User login

Telemedicine (or telehealth) originated in the early 1900s, when radios were used to communicate medical advice to clinics aboard ships.1 According to the American Telemedicine Association, telemedicine is namely “the use of medical information exchanged from one site to another via electronic communications to improve a patient’s clinical health status.”2 These communications use 2-way video, email, smartphones, wireless tools, and other forms of telecommunications technology.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many ObGyns—encouraged and advised by professional organizations—began providing telemedicine services.3 The first reported case of COVID-19 was in late 2019; the use of telemedicine was 38 times higher in February 2021 than in February 2020,4 illustrating how many physicians quickly moved to telemedicine practices.

CASE Dr. TM’s telemedicine dream

Before COVID-19, Dr. TM (an ObGyn practi-tioner) practiced in-person medicine in his home state. With the onset of the pandemic, Dr. TM struggled to switch to primarily seeing patients online (generally using Zoom or Facebook Live), with 1 day per week in the office for essential in-person visits.

After several months, however, Dr. TM’s routine became very efficient. He could see many more patients in a shorter time than with the former, in-person system. Therefore, as staff left his practice, Dr. TM did not replace them and also laid off others. Ultimately, the practice had 1 full-time records/insurance secretary who worked from home and 1 part-time nurse who helped with the in-person day and answered some patient inquiries by email. In part as an effort to add new patients, Dr. TM built an engaging website through which his current patients could receive medical information and new patients could sign up.

In late 2022, Dr. TM offered a $100 credit to any current patient who referred a friend or family member who then became a patient. This promotion was surprisingly effective and resulted in an influx of new patients. For example, Patient Z (a long-time patient) received 3 credits for referring her 3 sisters who lived out of state and became telepatients: Patient D, who lived 200 hundred miles away; Patient E, who lived 50 miles away in the adjoining state; and Patient F, who lived 150 miles away. Patient D contacted Dr. TM because she thought she was pregnant and wanted prenatal care, Patient E thought she might have a sexually transmitted infection (STI) and wanted treatment, and Patient F wanted general care and was inquiring about a medical abortion. Dr. TM agreed to treat Patient D but required 1 in-person visit. After 1 brief telemedicine session each with Patients E and F, Dr. TM wrote prescriptions for them.

By 2023, Dr. TM was enthusiastic about telemedicine as a professional practice. However, problems would ensue.

Dos and don’ts of telemedicine2

- Do take the initiative and inform patients of the availability of telemedicine/telehealth services

- Do use the services of medical malpractice insurance companies with regard to telemedicine

- Do integrate telemedicine into practice protocols and account for their limitations

- Don’t assume there are blanket exemptions or waivers in the states where your patients are located

Medical considerations

Telemedicine is endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) as a vehicle for delivering prenatal and postpartum care.5 This represents an effort to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality,5 as well as expandaccess to care and address the deficit in primary care providers and services, especially in rural and underserved populations.5,6 For obstetrics, prenatal care is designed to optimize pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care, with a focus on nutrition and genetic consultation and patient education on pregnancy, childbearing, breastfeeding, and newborn care.7

Benefits of telemedicine include its convenience for patients and providers, its efficiency and lower costs for providers (and hopefully patients, as well), and the potential improved access to care for patients.8 It is estimated that if a woman inititates obstetric care at 6 weeks, over the course of the 40-week gestation period, 15 prenatal visits will occur.9 Ultimately, the number of visits is determined based on the specifics of the pregnancy. With telemedicine, clinicians can provide those consultations, and information related to: ultrasonography, fetal echocardiography, and postpartum care services remotely.10 Using telemedicine may reduce missed visits, and remote monitoring may improve the quality of care.11

Barriers to telemedicine care include technical limitations, time constraints, and patient concerns of telehealth (visits). Technical limitations include the lack of a high speed internet connection and/or a smart device and the initial technical set-up–related problems,12 which affect providers as well as patients. Time constraints primarly refer to the ObGyn practice’s lack of time to establish telehealth services.13 Other challenges include integrating translation services, billing-related problems,10 and reimbursement and licensing barriers.14

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, obstetrics led the way in telemedicine with the development of the OB Nest model. Designed to replace in-person obstetrics care visits with telehealth,15 it includes home management tools such as blood pressure cuffs, cardiotocography, scales for weight checks, and Doppler ultrasounds.10 Patients can be instructed to measure fundal height and receive medications by mail. Anesthesia consultation can occur via this venue by having the patient complete a questionnaire prior to arriving at the labor and delivery unit.16

Legal considerations

With the COVID-19 pandemic, temporary changes were made to encourage the rapid adoption of telemedicine, including changes to licensing laws, certain prescription requirements, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy-security regulations, and reimbursement rules that required in-person visits. Thus, many ObGyns started using telemedicine during this rarified period, in which the rules appeared to be few and far between, with limited enforcement of the law and professional obligations.17 However, now that many of the legal rules that were suspended or ignored have been (or are being) reimposed and enforced, it is important for providers to become familiar with the legal issues involved in practicing telemedicine.

First, where is the patient? When discussing the legal issues of telemedicine, it is important to remember that many legal rules for medical care (ie, liability, informed consent, and licensing) vary from state to state. If the patient resides in a different state (“foreign” state) from the physician’s practice location (the physician’s “home” state), the care is considered delivered in the state where the patient is located. Thus, the patient’s location generally establishes the law covering the telemedicine transaction. In the following discussion, the rules refer to the law and professional obligations, with commentary on some key legal issues that are relevant to ObGyn telemedicine.

Continue to: Reinforcing the rules...

Reinforcing the rules

Licensing

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government and almost all states temporarily modified the licensing requirement to allow telemedicine based on an existing medical license in any state—disregarding the “where is the patient” rule. As those rules begin to lapse or change with the official end of the pandemic declared by President Biden as May 2023,17 the rules under which a physician began telemedicine interstate practice in 2020 also may be changing.

Simply put, “The same standards for licensure apply to health care providers regardless of whether care is delivered in-person or virtually through telehealth services.”18 When a physician is engaged in telemedicine treatment of a patient in the physician’s home state, there is generally no licensing issue. Telemedicine generally does not require a separate specific license.19 However, when the patient is in another state (a “foreign” state), there can be a substantial licensing issue.20 Ordinarily, to provide that treatment, the physician must, in some manner, be approved to practice in the patient’s state. That may occur, for example, in the following ways: (1) the physician may hold an additional regular license in the patient’s state, which allows practice there, or (2) the physician may have received permission for “temporary practice” in another state.

Many states (often adjoining states) have formal agreements with other states that allow telemedicine practice by providers in each other’s states. There also are “compacts”, or agreements that enable providers in any of the participating states to practice in the other associated states without a separate license.18 Although several websites provide information about compact licensing and the like, clinicians should not rely on simple lists or maps. Individual states may have special provisions about applying their laws to out-of-state “compact” physicians. In addition, under the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact, “physicians have to pay licensing fees and satisfy the requirements of each medical board in the states where they wish to practice.”21

Consequences. Practicing telemedicine with a patient in a state where the physician does not have a license is generally a crime. Furthermore, it may be the basis for license discipline in the physician’s home state and result in a report to the National Practi-tioner Databank.22 In addition, reimbursement often depends on the practitioner being licensed, and the absence of a license may be a basis for denying payment for services.23 Finally, malpractice insurance generally is limited to licensed practice. Thus, the insurer may decline to defend the unlicensed clinician against a malpractice claim or pay any damages.

Prescribing privileges

Prescribing privileges usually are connected to licensing, so as the rules for licensing change postpandemic, so do the rules for prescribing. In most cases, the physician must have a license in the state where care is given to prescribe medication—which in telemedicine, as noted, typically means the state where the patient is located. Exceptions vary by state, but in general, if a physician does not have a license to provide care, the physician is unlikely to be authorized to prescribe medication.24 Failure to abide by the applicable state rules may result in civil and even criminal liability for illegal prescribing activity.

