User login

From the Colorado Sickle Cell Network, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO.

This article is the fifth in our Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative series. See the related editorial by Oyeku et al in the February 2014 issue of JCOM. (—Ed.)

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the development and implementation of a patient navigation program to help individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) overcome barriers to finding adult primary care.

- Methods: Six patient navigators were recruited and received training. A workgroup was formed to clarify goals and objectives and develop standard procedures. Navigators were instrumental in establishing a network of primary care offices that were willing to accept new patients with SCD. Navigators assisted patients in making calls to primary care offices and in some cases would attend appointments with them.

- Results: About two-thirds of patients who were referred to the navigator program for primary care follow-up attended an initial appointment with a new primary care provider.

- Conclusion: Patient navigation is a feasible and useful strategy to help individuals with SCD overcome barriers to receiving comprehensive care.

With advances in the management of sickle cell disease (SCD), adults with SCD are living longer [1,2]. Adequate care for individuals with SCD requires that they receive both specialized services and comprehensive primary care. A lack of comprehensive outpatient care can translate into suboptimal outcomes and increased reliance on the emergency room [3].

In the metropolitan area of Denver, specialty care for individuals with SCD is centralized and easily accessible at a tertiary academic medical center. However, we found that many adult patients treated in our specialty setting had not established care with an adult primary care provider (PCP) or had not been seen regularly by their PCP for ongoing preventive primary care services. Thus, they were not getting their comprehensive care needs met. Although support was available from community-based organizations to help them access certain resources (eg, directions to the food bank), patients reported difficulties in accessing the adult care health system, for example, securing appointments with PCPs and securing/maintaining insurance. No services existed to specifically help them navigate through the complexities of obtaining needed care.

Patient navigation is a strategy commonly used in cancer care settings [4–7] to to help patients overcome barriers in accessing the health care system. Patient navigators can not only facilitate improved health care access and quality for underserved populations through advocacy and care coordination, but they can also address the information needs of patients and assist in overcoming language and cultural barriers. Navigation has been proposed as a strategy to help reduce health disparities [8].

We developed a patient navigation program to address unmet needs of children and adults with SCD receving care in our clinics. In this paper we describe our program.

Patient Navigator Program

Setting

The SCD Treatment Demonstration Program was created in 2004 by the federal government to improve care and outcomes for persons with SCD [9]. As a grantee of this program, we developed the Colorado Sickle Cell Care Network (CSCCN) to care for scd patients in the Denver metropolitan and surrounding area. The CSCCN is a collaboration between the Colorado Sickle Cell Treatment and Research Center and the Division of General Internal Medicine and Department of Hematology at the University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus, the Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders at Children’s Hospital Colorado, and 2 community-based organizations. With other grantees, we are participating in the Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative, a collaborative of teams utilizing iterative cycles of testing to learn what changes can be made to improve care processes [10].

Navigators

We developed the patient navigator program to help patients overcome barriers to receiving comprehensive care in a primary care medical home. We hired 4 patient navigators to serve individuals living in or seeking resources in the Denver metropolitan area. Persons interested in being navigators were required to first qualify to be official hospital volunteers at the University of Colorado Hospital and Children’s Hospital Colorado, a process that involved attending an orientation and obtaining official facility badging. They received patient navigation training at the Harold P. Freeman Patient Navigation Institute in New York [11] as well as completed the Colorado Patient Navigator Training Program [12]. Navigators in training learned about the history of patient navigation, health promotion and communication models, motivational interviewing techniques, and systemic and individual barriers to care. All patient navigators received training in HIPAA and went through a volunteer credentialing process at the hospital; however they do not have access to patient’s medical records or the electronic health records.

The navigators are from various backgrounds, and 2 of our patient navigators are bilingual Spanish-English speakers, enhancing our ability to outreach to individuals whose preferred language is Spanish and who may otherwise not be able to access available resources. Some of our patient navigators are family members of individuals being treated for SCD and are able to provide a unique perspective that aids program development.

