User login

It sometimes seems that the pace of life, and its stresses, have spiraled out of control: There just never seems to be enough time to deal with all the directions in which we are pulled. This easily can lead to the exhaustion of physical or emotional strength or motivation, otherwise known as “burnout.” Burnout is physical or mental collapse caused by overwork or stress and we are all at risk of suffering it. Conflicting demands on our time, loss of control (real or imagined), and a diminishing sense of worth grind at us from every direction.

In general, having some control over schedule and hours worked is associated with reductions in burnout and improved job satisfaction.1 But this is not always the case. Well-intentioned efforts to reduce workload, such as the electronic medical records or physician order entry systems, have actually made the problem worse.2 The seeming level of control that comes with being the chair of an obstetrics and gynecology department does not necessarily reduce burnout rates,3 and neither does the perceived resilience of mental health professionals, who still report burnout rates that approach 25%.4

This article continues the focus on recalibrating work/life balance that began last month with “ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim,” by Lucia DiVenere, MA, and the peer-to-peer audiocast with Ms. DiVenere and myself titled “Is burnout on the rise and what are the signs ObGyns should be on the lookout for?” Here, I identify the causes and symptoms of burnout and provide specific tools to help you develop resilience.

Who is most at risk for burnout?

Estimates range from 40% to 75% of ObGyns currently suffer from professional burnout, making the lifetime risk a virtual certainty.1−3 The idea of professional burnout is not new, but wider recognition of the alarming rates of burnout is very current.4,5 A recent survey of gynecologic oncologists6 found that of those studied 30% scored high for emotional exhaustion, 10% high for depersonalization, and 11% low for personal accomplishment. Overall, 32% of physicians had scores indicating burnout. More worrisome was that 33% screened positive for depression, 13% had a history of suicidal ideation, 15% screened positive for alcohol abuse, and 34% reported impaired quality of life. Almost 40% would not encourage their children to enter medicine and more than 10% said that they would not enter medicine again if they had to do it over.

Residents and those at mid-career are particularly vulnerable,7 with resident burnout rates reported to be as high as 75%.8 Of surveyed residents in a 2012 study, 13% satisfied all 3 subscale scores for high burnout and greater than 50% had high levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion. Those with high levels of emotional exhaustion were less satisfied with their careers, regretted choosing obstetrics and gynecology, and had higher rates of depression—all findings consistent with older studies.

9,10

References

- Peckham C. Medscape Lifestyle Report 2016: Bias and Burnout. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2016/public/overview#page=1. Published January 13, 2016. Accessed July 7, 2016.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone, S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385.

- Martini S, Arfken CL, Churchill A, Balon R. Burnout comparison among residents in different medical specialties. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):240–242.

- Lee YY, Medford AR, Halim AS. Burnout in physicians. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2015;45(2):104–107.

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613.

- Rath KS, Huffman LB, Phillips GS, Carpenter KM, Fowler JM. Burnout and associated factors among members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):824.e1–e9.

- Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1358–1367.

- Govardhan LM, Pinelli V, Schnatz PF. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn Med. 2012;76(7):389–395.

- Becker JL, Milad MP, Klock SC. Burnout, depression, and career satisfaction: cross-sectional study of obstetrics and gynecology residents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(5):1444–1449.

- Castelo-Branco C, Figueras F, Eixarch E, et al. Stress symptoms and burnout in obstetric and gynaecology residents. BJOG. 2007;114(1):94–98

Why burnout occurs

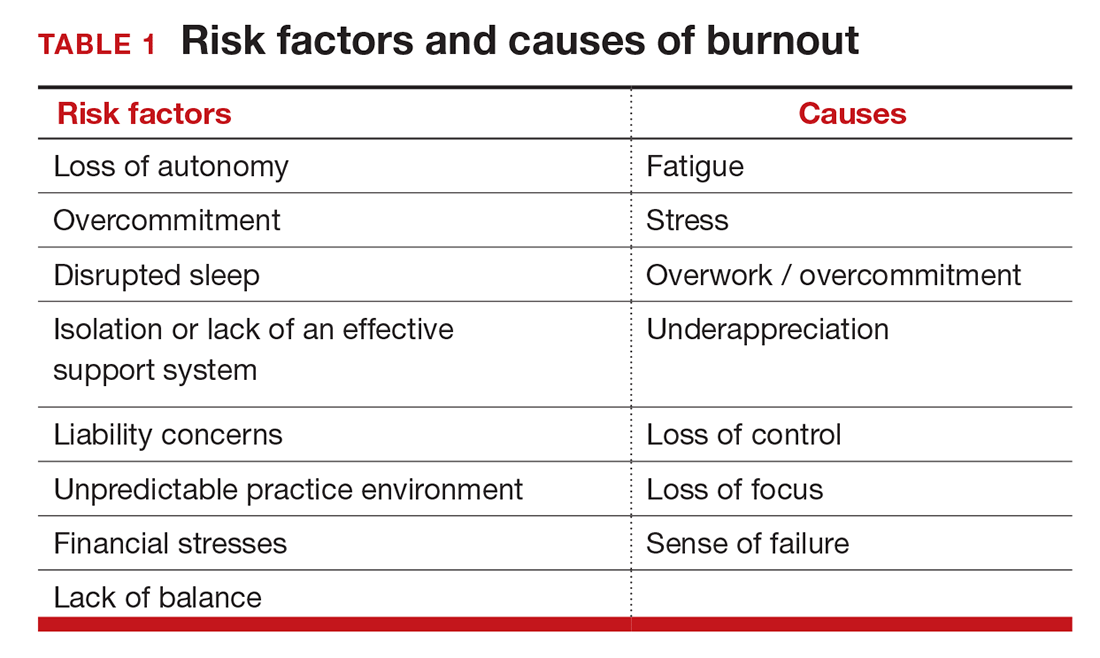

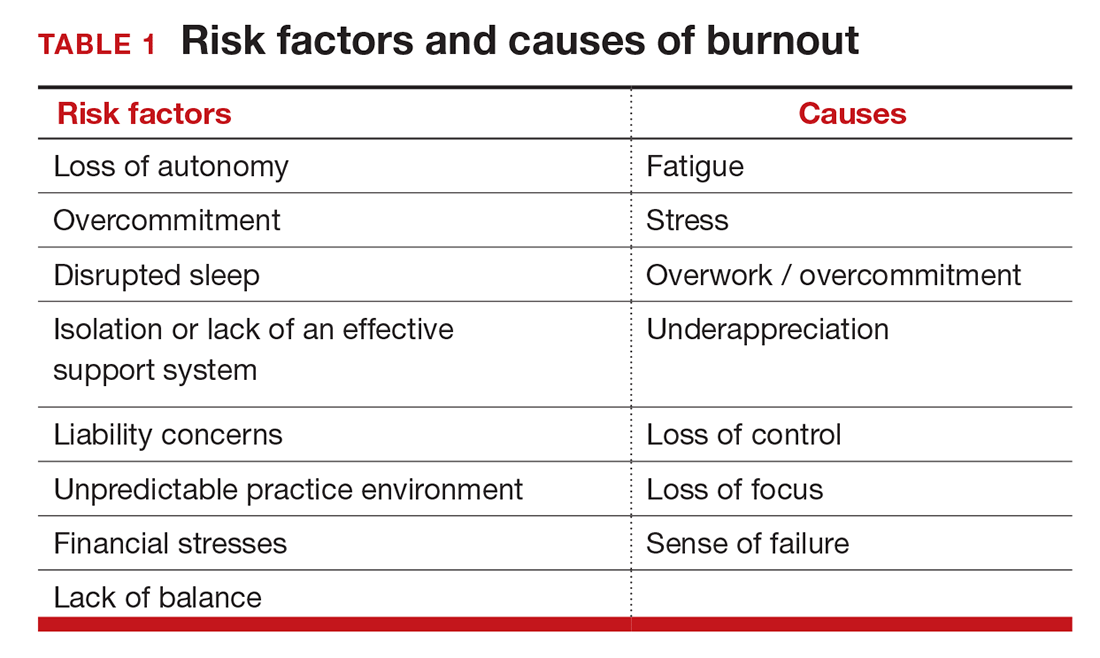

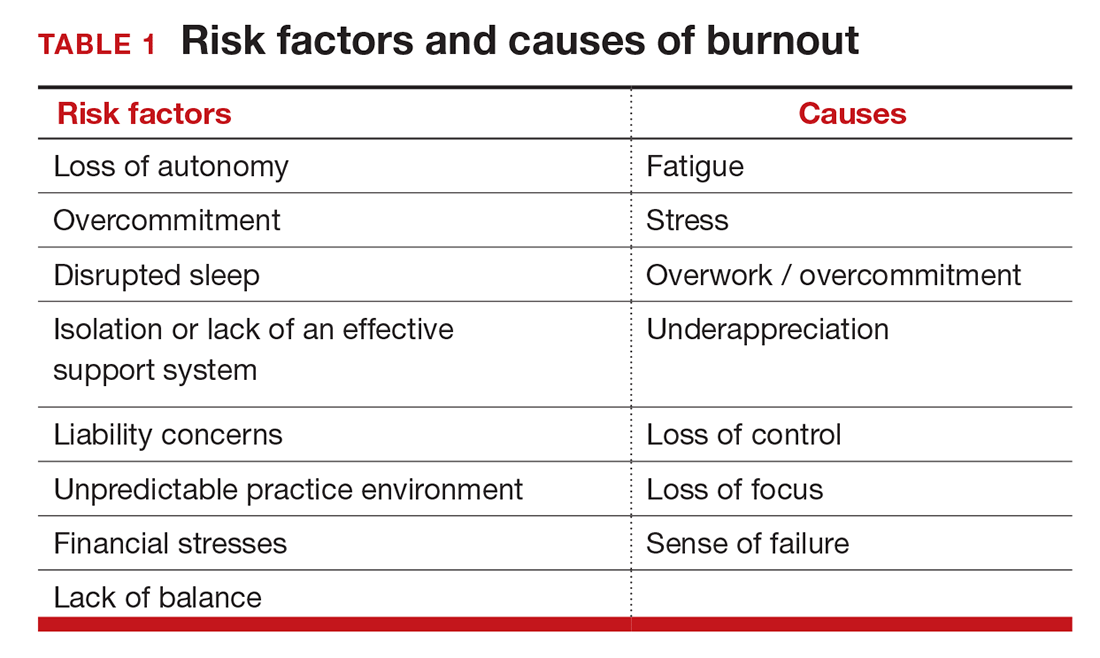

Simply identifying ourselves as professionals and the same attributes that make us successful as physicians (type-A behavior, obsessive-compulsive commitment to our profession) put us at risk for professional burnout (see “Who is most at risk for burnout?”). Those predilections combine with the forces from the world in which we live and practice to increase this threat (TABLE 1). Conditions in which there are weak retention rates, high turnover, heavy workloads, and low staffing levels or staffing shortages increase the risk of burnout and, when burnout is present, are associated with a degraded quality of care.5

Does stress cause burnout?

