

Dr. Krahn: So, your senses are tingling. What do you do?

Dr. Battaglia: If the patient is threatening you and is in a negative affective arousal state that does not allow verbal redirection, you need to get away. Before you make your move, however, announce your behavior so that the patient will not interpret it as an attack (“Bob, I am standing up now because I need to leave the room”).

Schizophrenia symptoms associated with violent behavior

Schizophrenia patients with combined low negative and high positive PANSS scores were at highest risk to cause bodily injury or harm someone with a weapon in the past 6 months.

Dr. Krahn: Can that be a difficult call?

Dr. Battaglia: I think you learn when to shift gears. You undergo a number of incidents where you question yourself, and you go to an experienced colleague and say, “I was in a session with this patient. Here’s what I did. Do you think I was exposing myself unnecessarily?” Go over the incident in detail with someone who is supportive and understanding but also has a critical eye.

Dr. Krahn: Any suggestions as to how the room or other staff can be positioned to keep the risk as low as possible? Do you recommend alarms inside offices?

Dr. Battaglia: I think it’s smart to have an alarm system. And you need to think about the physical layout of the room ahead of time. You and the patient may need to have equal access to the door. If the patient is high-risk, you might want to arrange seating at a 90-degree angle rather than face-to-face to limit sustained confrontational eye contact. You might want to place your chair greater than an arm swing or leg kick away. You need to decide whether it’s safe to be alone, and whether to have the door open or to have security posted.

Dr. Krahn: What kind of training should staff be given?

Dr. Battaglia: Every office should have policies and protocols for handling behavioral emergencies. Who calls 911? What are each person’s responsibilities? Also, staff should be confident but not confrontational. That, in itself, may dissuade a patient from acting out.

Everyone should be taught de-escalation techniques. Body language can send threatening signals or they can signal a person that you’re not a threat and you’re going to work with them.

Dr. Krahn: Can you give an example where training might have helped?

Dr. Battaglia: I recently reviewed an incident where a nurse and a psychologist had a delusional, paranoid patient in their office and he wanted to leave. He was relapsed and clearly agitated; he was psychotic; he needed to be hospitalized. He wanted to escape, and they barred the door because they wanted to get him in the hospital.

The patient punched the nurse. If you bar someone’s escape, you’re very likely to get hurt. Let the patient go and call the police, who are trained to bring people in.

Dr. Krahn: What about building security? I know of a situation where a patient was found waiting for a psychiatrist in the parking garage. If there are threats, should an escort system be in place?

Dr. Battaglia: Security needs to work with the staff to come up with a plan.

Dr. Krahn: If someone in your office is assaulted, how do you handle the aftermath?

Dr. Battaglia: The person who is assaulted needs to get help. Crisis debriefing has been debated in trauma treatment, but there’s no debate about the benefit of “psychological first aid.” It provides an opportunity for the person to talk in confidence with another professional about what’s happened and how it may be affecting him or her.

Dr. Krahn: Can you continue to treat someone who has assaulted you?

Dr. Battaglia: That decision has to be made on a case-by-case basis. The main question is whether you feel safe enough to be therapeutic with the person in the future. Outside of a controlled setting, I don’t think you can effectively treat a patient you fear.

Dr. Krahn: Dr. Fenton’s death brings home that we need to be vigilant each day. We meet new patients every week, and any of them may have the disorders and risk factors that can lead to violence.

Dr. Battaglia: That’s true, yet being in a constant state of fear can impair mental health professionals’ ability to do our work. It’s a dynamic balance—we attempt a measured calmness in our work yet pay attention to external and visceral cues of impending danger.

Dr. Krahn: I think some psychiatrists feel patient violence occurs only in correctional settings or emergency rooms—not in their world. But Dr. Fenton’s death shows that it can happen anywhere. You just don’t know.

Related resources

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of HealthCare Organizations (JCAHO). Rules on application of seclusion and restraint. www.jointcommission.org.

Acknowledgment

This article was edited by Lynn Waltz, a medical writer and editor in Norfolk, VA, from the transcript of the September 29, 2006 interview of Dr. Battaglia by Dr. Krahn.

