User login

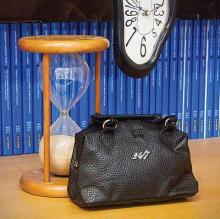

In April 1977, shortly after the new American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) was constituted, it adopted the hourglass as its symbol for the unique nature of emergency medicine—a specialty in large part defined by the very brief time in which emergency physicians (EPs) must correctly identify and treat serious, life-threatening conditions. Incorporating the concept of the “golden hour” in which to prevent the irreversible consequences of serious trauma, and the frequently even shorter period to effectively intervene after cardiovascular and neurovascular catastrophes, the hourglass has become a powerful symbol that all emergency physicians are very, very proud of.

In the years since the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) recognized Emergency Medicine as the 23rd specialty, though much about emergency medicine has remained the same, much has also changed. Currently, the time patients spend in EDs throughout the country is all too frequently determined, not by the time required to diagnose and initiate treatment for their illnesses, but by the time required for an inpatient bed to become available or for safe, reliable outpatient care to be arranged. In some hospitals, ED patients who are admitted and require inpatient care or “observation services” continue to be cared for by EPs and ED nurses, while in other hospitals the care and responsibility for such patients is transferred to the appropriate inpatient service—even as the patients remain for hours or days on ED stretchers on the ground floor of the hospital. In some cases, an entire “hospitalization” takes place in the ED.

Similarly, when the specialty of emergency medicine was first established, it faced not only time, but resource-limitations as well. Few CT scanners then were commonly available in close proximity to EDs; afterward, when CT scans did become easily accessible to ED patients and MRI scanners began to appear, no one considered MRI scans to be “ED procedures” because of the time required to complete the studies. This, of course, was before managed-care appeared on the scene and, more recently, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began to seriously question the need for some admissions and short hospital stays. The 2013 Rand Research Report on the “Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States” (http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR200/RR280/RAND_RR280.pdf) clearly describes the many other things that emergency medicine now encompasses.

If the venerable hourglass no longer depicts all that emergency medicine has become, is it time to freshen the image or adopt a new symbol? One other extremely significant time-related feature of emergency medicine that has endured is the recognition that the hours during which the human body gets sick or injured are not restricted to typical work hours or work days, and that, as the title of Brian Zink’s book suggests, EPs are trained to care for “Anyone, Anything, Anytime” (Anyone, Anything, Anytime: A History of Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, Inc; 2006). Perhaps, the time has come to add “24/7” to the hourglass symbol. This suggestion is not as frivolous as it may sound, as increasingly federal and state governments and private insurers are using the availability of care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week as a principal characteristic that differentiates emergency medicine, and the higher reimbursement rates it commands, from the care provided by urgent care and “convenient care” centers.

In April 1977, shortly after the new American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) was constituted, it adopted the hourglass as its symbol for the unique nature of emergency medicine—a specialty in large part defined by the very brief time in which emergency physicians (EPs) must correctly identify and treat serious, life-threatening conditions. Incorporating the concept of the “golden hour” in which to prevent the irreversible consequences of serious trauma, and the frequently even shorter period to effectively intervene after cardiovascular and neurovascular catastrophes, the hourglass has become a powerful symbol that all emergency physicians are very, very proud of.

In the years since the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) recognized Emergency Medicine as the 23rd specialty, though much about emergency medicine has remained the same, much has also changed. Currently, the time patients spend in EDs throughout the country is all too frequently determined, not by the time required to diagnose and initiate treatment for their illnesses, but by the time required for an inpatient bed to become available or for safe, reliable outpatient care to be arranged. In some hospitals, ED patients who are admitted and require inpatient care or “observation services” continue to be cared for by EPs and ED nurses, while in other hospitals the care and responsibility for such patients is transferred to the appropriate inpatient service—even as the patients remain for hours or days on ED stretchers on the ground floor of the hospital. In some cases, an entire “hospitalization” takes place in the ED.

