User login

› Recommend cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, or problem-solving therapy for the treatment of depression in patients of all ages. A

› Consider prescribing exercise as a stand-alone or adjunctive treatment for patients with depression. B

› Advise patients who ask about omega-3 fatty acid supplements that formulations with a high eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) ratio (2:1) may be a useful “add-on” to their current regimen. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Steve J, age 43, comes to your clinic looking uncharacteristically glum. He was recently downsized from his job and misses his former colleagues. His job loss has caused a financial strain for his family, and he admits to crying in the shower when he thinks about how his life has turned out. Mr. J tells you that he’s gotten a part-time job, but he’s already called in sick several times. On those sick days he “stayed in bed all day and slept.” He says that when he does go to work, he rarely interacts with his coworkers and his concentration is poor. He tells you he wakes up early in the morning on most days and cannot return to sleep, despite being “tired all the time.” He denies suicidal ideation. Mr. J has never felt this way before, which is what prompted his visit today, but he thinks it is “weak to take a pill to feel better.”

What nonpharmacologic options can you offer him?

CASE 2 › Kerri S is a 27-year-old mother of 2 who comes to your clinic to establish care. She tells you about a recent recurrence of depressed mood, which she feels is due to the stress of moving to the area. She is experiencing sleep-onset insomnia and concentration lapses. Her appetite is poor (self-reported 8-lb weight loss in 2 months) and she lacks the motivation to engage in her daily activities, saying, “I wouldn’t even get out of bed if my kids didn’t need me.” She notes that she is constantly irritable and has completely lost her sex drive. Unlike her prior depressive episode, she has not had any suicidal thoughts. Mrs. S was previously successfully treated with paroxetine, 20 mg/d, but she is not interested in restarting her medication because she is still breastfeeding her toddler.

Are there evidence-based options for her care that do not include medication?

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is widespread and often disabling, affecting nearly 8% of people ages 12 and older at any given time.1 Thus, it’s crucial to be familiar with the diverse array of evidence-based treatment options from which patients can choose. Although medications are an essential treatment option for patients with severe depression, their value for patients with mild to moderate depression is often limited.2 In addition, when antidepressants aren’t combined with psychosocial interventions, discontinuing them is associated with relapse.3

Fortunately, research has found that certain nonpharmacologic interventions—including psychotherapies, somatic therapies, and dietary supplements—can have either therapeutic or adjunctive benefits for treating depression, and can be provided in ways that are time- and cost-effective. This article reviews the evidence supporting several options in each of these treatment categories.

Evidence backs several types of psychotherapy

Several recent meta-analyses suggest that a variety of psychotherapeutic treatments may hold promise for your patients with depression.4,5 When analyses were limited to larger studies in order to decrease the risk of bias, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and problem-solving therapy (PST) all resulted in moderate to large improvement in depressive symptoms when compared to wait-list controls.4 These findings were echoed in a recent systematic review/meta-analysis that focused on depressed primary care patients. Linde et al5 found that the number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve one response (≥50% reduction in score on a depression scale) using any type of psychotherapy was 10, and the NNT to achieve one remission (scoring below a predefined score on a depression scale) was 15.

Psychotherapy can be effective when provided in individual and group settings,6 as well as via telephone, the Internet, or software programs.7 (For a list of self-help, computerized, and Internet-based resources, see TABLE W1 below.)

CBT has been studied for several decades and there’s strong evidence for its efficacy.6 Recent investigations have suggested that CBT delivered in less resource-intensive modes (such as via computer program, Internet, telephone, or videoconferencing) can be as effective as face-to-face CBT.6,8 CBT has been shown to be helpful for a wide range of patients,6 improves outcomes over standard primary care treatment,9 and provides a useful adjunct to medication in treatment-resistant severe depression.10

Behavioral activation (BA), which generally is included as a component of CBT, has received support as an independent treatment, and may produce therapeutic results similar to CBT11 and PST (which we’ll discuss in a bit).12 The core components of BA are scheduling pleasant activities and increasing the patient’s positive interactions with his or her environment by decreasing avoidance, withdrawal, and inactivity.11 Compared to CBT, BA is easier for clinicians to learn and incorporate into primary care visits, and it may be especially useful as an adjunctive or first-step intervention in outpatient clinics.11 Like CBT, BA can be effective in diverse patient groups13,14 and can be provided using novel delivery modes, such as via the Internet.15

IPT is a supportive, structured, brief therapy (12-16 visits) that focuses on helping patients identify and solve current situation- and relationship-based problems that stem from or contribute to their depression.16 Enhancing the patient’s interpersonal communication—including improving social skills, assertiveness, and appropriate expression of anger—is typically a component of IPT. Like CBT, IPT has been found to be effective for treating depression when administered in person, in group therapy, or via the phone or Internet, and across a broad age range.17-19

PST involves teaching patients a structured problem-solving process to decrease interpersonal strain and improve positive life experiences.20 Patients are taught to define their problem, generate and evaluate multiple solutions for it, implement a plan for the solution, and evaluate the results. In addition to being used to successfully treat adults,4,5 PST has been adapted effectively to treat adolescents16 and older adults.18

Somatic therapies are also an option

Exercise has long been considered a possible depression treatment due to its activity on endorphin, monoamine, and cortisol levels and via increased social and general activity. A 2013 Cochrane review of 39 randomized control trials (RCTs; N=2326) assessed whether exercise was effective for treating depression in adults.21 Thirty-five trials found a moderate effect size when specifically comparing exercise to no treatment or control interventions. The effect size was reduced, however, when analyses were restricted to trials with the highest methodological quality. There was no statistically significant difference when exercise was compared to pharmacologic treatment or psychotherapy.

Although the amount of research is meager, small but statistically significant improvements have also been found for older adults22 and children/adolescents.23 There is no consensus on the type, frequency, or intensity of exercise needed to achieve benefit. However, because nearly all studies for all age groups have found that exercise has no adverse psychological effects and substantial positive physical effects, exercise should be recommended to all patients with depression unless contraindicated.

Yoga (both exercise-based and meditation-based) has been evaluated both as a sole treatment and as an adjunctive treatment for depression. Several studies have supported the impact of yoga, particularly in pregnant women,24 although the evidence for its efficacy is inconsistent, with yoga frequently failing to improve upon the outcome of waitlist control.25 The evidence for meditation and mindfulness is more consistently positive, with these interventions equaling or exceeding “treatment as usual,” other psychotherapies, and antidepressants in numerous RCTs.25

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has a substantial evidence base supporting its efficacy.26 ECT has been used for decades, although stigma, cardiac and memory risks, and risks of anesthesia often limit its use. Benefits of ECT include a rapid response relative to pharmacotherapy (>50% of patients respond by the end of the first week of ECT)27 and a strong response in older patients.28

In repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), electromagnetic coils are placed on a patient’s head to deliver electromagnetic pulses that stimulate areas of the brain that regulate mood. Although rTMS is not widely available, a growing body of evidence supports its use for treating depression, including a meta-analysis of 34 RCTs that included 1383 patients.29 A multisite RCT (N=190) that was not industry-funded reported a 15% response rate and 60% maintenance of remission at 3 months (NNT=12).30 Although ECT is more effective than rTMS, rTMS appears useful for treatment-resistant depression, and can be used as an adjunctive treatment.29,31