In addition, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA, which enforces laws concerning controlled substances) also regulate the prescription and sale of pharmaceuticals.25 There are state and federal limits on the ability of clinicians to order controlled substances without an in-person visit. The Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act, for example, sets limits on controlled substance prescriptions without an in-person examination.26 Federal law was modified due to COVID-19 to permit prescribing of many controlled substances by telemedicine if there is synchronous audio and visual examination of the patient. Physicians who write such prescriptions also are required to have a DEA registration in the patient’s state. This is an essential consideration for physicians considering interstate telemedicine practice.27

HIPAA and privacy

Governments waived some of the legal requirements related to health information during the pandemic, but those waivers either have expired or will do so soon. Federal and state laws regarding privacy and security—notably including HIPAA—apply to telemedicine and are of particular concern given the considerable amount of communication of protected health information with telemedicine.

HIPAA security rules essentially require making sure health information cannot be hacked or intercepted. Audio-only telemedicine by landline (not cell) is acceptable under the security rules, but almost all other remote communication requires secure communications.28

Clinicians also need to adhere to the more usual HIPAA privacy rules when practicingtelehealth. State laws protecting patient privacy vary and may be more stringent than HIPAA, so clinicians also must know the requirements in any state where they practice—whether in office or telemedicine.29

Making sure telemedicine practices are consistent with these security and privacy rules often requires particular technical expertise that is outside the realm of most practicing clinicians. However, without modification, the pre-telemedicine technology of many medical offices likely is insufficient for the full range of telemedicine services.30

Reimbursement and fraud

Before COVID-19, Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement for telemedicine was limited. Government decisions to substantially broaden those reimbursement rules (at least temporarily) provided a substantial boost to telemedicine early in the pandemic.23 Federal regulations and statutes also expanded telemedicine reimbursement for various services. Some will end shortly after the health emergency, and others will be permanent. Parts of that will not be sorted out for several years, so it will likely be a changing landscape for reimbursement.

Continue to: Rules that are evolving...

Rules that are evolving

Informed consent

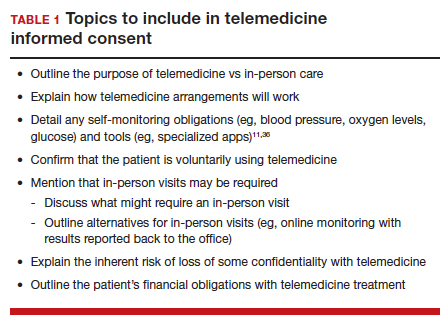

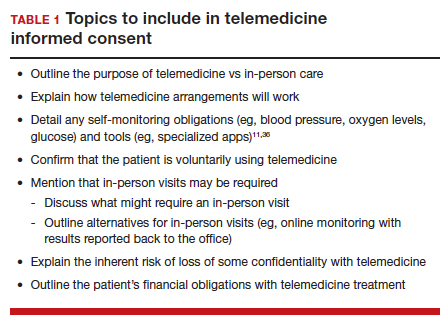

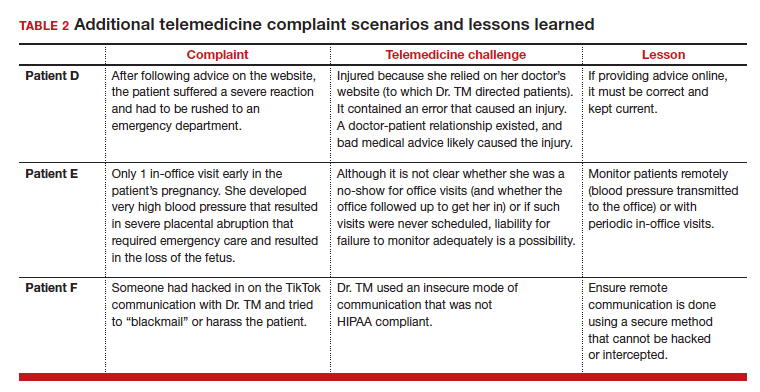

The ethical and legal obligations to obtain informed consent are present in telemedicineas well as in-person care, with the same basic requirements regarding risks, benefits, alternative care, etc.32 However, with telemedicine, information related to remote care should be included and is outlined in TABLE 1.

Certain states may have somewhat unique informed consent requirements—especially for reproductive care, including abortion.34 Therefore, it is important for clinicians to ensure their consent process and forms comply with any legal jurisdiction in which a patient is located.

Medical malpractice

The basics of medical malpractice (or negligence) are the same in telemedicine as in in-person care: duty, breach of duty, and injury caused by the breach. That is, there may be liability when a medical professional breaches the duty of care, causing the patient’s injury. The physician’s duty is defined by the quality of care that the profession (specialty) accepts as reasonably good. This is defined by the opinions of physicians within the specialty and formal statements from professional organizations, including ACOG.3

Maintaining the standard of care and quality. The use of telemedicine is not an excuse to lower the quality of health care. There are some circumstances for which it is medically better to have an in-person visit. In these instances, the provider should recommend the appropriate care, even if telemedicine would be more convenient for the provider and staff.35

If the patient insists and telemedicine might result in less than optimal care, the reasons for using a remote visit should be clearly documented contemporaneously with the decision. Furthermore, when the limitations of being unable to physically examine the patient result in less information than is needed for the patient’s care, the provider must find alternatives to make up for the information gap.11,36 It also may be necessary to inform patients about how to maximize telemedicine care.37 At the beginning of telemedicine care the provider should include information about the nature and limits of telehealth, and the patient’s responsibilities. (See TABLE 1) Throughout treatment of the patient, that information should be updated by the provider. That, of course, is particularly important for patients who have not previously used telemedice services.

Malpractice rules vary by state. Many states have special rules regarding malpractice cases. These differences in malpractice standards and regulations “can be problematic for physicians who use telemedicine services to provide care outside the state in which they practice.”38 Caps on noneconomic damages are an example. Those state rules would apply to telemedicine in the patient’s state.

Malpractice insurance

Malpractice insurance now commonly includes telemedicine legally practiced within the physician’s home state. Practitioners who treat patients in foreign states should carefully examine their malpractice insurance policies to confirm that the coverage extends to practice in those states.39 Malpractice carriers may require notification by a covered physician who routinely provides services to patients in another state.3

Keep in mind, malpractice insurance generally does not cover the practice of medicine that is illegal. Practicing telemedicine in a foreign state, where the physician or other provider does not have a license and where that state does not otherwise permit the practice, is illegal. Most likely, the physician’s malpractice insurance will not cover claims that arise from this illegal practice in a foreign state or provide defense for malpractice claims, including frivolous lawsuits. Thus, the physician will pay out of pocket for the costs of a defense attorney.

Telemedicine treatment of minors

Children and adolescents present special legal issues for ObGyn care, which may become more complicated with telemedicine. Historically, parents are responsible for minors (those aged <18 years): they consent to medical treatment, are responsible for paying for it, and have the right to receive information about treatment.

Over the years, though, many states have made exceptions to these principles, especially with regard to contraception and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases.40 For abortion, in particular, there is considerable variation among the states in parental consent and notification.41 The Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health42 may (depending on the state) be followed with more stringent limitations on adolescent consent to abortions, including medical abortions.43

Use of telehealth does not change any obligations regarding adolescent consent or parental notification. Because those differ considerably among states, it is important for all practitioners to know their states’ requirements and keep reasonably complete records demonstrating their compliance with state law.

Abortion

The most heated current controversy about telemedicine involves abortion—specifically medical abortion, which is the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol.44,45 The FDA approved the combination in 2000. Almost immediately, many states required in-person visits with a certified clinician to receive a prescription for mifepristone and misoprostol, and eventually, the FDA adopted similar requirements.46 However, during the pandemic from 2021 to 2022, the FDA permitted telemedicine prescriptions. Several states still require in-person physician visits, although the constitutionality of those requirements has not been established.47

With the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health in 2022,42 disagreements have ensued about the degree to which states may regulate the prescription of FDA-approved medical abortion drugs. Thorny constitutional issues exist in the plans of both abortion opponents and proponents in the battle over medical abortion in antiabortion states. It may be that federal drug law preempts state laws limiting access to FDA-approved drugs. On the other hand, it may be that states can make it a crime within the state to possess or provide abortion-inducing drugs. Courts will probably take years to resolve the many tangled legal questions.48

Thus, while the pandemic telemedicine rules may have advanced access to abortion,34 there may be some pending downsides.49 States that prohibit abortion will likely include prohibitions on medical abortions. In addition, they may prohibit anyone in the state (including pharmacies) from selling, possessing, or obtaining any drug used for causing or inducing an abortion.50 If, for constitutional reasons, they cannot press criminal charges or undertake licensing discipline for prescribing abortion, some states will likely withdraw from telehealth licensing compacts to avoid out-of-state prescriptions. This area of telemedicine has considerable uncertainty.