1. Nolan P, Dallender J, Soares J, et al. Violence in mental health care: the experiences of mental health nurses and psychiatrists. J Adv Nurs 1999;30:934-41.

2. Flannery RB, Jr, Juliano J, Cronin S, Walker AP. Characteristics of assaultive psychiatric patients: fifteen-year analysis of the Assaulted Staff Action Program (ASAP). Psychiatr Q 2006;77(3):239-49.

3. Fazel S, Grann M. The population impact of severe mental illness on violent crime. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(8):1397-403.

4. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn RA, et al. A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63(5):490-9.

5. Cheung P, Schweitzer I, Crowley K, et al. Violence in schizophrenia: role of hallucinations and delusions. Schizophr Res 1997;26:181-90.

6. Binder R, McNiel D. Effects of diagnosis and context on dangerousness. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:728-32.

7. Hyman S. The violent patient. In: Hyman S (ed). Manual of psychiatric emergencies. Boston: Little, Brown and Co, 1988;23-31.

8. Swartz M, Swanson J, Hiday V, et al. Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:226-31.

9. Convit A, Isay D, Otis D, et al. Characteristics of repeatedly assaultive psychiatric inpatients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:1112-5.

10. Taylor P. Motives for offending among violent and psychotic men. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:491-8.

Wayne Fenton, MD, an associate director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), was murdered September 3—allegedly by a patient—in his Bethesda, MD, office. The case has led other mental health professionals to wonder how susceptible they are to assault and whether they are doing all they can to protect themselves.

To explore these safety issues, Current Psychiatry Deputy Editor Lois E. Krahn, MD, talked with John Battaglia, MD, medical director of the Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) in Madison, WI.

Dr. Battaglia’s work takes him into the community to treat patients with severe chronic mental illnesses. The Madison PACT program uses an intensive, team-based approach for patients who have been inadequately treated in usual mental health services. Patients with complicated psychiatric, social, and legal problems are seen in their homes, at work, or on the streets in an assertive and comprehensive style of case management.

Dr. Krahn: Dr. Fenton’s death was a tremendous loss to the psychiatric community.

Dr. Battaglia: We were all shaken; my first reaction was horror and sadness.

Dr. Krahn: Dr. Fenton was a very experienced psychiatrist (Box 1). His murder makes us think about our own vulnerability and wonder if such an assault could happen to us.

Dr. Battaglia: Yes, it’s very common for psychiatrists or mental health providers to be assaulted (Box 2).

Dr. Fenton devoted his life to schizophrenia, through his compassion for those afflicted and his research that aided untold numbers of the mentally ill and their caregivers.

So it was especially sad that Dr. Fenton died while reaching out to a patient in need. On September 3, the NIMH associate director answered an urgent call to help a distressed, psychotic young man. A short time later, Dr. Fenton was found beaten to death at his Bethesda, MD, office.

Dr. Fenton was just 53 when he died, but his accomplishments were great. He joined NIMH in 1999, helping the organization find new treatments to enable schizophrenia patients to function in society. In this role, he galvanized colleagues nationwide to tackle the complex issue of difficult-to-treat schizophrenia. Before joining NIMH, Dr. Fenton was director and CEO of the Chestnut Lodge Hospital in Rockville, MD, where he did pivotal long-term studies of therapies for schizophrenia. From 2000 to 2005, he was deputy editor-in-chief of the journal Schizophrenia Bulletin. He served on numerous boards and in advocacy roles and won numerous awards.

In addition to these responsibilities, Dr. Fenton made time for his patients. And he gave his life, as he had lived it, trying to help. His obituary in the Washington Post included this quotation from Dr. Fenton, whom the newspaper interviewed in 2002:

All one has to do is walk through a downtown area to appreciate that the availability of adequate treatment for patients with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses is a serious problem for the country. We wouldn’t let our 80-year-old mother with Alzheimer’s live on a grate. Why is it all right for a 30-year-old daughter with schizophrenia?

In one study, more than 50% of psychiatrists and 75% of mental health nurses reported experiencing an act or threat of violence within the past year.1

Dr. Krahn: Have you been assaulted by a patient?