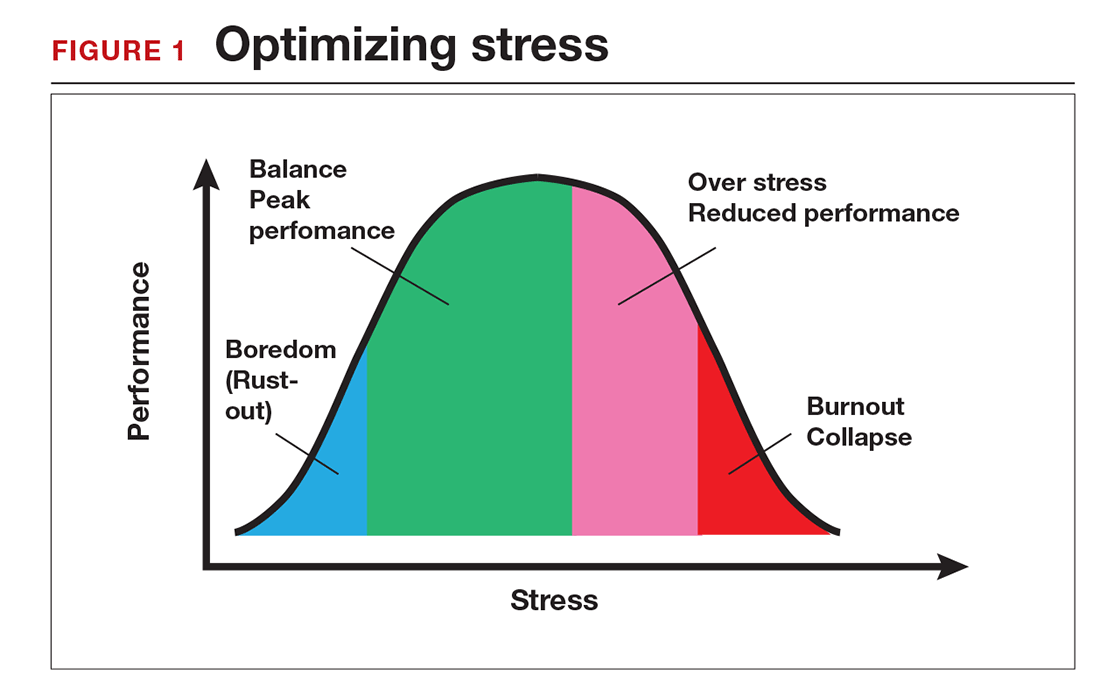

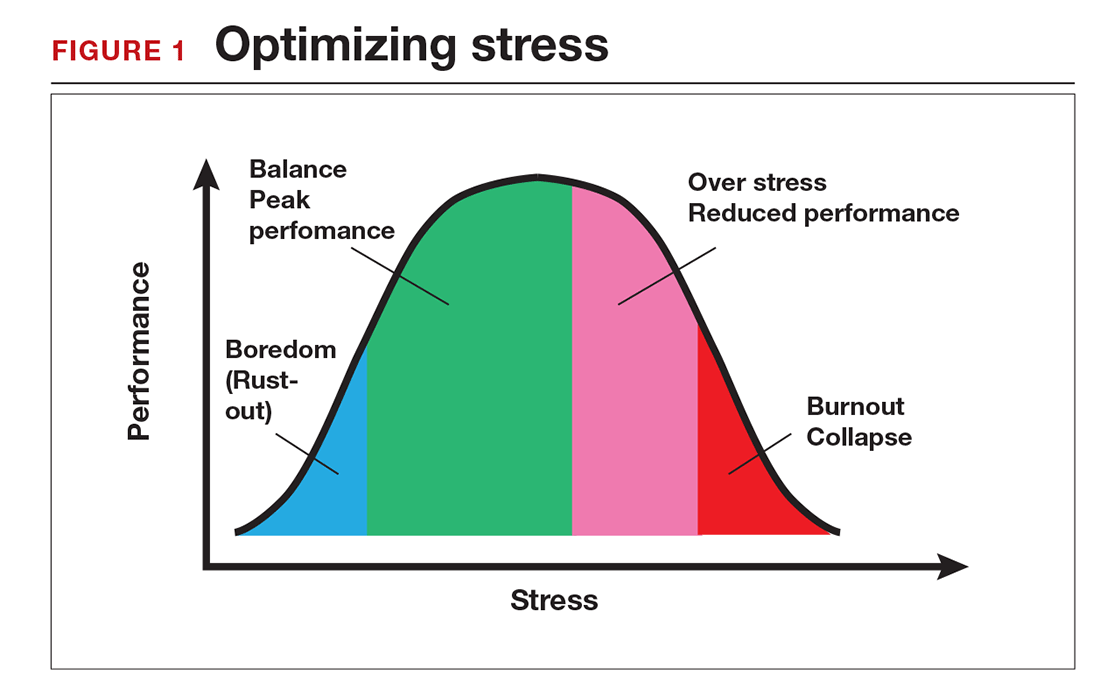

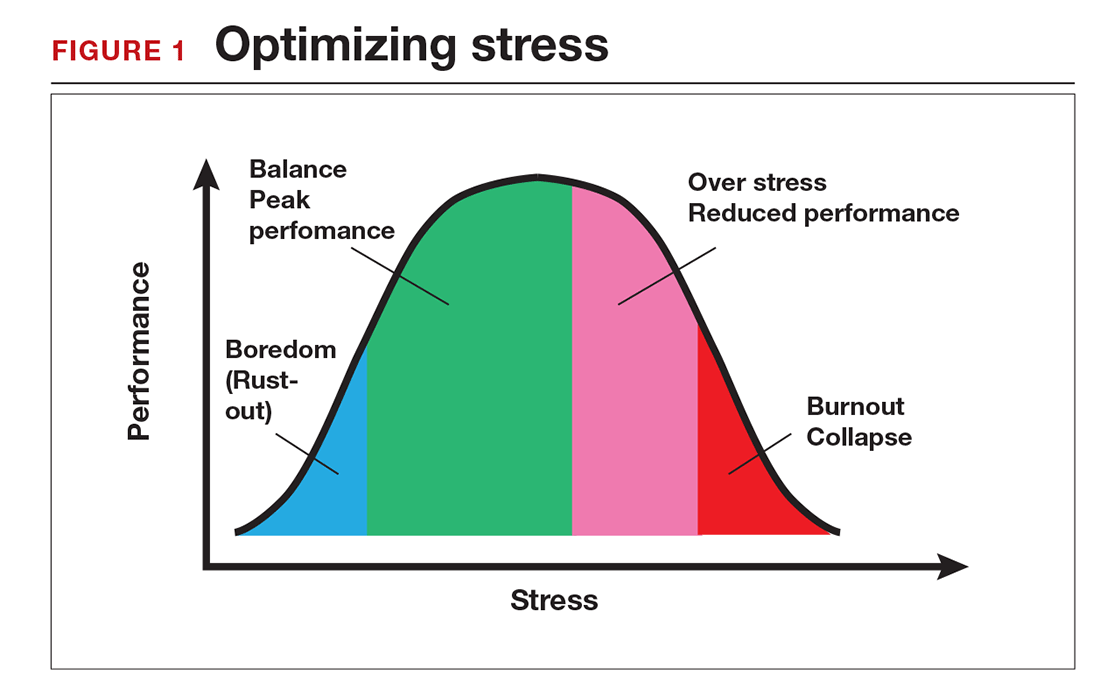

Stress is often seen as the reason for burnout. Research shows that there is no single source of burnout,6 however, and a number of factors combine to cause this physical or mental collapse. Stress can be a positive or negative factor in our performance. Too little stress and we feel underutilized; too much stress and we collapse from the strain.

