User login

A 40-year-old woman, a childhood immigrant from India, is seeking advice regarding her upcoming two-week trip to Mumbai. She is taking her two children, ages 16 years and 16 months, to visit their grandparents for the first time. She has made this trip alone a few times and has invariably experienced short bouts of self-limited diarrheal illness. She wonders what she might do to prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Her only medical problem is rheumatoid arthritis, which has been well controlled with methotrexate. Her children are healthy. What would you recommend?

Recommendations regarding travelers’ diarrhea (TD) address prevention and management. Prevention encompasses advice about personal behaviors and the use of chemoprophylaxis (antimicrobial and nonantimicrobial) and vaccinations. Since international travelers are known to treat themselves for diarrheal illnesses during their trips,1 recommendations regarding management should assume self-treatment and include the use of both antibiotic and nonantibiotic remedies. Pretravel recommendations will of course be most effective if they account for the individual’s risk for TD.

TD RISK

TD is generally defined as the passage of three or more loose stools in a 24-hour period, with associated symptoms of enteric infection (eg, fever, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal cramping). Defined in this manner, TD is thought to occur in 60% to 70% of individuals who travel from developed countries to less-developed countries.2-4 Risk for TD is influenced both by intrinsic personal factors and by factors specific to the trip.

Personal risk factors

Individual variation in susceptibility to TD might result from a genetic predisposition arising from single nucleotide polymorphisms governing various inflammatory marker proteins.5 A history of multiple episodes of TD, especially if fellow travelers were spared, can suggest this kind of individual susceptibility. Other factors that increase vulnerability to TD are immunodeficiency, achlorhydric states such as atrophic gastritis, and chronic use of proton pump inhibitors.6,7 However, the trip itself is much more important in assessing risk for TD.

Trip-related risk factors

The destination. The most salient risk factor for TD is the geographic destination. Regions of the world can be divided into TD risk strata2:

• Very high: South Asia

• High: South America, Sub-Saharan Africa

• Medium: Central America, Mexico, Caribbean, Middle East, North Africa, Southeast Asia, Oceania

• Low: Europe, North America (excluding Mexico), Australasia, Northeast Asia

Particularly notable countries, in descending order of risk, are Nepal, India, Myanmar, Bolivia, Sri Lanka, Ecuador, Peru, Kenya, and Guatemala.2

Dietary choices. Additionally, since travelers acquire TD by ingesting food or beverages contaminated with pathogenic fecal microbes, dietary behaviors during the trip affect their susceptibility. At least risk are business travelers and tourists who confine their activities to more affluent settings in which food and beverages are prepared and stored hygienically.1,4,8,9 At greater risk are travelers who immerse themselves in local culture, visiting locations that are more impoverished and not as well equipped with sanitation systems, especially if their stay lasts at least two to three weeks.1,4,8,9

Also, the older a traveler is, the lower his or her risk for TD.1,9 An exception to this might be infants whose diet consists solely of breast milk or formula prepared under sanitary conditions.

Continued on next page >>

TD PREVENTION

Emphasize food and beverage precautions

It might be reasonable to expect that travelers who are circumspect about their food and beverage choices on trips will be able to avoid TD. Indeed, this is the basis for the aphorism, “Boil it, peel it, or forget it.” Guidelines routinely recommend that travelers restrict their selection of foods to those that have been well cooked and are served while still very hot, as well as to fruits and vegetables that they peel themselves. Likewise, they should drink only beverages that have been boiled or are in sealed bottles or under carbonation and served without ice.10-12

Many travelers might find these recommendations too restrictive to follow faithfully. Moreover, studies suggest it may not be possible for even the most assiduous traveler to fully avoid the risk for TD.13,14 The hygienic characteristics of the travel destination may be more determinative, as illustrated by the successful reduction of TD rates in Jamaica by improving sanitation in tourist resorts.15

Antibiotic chemoprophylaxis: A debated practice with limited consensus

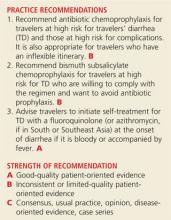

The etiologic agents of TD are multiple and vary somewhat in predominance according to geographic region.3,16,17 Table 1 depicts variance by region. The most common pathogens are strains of the bacterium Escherichia coli, particularly enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteroaggregative, and enteropathogenic strains.16 Other bacteria of importance are Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella. Viruses, particularly norovirus (notably connected with cruise ships), can also cause TD, although it is implicated in no more than 17% of cases.18 Parasitic pathogens are even less common causes of TD (4% to 10%) and mainly involve the protozoa, Giardia lamblia, and, to a lesser extent, Entamoeba histolytica and Cryptosporidium.

Although some pathogens often have a characteristic presentation—such as frothy, greasy diarrhea in the case of G lamblia—in general, they cannot be reliably distinguished from one another clinically. Notably, up to 50% of stool samples from TD patients do not yield any pathogen,16 raising the suspicion that current diagnostic technology is not sufficiently sensitive to routinely identify certain bacteria.

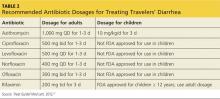

There is no consensus on recommending antibiotic chemoprophylaxis against TD.

Opponents of this practice point out that TD is generally a brief (three to five days), self-limited illness.10-12,19,20 Moreover, concerns about antibiotic resistance have come to pass. Previously used agents (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline) are no longer effective in preventing or treating TD. In addition, antibiotic use carries the risk for allergic reactions, as well as other adverse effects including (ironically) the development of antibiotic-associated and Clostridium difficile diarrhea.

Proponents of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis point to its demonstrated efficacy in reducing the risk for TD by 4% to 40%.11,21,22 They also argue that at least 20% to 25% of travelers who get TD must significantly curtail their activities for a day or more.1,23 This change in travel plans is associated not only with significant personal loss but also imposes a financial burden.23 Furthermore, TD is known to have longer-term effects. Up to 10% of those affected develop postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS) that can last for five or six years.21,22,24,25 It is not known, however, whether the use of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis significantly reduces the incidence of PI-IBS.

Finally, the luminal antibiotic rifaximin, nonabsorbable as it is, is very well tolerated and holds promise for not inciting antibiotic resistance.22 However, while its efficacy in preventing TD has been demonstrated in various settings,22,26,27 it is not approved by the FDA for this indication. Also, concerns persist that it might not be effective in preventing TD caused by invasive pathogens.19

Indications on which all agree. Even opponents of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis grant that it is probably warranted for two groups of travelers.10-12 The first is those whose trip schedule is of such importance that any deviation would be intolerable. The second is travelers with comorbidities that would render them at high risk for serious inconvenience or illness if they developed TD. Examples of the latter include patients with enterostomies, mobility impairments, immune suppression, inflammatory bowel disease, and renal or metabolic diseases.