Continue to: CASE Conclusion...

CASE Conclusion

Patient concerns come to the fore

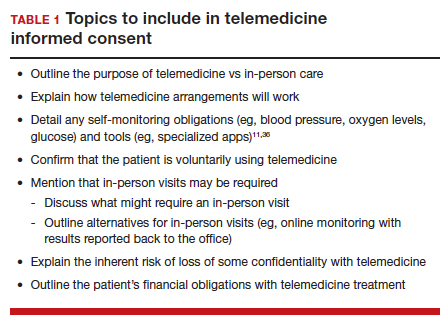

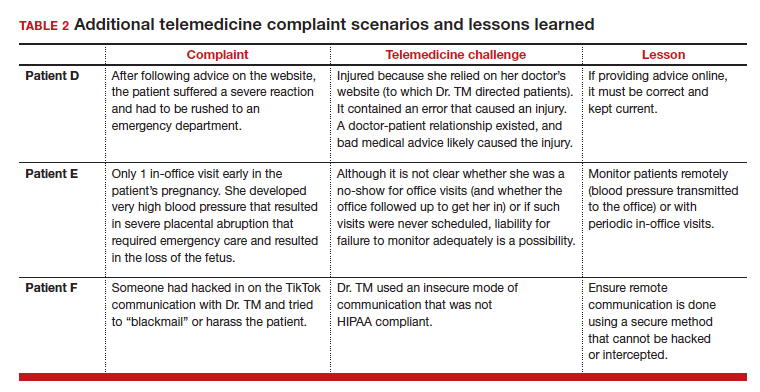

By 2023, Dr. TM started receiving bad news. Patient D called complaining that after following the advice on the website, she suffered a severe reaction and had to be rushed to an emergency department. Patient E (who had only 1 in-office visit early in her pregnancy) notified the office that she developed very high blood pressure that resulted in severe placental abruption, requiring emergency care and resulting in the loss of the fetus. Patient F complained that someone hacked the TikTok direct message communication with Dr. TM and tried to “blackmail” or harass her.

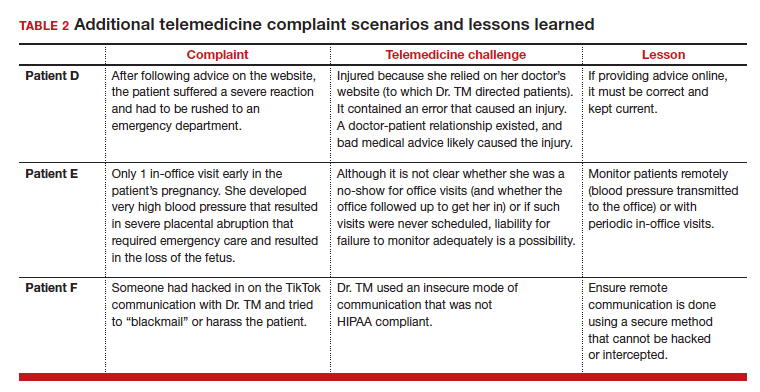

Discussion. Patients D, E, and F represent potential problems of telemedicine practice. Patient D was injured because she relied on her doctor’s website (to which Dr. TM directed patients). It contained an error that caused an injury. A doctor-patient relationship existed, and bad medical advice likely caused the injury. Physicians providing advice online must ensure the advice is correct and kept current.

Patient E demonstrates the importance of monitoring patients remotely (blood pressure transmitted to the office) or with periodic in-office visits. It is not clear whether she was a no-show for office visits (and whether the office followed up on any missed appointments) or if such visits were never scheduled. Liability for failure to monitor adequately is a possibility.

Patient F’s seemingly minor complaint could be a potential problem. Dr. TM used an insecure mode of communication. Although some HIPAA security regulations were modified or suspended during the pandemic, using such an unsecure platform is problematic, especially if temporary HIPAA rules expired. The outcome of the complaint is in doubt.

(See TABLE 2 for additional comments on patients D, E, and F.)

Out-of-state practice

Dr. TM treated 3 out-of-state residents (D, E, and F) via telemedicine. Recently Dr. TM received a complaint from the State Medical Licensure Board for practicing medicine without a license (Patient D), followed by similar charges from Patient E’s and Patient F’s state licensing boards. He has received a licensing inquiry from his home state board about those claims of illegal practice in other states and incompetent treatment.

Patient D’s pregnancy did not go well. The 1 in-person visit did not occur and she has filed a malpractice suit against Dr. TM. Patient E is threatening a malpractice case because the STI was not appropriately diagnosed and had advanced before another physician treated it.

In addition, a private citizen in Patient F’s state has filed suit against Dr. TM for abetting an illegal abortion (for Patient F).

Discussion. Patients D, E, and F illustrate the risk of even incidental out-of-state practice. The medical board inquiries arose from anonymous tips to all 4 states reporting Dr. TM was “practicing medicine without a license.” Patient E’s home state did have a licensing compact with the adjoining state (ie, Dr. TM’s home state). However, it required physicians to register and file an annual report, which Dr. TM had not done. The other 2 states did not have compacts with Dr. TM’s home state. Thus, he was illegally practicing medicine and would be subject to penalties. His home state also might impose license discipline based on his illegal practice in other states.

Continue to: What’s the verdict?...

What’s the verdict?

Dr. TM’s malpractice carrier is refusing to defend the claims of medical malpractice threatened by Patients D, E, and F. The company first notes that the terms of the malpractice policy specifically exclude the illegal practice of medicine. Furthermore, when a physician legally practices in another state, the policy requires a written notice to the insurance carrier of such practice. Dr. TM will likely have to engage and pay for a malpractice attorney for these cases. Because the claims are filed in 3 different states, more than a home-state attorney will likely be involved in the defense of these cases. Dr. TM will need to pay the attorneys and any damages from a settlement or trial.

Malpractice claims. Patient D claims that the doctor essentially abandoned her by never reaching out to her or arranging an in-person visit. Dr. TM claims the patient was responsible for scheduling the in-person visit. Patient E claims it was malpractice not to determine the specific nature of the STI and to do follow-up testing to determine that it was cured. All patients claim there was no genuine informed consent to the telemedicine. An attorney has warned Dr. TM that it is “not going to look good to the jury” that he was practicing without a license in the state and suggests he settle the cases quickly by paying damages.

Abortion-related claims. Patient F presents a different set of problems. Dr. TM’s home state is “proabortion.” Patient F’s home state is strongly “antiabortion,” making it a felony to participate in, assist, or facilitate an abortion (including medical abortion). Criminal charges have been filed against Dr. TM for the illegal practice of medicine, for aiding and facilitating an abortion, and for failure to notify a parent that a minor is seeking an abortion. For now, Dr. TM’s state is refusing to extradite on the abortion charge. Still, the patient’s state insists that it do so on the illegal practice of medicine charges and new charges of insurance fraud and failure to report suspected sexual abuse of a child. (Under the patient’s state law, anyone having sex with Patient F would have engaged in sexual abuse or “statutory rape,” so the state insists that the fact she was pregnant proves someone had sex with her.)

Patient F’s state also has a statute that allows private citizens to file civil claims against anyone procuring or assisting with an abortion (a successful private citizen can receive a minimum of $10,000 from the defendant). Several citizens from the patient’s state have already filed claims against Dr. TM in his state courts. Only one of them, probably the first to file, could succeed. Courts in the state have issued subpoenas and ordered Dr. TM to appear and reply to the civil suits. If he does not respond, there will be a default judgment.

Dr. TM’s attorney tells him that these lawsuits will not settle and will take a long time to defend and resolve. That will be expensive.