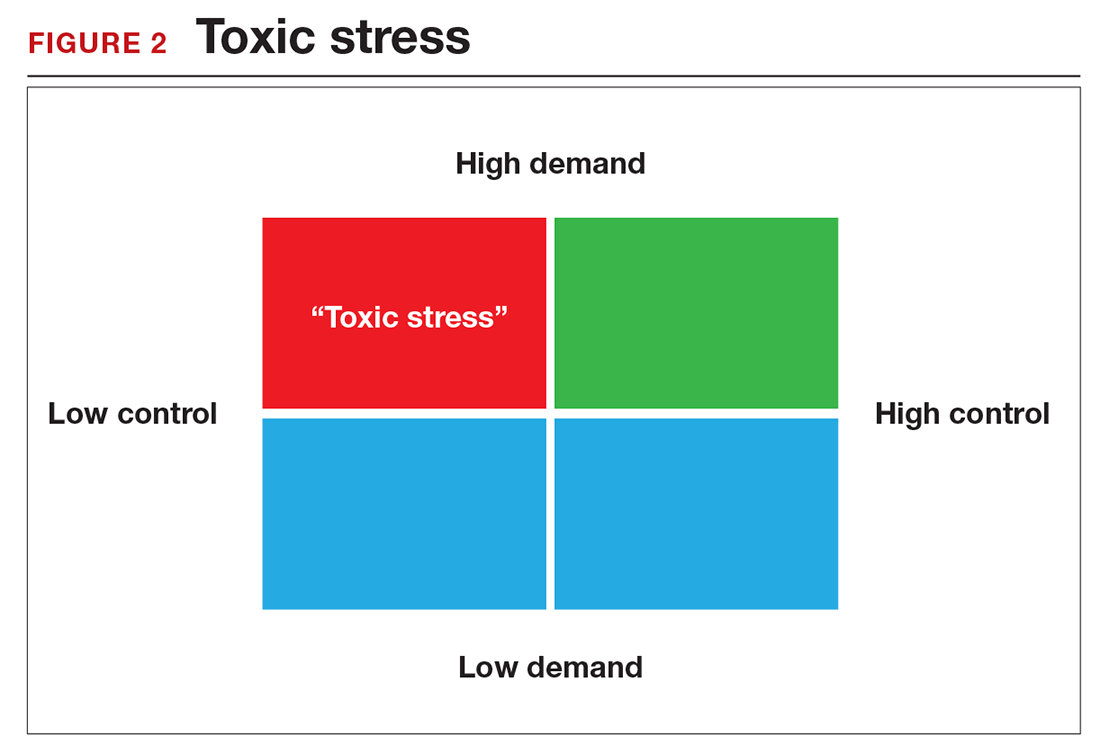

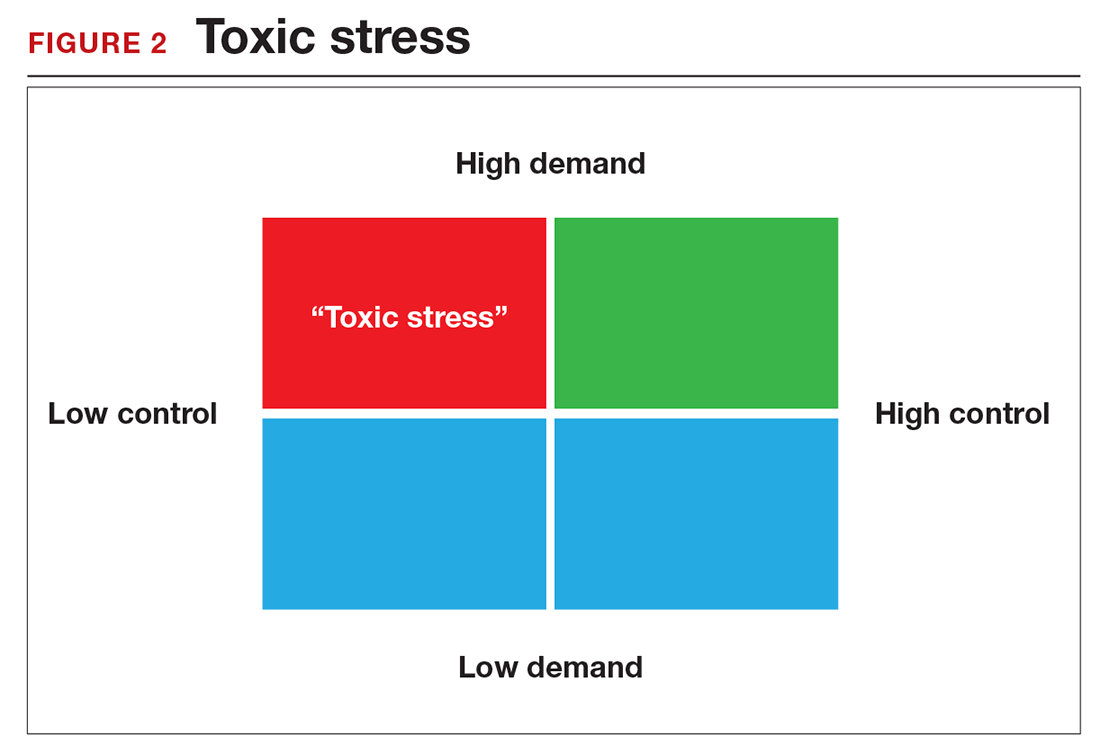

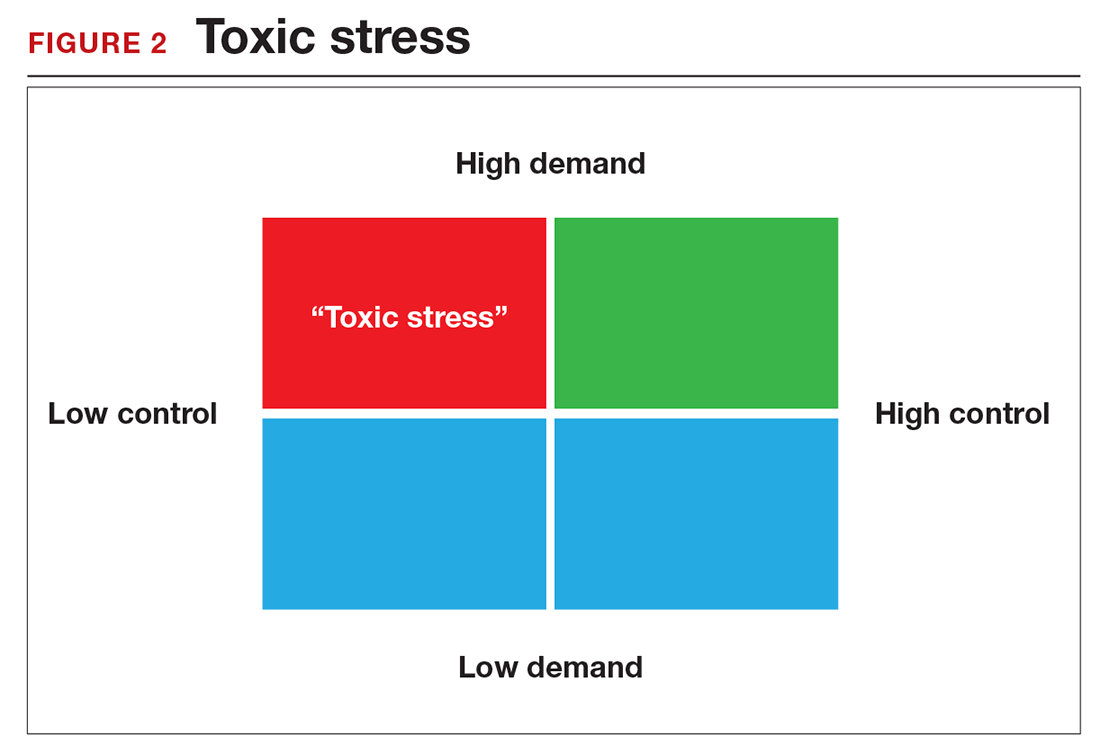

There is a middle ground where stress and expectations keep us focused and at peak productivity (FIGURE 1). The key is the balance between control and demand: When we have a greater level of control, we can handle high demands (FIGURE 2). It is when we lack that control that high demands result in what has been called “toxic stress,” and we collapse under the strain.