Chemoprophylaxis regimens. If you prescribe an antibiotic prophylactically, consider daily doses of a fluoroquinolone (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily, not twice daily as for treatment) or rifaximin 200 mg orally once or twice a day, for no longer than two to three weeks.10

Nonantimicrobial chemoprophylaxis

Bismuth subsalicylate has reduced the incidence of TD from 40% to just 14% when taken in doses of two chewable tablets or 60 mL of liquid four times daily.11,19,22 However, the dosing frequency can hinder adherence. Moreover, the relatively high doses required raise the risk for adverse drug reactions, such as blackening of the tongue and stool, nausea, constipation, Reye syndrome (in children younger than 12), and possibly tinnitus. The salicylate component of the drug poses a threat to patients with aspirin allergy or renal disease and those taking anticoagulants. Drug interactions with probenecid and methotrexate are also possible. Bismuth is not recommended for use for longer than three weeks, or for children younger than 3 years or pregnant women in their third trimester.

Probiotics such as Lactobacillus and Saccharomyces are among the other nonantimicrobial chemoprophylaxis agents. These preparations of bacteria and fungi are marketed either singly or in blends of varying composition and proportion. The evidence is divided on their efficacy, and even though some meta-analyses have concluded probiotics such as Saccharomyces boulardii are useful in preventing TD, endorsement in clinical guidelines is muted.10-12,28-30

Immunizations have limited value so far

Natural immunity to E coli gastrointestinal infection among indigenous people in less developed countries has raised the possibility of a role for vaccines in preventing TD. Some strains of ETEC produce a heat-labile toxin (LT) that bears significant resemblance to the toxin produced by Vibrio cholerae. Therefore, the oral cholera vaccine has been marketed outside the United States for the prevention of TD.19,22 However, only ≤ 7% of TD cases worldwide would be prevented by routine use of this vaccine.31 A transdermal LT vaccine, which involves the antigen-presenting Langerhans cells in the superficial skin layers, is promising but not yet available for routine use.19,22

Continued on next page >>

TREATING TD AND ASSOCIATED SYMPTOMS

Antibiotic treatment

Given that most cases of TD are caused by bacterial pathogens, antibiotics are considered the mainstay of treatment. Concerns about the ill effects of antibiotic use in the case of enterohemorrhagic E coli (EHEC O157:H7) can be allayed because this strain is rarely a cause of TD.9

Consider local resistance patterns and risk for invasive infection. Which antibiotic to recommend is governed by the antibiotic resistance patterns prevalent in the travel destinations and by the risk for infection by invasive pathogens. Invasive TD is generally caused by Campylobacter, Shigella, or Salmonella and manifests clinically with bloody diarrhea, fever, or both. Rifaximin at a dose of 200 mg orally three times daily is effective for noninvasive TD.31,32

However, travelers who develop invasive TD need an alternative to rifaximin. (Those who advocate reserving antibiotic treatment only for invasive diarrhea will not see a role for rifaximin in the first place.) In most invasive cases, a fluoroquinolone will suffice.10-12,19,32 However, increasing prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species has been reported in South and Southeast Asia. In those locations, azithromycin is an effective alternative, albeit with risk for nausea.33

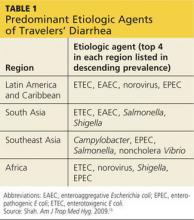

Table 2 provides details of recommended antibiotic dosages for adults and children. The duration of treatment is generally one day unless symptoms persist, in which case a three-day course is recommended.10-12,19,32 If the traveler experiences persistent, new, or worsening symptoms beyond this point, immediate evaluation by a clinician is required.

Nonantibiotic treatment

The antimotility agent loperamide is well established as an antidiarrheal agent. Its effective and safe use as an adjunct to antibiotics in the treatment of TD has been demonstrated in several studies.10-12,19,32,34 It is generally not used to treat children with TD.9

No other nonantibiotic treatment for TD has significant guideline or clinical trial support. Bismuth subsalicylate can be helpful in treating TD,35 but it is not often recommended because of the aforementioned adherence difficulties and because antibiotics and loperamide are effective.

Oral rehydration is usually a mainstay of treating gastrointestinal disease among infants and children. However, it, too, has a limited role in cases of TD, because dehydration is not usually a significant part of the clinical presentation—perhaps because vomiting is not often prominent.

Advice regarding safe food and beverage choices is essential for the patient and her children. Despite the increased risk for TD due to her history and her use of the immunosuppressant methotrexate, she decides not to pursue antibiotic prophylaxis. Bismuth is also contraindicated because of the methotrexate. Her teenage daughter declines bismuth prophylaxis, and her toddler is too young for it.

The patient does accept a prescription for azithromycin for herself and her daughters, in case they experience TD. This choice is appropriate given the destination of India and concern about Campylobacter resistance to fluoroquinolones. You also recommend loperamide for use by the mother and older child, in conjunction with the antibiotic.

Two weeks after their trip abroad, the travelers return for an office visit. On the trip, the mother and toddler experienced diarrhea, which responded well to your recommended management. The older child was well during the trip, but she developed diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia one week after returning to the US. These symptoms have persisted despite a three-day course of azithromycin and loperamide.

Continued on next page >>

POSTTRAVEL EVALUATION

TD generally occurs within one to two weeks of arrival at the travel destination and usually lasts no longer than four to five days.19 This scenario is typical of a bacterial infection. When it occurs later or lasts longer (or both), consider several alternative possibilities.19,36

First, the likelihood of a protozoal parasitic infection is increased. Although giardiasis is most likely, other protozoa such as Entamoeba, Cyclospora, Isospora, and Cryptosporidium are also possibilities. Second, if diarrhea persists, it might be due, not to continued infection, but to a self-limited postinfectious enteropathy or to PI-IBS. Third, TD is known to precipitate the clinical manifestation of underlying gastrointestinal disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, or even cancer.37

With an atypical disease course, it’s advisable to send three stool samples for laboratory evaluation for ova and parasites and for antigen assays for Giardia. If results of these tests are negative, given the difficulty inherent in diagnosing Giardia, consider empiric treatment with metronidazole in lieu of duodenal sampling.36 If the diarrhea persists, investigate serologic markers for celiac disease and IBD. If these are not revealing, referral for colonoscopy is prudent.

The teenager’s three stool samples were negative for ova and parasites and for Giardia antigen. Following empiric treatment with oral metronidazole 250 mg, three times daily for seven days, the diarrhea resolved.

References on next page >>

REFERENCES

1. Hill DR. Occurrence and self-treatment of diarrhea in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000; 62:585-589.

2. Greenwood Z, Black J, Weld L, et al for the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Gastrointestinal infection among international travelers globally. J Travel Med. 2008;15:221-228.

3. DuPont HL. Systematic review: the epidemiology and clinical features of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:187-196.

4. Steffen R, Tornieporth N, Clemens SA, et al. Epidemiology of travelers’ diarrhea: details of a global survey. J Travel Med. 2004;11:231-237.