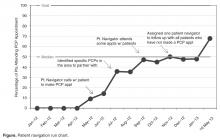

Once training for the initial group of navigators was completed, a patient navigation workgroup was created to clarify goals and objectives, develop standard procedures, and define navigator responsibilities. This workgroup included the CSCCN program staff, adult and pediatric hematology trained SCD specialists, and the pediatric coordinator. We used the Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative process [10] to develop and refine a process map for referrals made for primary care. Process mapping was an iterative process with regular input from the navigators and other members of the patient navigation workgroup, as well as input from case managers and social workers when needed.

Process

Upon receiving a referral, navigators made contact with the patient within 1 business day and obtained preferred contact information. The navigator completed a patient intake form and needs assessment. Each patient referral was logged into a secure database. Most referrals were generated by our specialty health care providers, but as awareness of the program grew referrals also came from the community-based organizations as well as self-referrals from patients or caregivers. Most of the referrals (68%) were specifically for assistance in finding a primary care medical home. Other reasons patients were referred to the navigator program included needing assistance with housing, financial assistance, or insurance application questions.

Barriers Addressed

Patient navigators spent much of their time proactively seeking local sources of adult primary care for clients and in doing so established a network of primary care offices in the community that would be able and willing to accept new patients with SCD. This was accomplished through personal outreach and communication with stakeholders at the academic medical center and in the community, utilizing skills learned during patient navigation training and by sorting through vast informational resources available to the public. When feasible the navigators, accompanied by the project director and adult hematology specialist, personally visited sites of primary care in the community to help provide information about the CSCCN and establish a working relationship.

Our navigators would make calls together with the patient to make a PCP appointment and would remind them of upcoming PCP appointments. In some cases, navigators would attend appointments with the patient; in addition, they would help advocate for them when they had to go to the emergency department. If a patient missed a PCP appointment, the navigator followed up to find out why and how to secure another appointment. Navigators would follow-up every 10 days if a patient had not yet seen a PCP. As many of our patients did not understand why they needed to have a PCP when they had a specialist, the navigators educated patients on the importance of PCP care.

In additon, navigators helped our patients deal with insurance coverage problems, such as frequent insurance changes/insurance getting dropped. Some patients had low literacy or had difficulties in filling out disability or insurance forms properly. Navigators received training from state coordinators for Medicaid and SSI disability on filling out the respective forms, which can be confusing.

Our navigators were trained in motivational interviewing and used it to identify other barriers patients were facing. In trying to obtain proper care, our patients struggled with competing priorities (eg, food, shelter, child care). Because of the numerous challenges that our patients and families face, an important role for the patients navigators was creating a bridge to accessing social and community resources.

Outcomes

The help and support provided by the navigators is helpful in mitigating the mistrust our patients have about the health care system, in part due to unfavorable initial experiences as young adults or being stereotyped for pain issues. Our patients have said that navigators make them feel like they have an advocate—someone who is on their side.

Subsequent to forming the initial navigator group, we expanded our program by adding 2 patient navigators in Colorado Springs, a smaller metropolitan area about an hour and a half south of Denver. In Colorado Springs, 16 referrals for services have been made but none of these referrals were specifically for a PCP, since access to a PCP was not a barrier to care in that locale. Patients were more likely to need help with things such as transportation to get to their location of specialty care.

Conclusion

Coordination of care is essential for individuals with chronic diseases. While the focus to date has been on coordination of care for common chronic illness such as diabetes, it is essential to use best practices for individuals with less common, but often more complex, chronic diseases such as SCD. To facilitate coordination of care for this population who receive specialty care in an academic medical center, we developed a patient navigation program for adults with SCD as a quality improvement project. Our navigation program assisted 62% of referred adults in the Denver metropolitan area in identifying a PCP and attending an initial appointment.

The program is continuing for the duration of the grant funding and at this time we will likely need to seek mechanisms for additional support to continue the work that has been started, as well as to consider measurement of outcomes that are meaningful to the institutions in which the program is housed in order to become more sustainable internally.

Patient navigation is an acceptable and feasible way to enhance the care for adults with SCD and can help to bridge systems of clinical care, support and resources. Our program can serve as a model for similar patient populations with orphan chronic diseases that have both primary care and subspecialty needs that have both distinct and overlapping roles. Sustainability is a crucial issue to address and the use of outcome measures that can accurately reflect both successes and challenges of program implementation will be important to share with institutional leaders.