The impact of burnout

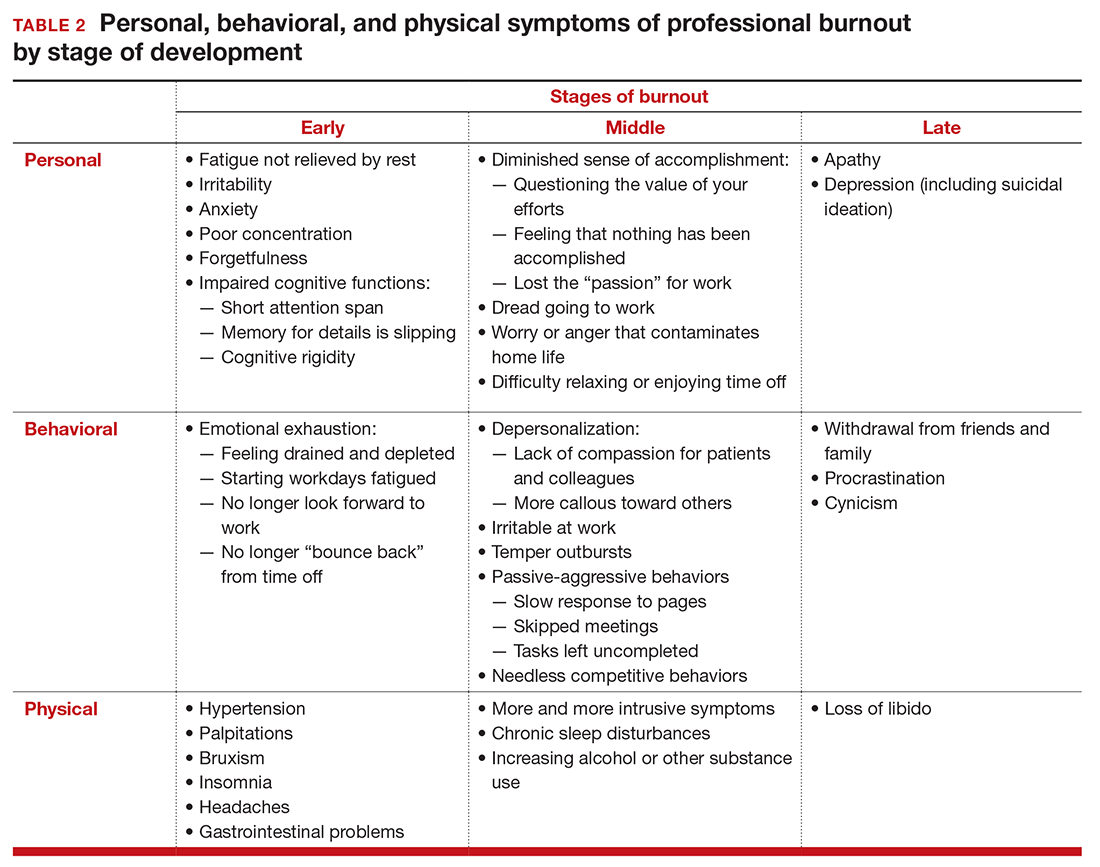

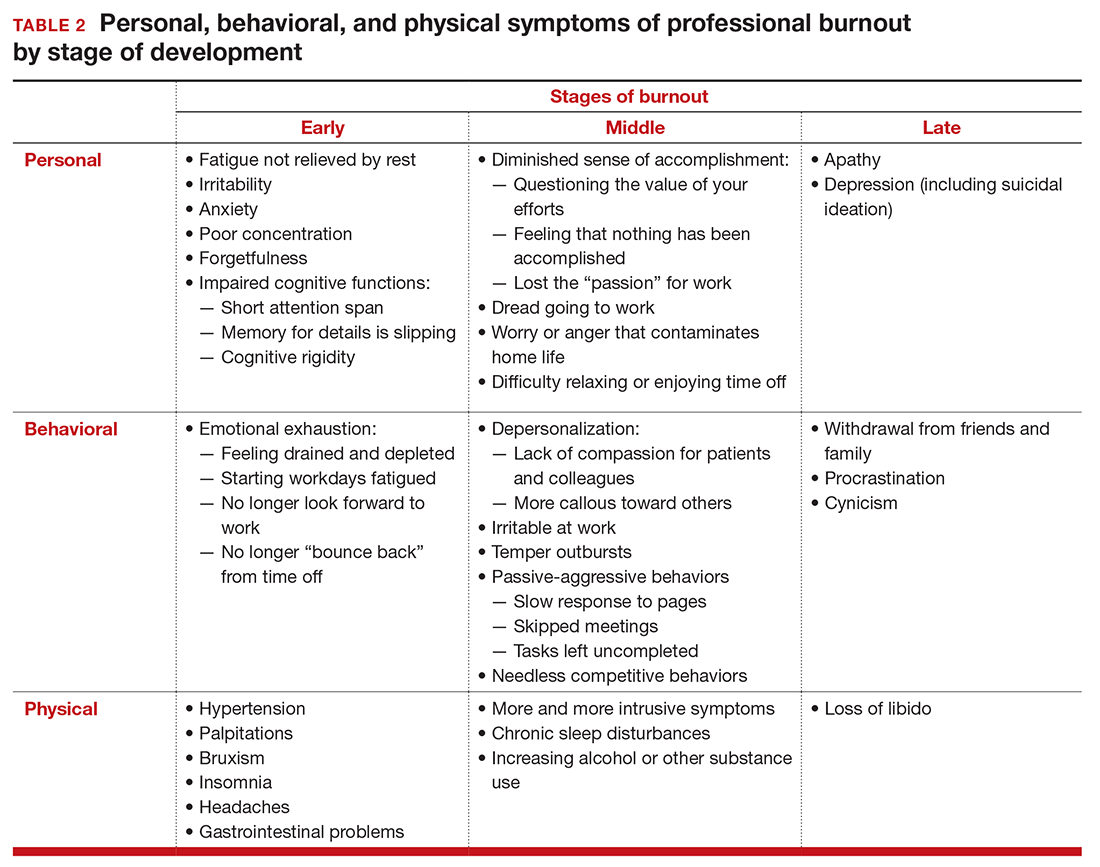

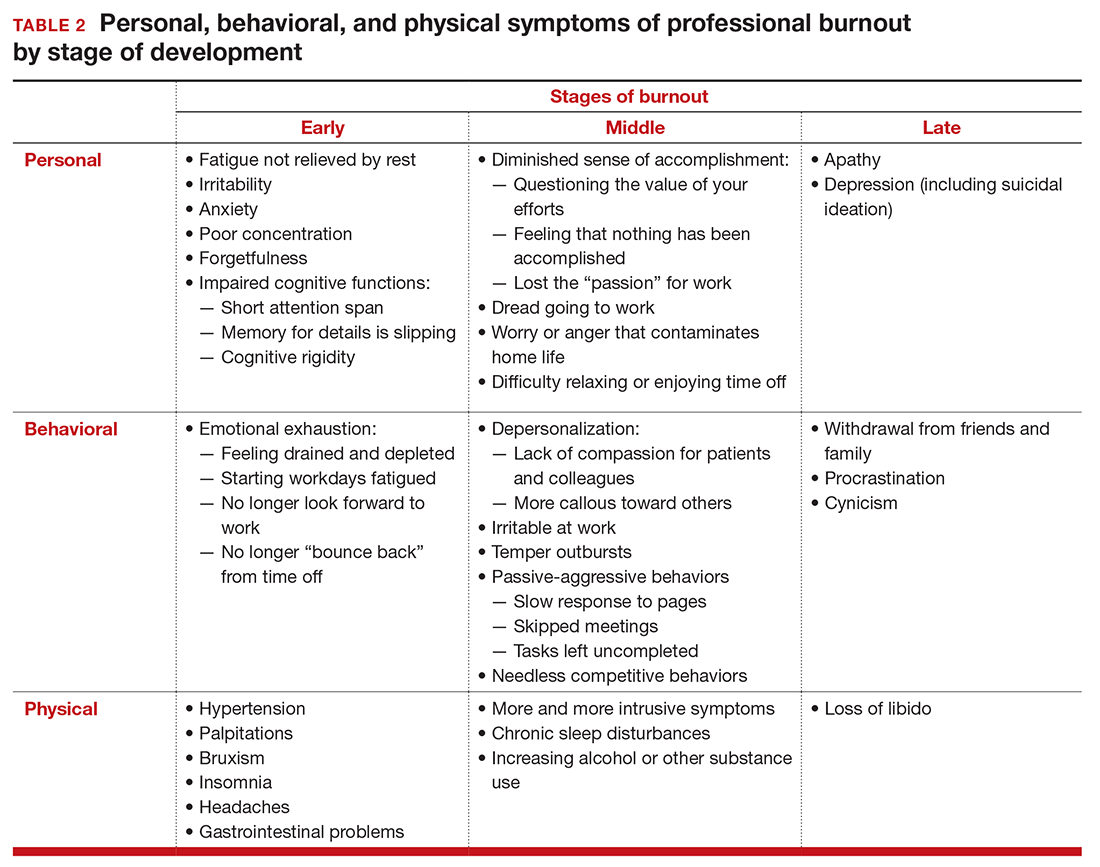

Burnout is associated with reduced performance and job satisfaction, increased rates of illness and absenteeism, accidents, premature retirement, and even premature death. Physically, stress induces the dry mouth, dilated pupils, and release of adrenalin and noradrenalin associated with the “fight-or-flight” reaction. The degree to which the physical, emotional, and professional symptoms are manifest depends on the depth or stage of burnout present (TABLE 2). Overall, burnout is associated with an increased risk for physical illness.7 Economically, the impact of physician burnout (for physicians practicing in Canada) has been estimated to be $213.1 million,8 which includes $185.2 million due to early retirement and $27.9 million due to reduced clinical hours.

“Do I have burnout?”

We all suffer from fatigue and have stress, but do we have burnout? With so many myths surrounding stress and burnout, it is sometimes hard to know where the truth lies. Some of those myths say that:

- you can leave your troubles at home

- mental stress does not affect physical performance

- stress is only for wimps

- stress and burnout are chemical imbalances that can be treated with medications

- stress is always bad

- burnout will get better if you just give it more time.

Maslach Burnout Inventory. The effective “gold standard” for diagnosing burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory,9 which operationalizes burnout as a 3-dimensional syndrome made up of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. Other diagnostic tools have been introduced10 but have not gained the wide acceptance of the Maslach Inventory. Some authors have argued that burnout and depression represent different, closely spaced points along a spectrum and that any effort to separate them may be artificial.11,12

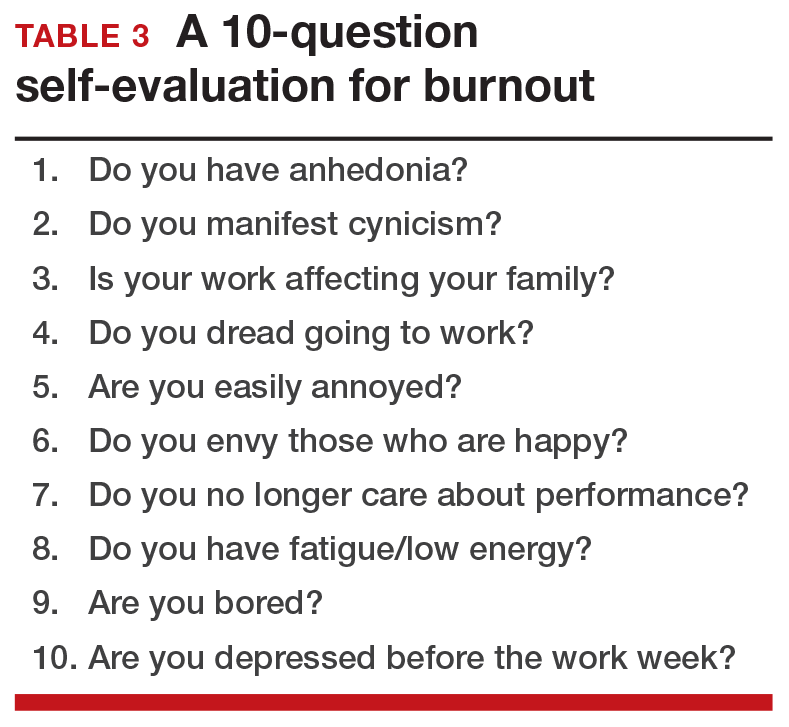

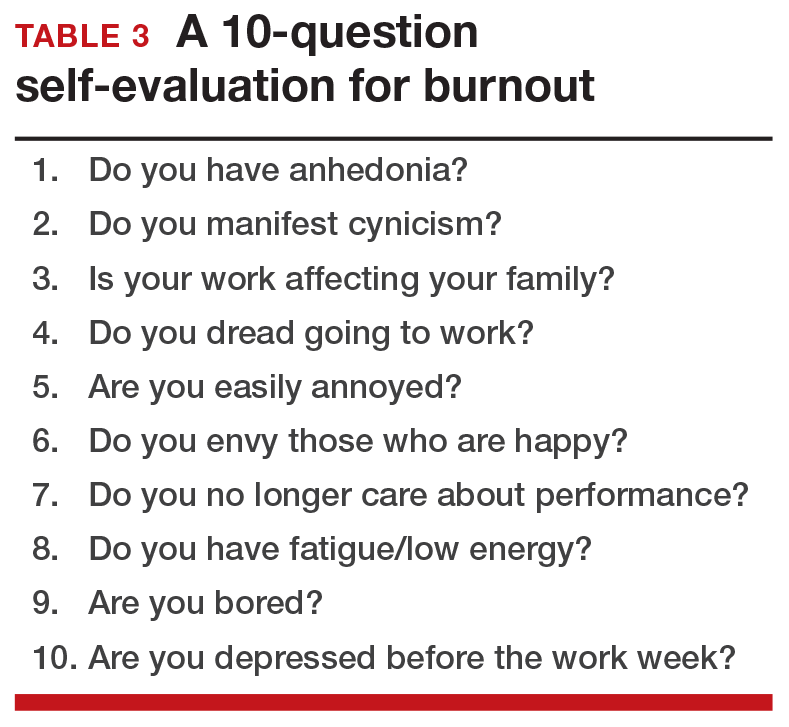

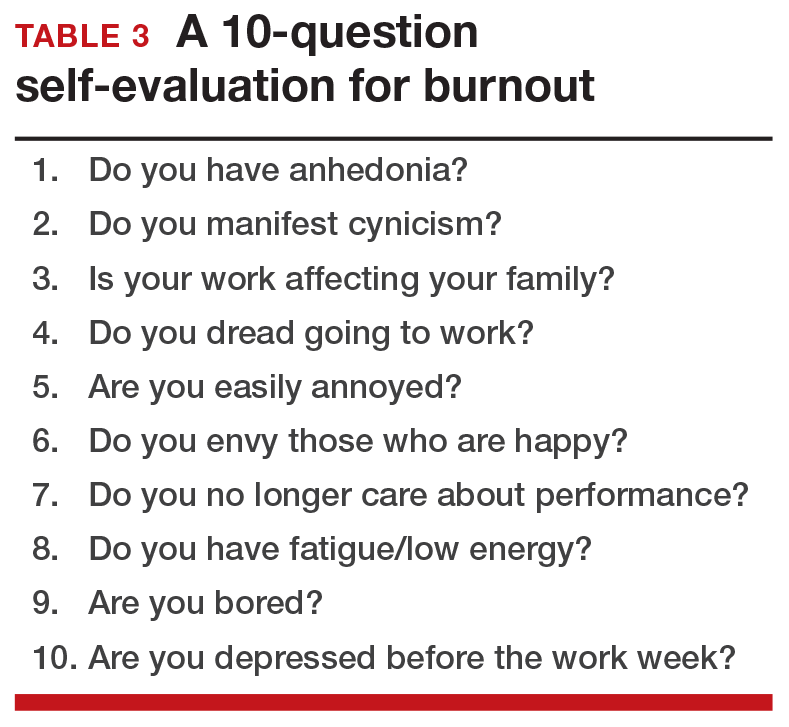

The Maslach Burnout Inventory consists of a survey of 22 items; it requires a fee to take and is interpreted by a qualified individual. A simpler screening test consists of 10 questions (TABLE 3). If you answer “yes” to 5 or more of the questions, you probably have burnout. An even quicker test is to see, when you go on vacation, if your symptoms disappear. If so, you are not depressed; you have burnout. (If you cannot even go on vacation, then it is almost certain.)