Billing and fraud. Dr. TM’s office recently received a series of notices from private health insurers stating they are investigating previously made payments as being fraudulent (unlicensed). They will not pay any new claims pending the investigation. On behalf of Medicare-Medicaid and other federal programs, the US Attorney’s office has notified Dr. TM that it has opened an investigation into fraudulent federal payments. F’s home state also is filing a (criminal) insurance fraud case, although the basis for it is unclear. (Dr. TM’s attorney believes it might be to increase pressure on the physician’s state to extradite Dr. TM for Patient F’s case.)

In addition, a disgruntled former employee of Dr. TM has filed a federal FCA case against him for filing inflated claims with various federally funded programs. The employee also made whistleblower calls to insurance companies and some state-funded medical programs. A forensic accounting investigation by Dr. TM’s accountant confirmed a pattern of very sloppy records and recurring billing for televisits that did not occur. Dr. TM believes that this was the act of one of the temporary assistants he hired in a pinch, who did not understand the system and just guessed when filing some insurance claims.

During the investigation, the federal and state attorneys are looking into a possible violation of state and federal Anti-Kickback Statutes. This is based on the original offer of a $100 credit for referrals to Dr. TM’s telemedicine practice.

The attorneys are concerned that other legal problems may present themselves. They are thoroughly reviewing Dr. TM’s practice and making several critical but somewhat modest changes to his practice. They also have insisted that Dr. TM have appropriate staff to handle the details of the practice and billing.

Conclusions

Telemedicine presents notable legal challenges to medical practice. As the pandemic status ends, ObGyn physicians practicing telemedicine need to be aware of the rules and how they are changing. For those physicians who want to continue or start a telemedicine practice, securing legal and technical support to ensure your operations are inline with the legal requirements can minimize any risk of legal troubles in the future. ●

A physician in State A, where abortion is legal, has a telemedicine patient in State B, where it is illegal to assist, provide, or procure an abortion. If the physician prescribes a medical abortion, he would violate the law of State B by using telemedicine to help the patient (located in State B) obtain an abortion. This could result in criminal charges against the prescribing physician.

- Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. The Role of Telehealth in an Evolving Health Care Environment: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press: 2012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207145/. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Bruhn HK. Telemedicine: dos and don’ts to mitigate liability risk. J APPOS. 2020;24:195-196. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos. 2020.07.002

- Implementing telehealth in practice: ACOG Committee Opinion Summary, number 798. Obstet Gynecol. 2020; 2135:493-494. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003672

- Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, et al. Telehealth: a quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? McKinsey & Company. July 9, 2021. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights /telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality

- Stanley AY, Wallace JB. Telehealth to improve perinatal care access. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2022;47:281-287. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000841

- Warshaw R. Health disparities affect millions in rural US communities. Association of American Medical Colleges. Published October 31, 2017. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/health-disparities -affect-millions-rural-us-communities

- Almuslin H, AlDossary S. Models of incorporating telehealth into obstetric care during the COVID-19 pandemic, its benefits and barriers: a scoping review. Telemed J E Health. 2022;28:24-38. doi:10.1089/tmj.2020.0553

- Gold AE, Gilbert A, McMichael BJ. Socially distant health care. Tul L Rev. 2021;96:423-468. https://scholarship .law.ua.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1713&context =fac_articles. Accessed March 4, 2023.

- Zolotor AJ, Carlough MC. Update on prenatal care. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:199-208.

- Odibo IN, Wendel PJ, Magann EF. Telemedicine in obstetrics. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56:422-433. doi:10.1097/ GRF.0b013e318290fef0

- Shmerling A, Hoss M, Malam N, et al. Prenatal care via telehealth. Prim Care. 2022;49:609-619. doi:10.1016/j. pop.2022.05.002

- Madden N, Emeruwa UN, Friedman AM, et al. Telehealth uptake into prenatal care and provider attitudes during COVID-19 pandemic in New York City: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:1005-1014. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1712939

- Dosaj A, Thiyagarajan D, Ter Haar C, et al. Rapid implementation of telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed J E Health. 2020;27:116-120. doi:10.1089/ tmj.2020.0219

- Lurie N, Carr B. The role of telehealth in the medical response to disasters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;187:745-746. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1314

- Tobah YSB, LeBlanc A, Branda E, et al. Randomized comparison of a reduced-visit prenatal care model enhanced with remote monitoring. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:638-e1-638.e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.034

- Vivanti AJ, Deruelle P, Piccone O, et al. Follow-up for pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: French national authority for health recommendations. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020;49:101804. doi:10.1016/j. jogoh.2020.101804

- Ellimoottil C. Takeaways from 2 key studies on interstate telehealth use among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3:e223020-E223020. doi:10.1001/ jamahealthforum.2022.3020

- Harris J, Hartnett T, Hoagland GW, et al. What eliminating barriers to interstate telehealth taught us during the pandemic. Bipartisan Policy Center. Published November 2021. Accessed March 9, 2023. https://bipartisanpolicy .org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/BPC -Health-Licensure-Brief_WEB.pdf.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Cross-state licensing. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.cchpca.org/topic /cross-state-licensing-professional-requirements.

- US Department of Health & Human Services. Telehealth. Getting started with licensure. Published February 3, 2023. Accessed February 27, 2023. https://telehealth.hhs.gov /licensure/getting-started-licensure/

- US Department of Health & Human Services. Telehealth. Licensure. Accessed February 27, 2023. https://telehealth .hhs.gov/licensure

- US Department of Health & Human Services. National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) code lists. Published December 2022. Accessed March 9, 2023. https://www.npdb .hrsa.gov/software/CodeLists.pdf

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. COVID-19 FAQs for obstetrician-gynecologists, telehealth. 2020. Accessed March 5, 2023. https://www.acog.org /clinical-information/physician-faqs/covid-19-faqs-for -ob-gyns-telehealth

- Gorman RK. Prescribing medication through the practice of telemedicine: a comparative analysis of federal and state online prescribing policies, and policy considerations for the future. S Cal Interdisc Law J. 2020;30:739-769. https://gould .usc.edu/why/students/orgs/ilj/assets/docs/30-3-Gorman. pdf. Accessed March 10, 2023.

- Farringer DR. A telehealth explosion: using lessons from the pandemic to shape the future of telehealth regulation. Tex A&M Law Rev. 2021;9:1-47. https://scholarship.law.tamu. edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1232&context=lawreview. Accessed February 28, 2023.

- Sterba KR, Johnson EE, Douglas E, et al. Implementation of a women’s reproductive behavioral health telemedicine program: a qualitative study of barriers and facilitators in obstetric and pediatric clinics. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:167, 1-10. doi:10.1186/s12884-023-05463-2.

- US Department of Justice. COVID-19 FAQ (telemedicine). https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/faq/coronavirus_faq .htm#TELE_FAQ2. Accessed March 13, 2023.

- US Department of Health & Human Services. Guidance on how the HIPAA rules permit covered health care providers and health plans to use remote communication technologies for audio-only telehealth. Published June 13, 2022. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy /guidance/hipaa-audio-telehealth/index.html.

- Gray JME. HIPAA, telehealth, and the treatment of mental illness in a post-COVID world. Okla City Uni Law Rev. 2021;46:1-26. https://law.okcu.edu/wp-content /uploads/2022/04/J-Michael-E-Gray-HIPAA-Telehealth -and-Treament.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Kurzweil C. Telemental health care and data privacy: current HIPAA privacy pitfalls and a proposed solution. Ann Health L Adv Dir. 2022;31:165.

- US Department of Health & Human Services and US Department of Justice. Health care fraud and abuse control program FY 2020: annual report. July 2021. Accessed March 9, 2023. https://oig.hhs.gov/publications/docs/hcfac /FY2020-hcfac.pdf

- Copeland KB. Telemedicine scams. Iowa Law Rev. 2022: 108:69-126. https://ilr.law.uiowa.edu/sites/ilr.law.uiowa.edu /files/2023-01/A2_Copeland.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2023.