Corresponding author: Linda S. Overholser, MD, MPH, 12631 E 17th Ave., Mail Stop B180, Academic Office 1, Aurora, CO 80045, linda.overholser@ucdenver.edu.

1. Prabhakar H, Haywood C Jr, Molokie R. Sickle cell disease in the United States: looking back and forward at 100 years of progress in management and survival. Am J Hematol 2010;85:346–53.

2. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

3. Hemker BG, Brousseau DC, Yan K, et al. When children with sickle-cell disease become adults: lack of outpatient care leads to increased use of the emergency department. Am J Hematol 2011;86:863–5.

4. Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract 1995 3:19–30.

5. Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 2011;117(15 Suppl):3539–42.

6. Natale-Pereira A, Enard KR, Nevarez L, Jones LA. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer 2011;117(15 Suppl):3543–52.

7. Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: current practices and approaches. Cancer 2005;104:848–55.

8. Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:992–1000.

9. Grosse SD, Schechter MS, Kulkarni R, et al. Models of comprehensive multidisciplinary care for individuals in the United States with genetic disorders. Pediatrics 2009;123:407–12.

10. Oyeku SO, Wang CJ, Scoville R, et al. Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative: using quality improvement (QI) to achieve equity in health care quality, coordination, and outcomes for sickle cell disease. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2012;23(3 Suppl):34–48.

11. Harold P. Freeman Patient Navigation Institute. Available at www.hpfreemanpni.org.

12. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative. Available at www.patientnavigatortraining.org.

From the Colorado Sickle Cell Network, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO.

This article is the fifth in our Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative series. See the related editorial by Oyeku et al in the February 2014 issue of JCOM. (—Ed.)

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the development and implementation of a patient navigation program to help individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) overcome barriers to finding adult primary care.

- Methods: Six patient navigators were recruited and received training. A workgroup was formed to clarify goals and objectives and develop standard procedures. Navigators were instrumental in establishing a network of primary care offices that were willing to accept new patients with SCD. Navigators assisted patients in making calls to primary care offices and in some cases would attend appointments with them.

- Results: About two-thirds of patients who were referred to the navigator program for primary care follow-up attended an initial appointment with a new primary care provider.

- Conclusion: Patient navigation is a feasible and useful strategy to help individuals with SCD overcome barriers to receiving comprehensive care.

With advances in the management of sickle cell disease (SCD), adults with SCD are living longer [1,2]. Adequate care for individuals with SCD requires that they receive both specialized services and comprehensive primary care. A lack of comprehensive outpatient care can translate into suboptimal outcomes and increased reliance on the emergency room [3].

In the metropolitan area of Denver, specialty care for individuals with SCD is centralized and easily accessible at a tertiary academic medical center. However, we found that many adult patients treated in our specialty setting had not established care with an adult primary care provider (PCP) or had not been seen regularly by their PCP for ongoing preventive primary care services. Thus, they were not getting their comprehensive care needs met. Although support was available from community-based organizations to help them access certain resources (eg, directions to the food bank), patients reported difficulties in accessing the adult care health system, for example, securing appointments with PCPs and securing/maintaining insurance. No services existed to specifically help them navigate through the complexities of obtaining needed care.

Patient navigation is a strategy commonly used in cancer care settings [4–7] to to help patients overcome barriers in accessing the health care system. Patient navigators can not only facilitate improved health care access and quality for underserved populations through advocacy and care coordination, but they can also address the information needs of patients and assist in overcoming language and cultural barriers. Navigation has been proposed as a strategy to help reduce health disparities [8].

We developed a patient navigation program to address unmet needs of children and adults with SCD receving care in our clinics. In this paper we describe our program.

Patient Navigator Program

Setting

The SCD Treatment Demonstration Program was created in 2004 by the federal government to improve care and outcomes for persons with SCD [9]. As a grantee of this program, we developed the Colorado Sickle Cell Care Network (CSCCN) to care for scd patients in the Denver metropolitan and surrounding area. The CSCCN is a collaboration between the Colorado Sickle Cell Treatment and Research Center and the Division of General Internal Medicine and Department of Hematology at the University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus, the Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders at Children’s Hospital Colorado, and 2 community-based organizations. With other grantees, we are participating in the Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative, a collaborative of teams utilizing iterative cycles of testing to learn what changes can be made to improve care processes [10].