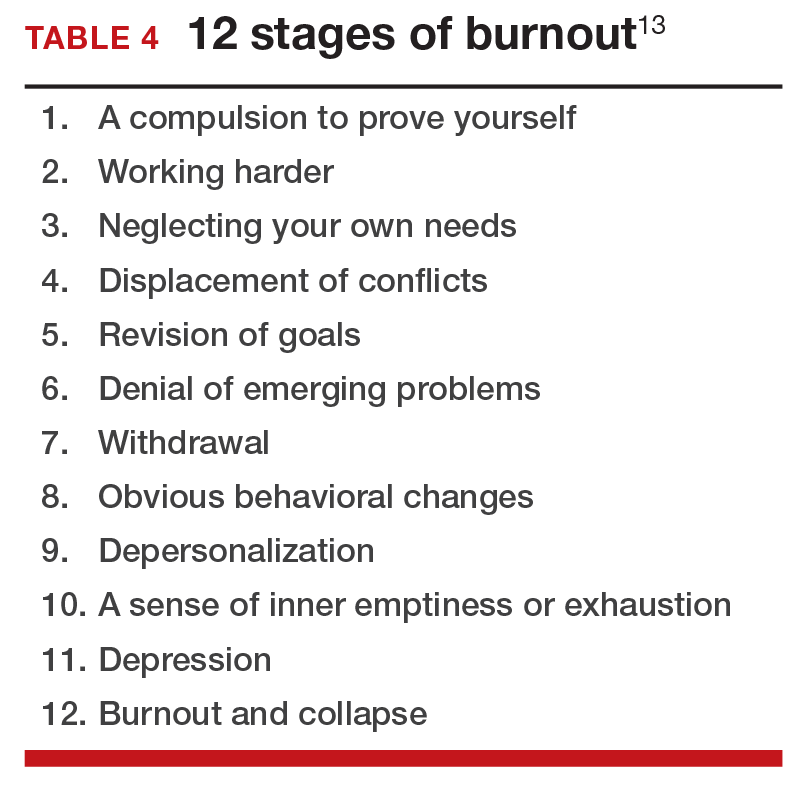

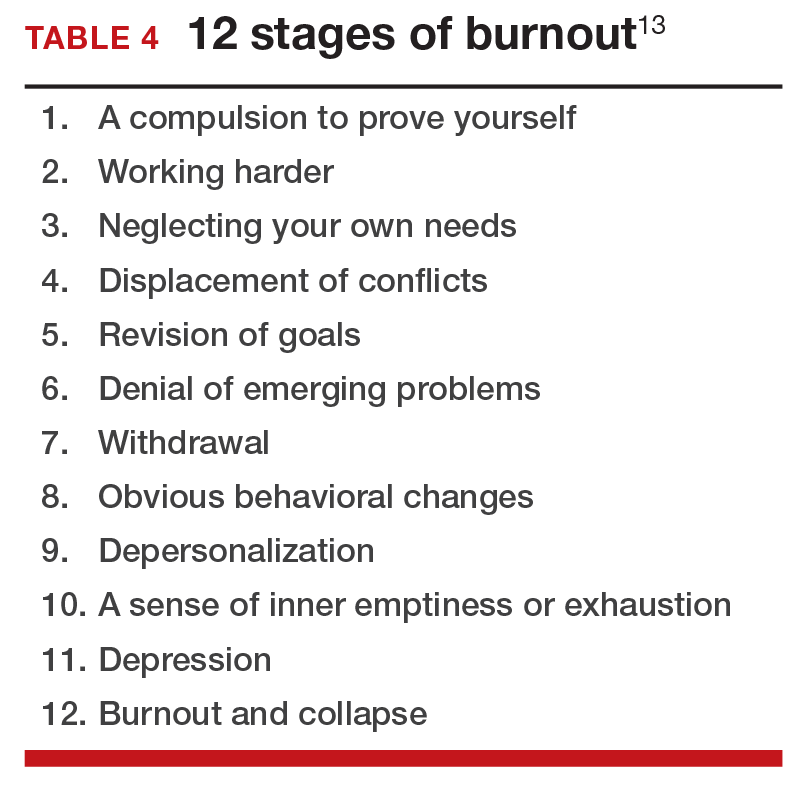

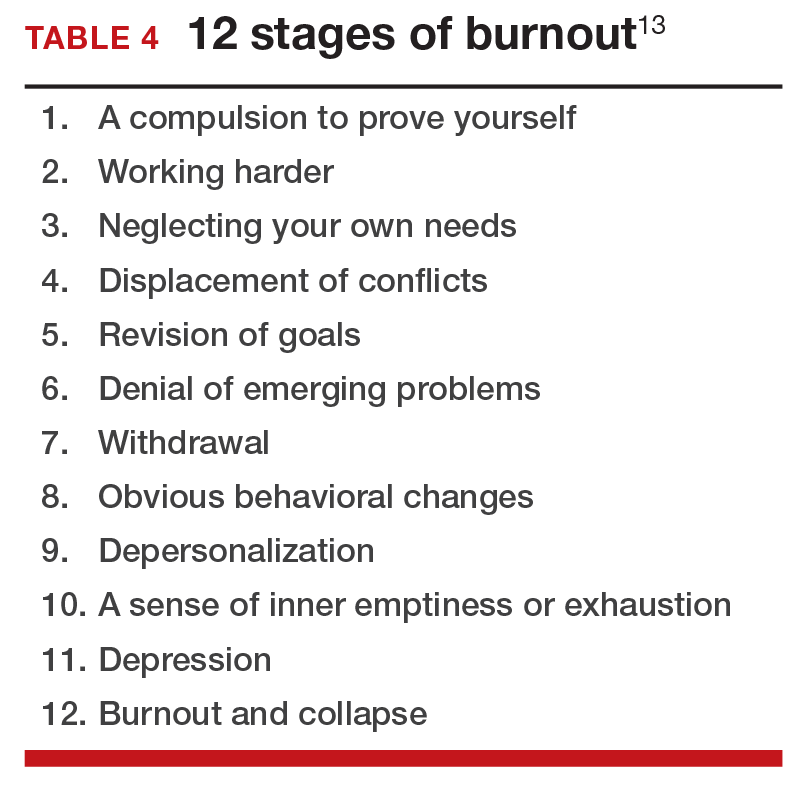

12 stages of burnout. Psychologists Herbert Freudenberger and Gail North have theorized that the burnout process can be divided into 12 phases (TABLE 4).13 These stages are not necessarily sequential—some may be absent and others may present simultaneously. It is easy to see how these can represent stages in a potentially spiraling series of behaviors and changes that result in complete dysfunction. It is also easy to understand that the characteristics that are associated with success in medical school, clinical training, and practice, such as high expectations, placing the needs of others above our own, and a desire to prove oneself, virtually define the first 3 stages.

Approaches for burnout control and prevention

There are some simple steps we can take to reduce the risk of burnout or to reverse its effects. Because fatigue and stress are 2 of the greatest risk factors, reducing these is a good place to start.

Prioritize sleep. When it comes to fatigue, that one is easy: get some sleep. Physicians tend to sleep fewer hours than the general population and what we get is often not the type that is restful and restorative.14 Just reducing the number of hours worked is not enough, as a number of studies have found.15 The rest must result in relaxation.

e Stress reduction may seem a more difficult goal than getting more sleep. In reality, there are several simple approaches to use to reduce stress:

- Even though we all have busy clinical schedules, take short breaks to rest, sing, laugh, and exercise. Even breaks as short as 10 minutes can be effective.16

- Separate work from private life by taking a short break to resolve issues before heading home. Avoiding “baggage” or homework will go a long way to giving you the perspective you need from your time off. This may also mean that you have to delegate tasks, share chores, or get carry-out for dinner.

- Set meaningful and realistic goals for yourself professionally and personally. Do not expect or demand more than is possible. This will mean setting priorities and recognizing that some tasks may have to wait.

- Finally, do not forget to pay yourself with hobbies and activities that you enjoy.