Dietary supplements may be best used as adjuncts

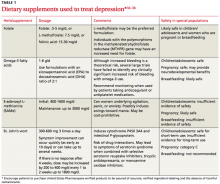

St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), which contains 2 bioactive ingredients (hyperforin and hypericin), has been effectively used to treat depression.32 A 2008 Cochrane review that was limited to high-quality trials involving patients meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition criteria for depression identified 29 trials (N=5489), of which 18 involved comparisons with placebo and 17 with standard antidepressants.33 Patients’ depression was rated mild to moderate in 19 studies and moderate to severe in 9 studies. Trials examined 4 to 12 weeks of treatment with Hypericum extracts. This study (and several published since) provides strong clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of St. John’s wort for mild to moderate depression. There is insufficient evidence for its use for severe major depression.33TABLE 1 contains dosing information for St. John’s wort and other supplements used to treat depression.34-36

S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe). In a 2003 systematic review,37 1600 mg/d of oral SAMe was found to significantly benefit patients with depression in 4 of 5 studies, as did parenteral SAMe (7 of 7 trials). Another review of 48 studies found SAMe was safe and effective for depression.38 SAMe has been proposed for use alone or in combination with an antidepressant.

Folate and folic acid. Low folate levels have been associated with a less robust response to antidepressants in patients with MDD,39 and higher folate levels appear to be associated with better antidepressant response.40 A 2003 Cochrane review suggested folate might have a role in treating depression.39 A 2009 study found folate supplementation could reduce depressive symptoms for patients with normal baseline folate levels as well as those with low levels.41 Although the evidence is equivocal, folate augmentation may enhance antidepressant efficacy or improve response/remission rates.41,42

It seems reasonable to check folate levels in depressed patients, and address deficiencies by instructing patients to increase their dietary intake of folate or to take supplements. Augmenting antidepressants with folate appears to be low-risk and possibly helpful in maintaining remission.

Omega-3 fatty acids. There is substantial evidence that omega-3 fatty acids can prevent and treat depression.43,44 Recent meta-analyses support the use of omega-3 fatty acids as monotherapy and augmentation, but only formulations that contain a high eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) ratio (EPA/DHA 2:1).45,46 Omega-3 supplementation has been used with positive results in older adults, children,47 pregnant women,48 and women with postpartum depression.49 Although initial research into omega-3 treatment of depression appears promising, augmentation of standard antidepressant therapy may be a good conservative option.

Use a validated tool to monitor response to treatment

You can enhance outcomes for your patients with depression if you schedule routine follow-up visits with them to gauge adherence to recommendations, monitor response to treatment, and increase the intensity of care when response is inadequate.50 The most important aspect of monitoring response is to use a standardized instrument that quantifies symptoms at every visit.

The Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item depression assessment (PHQ-9)—which is free—has been validated for depression screening and monitoring of treatment response in primary care patients.51 A decrease of 5 points on the PHQ-9 is the minimum considered to be clinically significant.52 Other well-validated, although lengthier, self-report depression assessment and monitoring instruments include the Beck Depression Inventory-revised and the Zung Depression Scale.

CASE 1 › Mr. J is not enjoying his new job or engaging with new coworkers to replace the positive social experiences he had at his previous job. Together, you set a goal of increasing social involvement by having him make plans to see at least one friend per weekend. Because he indicates that he is unlikely to follow through with a therapy referral, you encourage him to try an online CBT program, start an exercise regimen, or take a SAMe supplement. Mr. Jackson agrees to try the CBT and exercise (moderate intensity, 30 minutes 3-4 times per week), but does not want to take SAMe. He agrees to an assessment of his folate levels, which are normal.

Mr. J starts the online CBT program, which reinforces the exercise and social activity prescription you provided. He establishes a regular exercise routine with a good friend. After one month, his mood has started to improve and he has added regular participation in a hobby (woodworking), as well as volunteer work, which he finds fulfilling. You plan to continue monitoring his depression and his adherence to the treatment plan.

CASE 2 › The recent move has decreased Mrs. S’s interactions with family and long-time friends. Because she had previously expressed interest in exercise, you encourage her to join a local “Mommy and Me” exercise and support group for mothers of toddlers. She is willing to participate in psychotherapy, so you provide a referral to a local therapist with expertise in IPT. You also discuss with Mrs. S the possible benefits of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, which appears to be safe during breastfeeding.34

Mrs. S begins therapy and exercise classes, but can’t motivate herself to continue either of these activities. She becomes discouraged because she’s unable to easily find an omega-3 fatty acid supplement with the ratio you specified (EPA/DHA 2:1). When you see her 2 weeks later, her depression has worsened.

Because you are concerned her suicidality will return, you revisit the pros and cons of taking an antidepressant. Although small amounts of antidepressants can be passed from mother to infant via breastmilk, the amount varies by specific medication, as do the potential risks. Mrs. S decides to resume taking paroxetine 20 mg/d and eventually, once her motivation improves, she’s able to add psychotherapy and exercise to her maintenance/relapse prevention regimen. After you discuss with her the possibility that B vitamin supplementation may assist in maintenance of remission, she adds L-methylfolate 7.5 mg/day to her regimen.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michele M. Larzelere, PhD; LSUHSC Department of Family Medicine; 200 W. Esplanade Avenue, Suite 409; Kenner, LA 70065; mlarze@lsuhsc.edu

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). QuickStats: Prevalence of Current Depression Among Persons Aged ≥12 Years, by Age Group and Sex — United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2010. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6051a7.htm. Accessed June 11, 2015.

2. Fournier J, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:47-53.

3. Dobson KS, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the prevention of relapse and recurrence in major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:468-477.

4. Barth J, Munder T, Gerger H, et al. Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: A network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001454.

5. Linde K, Sigterman K, Kriston L, et al. Effectiveness of psychological treatments for depressive disorders in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:56-68.

6. DeRubeis RJ, Webb CA, Tang TZ, et al. Cognitive therapy. In: Dobson KS, ed. Handbook of Cognitive Behavioral Therapies, 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2009:277-316.

7. Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2008;38:196-205.

8. Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, et al. Guided internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:288-295.

9. Twomey C, O’Reilly G, Byrne M. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 2015;32:3-15.

10. Zhou X, Michael K, Liu Y, et al. Systematic review of management for treatment-resistant depression in adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:340.

11. Ekers D, Webster L, Van Straten A, et al. Behavioural activation for depression: An update of meta-analysis of effectiveness and sub group analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100100.

12. Alexopoulos GS, Raue PJ, Kiosses DN, et al. Comparing engage with PST in late-life major depression: A preliminary report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:506-513.

13. Soucy Chartier I, Provencher MD. Behavioral activation for depression: Efficacy, effectiveness, and dissemination. J Affect Disord. 2013;145:292-299.

14. McCauley E, Gudmundson G, Schloredt K, et al. The Adolescent Behavior Activation Program: Adapting behavioral activation as a treatment for depression in adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;1-14. [Epub ahead of print].

15. Carlbring P, Hägglund M, Luthström A, et al. Internet-based behavioral activation and acceptance-based treatment for depression: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:331-337.