- Solimini R, Busardò FP, Gibelli F, et al. Ethical and legal challenges of telemedicine in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:13141324. doi:10.3390/medicina57121314

- Reed A. COVID: a silver linings playbook. mobilizing pandemic era success stories to advance reproductive justice. Berkeley J Gender Law Justice. 2022;37:221-266. https://lawcat.berkeley.edu/record/1237158/files/16%20 Reed_final.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2023.

- Women’s Preventive Services Initiative and The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. FAQ for telehealth services. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://www .womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/WPSI -Telehealth-FAQ.pdf

- Warren L, Chen KT. Telehealth apps in ObGyn practice. OBG Manag. 2022;34:46-47. doi:10.12788/obgm.0178

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 10 telehealth tips for an Ob-Gyn visit. 2020. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://www.acog.org/womens-health /infographics/10-telehealth-tips-for-an-ob-gyn-visit

- Wolf TD. Telemedicine and malpractice: creating uniformity at the national level. Wm Mary Law Rev. 2019;61:15051536. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi ?article=3862&context=wmlr. Accessed March 11, 2023.

- Cahan E. Lawsuits, reimbursement, and liability insurance— facing the realities of a post-Roe era. JAMA. 2022;328:515517. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.9193

- Heinrich L, Hernandez AK, Laurie AR. Telehealth considerations for the adolescent patient. Prim Care. 2022;49:597-607. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2022.04.006

- Guttmacher Institute. An overview of consent to reproductive health services by young people. Published March 1, 2023. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.guttmacher.org /state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law.

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health. No. 19–1392. June 24, 2022. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.supremecourt .gov/opinions/21pdf/19-1392_6j37.pdf

- Lindgren Y. Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health and the post-Roe landscape. J Am Acad Matrimonial Law. 2022;35:235283. https://www.aaml.org/wp-content/uploads/MAT110-1 .pdf. Accessed March 11, 2023.

- Mohiuddin H. The use of telemedicine during a pandemic to provide access to medication abortion. Hous J Health Law Policy. 2021;21:483-525. https://houstonhealthlaw. scholasticahq.com/article/34611.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2023.

- Rebouché R. The public health turn in reproductive rights. Wash & Lee Law Rev. 2021;78:1355-1432. https:// scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/cgi/viewcontent .cgi?article=4743&context=wlulr. Accessed March 10, 2023.

- Fliegel R. Access to medication abortion: now more important than ever. Am J Law Med. 2022;48:286-304. doi:10.1017/amj.2022.24

- Guttmacher Institute. Medication abortion. March 1, 2023. Accessed April 1, 2023 https://www.guttmacher.org /state-policy/explore/medication-abortion#:~:text=In%20 January%202023%2C%20the%20FDA,order%20to%20 dispense%20the%20pills

- Cohen DS, Donley G, Rebouché R. The new abortion battleground. Columbia Law Rev. 2023;123:1-100. https:// columbialawreview.org/content/the-new-abortion -battleground/. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- Hunt SA. Call me, beep me, if you want to reach me: utilizing telemedicine to expand abortion access. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2023;76:323-359. Accessed March 10, 2023. https:// vanderbiltlawreview.org/lawreview/wp-content/uploads /sites/278/2023/01/Call-Me-Beep-Me-If-You-Want-toReach-Me-Utilizing-Telemedicine-to-Expand-AbortionAccess.pdf

- Gleckel JA, Wulkan SL. Abortion and telemedicine: looking beyond COVID-19 and the shadow docket. UC Davis Law Rev Online. 2020;54:105-121. https://lawreview.law.ucdavis. edu/online/54/files/54-online-Gleckel_Wulkan.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2023.

Telemedicine (or telehealth) originated in the early 1900s, when radios were used to communicate medical advice to clinics aboard ships.1 According to the American Telemedicine Association, telemedicine is namely “the use of medical information exchanged from one site to another via electronic communications to improve a patient’s clinical health status.”2 These communications use 2-way video, email, smartphones, wireless tools, and other forms of telecommunications technology.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many ObGyns—encouraged and advised by professional organizations—began providing telemedicine services.3 The first reported case of COVID-19 was in late 2019; the use of telemedicine was 38 times higher in February 2021 than in February 2020,4 illustrating how many physicians quickly moved to telemedicine practices.

CASE Dr. TM’s telemedicine dream

Before COVID-19, Dr. TM (an ObGyn practi-tioner) practiced in-person medicine in his home state. With the onset of the pandemic, Dr. TM struggled to switch to primarily seeing patients online (generally using Zoom or Facebook Live), with 1 day per week in the office for essential in-person visits.

After several months, however, Dr. TM’s routine became very efficient. He could see many more patients in a shorter time than with the former, in-person system. Therefore, as staff left his practice, Dr. TM did not replace them and also laid off others. Ultimately, the practice had 1 full-time records/insurance secretary who worked from home and 1 part-time nurse who helped with the in-person day and answered some patient inquiries by email. In part as an effort to add new patients, Dr. TM built an engaging website through which his current patients could receive medical information and new patients could sign up.

In late 2022, Dr. TM offered a $100 credit to any current patient who referred a friend or family member who then became a patient. This promotion was surprisingly effective and resulted in an influx of new patients. For example, Patient Z (a long-time patient) received 3 credits for referring her 3 sisters who lived out of state and became telepatients: Patient D, who lived 200 hundred miles away; Patient E, who lived 50 miles away in the adjoining state; and Patient F, who lived 150 miles away. Patient D contacted Dr. TM because she thought she was pregnant and wanted prenatal care, Patient E thought she might have a sexually transmitted infection (STI) and wanted treatment, and Patient F wanted general care and was inquiring about a medical abortion. Dr. TM agreed to treat Patient D but required 1 in-person visit. After 1 brief telemedicine session each with Patients E and F, Dr. TM wrote prescriptions for them.

By 2023, Dr. TM was enthusiastic about telemedicine as a professional practice. However, problems would ensue.

Dos and don’ts of telemedicine2

- Do take the initiative and inform patients of the availability of telemedicine/telehealth services

- Do use the services of medical malpractice insurance companies with regard to telemedicine

- Do integrate telemedicine into practice protocols and account for their limitations

- Don’t assume there are blanket exemptions or waivers in the states where your patients are located

Medical considerations

Telemedicine is endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) as a vehicle for delivering prenatal and postpartum care.5 This represents an effort to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality,5 as well as expandaccess to care and address the deficit in primary care providers and services, especially in rural and underserved populations.5,6 For obstetrics, prenatal care is designed to optimize pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care, with a focus on nutrition and genetic consultation and patient education on pregnancy, childbearing, breastfeeding, and newborn care.7

Benefits of telemedicine include its convenience for patients and providers, its efficiency and lower costs for providers (and hopefully patients, as well), and the potential improved access to care for patients.8 It is estimated that if a woman inititates obstetric care at 6 weeks, over the course of the 40-week gestation period, 15 prenatal visits will occur.9 Ultimately, the number of visits is determined based on the specifics of the pregnancy. With telemedicine, clinicians can provide those consultations, and information related to: ultrasonography, fetal echocardiography, and postpartum care services remotely.10 Using telemedicine may reduce missed visits, and remote monitoring may improve the quality of care.11

Barriers to telemedicine care include technical limitations, time constraints, and patient concerns of telehealth (visits). Technical limitations include the lack of a high speed internet connection and/or a smart device and the initial technical set-up–related problems,12 which affect providers as well as patients. Time constraints primarly refer to the ObGyn practice’s lack of time to establish telehealth services.13 Other challenges include integrating translation services, billing-related problems,10 and reimbursement and licensing barriers.14

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, obstetrics led the way in telemedicine with the development of the OB Nest model. Designed to replace in-person obstetrics care visits with telehealth,15 it includes home management tools such as blood pressure cuffs, cardiotocography, scales for weight checks, and Doppler ultrasounds.10 Patients can be instructed to measure fundal height and receive medications by mail. Anesthesia consultation can occur via this venue by having the patient complete a questionnaire prior to arriving at the labor and delivery unit.16

Legal considerations

With the COVID-19 pandemic, temporary changes were made to encourage the rapid adoption of telemedicine, including changes to licensing laws, certain prescription requirements, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy-security regulations, and reimbursement rules that required in-person visits. Thus, many ObGyns started using telemedicine during this rarified period, in which the rules appeared to be few and far between, with limited enforcement of the law and professional obligations.17 However, now that many of the legal rules that were suspended or ignored have been (or are being) reimposed and enforced, it is important for providers to become familiar with the legal issues involved in practicing telemedicine.