5. de la Cabada Bauche J, DuPont HL. New developments in traveler’s diarrhea. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:88-95.

6. Cabada MM, White AC. Travelers’ diarrhea: an update on susceptibility, prevention, and treatment. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:473-479.

7. Ericsson CD. Travellers with pre-existing medical conditions. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:181-188.

8. Cabada MM, Maldonado F, Quispe W, et al. Risk factors associated with diarrhea among international visitors to Cuzco, Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:968-972.

9. Mackell S. Traveler’s diarrhea in the pediatric population: etiology and impact. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(suppl 8):S547-S552.

10. Hill DR, Ericsson CD, Pearson RD, et al. The practice of travel medicine: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1499-1539.

11. Connor BA. Travelers’ diarrhea. wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/ 2012/chapter-2-the-pre-travel-consultation/travelers-diarrhea.htm. Accessed April 22, 2014.

12. Advice for travelers. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2012;10:45-56.

13. Shlim DR. Looking for evidence that personal hygiene precautions prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(suppl 8):S531-S535.

14. Laverone E, Boccalini S, Bechini A, et al. Travelers’ compliance to prophylactic measures and behavior during stay abroad: results of a retrospective study of subjects returning to a travel medicine center in Italy. J Travel Med. 2006;13:338-344.

15. Ashley DV, Walters C, Dockery-Brown C, et al. Interventions to prevent and control food-borne diseases associated with a reduction in traveler’s diarrhea in tourists to Jamaica. J Travel Med. 2004;11:364-367.

16. Shah N, DuPont HL, Ramsey DJ. Global etiology of travelers’ diarrhea: systematic review from 1973 to the present. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:609-614.

17. Riddle MS, Sanders JW, Putnam SD, et al. Incidence, etiology, and impact of diarrhea among long-term travelers (US military and similar populations): a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:891-900.

18. Koo HL, Ajami NJ, Jiang ZD, et al. Noroviruses as a cause of diarrhea in travelers to Guatemala, India, and Mexico. J Clin Microbiol. 2010; 48:1673-1676.

19. Hill DR, Ryan ET. Management of travellers’ diarrhoea. BMJ. 2008; 337:863-867.

20. Rendi-Wagner P, Kollaritsch H. Drug prophylaxis for travelers’ diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:628-633.

21. Pimentel M, Riddle MS. Prevention of traveler’s diarrhea: a call to reconvene. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:151-152.

22. DuPont HL. Systematic review: prevention of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:741-751.

23. Wang M, Szucs TD, Steffen R. Economic aspects of travelers’ diarrhea.

J Travel Med. 2008;15:110-118.

24. Neal KR, Barker L, Spiller RC. Prognosis in post-infective irritable bowel syndrome: a six year follow up study. Gut. 2002;51:410-413.

25. Tornblom H, Holmvall P, Svenungsson B, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms after infectious diarrhea: a five-year follow-up in a Swedish cohort of adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:461-464.

26. DuPont HL, Jiang ZD, Okhuysen PC, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin to prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:805-812.

27. Taylor DN, McKenzie R, Durbin A, et al. Rifaximin, a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic, prevents shigellosis after experimental challenge. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1283-1288.

28. Sazawal S, Hiremath G, Dhingra U, et al. Efficacy of probiotics in prevention of acute diarrhoea: a meta-analysis of masked, randomised, placebo-controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:374-382.

29. Bri V, Buffet P, Genty S, et al. Absence of efficacy of nonviable Lactobacillus acidophilus for the prevention of traveler’s diarrhea: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1170-1175.

30. Hill DR, Ford L, Lalloo DG. Oral cholera vaccines—use in clinical practice. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:361-373.

31. Taylor DN, Bourgeois AL, Ericsson CD, et al. A randomized double-blind, multicenter study of rifaximin compared with placebo and with ciprofloxacin in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:1060-1066.

32. DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Farthing MJG, et al. Expert review of the evidence base for self-therapy of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2009; 16:161-171.

33. Tribble DR, Sanders JW, Pang LW, et al. Traveler’s diarrhea in Thailand: randomized, double-blind trial comparing single-dose and 3-day azithromycin-based regimens with a 3-day levofloxacin regimen. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:338-346.

34. Riddle MS, Arnold S, Tribble DR. Effect of adjunctive loperamide in combination with antibiotics on treatment outcomes in travelers’ diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 47:1007-1014.

35. Steffen R. Worldwide efficacy of bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(suppl 1):S80-S86.

36. Connor BA. Persistent travelers’ diarrhea. wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/

yellowbook/2012/chapter-5-post-travel-evaluation/persistent-travelers-diarrhea.htm. Accessed April 22 2014.

37. Landzberg BR, Connor BA. Persistent diarrhea in the returning traveler: think beyond persistent infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:

112-114.

A 40-year-old woman, a childhood immigrant from India, is seeking advice regarding her upcoming two-week trip to Mumbai. She is taking her two children, ages 16 years and 16 months, to visit their grandparents for the first time. She has made this trip alone a few times and has invariably experienced short bouts of self-limited diarrheal illness. She wonders what she might do to prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Her only medical problem is rheumatoid arthritis, which has been well controlled with methotrexate. Her children are healthy. What would you recommend?

Recommendations regarding travelers’ diarrhea (TD) address prevention and management. Prevention encompasses advice about personal behaviors and the use of chemoprophylaxis (antimicrobial and nonantimicrobial) and vaccinations. Since international travelers are known to treat themselves for diarrheal illnesses during their trips,1 recommendations regarding management should assume self-treatment and include the use of both antibiotic and nonantibiotic remedies. Pretravel recommendations will of course be most effective if they account for the individual’s risk for TD.

TD RISK

TD is generally defined as the passage of three or more loose stools in a 24-hour period, with associated symptoms of enteric infection (eg, fever, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal cramping). Defined in this manner, TD is thought to occur in 60% to 70% of individuals who travel from developed countries to less-developed countries.2-4 Risk for TD is influenced both by intrinsic personal factors and by factors specific to the trip.

Personal risk factors

Individual variation in susceptibility to TD might result from a genetic predisposition arising from single nucleotide polymorphisms governing various inflammatory marker proteins.5 A history of multiple episodes of TD, especially if fellow travelers were spared, can suggest this kind of individual susceptibility. Other factors that increase vulnerability to TD are immunodeficiency, achlorhydric states such as atrophic gastritis, and chronic use of proton pump inhibitors.6,7 However, the trip itself is much more important in assessing risk for TD.