16. Markowitz JC, Weissman MM. Interpersonal psychotherapy: principles and applications. World Psychiatry. 2004; 3:136-139.

17. Kersting A, Kroker K, Schlicht S, et al. Efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral internet-based therapy in parents after the loss of a child during pregnancy: pilot data from a randomized controlled trial. Arch Womens Mental Health. 2011;14:465-477.

18. Francis J, Kumar A. Psychological treatment of late-life depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36:561-575.

19. Picardi A, Gaetano P. Psychotherapy of mood disorders. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2014;10:140-158.

20. Bell AC, D’Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Review. 2009;29:348-353.

21. Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD004366

22. Brindle C, Spanjers K, Patel S, et al. Effect of exercise on depression severity in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. B J Psychiatry. 2012;201:180-185.

23. Brown HE, Pearson N, Braithwaite RE, et al. Physical activity interventions and depression in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2013;43:195-206.

24. Gong H, Ni C, Shen X, et al. Yoga for prenatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:14.

25. D’Silva S, Poscablo C, Habousha R, et al. Mind-body medicine therapies for a range of depression severity: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:407-423.

26. Lisanby SH. Electroconvulsive therapy for depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1939-1945.

27. Husain MM, Rush AJ, Fink M, et al. Speed of response and remission in major depressive disorder with acute electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a Consortium for Research in ECT (CORE) report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:485-491.

28. Rhebergen D, Huisman A, Bouckaert F, et al. Older age is associated with rapid remission of depression after electroconvulsive therapy: a latent class growth analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:274-282.

29. Slotema CW, Blom JD, Hoek HW, et al. Should we expand the toolbox of psychiatric treatment methods to include Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)? A metaanalysis of the efficacy of rTMS in psychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:873-884.

30. George MS, Lisanby SH, Avery D, et al. Daily left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy for major depressive disorder: a sham-controlled randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:507-516

31. Liu B, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as an augmentative strategy for treatment-resistant depression, a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind and sham controlled studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:342.

32. Brown RP, Gerberg PL, Muskin PR. Mood disorders. In: Brown RP, Gerbarg PL, Muskin P. How to Use Herbs, Nutrients and Yoga in Mental Health. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company; 2009.

33. Linde K, Berner MM, Kriston L. St John’s wort for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD000448.

34. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database Web site. Available at: http://naturaldatabase.therapeuticresearch.com/home.aspx. Accessed March 1, 2015.

35. Harris WS. Expert opinion: omega-3 fatty acids and bleeding-cause for concern? Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:44C-6C.

36. Freeman MP, Fava M, Lake J, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in major depressive disorder: the American Psychiatric Association Task Force Report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:669-681.

37. Papakostas GI, Alpert JE, Fava M. S-adenosyl-methionine in depression: a comprehensive review of the literature. Curr Psychiatry Reports. 2003;5:460-466.

38. Brown RP, Gerbarg PL, Bottiglieri T. S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe) for depression: biochemical and clinical evidence. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:29-44.

39. Taylor MJ, Carney S, Geddes J, et al. Folate for depressive disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003390.

40. Alpert M, Silva RR, Pouget ER. Prediction of treatment response in geriatric depression from baseline folate level: interaction with an SSRI or a tricyclic antidepressant. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:309-313.

41. Fava M, Mischoulon D. Folate in depression: efficacy, safety, differences in formulations, and clinical issues. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 5):12-17.

42. Almeida OP, Ford AH, Hirani V, et al. B vitamins to enhance treatment response to antidepressants in middle-aged and older adults: results from the B-VITAGE randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:450-457.

43. Grosso G, Galvano F, Marventano S, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: scientific evidence and biological mechanisms. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:313570.

44. Appleton KM, Rogers PJ, Ness AR. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on depressed mood. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:757-770.

45. Grosso G, Pajak A, Marventano S, et al. Role of omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of depressive disorders: a comprehensive metaanalysis of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96905.

46. Martins JG, Bentsen H, Puri BK. Eicosapentaenoic acid appears to be the key omega-3 fatty acid component associated with efficacy in major depressive disorder: a critique of Bloch and Hannestad and updated meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:1144-1149.

47. Nemets H, Nemets B, Apter A, et al. Omega-3 treatment of childhood depression: a controlled, double-blind pilot study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1098-1100.

48. Su KP, Huang SY, Chiu TH. Omega-3 fatty acids for major depressive disorder during pregnancy: Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:644-651.

49. Freeman MP, Davis M, Sinha P, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and supportive psychotherapy for perinatal depression: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2008;110:142-148.

50. Mitchell J, Trangle M, Degnan B, et al. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Health Care Guideline: Adult depression in primary care. 16th ed. September 2013. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/fnhdm3/Depr-Interactive0512b.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2015.

51. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345-359.

52. Trivedi MH. Tools and strategies for ongoing assessment of depression:

a measurement-based approach to remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:26-31.

› Recommend cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, or problem-solving therapy for the treatment of depression in patients of all ages. A

› Consider prescribing exercise as a stand-alone or adjunctive treatment for patients with depression. B

› Advise patients who ask about omega-3 fatty acid supplements that formulations with a high eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) ratio (2:1) may be a useful “add-on” to their current regimen. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Steve J, age 43, comes to your clinic looking uncharacteristically glum. He was recently downsized from his job and misses his former colleagues. His job loss has caused a financial strain for his family, and he admits to crying in the shower when he thinks about how his life has turned out. Mr. J tells you that he’s gotten a part-time job, but he’s already called in sick several times. On those sick days he “stayed in bed all day and slept.” He says that when he does go to work, he rarely interacts with his coworkers and his concentration is poor. He tells you he wakes up early in the morning on most days and cannot return to sleep, despite being “tired all the time.” He denies suicidal ideation. Mr. J has never felt this way before, which is what prompted his visit today, but he thinks it is “weak to take a pill to feel better.”

What nonpharmacologic options can you offer him?

CASE 2 › Kerri S is a 27-year-old mother of 2 who comes to your clinic to establish care. She tells you about a recent recurrence of depressed mood, which she feels is due to the stress of moving to the area. She is experiencing sleep-onset insomnia and concentration lapses. Her appetite is poor (self-reported 8-lb weight loss in 2 months) and she lacks the motivation to engage in her daily activities, saying, “I wouldn’t even get out of bed if my kids didn’t need me.” She notes that she is constantly irritable and has completely lost her sex drive. Unlike her prior depressive episode, she has not had any suicidal thoughts. Mrs. S was previously successfully treated with paroxetine, 20 mg/d, but she is not interested in restarting her medication because she is still breastfeeding her toddler.

Are there evidence-based options for her care that do not include medication?

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is widespread and often disabling, affecting nearly 8% of people ages 12 and older at any given time.1 Thus, it’s crucial to be familiar with the diverse array of evidence-based treatment options from which patients can choose. Although medications are an essential treatment option for patients with severe depression, their value for patients with mild to moderate depression is often limited.2 In addition, when antidepressants aren’t combined with psychosocial interventions, discontinuing them is associated with relapse.3

Fortunately, research has found that certain nonpharmacologic interventions—including psychotherapies, somatic therapies, and dietary supplements—can have either therapeutic or adjunctive benefits for treating depression, and can be provided in ways that are time- and cost-effective. This article reviews the evidence supporting several options in each of these treatment categories.