Navigators

We developed the patient navigator program to help patients overcome barriers to receiving comprehensive care in a primary care medical home. We hired 4 patient navigators to serve individuals living in or seeking resources in the Denver metropolitan area. Persons interested in being navigators were required to first qualify to be official hospital volunteers at the University of Colorado Hospital and Children’s Hospital Colorado, a process that involved attending an orientation and obtaining official facility badging. They received patient navigation training at the Harold P. Freeman Patient Navigation Institute in New York [11] as well as completed the Colorado Patient Navigator Training Program [12]. Navigators in training learned about the history of patient navigation, health promotion and communication models, motivational interviewing techniques, and systemic and individual barriers to care. All patient navigators received training in HIPAA and went through a volunteer credentialing process at the hospital; however they do not have access to patient’s medical records or the electronic health records.

The navigators are from various backgrounds, and 2 of our patient navigators are bilingual Spanish-English speakers, enhancing our ability to outreach to individuals whose preferred language is Spanish and who may otherwise not be able to access available resources. Some of our patient navigators are family members of individuals being treated for SCD and are able to provide a unique perspective that aids program development.

Once training for the initial group of navigators was completed, a patient navigation workgroup was created to clarify goals and objectives, develop standard procedures, and define navigator responsibilities. This workgroup included the CSCCN program staff, adult and pediatric hematology trained SCD specialists, and the pediatric coordinator. We used the Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative process [10] to develop and refine a process map for referrals made for primary care. Process mapping was an iterative process with regular input from the navigators and other members of the patient navigation workgroup, as well as input from case managers and social workers when needed.

Process

Upon receiving a referral, navigators made contact with the patient within 1 business day and obtained preferred contact information. The navigator completed a patient intake form and needs assessment. Each patient referral was logged into a secure database. Most referrals were generated by our specialty health care providers, but as awareness of the program grew referrals also came from the community-based organizations as well as self-referrals from patients or caregivers. Most of the referrals (68%) were specifically for assistance in finding a primary care medical home. Other reasons patients were referred to the navigator program included needing assistance with housing, financial assistance, or insurance application questions.

Barriers Addressed

Patient navigators spent much of their time proactively seeking local sources of adult primary care for clients and in doing so established a network of primary care offices in the community that would be able and willing to accept new patients with SCD. This was accomplished through personal outreach and communication with stakeholders at the academic medical center and in the community, utilizing skills learned during patient navigation training and by sorting through vast informational resources available to the public. When feasible the navigators, accompanied by the project director and adult hematology specialist, personally visited sites of primary care in the community to help provide information about the CSCCN and establish a working relationship.

Our navigators would make calls together with the patient to make a PCP appointment and would remind them of upcoming PCP appointments. In some cases, navigators would attend appointments with the patient; in addition, they would help advocate for them when they had to go to the emergency department. If a patient missed a PCP appointment, the navigator followed up to find out why and how to secure another appointment. Navigators would follow-up every 10 days if a patient had not yet seen a PCP. As many of our patients did not understand why they needed to have a PCP when they had a specialist, the navigators educated patients on the importance of PCP care.

In additon, navigators helped our patients deal with insurance coverage problems, such as frequent insurance changes/insurance getting dropped. Some patients had low literacy or had difficulties in filling out disability or insurance forms properly. Navigators received training from state coordinators for Medicaid and SSI disability on filling out the respective forms, which can be confusing.

Our navigators were trained in motivational interviewing and used it to identify other barriers patients were facing. In trying to obtain proper care, our patients struggled with competing priorities (eg, food, shelter, child care). Because of the numerous challenges that our patients and families face, an important role for the patients navigators was creating a bridge to accessing social and community resources.

Outcomes

The help and support provided by the navigators is helpful in mitigating the mistrust our patients have about the health care system, in part due to unfavorable initial experiences as young adults or being stereotyped for pain issues. Our patients have said that navigators make them feel like they have an advocate—someone who is on their side.