First, where is the patient? When discussing the legal issues of telemedicine, it is important to remember that many legal rules for medical care (ie, liability, informed consent, and licensing) vary from state to state. If the patient resides in a different state (“foreign” state) from the physician’s practice location (the physician’s “home” state), the care is considered delivered in the state where the patient is located. Thus, the patient’s location generally establishes the law covering the telemedicine transaction. In the following discussion, the rules refer to the law and professional obligations, with commentary on some key legal issues that are relevant to ObGyn telemedicine.

Continue to: Reinforcing the rules...

Reinforcing the rules

Licensing

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government and almost all states temporarily modified the licensing requirement to allow telemedicine based on an existing medical license in any state—disregarding the “where is the patient” rule. As those rules begin to lapse or change with the official end of the pandemic declared by President Biden as May 2023,17 the rules under which a physician began telemedicine interstate practice in 2020 also may be changing.

Simply put, “The same standards for licensure apply to health care providers regardless of whether care is delivered in-person or virtually through telehealth services.”18 When a physician is engaged in telemedicine treatment of a patient in the physician’s home state, there is generally no licensing issue. Telemedicine generally does not require a separate specific license.19 However, when the patient is in another state (a “foreign” state), there can be a substantial licensing issue.20 Ordinarily, to provide that treatment, the physician must, in some manner, be approved to practice in the patient’s state. That may occur, for example, in the following ways: (1) the physician may hold an additional regular license in the patient’s state, which allows practice there, or (2) the physician may have received permission for “temporary practice” in another state.

Many states (often adjoining states) have formal agreements with other states that allow telemedicine practice by providers in each other’s states. There also are “compacts”, or agreements that enable providers in any of the participating states to practice in the other associated states without a separate license.18 Although several websites provide information about compact licensing and the like, clinicians should not rely on simple lists or maps. Individual states may have special provisions about applying their laws to out-of-state “compact” physicians. In addition, under the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact, “physicians have to pay licensing fees and satisfy the requirements of each medical board in the states where they wish to practice.”21

Consequences. Practicing telemedicine with a patient in a state where the physician does not have a license is generally a crime. Furthermore, it may be the basis for license discipline in the physician’s home state and result in a report to the National Practi-tioner Databank.22 In addition, reimbursement often depends on the practitioner being licensed, and the absence of a license may be a basis for denying payment for services.23 Finally, malpractice insurance generally is limited to licensed practice. Thus, the insurer may decline to defend the unlicensed clinician against a malpractice claim or pay any damages.

Prescribing privileges

Prescribing privileges usually are connected to licensing, so as the rules for licensing change postpandemic, so do the rules for prescribing. In most cases, the physician must have a license in the state where care is given to prescribe medication—which in telemedicine, as noted, typically means the state where the patient is located. Exceptions vary by state, but in general, if a physician does not have a license to provide care, the physician is unlikely to be authorized to prescribe medication.24 Failure to abide by the applicable state rules may result in civil and even criminal liability for illegal prescribing activity.

In addition, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA, which enforces laws concerning controlled substances) also regulate the prescription and sale of pharmaceuticals.25 There are state and federal limits on the ability of clinicians to order controlled substances without an in-person visit. The Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act, for example, sets limits on controlled substance prescriptions without an in-person examination.26 Federal law was modified due to COVID-19 to permit prescribing of many controlled substances by telemedicine if there is synchronous audio and visual examination of the patient. Physicians who write such prescriptions also are required to have a DEA registration in the patient’s state. This is an essential consideration for physicians considering interstate telemedicine practice.27

HIPAA and privacy

Governments waived some of the legal requirements related to health information during the pandemic, but those waivers either have expired or will do so soon. Federal and state laws regarding privacy and security—notably including HIPAA—apply to telemedicine and are of particular concern given the considerable amount of communication of protected health information with telemedicine.

HIPAA security rules essentially require making sure health information cannot be hacked or intercepted. Audio-only telemedicine by landline (not cell) is acceptable under the security rules, but almost all other remote communication requires secure communications.28

Clinicians also need to adhere to the more usual HIPAA privacy rules when practicingtelehealth. State laws protecting patient privacy vary and may be more stringent than HIPAA, so clinicians also must know the requirements in any state where they practice—whether in office or telemedicine.29

Making sure telemedicine practices are consistent with these security and privacy rules often requires particular technical expertise that is outside the realm of most practicing clinicians. However, without modification, the pre-telemedicine technology of many medical offices likely is insufficient for the full range of telemedicine services.30

Reimbursement and fraud

Before COVID-19, Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement for telemedicine was limited. Government decisions to substantially broaden those reimbursement rules (at least temporarily) provided a substantial boost to telemedicine early in the pandemic.23 Federal regulations and statutes also expanded telemedicine reimbursement for various services. Some will end shortly after the health emergency, and others will be permanent. Parts of that will not be sorted out for several years, so it will likely be a changing landscape for reimbursement.

Continue to: Rules that are evolving...

Rules that are evolving

Informed consent

The ethical and legal obligations to obtain informed consent are present in telemedicineas well as in-person care, with the same basic requirements regarding risks, benefits, alternative care, etc.32 However, with telemedicine, information related to remote care should be included and is outlined in TABLE 1.

Certain states may have somewhat unique informed consent requirements—especially for reproductive care, including abortion.34 Therefore, it is important for clinicians to ensure their consent process and forms comply with any legal jurisdiction in which a patient is located.

Medical malpractice

The basics of medical malpractice (or negligence) are the same in telemedicine as in in-person care: duty, breach of duty, and injury caused by the breach. That is, there may be liability when a medical professional breaches the duty of care, causing the patient’s injury. The physician’s duty is defined by the quality of care that the profession (specialty) accepts as reasonably good. This is defined by the opinions of physicians within the specialty and formal statements from professional organizations, including ACOG.3

Maintaining the standard of care and quality. The use of telemedicine is not an excuse to lower the quality of health care. There are some circumstances for which it is medically better to have an in-person visit. In these instances, the provider should recommend the appropriate care, even if telemedicine would be more convenient for the provider and staff.35

If the patient insists and telemedicine might result in less than optimal care, the reasons for using a remote visit should be clearly documented contemporaneously with the decision. Furthermore, when the limitations of being unable to physically examine the patient result in less information than is needed for the patient’s care, the provider must find alternatives to make up for the information gap.11,36 It also may be necessary to inform patients about how to maximize telemedicine care.37 At the beginning of telemedicine care the provider should include information about the nature and limits of telehealth, and the patient’s responsibilities. (See TABLE 1) Throughout treatment of the patient, that information should be updated by the provider. That, of course, is particularly important for patients who have not previously used telemedice services.

Malpractice rules vary by state. Many states have special rules regarding malpractice cases. These differences in malpractice standards and regulations “can be problematic for physicians who use telemedicine services to provide care outside the state in which they practice.”38 Caps on noneconomic damages are an example. Those state rules would apply to telemedicine in the patient’s state.

Malpractice insurance

Malpractice insurance now commonly includes telemedicine legally practiced within the physician’s home state. Practitioners who treat patients in foreign states should carefully examine their malpractice insurance policies to confirm that the coverage extends to practice in those states.39 Malpractice carriers may require notification by a covered physician who routinely provides services to patients in another state.3

Keep in mind, malpractice insurance generally does not cover the practice of medicine that is illegal. Practicing telemedicine in a foreign state, where the physician or other provider does not have a license and where that state does not otherwise permit the practice, is illegal. Most likely, the physician’s malpractice insurance will not cover claims that arise from this illegal practice in a foreign state or provide defense for malpractice claims, including frivolous lawsuits. Thus, the physician will pay out of pocket for the costs of a defense attorney.