Take action

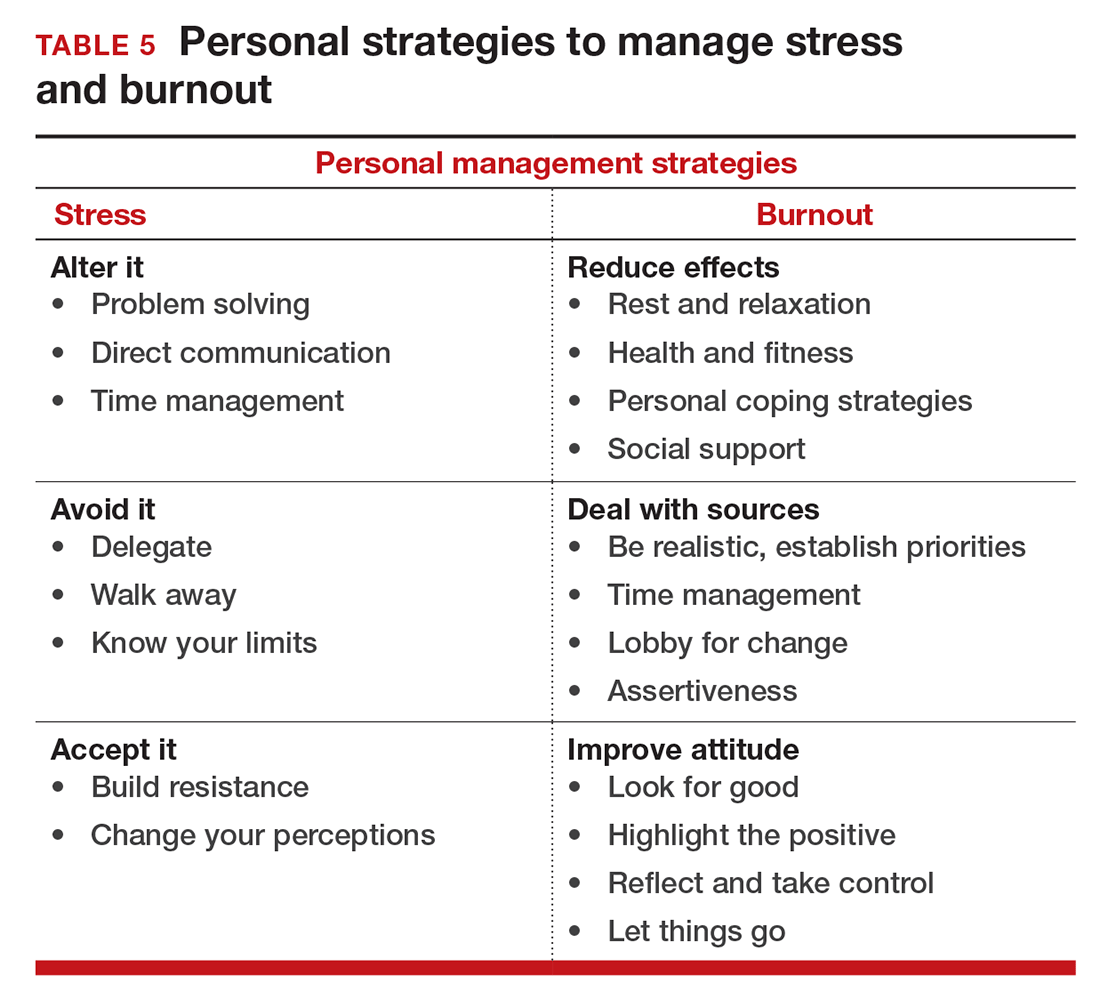

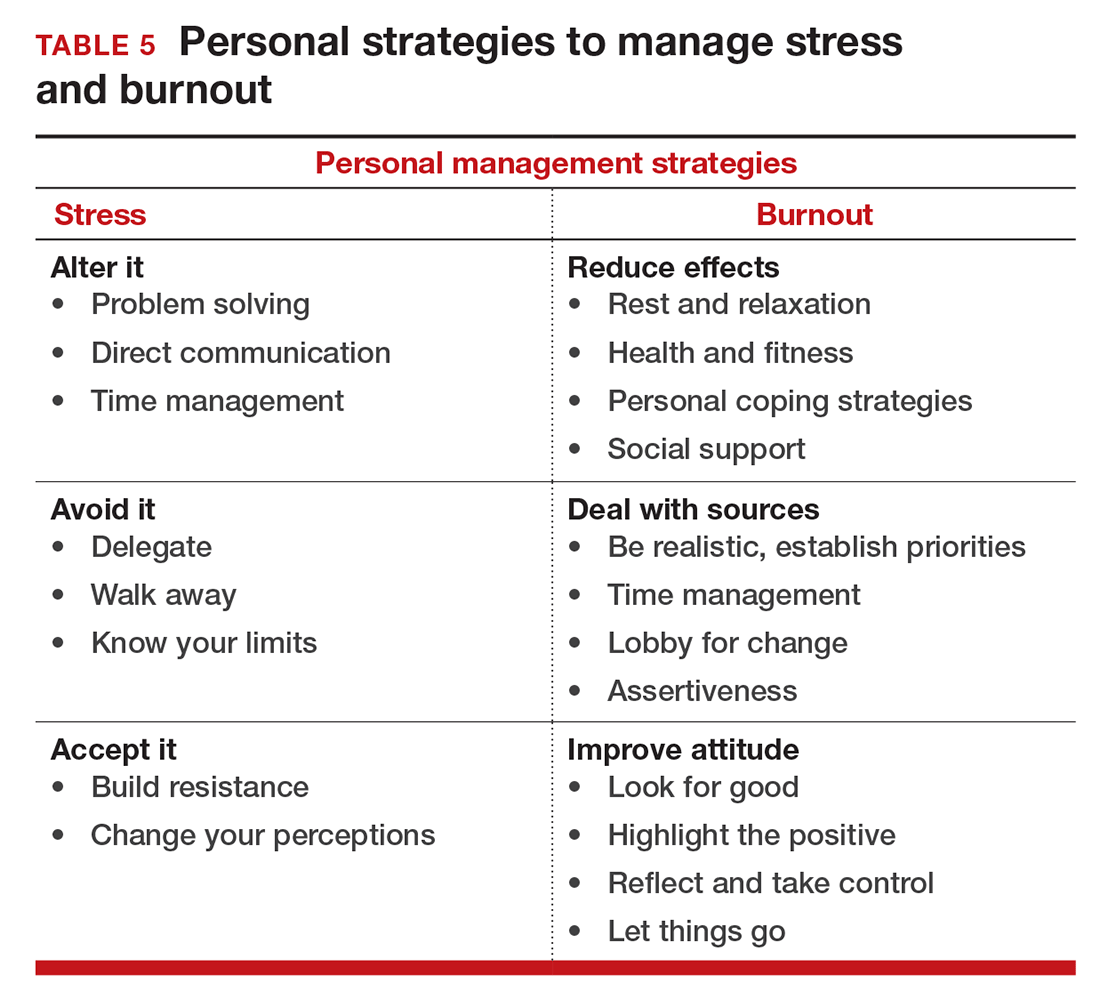

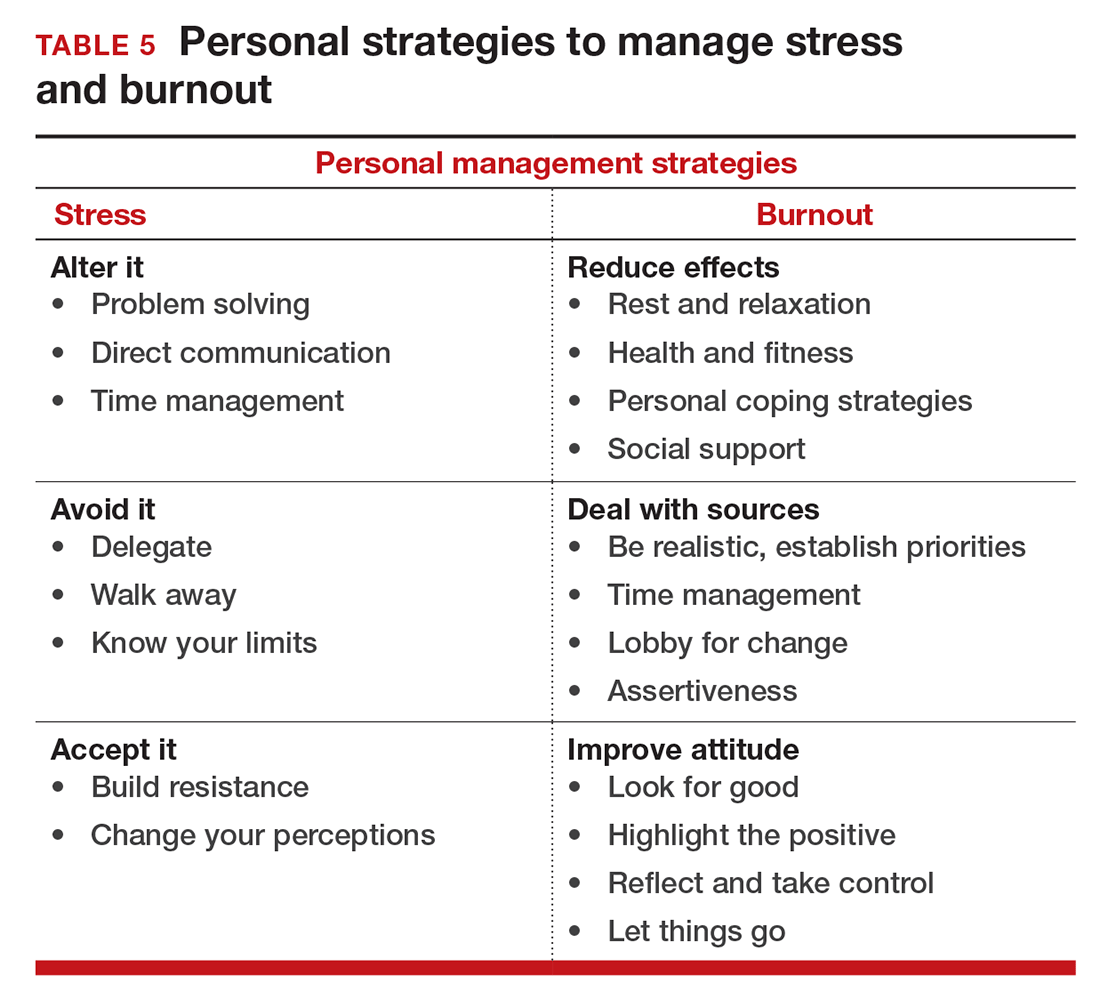

If you feel the effects of burnout tugging at your coattails, you can reduce the effects, deal with the sources, and improve your attitude (TABLE 5). Rest and relaxation will go a long way to helping, but do not forget to take care of your physical well-being with a healthy diet, exercise, and health checkups. Deal with the sources of burnout by identifying the stressors, setting realistic priorities, and practicing good time management.

You also should lobby for changes that will increase your control and reduce unnecessary obstacles to completing your goals. Be your own best advocate. Look for the good and try to identify at least one instance during the day where your presence or acts made a difference. In the end, it is like Smokey the Bear says, “Only you can prevent burnout.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Keeton K, Fenner DE, Johnson TR, Hayward RA. Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work-life balance, and burnout. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):949-955.

- Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836-848.

- Gabbe SG, Melville J, Mandel L, Walker E. Burnout in chairs of obstetrics and gynecology: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(4):601-612.

- Kok BC, Herrell RK, Grossman SH, West JC, Wilk JE. Prevalence of professional burnout among military mental health service providers. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(1):137-140.

- Humphries N, Morgan K, Conry MC, McGowan Y, Montgomery A, McGee H. Quality of care and health professional burnout: narrative literature review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2014;27(4):293-307.

- Streu R, Hansen J, Abrahamse P, Alderman AK. Professional burnout among US plastic surgeons: results of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(3):346-350.