Dr. Battaglia: Yes I have, and I think we need to define assault. A 15-year analysis of assaults on staff in a Massachusetts mental health system divided the acts into four types: physical, sexual, nonverbal threats/intimidation, and verbal assault.2 And you might think physical assault would be worse than verbal assaults. But a threat from a patient—especially one aimed toward your family—can leave you feeling vulnerable, stressed, and hypervigilant. Every sound at night makes you wonder if that person is coming after your family.

Dr. Krahn: What kinds of patients are associated with violence and assault?

Dr. Battaglia: The DSM-IV-TR diagnosis that comes up most often is schizophrenia, but it’s debatable whether diagnosis alone increases the risk of violence.

A study in Sweden published this year found a definite correlation between severe mental illness and violent crime. The authors concluded that about 5% of violent crimes in that country were committed by persons with severe mental illness.3

Also this year, a study of data from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) found an increased risk of violence in schizophrenia patients with positive psychotic symptoms but a decreased risk in those with predominantly negative symptoms such as social withdrawal. Those with a combination of above-median positive and below-median negative symptoms were at highest risk for serious violence (Box 3).

Among a sample of 1,410 chronic schizophrenia patients enrolled in the NIMH-sponsored CATIE, 19% were involved in either minor or serious violent behavior in the past 6 months and 3.6% in serious violent behavior.4

Nobody argues that someone with schizophrenia is clearly at higher risk of becoming violent when in a high arousal state with positive symptoms or unpleasant delusions or hallucinations. A person with schizophrenia who is in an agitated, aroused psychotic state with active paranoid delusions and hallucinations is clearly at higher risk for committing violence.5,6 The patient who has been charged in the beating death of Dr. Fenton was a 19-year-old man with severe psychosis.

Dr. Krahn: Are there other disorders, such as bipolar mania, that are high risk for patient violence?

Dr. Battaglia: Acute manic states are higher risk.7 But, again, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in and of itself does not show an increased incidence of violence. Personality disorders can be higher risk, as can nonspecific neurologic abnormalities, such as abnormal EEGs or neurologic “soft signs” by exam or testing.

Dr. Krahn: What about substance abuse?

Dr. Battaglia: The risk of violence is higher in patients who are under the influence of certain stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamines, as opposed to marijuana or sedatives.8

Dr. Krahn: How can we predict whether a patient is at high risk for assault?

Dr. Battaglia: The best predictor is a history of violence, especially when the act was unprovoked or resulted in injury.9 A small number of patients is responsible for the majority of aggression. One study showed that recidivists committed 53% of all violent acts in a health care setting.10

Dr. Krahn: What if the patient’s history is unknown?

Dr. Battaglia: Most assaults in health care occur in high arousal states. Planned, methodical assaults are significantly less frequent. So, in the case of patients making threats against staff—let’s say you terminated your relationship with a patient and obtained a restraining order—very commonly that patient’s passion toward the clinic will wane over time.

Dr. Krahn: But not every arousal state results in assault.

Dr. Battaglia: Right. I have a colleague who says, “Risk factors make you worry more, and nothing makes you worry less.” That’s the attitude to have. Nothing should make you lower your antenna.

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, National Crime Victimization Survey, 1993 to 1999

Dr. Krahn: Is the risk higher with a new patient, or does it go down as you establish a relationship?

Dr. Battaglia: Clearly, untreated patients in high arousal states are a much greater risk. Does risk go down with somebody you’ve known for a while? I don’t know. My own experiences with assault have sometimes occurred with people I’ve grown to trust and when I let my guard down.

Dr. Krahn: So we might relax once we know the patient, but then we might be more vulnerable. Any clues that should put us on high alert?

Dr. Battaglia: The first clue—and this is going to sound obvious—is our internal, visceral, emotional sense of impending danger. In my experience, psychiatrists have a very good sense of that, but we override or don’t pay attention to it. Part of that inattention is an occupational hazard; we have to turn off our sense of danger again and again so that we can stay in situations that would repulse most people.