Telemedicine treatment of minors

Children and adolescents present special legal issues for ObGyn care, which may become more complicated with telemedicine. Historically, parents are responsible for minors (those aged <18 years): they consent to medical treatment, are responsible for paying for it, and have the right to receive information about treatment.

Over the years, though, many states have made exceptions to these principles, especially with regard to contraception and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases.40 For abortion, in particular, there is considerable variation among the states in parental consent and notification.41 The Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health42 may (depending on the state) be followed with more stringent limitations on adolescent consent to abortions, including medical abortions.43

Use of telehealth does not change any obligations regarding adolescent consent or parental notification. Because those differ considerably among states, it is important for all practitioners to know their states’ requirements and keep reasonably complete records demonstrating their compliance with state law.

Abortion

The most heated current controversy about telemedicine involves abortion—specifically medical abortion, which is the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol.44,45 The FDA approved the combination in 2000. Almost immediately, many states required in-person visits with a certified clinician to receive a prescription for mifepristone and misoprostol, and eventually, the FDA adopted similar requirements.46 However, during the pandemic from 2021 to 2022, the FDA permitted telemedicine prescriptions. Several states still require in-person physician visits, although the constitutionality of those requirements has not been established.47

With the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health in 2022,42 disagreements have ensued about the degree to which states may regulate the prescription of FDA-approved medical abortion drugs. Thorny constitutional issues exist in the plans of both abortion opponents and proponents in the battle over medical abortion in antiabortion states. It may be that federal drug law preempts state laws limiting access to FDA-approved drugs. On the other hand, it may be that states can make it a crime within the state to possess or provide abortion-inducing drugs. Courts will probably take years to resolve the many tangled legal questions.48

Thus, while the pandemic telemedicine rules may have advanced access to abortion,34 there may be some pending downsides.49 States that prohibit abortion will likely include prohibitions on medical abortions. In addition, they may prohibit anyone in the state (including pharmacies) from selling, possessing, or obtaining any drug used for causing or inducing an abortion.50 If, for constitutional reasons, they cannot press criminal charges or undertake licensing discipline for prescribing abortion, some states will likely withdraw from telehealth licensing compacts to avoid out-of-state prescriptions. This area of telemedicine has considerable uncertainty.

Continue to: CASE Conclusion...

CASE Conclusion

Patient concerns come to the fore

By 2023, Dr. TM started receiving bad news. Patient D called complaining that after following the advice on the website, she suffered a severe reaction and had to be rushed to an emergency department. Patient E (who had only 1 in-office visit early in her pregnancy) notified the office that she developed very high blood pressure that resulted in severe placental abruption, requiring emergency care and resulting in the loss of the fetus. Patient F complained that someone hacked the TikTok direct message communication with Dr. TM and tried to “blackmail” or harass her.

Discussion. Patients D, E, and F represent potential problems of telemedicine practice. Patient D was injured because she relied on her doctor’s website (to which Dr. TM directed patients). It contained an error that caused an injury. A doctor-patient relationship existed, and bad medical advice likely caused the injury. Physicians providing advice online must ensure the advice is correct and kept current.

Patient E demonstrates the importance of monitoring patients remotely (blood pressure transmitted to the office) or with periodic in-office visits. It is not clear whether she was a no-show for office visits (and whether the office followed up on any missed appointments) or if such visits were never scheduled. Liability for failure to monitor adequately is a possibility.

Patient F’s seemingly minor complaint could be a potential problem. Dr. TM used an insecure mode of communication. Although some HIPAA security regulations were modified or suspended during the pandemic, using such an unsecure platform is problematic, especially if temporary HIPAA rules expired. The outcome of the complaint is in doubt.

(See TABLE 2 for additional comments on patients D, E, and F.)

Out-of-state practice

Dr. TM treated 3 out-of-state residents (D, E, and F) via telemedicine. Recently Dr. TM received a complaint from the State Medical Licensure Board for practicing medicine without a license (Patient D), followed by similar charges from Patient E’s and Patient F’s state licensing boards. He has received a licensing inquiry from his home state board about those claims of illegal practice in other states and incompetent treatment.

Patient D’s pregnancy did not go well. The 1 in-person visit did not occur and she has filed a malpractice suit against Dr. TM. Patient E is threatening a malpractice case because the STI was not appropriately diagnosed and had advanced before another physician treated it.

In addition, a private citizen in Patient F’s state has filed suit against Dr. TM for abetting an illegal abortion (for Patient F).

Discussion. Patients D, E, and F illustrate the risk of even incidental out-of-state practice. The medical board inquiries arose from anonymous tips to all 4 states reporting Dr. TM was “practicing medicine without a license.” Patient E’s home state did have a licensing compact with the adjoining state (ie, Dr. TM’s home state). However, it required physicians to register and file an annual report, which Dr. TM had not done. The other 2 states did not have compacts with Dr. TM’s home state. Thus, he was illegally practicing medicine and would be subject to penalties. His home state also might impose license discipline based on his illegal practice in other states.

Continue to: What’s the verdict?...

What’s the verdict?

Dr. TM’s malpractice carrier is refusing to defend the claims of medical malpractice threatened by Patients D, E, and F. The company first notes that the terms of the malpractice policy specifically exclude the illegal practice of medicine. Furthermore, when a physician legally practices in another state, the policy requires a written notice to the insurance carrier of such practice. Dr. TM will likely have to engage and pay for a malpractice attorney for these cases. Because the claims are filed in 3 different states, more than a home-state attorney will likely be involved in the defense of these cases. Dr. TM will need to pay the attorneys and any damages from a settlement or trial.

Malpractice claims. Patient D claims that the doctor essentially abandoned her by never reaching out to her or arranging an in-person visit. Dr. TM claims the patient was responsible for scheduling the in-person visit. Patient E claims it was malpractice not to determine the specific nature of the STI and to do follow-up testing to determine that it was cured. All patients claim there was no genuine informed consent to the telemedicine. An attorney has warned Dr. TM that it is “not going to look good to the jury” that he was practicing without a license in the state and suggests he settle the cases quickly by paying damages.

Abortion-related claims. Patient F presents a different set of problems. Dr. TM’s home state is “proabortion.” Patient F’s home state is strongly “antiabortion,” making it a felony to participate in, assist, or facilitate an abortion (including medical abortion). Criminal charges have been filed against Dr. TM for the illegal practice of medicine, for aiding and facilitating an abortion, and for failure to notify a parent that a minor is seeking an abortion. For now, Dr. TM’s state is refusing to extradite on the abortion charge. Still, the patient’s state insists that it do so on the illegal practice of medicine charges and new charges of insurance fraud and failure to report suspected sexual abuse of a child. (Under the patient’s state law, anyone having sex with Patient F would have engaged in sexual abuse or “statutory rape,” so the state insists that the fact she was pregnant proves someone had sex with her.)

Patient F’s state also has a statute that allows private citizens to file civil claims against anyone procuring or assisting with an abortion (a successful private citizen can receive a minimum of $10,000 from the defendant). Several citizens from the patient’s state have already filed claims against Dr. TM in his state courts. Only one of them, probably the first to file, could succeed. Courts in the state have issued subpoenas and ordered Dr. TM to appear and reply to the civil suits. If he does not respond, there will be a default judgment.

Dr. TM’s attorney tells him that these lawsuits will not settle and will take a long time to defend and resolve. That will be expensive.

Billing and fraud. Dr. TM’s office recently received a series of notices from private health insurers stating they are investigating previously made payments as being fraudulent (unlicensed). They will not pay any new claims pending the investigation. On behalf of Medicare-Medicaid and other federal programs, the US Attorney’s office has notified Dr. TM that it has opened an investigation into fraudulent federal payments. F’s home state also is filing a (criminal) insurance fraud case, although the basis for it is unclear. (Dr. TM’s attorney believes it might be to increase pressure on the physician’s state to extradite Dr. TM for Patient F’s case.)

In addition, a disgruntled former employee of Dr. TM has filed a federal FCA case against him for filing inflated claims with various federally funded programs. The employee also made whistleblower calls to insurance companies and some state-funded medical programs. A forensic accounting investigation by Dr. TM’s accountant confirmed a pattern of very sloppy records and recurring billing for televisits that did not occur. Dr. TM believes that this was the act of one of the temporary assistants he hired in a pinch, who did not understand the system and just guessed when filing some insurance claims.