- Honkonen T, Ahola K, Pertovaara M, et al. The association between burnout and physical illness in the general population--results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(1):59-66.

- Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, Loong D. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:254.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996.

- Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress. 2005;19(3):192-207.

- Bianchi R, Boffy C, Hingray C, Truchot D, Laurent E. Comparative symptomatology of burnout and depression. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(6):782-787.

- Bianchi R, Schonfeld I S, Laurent E. Is burnout a depressive disorder? A re-examination with special focus on atypical depression. Intl J Stress Manag. 2014;21(4):307-324.

- Freudenberger HJ, North G. Women's burnout: How to spot it, how to reverse it, and how to prevent it. New York, New York: Doubleday, 1985.

- Abrams RM. Sleep deprivation. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(3):493-506.

- Williams D, Tricomi G, Gupta J, Janise A. Efficacy of burnout interventions in the medical education pipeline. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):47-54.

- Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: The personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

It sometimes seems that the pace of life, and its stresses, have spiraled out of control: There just never seems to be enough time to deal with all the directions in which we are pulled. This easily can lead to the exhaustion of physical or emotional strength or motivation, otherwise known as “burnout.” Burnout is physical or mental collapse caused by overwork or stress and we are all at risk of suffering it. Conflicting demands on our time, loss of control (real or imagined), and a diminishing sense of worth grind at us from every direction.

In general, having some control over schedule and hours worked is associated with reductions in burnout and improved job satisfaction.1 But this is not always the case. Well-intentioned efforts to reduce workload, such as the electronic medical records or physician order entry systems, have actually made the problem worse.2 The seeming level of control that comes with being the chair of an obstetrics and gynecology department does not necessarily reduce burnout rates,3 and neither does the perceived resilience of mental health professionals, who still report burnout rates that approach 25%.4

This article continues the focus on recalibrating work/life balance that began last month with “ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim,” by Lucia DiVenere, MA, and the peer-to-peer audiocast with Ms. DiVenere and myself titled “Is burnout on the rise and what are the signs ObGyns should be on the lookout for?” Here, I identify the causes and symptoms of burnout and provide specific tools to help you develop resilience.

Who is most at risk for burnout?

Estimates range from 40% to 75% of ObGyns currently suffer from professional burnout, making the lifetime risk a virtual certainty.1−3 The idea of professional burnout is not new, but wider recognition of the alarming rates of burnout is very current.4,5 A recent survey of gynecologic oncologists6 found that of those studied 30% scored high for emotional exhaustion, 10% high for depersonalization, and 11% low for personal accomplishment. Overall, 32% of physicians had scores indicating burnout. More worrisome was that 33% screened positive for depression, 13% had a history of suicidal ideation, 15% screened positive for alcohol abuse, and 34% reported impaired quality of life. Almost 40% would not encourage their children to enter medicine and more than 10% said that they would not enter medicine again if they had to do it over.

Residents and those at mid-career are particularly vulnerable,7 with resident burnout rates reported to be as high as 75%.8 Of surveyed residents in a 2012 study, 13% satisfied all 3 subscale scores for high burnout and greater than 50% had high levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion. Those with high levels of emotional exhaustion were less satisfied with their careers, regretted choosing obstetrics and gynecology, and had higher rates of depression—all findings consistent with older studies.

9,10

References

- Peckham C. Medscape Lifestyle Report 2016: Bias and Burnout. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2016/public/overview#page=1. Published January 13, 2016. Accessed July 7, 2016.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone, S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385.

- Martini S, Arfken CL, Churchill A, Balon R. Burnout comparison among residents in different medical specialties. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):240–242.

- Lee YY, Medford AR, Halim AS. Burnout in physicians. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2015;45(2):104–107.

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613.

- Rath KS, Huffman LB, Phillips GS, Carpenter KM, Fowler JM. Burnout and associated factors among members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):824.e1–e9.

- Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1358–1367.

- Govardhan LM, Pinelli V, Schnatz PF. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn Med. 2012;76(7):389–395.

- Becker JL, Milad MP, Klock SC. Burnout, depression, and career satisfaction: cross-sectional study of obstetrics and gynecology residents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(5):1444–1449.

- Castelo-Branco C, Figueras F, Eixarch E, et al. Stress symptoms and burnout in obstetric and gynaecology residents. BJOG. 2007;114(1):94–98

Why burnout occurs

Simply identifying ourselves as professionals and the same attributes that make us successful as physicians (type-A behavior, obsessive-compulsive commitment to our profession) put us at risk for professional burnout (see “Who is most at risk for burnout?”). Those predilections combine with the forces from the world in which we live and practice to increase this threat (TABLE 1). Conditions in which there are weak retention rates, high turnover, heavy workloads, and low staffing levels or staffing shortages increase the risk of burnout and, when burnout is present, are associated with a degraded quality of care.5

Does stress cause burnout?

Stress is often seen as the reason for burnout. Research shows that there is no single source of burnout,6 however, and a number of factors combine to cause this physical or mental collapse. Stress can be a positive or negative factor in our performance. Too little stress and we feel underutilized; too much stress and we collapse from the strain.

There is a middle ground where stress and expectations keep us focused and at peak productivity (FIGURE 1). The key is the balance between control and demand: When we have a greater level of control, we can handle high demands (FIGURE 2). It is when we lack that control that high demands result in what has been called “toxic stress,” and we collapse under the strain.

The impact of burnout

Burnout is associated with reduced performance and job satisfaction, increased rates of illness and absenteeism, accidents, premature retirement, and even premature death. Physically, stress induces the dry mouth, dilated pupils, and release of adrenalin and noradrenalin associated with the “fight-or-flight” reaction. The degree to which the physical, emotional, and professional symptoms are manifest depends on the depth or stage of burnout present (TABLE 2). Overall, burnout is associated with an increased risk for physical illness.7 Economically, the impact of physician burnout (for physicians practicing in Canada) has been estimated to be $213.1 million,8 which includes $185.2 million due to early retirement and $27.9 million due to reduced clinical hours.

“Do I have burnout?”

We all suffer from fatigue and have stress, but do we have burnout? With so many myths surrounding stress and burnout, it is sometimes hard to know where the truth lies. Some of those myths say that:

- you can leave your troubles at home

- mental stress does not affect physical performance

- stress is only for wimps

- stress and burnout are chemical imbalances that can be treated with medications

- stress is always bad

- burnout will get better if you just give it more time.

Maslach Burnout Inventory. The effective “gold standard” for diagnosing burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory,9 which operationalizes burnout as a 3-dimensional syndrome made up of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. Other diagnostic tools have been introduced10 but have not gained the wide acceptance of the Maslach Inventory. Some authors have argued that burnout and depression represent different, closely spaced points along a spectrum and that any effort to separate them may be artificial.11,12

The Maslach Burnout Inventory consists of a survey of 22 items; it requires a fee to take and is interpreted by a qualified individual. A simpler screening test consists of 10 questions (TABLE 3). If you answer “yes” to 5 or more of the questions, you probably have burnout. An even quicker test is to see, when you go on vacation, if your symptoms disappear. If so, you are not depressed; you have burnout. (If you cannot even go on vacation, then it is almost certain.)

12 stages of burnout. Psychologists Herbert Freudenberger and Gail North have theorized that the burnout process can be divided into 12 phases (TABLE 4).13 These stages are not necessarily sequential—some may be absent and others may present simultaneously. It is easy to see how these can represent stages in a potentially spiraling series of behaviors and changes that result in complete dysfunction. It is also easy to understand that the characteristics that are associated with success in medical school, clinical training, and practice, such as high expectations, placing the needs of others above our own, and a desire to prove oneself, virtually define the first 3 stages.

Approaches for burnout control and prevention

There are some simple steps we can take to reduce the risk of burnout or to reverse its effects. Because fatigue and stress are 2 of the greatest risk factors, reducing these is a good place to start.

Prioritize sleep. When it comes to fatigue, that one is easy: get some sleep. Physicians tend to sleep fewer hours than the general population and what we get is often not the type that is restful and restorative.14 Just reducing the number of hours worked is not enough, as a number of studies have found.15 The rest must result in relaxation.

e Stress reduction may seem a more difficult goal than getting more sleep. In reality, there are several simple approaches to use to reduce stress:

- Even though we all have busy clinical schedules, take short breaks to rest, sing, laugh, and exercise. Even breaks as short as 10 minutes can be effective.16

- Separate work from private life by taking a short break to resolve issues before heading home. Avoiding “baggage” or homework will go a long way to giving you the perspective you need from your time off. This may also mean that you have to delegate tasks, share chores, or get carry-out for dinner.

- Set meaningful and realistic goals for yourself professionally and personally. Do not expect or demand more than is possible. This will mean setting priorities and recognizing that some tasks may have to wait.

- Finally, do not forget to pay yourself with hobbies and activities that you enjoy.

Take action

If you feel the effects of burnout tugging at your coattails, you can reduce the effects, deal with the sources, and improve your attitude (TABLE 5). Rest and relaxation will go a long way to helping, but do not forget to take care of your physical well-being with a healthy diet, exercise, and health checkups. Deal with the sources of burnout by identifying the stressors, setting realistic priorities, and practicing good time management.

You also should lobby for changes that will increase your control and reduce unnecessary obstacles to completing your goals. Be your own best advocate. Look for the good and try to identify at least one instance during the day where your presence or acts made a difference. In the end, it is like Smokey the Bear says, “Only you can prevent burnout.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

It sometimes seems that the pace of life, and its stresses, have spiraled out of control: There just never seems to be enough time to deal with all the directions in which we are pulled. This easily can lead to the exhaustion of physical or emotional strength or motivation, otherwise known as “burnout.” Burnout is physical or mental collapse caused by overwork or stress and we are all at risk of suffering it. Conflicting demands on our time, loss of control (real or imagined), and a diminishing sense of worth grind at us from every direction.

In general, having some control over schedule and hours worked is associated with reductions in burnout and improved job satisfaction.1 But this is not always the case. Well-intentioned efforts to reduce workload, such as the electronic medical records or physician order entry systems, have actually made the problem worse.2 The seeming level of control that comes with being the chair of an obstetrics and gynecology department does not necessarily reduce burnout rates,3 and neither does the perceived resilience of mental health professionals, who still report burnout rates that approach 25%.4

This article continues the focus on recalibrating work/life balance that began last month with “ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim,” by Lucia DiVenere, MA, and the peer-to-peer audiocast with Ms. DiVenere and myself titled “Is burnout on the rise and what are the signs ObGyns should be on the lookout for?” Here, I identify the causes and symptoms of burnout and provide specific tools to help you develop resilience.

Who is most at risk for burnout?