For instance, medical students with no psychiatric experience might sit in an interview with an agitated patient and feel an intense need to flee. Their antennae are telling them the situation looks dangerous. Seasoned psychiatrists, however, will calm themselves and stay through the interview. We are so used to being healers and helpers that we often turn off or dampen our sense of danger.

Dr. Krahn: Can you elaborate?

Dr. Battaglia: A nurse and I were with a patient who was highly agitated. He was labile; he was angry; he was spitting as he was speaking. In any other context, people would be keeping their distance because the signals were so powerful. Instead, the nurse leaned in, held his hand, and started telling him, “Come on now (Bob), you need to settle down. This is scaring us.”

That’s what I call the “leaning-in response.” We do that day in and day out. We turn off our danger signals in order to be therapeutic, and that makes us vulnerable.

Dr. Krahn: So, how do we keep our signals tuned?

Dr. Battaglia: When our senses are telling us we’re scared or we’re noticing a feeling of wanting to flee, we have to shift away from the goal of being therapeutic and focus on the goal of harm reduction. In assault cases, two clinician errors I see are:

- people had a sense that something was dangerous, but they ignored or dampened it

- people were passive when tension was mounting and didn’t abort an assault situation.

Anger is easy to recognize. Raised voice, inappropriate staring, clenched fists, agitation, and verbal threats are common before a violent episode. This seems self-evident, yet it’s surprising—even when these signs are obvious—that clinicians often took no de-escalation measures to ward off violence. A verbal threat is a red flag to prepare for violence.

Dr. Krahn: So, your senses are tingling. What do you do?

Dr. Battaglia: If the patient is threatening you and is in a negative affective arousal state that does not allow verbal redirection, you need to get away. Before you make your move, however, announce your behavior so that the patient will not interpret it as an attack (“Bob, I am standing up now because I need to leave the room”).

Schizophrenia symptoms associated with violent behavior

Schizophrenia patients with combined low negative and high positive PANSS scores were at highest risk to cause bodily injury or harm someone with a weapon in the past 6 months.

Dr. Krahn: Can that be a difficult call?

Dr. Battaglia: I think you learn when to shift gears. You undergo a number of incidents where you question yourself, and you go to an experienced colleague and say, “I was in a session with this patient. Here’s what I did. Do you think I was exposing myself unnecessarily?” Go over the incident in detail with someone who is supportive and understanding but also has a critical eye.

Dr. Krahn: Any suggestions as to how the room or other staff can be positioned to keep the risk as low as possible? Do you recommend alarms inside offices?

Dr. Battaglia: I think it’s smart to have an alarm system. And you need to think about the physical layout of the room ahead of time. You and the patient may need to have equal access to the door. If the patient is high-risk, you might want to arrange seating at a 90-degree angle rather than face-to-face to limit sustained confrontational eye contact. You might want to place your chair greater than an arm swing or leg kick away. You need to decide whether it’s safe to be alone, and whether to have the door open or to have security posted.

Dr. Krahn: What kind of training should staff be given?

Dr. Battaglia: Every office should have policies and protocols for handling behavioral emergencies. Who calls 911? What are each person’s responsibilities? Also, staff should be confident but not confrontational. That, in itself, may dissuade a patient from acting out.

Everyone should be taught de-escalation techniques. Body language can send threatening signals or they can signal a person that you’re not a threat and you’re going to work with them.

Dr. Krahn: Can you give an example where training might have helped?

Dr. Battaglia: I recently reviewed an incident where a nurse and a psychologist had a delusional, paranoid patient in their office and he wanted to leave. He was relapsed and clearly agitated; he was psychotic; he needed to be hospitalized. He wanted to escape, and they barred the door because they wanted to get him in the hospital.

The patient punched the nurse. If you bar someone’s escape, you’re very likely to get hurt. Let the patient go and call the police, who are trained to bring people in.

Dr. Krahn: What about building security? I know of a situation where a patient was found waiting for a psychiatrist in the parking garage. If there are threats, should an escort system be in place?

Dr. Battaglia: Security needs to work with the staff to come up with a plan.

Dr. Krahn: If someone in your office is assaulted, how do you handle the aftermath?