Trip-related risk factors

The destination. The most salient risk factor for TD is the geographic destination. Regions of the world can be divided into TD risk strata2:

• Very high: South Asia

• High: South America, Sub-Saharan Africa

• Medium: Central America, Mexico, Caribbean, Middle East, North Africa, Southeast Asia, Oceania

• Low: Europe, North America (excluding Mexico), Australasia, Northeast Asia

Particularly notable countries, in descending order of risk, are Nepal, India, Myanmar, Bolivia, Sri Lanka, Ecuador, Peru, Kenya, and Guatemala.2

Dietary choices. Additionally, since travelers acquire TD by ingesting food or beverages contaminated with pathogenic fecal microbes, dietary behaviors during the trip affect their susceptibility. At least risk are business travelers and tourists who confine their activities to more affluent settings in which food and beverages are prepared and stored hygienically.1,4,8,9 At greater risk are travelers who immerse themselves in local culture, visiting locations that are more impoverished and not as well equipped with sanitation systems, especially if their stay lasts at least two to three weeks.1,4,8,9

Also, the older a traveler is, the lower his or her risk for TD.1,9 An exception to this might be infants whose diet consists solely of breast milk or formula prepared under sanitary conditions.

Continued on next page >>

TD PREVENTION

Emphasize food and beverage precautions

It might be reasonable to expect that travelers who are circumspect about their food and beverage choices on trips will be able to avoid TD. Indeed, this is the basis for the aphorism, “Boil it, peel it, or forget it.” Guidelines routinely recommend that travelers restrict their selection of foods to those that have been well cooked and are served while still very hot, as well as to fruits and vegetables that they peel themselves. Likewise, they should drink only beverages that have been boiled or are in sealed bottles or under carbonation and served without ice.10-12

Many travelers might find these recommendations too restrictive to follow faithfully. Moreover, studies suggest it may not be possible for even the most assiduous traveler to fully avoid the risk for TD.13,14 The hygienic characteristics of the travel destination may be more determinative, as illustrated by the successful reduction of TD rates in Jamaica by improving sanitation in tourist resorts.15

Antibiotic chemoprophylaxis: A debated practice with limited consensus

The etiologic agents of TD are multiple and vary somewhat in predominance according to geographic region.3,16,17 Table 1 depicts variance by region. The most common pathogens are strains of the bacterium Escherichia coli, particularly enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteroaggregative, and enteropathogenic strains.16 Other bacteria of importance are Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella. Viruses, particularly norovirus (notably connected with cruise ships), can also cause TD, although it is implicated in no more than 17% of cases.18 Parasitic pathogens are even less common causes of TD (4% to 10%) and mainly involve the protozoa, Giardia lamblia, and, to a lesser extent, Entamoeba histolytica and Cryptosporidium.

Although some pathogens often have a characteristic presentation—such as frothy, greasy diarrhea in the case of G lamblia—in general, they cannot be reliably distinguished from one another clinically. Notably, up to 50% of stool samples from TD patients do not yield any pathogen,16 raising the suspicion that current diagnostic technology is not sufficiently sensitive to routinely identify certain bacteria.

There is no consensus on recommending antibiotic chemoprophylaxis against TD.

Opponents of this practice point out that TD is generally a brief (three to five days), self-limited illness.10-12,19,20 Moreover, concerns about antibiotic resistance have come to pass. Previously used agents (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline) are no longer effective in preventing or treating TD. In addition, antibiotic use carries the risk for allergic reactions, as well as other adverse effects including (ironically) the development of antibiotic-associated and Clostridium difficile diarrhea.

Proponents of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis point to its demonstrated efficacy in reducing the risk for TD by 4% to 40%.11,21,22 They also argue that at least 20% to 25% of travelers who get TD must significantly curtail their activities for a day or more.1,23 This change in travel plans is associated not only with significant personal loss but also imposes a financial burden.23 Furthermore, TD is known to have longer-term effects. Up to 10% of those affected develop postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS) that can last for five or six years.21,22,24,25 It is not known, however, whether the use of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis significantly reduces the incidence of PI-IBS.

Finally, the luminal antibiotic rifaximin, nonabsorbable as it is, is very well tolerated and holds promise for not inciting antibiotic resistance.22 However, while its efficacy in preventing TD has been demonstrated in various settings,22,26,27 it is not approved by the FDA for this indication. Also, concerns persist that it might not be effective in preventing TD caused by invasive pathogens.19

Indications on which all agree. Even opponents of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis grant that it is probably warranted for two groups of travelers.10-12 The first is those whose trip schedule is of such importance that any deviation would be intolerable. The second is travelers with comorbidities that would render them at high risk for serious inconvenience or illness if they developed TD. Examples of the latter include patients with enterostomies, mobility impairments, immune suppression, inflammatory bowel disease, and renal or metabolic diseases.

Chemoprophylaxis regimens. If you prescribe an antibiotic prophylactically, consider daily doses of a fluoroquinolone (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily, not twice daily as for treatment) or rifaximin 200 mg orally once or twice a day, for no longer than two to three weeks.10

Nonantimicrobial chemoprophylaxis

Bismuth subsalicylate has reduced the incidence of TD from 40% to just 14% when taken in doses of two chewable tablets or 60 mL of liquid four times daily.11,19,22 However, the dosing frequency can hinder adherence. Moreover, the relatively high doses required raise the risk for adverse drug reactions, such as blackening of the tongue and stool, nausea, constipation, Reye syndrome (in children younger than 12), and possibly tinnitus. The salicylate component of the drug poses a threat to patients with aspirin allergy or renal disease and those taking anticoagulants. Drug interactions with probenecid and methotrexate are also possible. Bismuth is not recommended for use for longer than three weeks, or for children younger than 3 years or pregnant women in their third trimester.

Probiotics such as Lactobacillus and Saccharomyces are among the other nonantimicrobial chemoprophylaxis agents. These preparations of bacteria and fungi are marketed either singly or in blends of varying composition and proportion. The evidence is divided on their efficacy, and even though some meta-analyses have concluded probiotics such as Saccharomyces boulardii are useful in preventing TD, endorsement in clinical guidelines is muted.10-12,28-30

Immunizations have limited value so far

Natural immunity to E coli gastrointestinal infection among indigenous people in less developed countries has raised the possibility of a role for vaccines in preventing TD. Some strains of ETEC produce a heat-labile toxin (LT) that bears significant resemblance to the toxin produced by Vibrio cholerae. Therefore, the oral cholera vaccine has been marketed outside the United States for the prevention of TD.19,22 However, only ≤ 7% of TD cases worldwide would be prevented by routine use of this vaccine.31 A transdermal LT vaccine, which involves the antigen-presenting Langerhans cells in the superficial skin layers, is promising but not yet available for routine use.19,22

Continued on next page >>

TREATING TD AND ASSOCIATED SYMPTOMS

Antibiotic treatment

Given that most cases of TD are caused by bacterial pathogens, antibiotics are considered the mainstay of treatment. Concerns about the ill effects of antibiotic use in the case of enterohemorrhagic E coli (EHEC O157:H7) can be allayed because this strain is rarely a cause of TD.9