Estimates range from 40% to 75% of ObGyns currently suffer from professional burnout, making the lifetime risk a virtual certainty.1−3 The idea of professional burnout is not new, but wider recognition of the alarming rates of burnout is very current.4,5 A recent survey of gynecologic oncologists6 found that of those studied 30% scored high for emotional exhaustion, 10% high for depersonalization, and 11% low for personal accomplishment. Overall, 32% of physicians had scores indicating burnout. More worrisome was that 33% screened positive for depression, 13% had a history of suicidal ideation, 15% screened positive for alcohol abuse, and 34% reported impaired quality of life. Almost 40% would not encourage their children to enter medicine and more than 10% said that they would not enter medicine again if they had to do it over.

Residents and those at mid-career are particularly vulnerable,7 with resident burnout rates reported to be as high as 75%.8 Of surveyed residents in a 2012 study, 13% satisfied all 3 subscale scores for high burnout and greater than 50% had high levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion. Those with high levels of emotional exhaustion were less satisfied with their careers, regretted choosing obstetrics and gynecology, and had higher rates of depression—all findings consistent with older studies.

9,10

References

- Peckham C. Medscape Lifestyle Report 2016: Bias and Burnout. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2016/public/overview#page=1. Published January 13, 2016. Accessed July 7, 2016.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone, S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385.

- Martini S, Arfken CL, Churchill A, Balon R. Burnout comparison among residents in different medical specialties. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):240–242.

- Lee YY, Medford AR, Halim AS. Burnout in physicians. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2015;45(2):104–107.

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613.

- Rath KS, Huffman LB, Phillips GS, Carpenter KM, Fowler JM. Burnout and associated factors among members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):824.e1–e9.

- Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1358–1367.

- Govardhan LM, Pinelli V, Schnatz PF. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn Med. 2012;76(7):389–395.

- Becker JL, Milad MP, Klock SC. Burnout, depression, and career satisfaction: cross-sectional study of obstetrics and gynecology residents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(5):1444–1449.

- Castelo-Branco C, Figueras F, Eixarch E, et al. Stress symptoms and burnout in obstetric and gynaecology residents. BJOG. 2007;114(1):94–98

Why burnout occurs

Simply identifying ourselves as professionals and the same attributes that make us successful as physicians (type-A behavior, obsessive-compulsive commitment to our profession) put us at risk for professional burnout (see “Who is most at risk for burnout?”). Those predilections combine with the forces from the world in which we live and practice to increase this threat (TABLE 1). Conditions in which there are weak retention rates, high turnover, heavy workloads, and low staffing levels or staffing shortages increase the risk of burnout and, when burnout is present, are associated with a degraded quality of care.5

Does stress cause burnout?

Stress is often seen as the reason for burnout. Research shows that there is no single source of burnout,6 however, and a number of factors combine to cause this physical or mental collapse. Stress can be a positive or negative factor in our performance. Too little stress and we feel underutilized; too much stress and we collapse from the strain.

There is a middle ground where stress and expectations keep us focused and at peak productivity (FIGURE 1). The key is the balance between control and demand: When we have a greater level of control, we can handle high demands (FIGURE 2). It is when we lack that control that high demands result in what has been called “toxic stress,” and we collapse under the strain.

The impact of burnout

Burnout is associated with reduced performance and job satisfaction, increased rates of illness and absenteeism, accidents, premature retirement, and even premature death. Physically, stress induces the dry mouth, dilated pupils, and release of adrenalin and noradrenalin associated with the “fight-or-flight” reaction. The degree to which the physical, emotional, and professional symptoms are manifest depends on the depth or stage of burnout present (TABLE 2). Overall, burnout is associated with an increased risk for physical illness.7 Economically, the impact of physician burnout (for physicians practicing in Canada) has been estimated to be $213.1 million,8 which includes $185.2 million due to early retirement and $27.9 million due to reduced clinical hours.

“Do I have burnout?”

We all suffer from fatigue and have stress, but do we have burnout? With so many myths surrounding stress and burnout, it is sometimes hard to know where the truth lies. Some of those myths say that:

- you can leave your troubles at home

- mental stress does not affect physical performance

- stress is only for wimps

- stress and burnout are chemical imbalances that can be treated with medications

- stress is always bad

- burnout will get better if you just give it more time.

Maslach Burnout Inventory. The effective “gold standard” for diagnosing burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory,9 which operationalizes burnout as a 3-dimensional syndrome made up of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. Other diagnostic tools have been introduced10 but have not gained the wide acceptance of the Maslach Inventory. Some authors have argued that burnout and depression represent different, closely spaced points along a spectrum and that any effort to separate them may be artificial.11,12

The Maslach Burnout Inventory consists of a survey of 22 items; it requires a fee to take and is interpreted by a qualified individual. A simpler screening test consists of 10 questions (TABLE 3). If you answer “yes” to 5 or more of the questions, you probably have burnout. An even quicker test is to see, when you go on vacation, if your symptoms disappear. If so, you are not depressed; you have burnout. (If you cannot even go on vacation, then it is almost certain.)

12 stages of burnout. Psychologists Herbert Freudenberger and Gail North have theorized that the burnout process can be divided into 12 phases (TABLE 4).13 These stages are not necessarily sequential—some may be absent and others may present simultaneously. It is easy to see how these can represent stages in a potentially spiraling series of behaviors and changes that result in complete dysfunction. It is also easy to understand that the characteristics that are associated with success in medical school, clinical training, and practice, such as high expectations, placing the needs of others above our own, and a desire to prove oneself, virtually define the first 3 stages.

Approaches for burnout control and prevention

There are some simple steps we can take to reduce the risk of burnout or to reverse its effects. Because fatigue and stress are 2 of the greatest risk factors, reducing these is a good place to start.

Prioritize sleep. When it comes to fatigue, that one is easy: get some sleep. Physicians tend to sleep fewer hours than the general population and what we get is often not the type that is restful and restorative.14 Just reducing the number of hours worked is not enough, as a number of studies have found.15 The rest must result in relaxation.

e Stress reduction may seem a more difficult goal than getting more sleep. In reality, there are several simple approaches to use to reduce stress:

- Even though we all have busy clinical schedules, take short breaks to rest, sing, laugh, and exercise. Even breaks as short as 10 minutes can be effective.16

- Separate work from private life by taking a short break to resolve issues before heading home. Avoiding “baggage” or homework will go a long way to giving you the perspective you need from your time off. This may also mean that you have to delegate tasks, share chores, or get carry-out for dinner.

- Set meaningful and realistic goals for yourself professionally and personally. Do not expect or demand more than is possible. This will mean setting priorities and recognizing that some tasks may have to wait.

- Finally, do not forget to pay yourself with hobbies and activities that you enjoy.

Take action

If you feel the effects of burnout tugging at your coattails, you can reduce the effects, deal with the sources, and improve your attitude (TABLE 5). Rest and relaxation will go a long way to helping, but do not forget to take care of your physical well-being with a healthy diet, exercise, and health checkups. Deal with the sources of burnout by identifying the stressors, setting realistic priorities, and practicing good time management.

You also should lobby for changes that will increase your control and reduce unnecessary obstacles to completing your goals. Be your own best advocate. Look for the good and try to identify at least one instance during the day where your presence or acts made a difference. In the end, it is like Smokey the Bear says, “Only you can prevent burnout.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Keeton K, Fenner DE, Johnson TR, Hayward RA. Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work-life balance, and burnout. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):949-955.

- Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836-848.

- Gabbe SG, Melville J, Mandel L, Walker E. Burnout in chairs of obstetrics and gynecology: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(4):601-612.

- Kok BC, Herrell RK, Grossman SH, West JC, Wilk JE. Prevalence of professional burnout among military mental health service providers. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(1):137-140.

- Humphries N, Morgan K, Conry MC, McGowan Y, Montgomery A, McGee H. Quality of care and health professional burnout: narrative literature review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2014;27(4):293-307.

- Streu R, Hansen J, Abrahamse P, Alderman AK. Professional burnout among US plastic surgeons: results of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(3):346-350.

- Honkonen T, Ahola K, Pertovaara M, et al. The association between burnout and physical illness in the general population--results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(1):59-66.

- Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, Loong D. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:254.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996.

- Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress. 2005;19(3):192-207.

- Bianchi R, Boffy C, Hingray C, Truchot D, Laurent E. Comparative symptomatology of burnout and depression. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(6):782-787.

- Bianchi R, Schonfeld I S, Laurent E. Is burnout a depressive disorder? A re-examination with special focus on atypical depression. Intl J Stress Manag. 2014;21(4):307-324.

- Freudenberger HJ, North G. Women's burnout: How to spot it, how to reverse it, and how to prevent it. New York, New York: Doubleday, 1985.

- Abrams RM. Sleep deprivation. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(3):493-506.

- Williams D, Tricomi G, Gupta J, Janise A. Efficacy of burnout interventions in the medical education pipeline. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):47-54.

- Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: The personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

- Keeton K, Fenner DE, Johnson TR, Hayward RA. Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work-life balance, and burnout. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):949-955.

- Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836-848.

- Gabbe SG, Melville J, Mandel L, Walker E. Burnout in chairs of obstetrics and gynecology: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(4):601-612.

- Kok BC, Herrell RK, Grossman SH, West JC, Wilk JE. Prevalence of professional burnout among military mental health service providers. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(1):137-140.

- Humphries N, Morgan K, Conry MC, McGowan Y, Montgomery A, McGee H. Quality of care and health professional burnout: narrative literature review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2014;27(4):293-307.

- Streu R, Hansen J, Abrahamse P, Alderman AK. Professional burnout among US plastic surgeons: results of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(3):346-350.

- Honkonen T, Ahola K, Pertovaara M, et al. The association between burnout and physical illness in the general population--results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(1):59-66.

- Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, Loong D. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:254.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996.

- Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress. 2005;19(3):192-207.

- Bianchi R, Boffy C, Hingray C, Truchot D, Laurent E. Comparative symptomatology of burnout and depression. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(6):782-787.

- Bianchi R, Schonfeld I S, Laurent E. Is burnout a depressive disorder? A re-examination with special focus on atypical depression. Intl J Stress Manag. 2014;21(4):307-324.

- Freudenberger HJ, North G. Women's burnout: How to spot it, how to reverse it, and how to prevent it. New York, New York: Doubleday, 1985.

- Abrams RM. Sleep deprivation. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(3):493-506.

- Williams D, Tricomi G, Gupta J, Janise A. Efficacy of burnout interventions in the medical education pipeline. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):47-54.

- Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: The personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

In this Article

- Symptoms by stage of burnout

- Tips to reduce stress and burnout

- Who is most at risk for burnout?