Evidence backs several types of psychotherapy

Several recent meta-analyses suggest that a variety of psychotherapeutic treatments may hold promise for your patients with depression.4,5 When analyses were limited to larger studies in order to decrease the risk of bias, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and problem-solving therapy (PST) all resulted in moderate to large improvement in depressive symptoms when compared to wait-list controls.4 These findings were echoed in a recent systematic review/meta-analysis that focused on depressed primary care patients. Linde et al5 found that the number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve one response (≥50% reduction in score on a depression scale) using any type of psychotherapy was 10, and the NNT to achieve one remission (scoring below a predefined score on a depression scale) was 15.

Psychotherapy can be effective when provided in individual and group settings,6 as well as via telephone, the Internet, or software programs.7 (For a list of self-help, computerized, and Internet-based resources, see TABLE W1 below.)

CBT has been studied for several decades and there’s strong evidence for its efficacy.6 Recent investigations have suggested that CBT delivered in less resource-intensive modes (such as via computer program, Internet, telephone, or videoconferencing) can be as effective as face-to-face CBT.6,8 CBT has been shown to be helpful for a wide range of patients,6 improves outcomes over standard primary care treatment,9 and provides a useful adjunct to medication in treatment-resistant severe depression.10

Behavioral activation (BA), which generally is included as a component of CBT, has received support as an independent treatment, and may produce therapeutic results similar to CBT11 and PST (which we’ll discuss in a bit).12 The core components of BA are scheduling pleasant activities and increasing the patient’s positive interactions with his or her environment by decreasing avoidance, withdrawal, and inactivity.11 Compared to CBT, BA is easier for clinicians to learn and incorporate into primary care visits, and it may be especially useful as an adjunctive or first-step intervention in outpatient clinics.11 Like CBT, BA can be effective in diverse patient groups13,14 and can be provided using novel delivery modes, such as via the Internet.15

IPT is a supportive, structured, brief therapy (12-16 visits) that focuses on helping patients identify and solve current situation- and relationship-based problems that stem from or contribute to their depression.16 Enhancing the patient’s interpersonal communication—including improving social skills, assertiveness, and appropriate expression of anger—is typically a component of IPT. Like CBT, IPT has been found to be effective for treating depression when administered in person, in group therapy, or via the phone or Internet, and across a broad age range.17-19

PST involves teaching patients a structured problem-solving process to decrease interpersonal strain and improve positive life experiences.20 Patients are taught to define their problem, generate and evaluate multiple solutions for it, implement a plan for the solution, and evaluate the results. In addition to being used to successfully treat adults,4,5 PST has been adapted effectively to treat adolescents16 and older adults.18

Somatic therapies are also an option

Exercise has long been considered a possible depression treatment due to its activity on endorphin, monoamine, and cortisol levels and via increased social and general activity. A 2013 Cochrane review of 39 randomized control trials (RCTs; N=2326) assessed whether exercise was effective for treating depression in adults.21 Thirty-five trials found a moderate effect size when specifically comparing exercise to no treatment or control interventions. The effect size was reduced, however, when analyses were restricted to trials with the highest methodological quality. There was no statistically significant difference when exercise was compared to pharmacologic treatment or psychotherapy.

Although the amount of research is meager, small but statistically significant improvements have also been found for older adults22 and children/adolescents.23 There is no consensus on the type, frequency, or intensity of exercise needed to achieve benefit. However, because nearly all studies for all age groups have found that exercise has no adverse psychological effects and substantial positive physical effects, exercise should be recommended to all patients with depression unless contraindicated.

Yoga (both exercise-based and meditation-based) has been evaluated both as a sole treatment and as an adjunctive treatment for depression. Several studies have supported the impact of yoga, particularly in pregnant women,24 although the evidence for its efficacy is inconsistent, with yoga frequently failing to improve upon the outcome of waitlist control.25 The evidence for meditation and mindfulness is more consistently positive, with these interventions equaling or exceeding “treatment as usual,” other psychotherapies, and antidepressants in numerous RCTs.25

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has a substantial evidence base supporting its efficacy.26 ECT has been used for decades, although stigma, cardiac and memory risks, and risks of anesthesia often limit its use. Benefits of ECT include a rapid response relative to pharmacotherapy (>50% of patients respond by the end of the first week of ECT)27 and a strong response in older patients.28

In repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), electromagnetic coils are placed on a patient’s head to deliver electromagnetic pulses that stimulate areas of the brain that regulate mood. Although rTMS is not widely available, a growing body of evidence supports its use for treating depression, including a meta-analysis of 34 RCTs that included 1383 patients.29 A multisite RCT (N=190) that was not industry-funded reported a 15% response rate and 60% maintenance of remission at 3 months (NNT=12).30 Although ECT is more effective than rTMS, rTMS appears useful for treatment-resistant depression, and can be used as an adjunctive treatment.29,31

Dietary supplements may be best used as adjuncts

St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), which contains 2 bioactive ingredients (hyperforin and hypericin), has been effectively used to treat depression.32 A 2008 Cochrane review that was limited to high-quality trials involving patients meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition criteria for depression identified 29 trials (N=5489), of which 18 involved comparisons with placebo and 17 with standard antidepressants.33 Patients’ depression was rated mild to moderate in 19 studies and moderate to severe in 9 studies. Trials examined 4 to 12 weeks of treatment with Hypericum extracts. This study (and several published since) provides strong clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of St. John’s wort for mild to moderate depression. There is insufficient evidence for its use for severe major depression.33TABLE 1 contains dosing information for St. John’s wort and other supplements used to treat depression.34-36

S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe). In a 2003 systematic review,37 1600 mg/d of oral SAMe was found to significantly benefit patients with depression in 4 of 5 studies, as did parenteral SAMe (7 of 7 trials). Another review of 48 studies found SAMe was safe and effective for depression.38 SAMe has been proposed for use alone or in combination with an antidepressant.

Folate and folic acid. Low folate levels have been associated with a less robust response to antidepressants in patients with MDD,39 and higher folate levels appear to be associated with better antidepressant response.40 A 2003 Cochrane review suggested folate might have a role in treating depression.39 A 2009 study found folate supplementation could reduce depressive symptoms for patients with normal baseline folate levels as well as those with low levels.41 Although the evidence is equivocal, folate augmentation may enhance antidepressant efficacy or improve response/remission rates.41,42

It seems reasonable to check folate levels in depressed patients, and address deficiencies by instructing patients to increase their dietary intake of folate or to take supplements. Augmenting antidepressants with folate appears to be low-risk and possibly helpful in maintaining remission.

Omega-3 fatty acids. There is substantial evidence that omega-3 fatty acids can prevent and treat depression.43,44 Recent meta-analyses support the use of omega-3 fatty acids as monotherapy and augmentation, but only formulations that contain a high eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) ratio (EPA/DHA 2:1).45,46 Omega-3 supplementation has been used with positive results in older adults, children,47 pregnant women,48 and women with postpartum depression.49 Although initial research into omega-3 treatment of depression appears promising, augmentation of standard antidepressant therapy may be a good conservative option.