Similarly, when the specialty of emergency medicine was first established, it faced not only time, but resource-limitations as well. Few CT scanners then were commonly available in close proximity to EDs; afterward, when CT scans did become easily accessible to ED patients and MRI scanners began to appear, no one considered MRI scans to be “ED procedures” because of the time required to complete the studies. This, of course, was before managed-care appeared on the scene and, more recently, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began to seriously question the need for some admissions and short hospital stays. The 2013 Rand Research Report on the “Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States” (http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR200/RR280/RAND_RR280.pdf) clearly describes the many other things that emergency medicine now encompasses.

If the venerable hourglass no longer depicts all that emergency medicine has become, is it time to freshen the image or adopt a new symbol? One other extremely significant time-related feature of emergency medicine that has endured is the recognition that the hours during which the human body gets sick or injured are not restricted to typical work hours or work days, and that, as the title of Brian Zink’s book suggests, EPs are trained to care for “Anyone, Anything, Anytime” (Anyone, Anything, Anytime: A History of Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, Inc; 2006). Perhaps, the time has come to add “24/7” to the hourglass symbol. This suggestion is not as frivolous as it may sound, as increasingly federal and state governments and private insurers are using the availability of care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week as a principal characteristic that differentiates emergency medicine, and the higher reimbursement rates it commands, from the care provided by urgent care and “convenient care” centers.

In April 1977, shortly after the new American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) was constituted, it adopted the hourglass as its symbol for the unique nature of emergency medicine—a specialty in large part defined by the very brief time in which emergency physicians (EPs) must correctly identify and treat serious, life-threatening conditions. Incorporating the concept of the “golden hour” in which to prevent the irreversible consequences of serious trauma, and the frequently even shorter period to effectively intervene after cardiovascular and neurovascular catastrophes, the hourglass has become a powerful symbol that all emergency physicians are very, very proud of.

In the years since the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) recognized Emergency Medicine as the 23rd specialty, though much about emergency medicine has remained the same, much has also changed. Currently, the time patients spend in EDs throughout the country is all too frequently determined, not by the time required to diagnose and initiate treatment for their illnesses, but by the time required for an inpatient bed to become available or for safe, reliable outpatient care to be arranged. In some hospitals, ED patients who are admitted and require inpatient care or “observation services” continue to be cared for by EPs and ED nurses, while in other hospitals the care and responsibility for such patients is transferred to the appropriate inpatient service—even as the patients remain for hours or days on ED stretchers on the ground floor of the hospital. In some cases, an entire “hospitalization” takes place in the ED.

Similarly, when the specialty of emergency medicine was first established, it faced not only time, but resource-limitations as well. Few CT scanners then were commonly available in close proximity to EDs; afterward, when CT scans did become easily accessible to ED patients and MRI scanners began to appear, no one considered MRI scans to be “ED procedures” because of the time required to complete the studies. This, of course, was before managed-care appeared on the scene and, more recently, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began to seriously question the need for some admissions and short hospital stays. The 2013 Rand Research Report on the “Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States” (http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR200/RR280/RAND_RR280.pdf) clearly describes the many other things that emergency medicine now encompasses.

If the venerable hourglass no longer depicts all that emergency medicine has become, is it time to freshen the image or adopt a new symbol? One other extremely significant time-related feature of emergency medicine that has endured is the recognition that the hours during which the human body gets sick or injured are not restricted to typical work hours or work days, and that, as the title of Brian Zink’s book suggests, EPs are trained to care for “Anyone, Anything, Anytime” (Anyone, Anything, Anytime: A History of Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, Inc; 2006). Perhaps, the time has come to add “24/7” to the hourglass symbol. This suggestion is not as frivolous as it may sound, as increasingly federal and state governments and private insurers are using the availability of care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week as a principal characteristic that differentiates emergency medicine, and the higher reimbursement rates it commands, from the care provided by urgent care and “convenient care” centers.