Subsequent to forming the initial navigator group, we expanded our program by adding 2 patient navigators in Colorado Springs, a smaller metropolitan area about an hour and a half south of Denver. In Colorado Springs, 16 referrals for services have been made but none of these referrals were specifically for a PCP, since access to a PCP was not a barrier to care in that locale. Patients were more likely to need help with things such as transportation to get to their location of specialty care.

Conclusion

Coordination of care is essential for individuals with chronic diseases. While the focus to date has been on coordination of care for common chronic illness such as diabetes, it is essential to use best practices for individuals with less common, but often more complex, chronic diseases such as SCD. To facilitate coordination of care for this population who receive specialty care in an academic medical center, we developed a patient navigation program for adults with SCD as a quality improvement project. Our navigation program assisted 62% of referred adults in the Denver metropolitan area in identifying a PCP and attending an initial appointment.

The program is continuing for the duration of the grant funding and at this time we will likely need to seek mechanisms for additional support to continue the work that has been started, as well as to consider measurement of outcomes that are meaningful to the institutions in which the program is housed in order to become more sustainable internally.

Patient navigation is an acceptable and feasible way to enhance the care for adults with SCD and can help to bridge systems of clinical care, support and resources. Our program can serve as a model for similar patient populations with orphan chronic diseases that have both primary care and subspecialty needs that have both distinct and overlapping roles. Sustainability is a crucial issue to address and the use of outcome measures that can accurately reflect both successes and challenges of program implementation will be important to share with institutional leaders.

Corresponding author: Linda S. Overholser, MD, MPH, 12631 E 17th Ave., Mail Stop B180, Academic Office 1, Aurora, CO 80045, linda.overholser@ucdenver.edu.

From the Colorado Sickle Cell Network, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO.

This article is the fifth in our Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative series. See the related editorial by Oyeku et al in the February 2014 issue of JCOM. (—Ed.)

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the development and implementation of a patient navigation program to help individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) overcome barriers to finding adult primary care.

- Methods: Six patient navigators were recruited and received training. A workgroup was formed to clarify goals and objectives and develop standard procedures. Navigators were instrumental in establishing a network of primary care offices that were willing to accept new patients with SCD. Navigators assisted patients in making calls to primary care offices and in some cases would attend appointments with them.

- Results: About two-thirds of patients who were referred to the navigator program for primary care follow-up attended an initial appointment with a new primary care provider.

- Conclusion: Patient navigation is a feasible and useful strategy to help individuals with SCD overcome barriers to receiving comprehensive care.

With advances in the management of sickle cell disease (SCD), adults with SCD are living longer [1,2]. Adequate care for individuals with SCD requires that they receive both specialized services and comprehensive primary care. A lack of comprehensive outpatient care can translate into suboptimal outcomes and increased reliance on the emergency room [3].

In the metropolitan area of Denver, specialty care for individuals with SCD is centralized and easily accessible at a tertiary academic medical center. However, we found that many adult patients treated in our specialty setting had not established care with an adult primary care provider (PCP) or had not been seen regularly by their PCP for ongoing preventive primary care services. Thus, they were not getting their comprehensive care needs met. Although support was available from community-based organizations to help them access certain resources (eg, directions to the food bank), patients reported difficulties in accessing the adult care health system, for example, securing appointments with PCPs and securing/maintaining insurance. No services existed to specifically help them navigate through the complexities of obtaining needed care.

Patient navigation is a strategy commonly used in cancer care settings [4–7] to to help patients overcome barriers in accessing the health care system. Patient navigators can not only facilitate improved health care access and quality for underserved populations through advocacy and care coordination, but they can also address the information needs of patients and assist in overcoming language and cultural barriers. Navigation has been proposed as a strategy to help reduce health disparities [8].

We developed a patient navigation program to address unmet needs of children and adults with SCD receving care in our clinics. In this paper we describe our program.

Patient Navigator Program

Setting

The SCD Treatment Demonstration Program was created in 2004 by the federal government to improve care and outcomes for persons with SCD [9]. As a grantee of this program, we developed the Colorado Sickle Cell Care Network (CSCCN) to care for scd patients in the Denver metropolitan and surrounding area. The CSCCN is a collaboration between the Colorado Sickle Cell Treatment and Research Center and the Division of General Internal Medicine and Department of Hematology at the University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus, the Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders at Children’s Hospital Colorado, and 2 community-based organizations. With other grantees, we are participating in the Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative, a collaborative of teams utilizing iterative cycles of testing to learn what changes can be made to improve care processes [10].