Dr. Battaglia: The person who is assaulted needs to get help. Crisis debriefing has been debated in trauma treatment, but there’s no debate about the benefit of “psychological first aid.” It provides an opportunity for the person to talk in confidence with another professional about what’s happened and how it may be affecting him or her.

Dr. Krahn: Can you continue to treat someone who has assaulted you?

Dr. Battaglia: That decision has to be made on a case-by-case basis. The main question is whether you feel safe enough to be therapeutic with the person in the future. Outside of a controlled setting, I don’t think you can effectively treat a patient you fear.

Dr. Krahn: Dr. Fenton’s death brings home that we need to be vigilant each day. We meet new patients every week, and any of them may have the disorders and risk factors that can lead to violence.

Dr. Battaglia: That’s true, yet being in a constant state of fear can impair mental health professionals’ ability to do our work. It’s a dynamic balance—we attempt a measured calmness in our work yet pay attention to external and visceral cues of impending danger.

Dr. Krahn: I think some psychiatrists feel patient violence occurs only in correctional settings or emergency rooms—not in their world. But Dr. Fenton’s death shows that it can happen anywhere. You just don’t know.

Related resources

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of HealthCare Organizations (JCAHO). Rules on application of seclusion and restraint. www.jointcommission.org.

Acknowledgment

This article was edited by Lynn Waltz, a medical writer and editor in Norfolk, VA, from the transcript of the September 29, 2006 interview of Dr. Battaglia by Dr. Krahn.

Wayne Fenton, MD, an associate director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), was murdered September 3—allegedly by a patient—in his Bethesda, MD, office. The case has led other mental health professionals to wonder how susceptible they are to assault and whether they are doing all they can to protect themselves.

To explore these safety issues, Current Psychiatry Deputy Editor Lois E. Krahn, MD, talked with John Battaglia, MD, medical director of the Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) in Madison, WI.

Dr. Battaglia’s work takes him into the community to treat patients with severe chronic mental illnesses. The Madison PACT program uses an intensive, team-based approach for patients who have been inadequately treated in usual mental health services. Patients with complicated psychiatric, social, and legal problems are seen in their homes, at work, or on the streets in an assertive and comprehensive style of case management.

Dr. Krahn: Dr. Fenton’s death was a tremendous loss to the psychiatric community.

Dr. Battaglia: We were all shaken; my first reaction was horror and sadness.

Dr. Krahn: Dr. Fenton was a very experienced psychiatrist (Box 1). His murder makes us think about our own vulnerability and wonder if such an assault could happen to us.

Dr. Battaglia: Yes, it’s very common for psychiatrists or mental health providers to be assaulted (Box 2).

Dr. Fenton devoted his life to schizophrenia, through his compassion for those afflicted and his research that aided untold numbers of the mentally ill and their caregivers.

So it was especially sad that Dr. Fenton died while reaching out to a patient in need. On September 3, the NIMH associate director answered an urgent call to help a distressed, psychotic young man. A short time later, Dr. Fenton was found beaten to death at his Bethesda, MD, office.

Dr. Fenton was just 53 when he died, but his accomplishments were great. He joined NIMH in 1999, helping the organization find new treatments to enable schizophrenia patients to function in society. In this role, he galvanized colleagues nationwide to tackle the complex issue of difficult-to-treat schizophrenia. Before joining NIMH, Dr. Fenton was director and CEO of the Chestnut Lodge Hospital in Rockville, MD, where he did pivotal long-term studies of therapies for schizophrenia. From 2000 to 2005, he was deputy editor-in-chief of the journal Schizophrenia Bulletin. He served on numerous boards and in advocacy roles and won numerous awards.

In addition to these responsibilities, Dr. Fenton made time for his patients. And he gave his life, as he had lived it, trying to help. His obituary in the Washington Post included this quotation from Dr. Fenton, whom the newspaper interviewed in 2002:

All one has to do is walk through a downtown area to appreciate that the availability of adequate treatment for patients with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses is a serious problem for the country. We wouldn’t let our 80-year-old mother with Alzheimer’s live on a grate. Why is it all right for a 30-year-old daughter with schizophrenia?