Use a validated tool to monitor response to treatment

You can enhance outcomes for your patients with depression if you schedule routine follow-up visits with them to gauge adherence to recommendations, monitor response to treatment, and increase the intensity of care when response is inadequate.50 The most important aspect of monitoring response is to use a standardized instrument that quantifies symptoms at every visit.

The Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item depression assessment (PHQ-9)—which is free—has been validated for depression screening and monitoring of treatment response in primary care patients.51 A decrease of 5 points on the PHQ-9 is the minimum considered to be clinically significant.52 Other well-validated, although lengthier, self-report depression assessment and monitoring instruments include the Beck Depression Inventory-revised and the Zung Depression Scale.

CASE 1 › Mr. J is not enjoying his new job or engaging with new coworkers to replace the positive social experiences he had at his previous job. Together, you set a goal of increasing social involvement by having him make plans to see at least one friend per weekend. Because he indicates that he is unlikely to follow through with a therapy referral, you encourage him to try an online CBT program, start an exercise regimen, or take a SAMe supplement. Mr. Jackson agrees to try the CBT and exercise (moderate intensity, 30 minutes 3-4 times per week), but does not want to take SAMe. He agrees to an assessment of his folate levels, which are normal.

Mr. J starts the online CBT program, which reinforces the exercise and social activity prescription you provided. He establishes a regular exercise routine with a good friend. After one month, his mood has started to improve and he has added regular participation in a hobby (woodworking), as well as volunteer work, which he finds fulfilling. You plan to continue monitoring his depression and his adherence to the treatment plan.

CASE 2 › The recent move has decreased Mrs. S’s interactions with family and long-time friends. Because she had previously expressed interest in exercise, you encourage her to join a local “Mommy and Me” exercise and support group for mothers of toddlers. She is willing to participate in psychotherapy, so you provide a referral to a local therapist with expertise in IPT. You also discuss with Mrs. S the possible benefits of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, which appears to be safe during breastfeeding.34

Mrs. S begins therapy and exercise classes, but can’t motivate herself to continue either of these activities. She becomes discouraged because she’s unable to easily find an omega-3 fatty acid supplement with the ratio you specified (EPA/DHA 2:1). When you see her 2 weeks later, her depression has worsened.

Because you are concerned her suicidality will return, you revisit the pros and cons of taking an antidepressant. Although small amounts of antidepressants can be passed from mother to infant via breastmilk, the amount varies by specific medication, as do the potential risks. Mrs. S decides to resume taking paroxetine 20 mg/d and eventually, once her motivation improves, she’s able to add psychotherapy and exercise to her maintenance/relapse prevention regimen. After you discuss with her the possibility that B vitamin supplementation may assist in maintenance of remission, she adds L-methylfolate 7.5 mg/day to her regimen.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michele M. Larzelere, PhD; LSUHSC Department of Family Medicine; 200 W. Esplanade Avenue, Suite 409; Kenner, LA 70065; mlarze@lsuhsc.edu

› Recommend cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, or problem-solving therapy for the treatment of depression in patients of all ages. A

› Consider prescribing exercise as a stand-alone or adjunctive treatment for patients with depression. B

› Advise patients who ask about omega-3 fatty acid supplements that formulations with a high eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) ratio (2:1) may be a useful “add-on” to their current regimen. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Steve J, age 43, comes to your clinic looking uncharacteristically glum. He was recently downsized from his job and misses his former colleagues. His job loss has caused a financial strain for his family, and he admits to crying in the shower when he thinks about how his life has turned out. Mr. J tells you that he’s gotten a part-time job, but he’s already called in sick several times. On those sick days he “stayed in bed all day and slept.” He says that when he does go to work, he rarely interacts with his coworkers and his concentration is poor. He tells you he wakes up early in the morning on most days and cannot return to sleep, despite being “tired all the time.” He denies suicidal ideation. Mr. J has never felt this way before, which is what prompted his visit today, but he thinks it is “weak to take a pill to feel better.”

What nonpharmacologic options can you offer him?

CASE 2 › Kerri S is a 27-year-old mother of 2 who comes to your clinic to establish care. She tells you about a recent recurrence of depressed mood, which she feels is due to the stress of moving to the area. She is experiencing sleep-onset insomnia and concentration lapses. Her appetite is poor (self-reported 8-lb weight loss in 2 months) and she lacks the motivation to engage in her daily activities, saying, “I wouldn’t even get out of bed if my kids didn’t need me.” She notes that she is constantly irritable and has completely lost her sex drive. Unlike her prior depressive episode, she has not had any suicidal thoughts. Mrs. S was previously successfully treated with paroxetine, 20 mg/d, but she is not interested in restarting her medication because she is still breastfeeding her toddler.

Are there evidence-based options for her care that do not include medication?

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is widespread and often disabling, affecting nearly 8% of people ages 12 and older at any given time.1 Thus, it’s crucial to be familiar with the diverse array of evidence-based treatment options from which patients can choose. Although medications are an essential treatment option for patients with severe depression, their value for patients with mild to moderate depression is often limited.2 In addition, when antidepressants aren’t combined with psychosocial interventions, discontinuing them is associated with relapse.3

Fortunately, research has found that certain nonpharmacologic interventions—including psychotherapies, somatic therapies, and dietary supplements—can have either therapeutic or adjunctive benefits for treating depression, and can be provided in ways that are time- and cost-effective. This article reviews the evidence supporting several options in each of these treatment categories.

Evidence backs several types of psychotherapy

Several recent meta-analyses suggest that a variety of psychotherapeutic treatments may hold promise for your patients with depression.4,5 When analyses were limited to larger studies in order to decrease the risk of bias, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and problem-solving therapy (PST) all resulted in moderate to large improvement in depressive symptoms when compared to wait-list controls.4 These findings were echoed in a recent systematic review/meta-analysis that focused on depressed primary care patients. Linde et al5 found that the number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve one response (≥50% reduction in score on a depression scale) using any type of psychotherapy was 10, and the NNT to achieve one remission (scoring below a predefined score on a depression scale) was 15.

Psychotherapy can be effective when provided in individual and group settings,6 as well as via telephone, the Internet, or software programs.7 (For a list of self-help, computerized, and Internet-based resources, see TABLE W1 below.)