Consider local resistance patterns and risk for invasive infection. Which antibiotic to recommend is governed by the antibiotic resistance patterns prevalent in the travel destinations and by the risk for infection by invasive pathogens. Invasive TD is generally caused by Campylobacter, Shigella, or Salmonella and manifests clinically with bloody diarrhea, fever, or both. Rifaximin at a dose of 200 mg orally three times daily is effective for noninvasive TD.31,32

However, travelers who develop invasive TD need an alternative to rifaximin. (Those who advocate reserving antibiotic treatment only for invasive diarrhea will not see a role for rifaximin in the first place.) In most invasive cases, a fluoroquinolone will suffice.10-12,19,32 However, increasing prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species has been reported in South and Southeast Asia. In those locations, azithromycin is an effective alternative, albeit with risk for nausea.33

Table 2 provides details of recommended antibiotic dosages for adults and children. The duration of treatment is generally one day unless symptoms persist, in which case a three-day course is recommended.10-12,19,32 If the traveler experiences persistent, new, or worsening symptoms beyond this point, immediate evaluation by a clinician is required.

Nonantibiotic treatment

The antimotility agent loperamide is well established as an antidiarrheal agent. Its effective and safe use as an adjunct to antibiotics in the treatment of TD has been demonstrated in several studies.10-12,19,32,34 It is generally not used to treat children with TD.9

No other nonantibiotic treatment for TD has significant guideline or clinical trial support. Bismuth subsalicylate can be helpful in treating TD,35 but it is not often recommended because of the aforementioned adherence difficulties and because antibiotics and loperamide are effective.

Oral rehydration is usually a mainstay of treating gastrointestinal disease among infants and children. However, it, too, has a limited role in cases of TD, because dehydration is not usually a significant part of the clinical presentation—perhaps because vomiting is not often prominent.

Advice regarding safe food and beverage choices is essential for the patient and her children. Despite the increased risk for TD due to her history and her use of the immunosuppressant methotrexate, she decides not to pursue antibiotic prophylaxis. Bismuth is also contraindicated because of the methotrexate. Her teenage daughter declines bismuth prophylaxis, and her toddler is too young for it.

The patient does accept a prescription for azithromycin for herself and her daughters, in case they experience TD. This choice is appropriate given the destination of India and concern about Campylobacter resistance to fluoroquinolones. You also recommend loperamide for use by the mother and older child, in conjunction with the antibiotic.

Two weeks after their trip abroad, the travelers return for an office visit. On the trip, the mother and toddler experienced diarrhea, which responded well to your recommended management. The older child was well during the trip, but she developed diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia one week after returning to the US. These symptoms have persisted despite a three-day course of azithromycin and loperamide.

Continued on next page >>

POSTTRAVEL EVALUATION

TD generally occurs within one to two weeks of arrival at the travel destination and usually lasts no longer than four to five days.19 This scenario is typical of a bacterial infection. When it occurs later or lasts longer (or both), consider several alternative possibilities.19,36

First, the likelihood of a protozoal parasitic infection is increased. Although giardiasis is most likely, other protozoa such as Entamoeba, Cyclospora, Isospora, and Cryptosporidium are also possibilities. Second, if diarrhea persists, it might be due, not to continued infection, but to a self-limited postinfectious enteropathy or to PI-IBS. Third, TD is known to precipitate the clinical manifestation of underlying gastrointestinal disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, or even cancer.37

With an atypical disease course, it’s advisable to send three stool samples for laboratory evaluation for ova and parasites and for antigen assays for Giardia. If results of these tests are negative, given the difficulty inherent in diagnosing Giardia, consider empiric treatment with metronidazole in lieu of duodenal sampling.36 If the diarrhea persists, investigate serologic markers for celiac disease and IBD. If these are not revealing, referral for colonoscopy is prudent.

The teenager’s three stool samples were negative for ova and parasites and for Giardia antigen. Following empiric treatment with oral metronidazole 250 mg, three times daily for seven days, the diarrhea resolved.

References on next page >>

REFERENCES

1. Hill DR. Occurrence and self-treatment of diarrhea in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000; 62:585-589.

2. Greenwood Z, Black J, Weld L, et al for the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Gastrointestinal infection among international travelers globally. J Travel Med. 2008;15:221-228.

3. DuPont HL. Systematic review: the epidemiology and clinical features of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:187-196.

4. Steffen R, Tornieporth N, Clemens SA, et al. Epidemiology of travelers’ diarrhea: details of a global survey. J Travel Med. 2004;11:231-237.

5. de la Cabada Bauche J, DuPont HL. New developments in traveler’s diarrhea. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:88-95.

6. Cabada MM, White AC. Travelers’ diarrhea: an update on susceptibility, prevention, and treatment. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:473-479.

7. Ericsson CD. Travellers with pre-existing medical conditions. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:181-188.

8. Cabada MM, Maldonado F, Quispe W, et al. Risk factors associated with diarrhea among international visitors to Cuzco, Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:968-972.

9. Mackell S. Traveler’s diarrhea in the pediatric population: etiology and impact. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(suppl 8):S547-S552.

10. Hill DR, Ericsson CD, Pearson RD, et al. The practice of travel medicine: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1499-1539.

11. Connor BA. Travelers’ diarrhea. wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/ 2012/chapter-2-the-pre-travel-consultation/travelers-diarrhea.htm. Accessed April 22, 2014.

12. Advice for travelers. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2012;10:45-56.

13. Shlim DR. Looking for evidence that personal hygiene precautions prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(suppl 8):S531-S535.

14. Laverone E, Boccalini S, Bechini A, et al. Travelers’ compliance to prophylactic measures and behavior during stay abroad: results of a retrospective study of subjects returning to a travel medicine center in Italy. J Travel Med. 2006;13:338-344.

15. Ashley DV, Walters C, Dockery-Brown C, et al. Interventions to prevent and control food-borne diseases associated with a reduction in traveler’s diarrhea in tourists to Jamaica. J Travel Med. 2004;11:364-367.

16. Shah N, DuPont HL, Ramsey DJ. Global etiology of travelers’ diarrhea: systematic review from 1973 to the present. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:609-614.

17. Riddle MS, Sanders JW, Putnam SD, et al. Incidence, etiology, and impact of diarrhea among long-term travelers (US military and similar populations): a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:891-900.

18. Koo HL, Ajami NJ, Jiang ZD, et al. Noroviruses as a cause of diarrhea in travelers to Guatemala, India, and Mexico. J Clin Microbiol. 2010; 48:1673-1676.

19. Hill DR, Ryan ET. Management of travellers’ diarrhoea. BMJ. 2008; 337:863-867.

20. Rendi-Wagner P, Kollaritsch H. Drug prophylaxis for travelers’ diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:628-633.

21. Pimentel M, Riddle MS. Prevention of traveler’s diarrhea: a call to reconvene. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:151-152.