In one study, more than 50% of psychiatrists and 75% of mental health nurses reported experiencing an act or threat of violence within the past year.1

Dr. Krahn: Have you been assaulted by a patient?

Dr. Battaglia: Yes I have, and I think we need to define assault. A 15-year analysis of assaults on staff in a Massachusetts mental health system divided the acts into four types: physical, sexual, nonverbal threats/intimidation, and verbal assault.2 And you might think physical assault would be worse than verbal assaults. But a threat from a patient—especially one aimed toward your family—can leave you feeling vulnerable, stressed, and hypervigilant. Every sound at night makes you wonder if that person is coming after your family.

Dr. Krahn: What kinds of patients are associated with violence and assault?

Dr. Battaglia: The DSM-IV-TR diagnosis that comes up most often is schizophrenia, but it’s debatable whether diagnosis alone increases the risk of violence.

A study in Sweden published this year found a definite correlation between severe mental illness and violent crime. The authors concluded that about 5% of violent crimes in that country were committed by persons with severe mental illness.3

Also this year, a study of data from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) found an increased risk of violence in schizophrenia patients with positive psychotic symptoms but a decreased risk in those with predominantly negative symptoms such as social withdrawal. Those with a combination of above-median positive and below-median negative symptoms were at highest risk for serious violence (Box 3).

Among a sample of 1,410 chronic schizophrenia patients enrolled in the NIMH-sponsored CATIE, 19% were involved in either minor or serious violent behavior in the past 6 months and 3.6% in serious violent behavior.4

Nobody argues that someone with schizophrenia is clearly at higher risk of becoming violent when in a high arousal state with positive symptoms or unpleasant delusions or hallucinations. A person with schizophrenia who is in an agitated, aroused psychotic state with active paranoid delusions and hallucinations is clearly at higher risk for committing violence.5,6 The patient who has been charged in the beating death of Dr. Fenton was a 19-year-old man with severe psychosis.

Dr. Krahn: Are there other disorders, such as bipolar mania, that are high risk for patient violence?

Dr. Battaglia: Acute manic states are higher risk.7 But, again, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in and of itself does not show an increased incidence of violence. Personality disorders can be higher risk, as can nonspecific neurologic abnormalities, such as abnormal EEGs or neurologic “soft signs” by exam or testing.

Dr. Krahn: What about substance abuse?

Dr. Battaglia: The risk of violence is higher in patients who are under the influence of certain stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamines, as opposed to marijuana or sedatives.8

Dr. Krahn: How can we predict whether a patient is at high risk for assault?

Dr. Battaglia: The best predictor is a history of violence, especially when the act was unprovoked or resulted in injury.9 A small number of patients is responsible for the majority of aggression. One study showed that recidivists committed 53% of all violent acts in a health care setting.10

Dr. Krahn: What if the patient’s history is unknown?

Dr. Battaglia: Most assaults in health care occur in high arousal states. Planned, methodical assaults are significantly less frequent. So, in the case of patients making threats against staff—let’s say you terminated your relationship with a patient and obtained a restraining order—very commonly that patient’s passion toward the clinic will wane over time.

Dr. Krahn: But not every arousal state results in assault.

Dr. Battaglia: Right. I have a colleague who says, “Risk factors make you worry more, and nothing makes you worry less.” That’s the attitude to have. Nothing should make you lower your antenna.

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, National Crime Victimization Survey, 1993 to 1999

Dr. Krahn: Is the risk higher with a new patient, or does it go down as you establish a relationship?

Dr. Battaglia: Clearly, untreated patients in high arousal states are a much greater risk. Does risk go down with somebody you’ve known for a while? I don’t know. My own experiences with assault have sometimes occurred with people I’ve grown to trust and when I let my guard down.

Dr. Krahn: So we might relax once we know the patient, but then we might be more vulnerable. Any clues that should put us on high alert?

Dr. Battaglia: The first clue—and this is going to sound obvious—is our internal, visceral, emotional sense of impending danger. In my experience, psychiatrists have a very good sense of that, but we override or don’t pay attention to it. Part of that inattention is an occupational hazard; we have to turn off our sense of danger again and again so that we can stay in situations that would repulse most people.