Navigators

We developed the patient navigator program to help patients overcome barriers to receiving comprehensive care in a primary care medical home. We hired 4 patient navigators to serve individuals living in or seeking resources in the Denver metropolitan area. Persons interested in being navigators were required to first qualify to be official hospital volunteers at the University of Colorado Hospital and Children’s Hospital Colorado, a process that involved attending an orientation and obtaining official facility badging. They received patient navigation training at the Harold P. Freeman Patient Navigation Institute in New York [11] as well as completed the Colorado Patient Navigator Training Program [12]. Navigators in training learned about the history of patient navigation, health promotion and communication models, motivational interviewing techniques, and systemic and individual barriers to care. All patient navigators received training in HIPAA and went through a volunteer credentialing process at the hospital; however they do not have access to patient’s medical records or the electronic health records.

The navigators are from various backgrounds, and 2 of our patient navigators are bilingual Spanish-English speakers, enhancing our ability to outreach to individuals whose preferred language is Spanish and who may otherwise not be able to access available resources. Some of our patient navigators are family members of individuals being treated for SCD and are able to provide a unique perspective that aids program development.

Once training for the initial group of navigators was completed, a patient navigation workgroup was created to clarify goals and objectives, develop standard procedures, and define navigator responsibilities. This workgroup included the CSCCN program staff, adult and pediatric hematology trained SCD specialists, and the pediatric coordinator. We used the Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative process [10] to develop and refine a process map for referrals made for primary care. Process mapping was an iterative process with regular input from the navigators and other members of the patient navigation workgroup, as well as input from case managers and social workers when needed.

Process

Upon receiving a referral, navigators made contact with the patient within 1 business day and obtained preferred contact information. The navigator completed a patient intake form and needs assessment. Each patient referral was logged into a secure database. Most referrals were generated by our specialty health care providers, but as awareness of the program grew referrals also came from the community-based organizations as well as self-referrals from patients or caregivers. Most of the referrals (68%) were specifically for assistance in finding a primary care medical home. Other reasons patients were referred to the navigator program included needing assistance with housing, financial assistance, or insurance application questions.

Barriers Addressed

Patient navigators spent much of their time proactively seeking local sources of adult primary care for clients and in doing so established a network of primary care offices in the community that would be able and willing to accept new patients with SCD. This was accomplished through personal outreach and communication with stakeholders at the academic medical center and in the community, utilizing skills learned during patient navigation training and by sorting through vast informational resources available to the public. When feasible the navigators, accompanied by the project director and adult hematology specialist, personally visited sites of primary care in the community to help provide information about the CSCCN and establish a working relationship.

Our navigators would make calls together with the patient to make a PCP appointment and would remind them of upcoming PCP appointments. In some cases, navigators would attend appointments with the patient; in addition, they would help advocate for them when they had to go to the emergency department. If a patient missed a PCP appointment, the navigator followed up to find out why and how to secure another appointment. Navigators would follow-up every 10 days if a patient had not yet seen a PCP. As many of our patients did not understand why they needed to have a PCP when they had a specialist, the navigators educated patients on the importance of PCP care.

In additon, navigators helped our patients deal with insurance coverage problems, such as frequent insurance changes/insurance getting dropped. Some patients had low literacy or had difficulties in filling out disability or insurance forms properly. Navigators received training from state coordinators for Medicaid and SSI disability on filling out the respective forms, which can be confusing.

Our navigators were trained in motivational interviewing and used it to identify other barriers patients were facing. In trying to obtain proper care, our patients struggled with competing priorities (eg, food, shelter, child care). Because of the numerous challenges that our patients and families face, an important role for the patients navigators was creating a bridge to accessing social and community resources.

Outcomes

The help and support provided by the navigators is helpful in mitigating the mistrust our patients have about the health care system, in part due to unfavorable initial experiences as young adults or being stereotyped for pain issues. Our patients have said that navigators make them feel like they have an advocate—someone who is on their side.