22. DuPont HL. Systematic review: prevention of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:741-751.

23. Wang M, Szucs TD, Steffen R. Economic aspects of travelers’ diarrhea.

J Travel Med. 2008;15:110-118.

24. Neal KR, Barker L, Spiller RC. Prognosis in post-infective irritable bowel syndrome: a six year follow up study. Gut. 2002;51:410-413.

25. Tornblom H, Holmvall P, Svenungsson B, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms after infectious diarrhea: a five-year follow-up in a Swedish cohort of adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:461-464.

26. DuPont HL, Jiang ZD, Okhuysen PC, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin to prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:805-812.

27. Taylor DN, McKenzie R, Durbin A, et al. Rifaximin, a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic, prevents shigellosis after experimental challenge. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1283-1288.

28. Sazawal S, Hiremath G, Dhingra U, et al. Efficacy of probiotics in prevention of acute diarrhoea: a meta-analysis of masked, randomised, placebo-controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:374-382.

29. Bri V, Buffet P, Genty S, et al. Absence of efficacy of nonviable Lactobacillus acidophilus for the prevention of traveler’s diarrhea: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1170-1175.

30. Hill DR, Ford L, Lalloo DG. Oral cholera vaccines—use in clinical practice. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:361-373.

31. Taylor DN, Bourgeois AL, Ericsson CD, et al. A randomized double-blind, multicenter study of rifaximin compared with placebo and with ciprofloxacin in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:1060-1066.

32. DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Farthing MJG, et al. Expert review of the evidence base for self-therapy of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2009; 16:161-171.

33. Tribble DR, Sanders JW, Pang LW, et al. Traveler’s diarrhea in Thailand: randomized, double-blind trial comparing single-dose and 3-day azithromycin-based regimens with a 3-day levofloxacin regimen. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:338-346.

34. Riddle MS, Arnold S, Tribble DR. Effect of adjunctive loperamide in combination with antibiotics on treatment outcomes in travelers’ diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 47:1007-1014.

35. Steffen R. Worldwide efficacy of bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(suppl 1):S80-S86.

36. Connor BA. Persistent travelers’ diarrhea. wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/

yellowbook/2012/chapter-5-post-travel-evaluation/persistent-travelers-diarrhea.htm. Accessed April 22 2014.

37. Landzberg BR, Connor BA. Persistent diarrhea in the returning traveler: think beyond persistent infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:

112-114.

A 40-year-old woman, a childhood immigrant from India, is seeking advice regarding her upcoming two-week trip to Mumbai. She is taking her two children, ages 16 years and 16 months, to visit their grandparents for the first time. She has made this trip alone a few times and has invariably experienced short bouts of self-limited diarrheal illness. She wonders what she might do to prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Her only medical problem is rheumatoid arthritis, which has been well controlled with methotrexate. Her children are healthy. What would you recommend?

Recommendations regarding travelers’ diarrhea (TD) address prevention and management. Prevention encompasses advice about personal behaviors and the use of chemoprophylaxis (antimicrobial and nonantimicrobial) and vaccinations. Since international travelers are known to treat themselves for diarrheal illnesses during their trips,1 recommendations regarding management should assume self-treatment and include the use of both antibiotic and nonantibiotic remedies. Pretravel recommendations will of course be most effective if they account for the individual’s risk for TD.

TD RISK

TD is generally defined as the passage of three or more loose stools in a 24-hour period, with associated symptoms of enteric infection (eg, fever, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal cramping). Defined in this manner, TD is thought to occur in 60% to 70% of individuals who travel from developed countries to less-developed countries.2-4 Risk for TD is influenced both by intrinsic personal factors and by factors specific to the trip.

Personal risk factors

Individual variation in susceptibility to TD might result from a genetic predisposition arising from single nucleotide polymorphisms governing various inflammatory marker proteins.5 A history of multiple episodes of TD, especially if fellow travelers were spared, can suggest this kind of individual susceptibility. Other factors that increase vulnerability to TD are immunodeficiency, achlorhydric states such as atrophic gastritis, and chronic use of proton pump inhibitors.6,7 However, the trip itself is much more important in assessing risk for TD.

Trip-related risk factors

The destination. The most salient risk factor for TD is the geographic destination. Regions of the world can be divided into TD risk strata2:

• Very high: South Asia

• High: South America, Sub-Saharan Africa

• Medium: Central America, Mexico, Caribbean, Middle East, North Africa, Southeast Asia, Oceania

• Low: Europe, North America (excluding Mexico), Australasia, Northeast Asia

Particularly notable countries, in descending order of risk, are Nepal, India, Myanmar, Bolivia, Sri Lanka, Ecuador, Peru, Kenya, and Guatemala.2

Dietary choices. Additionally, since travelers acquire TD by ingesting food or beverages contaminated with pathogenic fecal microbes, dietary behaviors during the trip affect their susceptibility. At least risk are business travelers and tourists who confine their activities to more affluent settings in which food and beverages are prepared and stored hygienically.1,4,8,9 At greater risk are travelers who immerse themselves in local culture, visiting locations that are more impoverished and not as well equipped with sanitation systems, especially if their stay lasts at least two to three weeks.1,4,8,9

Also, the older a traveler is, the lower his or her risk for TD.1,9 An exception to this might be infants whose diet consists solely of breast milk or formula prepared under sanitary conditions.

Continued on next page >>

TD PREVENTION

Emphasize food and beverage precautions

It might be reasonable to expect that travelers who are circumspect about their food and beverage choices on trips will be able to avoid TD. Indeed, this is the basis for the aphorism, “Boil it, peel it, or forget it.” Guidelines routinely recommend that travelers restrict their selection of foods to those that have been well cooked and are served while still very hot, as well as to fruits and vegetables that they peel themselves. Likewise, they should drink only beverages that have been boiled or are in sealed bottles or under carbonation and served without ice.10-12

Many travelers might find these recommendations too restrictive to follow faithfully. Moreover, studies suggest it may not be possible for even the most assiduous traveler to fully avoid the risk for TD.13,14 The hygienic characteristics of the travel destination may be more determinative, as illustrated by the successful reduction of TD rates in Jamaica by improving sanitation in tourist resorts.15

Antibiotic chemoprophylaxis: A debated practice with limited consensus

The etiologic agents of TD are multiple and vary somewhat in predominance according to geographic region.3,16,17 Table 1 depicts variance by region. The most common pathogens are strains of the bacterium Escherichia coli, particularly enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteroaggregative, and enteropathogenic strains.16 Other bacteria of importance are Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella. Viruses, particularly norovirus (notably connected with cruise ships), can also cause TD, although it is implicated in no more than 17% of cases.18 Parasitic pathogens are even less common causes of TD (4% to 10%) and mainly involve the protozoa, Giardia lamblia, and, to a lesser extent, Entamoeba histolytica and Cryptosporidium.