CBT has been studied for several decades and there’s strong evidence for its efficacy.6 Recent investigations have suggested that CBT delivered in less resource-intensive modes (such as via computer program, Internet, telephone, or videoconferencing) can be as effective as face-to-face CBT.6,8 CBT has been shown to be helpful for a wide range of patients,6 improves outcomes over standard primary care treatment,9 and provides a useful adjunct to medication in treatment-resistant severe depression.10

Behavioral activation (BA), which generally is included as a component of CBT, has received support as an independent treatment, and may produce therapeutic results similar to CBT11 and PST (which we’ll discuss in a bit).12 The core components of BA are scheduling pleasant activities and increasing the patient’s positive interactions with his or her environment by decreasing avoidance, withdrawal, and inactivity.11 Compared to CBT, BA is easier for clinicians to learn and incorporate into primary care visits, and it may be especially useful as an adjunctive or first-step intervention in outpatient clinics.11 Like CBT, BA can be effective in diverse patient groups13,14 and can be provided using novel delivery modes, such as via the Internet.15

IPT is a supportive, structured, brief therapy (12-16 visits) that focuses on helping patients identify and solve current situation- and relationship-based problems that stem from or contribute to their depression.16 Enhancing the patient’s interpersonal communication—including improving social skills, assertiveness, and appropriate expression of anger—is typically a component of IPT. Like CBT, IPT has been found to be effective for treating depression when administered in person, in group therapy, or via the phone or Internet, and across a broad age range.17-19

PST involves teaching patients a structured problem-solving process to decrease interpersonal strain and improve positive life experiences.20 Patients are taught to define their problem, generate and evaluate multiple solutions for it, implement a plan for the solution, and evaluate the results. In addition to being used to successfully treat adults,4,5 PST has been adapted effectively to treat adolescents16 and older adults.18

Somatic therapies are also an option

Exercise has long been considered a possible depression treatment due to its activity on endorphin, monoamine, and cortisol levels and via increased social and general activity. A 2013 Cochrane review of 39 randomized control trials (RCTs; N=2326) assessed whether exercise was effective for treating depression in adults.21 Thirty-five trials found a moderate effect size when specifically comparing exercise to no treatment or control interventions. The effect size was reduced, however, when analyses were restricted to trials with the highest methodological quality. There was no statistically significant difference when exercise was compared to pharmacologic treatment or psychotherapy.

Although the amount of research is meager, small but statistically significant improvements have also been found for older adults22 and children/adolescents.23 There is no consensus on the type, frequency, or intensity of exercise needed to achieve benefit. However, because nearly all studies for all age groups have found that exercise has no adverse psychological effects and substantial positive physical effects, exercise should be recommended to all patients with depression unless contraindicated.

Yoga (both exercise-based and meditation-based) has been evaluated both as a sole treatment and as an adjunctive treatment for depression. Several studies have supported the impact of yoga, particularly in pregnant women,24 although the evidence for its efficacy is inconsistent, with yoga frequently failing to improve upon the outcome of waitlist control.25 The evidence for meditation and mindfulness is more consistently positive, with these interventions equaling or exceeding “treatment as usual,” other psychotherapies, and antidepressants in numerous RCTs.25

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has a substantial evidence base supporting its efficacy.26 ECT has been used for decades, although stigma, cardiac and memory risks, and risks of anesthesia often limit its use. Benefits of ECT include a rapid response relative to pharmacotherapy (>50% of patients respond by the end of the first week of ECT)27 and a strong response in older patients.28

In repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), electromagnetic coils are placed on a patient’s head to deliver electromagnetic pulses that stimulate areas of the brain that regulate mood. Although rTMS is not widely available, a growing body of evidence supports its use for treating depression, including a meta-analysis of 34 RCTs that included 1383 patients.29 A multisite RCT (N=190) that was not industry-funded reported a 15% response rate and 60% maintenance of remission at 3 months (NNT=12).30 Although ECT is more effective than rTMS, rTMS appears useful for treatment-resistant depression, and can be used as an adjunctive treatment.29,31

Dietary supplements may be best used as adjuncts

St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), which contains 2 bioactive ingredients (hyperforin and hypericin), has been effectively used to treat depression.32 A 2008 Cochrane review that was limited to high-quality trials involving patients meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition criteria for depression identified 29 trials (N=5489), of which 18 involved comparisons with placebo and 17 with standard antidepressants.33 Patients’ depression was rated mild to moderate in 19 studies and moderate to severe in 9 studies. Trials examined 4 to 12 weeks of treatment with Hypericum extracts. This study (and several published since) provides strong clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of St. John’s wort for mild to moderate depression. There is insufficient evidence for its use for severe major depression.33TABLE 1 contains dosing information for St. John’s wort and other supplements used to treat depression.34-36

S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe). In a 2003 systematic review,37 1600 mg/d of oral SAMe was found to significantly benefit patients with depression in 4 of 5 studies, as did parenteral SAMe (7 of 7 trials). Another review of 48 studies found SAMe was safe and effective for depression.38 SAMe has been proposed for use alone or in combination with an antidepressant.

Folate and folic acid. Low folate levels have been associated with a less robust response to antidepressants in patients with MDD,39 and higher folate levels appear to be associated with better antidepressant response.40 A 2003 Cochrane review suggested folate might have a role in treating depression.39 A 2009 study found folate supplementation could reduce depressive symptoms for patients with normal baseline folate levels as well as those with low levels.41 Although the evidence is equivocal, folate augmentation may enhance antidepressant efficacy or improve response/remission rates.41,42

It seems reasonable to check folate levels in depressed patients, and address deficiencies by instructing patients to increase their dietary intake of folate or to take supplements. Augmenting antidepressants with folate appears to be low-risk and possibly helpful in maintaining remission.

Omega-3 fatty acids. There is substantial evidence that omega-3 fatty acids can prevent and treat depression.43,44 Recent meta-analyses support the use of omega-3 fatty acids as monotherapy and augmentation, but only formulations that contain a high eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) ratio (EPA/DHA 2:1).45,46 Omega-3 supplementation has been used with positive results in older adults, children,47 pregnant women,48 and women with postpartum depression.49 Although initial research into omega-3 treatment of depression appears promising, augmentation of standard antidepressant therapy may be a good conservative option.

Use a validated tool to monitor response to treatment

You can enhance outcomes for your patients with depression if you schedule routine follow-up visits with them to gauge adherence to recommendations, monitor response to treatment, and increase the intensity of care when response is inadequate.50 The most important aspect of monitoring response is to use a standardized instrument that quantifies symptoms at every visit.

The Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item depression assessment (PHQ-9)—which is free—has been validated for depression screening and monitoring of treatment response in primary care patients.51 A decrease of 5 points on the PHQ-9 is the minimum considered to be clinically significant.52 Other well-validated, although lengthier, self-report depression assessment and monitoring instruments include the Beck Depression Inventory-revised and the Zung Depression Scale.

CASE 1 › Mr. J is not enjoying his new job or engaging with new coworkers to replace the positive social experiences he had at his previous job. Together, you set a goal of increasing social involvement by having him make plans to see at least one friend per weekend. Because he indicates that he is unlikely to follow through with a therapy referral, you encourage him to try an online CBT program, start an exercise regimen, or take a SAMe supplement. Mr. Jackson agrees to try the CBT and exercise (moderate intensity, 30 minutes 3-4 times per week), but does not want to take SAMe. He agrees to an assessment of his folate levels, which are normal.

Mr. J starts the online CBT program, which reinforces the exercise and social activity prescription you provided. He establishes a regular exercise routine with a good friend. After one month, his mood has started to improve and he has added regular participation in a hobby (woodworking), as well as volunteer work, which he finds fulfilling. You plan to continue monitoring his depression and his adherence to the treatment plan.