For instance, medical students with no psychiatric experience might sit in an interview with an agitated patient and feel an intense need to flee. Their antennae are telling them the situation looks dangerous. Seasoned psychiatrists, however, will calm themselves and stay through the interview. We are so used to being healers and helpers that we often turn off or dampen our sense of danger.

Dr. Krahn: Can you elaborate?

Dr. Battaglia: A nurse and I were with a patient who was highly agitated. He was labile; he was angry; he was spitting as he was speaking. In any other context, people would be keeping their distance because the signals were so powerful. Instead, the nurse leaned in, held his hand, and started telling him, “Come on now (Bob), you need to settle down. This is scaring us.”

That’s what I call the “leaning-in response.” We do that day in and day out. We turn off our danger signals in order to be therapeutic, and that makes us vulnerable.

Dr. Krahn: So, how do we keep our signals tuned?

Dr. Battaglia: When our senses are telling us we’re scared or we’re noticing a feeling of wanting to flee, we have to shift away from the goal of being therapeutic and focus on the goal of harm reduction. In assault cases, two clinician errors I see are:

- people had a sense that something was dangerous, but they ignored or dampened it

- people were passive when tension was mounting and didn’t abort an assault situation.

Anger is easy to recognize. Raised voice, inappropriate staring, clenched fists, agitation, and verbal threats are common before a violent episode. This seems self-evident, yet it’s surprising—even when these signs are obvious—that clinicians often took no de-escalation measures to ward off violence. A verbal threat is a red flag to prepare for violence.

Dr. Krahn: So, your senses are tingling. What do you do?

Dr. Battaglia: If the patient is threatening you and is in a negative affective arousal state that does not allow verbal redirection, you need to get away. Before you make your move, however, announce your behavior so that the patient will not interpret it as an attack (“Bob, I am standing up now because I need to leave the room”).

Schizophrenia symptoms associated with violent behavior

Schizophrenia patients with combined low negative and high positive PANSS scores were at highest risk to cause bodily injury or harm someone with a weapon in the past 6 months.

Dr. Krahn: Can that be a difficult call?

Dr. Battaglia: I think you learn when to shift gears. You undergo a number of incidents where you question yourself, and you go to an experienced colleague and say, “I was in a session with this patient. Here’s what I did. Do you think I was exposing myself unnecessarily?” Go over the incident in detail with someone who is supportive and understanding but also has a critical eye.

Dr. Krahn: Any suggestions as to how the room or other staff can be positioned to keep the risk as low as possible? Do you recommend alarms inside offices?

Dr. Battaglia: I think it’s smart to have an alarm system. And you need to think about the physical layout of the room ahead of time. You and the patient may need to have equal access to the door. If the patient is high-risk, you might want to arrange seating at a 90-degree angle rather than face-to-face to limit sustained confrontational eye contact. You might want to place your chair greater than an arm swing or leg kick away. You need to decide whether it’s safe to be alone, and whether to have the door open or to have security posted.

Dr. Krahn: What kind of training should staff be given?

Dr. Battaglia: Every office should have policies and protocols for handling behavioral emergencies. Who calls 911? What are each person’s responsibilities? Also, staff should be confident but not confrontational. That, in itself, may dissuade a patient from acting out.

Everyone should be taught de-escalation techniques. Body language can send threatening signals or they can signal a person that you’re not a threat and you’re going to work with them.

Dr. Krahn: Can you give an example where training might have helped?

Dr. Battaglia: I recently reviewed an incident where a nurse and a psychologist had a delusional, paranoid patient in their office and he wanted to leave. He was relapsed and clearly agitated; he was psychotic; he needed to be hospitalized. He wanted to escape, and they barred the door because they wanted to get him in the hospital.

The patient punched the nurse. If you bar someone’s escape, you’re very likely to get hurt. Let the patient go and call the police, who are trained to bring people in.

Dr. Krahn: What about building security? I know of a situation where a patient was found waiting for a psychiatrist in the parking garage. If there are threats, should an escort system be in place?

Dr. Battaglia: Security needs to work with the staff to come up with a plan.