Although some pathogens often have a characteristic presentation—such as frothy, greasy diarrhea in the case of G lamblia—in general, they cannot be reliably distinguished from one another clinically. Notably, up to 50% of stool samples from TD patients do not yield any pathogen,16 raising the suspicion that current diagnostic technology is not sufficiently sensitive to routinely identify certain bacteria.

There is no consensus on recommending antibiotic chemoprophylaxis against TD.

Opponents of this practice point out that TD is generally a brief (three to five days), self-limited illness.10-12,19,20 Moreover, concerns about antibiotic resistance have come to pass. Previously used agents (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline) are no longer effective in preventing or treating TD. In addition, antibiotic use carries the risk for allergic reactions, as well as other adverse effects including (ironically) the development of antibiotic-associated and Clostridium difficile diarrhea.

Proponents of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis point to its demonstrated efficacy in reducing the risk for TD by 4% to 40%.11,21,22 They also argue that at least 20% to 25% of travelers who get TD must significantly curtail their activities for a day or more.1,23 This change in travel plans is associated not only with significant personal loss but also imposes a financial burden.23 Furthermore, TD is known to have longer-term effects. Up to 10% of those affected develop postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS) that can last for five or six years.21,22,24,25 It is not known, however, whether the use of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis significantly reduces the incidence of PI-IBS.

Finally, the luminal antibiotic rifaximin, nonabsorbable as it is, is very well tolerated and holds promise for not inciting antibiotic resistance.22 However, while its efficacy in preventing TD has been demonstrated in various settings,22,26,27 it is not approved by the FDA for this indication. Also, concerns persist that it might not be effective in preventing TD caused by invasive pathogens.19

Indications on which all agree. Even opponents of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis grant that it is probably warranted for two groups of travelers.10-12 The first is those whose trip schedule is of such importance that any deviation would be intolerable. The second is travelers with comorbidities that would render them at high risk for serious inconvenience or illness if they developed TD. Examples of the latter include patients with enterostomies, mobility impairments, immune suppression, inflammatory bowel disease, and renal or metabolic diseases.

Chemoprophylaxis regimens. If you prescribe an antibiotic prophylactically, consider daily doses of a fluoroquinolone (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily, not twice daily as for treatment) or rifaximin 200 mg orally once or twice a day, for no longer than two to three weeks.10

Nonantimicrobial chemoprophylaxis

Bismuth subsalicylate has reduced the incidence of TD from 40% to just 14% when taken in doses of two chewable tablets or 60 mL of liquid four times daily.11,19,22 However, the dosing frequency can hinder adherence. Moreover, the relatively high doses required raise the risk for adverse drug reactions, such as blackening of the tongue and stool, nausea, constipation, Reye syndrome (in children younger than 12), and possibly tinnitus. The salicylate component of the drug poses a threat to patients with aspirin allergy or renal disease and those taking anticoagulants. Drug interactions with probenecid and methotrexate are also possible. Bismuth is not recommended for use for longer than three weeks, or for children younger than 3 years or pregnant women in their third trimester.

Probiotics such as Lactobacillus and Saccharomyces are among the other nonantimicrobial chemoprophylaxis agents. These preparations of bacteria and fungi are marketed either singly or in blends of varying composition and proportion. The evidence is divided on their efficacy, and even though some meta-analyses have concluded probiotics such as Saccharomyces boulardii are useful in preventing TD, endorsement in clinical guidelines is muted.10-12,28-30

Immunizations have limited value so far

Natural immunity to E coli gastrointestinal infection among indigenous people in less developed countries has raised the possibility of a role for vaccines in preventing TD. Some strains of ETEC produce a heat-labile toxin (LT) that bears significant resemblance to the toxin produced by Vibrio cholerae. Therefore, the oral cholera vaccine has been marketed outside the United States for the prevention of TD.19,22 However, only ≤ 7% of TD cases worldwide would be prevented by routine use of this vaccine.31 A transdermal LT vaccine, which involves the antigen-presenting Langerhans cells in the superficial skin layers, is promising but not yet available for routine use.19,22

Continued on next page >>

TREATING TD AND ASSOCIATED SYMPTOMS

Antibiotic treatment

Given that most cases of TD are caused by bacterial pathogens, antibiotics are considered the mainstay of treatment. Concerns about the ill effects of antibiotic use in the case of enterohemorrhagic E coli (EHEC O157:H7) can be allayed because this strain is rarely a cause of TD.9

Consider local resistance patterns and risk for invasive infection. Which antibiotic to recommend is governed by the antibiotic resistance patterns prevalent in the travel destinations and by the risk for infection by invasive pathogens. Invasive TD is generally caused by Campylobacter, Shigella, or Salmonella and manifests clinically with bloody diarrhea, fever, or both. Rifaximin at a dose of 200 mg orally three times daily is effective for noninvasive TD.31,32

However, travelers who develop invasive TD need an alternative to rifaximin. (Those who advocate reserving antibiotic treatment only for invasive diarrhea will not see a role for rifaximin in the first place.) In most invasive cases, a fluoroquinolone will suffice.10-12,19,32 However, increasing prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species has been reported in South and Southeast Asia. In those locations, azithromycin is an effective alternative, albeit with risk for nausea.33

Table 2 provides details of recommended antibiotic dosages for adults and children. The duration of treatment is generally one day unless symptoms persist, in which case a three-day course is recommended.10-12,19,32 If the traveler experiences persistent, new, or worsening symptoms beyond this point, immediate evaluation by a clinician is required.

Nonantibiotic treatment

The antimotility agent loperamide is well established as an antidiarrheal agent. Its effective and safe use as an adjunct to antibiotics in the treatment of TD has been demonstrated in several studies.10-12,19,32,34 It is generally not used to treat children with TD.9

No other nonantibiotic treatment for TD has significant guideline or clinical trial support. Bismuth subsalicylate can be helpful in treating TD,35 but it is not often recommended because of the aforementioned adherence difficulties and because antibiotics and loperamide are effective.

Oral rehydration is usually a mainstay of treating gastrointestinal disease among infants and children. However, it, too, has a limited role in cases of TD, because dehydration is not usually a significant part of the clinical presentation—perhaps because vomiting is not often prominent.

Advice regarding safe food and beverage choices is essential for the patient and her children. Despite the increased risk for TD due to her history and her use of the immunosuppressant methotrexate, she decides not to pursue antibiotic prophylaxis. Bismuth is also contraindicated because of the methotrexate. Her teenage daughter declines bismuth prophylaxis, and her toddler is too young for it.

The patient does accept a prescription for azithromycin for herself and her daughters, in case they experience TD. This choice is appropriate given the destination of India and concern about Campylobacter resistance to fluoroquinolones. You also recommend loperamide for use by the mother and older child, in conjunction with the antibiotic.