Subsequent to forming the initial navigator group, we expanded our program by adding 2 patient navigators in Colorado Springs, a smaller metropolitan area about an hour and a half south of Denver. In Colorado Springs, 16 referrals for services have been made but none of these referrals were specifically for a PCP, since access to a PCP was not a barrier to care in that locale. Patients were more likely to need help with things such as transportation to get to their location of specialty care.

Conclusion

Coordination of care is essential for individuals with chronic diseases. While the focus to date has been on coordination of care for common chronic illness such as diabetes, it is essential to use best practices for individuals with less common, but often more complex, chronic diseases such as SCD. To facilitate coordination of care for this population who receive specialty care in an academic medical center, we developed a patient navigation program for adults with SCD as a quality improvement project. Our navigation program assisted 62% of referred adults in the Denver metropolitan area in identifying a PCP and attending an initial appointment.

The program is continuing for the duration of the grant funding and at this time we will likely need to seek mechanisms for additional support to continue the work that has been started, as well as to consider measurement of outcomes that are meaningful to the institutions in which the program is housed in order to become more sustainable internally.

Patient navigation is an acceptable and feasible way to enhance the care for adults with SCD and can help to bridge systems of clinical care, support and resources. Our program can serve as a model for similar patient populations with orphan chronic diseases that have both primary care and subspecialty needs that have both distinct and overlapping roles. Sustainability is a crucial issue to address and the use of outcome measures that can accurately reflect both successes and challenges of program implementation will be important to share with institutional leaders.

Corresponding author: Linda S. Overholser, MD, MPH, 12631 E 17th Ave., Mail Stop B180, Academic Office 1, Aurora, CO 80045, linda.overholser@ucdenver.edu.

1. Prabhakar H, Haywood C Jr, Molokie R. Sickle cell disease in the United States: looking back and forward at 100 years of progress in management and survival. Am J Hematol 2010;85:346–53.

2. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

3. Hemker BG, Brousseau DC, Yan K, et al. When children with sickle-cell disease become adults: lack of outpatient care leads to increased use of the emergency department. Am J Hematol 2011;86:863–5.

4. Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract 1995 3:19–30.

5. Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 2011;117(15 Suppl):3539–42.

6. Natale-Pereira A, Enard KR, Nevarez L, Jones LA. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer 2011;117(15 Suppl):3543–52.

7. Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: current practices and approaches. Cancer 2005;104:848–55.

8. Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:992–1000.

9. Grosse SD, Schechter MS, Kulkarni R, et al. Models of comprehensive multidisciplinary care for individuals in the United States with genetic disorders. Pediatrics 2009;123:407–12.

10. Oyeku SO, Wang CJ, Scoville R, et al. Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative: using quality improvement (QI) to achieve equity in health care quality, coordination, and outcomes for sickle cell disease. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2012;23(3 Suppl):34–48.

11. Harold P. Freeman Patient Navigation Institute. Available at www.hpfreemanpni.org.

12. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative. Available at www.patientnavigatortraining.org.

1. Prabhakar H, Haywood C Jr, Molokie R. Sickle cell disease in the United States: looking back and forward at 100 years of progress in management and survival. Am J Hematol 2010;85:346–53.

2. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

3. Hemker BG, Brousseau DC, Yan K, et al. When children with sickle-cell disease become adults: lack of outpatient care leads to increased use of the emergency department. Am J Hematol 2011;86:863–5.

4. Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract 1995 3:19–30.

5. Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 2011;117(15 Suppl):3539–42.

6. Natale-Pereira A, Enard KR, Nevarez L, Jones LA. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer 2011;117(15 Suppl):3543–52.

7. Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: current practices and approaches. Cancer 2005;104:848–55.

8. Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:992–1000.

9. Grosse SD, Schechter MS, Kulkarni R, et al. Models of comprehensive multidisciplinary care for individuals in the United States with genetic disorders. Pediatrics 2009;123:407–12.

10. Oyeku SO, Wang CJ, Scoville R, et al. Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative: using quality improvement (QI) to achieve equity in health care quality, coordination, and outcomes for sickle cell disease. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2012;23(3 Suppl):34–48.

11. Harold P. Freeman Patient Navigation Institute. Available at www.hpfreemanpni.org.

12. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative. Available at www.patientnavigatortraining.org.