CASE 2 › The recent move has decreased Mrs. S’s interactions with family and long-time friends. Because she had previously expressed interest in exercise, you encourage her to join a local “Mommy and Me” exercise and support group for mothers of toddlers. She is willing to participate in psychotherapy, so you provide a referral to a local therapist with expertise in IPT. You also discuss with Mrs. S the possible benefits of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, which appears to be safe during breastfeeding.34

Mrs. S begins therapy and exercise classes, but can’t motivate herself to continue either of these activities. She becomes discouraged because she’s unable to easily find an omega-3 fatty acid supplement with the ratio you specified (EPA/DHA 2:1). When you see her 2 weeks later, her depression has worsened.

Because you are concerned her suicidality will return, you revisit the pros and cons of taking an antidepressant. Although small amounts of antidepressants can be passed from mother to infant via breastmilk, the amount varies by specific medication, as do the potential risks. Mrs. S decides to resume taking paroxetine 20 mg/d and eventually, once her motivation improves, she’s able to add psychotherapy and exercise to her maintenance/relapse prevention regimen. After you discuss with her the possibility that B vitamin supplementation may assist in maintenance of remission, she adds L-methylfolate 7.5 mg/day to her regimen.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michele M. Larzelere, PhD; LSUHSC Department of Family Medicine; 200 W. Esplanade Avenue, Suite 409; Kenner, LA 70065; mlarze@lsuhsc.edu

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). QuickStats: Prevalence of Current Depression Among Persons Aged ≥12 Years, by Age Group and Sex — United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2010. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6051a7.htm. Accessed June 11, 2015.

2. Fournier J, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:47-53.

3. Dobson KS, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the prevention of relapse and recurrence in major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:468-477.

4. Barth J, Munder T, Gerger H, et al. Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: A network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001454.

5. Linde K, Sigterman K, Kriston L, et al. Effectiveness of psychological treatments for depressive disorders in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:56-68.

6. DeRubeis RJ, Webb CA, Tang TZ, et al. Cognitive therapy. In: Dobson KS, ed. Handbook of Cognitive Behavioral Therapies, 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2009:277-316.

7. Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2008;38:196-205.

8. Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, et al. Guided internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:288-295.

9. Twomey C, O’Reilly G, Byrne M. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 2015;32:3-15.

10. Zhou X, Michael K, Liu Y, et al. Systematic review of management for treatment-resistant depression in adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:340.

11. Ekers D, Webster L, Van Straten A, et al. Behavioural activation for depression: An update of meta-analysis of effectiveness and sub group analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100100.

12. Alexopoulos GS, Raue PJ, Kiosses DN, et al. Comparing engage with PST in late-life major depression: A preliminary report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:506-513.

13. Soucy Chartier I, Provencher MD. Behavioral activation for depression: Efficacy, effectiveness, and dissemination. J Affect Disord. 2013;145:292-299.

14. McCauley E, Gudmundson G, Schloredt K, et al. The Adolescent Behavior Activation Program: Adapting behavioral activation as a treatment for depression in adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;1-14. [Epub ahead of print].

15. Carlbring P, Hägglund M, Luthström A, et al. Internet-based behavioral activation and acceptance-based treatment for depression: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:331-337.

16. Markowitz JC, Weissman MM. Interpersonal psychotherapy: principles and applications. World Psychiatry. 2004; 3:136-139.

17. Kersting A, Kroker K, Schlicht S, et al. Efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral internet-based therapy in parents after the loss of a child during pregnancy: pilot data from a randomized controlled trial. Arch Womens Mental Health. 2011;14:465-477.

18. Francis J, Kumar A. Psychological treatment of late-life depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36:561-575.

19. Picardi A, Gaetano P. Psychotherapy of mood disorders. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2014;10:140-158.

20. Bell AC, D’Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Review. 2009;29:348-353.

21. Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD004366

22. Brindle C, Spanjers K, Patel S, et al. Effect of exercise on depression severity in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. B J Psychiatry. 2012;201:180-185.

23. Brown HE, Pearson N, Braithwaite RE, et al. Physical activity interventions and depression in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2013;43:195-206.

24. Gong H, Ni C, Shen X, et al. Yoga for prenatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:14.

25. D’Silva S, Poscablo C, Habousha R, et al. Mind-body medicine therapies for a range of depression severity: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:407-423.

26. Lisanby SH. Electroconvulsive therapy for depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1939-1945.

27. Husain MM, Rush AJ, Fink M, et al. Speed of response and remission in major depressive disorder with acute electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a Consortium for Research in ECT (CORE) report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:485-491.

28. Rhebergen D, Huisman A, Bouckaert F, et al. Older age is associated with rapid remission of depression after electroconvulsive therapy: a latent class growth analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:274-282.

29. Slotema CW, Blom JD, Hoek HW, et al. Should we expand the toolbox of psychiatric treatment methods to include Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)? A metaanalysis of the efficacy of rTMS in psychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:873-884.

30. George MS, Lisanby SH, Avery D, et al. Daily left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy for major depressive disorder: a sham-controlled randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:507-516

31. Liu B, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as an augmentative strategy for treatment-resistant depression, a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind and sham controlled studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:342.

32. Brown RP, Gerberg PL, Muskin PR. Mood disorders. In: Brown RP, Gerbarg PL, Muskin P. How to Use Herbs, Nutrients and Yoga in Mental Health. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company; 2009.

33. Linde K, Berner MM, Kriston L. St John’s wort for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD000448.

34. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database Web site. Available at: http://naturaldatabase.therapeuticresearch.com/home.aspx. Accessed March 1, 2015.

35. Harris WS. Expert opinion: omega-3 fatty acids and bleeding-cause for concern? Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:44C-6C.

36. Freeman MP, Fava M, Lake J, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in major depressive disorder: the American Psychiatric Association Task Force Report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:669-681.

37. Papakostas GI, Alpert JE, Fava M. S-adenosyl-methionine in depression: a comprehensive review of the literature. Curr Psychiatry Reports. 2003;5:460-466.

38. Brown RP, Gerbarg PL, Bottiglieri T. S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe) for depression: biochemical and clinical evidence. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:29-44.

39. Taylor MJ, Carney S, Geddes J, et al. Folate for depressive disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003390.

40. Alpert M, Silva RR, Pouget ER. Prediction of treatment response in geriatric depression from baseline folate level: interaction with an SSRI or a tricyclic antidepressant. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:309-313.

41. Fava M, Mischoulon D. Folate in depression: efficacy, safety, differences in formulations, and clinical issues. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 5):12-17.

42. Almeida OP, Ford AH, Hirani V, et al. B vitamins to enhance treatment response to antidepressants in middle-aged and older adults: results from the B-VITAGE randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:450-457.

43. Grosso G, Galvano F, Marventano S, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: scientific evidence and biological mechanisms. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:313570.

44. Appleton KM, Rogers PJ, Ness AR. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on depressed mood. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:757-770.

45. Grosso G, Pajak A, Marventano S, et al. Role of omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of depressive disorders: a comprehensive metaanalysis of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96905.

46. Martins JG, Bentsen H, Puri BK. Eicosapentaenoic acid appears to be the key omega-3 fatty acid component associated with efficacy in major depressive disorder: a critique of Bloch and Hannestad and updated meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:1144-1149.

47. Nemets H, Nemets B, Apter A, et al. Omega-3 treatment of childhood depression: a controlled, double-blind pilot study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1098-1100.