During the investigation, the federal and state attorneys are looking into a possible violation of state and federal Anti-Kickback Statutes. This is based on the original offer of a $100 credit for referrals to Dr. TM’s telemedicine practice.

The attorneys are concerned that other legal problems may present themselves. They are thoroughly reviewing Dr. TM’s practice and making several critical but somewhat modest changes to his practice. They also have insisted that Dr. TM have appropriate staff to handle the details of the practice and billing.

Conclusions

Telemedicine presents notable legal challenges to medical practice. As the pandemic status ends, ObGyn physicians practicing telemedicine need to be aware of the rules and how they are changing. For those physicians who want to continue or start a telemedicine practice, securing legal and technical support to ensure your operations are inline with the legal requirements can minimize any risk of legal troubles in the future. ●

A physician in State A, where abortion is legal, has a telemedicine patient in State B, where it is illegal to assist, provide, or procure an abortion. If the physician prescribes a medical abortion, he would violate the law of State B by using telemedicine to help the patient (located in State B) obtain an abortion. This could result in criminal charges against the prescribing physician.

Telemedicine (or telehealth) originated in the early 1900s, when radios were used to communicate medical advice to clinics aboard ships.1 According to the American Telemedicine Association, telemedicine is namely “the use of medical information exchanged from one site to another via electronic communications to improve a patient’s clinical health status.”2 These communications use 2-way video, email, smartphones, wireless tools, and other forms of telecommunications technology.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many ObGyns—encouraged and advised by professional organizations—began providing telemedicine services.3 The first reported case of COVID-19 was in late 2019; the use of telemedicine was 38 times higher in February 2021 than in February 2020,4 illustrating how many physicians quickly moved to telemedicine practices.

CASE Dr. TM’s telemedicine dream

Before COVID-19, Dr. TM (an ObGyn practi-tioner) practiced in-person medicine in his home state. With the onset of the pandemic, Dr. TM struggled to switch to primarily seeing patients online (generally using Zoom or Facebook Live), with 1 day per week in the office for essential in-person visits.

After several months, however, Dr. TM’s routine became very efficient. He could see many more patients in a shorter time than with the former, in-person system. Therefore, as staff left his practice, Dr. TM did not replace them and also laid off others. Ultimately, the practice had 1 full-time records/insurance secretary who worked from home and 1 part-time nurse who helped with the in-person day and answered some patient inquiries by email. In part as an effort to add new patients, Dr. TM built an engaging website through which his current patients could receive medical information and new patients could sign up.

In late 2022, Dr. TM offered a $100 credit to any current patient who referred a friend or family member who then became a patient. This promotion was surprisingly effective and resulted in an influx of new patients. For example, Patient Z (a long-time patient) received 3 credits for referring her 3 sisters who lived out of state and became telepatients: Patient D, who lived 200 hundred miles away; Patient E, who lived 50 miles away in the adjoining state; and Patient F, who lived 150 miles away. Patient D contacted Dr. TM because she thought she was pregnant and wanted prenatal care, Patient E thought she might have a sexually transmitted infection (STI) and wanted treatment, and Patient F wanted general care and was inquiring about a medical abortion. Dr. TM agreed to treat Patient D but required 1 in-person visit. After 1 brief telemedicine session each with Patients E and F, Dr. TM wrote prescriptions for them.

By 2023, Dr. TM was enthusiastic about telemedicine as a professional practice. However, problems would ensue.

Dos and don’ts of telemedicine2

- Do take the initiative and inform patients of the availability of telemedicine/telehealth services

- Do use the services of medical malpractice insurance companies with regard to telemedicine

- Do integrate telemedicine into practice protocols and account for their limitations

- Don’t assume there are blanket exemptions or waivers in the states where your patients are located

Medical considerations

Telemedicine is endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) as a vehicle for delivering prenatal and postpartum care.5 This represents an effort to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality,5 as well as expandaccess to care and address the deficit in primary care providers and services, especially in rural and underserved populations.5,6 For obstetrics, prenatal care is designed to optimize pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care, with a focus on nutrition and genetic consultation and patient education on pregnancy, childbearing, breastfeeding, and newborn care.7

Benefits of telemedicine include its convenience for patients and providers, its efficiency and lower costs for providers (and hopefully patients, as well), and the potential improved access to care for patients.8 It is estimated that if a woman inititates obstetric care at 6 weeks, over the course of the 40-week gestation period, 15 prenatal visits will occur.9 Ultimately, the number of visits is determined based on the specifics of the pregnancy. With telemedicine, clinicians can provide those consultations, and information related to: ultrasonography, fetal echocardiography, and postpartum care services remotely.10 Using telemedicine may reduce missed visits, and remote monitoring may improve the quality of care.11

Barriers to telemedicine care include technical limitations, time constraints, and patient concerns of telehealth (visits). Technical limitations include the lack of a high speed internet connection and/or a smart device and the initial technical set-up–related problems,12 which affect providers as well as patients. Time constraints primarly refer to the ObGyn practice’s lack of time to establish telehealth services.13 Other challenges include integrating translation services, billing-related problems,10 and reimbursement and licensing barriers.14

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, obstetrics led the way in telemedicine with the development of the OB Nest model. Designed to replace in-person obstetrics care visits with telehealth,15 it includes home management tools such as blood pressure cuffs, cardiotocography, scales for weight checks, and Doppler ultrasounds.10 Patients can be instructed to measure fundal height and receive medications by mail. Anesthesia consultation can occur via this venue by having the patient complete a questionnaire prior to arriving at the labor and delivery unit.16

Legal considerations

With the COVID-19 pandemic, temporary changes were made to encourage the rapid adoption of telemedicine, including changes to licensing laws, certain prescription requirements, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy-security regulations, and reimbursement rules that required in-person visits. Thus, many ObGyns started using telemedicine during this rarified period, in which the rules appeared to be few and far between, with limited enforcement of the law and professional obligations.17 However, now that many of the legal rules that were suspended or ignored have been (or are being) reimposed and enforced, it is important for providers to become familiar with the legal issues involved in practicing telemedicine.

First, where is the patient? When discussing the legal issues of telemedicine, it is important to remember that many legal rules for medical care (ie, liability, informed consent, and licensing) vary from state to state. If the patient resides in a different state (“foreign” state) from the physician’s practice location (the physician’s “home” state), the care is considered delivered in the state where the patient is located. Thus, the patient’s location generally establishes the law covering the telemedicine transaction. In the following discussion, the rules refer to the law and professional obligations, with commentary on some key legal issues that are relevant to ObGyn telemedicine.

Continue to: Reinforcing the rules...

Reinforcing the rules

Licensing

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government and almost all states temporarily modified the licensing requirement to allow telemedicine based on an existing medical license in any state—disregarding the “where is the patient” rule. As those rules begin to lapse or change with the official end of the pandemic declared by President Biden as May 2023,17 the rules under which a physician began telemedicine interstate practice in 2020 also may be changing.

Simply put, “The same standards for licensure apply to health care providers regardless of whether care is delivered in-person or virtually through telehealth services.”18 When a physician is engaged in telemedicine treatment of a patient in the physician’s home state, there is generally no licensing issue. Telemedicine generally does not require a separate specific license.19 However, when the patient is in another state (a “foreign” state), there can be a substantial licensing issue.20 Ordinarily, to provide that treatment, the physician must, in some manner, be approved to practice in the patient’s state. That may occur, for example, in the following ways: (1) the physician may hold an additional regular license in the patient’s state, which allows practice there, or (2) the physician may have received permission for “temporary practice” in another state.

Many states (often adjoining states) have formal agreements with other states that allow telemedicine practice by providers in each other’s states. There also are “compacts”, or agreements that enable providers in any of the participating states to practice in the other associated states without a separate license.18 Although several websites provide information about compact licensing and the like, clinicians should not rely on simple lists or maps. Individual states may have special provisions about applying their laws to out-of-state “compact” physicians. In addition, under the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact, “physicians have to pay licensing fees and satisfy the requirements of each medical board in the states where they wish to practice.”21