Two weeks after their trip abroad, the travelers return for an office visit. On the trip, the mother and toddler experienced diarrhea, which responded well to your recommended management. The older child was well during the trip, but she developed diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia one week after returning to the US. These symptoms have persisted despite a three-day course of azithromycin and loperamide.

Continued on next page >>

POSTTRAVEL EVALUATION

TD generally occurs within one to two weeks of arrival at the travel destination and usually lasts no longer than four to five days.19 This scenario is typical of a bacterial infection. When it occurs later or lasts longer (or both), consider several alternative possibilities.19,36

First, the likelihood of a protozoal parasitic infection is increased. Although giardiasis is most likely, other protozoa such as Entamoeba, Cyclospora, Isospora, and Cryptosporidium are also possibilities. Second, if diarrhea persists, it might be due, not to continued infection, but to a self-limited postinfectious enteropathy or to PI-IBS. Third, TD is known to precipitate the clinical manifestation of underlying gastrointestinal disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, or even cancer.37

With an atypical disease course, it’s advisable to send three stool samples for laboratory evaluation for ova and parasites and for antigen assays for Giardia. If results of these tests are negative, given the difficulty inherent in diagnosing Giardia, consider empiric treatment with metronidazole in lieu of duodenal sampling.36 If the diarrhea persists, investigate serologic markers for celiac disease and IBD. If these are not revealing, referral for colonoscopy is prudent.

The teenager’s three stool samples were negative for ova and parasites and for Giardia antigen. Following empiric treatment with oral metronidazole 250 mg, three times daily for seven days, the diarrhea resolved.

References on next page >>

REFERENCES

1. Hill DR. Occurrence and self-treatment of diarrhea in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000; 62:585-589.

2. Greenwood Z, Black J, Weld L, et al for the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Gastrointestinal infection among international travelers globally. J Travel Med. 2008;15:221-228.

3. DuPont HL. Systematic review: the epidemiology and clinical features of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:187-196.

4. Steffen R, Tornieporth N, Clemens SA, et al. Epidemiology of travelers’ diarrhea: details of a global survey. J Travel Med. 2004;11:231-237.

5. de la Cabada Bauche J, DuPont HL. New developments in traveler’s diarrhea. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:88-95.

6. Cabada MM, White AC. Travelers’ diarrhea: an update on susceptibility, prevention, and treatment. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:473-479.

7. Ericsson CD. Travellers with pre-existing medical conditions. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:181-188.

8. Cabada MM, Maldonado F, Quispe W, et al. Risk factors associated with diarrhea among international visitors to Cuzco, Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:968-972.

9. Mackell S. Traveler’s diarrhea in the pediatric population: etiology and impact. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(suppl 8):S547-S552.

10. Hill DR, Ericsson CD, Pearson RD, et al. The practice of travel medicine: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1499-1539.

11. Connor BA. Travelers’ diarrhea. wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/ 2012/chapter-2-the-pre-travel-consultation/travelers-diarrhea.htm. Accessed April 22, 2014.

12. Advice for travelers. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2012;10:45-56.

13. Shlim DR. Looking for evidence that personal hygiene precautions prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(suppl 8):S531-S535.

14. Laverone E, Boccalini S, Bechini A, et al. Travelers’ compliance to prophylactic measures and behavior during stay abroad: results of a retrospective study of subjects returning to a travel medicine center in Italy. J Travel Med. 2006;13:338-344.

15. Ashley DV, Walters C, Dockery-Brown C, et al. Interventions to prevent and control food-borne diseases associated with a reduction in traveler’s diarrhea in tourists to Jamaica. J Travel Med. 2004;11:364-367.

16. Shah N, DuPont HL, Ramsey DJ. Global etiology of travelers’ diarrhea: systematic review from 1973 to the present. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:609-614.

17. Riddle MS, Sanders JW, Putnam SD, et al. Incidence, etiology, and impact of diarrhea among long-term travelers (US military and similar populations): a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:891-900.

18. Koo HL, Ajami NJ, Jiang ZD, et al. Noroviruses as a cause of diarrhea in travelers to Guatemala, India, and Mexico. J Clin Microbiol. 2010; 48:1673-1676.

19. Hill DR, Ryan ET. Management of travellers’ diarrhoea. BMJ. 2008; 337:863-867.

20. Rendi-Wagner P, Kollaritsch H. Drug prophylaxis for travelers’ diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:628-633.

21. Pimentel M, Riddle MS. Prevention of traveler’s diarrhea: a call to reconvene. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:151-152.

22. DuPont HL. Systematic review: prevention of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:741-751.

23. Wang M, Szucs TD, Steffen R. Economic aspects of travelers’ diarrhea.

J Travel Med. 2008;15:110-118.

24. Neal KR, Barker L, Spiller RC. Prognosis in post-infective irritable bowel syndrome: a six year follow up study. Gut. 2002;51:410-413.

25. Tornblom H, Holmvall P, Svenungsson B, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms after infectious diarrhea: a five-year follow-up in a Swedish cohort of adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:461-464.

26. DuPont HL, Jiang ZD, Okhuysen PC, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin to prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:805-812.

27. Taylor DN, McKenzie R, Durbin A, et al. Rifaximin, a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic, prevents shigellosis after experimental challenge. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1283-1288.

28. Sazawal S, Hiremath G, Dhingra U, et al. Efficacy of probiotics in prevention of acute diarrhoea: a meta-analysis of masked, randomised, placebo-controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:374-382.

29. Bri V, Buffet P, Genty S, et al. Absence of efficacy of nonviable Lactobacillus acidophilus for the prevention of traveler’s diarrhea: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1170-1175.

30. Hill DR, Ford L, Lalloo DG. Oral cholera vaccines—use in clinical practice. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:361-373.

31. Taylor DN, Bourgeois AL, Ericsson CD, et al. A randomized double-blind, multicenter study of rifaximin compared with placebo and with ciprofloxacin in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:1060-1066.

32. DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Farthing MJG, et al. Expert review of the evidence base for self-therapy of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2009; 16:161-171.

33. Tribble DR, Sanders JW, Pang LW, et al. Traveler’s diarrhea in Thailand: randomized, double-blind trial comparing single-dose and 3-day azithromycin-based regimens with a 3-day levofloxacin regimen. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:338-346.

34. Riddle MS, Arnold S, Tribble DR. Effect of adjunctive loperamide in combination with antibiotics on treatment outcomes in travelers’ diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 47:1007-1014.

35. Steffen R. Worldwide efficacy of bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(suppl 1):S80-S86.

36. Connor BA. Persistent travelers’ diarrhea. wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/

yellowbook/2012/chapter-5-post-travel-evaluation/persistent-travelers-diarrhea.htm. Accessed April 22 2014.

37. Landzberg BR, Connor BA. Persistent diarrhea in the returning traveler: think beyond persistent infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:

112-114.