48. Su KP, Huang SY, Chiu TH. Omega-3 fatty acids for major depressive disorder during pregnancy: Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:644-651.

49. Freeman MP, Davis M, Sinha P, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and supportive psychotherapy for perinatal depression: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2008;110:142-148.

50. Mitchell J, Trangle M, Degnan B, et al. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Health Care Guideline: Adult depression in primary care. 16th ed. September 2013. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/fnhdm3/Depr-Interactive0512b.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2015.

51. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345-359.

52. Trivedi MH. Tools and strategies for ongoing assessment of depression:

a measurement-based approach to remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:26-31.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). QuickStats: Prevalence of Current Depression Among Persons Aged ≥12 Years, by Age Group and Sex — United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2010. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6051a7.htm. Accessed June 11, 2015.

2. Fournier J, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:47-53.

3. Dobson KS, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the prevention of relapse and recurrence in major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:468-477.

4. Barth J, Munder T, Gerger H, et al. Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: A network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001454.

5. Linde K, Sigterman K, Kriston L, et al. Effectiveness of psychological treatments for depressive disorders in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:56-68.

6. DeRubeis RJ, Webb CA, Tang TZ, et al. Cognitive therapy. In: Dobson KS, ed. Handbook of Cognitive Behavioral Therapies, 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2009:277-316.

7. Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2008;38:196-205.

8. Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, et al. Guided internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:288-295.

9. Twomey C, O’Reilly G, Byrne M. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 2015;32:3-15.

10. Zhou X, Michael K, Liu Y, et al. Systematic review of management for treatment-resistant depression in adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:340.

11. Ekers D, Webster L, Van Straten A, et al. Behavioural activation for depression: An update of meta-analysis of effectiveness and sub group analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100100.

12. Alexopoulos GS, Raue PJ, Kiosses DN, et al. Comparing engage with PST in late-life major depression: A preliminary report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:506-513.

13. Soucy Chartier I, Provencher MD. Behavioral activation for depression: Efficacy, effectiveness, and dissemination. J Affect Disord. 2013;145:292-299.

14. McCauley E, Gudmundson G, Schloredt K, et al. The Adolescent Behavior Activation Program: Adapting behavioral activation as a treatment for depression in adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;1-14. [Epub ahead of print].

15. Carlbring P, Hägglund M, Luthström A, et al. Internet-based behavioral activation and acceptance-based treatment for depression: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:331-337.

16. Markowitz JC, Weissman MM. Interpersonal psychotherapy: principles and applications. World Psychiatry. 2004; 3:136-139.

17. Kersting A, Kroker K, Schlicht S, et al. Efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral internet-based therapy in parents after the loss of a child during pregnancy: pilot data from a randomized controlled trial. Arch Womens Mental Health. 2011;14:465-477.

18. Francis J, Kumar A. Psychological treatment of late-life depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36:561-575.

19. Picardi A, Gaetano P. Psychotherapy of mood disorders. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2014;10:140-158.

20. Bell AC, D’Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Review. 2009;29:348-353.

21. Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD004366

22. Brindle C, Spanjers K, Patel S, et al. Effect of exercise on depression severity in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. B J Psychiatry. 2012;201:180-185.

23. Brown HE, Pearson N, Braithwaite RE, et al. Physical activity interventions and depression in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2013;43:195-206.

24. Gong H, Ni C, Shen X, et al. Yoga for prenatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:14.

25. D’Silva S, Poscablo C, Habousha R, et al. Mind-body medicine therapies for a range of depression severity: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:407-423.

26. Lisanby SH. Electroconvulsive therapy for depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1939-1945.

27. Husain MM, Rush AJ, Fink M, et al. Speed of response and remission in major depressive disorder with acute electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a Consortium for Research in ECT (CORE) report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:485-491.

28. Rhebergen D, Huisman A, Bouckaert F, et al. Older age is associated with rapid remission of depression after electroconvulsive therapy: a latent class growth analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:274-282.

29. Slotema CW, Blom JD, Hoek HW, et al. Should we expand the toolbox of psychiatric treatment methods to include Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)? A metaanalysis of the efficacy of rTMS in psychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:873-884.

30. George MS, Lisanby SH, Avery D, et al. Daily left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy for major depressive disorder: a sham-controlled randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:507-516

31. Liu B, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as an augmentative strategy for treatment-resistant depression, a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind and sham controlled studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:342.

32. Brown RP, Gerberg PL, Muskin PR. Mood disorders. In: Brown RP, Gerbarg PL, Muskin P. How to Use Herbs, Nutrients and Yoga in Mental Health. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company; 2009.

33. Linde K, Berner MM, Kriston L. St John’s wort for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD000448.

34. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database Web site. Available at: http://naturaldatabase.therapeuticresearch.com/home.aspx. Accessed March 1, 2015.

35. Harris WS. Expert opinion: omega-3 fatty acids and bleeding-cause for concern? Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:44C-6C.

36. Freeman MP, Fava M, Lake J, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in major depressive disorder: the American Psychiatric Association Task Force Report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:669-681.

37. Papakostas GI, Alpert JE, Fava M. S-adenosyl-methionine in depression: a comprehensive review of the literature. Curr Psychiatry Reports. 2003;5:460-466.

38. Brown RP, Gerbarg PL, Bottiglieri T. S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe) for depression: biochemical and clinical evidence. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:29-44.

39. Taylor MJ, Carney S, Geddes J, et al. Folate for depressive disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003390.

40. Alpert M, Silva RR, Pouget ER. Prediction of treatment response in geriatric depression from baseline folate level: interaction with an SSRI or a tricyclic antidepressant. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:309-313.

41. Fava M, Mischoulon D. Folate in depression: efficacy, safety, differences in formulations, and clinical issues. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 5):12-17.

42. Almeida OP, Ford AH, Hirani V, et al. B vitamins to enhance treatment response to antidepressants in middle-aged and older adults: results from the B-VITAGE randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:450-457.

43. Grosso G, Galvano F, Marventano S, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: scientific evidence and biological mechanisms. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:313570.

44. Appleton KM, Rogers PJ, Ness AR. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on depressed mood. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:757-770.

45. Grosso G, Pajak A, Marventano S, et al. Role of omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of depressive disorders: a comprehensive metaanalysis of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96905.

46. Martins JG, Bentsen H, Puri BK. Eicosapentaenoic acid appears to be the key omega-3 fatty acid component associated with efficacy in major depressive disorder: a critique of Bloch and Hannestad and updated meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:1144-1149.

47. Nemets H, Nemets B, Apter A, et al. Omega-3 treatment of childhood depression: a controlled, double-blind pilot study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1098-1100.

48. Su KP, Huang SY, Chiu TH. Omega-3 fatty acids for major depressive disorder during pregnancy: Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:644-651.

49. Freeman MP, Davis M, Sinha P, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and supportive psychotherapy for perinatal depression: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2008;110:142-148.

50. Mitchell J, Trangle M, Degnan B, et al. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Health Care Guideline: Adult depression in primary care. 16th ed. September 2013. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/fnhdm3/Depr-Interactive0512b.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2015.

51. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345-359.

52. Trivedi MH. Tools and strategies for ongoing assessment of depression:

a measurement-based approach to remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:26-31.