Dr. Krahn: If someone in your office is assaulted, how do you handle the aftermath?

Dr. Battaglia: The person who is assaulted needs to get help. Crisis debriefing has been debated in trauma treatment, but there’s no debate about the benefit of “psychological first aid.” It provides an opportunity for the person to talk in confidence with another professional about what’s happened and how it may be affecting him or her.

Dr. Krahn: Can you continue to treat someone who has assaulted you?

Dr. Battaglia: That decision has to be made on a case-by-case basis. The main question is whether you feel safe enough to be therapeutic with the person in the future. Outside of a controlled setting, I don’t think you can effectively treat a patient you fear.

Dr. Krahn: Dr. Fenton’s death brings home that we need to be vigilant each day. We meet new patients every week, and any of them may have the disorders and risk factors that can lead to violence.

Dr. Battaglia: That’s true, yet being in a constant state of fear can impair mental health professionals’ ability to do our work. It’s a dynamic balance—we attempt a measured calmness in our work yet pay attention to external and visceral cues of impending danger.

Dr. Krahn: I think some psychiatrists feel patient violence occurs only in correctional settings or emergency rooms—not in their world. But Dr. Fenton’s death shows that it can happen anywhere. You just don’t know.

Related resources

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of HealthCare Organizations (JCAHO). Rules on application of seclusion and restraint. www.jointcommission.org.

Acknowledgment

This article was edited by Lynn Waltz, a medical writer and editor in Norfolk, VA, from the transcript of the September 29, 2006 interview of Dr. Battaglia by Dr. Krahn.

1. Nolan P, Dallender J, Soares J, et al. Violence in mental health care: the experiences of mental health nurses and psychiatrists. J Adv Nurs 1999;30:934-41.

2. Flannery RB, Jr, Juliano J, Cronin S, Walker AP. Characteristics of assaultive psychiatric patients: fifteen-year analysis of the Assaulted Staff Action Program (ASAP). Psychiatr Q 2006;77(3):239-49.

3. Fazel S, Grann M. The population impact of severe mental illness on violent crime. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(8):1397-403.

4. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn RA, et al. A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63(5):490-9.

5. Cheung P, Schweitzer I, Crowley K, et al. Violence in schizophrenia: role of hallucinations and delusions. Schizophr Res 1997;26:181-90.

6. Binder R, McNiel D. Effects of diagnosis and context on dangerousness. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:728-32.

7. Hyman S. The violent patient. In: Hyman S (ed). Manual of psychiatric emergencies. Boston: Little, Brown and Co, 1988;23-31.

8. Swartz M, Swanson J, Hiday V, et al. Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:226-31.

9. Convit A, Isay D, Otis D, et al. Characteristics of repeatedly assaultive psychiatric inpatients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:1112-5.

10. Taylor P. Motives for offending among violent and psychotic men. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:491-8.

1. Nolan P, Dallender J, Soares J, et al. Violence in mental health care: the experiences of mental health nurses and psychiatrists. J Adv Nurs 1999;30:934-41.

2. Flannery RB, Jr, Juliano J, Cronin S, Walker AP. Characteristics of assaultive psychiatric patients: fifteen-year analysis of the Assaulted Staff Action Program (ASAP). Psychiatr Q 2006;77(3):239-49.

3. Fazel S, Grann M. The population impact of severe mental illness on violent crime. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(8):1397-403.

4. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn RA, et al. A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63(5):490-9.

5. Cheung P, Schweitzer I, Crowley K, et al. Violence in schizophrenia: role of hallucinations and delusions. Schizophr Res 1997;26:181-90.

6. Binder R, McNiel D. Effects of diagnosis and context on dangerousness. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:728-32.

7. Hyman S. The violent patient. In: Hyman S (ed). Manual of psychiatric emergencies. Boston: Little, Brown and Co, 1988;23-31.

8. Swartz M, Swanson J, Hiday V, et al. Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:226-31.

9. Convit A, Isay D, Otis D, et al. Characteristics of repeatedly assaultive psychiatric inpatients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:1112-5.

10. Taylor P. Motives for offending among violent and psychotic men. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:491-8.